Notes

Introduction

1. The earliest known specimens of Chinese writing are divinatory texts carved on bones and shells. Later inscriptions, cast in bronze vessels, are also extant. Both date from the Shang dynasty (18th to 11th c. B.C.).

2. The Shi Jing (Classic of Poetry, Book of Songs), the collection of songs that inaugurates Chinese literature, contains some works that date from as early as 1000 B.C.

3. It must be made clear from the outset that our presentation is not based solely on etymology. Our point of view is semiological: what we seek to demonstrate are the significant graphic links that exist between the signs.

4. On the manner in which the linguistic signs and their functions are viewed, explicitly or implicitly, within the Chinese rhetorical tradition (a problem that deserves a systematic study of its own, but that is beyond the framework of this study), one should consult, most notably, the Wen Fu (Essay on Literature) of Lu Ji (A.D. 261–303) and the Wen-xin diao-long (Wen-hsin tiao-lung, The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons) of Liu Xie (Liu Hsieh, 465–522). What should be emphasized above all is the affirmation of the place of man in the bosom of the universe. Man, heaven, and earth constitute, for the Chinese, the Three Talents (San Cai); these participate in a relationship of both correspondence and complementarity. The role of man consists not only of “fitting out” the universe, but of interiorizing all things, in re-creating them so as to rediscover his own place within. In this process of “co-creation,” the central element, with regard to literature, is the notion of wen. This term is found in many later combinations signing language, style, literature, civilization, and so forth. Originally it designated the footprints of animals or the veins of wood and stone, the set of harmonious or rhythmic “strokes” by which nature signifies. It is in the image of these natural signs that the linguistic signs were created, and these are similarly called wen. The double nature of wen constitutes an authority through which man may come to understand the mystery of nature, and thereby his own nature. A masterpiece is that which restores the secret relationships between things, and the breath that animates them as well.

5.

![]() .

.

6. The image of the eye is an important one within the Chinese conception of art. We may recall the anecdote of the painter who neglected to draw the eye of the dragon. When asked the reason, he responded, The instant that I add the eye, the dragon will fly away.

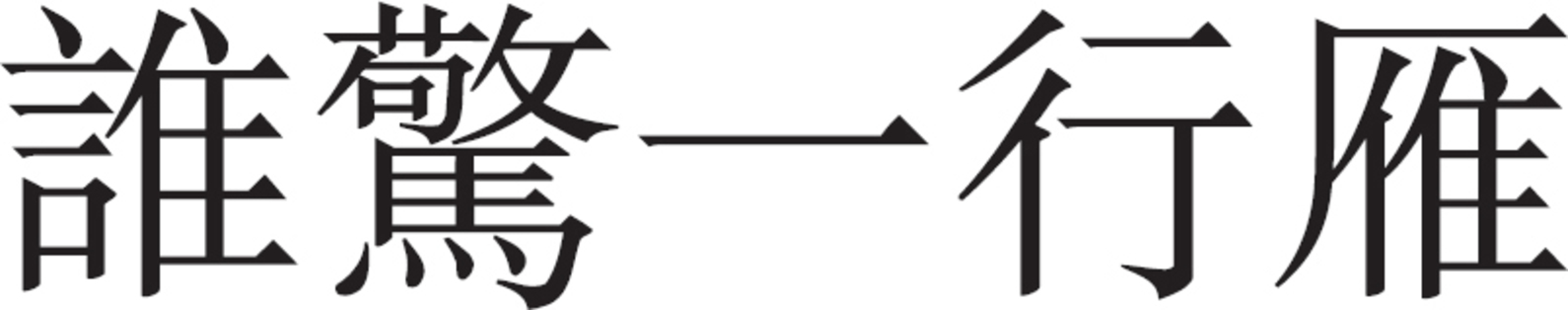

7. In this regard, let us cite, for example, the line of Li He:

![]()

![]() (The brush finishes the creation; heaven doesn’t have all the merit).

(The brush finishes the creation; heaven doesn’t have all the merit).

8. “Xin-yi wu.”

9. See this page for a translation of this poem.

10. “Re san-shou.”

11. “Chun jiang hua yue ye.” See my study of this poem in “Analyse formelle de l’oeuvre poétique d’un auteur des T’ang: Zhang Ruo-xu.”

12. The theory of the unique stroke, which was already contained in the Li-dai ming-hua ji of Zhang Yan-yuan (810–880?), was developed by other painters, notably Shi Tao (1671–1719) in his Hua-yu lu.

13. “Qi-yun.”

14. For literature, see the statement of Cao Pi (187–226), Wen yi Qi wei zhu (“In literature the breath is of primary importance”), in his Tian-lun lun-wen, generally considered the earliest work of Chinese literary criticism. See also the chapter Yang Qi (Nourishing the Breath) in the Wen-xin diao-long of Liu Xie. For painting, we may simply recall the famous expression qi-yun sheng-dong (“animate the rhythmic breath”) of Xie He (ca. 500).

15. More particularly of Taoist philosophy.

16. The tradition of reflecting upon the grammar, founded in the distinction of the xu-zi and the shi-zi, began very early. From the Han dynasty, in the commentaries of the Shi Jing (or, more precisely, on the Mao-zhuan) by Kong An-guo (and Cheng Xuan), one encounters remarks on the specific use of certain xu-zi. For the period of the Six Dynasties and the Tang, we might point out such works as the Guang Ya of Zhang Yi, the Wen-xin diao-long of Liu Xie, the Wen-jing mi-fu of the monk Hai Kong, the Jing-tian shi-wen of Lu De-ming, and the commentaries of Li Shan on the Wen-xuan. From the Song dynasty onwards, there were two types of works which devoted a great deal of space to the problem of the xu-zi: in addition to the shi-hua, there were many works which were primarily lexicographical studies. Among these latter from the Song were the Wen-ze of Chen Kui, the Ci-yuan of Zhang Yan, and the He-lin yu-lu of Luo Da-jing. Lexicographical works of the Ming include the Zi-xue yuan-yuan of Yuan Zi-rang, the Zhu-yu-ci of Lu Yi-wei, and the Zheng-zi-tong of Zhang Zi-lie. Qing works include the Zhu-zi bian-lüe of Liu Qi, the Jing-zhuan shi-ci of Wang Yin-zhi, and the Xu-zi shuo of Yuan Ren-lin. The interested reader can usefully consult the very complete compilation of Zheng Dian and Mai Mei-qiao: Gu han-yu yu-fa-xue hui-bian. One point ought to be underlined here: the definition of xu-zi varies from author to author and from period to period; our analysis is based on a consensus.

17. For the interpretation of the Three from the Taoist perspective, that of the great commentators of different epochs go along the same lines. Thus, following Huai-nan-zi, Wang Chong in his Lun Heng, Wang Bi in his Lao-zi zhu, He Sheng-gong in his Lao-zi zhu, Si-ma Guang, of the Song, in his Dao-de lun-shu yao, Fan Ying-yuan, of the Song, in his Dao-de-jing gu-ben ji-zhu, and Wei Yuan, of the Qing, in his Lao-zi ben-yi.

18. The notion of San Cai (“Three eminent entities”) appears first in the commentaries on the Yi Jing. It will be taken up later, implicitly or explicitly, in the Zhong-yong and the Xun-zi. It will be consecrated under the Han, thanks to Dong Zheng-shu, Liu Xin, and Zheng Xuan.

19. The historical conditions under which this poetry was produced may be presented here in rough outline. After the four centuries of internal division and of constant invasion that followed the collapse of the Han dynasty in A.D. 220, the Tang succeeded in 618 in the reunification of China. Due largely to improved administrative methods, the imperial state was able to impose its authority on the whole of the country. The growth of large cities, the development of communication networks, and the flourishing of commerce all served to a degree to undermine the structure of the ancient feudal society. In addition, the system of recruiting government functionaries through the civil service examination system engendered a greater social mobility. In the cultural domain, the reunification made China more conscious of her identity, while, on the other hand, she opened herself to a great extent to exterior influences, mainly from India and Central Asia. The Tang capital, Chang-an, was a cosmopolitan city where many currents of thought came in contact. It was a society both conscious of order and bubbling with an extraordinary creative effervescence. The pivotal point of dynastic history lies in the years 755 to 763, the period of the so-called An Lu-shan Rebellion. This major event left in its wake millions of dead and fostered abuses and injustices of all sorts. Though it was not officially to end for another 150 years, the Tang was from this point onward to decline. For the poets who lived through this tragic epoch, and for those who came after, confidence gives way to a tragic consciousness. Their attentions focus from this time forward more and more upon social realities and the dramas of life. Their writing is clearly influenced by the transformation of society

20. Thanks to this feverish creation, poetry in China was raised to its greatest status. It became one of the highest expressions of human activity. Not content with being the only product born of the solitude of a poet lost in nature or in the privacy of his study, it exercised, beyond its sacred role, an eminently social function. No marriage, no funeral or celebration would lack poems written for the occasion in calligraphy and posted for all to see. No meeting of educated friends would occur without, to crown the occasion, each of the participants writing a poem with a rhyme scheme agreed upon in common. Engraved stone steles are there to memorialize great deeds; pieces of silk are there to collect martyrs’ last thought expressed in verse…

21. On the difficulty of translating Chinese verse, we can do no better than to cite the reflections of Hervey Saint-Denys (the leading French translator of Chinese poetry): “Literal translation from the Chinese is most often impossible. Many characters may present an entire tableau, a picture that can only be rendered by a paraphrase. Certain characters absolutely demand a whole sentence to be validly translated. One must read a Chinese line, penetrate into the image or the thought that it contains, force oneself to grasp the principal characteristic, and preserve for it its power or its color. The task is perilous; and painful as well, when one perceives real beauties that no European language will be able to retain.

22. Following the May Fourth Movement (1919), the advocates of the “Literary Revolution,” bound in history to the political and social revolutions of the time, called into question not only traditional ideology, but the very instrument of its literary expression as well.

Chapter 1: The Passive Procedures

1. This form will be analyzed in chapter 2.

2.

![]() (743–782?)

(743–782?)

![]()

9.

![]() (“Shu huai”).

(“Shu huai”).

10.

![]() ,

,

![]() (“Xin-an li”).

(“Xin-an li”).

11.

![]() ,

,

![]() (“Song Yang-shan-ren gui Song-shan”).

(“Song Yang-shan-ren gui Song-shan”).

12.

![]() ,

,

![]() (“Pu-sa man”).

(“Pu-sa man”).

13.

![]() ,

,

![]() . It may be interesting here to have a look at the translations that exist for these two lines. The Marquis de Hervey Saint-Denys: “Nul ne sait meme qui je suis, sur cette barque voyageuse / Nul ne sait si cette même June éclaire, au loin, unpavilion où l’on songe a moi.” Charles Budel: “In yonder boat some traveler sails tonight / Beneath the moon which links his thoughts with home.” W. J. B. Fletcher: “To-night who floats upon the tiny skiff? / from what high tower years about upon the night / the dear beloved in the pale moonlight….” In Anthologie de la poésie chinoise classique: “A qui done appartient la petite barque qui vogue en cette nuit? / Où done retrouver la maison clans le clair de June où l’on songe à l’absent?”

. It may be interesting here to have a look at the translations that exist for these two lines. The Marquis de Hervey Saint-Denys: “Nul ne sait meme qui je suis, sur cette barque voyageuse / Nul ne sait si cette même June éclaire, au loin, unpavilion où l’on songe a moi.” Charles Budel: “In yonder boat some traveler sails tonight / Beneath the moon which links his thoughts with home.” W. J. B. Fletcher: “To-night who floats upon the tiny skiff? / from what high tower years about upon the night / the dear beloved in the pale moonlight….” In Anthologie de la poésie chinoise classique: “A qui done appartient la petite barque qui vogue en cette nuit? / Où done retrouver la maison clans le clair de June où l’on songe à l’absent?”

15. H. A. Giles: “Around these hills sweet birds their pleasure take / Man’s heart as free from shadow as this lake.” W. Bynner: “Here birds are alive with mountain-light / And the mind of man touches peace in a pool.” W. J. B. Fletcher: “Hark! the birds rejoicing in the mountain light / Like one’s dim reflection on a pool at night / Lo! the heart is melted wav’ring out the sight.” R. Payne: “The mountain colours have made the birds sing / the shadows in the pool empty the hearts of men. The Marquis de Hervey Saint-Denys: “Dés que la montagne s’ illumine, les oiseaux, tout à la nature, se réveillaient joyeux: / L’oeil contemple des eaux limpides et profondes, comme les pensées de l’homme dont le coeur s’est épuré.”

16. See this page–this page. The following are the extant translations. J. Liu: “The stars drooping, the wild plain is vast / the moon rushing, the great river flows.” W. J. B. Fletcher: “The wide-flung stars overhang all vasty space / the moonbeams with the Yangtzé’s current race.” K. Rexroth: “Stars blossom over the vast desert of waters / Moonlight flows on the surging rivers.”

17. See the analysis of this poem on this page–this page. Also see this page.

19. This term is used by Roman Jakobson in his “Shifters, Verbal Categories and the Russian Verb.”

21.

![]() ,

,

![]() (Du Fu: “Heng-zhou song Li da-fu”).

(Du Fu: “Heng-zhou song Li da-fu”).

24.

![]() ,

,

![]() .

.

25.

![]() ,

,

![]() (Wang Wei: “Song Chiu Wei luo-di gui Jiang-dong”).

(Wang Wei: “Song Chiu Wei luo-di gui Jiang-dong”).

26.

![]() ,

,

![]() (Du Fu: “Xing-ci gu-cheng”).

(Du Fu: “Xing-ci gu-cheng”).

27.

![]() ,

,

![]() (Li Shang-yin: “Feng-yu”).

(Li Shang-yin: “Feng-yu”).

28.

![]() ,

,

![]() (Du Fu: “You gan”).

(Du Fu: “You gan”).

29.

![]() ,

,

![]() (Du Fu: “De she-di xiao-xi”).

(Du Fu: “De she-di xiao-xi”).

Chapter 2: The Active Procedures

1. This is also true of the modern spoken language.

4. Well before Shen Yue (A.D. 441–513) defined the four tones, poets were already instinctively making use of the tonal distinctions.

5. According to the interpretation of Wang Li. See his Han-yu shi-lü xue.

6. We give the tone patterns of the first half of the pentasyllabic lü-shi. The second half is identical.

7. See his article “Le dessin prosodique dans levers régulier chinois.

8. This schema was first proposed by G. B. Downer and A. C. Graham in their article “Tone Patterns in Chinese Poetry.”

9. See chapter 3 for a discussion of the metaphorical imagery, and p.169 for a translation of this poem.

10. This is the first strophe in the poem “Lang-tao-sha.” The following translation appears in Anthologie de la poésie chinoise classique: “Derriére les rideaux, la pluie sans fin clapote. La vertu du printemps s’épuise. Sous la housse de soie, l’intolérable froid de la cinquiéme vielle! Quand je rêve, j’oublie que je suis en exil. Doux réconfort tant attendu!”

11. Drawn from the poem “Ting Ying-shi tan qin.”

12. “Sheng-sheng man.”

14. See this page–this page and this page. The sign | marks the caesura.

17.

![]() ,

,

![]() (Han-jiang lin fan).

(Han-jiang lin fan).

18. From the Pavilion of the Storks, by Wang Zhi-huan. See this page.

19. Wang Li treats this problem at length in his Han-yu shi-kao.

20. We cannot linger at length over the syntactic transgressions permitted by parallelism without breaking the thread of our presentation of the form of the lü-shi. The reader familiar with Chinese can with great benefit consult Wang Li’s Han-yu shi-lü xue. We will attempt here only a brief summary of the researches of the Tang poets in the three areas, those of perceptive, inverted, and decomposed verbal order:

(1) Perceptive Order: In this type, the poet organizes words not according to the habitual syntax, but in a sequence that attempts to be the reflection oí his successive perceptions (of a landscape, of a sensation, etc.). The following lines show us the poet Du Shen-yan traveling, at dawn, south of the Yang-tze near its mouth. The word order suggests the images that the poet receives as he moves along, images of the dawn’s birth and of the plants whose changing colors mark the changing of the seasons, on either side of the river:

Clouds light appear sea dawn

![]()

Plumtrees willows cross river spring

![]()

Sometimes the poet chooses to begin his line with an outstanding image, all unannounced. That image may be a scene, a color, a taste; it is one chosen for its power to “release” a series of sensations and memories, a series that is as if born from the image itself. The following images are all drawn from the poems of Du Fu:

(a) Temple remember long ago visit place

![]()

Bridge love once again cross moment

![]()

(b) Green regret mountains and hillsides pass

![]()

Yellow foresee orange trees approach

![]()

(c) Softness savor rice with “braided” mushrooms

![]()

Fragrance smell soup with crocheted” herbs

![]()

In other cases, what the poet seeks is not a succession of images, but a fixed state:

In these two lines, the elements outside the enclosure constitute discontinuous signifiers. Between them the poet inserts the images of the threshold and the gables to mark visually the intrusion of human presence into nature (or conversely, the invasion of the human sphere by nature). Through this arrangement of the words, the poet re-creates a scene exactly as it offers itself to his view

(2) Inverted Order: Here the order consists simply of inverting the subject and object of the sentence. Yet it is more than a simple refinement of an effect of style. The procedure represents a desire to disrupt not simply the order of the language, but the world itself, in order to create a different rapport between things.

Fragrant rice peck finish parrot grains

![]()

Green plane tree perch aged phoenix branches

![]()

Reading this famous couplet by Du Fu, the reader immediately understands that it is not the rice that pecks the parrot, nor the plan tree perching on the phoenix. It must be emphasized that it is only in parallel lines that the poet dares to create this sort of distortion; the mutual justification between the lines clearly disposes of whatever may appear “fortuitous” or “arbitrary” in the syntax.

Sick traveler keep because of medicines

![]()

Late spring buy because of flowers

![]()

These lines, in fact, mean: “I keep medicinal herbs in my exile, being often sick / I buy flowers as if to hold the passing spring. The inversion of subject and object lends a nuance of disenchantment tinted with humor.

For a long time regret river-lake return white hair

![]()

Always wander heaven-earth penetrate light-boat

![]()

Here the inversion permits the poet, Li Shang-yin, to present forcefully the action of the exterior world upon the man; without it, the reader would be left with the rather common image of the white hairs scattering, and the light boat lost.

(3) Decomposed Order: In this order, the poet mixes cause and effect, organizing the words in an apparently arbitrary manner, attempting to create a “total” image, where all of the elements mix together, and a “privileged point” no longer exists. This is a dynamic sentence where the sign finds itself in a network ceaselessly in transformation, and in which, following each change, it takes on a new meaning, as in the following:

Terrain penetrate mountain shadow sweep

![]()

Leaves mark dew traces inscribe

![]()

To find a graspable meaning for these lines by Jia Dao, it is necessary to perform a chain transformation on the first line:

Terrain penetrate mountain shadow sweep →

Penetrate mountain shadow sweep terrain →

Mountain shadow sweep terrain penetrate →

Shadow sweep terrain penetrate mountain →

Sweep terrain penetrate mountain shadow →

The last sentence has a normal reading, and informs us about what the poet wishes to say: in the sweeping terrain in front of his house, he penetrates the shadow that the mountain casts. If the second line is submitted to the same transformation, the following line is obtained:

Inscribe leaves, mark dew traces

The poet makes his inscription upon some leaves (probably the broad leaves of the banana tree) that are marked with dewdrops.

In the same spirit, to describe a landscape where tender bamboo shoots, with green leaves hanging, are broken by the wind, and where plum blossoms drenched with rain open their pink petals (notice the erotic connotation of the scene), Du Fu changes the natural order of the words to remove any notion of anteriority or posteriority, thus producing an instantaneous and total view:

Green hang wind broken bamboo

![]()

Red burst rain open plum

![]()

21. See this page, and this page–this page above.

Chapter 3: The Images

1. This translation does not bring across the richness that this simple yet justly famous couplet contains. In effect, the verb jian…which is found in the middle of the second line, signifies both “to appear” and “to see,” so that, in the absence of the personal pronoun, the line lends itself to a double interpretation: “South Mountain appears without care,” or: “without care, I see South Mountain.” As the mountain in question is known for its mists, behind which it hides its mysterious beauty most of the time, in this line the poet restores the magic moment when, because of the dissipated mists, he surprises the presence of the mountain, at the same time as it “offers itself to his view.” This coincidence of the man’s gaze and the thing that comes into his sight is the very definition of Chan (“Zen”) revelation.

2. The interested reader can consult the more extended article that we have devoted to the two figures in the Cahiers de linguistique—Asie orientale n. 6 (EHESS-CRLAO).

3. Ten characters (“Zi jing fu Feng-xian yong-huai wu-bai zi”). In these two lines, the images of the “Red door” and of “wine-meat” may be considered to be synecdoches, while that of “paths or routes” is there to be assimilated into a metonymy. But let us make clear, once more, that our concern here is not classificatory

4. See second part, this page.

7. There is a translation of this long poem in the Anthologie de la poesie chinoise classique.

9.

![]() ,

,

![]() .

.

11.

![]() ,

,

![]() (“Jiang lou”).

(“Jiang lou”).

13. Metonymy brings together very varied facts, including, for example, those of “linked metaphors.” But in general, one should envisage these facts in terms of channels or networks.

16.

![]() “Bottomless sea field of mulberry trees, signifying that the sea can one day be transformed into a cultivated field and vice versa.

“Bottomless sea field of mulberry trees, signifying that the sea can one day be transformed into a cultivated field and vice versa.

17. One should not assume from our analysis that the poem is no more than an aggregate of images. This is a song where the absence of emotionally expressive words only makes it that much more poignant. To a Chinese ear, the lines are no less musical than Ariel’s song from Shakespeare: “Full fathom five thy father lies / of his bones are coral made / Those are pearls that were his eyes / Nothing of him that doth fade / But doth suffer a sea-change / Into something rich and strange,” nor less “spoken” than the plaints of Maurice Scève: “In you I live, even though you’re gone, / In me I die, even though I’m here. / You are so far, you are always near, / As close as I am, I have still withdrawn.” (English translation by Don Riggs)