Intensified Military-Industrial Interaction, 1884-1914

Just as the industrialization of war can be dated to the 1840s, when railroads and semiautomated mass production together with Prussian breech-loaders and French efforts to exploit steam to the detriment of British naval supremacy began to transform preexisting military establishments, so, too, one can date the intensification of interaction between the industrial and military sectors of European society to a naval scare promulgated in Great Britain in 1884. A clever journalist, W. T. Stead, and an ambitious naval officer, Captain John Arbuthnot Fisher, were the protagonists of this affair, though other men also played a part in manipulating British public opinion from behind the scenes.

Decay of Britain’s Strategic Position

Their success depended on the fundamental fact that British strategic security underwent systematic erosion from the 1870s onward. At bottom lay the diffusion of industrial techniques from the British Isles to other lands. This process went into high gear from about 1850, as Germany and the United States began to compete with, and in some lines of production to excel, British capacities and skill. In the narrower field of naval armament, too, Britain’s superiority was endangered by the export of high technology to other navies. Private shipyards and armament manufacturers based in Britain played an active role in this process. It was, indeed, only on the strength of foreign sales that Armstrong and other British firms were able to stay in business after the decision of 1864 had entrusted the production of artillery for the British services to the Woolwich arsenal. But when, in 1882, Armstrong’s built a cruiser for Chile, fast enough to outrun all existing capital ships, yet heavily enough gunned to overpower any lesser target, their technical expertise and readiness to sell to any comer who could pay the price began to bring British naval security into question.1

Swift cruisers were particularly menacing to Britain at a time when the nation had come to depend on food coming from across the Atlantic. From the mid-1870s, cheaper transportation made it possible to ship wheat and other foodstuffs to Liverpool and London from the distant plains of North America (and soon also from Argentina and Australia) at prices below those which British farmers could match. As a result, in the absence of tariffs of the kind that protected other European nations from the full force of overseas agricultural competition, crop farming in Great Britain decayed drastically.2 Cheaper bread for consumers, however beneficial to the urban working classes, also meant a radically increased vulnerability. By the 1880s, when 65 percent of Britain’s grain came from overseas, a fleet of enemy cruisers capable of intercepting grain shipments from the other side of the Atlantic could be expected to bring Great Britain face to face with starvation in a matter of months.

This possibility invited French politicians and naval officers to renew their long-standing rivalry with Britain at sea. A group of naval theorists, the so-called jeune école, argued that specialized gunboats for shore bombardment, plus fast cruisers and even faster torpedo boats, were all that France needed to nullify Britain’s naval preeminence. Such vessels had the enormous attraction of being cheap. One armored warship cost as much as sixty torpedo boats; yet one torpedo could sink any existing warship if its warhead hit below the water line. After the French disaster of 1870–71, reequipment of the army had to take precedence. Hence, a plan that promised to diminish the cost of the navy and still compel British warships to withdraw from the Mediterrannean and retire from the Atlantic coasts of France seemed irresistible. Accordingly, in 1881, the Chamber of Deputies voted funds for seventy torpedo boats and halted construction of armored warships. Five years later, when the protagonist of the jeune école, Admiral H. L. T. Aube, became minister of marine (1886–87), he persuaded the Chamber to approve a program for constructing fourteen commerce-raiding cruisers and an additional one hundred torpedo boats. Although battleship admirals continued to exist in France and indeed regained ascendancy over the French navy in 1887, it certainly seemed by the mid-1880s that Britain’s traditional rival had pinned its faith on a radically new weapons system for close-in operations, while falling back on the age-old strategy of commerce-raiding for action at longer distances.3

Such a strategy seemed genuinely threatening to the small group of technically minded British officers who had followed the development of self-propelled torpedos since their invention at Fiume in 1866 by a British emigrant, Robert Whitehead.4 Small, fast torpedo boats of the sort the French proposed to build had little to fear from existing capital ships in 1881. British warships carried ponderous muzzle-loaders, weighing up to eighty tons. Such monsters might have a devastating effect when fired at stationary objects from close range. That was what they had been designed to do, on the assumption that future naval battles would be fought yardarm to yardarm, as in Nelson’s day. But their slow rate of fire and inaccuracy of aim at long ranges meant that fast, maneuverable boats could dart in, release their torpedoes, and be off and away before the Royal Navy’s guns could catch up with such quick-moving targets. In short, Goliath confronted David over again—this time on the sea.

Torpedoes, lethal to armored ships at ranges of 500 to 600 yards, were bad enough, but the embarrassments of the Royal Navy were rendered even more acute by a simultaneous revolution in gunnery which made muzzle-loading hopelessly inefficient. The most important change was in the propellant. By shaping grains of powder with interior hollows so that each grain could burn simultaneously from inside out as well as from outside in, it proved possible to equalize the rate of chemical change that occurred within a gun barrel from first ignition to the end of the burn. This improvement, mainly the work of an American army officer, Thomas J. Rodman (d. 1871), was combined in the 1880s with the invention of new nitrocellulose explosives (here the French took the lead) to produce much more powerful, smokeless propellants.

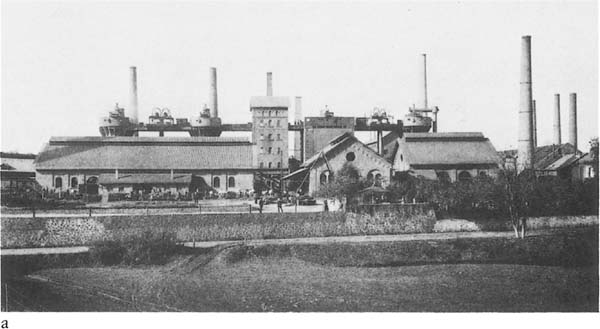

The sustained push that a well-regulated explosion could communicate to a projectile increased muzzle velocities very greatly. It also made longer gun barrels necessary, since the expanding gases of the regulated explosion could continue to accelerate the projectile for a far longer time than had been possible when a sharp initial impetus petered out as the powder grains burned down to nothingness, diminishing the rate of gas generation as the burning surfaces shrank in area. Longer barrels, in turn, made muzzle-loading impossible; and in 1879 the British officially decided that the navy had to have breech-loading guns. What finally persuaded the Admiralty that muzzle-loaders were hopeless was Krupp’s spectacular demonstration of what his big guns could do. He set up a special firing range for the purpose at Meppen (see plate b on p. 266) and in 1878 and 1879 conducted a series of test firings that showed foreign and German observers, invited as potential customers, how vastly superior long-barreled, breech-loading steel guns had become.5

Decision to abandon muzzle-loaders, the sole form of gun approved by the British Board of Ordnance since 1864, presented the Woolwich arsenal with a crisis it was ill prepared to meet. Conversion to breech-loading was expensive and difficult in itself; but costs were enormously increased by the fact that simultaneously the arsenal would have to convert from wrought iron to steel as the basic gunmetal. This required a fundamentally different plant from anything Woolwich had in hand. No matter how fast changes were made, waiting for officials of the arsenal and of the Board of Ordnance to take the necessary steps to convert their establishment to the new requirements was bound to strain the navy’s patience.

Steel Technology and Mass Production of Armaments

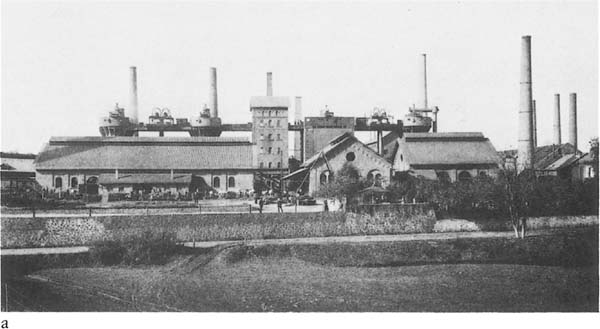

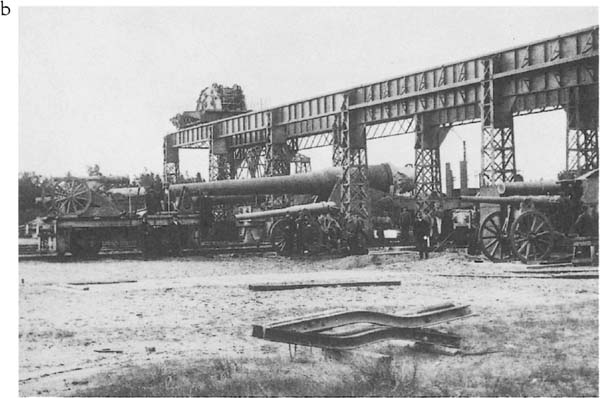

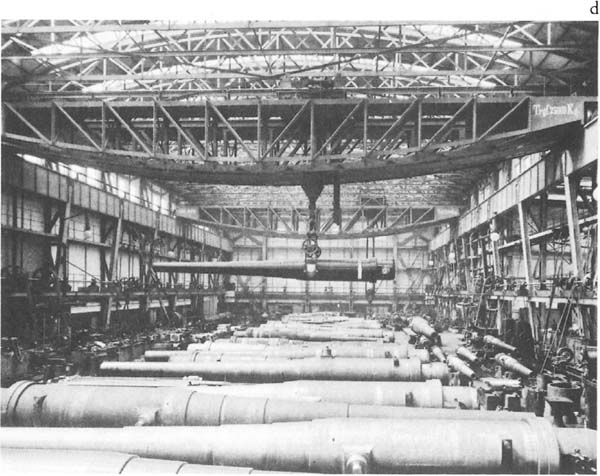

These four photographs show how the firm of Krupp used a head start in steel technology to develop armaments production on a really large scale by the 1890s. The exterior views show (a) blast furnaces where the steel was smelted and (b) the firing range at Meppen where finished guns were tested. The interior views show (c) a machine shop for making gun carriage parts and (d) the shop where gun tubes were given their final machining, inside and out. These photographs formed part of a promotional collection distributed by the firm in 1892.

Reproduced from copies in the University of Chicago Library.

Long-standing army-navy frictions here came into play, for the Board of Ordnance was under army control and responded sluggishly to demands and initiatives coming from the navy. Or so it seemed to naval gunnery officers. In particular, they chafed at the fact that in the years 1881–87 the board authorized only one-third of the expenditure necessary to meet the navy’s program for conversion to breech-loading.6 Such a pace, however revolutionary in itself, seemed wholly inadequate at a time when the French and Germans as well as private gun manufacturers in England were already turning out steel guns that made all the Royal Navy’s existing armament hopelessly obsolete.

Bureaucratic infighting against cheeseparing army officers and unsympathetic arsenal officials seemed an inadequate response to such a critical technical situation. This was what persuaded Captain John Fisher to leak information surreptitiously to the journalist W. T. Stead, with the knowledge that he intended to publish a series of inflammatory articles in the Pall Mall Gazette. The first broadside of the campaign came in September 1884 in the form of an article entitled “The Truth about the Navy,” portentously attributed to “One Who Knows the Facts.” It provoked widespread concern, for it argued, with abundant substantiating detail, that “the truth about the Navy is that our naval supremacy has almost ceased to exist.”7 Other articles followed, climaxing in a detailed account of “What Ought to Be Done for the Navy.” This article appeared on 13 November, shortly after Parliament had reconvened and two weeks before the government got round to responding to the agitation which had swept the country in the wake of the Pall Mall Gazette revelations. The official response was to recommend an increase in naval appropriations of £5.5 million, to be spread over five years’ time. Since the regular appropriation for the navy in 1883 was £10.3 million, this increase, unsatisfactory though it seemed to “One Who Knows the Facts,”8 represented a very considerable victory for the alarmists.

By going public, even if surreptitiously, Fisher had forced decisions that the Liberal government and indeed Fisher’s own naval superiors had been loath to make. The First Sea Lord of the time, Sir Astley Cooper Key, did not approve of such tactics. Indeed, he detested public agitation and distrusted the stategy of increasing naval appropriations dramatically, believing that such a policy would merely provoke other nations to increase their naval expenditures, thus hastening instead of heading off the decline of British naval preponderance.9 As the senior officer of the navy he held that his proper role was to do the best he could with what the government of the day provided in the way of funds. Naval discipline forbade entry into the political process by which such sums were determined. But Fisher was prepared to violate this long-standing code to get his way, impelled partly by personal ambition and partly by a sense of technological urgency which more senior naval officers, immersed in paper work, did not share.

Emergence of the Military-Industrial Complex in Great Britain

Needless to say, Fisher did not act alone. The year 1884 was a time of depression. Idle shipyards were eager for work and journalists did not hesitate to point out that “it might be possible at the present time to kill two birds with one stone—to find ships for our fleet and employment for starving artisans by applying to private dockyards for aid which the Government yards cannot supply.”10 A question in Parliament raised the issue of aid to the unemployed on 25 October, as the government prepared its revised naval estimates; and when the First Lord of the Admiralty disclosed his supplementary program to the House of Lords he declared: “if we are to spend money on the increase of the Navy, it is desirable in consequence of the stagnation in the great shipbuilding yards of this country, that the extra expenditure should go . . . to increase the work by contract in the private yards.”11

In earlier decades, when Parliament had represented property owners and taxpayers, a depression of trade could be counted on to provoke a demand for corresponding reduction in government expenditure. But just two weeks before that upward revision of the naval estimates in 1884, William E. Gladstone’s Liberal government brought in a bill that widened the franchise substantially. Thereafter, the income tax affected only a small proportion of the electorate.12 On the other hand, no parliament could long resist pressures from unemployed voters, backed up by entrepreneurs eager for government contracts.

The new suffrage, therefore, altered the dynamics of politics. Trade depressions, instead of making costly naval bills more difficult to get through Parliament, made extra expenditures more urgent and attractive than in times of prosperity. Arms contracts, after all, could restore both wages and profits and strengthen Britain’s international position, all at the same time. Taxpayers’ reluctance to pay for it all was no longer decisive in politics, especially since more and more voters came to believe that the rich could and should be made to foot the bill.13

This vague and general, yet decisive, realignment of political and economic interests achieved a cutting edge when a handful of technically proficient naval officers inaugurated intimate collaboration with private manufacturers of arms. Captain Fisher played a key role in this change too. In 1883 he had become commander of the naval gunnery school at Portsmouth—the vantage point from which he launched his venture into high politics in 1884. Being responsible for improving naval gunnery, Fisher made it his business to find out all he could about every available model of big gun, including those being manufactured privately. He believed fervently in competition, and his idea in 1884 was to stimulate rivalry between the Woolwich arsenal and private manufacturers in order to assure an optimal result for the navy.

In practice, however, Fisher’s ideal was not realized. The Woolwich arsenal never got the necessary plant to allow it to compete with private firms on anything like equal terms. Ironically, Fisher’s own actions and characteristic impatience with the bureaucratic delays that army officers interposed between his wishes and their realization at the arsenal helped to assure this result. What happened was this: in 1886, when Fisher became director of naval ordnance, he demanded and was accorded the legal right to purchase from private firms any article that the arsenal could not supply quickly or more cheaply. Though no one realized it at the time, this decision soon gave private arms makers an effective monopoly on the manufacture of naval heavy weapons. The reason was simple. Woolwich never caught up with the grandiose scale of capital investment needed to turn out giant steel guns, turrets, and other complicated devices with which warships came to be armed. Armstrong, on the other hand, recognized immediately after Krupp’s demonstrations of 1878 and 1879 that to compete successfully his firm must at once install the machinery needed to produce large steel breech-loaders. Sir William therefore reacted to Krupp’s threatened invasion of a field in which he had hitherto held undisputed pride of place—the building of big guns for coast artillery and naval use—by investing in a brand new steel mill and ship yard.14 By 1886, therefore, Armstrong was ready and eager to add the Royal Navy to his already distinguished list of foreign customers at a time when Woolwich had only begun to convert to the manufacture of breech-loaders.

For the next thirty years the gap proved quite unbridgeable because of economies of scale. It had long been true that international sales were needed to keep gunmaking capital equipment in continual—or nearly continual—use. Such a regime cheapened production drastically, which was why Liège had played such a dominating role in the European gun trade between the 15th and 19th centuries. Still, in the course of the eighteenth century, Europe’s leading states all set up arsenals where guncasting machinery stood idle most of the time. Only so could they enjoy full sovereign power over the manufacture of their artillery. Then in the middle years of the nineteenth century Prussia, the poorest of the great powers, and Russia, the least industrialized, had supplemented arsenal production with purchases from Krupp. But in France and Britain (with the exception of William Armstrong’s years of official recognition, 1859–63) state arsenals retained their official monopoly until the 1880s. Woolwich had invested in new machinery for producing larger and larger wrought iron guns for the Royal Navy ever since the 1860s. But the shift to steel escalated costs so suddenly and drastically that the responsible authorities balked at installing the necessary new facilities at Woolwich.

If they had done so, a very expensive capital plant would have stood idle much of the time, because the demands of the Royal Navy did not suffice to keep such an installation busy—or anything near. International sales, of the kind Krupp and Armstrong had learned to thrive on, were the only way in which a new capital plant could come close to full utilization. This meant, in turn, that arsenal costs of production would certainly exceed those of private companies so long as Woolwich only served the British government.

Thus the ground rules agreed to in 1886 had the effect of allowing Armstrong and, after 1888, Vickers as well, to undercut the arsenal systematically. Woolwich simply could not compete; and in fact the officers in charge never wanted and never got the enormous expansion of capital plant that would have been needed to keep up with the explosive pace of technical change resulting from the new form of naval-industrial collaboration that prevailed throughout the thirty years between 1884 and 1914.

Woolwich and the Royal Naval Dockyards continued to do a great deal of work for the navy,15 but they did not, as a rule, introduce important innovation. Woolwich did sometimes take on new weapons after initial development work had been done elsewhere. This was the case with self-propelled torpedoes, for example, which were built at Woolwich after 1871. The fact that Robert Whitehead, the inventor, was willing to sell his patents to the Admiralty made room for the arsenal in this instance.16 When, however, an inventor preferred to set up a new company, as Hiram Maxim did in 1884 to make his newly invented machine guns, the law did not permit Woolwich to infringe patents.

The army rather than the navy was, of course, the principal British purchaser for Maxim’s machine guns; and the fact that truly efficient designs could be secured only from private manufacturers after 1884 probably reinforced professional suspicion of the new weapon. At any rate the War Office purchased very few Maxims despite the fact that their lethal efficiency was demonstrated repeatedly in colonial campaigns.17 Before the Boer War (1899–1902) the British army remained generally satisfied with what the arsenal could supply and avoided contracts with private firms on principle whenever possible. This was facilitated by the fact that technical changes in land armament remained comparatively modest.18 Everyone assumed that field weapons would always have to be light enough for horses to pull. The potentialities of internal combustion motors (developed from the 1880s for private automobiles) were left unexplored. Such technical conservatism made it easier for soldiers to preserve their traditional affection for horses and their no less traditional suspicion of profitseeking businessmen and inventors. This was true on the Continent as well as in Great Britain. Even the Germans, who had to deal with Krupp rather than with arsenal personnel for their field artillery after 1871, nurtured a deep repugnance towards the self-seeking and greed that they felt to be intrinsic to commerce; and the few army officers who lent themselves to Krupp’s blandishments remained an isolated handful, more or less suspect among their fellows.19 Conversely, the preservation of such attitudes in all European armies after the 1880s held back the pace of technical change to no more than a snail’s pace in comparison to what was happening simultaneously to European navies.

The very complexity of naval construction dictated a quite different attitude as soon as the Royal Navy began buying guns and other heavy equipment from private manufacturers. Inevitably, personal links between the circle of technically responsible naval officers and the managers of private firms became very close. William White, for example, who became chief naval designer in 1885, had worked at Armstrong’s for a two-year spell immediately before assuming his new post. He became perhaps the principal link between the Royal Navy and private industry thereafter.20 Captain Andrew Noble moved the other way. He abandoned a career in the navy to work for Armstrong and rose to become head of the firm in 1900 when the founder died. It was also possible to start at the top, as Admiral Sir Astley Cooper Key did in 1886 by becoming chairman of the board of a newly established armaments firm, the Nordenfeldt Gun and Ammunition Company. By the first decade of the twentieth century, it was even possible for Admiral Sir Percy Scott to enter into royalty contracts with Vickers for inventions he made “on the side” in the course of his professional work.21

Pecuniary self-aggrandizement did not become really respectable in the navy any more than in the army; and Admiral Scott was greedy rather than businesslike. Nevertheless, extensive dealings with one another and continual consultation over technical and financial questions between private businessmen and naval officers went a long way to break down older mistrust.

Friction and subterfuge were never entirely eliminated from the relationship, which revolved, after all, around the ancient ambivalences between buyer and seller. But in spite of occasional accusations of bad faith, collaboration in the myriad problems of how to design new and better warships prevailed. In effect, a small company of technocrats constructed a slender bridge across the chasm which had previously divided naval officers from the manufacturing and business world. In doing so, they provided a means whereby the new potentialities of democratic and parliamentary politics could be realized in the form of successive generations of new weaponry, each more formidable, more costly, and more important for the national economy as a whole than its predecessor.

The bridge between the navy and the arms industry was still weak and carried relatively little traffic in 1889, when the building program of 1884 ran out. A Naval Defence Act was duly brought in by the government. It cost £21.5 million, nearly four times the supplementary appropriation in 1884; and the number of ships to be built, half of them in private shipyards, reached the impressive total of seventy. The scale of the program was officially justified by proclamation of a “two-power standard.” This meant that the Royal Navy ought always to be equal or superior to the combined forces of the next two largest navies in the world. Only so, it was argued, could Britain’s security be guaranteed against any and all contingencies.22

A striking fact about 1889 program was that it exceeded what the Admiralty had asked for. Personal initiative and purpose no longer controlled what happened. Instead, organized groups interacted with one another, creating a process more complicated than any of the participants could fully comprehend. But the upshot was unidirectional, propelling the government to increased investment in armaments.

As in 1884, there were plenty of viewers-with-alarm on the English side of the Channel. The French cooperated magnificently, partly by themselves embarking in 1888 on a large-scale naval building campaign no longer limited to torpedo boats and cruisers; and partly by unleashing a surge of jingoism focused upon the mock heroic figure of General Boulanger. French jingoism wakened an answering note across the channel. Britain’s most respected soldier, Lord Wolseley, announced in the House of Lords that “so long as the Navy is as weak as it is at the moment her Majesty’s army cannot . . . guarantee even the safety of the capital in which we are at this moment.”23 And the prime minister, Lord Salisbury, convinced himself that “there are circumstances under which a French invasion may be possible.”24

The fact that even in a time of general prosperity the steel business and shipbuilding were in difficulty added fuel to the fires of agitation. But what most affected government thinking was the strategic calculation that the French and Russian fleets, acting in concert, might be able to drive the Royal Navy from the Mediterranean. In addition, Conservative politicians like Lord George Hamilton, First Lord of the Admiralty in 1889, recognized that naval appropriations were popular and might help the party at the polls.25

With party advantage, national interest, and popular enthusiasm all pulling in the same direction as the special interest of private arms makers and the steel and shipbuilding industries, it is not so surprising that the Admiralty got more money to spend for new ships in 1889 than it had asked for or expected. The effect within British society, clearly, was to confirm and strengthen vested interests in continued, indeed expanded, naval appropriations.26

This became obvious as the five-year plan of 1889 neared its end. In 1893, a general trade depression hit; Gladstone was back in office and earnestly opposed the idea of increasing taxes to pay for more warships in a time of economic downswing. But when it came to the pinch, no other member of the Cabinet agreed with his views. After tense weeks of debate, Gladstone resigned rather than endorse the naval building plan which his ministerial colleague, Lord Spencer, brought in as First Lord of the Admiralty. Once Gladstone was out of the way, the program, requiring a five-year expenditure of £21.2 million, passed through Parliament with ease. Publicists aroused support for the bill swiftly and skillfully. Indeed such agitation became fully institutionalized with the establishment of the Navy League in 1894.

New crises were swift in coming, for by the 1890s other nations had caught the naval fever, including such industrial giants as the United States and Germany. An American naval officer, Alfred Thayer Mahan, published his famous volumes, The Influence of Sea Power on History, in 1890 and 1892 in an effort to persuade Americans of the importance of building a new, modern navy. His success at home in the United States as well as abroad, especially in Germany, was phenomenal. As a result, with the new century, the two-power standard became impractical for Britain at a time when the outbreak of the Boer War dramatized the country’s isolation. The unexpectedly long and difficult character of that war raised military and naval expenditures to hitherto unequaled levels, so it was not until 1905, when a new Liberal government took office, that an opportunity to bring military expenditure under stricter control again seemed to present itself.

By that time Admiral Fisher had become First Sea Lord, remaining in office from 1904 to 1910. He reacted to demands for economy by reforming personnel policies at home while closing down naval stations overseas and ruthlessly retiring obsolescent warships.27 At the same time, he concentrated much of his enormous energy on building a new super battleship, H.M.S. Dreadnought. This formidable vessel, launched in 1906, made it necessary for rival navies—the German above all—to suspend building programs until vessels comparable to the Dreadnought could be designed. Liberal politicians believed that this would allow the government to cut back the pace of naval building. Only so could projected reductions in the naval estimates be sustained.

But such a policy meant unemployment and loss of business for shipbuilders and other contractors who had become dependent on naval construction. It was one thing when naval cutbacks worked harm to overseas communities like Halifax, Nova Scotia, or the Bahamas, which lacked parliamentary representation; it was quite another when British constituencies were about to be affected.28 Conservatives seized upon the issue fervently and launched a noisy agitation for more, not fewer, warships. The Germans tipped the balance decisively by announcing a new and enlarged building program in 1908; and as a result, the Liberal government, which had proposed to build only four dreadnought-type ships in 1909, ended by authorizing the construction of eight such ships. In Winston Churchill’s words: “In the end a curious and characteristic solution was reached. The Admiralty had demanded six ships: the economists [of whom he was one] offered four: and we finally compromised on eight.”29

This long series of political decisions, trending always towards larger naval expenditures, was fueled by a runaway technological revolution as well as by international rivalries and the changed structure of Great Britain’s domestic politics. A powerful feedback loop established itself, for technological transformations could not have proceeded nearly so rapidly if economic interest groups favoring enlarged public expenditure had not come into existence to facilitate the passage of bigger and bigger naval bills. Each naval building program, in turn, opened the path for further technological change, making older ships obsolete and requiring still larger appropriations for the next round of building.

How much weight to assign technological innovation as an autonomous element in this pattern of escalating expenditure is impossible to say. What one can discern, however, is a change in its character. Before the 1880s, invention had nearly always been the work of individuals, sometimes with the help of a supporting cast of technicians and skilled mechanics who built prototypes and otherwise assisted the inventor himself in embodying his idea in material form. Armstrong and Whitworth had both worked on these lines, using the resources of their respective firms to develop new models for guns and other kinds of machinery as they personally saw fit. Development costs, such as they were, had to be borne by the entrepreneur, and his only prospect of recovering them and making a profit depended on being able to sell his invention to skeptical buyers—whether these were private consumers in civil life or officers of the armed forces. Risks in the armaments field were very great. As Whitworth discovered in 1863–64, even a definitely superior product might not be accepted by fiscally and technically conservative officers and officials.

Under these circumstances, investment in arms research and development was sure to remain comparatively modest. Even so, as we have seen in the preceding chapter, a few innovators—Armstrong, Dreyse, Krupp, and their like—were able to revolutionize armaments simply by bringing military technology to the level of civil engineering. But this mid-nineteenth-century style of private invention was quite incapable of carrying naval engineering to the heights actually attained between 1884 and 1914. Even big and successful firms, like Krupp and Armstrong, could not risk the ballooning costs of experiment and development, had they not been assured of a purchaser ahead of time.

From the 1880s onward, however, the Admiralty routinely provided the assurance private firms required. Navy technicians set out to specify the desirable performance characteristics for a new gun, engine, or ship, and, in effect, challenged engineers to come up with appropriate designs. Invention thus became deliberate. Within limits, tactical and strategic planning began to shape warships instead of the other way around. Above all, Admiralty officials ceased to set brakes on innovation by sitting in judgment on novelties proposed by the trade. Instead, technically proficient officers clustered around the dynamic figure of Admiral Fisher to hurry innovations on. With the new century, the Admiralty even began to ease the tribulations that had always before beset inventors by paying at least some of the costs for testing new devices that seemed particularly promising.

One of the first triumphs of this “command technology” was the development of quick-firing guns. In 1881, when the torpedo-boat threat was new, the Admiralty defined the characteristics of a quick-firing gun needed to combat the danger. What the Admiralty wanted was a gun capable of firing at least twelve times a minute and powerful enough to blow an approaching torpedo boat out of the water long before it got within the 600 yards which then represented the effective range for self-propelled torpedoes.30

By 1886, when Admiral Fisher was at last authorized to turn to private firms for weapons the arsenal could not supply, two different designs already existed which met the Admiralty’s 1881 specification. The one actually chosen was the work of a Swedish engineer named Nordenfeldt. He promptly set up a new company, with retired Admiral Sir Astley Cooper Key as chairman, to manufacture it. Armstrong simultaneously developed large-caliber quick-firing guns whose power much exceeded the specifications of 1881. The largest of these used hydraulic recoil cylinders to return the gun automatically to firing position after each discharge. This, together with radically improved breech mechanisms and a simple device for sealing the chamber at the moment of ignition—both borrowed from French artillery designs—made the Armstrong quick-firing guns of 1887 profoundly revolutionary. All subsequent artillery, indeed, derives basically from this combination of features which allowed the gun to fire several times a minute and still remain almost on target, round after round. The man mainly responsible for the new recoil system was Joseph Vavasseur. His personal and professional association with Admiral Fisher became so close that he made Fisher’s son the heir to his fortune, having no children of his own.31

Command technology was not entirely new in 1881, of course. As we saw in chapter 4 sporadic instances of similar relationships between officials and inventors appeared in the eighteenth century, and perhaps even earlier. Indeed, from the 1860s, as warship design began to alter rapidly, it became usual for the Admiralty to specify the basic characteristics a new ship should have—speed, size, armor, and armament. Sometimes more specific requirements were set forth, e.g., with respect to all-round fire from turrets when they were first introduced.32

What distinguished the situation that developed after 1884 was not so much any absolute novelty as the range, breadth, and constantly expanding ramifications of the new naval version of command technology.33 Indeed, for thirty years, 1884–1914, it grew like a cancer within the tissues of the world’s market economy which earlier had seemed immortal as well as invincible.

Even a hasty review of the major landmarks of naval technological change between 1884 and 1914 will demonstrate the enlarged scope command technology attained in these years. After quick-firing guns—which rapidly escalated in size with only a modest diminution in rate of fire34—came the escalation of ships’ speed. The initial departure lay in the development of a new “tube boiler” design, pioneered by a boat builder named Alfred Yarrow. He won an Admiralty contract to build a new type of vessel first called “torpedo boat destroyers” but soon known simply as destroyers. Their task was to intercept torpedo boats before they could get dangerously close to capital ships. This required destroyers to be faster than their prey and also seaworthy. It was a tall order, yet the first destroyer, launched in 1893, attained a speed of over 26 knots—some two to three knots faster than contemporary torpedo boats. Four years afterwards, when Yarrow’s boilers were hitched up to steam turbines (patented by Charles Parsons in 1884), the result was a ship capable of over 36 knots—more than twice the speed warships of a decade earlier had been able to attain.35

In 1898 and again in 1905 actual sea battles in distant waters gave naval designers a better idea of what their new warships could achieve in combat. The Spanish-American War of 1898 showed the penalty of lagging behind technically, for obsolete Spanish vessels were no match for the newer American ships. Yet United States naval bombardments in Manila Bay, under calm conditions, and at Santiago Bay in a rougher sea, proved embarrassingly inaccurate.36 Subsequent efforts to improve aiming methods met with such success, that when the Japanese defeated and destroyed the Russian navy in Tsushima Straits (1905), they were able to deliver punishing fire at up to 13,000 yards. This was about twice the range that had baffled American marksmen in Manila Bay seven years before.37

H.M.S. Dreadnought was the Royal Navy’s answer to these developments. Designed for long-range gunnery, it outclassed all existing warships, thanks to a combination of superior speed and firepower. At 21 knots, the Dreadnought could outstrip all other capital ships by some two to three knots; and its broadside of ten twelve-inch rifles far exceeded the throw weight attainable by older battleships. Oil fuel and turbine engines of unprecedented size gave the Dreadnought an impressive range on top of its other characteristics. Its comparatively light armor scarcely mattered, if accurate gunnery at long ranges could be achieved, since its speed would permit the captain to choose when and where and at what range to engage an enemy.38

In 1906, however, the Royal Navy’s ability to hit a moving target from the deck of a pitching ship that was itself moving at speed and might be obliged to change course while engaged against a foe was very much in question. Intense efforts to solve the problem extended naval guns’ effective range spectacularly, but when war broke out in 1914, most Royal Navy ships were not yet equipped with the improved range finders and centralized fire control apparatus which experts had developed. Moreover, British range finders were inferior to comparable German equipment and the whole system fell short of making the guns carried by the newer ships effective at anything like their full range. In 1912, for example, fifteen-inch guns, capable of lofting a shell 35,000 yards (20 miles), were ordered from Armstrong, but the Royal Navy’s range finders were inadequate at 16,000 yards.39

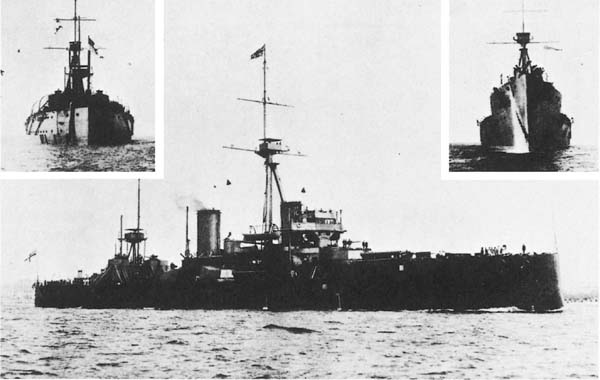

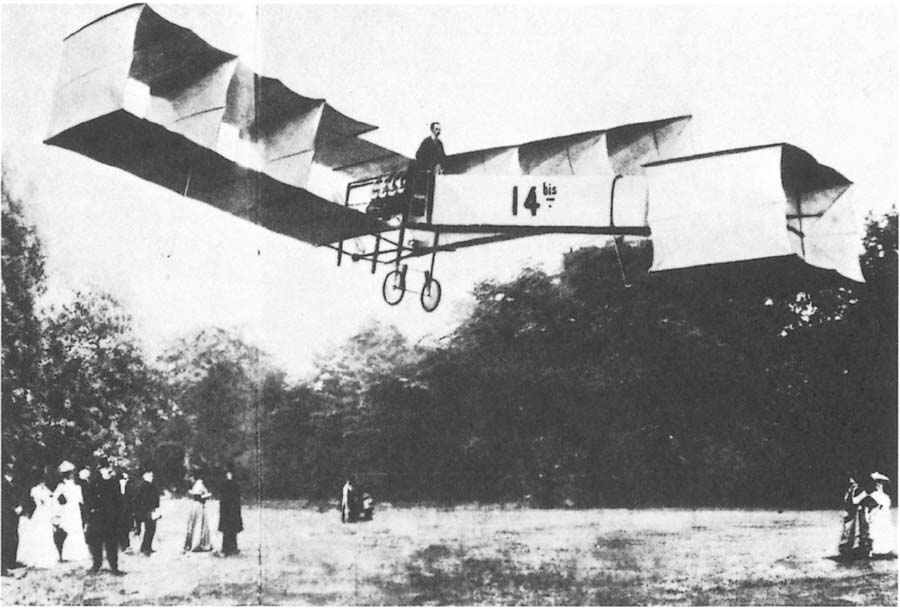

The photograph at top shows H.M.S. Dreadnought, the speedy, heavy-gunned battleship that altered the basis of naval competition between Britain and Germany when it was launched in 1906. Insets show views from bow and stern. But submarines already constituted a threat to even the most heavily armed and armored battleships, as the artist’s drawing (middle) suggests. Note the periscope, invented only three years before. Airplanes were also developing rapidly as shown in the 1906 photograph of a French aviator (bottom) who seems to be flying backward in his push-prop plane.

Illustrated London News, 1906, pp. 548 (20 Oct.), 301 (1 Sept.), and 841 (8 Dec.)

Torpedo ranges, meanwhile, spurted upward,40 and improved torpedo-carrying submarines made them far more of a threat to the Royal Navy than the torpedo boats of the 1880s had ever been. As before, the French took the lead when Gustave Zédé designed the first practicable seagoing submersible in 1887. In 1903, periscopes gave submarines eyes with which to aim torpedoes at their targets while remaining submerged. This imparted fresh substance to the long-standing French dream of finding a new weapon with which to destroy British sovereignty of the seas. But the Franco-British naval race, briefly reinvigorated by Fashoda (1898), soon dwindled to insignificance. The diplomatic entente of 1904 made nonsense of the French plan to build submarines for use against Great Britain. Resources were concentrated instead on outbuilding France’s Mediterranean rivals—Italy, Austria, and Turkey.41

Anglo-German rivalry, however, which set in seriously only after 1898, concentrated almost exclusively on capital ships because Admiral Tirpitz and his colleagues accepted Mahan’s teachings wholeheartedly. Submarines seemed to him no more than minor adjuncts to the battleships which alone could exercise command of the sea. As a result of such single-mindedness, in the decade after the Dreadnought revolution of 1906 battleship design showed signs of approaching a limit set by the physical characteristics of the alloyed steel used in engines, guns and armor.

Any such incipient stabilization was destined to be upset by the rise of air power, a possibility clearly foreseen before 1914. The Royal Navy, for instance, conducted successful experiments with torpedo-carrying airplanes in 1913, though difficulties in making a torpedo establish an appropriate path through the water after being dropped from the air were not entirely solved when the war began.42

As of 1914, the British Admiralty had developed no technical riposte to these new underwater and airborne challenges to capital ships. The fears that had been played upon in 1884 to mobilize support for the technical modernization of the Royal Navy were as lively as ever and rather better based in technical fact. Like the Red Queen in Through the Looking Glass Britain and all the other naval powers had to run ever faster just to stay in the same place. Indeed, thanks to the German naval building program, after 1898 the Royal Navy faced a more serious challenge at sea than at any time since the 1770s. But before considering this vindication of Admiral Sir Astley Cooper Key’s foresight concerning the consequences of Fisher’s initiative of 1884, it seems well to consider how the naval race affected British society in the decades before World War I, for this was the time when the modern military-industrial complex suddenly came of age and began, in the very citadel of European liberalism, to exhibit a wayward will of its own.

Naval Armament and the Politicization of Economics

First of all, naval construction and the manufacture of the diverse kinds of machinery that went into warships became really big business. Instead of lagging behind civil engineering, as had been the case in 1855 when William Armstrong decided it was time to bring gunmaking abreast of contemporary standards, military technology came to constitute the leading edge of British (and world) engineering and technical development.43 According to one calculation, about a quarter of a million civilians, or 2.5 percent of the entire male work force of Great Britain, was employed by the navy or by prime naval contractors in 1897;44 and by 1913 when naval appropriations had doubled the figure for 1897, estimates make as much as one-sixth of Britain’s work force dependent on naval contracting.45

The process through which welfare and warfare linked together to support the naval race had its shady side. Outright bribery and corruption played a lesser role than half-truths and deliberate deceptions. Businessmen seeking contracts found support from their local MPs helpful in persuading Admiralty officers to incline in their direction; and candidates for Parliament found contributions from grateful or merely hopeful constituents useful in meeting election expenses. Newspaper agitation, too, could be arranged by giving cooperative journalists inside information, or by entertaining them lavishly while hinting at secrets they were expected to trumpet to the world the next day.

Using these techniques, naval officers began to fight battles among themselves through calculated and uncalculated leaks to the press, exacerbated, as often as not, by journalists’ speculation and plain rumor-mongering. In particular, a personal vendetta between Admiral Fisher and Admiral Charles Beresford, conducted largely through the press and in Parliament, came to involve almost every aspect of Admiralty affairs. Naval officers achieved star billing in the popular press, much as movie actors were later to do, and sometimes behaved like spoiled children.

Rules of the game were unclear. Muckracking journalism dated back only to the scandals of the Crimean War, and all who undertook to manipulate public affairs through newspapers faced awkward tensions between personal advantage and presumed public good. A journalist who built up circulation at the expense of truth was on morally dubious ground. So was the manufacturer who set out to influence a naval contract by contributing to politicians’ election funds. The morals of naval officers who resorted to the press as a means of criticizing their superiors or who tried to influence public policies by divulging secret information were also questionable, since their private sense of “higher duty” to the nation collided with long-standing rules of obedience and discipline. Yet personal careers were made and broken by such gambits, as Admiral Sir John Fisher’s example so conspicuously demonstrated.

Any important change in society is likely to entail disturbances in prevailing moral codes and patterns of conduct. The moral ambiguities inherent in the new way of mobilizing resources, so flamboyantly inaugurated in 1884, perhaps only registered the importance of this new path for getting things done.

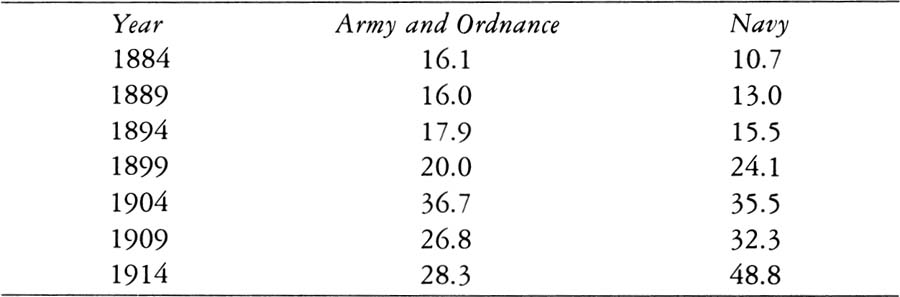

How powerfully it operated is best summed up by the figures in table 1 where we see that while army costs fell short of doubling, navy costs multiplied almost five times in thirty years, and this in an age of almost stable price levels. Clearly, by embracing new technology and the private sector as suppliers of armaments, the Royal Navy succeeded in capturing a larger slice of public appropriations in a time when the army, remaining loyal to older forms of management and relying almost wholly on arsenal production and design for its weapons, lagged far behind.

Table 1. Authorized Expenditures (£ million)

Source: B. R. Mitchell, Abstracts of British Statistics (Cambridge, 1971), pp. 397–98.

Intensified interaction between industry and the navy brought serious new pressures on two other facets of public management, the one financial, the other technical.

Financial problems became especially acute because of the unpredictability of costs. This in turn arose out of the very rapidity with which new devices and processes were introduced. Over and over again, a promising new idea proved far more expensive than it first appeared would be the case; yet to halt in midstream or refuse to try something new until its feasibility had been thoroughly tested meant handing over technical leadership to someone else’s navy.

The Royal Navy, of course, was not supposed to spend more than Parliament authorized. But from the time of Samuel Pepys and before, the Admiralty had been in the habit of borrowing money from London bankers to meet current expenses whenever outgo ran ahead of parliamentary grants. As long as ships and guns changed slowly, if at all, costs were quite predictable. A prudent Board of Admiralty could therefore borrow in emergency and then repay when Parliament saw fit to cover past deficits without piling up dangerously heavy debt. The system gave Parliament more or less what it paid for, while the Admiralty had a useful flexibility in managing its affairs.

But when technology began to change as rapidly as it did after 1880, predictable limits to expenditures faded from sight. Borrowing to cover cost overruns became irresistible. Not to borrow might hold up completion of a new ship or allow the Germans to outstrip the Royal Navy in some important technical development. Yet if borrowing to cover excess costs went too far, interest payments alone would soon eat seriously into current appropriations. In pursuing a go-for-broke policy in technical matters, the Admiralty therefore found itself heading straight towards what would be bankruptcy for any private firm, and that despite the upward curve of parliamentary appropriations.

Under the circumstances, parliamentary control over naval expenditure began to dissolve. Ordinary members of Parliament knew little or nothing about Admiralty borrowing, and, like the general public, assumed that annual appropriations registered and regulated what was actually spent. By 1909, the situation had got so far out of hand that it became necessary to find new sources of tax money to pay off past indebtedness while simultaneously expanding the scale of naval building. Lloyd George’s famous budget of 1909, with its soak-the-rich and social welfare provisions, was the government’s answer to the problem. It showed, clearly enough, that an all-out arms race could be conducted only by a government prepared to intervene drastically in prevailing socioeconomic relationships. In particular, progressive taxes, heavy enough to effect perceptible redistribution of wealth within society, were needed to mobilize resources for public purposes on the necessary scale. The House of Lords’ effort to block the new taxes imposed by Lloyd George’s budget, and the quasi-revolutionary atmosphere that resulted from the government’s determination to override the peers and nullify their veto, was an important element in the general breakup of liberal nineteenth-century society and institutions that came to a head during World War I.

Financial uncertainty and disordering of accustomed patterns of management were not confined to the Admiralty and Treasury. On the contrary, the new arms technology also presented private armaments firms with extremely difficult managerial problems. Feast or famine was the usual alternative they faced. Some firms’ fat profits (Vickers averaged at 13.3 percent dividend on its capital in the first decade of the twentieth century)46 were matched by the bankruptcy or threatened bankruptcy of others. Admiralty policy in awarding contracts, a policy that itself wavered between narrowly pecuniary and broader political considerations, played the decisive role more often than not in determining which firms flourished and which would go under.

Ordinary market behavior had only limited scope in such an environment. Special relationships with procurement officials and with technically innovative officers often mattered more than prices in deciding who got a contract and who was passed over. Yet this cozy relationship among experts was also subject to jarring disturbance from outside when overtly political pressures to economize, or to spread the work by helping some depressed region or firm, were brought to bear.

Conventional cost accounting was an imperfect instrument for anyone trying to manage an arms firm under these circumstances. A contract to build a piece of machinery that had never been seen on earth before commonly required capital investment of a substantial sort. But whether the new facility would continue to be used or would instead have to be discarded after the completion of a single contract because some new device or design had come along in the meanwhile and rendered it obsolete—this no one could ever know for certain. What then was the proper cost to assign to such an undertaking? Could and should a firm expect to recover its entire capital costs from a single contract? If so, the price would have to be very high; and any subsequent utilization of the new capital plant would be sure to bring in those swollen profits of which armaments producers were later to be so vigorously accused. But if capital costs were instead amortized over a longer period of time, what guarantee was there that fresh contracts would be forthcoming so that the new plant would not simply stand idle after the initial contract had been fulfilled? Neither Admiralty officials nor private entrepreneurs could answer such questions with any kind of precision in a world of rapidly changing techniques. It was, therefore, a high risk business—inevitably.

To be sure, foreign sales could make such problems far less acute for the private firm, but only as long as the Admiralty did not impose restrictions upon letting foreigners share technical secrets that derived from research and development which had been funded, at least in part, by public monies.47 Collusive bidding among competing firms was an even more obvious way to reduce risks. The Admiralty countered by looking around for new firms and inducing them to enter the arms trade as a way of expanding supply, lowering prices, and forestalling monopoly. This was how Vickers entered the arms business in 1888, for example, responding to urgent solicitation from the Admiralty to bid on a contract for armor plate. But Vickers’ decision also reflected the firm’s mounting difficulty in matching American and German steel prices on the civilian market. By moving into armaments production, Vickers successfully insulated itself from foreign cost competition, since the Admiralty was not interested in buying armaments from any but British suppliers.48

With costs so unpredictable on both the private and the public side, the reality of competition and open bidding diminished rapidly. New firms like Vickers quickly learned how to cooperate with Armstrong and other established arms makers. To be sure, a new patent might permit the entry of another firm into the arms trade; but such companies regularly confronted financial crisis once initial contracts had been fulfilled since new orders were usually not forthcoming on a scale to keep their capital plant busy. Under such conditions, the universal response was to amalgamate with older arms makers and form corporations whose financial and technical resources then would allow managers to spread risks within the firm by shifting men and machinery from one to another contract as the needs of the Admiralty (and foreign sales) might dictate.

Such firms, when they became big enough, assumed many of the characteristics of a government bureaucracy. Being in a monopolistic or at least quasi-monopolistic position with respect to capacity for making complex armament items, they could bargain on more or less even terms with Admiralty purchasing agents, who, increasingly, had nowhere else to turn when they sought to buy highly specialized (and often secret) new kinds of equipment. Private arms makers, in other words, came more and more to resemble the Woolwich arsenal, with the difference that the navy and their suppliers were accustomed to live with far more radical technical changeability than anything that had yet descended upon the army and the arsenal.

How rapidly amalgamation of British arms firms occurred may be illustrated from the history of the Maxim Gun Company. Having been established to make machine guns in 1884, it merged, just four years later, with the Nordenfeldt Company. Then the Maxim-Nordenfeldt Company was bought out by Vickers in 1897. Armstrong, too, entered upon a series of mergers, the most important of which was the acquisition of Whitworth’s, its long-standing rival, in 1897. By 1900, therefore, two big firms, Vickers and Armstrong, dominated the business of heavy armaments in Great Britain. Each dealt with the Admiralty on a quasi-public basis. That is to say, considerations of the political and economic consequences of how any big new contract was to be shared out between the two great firms and their lesser rivals came to be an important consideration in Admiralty decision-making, competing with and sometimes overriding simple pecuniary calculation.49

In the foreign field, where competition with Krupp and the principal French arms manufacturer, Schneider-Creusot, became intense after 1885, considerations of national prestige, diplomatic alignments, and outright bribery frequently entered into deciding what kind of guns or warships a technically backward country would purchase. Credit arrangements, often at least partly inspired by foreign offices’ representations to private bankers, were even more decisive, since few of the arms-purchasing countries could come across with cash to pay for the weaponry they wanted.

Once they had consolidated their position in the home market, Vickers and Armstrong found it imprudent to compete against each other abroad. By 1906, they had, in effect, achieved market-sharing agreements covering most of the globe. In addition, patent and royalty arrangements with Krupp gave the two British firms access to some of Krupp’s metallurgical inventions, while Krupp got rights to certain British patents in return. Schneider had similar arrangements too. In this way an international arms ring, which became the object of intense opprobrium after World War I, came into existence. Pecuniary considerations ordinarily dictated cooperation and collusive bidding among the leading firms. On the other hand, political rivalries and national pride made for cutthroat competition and sometimes set prices at uneconomic levels. What really happened depended on how these contrary forces interacted in each particular case.

Ever since the technological breakaway of the 1850s, private arms manufacturers had prospered by entering the foreign market as a way of increasing their income and smoothing out peaks and valleys created by fluctuating home demand for their products. As long as invention and costs of development were met entirely by private firms, this did not raise any particularly delicate moral questions; but after the 1880s, when intimate collaboration between navy officers and private engineers and production experts entered into the development of every important new device, foreign sales did begin to raise serious questions about who had the right to sell what, and to whom. National loyalty obstructed profitable dealing with potential enemies. By operating in lands allied or aligned with the home country, this dilemma could be sidestepped, at least as long as the diplomatic constellation remained unchanged. But patent-sharing agreements between British arms firms and Krupp, some of which were honored even during World War I years, raised the issue of which came first—the nation or the firm, public good or private enrichment—and in especially poignant fashion.50

Overall, it seems clear that as arms firms became pioneers of one new technology after another—steel metallurgy, industrial chemistry, electrical machinery, radio communications, turbines, diesels, optics, calculators (for fire control), hydraulic machinery, and the like—they evolved quickly into vast bureaucratic structures of a quasi-public character. Technical and financial decisions made within the big firms began to have public importance. The actual quality of their weapons mattered vitally to the rival states and armed services of Europe. After 1866 and 1870, everyone recognized that some newly won technical superiority might bring decisive advantage in war. Each technical option in arms design therefore carried a heavy freight of political and military implications and had to be taken with an eye both to the national interest and to the financial future of the firm within which the new device was being developed.

Fast acting feedback loops thus arose whereby financial and man agerial decisions in the Admiralty meshed into financial and managerial decisions made within what were still ostensibly private firms. Public and private policy became irremediably intertwined. Liberal critics of the 1920s and 1930s and Marxist or quasi-Marxist historians since the 1950s assert that the dominating element in this mix was the private one. The pursuit of profit, according to this view, provided the energizing force. Everything else was derivative, manipulated by clever and greedy men who wished to enrich themselves and the stockholders they served.

This seems a distorted vision of human motivation and behavior. No doubt when patriotism and profit were seen to coincide, the response was so much the more electric; and this was the way private managers of arms firms usually viewed their roles. But the abstract challenge of problem-solving has its part in governing human actions, and the arms trade attracted more than its share of technically innovative minds in the pre-World War I period simply because it was there that industrial research was most vigorously underway.51 One innovator attracted others in chain-reaction fashion.

Moreover, concepts of technical efficiency, public service, and advancing a career by making the right decisions clearly dominated the minds of the naval officers who played such a large role in the entire process. The power of promotion in rank to focus ambition and inspire men to strenuous effort is very great indeed, as anyone who has served in a modern army or navy can attest. Promotion carried economic perquisites, to be sure; but what really mattered was the deference and precedence over others that advance in rank entailed. If the profit motive had really dominated behavior, Admiral Fisher would not have turned down a job offer he got from Whitworth’s in 1887, for example, nor would the naval designer William White have returned to the Admiralty at one-third of the salary he had received during his two years at Armstrong’s.

The public interest, as colored by careerism within the naval command hierarchy, together with overtly political pressures coming from the Cabinet and through Parliament, probably did more to control the overall direction of technical change than did private considerations of profit. But it is really unhistorical to ask which of a complex of motives dominated decision-making. The important thing was how closely public and private motives intertwined. Market and pecuniary considerations were not firmly subordinated to political command before 1914; but then, political and military decisions were not subordinated to profit maximizing by private manufacturers either.52

The push towards making political decisions into the critical basis of economic innovation was clearly apparent in the weaker and less industrialized countries of Europe before 1914; and in Japan it was unmistakable. But Britain and Germany, too, were moving rapidly in that direction from the 1880s onward. In the politicization of the decision-making by which they lived, as in high technology, the great arms firms were far in the lead of other industrial sectors. The arms firms and the armed forces that dealt with them thus became the primary shapers of the twin processes that constitute a distinctive hallmark of the twentieth century: the industrialization of war and the politicization of economics.

The Limits of Rational Design and Management

The rush of new technology that cascaded upon the Royal Navy after 1884 not only put strains on morals, money, and managerial organization; it also began to get out of control itself. By the eve of World War I, fire control devices had become so complex that the admirals who had to decide what to approve and what to reject no longer understood what was at issue when rival designs were offered to them. The mathematical principles involved and the mechanical linkages fire control devices relied upon were simply too much for harassed and busy men to master. Decisions were therefore made in ignorance, often for financial or personal or political reasons.

The secrets of steel metallurgy, too, are exceedingly complex, and admirals presumably never understood the chemistry behind each of the new alloys that revolutionized guns and armor time and again. But the tests to be applied to guns and armor were fairly obvious,53 and after a test anyone could tell which gun or sample piece of armor plate was superior. When it came to fire control devices, similar tests could perhaps have been devised. But there was much room for difference of opinion about what suitable conditions for trials should be: parallel courses for both the target and the test ship presented entirely different problems from zigzag courses, while high speed made a ship toss differently from what it did at low speed, and a rough day made more difference still. Moreover, it was an expensive thing to hitch up the guns of a battleship to a machine capable of pointing every gun of the ship at a target. Such an installation had to be made by experts who thereby learned even the most secret inner workings of the ship.

The most fundamental issue, perhaps, was how to define the desired level of performance for fire control devices. This depended, in turn, on what kind of future battle was envisaged. If the Germans planned to come out and fight in Nelsonian fashion by laying alongside, then equipment that could pick up an enemy at 20,000 yards in poor light and drop the first salvo of shells in his vicinity was not critically important. Yet if a machine capable of such refinement could be invented, what navy could safely be without it?

This became a real dilemma for the Royal Navy when an ingenious private citizen named A. J. H. Pollen claimed to have solved the mathematical and mechanical problems inherent in accurate aiming at long range even from a moving and tossing ship. When he approached the Admiralty with drawings of his device in 1906, Admiral Fisher responded with enthusiasm, and declared that the navy should stop at nothing to get exclusive rights to the invention. Within a month, Pollen signed a contract guaranteeing him £100,000 and a handsome royalty on future sales if tests showed that his machine could do what he claimed. On the strength of this contract, Pollen set up a new company to manufacture his invention. He soon got into financial trouble, for there were all the usual complications in actually building a working model. Meanwhile, the Admiralty also was facing financial difficulties; and when a technically proficient officer decided that he could design a machine just as good as Pollen’s, the Admiralty saw a way of saving the promised £100,000. It took four years for the navy’s own machine to achieve a workable form, and that only after plagiarizing from a Pollen prototype in 1911.54 Nonetheless by 1913, Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, could say in Parliament:

“It is not intended to adopt the Pollen system, but to rely on a more satisfactory one which has been developed by service experts. . . . I have been guided by the representations of my naval colleagues and the advice of experts on whom the Admiralty must rely.”55

Yet the machine “developed by service experts” could only work if a ship followed a straight-line course while firing its guns, whereas Pollen’s device could adjust for a changing course as well. There were other defects in the fire control system installed on British ships from 1913 onwards. In particular, the Royal Navy’s optical range finders gave far less accurate results than those the Germans used at Jutland. Tests which might have shown the superiority of Pollen’s system were never held. To have done so would have cost large sums, risked having to pay the £100,000 the Admiralty had promised Pollen in case of success, and discredited an influential coterie of experts inside the Admiralty as well.56

One may argue, of course, that a machine capable of working under limited conditions and costing a good deal less was indeed, as Churchill said in Parliament, “more satisfactory” than the more expensive private design. Given the financial pressures that the navy had begun to experience, reasonable men might so decide. Moreover, firing from line-ahead formation was traditional. How else could an admiral keep control of a fleet and bring maximum firepower to bear? How else could naval tradition be upheld in a desperately confusing world? If it made range-finding for the enemy easier than firing from a zigzag pattern would do, what matter? The preferred tactic among British admirals was to fall back on the Nelsonian formula and close the range as fast as possible so as to achieve a decisive victory. To alter fleet management and tactical doctrine in deference to a piece of machinery few besides its inventor really understood—that was too much.

It seems clear that the angry cross-purposes that came to bear upon the controversy quite obscured the technical matter’s at issue. Few understood fully what was at stake. The whole question was supposed to be secret, and was in fact secret from all but a small number of insiders. But the men who had to decide were not themselves technically well informed and relied on what others told them. Under such circumstances Pollen’s status as a civilian, suspected of greed,57 put his salesmanship at a hopeless disadvantage against the advocacy of “service experts” for their own, technically inferior, invention. As an angry admiral wrote in 1912:

By placing Mr Pollen in the position of a favoured inventor we have put him in possession of the most complicated items of our Fire Control system and we are being constantly pressed by Mr Pollen to pay him large sums of money to keep that information for our exclusive use. Each time we pay him thus (monopoly rights) he gains more confidential information. . . . . it is a chain around our necks being forged more and more relentlessly.58

The decision to settle for an inferior system of fire control was particularly ill advised inasmuch as the Royal Navy seemed committed to bombardment at extreme range. The so-called battle cruisers (under construction 1905–10) had guns of the very largest size and could move at the highest speeds, but lacked more than rudimentary armor.59 They could hope to confront enemy battleships with impunity only by using their speed to hover just out of reach, while pounding their opponent to pieces by outranging his fire. Fisher conceived these super ships as constituting a second revolution in ship design, comparable to the famous Dreadnought revolution with which he had inaugurated his regime at the Admiralty. But without fire control machinery capable of exploiting the superior range of their heavy guns, such vessels were death traps, or close to it.

Oddly, no one seemed to care, not even Admiral Fisher, whose initial enthusiasm for Pollen’s invention evaporated when his subordinates told him that their cheaper device would do. Fisher’s tactical conception for the new battle cruisers was never even established as doctrine. Instead, Admiral Lord Beatty, who took command of the battle cruiser squadron in 1913, regarded his ships as a kind of sea cavalry whose superior speed should be used in reconnaissance and to lead the charge in battle. Traditionally minded naval officers, perhaps, felt that there was something sneaky and un-Nelsonian about trying to hover beyond the enemy’s reach while pounding him at extreme range. It could not be done anyway with the navy’s existing fire control devices. Hence, regulations prescribing target practice at 9,000 yards—a distance likely to be suicidal for thinly armored battle cruisers—remained in force. Bureaucratic inertia, however irrational, prevailed.60

In retrospect, at least, it seems clear that factional infighting and technical illiteracy combined with penny-pinching (what was Pollen’s £100,000 compared to the cost of a battle cruiser?) to make a botch of things. The Royal Navy paid for these errors at Jutland, where the long range at which the battle was fought, and the changes of course that took place during the encounter, diminished British chances of winning decisive victory of the kind they had counted on.61

Thus it seems correct to say that technical questions got out of control on the eve of World War I in the sense that established ways of handling them no longer assured reasonably rational or practically satisfactory choices. Secrecy obstructed wisdom; so did clique rivalries and suspicion of self-seeking. Most of all, the mathematical complexity of the problem—a complexity which clearly surpassed the comprehension of many of the men most intimately concerned—deprived policy of even residual rationality.

The technical revolution so brashly unleashed in 1884 could scarcely have had a more ironical outcome. Like so many other aspects of the naval race of the first years of the century, this, too, was a foretaste of things to come, anticipating the technologically uncontrolled and uncontrollable age in which we currently find ourselves. A colossal paradox lay in the fact that energetic effort to rationalize management, having won enormous and impressive victories on every front,62 nevertheless acted to put the social system as a whole out of control. As its parts became more rational, more manageable, more predictable, the general human context in which the Royal Navy and its rivals existed became more disordered and more unmanageable.63

The international side of this paradox is its most obvious aspect, for, as is well-known, military-industrial complexes spread swiftly from Great Britain to other industrial lands. Up to the 1890s, France had constituted the only plausible naval rival Great Britain had to face; but French taxpayers continued to resist the scale of naval appropriations needed to develop a self-sustaining feedback loop of the kind that arose in Great Britain after 1884. Even such a notable French technical breakthrough as the invention in 1875 of production methods capable of supplying the first uniform and dependable alloy steel for naval use,64 did not suffice to make the French navy a reliable ongoing market for French metallurgists. Instead, as we saw above, the French Chamber of Deputies suspended the building of battleships completely between 1881 and 1888.

This coincided with intensified price competition from German steelmakers. The French government reacted by imposing a protective tariff in 1881, and then in 1885 removed the ban on the sale of weapons to foreigners which had hitherto prevented French manufacturers from competing with Krupp, Armstrong, and Vickers in the international arms business. Response on the part of French arms makers was spectacular.65 During the 1890s, Schneider-Creusot, the leading French arms firm, squeezed Krupp out of the Russian market. French field artillery was, in fact, of superior design;66 but what sewed up the Russian market for the French was the political rapprochement of 1891–94, by which France became Russia’s ally against the Germans. Generous loans floated by French banks in response to hints from the Quai d’Orsay kept the tsar’s government solvent and allowed it to pay for strategically valuable imports from France. Steel for railroads was as important as weapons, and especially so for French steelmakers, who, thanks to their new foreign markets, were at last able to achieve a scale of production large enough to make technologically efficient, completely up-to-date mills profitable. As a result, the growth rate of French ferrous metallurgy in the twenty years before 1914 far outstripped even Germany’s.67 Their new technical efficiency, plus the financial recklessness of French banks in extending loans to dubiously credit-worthy governments, allowed French firms to invade German markets for arms and rails in such diverse places as China, Italy, the Balkans, and Latin America as well as Russia.

Export of arms and steel rails was matched by export of know-how. French and British arms firms energetically set out to help the Russians by building new and expanding old arms factories on a massive scale, especially after 1906. Soon the specter of a rearmed, technically modernized Russia, with a rail net that would permit rapid mobilization of its vast manpower, began to haunt German General Staff planners with ever increasing poignancy. The financial-technical linkup between France and Russia, with some British assistance, gave tangible reality to the German fear of encirclement.68

The French invasion of foreign arms markets was of serious concern to Krupp and to the German government, for economic as well as for military-strategic reasons. Krupp had always depended on foreign sales to keep its machine shops and arms manufactories busy. In the year 1890–91, for example, before French competition had begun to affect sales significantly, no less than 86.4 percent of Krupp’s armaments were sold abroad, whereas the German government took only 13.6 percent.69 After that date, the published figures for foreign sales break off, but it is certain that new French (and British) arms sales to foreign powers came largely at Krupp’s expense. As a result, Krupp’s foreign sales shrank to less than half the firm’s total output of armaments by 1914. Schneider likewise exported about half of its arms production on the eve of the war, whereas Vickers sold less than a third of its output abroad.70

In case after case, price competition, in which Krupp excelled, gave way to political economics. After 1903, Krupp could no longer finance sale of its arms by inducing French banks to subscribe to new loans to Russia and other impecunious governments. This had previously been possible, owing to the way investment capital traditionally pursued maximal returns, regardless of political frontiers or alliances. But after 1904 French lenders required borrowers to buy French arms and other goods more and more strictly.71 As a spokesman for Schneider-Creusot put it some years later: “We consider ourselves collaborators with the Government and we engage in no negotiations and follow up no business which has not received its concurrence.”72 This sort of collaboration allowed French arms exports almost to double in less than twenty years, from 6.6 million francs annual average value in the decade from 1895 to 1904, to 12.8 million francs annual average value in the years 1905 to 1913.73 Obviously, as Krupp’s foreign markets shrank back, the firm needed a politically assured substitute outlet. As is well known, Krupp’s managers found a solution in the form of the German naval building programs, launched in 1898 and periodically renewed thereafter at an ever escalating scale until 1914.