The Era of Chinese Predominance, 1000-1500

Remarkable changes came to Chinese industry and armaments after about A.D. 1000, anticipating European achievements by several hundred years. Yet new patterns of production, even when they had attained massive scale, eventually broke up as remarkably as they had arisen. Government policy altered, and the social context that first fostered change subsequently resisted or at least failed to encourage, further innovation. China therefore lost its leading place in industry, power politics, and war. Previously marginal, half-barbarous lands—Japan to the east and Europe far to the west—supplanted the Mongol rulers of China as the most formidable wielders of weapons in the world.

Yet before China’s preeminence over other civilizations faded, a new and powerful wind of change began to blow across the southern seas that connected the Far East with India and the Middle East. I refer to an intensified flow of goods and movement of persons responding mainly to market opportunities. In seeking riches or a mere livelihood, a growing swarm of merchants and peddlers introduced into human affairs far more pervasive changeability than earlier centuries had ever known.

China’s remarkable growth in wealth and technology was based upon a massive commercialization of Chinese society itself. It therefore seems plausible to suggest that the upsurge of market-related behavior that ranged from the sea of Japan and the south China seas to the Indian Ocean and all the waters that bathe the coasts of Europe took decisive impetus from what happened in China. In this fashion, one hundred million people,1 increasingly caught up within a commercial network, buying and selling to supplement every day’s livelihood, made a significant difference to the way other human beings made their livings throughout a large part of the civilized world. Indeed, it is the hypothesis of this book that China’s rapid evolution towards market-regulated behavior in the centuries on either side of the year 1000 tipped a critical balance in world history. I believe that China’s example set humankind off on a thousand-year exploration of what could be accomplished by relying on prices and personal or small-group (the partnership or company) perception of private advantage as a way of orchestrating behavior on a mass scale.

Obedience to commands did not of course disappear. Interaction between command behavior and market behavior lost none of its complex ambivalence. But political authorities found it less and less possible to escape the trammels of finance, and finance depended more and more on the flow of goods to markets which rulers could no longer dominate. They, too, like humbler members of society, were more and more trapped in a cobweb of cash and credit, for spending money proved a more effective way of mobilizing resources and manpower for war and for other public enterprises than any alternative. New forms of management and new modes of political conduct had to be invented to reconcile the initial antipathy between military power and money power; and the society most successful in achieving this act of legerdemain—western Europe—in due season came to dominate the world.

Europe’s rise will be the theme of the next chapters. This one seeks to examine the springs and limits of China’s transformation, and its initial impact on the rest of the world.

Market and Command in Medieval China

In trying to understand what put China in the lead, and how its technological headstart on the rest of the civilized world crumbled away, one soon runs into difficulty. Historians of China have yet to work through the voluminous records from the T’ang (618–907), Sung (960–1279), Yüan (1260–1368), and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties with the appropriate questions in mind. A generation or more will be required before they can attain a clear vision of the regional variations and social and economic transformations of China that underlay the rise and decay of a high technology iron and coal industry and of a naval hegemony that extended briefly throughout the Indian Ocean. In the meanwhile, active hypothesis is all that can be hoped for.2

All the same, scholars working in the field have assembled some startling data about Chinese accomplishments. Robert Hartwell, for example, in three remarkable articles,3 has traced the history of iron-working in north China in the eleventh century. The technical basis of the large-scale development that then occurred was already old in China. Blast furnaces, using an ingenious bellows that produced a continuous flow of air, had been known for up to one thousand years4 before the ironmasters of north China began to fuel such furnaces with coke during the first decades of the eleventh century, thereby solving a persistent fuel problem in the tree-short landscape of the Yellow River valley. Coke, too, had been used for cooking and domestic heating for at least two hundred years before being put to use in ferrous metallurgy.5

Yet even if the separate techniques were old, the combination was new; and once coke came to be used for smelting, the scale of iron and steel production seems to have surged upward in quite extraordinary fashion, as the following figures for iron production in China show:6

| Year | Tons | |

| 806 | 13,500 | |

| 998 | 32,500 | |

| 1064 | 90,400 | |

| 1078 | 125,000 |

Such statistics are of course derived from official tax records, and may therefore systematically underestimate production, since small-scale “backyard” smelting must sometimes have escaped official notice. On the other hand, growth may be partly a statistical artifact, if for some reason or other official concern with iron and steel production became more energetic in the eleventh century.7 Yet even if this apparent growth is partly a matter of more thorough reporting, Hartwell has shown that within a relatively small region of north China, on or adjacent to bituminous coal fields (suitable for coking) in northern Honan and southern Hopei, production went from nothing to 35,000 tons per annum by 1018. Large-scale enterprises arose in these locations, employing hundreds of full-time industrial laborers, whereas iron smelting in other parts of China seems usually to have remained a part-time occupation for peasants who worked as ironmakers in the agricultural off season.

The new scale of enterprise could flourish only when there was a ready market for large amounts of iron and steel. That in turn depended on transportation, and on price relationships that made it attractive for families (perhaps, as Hartwell suggests, originally landowners) to build and manage the new metallurgical establishments. For about a century, these conditions did coexist. Canals connected the capital of the northern Sung dynasty, K’ai-feng, with the new iron and steel producing centers in Honan and Hopei; and the capital constituted a vast market for metal. Iron was used for coinage,8 for weapons, in construction, and for tools. Government officials supervised minting and weapons manufacture closely and in 1083 saw fit also to monopolize the sale of agricultural implements made of iron.

Chinese history offered ample precedent for this decision. Ever since Han times (202 B.C.–A.D. 220) iron had rivaled salt as a commodity attracting official attention. By monopolizing the distribution of these two materials, and selling them at arbitrarily heightened prices, state revenue could readily be enlarged. The decision of 1083 thus represented a reversion to old, well-established patterns of taxation,9 though one may readily believe that resulting high prices may have inhibited the expansion of private, civilian uses for iron and steel, and thereby helped to check any further growth of production.

Hartwell has not tried to estimate the end uses to which Chinese iron and steel were put in the eleventh century. Only scattered data survive. A single order for 19,000 tons of iron to make currency pieces, and a mention of two government arsenals in which 32,000 suits of armor were produced each year, give a glimpse of the scale of government operations in K’ai-feng in the late eleventh century when iron from the new foundries was pouring into the capital at an ever increasing rate. But such information does not permit any estimate of how much went into armaments as against coinage, construction, and the decorative arts.10 How much iron and steel escaped governmental manufactories and entered the private sector also remains unknowable, though Hartwell believes some did.

Even if the decision in 1083 to monopolize the sale of agricultural implements made of iron resulted in restricted production, it is worth pointing out that official management of the economy in medieval China had attained a good deal of self-consciousness and sophistication. The theory was concisely expressed by Po Chü-i (ca. 801) as follows:

Grain and cloth are produced by the agricultural class, natural resources are transformed by the artisan class, wealth and goods are circulated by the merchant class, and money is managed by the ruler. The ruler manages one of these four in order to regulate the other three.11

Currency management took on modern characteristics. Paper money had been introduced in parts of China as early as 1024; later, by 1107, the practice was extended to the capital region itself.12 A shift from taxes in kind to taxes in money gained rapid headway. According to one calculation, annual tax receipts in cash rose from sixteen million strings of cash early in the Sung dynasty (i.e., soon after A.D. 960) to about sixty million per annum in the decade 1068–78.13 By that time more than half of the entire governmental income probably took the form of cash payments.14

Obviously, such changes registered far-reaching alteration in society and the economy, at least in the most developed parts of China. What seems to have happened was that with the improvement of transport, through canal building and removal of natural obstacles to navigation in streams and rivers, local differences in landscape and resources allowed even the very humble to specialize their production. Agricultural yields rose markedly as diverse crops suited to differing soils and climates began to supplement one another. Improved seed and systematic application of fertilizers also worked wonders. Innumerable peasants began to supplement what they produced for their own support by buying and selling in local markets. On top of this, part-time artisanal activity eked out agricultural income for millions. Proliferating market exchanges—local, regional, and trans-regional—allowed spectacular increases in total productivity, as all the advantages of specialization that Adam Smith later analyzed so persuasively came into operation.15

A rising level of population meant that poverty did not disappear. On the contrary, while some became rich by skillful manipulation of the market, others became paupers. Their plight became painfully conspicuous in the imperial capital and other cities. Impoverished rural folk swarmed into towns hoping for gainful employment, and begged or starved when it was not to be had. Efforts to organize public relief, beginning in 1103, were only sporadically effective, as a memorial of 1125 makes clear:

In winter the collapsing people are not being cared for. The beggars are falling down and sleeping in the streets beneath the imperial carriage. Everyone sees them and the people pity them and lament.16

Under the remorseless pressure of circumstance, therefore, even the humblest members of Chinese society were compelled to enter the market whenever they could, seeking always to increase their overall material well-being. As a writer of the early fourteenth century put it:

These days, wherever there is a settlement of ten households, there is always a market for rice and salt. . . . At the appropriate season, people exchange what they have for what they have not, raising or lowering the prices in accordance with their estimate of the eagerness or diffidence shown by others, so as to obtain the last small measure of profit. This is of course the usual way of the world. Although Ting-ch’iao is no great city, its river will still accommodate boats and its land routes carts. Thus it, too, serves as a town for peasants who trade and artisans who engage in commerce.17

Or again:

All the men of An-chi county can graft mulberry trees. Some of them take their living solely by sericulture. For subsistence it is necessary that a family of ten persons rear ten frames of silkworms. . . . Supplying one’s food and clothing by these means insures a high degree of stability. One month’s toil is better than a whole year’s exertion at farming.18

On top of such local exchanges, an urban hierarchy arose, starting with rural towns, then provincial cities, and rising to a few truly metropolitan centers located along the Grand Canal that connected the Yangtse valley with that of the Yellow River. At the apex, and dominating the whole exchange system, was K’ai-feng, the capital of the northern Sung.19 After 1126 the city of Hang-chou, at the other end of the Grand Canal, where the southern Sung dynasty established its headquarters, played a similarly dominating role.

Against this background of commercial expansion and agricultural specialization, the growth of the iron and steel production of the eleventh century seems less amazing. It was, indeed, only part of a general upsurge of wealth and productivity resulting from specialization of skills and fuller utilization of natural resources that intensifying market exchanges permitted and encouraged. Yet the vigorous pursuit of private advantage in the marketplace, especially when it allowed upstart individuals to accumulate conspicuous amounts of wealth, ran counter to older Chinese values. Moreover, these traditional values were firmly and effectually institutionalized in the government. Officials, recruited by examination based on the Confucian classics, habitually looked askance at the more flamboyant expressions of the commercial spirit. Thus, for example, a high official named Hsia Sung (d. 1051) wrote:

. . . since the unification of the empire, control over the merchants has not yet been well established. They enjoy a luxurious way of life, living on dainty foods and delicious rice and meat, owning handsome houses and many carts, adorning their wives and children with pearls and jades, and dressing their slaves in white silk. In the morning they think about how to make a fortune, and in the evening they devise means of fleecing the poor. . . . In the assignment of corvee duties they are treated much better by the government than average rural households, and in the taxation of commercial duties they are less rigidly controlled than commoners. Since this relaxed control over merchants is regarded by the people as a common rule, they despise agricultural pursuits and place high value on an idle living by trade.20

Since official doctrine held that the emperor “should consider the Empire as if it formed a single household,”21 the right of imperial officials to intervene and alter existing patterns of production and exchange was never in doubt. The only issue was whether a given policy was practically enforceable and whether it would serve the general interest. Confiscatory taxation of ill-gotten gains always smacked of justice and retribution. The all too obvious suffering of the poor reinforced the case against the rich merchants and ruthless engrossers of the market. Yet Sung officials recognized that indiscriminate resort to such a policy might cost the state dearly by diminishing tax revenue in future years. Officials therefore struggled to reconcile justice with fiscal expediency, and long-range with short-range advantage. For a while, in the eleventh century, their policies allowed rapid technological development and expansion of iron and steel production in geographically favored regions accessible to the capital. Hartwell has explored the truly spectacular result for us.

But large-scale commercial and industrial enterprises were vulnerable to decay for the same reasons that had caused them to burgeon. Interruption of communications with the capital or collapse of official demand for iron and steel products would be sure to disrupt the industry. Changes of tax rates or of prices paid by the government could choke off production—perhaps more slowly, but no less surely.

Assuredly, conditions did alter so that the growth of iron and steel production in the K’ai-feng economic region decayed in the twelfth century, but statistics disappear after 1078 because of gaps in surviving records. Forty-eight years later, in 1126, regular administration was disrupted when tribesmen from Manchuria, known as Jürchen, conquered K’ai-feng and set up a new regime in north China (the Ch’in dynasty). The defeated Sung withdrew to the south, making the Huai River the northern frontier of their shrunken domain. A century afterward Genghis Khan’s armies defeated the Jürchen (by 1226), and the victor assigned the area in which the ironworks lay to one of the Mongol princes as an appanage. Later when Genghis’ grandson, the founder of the Yüan dynasty, Kublai Khan, ascended the throne (1260) and undertook the conquest of southern China, direct imperial administration was again imposed on the iron-producing region of Hopei and Honan. Accordingly, it once more becomes possible to estimate output for the 1260s. By that time, iron production of this region had shrunk from a recorded peak of 35,000 tons per annum in 1078 to about 8,000 tons annually, and was exclusively consigned, as one might expect, to equip the Mongol armies with armor and weapons.22

The Yüan dynasty’s military demand for iron and steel did not, in and of itself, suffice to restore production to anything like the former level. One reason was the disruption of canal transportation in north China. This, in turn, was part of an enormous disaster that occurred in 1194, when the Yellow River broke through its restraining dikes and, after flooding vast areas of the most fertile land in north China, eventually found a new path to the sea. The work necessary to restore the canal system was never undertaken. Hence iron production in Honan and Hopei remained at relatively modest levels thereafter. By 1736 the once busy blast furnaces, coke ovens, and steel manufactories were abandoned entirely, even though plenty of coking coal remained at hand and beds of iron ore were not far distant. Production was not resumed until the twentieth century.

Clearly, information is too fragmentary to permit anyone to figure out exactly what happened, either in the period of expansion and technical breakthrough or in the period of constriction and decay. But it is clear that governmental policy was always critically important. The distrust and suspicion with which officials habitually viewed successful entrepreneurs meant that any undertaking risked being taken over as a state monopoly. Alternatively, it could be subjected to taxes and officially imposed prices which made the maintenance of existing levels of operation impossible. This is what seems to have happened to the technologically innovative ironworks in the north which, if they had continued to expand, would have been capable of supplying China with cheaper and far more abundant iron and steel than any other people of the world had hitherto enjoyed.

The abortion of coke-fired ferrous technology was the more remarkable considering that the army maintained by the northern Sung dynasty grew to be over a million men, and its appetite for iron and steel was enormous. Nevertheless, military demand was blunted by the fact that it could become effective only with the consent of governmental officials; and the civil officials who disdained captains of industry actively distrusted and feared captains of men, since organized military force constituted a well-recognized potential challenge to their control of Chinese society.

After the first years of reunification (in the 960s), which involved offensive campaigning, Sung military policy became strictly defensive. The main problem, as always, was how to keep the nomads across the northwestern frontier from raiding settled Chinese landscapes. Nomad cavalry could outstrip Chinese footsoldiers; but footsoldiers, armed with crossbows and stationed in fortified garrison posts thickly scattered throughout the frontier zone, could hold off cavalry attacks quite effectually. If a raiding party chose to bypass such defended places in order to penetrate deeper into China, the Sung government’s response was to rely initially on a “scorched earth” policy that aimed at bringing everything of value within city walls.23 If raiders lingered, the central imperial field army, normally stationed in the environs of the capital, could be sent to harass and drive back the intruders. The field army was partly a cavalry force; its role was as much to countervail and overawe potentially rebellious border units as to protect the interior from barbarian raiding.24

This strategy became inadequate only if raiding parties snowballed into really large invading armies and acquired the organization and weaponry needed to attack city walls with success. This is what happened in 1127 when the Jürchen conquered K’ai-feng. To guard against such disaster, Sung policy relied on diplomacy, buying immunity from raids with “gifts” to powerful barbarian neighbors. From a nomad chieftain’s point of view, luxury goods received as gifts in connection with diplomatic intercourse (in exchange, to be sure, for horses or other gifts from him to make the transaction symmetrical) often seemed better than the randomly assorted objects that could be secured by plunder.

From the viewpoint of Chinese officialdom, a passive defense policy had the advantage of making it easier to assure civilian dominance within China. An army that was assigned to garrison duty and seldom took the field for active campaigning could be kept in leading-strings by carefully regulating its flow of supplies. Civilian officials, charged with the duty of providing food and weapons to local military commanders, could in any dispute expect to balance one military leader off against another. This made it relatively easy to nip rebelliousness in the bud, should any military captain find himself tempted to bring armed force to bear on decision-making at imperial headquarters.25 If the cost was loss of field mobility and vulnerability to large-scale, well-organized nomad attack, the Sung authorities were willing to pay the price. Only so could civilian authority be assured within China; only so could the mandarins be sure of dominating all sides of Chinese life.

Two aspects of this situation seem worth comment. First, from the point of view of the ruling elite, the policy towards Chinese army commanders was not fundamentally different from their policy towards barbarian chieftains outside the imperial boundaries. Divide and rule, while pacifying undependable elements by assigning goods, titles, and ritual roles to military leaders, was the recipe the Sung officials followed, whether within or beyond China’s frontiers. Policy called for giving as little in the way of goods and prestige as was safe. The temptation for officials on the spot was always to divert wealth for personal and family uses, even if it meant risk of armed reaction, whether from within or from without imperial borders.

Military men and barbarian chieftains confronted precisely parallel temptations. Raiding or rebellion might bring immediate access to booty and plunder more valuable than anything they could ever wring out of the reluctant Chinese officials. On the other hand, such gains were risky and could not continue indefinitely. Everyone concerned had therefore always to weigh long-term benefit against short-term gain. Since judgments in fact fluctuated, this meant that even the most cunningly contrived defense system was potentially unstable. Very sudden changes in the balance of military force along the frontier were always possible, if border guards ceased to resist the barbarian enemies, or if those enemies were able to unite into really formidable armies and acquire the means of besieging and breaking into walled cities and defended strongpoints. The sudden victories won by the Jürchen after 1122, culminating in the capture of K’ai-feng just four years later, illustrate this inherent instability.26

In the second place, Sung official policy towards armed men and organized violence was not fundamentally different from governmental policy towards merchants and others who enriched themselves by skillful or lucky manipulation of the growing market system of China. Like organized resort to armed force, private riches acquired by personal shrewdness in buying and selling violated the Confucian sense of propriety. Such persons could be tolerated, even encouraged, when their activity served official ends. But to allow merchants or manufacturers to acquire too much power, or accumulate too much capital, was as unwise as to allow a military commander or a barbarian chieftain to control too many armed men. Wise policy aimed at breaking up undue concentrations of wealth just as an intelligent diplomacy and a well-designed military administration aimed at preventing undue concentrations of military power under any one command. Divide and rule applied in economics as much as in war. Officials who acted on that principle could count on widespread popular sympathy, since plundering armies and ruthless capitalists seemed almost equally detestable to the common people.

The technology of Chinese armament also lent itself to the maintenance of bureaucratic supremacy. Since Han times, and perhaps before, crossbows had been the principal missile weapon of Chinese armies.27 The crossbow had two salient characteristics. First, a crossbow was about as easy to use as a modern handgun. No special strength was needed to cock it. A longbow required years of practice to develop sufficient strength in thumb and fingers to draw the bow to its full arc, whereas once a crossbow had been cocked, all the archer had to do was to place the arrow in firing position, and sight along the stock until a suitable target came into view. A few hours of target practice allowed an ordinary man to use a crossbow quite effectively. Yet Chinese crossbows of the thirteenth century were lethal up to four hundred yards.28

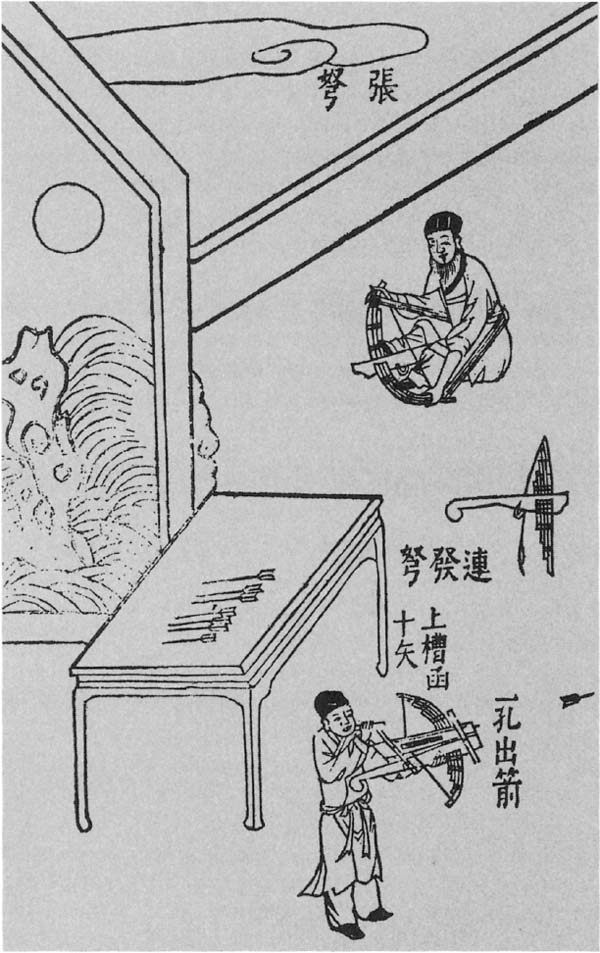

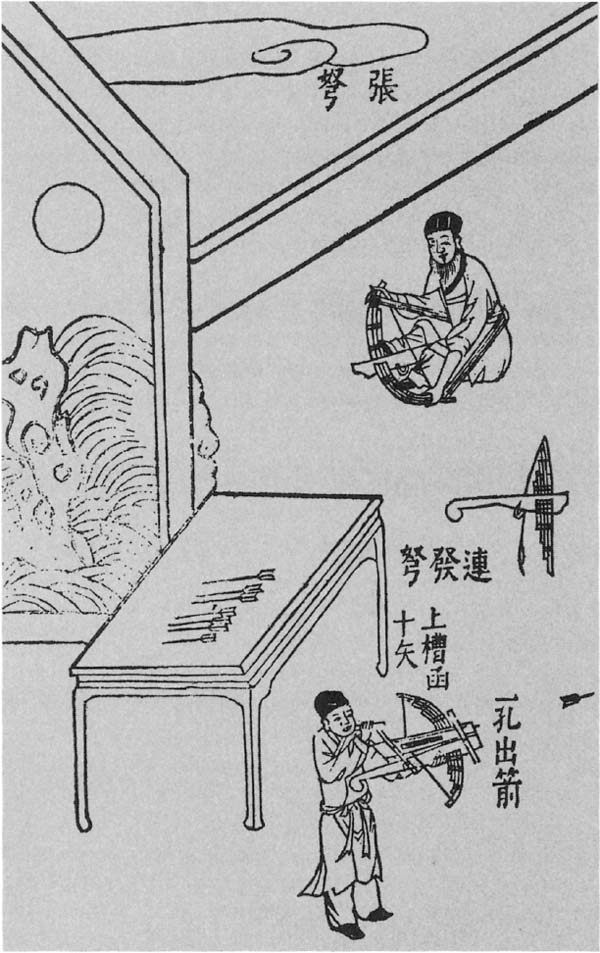

Chinese Crossbow Manufacture

This woodcut from a seventeenth-century encyclopedia shows how the arc was strengthened by lamination. In the figure below, the crossbow is shown with a magazine holding ten arrows. Cocking the bow released an arrow from the magazine, which then fell into shooting position. Details of the cocking and trigger mechanism do not show clearly, though these were the parts requiring most exact skill in manufacture.

Reproduced from Sung Ying-Hsing, T’ien-Kung K’ai-Wu, translated by E-tu Zen Sun and Shiou-Chuan Sun (University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1966), p. 266.

Second, the simple skill required for using a crossbow was counterbalanced by the high skill needed for its manufacture. An army of crossbowmen had to rely on expert artisans to produce precisely shaped trigger mechanisms and other necessary parts. Moreover, to supply such craftsmen with everything required to manufacture crossbows in large numbers was not easy. A powerful crossbow was compounded of laminated wood, bone, horn, and sinew, all cunningly fitted together to assure maximal springiness when bent out of its unstressed shape. The art of making such compound bows, however, was highly developed throughout the Eurasian steppelands. What distinguished crossbows was their trigger mechanism, which had to be made strong enough to withstand heavy stress when the bow was cocked and awaiting discharge. Only skilled artisans with access to appropriate supplies of metal could make a reliable trigger.29

A market economy, ranging across diverse landscapes, was better able to assure a suitable flow of the requisite materials into artisan workshops than any but the most efficient command economy. The same consideration applied to the varied machines for projecting stones, arrows, and incendiary materials with which Chinese armies of the eleventh century were also equipped.30 Explosive mixtures, including gunpowder, joined this array of complicated weaponry about the year 1000. Explosives were valued initially as incendiaries, but the Chinese began to exploit the propulsive power of gunpowder after about 1290, when the first true guns seem to have been invented.31

Chinese technical innovation, indeed, appears to have concentrated specially on weaponry in the Sung period. Technological advances among the barbarians perhaps impelled the Chinese to try to keep ahead. At any rate, before their conquest of north China in 1126, the Jürchen and other barbarian neighbors of China gained increasing access to products of Chinese artisanal skills. Improved armor and a greater supply of metal for weapons was the major symptom of this change. Clearly the Sung rulers faced a narrowing technical gap between themselves and their principal rivals—a gap that practically disappeared after the conquest of north China by the barbarians. Faced with this sort of threat, Sung authorities began systematically to reward military inventors, as the following passage illustrates:

In the third year of the K’ai Pao period of the reign of Sung Tai-Tse [i.e., A.D. 969] the general Feng Chi-Sheng, together with some other officers, suggested a new model of fire arrow. The Emperor had it tested, and (as the test proved successful) presents of gowns and silk were bestowed upon the inventors.32

With such patronage in high places, obstacles to innovation were minimized.

The city-based, defensive character of Sung strategy also encouraged technical experiment. It made sense to expend ingenuity and resources preparing complicated and powerful machines of war to defend city walls and other fixed positions, whereas such machinery initially was far too cumbersome for use by armies designed to take the field and move rapidly across open country. Only later, when catapults and gunpowder weapons had become really powerful, did the Mongols demonstrate that these devices could be used to break down city-gates and walls as well as to defend them.33

Successful administration of an army that grew to count more than a million men in its ranks, and that relied on complex weaponry to fend off more mobile attackers, obviously depended on the prior articulation of Sung China’s economy through market relationships, transport improvements, and technically competent administration. New patterns of recruitment into officialdom through examinations helped to assure a relatively proficient civilian management;34 but despite all the mandarins’ skills and wiles, the tasks of supplying the army may have strained the precarious balance between military and civilian command elements in Chinese society on the one hand and the newly ebullient market behavior of private persons on the other. The famous reform minister, Wang An-Shih (d. 1086) could write: “The educated men of the land regard the carrying of arms as a disgrace”; yet in the 1060s an official calculation revealed that 80 percent of the government’s income, fifty-eight million strings of cash, was necessary to support the million and more despised soldiers who garrisoned China.35 Concerned officials, seeking to economize on military expenditure, were in a position to throttle the ferrous metallurgy of Honan and Hopei simply by setting prices at uneconomic levels; but no one now knows whether this is actually what happened or whether something else disrupted the industry.

However costly their policies may have been in the long run, westerners in the twentieth century can surely sympathize with the problem Confucian officials faced in trying to balance one disturbing element—professionalized violence—against another equally disturbing element—professionalized pursuit of profit. Neither conformed to traditional propriety. Indeed, merchants and military men frequently flaunted their moral deficiencies with brazen unconcern for others. Uninhibited linkage between military and commercial enterprise, such as was to take place in fourteenth- to nineteenth-century Europe, would have seemed truly disastrous to Chinese officials. As long as men educated in the traditions of Confucian statecraft retained political authority, such a dangerous confluence would not be permitted. Instead, systematic restraints upon industrial expansion, commercial expansion, and military expansion were built into the Chinese system of political administration.

The career of a twelfth-century ironmaster named Wang Ko offers an instructive example in parvo of how the system worked, though obviously he represents an extreme case. Starting from nothing, Wang Ko became a rather considerable ironmaster in south-central China, with something like five hundred men in his employ. His furnaces used charcoal, not coke; indeed, his initial start came from getting possession of a tree-covered mountainside where charcoal could be produced. For reasons not clearly stated in the surviving record, Wang Ko quarreled with local officials in 1181. When they sent a detachment of soldiers to enforce their will, he mobilized his workmen to beat them off, and then followed up with an attack on the town where the officials resided. But his workmen deserted him; he had to flee, and was later caught and executed.36 Such a career shows how economic entrepreneurship and irregular exercise of armed force could merge into one another; and how entrenched officialdom enforced its will against both forms of impropriety.

Yet going over to a cash basis for government finance in the eleventh century risked infection of officialdom itself by the commercial mentality. This became most clearly apparent in south China. South of the Yangtse, a mountainous topography hindered transport by canals and riverways. Merchants had therefore to take to the open sea, and once sea trade among Chinese coastal provinces became well established, it was easy to extend trade relations to more distant parts. Indeed, commerce with populations that were not subject to imperial administration could be made to contribute handsomely to governmental income through excise taxes. Officials managing such taxes sometimes sought to promote overseas trade in a spirit reminiscent of mercantilist Europe, and might even invest government funds in ventures that promised to increase income and bring back rare and valued goods. In words attributed to the emperor himself: “The profits from maritime commerce are very great. If properly managed they can be millions. Is it not better than taxing the people?”37 The emperor knew whereof he spoke, for by 1137 something like a fifth of his government’s income came from excise taxes on maritime trade.38

This partial coalescence between mercantile and official outlooks reached its apogee under the Mongols (the Yuan dynasty, 1227–1368), who did not share the Confucian disdain for shrewd traders. Marco Polo’s reception at Kublai’s court illustrates this fact. He was, indeed, only one of many foreign merchants whom Kublai appointed as tax collectors and to other key administrative posts in his empire.39 Under the Ming (1368–1644) reaction against the alliance between mercantile and military enterprise set in, though not at once, for some of its most spectacular results came early in the fifteenth century, when Chinese fleets explored the Indian Ocean for political-commercial purposes.

The imperial venture into the Indian Ocean built upon a naval tradition that took shape with the establishment of the southern Sung dynasty. When K’ai-feng fell to the Jürchen in 1126, a scion of the ruling house fled to the south and proved able to defend the remnant of the empire at the river barriers that still protected him from the barbarians of the north. He did so by creating a navy. Instead of relying on infantry forces stationed in fortified strongholds along a land frontier, as the northern Sung had done, after 1126 the southern Sung government came to rely on specially designed warships to guard against the Jürchen horsemen.

Initially the Sung navy was used primarily on inland waterways. New types of vessels, including armored ships driven by treadmills and paddle wheels, were invented for river and canal fighting. Cross-bowmen and pikemen provided the main offensive and defensive element, but large projectile-throwing machines of the kind that had long been used in land sieges and for the defense of fortified places were also mounted on the bigger vessels. It was, in general, an adaptation of methods of land warfare to shipboard, each ship playing the role of mobile strongpoint. Equipping such a navy, numbering hundreds of ships and manned by as many as 52,000 men,40 required an even more complex assemblage of raw materials and manufactured parts than the land army of the northern Sung had required. All the materials required for shipbuilding—timbers, rope, sails, fittings—were added to the relatively complex requirements land forces had already imposed on the Chinese economy. An urban base and a market-articulated supply system were even more essential than before; but the passive defense policy pursued by the northern Sung was modified by the fact that the new warships were quite mobile and could be concentrated against an attacker far more readily than infantry forces could ever be.

When, in due course, the armies of Genghis Khan overran the Jürchen domains in north China and then, after a pause of half a century, attacked the south as well, they had first to overcome the navy that had long been the principal bulwark of the Sung regime. This required Kublai Khan to build a navy of his own. With its help he besieged Hsiang-yang, one of the main Sung strongholds on the Yangtse River, for five years before being able to break through. Thereafter, most of the Sung navy went over to the victors, making the final stages of the conquest comparatively easy.41

After his victory, Kublai continued to build up his naval strength but changed its character, since the subsequent naval enterprises he undertook were ventures overseas. Accordingly, ships designed to navigate the open oceans became the backbone of the Chinese fleet.42 Yet despite a truly imperial scale of construction—it is recorded that a total of 4,400 ships attempted the invasion of Japan in 1281—Kublai’s naval expeditions met with no enduring success. Japanese warriors, in combination with an opportune typhoon, destroyed the invading force of 1281; and a later venture against Java (1292), though it met with initial victories, also failed to establish enduring control over that distant island.

What might have been more significant for the long run (but turned out not to be) was the use of seagoing ships to supplement grain deliveries from south to north along the inland waterways. By the early part of the fourteenth century, as much grain was carried in seagoing vessels as moved on the canals. Improvement of navigation techniques shortened the trip from the Yangtse mouth to Tientsin to ten days—far faster than cargo could travel through the Grand Canal. But local rebellion and disorders in the south soon began to interfere with massive long-distance shipment of grain and other commodities, and piracy at sea became a problem as well. Hence even before the final collapse of the Mongol rule in China (1368), shipments by sea had diminished to trivial proportions. Indeed, the entire tax system that concentrated extra grain in the north for use of the government broke down. Local warlords arose, one of whom succeeded in ousting his rivals and reuniting all of China under a new native dynasty, the Ming (1368–1644).

To begin with, the new dynasty combined the military policy of the southern Sung with that of the northern Sung. That is to say, the first Ming emperors set out to maintain a vast infantry army to guard the frontier against the nomads as well as a formidable navy to police internal waterways and the high seas. In 1420, the Ming navy comprised no fewer than 3,800 ships, of which 1,350 were combat vessels, including 400 especially large floating fortresses, and 250 “treasure” ships designed for long-distance cruising.43

The famous admiral Cheng Ho commanded the “treasure” ships in his cruises to the Indian Ocean (1405–33). His largest vessels probably displaced about 1,500 tons compared to the 300 tons of Vasco da Gama’s flagship that reached the Indian Ocean from Portugal at the end of that same century. Everything about these expeditions eclipsed the scale of later Portuguese endeavors. More ships, more guns, more manpower, more cargo capacity, were combined with seamanship and seaworthiness equivalent to anything Europeans of Columbus’ and Magellan’s day had at their command. Everywhere he went—from Borneo and Malaysia to Ceylon and beyond to the shores of the Red Sea and the coast of Africa—Cheng Ho asserted Chinese suzereignty and sealed the relationship with tribute/trade exchanges. In the rare cases when his powerful armada met resistance, he used force, seizing a recalcitrant ruler from Ceylon, for example, in 1411, and carrying him back for disciplining at the Chinese imperial court.44

Supplementing such official exchanges, privately managed overseas trade burgeoned in China from about the thirteenth century. Merchants and capitalists built and operated large ships. Standard patterns for management of crew and cargo, for sharing risks and gains, and for settling disputes arising from transactions at a distance came to be well defined.45 Lands close to China’s coast—Manchuria, Korea, Japan—were common destinations; but Chinese shipping had begun to enter the Indian Ocean several decades before Cheng Ho’s imperial squadrons first went there. The scale of Chinese trade in south Asia and east Africa seems to have spurted upwards from the middle of the twelfth century. The best index of this is offered by sherds of Chinese porcelain found along the African coast. They can be dated quite accurately, and show that trade started as early as the eighth century (presumably carried in Moslem ships); but quantities increased sharply after 1050, when Chinese vessels regularly began to enter the Indian Ocean by rounding the Malay peninsula instead of sending goods across the Kra Isthmus by land portage, which had been the usual practice in earlier centuries.46

Just as the rapid growth of coke-fueled blast furnaces in the eleventh century leads someone attuned to European history to suppose that an industrial revolution of general significance ought to have followed, so the overseas empire China had created by the early fifteenth century impels a westerner to think of what might have been if the Chinese had chosen to push their explorations still further. A Chinese Columbus might well have discovered the west coast of America half a century before the real Columbus blundered into Hispaniola in his vain search for Cathay. Assuredly, Chinese ships were seaworthy enough to sail across the Pacific and back. Indeed, if the like of Cheng Ho’s expeditions had been renewed, Chinese navigators might well have rounded Africa and discovered Europe before Prince Henry the Navigator died (1460).

But the officials of the imperial court chose otherwise. After 1433 they launched no more expeditions to the Indian Ocean, and in 1436 issued a decree forbidding the construction of new seagoing ships. Naval personnel were ordered to man the boats that plied the inland waters of the Grand Canal, and the seagoing warships were allowed to rot away without being replaced. Shipbuilding skills soon decayed, and by the mid-sixteenth century the Chinese navy was unable to fend off the pirates who became a growing nuisance along the China coast.47

This withdrawal was partly a result of bureaucratic infighting among rival cliques of courtiers. Cheng Ho was a Moslem by birth, probably of Mongol descent.48 This gave a foreign flavor to his overseas adventures; and Chinese Confucian officials grew to distrust things foreign. He was also a eunuch, and eunuchs, too, came under attack in the Ming court when one of them recklessly led an expedition against the Mongols in 1449 and succeeded only in allowing the barbarians to capture the emperor in person.49 But this episode pointed to a more fundamental reason for official abandonment of overseas ventures. A formidable and feared enemy existed across the land frontier, whereas, until the rise of “Japanese” piracy in the late fifteenth century, there was no rival on the seas whom the Chinese had to fear.

The issue, accordingly, became a choice between an offensive as against a defensive military policy. In 1407 the Ming navy led an expedition to Annam (modern Vietnam), but between 1420 and 1428 Chinese forces there met a series of reverses. A decision to withdraw was finally made in 1428. Against this background the memorial to the emperor, written in 1426 when the struggle in Annam was at a critical stage, sounds strangely familiar to American ears:

Arms are the instruments of evil which the sage does not use unless he must. The noble rulers and wise ministers of old did not dissipate the strength of the people by deeds of arms. This was a far-sighted policy. . . . Your minister hopes that your majesty . . . would not indulge in military pursuits nor glorify the sending of expeditions to distant countries. Abandon the barren lands abroad and give the people of China a respite so that they could devote themselves to husbandry and the schools. Thus there would be no wars and suffering on the frontier and no murmuring in the villages, the commanders would not seek fame and the soldiers would not sacrifice their lives abroad, the people from afar would voluntarily submit and distant lands would come into our fold, and our dynasty would last for 10,000 generations.50

Given the choice between defense of a threatened frontier close to the new capital at Peking and costly offensive operations overseas, it is not hard to understand why the Ming authorities opted for retrenchment.

A further consideration which may have played a part was this: in 1417, construction of deep-water locks was completed throughout the length of the Grand Canal connecting the Yangtse with the Yellow River valleys. Such locks were newly invented, and their construction meant that vessels could use the canal twelve months in the year without having to worry about high and low water. Always before, for about six months of the year, the canal had been unavailable to large boats, and sometimes traffic halted completely until the rains raised the water level. Building new locks assured year-round grain deliveries to the north via inland water routes. Reliance on ocean shipping to supplement traffic in the Grand Canal became unnecessary, and there was no longer any need to police the high seas to assure sufficient food for the capital. Officials, therefore, saw no compelling reason to authorize the heavy expenditures needed to keep the navy in a state of readiness. Accordingly they let it quietly disintegrate.

What about private entrepreneurs’ interest in ocean voyaging? Clearly, the livelihood of several thousand persons depended on the overseas trading that had flourished so markedly in the coastal cities of south China. These traders and sailors did not tamely submit when the government prohibited foreign trade in 1371, with periodic reaffirmations across the ensuing two centuries.51 Overseas voyages continued, though on a reduced scale, since the costs of doing business outside the law were significantly higher than before. Bribing officials to overlook illegal transactions usually cost more than the 10–20 percent levies in kind assessed on foreign goods under the Sung in the time when Chinese overseas trade had swelled so rapidly.52 The possibility of accumulating large private capital from the profits of seafaring became correspondingly slim, inasmuch as any official had ample reason to confiscate a merchant’s illegally gotten gains whenever they came to his attention.

For about two centuries, from 1371 to 1567, when the Ming government again authorized Chinese ships to sail to foreign lands under suitable regulation and with official permission, Chinese seamen and merchants had therefore to go outside the law to continue their way of life. Enough of them did so to constitute a nuisance to the Ming government. The officials called them “Japanese” pirates, thereby excusing themselves for not being able or willing to suppress them effectively. A few Japanese did join the pirates’ ranks, but most of the seamen operating illegally off the Chinese coast in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were ethnic Chinese. Like Wang Ko the ironmaster and his work force, these Chinese pirate-traders lacked enough popular support ever to challenge the organized might of the Ming government seriously. After 1567, when a more or less satisfactory modus vivendi between officialdom and overseas entrepreneurs was achieved, piracy subsided and the crisis passed. But two centuries of illegal operation obviously hindered the development of Chinese overseas trade prior to that date and made it much easier for European merchants to gain a foothold in the Far East.53

Both in iron smelting and shipping, therefore, Chinese achievements which anticipated later European technical triumphs were absorbed into the ongoing reality of Chinese life without making much difference in the long run. Chinese merchants and manufacturers themselves subscribed to the value system that limited their roles in society to comparatively modest proportions. They proved this by investing in land and in education for their sons, who thus joined the dominant landowning class and could compete for a place in the ranks of officialdom.54

As a result, the traditional ordering of Chinese society was never really challenged. The governmental command structure, balanced (sometimes perhaps precariously) atop a pullulating market economy, never lost ultimate control. Ironmasters and shipbuilders, along with everybody else in Chinese society, were never autonomous. When officials allowed it, technical advances and increase in the scale of activity could occur in dazzlingly rapid fashion. But, correspondingly, when official policy changed, reallocation of resources in accordance with changed priorities took place with the same rapidity that had allowed the upthrust of iron and steel production in the eleventh century and of shipbuilding in the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries.

The advantages of an economy sustained by complex market exchanges yet responding to politically inspired commands were well illustrated by these episodes. Chinese resources could be channeled toward the accomplishment of some public purpose—whether building a fleet, improving the Grand Canal, defending the frontier against the nomads, or building a new capital—on a grand, truly imperial scale. The vigorous market exchange system operating underneath the official command structure enhanced the flexibility of the economy. It also increased wealth and greatly expanded the resources of the country at large. But it did not displace officialdom from its controlling position. On the contrary, new wealth and improved communications enhanced the practical power Chinese officials had at their disposal. The fact that China remained united politically from Sung to modern times with only relatively brief periods of disruption between regimes is evidence of the increased power government personnel wielded. Discrepancies between the ideals of the marketplace and those of government were real enough; but as long as officials could bring overriding police power to bear whenever they were locally or privately defied, the command element in the mix remained securely dominant. Market behavior and private pursuit of wealth could only function within limits defined by the political authorities.

For this reason the autocatalytic character that European commercial and industrial expansion exhibited between the eleventh and the nineteenth centuries never got started in China. Capitalists in China were never free for long to reinvest their profits at will. Anyone who accumulated a fortune attracted official attention. Officials might seek to share privately in an individual’s good fortune by accepting bribes; they might instead adjust taxes and prices so as to allow the state to tap the new wealth; or they might prefer preemption, and simply turn the business in question into a state monopoly. In particular instances various combinations of these policies were always negotiable. But in every encounter the private entrepreneur was at a disadvantage, while officials had the whip hand. This was so, fundamentally, because most Chinese felt that any unusual accumulation of private wealth from trade or manufacture was profoundly immoral, since it could only arise when an entrepreneur systematically cheated others by buying cheap and selling dear. Official ideology and popular psychology thus coincided to reinforce the advantage officials had in any and every encounter with merely private men of wealth.

Market Mobilization beyond China’s Borders

Though the capitalist spirit was thus kept firmly under control, the rise of a massive market economy in China during the eleventh century may have sufficed to change the world balance between command and market behavior in a critically significant way. China swiftly became by far the richest, most skilled, and most populous country on earth. Moreover, the growth of the Chinese economy and society was felt beyond China’s borders; and as Chinese technical secrets spread abroad, new possibilities opened in other parts of the Old World, most conspicuously in western Europe.

Even before gunpowder, the compass, and printing began to revolutionize civilized societies beyond China’s borders, there was a preliminary phase when intensified long-distance commerce raised the significance of market relationships to new heights, preparing the way for a longer, more sustained economic take-off than any that occurred within Chinese borders.

Unfortunately, little is known about the growth of trade in the southern seas. Arab seafarers and before them Greco-Roman and Indonesian seamen had traversed the Indian Ocean and adjacent waters for many centuries before the Chinese appeared there. Sumerians in all probability had communicated with peoples of the Indus valley by sea at the very beginning of civilized history, and various Indian peoples also sailed to and fro across the tropical waters where summer and winter monsoons, blowing alternately in opposite directions for about half the year, made navigation relatively safe and easy, even for small and lightly built vessels.

What seems certain is that the scale of trade through the southern seas grew persistently and systematically from 1000 onwards, despite innumerable temporary setbacks and local disasters. Behavior attuned to the maintenance of such trade became more and more firmly embedded in everyday routines of human life. The production of spices, such as pepper, cloves, cinnamon, and the rest, which played so conspicuous a role in Europe’s medieval trade, began to dominate the lives of many thousands of people in southeast Asia and adjacent islands. All who cultivated and prepared these commodities for shipment, along with sailors, merchants and everyone connected with the collection, assortment, and transport of spices came to depend for their everyday livelihood on precarious linkages with consumers thousands of miles away. The same was true for the producers of hundreds of other commodities entering long-distance trade nets, from rarities like rhinoceros horn to items of mass production and consumption like cotton and sugar.55

Such specialization and interdependence duplicated what had happened earlier in China, with the difference that trade in the south China Sea and Indian Ocean crossed political boundaries. As a result, merchants faced greater uncertainty on the one hand and enjoyed greater freedom on the other. Malaya and other key places along the trade routes—Ceylon and southern India, together with ports on the African coast and in southern Arabia as well—were governed by rulers whose income came to depend in very large part upon dues levied on shipping. But once a ship put out to sea, local rulers lost control, whereas ship captains were free within fairly wide limits to seek out the cheapest place to come ashore and do business. If a ruler became too greedy, resentful captains could find another port of call. Under these circumstances, patterns of trade could alter rapidly in response to changes in political regimes, and new entrepôts could rise to importance very quickly.

This happened at Malacca, for example. That emporium, built in a dismal swamp, almost inaccessible by land, had no importance before the turn of the fourteenth-fifteenth centuries. It started as a piratical headquarters, where goods seized at sea could be re-sorted and dispatched to advantageous destinations. Then, in the first years of the fifteenth century it became a port of more general resort for peaceable shipping, and within a few decades dominated the trade of the region round about—becoming the principal entrepôt for the spices produced in the “Spice Islands” lying further east. Malacca rose, of course, at the expense of other, alternate ports. Safe harborage and moderate dues attracted trade; so did compulsion exercised by armed vessels policing the Malaccan straits between Sumatra and the mainland. Force therefore mattered in Malacca’s rise, along with the protection from piracy such force could bring. Naval force had to be sustained by taxation levied on goods passing through the port. A delicate balance between the two governed the scale of trade and the number of ships that showed up to pay dues.56

Though details are beyond recovery, it is reasonable to think that a process of trial and error gradually defined the acceptable limits of taxation a local ruler could exact from passing merchants and traders. If he lowered the costs of protection and harborage he could hope to attract new business; if he took too much, he would see traffic diminish sharply.57 A ruler who took too little (if there ever was one) might not be able to maintain effective armed control of his territory or of adjacent seas. One who took too much might suffer the same fate, if ships and merchants succeeded in eluding his grasp to the detriment of his income. In other words, a kind of market asserted itself among the political rulers of the shores of the Indian Ocean, setting what can be called protection rent at a level that permitted the continuance and (after 1000 or so) the systematic expansion of trade.58

This system may well have been very old. Presumably, ancient Mesopotamian kings and captains began to define protection rents in the earliest phases of organized long-distance trade. Assuredly, the Moslems, when they conquered the Middle East (634–51) brought with them from the trading cities of the Arabian peninsula a well-articulated idea of how trade should be conducted. The Koran afforded appropriate sanction,59 and Mohammed’s early career as a merchant offered a morally unimpeachable model. The impulse towards broadened market behavior that came from China’s commercialization was therefore a reinforcement rather than a novelty.

Indeed, the transformation of Chinese economy and society in Sung times may best be conceived of as an extension to China of mercantile principles that had been long familiar in the Middle East. Buddhist monks and central Asian caravan traders were the first intermediaries.60 Their linkages with nomads of the open steppe created another strategically important, trade-prone community, whose impact upon China and other civilized populations of the Old World was assured by the military effectiveness the nomad way of life conferred upon steppe dwellers.

What was new in the eleventh century, therefore, was not the principle of market articulation of human effort across long distances, but the scale on which this kind of behavior began to affect human lives. China’s belated arrival at a market articulation of its economy acted like a great bellows, fanning smoldering coals into flame. New wealth arising among a hundred million Chinese began to flow out across the seas (and significantly along caravan routes as well) and added new vigor and scope to market-related activity.61 Scores, hundreds, and perhaps thousands of vessels began to sail from port to port within the Sea of Japan and the South China Sea, the Indonesian Archipelago and the Indian Ocean. Most voyages were probably relatively short, and goods were reassorted at many different entrepôts along the way from original producer to ultimate consumer. Business organizations remained simple, often familial, partnerships. Hence an increasing flow of commodities meant a great number of persons moving to and fro on shipboard or sitting in bazaars, chaffering over prices.

As is well known, a similar upsurge of commercial activity took place in the eleventh century in the Mediterranean, where the principal carriers were Italian merchants sailing from Venice, Genoa, and other ports. They in turn brought most of peninsular Europe into a more and more closely articulated trade net in the course of the next three hundred years. It was a notable achievement, but only a small part of the larger phenomenon, which, I believe, raised market-regulated behavior to a scale and significance for civilized peoples that had never been attained before. Rulers of old-fashioned command societies simply were unable to dominate behavior as thoroughly as in earlier times. Peddlers and merchants made themselves useful to rulers and subjects alike and could now safeguard themselves against confiscatory taxation and robbery by finding refuge in one or another port of call along the caravan routes and seaways, where local rulers had learned not to overtax the trade upon which their income and power had come to depend.

Thus, after about 1100, what had previously been a smoldering fire, bursting out only sporadically into intenser flame, began to escape from official control and gradually turned into a general conflagration. Eventually, in the nineteenth century, market behavior flamed so high that it melted down the inimical command structure of the Chinese empire itself, although it took nine centuries before this catastrophe to Confucian China became possible.

In its initial stages this commercial transformation seemed of little importance to chroniclers and men of letters generally. Hence historians can only reconstruct what occurred by using scattered sources, painstakingly piecing together a general picture of what happened from merest fragments. This has been done for medieval Europe—mainly during the past thirty to forty years—but not elsewhere. As a result, historians know a good deal about how western Europeans developed trade relations among themselves and with Moslems of the eastern Mediterranean shoreline. It was precisely in the eleventh century, when China’s conversion to cash exchanges went into high gear, that European seamen and traders made the Mediterranean a miniature replica of what was probably happening simultaneously in the southern oceans.62 A systematic shift from piracy to trade occurred at almost the same time along the Atlantic face of Europe, where Vikings had previously raided Christian Europe.63 These separate sea networks were then combined into one single interacting whole after 1291, when a Genoese sea captain seized control of the straits of Gibraltar from a Moslem ruler who had previously interdicted through passage for Christian vessels.64

Thus, if one takes a synoptic view of the rise of commerce in the Old World, the multiple linkages within China between north and south that arose through improvements of inland waterways were matched, though on a somewhat smaller scale, by a similar development in the Far West some centuries later. European rivers, and the open seas connecting them, provided a network of natural waterways that needed rather less artificial improvement than was the case in China. By the later fourteenth century, wool, metal, and other raw materials from the north and west came to be exchanged for wine, salt, spices, and fine manufactures from the south; and an ever more elaborate grain trade supplemented by expanding fisheries everywhere sustained urban populations. The intra-European market, in turn, hitched up with Moslem-managed trade networks of the Middle East and North Africa, and with the commerce of the southern oceans. The same Italian cities that organized Europe’s interregional exchanges were the main trade partners with Moslem and Jewish merchants of the eastern Mediterranean. These Levantines, in turn, were connected with deeper Asia and Africa by commercial links that tied all the diverse peoples of the ecumene more and more closely together between the eleventh and the fifteenth centuries.

A more or less homogeneous organizational pattern and level of technique apparently established itself as a lubricant for trade throughout the southern seas, all the way from the south China coast to the Mediterranean. Regular use of a decimal system of numerical notation and of the abacus was one conspicuous and important accompaniment of this growth of trade. The value of such systems for facilitating calculations of all sorts is difficult to exaggerate and can be compared only to the cheapening of literacy that the invention of alphabetic writing had allowed some twenty-three hundred years earlier.

In addition to this fundamental simplification of numerical calculation, the long-distance trade of the southern seas depended on a cluster of institutional conventions. Rules for partnerships, means for adjudicating disputed contracts, and bills of exchange that allowed settlement of debts across long distances with a minimal transport of hard currency probably had an ecumenical scope. The same applies to rules for managing ships—how to divide profit among those aboard, organize responsibility, insure against loss, and the like. Moslem and Christian practices in these matters were nearly identical; what little is known of how the Chinese managed long-distance sea trade seems to match up quite exactly.65

Nor were the seas the only important medium of long-distance travel. From about the beginning of the Christian era, caravans had begun to link China with the Middle East and with India. Animal packtrains moving from oasis to oasis through the desert or semi-desert country of central Asia resembled ships moving from port to port. The conditions of successful operation were similar. Protection rent had to be adjusted by a process of trial and error until an optimal level at which local rulers and long-distance traders could support one another most efficiently was discovered.

Such arrangements were perpetually liable to disruption. Plunder and outright confiscation always tempted local power wielders, and alternate routes were less easy to find overland than when crossing open water. Nevertheless, caravan connections between China and western Asia were never broken off for very long after the first such ventures achieved success. In the course of the next ten centuries, the customs and attitudes that allowed the caravan trade to thrive filtered northward into the steppe and forest zones of Eurasia. Gradually a north-south exchange of slaves and furs for the goods of civilization supplemented the east-west flow of goods that initially sustained the caravans.

To be sure, evidence is scanty and indirect. The main register of northward penetration of trade patterns is the spread of civilized religions among the oasis and steppe peoples of Asia—Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, Manicheanism, Judaism, and, most successful of them all, Islam. Tribute missions dating back to Han times, when nomad rulers visited the Chinese capital and received “gifts” from the emperor and gave “gifts” in return, also attest to penetration of the steppe by a ritualized and heavily politicized form of trade. But for the most part we do not know very much about how nomads and traders entered into symbiotic relationships with one another.66

Yet pastoral nomads found the advantages of trade with civilized populations very compelling. Apart from the symbolic value of luxury goods and the practical usefulness of metal for tools and weapons, both of which assumed great importance in nomad society by or before the tenth century, a nomad population could greatly expand its food supply by modifying a diet prodigally rich in protein through trading off some of their animals and animal products for cereals. The upper classes of civilized societies—and especially those in China where animal husbandry was poorly developed—were willing to pay handsomely for animals and animal products because the work force under their control could not raise equivalent livestock nearly as cheaply as the nomads did.

China’s trade with the nomads achieved quite elaborate organization under the Han,67 but it is impossible to follow the ups and downs or regional patterns of ebb and flow, which must have been extreme. Probably trade relations between steppe and cultivated land tended to become more important during the first millenium of the Christian era. The prominent place merchants held in Mongol society in the time of their greatness is proof that trading and traders were securely at home among the heirs of Genghis Khan.

The Mongol conquest of China in the thirteenth century opened up new possibilities for nomad tribesmen. Under Kublai and his successor, for example, the garrison of Karakorum received more than half a million bushels of grain each year from China, delivered by wagons that took four months to make the round trip.68 Such deliveries supplemented the meat and milk products available locally to allow more people to survive on the steppe than could otherwise have done so. But dependence on grain supplies from afar also meant risk of real disaster should deliveries be cut off. As long as Mongols ruled China, grain deliveries were assured; but when the Ming dynasty came to power (1368), Chinese authorities were tempted to embargo grain export as a way of bringing pressure on their steppe neighbors. They actually did so in 1449. The Mongol response was to go to war, with the result that they captured the person of the emperor.69 Anything less would have meant starvation for at least part of the population of the steppe.

It is worth pointing out that nomads (as well as transhumant pastoralists in Mediterranean Europe) shared this kind of vulnerability with city folk. Urban populations, too, suffered catastrophe with any prolonged interruption of food supply. Cities, especially big cities, survived only on the strength of a smoothly functioning transport system capable of bringing food from afar. Nomads and transhumant pastoralists were particularly well fitted to undertake the overland transport tasks involved in feeding inland cities, since they possessed suitable pack animals in large numbers. In fact, it seems plausible to say that a social alliance between urban populations and animal husbandmen became the backbone of Islamic society. This alliance expanded from its birthplace in Arabia across most of the Middle East, as city folk were persuaded or compelled to cooperate with nomads to exploit the grain-growing majority. As for the peasantries, they were all but helpless, being rooted to the soil by their routines of life and unable to achieve the mobility (or market participation) that urban and pastoral life both came to depend upon.70

Anticipating what occurred on the seas in the eleventh century, linkages between steppe populations and civilized lands seem to have crossed a critical threshold in the tenth century. Beginning about 960, Turkish tribesmen infiltrated the central regions of the Islamic world in such numbers as to be able to seize power in Iran and Mesopotamia. Another Turkish people, the Pechenegs, flooded into the Ukraine in the 970s, cutting the Russians off from Byzantium. Simultaneously, along the northwest Chinese border a series of newly formidable states came into existence, beginning with the Kitan empire (907–1125).

These political events reflect the fact that in both China and the Middle East (though not perhaps among the Pechenegs) nomad military organization and effectiveness transcended earlier tribal limits in the tenth century. This was partly a matter of improved equipment. Metaled corselets and helmets, for example, became commonplace when trade with civilized societies gave nomads, like the Kitan, access to such goods in quantity. The Kitan also learned to use siege machines—catapults and the like—thus overcoming the earlier impotence of raiding horsemen when confronted by fortifications. But new equipment was less important than new patterns of social and military organization. In the course of the tenth century, civilized models of command and military discipline took root among steppe peoples, supplanting or at least modifying old tribal structures. The Kitan, for example, organized their army according to a decimal system, with commanders for tens, hundreds, and so on, just as the ancient Assyrians had done. The Turks who took power in Iran and Mesopotamia were even more radically detribalized, having become slave soldiers in the service of civilized rulers before seizing power in their own right.71

The enhancement of nomad military power through interpenetration with civilized societies climaxed in the thirteenth century. Genghis Khan (r. 1206–27) united almost all the steppe peoples into one single command structure. His army was also arranged on a decimal system, led at each level (10s, 100s, 1,000s) by persons who had earned the right to command by success in the field. As this formidable and expansible army (defeated steppe enemies were simply folded into the structure, starting at the bottom as common soldiers) penetrated civilized ground in north China and central Asia, the Mongol commanders took over any and every new form of weaponry they encountered. Thus they brought Chinese explosives into Hungary in the campaign of 1241, and used Moslem siege engines in China—more powerful than any the Chinese had yet seen—in the campaigns of 1268–73 against the southern Sung. Similarly, as we have already noticed, Kublai Khan first annexed and then transformed the southern Sung navy into an oceanic fleet in order to launch attacks on Japan and other lands overseas.

Yet the enormous successes that came to Mongol arms in the thirteenth century carried their own unique nemesis. As had happened before to other steppe conquerors, after two or three generations the comforts and delectations of civilization undermined the hardihood and military cohesion of Mongol garrisons. This was normal and to be expected, and led to the eviction of the Mongol soldiery from all of China in 1371. In western Asia and Russia, Mongols were not driven out but instead dissolved into the numerically superior Turkish-speaking warrior population of the western steppe after the end of the thirteenth century, when subordination to the Great Khan in Peking ceased to have even ritual significance.

But on top of this normal pattern whereby steppe conquerors were partly absorbed and partly repulsed by civilized communities, two accidental by-products of the Mongol empire of Asia radically weakened steppe peoples vis-à-vis their civilized neighbors. One was the demographic disaster to Eurasian nomads that resulted from the arrival of the plague, known in European history as the Black Death (1346). The plague bacillus probably became epidemic among burrowing rodent populations of the steppe for the first time in the fourteenth century. The infection was presumably introduced into the new environment by Mongol horsemen who brought it back from their campaigns in Yunnan and Burma, where endemic plague already existed among local populations of burrowing rodents. Once the bacillus established itself on the steppe, nomad populations found themselves systematically exposed to lethal infection of a kind that had never been known there before. Radical depopulation and even the complete abandonment of some of the best pasture land of Eurasia was the result.

By degrees, folkways effectively insulating steppe dwellers from the new infection may have arisen. This certainly occurred in the Manchurian portion of the steppe, for such practices were in force there in the 1920s, when the most recent serious outbreak of plague among human populations took place in that part of the world. But this sort of readjustment took time. For two centuries or more after 1346, steppe populations appear to have been much reduced in number by their exposure to a new and very lethal disease that Mongol expansion across hitherto insuperable distances had brought in its train.72

The resulting interruption of demographic movement out of the steppe towards cultivated lands disrupted what had long been one of the fundamental currents of human migration in the Old World. By the time the steppe peoples began demographic recovery, a new factor, also traceable back to the Mongol breakthrough of older geographic barriers, came into play: the use of firearms that could counter nomad archers on the battlefield. Effective small-arms were not generally available to civilized armies until after about 1550; but as they spread, nomad superiority in battle suffered its final erosion. Instead of being able to encroach on agricultural ground, as nomads had been able to do since about 800 B.C., peasants began to invade the cultivable portions of the Eurasian grasslands, making fields where pasture had previously prevailed. The eastward expansion of Russia and the westward expansion of China under the Manchus between 1644 and 1911 registered this reversal of human settlement patterns politically. It is ironic to think that the diffusion of gunpowder weaponry, which led to the final eclipse of steppe military power in the mid-eighteenth century, was a by-product of the Mongols’ military success, and of the radical rationality they exhibited in their management of weapons design, logistics, and command. Yet so it was.