The Business of War in Europe, 1000-1600

In the year 1000 the part of Europe known as Latin Christendom was overwhelmingly rural. Nearly everyone lived in villages where social roles were defined by a delicate interaction between tradition and the personal qualities of the individuals filling each role. In an emergency, every able-bodied person was expected to help with local defense—whether by carrying valuables to some fortified spot for safekeeping or by some more aggressive action against threatening outsiders. To be sure, with the spread of knighthood from its place of origin between the Rhine and the Seine rivers, a more effective defense against attack put most of the responsibility for meeting and repelling would-be plunderers on the shoulders of a small class of men who rode expensive war-horses and were trained in the use of arms from childhood. Knights’ weapons and armor were, of course, a product of specialized craftsmen, though very little is known about the manufacture and distribution of the arms and armor upon which the knights of Latin Christendom relied.1 Ordinary villagers supported the new military experts with contributions in kind. The quantity and character of such payments quickly achieved a customary definition, stabilizing social relations around the fundamental distinction between knights and commoners.

Priests and monks and bards fitted into this simple social hierarchy with no difficulty, but the handful of merchants and itinerant peddlers who also made a living in that rural society represented a potentially disruptive element. Market behavior was deeply alien to the social outlook of village life. Merchants or peddlers, coming as strangers into an unsympathetic environment, had to attend to their own defense. This introduced a second relatively well-armed element into society. It was connected with the knightly establishment of the countryside only by a series of unstable negotiated truces.

Another way of describing this situation is to say that for several centuries on either side of the year 1000 the weakness of large territorial polities in Latin Christendom required merchants to renegotiate protection rents at frequent intervals. Moving amidst a warlike, violence-prone society,2 European merchants had a choice between attracting and arming enough followers to defend themselves, or, alternatively, offering a portion of their goods to local potentates as a price for safe passage. In other civilized societies (with the possible exception of Japan), merchants were less ready to use arms on their own behalf and more inclined to cater to preexisting rent and tax-based authorities and depend upon their protection.

The merger of the military with the commercial spirit, characteristic of European merchants, had its roots in the barbarian past. Viking raiders and traders were directly ancestral to eleventh-century merchants of the northern seas. A successful pirate always had to reassort his booty by buying and selling somewhere. In the Mediterranean, the ambiguity between trade and raid was at least as old as the Mycenaeans. To be sure, trading had supplanted raiding when the Romans successfully monopolized organized violence in the first century B.C., but the old ambiguities revived in the fifth century A.D. when the Vandals took to the sea. Thereafter, from the seventh century until the nineteenth, cultural antipathy between Christian and Moslem justified and sustained a perpetual razzia upon the seas that bounded Europe to the south.

The knightly Latin Christian society that defined itself in the century or so before the year 1000 proved capable of far-ranging conquest and colonization. The Norman invasion of England in 1066 is the most familiar example of this capacity; but a geographically more extensive expansion occurred east of the Elbe where, by the mid-thirteenth century, German knights and settlers extended their sway across the north European plain as far as Prussia. Further east and north along the Baltic coast German knights imposed their rule on native peasantries all the way to the Gulf of Finland in the same century. On other frontiers Latin Christians also exhibited remarkable aggressiveness: in Spain and southern Italy at the expense of Moslems and Byzantines and, most spectacularly of all, in the distant Levant, where the First Crusade (1096–99) carried an army of knights all the way to Jerusalem.

By 1300, however, this sort of expansion had reached its limits. Climatic obstacles set bounds to the indefinite extension of the fields, cultivated by the moldboard plow, that provided the basic foodstuffs supporting western European society. When seed-harvest ratios sank too low, as happened in arid parts of Spain or in the cold chill of northern and eastern Europe, the heavy plow and the draft animals required to drive it through the soil had to give way to cheaper agricultural techniques. Along the same borderlands the relatively dense settlement that the moldboard plow could sustain yielded to more thinly populated landscapes in which pastoralism, hunting, gathering, and fishing played a more important part than they did in the heartland of Latin Christendom. Wherever knightly conquests outran the mold-board plow, social patterns differed from those of the west European heartlands. The resulting political regimes were often unstable and short-lived, as in the Levant where the crusading states disappeared after 1291, or in the Balkans, where Latin dominion, dating from the Fourth Crusade (1204), was largely supplanted by local dynasts as early as 1261. In Spain and Ireland, on the contrary, and along the east coast of the Baltic, conquest societies became enduring marginalia to the main body of Latin Christendom. Similarly, in Poland, Bohemia, and Hungary, kingdoms that consolidated around the effort needed to repel German knights took a form divergent from, yet closely related to, the knight and peasant pattern of western Europe.3

Pioneering the Business of War in Northern Italy

The military expansion of Latin Christendom in the eleventh century was accompanied by an expansion of the scope for market behavior. As in China in the same age, places where transport and communications were unusually easy led the way. In Mediterranean lands, Europe’s commercial development was also affected by the fact that skills were readily imported from adjacent, more developed societies (i.e., from Byzantium and from Moslem countries). To begin with, this configuration gave primacy to Italy. A secondary commercial center arose in the Low Countries where the navigable Rhine, Meuse, and Scheldt rivers converge. Overland portage routes linked these two main nodes of commercial and artisan activity; and exchanges between the two regions were consummated at a series of fairs held in Champagne. Little by little more time and effort went into production for market sale, sometimes at a distance. Specialization led to increased wealth, and altered social balances in favor of merchant-capitalists. In the most active economic centers, the preeminence of knights and of social leadership based on rural relationships came into question before the end of the twelfth century.

These social and economic changes were reinforced by a parallel weakening of knightly supremacy in war. In the eleventh century a few hundred Norman knights had been able to conquer and rule south Italy and Sicily; a few thousand sufficed to seize and hold Jerusalem at the very end of the century. Yet, in the twelfth century, an army of German knights met unexpected defeat in northern Italy at Legnano (1176) when they vainly charged pikemen who had been put in the field by the leagued cities of northern Italy. The military might of the Lombard League, attested by that victory, was essentially defensive, like the town walls which had begun to sprout wherever traders and artisans had become numerous enough to require and pay for this kind of protection.

The result was a standoff, in Italy at least, between older and newer forms of warfare and social leadership. Armed townsmen sought to control the surrounding countryside. How else assure safe passage for their goods and the punctual delivery of food within city walls? Sometimes an accommodation between rural landholders and the ruling elements of nearby towns proved possible; sometimes noble landholders moved into town to mingle with and rival the urban upper class of merchant-capitalists. On top of this, from the eleventh century onward, the rival claims of emperor and pope divided Italy. Both aspired to exercise a general hegemony over the existing medley of local rulers and jurisdictions, but only sporadically were they able to enforce overriding authority.

The military balance of power within Italy was as uncertain as the political. Traders, artisans, and their hangers-on in the larger towns were able to defend themselves from knightly attack as long as they sustained the discipline required to man city walls or array a formation of pikemen in the field. But this was hard to do in a world where primary social bonds were rapidly giving way to market behavior affecting and affected by persons and events hundreds of miles away. Consequent civic strife weakened urban defenses. Party conflict was fed by the larger political controversies of the peninsula and often was also envenomed by collision of interests between rich and poor, employer and employee. Under these circumstances, the practice of hiring strangers to fight on behalf of the citizens became increasingly important. But this meant that the ambiguous relationship between employer and employee, which already distracted the internal life of the wealthier Italian cities, extended to military matters as well.

Clearly, as trade and artisan specialization began to affect more and more people, primary relations within the local communities of Europe ceased to be effective regulators of everyday conduct. This opened up vast new problems of social and military management. A few cities in northern Italy pioneered effective response, for it was within their walls that impersonal market relationships first began to dominate the behavior of scores of thousands of persons.

A new factor came to the fore between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries when cities like Barcelona and Genoa expanded the scale of crossbow manufacture to such a point as to make that weapon critically important in battle. Crossbows were initially valued primarily for defending ships, since a handful of crossbowmen, stationed in a crow’s nest atop the mainmast, could make successful boarding even of a lightly crewed merchant vessel exceedingly difficult. But by the closing decades of the thirteenth century, crossbowmen became skilled and numerous enough to make a difference in land warfare as well. The ever-victorious career of the Catalan Company between 1282 and 1311 demonstrated crossbowmen’s newfound offensive capability, even when pitted against the most formidable horsemen of the age. For the Catalans first destroyed a (mostly French) army of knights in Sicily in 1282, and then went on in ensuing decades to defeat Turkish light cavalry with equal decisiveness on several Balkan and Anatolian battlefields. As in China, the manufacture of large numbers of powerful crossbows required metal-working specialists, but the crossbow’s simplicity in use made it a great equalizer in the field. Armored cavalrymen need not always prevail when any able bodied commoner could pull the trigger and unleash a crossbow bolt capable of knocking a knight from his horse at a distance of a hundred yards or more. No wonder the weapon was banned at the Second Lateran Council (1139) as being too lethal for Christians to use against one another!

Crossbows and pikes had to be supplemented by cavalry for flank protection and the pursuit of a vanquished foe. This obviously made war far more complicated than it had been when a headlong charge by a group of knights dominated the battlefields of Europe. Simple personal prowess, replicated within knightly families across the generations, was no longer enough to win battles or maintain social dominion. Instead, an art of war was needed. Someone had to be able to coordinate pikes, crossbows, and cavalry. Infantrymen needed training to assure steadiness in the ranks, for, were their formation to break apart, individual pikemen would find themselves at the mercy of charging knights; and the time required to cock a crossbow meant that archers, too, became vulnerable each time they discharged their weapons, unless some field fortification or an unbroken array of friendly pikes could protect them until they were ready to shoot again.

Not surprisingly, Italian citizens were not able to achieve the elaborate coordination needed for such an art of war all at once. Cities in other parts of Europe lagged still farther behind, relying mainly on passive defense behind city walls. Nevertheless, the military balance within Europe altered fundamentally with the transformation that townsmen and their trading brought to rural society between 1000 and 1300. On balance, the complexity of the new art of war reinforced localism. If prosperous cities found it difficult to exploit the new techniques, it was doubly difficult for older territorial units—principalities, kingdoms, and, largest of all, the Holy Roman Empire, to manage the new military resources effectively. Hence the changing forms of economic and military power that arose in Latin Europe during the eleventh and twelfth centuries led to the collapse of the imperial fabric in the thirteenth. This was followed a generation later by the failure of the papacy to erect a universal monarchy on the ruins of the Holy Roman Empire (clear by 1305).

Both empire and papacy were heritages from the Roman past. Memories of that past and its glories died hard, at least among political theorists, who reluctantly reconciled themselves to the political pluralism of rival sovereign states only in the seventeenth century. Had Popes Innocent III (1198–1216) and Boniface VIII (1294–1303) been able to make good their vision of a Christendom obedient to papal governance, subjecting local fighting men as well as peasants and townsmen to clerical control, western Europe would have come to resemble China, where the Son of Heaven exercised jurisdiction over peasants, townsmen, landowners, and soldiers through a corps of officials imbued with Confucian principles.

Of course Christianity was not the same as Confucianism, yet in interesting ways thirteenth-century administration of the Roman church paralleled Chinese bureaucratic procedures. At least a rudimentary education was required to qualify bishops and other high-ranking clergymen for office. Appointments were subject to papal review, at least in principle. Office was not hereditary, and a career open to talent often attracted gifted and ambitious men into clerical ranks. In all these respects Christian prelates of the thirteenth century resembled Confucian officials of Sung China.

Moreover, Christian doctrine was quite as hostile to the ethos of the marketplace as was Confucianism. The condemnation of usury was more explicit and emphatic in Christian theology than anything to be found in Confucian texts; and distrust between Christian clerics and Christian men-at-arms resembled the gulf separating Chinese mandarins from the soldiery of the Celestial Empire, though it was not nearly so wide. Had papal monarchy proved feasible, western Europe’s history would not have duplicated China’s bureaucratic experience, but divergences would surely have been far fewer than they actually were. In fact, however, the papal bid for effective sovereignty throughout Latin Christendom failed as miserably as the German emperors’ efforts had previously done. Christendom remained divided into locally divergent political structures, perpetually at odds with one another and infinitely confused by overlapping territorial and jurisdictional claims.

This political situation permitted a remarkable merger of market and military behavior to take root and flourish in the most active economic centers of western Europe. Commercialization of organized violence came vigorously to the fore in the fourteenth century when mercenary armies became standard in Italy. Thereafter, market forces and attitudes began to affect military action as seldom before.4 The art of war began to evolve among Europeans with a rapidity that soon raised it to unexampled heights. The history of the globe between 1500 and 1900 testified to Europe’s uniqueness in these matters, and the arms race that continues to strain world balances in our own time descends directly from the intense interaction in matters military that European states and private entrepreneurs inaugurated during the fourteenth century. What happened, and how it happened, therefore, deserve careful analysis.

First the general background. In many parts of Europe, hard times set in slightly before the end of the thirteenth century. Population pressed hard against available resources in Italy and the Low Countries. Wood supplies began to run short. Climate became distinctly colder, provoking widespread famines. Harsh divergence of interest between rich and poor, employer and employed, troubled European society. Urban uprisings and peasants’ revolts registered some of these difficulties, but all were eclipsed by the demographic disaster that set in after 1346 when the Black Death first began to ravage western Europe. Within a generation, a quarter to a third of the entire population of Europe died of bubonic infection. Recovery to pre-plague levels did not occur until after 1480.

With such a record it is obvious that the fourteenth century was not a very comfortable time for most Europeans. Yet there were counter trends that in the long run proved more significant than the century’s long catalog of disasters. A fundamental advance in naval architecture took place between 1280 and 1330,5 as a result of which larger, stouter, and more maneuverable ships could for the first time sail the seas safely in winter as well as in summer. All-weather ships were soon able to spin a more coherent commercial web around Europe’s coastline than had previously been possible. The price of wool in Southampton, of cloth in Bruges, of alum in Chios, of slaves in Caffa, of spices in Venice, and of metal in Augsburg all began to interact in a Europe-wide market. Bills of exchange facilitated payment across long distances. Credit became a lubricant of commerce and also of specialized, large-scale artisan production. A more complexly differentiated, potentially richer, yet correspondingly vulnerable economy began to control more human effort than in earlier centuries. Cities of north Italy and a secondary cluster of towns in the Low Countries remained the organizing centers of the whole system of exchanges.

Geographically, waters which had previously been effectively separated from each other became for the first time parts of a single sea room. The Black Sea to the east and the North Sea to the west fell within the extended scope of Italian-based shipping. Previously, the risks of seafaring in winter and on stormy seas had combined with political barriers at the Straits of Gibraltar and at the Dardanelles and Bosphorus to isolate these bodies of water from each other. Similarly, German shipping based in the Hansa ports linked the Baltic with the North Sea coast, where exchanges with the Italian-dominated seaways of the south occurred. The Baltic lands, indeed, entered upon a frontier boom in the fourteenth century at a time when other parts of Europe were troubled first by overpopulation and then by plague and social strife. Salt imported from the south enabled Baltic populations to preserve herring and cabbage through the winter. This assured a vastly improved diet, and an improved diet soon made manpower available for cutting timber and raising grain for export to the food-and-fuel-deficient Low Countries and adjacent regions.

Another economically important advance took place in the field of hard rock mining. In the eleventh century, German miners of the Harz mountains began to develop techniques for penetrating solid rock to considerable depths. Fracturing the rock and removing it was only part of the problem. Ventilation and drainage were no less necessary, not to mention the skills required for finding ore, and refining it when found. As these techniques developed, each reinforcing and expanding the scope of the others, mining spread to new regions, moving from the Harz mountains eastward to the Erzgebirge in Bohemia during the thirteenth century and then to Transylvania and Bosnia in the course of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Silver was the principal metal the German miners sought; but copper, tin, coal, and iron could also be mined more cheaply and in greater abundance by using techniques initially developed by silver miners.6

Overall, therefore, the picture of European economic development in the fourteenth century is not completely black. However acute local hardships and the plague disaster may have been, the market for goods of common consumption—grain, wool, herring, salt, metal, timber, and the like—became far more pervasive. This affected an expanding proportion of the work force and enriched the continent as a whole. Yet the new wealth remained precarious. Price fluctuations and changes in supply and demand brought severe suffering to thousands of individuals from time to time, because their livelihood had come to depend on what happened in distant markets over which they could have no personal control.

The primary managers of the commercial economy of Europe were Italians, operating from such towns as Venice, Genoa, Florence, Siena, and Milan. They bought and sold wholesale, brought new techniques to backwoods regions (e.g., organizing or reorganizing salt mines in Poland and tin mines in Cornwall), and, above all, extended credit to (or withheld it from) lords, clerics, and commoners.

Clerical, royal, and princely administration, as well as long-distance trade, mining, shipping, and other large-scale forms of economic activity, all became dependent on loans from Italian bankers. The relationship was not an easy one. The prohibition of usury in canon law created an aura of impropriety around credit operations. Reckless and impecunious monarchs could invoke the wickedness of usury to justify repudiation of their debts. Such an act could have widely ramifying consequences. The bankruptcy of the English King Edward III in 1339, for example, triggered a general financial crisis in Italy and provoked the first clearly recognizable business cycle in European history.

Taking a personal part in the defense of their hometowns could scarcely seem worthwhile to international merchants and bankers who found it easier and more comfortable to hire someone else to man the walls or ride into battle. A hired professional was also likely to be a better and more formidable soldier than a desk-bound banker or harassed businessman. Efficiency and personal inclination thus tended to coincide. As a result the town militia that in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries defended Italian cities against all comers began to give way to hired bands of professional fighting men.

This change was not simply a matter of convenience for the rich: the poor, too, found military duty increasingly burdensome. Campaigns became lengthier and well-nigh perennial. Having reduced their surrounding countrysides to subjection during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, adjacent cities began to enter upon border quarrels and trade wars against one another. A civic militia could not permanently garrison border strongpoints located as much as fifty miles from the city itself, since militiamen could not afford to stay away from home for indefinite periods of time.

Conversely, as professional bodies of troops came into being, their superior skill made militia men unlikely to prevail in battle, especially when success depended on the difficult coordination of infantry and cavalry movements. A further factor debilitating Italian civic militias was the growing alienation between upper and lower classes within the cities themselves, which made it difficult for rich and poor to cooperate wholeheartedly, whether in military or civil affairs. By about 1350, therefore, Italian civic militias had become archaic holdovers from a simpler past, seldom called into action and of dubious military value. Instead, organized violence came to be exercised mainly by professional troops, commanded by captains who negotiated contracts with appropriate city officials for specified services and time periods.7

Initially, the decay of primary group solidarity within the leading cities of Italy and of the town militias which were its military expression invited chaos. Armed adventurers, often originating from north of the Alps, coalesced under informally elected leaders and proceeded to live by blackmailing local authorities, or, when suitably large payments were not forthcoming, by plundering the countryside. Such “free companies” of soldiers became more formidable as the fourteenth century advanced. In 1354, the largest of these bands, numbering as many as 10,000 armed men, accompanied by about twice as many camp followers, wended its way across the most fertile parts of central Italy, making a living by sale and resale of whatever plunder the soldiers did not consume directly on the spot. Such a traveling company was, in effect, a migratory city, for cities, too, lived by extracting resources from the countryside through a combination of force or threat of force (rents and taxes) on the one hand and more or less free contractual exchanges (artisan goods for food and raw materials) on the other.

The spectacle of a wealthy countryside ravaged by wandering bands of plundering armed men was as old as organized warfare itself. What was new in this situation was the fact that enough money circulated in the richer Italian towns to make it possible for citizens to tax themselves and use the proceeds to buy the services of armed strangers. Then, simply by spending their pay, the hired soldiers put tax monies back in circulation. Thereby, they intensified the market exchanges that allowed such towns to commercialize armed violence in the first place. The emergent system thus tended to become self-sustaining. The only problem was to invent mutually acceptable contractual forms and practical means for enforcing contract terms.

From a taxpayer’s point of view, the desirability of substituting the certainty of taxes for the uncertainty of plunder depended on what one had to lose and how frequently plundering bands were likely to appear. In the course of the fourteenth century, enough citizens concluded that taxes were preferable to being plundered to make the commercialization of organized violence feasible in the richer and better-governed cities of northern Italy. Professionalized fighting men had precisely parallel motives for preferring a fixed rate of pay to the risks of living wholly on plunder. Moreover, as military contracts (Italian condotta, hence condottiere, contractor) developed, rules were introduced specifying the circumstances under which plundering was permissible. Thus, in becoming salaried, soldiering did not entirely lose its speculative economic dimension.

The merging of military enterprise into the market system of Italy passed through two distinguishable stages. By the 1380s self-constituted “free companies” had disappeared. Instead it became usual for cities to enter into contracts with captains who promised to hire and command a body of troops in exchange for agreed payments of money. In this way, a city could choose just what kind of a force it wished to have for a particular campaigning season; and by careful inspection of the force in question, magistrates, representing the taxpayers, could hope to pay for what they got, and no more. Contracts were drawn up initially for a single campaign and for even shorter periods of time. Troops were hired for a specific action: an assault on some neighboring border fortress or the like. The relationship was conceived simply as an emergency service.

A short-term contractual relationship, however, carried relatively high costs. Each time an agreed period of service expired, the soldiers faced a critical transition. If new employment could not be found, they had a choice between plundering for a living or shifting to some more peaceable occupation. Whether to disperse or remain leagued together as a single body of men was a related and no less critical decision. Obviously, to remain successful a captain had to find new contracts. Frequent shifts of employers and a careful husbanding of the condottiere’s salable resources—horses, men, arms, and armor—was a necessary implication of short-term contracts.

Friction and distrust between employer and employed was built into such a relationship, for both parties constantly had to look ahead to a time when their contractual relationship would come to an end. The free market in organized violence meant that today’s employee might become tomorrow’s enemy. Consciousness of this possibility meant that solidarity of sentiment between mercenary troops and the authorities who paid them was not, initially, very great.

But this fragility was uncomfortable to both sides, and by degrees, as the perennial succession of military emergencies became apparent to city magistrates and taxpayers, the advantages of making longer-term contracts became obvious. By the early decades of the fifteenth century, accordingly, long-term associations between a particular captain and a given city became normal. Lifetime service to a single employer became usual, though such ties were only the result of repeated renewals of contracts, each of which might run for two to five years.

Regular employment of the same captain went hand in hand with stabilization and standardization of the personnel under his command. Long-term professional soldiers were arranged into units of fifty or a hundred “lances.” A “lance” originally meant an armored knight and the following he brought with him into the field. But commercialization soon required standardization of personnel and equipment, making each lance into a combat team of three to six men, armed differently but mutually supportive in battle and linked by close personal relations. Regular muster and review then allowed magistrates to verify the physical reality of what they were paying for. Reciprocally, terms of service achieved contractual definition. In this way a regular standing army of known size and capability emerged in the better-governed cities of Italy during the first half of the fifteenth century.

Venice, when it launched its first campaigns aimed at conquest on terra firma (1405) took the lead in regularizing military condotta along these lines. Venetian precocity arose in part from the fact that similar practices had long prevailed in the fleet. Since before the First Crusade, salaried rower-soldiers, formed into standard ships’ companies, had been employed season after season to make Venetian power effective overseas. Management of semi-permanent land forces required only modest readjustment of such practices.8 Florence, on the other hand, lagged far behind in its adaptation to the new conditions of war, partly, at least, because humanistically educated magistrates like Machiavelli were dazzled by Roman republican institutions. Accordingly, they deplored the collapse of the town militia, and feared military coups d’état and the costs of professionalism so much that they sacrificed military efficiency in favor of economy and faithfulness to old traditions of citizen self-defense.

The Florentine fear of coups d’état was well grounded. Many ambitious condottieri did indeed seize power from civic officers by illegal use of force. The greatest city to experience this fate was Milan, which became a military despotism after 1450, when Francesco Sforza took power and began to use the resources of the city to support his military following on a permanent basis. Venice managed to escape any such fate, partly by careful supervision of potential usurpers, partly by dividing contracts among several different, mutually jealous captains, and partly by bestowing civic honors and gifts upon loyal and successful condottieri and arranging suitable marriages for them with members of the Venetian aristocracy.

Whether by usurpation or assimilation, therefore, outstanding condottieri quickly worked their way into the ruling classes of the Italian cities. As that occurred, the first phase of institutional adjustment between the old political order and newfangled forms of military enterprise can be said to have been achieved. The cash nexus came to be reinforced by a variety of sentimental ties connecting professional wielders of armed force to the newly consolidated states that divided sovereignty over the Italian landscape. A captain and his men might still shift employers, however, if some unusual advantage beckoned, or if his or the company’s pride were injured by some apparent preference for a rival.

The existence of such rivalries and the difficulty of adjusting them smoothly was, indeed, the principal weakness of the Venetian and Milanese military systems. No single captain could be appointed commander-in-chief of all Venetian armed forces without creating such jealousy among the subordinate commanders as to invite irrational displays of prowess or explicit disobedience on the field of battle. Only by assigning rival captains to separate “fronts” could friction be avoided; but this, of course, reduced the flexibility and military value of the armed establishment as a whole. Sforza, too, had similar problems in adjusting relationships among his subordinate commanders after his takeover of Milan in 1450.

The way around this sort of inefficiency was for civil administrators to enter into contractual relationships with smaller and smaller units, down to the single “lance.” This practice became increasingly common in both Venice and Milan by the 1480s. Civil officials thereby acquired a far greater control over the state’s armed forces, since they now could appoint whomever they wished to command an appropriate number of assembled “lances.” The effect was to promote the emergence of a corps of officers whose careers depended more on ties with civic officials who had the power of appointment and less on ties with the particular soldiers who from time to time might come under a given officer’s command. Such a pattern of subordination assured effective political control of organized force. Coups d’état ceased to be a serious threat.

A remarkably flexible and efficient system of warfare, relating means to ends according to financial as well as diplomatic calculations, thus came into being in the Po valley by the end of the fifteenth century. Its establishment constituted a second stage in the institutional adjustment to the commercialization of warfare by Italian cities.

Obviously, since states were relatively few and individual “lances” were numerous, terms of trade tilted strongly in favor of the employer and against the employee. The entire evolution, indeed, may be viewed as a development from a nearly free market (when blackmail and plundering defined protection costs by means of innumerable local “market” transactions) towards oligopoly (when a few great captains and city administrators made and broke contracts), followed by quasi-monopoly within each of the larger and better-administered states into which Italy divided. From a different point of view, one may say that an almost unadulterated cash nexus gave way by degrees to more complex linkages among armed men and with their employers. These linkages combined esprit de corps with bureaucratic subordination, loyalty to a commander, and (in Venice at least) also to the state.

However complex and variable from case to case, the overall result was to stabilize relationships between the civil and military elements in Italian society. This in turn allowed the leading Italian city-states to function as great powers in the politics of the age. In 1508, for example, the Venetians staved off attack by the so-called League of Cambrai, in which Pope Julius II, Emperor Maximilian, the king of France, and the king of Spain combined against them. Only in collision with the Turks did Venetian military might prove insufficient.

Later, when Italian cities became pawns and prizes in the wars between France and Spain, observers like Machiavelli (d. 1527) came to disdain the virtuosity with which Venice and Milan had adapted their administrative practices to the dictates of an age in which human relations in general and military relations in particular could no longer be managed on a face-to-face basis in accordance with custom and status, but responded instead to impersonal and imperfectly understood market relations. Until very recently, Machiavelli’s attack on mercenary soldiering seemed persuasive to nineteenth- and twentieth-century historians whose own experience of war emphasized the value of citizen-soldiers and patriotism. But in an age when military professionalism promises to make citizen-soldiers obsolete once again, scholars have begun to recognize the way in which the best-governed Italian cities anticipated, in the fifteenth century, military arrangements that became standard north of the Alps some two centuries later.9

The fact remains that by collecting tax monies to pay soldiers who proceeded to spend their wages and thereby helped to refresh the tax base, Italian city administrations showed how a commercially articulated society could defend itself effectively. By inventing administrative methods for controlling soldiers and tying their self-interest more and more closely to continued service with the same employer, these cities altered the incidence of instability inherent in market relationships.

Put differently, efficient tax collection, debt-funding, and skilled, professional military management kept peace at home, and exported the uncertainties of organized violence to the realm of foreign affairs, diplomacy, and war. States that lagged in developing an efficient internal administration of armed force, like Florence and Genoa, continued to experience sporadic outbreaks of civil violence. Venice, the most successful innovator in the management of armed force, entirely escaped domestic upheavals, though it barely survived external attacks provoked by the Republic’s long series of diplomatic and military successes on Italian soil.

The Gunpowder Revolution and the Rise of Atlantic Europe

The Italian state system as a whole (together with the economic relationships that concentrated financial resources so remarkably in a few Italian cities) was vulnerable to two different, yet interconnected, processes of change. First the most obvious: political rivalries and diplomatic alliances among competing states could not be confined to the Italian peninsula itself. When newly consolidated monarchies, commanding comparatively vast territories, chose to intervene in Italian affairs, the sovereignty of mere city-states, however skillfully managed, could not permanently be maintained. This was signaled towards the close of the fifteenth century, when first the Ottoman Empire (1480) and then France (1494) dispatched powerful expeditionary forces to Italian soil. Though both soon withdrew, divided Italy’s inability to check massive outside intervention became clear to all concerned. In the next century the peninsula accordingly became a theater of war where foreign powers competed for control of Italians’ superior wealth and skill.

The second source of instability was technological. Commercialization of military service depended upon, and simultaneously helped to sustain, the commercialization of weapons manufacture and supply. After all, a soldier without appropriate arms was of little value, whereas an armed man might sell his services at a price related to the kind of arms he possessed and the skill with which he could use them. Easy and open access to arms was therefore a sine qua non of mercenary war.

Ordinary long-distance trade also depended upon free access to weapons, for an unarmed ship or caravan could not expect to arrive safely at its destination. Indeed, successful trade across political frontiers required the same delicate combination of diplomatic negotiation, military readiness, and financial acumen that was needed for successful management of close-in defense of the city and its dependent territory. Perhaps the relationship should be put the other way: skills and aptitudes developed for the successful pursuit of longdistance trade, upon which the wealth and power of the great cities of Italy had come to depend, provided the model and context within which Italians invented a new and distinctively European pattern of diplomacy and war.

The system maintained strong incentives for continued improvements of weapons design. When many different purchasers entered the market, and many different artisan shops produced arms and armor for the public, any change in design that cheapened the product or improved its performance could be counted on to attract prompt attention and propagate itself rapidly. Accordingly an arms race, of the kind that has often manifested itself among European peoples subsequently, broke out in the fourteenth century. It centered mainly in Italy. The effect at first was to confirm and strengthen the formidability of Italian armed forces; before long, however, new weaponry began to favor larger states and more powerful monarchs.

As long as the race lay between ever more efficient crossbows and more and more elaborate plate armor, Italian workshops and artisan designers kept the lead. This was the agenda of the fourteenth century, beginning with the introduction of a simple “stirrup” (1301) (known in China since the eleventh century) that allowed archers to cock their crossbows faster, and going on to the design of increasingly powerful bows, substituting steel for wood in the arc of the bow after about 1350, and then employing a windlass to pull back the string (1370).10 Thereafter, crossbow design stood still. Inventiveness concentrated instead on gunpowder weapons. But before that time, each improvement in the power of crossbows was matched by improvements in the design of armor. Milan was a major locus for the manufacture of armor, but the production of crossbows does not seem to have had any comparable center, unless it was Genoa. That city became famous among northern rulers as the place from which to recruit crossbowmen; and perhaps the Genoese enjoyed a certain primacy in crossbow manufacture. But hard data seem lacking.

The next episode in the technological race between offensive and defensive weapons involved the use of guns. The idea that the explosive power of gunpowder, if suitably confined, might be made to shoot a projectile with previously unattainable force seems to have dawned almost simultaneously upon European and Chinese artificers. At any rate, the earliest drawings that clearly attest the existence of guns date from 1326 in Europe and from 1332 in China. Both drawings portray a vase-shaped vessel, armed with an oversized arrow that projects from its mouth. This certainly suggests a single origin for the invention, wherever it was actually made.11

But even if the idea of guns as well as of gunpowder reached Europe from China, the fact remains that Europeans very swiftly outstripped the Chinese and every other people in gun design, and continued to enjoy a clear superiority in this art until World War II. But Italians do not ever appear to have attained the primacy as gunfounders that they had enjoyed in crossbow manufacture and armor making, perhaps because European guns quickly became giant tubes, weighing more than a ton. This put Italians at a disadvantage, since they had to import metal from the north, and overland portage was expensive. Except in the case of untransportable objects, like the guns that battered down Constantinople’s walls in 1453, it was easier to refine the ore and to produce finished metal goods close beside the mining sites. Italian metal workers therefore could not easily compete with gun-founders nearer the source of supply. Consequently as soon as guns became critical weapons in war, Italian technical primacy in the armaments industry decayed.

Before considering the early development of gunpowder weapons, it seems best to glance briefly at what had been happening north of the Alps, where the feudal system, according to which a knight owed his lord military service in return for a grant of income-producing land, was much more firmly established than it had ever been in Italy. When the Hundred Years War (1337–1453) began, the French king still relied primarily on the infeudated chivalry of his kingdom to meet and repel the English invaders,12 though by the time of the Battle of Crécy (1346) he had taken the precaution of supplementing the knightly array with crossbowmen hired in Genoa, hoping thereby to counterbalance the mercenary longbowmen in the English army.

From the beginning, English armies in France were promised pay, but seldom received it in the field. Instead, they lived off the country by seizing food and forage for immediate consumption, hoping all the while for some windfall—a hoard of silver or a great man’s ransom—that would bring them at least temporary riches. Circulation of goods through buying and selling had not developed to a sufficient level in most of France for anything like the regulated fiscality of Italian mercenary service to stabilize itself. Nevertheless, the transfers of tangible wealth that resulted from the passage of plundering armies—melting down church treasure, for example—must have stimulated market exchange. The hordes of sutlers and camp followers who attended English and French armies in the field regularly bought and sold; and so of course did the soldiers when they failed to get exactly what they wanted by stealing and plundering. As earlier in Italy, an army in the field with its continual appetite for supplies acted like a migratory city. In the short run the effect on the French countryside was often disastrous; in the long run armies and their plundering expanded the role of buying and selling in everyday life.13

As a result, by the time the French monarchy began to recover from the squalid demoralization induced by the initial English victories and widespread disaffection among the nobility, an expanded tax base allowed the king to collect enough hard cash to support an increasingly formidable armed force. This was the army which expelled the English from France by 1453 after a series of successful campaigns. The same force allowed Louis XI (1461–83) to take possession of a large part of the inheritance of Charles the Bold of Burgundy after that ruler met his death in a battle against the Swiss (1477). The kingdom of France thus emerged on the map of Europe between 1450 and 1478, centralized as never before and capable of maintaining a standing professional army of about 25,000 men year in and year out, with an extreme upper limit of 80,000 available for mobilization in time of crisis.14

Mere numbers, however, do not tell the tale. The French army that drove the English out of Normandy and Guienne, 1450–53, did so by bringing heavy artillery pieces to bear on castle walls, one after another, whereupon previously formidable defenses came tumbling down in a matter of hours, if the garrison did not prefer to surrender. A century of rapid development of cannon design lay behind this dramatic demonstration of the power gunpowder weapons had attained.

From the very beginning, the explosive suddenness with which a gun discharged somehow fascinated European rulers and artisans. The effort they put into building early guns far exceeded their effectiveness, since, for more than a century after 1326, catapults continued to surpass anything a gun could do, except when it came to making noise. Yet this did not check experimentation.15

The first important change in gun design was to substitute a spherical shot (usually made from stone) for the arrowlike projectiles of the earliest guns. This went along with a shift from the early vase shape to a tubular design for the gun itself, allowing expanding gases from the explosion to accelerate the projectile while it traveled the length of the barrel. Such a design produced far higher velocities than had been attainable before.

Artillery Development in Europe, 1326–1500

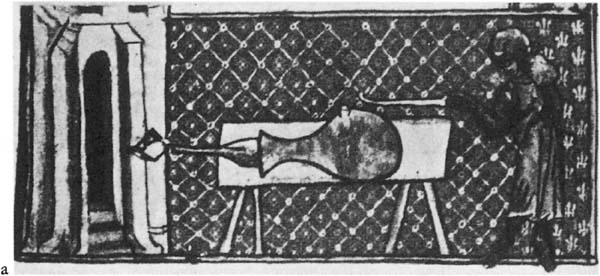

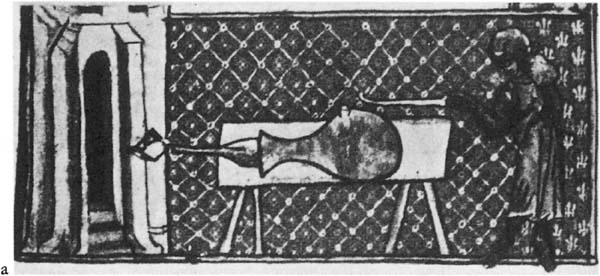

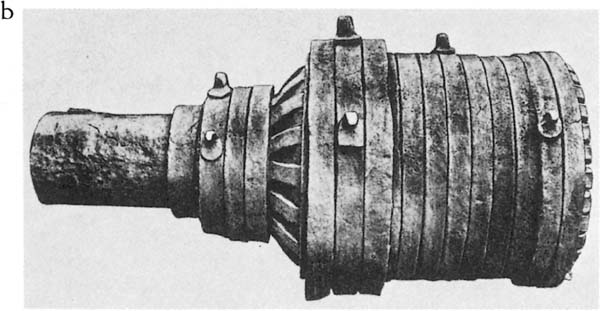

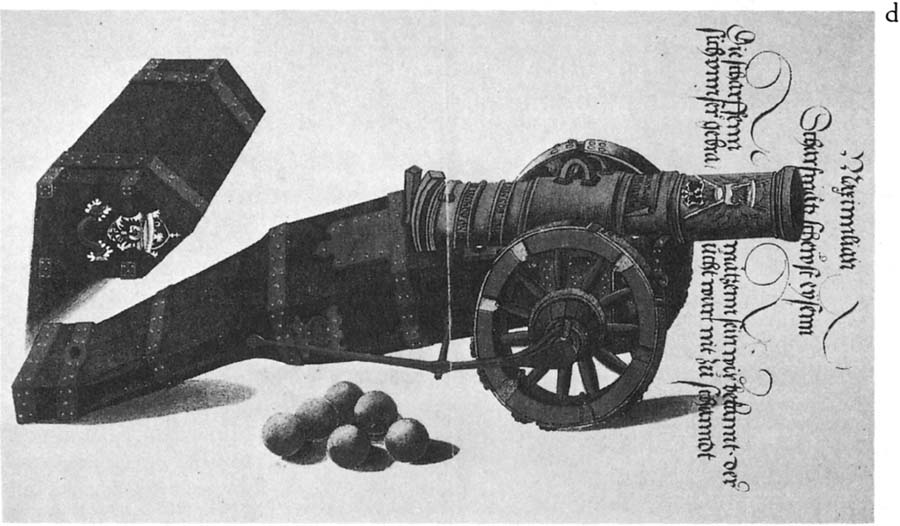

These four drawings show how European craftsmen and rulers collaborated to develop a formidable artillery out of the ineffective toy depicted in 1326 (a). The two giant stone-throwing bombards, one of wrought iron (b) and one cast in bronze (c), were superseded in the second half of the fifteenth century by mobile siege artillery (d) that used denser iron cannonballs and accelerated them more rapidly by burning “corned” powder. The result was a weapon that could demolish any existing fortification in no more than a few hours.

a, Bernard Rathgen, Das Geschütz im Mittelalter (Berlin: VDI, 1928), Tafel 4, Abbildung 12. Miniature from the manuscript of Walter de Milimete, at Oxford, A.D. 1326.

b, Ibid., Tafel 7, Abbildung 22. Stone throwing bombard, Vienna, made about A.D. 1425.

c, A. Essenwein, Quellen zur Geschichte der Feuerwaffen (Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1877), vol. 2, pl. A. XXI-XXII. Brunswick bombard, cast in 1411 and recorded in a copperplate drawing in 1728.

d, Ibid., pl. A.LXXII-LXXIII. Gun cast for Emperor Maximilian between 1500 and 1510, reproduced from Codex icon. 222, Münich Königlichen Hof- und Staatsbibliothek.

Higher velocities, in turn, induced gunmakers to try for bigger and bigger calibers on the theory that a larger projectile would exercise decisive shattering force on enemy fortifications. Bigger guns carrying heavier projectiles and larger charges of powder had to be made stronger. The earliest giant guns were fabricated by welding bars of wrought iron together; but such “bombards” were liable to burst. A more satisfactory solution was to employ metal-casting techniques which European bell makers had already developed to a high degree of perfection. Guns cast as a single piece of bronze or brass proved far more reliable than any built-up design, all of which were, accordingly, abandoned.

By 1450, therefore, supplies of copper and tin to make bronze and of copper and zinc to make brass became critically important for Europe’s rulers. When the new guns spread to Asia, a second bronze age set in. It lasted for about a century until technicians imported into England from the Continent discovered in 1543 how to cast satisfactory iron cannon. They thereby cheapened big guns to about a twelfth of their former cost, just as the iron-age blacksmiths had cheapened swords and helmets in the twelfth century B.C.16

Strictly speaking, therefore, the second bronze age lasted less than a century (1453–1543). But English ironmasters could not supply every ruler of Europe; and even after the Swedes and Dutch developed an international trade in iron guns in the 1620s, bronze and brass cannon continued to be preferred. Thus, for example, it was only in the 1660s, when Colbert set out to build a navy and needed thousands of guns for his ships and shore installations, that the French went over to iron guns.17 Prior to that time, access to copper and tin was of vital strategic importance to the rulers of the world.

Economic patterns registered this fact. The importance of central European copper and silver mines increased sharply, for example. The burst of prosperity in south Germany, Bohemia, and adjacent regions in the late fifteenth century reflected a mining boom in those parts of Europe; so did the financial empire raised by the Fuggers and other south German bankers, who briefly rivaled older Italian centers for managing large-scale interregional economic enterprises.18 A similar period of economic effervescence in the West Country of England was related to intensified exploitation of the Cornish tin mines. Likewise, Japanese copper and Malayan tin became critically important when the sovereign value of bronze artillery became apparent to the rulers of India and the Far East in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The substitution of iron for bronze and brass cannon eventually undercut central Europe’s mining prosperity. Cheap silver from the New World began to compete with the products of European mines at almost exactly the same time that copper mining was affected by the appearance of cheaper gunmetal. But the setback in central Europe was offset by gains elsewhere. England in the sixteenth and Sweden in the seventeenth century profited most directly from the new importance of iron in cannon making. The political and military history of Europe turned to some degree on these facts.

Long before the second bronze age came to a close, gun design underwent a second major advance. The bombards of the mid-fifteenth century were so big (often thirty inches or more in diameter and twelve to fifteen feet long) that they could be moved only with the greatest difficulty. The cannon that breached Constantinople’s walls in 1453, for example, were cast on the spot, since it was easier to bring the raw materials to the scene of action and build the necessary furnaces and molds outside the walls than it would have been to move the finished guns. However powerful their discharge, the immobility of such giant weapons was a serious handicap and an obvious challenge to gunfounders.

Between 1465 and 1477 an arms race between France and Burgundy19 provided artisans and rulers with means and motive to invent a practical solution to the problem. The gunfounders of the Low Countries and France discovered that much smaller weapons could do the same damage as bombards of three times the size if the gun tubes were made strong enough to fire denser iron cannonballs instead of stones. Iron cannonballs were also cheaper to make and could often be reused, whereas giant stone projectiles shattered on impact and were difficult and expensive to shape by hand and transport to the scene of action.

A second technical improvement came in at the same time: the practice of forming gunpowder into small grains or “corns.” This allowed a more rapid ignition, since the exposed surfaces of the separate corns could all burn at once. The explosion became correspondingly more powerful, for rapidly generated gases had less time to leak out around the cannonball while it accelerated along the barrel.20 This put additional strain on the gunmetal of course, but the bronze founders of the Low Countries discovered how to thicken the critical area around the chamber, where the explosion occurred, and tapered the thickness of the barrel towards the cannon mouth in proportion to the drop-off of pressure behind the projectile.

With suitable mounting and strong enough horses, powerful siege guns of about eight feet in length, designed to fire an iron ball of between twenty-five and fifty pounds, could travel cross-country with relative ease. This required specially designed gun carriages, with stout axles and wheels and long “trails” extending behind the gun. By mounting the gun on trunnions near its center of gravity, it became possible to elevate the tube to any desired angle without dismounting it from the carriage on which it traveled. Recoil could be absorbed by allowing the gun and its carriage to jerk backwards a few feet. To fire again, it might be necessary to wheel the carriage forward to the initial firing position, but this could be done by using simple levers and without hitching the horses. When it was time to move on, a few minutes sufficed to lift the trails from the ground, put a limber underneath, and set off. Rapid transition from traveling position to firing position and vice versa was matched by the fact that these guns could go wherever a heavy wagon and team could pass. In essence, the siege gun design developed in France and Burgundy between 1465 and 1477 lasted until the 1840s, with only marginal improvement.21

Guns of this radically new design accompanied the French army that invaded Italy in 1494 to make good Charles VIII’s claim to the throne of Naples. The Italians were overawed by the efficiency of the new weapons. First Florence and then the pope yielded after only token resistance; and on the single occasion when a fortress on the border of the kingdom of Naples did try to resist the invaders, the French gunners required only eight hours to reduce its walls to rubble. Yet not long before, this same fortress had made itself famous by withstanding a siege of seven years.22

The clumsy bombards of 1453 had already altered the balance between besieger and besieged, but the resulting disturbance to established power relationships was enormously magnified by the French and Burgundian invention of mobile siege guns between 1465 and 1477. Wherever the new artillery appeared, existing fortifications became useless. The power of any ruler who was able to afford the high cost of the new weapons was therefore enhanced at the expense of neighbors and subjects who were unable to avail themselves of the new technology of war.

In Europe, the major effect of the new weaponry was to dwarf the Italian city-states and to reduce other small sovereignties to triviality. The French and Burgundians did not long retain a monopoly, of course; nearby territorial monarchs quickly acquired siege guns of the new design, including the Hapsburg emperors and the Ottoman sultans.23 A mighty struggle among the newly consolidated powers of Europe ensued, lasting through most of the sixteenth century and reducing the Italian city-states to the condition of pawns to be fought over.

Yet the ingenuity that made Italian skills the cynosure of all who encountered them was not baffled for long by the heightened power of siege guns. As a matter of fact, even before encountering the formidable new French guns in 1494, Italian military engineers had been experimenting for half a century in desultory fashion with ways to make old fortifications better able to withstand gunfire. After that date the problem assumed an entirely new urgency for every existing political authority in Italy. The country’s best brains were devoted to seeking a solution, including those of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo.24

Partly by accident, or perhaps one should say through hasty improvisation, the Italians quickly discovered that loosely compacted earth could absorb cannon shot harmlessly. The Pisans, besieged by the Florentines in 1500, made this discovery when they built an emergency wall of earth inside their endangered ring wall. As a result, when cannon fire brought the stones of their permanent fortification tumbling down, a new obstacle confronted the besiegers which they were unable to cross. To make a rampart of earth, one had to dig: and by shaping the resulting hole in the ground so as to give it a vertical forward face, the ditch thus formed became a sort of negative, or inverted, wall, presenting an attacker with a very difficult obstacle, and one that was entirely proof against destruction by cannon.25

This fundamental idea, later embodied in more permanent forms, with masonry facings to the ditch, went far to solve the problem of how to protect against gunfire. Bastions and outworks, armed with guns and defended by ditches, were soon added. When properly located, such outworks could bring a withering crossfire against anyone trying to cross the ditch and assault the wall. Outworks’ artillery also had a second role to play, for by directing counter battery fire against the besiegers’ guns, the accuracy and force of the attack could be sharply reduced.26

By the 1520s, fortifications on the new Italian model were again quite capable of resisting even the best-equipped attackers. But their cost was enormous. Only the wealthiest states and cities could afford the scores of cannon and the enormous labor of construction required by the trace italienne, as this type of fortification came to be called beyond the Alps.

Nevertheless, by checking the sovereignty of siege cannon so quickly, the trace italienne played a critical role in European history. By the 1530s, as cannon-proof fortifications began to spread from Italy to other parts of Europe, high technology once again favored local defenses, at least in those regions where governments could afford the cost of the new fortifications and the large number of cannon they required. This put a very effective obstacle in the way of the political consolidation of Europe into a single imperial unity at almost the same time that such a possibility became conceivable, thanks to the extraordinary collection of territories that the Hapsburg heir, Charles V of Ghent, acquired between 1516 and 1521. As Holy Roman Emperor of the German nation, Charles laid claim to a vague primacy over all of Christendom; and as ruler of Spain, the Low Countries, and of broad regions in Germany, he seemed to have the resources to give new substance to the ancient imperial dignity.

His first enterprise, after putting down rebellion in Spain, was to drive the French out of Italy. By 1525 he had succeeded; and in the following decades his troops (mainly Spanish) made good their control over both Naples and Milan. He thereby reduced the other Italian states to uneasy dependence, sporadically punctuated by futile efforts to throw off what was often felt to be a Spanish yoke. Success in Italy, however, provoked cooperation between French and Ottoman rivals to the Hapsburg power in the larger theater of the Mediterranean, while, in the north, German princes resisted consolidation of Charles’s imperial authority by resorting to military action whenever they judged it necessary.

Obviously, fortifications capable of resisting superior field forces for long periods of time could play a critical role in checking empire-building. Construction of such fortresses therefore went on apace, first mainly in Italy, later in more peripheral parts of Europe. As a result, after 1525, large-scale battles, which had been characteristic of the first two and a half decades of the Italian wars, ceased. Sieges set in instead. Imperial consolidation halted halfway, with Spanish garrisons in Naples and Milan supporting an unstable Hapsburg hegemony in Italy. By the 1560s, a similar barrier halted Ottoman expansion, as the new style of fortress arose in such places as Malta (besieged vainly by the Turks in 1565) and along the Hungarian frontier.

In their first decades, before the Italian landscape became thickly dotted with cannon-proof fortifications, the Italian wars (1499–1559) had served as a forcing house for the development of effective infantry firearms, and for the invention of tactics and field fortifications to utilize the firepower that muskets and arquebuses began to exhibit in battle. The French failure in Italy, in fact, can be attributed largely to an excessive reliance on Swiss pikemen, heavy cavalry, and their famous siege guns. The Spanish were readier than the French to experiment with musketry as a supplement to pike formations and proved especially adept at making use of field fortification to protect infantry from cavalry attack.

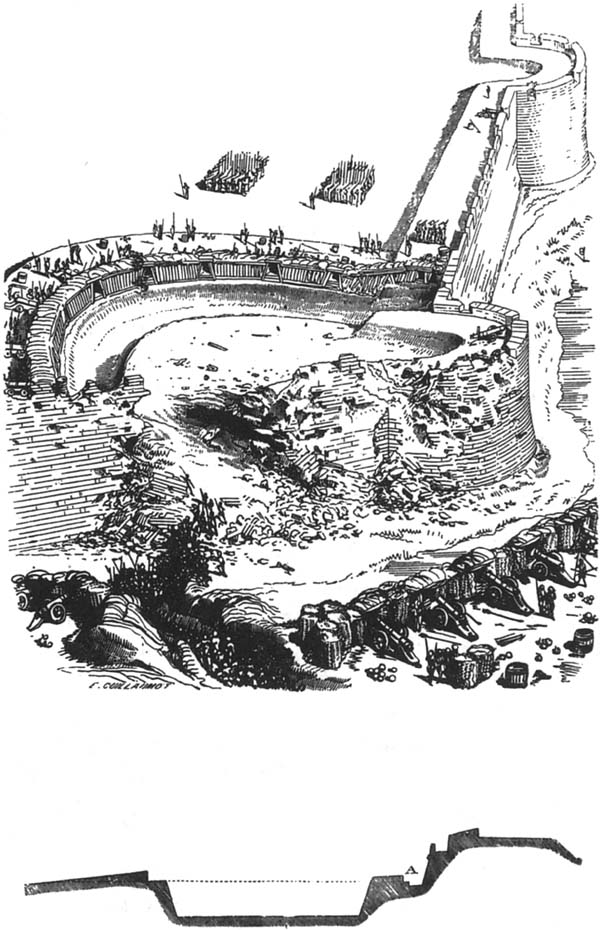

How Europeans Checked the Gunpowder Revolution

These drawings by a French architect of the nineteenth century, E. Viollet-le-Duc, show how an emergency response to walls crumbling under gunfire was developed into a new style of fortification that made sieges once again long and difficult to conduct. The drawing upper left shows a shallow ditch and emergency wall, with gun ports, erected behind a newly made breach, thus confronting the attackers with a further formidable obstacle to their capture of the city. Below is a cross-section of the fully developed trace italienne, showing the way in which ditch and walls were combined to protect a city from gunfire. Note that the shallow angle of the glacis on the left of the ditch made it impossible to strike the wall with direct fire unless cannon could be mounted on the very lip of the ditch, as in the drawing on the right. Yet that shows how even after the wall had been breached and the moat filled with debris, a suitably designed bastion could still make an assault very costly to the attackers.

E. Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du IXe au XVIe siècle (Paris, 1858), vol. 1:420 (fig. 57), 452 (fig. 75), and 441 (fig. 72).

As a result, the so-called Spanish tercios emerged from the Italian wars as the most formidable field force in Europe. A tercio comprised a mass of pikemen who protected a fringe of musketeers posted around the central square of pikes. This formation proved capable of withstanding cavalry attack in the open field and could charge an enemy with lowered pikes just as effectively as the Swiss, who had invented this tactic. Only occasionally did artillery play much of a role in battles; it was too difficult to get heavy guns to the battlefield in time.

The tactics of the Spanish tercios gave a decisive battlefield role to infantry, not only in defense but in attack as well. Until the sixteenth century the prestige of knighthood in battle had lingered stubbornly, especially in France and Germany, where knighthood was deeply rooted in the social structure of the countryside. But after 1525 or so, the idea that a gentleman could fight on foot with almost as much dignity as if he were mounted became irresistible in practice, even among the French and Germans. Cavalry, after all, had almost no role in siege warfare, which became the principal growing point in the art of war for the ensuing half-century.

Despite all the skill brought to bear on the art of combining different arms and formations in battle to achieve success, Spanish victories in the field always fell short of assuring a general supremacy for the Hapsburg cause. As long as the defeated party had a multitude of prepared fortifications to fall back upon, where the shattered remnants of a field force could take refuge and expect to resist for many months, even a series of victories did not suffice to establish hegemony.

Hence, the superiority of Spanish soldiers in battle, although it did allow Charles V to drive the French from Italy, did not allow him to overthrow the independent power of the French monarchy. Nor was he able to suppress the autonomy of German princes or the diverse local immunities of his Netherlandish subjects, even when they began to espouse various forms of Protestant heresy. As a result, perpetual competition among European states continued to provoke sporadic arms races, when from time to time a new technology seemed capable of conferring significant advantage in war upon its possessor.

In other parts of the earth, however, the Italian riposte to cannon fire was not forthcoming. Instead, the edge that mobile siege cannon gave to their possessors allowed a series of relatively vast gunpowder empires to come into existence across much of Asia and all of eastern Europe. The Portuguese and Spanish overseas empires of the sixteenth century belong to this class, for they were defended (and in the Portuguese case created) by ship-borne artillery, which differed from that of land-based powers mainly in being more mobile. Ming China (1368–1644) depended less upon cannon that did such upstart empires as the Mughal in India (founded 1526), the Muscovite in Russia (founded 1480), and the Ottoman (after 1453) in eastern Europe and the Levant. The Safavid empire in Iran depended less on gunpowder weaponry than did its neighbors, though under Shah Abbas (1587–1629) the centralizing effect of the new technology of war manifested itself there too. Similarly, in Japan the establishment of a single central authority after 1590 was facilitated by the way small arms and even a small number of cannon made older forms of fighting and fortification at least partially obsolete.

The extent of the Mughal, Muscovite, and Ottoman empires was defined in practice by the mobility of their respective imperial gun parks. In Russia, the Muscovites prevailed wherever navigable rivers made it possible to bring heavy guns to bear against existing fortifications. In the interior of India, where water transportation was unavailable, imperial consolidation remained precarious, since it required great effort to cast guns on the spot, as Babur (1526–30) did, or else to haul them overland, as his grandson Akbar (1566–1605) did. But in each of these states, even in those immediately abutting upon western Europe, once a decisive advantage accrued to central authorities through the use and monopolization of heavy guns, further spontaneous improvements in gunpowder weapons ceased. Rulers had come into possession of what obviously seemed to be an ultimate weapon, however difficult it might sometimes be for heavy artillery to be brought to bear in a given locality. There was little incentive to experiment with new devices. On the contrary, anything that might tend to make existing artillery pieces obsolete must have seemed wantonly wasteful and potentially dangerous to those in power.

A European Army of the Sixteenth Century in Marching Order

This bird’s-eye view (following page) shows how the European art of war combined different arms and formations in the sixteenth century. Cavalry, light and heavy artillery, pikemen, and arquebus-carrying infantry are accompanied by supply wagons that could double as emergency field fortification around the encamped army’s perimeter. Flags projecting above the array of pikes signified subordinate units of command, which allowed maneuver on the battlefield. This is an idealized portrait; in practice guns could seldom keep up with marching troops, and ground was almost never fiat enough to permit an army to move forward in such a broad-front formation.

Leonhardt Fronsperger, Von Wagenburgs und die Feldlager (Frankfurt am Main, 1573; facsimile reproduction, Stuttgart, Verlag Wilh. C. Rübsamen, 1968).

In western Europe, on the contrary, improvements in weapons design continued to be eagerly sought after. Whenever anything new really worked, it spread from court to court, shop to shop, and camp to camp with quite extraordinary rapidity. Not surprisingly, therefore, the equipment and training of European armed forces soon began to outstrip those of other parts of the civilized world. Western Europe’s emerging battlefield superiority became apparent to the Ottoman Turks in the war of 1593–1606, when, for the first time, Turkish cavalry met disciplined infantry gunfire.27 The Russians discovered a similar gap between themselves and their neighbors to the west in the course of the Livonian war (1557–82).28 Asian states only discovered the discrepancy later. By that time the gap between their own military skill and that of the Europeans had become much greater than was the case at the turn of the seventeenth century—often too great to be bridged successfully without first submitting to foreign invasion and conquest. Europe’s extraordinary global imperialism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries became possible as a result.

In this connection it is worth pointing out that in most of Asia the second bronze age, like the first, gave military power to a small body of foreigners who ruled over subject populations by virtue of their control over a sovereign weapon of war—chariots supported by fortified encampments in the first case, cannon backed up by cavalry in the second. It is true that Ming China and Tokugawa Japan departed from this pattern; but when China came under Manchu rule (1644–1912), it too came to be governed by a small ruling stratum of foreign conquerors. Only Japan remained ethnically homogeneous. Hence it is not surprising that the Japanese could call on a sense of national emergency to justify drastic political, technological, and social reforms in the nineteenth century, whereas a pervasive distrust between rulers and ruled hampered other Asian regimes in their efforts to react effectively to the threat of European power.

That threat was not recognized in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries by the more powerful Asian rulers, since, when Europeans first appeared off their coasts, they conformed to already familiar roles as traders and missionaries. Asian governments had long had to cope with the unruliness of merchants and ships’ crews from foreign parts. Even if European ships were more formidable than those which had preceded them in Asian waters, their number was at first so small that established ways of dealing with seafaring strangers seemed to suffice.

To be sure, small trading states were immediately threatened by the naval superiority the newcomers enjoyed. Some of these endangered states appealed for help to the mightiest Moslem ruler of the age: the Ottoman sultan. Turkish authorities responded by building a fleet in the Red Sea to protect the Moslem holy places in the first instance, and secondly to operate in the Indian Ocean, as opportunity might dictate. The Turks also sent artillery experts to distant Sumatra, where they reinforced the resistance capabilities of local Moslem governments. But the Ottoman effort in the Indian Ocean met with only local and limited success because the Mediterranean style of naval warfare, of which they were masters, was becoming obsolescent thanks to the rapid development of cannon.

This calls for a little explanation. Mediterranean naval fighting, from antiquity, turned upon ramming and boarding. This required light, fast, maneuverable war galleys with large crews for rowing and for hand-to-hand combat at sea. Such a force also constituted an army on land whenever the ships were beached and their crews went ashore to besiege a fortress, raid the countryside, or merely to seek fresh water and a good night’s sleep. Then, in the thirteenth century, the invention of all-weather sailing vessels injected a new element into Mediterranean fighting. The new ships, using crossbows in hitherto unprecedented numbers, relied on missiles to keep their foes at a distance. Merchant vessels needed nothing more.

Matters changed far more radically with the development of efficient cannon in the last decades of the fifteenth century. European seamen quickly grasped the idea that the guns which were dramatically revolutionizing land warfare could do the same at sea. Stoutly built all-weather sailing ships of the sort already in use in Atlantic waters could readily be converted into floating gun platforms—comparable in their concentrated firepower to the bastions with which military engineers were simultaneously beginning to protect city walls. Such floating bastions, being readily maneuverable, made missiles decisive offensively as well as defensively. The impact of a cannonade on lightly constructed ships was as catastrophic as the initial impact of the same guns on castle walls; and its effect lasted much longer, since no technical riposte to the supremacy of heavy-gunned ships at sea was discovered until twentieth-century airplanes and submarines came along.

A far-ranging change in naval relationships resulted. Mediterranean galleys, built for speed, were pitifully vulnerable to cannon if they allowed themselves to come within range. So were the merchant ships of the Indian Ocean, whose light construction suited the monsoon winds but made it impossible for local seamen to meet the Europeans on anything like even terms by fitting guns to their own vessels. The recoil of a heavy gun was, after all, almost as destructive to lightly built craft as the impact at the other end of the cannonball’s trajectory.

Cannon, in the forms developed by French and Burgundian gunfounders between 1465 and 1477, were admirably suited for use aboard a stoutly built ship. The only modification required was to design a different kind of gun carriage, capable of absorbing recoil by rolling backwards across the deck, and thus, conveniently, bringing the cannon mouth inboard to allow reloading. Return to firing position required the crew to pull the gun forward with special tackle, since firing inboard risked igniting the ship. But the new guns were so heavy that they had to be carried near the waterline to avoid dangerous topheaviness. This meant they had somehow to fire through the sides of the hull itself. Cutting gunports just above the waterline, and equipping them with stout, waterproof covers that could be secured when no fighting was expected made a formidable broadside compatible with general seaworthiness. As early as 1514 a warship built for King Henry VIII of England pioneered this design. Some seventy years later, Sir John Hawkins lowered the “castles” fore and aft to improve the sailing qualities of Queen Elizabeth’s warships. With these changes, the adaptation of oceangoing vessels to the artillery revolution of the fifteenth century was effectively achieved. Thereafter, European ships could count on crushing superiority in armed encounters with vessels of different design on every ocean of the earth.

Heavy guns, routinely carried by ordinary merchant ships, allowed the amazingly rapid expansion of European dominion over American (beginning 1492) and Asian (beginning 1497) waters. The easy Portuguese success off the port of Diu in India against a far more numerous Moslem fleet (1509) demonstrated decisively the superiority that their long-range (up to 200 yards) weapons gave to European seamen against enemies whose idea of a sea battle was to close, board, and fight it out with hand weapons. As long as cannon-carrying ships could keep their distance, the old-fashioned boarding tactics were utterly unable to cope with flying cannonballs, however inaccurate long-range bombardment may sometimes have been.