Gu-ti-shi

(Ancient-style Poetry)

LI BAI

Drinking Alone under the Moon

Among the flowers, a jug of wine.

Drinking alone, no companion.

Raise the cup, invite bright moon.

And my shadow, that makes three.

The moon knows nothing of drinking.

My shadow merely follows me.

I will go with moon and shadow,

Joyful, till spring end.

I sing, the moon dances.

I dance, my shadow tumbles.

Sober, we share our joy.

Drunk, each goes his way.

Forever bound, to ramble free,

To meet again, in the Milky Way.

See this page. Recalling the legend according to which Li Bai drowned while attempting to drink the moon from a lake, we cite the following song of the poet:

White apes in the autumn,

Dancing, light as snow.

In a single bound, into the branches,

Drinking, from the water, the moon.

LI BAI

Ancient Air

Climbed high, to gaze upon the sea,

Heaven and Earth, so vast, so vast.

Frost clothes all things in Autumn,

Winds waft, the broad wastes cold.

Glory, splendor; eastward flowing stream,

This world’s affairs, just waves.

White sun covered, its dying rays,

The floating clouds, no resting place.

In lofty Wu-tong trees nest lowly finches.

Down among the thorny brush the Phoenix perches.

All that’s left, to go home again,

Hand on my sword I sing, “The Going’s Hard.”

Lines 9 and 10: Injustice reigns in the world; the mediocre occupy high position, while better men live in their shadows.

LI BAI

A Song of Bathing

If it’s perfumed, don’t brush your cap

Fragrant of orchid, don’t shake your gown.

This world hates a thing too pure.

Those who know will hide their light.

At Cang-lang dwells a fisherman:

“You and I, let us go home together.”

Lines 1 and 2: “Brush cap” and “shake gown” are conventional metaphors for the taking up of official position.

Line 5: The figure of the fisherman often represents detachment and purity preserved. The allusion here is to the famous encounter between Qu Yuan (the great poet of the Warring States period) and a fisherman. Qu Yuan, going by the riverside, explains the reason for his exile to the fisherman: “All the world is corrupt, I would stay pure; all the world is drunk, I would stay sober.” The fisherman, before going off, sings, “When the water is clear, I wash my hat strings; when the water is muddy, I wash my feet.”

LI BAI

A Farewell Banquet for My Uncle, The Revisor Yun, at the Pavilion of Xie Tiao

It’s broken faith and gone, has yesterday; I couldn’t keep it.

Tormenting me, my heart, today, too full of sorrow.

High wind sees off the autumn’s geese, ten thousand li.

Facing this it’s meet to drink upon the high pavilion.

Immortal letters, bones of Jian’an.

Here Xie Tiao is clearly heard again.

All embracing, his thoughts fly free,

Mount to blue heaven, caress the bright moon.

Grasp the sword and strike the water, still the water, flows.

Raise the cup to drown your grief, grief only grows.

Life in this world: few satisfactions.

In the dawning, hair unbound, to float free in the skiff.

The poet Xie Tiao (fifth century) built the pavilion when he was governor of Xuan-zhou at An-hui.

Line 3: autumn’s geese = symbol of distance and separation.

Line 5: The era Jian-an (A.D. 196–219), during the late Han, was one of the most fecund periods of Chinese poetry.

LI BAI

Ancient Air

Westward over Lotus Mountain

Afar, far off: Bright Star!

Magnolia blooms in her white hand,

With airy step she climbs Great Purity.

Rainbow robes, trailing a broad sash,

Floating she brushes the heavenly stairs,

And invites me to mount the Cloud Terrace,

There to salute the immortal Wei Shu-qing.

Ravished, mad, I go with her,

Upon a swan to reach the Purple Vault.

There I looked down, on Luo-yang’s waters:

Vast sea of barbarian soldiers marching,

Fresh blood spattered on the grasses of the wilds.

Wolves, with men’s hats on their heads.

Li Bai wrote a number of poems on the theme of long rambles in dreams (in Taoist holy places), the most famous of which is “A Farewell on the Mountain of the Heavenly Mother.”

Lines 12–14: despite his attempt at evasion, the poet cannot forget the world, ravaged by war, where tyranny reigns.

LI BAI

Ballad of Chang-gan

My hair barely covered my forehead then.

My play was plucking flowers by the gate.

You would come on your bamboo horse,

Riding circles round my bench, and pitching green plums.

Growing up together here, in Chang-gan.

Two little ones; no thought of what would come.

At fourteen I became your wife,

Blushing and timid, unable to smile,

Bowing my head, face to dark wall.

You called a thousand times, without one answer.

At fifteen I made up my face,

And swore that our dust and ashes should be one,

To keep faith like “the Man at the Pillar.”

How could I have known I’d climb the Watch Tower?

For when I was sixteen you journeyed far,

To Qu-tang Gorge, by Yan-yu Rocks.

In the fifth month, there is no way through.

There the apes call, mournful to the heavens.

By the gate, the footprints that you left,

Each one greens with moss,

So deep I cannot sweep them.

The falling leaves, the autumn’s wind is early,

October’s butterflies already come,

In pairs to fly above the western garden’s grass.

Wounding the heart of the wife who waits,

Sitting in sadness, bright face growing old.

Sooner or later, you’ll come down from Sanba,

Send me a letter, let me know.

I’ll come out to welcome you, no matter how far,

All the way to Long Wind Sands.

Chang-gan is located in Jiang-su province near Nan-jing.

Line 13: the Man at the Pillar = a legendary personage who awaited his beloved in vain beneath a bridge, preferring to die in the rising water rather than to leave the place of their appointed meeting.

Line 14: Watch Tower = one of the many mountains in China that bear this name, in memory of an abandoned woman who climbed each day to the mountain top to keep vigil for her husband’s return.

Last line: Long Wind Sands, on the riverside many days from Chang-gan. The Blue River is navigable from Jiangsu upstream to Si-chuan. All along the river are ports that favor the trade of the river merchants. Tang poetry often deals with the travels of these merchants and the fate of their wives, often left for long months. See on the same theme the quatrain by Li Yi, “Song of South of the River,” this page.

LI BAI

Ancient Air

Moon’s tint, it can’t be swept away;

The traveler’s grief, no way to say it.

White dew proclaims on Autumn robes;

Fireflies flit above the grasses.

Sun and moon are in the end extinguished;

Heaven and Earth, the same, will rot away.

Cricket cries in the green pine tree;

He’ll never see this tree grow old.

Potions of long life can only fool the vulgar;

The blind find all discernment hard.

You’ll never live to be a thousand,

Much anguish leads to early death.

Drink deep, and dwell within the cup.

Conceal yourself, your only treasure.

DU FU

Lament on Chen-tao

First month of winter, ten counties’ gentle youths’

Blood serves for water in the Chen-tao swamps.

Broad wilds, clear skies, no sounds of battle.

Forty thousand volunteers, in one day, dead.

The Tartar returns, arrows bathed in blood,

Still singing his barbarous songs as he drinks in the market.

The people turn away, stand weeping, facing north,

Day and night their hope, the army may return.

At Chen-tao, in 756, during the rebellion of An Lu-shan, the Chinese army was disastrously defeated.

DU FU

Dreaming of Li Bai

Parted by death, I swallow my sobs.

Parted in life, I sorrow incessant.

South of the River, that pestilential place,

The wanderer’s gone, and no word comes.

Old friend, you come into my dreams,

As if you knew how I longed to see you,

But I can only fear it means you’re dead:

Could your living soul have come so far?

Your spirit came, the grove of maples greened.

Your spirit left, the high cold pass grew dark.

But you’re caught in their net now;

How could you fly free?

Falling moon fills the room to the beams,

And almost lets me glimpse your shining face.

The waters deep, the waves, spread out.

Don’t let the dragon get you.

Du Fu and Li Bai are known to have associated during two periods, during which they established a deep friendship. In 757 (or 758), during the An Lu-shan Rebellion, Li Bai, implicated in the affair of Prince Lin, was condemned to death. The sentence was commuted to banishment in Yun-nan in the malarial south of China. Du Fu, at the time of the poem living in Si-chuan, feared for the life of his friend. This poem is among the ten or so poems in which Du Fu expresses not only his friendship and admiration for Li Bai, but moreover his sadness and anger at the world’s treatment of genius, and the demons of jealousy that await the fall of the valorous man.

Lines 13 and 14: Du Fu, awakened from his dream, sees the silhouette of his friend once more, lit by the moon.

DU FU

Peng-ya

I recall, when we first fled the Tartars,

We went north, and the way was hard.

Deep in the night on the road to Peng-ya,

Moon shone on the White Water hills.

The whole family long on foot,

And when we met someone, always shamefaced.

Here and there birds crying in the gullies,

Never a soul coming the other way.

My little daughter in her hunger took a bite of me.

Afraid her cries would bring on wolves and tigers,

I’d closed her mouth against my chest,

But she only cried the louder.

My little son tried hard to understand,

Collected bitter plums, to eat.

Ten days, half thunderstorm,

Through the mud, linked hand in hand,

With no rain gear at all.

The path slick, our clothing freezing.

Sometimes, as hard as we tried,

In a whole day, two miles at most.

Wild fruits for our hunger,

Low boughs, our shelter’s beams.

Morning trudging through the rocky creeks,

Evening searching the sky for some hut’s smoke.

We rested awhile at Zhou-jia Valley,

Before the march through Lu-zi Pass,

With my old friend Sun Zai,

His bounty reaching to the clouds.

When we came, already dusk,

They lit the lamps, threw wide the double gates.

They brought warm water, bathed our feet,

Hung out bright banners, to call our spirits back.

He called his wife and children out:

They gazed on us; tears brimmed their eyes.

My whole brood was fast asleep.

Roused, they were favored with a plate of provender.

“We’ll swear an oath, you and I,

Forever to be brothers.”

And the hall where we sat was prepared for our stay,

That we might dwell secure, and at our ease.

Who else would dare, in these hard times,

To open his heart, and his arms, to us?

Since we left, a year has passed.

The Tartars still plot turmoils.

How I wish that we had wings,

To fly, to alight, before you.

Poem written in 757.

DU FU

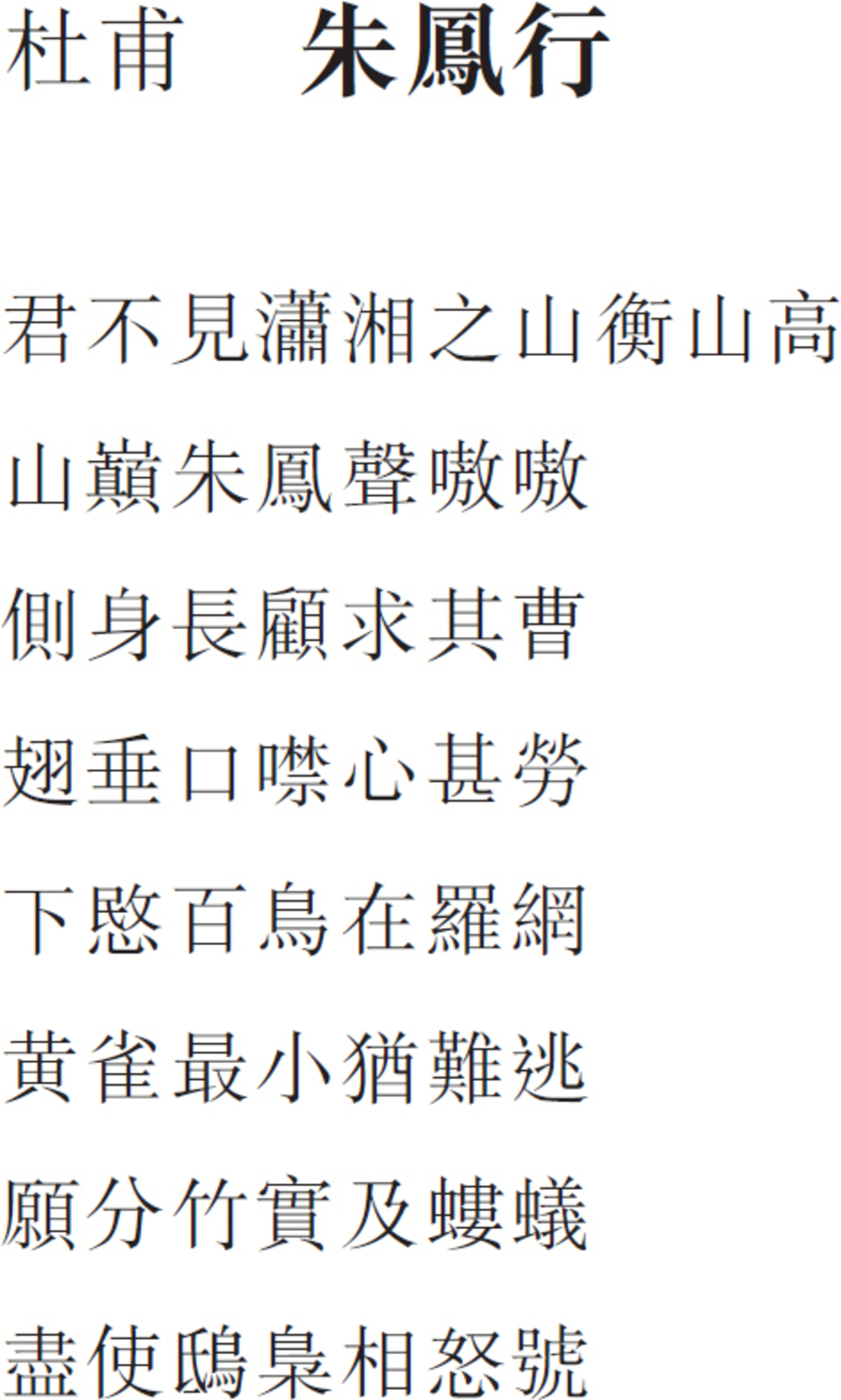

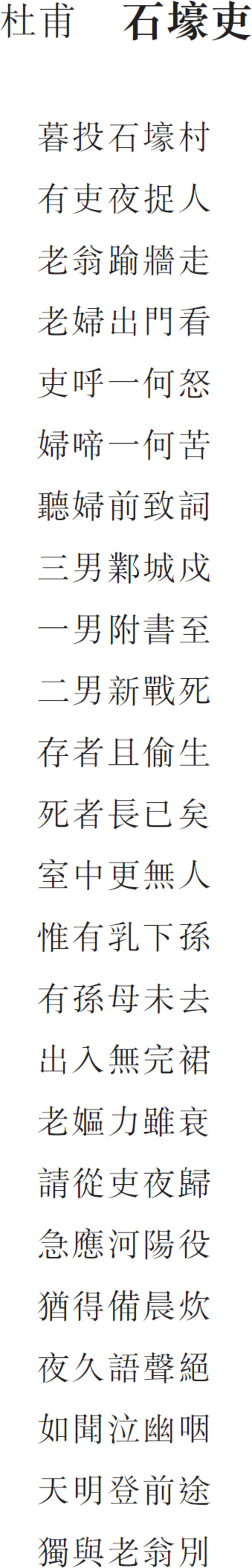

Red Phoenix

Don’t you see?

Of all the hills in Xiang, Mount Heng’s the highest,

And at its peak, Red Phoenix cries.

He twists and he cranes as eyes seek for his peers,

Then his wings droop in the silence of his weary heart.

Gazing down he sees that all the birds are caught in one great net,

Nor even the tiniest sparrow can squeeze through the mesh.

This bird would share his food, if only with the ants.

Let it make the owls to hoot with anger, if it will.

Du Fu is haunted by the phoenix, a legendary bird charged with religious significance. In along poem entitled “Terrace of the Phoenix” he compares himself to this bird, which, through the offering of its own flesh and blood, would seek to comfort the suffering of the world:

I would open my heart, and let the blood flow,

Giving food and drink to the neglected.

My heart, become the bamboo fruit, which satisfies.

No need to look for other food.

My blood, a fountain of thirst-quenching wine,

Better than these springs by which I flee….

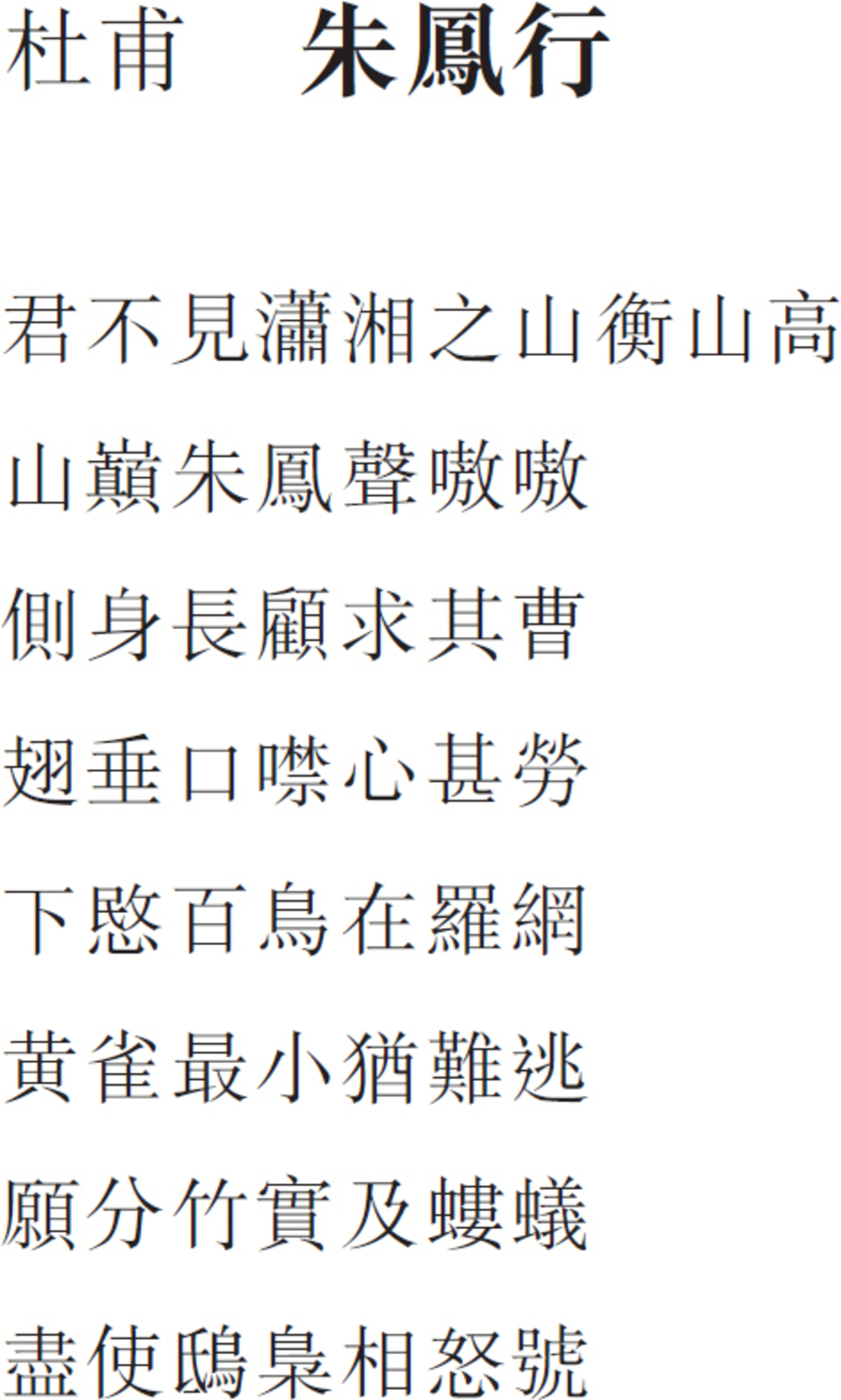

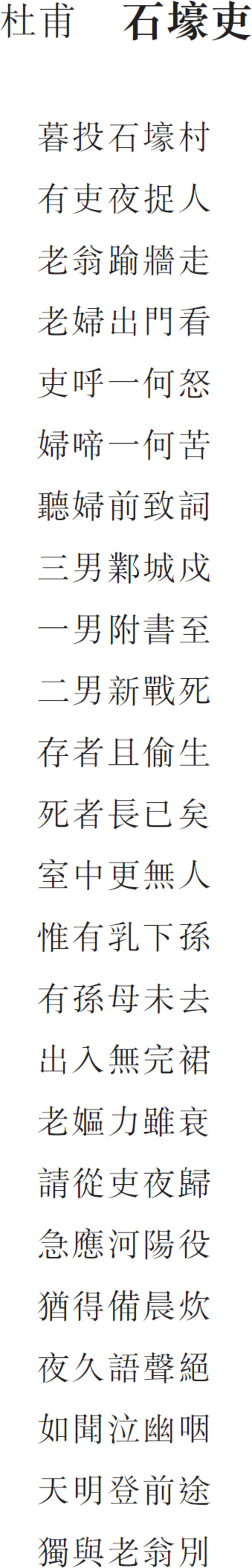

DU FU

The Pressgang at Shi-hao Village

Evening, I found lodging at Shi-hao.

That night a pressgang came for men.

An old man jumped the wall,

While his old wife went through the gate to meet them.

The officer cursed, so full of anger.

The old woman cried, so bitter.

Then I heard her approach him and speak:

“Our three sons went off in defense of Ye-cheng.

Now one has sent a letter home,

To tell us that the other two are slain.

He who remains yet clings to life.

They who have gone are dead forever.

At home here there is no one else…

But a grandson at the breast,

And his mother, not yet able to leave him.

And anyway, she’s not a whole skirt to put on…

This old one, though her strength is ebbing,

Begs you, sir, to let her come tonight,

To answer the draft for Heyang.

“I might still help to cook the morning meal.”

Night lengthened, the voices died away,

Owindling to a sound like stifled sobs.

The sky brightened, I climbed back toward the path.

Alone, the old man made farewells.

This poem is analyzed on this page–this page, to illustrate the difference between the gu-ti-shi (ancient-style poetry) and the lü-shi (regulated verse).

DU FU

On Seeing the Sword Dance Performed by a Disciple of Madam Gong-sun

Long ago there was a beauty, Gong-sun her name.

In a single gesture of her sword dance all the world was overthrown.

The watchers, massed in mountains, their color paled away,

And heaven and earth bowed long before her.

Bending back, the bow of Great Yi’s shot, and nine suns falling.

Rising up, a heavenly being, aloft, on dragons soaring.

Approaching: she is lightning, thunder; holds the harvest of storm’s fury

Staying: rivers and oceans, congealed, as clear light.

Deep red lips and pearl-sewn sleeves are quiet.

Late now, from one disciple only does such fragrance come.

The lady of Lin-ying at White Emperor Town,

The fair dance to the old song, and the spirits soaring.

And when I asked and found whence came such art,

I pondered time, and change, and grew still sadder.

Minghuang’s waiting maids; eight thousand,

And Madam Gongsun’s sword dance stood premier.

Now fifty years, a single simple gesture of the palm,

Dust in the wind, quicksilver, dusk, our Royal House.

The Pear Garden’s pupils, like the mist they all are scattered;

This lady’s fading beauty brightens, the cold sun.

South of Gold Grain Hill, the trees: grown to full hand’s span.

Here in Qu-tang Gorge, the grasses wither.

The feasts, the pipes; songs end again.

The utmost joy, then sadness comes; moon rises, east.

The old man can’t know where he’s to go,

Feet sore, wild hills, turning, deep in sorrow.

(Note for this page–this page) This poem bears a preface in which the poet relates the circumstances that inspired him to write it. In 767, at Kui-zhou in Si-chuan, Du Fu was present at a sword dance performed by Li shi-er niang, of Lin-ying. Having learned from her that she was a disciple of the great Madam Gong-sun, he remembered that while still a child (in 717), he had had the rare pleasure of admiring the performance of the celebrated dancer himself. Through the destiny of Gong-sun (linked with the fate of the dynasty), he rediscovers his own. The last image of the poem, the old man hobbling alone on the mountain, contrasts ironically with the dazzling dance described at the beginning.

In the same preface, the poet remarks that the great calligrapher Zhang Xu (675–750) discovered the secret of his art inspired by the dancing of Gong-sun; he does this to show the fascination that the dancer held for her contemporaries and also to suggest the important idea in Chinese aesthetics of the correspondences among the arts.

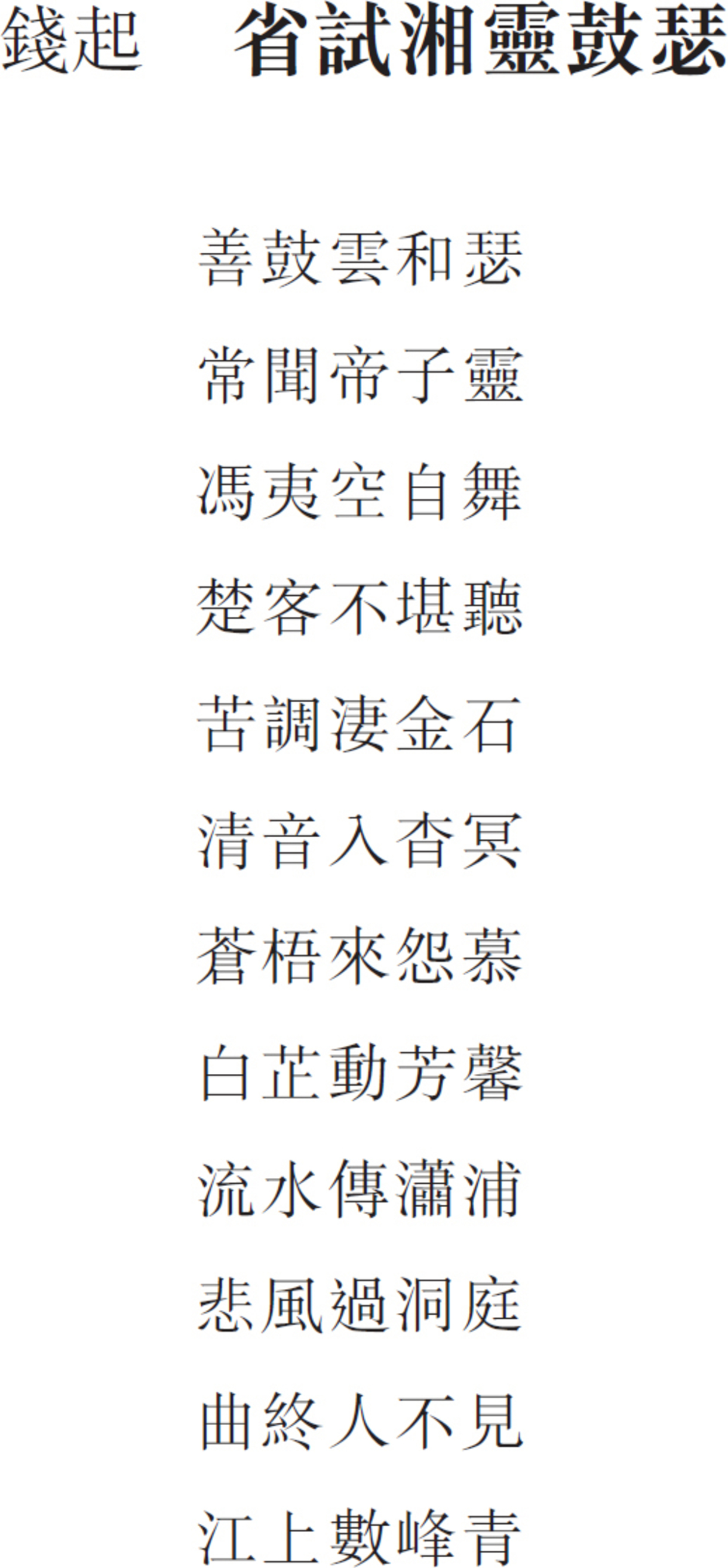

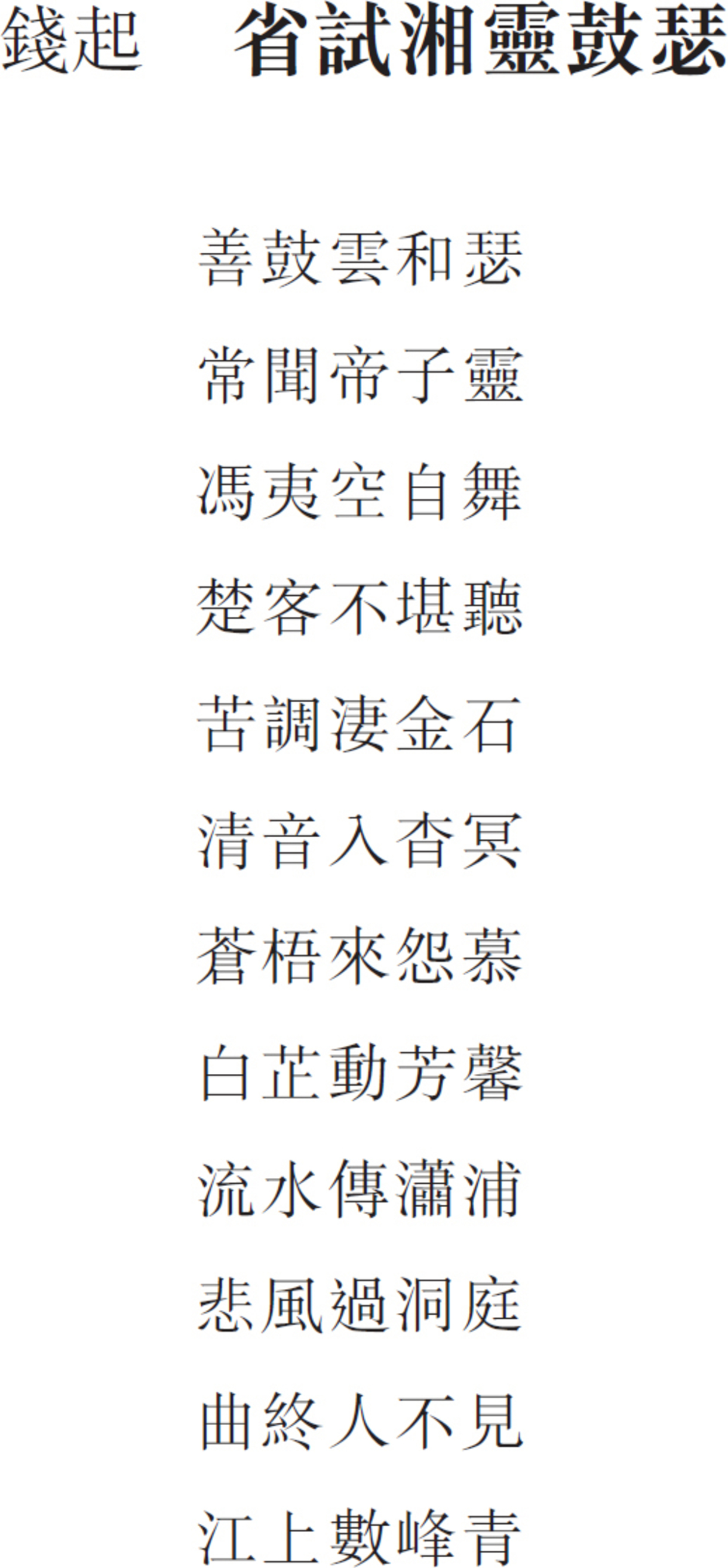

QIAN QI

Gazing from High on the Mountain on the Rainy Sea and Thinking of the Monks in the Yu-lin Monastery

From the mountain, rain upon the sea,

Dripping foam from the misty trees.

It looks as if, in that vastness,

Those dark isles might any moment fly away.

Nature has angered the eight-headed spirit of the sea.

The rushing tides stir up the road of the clouds.

The true men ever fill my thoughts,

But a single reed can’t float across.

Sad thoughts of the times at Red Cliff

Wishing I could harness the wild swans, and drive.

QIAN QI

The Master of Xiang Plays His Lute

So well he plays his cloud topped lute,

We hear the Lady of the River.

The god of the stream is moved to dance in emptiness.

The traveler of Chu can’t bear to listen.

A bitter tune, to chill both gold and stone.

Pure notes pierce gloomy dark.

Deep green Wu-tong brings sad thoughts on.

White iris there, recalls a certain fragrance.

The waters flow, between Xiang’s banks.

Mournful winds cross Lake Dong-ting.

Song done, and no one to be seen.

On the river, many peaks, all green.

This poem bears comparison to the myth of Orpheus. The rhythm of the song orders all nature, and death itself is vanquished, for, if the musician himself has disappeared, his song continues to resound, forever ineffable.

Line 2: the Lady of the River = At the death of the legendary Shun, one of his wives threw herself into the River Xiang, and became the goddess of its waters.

BAI JU-YI

The Charcoal Man

Old charcoal man

Cuts wood and seasons coals up on South Mountain.

Face full of ashes, the color of smoke,

Hair white at the temples, ten fingers black,

Sells charcoal, gets money, and where does it go?

For the clothes on his body, the food that he eats.

Yet sadly though those clothes are thin,

He worries for the price of charcoal, prays the weather cold.

This night, upon the city wall, a foot of snow.

Dawn, he loads his cart, tracks over ice.

The ox tired, the man hungry, the sun already high,

South of the market, outside the gate, in the mud, they rest.

So elegant these prancing horsemen, who are they?

Yellow-robed official, white-robed boy.

Hand holds a written order, mouth spouts “The Emperor.”

They turn the cart, they curse the ox, head north.

A thousand pounds of charcoal in that cart

And if they commandeer, can he complain?

Half a piece of scarlet gauze, three yards of silk:

Tied round the ox’s head, this charcoal’s price.

Line 14: Yellow-robed official = agent of the imperial requisition.

LIU ZONG-YUAN

The Old Fisherman

Old fisherman spends his night beneath the western cliffs.

At dawn, he boils Xiang’s waters, burns bamboo of Chu.

When the mist’s burned off, and the sun’s come out, he’s gone.

The slap of the oars: the mountain waters green.

Turn and look, at heaven’s edge, he’s moving with the flow.

Above the cliffs the aimless clouds go too.

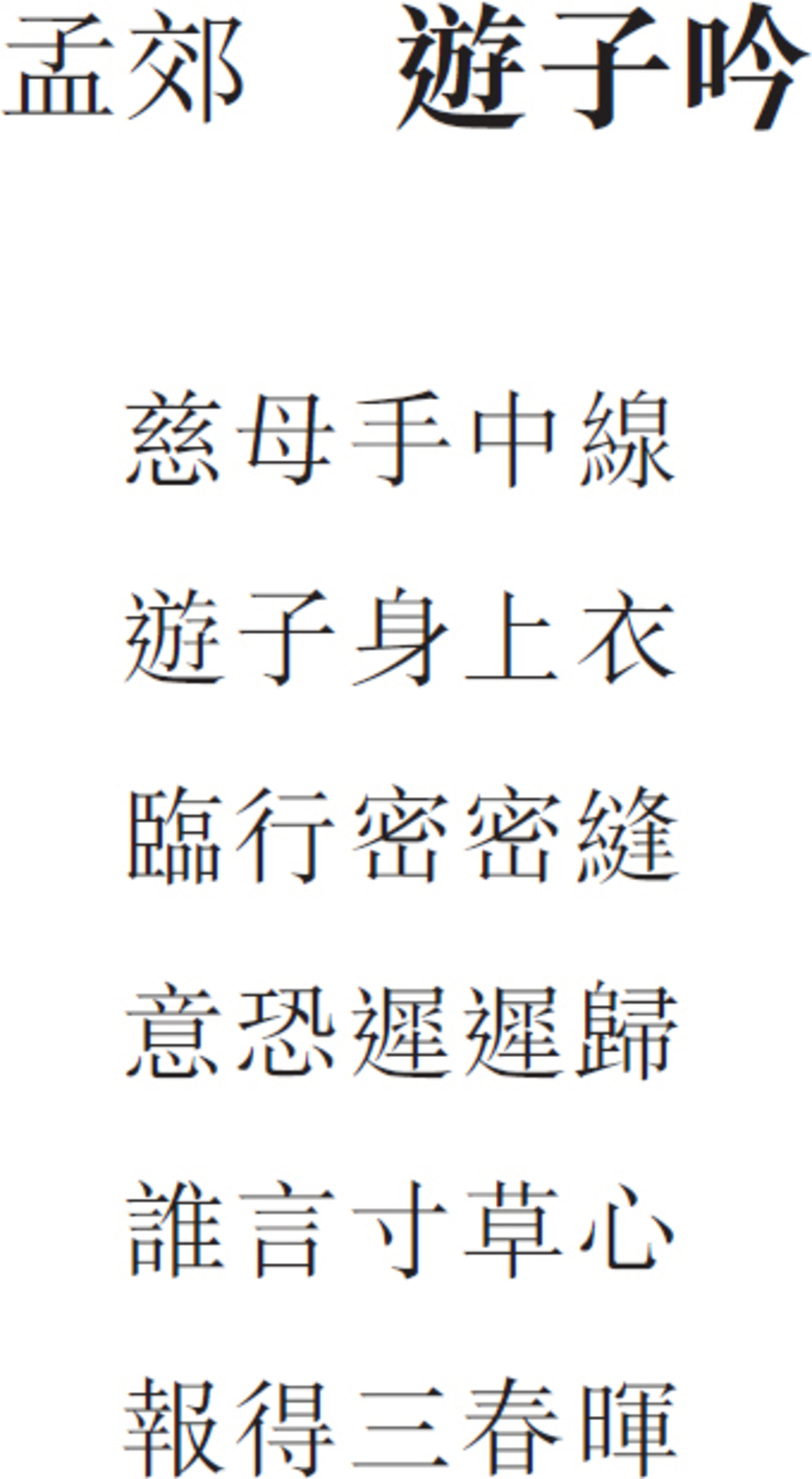

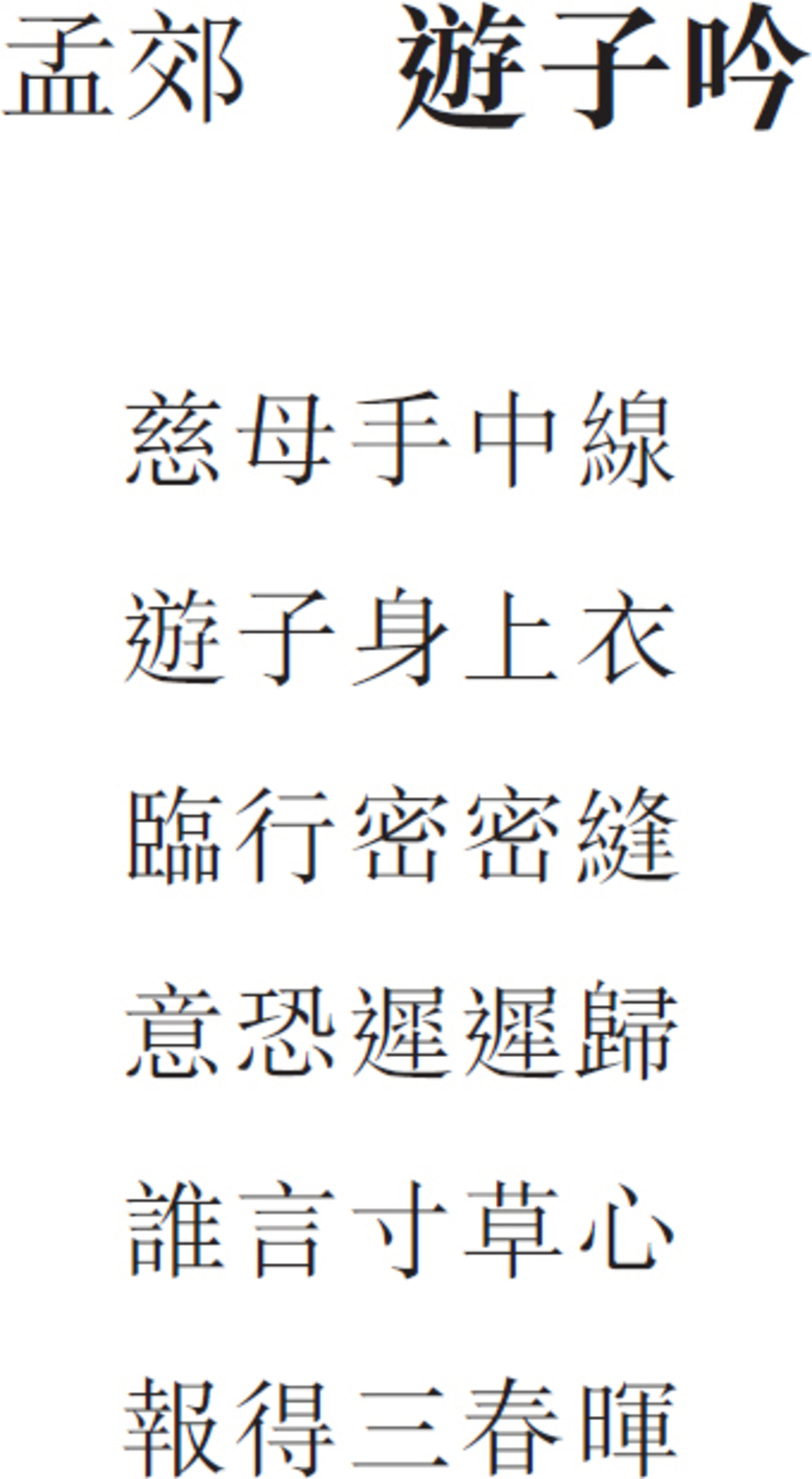

MENG JIAO

Song of the Departing Son

Loving mother; the thread in her hand,

Will become the cloak of the wandering son.

His departure approaches; the stitches grow smaller,

And smaller, in fear he’ll stay long.

Who would say an inch of longing, like an inch of grass

Could ever requite the radiant sun of spring.

Last line: sun of spring = maternal love.

LI HE

Autumn Comes

Wind in the plane tree startles the heart; the grown man, bitter.

By dying lamp the “spinning wheels” weep cold white threads.

Who’ll ever read these words, this green bamboo?

Till he banish the worms, gnawing powdery holes.

Thoughts tangle, this night, but heart’s at last set straight.

Cold rain, a fragrant soul, come to console the poet.

On autumn tomb a ghost chants Bao Zhao’s poem:

His angry blood, a thousand years beneath the earth, green jade.

Line 2: spinning wheels = metaphorical name for crickets.

Line 3: Before the invention of paper in the second century, books were written on slips of bamboo bound together.

Line 7: Bao Zhao, a fifth-century poet. A passage of his poem “Lamenting in a Cemetery” goes as follows:

Rich or poor, all will know the same fate,

Be their desires frustrated or fulfilled.

The dew, as it falls, speeds the end of the dawn.

Waves fall toward the eternal night.

LI HE

Don’t Go Out, Sir!

Heaven’s dark, The earth shut tight.

The nine-headed serpent feeds on our souls.

Snow and frost snap our bones.

The dogs set loose, snarl to our scent,

Licking their paws at the thought of the flesh

Of men who go girdled in orchids.

When God sends his chariot to bear you away,

Then all your hardships will end.

Jade stars dot your sword, of yellow gold will be your yoke.

But though I go horseback, there is no way home.

The waves that drowned Li-yang stand tall as mountains.

Venomous dragons glare at me, rattling their rings of gold,

And lions and griffins, slavering, drool.

Bao Jiao, a whole lifetime, slept on straw.

Yan Hui’s hair, at twenty-nine, was mottled white.

Yan Hui’s blood was not corrupted.

Nor had Bao offended heaven.

Heaven feared those jaws would close,

Therefore advanced them so…

Clear as it is, if you still doubt

Think on the madman who raved by the wall,

Writing the “Heavenly Questions.”

Line 3: The nine-headed snake of Zhao Hun (Calling the Soul) in “The Songs of Chu.”

Line 7: men who go girdled in orchids = virtuous men; cf. “The Songs of Chu.”

Line 12: Li-yang, a district in An-hui, which was transformed into a lake in a single night (see Huai-nan-zi).

Line 15: Bao Jiao, a hermit of Zhou who imposed such rigid rules of virtuous conduct upon himself that he died of hunger.

Line 16: Yan Hui, the favorite disciple of Confucius. Like Yan Hui, Li He had prematurely white hair, and died young.

Last line: Qu Yuan (340–? B.C.) wrote his “Heavenly Questions” drawing his inspiration from frescoes he had seen in the ancestral temple of the kings of Chu.

LI HE

Libation or the King of Qin

The King of Qin astride his tiger, wanders the eight poles.

His sword’s blaze shines in emptiness, cleaving heaven’s blue.

Xi He strikes the sun, a tinkling of glass.

Kalpas’ ashes flown and gone, now times of peace again.

As the dragon’s head spouts wine, enticing the Wine Star,

Golden zithers murmur in the night.

Feet of the rain walk Lake Dong-ting, to the music of the pipes.

Merry with wine he orders the moon to turn back on her course.

Beneath dense silver clouds the halls of jasper shine.

By palace gates the watchman cries first watch.

In the painted-tower phoenixes of jade sing prettily

Sea silk, red patterned, a fragrance light and pure.

The Yellow Birds in their reeling dance sink in the cup of a thousand tears.

Immortals, by the candle trees, wrapped in fine wax smoke,

In goddess Green Lute’s drunken eyes, tears pool.

Line 3: Xi He = driver of the chariot of the sun.

Line 4: In Buddhism the kalpa is a unit of measure of one cosmic cycle. At the end of each kalpa the universe is reduced to ashes.

Line 13: A variant in the texts suggests that this may be translated either as “Yellow Birds” or as “beautiful girls dressed in yellow.”

LI HE

The Tomb of Su Xiao-xiao

Solitary orchid, dew,

Like tear filled eyes.

Nothing to tie our hearts together.

Misty blossoms, I cannot bear to cut.

Grass for her carpet,

Pines, her roof;

The wind her robe, and

Water sounds, her pendants.

There, painted carriages

Are waiting in the night,

Green candles cool,

Weary with brilliance.

Beneath the Western Mound,

Wind drives the rain.

Su Xiao-xiao was a famous singing-girl of Qian-tang, Hang-zhou who lived during the Southern Qi dynasty (479–502).

LI HE

Lament: So Brief the Morning

Flying light, the flying light…

I bid you, take one cup of wine.

I do not know blue heaven’s height.

How broad the yellow earth!

Only the moon’s cold, sun’s warm,

Enough to cook a man.

Eat bear paws and grow fat.

Eat frogs, and waste away.

Where is the Spirit Lady,

And where the One itself?

East of the sky the Ruo tree,

Down in the earth, the dragon, torch in mouth.

I’ll cut off the dragon’s feet.

I’ll gnaw his flesh,

That he rise no more at dawning,

At dusk he lie not down.

Then the old men won’t die,

Nor young men cry.

Why swallow yellow gold,

Or down white jade?

Who is Ren Gong-zi,

Among the clouds, on his white mule?

Liu Che, in Mao-ling tomb, a pile of bones.

Ying Zheng, in his coffin of catalpa, rotting.

And all that abalone, wasted.

(Note for this page) In the most vehement terms, the poet decries the brevity of life. He proposes to slay the dragon that draws the chariot of the sun, recovering for man both plenitude and peace. He rails, however, against those whom he considers to have followed false paths in their search for immortality, men like Liu Che (Emperor Wu-di of the Han) and Ying Zheng (better known as Qin Shi Huang-di, the notorious first emperor of Qin). The latter died while on a journey: the ministers who accompanied him, desiring to keep his death a secret until they could return to the capital, surrounded the imperial carriage with rotten abalone in an attempt to mask the odor of the decomposing corpse.

LI HE

Song of the Sword of the Collator in the Spring Bureau

In the elder’s coffer, three feet of water,

Of old it dived deep in Wu Lake, beheading the dragon.

A slash of moon’s brightness, shaves cold dew.

White satin sash, spread flat, not rising to the breeze.

The sharkskin hilt is ancient, all bristling thorns.

Sea bird, temper flowered blade, white pheasant’s tail.

Truly this, sharp shard of Jing Ke’s heart

May it never shine among the characters of the Spring Bureau.

Knotted strands of coiling gold hang from the hilt.

Magic brightness; it could sunder Blue Fields Jade.

Draw, and the west’s White King will quake

And wail, his demon mother, in the autumn wilds.

Li He had a cousin who was employed as a collator in the Spring Bureau, a sort of secretariat to the crown prince.

Line 7: Jing Ke was a “knight errant” who became famous for his brave attempt at the assassination of the emperor of Qin.

Last line: Liu Bang, founder of the Han dynasty, is supposed to have killed a giant serpent that crossed his path. The same night an old woman appeared to him in a dream, crying and lamenting that he had killed her son, the White Emperor of the West.