Advances in Europe’s Art of War, 1600-1750

The effectiveness of commercialized war as developed in Mediterranean Europe between 1300 and 1600 was attested by the sporadic spread of what may appropriately be dubbed the “military-commercial complex” to new ground thereafter. A parallel change was the bureaucratization of military administration. By slow degrees tax collection for the support of standing armed forces began to conform to bureaucratic regularity over wider and wider areas of the European continent. The internal administration of armies and navies moved in the same direction. Then, in the seventeenth century, the Dutch pioneered important improvements in military administration and routine. In particular, they discovered that long hours of repeated drill made armies more efficient in battle. Drill also imparted a remarkable esprit de corps to the rank and file, even when the soldiers were recruited from the lowest ranks of society.

A well-drilled army, responding to a clear chain of command that reached down to every corporal and squad from a monarch claiming to rule by divine right, constituted a more obedient and efficient instrument of policy than had ever been seen on earth before. Such armies could and did establish a superior level of public peace within all the principal European states. This allowed agriculture, commerce, and industry to flourish, and, in turn, enhanced the taxable wealth that kept the armed forces in being. A self-sustaining feedback loop thus arose that raised Europe’s power and wealth above levels other civilizations had attained. Relatively easy expansion at the expense of less well organized and disciplined armed establishments became assured, with the result that Europe’s world-girdling imperial career extended rapidly to new areas of the globe.

As we saw in chapter 3, commercial-bureaucratic management of armed force originated in Italy and then spread to the Low Countries, France, and Spain. In the course of the seventeenth century this modern organization of war took root in the Germanies and, with interesting variations, also in Sweden, England, and even in Russia.

The beginnings of the commercialization of military enterprise in Germany went back to the fourteenth century or before, when Italian cities hired large numbers of Swiss mountaineers and other Germans to fight their wars for them. Experience of war in Italy, in turn, underlay the successful assertion of Swiss independence in the fourteenth century. By defeating a force of German knights at Sempach (1387) Swiss halberdiers and pikemen established their reputation as formidable infantry fighters; in the next century they became the wonder of all Europe by defeating Charles the Bold’s technologically superior force no less than three times in 1476 and 1477. Shortly thereafter, Swiss pikemen entered French service (1479) as mercenary troops and for a brief period promised to give the French (whose native cavalry and artillery was already the best in Europe) a clear superiority over all rivals.1

Swiss alignment with the French monarchy induced the Hapsburgs to try to raise German foot soldiers to match the Swiss. Companies of Landesknechten, equipped like the Swiss but commanded by noblemen (who also fought on foot), accordingly came into existence, beginning on a significant scale in the 1490s. But since Maximilian I (emperor 1493–1519) and other German rulers were chronically impecunious, companies of Landesknechten could look forward to only sporadic employment. Discharge created a crisis for the soldiers and for the community in which they happened to be located at the time. The situation was quite like that which had prevailed in Italy in the early fourteenth century, before the Italian city-states learned how to weave effective political and fiscal restraints around professionalized armed forces.2

The German situation differed from the earlier Italian experience in one important respect. Beginning in 1517, German politics came to be colored by envenomed religious controversy. Lutherans, Catholics, and various radical sects were soon challenged also by Calvinism. Each religion commanded passionate loyalties of diverse social groups, so that secular conflicts commonly found expression in theological debates. Italy, too, had experienced acute social conflicts two centuries earlier; and the lower classes regularly had met defeat wherever and whenever military force came to be professionalized and put on a permanent basis. In Germany a similar development occurred, though in its initial stages the theological diversity of the Reformation sanctified and thereby probably intensified class collisions.

At any rate, something like stability came to the Germanies only after a century and a half of widespread violence, climaxing in the brutalities of the Thirty Years War (1618–48). By the time it ended, Germany and Bohemia had been caught up with a vengeance in the European military-commercial complex; and the lower classes, along with German city-states, had been firmly subordinated to princely power based on control over standing, professional armies. As bureaucratization spread and religious fanaticism dissipated, the German lands became religiously divided according to the principle cuius regio, eius religio.

At the commencement of this painful process, local, ecclesiastical, princely and imperial jurisdictions overlapped in an exceedingly confused fashion. The political complexity was like that which had existed in Italy before city-states asserted their territorial sovereignty by hiring armies and garrisoning border strongpoints. In the Germanies, not cities but princely courts consolidated effective sovereignty at the expense of more local rivals as well as of pope and emperor. Mercenary armies provided them with the sinews of sovereignty, just as had happened earlier in Italy. But the atmosphere of a German princeling’s court was poles apart from that of an Italian city of the renaissance era. So despite all the parallels that can be drawn between Italy from 1300 to 1500 and Germany from 1450 to 1650, the upshot of the process in the two countries was profoundly divergent.

At the beginning of this evolution the French king’s recent success in centralizing the administration of his kingdom offered the German emperors a most enticing model. What a French king had done to expel the English from the land (1453), a German emperor could also attempt, by leading a crusade either against the Turks or, alternatively, against heretics within the Germanies.

But crusading against the Turks ran into what proved to be insuperable geographic obstacles. Since 1526 Hungary and Croatia had become disputed borderlands between the Ottoman and Hapsburg empires. Raiding and counter-raiding devastated the landscape, making maintenance of large field armies in the border region exceedingly difficult for either of the protagonists. As a result, building and then garrisoning a few cannon-proof forts was all the Hapsburg authorities were able to accomplish.

The alternative of turning imperial forces against German princes who had departed from the Catholic fold became more attractive as the vigor of a reformed Catholicism took hold north of the Alps. Accordingly, when Ferdinand II ascended the imperial throne in 1619, he precipitated a general war by deciding to bring Bohemia (where a Calvinist king had been elected in 1618) back to Catholic and Hapsburg obedience. His initial successes provoked a series of interventions from outside: Danish, Swedish, and eventually French. On the Catholic side, the Spaniards renewed their war with the Dutch in 1621 and with France in 1622 and sought to use their imperial position in Italy to connect all the different fronts of the war into a single, coherent Catholic counteroffensive.

The eventual outcome was stalemate in the Germanies and a peace of exhaustion (Westphalia, 1648). Before that result was attained, however, some new refinements in the art of war achieved definition; and the Germanies as a whole experienced the brutality of large-scale commercialized violence.

Three significant efforts at drastic reorganization for war came to the fore during the struggle. The first of these was the remarkable military entrepreneurship of Albrecht von Wallenstein. Starting as a petty nobleman of Bohemia, Wallenstein made soldiering into a vast speculative business. High risks were matched by extraordinary windfall profits, at least in the short run, for Wallenstein became proprietor of enormous estates in Bohemia (briefly also in Mecklenburg) and attained quasi-independent political power. But when he died in 1634 at the hands of assassins, all the lands and offices he had accumulated were confiscated. Nevertheless, for a decade Wallenstein bestrode the Germanies like a colossus, nominally a mere contractor serving the emperor but in fact almost a sovereign in his own right by virtue of the size of the military forces he commanded and supplied by improved taxation, outright plunder, and massive market transactions.

Wallenstein’s business dealings were exceedingly complex. He bought products from his estates in Bohemia in his capacity as army commander at prices fixed by himself, for example, and organized arms production on those same estates with the help of capital scraped together by a Flemish businessman and speculator named Hans DeWitte. DeWitte’s relation to Wallenstein was like Wallenstein’s relation to the emperor. Each depended on his superior for the chance to engage in really big business. Yet in executing commissions and fulfilling contracts on a heroic scale, both Wallenstein and DeWitte pursued their own self-interest with flamboyant disregard of older standards of morality and propriety. What worked was all they cared about. Neither birth nor religion nor any of the traditional virtues governed their choice of associates and subordinates. Obedience and effectiveness in accomplishing assigned tasks was what Wallenstein and his financial counterpart demanded and got from those who served them. The result was an army of quite exceptional efficiency that for the most part lived off the country it operated in and exhibited no scruples in doing so. A more complete and grandiose merger of private commercial and military enterprise had never been seen before—nor since.

Other military middlemen played lesser roles in the Thirty Years War, but only Wallenstein succeeded in raising an army on his personal account that numbered over 50,000 men at its peak. He did so by commissioning lesser officers to form companies and regiments in the way reigning monarchs had long been accustomed to do. Towards the end of his career, Wallenstein toyed with the idea of using his army to coerce the emperor into dismissing a “Spanish” party that had gathered at court. The leading spirits of that faction vehemently distrusted the Bohemian adventurer, whose commercial virtuosity and religious ambiguity were utterly alien to their own aristocratic and Catholic ideals. It was they who arranged Wallenstein’s assassination. The emperor endorsed the act only subsequently.

Ever since the sudden denouement of 1634, German nationalists have wondered what might have happened had Wallenstein prevailed. The logic of his position perhaps required him to imitate the usurpation that Sforza had carried through in Milan in 1450. Sforza had successfully melded the administration of his military following into that of the Milanese state and made Milan into a great power for the ensuing fifty years. Wallenstein’s military command structure might perhaps have become the chrysalis of a new German state, greater even than the mighty kingdom of France that emerged from the Thirty Years War as hegemon of western Europe. But in fact, by 1634, Wallenstein was much enfeebled by chronic illness. Perhaps, too, even his bold entrepreneurial spirit quailed before the sacred aura that still clung to the person of the Holy Roman Emperor of the German Nation.

At any rate, the military-commercial empire he had constructed around himself collapsed. Lesser enterprisers divided his role in the imperial camp; and by the end of the war widespread devastation of some of the most fertile parts of Germany compelled armies to shrink to about half the size of those that had marched under Wallenstein’s command at the peak of his power.3

The second remarkable power structure of the Thirty Years War was that created by the Swedish king, Gustav Adolf (r. 1611–32). What Bohemia had been for Wallenstein, Sweden was for him—a sort of personal property from which manpower and supplies could be channeled towards the war in Germany. Gustav Adolf did declare that his war would have to feed itself,4 but he relied on public authority to conscript his soldiery from Swedish fields and forests and benefited from the fact that Swedish iron production began to boom in the 1620s, when Louis de Geer, a native of Liège and resident of Holland, dispatched Walloon ironworkers to Sweden to introduce newfangled blast furnaces to that remote land.5

De Geer did in Sweden what Wallenstein’s agent, DeWitte, had done in Bohemia. Each of them operated on a grand scale to import new financial and technical methods into formerly backward parts of Europe—backward at least by comparison to the standard set by the Low Countries. But in other respects they were quite different. De Geer remained domiciled in Holland and prospered as an international financier and entrepreneur, dependent on Gustav Adolf only for legal permission to do business in Sweden. He worked within the relatively well-defined moral and legal framework of Dutch business practice and handed his business to his heirs, whereas DeWitte left nothing but the tangled accounts of a bankrupt speculator when he committed suicide in 1630. Likewise, Gustav Adolf was legal sovereign and king, and suffered from none of the moral-legal dubiousness that surrounded Wallenstein’s entire career. As a result, the political and economic empires that De Geer and Gustav Adolf were able to create lasted for centuries, whereas Wallenstein’s collapsed with his assassination.

The Swedish king also owed part of his success in battle to the fact that he enthusiastically imported the latest Dutch methods of waging war and training troops. But he added some touches of his own, derived from his early experience with Russian and Polish cavalry tactics (war with Russia until 1617, with Poland 1621–29). As a result, when he intervened in the German wars by landing in Pomerania in 1630, the Swedish king brought into action a battle-hardened army. It proved its formidability at the Battle of Breitenfeld in 1631 when the Swedes first-exhibited their improved tactics.

Swedish tactical innovations aimed at more effective offensive action on the battlefield. Small field artillery pieces that could be maneuvered by hand added weight to volleyed small arms fire; and the shock effect of such massed fire was swiftly followed up by pike and cavalry charges. But Wallenstein adjusted his own tactics in imitation of the Swedes very promptly, as he demonstrated the very next year at the Battle of Lützen, where Gustav Adolf lost his life in winning a second victory over the imperial forces.

The rapidity with which one side reacted to any effective innovation from the other was convincingly illustrated by this episode. European kings and captains had clearly accepted the idea that improvements were always possible. An efficient information network utilizing printed texts as well as word of mouth, espionage, and commercial intelligence, spread data about enemy intentions and capabilities, new technologies, and new tactics across the length and breadth of western Europe. As a result, by the end of the Thirty Years War, European armies were no longer a mere collection of individually well-trained and bellicose persons, as early medieval armies had been, nor a mass of men acting in unison with plenty of brute ferocity but no effective control once battle had been joined, as had been true of the Swiss pikemen of the fifteenth century. Instead, a consciously cultivated and painstakingly perfected art of war allowed a commanding general, at least in principle, to control the actions of as many as 30,000 men in battle. Troops equipped in different ways and trained for different forms of combat were able to maneuver in the face of an enemy. By responding to the general’s command they could take advantage of some unforeseen circumstance to turn a stubbornly contested field into lopsided victory. European armies, in other words, evolved very rapidly to the level of the higher animals by developing the equivalent of a central nervous system, capable of activating technologically differentiated claws and teeth.

The third notable military-political structure which emerged from the Thirty Years War was French. After the peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, ending the Italian wars (1559), France had fallen prey to prolonged civil disturbances, partly inspired by religious quarrels between Calvinists and Catholics, and partly precipitated by an uncertain dynastic succession to the throne. The fact that employment in Italy had come to an end for French fighting men also had something to do with the repeated outbreaks of domestic disorder, since unemployed and restless soldiers could be counted on to respond eagerly to any occasion for the exercise of their profession. Internal broils distracted the royal government as late as 1627–28, when Louis XIII’s armies besieged and conquered the Calvinist stronghold of La Rochelle. Thereafter, French military resources were directed across the frontier, against the Hapsburg rulers of Spain and Germany. It was this French intervention in the Thirty Years War that finally frustrated the Catholic imperial effort to unite Germany and suppress heresy.

At first, French generals were inferior to the battle-experienced commanders of Spain and Germany; but by 1643, when the French defeated the Spaniards at Rocroi, the French too had achieved a level of skill in the art of war equivalent to the best in Europe. Thereupon the larger resources that the French king had at his command gave the Bourbon monarchy the capacity to eclipse any rivals, simply by putting larger and better-trained armies into the field. The political history of the second half of the seventeenth century turned on this elemental fact.

It hinged, also, on the fact that even after the Peace of Westphalia ended the war in Germany (1648), neither the Hapsburg emperor nor the French king found it wise or necessary to disband all the troops that had fought for them during the Thirty Years War. Indeed, since peace with Spain was not concluded until 1659, the French had to keep troops under arms until after that date; and in 1661 when the new king, Louis XIV, took power in person, he decided that glory and prudence alike required him to keep a standing army in perpetual readiness for war. The fact that civil disorder had broken out anew in France between 1648 and 1653 made a strong impression on young Louis. His standing army was initially designed to assure the king’s superiority over any and every challenge to his authority from within France, and only secondarily intended for foreign adventure.

Improvements in the Control of Armies

The successful suppression of the Fronde, as this final round of old-fashioned civil disorder in France was called, marked a significant turning-point in the history of European war and statecraft. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that it marked the time at which transalpine states finally caught up with the level of administrative management and control over armed force that had been attained in Venice and Milan two centuries earlier. The fact is that nearly every aspect of French and Austrian management of their armed establishments in the second half of the seventeenth century had been anticipated by Venice and Milan. Civilian control of supply, regular payment of the soldiers with money derived from tax revenues, along with differentiation and tactical coordination of infantry, cavalry, and artillery all were shared between fifteenth-century Italian city-states and seventeenth-century transalpine monarchies. Even the work of Louis XIV’s famous minister, Michel Le Tellier, and his son, the Marquis de Louvois, secretary of state for war, in supplying the French army, regularizing its structure, and standardizing equipment, can be closely paralleled by the work of a little-known Venetian provedditore, Belpetro Masselini (in office 1418–55), who did the same for the troops that defended the Republic of St. Mark.6

One aspect of the new standing armies of northern Europe, however, was without clear parallel in earlier times, and its importance was such as to deserve rather special consideration here. For Louvois was assisted in his efforts to manage the royal army by an itinerant inspector, Lieutenant Colonel Martinet, whose name passed into the English language as a symbol of rigorous insistence on details of discipline. This, indeed, was what Martinet excelled in. Instructions from Louvois issued in 1668 required him to do no less.

. . . you ought to order them [designated infantry officers] to be on hand every day when the guard changes, and, before it disperses, to exercise the soldiers in the manual of arms and various movements to the left and right and forward to teach them to march well in small units.7

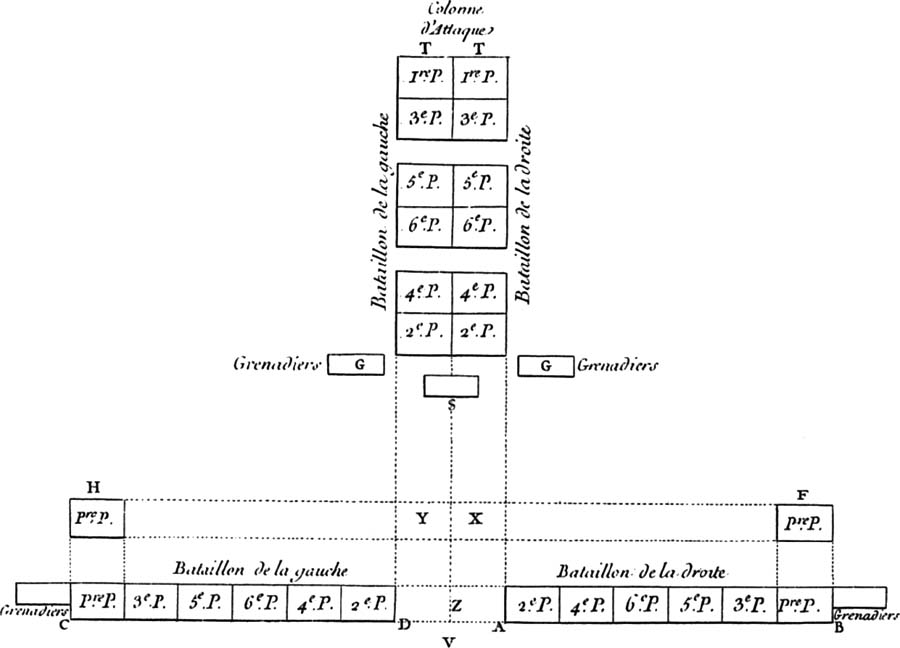

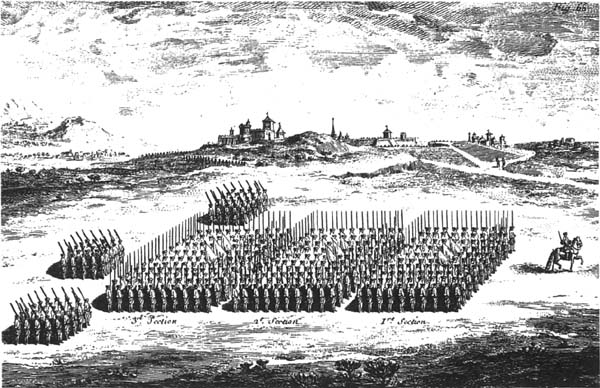

Close Order Marching as Practiced in the Eighteenth Century

To march well and deploy large numbers of men swiftly into prescribed formations took endless practice. The diagram at top shows how a regiment, subdivided into two battalions and twelve platoons, ought to shift from line formation to column of attack; and the etching below shows the regiment ready to advance against the foe after completing the maneuver. Such drill had powerful psychological impact on soldiers subjected to it, creating sentiments of solidarity and esprit de corps in a fashion drillmasters only dimly comprehended.

Denis Diderot, A Diderot Pictorial Encyclopedia of Trades and Industry, edited by Charles Coulston Gillispie (New York: Dover Publications, 1959; vol. 1, pl. 67). Facsimile reproduction from original Paris edition of 1763.

Of course, Louvois’ concern with marching well was not entirely new. But the history of drill in European armies before the turn of the seventeenth century is very obscure. Swiss and Spanish pikemen in their “hedgehogs” marched to the tap of drum,8 and certainly strove to keep a tight formation in the field so as to leave no gaps for attacking cavalry to penetrate. Other infantry forces also marched in formation, as had been true in antiquity as far back as the Sumerians. But drill, day in and day out, practiced year round when on garrison duty, and occupying spare time even when on campaign and in the field, was something earlier armies had not, so far as one can tell, found either necessary or sensible. Yet insofar as Louvois and his agent, Colonel Martinet, were successful in making their will obeyed by French officers and troops, routine drill became the daily experience of soldiers coming off guard duty. One may well ask why.

The answer is that by Louvois’ time two generations of European commanders had discovered that drill made soldiers both more obedient and more efficient in battle. The person principally responsible for developing modern routines of army drill was Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange (1567–1625), captain-general of Holland and Zeeland between 1585 and his death, and of the forces maintained by other Dutch provinces for varying periods of time. Maurice was a university man, trained in mathematics and classics. Confronted by the problem of fighting the Spaniards in the Low Countries, he looked to the Roman past for models and sought to distill lessons in the art of war from the pages of Vegetius, Aelian,9 and other classical authors.

Prince Maurice did not imitate Roman precedents slavishly; he did, however, emphasize three things that had not been common in European armies before his time. One was the spade. Roman soldiers had habitually fortified their encampments with makeshift earthen ramparts. Maurice did the same, and in particular made his soldiers dig themselves in when besieging enemy-held towns and forts. Digging had not been much emphasized by European armies before his time. To take refuge behind a wall or by burrowing in a ditch carried a taint of cowardice; and armies usually relied on conscripted laborers from the neighborhood to do most of the digging that was judged needful. For Prince Maurice’s troops, however, the spade was mightier than the sword—or musket. By systematically digging ditches and erecting ramparts to defend its outer perimeter, a besieging army could protect itself against a relieving expedition while continuing to press the siege. Following this regimen, Maurice’s armies suffered fewer casualties from defenders’ fire, while burrowing steadily forward, closer and closer to the defended ditch and wall, until a final assault became practicable. A siege became a matter of engineering, i.e., of moving vast quantities of earth. Handling the spade became the besieging soldiers’ daily occupation. Heavy work of that kind had the incidental effect of almost banishing idleness and dissipation, the usual pastime of earlier armies when besieging a strongpoint. Prince Maurice, in fact, earnestly disapproved of idleness; when his soldiers were not digging, they were kept busy drilling instead.

The development of systematic drill was the second and by far the most important innovation Maurice introduced on the basis of Roman precedents. He compelled his soldiers to practice the motions required to load and fire their matchlocks; pikemen likewise had to practice the positions in which pikes should be held when marching and in battle. This kind of instruction was not entirely new. Armies had always had to train recruits, but earlier drillmasters acted on the not unreasonable assumption that as soon as everyone knew how to use his weapon, their task had been accomplished. Maurice differed from his predecessors in being far more systematic. He analyzed the rather complicated movements required to load and fire matchlock guns10 into a series of forty-two separate, successive moves and gave each move a name and appropriate word of command. His soldiers could then be taught to make each movement in unison, responding to a shouted word of command. Since all the soldiers moved simultaneously and in rhythm, everyone was ready to fire at the same time. This made volleys easy and natural, creating a shock effect on enemy ranks. More important, soldiers loaded and fired their guns much faster and were much less likely to omit any of the essential steps. The result was to make handguns more efficient than ever before, and Maurice increased their number in proportion to pikes accordingly.

He also regularized marching. By keeping in step, all the men in a unit could be taught to move in prescribed patterns, forward or back, left or right, shifting from column to line and back again. The most important maneuver of Prince Maurice’s drill was the countermarch, whereby, having fired their weapons, a rank of arquebusiers or musketeers marched between the files of the men standing behind them, and proceeded to reload in the rear while the men in the next rank were firing their pieces. With practice, and with an appropriate number of ranks, by the time the first rank’s guns were again fully loaded, each of the other ranks had fired and retired in its turn, allowing the soldiers of the first rank to fire their second volley without obstruction or delay. In this fashion, a well-choreographed military ballet permitted a carefully drilled unit to deliver a series of volleys in rapid succession, giving an enemy no chance to recover from the shock of one burst of fire before another volley hit home. The trick was in the timing, and in preventing men from fleeing the battlefield entirely when they turned their backs on the enemy in order to reload in the rear. Oft-repeated drill, making every movement semiautomatic, minimized the possibility of breakdown. Closer supervision of the rank and file by an expanded cadre of officers and noncoms was also necessary to make the countermarch practicable. But when everything went as intended, the pay-off was spectacular.

Maurice’s third reform both made drill more effective and was itself made effective by repeated drill: to wit, he divided his army into smaller tactical units than had been customary before, in imitation of the maniples of the Roman legion. Battalions of 550 men, further subdivided into companies and platoons, made convenient units for drill, since a single voice could control the movements of all the men. Primary personal ties, extending from commanding officer to newest recruit, could also establish themselves among the members of units of this size. They could move nimbly on a battlefield, acting independently yet in coordination with each other, since an unambiguous chain of command extended from the general in charge of the battle to the noncom in charge of each rank of each platoon. Commanders at each level in the hierarchy, at least in principle, responded to orders coming from above, transmitting them to appropriate subordinates with whatever additional specification the situation might require.

In this way an army became an articulated organism with a central nervous system that allowed sensitive and more or less intelligent response to unforeseen circumstances. Every movement attained a new level of exactitude and speed. The individual movements of soldiers when firing and marching as well as the movements of battalions across the battlefield could be controlled and predicted as never before. A well-drilled unit, by making every motion count, could increase the amount of lead projected against an enemy per minute of battle. The dexterity and resolution of individual infantrymen scarcely mattered any more. Prowess and personal courage all but disappeared beneath an armor-plated routine. Soldiering took on quite new dimensions and the everyday reality of army life altered profoundly. Yet troops drilled in the Maurician fashion automatically exhibited superior effectiveness in battle. As this came to be recognized, the old irregular and heroic patterns of military behavior withered and died, even among the most recalcitrant officers and gentlemen.

Efficiency in battle was important, but less significant than the improved efficiency a well-drilled army also exhibited in garrison and siege situations. Nearly all of a soldier’s time, after all, was spent in anticipation of actual confrontation with an enemy. How to wait without becoming restless and unmanageable had always been a problem for earlier armies. When marching cross-country the problem solved itself. But when an army settled down in a single location, doing nothing for days or months on end, morale and discipline were very liable to break down. The fact that a few hours of daily drill were easy to organize, obviously useful, and readily enforceable made garrison discipline easy to maintain.11

Moreover, such drill, repeated day in and day out, had another important dimension which the Prince of Orange and his fellows probably understood very dimly if at all. For when a group of men move their arm and leg muscles in unison for prolonged periods of time, a primitive and very powerful social bond wells up among them. This probably results from the fact that movement of the big muscles in unison rouses echoes of the most primitive level of sociality known to humankind. Perhaps even before our prehuman ancestors could talk, they danced around camp fires, rehearsing what they had done in the hunt and what they were going to do next time. Such rhythmic movements created an intense fellow feeling that allowed even poorly armed protohumans to attack and kill big game, outstripping far more formidable rivals through efficient cooperation. By virtue of the dance, supplemented and eventually controlled by voice signals and commands, our ancestors elevated themselves to the pinnacle of the food chain, becoming the most formidable of predators.

Military drill, as developed by Maurice of Nassau and thousands of European drillmasters after him, tapped this primitive reservoir of sociality directly. Drill, dull and repetitious though it may seem, readily welded a miscellaneous collection of men, recruited often from the dregs of civil society, into a coherent community, obedient to orders even in extreme situations when life and limb were in obvious and immediate jeopardy. Hunting bands had depended for their survival on being able to sustain obedience and cooperation in the face of imminent peril. Presumably, therefore, natural selection across unnumbered generations had raised human aptitude for such behavior to a high level; and these aptitudes continued (and continue) to lurk near the surface of our subconscious psyche.

The armies of ancient Greece and Rome had also drawn on this instinctual reservoir to bind their citizen soldiers together. The peculiar intensity of city-state political life depended in no small degree on this phenomenon. So when Maurice of Nassau looked back to the practices of the Roman legions and modified their pattern of drill to fit the hand-weapons of his day, he was grafting his management of armed force onto an ancient and well-tested European tradition.

The new drill therefore drew upon literary tradition to exploit very powerful human susceptibilities. Military units became a specialized sort of community, within which new, standardized face-to-face relationships provided a passable substitute for the customary patterns of traditional social groupings—the very groupings which were everywhere dissolving or were at least called into question by the spread of impersonal market relations. Hence, the artificial community of well-drilled platoons and companies could and did very swiftly replace the customary hierarchies of prowess and status that had given European society its form and its capacity for local self-defense in the days when knighthood had been in flower.

Social bonds among soldiers were strengthened further by the fact that from the age of Louis XIV standing armies encouraged long-term enlistment and reenlistment. Once assigned to a particular unit, a soldier might therefore spend many years in the ranks, sharing experiences with long-time comrades who disappeared more often through death than from choice. This allowed sentiments of group solidarity to become firmly fixed, and transformed small army units into effective primary communities.

As suggested above, the breakdown of primary communities as a basis for military action was what had precipitated the initial Italian venture into mercenary soldiering in the fourteenth century. Two centuries afterwards, European drillmasters managed to create artificial primary communities in the ranks of all technically proficient armies, thanks to the remarkable way in which a few weeks of drill created sentiments of solidarity, even among previously isolated individuals. The emotional tone thus aroused within the ranks of European armies in turn relieved the psychological strains and stresses that had made military management so difficult in the centuries of transition from one kind of primary community to the new one.

Well-drilled armies were usually quite insulated from the larger social context in which they found themselves. New recruits, coming directly from villages, could be fitted into the artificial community of the company and platoon with minimal psychological adjustment. For drill swiftly and dependably transformed obedience and deference defined by custom into obedience and deference defined by regulations. Armies were, therefore, readily renewable, and preserved “old-fashioned,” i.e., rural, values and attitudes within an ever more drastically urbanized, monetized, commercialized, and bureaucratically rationalized world.

Such a combination of opposites, or seeming opposites, created more effective instruments of policy than the world had ever seen before. Conformity to rules laid down from above became normal, not only because men feared harsh punishments for infractions of discipline, but also because the rank and file found real psychological satisfaction in blind, unthinking obedience, and in the rituals of military routine. Prideful esprit de corps became a palpable reality for hundreds of thousands of human beings who had little else to be proud of. Human flotsam and jetsam found an honorable refuge from a world in which buying and selling had become so pervasive as to handicap severely those who lacked the necessary pecuniary self-restraint, cunning, and foresight. An artificial community bureaucratically structured and controlled, came into existence, based on deep-seated, stable, and very powerful human sentiments. What an instrument in the hands of statesmen, diplomats, and kings!

The feats of arms that European armies routinely performed, once drill had become soldiers’ daily experience, were in fact quite extraordinary. Being heirs of the European past, we are likely to take their acts for granted and lose the sense of wonder they properly deserve. Yet consider how amazing it was for men to form themselves into opposing ranks a few score yards apart and fire muskets at one another, keeping it up while comrades were falling dead or wounded all around. Instinct and reason alike make such behavior unaccountable. Yet European armies of the eighteenth century did it as a matter of course.

Equally remarkable was the way in which army units obeyed the will of invisible superiors with about equal precision, whether they were located over the nearest hill crest or half the globe away. Many thousands of men who had no obvious personal stake in fighting one another and did have very obvious personal reasons for wishing to be out of the other fellows’ line of fire nevertheless did what they were commanded to do—routinely. As a result, bureaucratically appointed officers, regardless of their personal competence or incompetence, expected and received automatic and obedient response to their commands, almost without fail, and regardless of what part of the globe they happened to find themselves assigned to.

The creation of such a New Leviathan—half inadvertently perhaps—was certainly one of the major achievements of the seventeenth century, as remarkable in its way as the birth of modern science or any of the other breakthroughs of that age.12

The improved efficiency aroused by drill soon became apparent to other military men of Europe. Prince Maurice’s reputation rested on his recovery of dozens of fortified towns from the Spaniards through sudden strikes and obdurate sieges, each conducted with a technical precision and dispatch never attained before. Maurice’s methods of training were not kept secret. In 1596 his cousin and close collaborator, Johannes II of Nassau, commissioned an artist named Jacob de Gheyn to produce drawings illustrating each of the postures that arquebusiers, musketeers, and pikemen were required to take by the new drill. These were published as a book in 1607. A full folio page was devoted to each posture, together with the appropriate word of command. An apprentice drillmaster—or common soldier—could thus see with his own eyes just how to perform the drill.13

Maurice organized a military academy for the training of officers in 1619—another first for Europe. A graduate of Prince Maurice’s academy subsequently took service with Gustav Adolf of Sweden and brought the new Dutch drill to that army. From the Swedes the new drill (variously modified of course) spread to all the other European armies with any pretension to efficiency. Protestant states accepted the innovation first; from them it spread to the French, and last of all to the Spaniards, whose attachment to their own long-victorious tradition was naturally very great. But after the Battle of Rocroi (1643), when a French army defeated the Spanish tercios in open country, informed military men of Europe all agreed that the new drill had definitely proved superior to Spanish practices.

To the east, the Russians soon took note, and in 1649, a generation after the new drill books had first appeared in German, a Russian translation came out.14 Romanoff armies thus tried to keep step with developments in western Europe, though they still lagged noticeably behind. The Turks, however, refused to believe that infidels could improve on time-tested Moslem methods of training and deployment. Even after a long series of defeats in the field proved otherwise (1683–99, 1714–18), a belated attempt to train troops in European fashion merely provoked a successful mutiny by the janissaries in 1730. Not until after almost another century of military disaster did the sultan finally succeed in destroying the janissary corps in 1826 as a preface to modernizing training and tactics. But by that time the morale and cohesion of the Ottoman body politic had suffered irreparable damage. Consequently, efforts to catch up with European military methods could not prevent further defeat and the ultimate dissolution of the empire in 1918.15

Further east, the new style of training soldiers became important when European drillmasters began to create miniature armies by recruiting local manpower for the protection of French, Dutch, and English trading stations on the shores of the Indian Ocean. By the eighteenth century, such forces, however minuscule, exhibited a clear superiority over the unwieldy armies that local rulers were accustomed to bring into the field. As a result, the great European trading companies became territorial rulers over expanding areas in India and Indonesia.16 Only the Pacific shores of Asia remained insulated from the enhanced efficiency of European troops—until 1839–41.

In earlier times one of the dilemmas that had surrounded European soldiering was the discrepancy between technical efficiency, which from the fourteenth century had favored predominantly infantry armies, and the established hierarchy of civil society. An infantry force recruited from the lower classes might be expected to challenge aristocratic dominance. The Swiss had done so, triumphantly, on their home ground in the fourteenth century. Egalitarian ideas also cropped up recurrently among the German Landesknechten.17

Musket Drill Devised by Maurice of Orange

11, Hold up your musket and present

12, Give fire

13. Take down your musket and carry it with your rest

14. Uncock your match

15, And put it again bewixt your fingers

16, Blow your pan

24, Charge your musket

25, Draw out your scouring stick

The engravings on the following pages show eight of a total of forty-three positions prescribed for Maurice of Orange’s musketeers. Getting powder, ball, and wadding securely into place and then priming the gun while holding a lighted match in the left hand demanded care and precision; to do it rapidly required repeated practice. These etchings were published to help drillmasters standardize each motion and thus speed up the soldiers’ rate of fire.

Wapenhandelinghe van Roers, Musquetten ende Spiessen, Achtervolgende de Ordre van Syn Excellentie Maurits, Prince van Orangie . . . Figuirlyck vutgebeelt door Jacob de Gheyn (The Hague, 1607; facsimile edition, New York: McGraw Hill, 1971).

European rulers’ initial response to this dilemma had been to hire foreign mercenaries for infantry service, since foreigners could be expected to exhibit minimal solidarity with the lower classes over whom the ruler in question exercised jurisdiction. The Swiss, egalitarian and self-governing at home, thus became a pillar of the French monarchy, helping to prop up an aristocratic-bureaucratic regime for more than three hundred years (1479–1789) against challengers both at home and abroad.18 Hillsmen and others coming from infertile areas, where a distinct landowning class had never securely established its power, played analogous roles in other parts of Europe, for example, the Albanians, Basques, and south Slavic Grenzers, together with Celts from Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. When the Swedes intervened in the Thirty Years War, they had something of the same character, though, of course, they acted on behalf of their own sovereign rather than as hirelings of a foreign ruler.19

Reliance on foreigners had obvious drawbacks, however. Before the eighteenth century, money was not usually available in anything like the amount needed to pay armed foreigners punctually. Chronically impecunious monarchs could not safely rely on an army that was prepared to quit the battlefield simply because its pay was overdue.20 But from the beginning of the seventeenth century, European rulers discovered how the sweepings of city streets and sons of poverty-stricken peasants could quite literally be made into new men by repeated drilling. Egalitarian ideas lost their resonance, save on those rare occasions when the drillmasters espoused such ideals, as happened briefly in some units of the Parliamentary armies during the English civil wars (1642–49), and again, much later, in the first phases of the French Revolution (1789–93). In more ordinary times, armies became self-perpetuating training institutions, drilling raw recruits until they became quite different from their former selves, that is, until they became soldiers.21

Various associated behavioral traits, transmitted from soldier to soldier across the decades, grew up around the central experience of drill to define a distinctive military style of life. Prostitutes, gambling, and drunkenness all had a place in this way of life; so did pride, punctilio, and prowess. European armies, in short, did not depart entirely from older patterns and precedents. But they did relegate some of the traditional aspects of military behavior to the margins, confining the more disruptive of them to off-duty hours.

The new psychic character of European armies made sharp class differentiation within civil society fully compatible with domestic peace and order. Overwhelming force came to reside in the hands of soldiers obedient to the king’s own bureaucratically appointed officers. Neither aristocratic challenges to royal power nor lower-class protests against perceived injustice had the slightest chance of success as long as well-drilled troops were available to defend royal prerogatives. Accordingly, Europe began to enjoy a previously unattainable level of domestic peace. This facilitated a notable increase in wealth, so that in many parts of the Continent it became feasible to support professional standing armies on tax income without straining the economic resources of the population too severely. The United Provinces, France, and Austria led the way; other European states followed close behind.

Standardization and Quasi-Stabilization of European Armed Forces

As tax income became sufficient to meet military payrolls more or less punctually, the profound disturbances that the commercialization of war had introduced into Europe in the fourteenth century seemed finally to have been brought under control. Ravaging soldiers no longer had to sustain themselves by forcibly recirculating the movable wealth of a country. Regular, predictable taxes did the trick instead, transferring money from civilians to officials who used it to support an efficient military force as well as themselves. It seems safe to suggest that only the continuance of interstate rivalries prevented this Old Regime pattern of society and government, which emerged after 1650, from settling down to centuries of routine.

Incipient stabilization of European patterns of war and society was also forwarded by another corollary of Prince Maurice’s reforms. For standardized drill presupposed standardized weapons. Maurice himself found it necessary, in 1599, to require that the armies under his command be equipped with uniform handguns. Otherwise his new system could not be made to work. Louvois did the same for the French army, and made soldiers look like soldiers as we know them in the twentieth century by presiding over the development of uniforms (which varied from regiment to regiment, however).

The short-run effect of such standardization was to reduce military costs significantly. Even artisan suppliers could cut the price of their product if assured of steady work manufacturing identical items indefinitely into the future. Supply in the field was also eased when only one caliber of musket ball was required. And since each soldier could be trained to the precise movements of standardized drill, reinforcement of the depleted personnel of any given unit became almost as simple as replacing spent musket balls. Soldiers, in short, tended to become replaceable parts of a great military machine just as much as their weaponry. Management of such an army was easier and more likely to achieve expected results than anything possible before. The cost of organized violence went down proportionally; or, perhaps it would be more accurate to say that the magnitude and controllability of such violence per tax dollar went up—spectacularly.22

Over a somewhat longer run, however, uniformity of weaponry among scores of thousands of soldiers introduced a new kind of rigidity into the arms market. Once an entire army had standardized its equipment, any improvement in design became far more costly to introduce than had been the case when the weapons of dozens of different designs were simultaneously in use. Military purchasers had to choose between technical improvement and the costs that would arise from loss of uniformity. Not all changes were inhibited by this new dilemma. Still, really important departures from existing designs of weapons were certain to upset established patterns of drill, training, and supply. As a result, changes in handguns, which had been very rapid from the fifteenth to seventeenth century, almost came to a halt after about 1690, when the invention of the ring bayonet made it possible to combine firepower with close-in defense against cavalry for the first time, rendering pikemen unnecessary.23

By that time, to be sure, the handguns in use by European armies had attained a satisfactory degree of reliability, simplicity,24 and durability so that improvements in design were, perhaps, more difficult to achieve than in earlier ages. But what froze infantry weapons at a given level was resistance to any change that would require a choice between the advantages of uniformity and the cost of reequipping an entire army. This rational calculation was reinforced by affectionate attachment to familiar weapons and routines. Reason and sentiment thus conspired to make the musket designed in England in 1690, and nicknamed “Brown Bess,” the standard infantry weapon of the British army until 1840. It underwent only minor modification in all that time.25 Other European armies were almost as conservative. And since foot soldiers remained decisive in battle across this entire span of time, the stabilization of infantry weapons had the effect of stabilizing tactics, training, and other aspects of army life.

Stabilization was never complete, as we will see in the next chapter; but it seems clear that as Prince Maurice’s patterns of training and administration took hold across the face of Europe, the great surge of change in Europe’s management of organized violence that we have considered in this and the preceding chapter came to a close.

We may sum it up as follows: things started to change in the twelfth century with the rise of infantry forces capable of challenging the supremacy of mounted knights on Italian battlefields. Town militias gave way to hired professionals in the fourteenth century, and a pattern of political management of standing armies swiftly evolved within the context of the emergent city-states of Italy during the first half of the fifteenth century, only to be upset by the irruption of French and Spanish armies after 1494. Then a reprise of the Italian development on a territorially larger scale began in transalpine Europe, achieving a pattern reminiscent of Italian city-state administration by the mid-seventeenth century, when tax income and military-naval expenditure came into more or less stable relation to each other in such countries as France, the United Provinces, and England. But the northern Europeans improved on Italian precedents in two important respects: by developing systematic, oft-repeated drill, and by constructing a clear chain of command that extended from the person of the sovereign—usually a king—to the lowliest noncommissioned officer. Jealousies within the chain of command were never completely eliminated; but the sacred aura that continued to surround royal personages made the “divide and rule” policy that Venetian magistrates and Milanese administrators had relied on to govern military professionals unnecessary in transalpine Europe.

Stability at home meant formidability abroad. Within the cockpit of western Europe, one improved modern-style army shouldered hard against its rivals. This led to only local and temporary disturbances of the balance of power, which diplomacy proved able to contain. Towards the margins of the European radius of action, however, the result was systematic expansion—whether in India, Siberia, or the Americas. Frontier expansion in turn sustained an expanding trade network, enhanced taxable wealth in Europe, and made support of the armed establishments less onerous than would otherwise have been the case. Europe, in short, launched itself on a self-reinforcing cycle in which its military organization sustained, and was sustained by, economic and political expansion at the expense of other peoples and polities of the earth.

The modern history of the globe registered that fact, and turned in large measure on the further fact that technical and organizational improvements in European management of organized violence did not come permanently to a halt in the seventeenth century, despite the new precision and rigidity that European armies achieved by that time. Instead, technological and organizational innovation continued, allowing Europeans to outstrip other peoples of the earth more and more emphatically until the globe-girdling imperialism of the nineteenth century became as cheap and easy for Europeans as it was catastrophic to Asians, Africans, and the peoples of Oceania.

The succeeding chapters of the book will address themselves to these changes.