2. The Active Procedures

The processes that will be studied in this chapter are described as active because they involve the prosodic forms and rules that were sought out and defined by the poets. These forms and rules will not merely be described: an attempt will be made to grasp all of their implications as well. It must be self-evident that these active processes do not function independently of the passive procedures described in chapter 1; the two depend upon each other in the constitution of a properly poetic language.

Chinese poetry knew an uninterrupted development of forms. The initial epoch is marked by two collections of songs, which represent two genres, the Shi Jing (“Canon of Poetry”) and the Chu Ci (“Songs of the State of Chu”). The Shi Jing, which dates from the first half of the first millennium before our era, is composed of ritual chants and popular songs that sprang from the womb of an agricultural society. The constant themes of these songs are the labor of the fields, the pains and joys of love, the seasonal feasts, and the rites of sacrifice. All of the songs are striking for their sober and regular rhythm, the lines dominated by the quaternary meter.

The Chu Ci appears later, toward the fourth century before our era, in the Period of the Warring States, in the region of the Blue River, an area that was at that time on the outer edge of Chinese civilization. This poetry contrasts with that of the Shi Jing as much in the nature of its content as in its form. Of shamanic inspiration and incantatory style, it possesses a great abundance of floral and vegetal symbolism that has both magical and erotic implications. The lines of the form are of unequal length, generally two lines of six feet, joined together by a syllable of measure, xi. It was primarily this genre that later inspired the poets to express the phantasms of the imagination.

Under the Han (206 B.C.–A.D. 219) the continuation of the tradition of the Shi Jing was no longer assured. The poet-erudites gave themselves to the composition of fu (rhythmic prose), while contemporary popular songs were returned to prominence by the Music Bureau (yue-fu), a government bureau instituted by Emperor Wu around 120 B.C., and charged with the collection of folk songs. These songs, marked by a spontaneous lyricism and a greater formal freedom, in turn exercised considerable influence on the poets. From the late Han to the epoch of Tang two parallel genres developed, a popular and a learned poetry, both dominated by the pentasyllabic meter. During the Three Kingdoms (220–265/70), the Jin (265–419), and the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589), following the Han, a vigorous popular poetry flourished, while generations of poets concurrently produced works of great literary value, preparing the way for the poetry of the Tang. In the course of this long period new forms, including quatrains, heptasyllabic poems, and long narrative poems, were developed.

At the beginning of the Tang all these new genres in use were catalogued and codified, partly because formal research had by that time achieved a high degree of refinement, and moreover to meet the needs of the imperial civil service examinations. This fixing of forms in synchrony is an important fact. In the awareness of the Tang poet, the ensemble of these forms constitutes a coherent system, one in which the relationship among the forms is clearly defined, and one that provides vehicles for the multiple registers of the poet’s sensitivity.

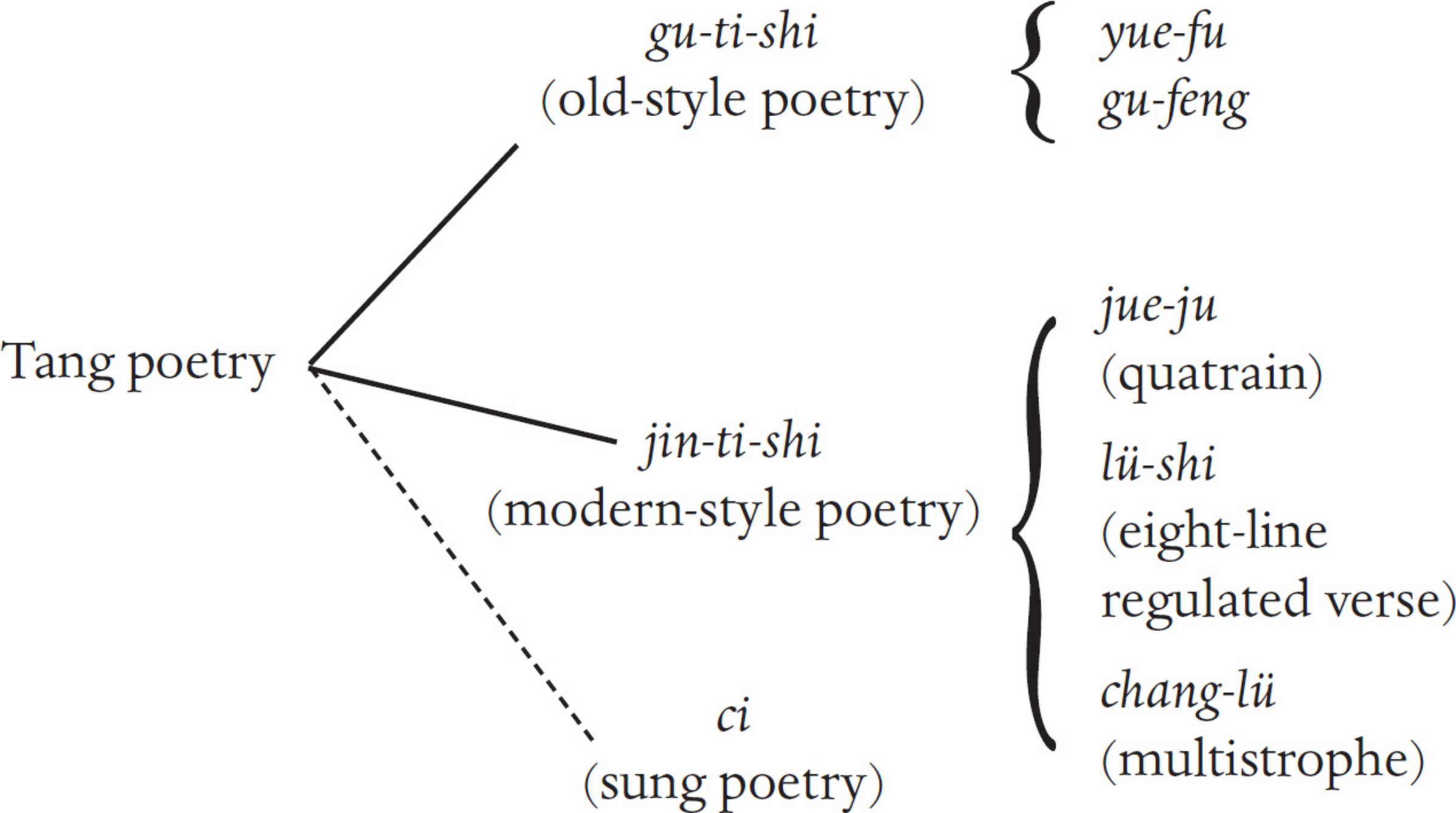

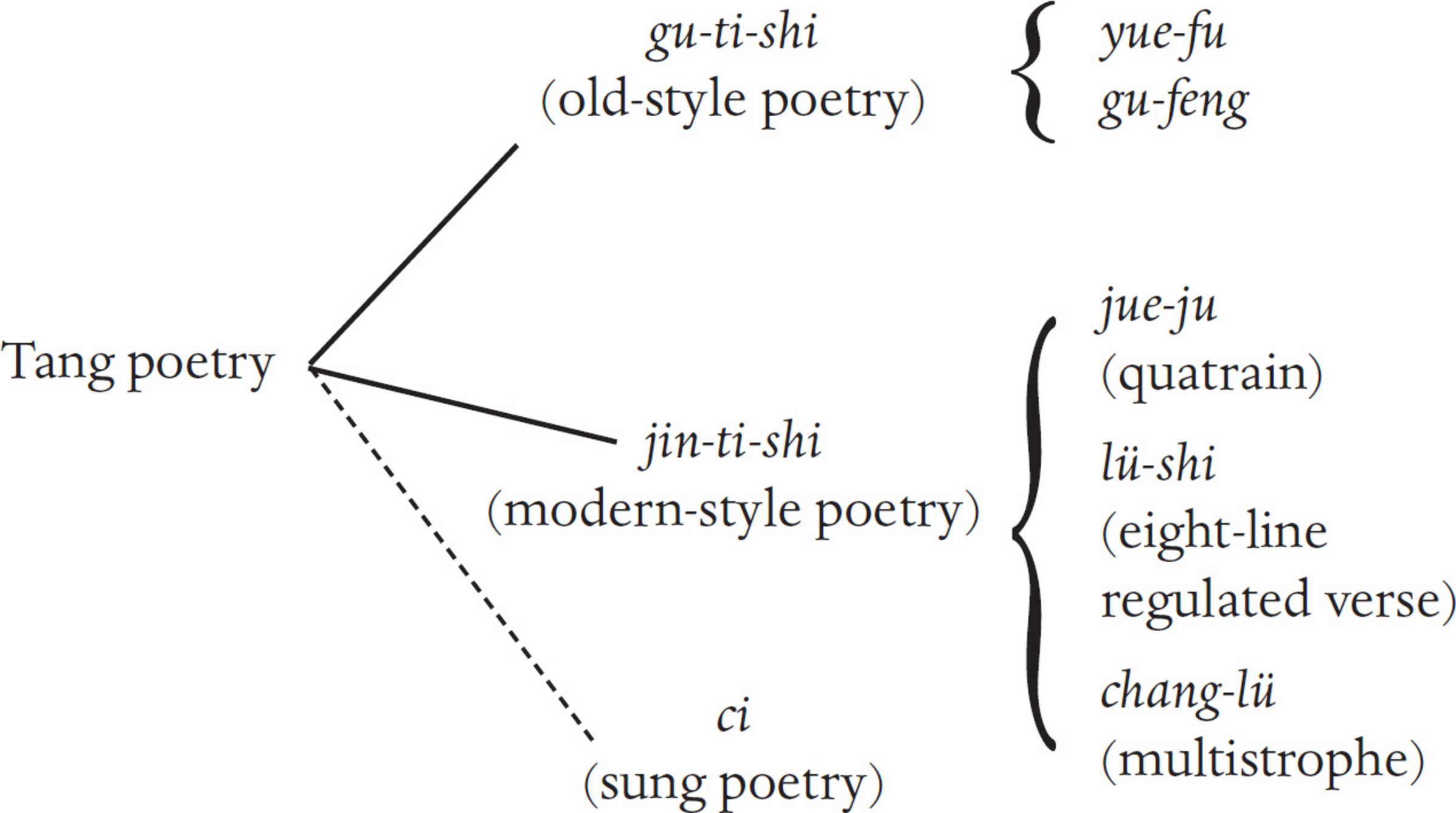

The first distinction made is between jin-ti-shi, “modern-style poetry,” governed by strict rules of prosody, and gu-ti-shi, “ancient-style poetry,” which is distinguished by the absence of constraints, or more often by the intentional deformation of these same rules. Within the gu-ti-shi two currents, the popular yue-fu and the learned gu-feng, were both widely practiced. In modern-style poetry, the most important form is the lü-shi (regulated eight-line poem); it is in relation to this form that the jue-ju (quatrain), considered to be a “cut off” lü-shi, is defined, as is the case with the chang-lü (“long lü-shi“), which is, as the name implies, a prolonged lü-shi, with multiple strophes. In addition, it may be appropriate to mention a form of song-poetry, intimately tied to music, called the ci, which developed toward the end of the Tang, and had its vogue during the following dynasty, the Song.

In this network of forms, the lü-shi (regulated eight-line poem) is the reference point from which all of the others are defined. This form, which is the culmination of many centuries of aesthetic exploration and research, in addition to putting the specific traits of the language to the best possible use, represents, as well, a certain philosophical conception essential to the Chinese. It is a system whose different levels are composed of elements in internal opposition, and whose progression obeys a fundamental dialectical law. Viewed from this perspective, the analysis of the lü-shi offers, among other things, an opportunity to observe the process by which a form may engender meaning.

The lü-shi

First of all, the lü-shi is striking by virtue of its “economic” aspect. It constitutes, in the eyes of the Chinese poet, a sort of “complete minimum.” A lü-shi is composed of two quatrains, and each quatrain of two couplets. The couplet is, then, the basic unit. Of the four couplets that compose a lü-shi, the second and the third are obligatorily formed of parallel lines; the first and the last, of nonparallel lines. The contrast between the parallel and the nonparallel lines is characteristic of the lü-shi, a system formed of oppositional elements on all levels (phonic, lexical, syntactic, symbolic, etc.). A network of correspondences between these levels allows them to mutually support and imply each other.

Cadence

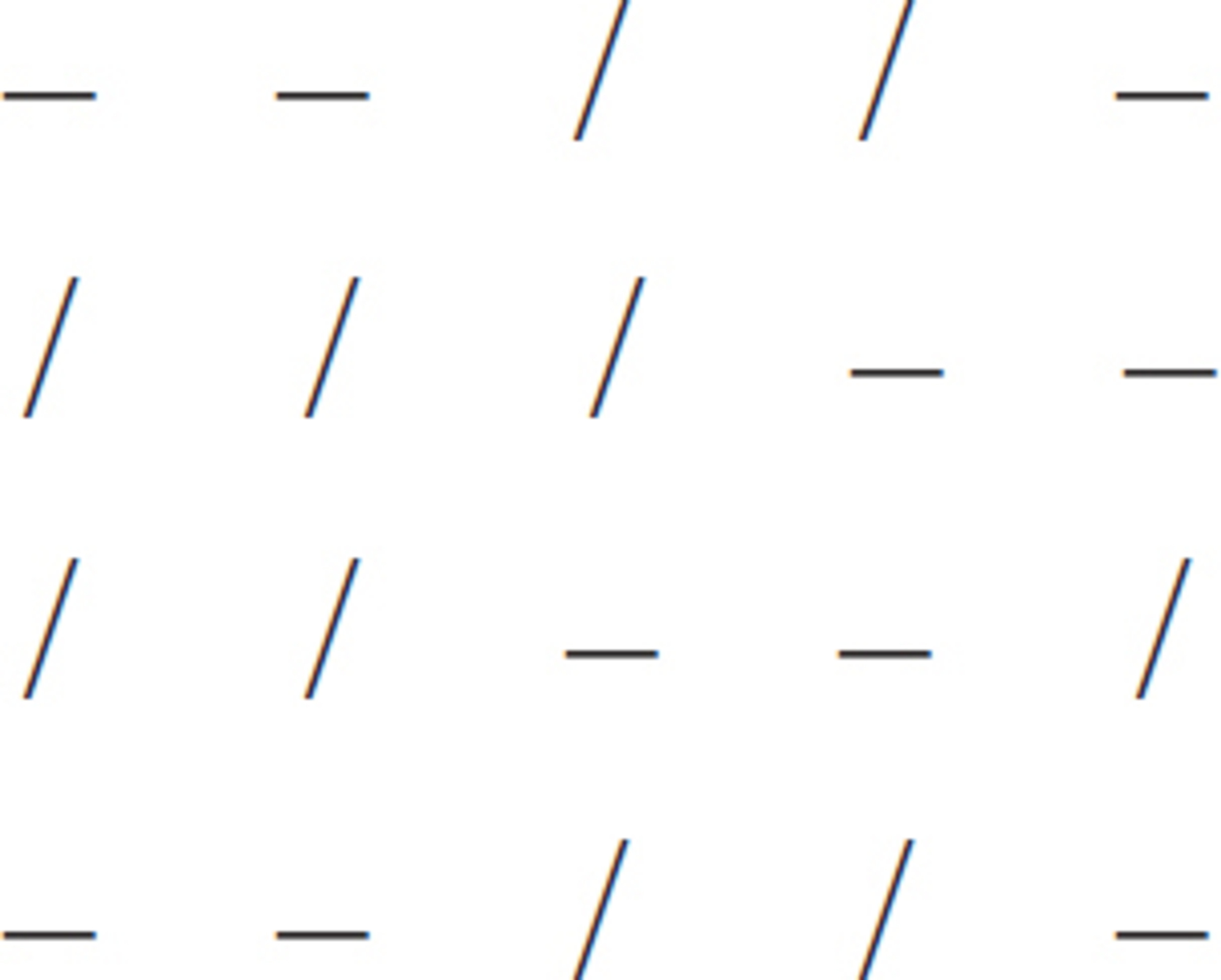

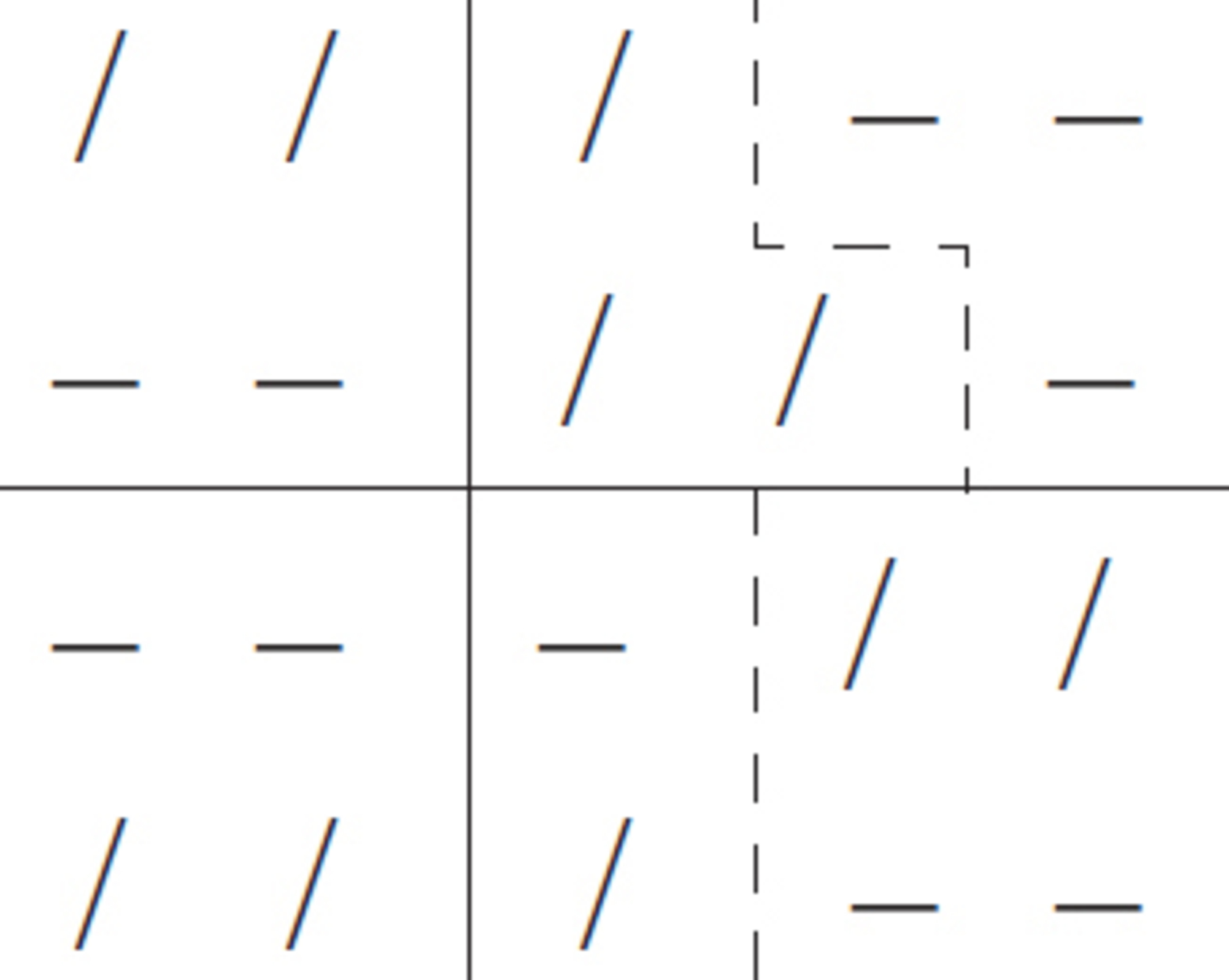

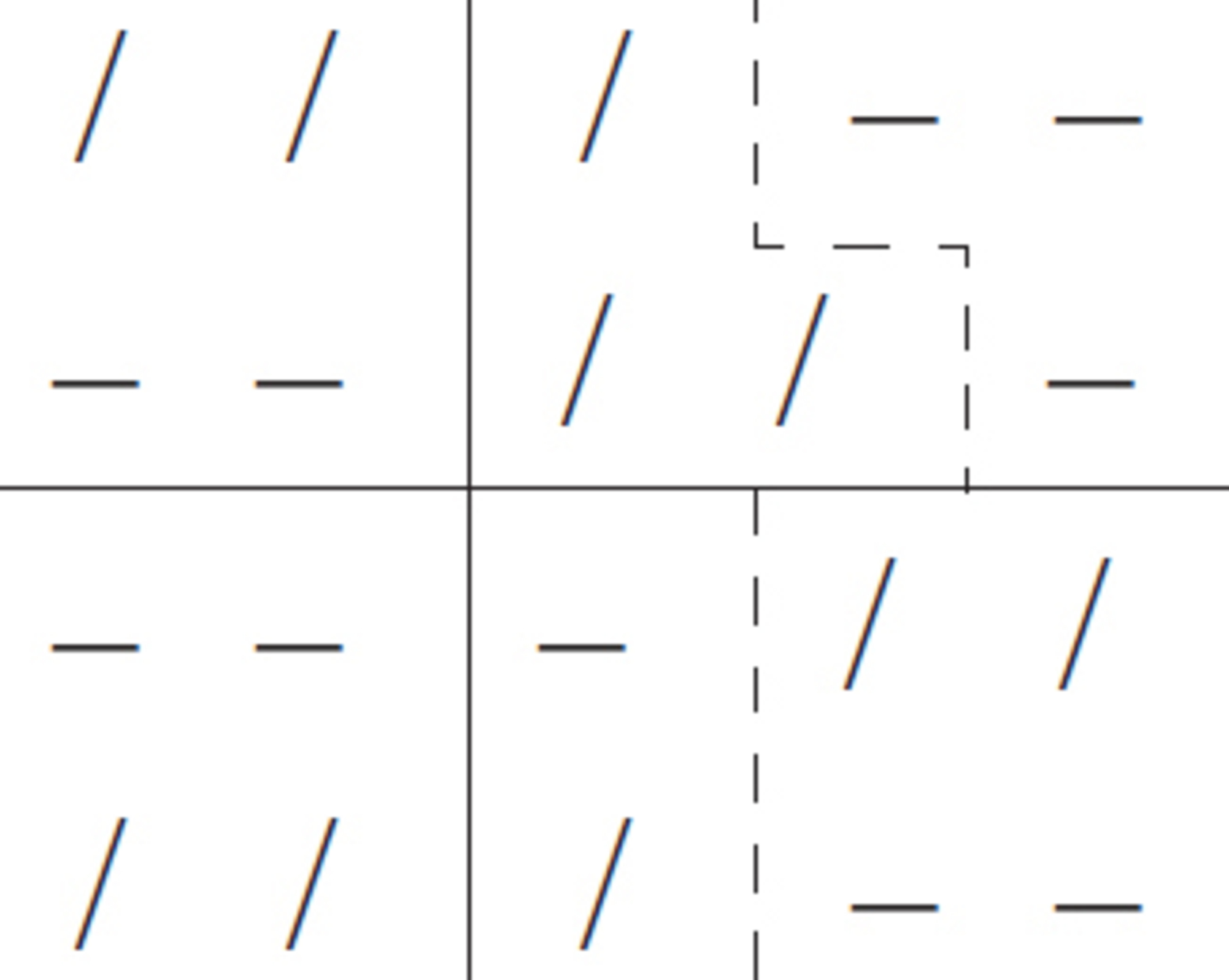

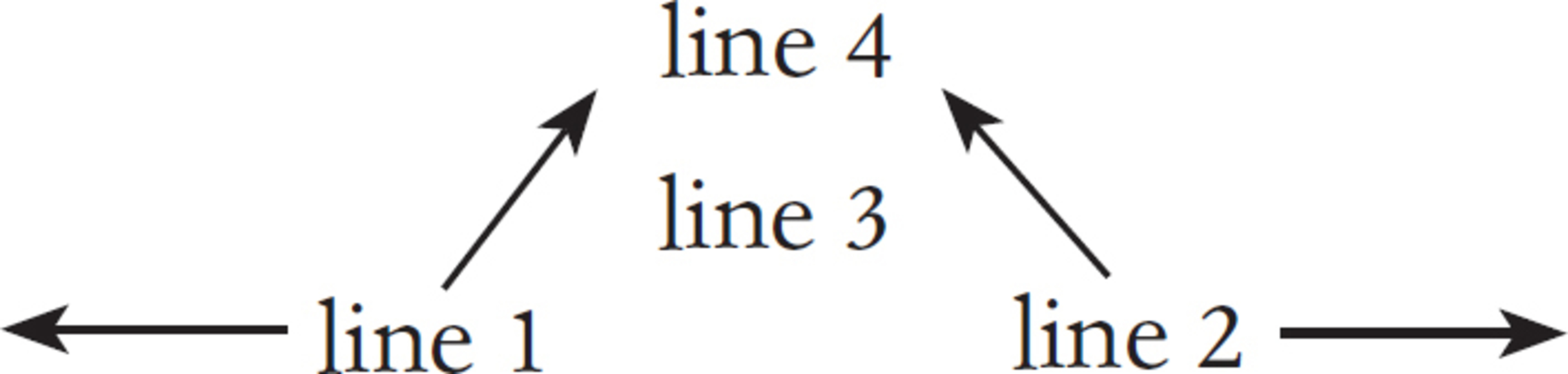

In a given lü-shi a line can be either pentasyllabic or heptasyllabic, which is to say that the line may be composed of either five or seven characters, since in Chinese each character counts invariably as one syllable (and the words themselves, in ancient Chinese, are often made up of only one character). In poetry, where the syllable is the basic unit, there is no gap between the level of the signifiers and that of the signifieds, each syllable always having a meaning. The caesura is found, in the pentasyllabic line, after the second syllable, and in the heptasyllabic, after the fourth. On the two sides of the caesura there also exists an opposition between the even numbers (two and four syllables) and the odd numbers (three syllables), an opposition accentuated by the cadence, which is, remarkably, iambic before the caesura and trochaic after it (

![]() accented syllable):

accented syllable):

pentasyllabic:

![]()

heptasyllabic:

![]()

This rhythm, where the even and the odd syllables are accented in turn, is created, in a way, by a series of small collisions. Perhaps an image will be helpful here: the caesura is like a seawall against which the rhythmic waves strike:

![]() ; there follows a return wave, which engenders a contrary rhythm:

; there follows a return wave, which engenders a contrary rhythm:

![]() . This contrastive prosody wakens all of the dynamic movement of the line. It is appropriate to point out here that the opposition between even and odd numbers is based on the idea of yin and yang (the yin represented by the even, and the yang by the odd numbers), and that the alternation of yin and yang, as is well known, represents for the Chinese the fundamental rhythm of the universe.

. This contrastive prosody wakens all of the dynamic movement of the line. It is appropriate to point out here that the opposition between even and odd numbers is based on the idea of yin and yang (the yin represented by the even, and the yang by the odd numbers), and that the alternation of yin and yang, as is well known, represents for the Chinese the fundamental rhythm of the universe.

Beyond the rhythmic function that it performs, the caesura also plays a syntactic role, regrouping the words of a line into distinct segments that are in opposition to each other and that support the links from cause to effect.1 In the poem “Captive Spring,”2 for instance, Du Fu uses the caesura to mark the contrast between certain images: “Country broken | mountain-river remain” (the country is torn apart but the rivers and mountains remain); “regret time | flowers shed tears” (regretting the time that flies, even the flowers shed tears). By way of contrast, Wang Wei underlines the subtle links that exist between apparently independent images through the use of the caesura, which suggests the void: “Man rests | cassia flowers fall; night calms itself | spring mountain’s empty.”3

Rhyme

Concerning rhyme, one simple detail: except for the first line (which will be discussed later), the rhyme always falls on the even lines. The fact that the odd lines remain unrhymed is an important trait of Chinese poetry, creating as it does an additional structural opposition, between even and odd lines. There is no change in rhyme within one lü-shi; one single rhyme, from even line to even line, “runs through” the whole poem. In addition the poet must choose a word with the tone referred to as “level,” the plainest, and longest, of the four tones of old Chinese. All of which leads to the next important feature of Chinese poetry: tonal counterpoint.

Tonal Counterpoint

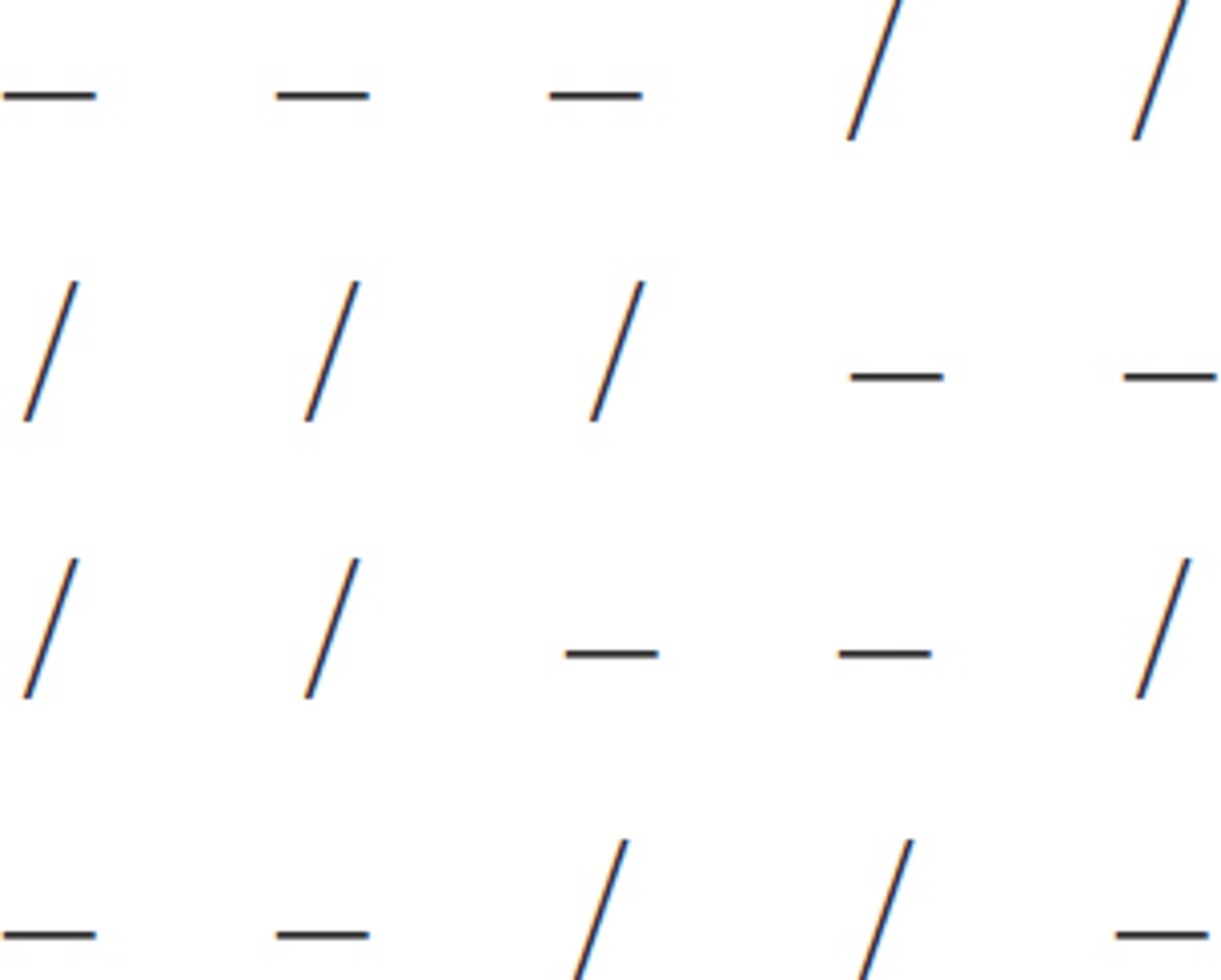

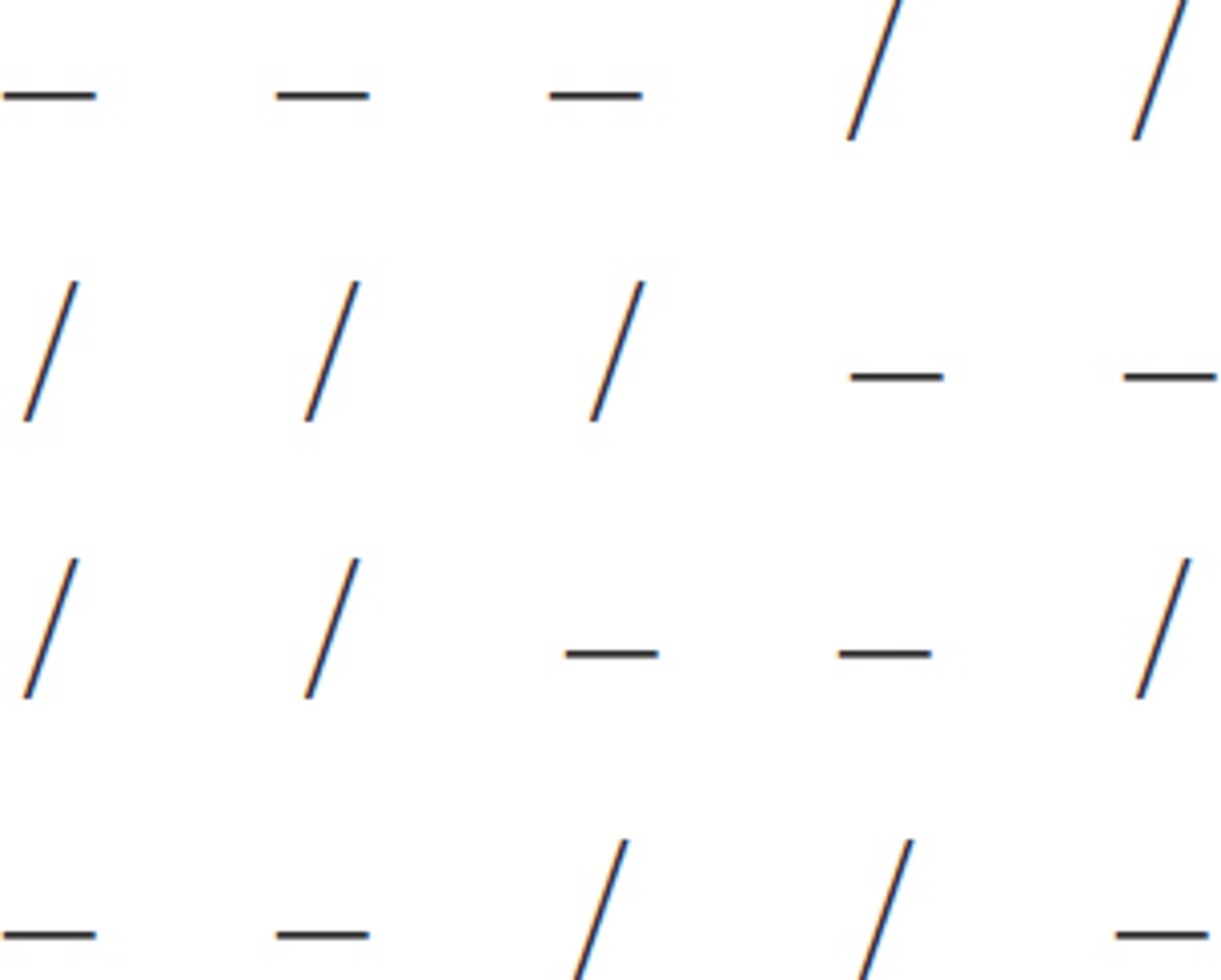

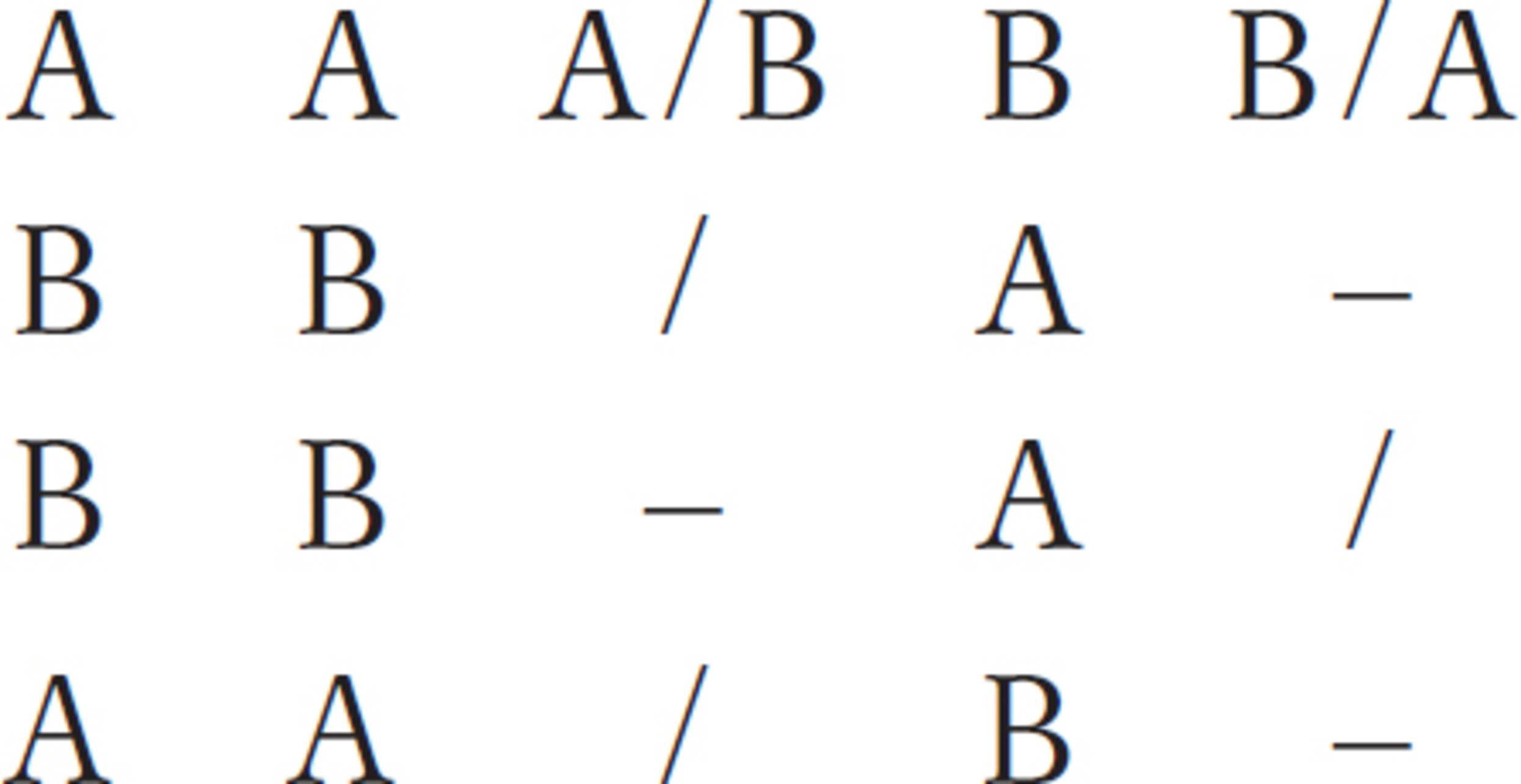

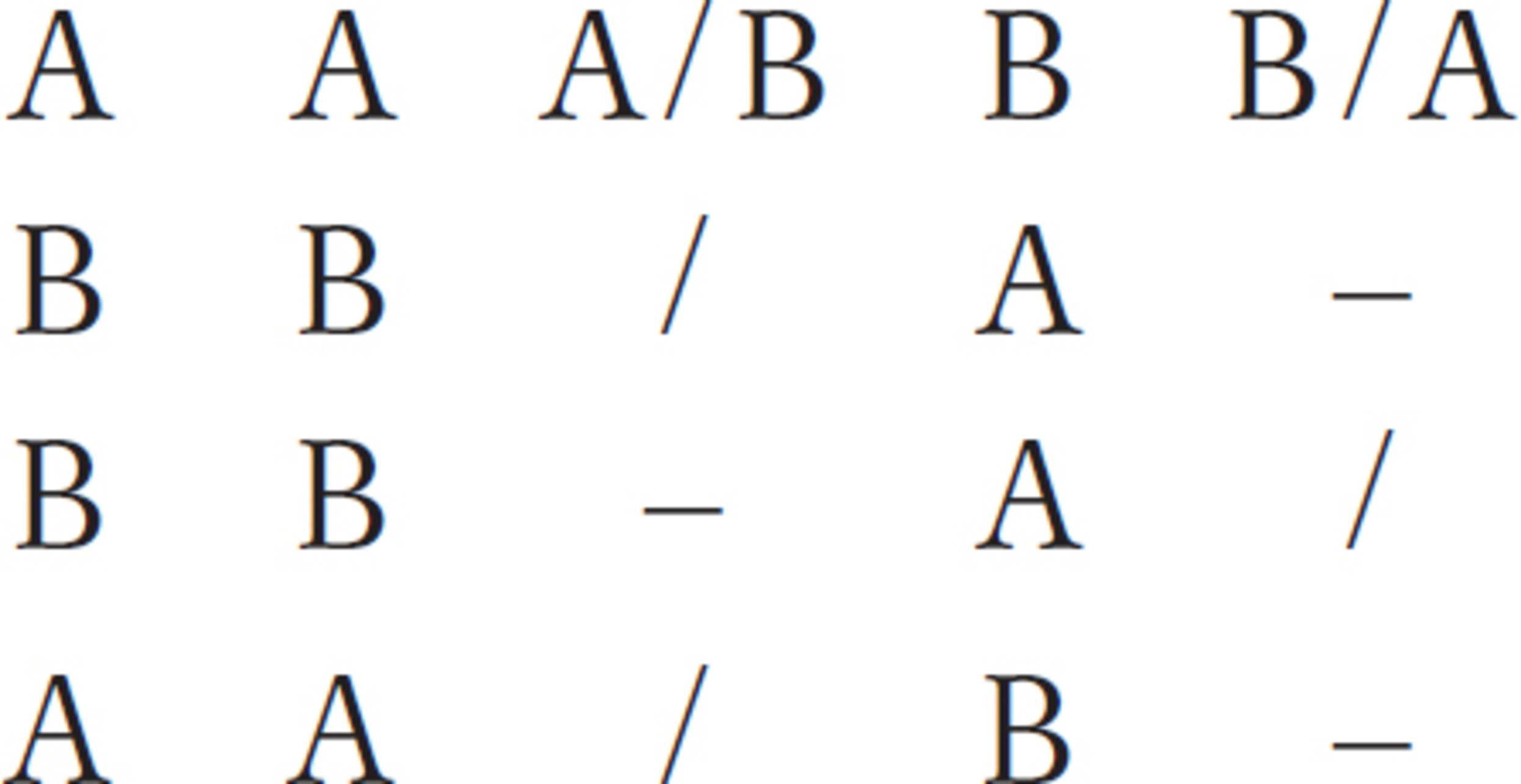

Chinese is, indeed, a tone language, and the musicality that is provided by tonal combinations was very early evident to the poets.4 A lü-shi is ruled on the phonic level by rigorously defined tonal rules. The poet must observe a distinction between the “level” tone (the first and second of the four tones of modern Mandarin) and the “deflected” tones, “mounting” (modern third tone), “parting” (modern fourth tone), and “entering” (no longer present in modern Mandarin, but represented by the final consonant in Cantonese and some other dialects), taken as a group. This distinction is based, in theory, on the fact that the first tone is level in pitch and relatively long, while the other three tones share modulation of pitch and shorter length.5 Tonal counterpoint arises in the pentasyllabic and the heptasyllabic lü-shi from set schemes of alternation between these two types of tones. The poet is required to choose words whose tones conform to the obligatory patterns that are represented below (—represents the level tones, and / the deflected).6

(1) Pattern beginning with a deflected tone:

(2) A variant of this first pattern, in the case where the first line also carries a rhyme. Since the rhyme word must belong to the level tone class, the first line is changed accordingly.

(3) Pattern beginning with a level tone:

(4) A variant of this form is also provided, for the same purpose as the variant under number 2 above.

Each of these patterns may be taken as a play of abstract signs and made the object of numerical or combinatory analyses. We will not forget, however, that the patterns are designed primarily for the service of the poetic language, and will only raise those points here that seem pertinent to that subject. In the first pattern, for example, note the two internal divisions available to the prosody.

The vertical line marks the caesura, while the horizontal marks the separation between the two couplets. On either side of the vertical line there exists a contrast of number, even/odd: before the caesura, there are two syllables with the same tone. After the caesura, there are three syllables, two of which have the same tone (but a tone that differs from the tone preceding the caesura) and one that differs from them. The distribution of the tones conforms to the rhythm of the Chinese poetic line, which as already indicated is made of groups of two syllables plus one isolated syllable. Thus in tonal counterpoint the combinations – / or / – before the caesura, and the combinations / / / and – – – after the caesura, are banned. Tonal opposition is made not only in the interior of the line, moreover, but also between the two lines of the couplet, in a regular symmetrical pattern, as can be seen from the figure above. This symmetry is put slightly askew in the case of the variant pattern (2):

Here, in the first couplet, after the caesura, the opposition between the two lines is not symmetrical, but “reflected,” to use the definition of Roman Jakobson;7 the figure of the first line finds its mirror image in that of the second line.

Pattern 3, which starts with a level tone, is obtained by the simple act of reversing the order of the couplets in pattern 1, by beginning with the second couplet of that pattern and following with the first.

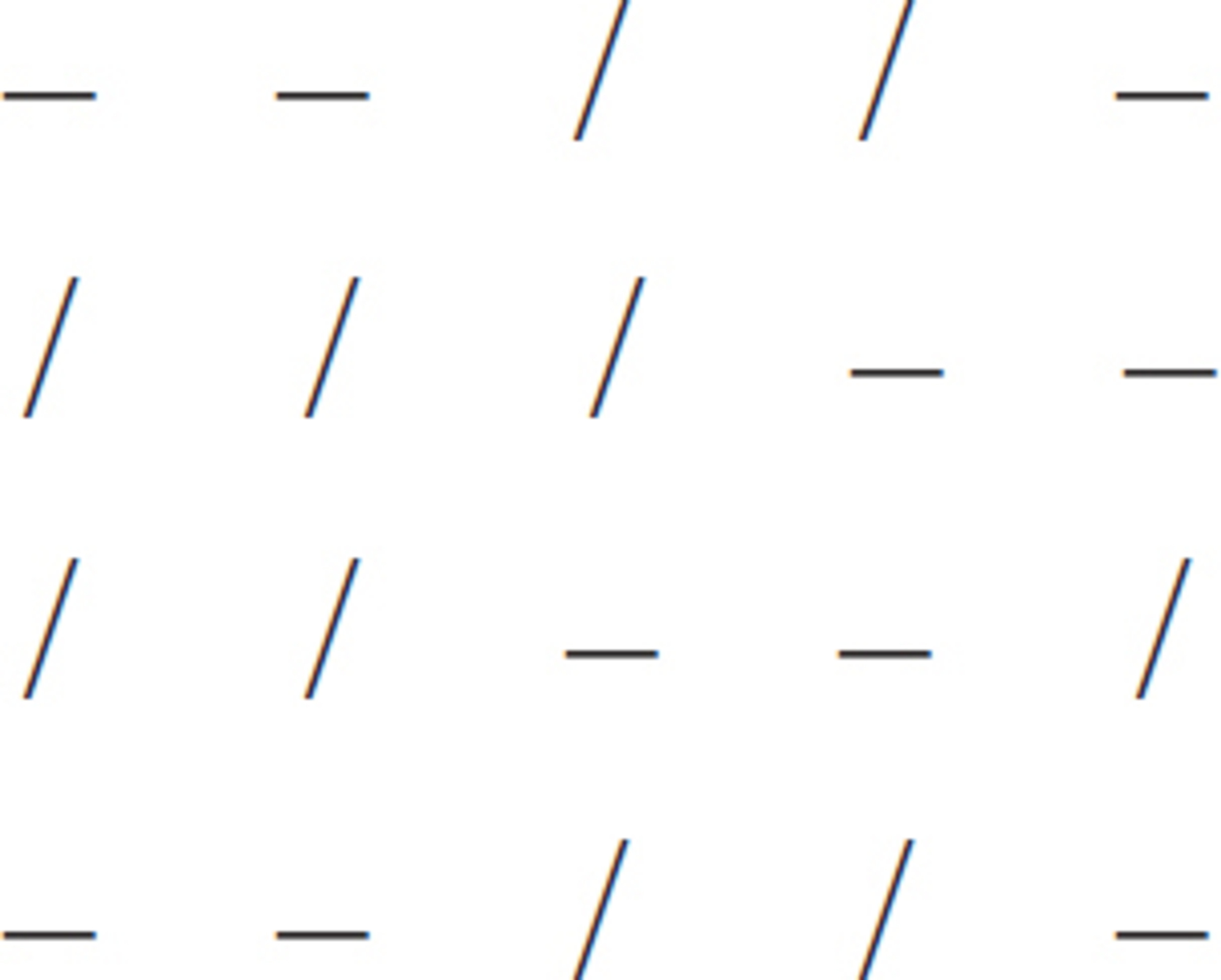

A simplification of these patterns is possible when certain features of the poetic language in general are kept in mind. The constraint of the prosody, the fact that the rhythm is based on groups of two plus one syllables, the obligatory level tone of the rhyming words, and the fact that rhyme only occurs on the even lines—when these elements are taken into account it is possible to construct a single schema as a representation of the four variant patterns:8

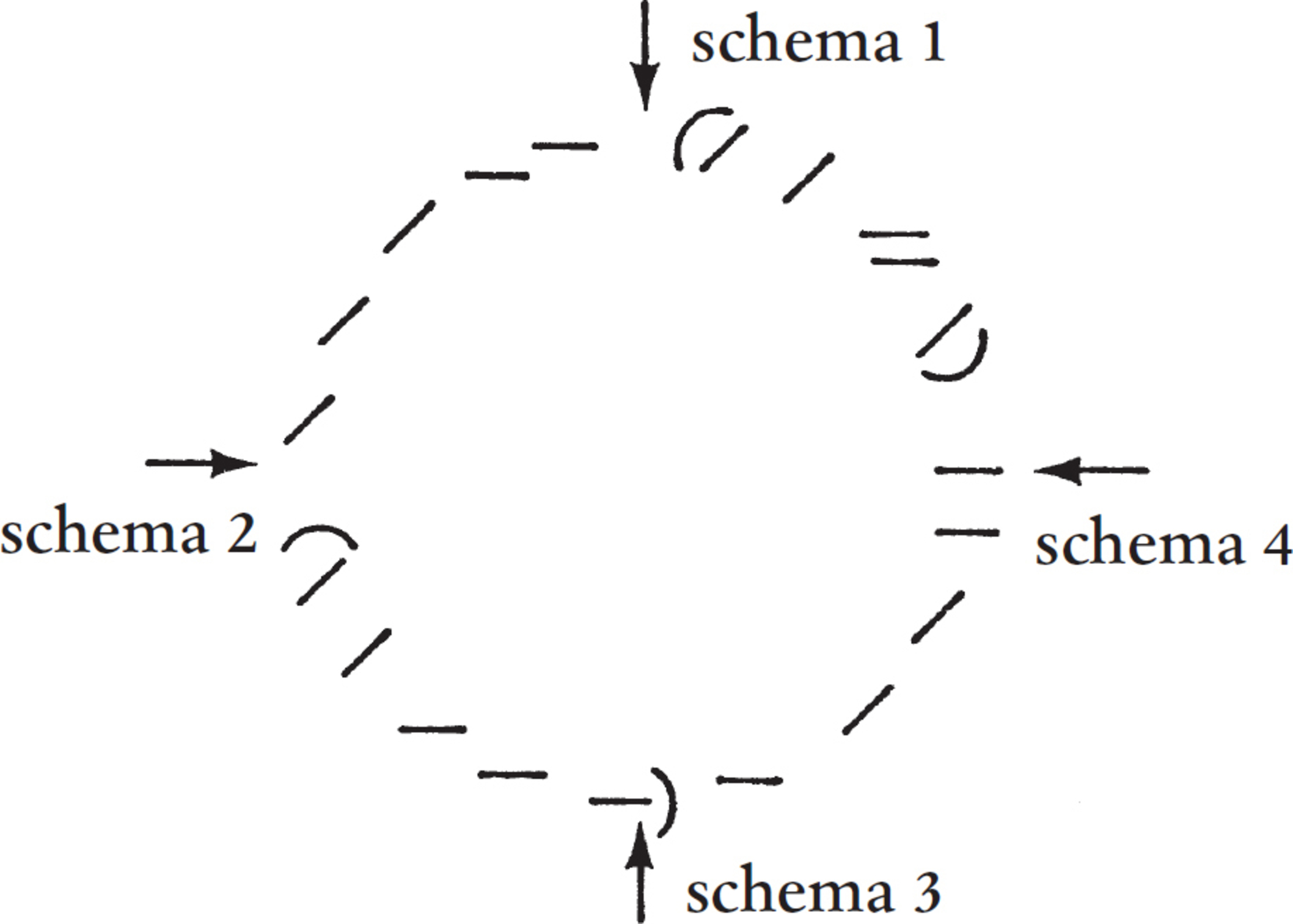

Though this schema might give the impression of a static composition, it should be held in mind that tonal counterpoint is above all a dynamic system, in which an element may be developed and transformed, attracting similars, but also calling up its opposite, according to the rules of correlation and opposition. A circular figure may, indeed, better suggest the processes involved.

To locate the four patterns from this figure, it is only necessary to begin from the indicated point and move clockwise, excluding the elements in parentheses for the variant patterns 2 and 4.

What occurs here then, beneath the network of syllables (and the syllable is, let us recall, the basic unit of both sound and meaning in Chinese poetry), is essentially a contest, a restless movement that unrolls, oscillating between a static or stable pole (the level tone) and a dynamic one (the deflected tones). Tonal counterpoint thus constitutes the first of the multiple levels of that system of internal oppositions that is the lü-shi.

Musical Effects

Before examining the syntactic aspect of the lü-shi, it remains to give some indication (necessarily rather succinctly, since specifically musical effects are best discussed in relation to particular works) of the principal phonic values of the language that are exploited by every poet.

Since in the Chinese written language each character has a monosyllabic pronunciation, each syllable is potentially significant, and the ensemble of the syllables can be inventoried. Certain syllables, and tied to them certain initial and final consonants, have, through their associations with the words they embody, a particular evocative power. A very common phonic figure in traditional rhetoric is the so-called shuang-sheng, a binom whose two elements are alliterative, like fen-fang (“odorous, perfumed”). Also quite common is the use of certain consonants to set in train a series of words that are very similar in meaning, as in the quatrain “Complaint of the Jade Staircase” by Li Bai.9 Here, in a description of the vain vigil of a woman at night upon her staircase, the poet uses a series of l-initials to successively signify dewdrops, tears, coldness, crystal, and solitude:

Yu jie sheng bai lu

Ye jiu qin luo wa

Que xia shui jing lian

Ling-long wang qiu yue

An elementary example of the use of syllable finals is provided in the so-called die-yun, a binom whose two elements rhyme, as in pai-huai (“go back and forth in a certain place, hesitate”). In a more eloquent example, the poet Li Yu uses a series of -an finals to reinforce the idea of tormented obsession and of melancholy sighs:

Lian-wai yu can-can

Chun-yi lan-san

Luo-jin bu-nai wu-geng han

Meng-li bu-zhi shen shi ke

Yi-xiang tan-huan10

These phonic values do not exist in isolation. Indeed, they are often most clearly manifest through opposition with other phonic elements. A final example will illustrate this effect. As mentioned above, the final -an suggests melancholy. It contrasts with the final -ang, which has a triumphant nuance and evokes sentiments of exaltation, as if the -ang, with its greater duration, were able to “rise above” the melancholy evoked by -an. In the following lines, the poet Han Yu effectively uses this opposition to contrast feminine tenderness (lines 1 and 2) with virile heroism (lines 3 and 4):

Traditional rhetoric also recognizes similar sets of oppositions of effect among the initial consonant.

(1) aspirated/unaspirated: for example, bao (“surround”) / pao (“flee”).

(2) Kai-kou (without the prevocalic u) / he-kou (with the prevocalic u): thus, hai (“child”) / huai (“to carry at the breast”).

(3) Jian-yin (unpalatalized) / tuan-yin (palatalized): for example, ti (“sadness”), di (“to fall in drops”). Inspired by Tang researches, the Song poetess Li Qing-zhao (1084–?) used both of these two kinds of opposing pairs in a very famous poem12 to re-create her sadness as she listened to the falling of the rain.

The musical effect of the opposition of the tones does not escape the attention of the poet either. The most notable opposition is, clearly, that between the first, the long level, and the fourth, which is abrupt. This last is repeated many times, often suggesting a sob, or giving the impression of suffocation. Du Fu, in a poem he composed in celebration of the announcement of peace, calls upon multiple phonic resources (both sounds and tones) to express his joy at the possibility of returning to his native countryside.13 The last couplet, “After the gorges of Ba, I will pass through the gorges of Wu, / Then down through Xiang-yang, on the way to Luo-yang,” is transcribed as follows:

Ji cong Ba-xia chuan Wu-xia

Bian xia Xiang-yang xiang Luo-yang!

The first line of the couplet contains a series of words with the fourth tone and “narrow” finals (xia means “gorge” or “mountain pass”), while the second is made almost entirely of words in the first tone and of -ang finals. The two lines are, in addition, grammatically parallel, term for term. The phonic contrast between the two lines creates the impression of irrepressible shouts of joy upon deliverance from a suffocating imprisonment.

Syntactic Level (Parallel and Nonparallel Lines)

In the area of syntax, the most important feature of the lü-shi is the opposition between parallel and nonparallel lines. As previously mentioned, of the four couplets that make up the lü-shi, the second and the third are obligatorily made up of parallel lines, while, in contrast, the last couplet is obligatorily nonparallel, and the first couplet is nonparallel in principle, though parallel versions are occasionally seen. Thus, the lü-shi presents itself according to the following progression: nonparallel—parallel—parallel—nonparallel. To grasp the significance of this formal transformation within the lü-shi it is necessary to discover, first of all, the nature of the parallel lines themselves.

Linguistic parallelism occupies an important place in Chinese life, as well as in literature. Witness, for instance, the parallel sayings inscribed on temple columns and on either side of the entry-ways of houses and shops. Parallel constructions are also ordinarily used in common sayings, and in festivals and religious rituals. If this practice is a reflection of a dualistic conception of life, its existence is no less tied to the specific nature of the characters of the writing system. Again owing to the fact that in ancient Chinese most words are composed of one character, the poet may, in the two lines of a parallel couplet, arrange terms of the same grammatical paradigm, but possessing opposite (or complementary) meanings, in an absolutely symmetrical pattern. The two lines, thus presented side by side, offer a certain visual beauty. Among the lines cited in the previous chapter, numerous examples (among them the following) of parallel lines have already been cited.14

Light of the mountain | rejoice in mood of birds

Shadow of the marsh | empty heart of man

Here, the images in the two lines are placed regularly face to face (light of the mountain / shadow of the marsh; mood of the birds / heart of the man). If, as we have seen, this couplet offers multiple interpretations, it is precisely because the characters, through their “face to face,” maintain a subtle but lively relationship, nowhere forcing the poet to “slice” the meaning in one direction or the other.

A few more examples, all chosen from the lü-shi of Wang Wei, may further illustrate the form of parallelism.

Clear moon | among the pines shines

Cold spring | over rocks flows15

In these two lines a correspondence is established: clear moon ↔ cold spring, pines ↔ rocks, shine ↔ flow. The poet thus creates a landscape in which light and shadow (from line 1) respond to sound and touch (suggested by line 2).

Immense desert | lone smoke straight

Long river | setting sun round16

Here, always the poet-painter, Wang Wei suggests a complete picture by contrasting different elements of the landscape. The contrast is carried into the interior of each line; it exists between the two lines of the couplet as well. The desert that extends infinitely; the single straight plume of smoke; the river that flows afar; the sun, fixed for a single instant: these contrasts exist within the lines. And between the lines, the static desert and the dynamic river; the smoke that rises and the sun that descends; the vertical line and the roundness; the black and the red.

Flow of the river | beyond sky and earth

Color of the mountain | between being and nonbeing17

Here, the poet introduces the idea of a spiritual experience (of Chan). Between these two lines there is more than a contrast, there is a sort of “going beyond.” If, in the first line, when the reader follows the flow of the river, he rejoins the cosmic movement, yet he still remains under the rule of space. In the second line, where everything is joined in the color of the mountain, one passes subtly from being into nonbeing. None of this, of course, is explicitly stated; rather it is signified by the position of the words in relation to each other.

Finally, after these extracts from the lü-shi, it may be appropriate to cite a quatrain constructed entirely of parallel lines, that is, of two parallel couplets. A quatrain, or jue-ju, was defined during the Tang as half a lü-shi, and might be formed of either two parallel couplets, two nonparallel, or one parallel and one nonparallel. The first type, owing to its difficulty, is perhaps the least common.

White sun | along the mountains disappears

Yellow River | up to the sea hurls itself

(If) desire to exhaust | view of a thousand li

(Then) mount yet | one more story18

In the first couplet, the poet focuses upon a spectacular landscape that he admires from the height of an elevated pavilion. The polar oppositions of this landscape (mountain / sea, sun’s fire / river’s water, heavenly / earthly) and its contrary movement (the sun drawn toward the west, and the river toward the east) arouse in the man feelings both of exaltation and of divisive tension. The second couplet, though it is parallel to the first, is also different (the traditional rhetoric recognizing several distinct types of parallelism) in that it expresses ideas both opposed (view of a thousand li / one story higher) and continuous (if desire…then climb…). By this construction the poet underlines on the one hand the contrast between infinite space and the solitary presence of the man, and, on the other, the desire of the man to go beyond the divided world (the “thousand” of line 3, traditionally an indefinite number, symbolizes the multiplicity of things) and to attain unity for and of himself (“one” in line 4 symbolizing that unity). The four lines superimposed provide a visual representation of the lived scene:

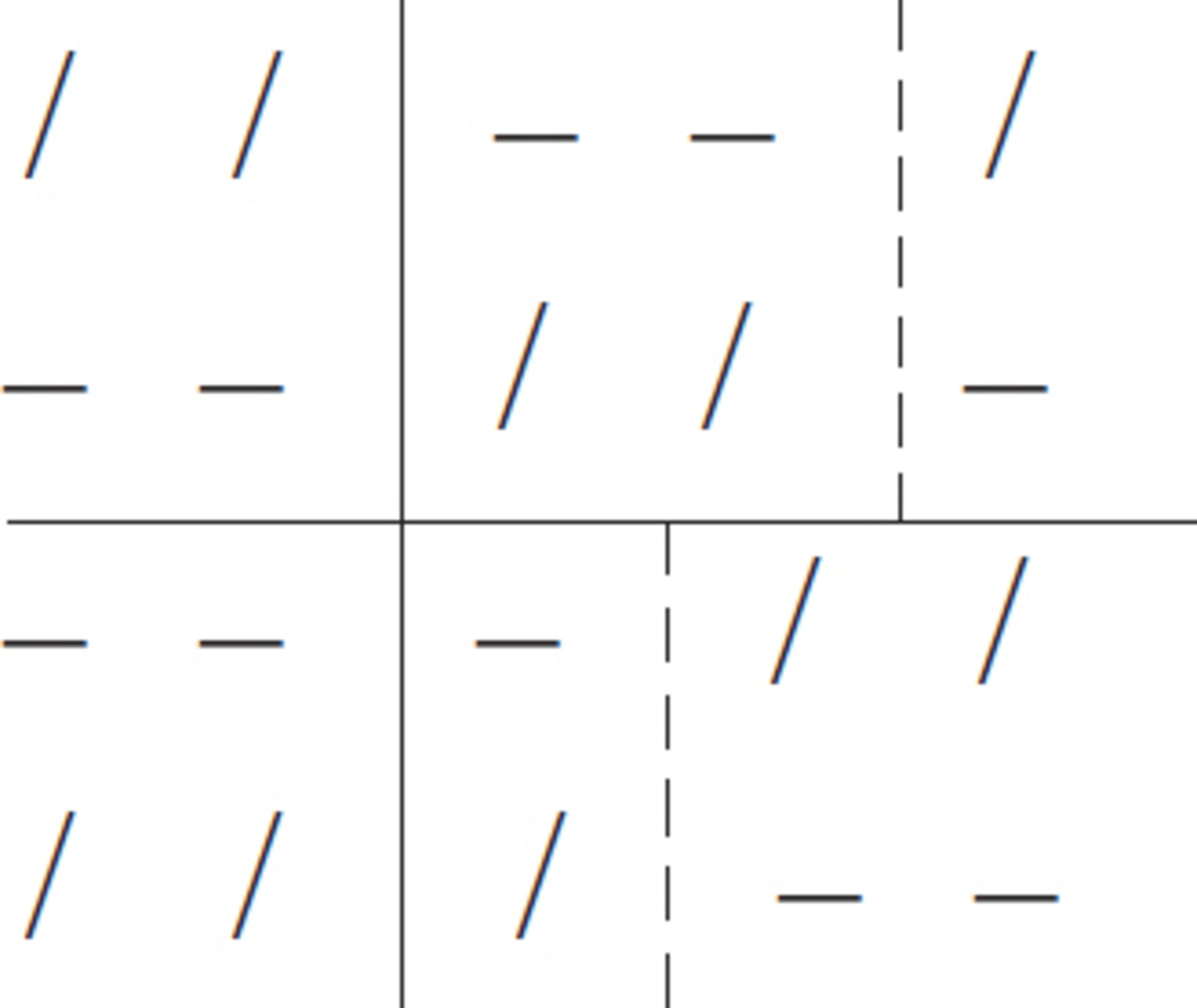

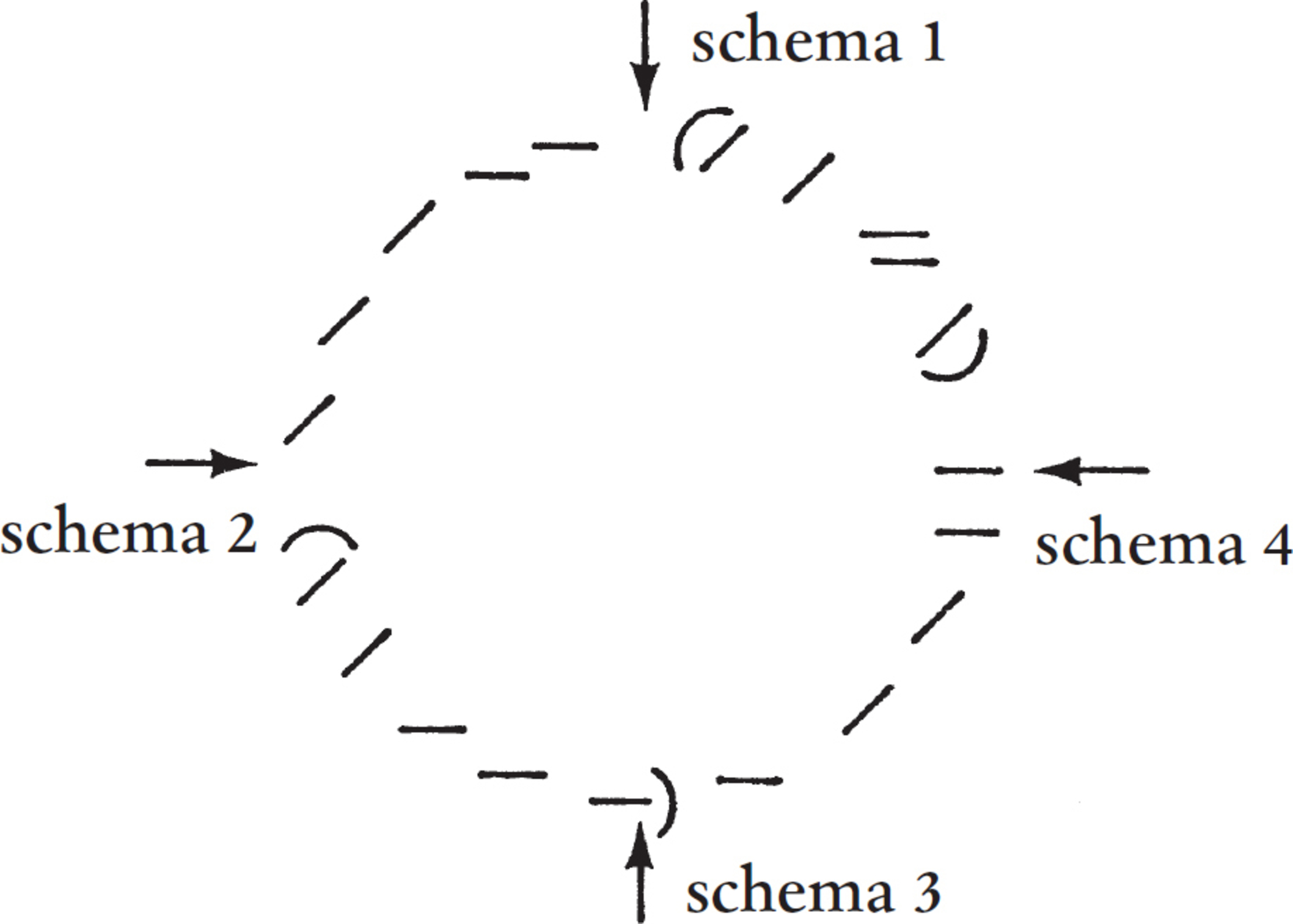

In the Tang period, the art of parallelism was used with extreme refinement. It became a complex game, calling on all the resources of the language: the phonic and the graphic, as well as image and idiom. But, as can be seen from the cited examples, parallelism is more than simply formal repetition. It is a signifying form in which each of the signs elicits its contrary or its complement (its “other”). The ensemble of the signs, through their harmony or through their opposition, draws forward the meaning. From the linguistic point of view, it could be said that parallelism represents an attempt at the spatial organization of signs in their temporal unfolding. In a parallel couplet there is no linear (or logical) progression from one line to the next; the two lines express, without any transition, opposed or complementary ideas. The first line stops, suspended in time: the second comes, not to continue the first but to confirm, from the other end as it were, the affirmation contained in that line, and, finally, to justify its existence. The two lines, responding to each other in this way, form an autonomous gathering in, a self-contained universe. It is a stable universe, subject to the laws of space, but seemingly free of the dominion of time. By symmetrically disposing words belonging to the same paradigm, the poet creates a “complete” language, one in which two orders are present, since the paradigmatic (spatial) dimension has not been erased as the linear and temporal discourse progresses, as is the case in the ordinary language. This two-ordered language (which can be read horizontally and vertically at the same time) can be represented by the following figure:

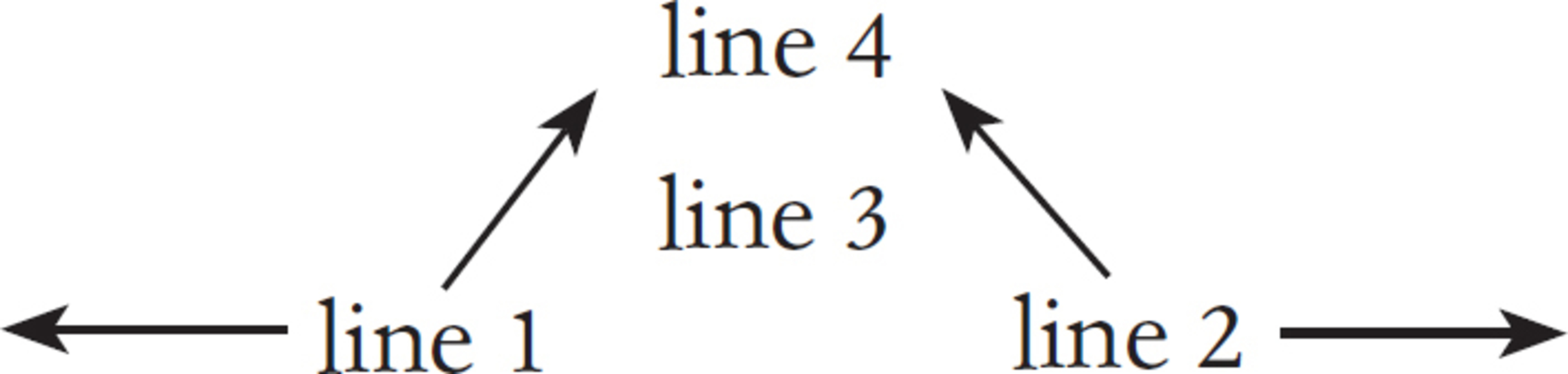

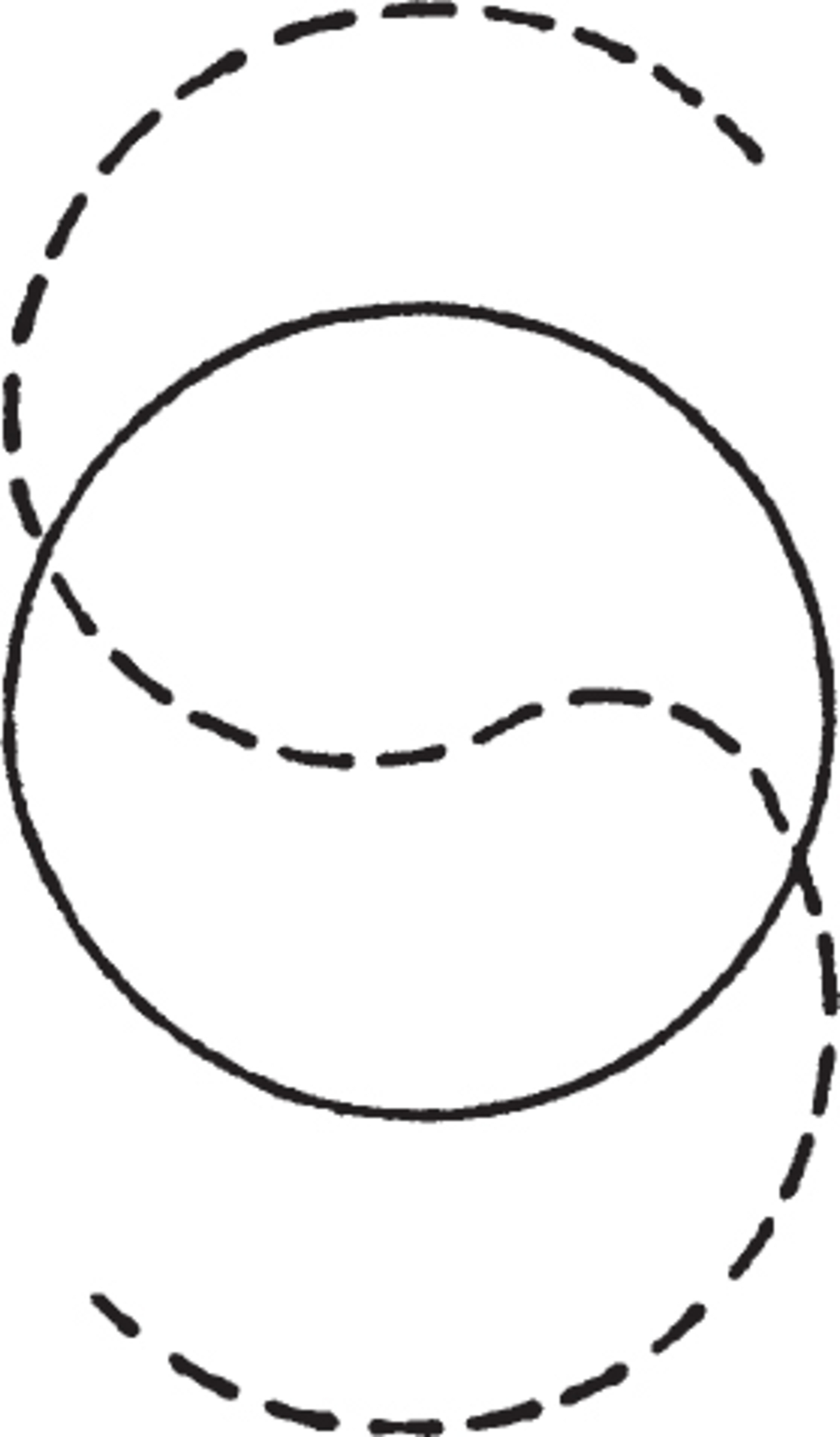

This figure does not completely explain the reality of a system where the two principal constituents follow each other at the same time that they complete each other. This sort of development, concurrently linear and symmetrical, would be better suggested, perhaps, by another figure, one inspired by the traditional Chinese representation of the yin/yang mutation:

Here can be observed a movement that turns upon itself, and yet at the same time opens itself to the infinite. Each element, as it emerges, “returns” and refers to its opposite, the element situated at the other “end” of the figure. It presents a play of pursuit (or pursuit of an Yi always other?) at the same time within and without, in time and beyond it. This spatial structure, founded on a reciprocal justification between the two lines, permits the poet to break, to a certain degree, the linear constraints. In many cases, the obscurity of a line that occurs due to the specific use of words (the use of a noun for a verb, of an empty word for a full word, etc.) or of syntactic anomalies is completely clarified by the presence of the partner line. It is also in the use of parallelism that the most audacious transgressions occur, transgressions whose consequences go beyond the domain of poetry. In the Tang, the explorations of the poets enriched the ordinary language, by upsetting and reordering its syntactic structures.19 Through parallelism, the poet creates a personal universe, one upon which he becomes capable of imposing a different verbal order.20

This personal universe is, however, a universe in the process of becoming. It must be remembered that the lü-shi contains not one but two couplets containing parallel lines, and that these couplets are in turn replaced in a linear context, since they are framed by nonparallel couplets. Thus the parallel couplets, whose structure has just been discussed, do not take their meaning from their own existence alone; this meaning is drawn from a dialectical system founded on a temporality and a spatiality that imply an internal transformation. If parallelism is characterized by its spatial nature, the nonparallel lines, which respect normal syntax, are submitted to temporal law. The composition of the lü-shi is traditionally presented in the following manner: the first and the fourth couplets, the nonparallel, assure the linear development and treat temporal themes; at both ends of the poem, they form discontinuous signifiers. In the center of this linearity the second and third couplets introduce a spatial order. And if the “linearity” is perceived at two times, the “spatiality” is also composed of two steps. Aiming at the bursting of the “normal order of things,” the poet introduces this new dimension by the affirmation (second couplet) of an order in which opposed or complementary facts are placed side by side to form an autonomous ensemble. This order is not static either, however. In the third couplet, also made up of parallel lines, it is reaffirmed, but undergoes a change, as if in following this new order a different relationship between things had been born, a relationship that the poet intends to exploit fully so as best to put to use its dynamic principles. This internal transformation between the two parallel couplets is observable not only on the level of content but also on that of syntax. It is obligatory, in effect, that the two couplets be made of two different syntactic types, and that, furthermore, this difference be founded in derivation, that is, that syntactically the third couplet be derived from the second.

Nonetheless, the very idea of transformation foreshadows the triumph of time, a metamorphosed, an open time. For after the two parallel couplets comes the final couplet, which is obligatorily nonparallel; this reintroduces linear narration into the discourse. The temporal order that inaugurated the poem reclaims its right, here, at the end of the poem. It is as if the poet, always conscious of his power over the language, nonetheless doubts the permanence of the universe of certitude that he has forged. Thus, this affirmation of a semiotic order (by the parallel lines) contains its own negation.

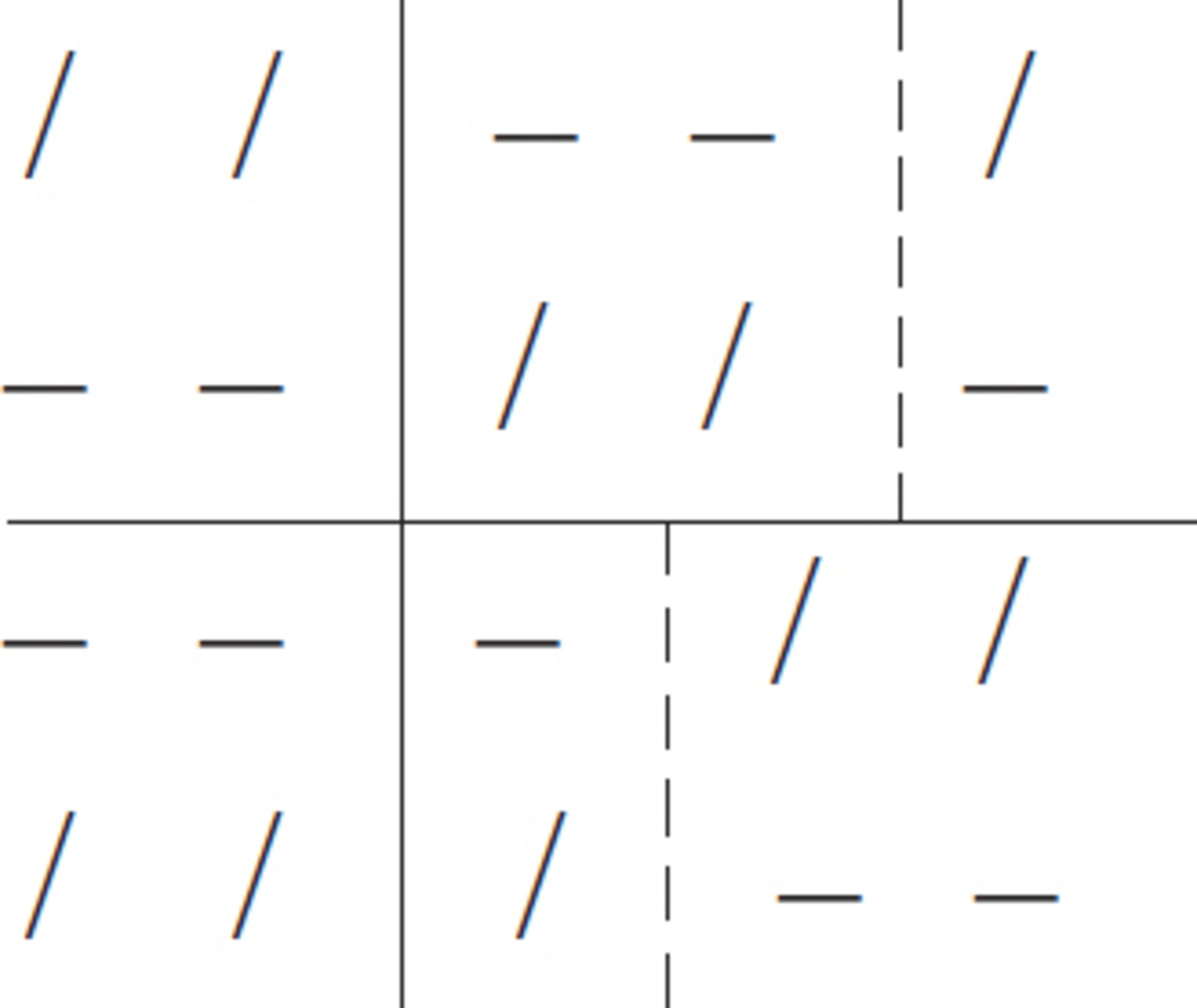

From this perspective the lü-shi is clearly a representation of a dialectical mode of thought. A drama in 4/4 time unfolds before the reader, a drama whose development obeys the dynamic laws of space-time:

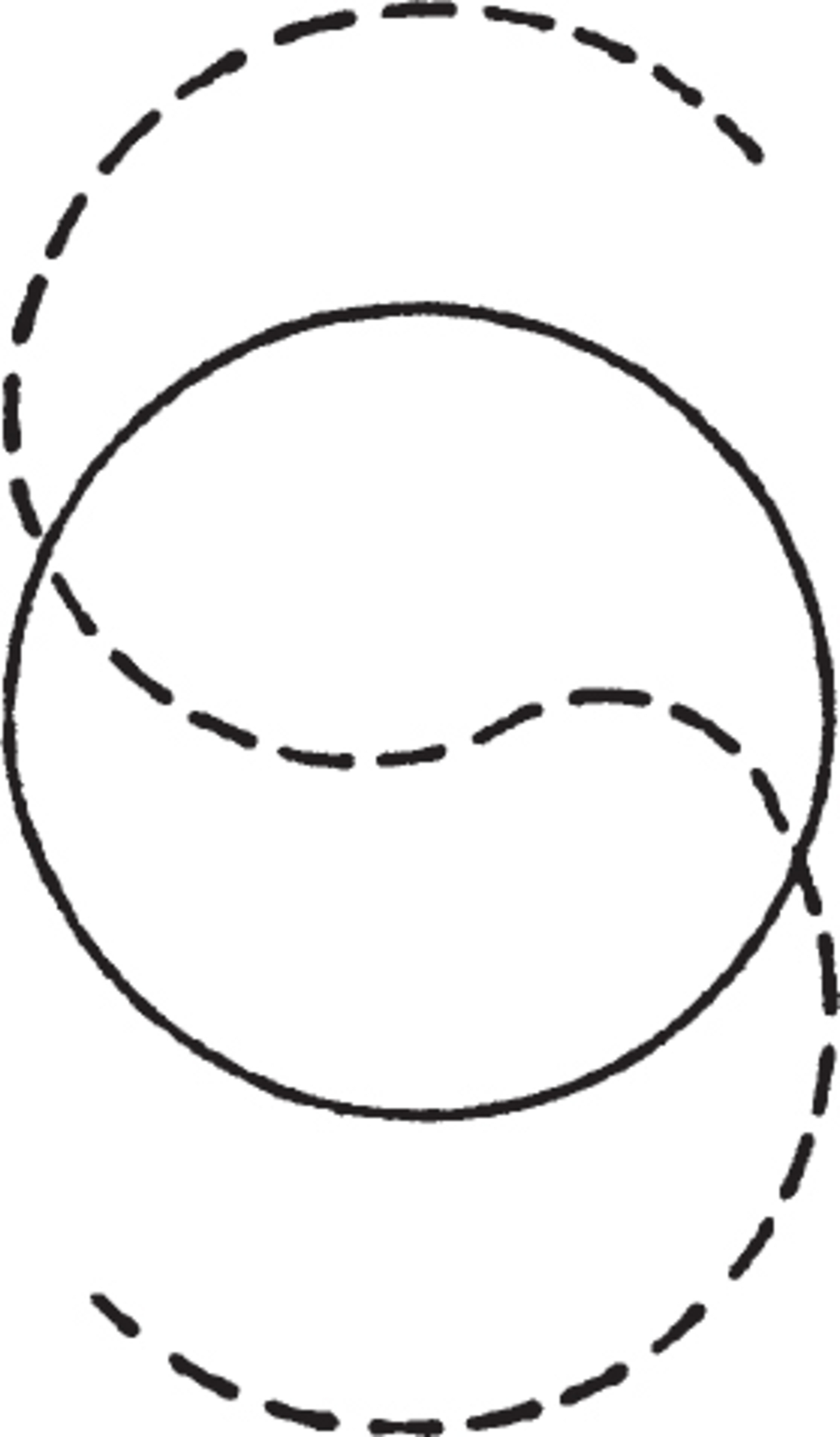

Or, returning to the figure on this page, which represents parallelism as a system turning on itself, it can be said that the system is traversed by a temporal unfolding that prefigures its exploding:

This figure may suggest, in addition, that it is not merely a matter of a linear, but rather of a spiral, development. Beginning from lived time, the poet attempts to go beyond it by establishing a spatial order within which he may rediscover his intimate relationship with things (his desire to “live among his own,” as Claude Lévi-Strauss puts it). And if, in the end, the poet dives back into time, it is an exploded time, a time broken open and assured of further metamorphoses. There are rare examples where, contrary to the rule, the poet ends a lü-shi with a parallel couplet, as if to maintain the spatial order to the end. This occurs in Du Fu’s “On Learning that the Imperial Army Has Retaken He-nan and He-bei.”21 The poem ends with three successive parallel couplets, the last of which, anticipating the return voyage that the poet will make with his loved ones, is intended to prolong the state of euphoria produced by the news.

Examples

Having observed in general terms the implications of the lü-shi form, we shall now analyze two poems in their entirety.

Du Fu: “Evocation of the Past”

Many mountains ten thousand valleys | arrive Jing-men

Be born grow Luminous Lady | there still a village

Once leave Purple Terrace | directly northern desert

Alone dwell Green Tomb | facing yellow dusk

Painted picture not recognize | spring breeze face

Jade amulets in vain return | moonlit night soul

Thousand years pi-pa | filled with barbarous accents

Clear-distinct grief regrets | echo in this song22

This poem evokes the famous story of a lady of the Han court, in the reign of the emperor Yuan-di. This lady is known by her maiden name, Wang Zhao-jun, as well as by her honorific, Ming-fei, “Luminous Lady.” According to the custom of the time, each new lady of the harem was presented to the emperor only through her portrait, which was prepared by the court painter. Wang Zhao-jun, above intrigue, and sure of her beauty, did not deign to bribe the painter, Mao Yan-shou, as did the majority of the court ladies, in order to be sure of a flattering portrait. Because of this failure, she had never been received by the emperor in person. Thus, when the emperor was forced to choose from among his harem to provide a “princess” for a marriage of alliance with a barbarian leader, he chose Zhao-jun, entirely on the basis of her portrait. It was not until the presentation of the “princess” to the barbarian envoy that the emperor saw the Luminous Lady for the first time. He was struck by her dazzling beauty, but despite his desire, was unable to keep her.

What the poet focuses on here, beyond the theme of blocked destiny, is human fragility in the face of a hostile nature, and, through this confrontation, communion with another universe, where regret and fantasy are blended together. The beginning and the end of the poem, the first and fourth couplets, touch on the life of the heroine in its chronological unfolding. The first couplet retraces her life as a young girl in the village of her birth; the last, her posthumous life, a metamorphosed life, perpetuated in time. The linear linking is underlined by the expression “ten thousand valleys” in the first line, echoed by “thousand years” in the penultimate line.

The two middle couplets, made of parallel lines, “fix,” through several outstanding images, the “tragic” events that marked the fate of Ming-fei. These images face each other, thus opposing and changing each other. Nonetheless, there does exist, between the two couplets, a relationship of transformation (static → dynamic).

Both lines of the second couplet begin with verbal forms (“once leave” and “alone dwell”) followed by a preposition (“directly in” and “facing”). This syntactic structure gives a passive tone to the sentences and orients them in a single direction (A → B), reflecting very well the fate of Wang Zhao-jun, a fate determined by forces beyond her own will.

In the third couplet, the verb of each proposition is placed in the middle of the line, thus tying the terms together; the omission of the personal pronoun and of the preposition suppresses any idea of direction. “Painted picture” and “face of springtime wind” (first line of the couplet), as well as “jade amulets” and “soul of lunar light” (second line) are put in an A ⇄ B scheme of equivalence in a relationship of continual coming and going, whence comes the possibility of a double reading:

In the jingling of jade the soul of the Luminous Lady is rediscovered

or

The Luminous Lady makes her jade amulets jingle once more.

As a corollary to the syntactic transformation that takes place between the two parallel couplets, the organization of images also follows a transformational process. There are in the second couplet four colored elements: Purple Terrace (royal palace), northern desert, Green Tomb (according to legend, the tomb of Wang Zhao-jun, though made in the desert, always remained green), and yellow dusk. These color elements oppose each other at the same time that they harmonize, to form a picture that opens onto the third couplet. That couplet in turn quite appropriately begins with the word “picture.” The fateful role played by a painted picture in the life of the heroine is suggested again, but in place of that misleading portrait her life itself is allowed to provide the image for a golden legend. With the help of conventional images (“springtime breeze” = a woman’s face; “jade amulets” = feminine presence; “lunar soul”=the goddess Chang-E, imprisoned on the moon) all constructed from elements of nature, the poet subtly integrates the presence of the Luminous Lady into a universe full of solitary grandeur, where the natural and the supernatural blend together. Thus the past and the present, here and elsewhere, seem to melt together in a dynamic space that refuse to give way to the inexorable course of time.

The last couplet, however, reintroduces the idea of time. Yet, in the final analysis, is it life or is it time that triumphs? The more time passes, the more life changes. Even regret and bitterness are transformed into song (during her lifetime among the barbarians Wang Zhao-jun became an excellent player of the pi-pa, an instrument that originated in Central Asia), and the echoes of her song come down to us here.

Cui Hao: “Pavilion of the Yellow Crane”

The Ancients already riding | Yellow Crane leave

This place keep empty | Yellow Crane Pavilion

Yellow Crane once left | never again return

White clouds thousand years | for-nothing gliding distant-peaceful

Sunlit river clear-distinct | Hanyang trees

Perfumed plant abundant-thick | Isle of Parrots

Setting sun homeland | where then to be found?

Misty waves on the river | to the man infinite sadness23

Pavilion of the Yellow Crane, a famous site, is built upon an elevation dominating the Yang-tze River in the present province of Hu-bei. The pavilion enjoys a panoramic view of the river flowing east toward the sea. This place has always seemed to haunt Chinese poets, and many have written poems there, most notably involving the theme of farewell to a friend going far away. Anecdotes abound, of which one concerns this particular poem. It is said that Li Bai once climbed the pavilion, and was about to compose a poem on the magnificence of the landscape when his eyes fell upon a poem inscribed on the wall. It was, of course, precisely this poem of Cui Hao’s. After reading it he exclaimed, “I can do no better,” and threw away his brush in disappointment. Afterwards, frustrated, Li Bai could not rest until he had written a poem of equal quality in another elevated place. The opportunity presented itself at last in Nan-jing, where he finally wrote a very beautiful lü-shi, he celebrated “Terrace of the Phoenix.”

But, to return to the poem: it is apparent that here the parallelism begins, as the rule allows, from the first couplet; nonetheless it is not complete, either in the first or the second couplet, in the sense that the lines in these two couplets are only parallel before the caesura. The poet seems to want to accent the contrast between the human order and the “beyond.” The incomplete parallelism signifies that the two orders are in an unequal relationship. There is on the one hand a “celestial” order, with its inaccessible splendor (the white clouds), and on the other, the human order, already abandoned by that splendor that once inhabited it. In the first quatrain, made up of two couplets, the image of the Yellow Crane is repeated three times, an even more striking fact when it is remembered that the repetition of words is in principle forbidden in the lü-shi. There is apparent in these three occurrences a sliding of meaning that reflects a theme in transformation: the Yellow Crane is, in these successive manifestations,

(1) A vehicle for attaining the beyond (in accordance with Taoist myth).

(2) An empty name that the human world hangs onto.

(3) A symbol of lost immortality.

The image of the Yellow Crane also evokes the image of the white clouds, contrasting the movement of the bird with the insouciance of the clouds, and contrasting their colors as well. The white clouds themselves are endowed with multiple connotations, among them notably of dream, of separation, and of the vanity of earthly things. The Yellow Crane gone, there remains only an abandoned universe, a world with a piece cut away, where, from this point forward, all desire is revealed to be vain (the word kong, “empty,” “vain,” appears twice in the Chinese, in lines 2 and 4).

Nonetheless, one consolation remains: the present world, a world that dwells in space, a world that the light of the sun still warms. This idea of a form of life that endures despite the contrary forces of time is reflected also on the level of syntax.

Clearly, the third couplet carries on the sentence-type of line 4, while slightly transforming it. The sentence in line 4 may be analyzed as follows:

| theme | complement of time | redoubled qualifiers |

| white clouds | thousand years | peaceful, peaceful |

In lines 5 and 6, the segment before the caesura is constructed from the same sentence-type, without the complement of time:

| theme | redoubled qualifiers |

| sunlit river | distinct, distinct |

| perfumed plant | thick, thick |

This sentence-type, made of a nominal group and a redoubled qualifier (repeated three times in lines 4, 5, and 6), reinforces the idea of a state of things that persists.

As for the segment after the caesura in lines 5 and 6, it is made in both cases of a single nominative form, “trees of Han-yang” and “Isle of Parrots.” The scene is static. The verbal form is omitted where something like “running along the” for line 5 and “growing on” for line 6 might be expected. The living nature that the segment of the line before the caesura depicts seems to end abruptly in a fixed image. Han-yang (a town on the other side of the river) and the Isle of Parrots (in the middle of the river) are place names. Their presence here, as circumstantial as it may appear, is not without its own symbolic nuance, moreover. The yang of Han-yang is the very term that represents one of the principles of the yin-yang pair, the principle of the active life. The name Han-yang means “the yang (or south) side of the river Han” and evokes a world in activity, still in the brilliance of the sun. As for the parrots, one cannot help but relate them to the Yellow Crane of the poem. After the disappearance of the immortal bird, nothing remains in this world but ornamental and imitative birds, birds that are only able to repeat ad infinitum the words they have learned.

Ad infinitum? But here arrives the last couplet, recalling the rule of Time, as announced in the opening of the poem (The Ancients…). It is a time that has never ceased to exercise its power, but that has merely been denied for an instant. The setting sun foreshadows the arrival of the yin principle. From the syntactic point of view,” the sentences return to the “spoken” style, as the expressions “where, then, is it found?” (line 7) and “so as to” (not translated in line 8, after the caesura) confirm. These lines take up again the linear thread of the discourse. It is an open discourse, however. The final interrogative form marks an irrepressible nostalgia. The misty waves, which cover everything again, and confound everything in view, inspire in the poet a feeling of sadness. Yet, at the same time, they give him the illusion of being able to return to the place of his origin.

The gu-ti-shi

It would be easy to end here the analysis of the active process through which the Chinese poet forges his poetic language. Nonetheless, recalling the beginning of the chapter, and the ensemble of forms that were presented, it seems appropriate to present another form here, that of the gu-ti-shi (“ancient-style poem”), a form that is in opposition to the beautiful order of the lü-shi. The gu-ti-shi is in opposition to jin-ti-shi (“modern-style verse,” of which the lü-shi is the principle form), primarily through its absence of constraints, its freer character, and its sometimes more “epic” dimensions. It may be interesting, then, to follow the analyses of the lü-shi with a concrete example of the oldstyle poetry, so as to show both the points of opposition and those of correlation between the two forms as they were practiced in the Tang. The poem under discussion will be, like the first of the lü-shi analyzed, a work by Du Fu. This poet, who is considered by tradition to be the greatest master of the lü-shi, was no less excellent a practitioner of the old style (the other grand masters of this style are Li Bai, Li He, and Bai Ju-yi). With Du Fu specific choices of form had a deep significance. In his youth, the poet lived through the period of great prosperity of the Tang, the period that saw the rise of a whole generation of poets of genius. This period of prosperity came to a brutal halt with the rebellion of An Lu-shan. This revolt, which precipitated China into a terrible tragedy, deeply marked the lives of the poets who were its witnesses or its victims. Du Fu knew in turn the suffering of exodus and of imprisonment by the rebels. It was during the revolt and just afterwards, as Arthur Waley pointed out, that Du Fu composed a series of poems in the ancient style, realistic poems full of vehement emotion in which he describes tragic scenes and denounces the injustices of war. Compared to the lü-shi, which he had composed with an exemplary formal rigor, these poems burst forth, a veritable explosion. The rupture of society is translated here by a rupture of form.

Du Fu: “The Recruiter of Shi-hao”

At night go down to the village of Shi-hao

There have recruiter at night to seize a man

Old man clambers over wall to get away

Old woman comes to front door to answer it

Officer curses—what a temper!

Woman cries—how bitter!

Hear woman move forward to speak

“Three sons for defense of Ye-cheng

One son already come with message

Two sons recently died in combat

The survivor, waiting, tries to live

The dead always stay dead

At home there’s no one any longer

Only a grandson still at breast

For the baby’s sake the woman hasn’t left yet

Go, return without whole skirt

Old woman though weakened with age

Ask to follow recruiter return tonight

Quickly report to the mess at He-yang

Still able to fix breakfast”

Late night voices stop

Like hearing sounds of stifled sobs

Dawn comes climb the highway

To old man only say goodbye24

From a formal point of view, the poem, although written in the ancient style, carries some traces of the modern style. Parallelism is apparent in couplet II, and in the middle of the poem. The effect of the whole, constructed as it is of parallel couplets framed in nonparallel couplets, is to suggest an enlarged, deformed, and, perhaps, burst open lü-shi.

The poem is composed of twelve couplets, with a break, justified by both content and formal reasons, after couplet VI, dividing it nicely into two equal parts. In the first part (couplets I–VI) the old woman offers some opposition to the recruiter, invoking the fact that her three sons have already gone for Ye-cheng, in the defense of the city. To underscore this attempt at resisting a menacing order, the poet uses a series of parallel lines.

The parallelism weakens to a limp by couplet VII. Full parallelism here would require that the lines read: “In the house no longer have anyone / At the breast only have a child.” From this couplet, in effect, the old woman begins an implacable process of “substitution” in the face of the intransigence of the officer. Who shall go in place of whom? If the old man has succeeded in saving himself (since the recruiter supposedly seeks only men), there is in the house besides herself only the daughter-in-law and the grandson. Note, here, the poor ruse in the pleading of the old woman to spare her daughter-in-law: she says first, in couplet VII, that there is no one left in the house except a nursing infant (in Chinese, “beneath the breast”). This she does before even revealing the existence of the mother. And when she does introduce the mother she immediately adds that she is hardly presentable, since she does not even have a whole skirt. In the following couplets (IX and X), the tone of the poem changes and the rhythm accelerates. Personal discourse appears with the presence of the “Yi” (“Old Woman” is used to refer to herself, as in all polite discourse in wen-yan), as the old woman finally decides to offer herself as a substitute for all the others, proposing that she herself go with the officer. From this point on, the action develops inexorably. Couplet X provides a feeble echo of the “limping” parallelism apparent earlier; in this couplet, in fact, the old woman attempts to make herself appear valuable to the recruiter, pleading that she will at least be able to cook for the soldiers. Would the officer really take a woman, and for that matter a very old one? The reader may suppose not, until the last line, when the poet says that the next morning he took leave of the old man alone.

On the narrative level, the poet presents himself as only a listening witness, thus permitting himself to pass over the description of many things. He is no longer a “spectator” participating in the scene, though the speech of the old woman, through which the whole drama is transmitted, does end by blending into that of the poet. The suspense of the poem has a basis in this ambiguity, moreover. In the penultimate line, the reader asks himself whether it is the woman or the poet who mounts to the highway. If the woman has substituted for the others, the poet himself is then substituted for the woman (who has left without having been able to see her old husband again): it is he who says farewell to the old man.