1. Arms and Society in Antiquity

1. 2 Kings 19:20–36.

2. G. A. Barton, ed. and trans., Royal Inscriptions of Sumer and Akkad (New Haven, 1929), pp. 109–11.

3. In the words of a contemporary:

Against Kasalla [a neighboring region] he marched, and he turned Kasalla into mounds and heaps of ruins;

he destroyed (the land and left not) enough for a bird to rest thereon.

L. W. King, ed. and trans., Chronicles concerning Early Babylonian Kings (London, 1907), pp. 5–6.

4. Herodotus is of course the basic source for the Persian campaign, but his figures for the size of Xerxes’ forces are hopelessly exaggerated. My understanding of the logistics of Xerxes’ campaign derives primarily from G. B. Grundy, The Great Persian War (London, 1901) and Charles Hignett, Xerxes’ Invasion of Greece (Oxford, 1963).

5. Propitiation of the gods through more splendid ceremonies, and assurance of immortality through more massive tombs, counted as welfare as much as canal and dike construction to extend the area of irrigated land. Such enterprises were all calculated to increase the harvest.

6. A. Heidel, ed. and trans., The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels (Chicago, 1946), tablet III, col. iv, lines 156–67. The Gilgamesh epic is known through fragments of several different versions, all much later than the historic date of Gilgamesh. Still the texts undoubtedly embody archaic elements, reflecting conditions in Sumer near the beginning of civilized development.

7. Ibid., tablet V, col. iv, lines 20–28.

8. In the Far East, however, in the first century B.C. the Chinese empire established a pattern of “tribute trade” with neighboring rulers. Ritual deference was central in this relationship; indeed the Chinese authorities paid dearly in tangible commodities for the ceremonial acknowledgment of their superiority. Yet in another sense the Hsiung-nu and other border folk, in submitting deferentially to the Chinese court rituals, opened themselves to Sinification, paying thereby a high, if intangible, price. Cf. the interesting analysis of this relationship in Yü Ying-shih, Trade and Expansion in Han China: A Study in the Structure of Sino-Barbarian Economic Relations (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1967).

9. Conclusive proof of Xerxes’ time of march is unattainable, but cf. the careful discussion of what a century or more of scholarship has been able to surmise in Hignett, Xerxes’ Invasion of Greece, app. 14, “The Chronology of the Invasion,” pp. 448–57. Herodotus tells us that Xerxes’ army took three months to go from the Hellespont to Athens (8.51.1).

10. The points raised in the balance of this chapter are more extensively discussed in William H. McNeill, The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community (Chicago, 1963).

11. Whether compound bows, which get extra power by facing wood with expansible sinew on one side and by compressible horn on the other, were new with the charioteers or had been known earlier is a disputed point. Yigael Yadin, The Art of Warfare in Biblical Lands in the Light of Archaeological Study, 2 vols. (New York, 1963), 1:57, says that these bows were invented by the Akkadians of Sargon’s era. The basis for this view is a stele representing Naram Sin, Sargon’s grandson and successor, with a bow whose shape resembles that of later compound bows. But how to interpret the curve of a bow recorded in stone is obviously indecisive. On the compound bow and its capacities see W. F. Paterson, “The Archers of Islam,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 9 (1966):69–87; Ralph W. F. Payne-Gallwey, The Crossbow, Medieval and Modern, Military and Sporting: Its Construction, History, and Management (London, 1903), appendix.

12. See, for example, book 16, lines 426 ff. However absurd, Homer’s report may be accurate. The tactics he describes may have been a function of numbers and terrain. To succeed, a chariot charge required a critical mass—enough arrows and charging chariots to break opposing infantry and persuade foot soldiers to flee. But in a land like Greece, where hills abound and fodder for horses is short, chariots had to remain few—too few, perhaps to achieve decisive effect in battle. Yet, like Cadillacs of the recent past, the prestige of the chariot after its victories in the Middle East was such that every local European chieftain was eager to have one, whether or not he could use it effectively in war.

13. Judges 21:25 (Theophile J. Meek, trans.).

14. Men occasionally rode horseback as early as the fourteenth century B.C. This is proved by an Egyptian statuette of the Amarna age, now in the Metropolitan Museum of New York. See photograph in Yadin, Art of Warfare in Biblical Lands, 1:218; another equestrian figure, from the British Museum, of the same age is reproduced, ibid., p. 220. The difficulty of remaining firmly on a horse’s back without saddle or stirrups was, however, very great; and especially so if a man tried to use his hands to pull a bow at the same time—or wield some other kind of weapon. For centuries horseback riding therefore remained unimportant in military engagements, though perhaps specially trained messengers used their horses’ fleetness to deliver information to army commanders. So, at least, Yadin interprets another, later, representation of a cavalryman in an Egyptian bas-relief recording the Battle of Kadesh (1298 B.C.).

15. For photographs of a bas-relief portraying Assyrian paired cavalrymen see Yadin, 2:385.

16. Karl Jettmar, “The Altai before the Turks,” Museum of Far East Antiquities, Stockholm, Bulletin 23 (1951): 154–57.

17. Nevertheless, peasants were uprooted from most of the loess soils of north China at least twice. Mongol raids of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and nomad attacks in the centuries after the collapse of the Han Dynasty in the third century A.D. were severe enough and prolonged enough to destroy agricultural settlement in wide districts of north China—or so imperfect population statistics suggest. Cf. Ping-ti Ho, Studies in the Population of China, 1368–1953 (Cambridge, Mass., 1959), and Hans Bielenstein, “The Census of China during the Period 2–742 A.D.,” Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm, Bulletin 19 (1947): 125–63.

18. Assyrian bas-reliefs show cavalrymen with metaled corselets. As in so many other military matters, the Assyrians seem to have pioneered armored cavalry too.

19. A field planted to alfalfa in effect cost next to nothing, for grain fields had to be fallowed every other year to keep down weeds. By planting alfalfa in the ground instead of leaving the soil fallow, a useful crop could be garnered while bacterial action on the roots of the alfalfa actually enriched the soil with nitrogen and so made subsequent grain harvests richer than would otherwise have been the case. Even the amount of work required to plant and harvest a field of alfalfa was not notably greater than the mid-season plowing necessary for a field left fallow; for it was only thus that the natural seeding of weeds could be interrupted and the soil readied for grain. Alfalfa kept back unwanted weeds almost as well as mid-season plowing simply by shading the soil with its leaves.

20. John W. Eadie, “The Development of Roman Mailed Cavalry,” Journal of Roman Studies 57 (1967): 161–73.

21. This Byzantine policy resembled the way the New Kingdom of Egypt reconciled the superior technology of chariot warfare with Old Kingdom traditions of bureaucratic centralism.

22. On stirrups and knights see Lynn White, Jr., Medieval Technology and Social Change (Oxford, 1962); John Beeler, Warfare in Feudal Europe, 730–1200 (Ithaca, N.Y., 1971), pp. 9–30.

23. Shadowy survival of older command structures had also occurred in the chariot age and facilitated the rebuilding of Iron Age monarchies.

24. James Lee, pending Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago.

25. Cf. the perceptive remarks of Denis Twitchett, “Merchant Trade and Government in Late T’ang,” Asia Major 14 (1968): 63–95, on the role of merchants in China.

26. A rich find of cuneiform tablets from about 1800 B.C. in Anatolia shows merchant colonies from a mother city, Assur, flourishing as part of a trade net that extended from the Persian Gulf northward through Mesopotamia. These ancient Assyrian traders shipped tin eastward and carried textiles manufactured in central Mesopotamia west ward. They appear to have behaved as private capitalists, quite in the spirit of medieval merchants three thousand years later. Family firms exchanged letters: hence the archive. Profits were high—up to 100 percent in a single year, if all went well. Cf. M. T. Larsen, The Old Assyrian City-State and Its Colonies, Studies in Assyriology, vol. 4 (Copenhagen, 1976). Clearly rulers and men of power along the way permitted their donkey caravans to get through, perhaps because of the strategic value of the tin. But the archive is silent about such arrangements. For traders and their role in ancient Mesopotamia generally, see also A. Leo Oppenheim, “A New Look at the Structure of Mesopotamian Society,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 10 (1967): 1–16.

2. The Era of Chinese Predominance, 1000–1500

1. This is the population total suggested by Ping-ti Ho, “An Estimate of the Total Population in Sung-Chin China,” Etudes Song I: Histoire et institutions, ser. 1 (Paris, 1970), p. 52.

2. Stefan Balazs was the great pioneer with his “Beiträge zur Wirtschaftsgeschichte der T’ang Zeit,” Mitteilungen des Seminars für orientalische Sprachen zu Berlin 34 (1931): 21–25; 35 (1932): 27–73, and his later essays gathered in two overlapping collections, Etienne Balazs, Chinese Civilization and Bureaucracy (New Haven, 1964) and La bureaucratie céleste: Recherches sur l’économie et la société de la Chine traditionelle (Paris, 1968). Yoshinobu Shiba, Commerce and Society in Sung China (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1970) offers a sample of recent Japanese scholarship, which also influences the essays collected in John W. Haeger, ed., Crisis and Prosperity in Sung China (Tucson, Ariz., 1975), and a bold effort at synthesis by Mark Elvin, The Pattern of the Chinese Past (Stanford, Calif., 1973). For an interesting attempt to put China’s economic history into the context of contemporary theory of economic “development” see Anthony M. Tang, “China’s Agricultural Legacy,” Economic Development and Cultural Change 28 (1979): 1–22.

3. Robert Hartwell, “Markets, Technology and the Structure of Enterprise in the Development of the Eleventh-Century Chinese Iron and Steel Industry,” Journal of Economic History 26 (1966): 29–58; “A Cycle of Economic Change in Imperial China: Coal and Iron in Northeast China, 750–1350,” Journal of Economic and Social History of the Orient (JESHO), 10 (1967): 103–59; “Financial Expertise, Examinations and the Formulation of Economic Policy in Northern Sung China,” Journal of Asian Studies 30 (1971): 281–314.

4. Joseph Needham, The Development of Iron and Steel Technology in China (London, 1958), p. 18.

5. The use of coal as fuel in ironworking also was of long standing; but the method used to prevent the iron from becoming useless by contamination with sulphur from the coal was to encase the ore to be smelted in cylindrical clay containers. This meant small-scale production and high fuel consumption. Cf. ibid., p. 13, and pl. 11, showing modern craftsmen using such hand-sized crucibles.

6. Hartwell, “Markets, Technology and the Structure of Enterprise,” p. 34. As Hartwell points out, these statistics parallel British output in the early phases of the industrial revolution. As late as 1788, when Britain too had begun to shift to coke fuel for ferrous metallurgy, total iron output in England and Wales was only 76,000 tons, just 60 percent of China’s total seven hundred years earlier!

7. Chinese population estimates encounter this same difficulty, as had long been recognized.

8. Only in Szechuan; elsewhere coinage was copper.

9. Cf. Esson M. Gale, Discourse on Salt and Iron (Leiden, 1931).

10. Iron and steel were used in bridges, pagodas, and statues. Cf. Needham, Iron and Steel Technology, pp. 19–22; Hartwell, “A Cycle of Economic Change,” pp. 123–45; Hartwell, “Markets, Technology and the Structure of Enterprise, pp. 37–39.

11. Hartwell, “Financial Expertise,” p. 304.

12. Yang Lien-sheng, Money and Credit in China: A Short History (Cambridge, Mass., 1952), p. 53. Robert Hartwell, “The Evolution of the Early Northern Sung Monetary System, A.D. 960–1025,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 87 (1967): 280–89. Paper money was, initially, backed by silver. “If there was the slightest impediment in the flow of paper money, the authorities would unload silver and accept paper money as payment for it. If any loss of popular confidence was feared, then not a cash’s worth of the accumulated reserves of gold and silver in the province concerned would be moved elsewhere.” Elvin, Pattern of the Chinese Past, p. 160, translating Li Chien-nung, Sung-Yüan-Ming ching-chi-shih-kao (Peking, 1957), p. 95. A cash was a small coin, punctured in the center and used for larger transactions attached to strings of standard length.

13. Edmund H. Worthy, “Regional Control in the Southern Sung Salt Administration,” in Haeger, Crisis and Prosperity, p. 112.

14. Yang, Money and Credit, p. 18.

15. Yoshinobu Shiba, “Commercialization of Farm Products in the Sung Period,” Acta Asiatica 19 (1970): 77–96; Peter J. Golas, “Rural China in the Song,” Journal of Asian Studies 39 (1980): 295–99.

16. Quoted in Hugh Scogin, “Poor Relief in Northern Sung China,” Oriens extremus 25 (1978): 41.

17. Ting-ch’iao was located in the lower Yangtse region. This passage comes from a local gazetteer, written between 1330 and 1332, quoted from Yoshinobu Shiba, “Urbanization and the Development of Markets on the Lower Yangtse Valley,” in Haeger, Crisis and Prosperity, p. 28. Shiba’s essay admirably connects the commercialization of specific localities with landscape variations (hill vs. flood plain), transport networks, and population growth. Obviously, not all of China was as highly developed as the region of the lower Yangtse valley. But it was what happened in that region and in the lower reaches of the Yellow River plain that set the pace for the new social and economic developments of the eleventh to the fifteenth centuries.

18. Ibid., p. 36, translating Ch’en Fu, Treatise on Agriculture, first printed in 1154.

19. Cf. Etienne Balazs, “Une Carte des centres commerciaux de la Chine à la fin du XIe siècle,” Annales: Economies sociétés, civilisations 12 (1957): 587–93.

20. Shiba, “Urbanization,” p. 43.

21. A phrase attributed to anonymous Confucian literati in a remarkable debate on state economic policy that occurred in 81 B.C. Cf. Gale, Discourse on Salt and Iron, p. 74.

22. Hartwell, “A Cycle of Economic Change,” p. 147.

23. Cf. Herbert Franke, “Siege and Defense of Towns in Medieval China,” in Frank A. Kierman, Jr., and John K. Fairbank, eds., Chinese Ways in Warfare (Cambridge, Mass., 1974), pp. 151–201.

24. Laurence J. C. Ma, Commercial Development and Urban Change in Sung China (960–1279) (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1971), p. 100. An encyclopedia of the Sung period summed up the military policy of the founder of the dynasty as follows: “He comprehended the value of strengthening the root and weakening the branches.” Wang Ying-lin, Yü Hai, cited in Lo Ch’iu-ch’ing, “Pei-sung ping-chih yen-chiu” (The military service of the northern Sung Dynasty), Hsin-ya Hsueh-pao (New Asia Journal), 3 (1957): 180, translated by Hugh Scogin.

25. The risk of military rebellion by border troops had been vividly demonstrated under the Tang when a barbarian general rebelled in 755 and nearly toppled that dynasty from the throne. The rebellion did paralyze the central civilian administration, making the next two hundred years of Chinese history a period of thinly veiled local warlordism. It was in reaction to this experience that Sung military policy was devised soon after the country was (mostly) reunited under an unusually successful warlord, Chao K’uang-yin, the founder of the dynasty. He, in effect, set out to throw down the ladder by which he had ascended to the throne by establishing administrative patterns that would put every conceivable obstacle in the way of armed rebellion by military commanders. On the T’ang revolt cf. Edwin G. Pulleybank, The Background of the Rebellion of An Lu-shan (London, 1955); on Sung military policy see Jacques Gernet, Le monde chinois (Paris, 1972), pp. 272–75; Edward A. Kracke, Jr., Civil Service in Early Sung China, 960–1067 (Cambridge, Mass., 1953), pp. 9–11; Karl Wittfogel and Feng Chia-sheng, History of Chinese Society, Liao, 907–1125 (Philadelphia, 1949), pp. 534–37.

26. For details of the Jürchen conquest, see Jing-shen Tao, The Jürchen in Twelfth Century China: A Study of Sinicization (Seattle and London, 1976), pp. 14–24.

27. No satisfactory account of the development of the crossbow in China seems to exist. A Chinese text, Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yüeh, attributes the invention of the crossbow to a man named Ch’in, from whom the invention passed to three local magnates and from them to Ling, ruler of the state of Ch’u in south central China from 541 to 529 B.C. Archaeological evidence tends to support this dating, for several tombs of the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. contained crossbows. The first notable improvement in crossbow design came in the eleventh century, when Li Ting invented the foot stirrup (about 1068), allowing use of the back and leg muscles for cocking the bow. Correspondingly stronger bows could then be brought into use. I owe these bits of information to personal communications from Steven F. Sagi of the University of Hawaii and Robin Yates of Cambridge University. Published materials seem hopelessly inadequate. Cf. C. M. Wilbur, “History of the Crossbow,” Smithsonian Institution Annual Report, 1936 (Washington, D.C., 1937), pp. 427–38; Michael Loewe, Everyday Life in Early Imperial China (London, 1968), pp. 82–86; Noel Barnard and Sato Tamotsu, Metallurgical Remains of Ancient China (Tokyo, 1975), pp. 116–17. For European crossbows the admirable work by Ralph W. F. Payne-Gallwey, The Crossbow, Medieval and Modern, Military and Sporting: Its Construction, History and Management (London, 1903), offers clear and abundant information, and includes a little on modern Chinese crossbows as well.

28. Corinna Hana, Berichte über die Verteidigung der Stadt Te-an während der Periode K’ai-hsi, 1205–1209 (Wiesbaden, 1970). As we shall see in chapter 3, powerful crossbows checked the expansion of knighthood in the thirteenth century when these weapons became common in Mediterranean Europe. In China, crossbows may have helped to discourage reliance on the Iranian style of heavily armored cavalry, for if a crossbowman could knock even an armored cavalryman off his horse, it made no sense to invest in the heavy horse and the expensive armor that put Iranian barons and European knights at the apex of their respective societies. Heavily armored cavalry, after some three centuries of importance in China, disappeared in the seventh century. It is, however, not certain that Chinese crossbows were powerful enough to penetrate armor before the invention of the foot stirrup in the eleventh century. Cf. Joseph Needham, The Grand Titration: Science and Society in East and West (London, 1969), pp. 168–70.

29. For a literary account of bowmaking and prints showing crossbow artisans at work, see Sung Ying-Hsing, T’ien-Kung K’ai-Wu, translated as Chinese Technology in the 17th Century, by E-tu Zen Sun and S. C. Sun (Univeristy Park, Pa., 1966), pp. 261–67. Weaker bows could be made of simpler material; indeed it was even possible to shape a workable trigger entirely out of wood; but such weapons lacked the power needed to penetrate armor. For an account of nineteenth-century Chinese crossbows made of wood and designed to fire a magazine of arrows at a very rapid rate, see Payne-Gallwey, The Crossbow, pp. 237–42. These weak but ingenious weapons (actually used against British troops in the 1860s) relied on poisoned arrows to make their wounds dangerous.

30. Sergej Aleksandrović Skoljar, “L’artillerie de jet à l’époque Song,” in Françoise Aubin, ed., Etudes Song, ser. 1 (Paris, 1978), pp. 119–42; Joseph Needham, “China’s Trebuchets, Manned and Counter-weighted,” in Bert S. Hall and Delno C. West, eds., On Pre-modern Technology and Science: A Volume of Studies in Honor of Lynn White, Jr. (Malibu, Calif., 1976), pp. 107–38.

31. Joseph Needham, “The Guns of Khaifengfu,” Times Literary Supplement, 11 January 1980; Herbert Franke, “Siege and Defense of Towns in Medieval China,” in Kierman and Fairbank, Chinese Ways in Warfare, pp. 161–79; L. Carrington Goodrich and Feng Chia-sheng, “The Early Development of Firearms in China,” Isis 36 (1946): 114–23; Wang Ling, “On the Invention and Use of Gunpowder in China,” Isis 37 (1947): 160–78.

32. Quoted from Wang Ling, “Gunpowder,” p. 165. According to Wang Ling, the fire arrows in question may have been tipped with gunpowder that exploded on impact.

33. For a detailed account of how machines and men were mobilized to defend a provincial city against the Jürchen see Hana, Berichte iiber die Verteidigung der Stadt Te-an.

34. Kracke, Civil Service in Early Sung China.

35. The quotation and figures for the army’s cost come from Hsiao Ch’i Ch’ing, The Military Establishment of the Yüan Dynasty (Cambridge, Mass., 1978), pp. 6–7.

36. Wolfram Eberhard, “Wang Ko: An Early Industrialist,” Oriens 10 (1957): 248–52, tells this tale.

37. Ma, Commerical Development and Urban Change in Sung China, p. 34. The phrases come from an imperial decree issued in 1137.

38. Ibid., p. 38. Cf. Lo Jung-pang, “Maritime Commerce and Its Relation to the Sung Navy.” JESHO 12 (1969): 61–68.

39. Herbert Franz Schurmann, Economic Structure of the Yüan Dynasty (Cambridge, Mass., 1967), pp. 3–4. Herbert Franke, “Ahmed: Ein Beitrag zur Wirtschaftsgeschichte Chinas unter Qubilai,” Oriens 1 (1948): 222–36, describes the rise and fall of the most spectacularly successful of these outsiders. He was a Moslem born in Transcaucasia who became chief administrator of the salt and other monopolies. Yet the greater scope the Mongols accorded to merchants went along with such an energetic mobilization of shipping for state purposes that Chinese seaborne trade suffered serious setback, according to Lo Jung-pang, “Maritime Commerce,” pp. 57–100.

40. Joseph Needham, Science and Civilization in China (Cambridge, 1971), 4, pt. 3:476.

41. For details of the naval war see Jose Din Ta-san and F. Olesa Muñido, El poder naval chino desde sus origenes hasta la caida de la Dinastía Ming (Barcelona, 1965), pp. 96–98.

42. Needham, Science and Civilization in China 3, pt. 3, sec. 29, “Nautical Technology,” pp. 379–699, constitutes a thorough and persuasive study of Chinese shipbuilding and naval history. My remarks on naval development derive mainly from this work, supplemented by Din Ta-san and Olesa Muñido, El poder naval chino, and by three articles by Lo Jung-pang, “China as a Sea Power,” Far Eastern Quarterly 14 (1955): 489–503; “The Decline of the Early Ming Navy,” Oriens extremus 5 (1958): 149–68; and “Máritime Commerce and Its Relation to the Sung Navy,” JESHO 12 (1969): 57–107.

43. Needham, Science and Civilization in China 4, pt. 3:484.

44. It is possible that Cheng Ho’s first voyage was undertaken to secure China’s sea approaches at a time of an anticipated overland attack by Tamurlane, who died in 1405 while preparing a massive assault on China. For this suggestion see Lo Jung-pang, “Policy Formulation and Decision Making on Issues Reflecting Peace and War,” in Charles O. Hucker, ed., Chinese Government in Ming Times: Seven Studies (New York, 1969), p. 54.

45. For details of how Chinese overseas shipping and trade were financed, and how ships were commanded, controlled, and crewed, see Shiba, Commerce and Society in Sung China, pp. 15–40. For a survey of what Chinese merchants knew about the world beyond the oceans, see Chau Ju-kua, On the Chinese and Arab Trade in the 12th and 13 th Centuries, trans. Friedrich Hirth and W. W. Rockhill (St. Petersburg and Tokyo, 1914).

46. August Toussaint, History of the Indian Ocean (Chicago, 1966), pp. 74–86; Paul Wheatley, The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula before 1500 A.D. (Kuala Lumpur, 1961), pp. 292–320; K. Mori, “The Beginning of Overseas Advance of Japanese Merchant Ships,” Acta Asiatica 23 (1972): 1–24.

47. Lo Jung-pang, “The Decline of the Early Ming Navy,” pp. 149–68; Kuei-sheng Chang, “The Maritime Scene in China at the Dawn of the Great European Discoveries,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 94 (1974): 347–59

48. Cf. John V. G. Mills, ed. and trans., Ma Huan, Ying-yai Sheng-ian: Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores [1433] (Cambridge, 1970), Introduction.

49. For a detailed account of this ill-fated military enterprise see Fredrick W. Mote, “The Tu-mu Incident of 1449,” in Kierman and Fairbank, Chinese Ways in Warfare, pp. 243–72.

50. A memorial written by Fan Chi and quoted by Lo Jung-pang, “The Decline of the Early Ming Navy,” p. 167. For details of this decision to withdraw see Lo Jung-pang, “Policy Formulation and Decision Making,” in Hucker, Chinese Government in Ming Times, pp. 56–60.

51. Prohibition of overseas trade was renewed in 1390, 1394, 1397, 1433, 1449, and 1452 according to Matsui Masato, “The Wo-K’uo Disturbances of the 1550’s,” East Asian Occasional Papers 1 (Asian Studies Program, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, 1969), pp. 97–107.

52. Jitsuzo Kuwabara, “P’u Shou-keng: A Man of the Western Regions,” Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko 7 (1935): 66.

53. On the “Japanese” pirates see Kwan-wai So, Japanese Piracy in Ming China during the 16th Century (Lansing, Mich., 1975); Louis Dermigny, La Chine et I’occident: la commerce a Canton au XVIIIe Steele (Paris, 1964), 1:95–99

54. For examples, admittedly from a later age, see Ping-ti Ho, “Salt Merchants of Yang-chou,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 17 (1954): 130–68.

55. Archibald Lewis, “Maritime Skills in the Indian Ocean, 1368–1500,” JESHO 16 (1973): 254–58, compiled a long list of goods traded.

56. On Malacca see Wheatley, The Golden Khersonese, pp. 306–20.

57. Sung records nicely illustrate how the system worked. In 1144 officials raised import duties to 40 percent of declared value, only to see trade languish and receipts diminish, with the result that in 1164 the old rate of 10 percent was restored. Lo Jung-pang, “Maritime Commerce,” p. 69.

58. My conception of how merchants and rulers interacted along Asia’s southern shores is largely shaped by Niels Steensgaard, The Asian Trade Revolution of the Seventeenth Century: The East India Companies and the Decline of the Caravan Trade (Chicago, 1974), pp. 22–111. Steensgaard describes a situation existing about 1600, and he is concerned primarily with caravan trade; but the strategy of trade and taxation probably did not much alter from early times until after 1600, and rulers’ relations with merchants who traveled overland were not notably different from those who came in ships. The concept of “protection rent” was invented by Frederic Lane, “Economic Consequences of Organized Violence,” Journal of Economic History 18 (1958): 401–17, and his investigations of medieval Italian enterprise in the Mediterranean also provided me with a model for what I believe happened along the shores of the Indian Ocean. Lewis, “Maritime Skills in the Indian Ocean,” pp. 238–64, offers a very suggestive survey of the subject, though he does not raise the question of relations between rulers and merchants directly.

59. Sura IV, 29: “O Believers, consume not your goods between you in vanity, except there be trading by your agreeing together.” Arthur J. Arberry, trans., The Koran Interpreted (London, 1955).

60. This is the central thesis of Stefan Balazs, “Beiträge zur Wirtschaftsgeschichte der T’ang Zeit” (n. 2 above), and of Jacques Gernet, Les aspects économiques du Bouddhisme dans la société chinoise du Ve au Xe siècle (Saigon, 1956).

61. My late colleague, Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam (Chicago, 1974), 2:403–4, made the same suggestion several years ago, with the same lack of evidence to back up the hypothesis.

62. Cf. William H. McNeill, Venice: The Hinge of Europe, 1081–1797 (Chicago, 1974), pp. 1–39.

63. Cf. Archibald R. Lewis, The Northern Seas: Shipping and Commerce in Northern Europe, A.D. 300–1100 (Princeton, 1958).

64. Robert Lopez, Genova Marinara nel Duecento: Benedetto Zaccaria, ammiraglio e mercanti (Messina-Milan, 1933).

65. For the Mediterranean, Robert S. Lopez and Irving W. Raymond, Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean World (New York and London, 1955), is a useful starting place. For the Indian Ocean, Michel Mollat, ed., Sociétés et compagnies de commerce en orient et dans l’océan indien: Actes du huitième colloque internationale d’histoire maritime, Beyrouth, 1966 (Paris, 1970) is the best available summary of what little is known. For China, Shiba, Commerce and Society in Sung China, pp. 15–40. For interesting sidelights on the India trade, and its congruence with Mediterranean patterns, see S. D. Goitein, Studies in Islamic History and Institutions (Leiden, 1968), pp. 329–50.

66. Luc Kwanten, Imperial Nomads: A History of Central Asia, 500–1500 (Philadelphia, 1979), conveniently summarizes the current state of knowledge.

67. Cf. Yü Ying-shih, Trade and Expansion in Han China: A Study in the Structure of Sino-Barbarian Economic Relations (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1967), p. 209 and passim.

68. According to Hsiao Ch’i Ch’ing, The Military Establishment of the Yüan Dynasty, pp. 59–60, between 200,000 and 300,000 shih of grain were delivered annually to Karakorum. A shih weighed 157.89 pounds, or roughly three bushels of millet, two and three-fourths bushels of wheat.

69. Jacques Gernet, le Monde chinois (Paris, 1972), p. 351.

70. On the alliance between pastoralists and city people in Islam see Xavier de Planhol, Les fondements géographiques de l’histoire de l’Islam (Paris, 1968), pp. 21–35. On the phenomenon in Christian Balkan society, see William H. McNeill, The Metamorphosis of Greece since World War II (Chicago, 1978), pp. 43–50.

71. For the Kitan as representative of a new “generation” of nomad society see Gernet, Le monde chinois, p. 308; for Middle Eastern slave soldiers see Patricia Crone, Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity (New York, 1980); Daniel Pipes, Slave Soldiers and Islam: The Genesis of a Military System (New Haven, 1981).

72. Arguments and evidence for this reconstruction of events are presented in William H. McNeill, Plagues and Peoples (New York, 1976), pp. 149–65, 190–96.

73. John E. Woods, The Aqquyunlu: Clan, Confederation, and Empire: A Study in 15thl9th Century Turko-lranian Politics (Minneapolis, 1976), offers a sample of how urban and tribal elements interacted and (usually) allied with one another to form one of the many unstable states into which the realm of Islam divided after A.D. 1000.

74. Cf. S. D. Goitein, “The Rise of the Near Eastern Bourgeoisie in Early Islamic Times,” Journal of World History 3 (1957): 583–604.

75. I am not aware of any scholarly discussion of climate change in the Middle East in these centuries. For Europe see Emmanuel LeRoy Ladurie, Histoire du climat depuis I’an mil (Paris, 1967).

3. The Business of War in Europe, 1000–1600

1. Cf. J. F. Fino, “Notes sur la production de fer et la fabrication des armes en France au moyen âge,” Gladius 3 (1964): 47–66.

2. The rise of knighthood did not produce a submissive, nonviolent peasantry in Europe. Habits of bloodshed were deep-seated, perennially fed by the fact that Europeans raised both pigs and cattle in considerable numbers but had to slaughter all but a small breeding stock each autumn for lack of sufficient winter fodder. Other agricultural regimes, e.g., among the rice-growing farmers of China and India, did not involve annual slaughter of large animals. By contrast, Europeans living north of the Alps learned to take such bloodshed as a normal part of the routine of the year. This may have had a good deal to do with their remarkable readiness to shed human blood and think nothing of it. Cf. the Saga of Olav Trygveson for the primal ferocity of northern Europe. Also Georges Duby, The Early Growth of the European Economy: Warriors and Peasants from the Seventh to the Twelfth Century (London, 1973), pp. 96, 117, 163, 253, and passim.

3. Light cavalry and small scratch plows were cheaper than their west European equivalents and fitted an environment in which seed-harvest ratios were lower than in the more fertile west. The firmness of connection between lord and peasant was less in the east, and ties to a particular set of fields were weaker for nobles and peasants alike because scratch plow cultivation made it comparatively easy to start afresh on new land prepared for cultivation by the age-old technique of slash and burn.

4. The closest parallel from the European past takes us back to classical times when Greek mercenaries responded to a Mediterranean-wide market, both within Greece and beyond its borders. See. H. W. Parkes, Greek Mercenary Soldiers from the Earliest Times to the Battle of Ipsus (Oxford, 1933) for interesting details about the first stages of this development. The rise of Rome, however, meant monopolization of the Mediterranean market for military service after 30 B.C. Victory for the old-fashioned command principle of mobilizing resources for war ensued, and became applicable to peaceable as well as to military affairs after depopulation set in during the third century A.D. It was no accident that the major period of weapons development in the ancient Mediterranean world occurred in the centuries when competing rulers applied commercial principles to the tasks of military mobilization. On the remarkable development of artillery in the Hellenistic age, see E. W. Marsden, Greek and Roman Artillery: Historical Development (Oxford, 1969); Barton C. Hacker, “Greek Catapults and Catapult Technology: Science, Technology, and War in the Ancient World,” Technology and Culture 9 (1968): 34–50; W. W. Tarn, Hellenistic Military and Naval Development (Cambridge, 1930).

5. Cf. William H. McNeill, Venice: The Hinge of Europe (Chicago, 1974), pp. 48–51. The new ships relied mainly on crossbows for defense—probably a critical factor in increasing the prevalence and importance of that weapon in Mediterranean warfare from the eleventh century onwards.

6. No satisfactory account of the techniques of European mining before the sixteenth century seems to exist. Maurice Lombard, Les métaux dans l’ancien monde du Ve au XIe siècle (Paris, 1974) breaks off just when European mining surged ahead. T. A. Richard, Man and Metals (New York, 1932), 2:507–69, has scattered data; Charles Singer, ed., A History of Technology (Oxford, 1956), 2:11–24, marks no advance; John Temple, Mining: An International History (London, 1972) is equally uninformative. The difficulty presumably lies in the fact that mining skills developed on an artisan basis and were not recorded in writing until 1555 when George Bauer’s masterwork was published as Agricola, De re metallica, complete with instructive illustrations of technical procedures. Richard, Singer, and Temple depend entirely on what Agricola has to say for technical matters. Painstaking archaeology will be required before modern scholars can discover when and where technical advances took place before De re metallica suddenly opens up a view of what European miners of the sixteenth century had accomplished.

7. On the shift from town militia to professional soldiery see Michael E. Mallett, Mercenaries and Their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy (London, 1974), pp. 1–51; D. P. Waley, “The Army of the Florentine Republic from the 12th to the 14th Centuries,” in Nicholai Rubenstein, ed., Florentine Studies (London, 1968), pp. 70–108; Charles C. Bayley, War and Society in Renaissance Florence: The “De Militia” of Leonardo Bruni (Toronto, 1961).

8. And had been initiated by hiring Balkan Christians, the so-called “stradioti,” shortly before the venture onto the Italian mainland began. Cf. Freddy Thieret, La Roumanie vénetienne au moyen âge (Paris, 1959), p. 402.

9. These remarks on Italian military organization depend primarily on Mallett’s magnificent book Mercenaries and Their Masters, and his chapter “Venice and Its Condottieri, 1404–54” in John R. Hale, ed., Renaissance Venice (London, 1973), pp. 131–45. Cf. also John R. Hale, “Renaissance Armies and Political Control: The Venetian Proveditorial System, 1509–1529,” Journal of Italian History 2 (1979): 11–31, and Piero Pieri, Il Rinascimento e la crisi militare italiana (Turin, 1952), which offers abundant information but generally endorses the traditionally negative appraisal of mercenary soldiering.

10. Ralph W. F. Payne-Gallwey, The Crossbow, Medieval and Modern, Military and Sporting: Its Construction, History and Management (London, 1903), pp. 62–91 and passim.

11. Cf. L. Carrington Goodrich, “Early Cannon in China,” Isis 55 (1964): 193–95; L. Carrington Goodrich and Feng Chia-sheng, “The Early Development of Firearms in China,” Isis 36 (1946): 114–23; and Joseph Needham, “The Guns of Khaifengfu,” Times Literary Supplement, 11 January 1980. On early guns in Europe innumerable books exist, of which O. F. G. Hogg, Artillery, Its Origin, Heyday, and Decline (London, 1970) is a worthy recent example.

12. Feudal service had already been partially monetized by the fact that after a stated period of time (usually forty days) the lord was expected or required to pay his knights a daily allowance to permit them to remain under arms. Since the English remained in France winter and summer, their arrival put an intolerable strain on traditional patterns of short-term feudal service among the French. Among the English, earlier wars of conquest in Wales and Scotland had already triggered the development of a semiprofessional royal army of mercenaries. On recruitment into English expeditionary forces, see Kenneth Fowler, ed., The Hundred Years War (London, 1971), pp. 78–85; H. J. Hewitt, The Organization of War under Edward III, 1338–62 (Manchester, 1966), pp. 28–49.

13. Cf. the masterful work by Phillipe Contamine, Guerre, état et société à la fin du moyen âge: Etudes sur les armées des rois de France, 1337–1494 (Paris, 1972). On English armies: Hewitt, Organization of War under Edward III, 1338–62; K. B. McFarlane, “War, Economy and Social Change: England and the Hundred Years War,” Past and Present 22 (1962): 3–17; Edward Miller, “War, Taxation and the English Economy in the Late Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Centuries,” in J. M. Winter, ed., War and Economic Development (Cambridge, 1975), pp. 11—31; and the essays in Fowler, The Hundred Years War (n.12 above) are pertinent. For the economic consequences of plunder, cf. Fritz Redlich, De Praeda Militare: Looting and Booty, 1500–1800 (Wiesbaden, 1956), and especially his major work The German Military Enterpriser and His Work Force, 2 vols. (Wiesbaden, 1964), 1:118 and passim. Redlich’s data come from a later time, but the fact that he was trained as an economist and brought an economist’s vocabulary to bear on the phenomena of plunder and mercenary soldiering gives his work a unique value.

14. These figures come from Contamine, Guerre, état et société, pp. 317–18. In 1478 France’s 4,142 “lances” outnumbered Milan’s more than 4 to 1. This offers a rough measure of the way in which the French monarchy had outstripped the Italian city-state scale of war by the close of the fifteenth century. Ibid., p. 200.

15. Cf. Thomas Esper, “The Replacement of the Longbow by Firearms in the English Army,” Technology and Culture 6 (1965): 382–93. Sexual symbolism presumably attached itself to guns from the beginning, and perhaps goes far to explain European artisans’ and rulers’ irrational investment in early firearms. I owe this idea to Barton C. Hacker, who explored parallel psychological drives behind the development of tanks in the interwar decades in “The Military and the Machine: An Analysis of the Controversy over Mechanization in the British Army, 1919–1939” (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 1968). Yet even if this sort of psychological resonance explains otherwise unintelligible behavior, it does not explain why Europeans were especially susceptible. The character of western Europe’s political institutions and the militaristic habits of urban dwellers who manufactured (and paid for) the new guns seem necessary factors in converting psychological drives from mere fantasy into hard metal. Cf. J. R. Hale, “Gunpowder and the Renaissance: An Essay in the History of Ideas,” in Charles H. Carter, ed., From Renaissance to Counter-Reformation: Essays in Honor of Garret Mattingly (London, 1966), pp. 133–34.

16. Theodore A. Wertime, The Coming of the Age of Steel (Leiden, 1961), pp. 67–69; H. R. Schubert, History of the British Iron and Steel Industry from c. 450 B.C. to A.D. 1775 (London, 1957), pp. 164 ff. On the Continent, cast iron cannon actually dated back to the mid-fifteenth century but were often defective, so the cheapness of the metal was counteracted by the frequency of failure. England retained an effective monopoly of serviceable cast iron cannon for half a century, largely because minute chemical trace elements in the ore used by the Sussex ironmasters made the metal less likely to develop flaws as it cooled.

Military demand for cannon slacked off after 1604 when England made peace with Spain (and the Dutch soon followed suit). Growing fuel shortages deepened the economic depression that then set in in Sussex; and two decades later Sweden began casting iron guns of high quality, thanks to the import of Walloon techniques of blast furnace construction and metal casting. Thereafter the Swedes dominated the international market in iron cannon until late in the eighteenth century. Cf. Eli Heckscher, “Un grand chapître de l’histoire de fer: le monopole suèdois,” Annales d’histoire économique et sociale 4 (1932): 127–39.

17. Maurice Daumas, ed., Histoire générale des techniques (Paris, 1965), 2:493.

18. Cf. Léon Louis Schick, Un grand homme d’affaires au début du XVIe siècle: Jacob Fugger (Paris, 1957), pp. 8–27.

19. A convenient shorthand to refer to the territories gathered together by dukes of Burgundy between 1363 and 1477. The Low Countries constituted the richest part of their domains, which, however, extended irregularly southward to the Swiss border. For half a century before the death of Charles the Bold in 1477 the dukes of Burgundy seemed about to reconstitute the kingdom of Lotharingia which had been interposed between France and Germany by the division of the Carolingian empire in 843.

20. Daumas, Histoire générale des techniques, 2:487.

21. Carlo M. Cipolla, Guns, Sails and Empires: Technological Innovation and the Early Phases of European Expansion, 1400–1700 (New York, 1965), pp. 1–73, is by far the most incisive account of early development of artillery in Europe that I have seen. In the nineteenth century, detailed and more or less antiquarian writing on artillery achieved striking refinement with such works as A. Essenwein, Quellen zur Geschichte der Feuerwaffen, 2 vols. (Leipzig, 1877; republished in facsimile, Graz, 1969). On the Burgundian development of artillery, cf. C. Brusten, L’armée bourguignonne de 1455 à 1468 (Brussels, 1954); Claude Gaier, L’industrie et le commerce des armes dans l’anciennes principautés belges du XIIIe à la fin du XVe siècle (Paris, 1973).

22. Christopher Duffy, Siege Warfare: The Fortress in the Early Modern World, 1494–1660 (London, 1979), pp. 8–923.

23. The Hapsburgs shared the Burgundian inheritance with the French in 1477 and thus fell heir directly to the gunfounding capabilities of the Low Countries. For the Ottomans cf. John F. Guilmartin, Jr., Gunpowder and Galleys: Changing Technology and Mediterranean Warfare at Sea in the 16th century (Cambridge, 1974), pp. 255–56.

24. Albrecht Dürer, a pupil of Italians in many things, came back from his Italian travels with an interest in the problem, and has the distinction of having published the first book on fortification ever printed, Etliche Underricht zur Befestigung der Stett Schloss und Flecken (Nuremberg, 1527). This volume is more remarkable for the grandiose works Dürer recommends as protections against cannon than for the practicality of his designs. Cf. Duffy, Siege Warfare, pp. 4–7.

25. Duffy, Siege Warfare, p. 15.

26. John R. Hale, “The Development of the Bastion, 1440–1534,” in John R. Hale, ed., Europe in the Late Middle Ages (Evanston, Ill., 1965), pp. 466–94.

27. Halil Inalcik, “The Socio-Political Effects of the Diffusion of Firearms in the Middle East,” in V.J. Parry and M. E. Yapp, eds., War, Technology and Society in the Middle East (London, 1975), pp. 199–200.

28. Richard Hellie, Enserfment and Military Change in Muscovy (Chicago, 1971), pp. 152–68.

29. Cf. John F. Guilmartin, Jr., Gunpowder and Galleys, for a very penetrating discussion of the rationality behind the conservatism of Mediterranean sea tactics.

30. Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Phillip 11 2 vols. (New York, 1972, 1973).

31. Garret Mattingly, The Defeat of the Spanish Armada (London, 1959), pp. 215–16.

32. Investors received a dividend of 4,700 percent, according to ibid., p. 87.

33. An Admiralty Court judge in 1590 wrote: “Her Majesty hath gotten and saved by these reprisals since they began [five years previously in 1585] above 200,000 pounds.” Kenneth R. Andrews, Elizabethan Privateering, 1585–1603 (Cambridge, 1964), p. 22. Since Elizabeth’s annual income amounted to about £300,000, this was no trivial increment.

34. Other factors, especially tax rates and timber costs, also worked against private Iberian maritime enterprise. Cf. Andrews, Elizabethan Privateering.

35. Richard Bean, “War and the Birth of the Nation State,” Journal of Economic History 33 (1973): 217, calculated that central government tax revenues in western Europe doubled in real, per capita terms between 1450 and 1500, but grew more slowly thereafter.

36. Cf. Richard Ehrenberg, Capital and Finance in the Age of the Renaissance (London, n.d.); Frank J. Smoler, “Resiliency of Enterprise: Economic Crisis and Recovery in the Spanish Netherlands in the early 17th century,” in Carter, From Renaissance to Counter-Reformation, pp. 247–68; Geoffrey Parker, “War and Economic Change: The Economic Costs of the Dutch Revolt,” in Winter, War and Economic Development, pp. 49–71.

37. Cf. Geoffrey Parker, The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567–1659 (Cambridge, 1972), pp. 336–41.

38. On mutiny in the Spanish army see the very enlightening discussion by Geoffrey Parker, “Mutiny in the Spanish Army of Flanders,” Past and Present 58 (1973): 38–52; and his Army of Flanders, chap. 7. Parker counts forty-six separate mutinies by troops in the Spanish service between 1572 and 1607.

39. These figures all come from the admirable book by I. A. A. Thompson, War and Government in Hapsburg Spain, 1550–1620 (London, 1976), pp. 71, 73, 103. For year-by-year figures on the number of soldiers in Spanish service (most of them not Spaniards) in the Netherlands, 1567–1665, see Geoffrey Parker’s equally admirable Army of Flanders, p. 28. Variations from year to year were very great, depending on what operations were planned and what money was available; but after the initial mobilization against the rebels in 1572, the Spanish forces in Flanders usually exceeded 50,000 men.

40. These figures come from Geoffrey Parker, “The ‘Military Revolution’ 1550–1660—a Myth?” Journal of Modern History 48 (1976): 206. Europe’s second army, the French, was only one-third as large as the Spanish in the 1550s.

41. Thompson, War and Government in Hapsburg Spain, p. 72.

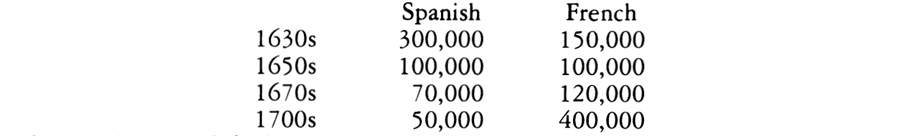

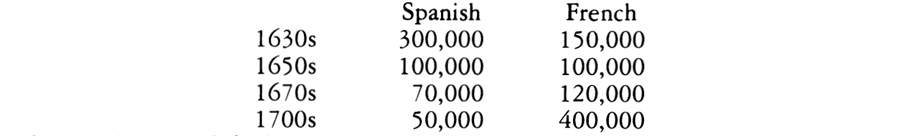

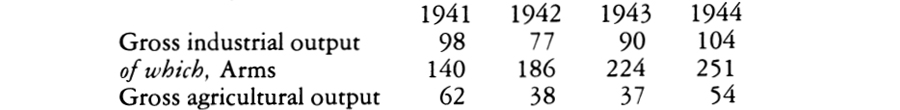

42. According to Parker, “The ‘Military Revolution’ 1550–1660,” p. 206, the numbers of men in the Spanish and French armies varied as follows:

Other armies lagged far behind in size even when technically abreast of French and Spanish. The Dutch army, for example, numbered only about 50,000 in the 1630s and 100,000 in the 1700s. In the north, the Swedes counted 45,000 in the 1630s, 100,000 in the 1700s; Russia, 35,000 in the 1630s, 170,000 in the 1700s. Ibid. Parker’s figure for the French army in the first decade of the eighteenth century is high, however. Other authorities give Louis XIV only 300,000 men in the War of the Spanish Succession. See below, chap. 4.

43. Cf. photos in Kiyoshi Hirai, Feudal Architecture in Japan (New York and Tokyo, 1973). Protection against small-arms fire was, however, more important for the Japanese than protection against cannon. This was because Japanese armies lacked logistical resources for conducting prolonged sieges where cannon would have been decisive; and the national economy, correspondingly, failed to develop a technical base for cannon manufacture on anything approaching the European scale. Samurai ideals, emphasizing hand-to-hand combat, may have inhibited efforts to develop artillery; fuel shortages were also probably important. I owe these suggestions to private correspondence with John F. Guilmartin, Jr.

44. Cf. Jean Le jeune, La formation du capitalism moderne dans la principauté de Liège au XVI siècle (Liège, 1939), p. 181; Claude Gaier, Four Centuries of Liège Gunmaking (London, 1977), pp. 29–31.

4. Advances in Europe’s Art of War, 1600-1750

1. As we have already seen, technologically innovative Spanish soldiers swiftly overthrew the incipient French hegemony by relying on handguns and developing new tactics to take advantage of them. The decisive disaster to the Swiss occurred at the hands of their usual allies, the French, in the Battle of Marignano (1515), when suitably emplaced artillery fired upon the massed pikemen with devastating effect. Cf. Charles Oman, A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages (London, 1898), 2:279. If Charles the Bold had been able to bring his artillery to bear against the Swiss in 1476–77, the history of Europe might have taken a very different turn.

2. On Landesknechten see Eugen von Frauenholz, Das Heereswesen in die Zeit des freien Söldnertums, 2 vols. (Munich, 1936, 1937); Fritz Redlich, The German Military Enterpriser and His Work Force, 2 vols. (Wiesbaden, 1964); Carl Hans Hermann, Deutsche Militärgeschichte: Eine Einführung (Frankfurt, 1966), pp. 58 ff.

3. On Wallenstein see Golo Mann, Wallenstein (Frankfurt am Main, 1971); Francis Watson, Wallenstein: Soldier under Saturn (New York, 1938); G. Livet, La Guerre de Trente Ans (Paris, 1963); Redlich, The German Military Enterpriser, 1:229–336; Fritz Redlich, “Plan for the Establishment of a War Industry in the Imperial Dominion during the Thirty Years War,” Business History Review 38 (1964): 123–26.

4. Bellum se ipse alet is the Latin phrase attributed to the Swedish king. Cf. Michael Roberts, Essays in Swedish History (Minneapolis, 1967), p. 73.

5. Eli Heckscher, “Un grand chapître de l’histoire de fer: le monopole suèdois,” Annales d’histoire économique et sociale 4 (1932): 127–39

6. Cf. Louis André, Michel Le Tellier et Louvois, 2d ed. (Paris, 1943); Louis André, Michel Le Tellier et l’organization de l’armée monarchique (Montpelier, 1906). On Masselini and his administrative reforms, see Michael E. Mallett, Mercenaries and Their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy (London, 1974), pp. 126–27.

7. Translated from Camille Rousset, L’histoire de Louvois, 4 vols. (Paris, 1862–64), 1:209. Garrison regulations settled down to a routine of drill exercises in the presence of an officer twice a week, with the entire garrison parading in battle formation once a month before a high-ranking officer or other important personage. André, Michel Le Tellier, pp. 399–401.

8. Roberts, Essays in Swedish History, p. 219.

9. Aelian was a Greek who wrote a book on tactics in the time of Trajan, when the Roman Empire and its army were at their peak. It was translated into Latin in 1550, and so combined the authority of antiquity with an aura of novelty when Prince Maurice began his military reforms. According to Werner Halbweg, Die Heeresreform der Orianer und die Antike (Berlin, 1941), p. 43, Aelian provided the main inspiration for Maurice’s reforms.

10. The gun had to be loaded with powder, followed by a wad to hold the powder in position; then a ball and a wad to hold the ball in place; then the primer pan had to be filled with a different sort of powder. The lighted match (held in the meanwhile in the left hand) was then affixed to the firing mechanism and the gun was at last ready to be aimed and fired. The match had to be detached from the gun before the cycle could be safely repeated.

11. On Maurice’s reforms, in addition to Halbweg’s previously cited work, see the provocative remarks by M. D. Feld, “Middle Class Society and the Rise of Military Professionalism: The Dutch Army, 1589–1609,” Armed Forces and Society 1 (1975): 419–42.

12. I am not aware of any really perceptive discussion of the psychological and sociological effects of close-order drill on human beings in general or within European armies in particular. My remarks are derived from reflections on personal experience—and surprise at my own response to drill during World War II.

Some military writers of the age hint at the power of drill and its relationship to dancing. Cf. Maurice de Saxe, Reveries on the Art of War, trans. Thomas R. Phillips (Harrisburg, Pa., 1944), pp. 30–31: “Have them march in cadence. There is the whole secret, and it is the military step of the Romans. . . . Everyone has seen people dancing all night. But take a man and make him dance for a quarter of an hour without music, and see if he can bear it. . . .

“I shall be told, perhaps that many men have no ear for music. This is false; movement to music is natural and automatic. I have often noticed while the drums were beating for the colors, that all the soldiers marched in cadence without intention and without realizing it. Nature and instinct did it for them.”

The military music of Christian Europe, incidentally, derived from Ottoman fife and drum corps. These in turn were adaptations of steppe traditions of drumming which had filtered into the Moslem world via dervish communities of young men. But Ottoman troops did not drill incessantly as Christian troops started to do, nor did they march in step, thereby muting the elemental resonance that moving in unison arouses.

13. Jacob de Gheyn, Wapenhandelinghe van Roers, Musquetten ende Spiessen, Achtervolgende de Ordre van Syn Excellentie Maurits, Prince van Orangie (The Hague, 1607). The edition I saw was a facsimile (New York, 1971), with an informative commentary by J. B. Kist appended. According to Kist, Maurice first held a review of his troops, with field maneuvers, in 1592. At that time his battalions numbered 800 men each; later he reduced the size of the battalion—the primary unit of maneuver—to 550 to make it nimbler in the field and easier for a single voice to control. De Gheyn’s book was often pirated subsequently; most significantly by Johann Jacob Wallhausen, Kriegskunst zu Fuss (1614), who used the same copper plates as the original work, but wrote in German.

14. Richard Hellie, Enserfment and Military Change in Muscovy (Chicago, 1971), pp. 187–88.

15. On Ottoman failure to respond to European drill see V. J. Parry, “La manière de combattre,” in V. J. Parry and M. E. Yapp, eds., War, Technology and Society in the Middle East (London, 1975), pp. 218–56.

16. For details see James P. Lawford, Britain’s Army in India from Its Origins to the Conquest of Bengal (London, 1978).

17. Cf. Frauenholz, Das Heereswesen in die Zeit des freien Söldnertums, 1:36–39. Discharged veterans provided key manpower for the Peasants’ War of 1525, for example.

18. In 1479 Louis XI of France disbanded his French infantry forces and made a contract with the Swiss instead. The Swiss reputation as the premier pikemen of Europe undoubtedly influenced this decision; but so did their political distance from French social turmoils. Cf. Phillipe Contamine, Guerre, état et société à la fin du moyen âge: Etudes sur les armées des rois de France, 1337–1494 (Paris, 1972), p. 284. On the use of foreign mercenaries in general see V. G. Kiernan, “Foreign Mercenaries and Absolute Monarchy,” in Trevor Aston, ed., Crisis in Europe, 1360–1660 (New York, 1967), pp. 117–40.

19. The Ottoman Empire competed with the Venetians from the 1590s for the mercenary services of Christian infantrymen from the western Balkans. See Halil Inalcik, “Military and Fiscal Transformation in the Ottoman Empire, 1600–1700” Archivum Ottomanicum 6 (1980). North of the Black Sea, however, technical and geographical conditions favored cavalry for some two centuries after primacy had passed to infantry in west European landscapes and battlefields. The cheap horses available on the steppe allowed mounted Cossacks to play a role in the east analogous to that of the Swiss in the west. Like the Swiss, they became military egalitarians and wavered between alternative foreign employers once their military value had been recognized among neighboring states. In the end the Cossacks affiliated with the Russian tsars but only at the price of betrayal of their earlier egalitarian tradition. Cf. William H. McNeill, Europe’s Steppe Frontier, 1500–1800 (Chicago, 1964).

20. In Islamic lands, similar difficulties had sometimes been met by reducing foreign soldiers to the status of slaves; but a slave soldier, too, was hard to control, and in several Islamic states slave captains seized power in their own right, founding “slave dynasties” in which power passed from slave captain to slave captain instead of from father to son. The Mameluke state of Egypt was the most famous of these; it lasted from the thirteenth to the nineteenth century. On slave soldiery in Islam see David Ayalon, “Preliminary Remarks on the Mamluk Military Institution in Islam,” in Parry and Yapp, War, Technology, and Society in the Middle East, pp. 44–58; Daniel Pipes, Slave Soldiers and Islam (New Haven, 1981); Patricia Crone, Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity (New York, 1980).

21. The psychic force of drill and new routines was such as to make a recruit’s origins and previous experience largely irrelevant to his behavior as a soldier. This deprives studies of class and local origins of enlisted men of more than antiquarian interest, despite the fact that military records sometimes lend themselves admirably to such analysis. French historians, perhaps influenced by Marxism, have been particularly active in this endeavor, without shedding any notable light on what the French army actually did either in war or in peace. The great monument of this genre is A. Corvisier, L’armée française de la fin du XVIIe siècle au ministère de Choiseul, 2 vols. (Paris, 1964).

22. Standardization and routinization, applied to industrial production in the eighteenth century, were pioneered in army administration and supply in the seventeenth. Similar results—sharply enhanced productivity and lowered unit costs—occurred in both cases. This point is argued, perhaps a little too emphatically, in Jacobus A. A. van Doorn, The Soldier and Social Change: Comparative Studies in the History and Sociology of the Military (Beverly Hills, Calif., 1973), pp. 17–33; Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (New York, 1934), pp. 81–106.

23. On the uncertainty surrounding the invention and introduction of the ring bayonet, see David Chandler, The Art of War in the Age of Marlborough (New York, 1976), pp. 67, 83.

24. Matchlocks of Prince Maurice’s day gave way to flintlocks and correspondingly simplified drill by about 1710, at least in the best-managed European armies. Flintlocks had been invented as early as 1615, but were at first too expensive to displace the matchlock, despite a far higher rate of fire (about twice as fast) and superior reliability (ca. 33 percent misfire vs. 50 percent for matchlocks). I take these statistics from Chandler, The Art of War, pp. 76–79

25. A stricter definition reduces the period in which the same pattern prevailed to a mere century: 1730 to 1830. For details of the many minor variations in design, and of the way the Board of Ordnance handled sudden crises when large numbers of muskets had to be procured in short periods of time, see Howard L. Blackmore, British Military Firearms, 1670–1850 (London, 1961).

5. Strains on Europe’s Bureaucratization of Violence, 1700-1789

1. Europe’s population rose from about 118 million in 1700 to 187 million in 1801. The population of England and Wales grew from something like 5.8 million at the beginning of the century to 9.15 million in 1801; and French population rose from about 18 to 26 million between 1715 and 1789. Cf. Jacques Godechot, Les revolutions, 1770–1799 (Paris, 1970), pp. 93–95; Phyllis Deane and W. A. Cole, British Economic Growth, 1688–1959: Trends and Structure, 2d ed. (Cambridge, 1967), p. 103; M. Reinhard and A. Armengaud, Histoire générale de la population mondiale (Paris, 1961), pp. 151–201. A convenient summary of demographers’ opinions about the causes for population surge in the eighteenth century is to be found in Thomas McKeown, R. G. Brown, and R. G. Record, “An Interpretation of the Modern Rise of Population in Europe,” Population Studies 26 (1972): 345–82. Perhaps the most important single factor was an altered incidence of lethal infectious disease; cf. William H. McNeill, Plagues and Peoples (New York, 1976), pp. 240–58.

2. In 1730, Sultan Mahmud I initiated an effort to improve Ottoman defenses by imitating Christian methods. A French renegade, Claude-Alexandre, comte de Bonneval (1675–1747), played the leading role in this effort. He took the name of Achmet Pasha and was appointed commander-in-chief of Rumelia, the highest post in the Ottoman service. Ironically, real military successes against both the Austrians and Russians, 1736–39, did not prevent a sharp reversal of policy after the war. De Bonneval’s ungovernable temper led to his disgrace and imprisonment in 1738 and his removal allowed pious Moslems, who preferred to rely on the will of Allah rather than on newfangled hardware, to return to power. A second abortive effort at modernization was set off by the unexpected appearance of the Russian fleet in the Aegean in 1770. A Frenchified Hungarian, Baron François de Tott (1733–93), was entrusted with emergency powers to block the Dardanelles; then he undertook a more general effort to improve the fortification of the capital and modernize the Ottoman artillery and fleet. When war ended in 1774, however, the energy behind these efforts evaporated. De Tott, who had not been required to accept Islam, as de Bonneval had done, was doubly suspect as a foreigner and an infidel; and the reforms he had introduced withered away to triviality after he returned to France in 1776. On de Bonneval see Albert Vandal, Le pacha Bonneval (Paris, 1885); on de Tott, see his own Mémoires sur les Turcs et les Tartares (Amsterdam, 1784).

3. March states conquered older, smaller polities at least three times in the ancient Near East: Akkad (ca. 2350 B.C.); Assyria (ca. 1000–612 B.C.); and Persia (550–331 B.C.). Mediterranean history offers a similar array of instances: the rise of Macedon (338 B.C.) and then of Rome (168 B.C.) in classical times followed in modern times by the Spanish domination over Italy (by 1557) which we looked at briefly in the preceding chapter. Ancient China (rise of Ch’in, 221 B.C.) and ancient India (rise of Magadha, ca. 321 B.C.) as well as Amerindian Mexico (Aztecs) and Peru (Incas) all seem to exhibit a parallel pattern. This is not surprising. A given level of organization and technique, if applied to a larger territorial base, can be expected to yield greater results. This was often possible on the margins of specially skilled centers of civilization; and whenever a ruler managed to confirm his power over a comparatively vast, marginal territory, the possibility of conquering older centers of wealth and skill with a semibarbarian force organized along civilized lines regularly arose and was often acted on.

4. Cf. François Crouzet, “Angleterre et France au XVIIIe siècle: Essai d’analyze comparée de deux croissances économiques,” Annales: Economies, sociétés, civilisations 21 (1966): 261–63 and passim.

5. On population phenomena in the New World see Nicholas Sanchez-Albornoz, The Population of Latin America (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1974), pp. 104–29; Shelbourne F. Cook and Woodrow W. Borah, Essays in Population History: Mexico and the Caribbean, 2 vols. (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1971, 1974). As subsequently among Polynesians and other island dwellers of the Pacific, the drastic population die-off that followed initial contacts with white men was due mainly to exposure to imported infections.

6. The Royal Navy, for example, was chronically short of funds in Samuel Pepys’ time, whereas by the early decades of the eighteenth century, the financial expedients—postponement of payment and laying up of ships for part of the year which had been common practice in the late seventeenth century—ceased to be necessary. Cf. Daniel A. Baugh, British Naval Administration in the Age of Walpole (Princeton, 1965), p. 496 and passim; Robert G. Albion, Forests and Sea Power: The Timber Problem of the Royal Navy, 1652–1862 (Cambridge, Mass., 1926), p. 66. For parallel improvement in the punctuality of French army pay and tightening of financial administration in the eighteenth century see A. Corvisier, L’armée française de la fin du XVIIe siècle au ministère de Choiseul: le Soldat (Paris, 1964), 2:822–24; Lee Kennett, The French Armies in the Seven Years War (Durham, N.C., 1967), p. 95.

7. Cf. James P. Lawford, Britain’s Army in India, from its Origins to the Conquest of Bengal (London, 1978). At the Battle of Plassey (1757) Robert Clive commanded 784 European soldiers, 10 field guns, and about 2,100 Indians trained and equipped according to European methods. He routed an army of some 50,000. Cf. Mark Bence-Jones, Clive of India (New York, 1974), pp. 133–43.

8. Cf. the summing up of the impact of the slave trade on Africa in Paul Bohannan and Philip Curtin, Africa and Africans (New York, 1971), pp. 273–76.

9. For an account of these struggles, see William H. McNeill, Europe’s Steppe Frontier, 1500–1800 (Chicago, 1964), pp. 126–221.

10. Cf. Anton Zottman, Die Wirtschaftspolitik Friedrichs des Grossen mit besondere Berücksichtigung der Kriegswirtschaft (Leipzig, 1937); W. O. Henderson, Studies in the Economic Policy of Frederick the Great (London, 1963).

11. Cf. Otto Büsch, Militarsystem und Sozialleben im alten Preussen (Berlin, 1962), pp. 77–99 and passim; Herbert Rosinski, The German Army (New York, 1966), pp. 21–26.

12. Naval technique was harder to master, and the Russian navy that sailed into the Mediterranean in 1770 to attack the Turks was not really up to French or British standards, though it overwhelmed the Turkish navy easily enough. By 1790, moreover, the Russian navy had won secure mastery among Baltic powers by outclassing the Swedes permanently. Cf. Nestor Monasterev and Serge Terestchenko, Histoire de la marine russe (Paris, 1932), pp. 75–80; Donald W. Mitchell, A History of Russian and Soviet Sea Power (New York, 1974), pp. 16–102.

13. Maurice de Saxe held that no general could effectively control more than 40,000 men in the field. Cf. Eugène Carrias, La pensée militaire française (Paris, n.d.), p. 170. Jacques-Antoine Hypolite de Guibert, Essai générale de tactique, in 1772 fixed 50,000 as the ideal size of an army, and 70,000 as an absolute ceiling. Only so, he believed, could real field mobility be sustained. Cf. Robert A. Quimby, The Background of Napoleonic Warfare: The Theory of Military Tactics in 18th Century France, Columbia University Studies in the Social Sciences, no. 596 (New York, 1957), p. 164.

14. Christopher Duffy, The Army of Frederick the Great (Newton Abbot, 1974), pp. 135–36. For French supply limitations see Kennett, French Armies in the Seven Years War, pp. 100–111. For a general overview, Martin L. van Creveld, Supplying War: Logistics from Wallenstein to Patton (Cambridge, 1977) also offers interesting data.

15. According to an official reckoning made soon after the Seven Years War ended, only 13 percent of Prussia’s total expenditure in that war went to pay for materiel; and weapons, powder, and lead, together, required a mere 1 percent. Paul Rehfeld, “Die preussische Rüstungsindustrie unter Friedrich dem Grossen,” Forschungen zür brandenburgischen und preussischen Geschichte 55 (1944): 30.

16. Violet Barbour, Capitalism in Amsterdam in the 17th Century, reprint (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1963), pp. 36–42; J. Yerneaux, La métallurgie liègeoise et son expansion au XVIIe siècle (Liège, 1939); Claude Gaier, Four Centuries of Liège Gunmaking (London, 1977).

17. I have been unable to find a copy of A. Dolleczeck, Geschichte der österreichischen Artillerie (Vienna, 1887) for details.

18. Use of contour lines to indicate slopes was a critical invention for making maps useful to military commanders. Symbols for marshes and other obstacles to cross-country movement were also important but far easier to devise. Topographic contour lines seem to have been first proposed in 1777 by a French lieutenant of engineers, J. B. Meusnier; but use of lines to show water depths was far older, dating back among the Dutch as far as 1584. Scarcity of data delayed resort to contour lines, which became standard on small-scale maps only after about 1810 when improved surveying instruments made gathering data far easier and more rapid. Cf. François de Dainville, “From the Depth to the Heights,” Surveying and Mapping 30 (1970): 389–403; Pierre Chalmin, “La querelle des Bleus et des Rouges dans l’artillerie française à la fin du XVIIIe siècle,” Revue d’histoire économique et sociale 46 (1968): 481 ff.

19. Dallas D. Irvine, “The Origins of Capital Staffs,” Journal of Modern History 10 (1938): 166–68; Carrias, La pensée militaire française, pp. 176 ff.

20. Stephen T. Ross, “The Development of the Combat Division in Eighteenth Century French Armies,” French Historical Studies 1 (1965): 84–94.

21. Quoted from Geoffrey Symcox, ed., War, Diplomacy and Imperialism, 1618–1763 (London, 1974), p. 194. Cf. also Duffy, The Army of Frederick the Great, p. 134.

22. Baron Vom Stein as a relatively junior Prussian official canalized the Ruhr River, for example, in the hope of expanding coal production. Cf. W. O. Henderson, The State and the Industrial Revolution in Prussia, 1740–1870 (Liverpool, 1958), pp. 20–41.

23. By using crushed stones of different sizes to form three distinct layers, a French engineer named Pierre Trésaguet developed a relatively cheap way to build an all-weather road. His methods were widely used in France after 1764; other European countries followed suit as far east as Russia, where a road between Moscow and St. Petersburg was built on Tresaguet’s principles. In Great Britain John Loudon McAdam became interested in the problems of road building in the 1790s and developed a very similar method for making durable road surfaces. McAdam used only one size of crushed rock, thus simplifying procedures. Cf. Gösta E. Sandström, Man the Builder (New York, 1970), pp. 200–201; Roy Devereux, The Colossus of Roads: A Life of John Loudon McAdam (New York, 1936).

24. Cf. Emile G. Leonard, L’armée et ses problèmes au XVIIIe siècle (Paris, 1958); Louis Mention, Le comte de Saint-Germain et ses réformes, 1775–1777 (Paris, 1884); Albert Latreille, L’armée et la nation à la fin de l’ancien régime: les derniers ministres de guerre de la monarchie (Paris, 1914); Jean Lambert Alphonse Colin, L’infanterie au XVIIIe siècle: La tactique (Paris, 1907).

25. Great Britain set the fashion in 1757. Cf. Rex Whitworth, Field Marshal Lord Ligonier: A Story of the British Army, 1702–1770 (Oxford, 1958), p. 218. The United States did the same by importing Baron von Steuben to drill the Continental Army in 1777.

26. On the tactical debate, cf. Colin, L’infanterie au XVIIIe Siéecle; Mention, Le comte de Saint-Germain, pp. 187–210; Quimby, The Background of Napoleonic Warfare; Robert R. Palmer, “Frederick the Great, Guibert, Bülow: From Dynastic to National War,” in Edward M. Earle, ed., Makers of Modern Strategy (Princeton, 1943), pp. 49–74; Henry Spenser Wilkinson, The French Army before Napoleon (Oxford, 1915). For tactics and enclosure see Richard Glover, Peninsular Preparation: The Reform of the British Army, 1795–1804 (Cambridge, 1963), p. 124. For skirmishing and light infantry see Gunther Rothenberg, The Military Border in Croatia, 1740–1881: A Study of an Imperial Institution (Chicago, 1966), pp. 18–39 and passim; Peter Paret, Yorck and the Era of Prussian Reform, 1807–1815 (Princeton, 1966), pp. 24–42.

27. Several thousand breech-loading muskets were manufactured, but when the breech mechanism proved faulty, the inventor committed suicide, according to Kennett, The French Armies in the Seven Years War, pp. 116, 140.

28. After 1794, when the French annexed Liege, gunmakers of that city, the most practiced of all Europe, were compelled to upgrade their performance by the new French inspectors. For details see Gaier, Four Centuries of Liége Gunmaking, pp. 95 ff.

29. Grande Encyclopédie, s.v. Maritz, Jean; P. M. J. Conturie, Histoire de la fonderie nationale de Ruelle, 1750–1940, et des anciennes fonderies de canons de fer de la Marine (Paris, 1951), pp. 128–35.

30. In 1763 the Prussians imported a Dutch artificer to set up cannon-boring machines at the armaments works in Spandau. He was captured by the Russians when they occupied Berlin in 1760 and persuaded to perform the same service for them at Tula. Cf. Rehfeld, “Die preussische Rüstungsindustrie unter Friedrich dem Grossen,” p. 11.

31. Clive Trebilcock, “Spin-off in British Economic History: Armaments and Industry, 1760–1914,” Economic History Review 22 (1969): 477.

32. Very instructive diagrams illustrating how late eighteenth-century artillery worked may be found in B. P. Hughes, Firepower Weapons’ Effectiveness on the Battlefield, 1630–1850 (London, 1974), pp. 15–36.

33. E. W. Marsden, Greek and Roman Artillery: Historical Development (Oxford, 1969), pp. 48–49, says that the primary loci of invention were the court of Dionysios I of Syracuse (399 B.C.) and that of Ptolemy II of Egypt (285–246 B.C.).

34. Among other factors, this “noble reaction” may have reflected population growth. With more younger sons to look after, noble families presumably looked more eagerly for army commissions and resented untitled upstarts all the more warmly.

35. On Frederick’s motivation see Gordon Craig, The Politics of the Prussian Army, 1640–1945 (Oxford, 1956), p. 16. On the aristocratic reaction in the French army see Kennett, The French Armies in the Seven Years War, p. 143; David Bien, “La réaction aristocratique avant 1789: L’example de l’armée,” Annales: Economies, sociétés, civilisations 29 (1974): 23–48, 505–34; David Bien, “The Army in the French Enlightenment: Reform, Reaction and Revolution,” Past and Present, no. 85 (1979): 68–98.

36. I depend heavily on Howard Rosen, “The Système Gribeauval: A Study of Technological Change and Institutional Development in Eighteenth Century France” (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 1981). Some of his insights are available in his “Le système Gribeauval et la guerre moderne,” Revue historique des armées 1–2 (1975): 29–36. For details see Jean Baptiste Brunet, L’artillerie française au XVIIIe síecle (Paris, 1906); and for the internal struggle in the army, Chalmin, “La querelle des Bleus et des Rouges,” pp. 490–505.

37. In 1791 the French field artillery totaled only 1,300 guns according to Gunther Rothenberg, The Art of Warfare in the Age of Napoleon (Bloomington, Ind., 1978), p. 122.

38. Charles K. Hyde, Technological Change and the British Iron Industry, 1700–1870 (Princeton, 1977), pp. 194–96.

39. Bertrand Gille, Les origines de la grande industrie métallurgique en France (Paris, 1947), pp. 131–35 and passim; Conturie, Histoire de la fonderie nationale de Ruelle, pp. 248–80; Theodore Wertime, The Coming of Age of Steel (Leiden, 1961), pp. 131–32; Joseph Antoine Roy, Histoire de la famille Schneider et du Creusot (Paris, 1962), pp. 11–15.

40. Gaier, Four Centuries of Liège Gunmaking, p. 60.

41. Most of the labor needed was provided by ascribing serfs to the new enterprises. Much of the work was done in winter when there was nothing to do in the fields; hence the extra burden on the serfs cut into their agricultural productivity only slightly. By generous resort to compulsion, in other words, the Russian government instituted a far more efficient distribution of labor through the year—and acquired an iron industry, basic for armaments, for little more than the cost of supporting supervisory personnel and a few imported master workmen. Cf. James Mavor, An Economic History of Russia, 2d ed. (New York, 1925), 1:437–38. By 1715 Peter’s factories had produced no fewer than 13,000 cannons; in 1720 the annual production of muskets reached 20,000—fully equivalent to French production. Cf. Arcadius Kahan, “Continuity in Economic Activity and Policy during the Post-Petrine Period in Russia,” in William L. Blackwell, ed., Russian Economic Development from Peter the Great to Stalin (New York, 1974), p. 57.

42. See above, p. 122.

43. W. O. Henderson, Studies in the Economic Policy of Frederick the Great (London, 1963), p. 6.

44. Trebilcock, “Spin-off in British Economic History,” p. 477.