1) SLYLY

2) TYPEWRITER: The question asked for a word that uses only the ten keys, not that uses every one of them.

3) TONIGHT

4) June July August September October November December January February March April May

5) EXTRAORDINARY

6) F for forty: The sequence is the first letters of the numbers from seventeen to thirty-nine.

7) EARTHQUAKE

8) Remove the first letter and each of the remaining letters form palindromes, meaning they are the same forward and backward: ssess, anana, resser, rammar, otato, evive, neven, oodoo

9) INSTANTANEOUS

10) U. Whenever there are seven in a sequence, think days of the week: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday.

A ruler enables us to draw straight lines. A ruler with a 2-unit interval enables us to draw straight lines and mark out intervals of 2 units. That’s all we have to work with, but it’s enough.

Our solution is based on the principle that two straight lines starting at the same point will diverge at a constant rate. We are looking to find a way to measure the distance between two divergent lines that allows us to create another line that is only 1 unit long. Here’s how we do it.

Step 1. Draw two lines that cross each other. These are our divergent lines. Mark the points that are two units from the intersection down both lines. Using these new points, mark the points that are two units further down.

Step 2. Join the first two points and the second two points with a line. These lines are parallel. Mark point X, which is two units along the bottom line.

Step 3. Draw a line from the intersection to X. Mark the point Y where this line crosses the upper parallel line. The distance along the parallel line to Y, marked in bold below, is 1 unit. We have our answer.

Here’s why it works. I’ve called one of the original lines A and the last line we drew B. The distance from A to B at their intersection is zero. As you move steadily down B, the distance from A to B along any line at a fixed angle increases at a constant rate. So, if a line from A to B at X has length 2, then the parallel line from A to B at Y, which is half the way there, must have length 1.

The rope can be lifted about 120m, which is about the height of the Centre Point skyscraper in central London. Again, the distance seems counterintuitively huge. We have a 40,000km rope around the Earth, and by increasing it to 40,000.001km it lifts up so high that a pyramid of giraffes driving on motorbikes and stacked 20 giraffes high would easily ride through.

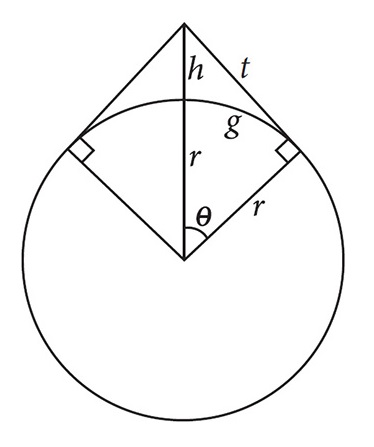

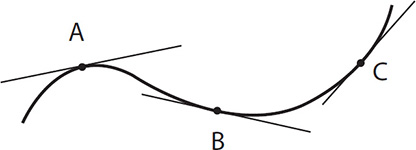

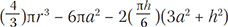

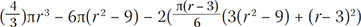

This time, though, the size of the Earth is very much relevant to the answer. The calculation requires some trigonometry, which will be too arcane for most readers, so full marks if you illustrated the problem correctly and thought about how you might solve it. In the diagram here, r is the radius of the Earth and h is what we are after, which is the height of the rope when raised as high as possible without stretching. The length of the rope from its peak to the ground is t, and the distance along the ground when the rope is in the air is twice g.

We can find h in terms of r, but be warned—it’s not pretty. And don’t even think about trying to follow if you never studied trigonometry. First, notice that t is a tangent to a radius, so we have a right-angled triangle in which the hypotenuse is r + h and the other sides are r and t. Using Pythagoras’s theorem:

[1] t2 + r2 = (r + h)2

We know that the cosine of angle θ is r/(r + h), so:

[2] θ = cos–1 r/(r + h)

And, since we are using radians, θr = g:

[3] r cos–1 r/(r + h) = g

We also know from the statement of the question that:

[4] 2g + 1 = 2t

These equations can be rearranged and “simplified”—they can, believe me—to the equation:

And when r = 6,400,000m, h ≈ 122m

There we are. I showed it for completeness, and I promise there is no more trigonometry in this book.

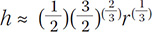

The purpose of this question, like the previous one, is to confront our intuitions about space. The pole will be just over 7m high, about the height of a Victorian two-bedroom house, and way taller than the world’s tallest giraffe. Surprisingly high, right?

Pythagoras gets us there without breaking a sweat. As illustrated here, the pole produces two right-angled triangles.

Each side of the bunting is a hypotenuse, and the ground and the pole are the other two sides. So:

h2 + 502 = 50.52

h2 + 2,500 = 2,550.25

Rearranging, we get:

h2 = 2,550.25 – 2,500 = 50.25

So:

h =  50.25 ≈ 7.1

50.25 ≈ 7.1

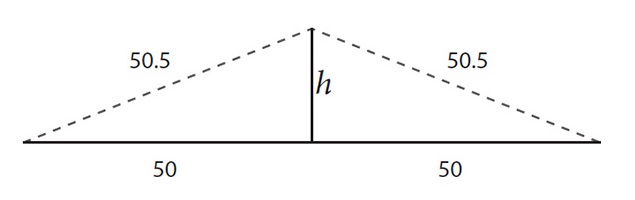

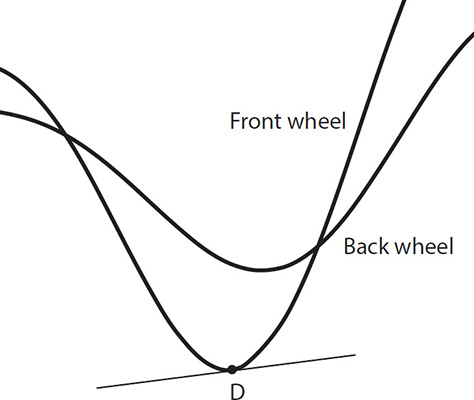

In order to work out which way the bike is traveling we first need to work out which of the tracks is the front wheel and which is the back. For us to be able to make this deduction, dear Watson, we need to understand how the curve of a tire track determines the position of the wheel.

If a tire track is straight, the wheel making that track is in line with the direction of the track. If a tire track is curved, however, the wheel making that track is in line with the tangent of the curve at every point along the track. (The tangent is the line that touches a curve only at a single point). To see what I mean, consider the track below, made by a unicycle. When the wheel was at points A, B, and C, it was in line with the tangents, which I’ve marked.

Bicycles have two wheels. The front wheel is free to point in any direction. But the back wheel has no freedom of direction—it must always be pointing in the direction of the front wheel.

Wherever the back wheel is, therefore, the front wheel is exactly one bicycle-length ahead of it in the direction of the tangent. In other words, all the tangents from the back wheel’s track must cross the front wheel’s track, and they must all do so one bicycle-length away.

Now look at point D above on the bold line. Its tangent does not cross any track at all. We can deduce, therefore, that D does not sit on the back wheel track. It sits on the front wheel track.

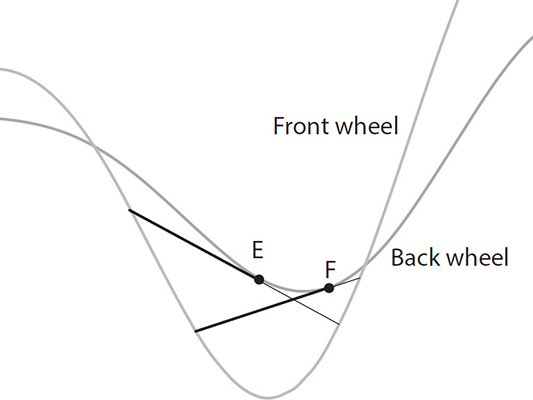

Finally, we can find the bike’s direction. We know which track was made by the back wheel, and we know from above that one bike-length along any tangent on that track in the direction of travel is a point on the front wheel track. So all we need to do is follow the tangent segments in both directions from E and F and see where they cut the front wheel track. The segments from E and F toward the left are of equal length, but the segments from E and F toward the right are not equal. Since the distance between wheels does not change during travel, the bike was going from right to left. Elementary.

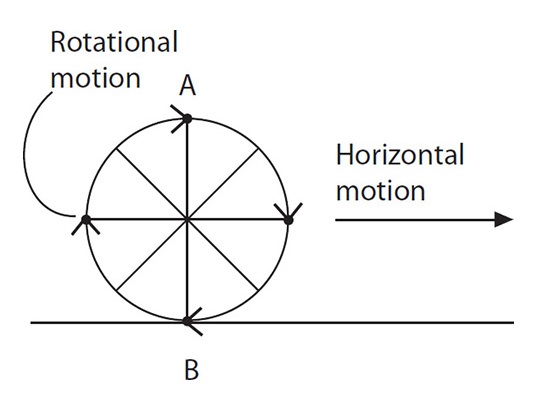

I wheelie love this question because it illustrates a curious phenomenon: The top of a wheel always travels faster than the bottom.

When a wheel rolls along a horizontal surface, the points on the wheel are subject to two different directions of motion: They are moving horizontally, in the direction of travel, but also rotationally, around the center of the wheel. These two directions of motion combine, and sometimes cancel each other out. Consider point A on the wheel below. Because point A is at the top of the wheel, both its horizontal and its rotational motion are aligned. But at the bottom, point B’s horizontal and rotational motion are in opposite directions, and cancel each other out. From the perspective of someone watching, the point at the top of a rolling wheel is always traveling at twice the horizontal speed of the wheel, and the point at the bottom is always stationary. It follows that the points on the bottom half of the wheel are moving slower than the points on the top half.

The answer, therefore, is the second image, where the pentagon is blurred above but sharp below. This would happen when the exposure time of the photographer’s camera is short enough to get a crisp image of the slower pentagon but not the faster one. If you are an artist you may have understood this instantly—the tops of moving wheels are often drawn as a blur.

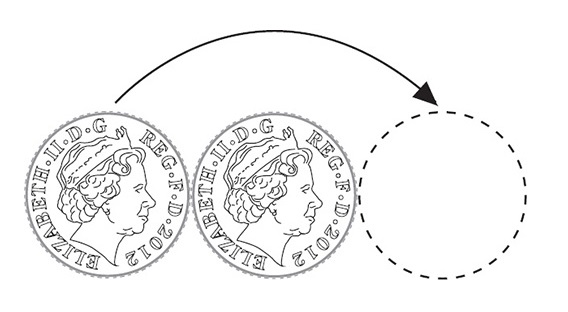

The answer that you probably got was (b) 3, which is what the examiners thought was the correct answer.

The calculation they wanted the students to do was as follows. If the radius of A is a third of the radius of B, then the circumference of A is a third of the circumference of B (since the circumference is 2π times the radius). You can therefore fit three circumferences of A around a single circumference of B. When A rolls for a full rotation it covers a single circumference. So it must roll for three full rotations to complete three circumferences, which is the circumference of B.

Their mistake is hard to spot unless you have studied the behavior of circles rolling around circles. The examiners evidently hadn’t. But let’s do it now. Take two identical coins and roll one around the other. The coins have the same circumferences, so you might expect (like in the SAT question) the rolling coin to revolve only once before it gets back to its starting point. Yet the queen’s head will revolve twice! When a circle rolls around a circle you need to add an extra rotation, to account for the fact that it is rolling around itself and the other circle.

Had the SAT question been “How many times will A rotate along a straight line of length equal to the circumference of B?,” the answer would have been three. But when A rotates around B the answer is four.

The correct solution was not one of the multiple choice answers, which explains why almost no one got it right. The repercussions were embarrassing for the examiners: When their mistake was discovered the story appeared in the New York Times and the Washington Post.

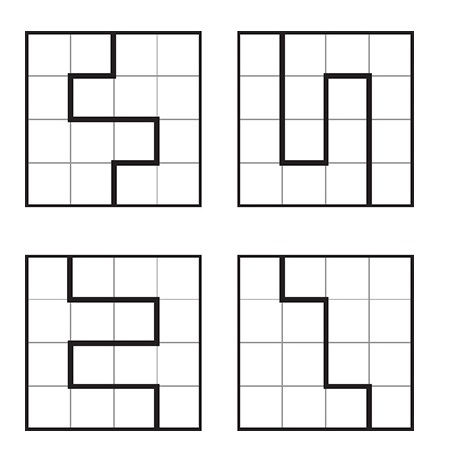

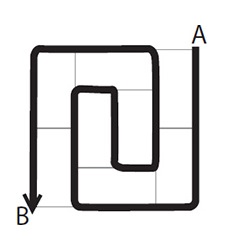

The sheet directly underneath 1 can only be the sheet in the top left corner. The sheet directly underneath the top left corner has to be the one below it. And so on as the sheets spiral counterclockwise.

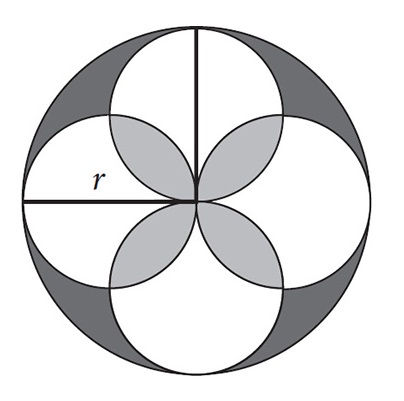

This problem becomes easier to understand if we pan out. Place four identical quarter circles together to get a big circle that comprises four smaller circles that overlap.

If r is the radius of the big circle, then the area of the big circle is πr2.

The smaller circles have half the radius of the big one, so the area of each small circle is  .

.

This is neat. The small circles each have exactly a quarter of the area of the big one, so the area of four small circles is equal to the area of the big one. This equivalence in area is extremely helpful to us, since the image includes four small circles.

The small circles overlap. What is the total area of these four overlapping circles?

The area is equal to the area of four small circles (πr2) minus the area of the overlap, which is the lenses.

[1] Overlapping circles area = πr2 – area of lenses

We can also see that the area of the big circle (πr2) minus the wings is equal to the overlapping circles.

[2] Overlapping circles area = πr2 – area of wings

Combining these two equations, we get:

πr2 – area of lenses = πr2 – area of wings

Clearly, then, the area of the lenses is equal to the area of the wings. Since there are four equally sized wings and four equally sized lenses, the area of a single wing equals the area of a single lens.

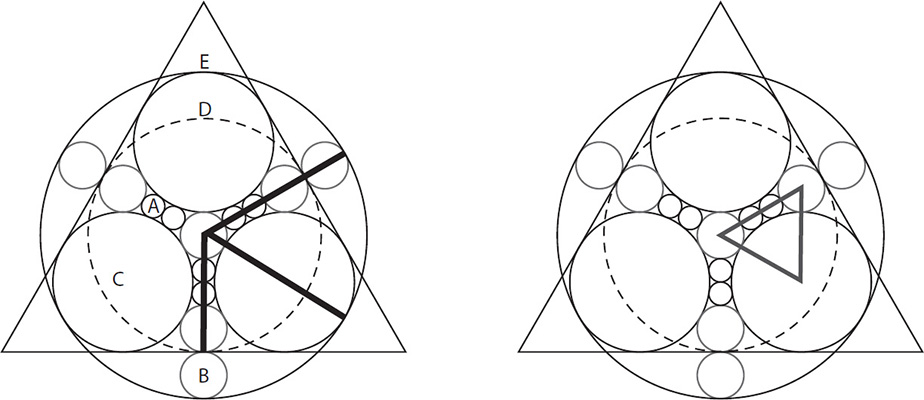

The perfect way in which all the circles fit so snugly together is what makes the image so alluring—and it is also the key to solving the puzzle, since it enables us to compare the circles’ radii.

Let us call the circles, from smallest to largest, A, B, C, D, and E, and let their radii be a, b, c, d, and e. The question asks us to express d in terms of a.

In the first image, I have marked three lines. The vertical one is the radius of D, the dashed circle, but it also corresponds to four radii of A and three of B. So we can write the equation:

[1] d = 4a + 3b

Likewise, the other two thick lines, both radii of E, can be described in terms of other radii:

[2] e = 4a + 5b

[3] e = b + 2c

The clever bit now is to realize that the triangle drawn in the second image is equilateral. That is, the angle at the center of E must be 60 degrees, and two of the sides are equal, so the third side must also be equal. In other words:

[4] 4a + 2b = b + c.

We have four equations with five unknowns. Since we want to know d in terms of a let’s get rid of the other terms.

First, we can lose e by equating [2] and [3].

4a + 5b = b + 2c

So:

4a + 4b = 2c, or:

[5] 2a + 2b = c

Substituting c in [4] gives us:

4a + 2b = b + 2a + 2b, or:

[6] 2a = b

And substituting in [1] gives us:

d = 4a + 6a = 10a

We have the answer: The radius of D is ten times the radius of A.

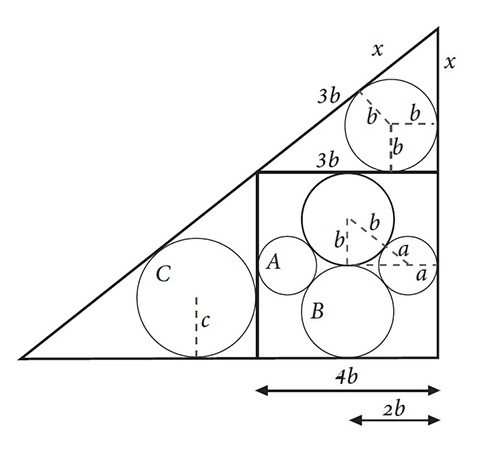

I’ve renamed the circle sizes A, B, and C, and their radii a, b, and c. Our strategy will be first to find b in terms of a, and then c in terms of b, which will allow us to show that c = 2a.

In the illustration on the right I’ve drawn a triangle with a dotted line. The length of the hypotenuse is b + a, because it covers a radius of each circle, and the lengths of the other two sides are b and 2b – a. The second length you can deduce by realizing that the triangle is half the length of the square—which must have length 4b—minus one radius of A.

Pythagoras’s theorem tells us that for right-angled triangles the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides, so:

(b + a)2 = b2 + (2b – a)2

Which expands to:

b2 + 2ab + a2 = b2 + 4b2 – 4ab + a2

Which then contracts to:

6ab = 4b2

And even smaller to:

3a = 2b

And finally to:

b =  a

a

So we have b in terms of a.

Now look at the top triangle in the illustration. I have drawn a line from the center of the circle to each of the sides. Each of these lines meets the side at a right angle, so the triangle is split into a b × b square and two kite shapes. The long side of the kite pointing left is 3b, since it is the width of the large square minus a radius of B. And since kites are symmetrical the other side of the kite must also be 3b. If the side of the right-pointing kite is x, then using Pythagoras on the triangle we get:

(3b + x)2 = (b + x)2 + (4b)2

Expanding, we get:

9b2 + 6bx + x2 = b2 + 2bx + x2 + 16b2

Contracting, we get:

4bx = 8b2

Which is:

x = 2b

The vertical side of the top triangle is x + b = 2b + b = 3b. The vertical side of the bottom triangle is 4b. Since the two triangles are the same shape, although of different sizes, the ratio of the sides of the triangles, which is  =

=  , must equal the ratio of the radii of the circles inside the triangles, which is b/c.

, must equal the ratio of the radii of the circles inside the triangles, which is b/c.

If

Then:

c =  b

b

We now have c in terms of b and b in terms of a.

So c in terms of a is c =  b =

b =  (

( ) a = 2a.

) a = 2a.

This pattern is taken from the 1641 edition of Jinkoki, the most popular Japanese math textbook of the seventeenth century.

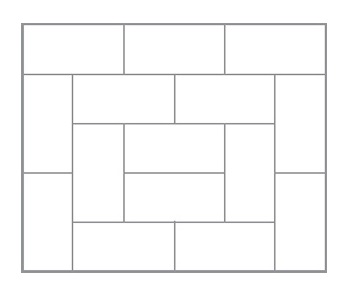

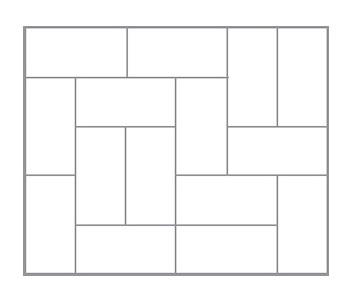

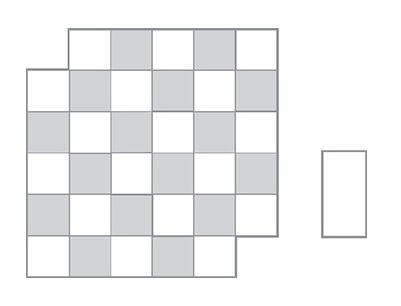

No, tatami mats will not cover the 6 × 6 room with corners removed. If we shade in alternate squares like a chess board, as below, we can see why. Each mat must cover both a shaded square and a white square. So if the room is coverable by mats it must have an equal number of shaded and white squares. But this room has two extra white squares, so covering with mats is impossible.

Usually this question is phrased in terms of dominoes and a “mutilated” chessboard—can dominoes the size of two chess squares tile a chessboard that has had opposite corners cut off? Again, for the same reason, the answer is no.

We show this with a clever technique devised by Ralph E. Gomory, who was director of research at IBM in the seventies. He was thinking about dominoes on a chessboard, but the proof is the same. First, draw a path through the room that visits every square just once, as shown below. In the second image, I have removed one shaded and one white square arbitrarily for the staircases, which cuts the path into two sections. Each of the two sections of the path must cover an even number of squares, and can therefore be covered by tatami mats. The argument follows for all paths, and all choices of two differently colored squares.

This question was suggested to me by Joseph Yeo Boon Wooi, the Singaporean author of the Cheryl’s Birthday problem (Problem 21), who had first read about it in the 1980s. The most obvious solution, illustrated in A below, is also what architects call a dormer window, or a vertical window that comes out of a sloping roof—as many of them were delighted to tell me. Two other solutions, B and C, are also possible.

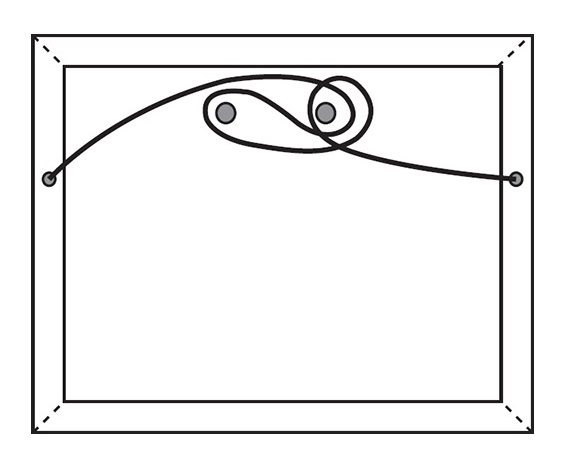

We can solve this using physics (boo!) or math (yay!). The former is predictably less elegant than the latter. Hammer two nails into the wall that are so close together that they will hold a piece of string wedged tightly between them. Then arrange the string like a W with the middle, upward tip of the W between the nails. The painting will hang as the nails will pinch the string in place, and when one of the nails comes off the painting will fall. Ugly, but possibly effective.

Here’s a better solution.

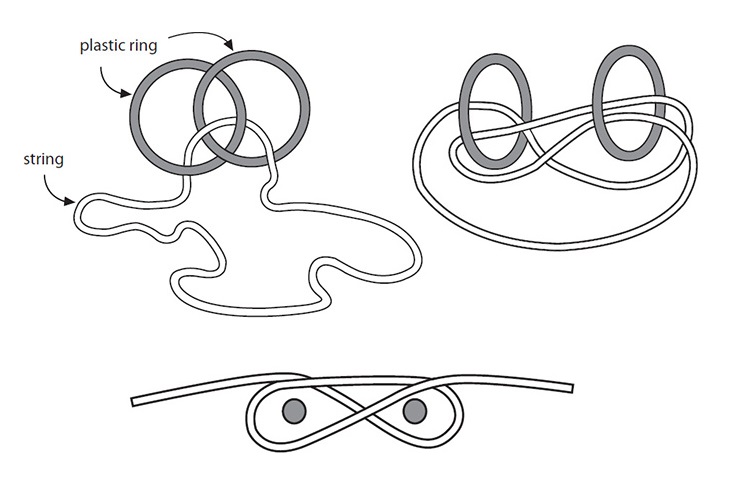

But this isn’t my favorite way to string it up. What I was hoping you would do was to use the Borromean rings to reverse engineer a solution, following my heavy hints that the Borromean rings provide a mathematical model of what we are trying to achieve. When one ring is removed, the other two become unlinked. The puzzle involves three elements—two nails and a piece of string—such that when one is removed they all become disconnected from each other. The hard part is working out just how two nails and a piece of string are equivalent to the Borromean rings, since neither nails nor string look anything like three rings.

Let’s think again about the Borromean rings. They can be circular rings. They can be valknut triangles. They can, in fact, be whatever shape we like so long as the way they interlink is the same. Imagine, for example, that each nail is part of a rigid ring, perhaps one that goes from its tip through the wall, then up and round, back into the room, and then joins the end of the nail again. And imagine that both ends of the string join up, making a giant loop around the room. If these three “rings” are connected in a Borromean way then removing one nail will cause the string to become free from its loop round the other nail, giving us a solution.

So how do we it? I made myself a set of Borromean rings using two plastic rings and a piece of string, shown below left. I then separated the rings side by side (shown below right), as if they were the nails on the wall. The way the string loops between the rings is the solution we are after, which I have put below.

Note that the only section of each “ring” that we are interested in is the bit representing the two nails and the string across the painting, since this is where all the interconnectedness is. The other bits of the “rings”—the extension of the nails that go through the wall or the string that goes around the room—are irrelevant.

Let’s finish off what I started. Since the height of the napkin ring is 6, half the height is 3. So the height of the dome, h, is equal to r – 3, as illustrated in the cross section below.

To find a, the radius of the cylinder that’s removed, we use Pythagoras’s theorem on the right-angled triangle with the dotted line. The square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides, so r2 = a2 + 32, and therefore a =  (r2 – 9).

(r2 – 9).

Now it’s time for the heavy lifting. Using the formulae for napkin volume, which we’ve established is:

sphere – cylinder – 2 × dome

We get:

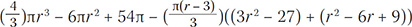

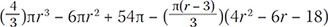

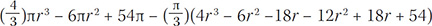

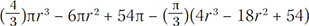

We replace a and h with our new expressions in r:

Multiplying out, we get:

Keep on going . . .

Not long now . . .

Sorry for the slog . . .

Almost there . . .

The terms in r now cancel, leaving:

36π

The answer is stunning. The term r does not appear in the answer, meaning that the size of the sphere is irrelevant to the question!

All napkin rings that are 6cm high have a volume of 36π. A 6cm-high napkin ring made by drilling through a sphere the size of an orange has the same volume as one made by drilling through a sphere the size of a beach ball, or even the Moon.

As you increase the circumference of the ring you make it thinner, and the increase in circumference and the decrease in thickness compensate each other perfectly at all sizes. Mind = blown.

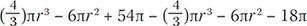

Extend the image by adding the dotted lines. The size of area A plus the area sized 24cm2 is equal to 9cm × 5cm, so A = 45cm2 – 24cm2 = 21cm2. Meanwhile, A + B = 5cm × 8cm = 40cm2. So B = 19cm2.

B has the same width and the same area as the rectangle beneath it marked 19cm2, so it must have the same height, and it must be identical to that rectangle. So A has the same height and width as the rectangle whose area we are looking for, so it must have the same area. The answer is thus 21cm2.

There are many solutions, all along the same lines. The room with the smallest number of walls has six of them, and looks like a three-spiked shuriken, the star-shaped weapon used by Japanese warriors. The square room is more architecturally realistic.