My first involvement in photography began with cinematography. After college, I bought a Bolex movie camera designed for 16mm film but adapted for 8mm shooting (much cheaper than shooting and processing 16mm). I toted that big camera with me on backpacking and climbing trips (along with my still camera) and shot lots of footage, learning cinematography techniques by studying books.

As I became more involved in protecting some of these places, I realized the movies were not very helpful. First, there was no easy way to get your movies into theaters (and 8mm was not of high enough quality anyway), so you could not reach the broad audience you could with still photos published in magazines and books. In addition, splicing the film clips together into a logical order that told a story was labor intensive and time consuming. Also, these were silent movies. Adding sound—narration, music, voices—involved another layer of intensive work. And so, to fight my early conservation battles I switched to still photography.

Today, it is a radically different situation. Digital video makes it possible to create high quality documentaries and share them with a large audience via YouTube and Vimeo. Moreover, nearly every DSLR camera has video shooting capabilities, so this technology is at your fingertips. Editing also has become easier, with powerful computer programs that allow you to arrange clips, add transitions like fades (or even fancier things), and overlay a music track or narration or both.

Balancing the two, still photography and video, presents a challenge—but having the two is extremely valuable in documenting a place or issue. Interestingly, video technology is advancing so well that, at times, you can lift still images from video footage, as in the example below, showing two elephants sparring for dominance in Serengeti National Park. The HD video was shot with a DSLR.

This still photo was lifted from a video clip shot with a Canon DSLR in Serengeti National Park. If you plan to use images from video, be sure that you steady the camera on a tripod—or, in this case, a firm beanbag on the roof hatch of a safari vehicle.

Though the technology has changed dramatically, most of the important principles of good cinematography still apply. This chapter deals with these important principles and why shooting video should be approached with a different frame of mind from still photography.

Tom Dudzinski’s Ten Tips for Shooting Video

My good friend Tom Dudzinski is an award-winning PBS television and video producer with three decades of experience. He has put together a quick summary of good video techniques.

1. Unlike martinis, video should be neither shaken nor stirred. God created tripods for a reason. Use them! Or at least stabilize the camera on something solid like a bean bag, fence post, or the ground. And if you use one of the latter, make sure the camera is level. (Hint #1: When shooting on the ground, a man’s wallet often comes in handy to lift the front of the camera just a bit to get the right angle. Hint #2: Don’t forget to take your wallet when you’re done shooting!)

2. Let the scene, not the camera, create the action. Unless you have a professional fluid head on your tripod and you’ve logged many hours of shooting, your pans and tilts will not be smooth. This can be quite distracting. So compose your shot and don’t move the camera. Let the subject provide the action.

3. Forget that you have a zoom lens. Unless you are using pro gear, it is virtually impossible to get a nice, smooth zoom. And even if you can, long zooms can become quite tedious aesthetically. Instead, think of your zoom as an infinite set of fixed focal length lenses. Find the focal length that works best for your shot and stick with it.

4. Tell stories with your camera. Each story is comprised of multiple scenes. Together, these scenes will tell the beginning, middle, and ending of your story. Let each scene stand on its own to tell one little part of the overall story. And don’t forget to capture transition shots that will take you from scene to scene.

5. Don’t forget the audio! Unless you have disabled it, the camera’s mic is always on. So all the wonderful sounds that are part of the scene are being captured automatically. But since it is physically a part of the camera, the camera mic will also pick up the sound of your hands manipulating the camera, the cough of the person standing next to you—even you whispering to your wife, “Isn’t that cool!” All of those distractions will destroy the magic of the moment.

5B. If you actually want to hear the person you are interviewing or who is giving a presentation, use an external microphone. Unless your camera is within inches of the person talking, the on-camera mic will make that person sound like he or she is a mile away. Lavalier microphones are inexpensive and incredibly easy to use. Use them!

6. Bad lighting kills video. Video is far less forgiving than still photography when it comes to lighting. High contrast lighting, low lighting, and back lighting cannot easily be overcome when shooting video. If you can’t do anything about a bad lighting situation, put the camera down and enjoy the moment.

7. Pay attention! Think about what’s going on and anticipate what will happen next. Video is at its best when it truly captures the experience. But you need to be at the right place at the right time, and that doesn’t happen by accident. You need to work at being there—and recording—when that magic moment happens.

8. Video is where the action is! Beautiful scenics do have their place in video, but if that’s all you’re shooting, stick with still photography. Remember, video is all about motion. So if it moves, shoot it! If it’s not moving, it may already be dead.

9. Capture multiple perspectives. Again, think about storytelling and have the camera give the perspective of the different characters in your story. One is standing here, looking one way; the other is standing over there, looking the opposite direction. One is tall. The other is short. Move the camera around to different places to capture those perspectives, but don’t shoot while moving.

10. Know that you can break any of these rules. But first, know the rule you are breaking, and know why you are breaking it.

Filmmaking is storytelling. Documentaries tell a story. If you don’t have a shooting script, be thinking about what your storyline is while you are shooting. It shouldn’t be all scenery. People are a part of it. Include details like faces, activities, and hands doing things (like holding a camera).

If you intend to do a serious video documentary about your conservation project, plan it! Take the time to visualize the video from beginning to end. Watch other documentaries that you’ve enjoyed and see how they were done. Before you pick up the camera, it is critical to have a shooting script, storyboard, or a shot list. Since storyboards entail visual layouts of scenes using sketches or photos, a shooting script or simple shot list is perhaps the most practical.

The shooting script is simply a list of short sentences that describe the scenes and subjects you want to include in the order in which you want them to appear. Like a Hollywood movie, your documentary should tell a story with a beginning, middle, and end. However, you must tell your story in a much shorter time than the 90 minute Hollywood film. Do not even consider making a documentary any longer than 10 or 15 minutes unless you have Robert Redford starring in it. In fact, shorter is most often better, which makes it even more challenging. Basically, it’s best to assume that your audience will have the attention span of a 3-year-old.

“If you intend to do a serious video documentary about your conservation project, plan it!”

This is just a rough idea of using some simple way of outlining your video documentary. (LS = Long shot; MS = Medium shot, CU = closeup, VO = Voice over.)

A viewfinder is very important when using your DSLR for video. It not only gives a magnified view of the LCD screen but also blocks outside light and makes it much easier to compose the scene.

Shoot for Variety. Having a variety of shots will make for good editing later. When starting to shoot video keep in mind:

1. Establishing shots—Set the scene with, perhaps, a wide-angle view of a place, a sign, an entrance, etc.

2. Middle or medium shots—Move in closer to the subjects or action.

3. Close-ups—Get a tight shot of a face, a subject, or hands doing something. Shoot the details.

Stabilize the Camera, Even When Handholding. If it’s absolutely necessary to handhold the camera, use the viewfinder, not the fold-out LCD screen, and keep your elbows into your ribs. This approach gives more stability for the camera. Using that LCD screen requires that you hold the camera away from your body at arm’s length, and this often generates shakiness. Moreover, using the viewfinder allows you to better examine details in the scene for good composition. And watch the horizon line—when handholding, it’s easy to get it tilted as you’re concentrating on a subject. It’s really better to use a tripod or monopod if possible.

Don’t Zoom. As Tom points out, don’t zoom in or out—unless it’s for a very special effect. It is rare when you can zoom smoothly on camcorders and even tougher when you are using your regular lenses on your DSLR. It’s better to stop the camera, zoom in tight on a subject, then resume shooting. Also, remember that any camera movement is magnified when you’re zoomed in tight (telephoto shot). Brace the camera or use a tripod when shooting telephoto shots.

Don’t Pan. Don’t pan unless it’s to follow a moving subject. Panning a scenic shot while handholding often results in bumpy and visually distracting footage. Don’t do it. Instead use a tripod with a fluid pan head and pan sloooowly. A swish pan (moving the camera rapidly from one subject to another) is very tricky. It’s better to stop the shot, turn, and focus on another subject, then resume shooting.

When working with a moving subject, it’s sometimes best to keep the camera stationary and let the subject enter and leave the scene. If you have the time, do both—pan with the subject, then do another shot with the subject moving into and out of a stationary scene. It’s good to have a choice when editing.

Length of the Shot. How long should a shot be? As long as it takes to make a point. It is better to have too much footage than too little. Scenes can be trimmed later in editing, but you cannot add footage that you did not shoot.

Framing. Framing a scene in video is very much like using good rules of composition in still photography. There is one difference, however: you may need to plan your framing in anticipation of subject movement. With people, you can plan and direct such moves—but with wildlife you have to learn to read body language and anticipate in which direction the animal may move.

Lighting. As in still photography, light can establish the mood of a scene. Even if you plan to shoot a simple documentation of a place, the impact of lighting can be important in doing a good job. Video cameras tend to record scenes with more contrast than is desirable, which can present a problem in bright sunlight. The contrast of a still photo can easily be adjusted in Photoshop or Lightroom, but it is much more difficult to adjust a video’s contrast in postproduction. If you’ve ever watched a television news crew at work, you will have noticed that they often add fill lighting on the subjects using reflectors.

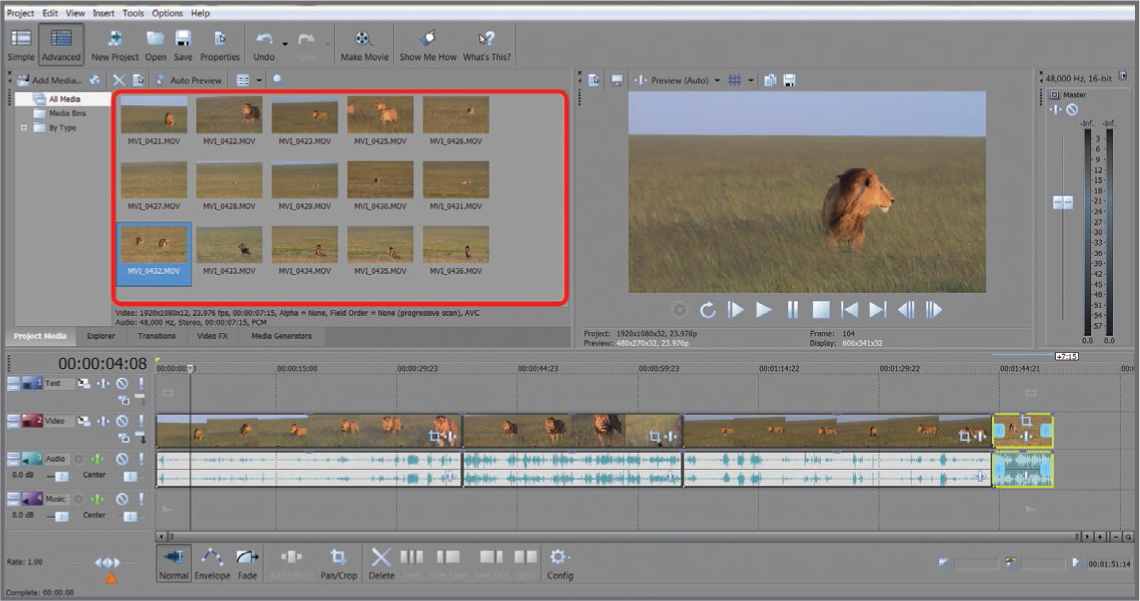

An inexpensive video editing program from Sony. Highlighted is the media bin, where video clips are dropped.

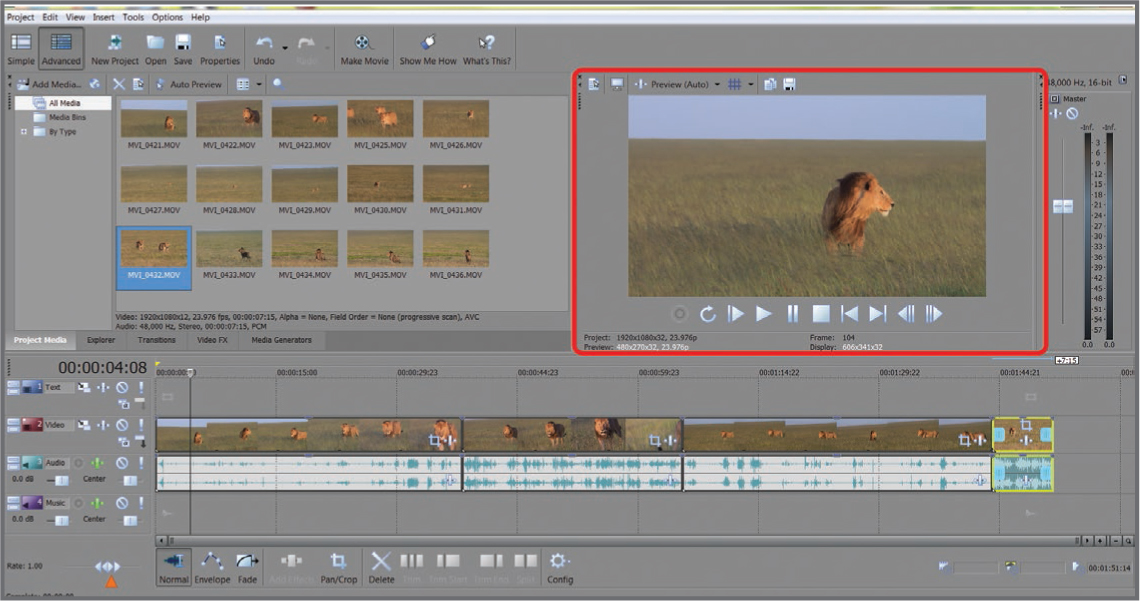

The Preview window for playing back clips or the timeline.

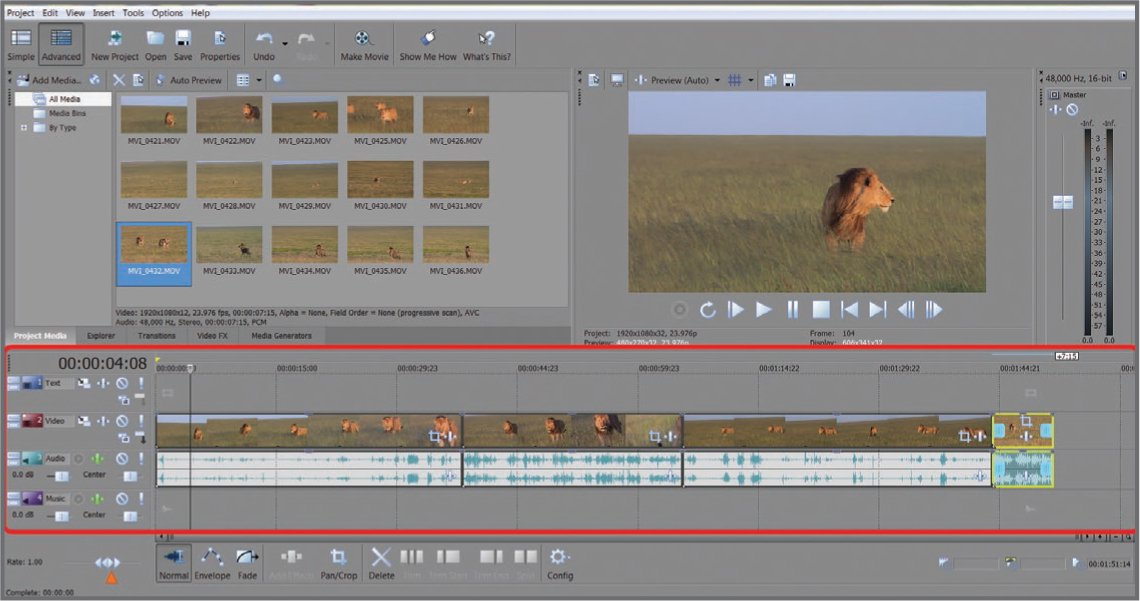

The timeline has separate tracks, which include Text for adding titles, a Video track, and an Audio track linked to the video clip, plus a Music track for adding music. More tracks can be added for such things as narration. All the editing takes place here. Sound levels can be adjusted, clips trimmed (shortened), transitions such as fades or dissolves added, narration recorded, and more.

Digital video’s great advantage over film lies in the capability of using a computer to edit. This is where you become a composer and create a symphony of sights and sounds for your video story. There are numerous video editing programs available, ranging from high-end pro versions to inexpensive consumer versions. Nowadays, even the inexpensive programs are capable of producing a sophisticated video with special effects, narration, and music. Most have similar features and layouts, as seen in the photos to the left.

Many of these programs have been improved greatly in recent years and the learning curve has shortened considerably. It is well worth learning video editing and using it for getting your message out there in an entertaining way.

When you’ve finished your production in the computer you will want to share it with others. You can burn a DVD or upload the video to YouTube, Vimeo, or your own website.

There will be times when you need to interview people for your video presentation. Good interviewing technique takes practice. The people on 60 Minutes make it look easy, but it’s not. It takes training, experience, and skill.

First and foremost, do not rely on the camera’s built-in microphone—especially if it is outdoors with wind noise and other background noises. It is worth investing in a wireless mic system, also called a lavalier. Even a low-cost system (under $150 for a set consisting of a wireless microphone, transmitter, and receiver) works far better than the built-in mic.

Think the interview through beforehand and ask questions that will help build your story. If your interviewee is someone fighting to save a place, ask how (and why) they got started. Build your story from there by asking relevant questions.