Chapter 19

Versions of the English Bible in the Seventies

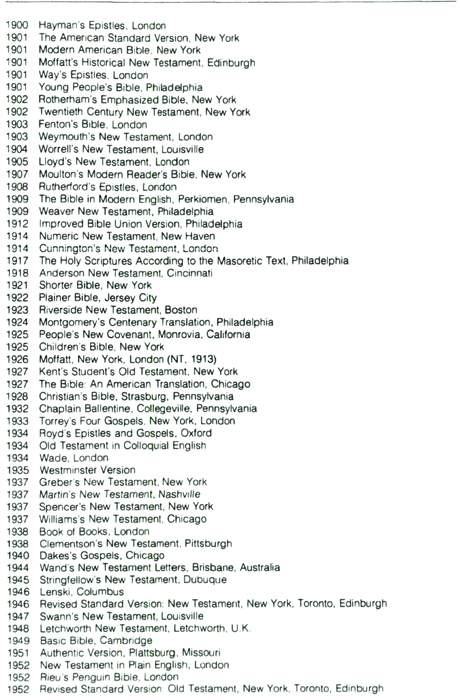

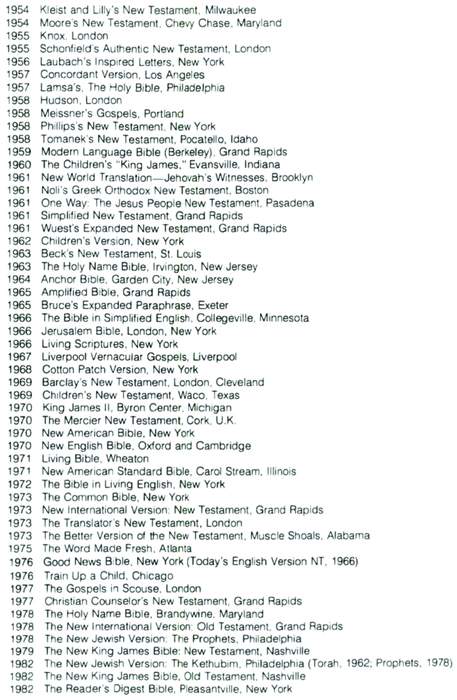

So many versions of the English Bible were competing for readers at the beginning of the seventies that people were calling for a moratorium on new translations for at least a decade. Nevertheless, the seventies witnessed the publication of some outstanding English versions. Some of these were long in the making and actually had their beginnings in earlier decades. In this chapter we want to comment on several major versions that were published in the past decade.

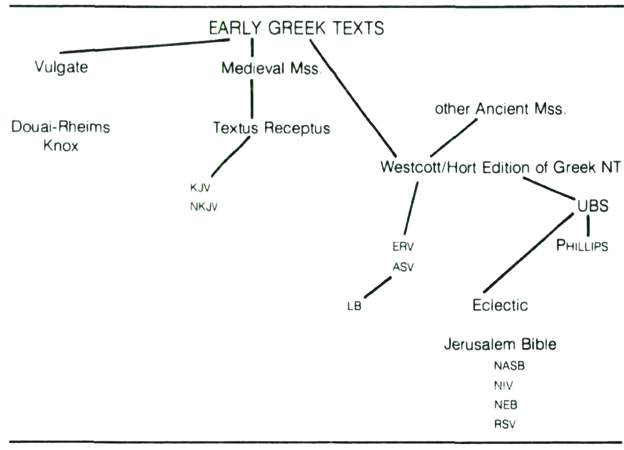

So far we have said little about English versions produced by Roman Catholic scholars, and perhaps that is a good place to begin. The Douai-Rheims-Challoner version was the standard English Bible for Roman Catholics well into the twentieth century, although other versions produced by Catholic scholars appeared from time to time. Ronald Knox, in 1949, published a lively translation of the Latin Vulgate (NT in 1945). But when the Pope granted Catholic scholars permission to translate from the original Hebrew and Greek, enthusiasm for producing new and accurate versions sprang to life. We want to mention two major Catholic versions of the English Bible that were published as complete Bibles about the beginning of the seventies.

I. RECENT ROMAN CATHOLIC VERSIONS

A. Jerusalem Bible

This version (JB) has the distinction of being the first complete Catholic Bible translated into English from the original languages. Previously, all translations in the Catholic Church were made from the Latin Vulgate.

The JB owes its inception to the Dominican School of Bible and Archaeology in Jerusalem, which from 1948 onwards, under the leadership of Roland De Vaux, produced the French La Bible de Jerusalem in a series of volumes with textual notes. A one-volume edition of the whole work, with the notes abridged appeared in 1956. The Jerusalem Bible is the English counterpart of this French version, prepared by Catholic scholars under the leadership of Alexander Jones, of Christ’s College, Liverpool. Among the notables working on this translation was J. R.Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings. The English version of the Jerusalem Bible was published in 1966.

The notes to the books of the Bible have been translated from the French version, but the JB is not simply a translation of the French JB The translation of the English JB was done from the Hebrew and the Greek. The JB has much that will commend itself to both Catholics and Protestants, although some of the notes will probably offend Protestants. For example, the brothers of Jesus in Matthew 12:46, are said to be “not Mary’s children, but near relations, cousins perhaps.” A footnote on Matthew 1:24 states, “The text is not concerned with the period that followed and, taken by itself, does not assert Mary’s perpetual virginity which, however, the gospels elsewhere suppose and which the Tradition of the Church affirms.” A footnote to Matthew 16:18 reads, “The keys have become the traditional insignia of Peter.” Because of the many notes, this Bible of 2,062 pages weighs just under five pounds. The Apocrypha, as they are called by Protestants, are found where they stand in the Septuagint and Vulgate. The text is printed in sense paragraphs and in one column per page.

A courageous break with tradition is seen in its use of “Yahweh” for the ineffable name, instead of the hybrid form “Jehovah,” or the more common translation into English as “LORD.” Also, the names of biblical characters are given in the form usually found in Protestant Bibles. In addition it has the “Sea of Reeds” for the Hebrew Yam Suph, instead of the “Red Sea.”

The English of the JB is considerably freer than that of the RSV. The JB contains more poetry than any other English version. It is of such high quality that many Protestants use it with great profit. To give just a taste of this translation we give the JB’S rendering of a familiar passage: “Do not model yourselves on the behavior of the world around you, but let your behavior change, modelled by your new mind. This is the only way to discover the will of God and know what is good, what it is that God wants, what is the perfect thing to do” (Rom. 12:2).

B. The New American Bible

If the English Protestant NEB was a sort of counterpart to the American RSV, the New American Bible (NAB) was the American Catholic counterpart to the English JB. Although the NAB was produced by the Catholic Church, several Protestant scholars were asked to assist in the project.

The NAB was in the making for several decades and was known originally as The Confraternity Version. The NT part was published in 1941, and in 1969 the OT was completed (including the Apocrypha). Since the NT had originally been done from the Vulgate (prior to the Pope’s encyclical in 1943, permitting translation from the original languages), it now had to be retranslated from the Greek, and so the finished product of NAB was published in 1970.

This Bible has introductions to each book of the Bible. The text is set out in paragraph form with verse numbers in small type. At the end of the Bible is an article on divine revelation, a glossary of biblical terms, and a survey of biblical geography with some maps. The footnotes are fewer in number and less Catholic in nature than those of the JB. A footnote to John 21:15ff. has it that “The First Vatican Council cited this verse in defining that the risen Jesus gave Peter the jurisdiction of supreme shepherd and ruler over the whole flock.” Unlike the JB the NAB prefers “LORD” to “Yahweh.”

The English of the NAB is smooth, but not as colorful as that of the NEB. It is faithful to the original, but not in the word-for-word sense. Some renderings are striking: “In your prayers do not rattle on like the pagans” (Matt. 6:7); “The mouth speaks whatever fills the mind” (Matt. 12:34); “you…leave the inside filled with loot and lust” (Matt. 23:25). Unfortunately it translates agape by “charity.” It translates the same Hebrew or Greek word in a variety of ways in different context. For example, the Greek makarios is given once as “blest,” then as “happy,” or “fortunate” or “pleased.” The word basileia is given as “kingdom,” “reign,” “kingship,” “dominion,” and “nation.”

The entire work is a remarkable achievement.1

II. THE NEW AMERICAN STANDARD BIBLE

The Lockman Foundation, a nonprofit Christian corporation of La Habra, California, published the Gospel of John in 1960. This was followed by the four Gospels in 1962, the NT in 1963, and the entire Bible in 1971. This Bible is known as the New American Standard Bible (NASB)—also called the New American Standard Version (NASV).

The Lockman Foundation was concerned that the ASV of 1901, that “monumental product of applied scholarship, assiduous labor and thorough procedure,” as the revisers speak of it, was fast disappearing from the scene. The Foundation felt called to rescue this noble version from inevitable demise.

A group of some sixteen men worked on each Testament. The twofold purpose of the editors was (1) to adhere to the original languages of the Bible, and (2) at the same time to obtain a fluent and readable style of current English.

For the NT the twenty-third edition of the Nestle Greek NT was followed in most cases, and this called for a number of changes in the ASV of 1901. For the OT, which was published in 1971, after about ten years of work, the revisers followed the latest edition of Kittel’s Biblia Hebraica, correcting it only occasionally.

Instead of having sense paragraphs, as in the ASV and many other modem versions, the NASB reverts back to the pattern of AV in that each verse is printed as a separate unit. Like RSV it has dropped the “thou,” “thee,” and “thy,” except when the Deity is addressed; and the pronouns when referring to the Deity are capitalized (an unnecessary innovation).

In the NT the NASB was concerned to bring out the difference between the Greek imperfect and aorist tenses. This often makes the English rather pedantic. Would a good English writer say: “And He was teaching them many things in parables, and was saying to them in His teaching…” (Mark 4:2-3)? Many imperfects are interpreted as “inceptive": “Now Jesus started on His way with them” (Luke 7:6). Where the “historical present” is used (i.e., the present tense for a past event), this is indicated by the use of asterisks. This is an attempt to convey the Greek but it is not really good English.

One point at which the NASB departed from the ASV is in the use of “LORD” instead of “Jehovah” for the Tetragrammaton YHWH. The Semitic idiom “and it came to pass,” has been slightly modernized to read, “and it came about” or “and it happened.”

A practice, begun by the Geneva Bible, is continued by the NASB, namely to not words that are not in the original, but that are necessary to make the sense clear in English, in italics. The NASB, however, has not been consistent in this practice.

The NASB represents a conservative and somewhat literal approach to translation. In its concern to be accurate, it has failed to be idiomatic and fluent. Kubo and Specht observe that, “Its stilted and nonidiomatic English will never give it a wide popular appeal. It does, however, have great value as a study Bible, and this is perhaps its significant place as a translation.”2 F, F. Bruce makes the interesting comment: “If the RS.V had never appeared, this revision of the ASV. would be a more valuable work than it is. As things are, there are few things done well by the NASB which are not done better by the R.S.V..”3 Dr. Bratcher of the American Bible Society writes: “The NASV language is not really contemporary, the English is not idiomatic, and one wonders whether the revisors have reached their goals of making this Bible understandable to the masses’.”4

It is, however, widely used among evangelical Christians in America.

III. THE LIVING BIBLE

Kenneth Taylor had foryears felt the need of having a Bible in modern understandable English. He noticed when he conducted family worship that his children were often puzzled by the strange English of the KJV. He tried, therefore, to explain the passages in simple, everyday English that they could understand. This led to his first systematic attempt, in 1956, to produce a written paraphrase of an entire book of Scripture. He did this

Kenneth N. Taylor, President of Tyndale House Publishers. Dr. Taylor produced The Living Bible, a paraphrase of Scripture.

while riding the commuter train between his home in Wheaton and his office in Chicago, where he worked at Moody Press.

In 1959 Moody Press published his Romans for the Children’s Hour. This was followed in 1962 with Living Letters. To begin with he couldn’t get a publisher for these, so he printed 2000 copies on his own and took them to the Christian Booksellers Convention. Orders came slowly, but in 1963 Billy Graham, while confined to a hospital in Hawaii, read Living Letters, and ordered 50,000 for his television audience. The response was so overwhelming that Taylor eventually left Moody Press and launched his own Tyndale House publishing firm.

In 1965 Living Prophecies appeared, the Living Gospels, in 1966, and the Living New Testament, in 1967. The complete Living Bible (LB) came from the press in 1971. The translation of the entire Bible had taken him fifteen years (part-time)—seven on the NT and eight more on the OT.

Taylor’s goal was to paraphrase, and the basic text for this paraphrase was the ASV of 1901. In one sense all translations are paraphrases. If one tries to restate the original author’s thought in a different language, one has to paraphrase. For example, the French salutation, Comment vous portez-vous, if translated literally into English would be, “how do you carry yourself?” But the English equivalent is, “How do you do?” That is paraphrase, but it is also a reasonably exact translation. The question is, how far one takes the paraphrase. Moreover, if one paraphrases an already existing English version of the Bible, as Taylor did, one is paraphrasing a paraphrase, for the ASV is already, in one sense, a paraphrase of the Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek of the original text. Taylor did, however, seek the assistance of Hebrew and Greek specialists, for he was concerned about accuracy also, and not just about the English.

In his preface, Taylor admits that there are dangers in paraphrasing, and where the Hebrew and Greek were not clear, the theology of the translator along with his sense of logic was his guide. “The theological lodestar in this book has been a rigid evangelical position.” One cannot fault Taylor for this theological position, but a good translator keeps his theology out of the translation. To have a “rigid evangelical position” calls, above everything else, for faithfulness to the original text—something that Taylor does not always accomplish.

"This generation shall not pass away until all these things be accomplished” (Mark 13:30) may not be an easy text to explain, but Taylor’s “Yes, these are the events that will signal the end of the age,” bears hardly any similarity to the original wording (nor meaning, for that matter). In order to make OT passages apply to the modern state of Israel, he even uses the term “Israelis “: “The Lord will have mercy on the Israelis; they are his special ones” (Isa. 14:1). He renders Zephaniah 3:8, “at that time I will change the speech of my returning people to pure Hebrew” (but the Hebrew text has simply “pure speech”). In Romans 4:9 circumcision is described as “keeping the Jewish rules.” However, circumcision was commanded by God. John 1:17 is particularly infelicitous: “For Moses gave us only the law with its rigid demands and merciless justice, while Christ brought us loving forgiveness as well.” Is that really what the text says?

On occasion Taylor will use rather current euphemisms. For example, Eglon’s servants thought “that perhaps he was using the bathroom” (Judg. 3:24). Then again, Taylor resorts to vulgar expressions (see 1 Sam. 20:30 in the first edition):

Perhaps Bruce is right when he speaks of the LB as a “simplified Bible for children,”5 for to render the profound expression “the righteousness of God” simply as “a different way to heaven,” may satisfy children, but is hardly adequate for adult Bible readers.

Some evangelical Christians react very negatively to a paraphrased Bible. In spite of its great popularity, an evangelist in North Carolina recently led students of a Christian high school in a Bible burning ceremony. The Living Bible, explained the evangelist, was a “perverted commentary on the King James Version,” and so, together with rock-and-roll records, the Living Bible was publically burned.6

However, the LB is very popular today. Some twenty-five million copies have been sold by now. This is due largely to its English. Carl F. Henry writes, “Those who prefer to read the Bible in the language and style of the morning paper or of television newscasting will feel fully at home with the Living Bible.”7 Dr. La Sor of Fuller Seminary comments: “For just enjoying Bible reading this is great, but for serious Bible study it is insufficient.”8

It is available today in many editions: hardback, red letter, self-help, indexed, reference, large print, leather, for children and young people, and special Catholic editions. For people who do not know “Bible English” the LB can bring home the message of Scripture in terms they can understand.

IV. THE GOOD NEWS BIBLE

A. The Publication

In 1966 the American Bible Society published a modern speech version of the NT, called Good News for Modern Man: The New Testament in Today’s English Version (TEV). Its popularity was so great that a year later (1967) a second edition was published. This edition had already incorporated many changes in style and substance. Further improvements were made and in 1971 a third edition appeared. During the first six years of its existence some thirty-five million copies were sold worldwide,9 and by the time the OT was ready, fifty million copies had been sold.

The OT part of the TEV has now also been completed, and together with the fourth edition of the NT the entire Bible was published in 1976 as the Good News Bible (GNB). Because of differences between British and American English, separate editions were prepared. Since then the GNB has appeared in several other languages.

Dr. Robert Bratcher, assisted by others, did the translation of the NT. For the OT the American Bible Society appointed a group of seven translators, all of whom had doctorates in

9Herod said, “I had John’s head cut off; but who is this man I hear these things about?” And he kept trying to see Jesus.

Jesus Feeds Five Thousand Men (Matthew 14.13-21; Mark 6.30-44; John 6.1-14)

10The apostles came back and told Jesus everything they had done. He took them with him, and they went off by themselves to a town named Bethsaida. 11When the crowds heard about it, they followed him. He welcomed them, spoke to them about the Kingdom of God, and healed those who needed it.

12When the sun was beginning to set, the twelve disciples came to him and said, “Send the people away so that they can go to the villages and farms around here and find food and lodging, because this is a lonely place.”

13But Jesus said to them “You yourselves give them something to eat.”

They answered, “All we have are five loaves and two fish. Do you want us to go and buy food for this whole crowd?” 14(There were about five thousand men there.)

Jesus said to his disciples, “Make the people sit down in groups of about fifty each.”

15 After the disciples had done so, 16 Jesus took the five loaves and two fish looked up to heaven, thanked God for them, broke them, and gave them to the disciples to distribute to the people. “They all ate and had enough, and the disciples took up twelve baskets of what was left over.

Peter’s Declaration about Jesus (Matthew 16.13-19; Mark 8.27-29)

18One day when Jesus was praying alone, the disciples came to him. “Who do the crowds say I am?” he asked them.

19“Some say that you are John the Baptist,” they answered. “Others say that you are Elijah, while others say that one of the prophets of long ago has come back to life.”

20“What about you?” he asked them. “Who do you say I am?”

Peter answered, “You are God’s Messiah.”

9.19 Mt 14.1-2; Mk 6.14-15; Lk 9. 7-8 9.20 Jn 6.68-69

This page from the Good News Bible is typical of its contemporary design and art.

biblical studies and who had been (with one exception) missionaries in other lands. These worked under the chairmanship of Dr. Bratcher. A British consultant appointed by the British and Foreign Bible Society participated in this undertaking.

The preface to the GNB explains that this version is prepared both for those who speak English as their mother tongue as well as those who have acquired the English language. It is a distinctly new translation and does not conform to traditional vocabulary or style, but seeks to express the meaning of the original text in words and forms accepted by English-speaking people everywhere.

The version uses a limited vocabulary simple grammatical constructions, short sentences, and common language. Where possible it uses modrn equivalents for such cultural items as Jewish instructions and customs, weights, measures, money, and hours of the day. That means it often uses terms not found in the original Greek. Since the English of the version was to be universal, the translators have avoided colloquialisms and, as much as possible, Americanisms. Idioms that are usually understood only in one language, are also avoided.

The NT was first marketed as a paperback, and illustrated by line drawings by Mile. Annie Vallotton, a Swiss artist living in Paris. Now the entire Bible is available with line drawings. A word list at the end of the NT explains technical terms and rare words. It also has a fine set of maps.

Modern printing format is followed; verse numbers are placed in the text to enable readers to locate them. The text itself is divided not into verses but into relatively short paragraphs with headings to identify the content of each section.

From this description one can already gather some of the principles of translation that guided the translators.

B. The Policies

For the OT the translators used the third edition of Kittel’s Biblia Hebraica as their basic text. In some cases emendations were made or the ancient versions were followed. Such departures from the Hebrew text are always indicated in the footnotes. In the case of the NT, the basic text was the third edition of The Greek New Testament, published by the United Bible Societies (1975).

The first aim of the translators was to provide an accurate rendering of the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek into English. All aids available were used to establish the original meaning—something not always possible, of course. After establishing as carefully as possible the original meaning, the translators tried to express this in simple English. Obviously, then, this is not a word-for-word translation. Rather, the translation is based on the principle of “dynamic equivalence.” The translator seeks to give the “sense” of the original in such a way that the present readers are stimulated to react to the message in the same way the biblical author hoped his first readers would respond. This is naturally a goal that can be achieved only approximately. “Dynamic equivalence” is the golden mean between a paraphrase and a translation in which we have simply a word correspondence. It is a meaning-for-meaning translation.

The translator wants to be true to the message of the original text, but makes no attempt to translate the Hebrew and Greek words by English equivalents. The question is: “How would the original author have said this if he had spoken English?” In one sense this is not a novel view of translating, since Martin Luther followed a similar principle when he translated the Bible into his native German.

Besides being true to the sense of the original, the translators aimed at using commonly spoken English, avoiding both slang and elitist terms. A special concern of the translators was to use a language that non-Christians, who are unfamiliar with “Bible English,” could understand. To show the difference in English between the RSV and GNB, let us note the following: “mad” is changed to “crazy” (1 Cor. 14:23); “pillars” of the church are “leaders” (Gal. 2:9); “to ask for alms” becomes “to ask for money” (Acts 3:8); “blasphemy” is “to talk against God” (Matt. 9:3); “redeemed” is “to set free” (Luke 1:68). In the OT, Noah’s ark is a “boat” (Gen. 6:14); Moses’ ark of bulrushes is a “basket made of reeds” (Exod. 2:3); the mercy-seat is “the lid on the Covenant Box” (Lev. 16:2); the Ethiopians of Psalm 68:31 become “the Sudanese.” “Caesar” becomes “Emperor,” “centurion” becomes “army officer,” “publicans” are “tax-collectors,” the “sanhedrin” is the “Council.”

Technical religious terms are also recast. “Bishops” are “church leaders,” “deacons” are “church helpers,” “mammon” is “money.” Where it was not feasible to give modern equivalents, the biblical words are explained in the glossary at the back.

People not used to theological language will appreciate the fact that “repent” is translated at times as “turn away from your sins.” To be “justified” is “to be put right with God.” “Reconciliation” is “changing us from God’s enemies into his friends.” “Propitiation” is “the means by which our sins are forgiven.” The word “destruction” is occasionally rendered as “hell,” as in the case of Peter, who tells Simon Magus, “May you and your money go to hell” (Acts 820).

A special problem for translators is the handling of figures of speech and idioms. “The finger of God” now becomes “God’s power” (Luke 11:20); “cut to the heart” is changed to “deeply troubled” (Acts 2:37); “He does not bear the sword in vain” becomes “his power to punish is real", “a wide door” is a “real opportunity” (1 Cor. 16:9).

Semitisms are also erased: “Son of peace” is a “peace-loving man” (Luke 10:6); “daughter of Abraham” becomes a “descendant of Abraham” (Luke 13:16); “Father of glory” is “glorious Father” (Eph. 1:17); “children of the flesh” are “children born in the usual way” (Gal. 4:22-23). Amos’s “for three transgressions of Damascus, and for four,” becomes “the people of Damascus have sinned again and again” (Amos 1:3). The “Preacher” of Ecclesiastes becomes the “Philosopher” (Eccl. 1:1).

C. The Reception

Dr. Eugene Nida, who played a major role in the production of the Good News Bible, tells of a man in the southern states who was warned that he would be shot if he kept on distributing the GNB.10 Fortunately, the response by and large has been overwhelmingly positive. A little girl, after reading the GNB, exclaimed, “Mommy, it must not be the Bible—I can understand it.”11

For the first two weeks after the GNB appeared it was a celebrity in America. All three national TV networks carried stories on this version. More than a thousand newspapers in the country carried articles on it.

But attacks on the GNB were not slow in coming either. The translators were charged with denying the virgin birth because Luke 1:27 reads, “He had a message for a girl promised in marriage to a man named Joseph.” However, in Luke 1:34 Mary says, “I am a virgin.” So the charge is unfounded. The word “virgin” was often used in those days for unmarried girls, as in Matthew 25:1ff., where the kingdom of heaven is said to be like ten “virgins.” Where virginity is in question, there the GNB has “virgin,” but where the reference is to unmarried girls, it does not.

The charge was made also that the translators denied the “blood,” for the GNB renders Ephesians 1:7, “For by the death of Christ we are set free.” The “precious blood of Christ” by which we are redeemed is given in this form: “By the costly sacrifice of Christ, who was like a lamb without defect or spot” (1 Peter 1:19). “Blood” is understood as a metaphor for “death.” One can illustrate this from a passage where the atonement is not in focus: “Whose blood Pilate had spilled” (Luke 13:1), is given as, “whom Pilate had killed.” No one should object to that rendering, for to spill someone’s blood is to kill him. And to be redeemed by Christ’s blood means to be rescued by his death.

Also, the translators were accused of denying the deity of Christ. Where the KJV reads: “Joseph and his mother knew not of it” (Luke 2:43), TEV has, “His parents did not know this.” The objection to the word “parents,” however, is without foundation, for the Greek in fact has “parents.” It was an error on the part of the King James translators to substitute “Joseph and his mother” for “parents” (Greek: goneis).

Like other versions, the GNB has its weaknesses but on the whole it is superbly done. It is both highly readable and accurate. One should not be fooled by its unpretentiousness, for it is, as Ramsey Michaels of Gordon-Conwell Seminary writes, “on balance the best and most accurate English translation of the NT” (he speaks only of the NT, since the OT was not yet published at the time).12

V. THE NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION

A. Initiation and Publication

In the early 1950s some evangelical scholars, who were acutely aware of the archaic language of the KJV, began to envision a version of the Bible in modern English that would do for our day what the KJV did for its day. It was to be a version that could be used in public worship, for private study, and for memorization as well.

The Christian Reformed Church took the initiative by appointing a committee to find an existing version that would be acceptable to all the churches of this denomination. When this failed, they appealed to the National Association of Evangelicals for help, and preliminary plans were made in 1961 to prepare a new translation. In 1965 representatives of a number of denominations met and agreed that there was still a need for a good Bible version in contemporary English. The project received new impetus when the New York Bible Society agreed to sponsor such a version financially.

The governing body of the project consisted of fifteen biblical scholars with Dr. Edwin Palmer as chairman. About one hundred scholars were invited to participate in the translation work. Originally the name was to be A Contemporary Translation, but since some of the translators lived in Canada, England, Australia, and New Zealand, the version came to be called the New International Version (NIV).

The initial translation of each book of the Bible was the work of a small team of scholars who met in places convenient to them, and then submitted their work to an Intermediate Editorial Committee. From here the translation was sent to the Editorial Committee, which again checked it carefully for accuracy. Then it went to stylists and other critics from all walks of life for review and suggestions. The executive Committee, a permanent body of fifteen members, made the final decisions before it was sent to the printer.

As for format, the NIV has the text in sense—rather than verse—paragraphs. The type is large and easily legible. The footnotes are mostly of an explanatory nature. Brackets are used occasionally for words not in the original but called for to make the sense

The late Edwin H. Palmer served as chairman of the committee that produced the New International Version.

plain. It no longer uses “thou,” “thee,” and “thine” in reference to the Deity.

For the OT the translators used the latest edition of Kittel’s Biblia Hebraica, and where the reading of the Hebrew was doubtful the ancient versions were consulted. The Greek text for the NT was an eclectic one. Where the manuscripts differ, the translators had to come to a consensus on which reading to follow. Generally, they followed the text that now appears in the current Greek New Testament.

The project turned out to be very costly and at times it seemed as if the Bible Society, which changed its name to New York International Bible Society, would go bankrupt. Zondervan, who was to be the publisher, advanced some monies, and with the contribution of private donors the work was completed.

The NT of the NIV was ready in 1973, and in 1978 the OT together with the NT was printed as the New International

Version. Hodder and Stoughton printed the British edition of the NIV.

B. The Quality of the Version

A version is always judged on the basis of faithfulness to the original text and on its readability. The NIV has achieved both of these goals reasonably well. It is both accurate and clear. While the language may not be as colorful as that of Phillips or the NEB, it is more modern than that of the RSV. The RSV, of course, was a revision of the ASV, whereas the NIV is a completely new translation.

F. F. Bruce writes of this version: “An admirable version, combining fidelity to the NT text with sensitivity to modern usage. The avowedly conservative stance of the translators has not resulted in any bias in their work; it has rather enhanced the sense of responsibility with which they have undertaken their task.”13 Robert Mounce says it’s “a sort of evangelical RSV…[which] may become the all-purpose translation for evangelical churches in spite of the plethora of recent modern speech versions.”14 When a student asked Dr. La Sor of Fuller Seminary why the NIV had been published, he answered somewhat facetiously, “So evangelicals won’t have to use the RSV.”15 He goes on to say that the NIV does not have the freshness of the GNB or the high style of the NEB, nor the stilted style of the NAB.16

The NIV is undoubtedly a monument to evangelical scholarship and one of the best all-purpose Bibles available to English-speaking Christians.

SUGGESTED READING

Bruce, F. F. History of the Bible in English, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. See pages 235-68.

Kubo, S. and Specht, W. So Many Versions? Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1975. See pages 163-99.

Lewis, J. P. The English Bible/From KJV to NIV. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1981. See “The Jerusalem Bible,” pp. 199-214; “The New American Bible,” pp. 215-28; “The New American Standard Bible,” pp. 165-98; “The Living Bible Paraphrased,” pp. 237-60; “The Good News Bible” pp. 261-92; “The New International Version,” pp 293-328.

1 S. Kubo and W. Specht, So Many Versions? (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1975), p. 171.

2 Kubo and Specht, So Many, p. 179.

3 F. F.Bruce, History of the Bible in English, 3rd rev .ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), p. 259.

4 R. Bratcher, “Old Wine in New Wineskins,” Christianity Today Vol. 23 (october 8, 1971), p. 16.

5 F. F. Bruce, “Which Bible Is Best for You?” Eternity Vol. 25 (April 1974), p. 29.

6 “Living Bible Burned,” Christian Century Vol. 98 (July 1981), p. 696.

7 C. F. Henry, “The Living Bible,” Christianity Today Vol. 25 (Sept, 4, 1981), p. 98.

8 W. La Sor, “Which Bible Is Best for You?” Eternity Vol. 25 (April 1974), p. 29.

9 Kubo and Specht, So Many, p. 140.

10 E. A. Nida Good News for Everyone (Waco: Word, 1977), p. 11.

11 Nida, Good News, p. 10

12 R. Michaels, “Which Bible Is Best for You?” Eternity Vol. 25 (April 1974), p. 30.

13 Bruce, “Which Bible,” p. 28.

14 Mounce, “Which Bible,” p. 29.

15 W. La Sor, “What Kind of Version Is the New International?” Christianity Today Vol. 23 (October 20, 1978), p. 18.

16 La Sor, “What Kind of Version,” p. 18.