The Arms Race and Command Economies since 1945

When World War II ended in 1945, return to prewar conditions was not a viable ideal. In many parts of the earth, old political regimes were discredited and unpopular. This was true in the defeated countries and in most European colonies, even in places where there had been little or no active fighting. Both in liberated and in occupied Europe wartime destruction and dislocations assured continuing misery long after fighting had stopped. Even among the victors, war mobilization had attained such an extreme that spontaneous return to normal, however normal might be defined, was no longer possible. Cancellation of wartime regulations was not enough; planned mobilization demanded planned demobilization and conscious redeployment of resources. Thus national and transnational management and command economies were as necessary after the war as during it. American efforts to institute a liberalized international trading system were rendered futile by these facts.

What happened in the postwar years was, in its way, as surprising as the achievements of wartime production and destruction. Methods that had summoned enormous numbers of tanks, airplanes, and other weapons into existence during the war when applied to the tasks of reconstruction lost little of their magic—at least in the first years when what to do was easy to define and agree upon. The recovery of western Europe with the help of credits from the United States, 1948–53, was spectacularly swift. The USSR and eastern Europe did not lag very far behind, thanks to a still abundant pool of manpower and natural resources hitherto but slenderly exploited for industrial purposes. Japan also began to exhibit an industrial and commercial dynamism after 1950 that eventually left even Germany and the United States behind, thanks to its unique adaptation of traditional forms of social solidarity to industrial and urban conditions of life.

With the defeat of Germany and Japan, the four transnational war economies dissolved into two rival blocs. Germany was divided into zones of occupation. Its wartime dependencies in Europe split into an eastern zone dominated by the USSR and a western zone where the United States soon took the leading role. Japan’s Co-Prosperity Sphere also split up. Mainland China went Communist in 1949; Korea and Indochina divided; most of the rest, including Japan itself, came within the American sphere of influence. The “iron curtain” in Europe provoked noisy controversy, but no actual fighting. Partitioning the Co-Prosperity Sphere, on the contrary, triggered long-drawn-out wars in China (1944–49), Korea (1950–53), and Indochina (1946–54, 1955–75), as well as lesser armed conflicts in Indonesia, Malaya, and Burma.

Many former colonial lands tried hard to protect newly won political sovereignty by resisting more than marginal association with either the Soviet or the American power blocs. In practice however, new governments needed economic help and found themselves dependent on credits from abroad, provided either by their former imperial masters or by the American or Russian aspirants to vacated imperial roles. The “Third World” of new nations and uncommitted peoples was, nonetheless, a reality in the postwar decades, modifying the simple polarity of the cold war.

Despite intense initial difficulties, the USSR reverted to autarky after 1945, casting off the reliance on Lend Lease supplies from the United States that had developed in the last stages of the war. To be sure, reparations in kind from conquered Germany and trade deals with east European countries that were markedly advantageous to the USSR helped the Russians to survive the first desperate months when war damages were only beginning to be repaired. Frictions first with Britain, then with the United States, kept alive a sense of beleaguer-ment among the Communist elites. Stalin declared and probably believed that there was only a “temporary political” difference between Nazi Germany and other capitalist states.1 Stalin’s Marxism thus took it for granted that the imperatives compelling Hitler to attack the Motherland of Socialism in 1941 were just as ineluctably at work within British and American society in the postwar years. Consequently Soviet reconstruction had to compete from the beginning with continuing military expenditures. In particular, Russia’s efforts to develop atomic bombs like those the Americans had used against Japan in 1945 must have had the highest priority at a time when civilian levels of consumption within the USSR were still at a very low ebb indeed. Stalin also maintained such large forces in eastern Europe that American and other observers believed the Red Army was able and might be tempted to overrun the entire European continent.

Between 1946 and 1949 American countermoves consolidated a rival transnational economic and military power structure, somewhat disingenuously dubbed the “Free World.” In many senses it was freer than the lands dominated by the USSR. Public expression of dissent was not systematically repressed; and labor, food, fuel, and raw materials were not allocated by governmental fiat on anything like the scale that prevailed within Communist-ruled lands. Individual choices about work, consumption, and leisure activities remained correspondingly broader than anything available within the Communist camp. Yet individual and small group choices operated in a society dominated by a new symbiosis of public and private administrators. Managed economies became normal in all industrially advanced countries; and as long as public consensus about the general goals of such management could be maintained, no one objected very vigorously. In other words, among the great majority of Americans, west Europeans, and Japanese, freedom collapsed into obedience and conformity to bureaucratically channeled behavior. The springs of obedience and conformity within the Communist lands were similar inasmuch as most Russians and east Europeans, together with the enormous Chinese population, also willingly accepted goals defined by their bureaucratic superiors and behaved accordingly. Their rewards were smaller than in the West and Japan, where living standards rose rapidly and soon surpassed prewar levels. But standards of consumption rose in Communist lands too, so the difference was only one of degree.

Diminished allocation of resources through direct governmental action and the enhanced scope for fluctuating prices as regulators of economic behavior presumably improved the general efficiency of Free World as compared to Communist society. American corporate managers, though able to allocate resources by simple command within their corporations, were constantly brought up against the necessity of buying and selling goods and services to others who were not directly under their control. Insofar as their partners in such transactions were large corporations and governments, oligopolistic and monopolistic market confrontations ensued. In these instances, prices were set by diplomatic negotiation rather than by competition from some mythical “outside.” But in transactions with private citizens and other weakly organized market partners, corporate and governmental buyers and sellers were usually able to set prices at levels favorable to themselves. They did so simply by regulating supply to keep the price of whatever they offered for sale at the level they preferred.

As long as large-scale buyers and sellers could operate in a setting of weakly organized trading partners, a remarkable exactitude of large-scale management became possible. Financial planning and material planning matched up. Prosperity set in as war damages were repaired. New investment proliferated and full employment, or close to it, became a reality. The dysfunction of the prewar depression years vanished thanks to a happy collaboration between skilled large-scale corporate management on the one hand and governmental fiscal policy on the other, enlightened by the new science of macroeconomics and backed by enlarged expenditures for arms and welfare. A veritable managerial revolution in the leading capitalist countries seemed to have made industrial nations masters of their collective destinies as never before. Moreover, since the principal governments concerned remained elective, the interests and needs of ordinary folk at home were safeguarded by a democratic franchise.

On the other hand, when operating in poorly organized foreign countries, large American and European corporations escaped many of the political constraints familiar to them at home. Agricultural producers, together with lands supplying minerals and other raw materials, were seldom capable of organizing themselves in such a way as to meet foreign corporations on anything like even terms. When in 1973 governments of oil exporting countries succeeded in doing so, the Free World’s postwar pattern of command and corporate economy faced its first severe shock in more than two decades.2

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the United States took the lead in renewing a transnational military command to safeguard the sphere of influence that fell to the Americans with the decay of British power. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization, established in 1949, entrusted the task of marshaling west European defenses against the Red Army to an American commander in chief. At first, Russian soldiers stationed in east European lands seemed a better guardian of Soviet interests than locally recruited forces. But when West Germany joined NATO in 1955 the Russians responded by establishing a military alliance and command system—the so-called Warsaw Pact—that was a mirror image of NATO. Elsewhere, in southeast Asia and the Middle East, American efforts to set up comparable regional defense organizations met no significant success. Only in Europe did the two super powers confront one another across a well-defined boundary, on either side of which carefully matched polyethnic garrisons developed war plans, carried out training exercises, and indulged in various kinds of war gaming of a sort which in prewar years had existed only within national frontiers. The World War II experience of transnational organizations for war was thus institutionalized in time of peace. National sovereignty, as once conceived, disappeared, more through fear than from any positive conviction of the merits of newfangled transnational military organization.

Economic and psychological factors played their part in eroding national sovereignty in Europe; but an even more important factor was the drastic new threat that nuclear weaponry presented. NATO came into being, initially, in response to the presence of large Red Army forces in eastern Europe. Their mere numbers seemed capable of overrunning the entire continent at will, unless American military force, backed by the ultimate atomic sanction, were permanently committed to defending the European bridgehead projecting so precariously from Russia’s vast Eurasian sphere of management and control.

The Russians, on the other hand, were quite unwilling to remain indefinitely at the mercy of American bombers. Stalin spared no effort to achieve atomic capability. In 1949, five months after NATO was established, the USSR exploded its first nuclear device. This provoked surprise and dismay in the United States, for nearly all Americans had been sure that the Russians would not be able to master the complexities of atomic technology for many years. Russian prowess in science, engineering, and weapons design was further demonstrated by the next round of the postwar arms race. For in 1950 the American government reacted to the loss of its atomic monopoly by deciding, reluctantly, to press ahead with the development of a far more terrible weapon, the fusion or H-bomb. The Russians kept pace, exploding their first hydrogen bomb only nine months after the United States in November 1952 had used Eniwetok atoll in the Pacific for its first experimental test of the fusion reaction.

Even though complex in construction, hydrogen warheads could readily be made far lighter than the first clumsy uranium and plutonium bombs. This made rockets an obvious and preferred instrument for their delivery. No means of intercepting a speeding rocket existed, and Germany’s bombardment of England by V-2s in 1944 had shown how effective such weapons could be. The Americans accordingly put new urgency into rocket research and development, beginning in the early 1950s; but the Russians started a good deal sooner than the United States at a time when heavier atomic warheads required larger and more powerful rockets to get off the ground.3 As a result, in October 1957 the Russians launched a rocket powerful enough to put a small satellite—Sputnik—into orbit around the earth, and in ensuing months sent larger and larger payloads after it into space.4

The Russian achievement left no doubt of their technical capacity to drop atomic warheads anywhere on the face of the earth. American rockets lagged behind in size and power until 1965. This did not mean that American ability to deliver atomic warheads really fell short of Russian capabilities, for United States bombers, stationed within easy striking distance of the Soviet Union, together with newer submarine-based missiles, capable of being launched from beneath the seas, kept Russian cities under the same threat of annihilation that hung over the people of the United States after 1958.

Americans were not comforted by knowing that their new vulnerability merely brought them to the level of their rivals. For generations before Sputnik, the territory of the United States had been immune to any real danger of foreign attack. As a result, the shock of discovering that this was no longer the case and that Russians had outdistanced America’s own vaunted technical skill in at least one important field proved unusually intense.5 Not surprisingly, the so-called “missile gap” became a point of controversy in the presidential election of 1960. The new Democratic administration that took office in 1961 was committed to surpassing the Soviets in rocket technology, whether on the moon or on the earth.

The Russians, on the other hand, tried to exploit their technical lead by asserting full equality with the United States the world around. However, in October 1962 Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s scheme for installing intermediate-range missiles in Cuba, where they would have been capable of attacking most American cities, failed when the United States Navy prevented delivery of some of the necessary equipment. After a tense confrontation, the Soviets backed down and agreed to withdraw their missiles from Cuba. But this humiliation triggered a vast expansion of the Soviet fleet in the following years, aimed, clearly, at equaling or surpassing American power on and especially underneath the sea.6

Arms competition between the USA and the USSR therefore attained a new and enlarged scale in the 1960s. Emphasis was on new technologies and new weapons. Research and development mattered more than current capabilities. A breakthrough in the future, whether defensively or offensively, might alter or even upset the balance of terror that arose in the decade after 1957 as the two countries installed hundreds of long-range missiles and so became capable of destroying each other’s cities in a matter of minutes.

The United States government responded to the new sense of danger by pouring money into research and development with a prodigal hand. Not all was military, for the men directing national policy—especially those deriving from Harvard University and MIT—believed that the ultimate test of American society in its competition with the Soviets boiled down to finding out which contestant could develop superior skills in every field of human endeavor. Entering upon such a competition, a wise and resolute government could expect to commission task forces, composed of suitably trained and supremely ingenious technicians, to develop an unending succession of new devices for peace and war. This would guarantee prosperity at home and security abroad. But success would come only if skill were cultivated wherever it could be found, and if it were encouraged by the removal of long-standing fiscal limitations on education, research, and development.

The ensuing academic boom, led by natural science, was matched only by the boom in aerospace and electronics. In effect the managerial elites that had come so powerfully to the fore during World War II now found a new, more technocratic outlet for their ambitions and skills. For their cold war had to be fought on a wide front. Social engineering to achieve a better society mattered as much as the improvement of military hardware.

The prevailing confidence in the nation’s ability to solve all problems and overcome all obstacles took dramatic form in 1961 when President John F. Kennedy announced that the United States would put a man on the moon within the decade. The task was entrusted to a civilian agency, NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). But new technologies allowing men and machines to move about in space always had military implications and applications. This made the separation of military from civilian research and development of space technology almost meaningless.7

The Soviet Union strained to keep up, announcing a new party program in 1961 that promised to overtake the United States level of per capita production within the decade so as to be able to inaugurate communism (from each according to his ability, to each according to his need) in the 1980s. Premier Khrushchev’s technocratic faith was, indeed, very similar to that which inspired President Kennedy’s circle of policy makers. Both drew upon their memories of what had been done during and immediately after World War II to achieve impossible production goals by resort to deliberate social and technical engineering.

Most other countries despaired of the race. France, however, rebelling against what General Charles de Gaulle felt to be undue American partiality for Britain and Germany, withdrew from NATO and embarked on a national program of research and development à l’Américaine. Only so, de Gaulle felt, could France escape from becoming a quasi-colonial dependency of American (or, alternatively, of Russian) technocracy.8 In the Far East, China and Japan both made belated efforts to enter the technological space race, but only the USSR had the means and motivation to match the American effort step by step. The following tally of launches into space, 1957–72, provides an indication of the domination achieved by the two super powers in space technology during the first fifteen years: USSR, 612; USA, 537; France, 6; Japan, 4; China, 2; and Great Britain, 1.9

The USSR invested heavily in a new navy during the 1960s as well as in rocketry and space vehicles. In all probability, military research and development in the Soviet Union more or less matched the sums allocated to the same purpose in the United States. But comparisons are very inexact, because of budgetary obfuscation on both sides as well as the arbitrary values each country assigned to recondite new devices. When there was only one manufacturer and only one buyer for some new kind of technology, as was universally the case in the space race, what costs and overheads to count in or exclude from the pricing of a given piece of machinery became a more or less metaphysical exercise in accountancy. There was no doubt, however, that expenditures on both sides dwarfed peak World War II outlays on technological innovation.10

Vast expenditure brought extraordinary results. Undoubtedly the greatest spectacle was the landing on the moon by American astronauts in 1969. Probes of other planets sent back data of great interest to astronomers, and scanning satellites harvested enormous amounts of new information about the surface of the earth itself. In the weapons field, science fiction and technological fact interpenetrated one another in a fashion outsiders can only dimly understand. Control devices to alter missile trajectories in flight attained great sophistication in the 1970s for example. This complicated the task of interception enormously. Indeed, no reliable way of attacking approaching missiles could be found. For at least a quarter of a century after the missile race went into high gear, lasers and other “death rays” capable of destroying enemy warheads with the speed of light remained fictional. The balance of terror therefore continued more or less intact, despite all the efforts Americans and Russians put into finding a way to shield themselves from the specter of sudden annihilation.

In one respect, the balance of terror became more stable. The development of spy satellites from 1960 onwards gave each side sure and complete access to information about the other’s missile installations on land. This greatly advantaged the Americans, who found it far harder to keep secrets than the Russians did. Presumably, mutual acceptance of satellite surveillance from outer space arose as an accidental by-product of the fact that when Russia launched the first satellite, its path, inevitably, transgressed national frontiers. The Soviet government was therefore unable to object when the United States followed suit. The further fact that neither power was able to shoot down enemy satellites when first they began to traverse space above their respective home territories made it necessary to acquiesce in what could not be prevented. Soon afterwards, the United States developed satellites carrying high-resolution cameras that could relay fine details of the Russian landscape back to earth. The Russians did object to this, but only half-heartedly.

Satellite surveillance at once dispelled many uncertainties about Soviet missiles. Indeed, in 1960 when the “spies in the skies” first started to work their magic, American officials discovered that the missile gap was mythical. The Soviets had not in fact yet invested in expensive rocket arrays poised to attack American cities, even though their technical capacity to do so had been proved. Each side subsequently did install hundreds of missiles at carefully prepared launch sites. But throughout the process, satellite surveillance detected every new installation. Each government could feel confident of the facts so miraculously made manifest since, even if perfect camouflage were possible for a completed launch site, during construction telltale signs were sure to show.

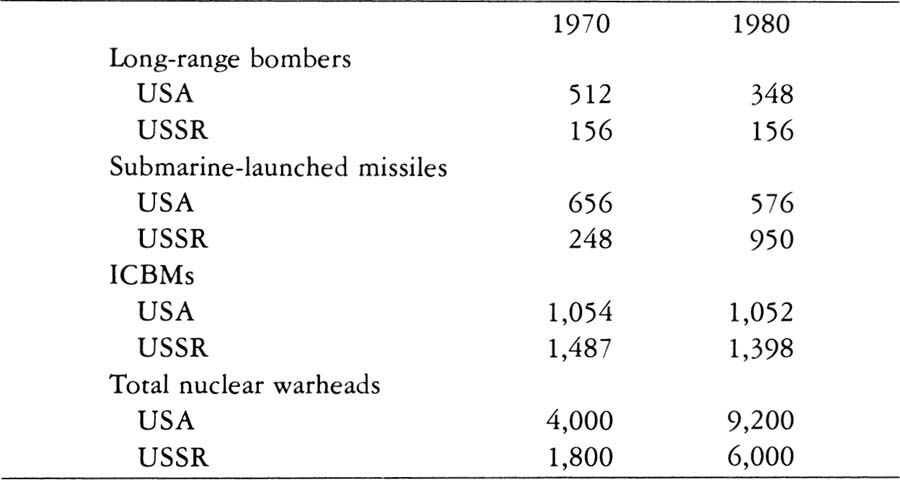

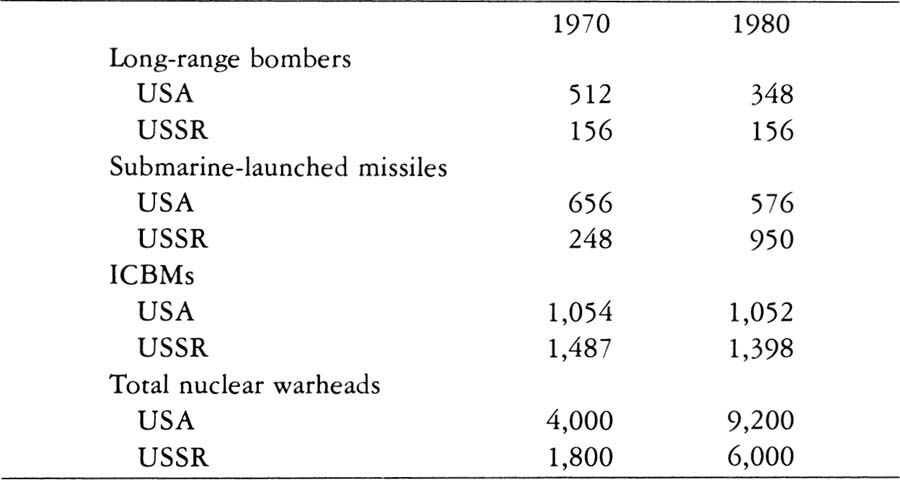

During the 1960s, therefore, each watched while the other installed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) to match those they were themselves emplacing. Simultaneously, each power built and deployed submarines capable of lying silent beneath the sea for weeks at a time before launching atomic warheads from below the surface.11 This buildup produced a balance of nuclear forces approximately as shown in table 2.

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Yearbook 1981, table 2:1, p. 21.

Clearly, by the beginning of the 1970s, substantial equality had been achieved in the sense that each power was in a position to wreak such damage on the other that building additional missiles seemed wasteful. A five-year Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT), signed in 1972, accordingly set a ceiling on such weaponry. This did not, however, halt the arms race. Research and development teams merely shifted attention to other kinds of weapons not mentioned in the treaty for the good reason that they did not yet exist. By the end of the 1970s therefore, several new weapons systems were ready to make the transition from experimental laboratories to production lines. But which weapons to build and how much of the nation’s resources to commit to the escalation of the arms race remained, in 1981, a disputed matter in the United States. No doubt similar disputes were in progress within the Soviet Union, even though public airing of alternatives, such as was necessary in the United States to persuade Congress to vote funds, did not take place.

New models of old weapons with improved performance capabilities were disturbing enough to the world’s power balances. The further possibility that some device of a quite different kind might suddenly open a new avenue for paralyzing violence also prevented the world’s great powers from settling down to any stable, trusting accommodation with one another. Breakthroughs in chemical or biological warfare might at any time create an end run around the atomic balance of terror. But what seemed particularly promising for the 1980s were various kinds of “death rays” traveling with the speed of light. Such beams, launched from space vehicles, might be expected to intercept incoming missiles, or perhaps even destroy them in their launch sites. The merest glimmer of such a possibility introduced a profound instability in the balance of terror that had prevailed since the 1960s.

Clearly, competition for strategic advantage by dint of some new breakthrough in the design of a secret weapon was impossible to exorcise in a world where rival states feared one another. Mounting costs, as successive generations of weapons became more and more elaborate, constituted a brake of sorts. But interested parties, seeking new contracts in the USA or assignment of new resources of manpower and materiel in the USSR, could always point with alarm to research and development efforts undertaken by the other side. Political managers had somehow to balance demands from the civilian economy against the ravenous appetite for new resources that military research and development teams regularly exhibited. Decisions for and against particular weapons systems and development programs in the United States often induced a mirror image response in the USSR. But much remained secret, especially in Russia. The fiscal and moral uncertainties as well as the technological and engineering uncertainties that had manifested themselves so fatefully before World War I in connection with the Anglo-German naval race12 haunted policy makers in both countries. The difference was that the cost of error had multiplied many times over in the intervening decades.

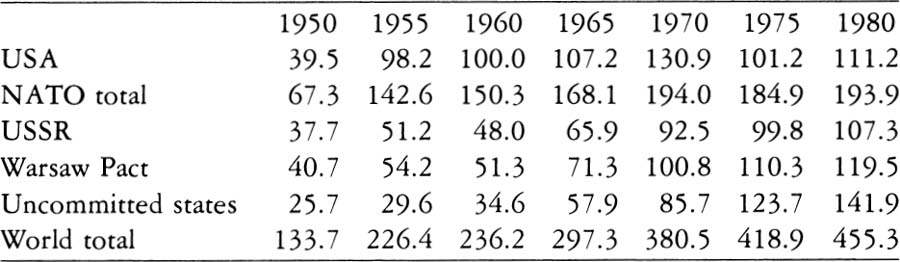

Space spectaculars tended, perhaps, to disguise the fact that the arms race was not limited to the USA and USSR, nor were the two superpowers solely concerned with rockets and atomic warheads. Table 3 summarizes the extraordinary growth of military expenditure that took place in the post-World War II decades. These figures are liable to enormous errors because of budgetary subterfuges and the arbitrary exchange rates that must be assigned in reducing money costs to a common dollar denominator. Nevertheless, whatever distortions survive these more or less neutral Swedish efforts to get at the truth, it remains indubitable that superpower military spending had its counterpart among other governments. Indeed, the rate of increase in military spending by Third World countries in the 1970s exceeded the growth rate of great power expenditures.

Table 3. Military Expenditures at Constant Prices (In billions, 1978 dollars)

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Yearbook 1981, Appendix 6A, p. 156.

The arms race thus proved contagious, affecting all parts of the earth. An especial peak (or depth?) may be discerned in the Middle East, where oil revenues and unstable regimes overlapped the Arab-Israeli and other apparently irreconcilable local conflicts. As a recipe for disaster, developments since 1947 in the Middle East were hard to equal, though bloodshed in southeast Asia was greater, while race and tribal wars in Africa were restrained more by poverty and a resulting shortage of highly lethal weapons than by any sort of prudence.

The two superpowers were in a poor position to control the situation. In the 1960s, if not before, the American and Russian governments realized that even after a successful surprise atomic attack, awesome retaliation would follow. Their new power to destroy therefore ceased to be a practicable instrument of policy. Other governments soon saw the same thing and felt freer than before to defy the USA and the USSR. The French withdrawal from NATO in 1966 and a growing restiveness in eastern Europe registered this fact. As the capacity for mutual destruction became more and more assured, the two superpowers were in danger of becoming a pair of Goliaths, hampered by the very formidability of their weaponry. Paradoxically helpless, they were as unable to use atomic warheads as to do without them.

Such a situation, transmuting unimaginable power into its opposite at the wave of a wand, was without historical precedent. Yet it occurred in a world where nuclear proliferation remained both a possibility and a reality, although exactly how many governments possessed atomic warheads or the means to deliver them remained secret. Only six states have exploded warheads in public,13 but several others have been widely suspected of possessing warheads manufactured from plutonium produced in nuclear power plants.14

In the postwar decades, neither the nuclear umbrella nor the efforts of international peace-keeping bodies sufficed to prevent local wars and guerrilla actions from breaking out and running their course repeatedly. Armed conflicts numbered in the hundreds; and the combatants, dependent on outside sources of arms in nearly every case, almost invariably sought help from one or the other of the superpowers, directly or indirectly.15 Staying aloof from such affairs was difficult. Substantial numbers of American troops engaged in the Korean War, 1950–53, for example, and even larger numbers later fought vainly in Vietnam, 1964–73. The Russians, for their part, invaded unruly eastern European countries in 1956 and again in 1968, and tried the same thing in Afghanistan in 1979. The United States met qualified success in Korea and humiliating defeat in Vietnam. It remains to be seen whether the Russians’ qualified successes in Hungary and Czechoslovakia will be followed by a different result in Afghanistan.

The quite extraordinary power of a technically proficient society to exert overwhelming force on its enemies depends, after all, on prior agreement about the ends to which collective skill and effort ought to be directed. Maintaining such agreement is not automatic or assured. This became clear in the United States during the Vietnam War, when the cause for which Americans were fighting became so dubious as to make withdrawal politically necessary. American technological superiority did not defeat the Viet Cong. Acts of destruction merely hardened Vietnamese opinion against the foreigners. Escalation offered no solution, short of all-out attack on the north, or a level of destruction in the south that would have destroyed most of the human beings whose liberties the United States claimed to defend.

Moreover, as Vietnamese feeling solidified against the invaders, American opinion at home divided more and more sharply as to the justice and wisdom of armed intervention in Vietnam. Distrust of the military, of high technology, and of the administrative-academic-military-industrial elites that had guided the American response to Sputnik became widespread. The high hopes and brash self-confidence with which the American government had launched its adventure into space in the 1960s evaporated, leaving a sour taste behind. Large numbers of young people espoused some form of counterculture, deliberately repudiating the patterns of social management that had attained such heights during and after World War II.

In extreme forms, their rebellion was suicidal, as many drug-takers’ shortened lives showed. It was also ineffective in inventing viable alternatives to bureaucratic, corporate management. Cheap, mass-produced goods required flow-through technology which only large-scale bureaucratically managed corporations could sustain; and a world safe for such behemoths must presumably regulate their interactions bureaucratically as well. Spontaneity, personal independence, and small group solidarity against outsiders have very limited scope in such a society. But the material impoverishment that thoroughgoing return to any of these older values and patterns of behavior entailed was a far higher price than most of the rebels were prepared to pay.

Nevertheless, flow-through technologies remained extremely vulnerable to disruption. The factory efficiency that cheapened costs of production required precise coordination of many subsidiary flows. Interruptions anywhere along the line turned efficiency into its opposite very quickly. Discontented and disaffected groups, if appropriately organized, could therefore obstruct the industrial process easily enough, as successful strikes since the 1880s had demonstrated more than once.

On the other hand, the price of survival for even the most incandescently revolutionary group was the generation of its own power-wielding internal bureaucracy. And bureaucratically organized revolutionaries, if genuinely powerful, found themselves swiftly coopted into the labyrinthine tasks of state management. The public life of Germany and Great Britain since World War I exhibited these compulsions quite clearly; but the Soviet Union carried the bureaucratic transmutation of protest into governance to a kind of logical completion, making a once revolutionary party and radically disruptive unions into undisguised instruments of state control over the industrial working force and society at large.

The hard fact remained that only by organizing bureaucratically could groups assert themselves effectively in a bureaucratic world. This deprived the counterculture of the 1960s of enduring importance. Yet American technocrats and politicians were compelled to recognize hitherto unsuspected limits to their new powers of social management. The great administrative machines created by and constituting the skeleton of the national state could not decide at will what ends to pursue, nor who should manage whom. Reason and calculation came a poor second in settling such questions to ideals and feelings. Manipulative propaganda could only establish the emotional climate for mass obedience by staying within limits set by inherited, widely prevalent beliefs. Fissiparousness, inherent in a highly skilled and sharply differentiated society, put enormous strains on political leadership. These strains were not significantly relieved by the fact that politicians and statesmen could call on the most expert systems analysis, cost-benefit calculations, and other instruments of modern industrial, corporate management.16

Perhaps the most fundamental shift of the postwar decades was a widespread withdrawal of loyalty from constituted public authorities. Ethnic, regional, and religious groupings gained importance at the expense of the national state while at the same time various transnational collective identities and administrative structures also waxed stronger than ever before. Within what units and to what ends the technical virtuosity of modern management would be exercised was a question that therefore attained a new vibrancy in the 1960s and 1970s. This was especially apparent in the more advanced industrialized countries, where old-fashioned patriotism seemed clearly on the wane. How it will be answered in years to come may well turn out to be the capital question of humanity’s future.

Soviet society was not immune. Khrushchev’s confident promises of the early 1960s soured when it became apparent that enhanced productivity, upon which everything depended, was not forthcoming merely on the strength of exhortation from the Communist party to work harder in order to enjoy a better life sometime in the future. Khrushchev’s notorious secret denunciation of Stalin in 1956 unleashed previously pent-up criticism among members of the managerial elites. Methods of Soviet planning came under scrutiny, for example, and debates as to how to assure a more efficient use of resources attained quite unaccustomed candor. Experiments in administrative reform were tried in the mid-1960s; but when the debates became too revelatory of internal difficulties and differences of opinion, public discussion was shut down again.17 Thereafter, as previously in Soviet (as also in prerevolutionary Russian) history, police pressure inhibited free expression of dissent.

Yet the personal courage needed to defy official repression gave unusual weight to the voices of those who continued to dare. Throughout the postwar era, dissidence within the Communist world proliferated, beginning as early as 1946, when Yugoslavia split away from the rest of the Communist world. Other nations subsequently did the same, most notably the Chinese in 1961. Such splits reflected national feeling and diversity. So did some expressions of dissent from within the Soviet Union, especially among Jews and Moslems. But in addition, a few distinguished scientists and men of letters attacked repression of truth and personal freedom within the USSR. Such individuals were able to circulate their views through secret channels, within and also outside of the Soviet Union.

This proved, if proof were needed, that the few individuals who dared to defy party authorities were supported by many others who sympathized with the dissidents sufficiently to pass their writings from hand to hand and through secret channels to persons living beyond the reach of the Soviet police. A second sign of disillusionment with official ideology was the vogue for pop music and other imports from the youth culture of the West. A real if tenuous counterculture thus emerged in the Soviet Union which offended the pieties and proprieties of the Russian establishment even more radically than the parallel youthful rebelliousness grated upon capitalist-corporate values in the United States.

Strains on consensus within state boundaries, however, merely tended to make the police and armed forces more important. Except for France and Britain, none of the major industrialized countries had to call on its armed forces to put down domestic disorder during the postwar decades. In poorer countries, however, intenser dissension brought the military to the fore, time and again. In any modern state, weaponry in the hands of police and soldiers exercises an ultimate veto on internal political processes, unless the discipline and cohesion of the armed forces breaks down. Preservation of discipline in difficult times calls for isolation and withdrawal from civil society, particularly when that society becomes permeated with serious dissent. Maintenance of suitable skills, on the other hand, calls for interpenetration with some at least of the technically proficient elites of civil society. Yet such elites are especially likely to become impatient with an inefficient or corrupt government, believing that they can do better themselves. Who manages whom and for what ends becomes problematic indeed when technical elites and elites from the armed forces collide in this fashion with other groups in society.

When such collisions led to coups d’état, bringing military personnel to power, it was difficult for the new rulers to retain the cohesion and morale that allowed them to seize power in the first place. Programs for reform, however heartfelt at the moment of taking office, were always difficult to put into practice; and when opportunities for personal enrichment and sensuous enjoyment multiplied, as always happened to men in possession of political power, ideals nurtured in the barracks and military schools were likely to go by the board. Often as not, such betrayal deprived the military regime of legitimacy in its own eyes and in the eyes of others. Most modern military dictatorships have therefore been short-lived.

Alliance of throne and altar constituted the traditional time-tested solution to the problem of sustaining legitimacy for long periods of time. The difficulty in the twentieth century was to find a faith and priesthood capable of supporting governments that had to rule in the absence of any well-defined popular consensus. The secular faiths of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries showed signs of losing their power in industrially advanced countries. Indeed, the weakening of public consensus was a register of this decay. To be sure, Marxist and nationalist ideals had proved effective for mobilizing predominantly peasant populations against European administrators and foreign capitalists in the immediate postwar decades. But when revolutionary parties took power and confronted the practical tasks of daily administration, nationalist principles and Marxist faith constituted sadly inadequate guides to action. Disappointment and disillusion therefore regularly set in.

In some parts of the world, traditional religions, sometimes in sectarian form, offered an alternative. This was especially true in Islamic lands. An age-old antagonism to Christianity and Judaism dating back to the very foundation of Islam, made it easy to attack foreign influence and corruption and rally mass followings for the defense of the true faith. But a regime seeking to be true to the Koran had difficulty in coping with twentieth-century technology since those who mastered the technology of the West were unlikely to remain fanatically faithful to Mohammed’s revelation.

An enemy at the gates has always been the best substitute for spontaneous consensus at home. Fear of what a foe would do if allowed to cross the frontier will often breed obedience, if only on the ancient principle “better the scoundrels one knows that the scourge one fears.” Wars and rumors of war against near neighbors can therefore be expected to flourish luxuriantly in those parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America where public consensus is weak and precarious. Peasant ways of life face enormous strain wherever population has become too great to allow the rising generation to find enough land to live on and raise a family in traditional fashion. The restless and impassioned search for new faiths, new land, new ways of life provoked by such circumstances is sure to disturb any and every form of constituted governmental authority until such time as the demographic crisis somehow diminishes. To judge from Europe’s history between 1750 and 1950, this will take a long time and may cost many lives.

Wars and preparations for wars are therefore likely to remain very prominent in most of the Third World. The enormous arms buildup occurring in those lands since the 1960s testifies to this fact. As in earlier ages, such expenditures are not always purely wasteful from an economic point of view. New skills, needed to maintain such complicated pieces of machinery as modern combat airplanes, have wider application. Given suitable conditions, they can, as in nineteenth-century Japan, promote industrial growth. On the other hand, heavy investment in armaments may choke off other kinds of development. Overall, there seems to be no coherent relationship between Third World rates of economic growth since 1945 and rates of military expenditure.18

Inability to maintain domestic peace, however, is a sure path to economic regression. Insofar as maintenance of public order becomes problematic so that governments fear their own people as much or more than any external foe, police equipment takes precedence. Recent statistics show that since the mid 1960s new nations have invested more heavily in police forces than in armament aimed at foreign enemies.19 Whether better-organized repression will suffice to prop up existing regimes in the absence of real consent remains to be seen. Military forms of discipline and policies intended to insulate armed personnel from the rest of the population surely offer some prospect of success. European sovereigns of the Old Regime, after all, exercised this sleight of hand triumphantly in times past. Moreover, as armaments become more expensive as well as more lethal, small professional armies are likely to supplant the mass armies of conscripts that dominated European warfare in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. If so, governments and their armed forces can perhaps afford to dispense with popular support, and rely on force and the threat of force, exercised by specialized professionals kept systematically separate from the subjected population at large. Such a pattern of governance would conform to the norms of the past, however much at odds they may be with modern political rhetoric and democratic theory.

On the other hand, contemporary forms of mass communication probably act in an opposite sense and make such old-fashioned polarity between armed rulers and a subject population persistently unstable. To be sure, selective recruitment into the armed services from some special segment of the population can be counted on to induce a social distance between the armed forces and ordinary civilians and subjects. But whether such an armed force can monopolize organized violence within state boundaries depends largely on whether discontented revolutionary groups have access to arms; and this in turn depends on the policies of other governments as well as on the fanaticism of the revolutionaries. As long as the globe is divided among rival states, revolutionaries have a good chance of finding some foreign patron and supplier of arms. Under these circumstances, strengthening the police and army does not seem likely to assure political stability in those parts of the world where a rural population surge generates widespread and radical discontent with the way things are.

In Europe, the United States, and the Soviet Union population pressures are of a different kind. How to come to terms with immigrants and aliens, whether Latino in the United States or Moslem in Europe and the USSR is sufficiently delicate to require very careful management. But the problem does not threaten the existing political order. Neither does the divergence between the interests of the military-technical elite and the rest of society, however real the competition for resources may be. For half a century, military-industrial elites have nearly always prevailed over domestic rivals without much difficulty. Time and again fear of the foreign foe persuaded the political managers and the population at large to acquiesce in new efforts to match and overtake the other side’s armament. The escalating arms race, in turn, helped to maintain conformity and obedience at home, since an evident outside threat was, as always, the most powerful social cement known to humankind.

Yet how far such shadow boxing can go is problematical. Atomic warheads changed the rules; and the absurdity of devoting enormous resources to the creation of weapons no one dares to use is obvious to all concerned. This means that the vast armed establishments currently protecting the NATO and Warsaw Pact powers against one another are liable to catastrophe not merely from the external attack they are designed to survive but also from internal decay. Such decay is facilitated by the way in which long-standing notions of heroism and the military calling meet with frustration in technically up-to-date armies and navies. Push-button war is the antithesis of muscular prowess; and the niggling routine of bureaucratic record-keeping is no less at odds with naive but heartfelt feelings about what fighting men should be and do. Such tensions are as old as the bureaucratization and industrialization of war; but the dawn of the rocket age, with its overwhelming preponderance of action at a distance, from which the muscular and merely human input has almost drained away, constitutes a mutation of the art of war with which soldiers’ psychology does not easily keep up.20

All the same, short of defeat in war, drastic demoralization of military personnel is perhaps unlikely. Traditional methods for inculcating and sustaining military discipline remain very effective. Close order drill has lost none of its capacity to arouse elemental sociality among those who participate in it hour after hour. Its utter irrelevance in modern combat may not matter. Other rituals and routines, too, may arise and exert self-perpetuating power to channel and stabilize behavior both within the armed services and in civil society at large. Routine and ritual constitute the standard substitute for faith of the incandescent, personal, and revolutionary kind. As such faiths—Marxist or liberal-democratic, as the case may be—fade towards mere shibboleth, ritual and routine alone remain.

In times past, routine and ritual prevailed in European and all other armed forces. Technical upheavals were few and far between, however important for the ebb and flow of peoples and the tides of victory and defeat. Perhaps the extraordinary disturbance arising across the past century and a half, ever since the industrialization of war got seriously under way, will eventually be contained so that the world’s armed forces can again sink back into the sustaining and restraining regime of unchanging routine.

On the other hand, as long as rivalry between mutually suspicious states continues, deliberate organized invention seems certain to persist, cost what it may. Absolute economic limits are scarcely in sight. Every productive resource not needed for bodily life is, in principle, available for defense; and the enhanced productivity of automated machinery is so great that the practical limits on military expenditure are limits on the efficiency of human organization for war rather than anything else. Once again one comes up against the question of consensus and obedience. Material limits are comparatively trivial.

One might, perhaps, suppose that absolute physical limits to weaponry were close at hand. After all, escape velocities for ballistic missiles were attained as long ago as 1957. The next generation of weaponry may act from space with the speed of light, as do control and guidance systems already in use. But attainment of the physical world’s absolute speed limit would not hinder rival research and development teams from seeking to improve control and precision of aim, while developing methods of protection against interference from without. Stabilization of weapons systems, if it ever comes, seems unlikely to arise from exhaustion of the frontiers of scientific research and engineering.

To halt the arms race, political change appears to be necessary. A global sovereign power willing and able to enforce a monopoly of atomic weaponry could afford to disband research teams and dismantle all but a token number of warheads. Nothing less radical than this seems in the least likely to suffice. Even in such a world, the clash of arms would not cease as long as human beings hate, love, and fear one another and form into groups whose cohesion and survival is expressed in and supported by mutual rivalry. But an empire of the earth could be expected to limit violence by preventing other groups from arming themselves so elaborately as to endanger the sovereign’s easy superiority. War in such a world would therefore sink back to proportions familiar in the preindustrial past. Outbreaks of terrorism, guerrilla action and banditry would continue to give expression to human frustration and anger. But organized war as the twentieth century has known it would disappear.

The alternative appears to be sudden and total annihilation of the human species. When and whether a transition will be made from a system of states to an empire of the earth is the gravest question humanity confronts. The answer can only come with time.