Lü-shi

(Regulated Verse)

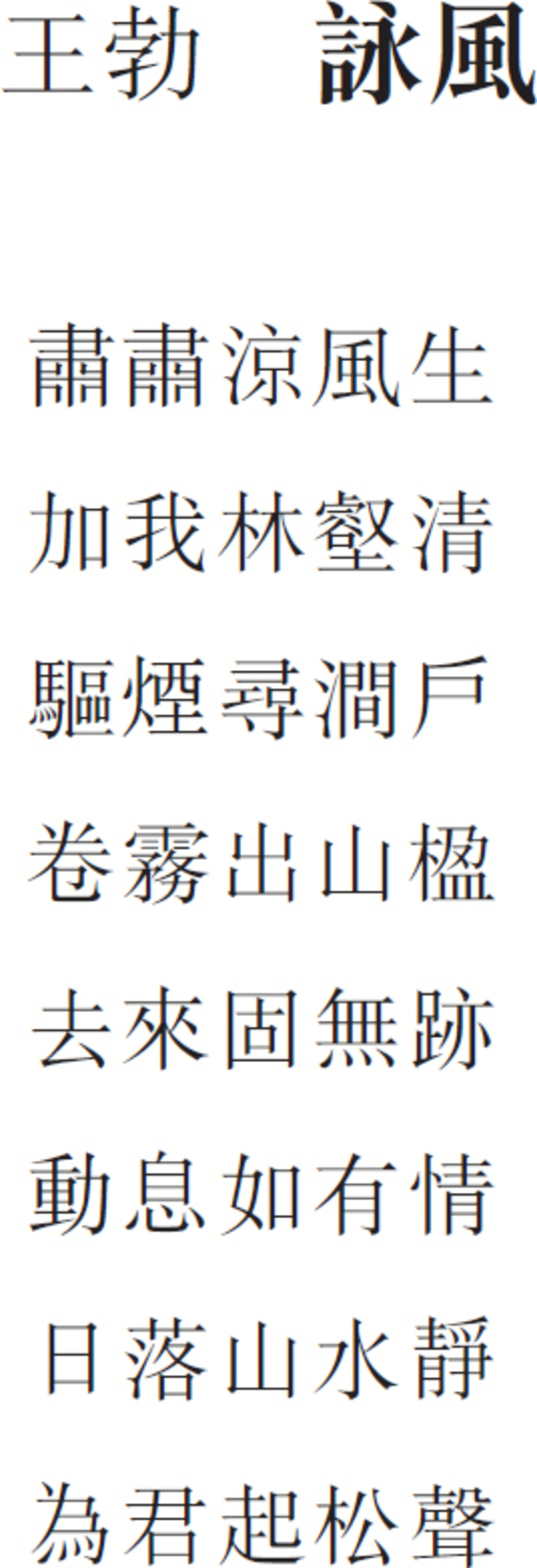

WANG BO

The Wind

In its sigh, cool shadows born,

Clearing my valley, my grove,

Chasing the smoke through the gate of the gorge,

Rolling the mist past the mountain pillars,

Going, or coming, leaving no trace,

Moving, and stopping, as if by design.

Sun falls, the mountain waters quiet.

For you, it makes pines sing.

CUi HAO

Pavilion of the Yellow Crane

The ancients are gone, upon the Yellow Crane.

All that remains: the pavilion bears its name,

And Yellow Crane, once gone, will not return.

White clouds, a thousand years, the empty distance.

Sunlit river clearly seen; trees of Han-yang.

Fragrant grasses burgeon; Isle of the Parrots.

Sun sets, where is my home?

Misty waves upon the river; load me with grief.

This poem was analyzed, as an illustration of the lü-shi form, on this page–this page.

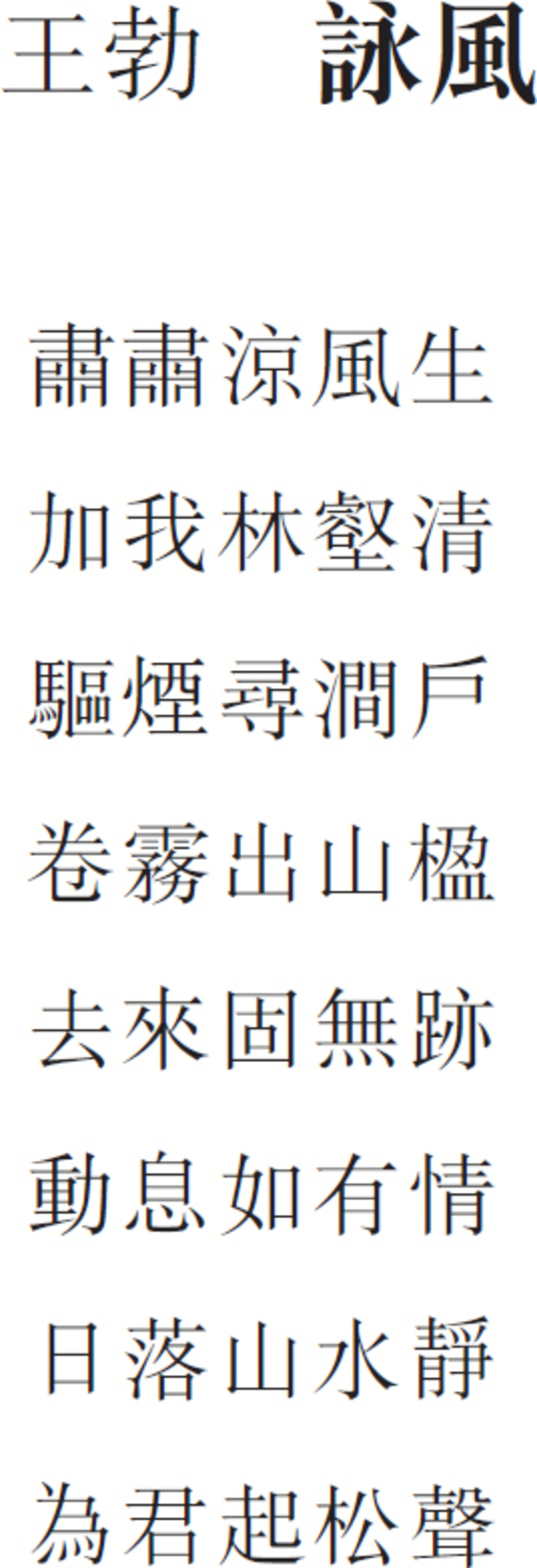

WANG WEI

In Retirement at Zhongnan

To middle age I loved the Way.

Late now, I lodge upon South Mountain.

If feelings rise, I go alone:

Such scenes as I have seen…

Walk to where the waters narrow,

Sit, and wait, for the clouds to rise.

Let me meet by chance with any old man:

We laugh and chat, no thought of the return.

The parallel couplet of lines 5 and 6 provides an excellent illustration of the profound spirit of parallelism. The translation offered here touches only the temporal and linear aspects of the two lines. By referring to the word-for-word translation offered below, the reader may be able to perceive that the coupling of the parallel elements engenders a deeper significance.

Taken in their coupling, the pair “walk-sit” signifies movement and rest; the pair “attain-see,” action and contemplation. The pair “water-cloud” signifies universal transformation, while “narrow-rise” signifies death and rebirth. Finally, the pair “place-moment” signifies space and time. Once the series of significations is taken into account, the two lines may be seen to embody the two fundamental dimensions of all life. And the true way of life is not to choose one or the other exclusively, but rather to embrace the Void between the two, for it is that choice which allows man to sunder neither action and contemplation nor time and space, and thus to participate in the universal transformation.

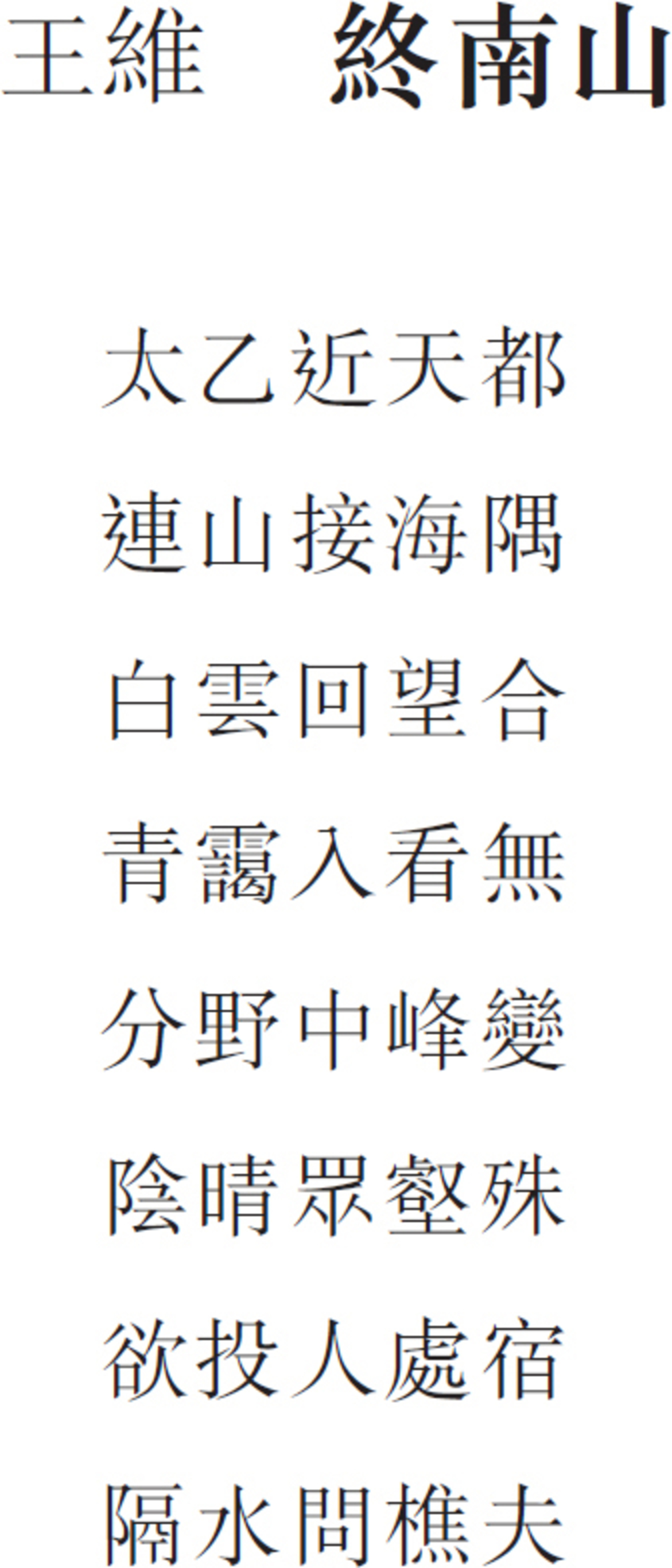

WANG WEI

Mount Zhong-nan

Zhong-nan, The Great One, so near the Celestial City,

Linked mount on mount to the sea.

White clouds, where I look back, close in.

Green mists, when I approach, are gone.

Its peak, the pivot of the constellations’ change;

Its valleys deep, define both light and shade.

I try to find a place to spend the night,

Across the stream, call to the woodcutter.

Lines 1 and 6: Several terms are here used with double meanings. In line 1, Tai-yi (The Great One) is both a notion of Chinese spirituality and an alternate name for Mount Zhong-nan. Tian-du (Celestial City) is the name of a star, but also designates the Tang capital. Mount Zhong-nan is, indeed, located near the capital, Chang-an. In line 6, the expression translated “light and shade” alludes to yin and yang as well as to the sunny (southern) and shady (northern) sides of the mountain.

Lines 3 and 4: concerning the omission of the personal pronoun, see this page–this page. A more “explicit” translation might be: “The white clouds, when one turns back to contemplate them, melt together into a unity; the green rays, to the extent to which one penetrates there, become invisible.” Because of the double meaning of the many terms and the intentional syntactic ambiguity of certain lines, the poem mixes together two orders of being, and celestial (The Great One, the star, yin and yang, etc.) and the terrestrial (Mount Zhong-nan, Chang-an, the sunny and shady sides of the mountain). The reader is presented with the impression that the poem relates, rather than a simple mountain walk of the poet, the visit to the terrestrial world of a divine spirit who descends little by little from the peak into the valley, finally embodying himself to speak with the woodcutter.

WANG WEI

Autumn Mountain Evening

Empty mountain, after new rain,

The air of nightfall, autumn.

A bright moon glows among the pines.

The clear stream flows, upon the rocks.

Bamboo rustles, washing maids come home.

Lotus stirs, as fishing boats return.

Fragrance of spring rests here and there.

You too, my gentle friend, may stay.

On the parallelism of lines 3 and 4, see this page.

Line 8 may also be interpreted “A gentleman can conserve the springtime within himself.”

WANG WEI

Written in Spring in My Country Garden

Above this room, the Spring’s doves coo.

By the village, almond blossoms whiten.

Axes in hand, some go to prune the willows.

Shouldering their hoes, some go to clear the channels.

Returning swallows recognize their last year’s nests.

One who’s dwelt here long leafs this year’s calendar,

Faces the cup, then stays his hand.

Long, warm thoughts of you, far wandering.

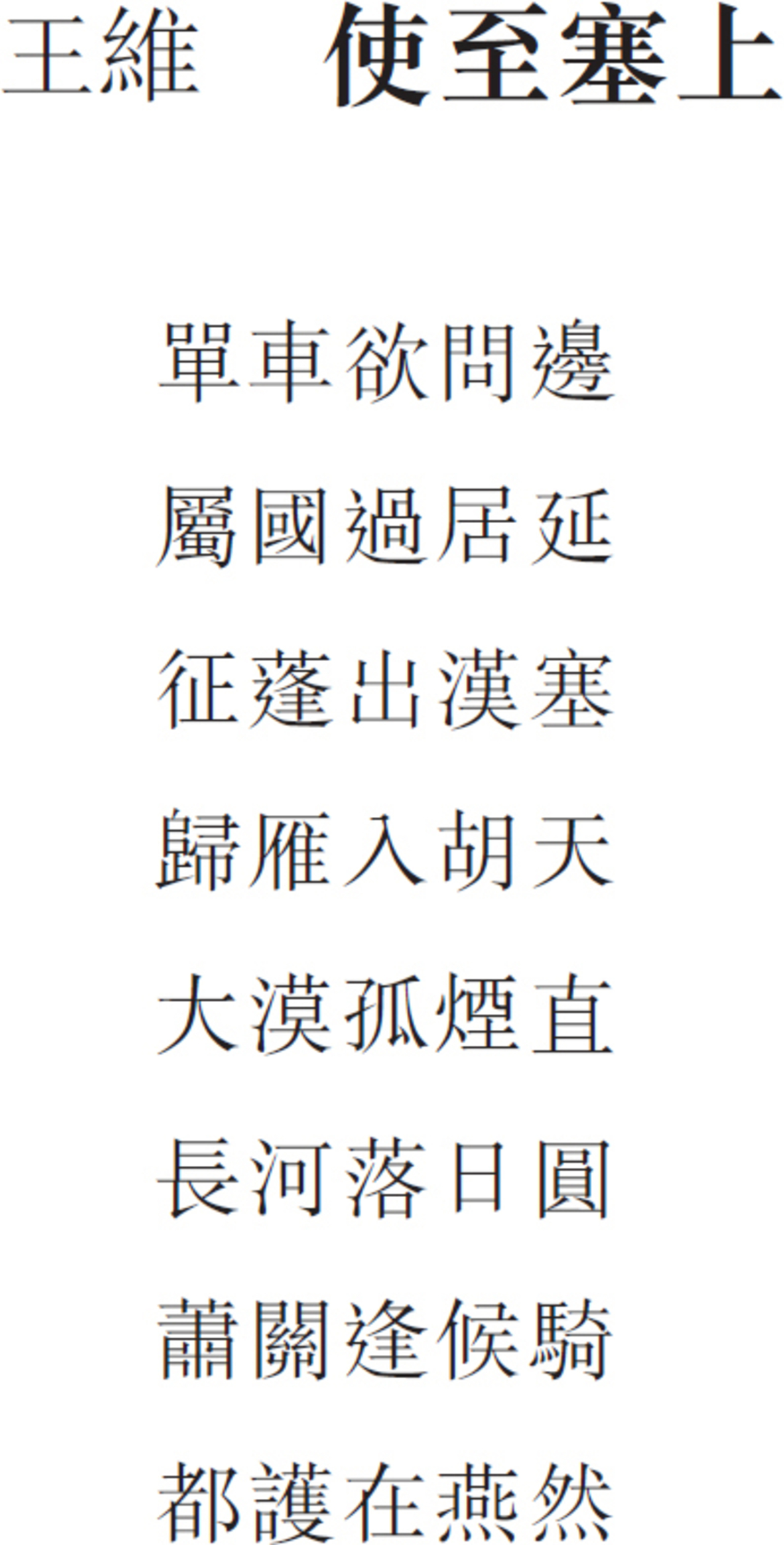

WANG WEI

Mission to the Frontier

A single cart to the frontier

Beyond Ju-yan, past conquered states,

Wandering grass, beyond our borders.

Wild geese, in alien skies.

Vast desert, lone spire of smoke, stands straight.

Long river, the falling sun rolls round.

At Desolation Pass, met a patrol.

Headquarters camp, on Swallow Mountain.

Wang Wei undertook this mission to the frontier in 737.

Line 2: Ju-yan = territory of the Xiong-nu, conquered by the Han.

Line 3: Wandering grass = metaphor that designates a man in exile.

Lines 5 and 6: See this page–this page concerning the parallelism.

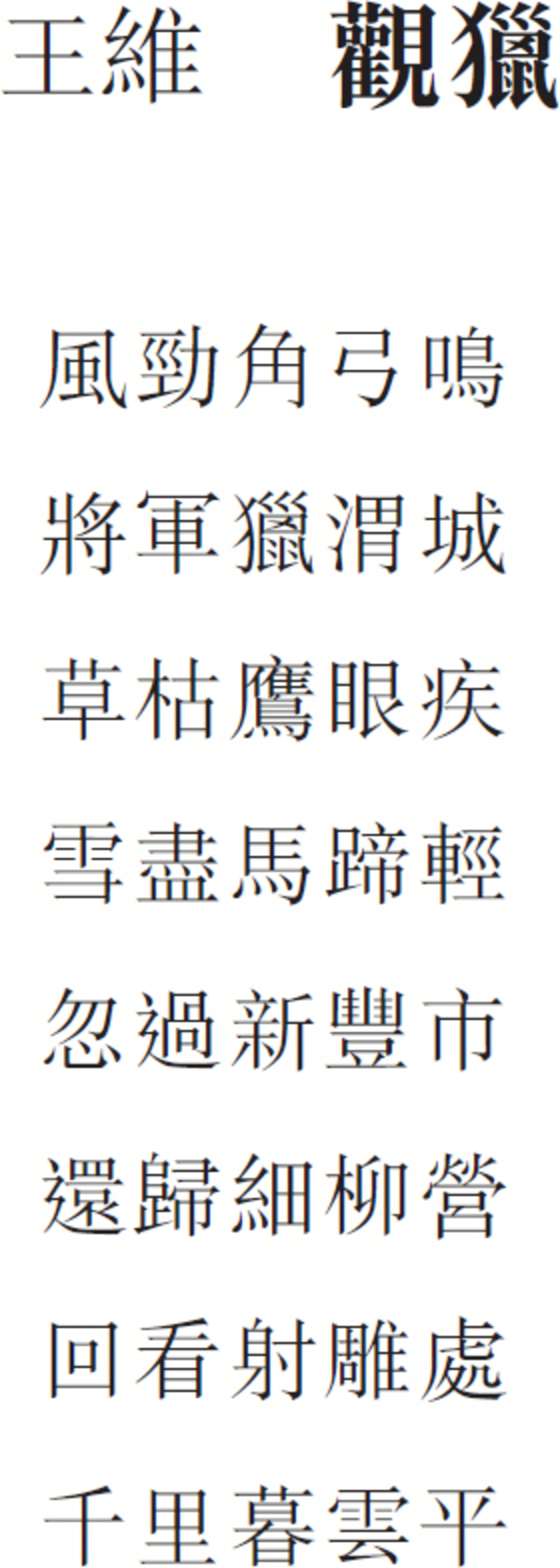

WANG WEI

Watching the Chase

Wind fierce, the horned bows sing.

The generals, in chase at Wei-cheng.

Withered grass, swift eagle eyes.

Snow gone, their steeds step light.

Sudden passed, Abundance Market.

Returning to Five Willow Camp.

Turn and gaze, where the eagle fell:

A thousand li of evening sky stretch on.

WANG WEI

Passing Hidden Fragrance Temple

Who knows the Hidden Fragrance Temple,

How many li away, on cloudy peak?

Ancient trees, no trace of path.

Deep mountain, whence the bell?

Sound of the spring, the standing stones, sobbing.

Color of the sun, the green pines, freezing.

Toward dusk, on the curve of the lake,

Quiet Chan, to tame the poison dragon.

Lines 5 and 6: In the original, these lines are, by their syntactic structure, ambiguous. Is it the spring that sobs, or the rocks? Is it the sunlight that freezes, or the pines? The interpretive translation attempts to maintain the feeling of reciprocity (and of correspondence).

Line 8: Chan (Zen in Japanese) is the Chinese transcription of the Buddhist term dhyana which means meditation-concentration. It is, as well, the name of a school of Chinese Buddhism. The poison dragon represents inappropriate passions.

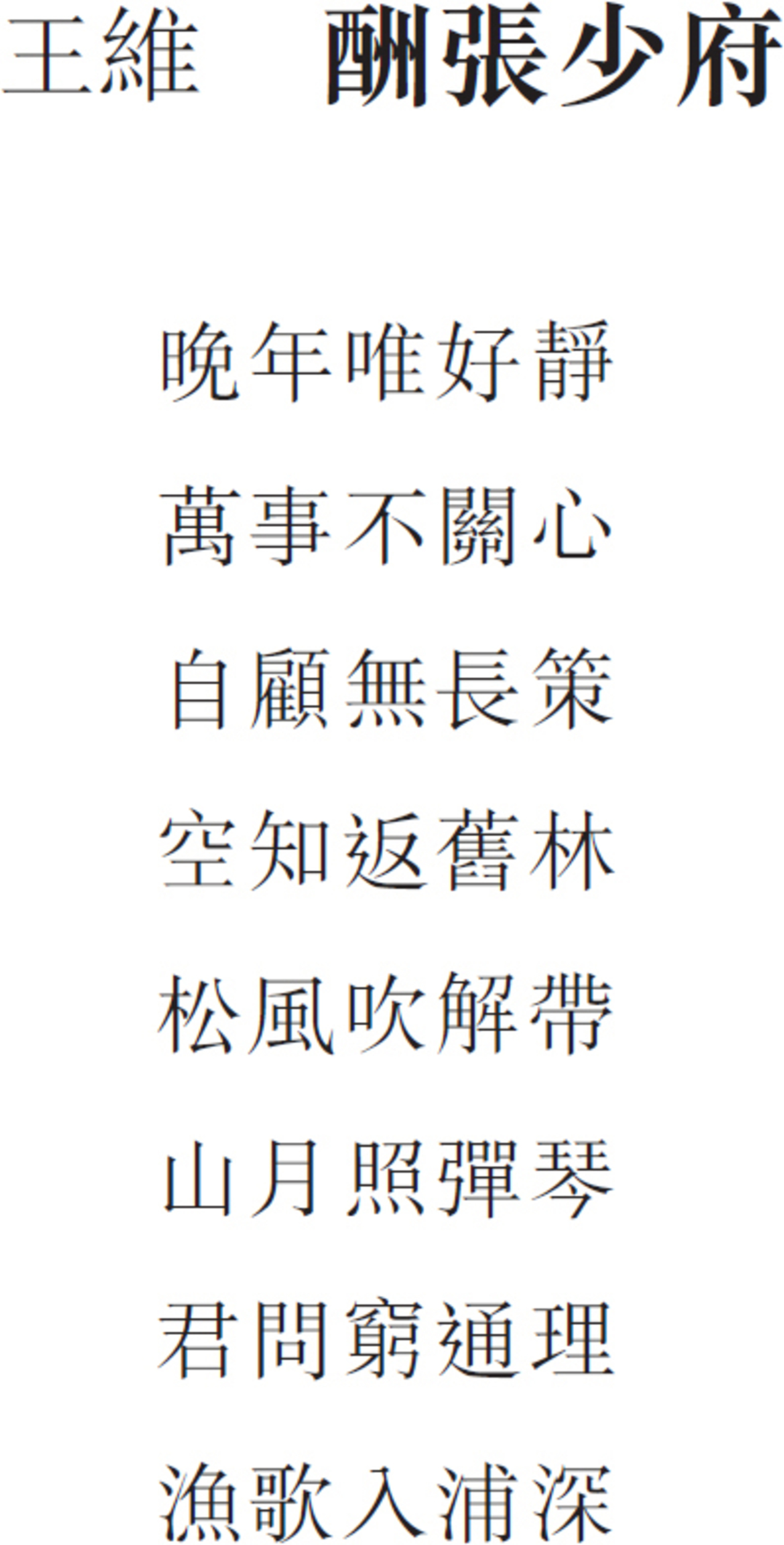

WANG WEI

To Magistrate Zhang

Late, I love but quietness:

Things of this world are no more my concern.

Looking back, I’ve known no better plan

Than this: returning to the grove.

Pine breezes: loosen my robe.

Mountain moon beams: play my lute.

What, you ask, is Final Truth?

The fisherman’s song, strikes deep into the bank.

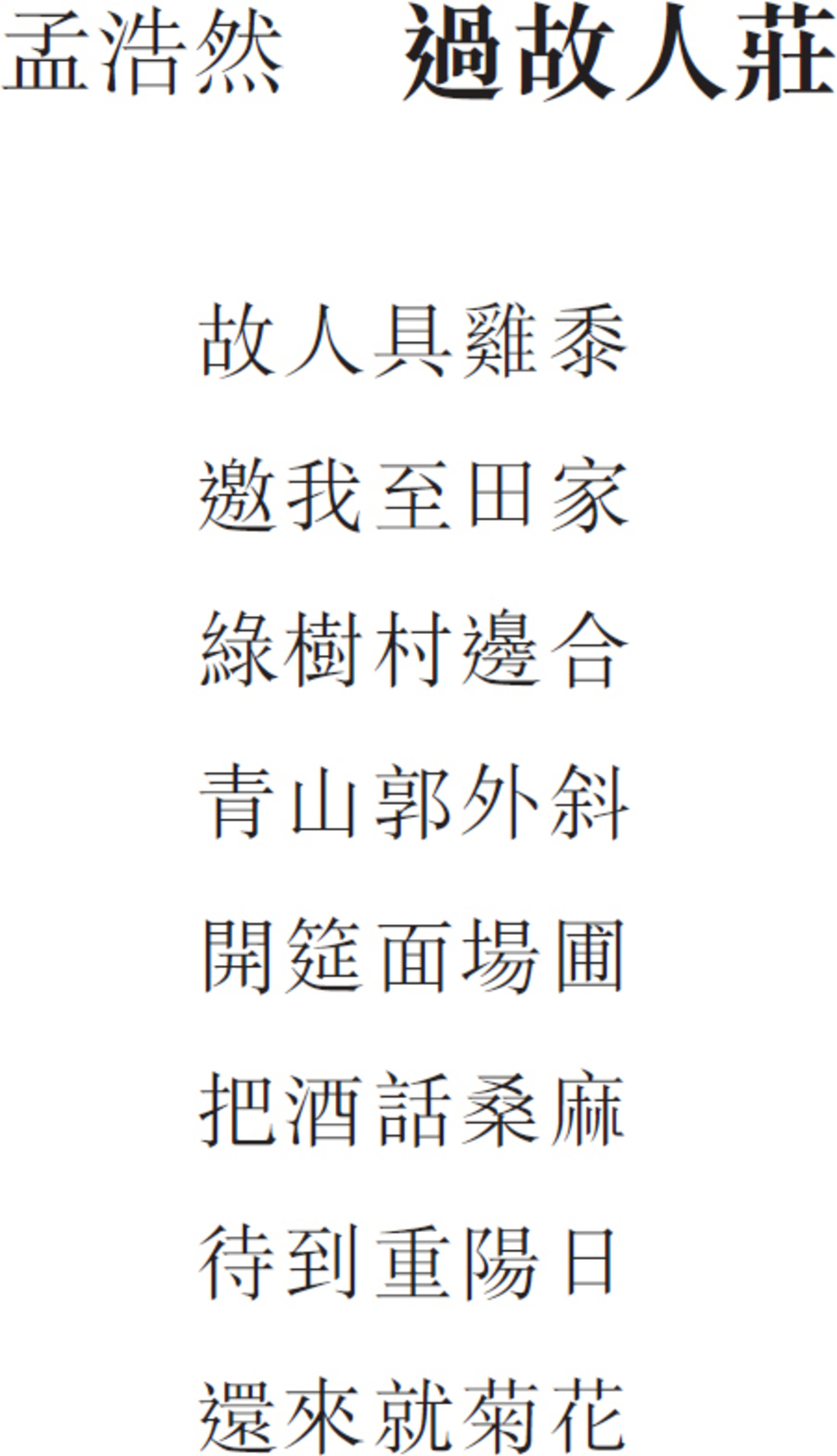

MENG HAO-RAN

Master Yi’s Chamber in the Da-yu Temple

Yi Gong’s place to practice Chan:

A hut, in empty grove.

Outside the door, a single pretty peak.

Before the stair, deep valleys.

Sunset confused in footprints of the rain.

Blue of the void in the shade of the court.

Look, and see: the lotus blossom’s purity.

Know, then, that nothing taints this heart.

MENG HAO-RAN

At an Old Friend’s

Old friend prepared me fowl and millet,

Invited me to his country home.

Green trees fence in the village.

Blue hills incline, beyond that wall.

Supped there beside the kitchen garden

Sipped wine, and spoke of mulberry, and hemp.

Just wait, until the Double Ninth,

I’ll come again, for the chrysanthemums.

Line 6: “Talked of mulberry and hemp” is a conventional expression for friendly and carefree talk between country gentlemen (much as we say we “talked about the weather”).

Line 7: Double Ninth = Autumn festival that is held on the ninth day of the ninth (lunar) month. Traditionally, the celebrants climb the heights to better participate in the fullness of nature.

LI BAI

Searching for Master Yong

So many cliffs, jade blue to scour the sky,

I’ve rambled, years uncounted,

Brushed aside the clouds, and sought the Ancient Way,

Or leaned against a tree and listened to streams flow.

Sunwarmed blossoms: the blue ox sleeps.

Tall pines: the white cranes resting.

Words came, with the river sunset.

Alone, I came down, through the cold mist.

LI BAI

Seeing off a Friend

Green mountains border Northern Rampart.

Clear water curls by Eastern Wall.

Here, we’ll make our parting.

There, lonely brambles stretch ten thousand li.

Floating clouds: the traveler’s thoughts.

Falling sun: the old friend’s feelings.

Touch hands, and now you go,

Muffled sighs, and the post horse, neighing.

For the comparison in lines 5 and 6, see this page.

DU FU

In Contemplation of Mount Tai

Mountain of Mountains it’s called. Why so?

The green of Qi and Lu is lost to view.

Here Creation crystalizes grace.

With north and southern slopes defining dusk and dawn.

Chest straining, where thick clouds grow.

Eyes bursting to see returning birds.

Shall I, one day, attain that final summit?

All other mountains, at a glance, grown small?

Mount Tai, which divides Shan-dong province into two parts, Qi and Lu, is the most famous of the five sacred mountains of China. It has another name, Dai-zong, which can be translated “Ancestor of Mountains.”

Line 1: The poet uses a direct colloquial tone to express his feelings upon finally finding himself before the famous mountain.

Lines 5 and 6: Our translation attempts to conserve the ambiguity of the original lines. In the absence of the personal pronoun it is possible to ask whether the “straining chest” and the “bursting eyes” are those of the poet, or of the mountain personified. In reality the poet is trying to express precisely the identification of the climber with the mountain, and to give a vision of the mountain within.

The last two lines refer to the phrase in Mencius, “When Confucius reached the summit of Mount Tai, the Universe appeared suddenly small.”

This poem, which is traditionally classed as a gu-ti-shi, was written in 736, when the poet was twenty-four.

DU FU

Captive Spring

The nation is sundered; the mountains, the rivers, remain.

The city’s spring; trees and grasses, deep.

Touched by times passing; flowers drip tears.

Pained at this separation: birds jar the heart.

Beacons of war burn now into the third month.

One note from home: I’d give a thousand gold.

White hair, scratched even thinner,

No enough left for a hairpin.

This poem was composed by Du Fu in the spring of 757, while he was being held captive in the capital, Chang-an, by the rebels of An Lu-shan.

Lines 3 and 4: Owing to their extreme concision, these lines are open to multiple interpretations. The “normal” translation would be “Regretting the time that passes, I let my tears fall upon the flowers (which I contemplate); and, suffering from separation, my heart starts when I see the birds flying free.” But, as they are read word for word, the lines may also suggest that the flowers themselves participate in the human drama, dripping tears, and the birds fly up in fright at the same circumstances that ravage the poet. The image of the hairpin (signifying evanescent youth) that ends the poem contrasts ironically with that of the luxuriant nature with which the poem begins.

See this page–this page for a discussion of the function of the caesura.

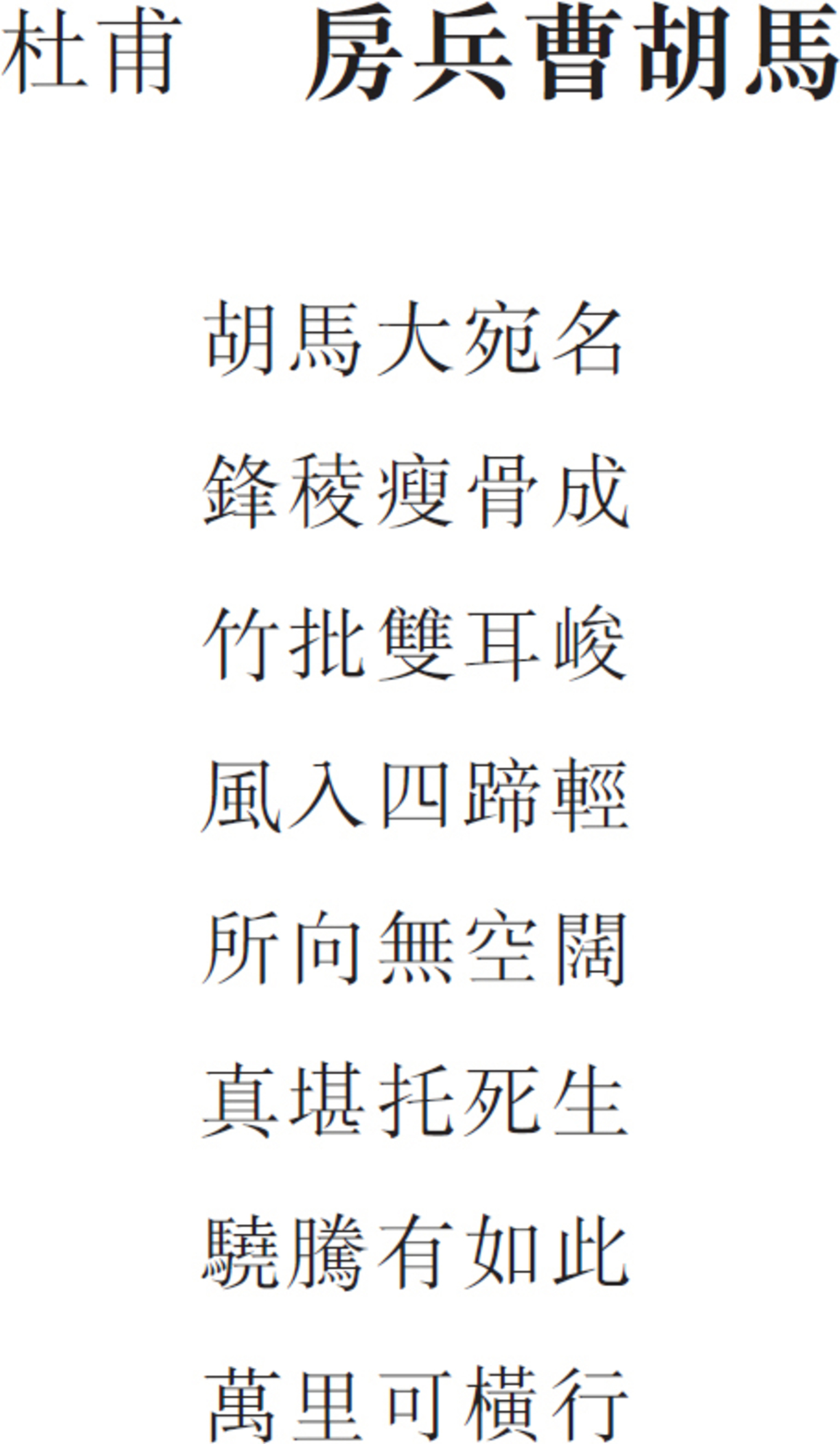

DU FU

The Barbarian Horse of Officer Fang

Barbarian horse, the famed of Fergana,

Sharp angles, lean-boned lines.

Bamboo spikes, the two ears spire.

To pierce the wind, these four feet light.

Across that vast, that endless space,

You may trust it with your life.

Such a steed! With one like this

Ten thousand li’s just a canter.

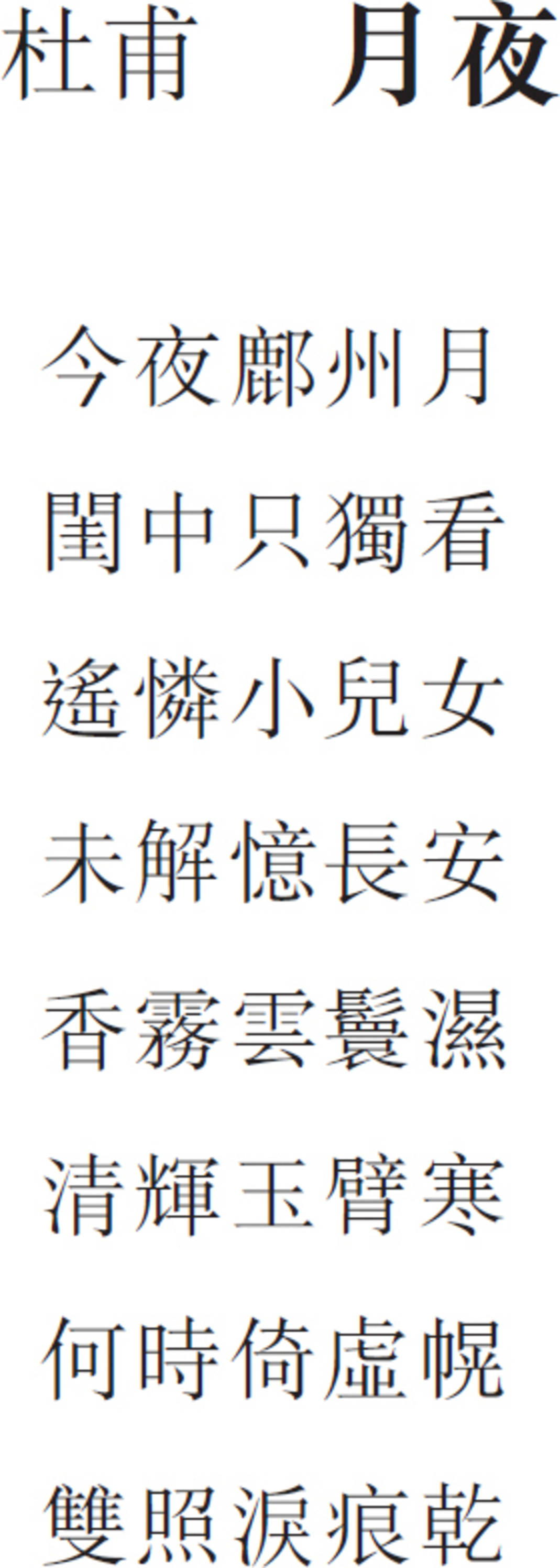

DU FU

Moonlight Night

Moon of this night, in Fu-zhou.

Alone in your chamber you gaze.

Here, far away, I think of the children,

Too young to remember Longpeace…

Fragrant mist, moist cloud of your hair.

In that clear light, your arm jade cool.

When may we lean by your empty curtain,

Alight alike, until our tears have dried.

The poet, captive in Chang-an, addresses this poem to his wife, who was with their children in Fu-zhou, in Shen-xi, outside the area held by the rebels.

Line 4: the name of the Tang capital, Chang-an, means “long peace.” The line has a double meaning: “The children are too young to remember having been in Chang-an” and “the children, growing up in wartime, don’t know what peace is.”

Lines 5 and 6: see this page–this page with regard to the metaphors.

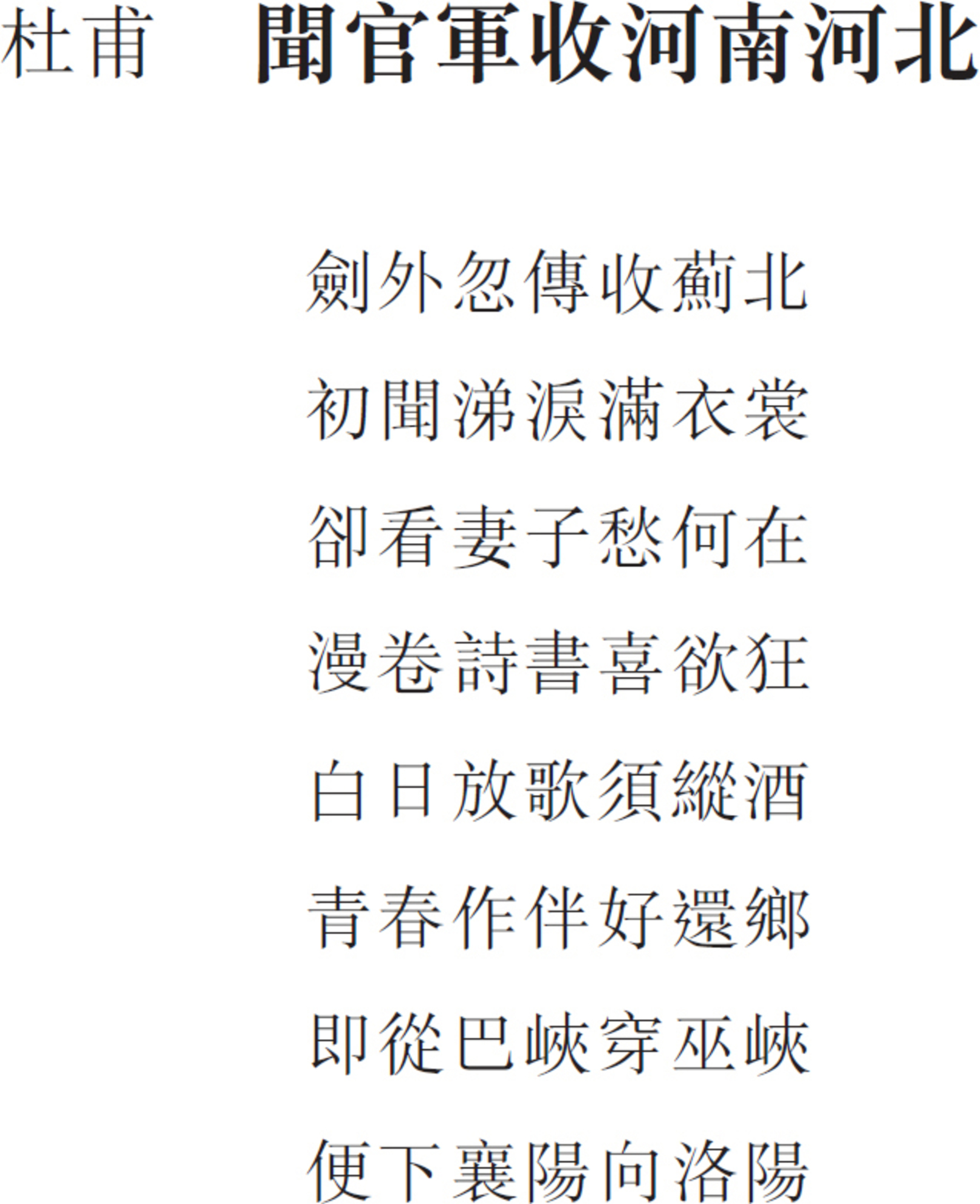

DU FU

On Hearing that the Imperial Army Has Retaken He-nan and He-bei

From Swordgate the news: Ji-bei is retaken!

When first I heard, tears wet my gown.

Then I gazed on wife and children, all grief gone.

Wild, I rolled up all my scrolls; a joy like madness.

Into bright day set free a song, and drank all unrestrained.

Green spring beside me, so good to go home!

Now, to sail through Ba Gorge, to the gorges of Wu,

Downriver past Xiang-yang, and finally, to Luo-yang.

In 763, Du Fu was in Si-chuan not far from Jian-ge (Swordgate) when he heard that the central and northeastern provinces had been recovered by government troops, ending the An Lu-shan Rebellion, which had begun eight years earlier.

Lines 7 and 8: contrary to the rule of the lü-shi that states that the last couplet may not be parallel, this one is distinctly so, as if the poet sought to prolong the euphoric state described in the preceding parallel couplets. Note also the phonic contrast of the two lines: in line 7, the series of “tense” consonant sounds—ji, xia, xia—which reinforce the idea of an oppressive state, and in line 8 the series of -ang finals, which in the Chinese poetic tradition suggest exultation and deliverance. See this page–this page and this page.

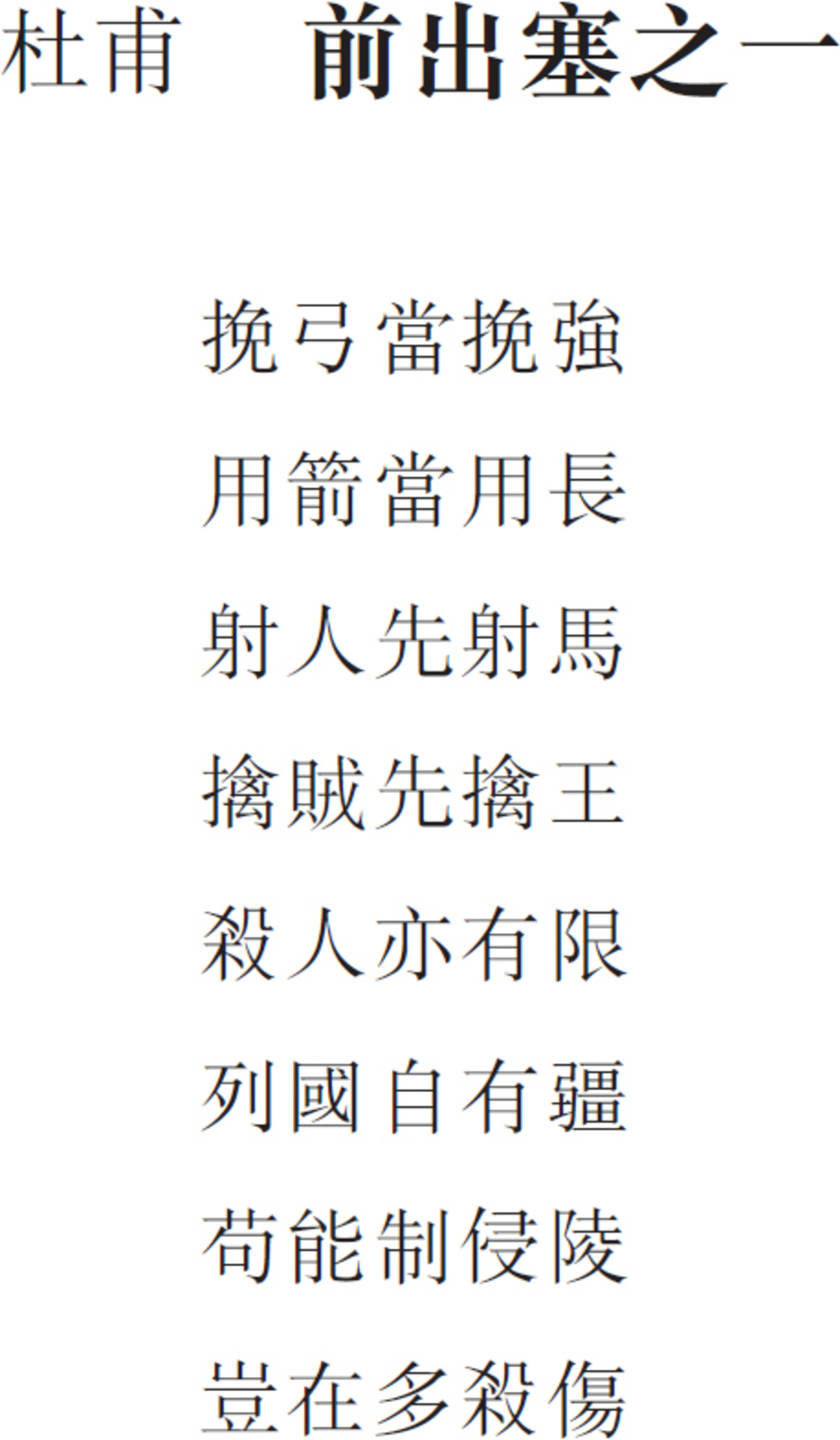

DU FU

Ballad of the Frontier

If you draw the bow, draw the strongest.

Choosing arrows, take the longest.

To down the man, aim for the horse.

Taking bandits, aim for the chief.

Killing, let there be a limit,

And each land its own bounds.

If you can repel invaders,

What use, in killing, maiming more?

In the original, there is a strong percussive accent in the first strophe (lines 1–4) created by the alternating play of the same initials and finals (Wan gong dang wan qiang / Yong jian dang yong chang / She ren xian she ma / Qin zei xian qin wang).

Though very close in form, this poem is not, technically speaking, actually a lü-shi.

DU FU

Bai-di

At Bai-di clouds leap from the gates.

Below Bai-di, it rains, as from an upturned tub.

High water, narrow gorge, lightning and thunder battle.

Green trees, gray vines, sun and moon, dusk.

War horses, not so quiet as a horse returning home.

A thousand families once, now just a hundred left.

Sad sad widow, taxed and labored out,

Grieving, crying for what village on that autumn plain?

Bai-di (White Emperor): this high-perched city dominates the gorges of the Yang-tze.

DU FU

To My Guest

South of the hut, north of the hut, everywhere, spring floods.

Only the gulls come every day.

No guests; the flower path’s unswept

But the bramble gate is open, now, for you.

A simple dish; the market’s far, no special treats.

A single jug; the home is poor, just old-time brew.

Will you drink, together with my good old neighbor?

I’ll call him through the hedge, to help us drain these cups.

This poem, like the following one, was probably written around 761 at Cheng-du in Si-chuan, where Du Fu built his famous “thatched hut.” This was perhaps the happiest and most peaceful period of his life. “Old-time brew” alludes to a wine made by an ancient and very rudimentary method.

DU FU

Village by the River

Clear stream, meanders by the village, flowing.

Long summer days, at River Village, everything at ease.

Coming, going, as they please, a pair of soaring swallows.

There, paired and close, out on the water, gulls.

My old wife draws a board for chess.

My son bends pins for fishhooks.

I’m often sick, but I can find good herbs.

What, beyond this, could a simple man ask?

DU FU

Good Rain: A Night in Spring

The good rain knows its season.

Come spring, it comes to life again.

With the wind, so stealthy in the night

Moistens all things, so delicate, so silent.

On the wild paths, clouds all black.

From river skiff, a lamp, the single light.

In morning’s glow, the red wet spots;

Flowers weigh down upon the Brocade Mandarin.

This poem too was composed at Cheng-du, when, aboard a boat on the river near the town, he witnessed the arrival of a timely spring rain. The following day he contemplated, enraptured, the scene after the rain: the city covered with red flowers gorged with rain. In the last line the poet cleverly chooses an alternate appellation for Cheng-du, styling it Jin-guan cheng, City of the Brocade Official, to suggest that he also, exiled literatus, shares the joy of participating in the festivities of spring. For a discussion of the rhetorical use of proper names in Chinese poetry, see this page–this page.

DU FU

Second Letter to My Nephew Wu-lang

In front of the hut, she scavenges for dates: let her be.

Hungry, childless, the lone woman,

Only the deepest poverty could bring her to this.

Her fear, her shame, call the more for kindness.

True, she has no reason to distrust her new neighbor.

Yet even a sparse hedge would seem a wall to her.

To think of the taxes: poor to the bone.

And the horses of war: tears wet my sleeve.

See this page–this page on the omission of personal pronouns.

DU FU

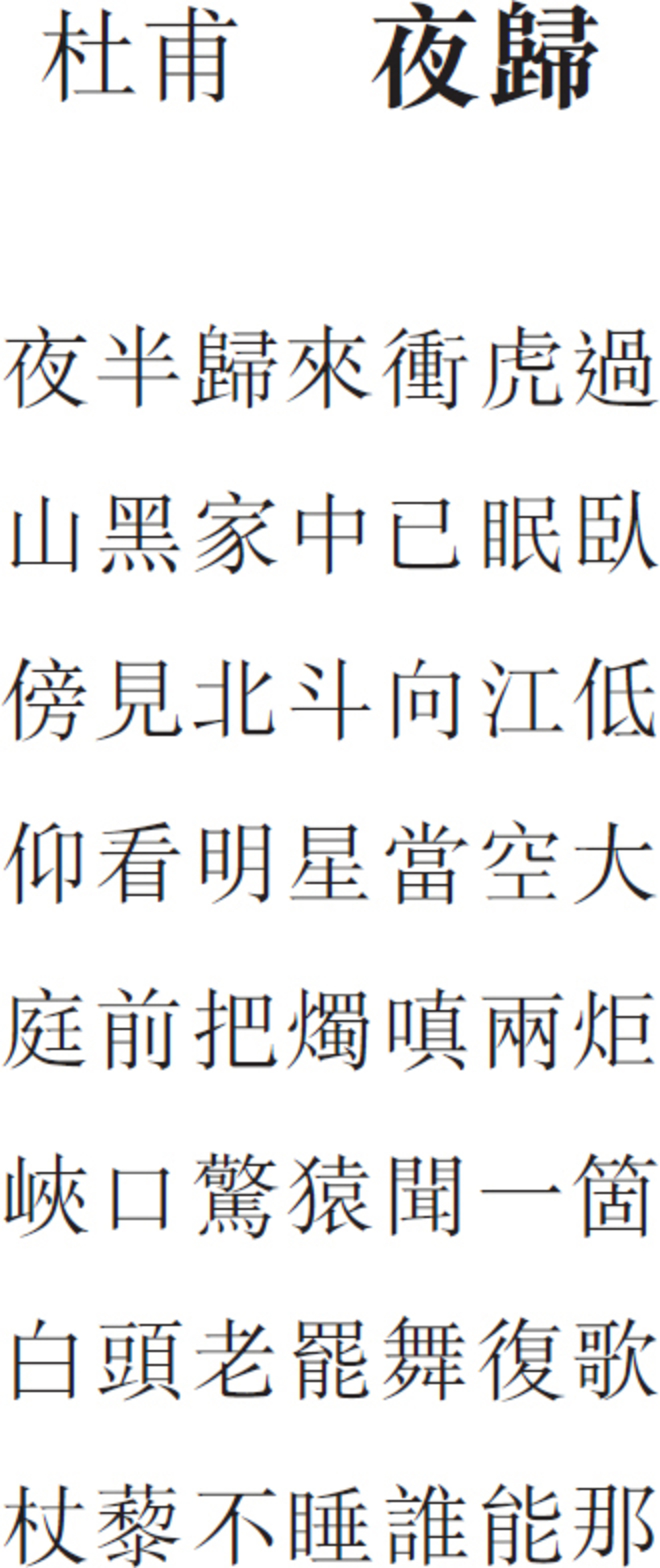

Coming Home Late at Night

At midnight, coming home, I passed a tiger.

The mountain’s black, inside they’re all asleep.

Far off the Dipper lowers toward the River.

Above, Bright Star grows great upon the sky.

With candle in the court I glower at two flames.

The apes are restive in the gorge, I hear one cry.

White head, old no more, I dance, and sing.

Lean on my cane, unsleeping. And what else!

Lines 3 and 4 emphasize the greatness of the universe in contrast to the fragility of human life.

Lines 5 and 6 describe the fear which continues to grip the poet. The two flames recall the tiger’s eyes; and the cry of the monkey still startles him.

The phrase shei neng na, which ends the poem, is a spoken expression with a nuance of careless defiance. The poet uses it here to express his irrepressible and childlike joy at having escaped from mortal danger.

For an analysis of this poem—as an illustration of from the lü-shi from—see this page–this page. We have made no attempt to translate this poem.

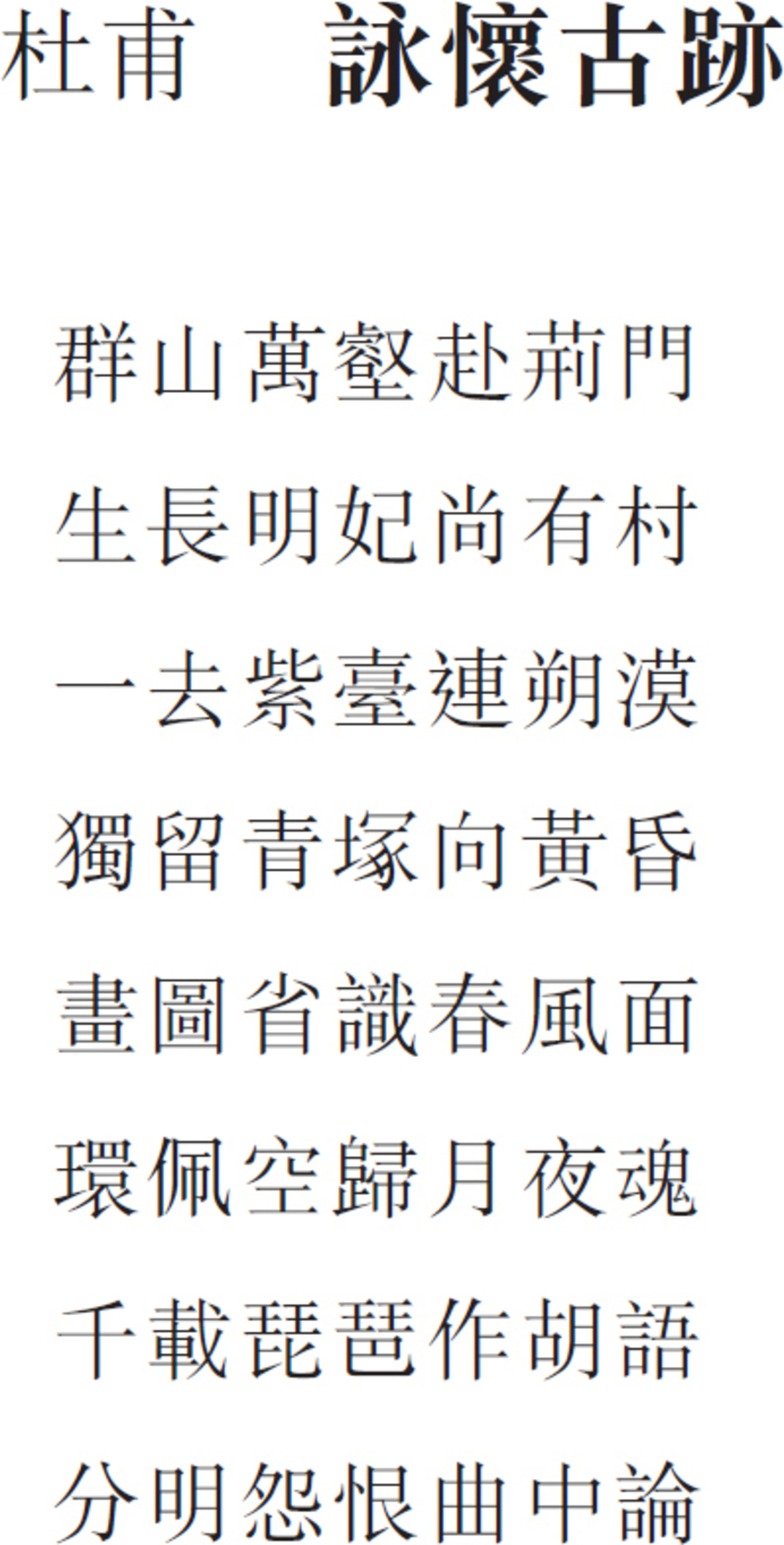

DU FU

Poem for Zuo on His Return to the Mountains

White dew, the yellow millet ripe.

The sharing of an ancient promise.

It must already be ground fine.

It seems a little late arriving.

The flavor’s not quite up to “golden aster.”

It’s tasty, nonetheless, with green mallow.

Old time old man’s food…

Just the thought, and my mouth waters.

This poem was addressed to one of the poet’s cousins who had promised to send him some millet. Du Fu suffered hunger during numerous periods of his life (one of his sons died of starvation). During the flight from the rebels, the family ate wild plants and gleanings in order to survive. Toward the end of his life, notably in Si-chuan, he wrote many poems in praise of the fruits of the earth: shallots dripping dew, melons cool as crystals, fish baked in pine needles, etc.

DU FU

Jiang and Han

On Jiang and Han, thinking of home,

Between heaven and earth, one worn-out scholar.

A single cloud, ever farther in the sky.

Long night, more lonely with the moon.

Sun falls, this heart still rises.

In the winds of autumn, my illness nearly gone.

In ancient times they kept old horses:

There are other tasks than the long haul.

Jiang and Han: names of two rivers.

Lines 3 and 4: see this page–this page on “empty words.”

Lines 7 and 8: despite age and failing health, the poet does not despair of making himself useful to the government again.

DU FU

Thoughts of a Night on Board

Slender grasses, a light breeze on the banks.

Tall mast, a solitary night on board.

A falling star, and the vast plain broader.

Surging moon, on the Great River flows.

Can fame grow from the written word alone?

The official, old and sick, must let it be.

Afloat, afloat, just so…

Heaven, and Earth, and one black gull.

This poem was written by Du Fu in the later years of his life, probably in 767, when he was traveling in the upper reaches of the Yangtze, leaving from Kui-zhou in Si-chuan downstream toward Jiang-ling. In the course of this journey he died, alone on the boat. The images of the stars and the moon in lines 3 and 4 do of course represent these outstanding elements of the cosmos; however, they also symbolize the manifestation of the human spirit, since in China immortal works are often compared to the sun, the moon, and the stars. For these two lines, see this page–this page on the omission of the preposition. Despite the doubt and bitterness expressed in lines 5 and 6, Du Fu is confident of the power of poetry. In another poem, he states this confidence quite forcefully:

When I sing, I know it, gods and spirits draw near.

What do I care if I starve and end in the gutter?

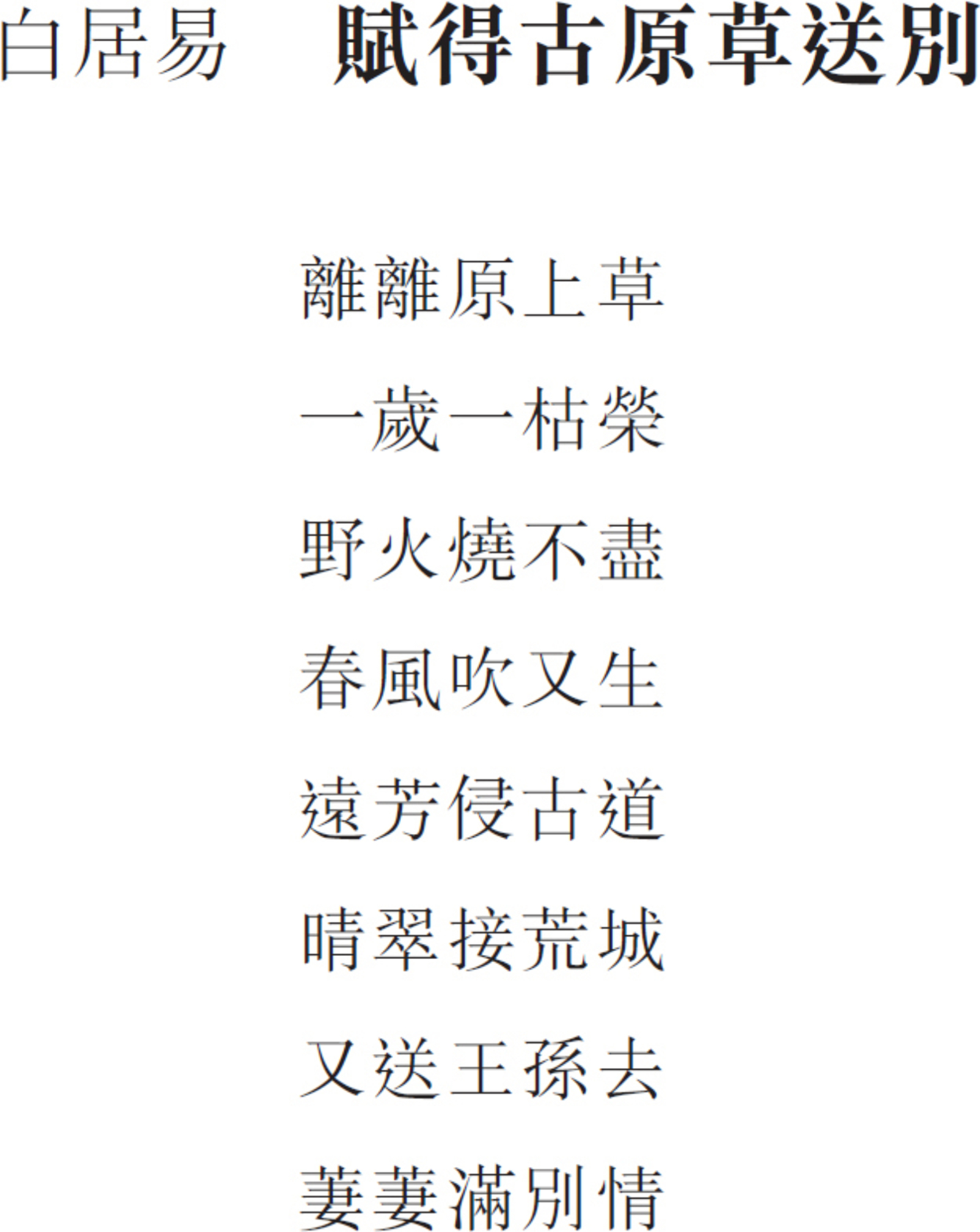

BAI JU-YI

Grass on the Ancient Plain

So tender, so tender, the grasses on the plain.

In one year, to wither, to flourish.

Wild fire cannot bum them all away.

Spring breezes’ breath, they spring again.

Their distant fragrance on the ancient way,

Their sunlit emerald greens the ruined walls.

Seeing you off again, dear friend.

Sighing, sighing, full of parting’s pain.

For an analysis of this poem, in regard to symbolic images, see this page–this page. We have made no attempt to translate this poem.

It would be interesting to do a parallel reading of this poem with Nerval’s “El Desdichado.”

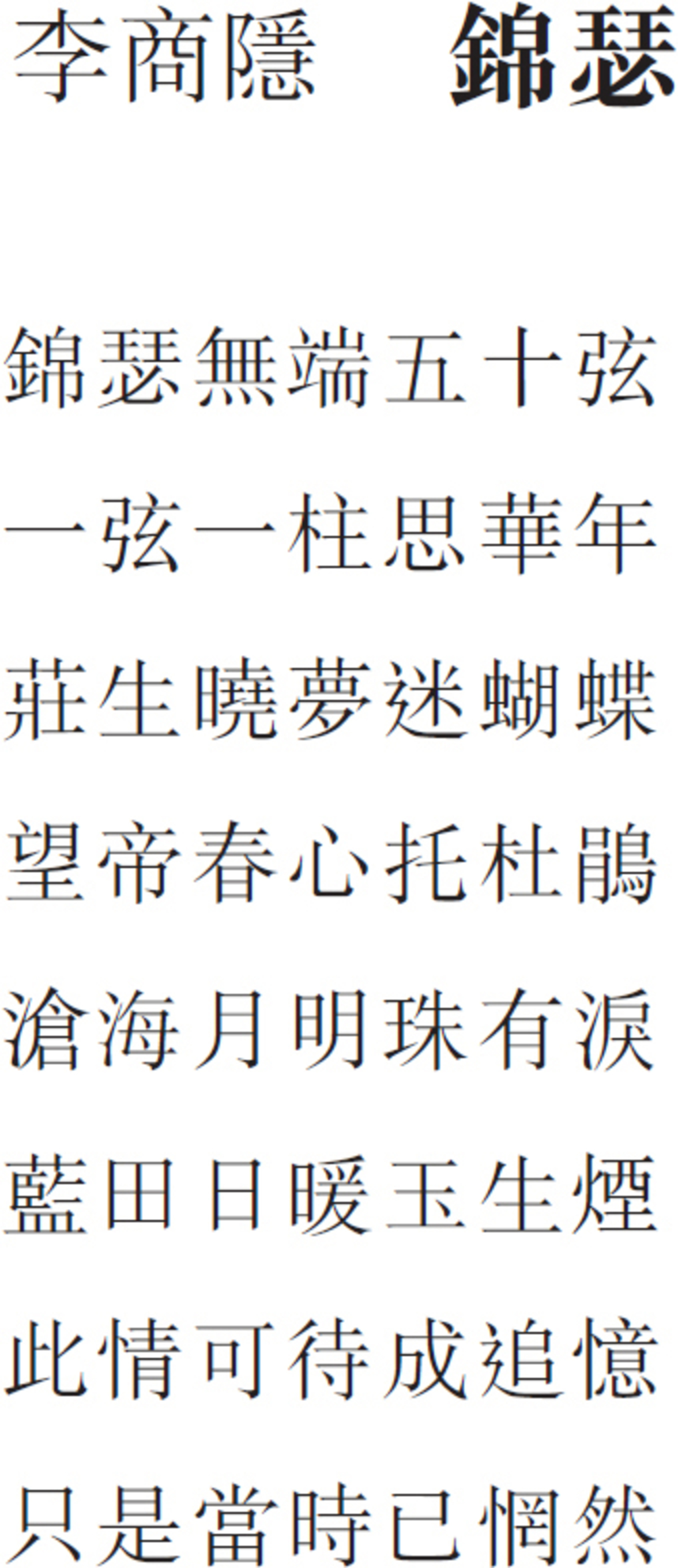

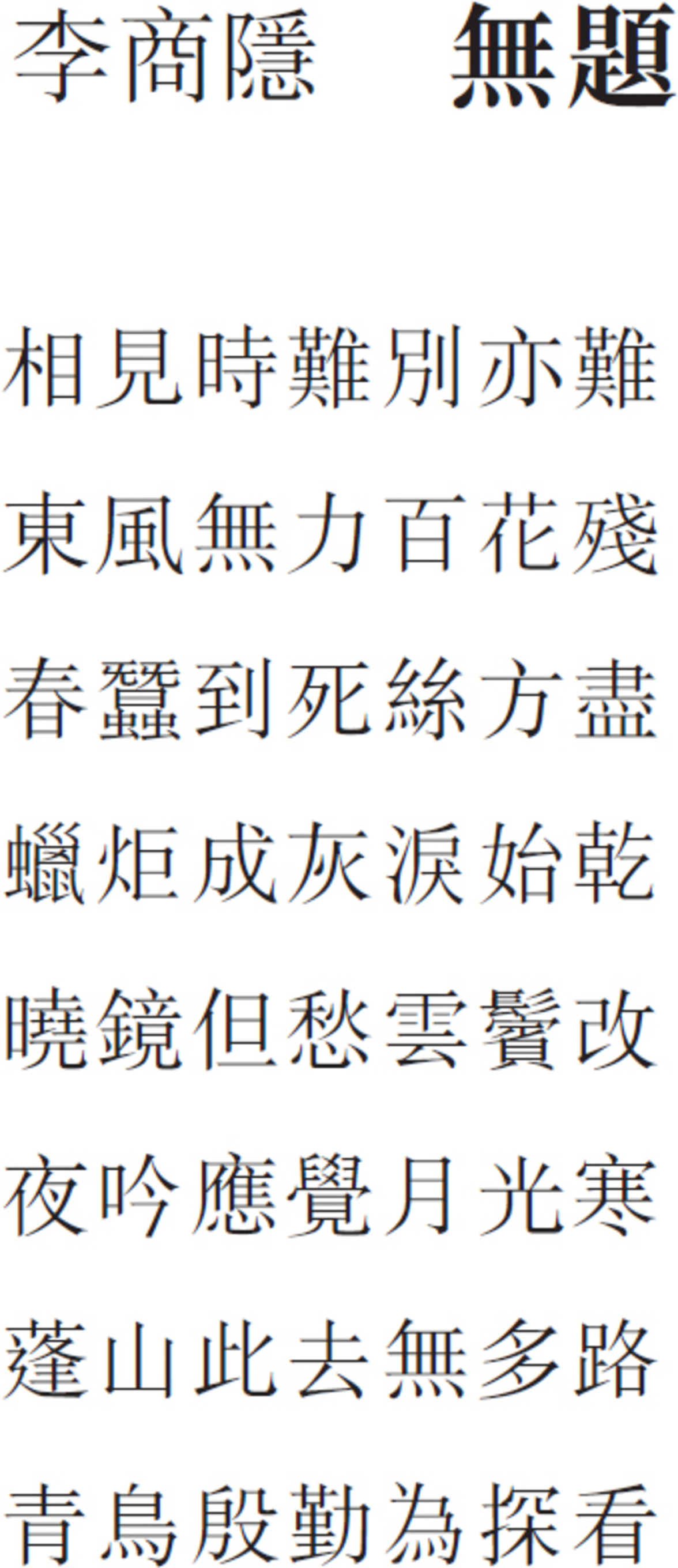

LI SHANG-YIN

Untitled

Meeting is hard, parting, hard too.

The east wind’s feeble, the hundred flowers fall.

Spring silkworm spins its silk until it dies.

The candle sheds its tears till wick is ashes.

Mirror of morning grieves, clouds of hair are changing.

Song of the night, know moonlight’s cold.

From here to Mount Peng the way’s not long

But the Green Bird is attentive, watches close.

Line 7: Mount Peng = The Immortal Mountain; legendary mountain on the Peng-lai Isles, in the Eastern Sea.

Line 8: the Green Bird = messenger of Xi Wang-mu (Queen Mother of the West, daughter of the Heavenly Lord and sovereign of the places where the sun sets).

Li Shang-yin here sings in a very allusive tone of a secret love affair (with a lady of the court or a Taoist nun). With the exception of the highly colloquial first line, which reveals the theme of the poem, love and the drama of separation, the poem is constructed of a network of images and metaphors often connected by phonic links. In line 3, “silkworm” (can) is a homonym of the expression “love-spasms” (can-mian), just as “silk thread” (si) is the homonym of the word amorous thoughts” (si). In addition, “silk threads” enters into the expression “green threads” (qing-si), which means “black hair,” from which stems the image of the hair in line 5. In line 4, “ashes” (hui) enters into the expression “broken heart” (xin-hui), which thus continues the idea of a thwarted love contained in the preceding lines; in addition here, hui (ashes) also means the color gray, from which arises the image of the changing hair color in line 5. Also in line 4, the image of the candle flame reflects back to that of the east wind in line 2, and forward to that of the moonlight in line 6. The image of the moon evokes the figure of the goddess Chang-E, who dwells there alone (having been exiled there by Xi Wang-mu). She suggests both the distant lover and the possibility of the consummation of the love, in a place happily beyond time.

In this way, the images and metaphors are provided with the necessary links to allow them to transform the poem into a drama. The lines are not to be read as a description, but to be experienced as the acts of the play. Line 2, through the images of the east wind and the flowers, alludes to an unrequited love, but also to the sexual act. Lines 3 and 4, through their parallelism, continue the idea of a sexual bond (cocoon and candle), even though the apparent theme is the oath of fidelity. Lines 5 and 6 describe the separation but subtly insert the destiny of the lovers into that of nature, a nature gradually transfigured. It is only this transformation that allows the escape into dream. Passing through a series of steps across the test of time, the poem opens upon the infinite.

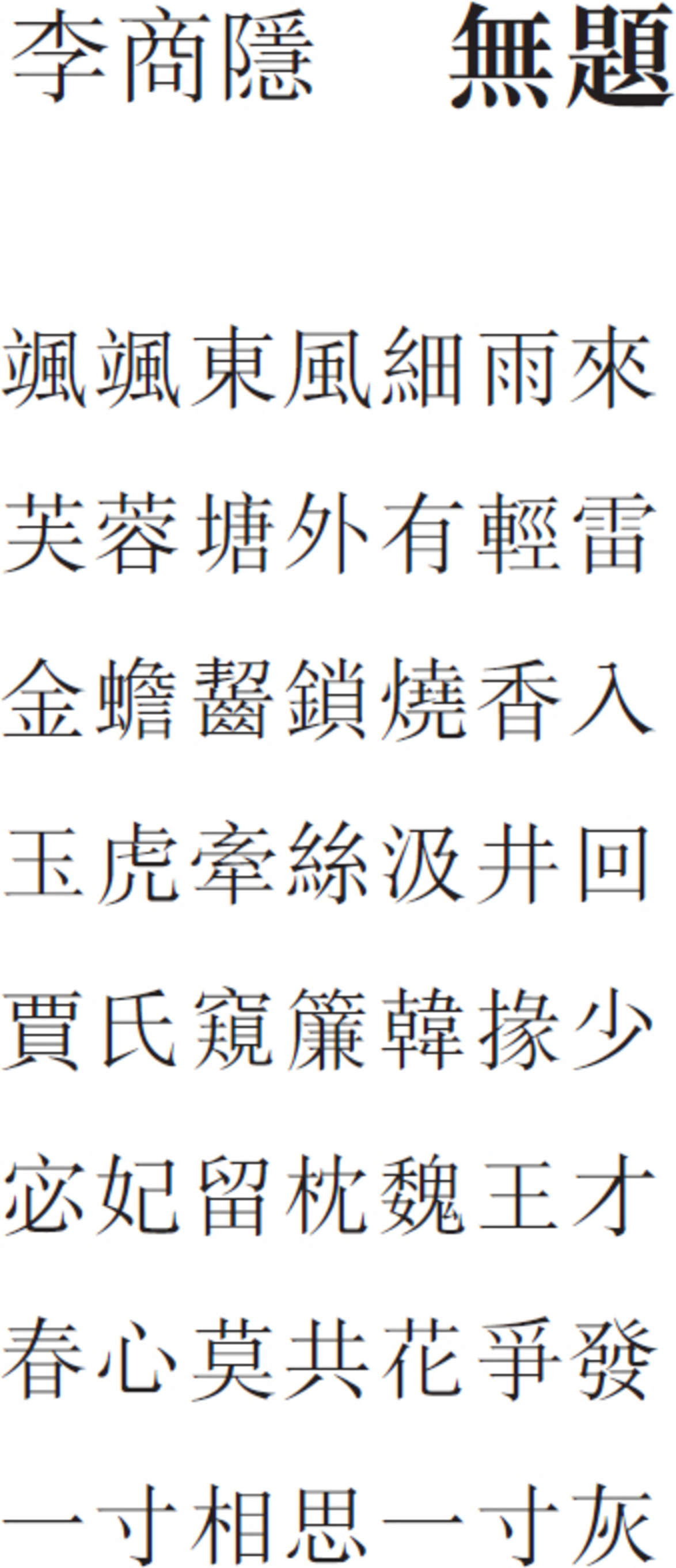

LI SHANG-YIN

Untitled

Phoenix tails, the fragrant silk,

how many gauzy folds

Green filigrees, the canopy,

late into night she sews

The fan cuts the moon’s light,

it cannot hide her blush.

The carriage goes, the thunder sounds,

words can’t get through.

Long in silent solitude,

as candle bums to dark.

Cut off, no word, and who

would bring red pomegranate wine?

The piebald horse is tied as always

to the trailing willow tree

But where is the southwest wind,

here the good breeze?

Lines 1 and 2: These lines describe the bedcurtain of a bridal chamber. The whole poem most likely presents the thoughts of a woman in love, in her solitude.

Lines 6, 7, and 8: Several of these images have a strong sexual connotation: “red pomegranate wine,” beyond the notion of explosive desire that it suggests, may also indicate the red pomegranate wine served at the wedding feast; “trailing willows” symbolizes the slim body of a woman. In addition the expression “to pluck a willow branch” meant to visit a courtesan. “Southwest breeze”: erotic desire. Cf. the lines of Cao Zhi (192–232):

I would become that southwest wind

Waft all the way to your bosom.

LI SHANG-YIN

Untitled

Hush of the East wind; a fine rain comes.

Beyond the lotus pool; faint thunder.

Through the golden toad’s clenched jaws,

the incense fragrance enters.

The jade tiger pulls the silken rope

as it turns above the well.

Lady Jia peeked through the screen

at young Secretary Han

Princess Fu bequeathed her pillow

to the talented Prince of Wei

Yet I won’t let this inch of heart bloom with the Spring.

A single inch of longing, a single inch of ash.

For an analysis of this poem, see this page–this page. We have made no attempt to translate this poem.

CHANG hAN

At the Po-shan Monastery

Clear dawn enters the ancient temple.

First sun brightens lofty grove.

Winding paths: lead off toward secret places.

Chan chamber: flowers deep among the trees.

Mountain light: joy, the birds’ nature.

Pool shadows: empty, the hearts of men.

All sounds, here fall to silence.

All that remains, the bell-stones tone.

For lines 5 and 6, see this page–this page à propos the omission of the preposition, and this page–this page on linguistic parallelism.

ZHANG JI

Coming at Night to a Fisherman’s Hut

Fisherman’s hut, by the mouth of the river,

Water of the lake to his brushwood gate.

The traveler would beg night’s lodging,

But the master’s not yet home.

The bamboo thick, the village far.

Moon rises, fishing boats are few.

There! far off, along the sandy shore,

The spring breeze moving in his cloak of straw.

LIU CHANG-QING

Searching for the Taoist Monk Chang at South Creek

The way, crossed by many paths,

The moss, by sandal tracks.

White clouds lean, at rest on the silent island.

Fragrant grasses bar the idle gate.

Rain past, observe the color of the pines.

Out along the mountain, to the source,

Flowers in the stream reveal Chan’s meaning.

Face to face, and all words gone.

See this page–this page concerning the omission of the personal pronoun.

The visit to a monk or a recluse is a theme very dear to the Tang poets (see the quatrain of Jia Dao). Here, in very simple language, the poet suggests that the way that leads him up to the dwelling of the monk is in itself a spiritual experience, and that over the course of his walk, even before he sees his host, he has already become infused with Chan (Zen in Japanese). When, at last, visitor and host find themselves face to face they are in an ecstatic state, “beyond words.” Certain commentators suppose that the visitor did not see the monk (that they communicated only in spirit), and that the expression “face to face” is applied to the visitor and the flowers. The image of the flower recalls the Buddha smiling at the flower, a symbol of illumination. Let us recall here that the expression “all words gone” (wang yan), which comes originally from the Taoist philosopher Zhuang-zi, was first used in poetry by Tao Yuan-ming (365–427) in his famous “Libation”:

…Pluck chrysanthemums near eastern hedge,

And contemplate, ravished, South Mountain,

The mountain air is purer still, toward evening,

When the birds return together.

In the heart of this, True Essence dwells.

Try to say it? All words, already, gone.

It is important that both poems are ended by this expression, as if the poet dreamed of going beyond words, of attaining nonbeing. However, this going-beyond can only be attained through words: all the way through both poems the poets are attempting precisely to enter into communion with nature by means of tricks of language, by cheating with the signs. Thus, the two poems are not “descriptive” in nature; they are in themselves an experience of wordlessness through words, an “initiation” into “pure significance.”

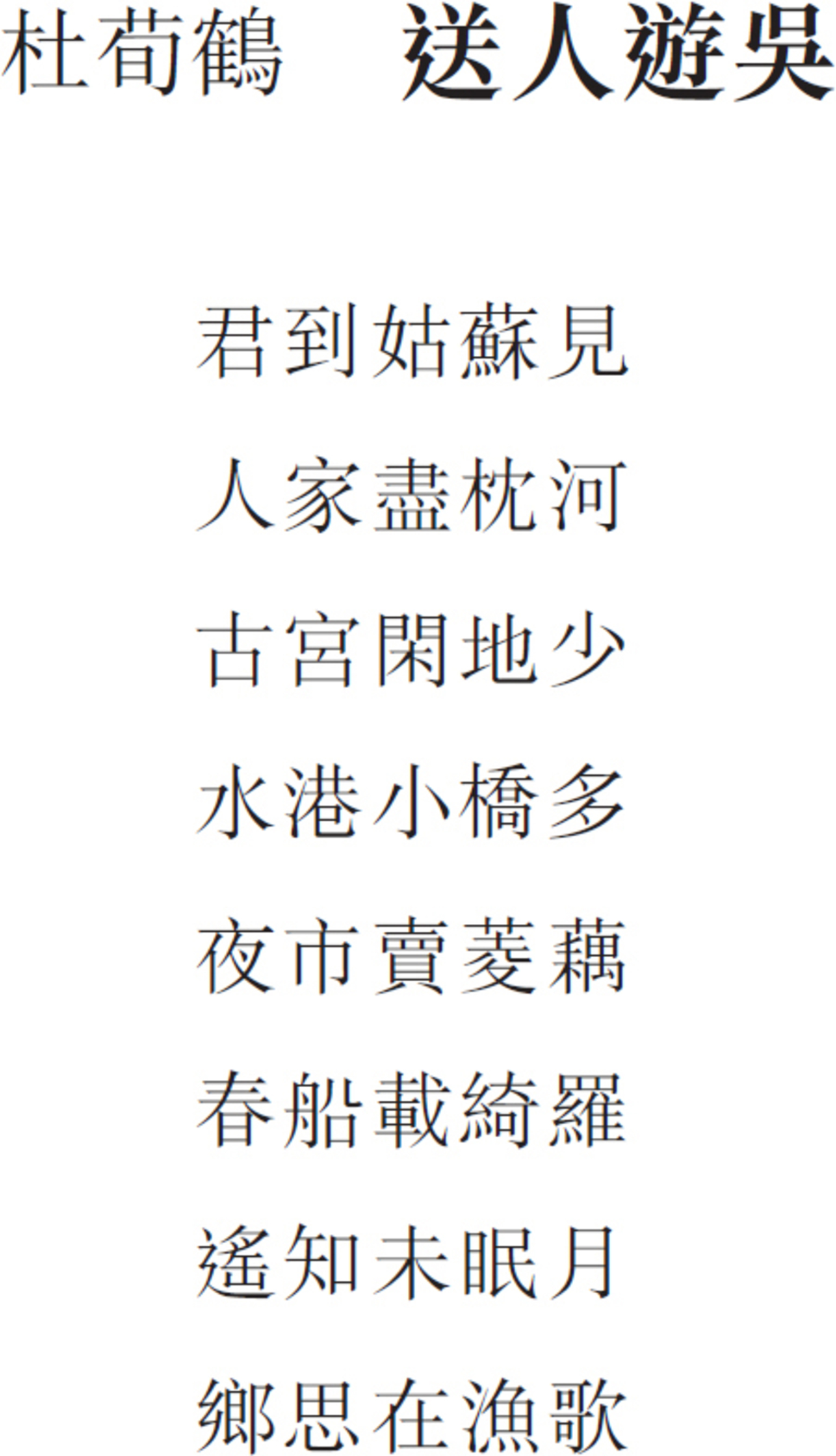

DU XUN-HE

See a Friend off to Wu

I see you to Gu-su

Homes there, sleeping by the stream.

Ancient palace, few abandoned spots.

And by the harbor, many little bridges.

In the night market, lotus, fruit and roots.

On the spring barges, satins and gauze.

Know, far off, the moon still watches.

Think of me there, in the fisherman’s song.

Gu-su, actually Su-zhou, is in the heart of the region known as Jiang-nan (South of the River), an area characterized by its gentle climate, its luxuriant countryside, and its refined customs. Su-zhou, along with Hang-zhou, another waterside city, was commonly spoken of as a heaven on earth.

Line 6: satins and gauze = beautifully dressed promenaders.

WEN TING-YUN

Leaving Mount Shang at Dawn

Up at dawn, shake the bells on the mules.

The traveler goes, thinking sadly of home.

Cockcrow, moon on the thatch of the inn.

Footprints, in the rime on the planks of the bridge.

Leaves all fallen, on the mountain road,

Blossoms shine, on the post station wall.

Dreaming again of Du-ling:

Wild geese at rest, scattered on the pond.

Lines 3 and 4: see this page–this page concerning the omission of the verb.

Lines 7 and 8: The ambiguity presented in these lines is apparent in the original. While it may be the geese that dream of Du-ling, it may also be understood to be the poet himself, newly awakened from such dreams, looking with nostalgia upon the wild geese that linger on the marsh as he departs upon his journey. Du-ling is a famous spot near Chang-an where the poet once lived.

WEN TING-YUN

South Ferry, in Li-zhou

Quiet, vacant waters face the setting sun

Distant, twisted islets blend with the hills of the shore.

On the waves a horse is neighing; see, where the oars go!

By the willows men are resting, awaiting there the boat’s return.

From clumps of weeds along the strand, flocks of gulls disperse.

Above the river’s endless field, a single egret flies.

But who’ll still board this craft, in search of old Fan Li,

On the misted waves of Five Lakes, to lose all worldly schemes?