Chapter 4

God’s Word Written

God’s revelation to man was communicated in many instances in oral form. The prophets, for example, proclaimed their messages to their audiences orally, and in the case of the writing prophets, these messages were written down later. Our Lord’s teachings also were given in oral form, and within a generation after his glorification the Evangelists put them in written form. Oral tradition can be transmitted from generation to generation in a fairly accurate manner, but it always leaves the door open to innovations, additions, or deletions. We can, therefore, be very grateful that the revelation of God in history was put into writing.

This would not have been possible, however, had writing not been developed by the time of Moses and later prophets. The invention of writing, therefore, was of the greatest significance for the history of the Bible. Indeed, without such an invention we could have no Bible. It is only proper, then, that we say something about the development of the alphabets and the materials with which God’s revelation came to be recorded.

I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF WRITING

The first stage in the development of writing seems to have been the pictogram. There must have been, to begin with, many individual attempts at the picturization of people or objects. The pictogram is still used widely in modern advertising. TV commercials see to that! One might also call this “semantic” writing (sema in Greek means “sign”). It is extremely useful in road signs, especially when these are to be understood internationally. The pictogram communicates a message visually, not phonetically.

An extension of the pictogram is the ideogram, in which not objects but ideas are represented by the pictogram. The symbol of light might be the sun; the symbol of busyness, the bee; and so forth. Chinese script is an outstanding representative of ideographic writing. And we are not surprised to find that Chinese script makes use of an almost unlimited number of characters in order to overcome the ambiguities of the ideogram (the “sun,” for example, could also symbolize the day, or heat, instead of light; the “bee” could symbolize honey, or sweetness, instead of busyness).

Once a symbol is used for a sound, we leave behind the universal system of communicating by written or drawn symbols and restrict ourselves to one language. Arabic numeral “4” is understood worldwide, but if I give it a phonetic value by saying “four,” I have restricted its meaning to English (the German says vier, and the French quatre). The symbol of the bee might be understood universally, but when I say “bee,” I speak only to those who know English. The picture of the sun is understood if the spoken word “sun” were not used. (It should be added, however, that even in English the phonogram “sun” could be misunderstood if it were not spoken in a given context, since phonetically “sun” is the same as “son.”)

In alphabetic writing, such as we have in the English Bible, every sound is given a distinct symbol. This is true in theory; in practice English is one of the worst offenders—as foreigners who seek to learn English quickly discover. Why should “c” (as in car), “ck” (as in knock), “ch” (as in choir), and ‘k” (as in keep), all be pronounced as “k,” when in fact there are four different symbols used for the “k” sound? Other examples might be given; nevertheless, the principle of alphabetic writing still holds: one symbol per sound. But who devised the alphabets in which the books of our Bible were written?

II. THE ALPHABET AND SCRIPT OF BIBLICAL BOOKS

Alphabetic writing in one form or another may have been the brainchild of a number of people living in different parts of the world. Egyptian scribes, for example, developed syllabic writing that comes close to alphabetic out of their hieroglyphic writing, but it never developed into an independent alphabet. It may be that the Egyptians, nevertheless, did put the idea of alphabetic writing into someone’s head, for it is believed that the basic alphabet used by the biblical writers was devised by Syro-Palestinian Semites.

The word “alphabet” is nothing more than the combination of the names of the first two letters of the Greek alphabet, namely alpha and beta. Interestingly, these names are not entirely different from those of the Hebrew alphabet (aleph and beth are the Hebrew equivalents of the Greek alpha and beta, respectively). This suggests that our Hebrew and Greek alphabets have a common ancestor Greek tradition attributes the Greek alphabet to the Phoenicians and this is confirmed by the actual facts of the case.1

The Phoenician alphabet can be traced by inscriptions back to at least the eighteenth century B.C. It is called Phoenician because the Phoenicians were the first to use it, as far as is known, but it is the alphabet that before long came into use throughout Syria and Palestine and is known by the more general name of the North Semitic alphabet, to which also the Hebrew alphabet belongs.2

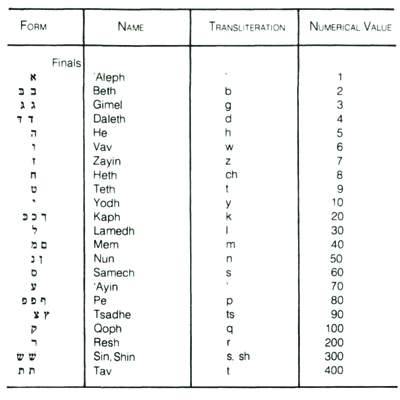

A. The Hebrew Alphabet

The Hebrew and Phoenician alphabets were actually two branches of a common stem, from which other scripts such as Moabite, Ammonite, and Edomite evolved.3 All these language groups in Syria and Palestine used basically the same alphabet.

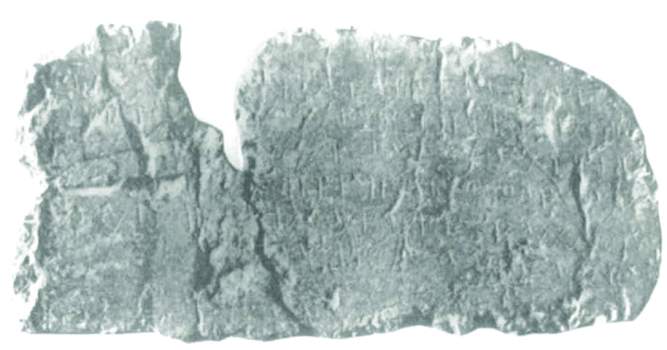

Through the excavations and research of the last century it is now possible to trace the Hebrew alphabet back to about 1000 B.C. There is, for example, the Gezer Calendar, a small soft stone tablet, discovered in 1908 at Gezer. It contains an enumeration of the agricultural seasons, and is assigned to about 1000 B.C, the time of Saul or David.4 The script is like that of Early Hebrew.

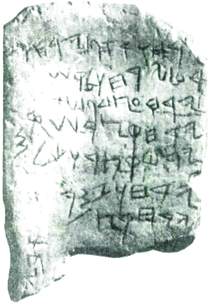

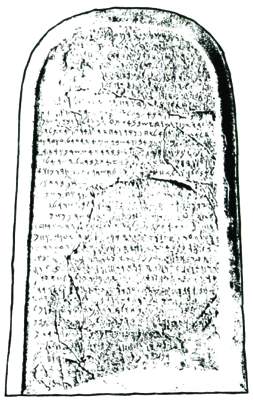

The Moabite Stone, discovered in 1868, has a long inscription that goes back to the ninth century B.C. It tells the story of King Mesha’s conflict with Omri, Israel’s king. This Moabite script is almost identical with the Hebrew script.

From the ninth or eighth century come the Samaritan Ostraca. These are inscribed potsherds, containing receipts and orders of various commodities such as oil, wine, and barley for the capital, Samaria. The script again is similar to biblical Hebrew.

In 1880 a lapidary inscription on the wall of the Siloam tunnel in Jerusalem was discovered. It dates back to the eighth century and tells the story of how Hezekiah’s men diverted the waters of Gihon into the walled City of David. This inscription of six lines dates from about 700 B.C.

In 1953-58 the so-called Lachish Letters were discovered. These are inscribed ostraca that describe the condition of the Lachish garrison during the last months of Judah’s struggle against Nebuchadnezzar. They give us an example of Hebrew in flowing handwriting from the sixth century. All these inscriptions have basically the same North Semitic alphabet, as do Hebrew, Phoenician, and other languages in that area.

The Gezer Calendar is the earliest known Hebrew inscription. This agricultural calendar dates from the second half of the tenth century B.C

A drawing of the Moabite stone. There are thirty-four lines of writing on the stone that tell of Moabite history and mention a conflict with Israel.

Several biblical fragments, found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, are written in Early Hebrew script. They probably belong to the fourth or third century B.C. The Dead Sea Scrolls generally, however, are written in the Hebrew Square Script, which developed under the influence of Aramaic and represents a later form of the alphabet. Prior to this discovery, in 1947, relatively few examples of the Hebrew Square Script were known. There was, of course, the square script of the Nash Papyrus of the second or first century B.C., but the other available manuscripts of the Hebrew OT belong to the ninth or tenth century A.D.—all written in the square script. With the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls it has become clear that before the Christian era the earlier Hebrew

The Siloam Inscription. It reads: “(Behold) the excavation. Now this is the history of the excavation. While the workmen were still lifting up the ax, each toward his neighbor, and while three cubits still remained to (cut through, each heard) the voice of the other who called to his neighbor since there was an excess in the rock on the right hand and on (the left). And on the day of the excavation the workmen struck, each to meet his neighbor, ax against ax, and there flowed the waters from the spring to the pool for a thousand two hundred cubits; and…of a cubit was the height of the rock over the heads of the workmen.”

brew script had changed to the “Square Script”—so-called because of the box-like form of the Hebrew letters.

The Hebrew alphabet consists of twenty-two ancient Semitic letters, all of them consonants (four of them were also used to represent vowels). As time went on, and familiarity with biblical Hebrew declined among the Jews, they also invented vowel signs, but this invention falls into the Christian era and we will have occasion to say more about that later. At this point we are simply underscoring the fact that the Hebrew script in which the OT books were originally written was the North Semitic alphabet, sometimes loosely called Phoenician, which was employed by other Semitic languages in Syria and Palestine.

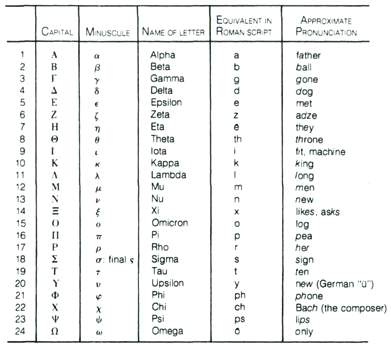

B. The Greek Alphabet

The Greek tradition that the seafaring Phoenicians gave them their alphabet is generally accepted as a historical fact. The North Semitic origin of the Greek alphabet can be seen from the following observations: (1) the shapes of nearly all the early Greek letters clearly recall their Semitic origin; (2) the phonetic value of the majority of the early Greek letters was the same as that of the Semitic; (3) the order of the Greek letters corresponds rather closely to the other of the Semitic letters; (4) the direction of writing in early Greek was from right to left as in the Semitic; and (5) the Greek letter names are meaningless in Greek, while some of their Semitic equivalents are

A comparison of early Aramaic, Phoenician, and Hebrew scripts. The top line shows the modern Hebrew alphabet, and the lines under it show the alphabet as found on the following inscriptions and scrolls. (1) Ahiram sarcophagus, c. 1000 B.C. Phoenician; (2) Gezer Calendar, late tenth century B.C. Hebrew (3) Mesha stele, mid-ninth century B.C, Moabite; (4) Samaria ostraca, eighth century B.C., Hebrew; (5) Bar-Rekub stele, late eighth century B.C. Aramaic; (6) Siloam inscription, c. 700 B.C. Hebrew; (7) Mezad Hashavyahu ostracon, late seventh century B.C. Hebrew; (8) Saqqara papyrus, c. 600 B.C., Aramaic; (9) Hebrew seals, late seventh—early sixth century B.C.; (1) Lachish ostraca, early sixth century B.C., Hebrew; (11) Elephantine papyrus, late fifth century B.C., Aramaic, (12) Eshmun’azor inscription, fifth century B.C. Phoenician; (13) Exodus scroll fragment, second century B.C. Paleo-Hebrew.

Semitic words5 (beth, the second letter of the alphabet, means “house”). While Greek is not a Semitic language, the alphabet of this European tongue is basically North Semitic.

There has been some debate over when the Greeks took over this Semitic alphabet. Perhaps we are safe in putting the date about 1000 B.C. The Greeks did not invent the alphabet, but they made some changes after they took it over. Like the Semitic scripts, earliest Greek was written from right to left. After about 500 B.C, however, the Greeks wrote from left to right, the way we do. There was, interestingly, an intermediate period in which they wrote in boustrophedon fashion (boustrophedon means literally, “as the oxen turns,” when plowing the field, alternating the rows from right to left, then left to right).

After receiving it through the Phoenicians, there arose some diversity in the Greek alphabet, but by the late fifth century B.C the Ionic Greek alphabet of twenty-four letters prevailed—final acceptance coming by edict. In contrast to the consonantal alphabet of the Semitic parent script, the Greek alphabet had vowel letters as well. It should be mentioned also that in addition to the Greek uncial script, in which many of the biblical books were originally written, there was also the flowing handwriting known as cursive.

Through its descendants in western Europe (the Etruscan and Latin alphabets) and in eastern Europe (the Cyrillic alphabet), the Greek alphabet became the progenitor of all European alphabets that have spread all over the world.6 And since most of us read our Bibles in English, a word should be added about the Latin alphabet.

C. The Latin Alphabet

The link between the Greek and the Latin alphabet that we use is the Etruscan. Greek colonists brought the Greek script to Italy where it was adopted by the Etruscans, and from them it was adopted by Latin speakers. And just as the Greeks had to adapt the Phoenician alphabet (Greek, for example, has no letter for the Semitic “j"), so the Greek script was adapted to Latin (Latin has no equivalent for the Greek zeta). Again, there were different forms of Latin script, and English to this day distinguishes between capital and lower-case letters, and between print and flowing handwriting.

Without a script we could not have had a Bible. Fortunately the Bible, both Old and New Testament, was written in a relatively simple alphabetic script. Had the biblical books been written in hieroglyphics they would be accessible to only a few professionals, but with Bibles available in Hebrew, Greek, and above all, in Latin scripts, every schoolboy or girl may read the Bible.

However, a written language is of little use without materials to write on. In God’s good providence such materials were at hand when God’s Word came to be written.

III. WRITING MATERIALS

A great variety of materials have been used by man for the keeping of records and memoranda. Stone, leaves, bark, skins, wood, metals, baked clay, potsherds, and papyrus have at one time or another served as writing materials. Some of these did not prove satisfactory in the long run; others were used for thousands of years until they, too, were eventually replaced by paper. We are interested here primarily in those materials on which the biblical books were written originally and on which they were later transcribed.

A. Stone

Natural surfaces of rock, the walls of caves and cliffs, offered the most obvious opportunities for the early attempts at pictographs. Later, monumental inscriptions were made. For example, there is the trilingual inscription of Darius the Great, at Behistun, in modern Iran. It was deciphered in the mid-nineteenth century and unlocked the secrets of cuneiform.7 We have already mentioned the Moabite Stone. There is also the famous Rosetta Stone, discovered in Egypt in 1799, written in three scripts (hieroglyphic, demotic, and Greek).

As far as the OT is concerned, we read only of the Decalogue being written on tables of stone. Obviously there are severe practical limitations to writing on stone.

B. Clay Tablets

Clay tablets were very popular in the ancient Near East, for they were cheap and durable. In cuneiform inscriptions (from cuneus, meaning “wedge") characters were jabbed rather than drawn upon tablets with a stylus when the clay was still soft. The tablets were then dried or baked and stored on shelves or in boxes. Thousands of such tablets have been unearthed by the archaeologists. At Boghaz-koy (Turkey) 10,000 clay tablets from the ancient Hittite capital were found in 1906. At Nuzi 20,000 clay tablets that have helped to illuminate the patriarchal period were unearthed in 1925. In 1929 the discovery of the Ras Shamra texts in northern Syria added greatly to our understanding of Canaanite culture. Then there are the 22,000 tablets discovered in 1936 at Mari, which oast light on Abraham’s journey from Ur to Haran. More recently, in 1974, some 16,000 tablets were unearthed at Ebla in northern Syria, and these promise to open up even further the culture of the Near East between the third and second millennia B.C.

It has at times been suggested that the ten toledoth (generations, histories) of Genesis were originally recorded on clay tablets, but that is not certain. The writing tablet, however, is mentioned in Isaiah 30:8 and in Habakkuk 2:2, but it is more likely that a wooden tablet is meant.

C. Wooden Tablets

It is well known that wooden tablets were in use in ancient times. In Greco-Roman times the wax-covered tabellae were in common use, sometimes bound together in book form. The Israeli archaeologist, Dr. Yadin,

Clay tablets were widely used for writing in the ancient Near East. This tablet is the eleventh Tablet of the Assyrian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh. It records the Babylonian version of the Flood.

found slats of wood with writing on them in the caves at Murabba’at, at the Dead Sea, dating from the second Jewish revolt (A.D. 130). In Ezekiel 37:15 it is reported that the prophet was told to “take a stick of wood and write on it.”

D. Papyrus

We already described the preparations of writing material from this reed plant when we traced the origins of our word for “Bible.” It is obvious from such texts as Job 8:11 and Isaiah 18:2 that papyrus was known to the ancient biblical writers. Papyrus as writing material was in use in Egypt as early as the third millennium B.C. and continued to be used well into the first millennium A.D.8

Unfortunately we have next to no OT papyrus manuscripts; we do have a goodly number of NT papyri. Although papyrus was cheaper than leather it had certain disadvantages. (1) It was not as readily available outside of Egypt; (2) there was the danger of punching it while writing; (3) it was more susceptible to damage from moisture; and (4) when it dried out it became highly fragile.

The sands of Egypt, however, have proved to be the best “library” for papyrus, and great quantities of mostly nonbiblical papyri have been discovered in the last hundred years. Although writings on papyrus were known earlier, the search for papyri began in earnest only about 1870, and soon the libraries of Vienna, Berlin, Paris, and London were procuring papyrus manuscripts. (Some countries got into the game somewhat later.) As recently as 1945 a large jar with forty-nine documents of the Gospel of Thomas were discovered at Nag Hammadi, in Egypt.

These nonbiblical papyri opened up a new era of lexicography and also cast new light on ancient cultures. Among them are bills, tax receipts, and many personal letters. For example, we have a letter of a husband to his pregnant wife, advising her that should she bear a son she is to bring him up; if it should be a girl to do away with her by exposure.9 We have deeds of divorce, last wills and testaments, marriage contracts, death notices, magical papyri, and so forth.

These discoveries made it clear that the Greek of the NT was not all that different from the Koine spoken elsewhere in the world. In many instances they opened up new meanings of the Greek words in the NT. Adolf Deissmann, in Light from the Ancient East, led the way in demonstrating the extreme usefulness of the secular papyri for understanding the Greek of the NT.

It has been the good fortune of biblical scholars to discover also some important papyrus manuscripts of the NT, and we will have more to say about these when we come to discuss the text of the NT.

E. Parchment

Whereas papyrus is writing material made from a plant, parchment is made from animal skins. The procedure of tanning animal skins was known from ancient times, but in the preparation of parchment more was involved than tanning. The skin was soaked in limewater and the hair on one side and the flesh on the other was scraped off. The skin was then stretched dried, and smoothed with pumice.10

Parchment was known as early as 3000 B.C. (as was papyrus), and some of the OT books may have been written on parchment originally. Whether the scroll that King Jehoiakim cut in pieces and burned (Jer. 36) was of papyrus or leather is difficult to determine. The most likely guess would be papyrus.11 Most of the biblical manuscripts in the Dead Sea Scrolls are of leather. Also, we are informed by the Letter of Aristeas (second century B.C.) that the scrolls of the Law which were brought from Jerusalem to Alexandria to be translated into Greek were leather.

The word “parchment” comes from the name of the city of Pergamum in Asia Minor. Pliny tells a story of King Eumenes of Pergamum who wanted to outshine the Egyptian Ptolemy by establishing a better library than Egypt could boast. Ptolemy V, of Egypt, then imposed an embargo on the export of papyrus from Egypt, to handicap the development of the library at Pergamum. To make up for the shortage of papyrus, as the story goes, parchment was invented at Pergamum. Perhaps all the story does is show the preeminence of Pergamum in developing parchment (called pergamene in Greek, Pergament in German).

Another Greek word used for parchment was diphthera (meaning “tanned leather"); in Latin, however, the word is membrana (from which we derive the English “membrane”). Greek then borrowed this Latin word, and Paul asks Timothy to bring with him “the books and the membrana (parchments)” (2 Tim. 4:13). Refined parchment is called vellum (from the Latin word for “calf,” our “veal”).

Parchment had the advantage that it was more durable than papyrus. Also, one could more readily make erasures. In fact we have manuscripts which are called palimpsests, in which the original text has been erased and a new text written over it.

To begin with, parchment manuscripts were in the form of scrolls (as were those of papyrus), but eventually the parchment codex prevailed over the scroll. In the codex form both sides of the parchment page could be used for writing, and so in the end parchment won out over papyrus. Most of our manuscripts of the OT, as well as of the NT, are parchment codices.

F. Ostraca

The use of pieces of broken and discarded pottery as writing material was widespread in the ancient world. They were readily available, inexpensive, and could easily be written on with pen and ink. Potsherds are mentioned in the OT (Job 2:8; Ps. 22:15; Isa 30:14), but no reference is made to their use for writing. Greek ostraca, with portions of our Gospels inscribed on them, have been found in Upper Egypt. Single ostraca may have been used as amulets, but they also served poor Christians as a kind of “Bible.”12

As time went on all earlier writing materials were superseded by paper. Paper made its way from the East across Central Asia to Egypt about A.D. 900. Here it replaced papyrus, as can be seen from letters in which the writer apologizes for using papyrus, when it would be more stylish to use paper. Papyrus, of course, gave the name “paper” to the new writing material.

Evidently because paper came to Europe from Mohammedan sources, it lay under the displeasure of the church at first. For some time it could be used only for writings that were of little significance. But with the development of printing in the fifteenth century, paper was assured of victory over parchment and papyrus. The first Bible ever to be printed, Gutenberg’s Latin Vulgate, was printed partly on parchment and partly on paper.

A writer needs not only materials to write on, but also instruments to write with. The instrument is determined largely by the writing material. For inscriptions on stone or metal, a chisel would be required. Incisions on soft clay would call for a stylus, either of wood, bone, or metal. The OT speaks of an iron tool (Job 19:24; Jer. 17:1). For writing with ink on papyrus, leather, parchment, wooden tablets, or ostraca, reed pens were used (see Jer. 8:8). About the third century B.C. Greek writers in Egypt devised a new type of pen by splitting the point of a reed to form a nib. This true pen is called a kalamos (“reed”) in Greek, and is mentioned in 3 John 13.

Black ink was made from carbon in the form of soot mixed with a thin solution of gum. This was dried into cakes and then moistened with water for use. The NT word for ink, melas, means “black” (2 Cor. 3:3; 2 John 12; 3 John 13). Red ink was also used, especially for headings (our word “rubric” comes from the Latin word ruber, meaning “red”).

A penknife was used for sharpening pens (Jer. 36:23). A straight edge for ruling lines, pumice stone for smoothing papyrus, and a sponge for making erasures were all part of a writer’s equipment.13

God in his infinite mercy condescended to make use of such very earthy materials to bestow on us the greatest literary treasure of human history: God’s Word written.

SUGGESTED READING

Black, M. “Language and Script,” Cambridge History of the Bible, eds. P. R. Ackroyd and C. F. Evans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970, Vol. 1, pp. 1-29.

Bruce. F. F. The Books and the Parchments, 3rd rev. ed. Old Tappan: Revell, 1963. See “The Bible and the Alphabet,” pp. 15-32.

Kenyon, F. G. Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts, rev. ed. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1958. See “Ancient Books and Writing,” pp 19-46.

Lambin, T. O. “Alphabet,” Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, 4 vols. ed. G. A. Buttrick. Nashville: Abingdon, 1962, Vol. 1, pp. 89-96.

Pritchard, J. B., ed. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950.

Snaith, N. H. “The language of the Old Testament,” Interpreter’s Bible, 12 vols. ed. G.A. Buttrick. Nashville: Abingdon, 1951, Vol. 7, pp. 43-59.

1 F. F. Bruce, The Books and the Parchments, 3rd rev. ed (Old Tappan: Revell, 1963), p. 18.

2 Bruce, Books and Parchments, p. 22.

3 D. Diringer, “The Biblical Scripts,” Cambridge History of the Bible, eds. P. R. Ackroyd and C. F. Evans (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970), Vol. 1, p. 13.

4 Diringer, “The Biblical Scripts,” p. 13.

5 Diringer, “The Biblical Scripts,” pp. 18-19.

6 Diringer, “The Biblical Scripts,” p. 20.

7 F. C. Putman, “Key Finds in Archaeology,” Eternity Vol. 30 (Oct. 1979), p. 35.

8 J. C. Trever, “Papyrus,” Interpreter’s Dictionary if the Bible, ed. G. Buttrick (Nashville: Abingdon, 1962), Vol. 3, p. 649.

9 C. K. Barrett, The New Testament Background Selected Documents (New York: Harper and How, 1961), p. 38.

10 J. Finegan, Encountering New Testament Manuscripts (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974), p. 25.

11 I. M. Price, The Ancestry of Our English Bible, 3rd ed., revised by W. A. Irwin and Allen P. Wikgren (New York: Harper and Row, 1956), p. 17.

12 A. Deissmann, Light from the Ancient East (Sevenoaks, England: Hodder and Stoughton, 1910), pp. 41-52.

13 R. J Williams, “Writing,” Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, ed. G. Buttrick (Nashville: Abingdon, 1962), Vol. 4, p. 919.