Chapter 6

Extracanonical Books

The Bible of Jesus and his disciples was the Hebrew Bible of twenty-four books. This Bible had, however, been translated into Greek by Alexandrian Jews prior to Christ’s birth. When the gospel left its Palestinian homeland and began to penetrate the Greekspeaking world this Greek translation of the Old Testament, known as the Septuagint, proved to be very helpful to the messengers of the good news.

Since the Septuagint, at least in the manuscripts that have come down to us, contains many books not found in the Hebrew Bible, the question must be asked whether these extracanonical books, known today as the Apocrypha, have any right to be considered canonical. Before we answer that question we must make a survey of this apocryphal literature.

I. THE APOCRYPHA

A. The Meaning and Use of the Term

One of the difficulties in explaining the meaning of the word “Apocrypha” arises from the fact that the word means different things to different people. The word apocrypha is a Greek neuter plural of the singular apokryphon, and signifies books that are “hidden away.”

It was originally a term applied to those books that were held to be so mysterious and profound that in the opinion of some Jews they were to be hidden from ordinary readers. Since only the initiated could understand them, they were to be withdrawn from common use.1

We have already referred to the fictitious story in which Ezra is said to have restored all the books after they had been destroyed during the exile, and that he produced ninety-four volumes, twenty-four to be published and seventy to be kept secret from the ordinary person because they were too lofty. This story illustrates the view that “apocryphal,” to begin with, described those books that were too deep for the common person.

That, however, is not the way we use the word “apocryphal” today. Nowadays, when something is described as apocryphal, we mean that it is fictitious. An apocryphal story is simply not true. The word is used of legendary tales that tend to gather around distinguished people. In this popular sense of the word, “apocryphal” is really a derogatory term. In fact, early Christians used the term apocryphal for those books that were withheld from general circulation, not because they were so profound but because of doubts about their authenticity.2

We use the word “apocryphal” in this chapter to refer to that collection of Jewish books that are not found in the Hebrew Bible. These books are, however, in the Greek Septuagint, and Jerome grudgingly allowed them to slip into the Latin Vulgate in the fourth century A.D., and so they have become part of the Bible of the Roman Catholic Church. Protestants, however, do not accept them as canonical and call them “Apocrypha.” Many Protestant Bibles have the Apocrypha in them, but they are not held to be on par with the twenty-four books of the Hebrew Bible.

B. Their Number and Date

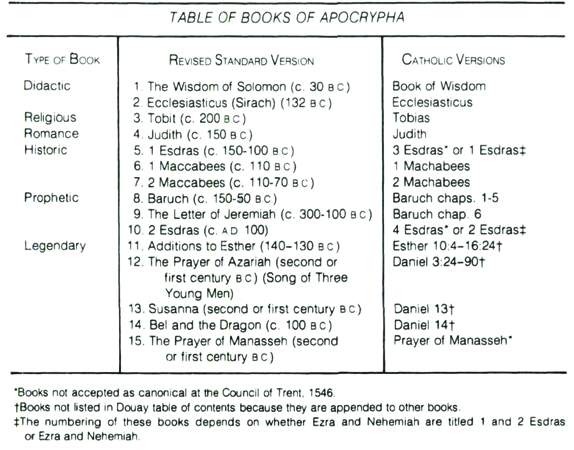

Generally speaking there are fourteen or fifteen books, written during the last two centuries before Christ and the first century of the Christian era, that make up the collection of books called the Apocrypha. The Revised Standard Version (in those editions that have the Apocrypha) lists the following titles: (1) 1 Esdras, (2) 2 Esdras,(3) Tobit, (4) Judith, (5) Additions to Esther, (6) The Wisdom of Solomon, (7) Ecclesiasticus, or the Wisdom of Jesus the Son of Sirach, (8) Baruch, (9) The Letter of Jeremiah, (10) The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Young Men, (11) Susanna, (12) Bel and the Dragon, (13) The Prayer of Manasseh, (14) 1 Maccabees, (15) 2 Maccabees.

In some previous English editions The Letter of Jeremiah was incorporated into the Book of Baruch, giving us fourteen instead of fifteen Apocrypha. These may be called the “official” Apocrypha. But if we look into a modern printed Septuagint, we notice, for example, that 2 Esdras is not included, while 3 and 4 Maccabees, as well as Psalm 151 are. It does not follow, of course, that the Septuagint always contained the same number of apocryphal books.

In Roman Catholic Bibles the list is considerably shorter. In 1546 the Council of Trent declared Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Baruch, 1 and 2 Maccabees, and certain supplementary parts of Esther and Daniel to be canonical and on a par with the books of the OT, among which they are dispersed.3 Since these ten or eleven books were accepted into the canon at a later time, some Catholic scholars speak of them as deuterocanonical. If Catholic scholars use the word “Apocrypha” they mean those books that others call the Pseudepigrapha, on which we shall comment later. There is, then, considerable confusion on the limits of the OT Apocrypha.

We need not go into detail in the matter of the dates of these books. Several

of them, such as 1 Esdras, Tobit, The Song of Three Young Men, are pre-Maccabean (c. 300-200 B.C.). Others come from the Maccabean period (C. 200-100 B.C; Judas Maccabeus died 160 B.C.) Judith, Ecclesiasticus, Bel and the Dragon, and Additions to Esther would belong to this period. Still others are post-Maccabean (c. 100 B.C to A.D. 100). First and 2 Maccabees, Susanna, The Wisdom of Solomon, Baruch, The Prayer of Manasseh, and 2 Esdras would belong to this latter period.

C. Their Literary Character

Several books of the Apocrypha are (1) historical in character. First Esdras may be viewed as a variant version of Chronicles-Ezra-Nehemiah. (Esdras is simply the Greek form of Ezra.) First Maccabees is our principal source of information on the Jewish struggle for independence under the Hasmoneans. Martin Luther valued this book so highly that he thought it was not unworthy to be reckoned among the books of Scripture. Second Maccabees provides us with glimpses into this same period, but it is not as trustworthy historically as is 1 Maccabees4 Some copies of the Septuagint have 3 and 4 Maccabees These books which also reflect some aspects of Jewish life during this period, were never part of the official Apocrypha in Western Christendom.

A number of apocryphal books may be classified (2) as religious fiction. Some of these are moralistic novels. This category would apply to the Book of Tobit—a charming tale that underscores the importance of observing the Law. Judith, by contrast, is a blood-thirsty thriller (a forerunner of the modern detective story).

The Additions to Esther are designed chiefly to compensate for the absence of the name of God or, in the opinion of some, the lack of true religion in the canonical book. The Additions to Daniel include the story of Susanna, in which Daniel rises to the defense of an innocent but maligned girl. In Bel and the Dragon, Daniel exposes the fraudulent conduct of idolatrous pagan priests. A third addition to Daniel is inserted between verses 23 and 24 of chapter 3 of our canonical Daniel. There is first a prayer for deliverance, put into the mouth of Azariah (Abednego), followed by an ascription of praise to God by the three young men who had been thrown into the furnace of fire for refusing to worship the king’s image.

There are some apocryphal books that may be called (3) didactic treatises, or wisdom literature. Two of the books are, in fact, called “wisdom” books: The Wisdom of Jesus the son of Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus—not to be confused with Ecclesiastes), and the so-called Wisdom of Solomon.

Baruch contains, besides a homily on wisdom, a confession of national sin and a promise of deliverance and restoration. The Epistle of Jeremiah, which is sometimes attached to Baruch, contains a warning against idolatry.

The Prayer of Manasseh is a confession of sin and a petition for forgiveness that King Manasseh is supposed to have made in Babylonian captivity. Together with The Prayer of Azariah and The Song of the Three Young Men, it ranks high as devotional literature. Finally, (4) there is one apocalyptic book (2 Esdras) that is not in the Septuagint but is usually included in the official Apocrypha as they are listed in Protestant Bibles. Martin Luther thought it was so bizarre that he refused to translate it for his German Bible. He says that he had thrown this book into the Elbe. Much of the literature classified as pseudepigraphical is apocalyptic in character.

D. Their Acceptance

1. By the Jews. The apocryphal books, many of them written originally in Hebrew or Aramaic and later translated into Greek, were written during those centuries in which the Jewish community experienced much trouble and stress. They are, of course, not the only books written by the Jews during this time There were other “outside books,” as they were known in Judaism. According to statements in the Talmud we learn that the canonical books were said “to defile the hands.” This phrase was employed to designate canonical books, although the reason why they were so desigpted is not clear. The books that we now call apocryphal were said not “to defile the hands.” These writings enjoyed considerable popularity at first, as can be seen, from the fact that they were translated into Greek or Aramaic.

There is, however, no evidence that they were ever considered as Scripture by the Jews. It has sometimes been argued that Alexandrian Jews did not limit the canon to the twenty-four Hebrew books, since the Apocrypha were translated by them into Greek and were eventually included in the Septuagint. Their presence in the Septuagint, however, does not of itself prove that Alexandrian Jews had more liberal views in the matter of the canon. Philo, who was an Alexandrian Jew (died C. A.D. 50), adhered strictly to the Hebrew canon and ignored the Apocrypha completely.5 It does not follow, however, that all Alexandrian Jews were equally strict.

Just how these books crept into the Septuagint originally, no one knows. It has been suggested that these book rolls were kept on the same shelves with the biblical books, and that with the change to the codex form of the book, they were incorporated with the canonical books.

After the destruction of Jerusalem and the advent of Christianity, the Apocrypha (as well as the Pseudepigrapha) fell into disuse. The survival of these books can be attributed mainly to the interest that Christians took in them.

2. By the New Testament. Since the writers of the NT wrote in Greek, they tended to take their quotations from the Septuagint version of the OT (according to one estimate, 80 percent of all quotations in the NT are from the Septuagint, although their wording is not always exactly the same as in that version). The Septuagint made the Apocrypha available to NT writers. However, these writers never quote from the apocryphal books. Jesus and his apostles evidently did not consider them as canonical, for they ignore them completely. This argument, however, must be used with care, for there is no direct quotation in the NT from Joshua, Judges, Esther, and other OT books, either.

It should be noted, also, that even if the NT writers had quoted the Apocrypha, that would not by itself have made them canonical. After all, Paul can quote pagan authors, such as Epimenides (Titus 1:12) and Menander (1 Cor. 15:33), and Jude can quote the Book of Enoch (Jude, 14-15)—a noncanonical book. Others could be mentioned.

Nestle’s Greek NT lists some 132 NT passages that appear to be verbal allusions to paracanonical books, but that is the kind of thing we would expect. Writers living at a given period in history tend to reflect the current language of their day. There is, however, no indication that Jesus or the apostles viewed the Apocrypha as Scripture. Verbal similarities between New Testament writings and apocryphal books does not mean that Jesus and his apostles viewed the Apocrypha as authoritative—something they obviously did not do.

3. By the Early Church. The early church felt no particular inclination to proscribe the Apocrypha. In fact, it was the popularity of these books that stimulated Jewish reaction against the Apocrypha. One wonders whether these books, produced by Jews, would have survived had it not been for the church.

The limits of the OT canon were not always clearly drawn in the early church, as can be seen from some of the debates on this matter. Melito of Sardis (A.D. 170) drew up a list of OT books that excluded the Apocrypha. Origen was challenged by the Bishop of Emmaus, Julius Africanus (C. A.D. 240), for his use of Susanna, since that book was not in the Hebrew Bible. Jerome refused to translate these books into Latin for his Vulgate (C. A.D. 391), but yielded to pressure by the bishops and allowed them to be included in their Old Latin form. Augustine felt that ecclesiastical custom favored the inclusion of the Apocrypha in the canon. Cyril of Jerusalem (died A.D. 444), however, exhorted his catechumens to hold fast to the books in the Hebrew Bible and to disregard the Apocrypha 6

This vacillation in the attitude of the church to the Apocrypha is reflected in the manuscripts of the Septuagint itself. The Codex Vaticanus (fourth/ fifth century A.D.) omits 1 and 2 Maccabees and The Prayer of Manasseh; the Codex Alexandrinus (fifth century A.D.) contains, in addition to the standard Apocrypha, also 3 and 4 Maccabees and The Prayer of Manasseh (among the Odes, supplementing the Psalms).

Only a few scholars in the Latinspeaking church of the early centuries seem to have objected to the use of the Apocrypha, and so by common usage throughout the Middle Ages they took on the same authority that the OT books had.

4. The Roman Catholic Church. During the Middle Ages the apocryphal books enjoyed almost undisputed canonicity. With the revival of learning, leading to the study of Hebrew once more, and with the Protestant Reformation and its polemic against Roman Catholic doctrines, the question of the canon became very acute once again. Martin Luther (c. 1534) translated the Apocrypha into German, but he set them off from the rest of the OT in his German Bible, and wrote in the foreword to them that they were not to be regarded as sacred Scripture, even though they could be read with profit.

The Roman Catholic Church was quick to respond, and in 1546 the Council of Trent declared all the Apocrypha (with the exception of 1 and 2 Esdras and The Prayer of Manasseh) to be canonical, and the Council pronounced every person anathema who did not accept the Apocrypha as canonical. This was the first council of the (Roman Catholic) church to give official approval to the present set of apocryphal books.

The Anglican Church accepted the Apocrypha for instruction in life and manners, but not for the establishment of doctrine (Article VI in the Thirty-Nine Articles). Lectionaries from the Apocrypha have been used in the Anglican liturgy from time to time. Luther valued the books highly, but he did not view them as Scripture. Reformed churches in the Calvinistic tradition took a clear-cut approach. The Westminster Confession (1648) states unequivocally that the Apocrypha are not divinely inspired and therefore have no authority in the church of God and are to be viewed as human books. In contrast to the Roman Catholic Church, no Protestant bodies accepted the Apocrypha as Scripture.

5. English Bibles and the Apocrypha. English Bibles were patterned after those of the Continental Reformers by having the Apocrypha set off from the rest of the OT. Coverdale (1535) called them “Apocrypha.” All English Bibles prior to 1629 contained the Apocrypha. Matthew’s Bible (1537), the Great Bible (1539), the Geneva Bible (1560), the Bishops’ Bible (1568), and the King James Bible (1611) contained the Apocrypha. Soon after the publication of the KJV, however, the English Bibles began to drop the Apocrypha and eventually they disappeared entirely. The first English Bible to be printed in America (1782-83) lacked the Apocrypha. In 1826 the British and Foreign Bible Society decided no longer to print them.

Today the trend is in the opposite direction, and English Bibles with the Apocrypha are becoming more popular again. This has raised the question of their canonicity once more, and we should give some reasons why we believe they ought not to be considered as canonical.

E. Their Place in the Canon

We believe a good case can be made against ascribing canonical status to the Apocrypha by the following observations:7 (1) The Apocrypha were never part of the Hebrew canon. (2) Although the Septuagint contains apocryphal books, it cannot be proved that the Alexandrian Jews accepted a “wider” canon. (3) The strongest single argument against the canonicity of the Apocrypha is to be found in the NT. Jesus and his apostles obviously did not accept these books as Scripture. (4) Also, the sermons in the Book of Acts indicate how the apostles felt about the Apocrypha. The sermon summaries that Luke gives us in Acts usually span the history of salvation, beginning with Abraham or David, and ending with the fulfillment of God’s promises in Jesus Christ. However, they completely ignore the four hundred-year intertestamental period. We appreciate all the information that the Apocrypha supply for this period of Jewish history, but the apostles did not think that the books written in this period were a continuation of divine revelation.

(5) Persistent uncertainty about the apocryphal books also suggests that they did not have the stamp of God on them, as did the canonical books that were eventually recognized as having divine authority. In fact, only by ecclesiastical authority (Augustine is an example), was resistance to these books suppressed. (6) All attempts at compromise, giving the Apocrypha an intermediate position, are inconsistent. One cannot, for example, read them in public worship and at the same time say that they are not authoritative for doctrine.

Enough has been said, we believe, to suggest that a good case can be made for denying canonical status to the Apocrypha. This does not mean, however, that these books are without value. From a historical and cultural point of view they are really invaluable. Also, one can find high points of religious devotion in them. John Bunyan tells us in Grace Abounding of how God spoke to him through a passage in Ecclesiasticus (2:1). When he discovered that the passage was in the Apocrypha, he felt very uneasy. He finally resolved the conflict by arguing that, although the passage was not canonical, it expressed, even if in different words, what the Bible taught.8

Because the Apocrypha were preserved by the church, they have had a profound influence on a number of areas of life and thought. The language of these books has entered Christian hymnody, influenced Christian art, and has penetrated some of the world’s great literature. Perhaps such influences have been generally quite positive, but unfortunately the Roman Catholic Church has also based its doctrine of purgatory on 2 Maccabees 12:39-45, and that teaching must be rejected.

It can even be argued that the Apocrypha were responsible for the discovery of America, for Christopher Columbus was persuaded by a passage from 2 Esdras (6:42ff.) that six-sevenths of the earth is land and only one-seventh is sea, and that gave him courage to look for new lands beyond the seas.

Nevertheless, as Bruce Metzger says, “When one compares the books of the Apocrypha with the books of the OT, the impartial reader must conclude that, as a whole, the true greatness of the canonical books is clearly apparent.”9

II. THE PSEUDEPIGRAPHA

A. Their Designation

Besides the books that we call Apocrypha, Judaism produced a body of literature that has come to be known as the Pseudepigrapha. These books never made a serious bid for canonical status and we mention them only to indicate that there was a vast number of Jewish books in circulation from which the biblical books were set off. Since the Roman Catholic Church accepts the Apocrypha as canonical, scholars in that tradition at times speak of the Pseudepigrapha as the Apocrypha. One could, however, just as well call some of the apocryphal books pseudepigraphic, for the word simply means that the author of a book writes under a pen name. Moreover, some of the pseudepigraphical books are anonymous, not pseudonymous. Some Protestant scholars, therefore, prefer to speak of the Pseudepigrapha as the “wider Apocrypha.” However, the term Pseudepigrapha is used quite generally today, and we use it here to designate those books, composed by Jewish writers between 200 B.C. and A.D. 200, that fall outside the Hebrew canon and the Apocrypha.

B. Their Number

There is no recognized limit to the number of books in this body of literature. Besides, some books that are listed with the Apocrypha are at times listed with the Pseudepigrapha. R. H. Charles, for example, not only listed 2 Esdras with the Pseudepigrapha, but added three works to the standard list: Pirke Aboth, The Story of Ahikar, and Fragments of a Zadokite Work.10

Together with these four the official list includes some eighteen titles: The Book of Jubilee, The Letter of Aristeas, The Book of Adam and Eve, The Martyrdom of Isaiah, 1 Enoch, The Testament

of the Twelve Patriarchs, The Sibylline Oracles, The Assumption of Moses, 2 Enoch, 2 Baruch, 3 Baruch, 3 and 4 Maccabees, Pirke Aboth, The Story of Ahikar, The Psalms of Solomon, Psalm 151, The Fragment of a Zadokite Work. Today about fifty-two pseudepigraphical books are known.

C. Their Character

For the most part these books were written in conscious imitation of the Hebrew canonical books. Many of them belong to the type of literature called “apocalyptic,” for which the canonical Book of Daniel was the prototype. 1 and 2 Enoch, 2 and 3 Baruch, The Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs, The Sibylline Oracles, and The Assumption of Moses, are apocalypses. Such literature was born out of the fires of persecution during the intertestamental period. Although it has its roots in the OT, it came to full bloom during the Maccabean Revolt. This apocalyptic literature presented a theological view of history that sustained the Jews in their time of trouble. These Jewish apocalypses are a great help in understanding the one great Christian apocalypse that we have in the NT, the Revelation

Besides these apocalypses, there are some legendary books, such as The Martyrdom of Isaiah, that later came to be incorporated in a larger Christian work entitled The Ascension of Isaiah. There are also didactical treatises such as 3 and 4 Maccabees, Pirke Aboth, and The Story of Ahikar. Two books, The Psalms of Solomon and Psalm 151, are poetical in nature, and Fragments of a Zadokite Work is historical.

D. Their Acceptance

At the Jewish Council of Jamnia (A.D. 90) the rabbis banned these “outside books,” as they were called. Evidently the fall of Jerusalem made their message meaningless. More important still, Christians had appropriated some of these books and recast them to fit their own views. Consequently Jewish leaders held them to be heretical.

Among Christians they enjoyed considerable popularity, and the NT gives evidence of their circulation at the time of the apostles. Jude, as mentioned earlier, quotes 1 Enoch 1:9 in Jude 14-15. Also, the reference in Jude 9 to the dispute of Michael, the archangel, with the devil about the body of Moses seems to be a direct allusion to The Assumption of Moses.

The question of the canonicity of the Pseudepigrapha, however, never arose in the mainstream of Christianity, just as it had not in Judaism. Nevertheless, most of them, composed originally by Jews in Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek, have come down to us in the various branches of the Oriental churches in such languages as Syriac, Ethiopic, Coptic, Georgian, Armenian, Slavonic, and others.11

With the discovery of the Qumran materials the body of Jewish extracanonical literature has increased considerably. And while all this literature is invaluable in our study of Judaism in the intertestamental and early Christian period, none of these books are, to use Luther’s words regarding the Apocrypha, “to be equated with Holy Scripture.”

SUGGESTED READING

Bruce, F.F. The Books and the Parchments, 3rd rev. ed. Old Tappan: Revell, 1963. See “The Apocryphal Books,” pp. 163-75.

Charles, R. H. ed. The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha in English with Introductions and Critical Notes, 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1913.

Dentan, R. C. The Apocrypha, Bridge of the Testaments. Greenwich: Seabury, 1954.

Filson, F. V. Which Books Belong in the Bible? Philadelphia: Westminster, 1957.

Geisler, N. L. and Nix, W. E. From God To Us. Chicago: Moody, 1974. See “The Extent of the Old Testament Canon,” pp. 86-100.

Harrison, R. K. Introduction to the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1969. See “The Apocrypha,” pp. 1,173-1,276.

Metzger, B. M. ed. The Apocrypha. New York: Oxford University Press, 1965.

Rowley, H. H. The Relevance of Apocalyptic: A Study of Jewish and Christian Apocalypses from Daniel to Revelation, rev. ed. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1955.

Russel, D. S. The Method and Message of Jewish Apocalyptic. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1964.

Young, G. D. “The Apocrypha,” Revelation and the Bible, ed. C. F. H. Henry. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1958, pp. 171-85.

1 B. M. Metzger, Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1957), p. 5.

2 R. K. Harrison, Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1969), p. 1,185.

3 Metzger, Apocrypha, p. 6.

4 F. F. Bruce, The Books and the Parchments, 3rd rev. ed. (Old Tappan: Revell, 1963), p. 166.

5 R. H. Pfeiffer, “The Literature and Religion of the Apocrypha,” Interpreter’s Bible, ed. G. Buttrick (Nashville: Abingdon, 1952), Vol. 1, p. 393.

6 Pfeiffer, “The Literature of the Apocrypha,” p. 394.

7 These and other arguments are developed in greater detail by Floyd Filson in his book, Which Books Belong in the Bible? (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1957).

8 J. W. Wenham, Christ and the Bible (Downers Grove: Inter Varsity, 1973), p. 126.

9 Metzger, Apocrypha, P. 172.

10 R. H. Charles, The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1913).

11 C. T. Fritsch, “Pseudepigrapha,” Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, ed. G. Buttrick (Nashville: Abingdon, 1962), Vol. 3, p. 963.