Strains on Europe’s Bureaucratization of Violence, 1700-1789

European rulers’ remarkable success in bureaucratizing organized violence and encapsulating it within civil society continued to dominate European statecraft throughout the eighteenth and well into the nineteenth century. The victories Europeans regularly achieved in conflicts with other peoples of the earth during this period attested the unusually efficient character of European military arrangements; and such successes, in turn, facilitated the steady growth of overseas trade which helped to make the costs of maintaining standing armies and navies easier for Europeans to bear. Hence European rulers, especially those located towards the frontiers of European society, were in the happy and unusual position of not having to choose between guns and butter but could instead help themselves to more of both, while their subjects—at least some of them—were also able to enrich themselves.

No doubt a long succession of good harvest years and the spread of American food crops, mainly maize and potatoes, to European soil had more to do with the prosperity of the first half of the eighteenth century than any merely governmental action. But the acceptability of Old Regime military-political patterns was surely enhanced, for all concerned, by the economic growth that set in all across the face of Europe, from Ireland in the west to the Ukrainian plains in the east, during the comparatively peaceful decades that followed the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714.

Nevertheless, in the second half of the eighteenth century, sharp challenges to existing political-military patterns in Europe made themselves felt. One fundamental factor in the mounting disequilibrium was the onset of rapid population growth after about 1750. In countries like France and England this meant that rural-urban balances began to shift perceptibly, as migrants from a crowded countryside set out to make their fortunes in town, or, in a few cases, crossed the Atlantic to take up land in North America.1 How to cope with a growing rural population when most of the readily cultivable land was already in tillage became critical throughout northwestern Europe in the second half of the eighteenth century. Only later did comparable problems confront central and eastern European societies, for when the eighteenth-century population surge set in, there was much untilled land in those parts that could be brought under cultivation by applying existing agricultural methods without resort to exceptional or costly capital improvements. By way of contrast, in England, France, Italy, the Low Countries, and Germany west of the Elbe, generally speaking, any extension of cultivation to new ground did require some sort of costly and unusual preparation of the land—fertilizing it, draining it, or altering its composition by bringing in sand or marl or some similar material to mix with the existing soil. Consequently, in eastern Europe until after the middle of the nineteenth century rising population constituted not a problem but an opportunity to make grainfields out of what had before been left as woods, wasteland, or rough pasture—without altering patterns of rural labor or customary routines and social relations in any significant degree.

Another way of describing the difference between western and eastern Europe between 1750 and 1830 is this: in the east, population growth allowed simple replication of already familiar patterns of village life. Export of local products—grain, livestock, timber, or minerals—though increasing in quantity with the growth of population was not massive enough to provoke any really new forms of social organization. In the west, however, strains were greater. The countryside could absorb only a portion of the expanding labor force. Urban occupations had to be found for a greater proportion; and insofar as this proved difficult or impossible, manpower was likely to shift towards predatory activities, whether such predators were licensed by public authority as privateers or enlisted as soldiers, or acted without public legitimation as highwaymen, brigands, or ordinary urban thieves.

In eastern Europe, as men became more abundant, soldiers became easier for the Prussian, Russian, and Austrian governments to recruit. Armies increased in size, especially the Russian; but like the multiplying villages from whence the soldiers came, such increases in size did not involve change in structure. In western Europe, however, the mounting intensity of warfare that set in with the Seven Years War (1756–63) and rose to a crescendo in the years of the French Revolution and Napoleon (1792–1815) registered the new pressures that population growth put on older social, economic, and political institutions in far more revolutionary fashion. Divine right monarchy went down, never to be fully resurrected; but Old Regime military institutions continued to regulate even the French levée en masse of 1793. As a result, Napoleon’s defeat in 1815 allowed the victorious powers to restore a plausible simulacrum of the Old Regime. The traditional military order did not begin to break up irretrievably until the 1840s, when new industrial techniques began to affect naval and military weaponry and organization in radical and fundamental ways. Until that time, despite the revolutionary aspiration and achievements of the French and despite technical advances in British manufactures (which we are also accustomed to call revolutionary) the organization and equipment of European armed forces remained fundamentally conservative, even when, as in France after 1792, the command structure of the army was harnessed to the accomplishment of revolutionary political purposes.

Yet even if the long-range result can be described as conservative, a closer examination of the challenges to European military establishments between 1700 and 1789 will show how the management of armed force remained persistently precarious, even when the Old Regime was apparently most secure. These challenges were of two sorts. One recurrent challenge arose from geographical expansion of the territories organized for the support of European-style armed establishments, thereby altering power balances among the European states. A second kind of challenge stemmed from technical and organizational innovations within the system itself, characteristically provoked by failure in war on the part of one or another of the European great powers. Each of these challenges requires somewhat closer consideration, as preface to a discussion of what did and did not happen to the organization and management of European armed forces during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods.

Disequilibrium Arising from Frontier Expansion

Any human skill that achieves admirable results will tend to spread from its place of origin by taking root among other peoples who encounter the novelty and find it better than whatever they had previously known or done. This was conspicuously the case with the style of army organization that came into being in Holland at the close of the sixteenth century and spread, as we saw in the last chapter, to Sweden and the Germanies, to France and England, and even to Spain before the seventeenth century had come to a close. During the eighteenth century, the contagion attained far greater range: transforming Russia under Peter the Great (r. 1689–1725) with near revolutionary force; infiltrating the New World and India as a by-product of a global struggle for overseas empire in which France and Great Britain were the protagonists; and infecting even such a culturally alien polity as that of the Ottoman empire.2

The range of market-regulated activity which undergirded and sustained the European pattern of bureaucratized armed force expanded even more widely during the same decades, weaving the everyday activities of countless millions of Asians, Africans, Americans, and Europeans into a more and more coherent system of exchange and production. Even Australia began to enter into the European-centered and managed economy before the century closed. Only the Far East remained apart, owing to Chinese and Japanese governmental policy which deliberately restricted European trade to marginal and indeed, in the case of Japan, to economically trivial proportions.

Expansion on such a scale wrought drastic alterations in the internal European balance of power. States located towards the margins of the European world—Great Britain and Russia in particular—were able to increase their control of resources more rapidly than was possible in the more crowded center. The rise of such march states to dominance over older and smaller polities located near a center where important innovation first concentrated is one of the oldest and best-attested patterns of civilized history.3 What happened among the great powers of Europe in the eighteenth century, therefore, ought to be understood as no more than a recent example of a very old process, a process which, of course, continued into the nineteenth century and has by no means come to any final equilibrium point in the twentieth.

European expansion in the eighteenth century, however, occurred so symmetrically that no one state achieved an overwhelming preponderance over all others. Until the 1780s, France and Britain rivaled and roughly counterbalanced each other in sharing enhanced resources from overseas expansion, while in the east Austria and Prussia disputed with Russia (though with less and less success as the century advanced) the advantages of a position on Europe’s landward frontier. European political pluralism therefore survived, despite some rather sharp perturbations. The survival of a plurality of competing states, in turn, maintained Europe’s uniqueness compared to the major civilizations of Asia, where gunpowder empires created in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries continued to prevail, sometimes, as in China, in a flourishing condition, and sometimes, as in India, in increasing disarray.

The multiplicity of European states produced an enormous political confusion. Diplomatic and military alignments shifted from time to time in kaleidoscopic fashion. All the same, it seems worth suggesting that a noticeable change came to the system after 1714, when the War of the Spanish Succession ended. By that date, the coalition of states that had formed to check the preponderance of Louis XIV’s armies on the continent of Europe had won a qualified success. Instead of renewing full-scale combat on European soil, French energies in the relatively peaceful forty years that followed turned towards overseas enterprise in the islands of the Caribbean, in North America, in India, and in the Mediterranean Levant. Merchants and planters met with great success: French overseas trade actually increased more rapidly than that of Great Britain, though since the British started the century at a higher level, French trade never overtook British in absolute volume.4

National rivalries, however sharp, were effectually adjusted by monopolizing trade in particular ports and regions of America, Africa, and the Indian Ocean shorelines. Such local monopolies were sustained by local armed force—forts, garrisons, settlers—supplied and knitted together by the coming and going of ships which were themselves almost always armed with heavy cannon and could, in emergency, be supplemented by a detachment of warships sent from the home country to reinforce, protect, and extend imperial footholds overseas.

The growing French and British trade empires interpenetrated older European overseas establishments in complicated and shifting fashion. After 1715, home governments in Holland, Spain, and Portugal could no longer protect their imperial possessions against the assault of a major expeditionary force launched from Europe. Yet these older overseas empires survived precariously and without really major territorial loss. This was largely due to the fact that legally or by tacit disregard for the law Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch imperial administrators admitted French and/or British traders to do business in the ports they controlled, thus giving the two greatest sea powers of the century the practical benefits of trade without requiring them to pay the costs of local administration. Towards the end of the century, moreover, Spanish imperial resources in the Americas began to increase. The collapse of Amerindian populations, which had provoked radical depopulation and labor shortages in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, bottomed out after about 1650, at least in Mexico and Peru. Slowly, at first, and then with accelerating rapidity, population growth began to permit fuller exploitation of local resources.5 Brazil, too, started to flourish and so did the English colonies of North America. As a result, American manpower and local supplies permitted more and more significant local defense.

In this process of overseas expansion, market behavior played the organizing role. Profits from trade supported European overseas activity and increased its scale decade by decade. At the same time, profits were guaranteed by ready resort to armed force. No other part of the earth supported an armed establishment as efficient as those which European states routinely maintained; and nowhere outside of Europe was the management of armed force in the hands of persons sympathetic to or much concerned about traders’ profits. European rulers, by contrast, had been accustomed since the fourteenth century to finding themselves enmeshed in a commercial-financial system for organizing human effort. Even when reluctant and uncomprehending, kings and ministers depended on market-regulated behavior for the supply and maintenance of their armed forces and of their governmental command structure in general. In England after the 1640s and in France after the 1660s rulers ceased to struggle against the constraints of the market in the fashion Philip II of Spain and most of his contemporary rulers had done. Instead a conscious collaboration between rulers and their officials on the one hand and capitalist entrepreneurs on the other became normal.

The rise of French and British overseas enterprise registered and reflected the relatively smooth cooperation between business mentality and political management that came to prevail in those countries. Instead of looking upon private capital as a tempting and obvious target for confiscatory taxation, as rulers in other parts of the world regularly did, the political masters of western Europe came to believe, and acted on the belief, that by setting precise limits to taxation and collecting designated sums equably, private wealth and total tax receipts could both be made to grow. Wealthy merchants and money-lenders could afford to live in London, Bristol, Bordeaux, or Nantes under the jurisdiction of the British or French governments, instead of seeking refuge, as in earlier centuries, in independent cities governed by men of their own ilk.

For men of commerce the advantage of living under a militarily formidable government was obvious: they could rely on a more efficacious and far-ranging military protection for their enterprise than when small, comparatively weak states alone permitted them free pursuit of the gains of the market. The advantage to kings and ministers of permitting a vigorous capitalist class to pursue private gain wherever a prospective profit could be discovered became equally obvious in the eighteenth century, for their activities began to swell total tax receipts and made the maintenance of standing armies and navies, which had been financially difficult in the seventeenth century, relatively easy.6

Cooperation between rulers and capitalists at home was matched by cooperation overseas. Indeed, the capacity to protect themselves and their goods at comparatively low cost was the central secret of European commercial expansion in the eighteenth century. It arose partly from the technical superiority of European ships and forts combined with the abundance and comparative cheapness of iron cannon. An equally critical element in European merchants’ lower protection costs was the superior organization and discipline which European-trained troops, officers, and administrators commonly exhibited, even when stationed half the globe away from the seat of sovereignty and source of instruction, pay, and promotion upon which their obedience ultimately depended.

Many factors entered into this phenomenon, among them the psychological effect of repeated drill that made soldiers into obedient, replaceable parts of a military machine. However ill-supplied or poorly disciplined European troops stationed overseas may have seemed to an officer newly arrived from European parade grounds, their superiority over Asian, African, or Amerindian armed forces became apparent whenever local collisions occurred. In India, for example, when struggle for dominion over that vast land broke out between French and English military entrepreneurs, ridiculously small European contingents regularly played decisive roles, less because of their weaponry than because of their dependable obedience on the battlefield and their maneuverability in the face of an enemy.7

The really important result of the balance between superior armed force and almost untrammeled commercial self-seeking that characterized European ventures overseas in the eighteenth century was the fact that the daily lives of hundreds of thousands, and by the end of the century of millions, of Asians, Africans, and Americans were transformed by the activity of European entrepreneurs. Market-regulated activity, managed and controlled by a handful of Europeans, began to eat into and break down older social structures in nearly all the parts of the earth that were easily accessible by sea. Africans, enslaved by raiding parties, marched to ports for shipment across the Atlantic, and consigned to work on sugar plantations, represent a brutal and extreme example of the way the profit motive could and did transform older patterns of life fundamentally. Indonesians, required to work in spice groves by local princelings who in their turn obeyed Dutch commands, were less completely abstracted from their accustomed routines and social setting; and the same was true of Indian cotton manufacturers who produced cloth for the East India Company to sell in markets hundreds or even thousands of miles removed from their spinning wheels and looms. Tobacco and cotton growers in the Mediterranean Levant and in North America represent yet another degree of personal independence vis-à-vis the merchants and brokers who put the product of their labor into international circulation. But all such people shared the fact that their daily routines of life came to depend upon a worldwide European-managed system of trade, in which the supply of goods, credit, and protection affected the livelihood, and often governed the physical survival of persons who had no understanding of, nor the slightest degree of control over, the commercial network in which they found themselves enmeshed.

No doubt Europeans gathered most of the profits into their own hands; but specialization of production also meant that wealth increased generally, even if it was very unevenly distributed among social classes and between European organizers and those who worked at their command or in response to their inducements. Even in Africa, where the devastation of slave raiding certainly crippled many communities and blasted innumerable human lives, it was also the case that new techniques and skills—most notably the spread of maize cultivation—enhanced African wealth; and the power of strategically situated African states also clearly tended to grow, thanks in part to access to weapons supplied by European traders.8

In the New World, as in the Old, inland regions where transport and communications were difficult remained slenderly affected by the network of trade that European enterprise wove along the shorelines of the Atlantic and Indian oceans. Yet the reach of the world market could be very long. In the frozen north, for example, the high value placed on furs led European traders to penetrate the entire breadth of North America before the eighteenth century came to its close. They entered into relations with local tribes, offering metal tools, blankets, and whiskey in exchange for furs. As a result, older Amerindian patterns of life underwent rapid and irreversible change. Russian fur traders did the same to the populations of Siberia, and in fact crossed to Alaska as early as 1741. Accordingly, in the last decades of the eighteenth century, Spanish and British claims to the Pacific coastline of North America met and collided with the expanding Russian fur trade empire, an encounter that dramatizes how Europe’s overseas expansion was matched by an equally remarkable Russian eastward expansion.

Europe’s land frontier was, indeed, almost as important in altering European power balances as the overseas trade empires that nourished French and British power so remarkably in the early eighteenth century. The vast Siberian wilderness—though impressive on the map—mattered less than the occupation of steppelands in the Ukraine and adjacent regions by grain farmers. Their labors increased European food production very substantially in the course of the century and provided a human and material base for the growth of the Russian empire.

Russia was not the sole power to profit from the spread of agriculture into the steppelands of eastern Europe. Indeed the seventeenth century had seen a complex struggle for dominion over the western steppes in which local polities like the principality of Transylvania as well as the Polish nobles’ republic competed with the three more distant monarchies of Turkey, Austria, and Russia for control over this part of the world.9 The upshot, by the close of the eighteenth century, definitely favored Russia, for the portions of the steppe that fell to Turkey (Rumania) and to Austria (Hungary) were much less extensive than Russia’s portion (the Ukraine and grasslands eastward into central Asia). As for Poland, internal quarrels so weakened that country that it disappeared entirely as a sovereign state through three successive partitions, 1773, 1793, and 1795.

Before Poland’s political demise dramatized the sharp changes that had come to power-relationships in eastern Europe, another claimant to great-power status arose: the kingdom of Prussia. Like their territorially more impressive neighbors, Prussian rulers benefited from governing a march state. Prussia’s comparatively large size among German principalities reflected its medieval frontier history. Even as late as the eighteenth century, by importing techniques long familiar in more westerly lands—artificial drainage and canalization above all—Prussians were able to bring considerable amounts of new land under cultivation, thereby increasing the country’s wealth.10

But the basis of Prussia’s political success was the superior rigor of its organization for war—a rigor that dated back to the seventeenth century when heartfelt local reaction against Swedish depredations found effective institutional expression within the lands of the Hohenzollern princely dynasty. After the war, the Great Elector, Frederick William (r. 1640–88), was able to beat down local opposition to centralized taxation. This allowed him and his successors to maintain an army large enough to count in European wars, despite the narrow extent and scant resources of the original domains of the electorate. The Great Elector, like many another German prince, built up his army by accepting subsidies from foreign powers to supplement local taxation. Not until the reign of Frederick William I (1713–40) did the Hohenzollerns become financially self-sufficient. This became possible only through a remarkable fusion between the nobility and the officer corps which made the king’s service (the royal title dated from 1701) the normal career for rural landholders. The “king’s coat” worn without badges of rank by all officers below general rank, and by Frederick William I as well, made all officers equals, and equally the servants of the house of Hohenzollern. Both officers and soldiers lived very frugal, indeed poverty-stricken lives, yet a collective spirit of “honor” and sense of duty raised the Prussian army to a level of efficiency—and cheapness—no other European force came near to equaling. As a result, a succession of canny rulers added to the size of the Prussian army and to the extent of Hohenzollern territories, but the leap to great-power status came only when Frederick the Great (r. 1740–86) seized the province of Silesia from Austria and made good his usurpation in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48).11

The disturbances to older balances of power within Europe which frontier expansion thus provoked were registered in the diplomatic revolution that preceded the Seven Years War (1756–63). The rivalry between the Hapsburg and French monarchies, which dated back to their quarrels over the Burgundian inheritance (1477) and around which the rivalries of lesser European states had long revolved, was replaced after 1756 by half-hearted cooperation between France and Austria aimed against their increasingly formidable respective rivals—Great Britain and Prussia. Yet despite the apparent magnitude of French and Austrian resources, it was the British and the Prussians who won the war. Great Britain’s victories overseas drove the French from Canada and all but eliminated them from India as well. Recovery of French naval power, though real enough by 1788, did not suffice to repair the setback to French commerce that the defeats of 1754–63 had wrought.

Prussia’s survival against the assault of the Austrian, French, and Russian armies was a tribute to the efficiency of Prussian drillmasters, to the morale of the Prussian officer corps, and to Frederick II’s personal abilities as a general. Yet it is also the case that cracks in the alliance were what allowed Prussia to survive. In particular the withdrawal of Russian forces from the war when a new tsar, Peter III, came to the throne in 1762 gave Frederick a breathing space he desperately needed; and in the next year, their ill success against Great Britain persuaded the French to withdraw from the war, thus compelling the Austrians also to make peace (1763).

Prussia’s military reputation rose to a pinnacle on the strength of Frederick’s remarkable survival against what had appeared to be overwhelming odds. This did much to disguise from contemporaries the pivotal reality of eastern Europe, to wit, the rise of Russian power. Events in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have likewise made Prussian (later German) history seem central to the history of Europe as a whole. Yet one can argue very plausibly that Russia was the state that profited most from Frederick’s aggressive policies. (He had precipitated war in 1740 and again in 1756 by invading Hapsburg lands.) The ill-feeling that divided Austria from Prussia after 1740 meant that cooperation between those two states became next to impossible. Their mutual distrust made it easy for Russia to use the army that Peter the Great had successfully remodeled along European lines to continue expansion at the expense of weak and comparatively ill-organized polities abutting on Russia’s frontiers. Thus Russia secured the lion’s share of Poland, 1773–95; annexed the Crimea in 1783; extended its frontiers against the Ottoman empire into the Caucasus on the east and to the Dniester on the west by 1792; and advanced into Finland at the expense of the Swedes as well (1790). Rapid development of grain production in the Ukraine together with industrial and commercial expansion in the Urals and in central Russia supported the rise of the imperial power to unexampled heights. Under Catherine the Great (r. 1762–95) Russia was able as never before to organize its resources of manpower, raw materials, and arable land to support armed forces whose efficiency approached that of the armies and navies of western Europe. Russia, in short, was catching up to European levels of organization; as this occurred the advantages of size began to tell.

British success in the Seven Years War against France was also, in part, the result of mobilization of resources drawn from far-flung territories in North America, India, and regions in between. But whereas in the Russian case, mobilization rested ultimately on serf labor, directed by an elite of officials and officially licensed private entrepreneurs, in the British case compulsion was largely eclipsed by reliance on market incentives registered in private choices made by relatively large numbers of individuals. Yet slave labor on Caribbean plantations and press gangs for manning the navy also played prominent roles in maintaining British power. So the contrast between a frontier mobilization through command à la russe and mobilization through price incentives à l’anglaise is only a matter of degree. But the degree of compulsion mattered. Russian methods (like the slave economies of the sugar islands) were often quite wasteful of manpower, whereas private efforts to maximize profits tended to reward economies in the use of all the factors of production. Market behavior, in short, induced a level of efficiency that compulsion rarely could match.

In particular, responsiveness to a more or less free market meant that new techniques, capable of effecting real improvements in production, were sometimes able to win acceptance in the British system of economic management, whereas in Russia impulses to invent or to propagate new inventions were sporadic at best. Harassed administrators were almost always sure to decide that it was better to meet their superiors’ instructions by adhering to familiar methods of work, and to increase production, if that was what was wanted, either by driving the labor force harder or by securing more workers. The alternative of trying some newfangled device that was sure to detract from short-run results and might not work in the long run either, was seldom even considered. Only when a technique had proved successful abroad was it worthwhile for Russian administrators to disrupt existing arrangements by importing the novelty—often along with foreign technicians to instruct the local work force in the use of the new methods.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century Russian armaments and Russian armies had been built up in this fashion by Peter the Great. The stability of European military organization and technique in the following decades meant that catching up and outstripping smaller powers became comparatively easy for Russian administrators and army officers to achieve. The success of Russian arms, especially in the second half of the eighteenth century, attests their ability to do so.12

The superior flexibility of market behavior in making room for technical innovation eventually allowed Great Britain, and western Europe generally, to steal a march on the Russians by raising economic and military efficiency to a level that eclipsed Russian and east European achievements. This did not become clear until after 1850, however. Before then, from 1736 to 1853, Russia’s ambitions were only precariously contained by balance-of-power diplomacy and by the remarkable military explosion that the French Revolution generated.

The balance of power also worked to minimize the overseas preponderance that Great Britain seemed to have won in 1763. In particular, the disappearance of the French threat from Canada made British relations with the North American colonists more difficult than before; and when King George III’s government sought to compel the colonists to help pay for the war, discontent turned into open rebellion. Soon France came to the aid of the American rebels (1778) and other European powers either joined the French or expressed their dislike of a British overseas trade monopoly by an “armed neutrality” that was inimical to British interests. By 1783, Great Britain was compelled to admit defeat and recognized the independence of the United States of America.

In this way, then, the European state system partially counteracted the rise of British and of Russian power, and adjusted itself to the upheavals that resulted from the expansion of European economic-military organization to extensive new regions of the earth between 1700 and 1793.

Challenges Arising from Deliberate Reorganization

European adjustment to territorial expansion was, in a sense, quite normal—a semiautomatic consequence of balance-of-power calculations on the part of political leaders. It was a pattern that could be matched by similar behavior in other times and places—e.g., among Greek city-states responding to Athens’ rise in the fifth century, or among the principalities of Italy in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in response to the rise of Milanese and Venetian power. On the other hand, the reorganization of political, economic, and military management that began to manifest itself as the eighteenth century neared its close was unique, not because other states in other ages had not also sought to increase their military power by internal reorganization, but because the scope and complexity of the techniques accessible to European administrators and soldiers had become enormously greater than in any earlier age. Rational calculation so enlarged the scope of deliberate action that, before the end of the century, managerial decisions began to change the lives of millions of persons.

Military manpower and materiel were clearly in the forefront of this managerial transformation. In the seventeenth century armies and navies had become, so to speak, works of art in which human lives as well as ships and guns were shaped according to preconceived plans for quite specialized uses. Results were spectacular, as we saw in the last chapter. In the early part of the eighteenth century further changes were minimal. After 1750, however, as population growth began to alter social reality everywhere, experts started to tinker with existing ways of managing and deploying armed force in the hope of escaping limits inherent in the older system. Nothing dramatic was achieved before 1792; but long before then military reformers foreshadowed the mass mobilization brought about by the French Revolution.

By the mid-eighteenth century, four limits in existing patterns of military organization had become apparent. One of these was the difficulty of controlling the movements of an army of more than about 50,000 men.13 Even with the help of galloping aides-de-camp a general could not usually know what was happening when a battle front extended much further than a spy glass could distinguish friend from foe; and tactical control, even when bugles supplemented shouted commands, could not reach beyond the battalion level, i.e., 300–600 men. New forms of communication and accurate topographical maps were necessary before effective command of larger field armies could become possible.

Supply constituted a second and very powerful constraint on European armies. The perfection of their drill gave European armies unique formidability and flexibility at short range and for a few hours of battle. But at longer range, force could be brought to bear in a new location only by slow, sporadic stages. Available transport simply could not concentrate enough food to support thousands of horses and men if they kept on the move day after day. The Prussian army under Frederick the Great, for example, assuredly the most mobile and formidable European army of its day, could march for a maximum of ten days before a pause became necessary to bring up bake ovens and rearrange supply lines from the rear. Fodder for horses was the most difficult of all, for it was too bulky to travel far. Frederick’s soldiers, indeed, sometimes stopped to cut hay for the horses even when bread supplies for their own nourishment were in hand.14 Living off the country was possible at appropriate seasons of the year but risked loss of control over soldiers who might be expected to prefer plundering unarmed peasants to deploying against the enemy. For this reason, together with the realization that a devastated countryside could not pay taxes, eighteenth-century rulers sought to supply their armies from the rear, thereby submitting to drastic limitations on strategic mobility.

Supply of weapons, gunpowder, uniforms, and other equipment did not normally set limits on military enterprise. Costs of such items were comparatively small.15 Food, fodder, horses, and transport were what usually ran short. All the same, the artisan production of muskets, cloth, shoes, and the like, and the manufacture of artillery pieces in state arsenals could not easily be expanded. Accordingly, wars were usually fought with stocks accumulated beforehand. When serious losses occurred, as happened to Prussian armies in the Seven Years War, purchase abroad became necessary, and this of course required money. The principal international arms market continued to center in the Low Countries, most notably at Liège and Amsterdam.16

A third limit was organizational and tactical. Europe’s standing armies carried into the eighteenth century many traces of their origin from privately raised mercenary companies. As a result, proprietary rights often conflicted with bureaucratic rationality in matters of recruitment, appointment, and promotion. Professional skill competed with patronage and purchase as paths to advancement, while both were tempered by the principle of seniority on the one hand and by acts of valor in battle on the other. Appointments and promotion often reflected the king’s personal choice or those of his minister of war.

The consequent erratic and changeable patterns of personnel administration found expression in France through heated debates over tactics. Rival groupings of officers embraced rival doctrines, and used those doctrines as tools in their struggle for places in the military hierarchy. But claim and counter claim could be settled only by experimental field maneuvers or by test firings and the like. Debate, fueled by clique rivalries for promotion, therefore, had the remarkable effect in France of opening the door on systematic testing of new materiel (especially field artillery) and tactics. Under these pressures, the fixity of Old Regime military practices had begun to crumble even before the French Revolution came along to accelerate and magnify what rivalry among professionals had already begun.

The limits of command technique, of supply, and of organization were all connected with and sustained by a fourth limit: the sociological and psychological restraints that went along with the professionalization of warfare. As a handful of sovereign rulers monopolized organized violence and bureaucratized its management in Europe, war became, as never before, the sport of kings. Since the sport had to be paid for by taxation, it seemed wise to leave the productive, taxpaying classes undisturbed. Peasants were needed to produce the food, and townsmen were needed to provide the money that supported governments and their armed establishments. For soldiers to interfere with their activities was to endanger the goose that laid the golden eggs. Yet the exclusion of the great majority of the population from any but a passive, taxpaying role set a ceiling upon the scale and intensity of war which the French Revolution was destined to discard.

Long before that breakthrough, however, inventions of scores of experts and technicians had prepared the way for the revolutionary expansion in the scale of warfare. Such efforts got seriously underway whenever a great power met with unexpected failure in war. Thus, for example, their lack of success first against the Turks (1736–39) and then against the Prussians and French in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48) led Austrian authorities to develop more mobile and accurate field guns than had been known before.17 The improved Hapsburg artillery gave the Prussians a nasty surprise in the Seven Years War; but after its conclusion the state that had most to regret was France, whose former primacy on the battlefield had been called into question by defeats at the hands of both the Prussian (Rossbach, 1757) and English-German armies (Minden, 1759). Not surprisingly, therefore, France became the most important seat of military experimentation and technical innovation in the decades that intervened between the Peace of Paris in 1763 and the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789.

Innovation, whether among the Austrians, French, or British (especially after their defeat in 1783), pressed hard against each of the limits to the management of war mentioned above. Thus, for example, the limits of command based on coup d’oeil and mounted reconnaisance were slowly overcome by the development of accurate mapping, changes in command organization, and resort to written orders prepared in advance by specially trained staff officers. The French began to compile the first accurately surveyed small-scale maps suitable for staff use in 1750, but it took many years before all of Europe was mapped on such a scale as to allow a commander in the field to plan each day’s march from a map.18 Nevertheless, as early as 1763 a French general, Pierre Bourçet, had grasped the possibility, and, in the ensuing years, actually drew up detailed plans for campaigns along French borders and for the invasion of England. He prepared a handbook in 1775 for private circulation within the French army entitled Les principes de la guerre de montagne in which he explained how a commander should plan troop movements and supply on a day-by-day basis from maps; and when Napoleon invaded Italy in 1797 he is said to have used Bourçet’s plan for crossing the Alps and taking the Austrians by surprise.19

Control of army movements by means of maps required a staff of experts in map reading and logistics. Bourçet understood this and, in 1765, set up a school for training aides-de-camp in the new art. It was disbanded in 1771, reestablished in 1783, and suppressed again in 1790. This on-again off-again pattern reflected personal and doctrinal disputes within the French army that characterized the entire period between the end of the Seven Years War and the outbreak of the Revolution twenty-six years later.

Such an atmosphere proved fertile in other directions as well. High command, relying on maps and written orders prepared in advance by specially trained staff officers, could perhaps hope to control armies three or four times the size that Maurice de Saxe had judged to be the upper limit of effective command; but to do so a general needed to break his army up into parts, since existing roads and lines of supply could not possibly accommodate scores of thousands of men. Parallel lines of march undertaken by self-sufficient units that would be able to defend themselves if they stumbled on an enemy along the route of advance were what the situation required.

This was met by the invention of the division, i.e., of an army unit in which the deployment of infantry, cavalry, artillery, and supporting elements like engineers, medical personnel, and communications experts could be coordinated by an appropriate staff and subordinated to a single commander. Numbering up to 12,000, a division could act as an independent fighting unit, complete in itself, or, as the case might be, could combine with others, converging on an enemy or on a strategic point according to plans devised by superior headquarters. French experiments along these lines dated back to the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48), but it was only in 1787–88 that army administration was permanently arranged along divisional lines, and in the field divisional organization did not become standard until 1796.20

With mapping, skilled staff officers, written orders, and a divisional structure, the French were thus in a position by 1788 to surpass older limits on the effective size of field armies. The levée en masse of 1793 would have been useless otherwise. Mere numbers, without effective control on the battlefield, could not have won the victories that in fact came to the revolutionary armies.

Less could be done to relieve limitations of supply. Wagons and boats could carry only so much food and fodder from here to there along existing roads, canals, or rivers. Every improvement in roads and every new canal increased the ease and rapidity with which goods could circulate; and the eighteenth century, particularly its second half, was a time when Europeans invested in roads and canals on a scale far greater than ever before. In Prussia, canal building was consciously connected with strategic planning. Canals constructed during the reign of Frederick the Great, uniting the Oder with the Elbe into a single internal waterway, were intended to assure speedy and secure movement of grain and other supplies into and out of the royal military depots. As Frederick himself remarked to his generals: “The advantage of navigation is, however, never to be neglected, for without this convenience, no army can be abundantly supplied.”21 In France and England direct linkage between communications improvements and military convenience seems not to have prevailed, with the exception of the road building through the Highlands of Scotland which British authorities undertook after the rebellion of 1745. Instead, toll roads and canals were usually built by private entrepreneurs who expected to make a profit from their investments. To be sure, state control and direction was far more pervasive on the Continent than in Great Britain;22 but even when relatively short-term economic returns were what governed private as well as official action, transport improvements always had the further effect of facilitating military supply. Without such improvements, and without technical advances in road building which made possible relatively cheap construction of roads that were passable for wheeled vehicles even in wet and rainy weather,23 the scale of armed enterprise the French revolutionaries inaugurated would have been impossible.

The armies of the French Republic were also heirs of tactical and technical advances that had been worked out in the French army after 1763. Professional pride had been badly stung by the failures and defeats of the Seven Years War. Resistance to innovation was diminished by a pervasive sense that something had to be done to regain the lead France had once enjoyed over Prussia on land and over Great Britain on the seas. But reforms inaugurated by one minister of war created a party of aggrieved officers who sought redress each time a new minister took office. Since no one could well defend a status quo which had led to failure in the Seven Years War, the rival parties instead espoused rival reforms, thus generating heated debate about tactics and army administration.

Far-reaching changes occurred rather rapidly under these circumstances. Recruitment ceased to be a responsibility of captains; instead, the king’s recruiters enlisted soldiers for fixed terms of service with fixed pay and perquisites. Purchase of commissions was phased out; and the rules for promotion were made public and uniform. Regiments were made to conform to identical tables of organization; and, as we saw, the army was reorganized into divisions. Principles of bureaucratic rationality, in other words, came to assert their dominion over more and more aspects of French military administration, even though opposition to such a transformation did not disappear.24

Rival tactical systems were put to the test of field maneuvers in 1778, and even though the partisans of each system disagreed about what had been proved, by degrees enough consensus was achieved to permit the French ministry of war to issue a new and more flexible tactical manual in 1791. It remained standard throughout the revolutionary wars. The new regulations authorized column, line, and skirmishers on the battlefield, according to circumstance and the judgment of the commander. Other European armies had mostly gone over to Prussian tactics after Frederick the Great’s brilliant victories in the Seven Years War.25 As a result, the French revolutionary infantry was able to move about on the battlefield faster and more freely than armies adhering to the rigid battle line favored by Frederick II, and could even operate effectively in rough and broken terrain.

Linear tactics required open fields in which to deploy; and when variegated cropping began to dictate enclosure, the landscape of western Europe became increasingly inhospitable to the old tactics. Too many fences, hedgerows, and ditches got in the way to permit a battle line two or three miles in length to form, much less to move. The French field exercises of 1778 were held in Normandy, in a region where hedgerows and open fields met and mingled. French experience thus took account of this transformation of west European landscapes, whereas further east, around Berlin or Moscow, open fields remained well suited to the old tactics.

Skirmishing had first attained prominence in European warfare thanks to the Austrian army. Maria Theresa incorporated the militia that had long guarded the Turkish border against local raiding parties into her field army during the War of the Austrian Succession. These wild “Croats,” when deployed irregularly ahead of the line of battle, proved very formidable, harassing the enemy rear, interfering with supply convoys, and disturbing deployment of the enemy line with sporadic sharpshooting before regular battle had been joined. Other armies soon began to create “light infantry” of their own to perform similar roles. French tactical improvements between 1763 and 1791 therefore drew freely on the experience of other European armies.26

Sometimes French innovations failed and were swiftly abandoned. This was the fate of an experiment with breech-loading muskets made in 1768.27 After designers gave up this radical idea, a slightly modified muzzle-loader was declared standard in 1777 and remained unaltered until 1816. An old-fashioned design did not prevent upgrading of manufacture, however. Official inspectors began to insist on greater standardization of parts, with the result, presumably, that French muskets became more durable and accurate.28

Far more spectacular and important changes proved feasible in artillery design. Classification of cannon according to the weight of shot they could fire had been systematized in the age of Charles V in all European countries. Early in the eighteenth century, Jean-Florent de Vallière (1667–1759) reduced the number of different calibers in use in the French service. But this sort of standardization remained only approximate as long as each gun had to be cast in a unique and individual mold. It was well-nigh impossible to align the core of the mold accurately with the exterior, since at the time of casting the rush of hot metal almost always pushed the imperfectly centered and weakly supported core slightly out of position. Consequently, the chamber and barrel of the gun, which took its shape from the mold’s core, usually were not perfectly parallel to the exterior of the piece; and lesser irregularities in interior dimensions were taken for granted. Cannon, as cast, were too heavy to keep up with marching troops and so seldom appeared on the battlefield. Their main use was to defend and attack fortresses, and on shipboard.

This situation was transformed by a Swiss engineer and gunfounder named Jean Maritz (1680–1743), who entered French employ at Lyons in 1734. He saw that it might be possible to achieve far more accurate and uniform results by casting cannon as a solid piece of metal and then boring the barrel out afterwards. It took Maritz time to develop a boring machine larger, more stable, and much more powerful than any previously known; and efforts to keep the new method secret, though not effective for long, did suffice to obscure the record of exactly when and how well he succeeded. By the 1750s, however, his son and successor, also named Jean Maritz (1711–90), had perfected the necessary machinery. In 1755 he became inspector general of gunfoundries and forges with the mission of installing his cannon-boring machines in all the royal arsenals of France.29 Other European states soon became interested, and by the 1760s the new technique had been introduced as far afield as Russia.30 A similar machine was set up in Great Britain by John Wilkinson in 1774.31

The advantages of a straight and uniform bore were enormous. Consistently true bores meant that gunners did not have to learn the vagaries of each individual weapon, and could expect to hit their target time and again. Accurately centered bores also made for safer guns since the gunmetal was of the same strength and thickness on every side of the explosion. Most important of all, guns could be made lighter and more maneuverable without losing power. These advantages arose mainly from the fact that a bored-out barrel allowed a far closer fit between cannonball and gun tube than had been considered safe hitherto, when minor irregularities in the interior walls of individual cannon, arising from variation in each mold, had required a generous space (“windage”) between shot and barrel to avoid disastrous jamming. By reducing windage, a smaller powder charge could be made to accelerate a shot more rapidly than when more of the expanding gases had been free to escape around the projectile. Smaller amounts of gunpowder could thus accomplish equivalent work even within a shortened gun barrel; and a smaller charge in turn made it safe to reduce the thickness of metal around the chamber where the explosion took place. Shortened barrels and thinner walls meant lighter guns, easier to move and quicker to return to firing position after recoil. Everything hinged on the accuracy of manufacture, and on systematic testing of sample weapons to find out how short the barrel and how thin the gun walls could safely be made and still achieve the desired velocity and missile throw weight.

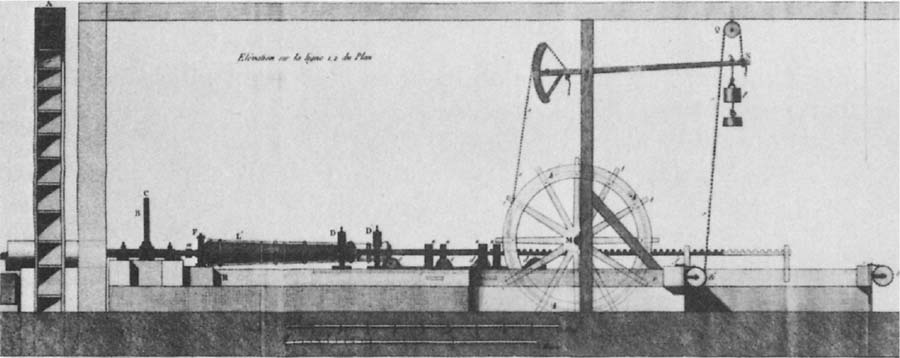

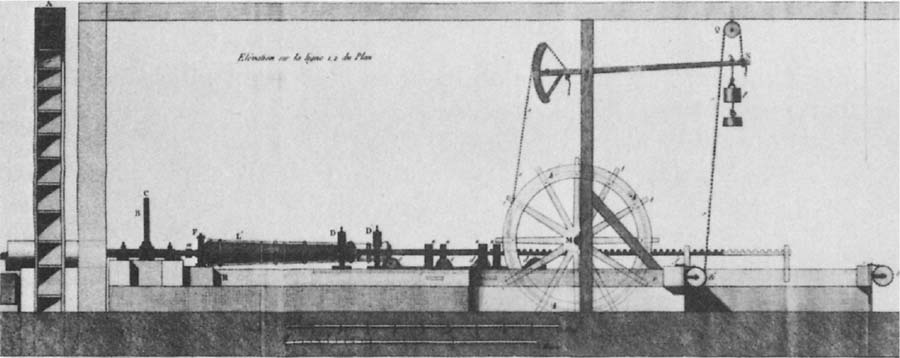

This diagram shows how to bore out a cannon with machinery similar to the device invented by Jean Maritz. The secret of success lay in making the whole cannon revolve against the cutting edge, which was made to advance by weights, gears, and cogs that kept a steady pressure at the cutting face. This arrangement made it possible to hold the cutting head steady, while the cannon’s bulk imparted enough inertia to the spin to prevent wobbling that might otherwise spoil the precision of the bore.

Gaspard Monge, Description de l’art de fabriquer les canons, Imprimée par Ordre du Comité de Salut Public, Paris, An 2 de la République française, pl. XXXXI.

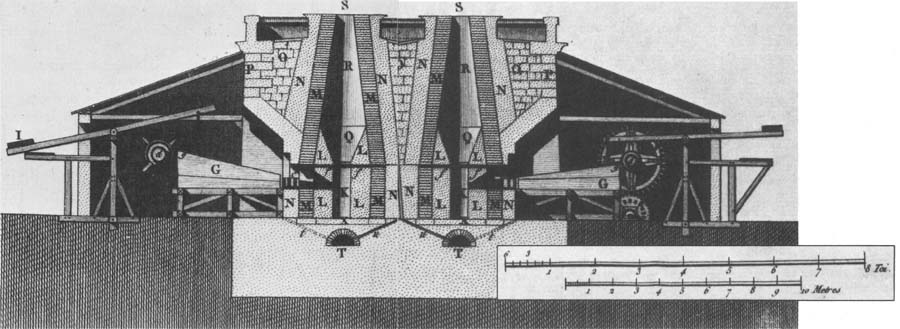

Blast Furnace Design

This diagram of blast furnaces at the French naval gunfoundry at Ruelle shows the capital plant that began to transform the ferrous metallurgical industries of Britain and France towards the end of the eighteenth century. These twin furnaces were ten meters high and could melt enough iron to cast several cannon at once. Note the power-driven bellows which intensified the fire by supplying extra oxygen to the flame.

Ibid., pl. II.

Tests of this sort were carried through by French artillerists under the direction of Jean Baptiste Vacquette de Gribeauval between 1763 and 1767. Gribeauval also presided over similarly systematic efforts to redesign all the associated elements needed for field artillery: limbers, ammunition wagons, horse harnesses, gunsights, and the like. His idea was simple and radical: to apply reason and experiment to the task of creating a new weapons system. He succeeded in creating a powerful field artillery, able to keep up with marching infantry and capable, therefore, of playing a major role in battle.

Careful attention to detail magnified the basic improvement. Thus, for example, Gribeauval introduced a screw device for adjusting gun elevation precisely, and a new sight with an adjustable hairline made it possible to estimate accurately where a shot would hit before the gun was fired. On top of that, by combining shot and powder into a single package, rate of fire approximately doubled what had been possible when powder and shot had to be separately thrust down the cannon’s throat. Finally, Gribeauval developed different kinds of shot—solid, shell, and canister—for different targets, thus assuring the guns’ versatility.32

Sample models of Gribeauval’s new artillery became available as early as 1765, but the new designs were not finally approved until 1776, owing to the quarrels and controversies which so distracted the French army in these years. Even after the new guns had been approved, manufacture to the new standards of precision was difficult, and opposition within the army to Gribeauval’s artillery was not completely stilled until the divisional reorganization was decided on in 1788. Hence, new mobile field artillery was not in hand until the very eve of the Revolution. Gribeauval’s guns remained standard throughout the Napoleonic wars and were phased out only in 1829. They were an important element in French victories from the Cannonade of Valmy (1792) onwards, for Gribeauval created a truly mobile field artillery, capable of reaching battlefields almost as readily as marching infantry could do and able to bombard targets at a distance of up to 1,100 yards or so.

A second aspect of Gribeauval’s reforms was organizational. Transport of the new field artillery became the duty of the soldiers who fired them instead of remaining the responsibility of civilian contractors as had previously been customary. Drill on the guns, practicing motions needed to unlimber, position, aim, and fire, attained the routine precision that had long been characteristic of small-arms drill. Gribeauval also set up schools for artillery officers to teach theoretical aspects of gunnery along with how to fit the new guns to approved infantry and cavalry tactics. Rational management and design was thus extended from materiel to the human beings needed to man the redesigned weapons. As a result, the medieval craft guild heritage disappeared entirely from the French service, and artillery took its place in the new divisional structure side by side with infantry and cavalry as part of a reorganized and redesigned command structure embodying the results of rational thought and systematic testing.

Gribeauval’s career is interesting not only in itself and for its contribution to French military successes after 1792, but also because what he and his associates did marked an important horizon in European management of armed force. These eighteenth-century French artillerists set out to create a weapon with performance characteristics previously unattainable, but whose use in battle could clearly be foreseen. With Gribeauval and his circle, in short, planned invention, organized and supported by public authority, becomes an unmistakable reality. Perhaps the rapid development of catapults in the Hellenistic age33 and the remarkable design improvements that craftsmen made in cannon during the fifteenth century, when iron projectiles were first introduced, may have had something of the same character. But information about these earlier cases is scant, and the artificers who made catapults for Hellenistic rulers, as well as the bellmakers who used their art to cast guns for Charles the Bold and Louis XI may or may not have conceived in advance what better designed catapults and guns could do. The matter is simply not on record. But in the case of the French artillerists, it is perfectly clear that a reform party came into being around the person of Gribeauval; that leaders of this group had clearly in mind what could be achieved by taking advantage of accurately bored gun barrels and saw their technical reforms as part of a more general rationalization of army organization and training.

The traditions of European army life, emphasizing hierarchy, obedience, and personal bravery, fitted awkwardly with Gribeauval’s kind of cerebral calculation and experiment; and when technical experts sought to apply the same methods to general questions about how an army should be deployed and set out to raise the status of gunners to something like equality with infantry and cavalry, resistance was naturally intense. Sharp fluctuations of policy with respect to Gribeauval’s reforms reflected this strain between an assertive rationalism and the cult of prowess (and other vested interests) within the army and within the French government as a whole.

A weapon that could be used to kill soldiers impersonally and at a distance of more than half a mile offended deep-seated notions of how a fighting man ought to behave. Gunners attacking infantry at long range were safe from direct retaliation: risk ceased to be symmetrical in such a situation, and that seemed unjust. Skill of an obscure, mathematical, and technological kind threatened to make old-fashioned courage and muscular prowess useless. The definition of what it meant to be a soldier was called into question by such a transformation, incipient and partial though it remained in the eighteenth century as compared to what was to come in the nineteenth and twentieth. The introduction of small arms in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries had already diminished the role of direct hand-to-hand combat and muscular encounter in battle; only the cavalry, charging home with cold steel, preserved, under eighteenth-century conditions, the primitive reality of combat. This reinforced the prestige cavalry inherited in European armies from the days of knighthood. Nobles and conservatively minded soldiers in general clung energetically to the old-fashioned, muscular definition of battle. Artillerymen with their cold-blooded mathematics seemed subversive of all that made a soldier’s life heroic, admirable, worthy.

This sort of heartfelt emotion seldom found clear articulation. It tapped irrational levels of human personality, and those who felt keenly the wrongness of long-range artillery were not usually gifted in the use of words. But newfangled technicians and their angriest opponents could agree on one thing: sale of commissions to the highest bidder allowed the wrong kind of men to become officers. To exclude unqualified parvenus and keep commissions in military families, the French Ministry of War accordingly decreed in 1781 that to qualify for infantry and cavalry commissions candidates must prove four quarterings of nobility. Ambitious noncoms were the only constituency within the army displeased by this act, since the artillery remained, as before, open to commoners with suitable mathematical skills.34

Frederick the Great set the style for this kind of aristocratic reaction by systematically excluding commoners from the Prussian officer corps after 1763. He did so because he distrusted the calculating spirit that he associated with men of bourgeois background—exactly the traits that dominated and inspired Gribeauval and his circle. Frederick, indeed, was dismayed by the new developments in artillery, realizing that Prussia was poorly equipped to compete with Russia’s great iron industry, or even with Austria and France, in a technological arms race. He reacted by downplaying artillery while emphasizing discipline and “honor,” i.e., the traits that had always made Prussian officers and men ready to sacrifice their lives on behalf of the state. Frederick and his successor thus chose to rely on old-fashioned military virtues and deliberately turned their backs on rational experimentation and technical reform of the sort Gribeauval carried through. In 1806 the cost of this conservative policy became evident. At the battle of Jena, Prussian valor, obedience, and honor proved an inadequate counterweight to the new scale of war the French had meanwhile perfected, thanks, in large part, to the often reluctant hospitality French army commanders showed to the rational and experimental approach to their profession.35

Command technology, seeking deliberately to create a new weapons system surpassing existing capabilities, has become familiar in the twentieth century. It was profoundly new in the eighteenth; and the French artillerymen who responded so successfully to Gribeauval’s lead deserve to be heralded as pioneers of today’s technological arms race. Yet it is easy to exaggerate. Systematic and successful though the effort was, it remained isolated and exceptional. As had happened after 1690, when the flintlock musket and bayonet achieved an enduring “classic” form, field artillery design reached a plateau with Gribeauval’s achievement. The field guns of other European armies lagged behind the French in varying degrees when the revolutionary wars began; by the time peace returned in 1815 all the great powers had come more or less abreast of the weapons the French began with. No further fundamental change took place until breech-loaders came in after 1850.

Clearly, a sharp stimulus was required before the routines of military life could be sufficiently shaken up to allow the sort of change that French artillery achieved between 1763 and 1789. Details of Gribeauval’s personal career probably mattered, for he was sent to study Prussian artillery methods in 1752 and then, in 1756, transferred to the Austrian service where he played a conspicuously successful role in the Seven Years War by first capturing a Silesian strong point with siege guns and then defending another town against Prussian attack for much longer than anyone thought possible. When he returned to France in 1762, therefore, Gribeauval was thoroughly familiar with improvements the Austrians had already made in their artillery. A vision of the possible—of how a more systematic approach could create a new kind of weapon and profoundly alter conditions on the battlefield—presumably took root in Gribeauval’s mind as a result of his encounter with foreign practice.

But the will to do something drastic clearly depended also on the widespread sense among Frenchmen that something was wrong with the way their government in general and the army and navy in particular had been managed. When the vision of the possible thus united with a widely diffused dissatisfaction with existing arrangements, the kind of breakthrough that Gribeauval’s reform constituted became possible. But such circumstances were unusual. The ordinary practice and routine of European military establishments were not yet systematically disturbed by research and development teams of the kind Gribeauval headed. Command technology, in short, remained exceptional, and but little noted or understood outside of a small circle of professional artillery officers. Yet as a “cloud no bigger than a man’s hand” and a sign of things to come, the remarkable success achieved by Lieutenant General Gribeauval and his artillery designers deserves more attention than it has usually been accorded.36

Nevertheless, though the development of an efficient field artillery was certainly significant for the future of European warfare, it remained true that siege guns, fortress guns, and naval guns consumed far more metal and were numerically far more important than newfangled and, to begin with, quite untested field artillery.37 Yet here, too, the French began to probe hitherto established limits on the eve of the Revolution. The problem, from a French point of view, was that new and superior techniques for smelting iron developed in Great Britain during the 1780s. The key change was Henry Cort’s invention in 1783 of what was known as “puddling.” This referred to the possibility of melting pig iron inside a coke-fired reverberatory furnace that reflected heat from its roof in such a way that the iron need not be in direct contact with the fuel at the bottom. By stirring the molten metal while it was in the furnace, various contaminants could be vaporized and thus removed from the iron. Then when the metal had been allowed to cool to red-hot viscosity, British ironmasters discovered that they could pass the metal through heavy rollers and thereby extrude additional impurities by mechanical force while shaping the metal to any desired thickness by adjusting the space between rollers. The end product was cheaply made, conveniently shaped wrought iron that was suitable for use in cannon, as well as for innumerable other purposes. But it took some twenty years of trial and error (i.e., until the first decade of the nineteenth century) to overcome all the difficulties in designing suitable furnaces and getting rid of damaging contaminants.38

Long before then, French entrepreneurs and officials recognized the potential value of the new method of iron manufacture for armaments production. By using coke, a relatively cheap and potentially abundant fuel, costs could be sharply reduced; by using rollers, relatively vast amounts of iron could be wrought without the expensive hammering which had previously been necessary. Accordingly, French promoters hatched a grand scheme for building a smelting plant at Le Creusot in eastern France, where the latest British technology for coke firing would be used. This was to be linked by canal and navigable rivers to a naval gunfoundry at Indret, an island at the mouth of the Loire. In this way, French planners hoped that the French navy could secure large numbers of cheap guns for its ships and for harbor defense. An English technician and entrepreneur, William Wilkinson, joined forces with a French captain of industry, Baron François Ignace de Wendel, and Parisian financiers to promote this scheme. Interest-free loans from the French government helped with initial expenses and Louis XVI personally subscribed to 333 of the 4,000 shares. With this august backing, Le Creusot began production in 1785, but met with severe and persistent technical difficulties of the same sort that were plaguing British ironmasters in these years. The grandiose enterprise in fact went bankrupt in 1787–88, and after years of unsatisfactory production the scheme was abandoned in 1807 because the poor quality of iron from Le Creusot produced too many defective cannon.39

Despite its ultimate failure, this grand plan clearly adumbrated nationwide mobilization for large-scale arms production of a kind that became important only in the twentieth century. Such plans were not entirely without precedent. In the seventeenth century, Colbert imported considerable numbers of Liègeois arms makers to staff royal arsenals in France.40 Even earlier than this, import of technology from abroad, and its application on a grand scale to armaments production, had helped the Russian state outstrip its rivals and neighbors. Thus, the establishment of a Dutch-managed arms plant at Tula in 1632 was followed by Peter the Great’s successful efforts to build up ferrous metallurgy in the Urals.41 Moreover, the transfer of Flemish metallurgical technique to Sweden in the early part of the seventeenth century had a very similar character,42 and Prussian efforts to establish an arms industry in the neighborhood of Berlin, by importing skilled personnel from Liège (1772), though on a relatively modest scale,43 also involved strategic planning like the French scheme of the 1780s.

What made the Le Creusot–Indret plan different was that Baron de Wendel and his associates were exploring the potentialities of new, large-scale industrial methods for the manufacture of armaments. In this they anticipated developments of the second half of the nineteenth century, when private entrepreneurs successfully sold big guns and other weapons to the governments of Europe and the world. De Wendel’s connections with the government were rather more intimate than the later relations between private armaments makers and governments in the nineteenth century. Close collaboration between public authority and private entrepreneurs for arms manufacture had Colbertian roots in France; on a mass industrial scale, however, of the sort attempted by Baron de Wendel, such collaboration was lastingly achieved only after 1885.

The fact was that in the 1780s, if French entrepreneurs were to catch up with British advances in ferrous metallurgy, the navy offered the only readily apparent consumer for a vastly increased scale of production. To transplant the new technology, with its expensive capital installations, to French soil required an assured outlet for the product. Otherwise no sensible investor would even consider the idea, since internal tariffs and the high cost of overland transport had inhibited the development of a national market in France. In Britain, by contrast, a nationwide civilian market had already appeared by the 1780s, offering the new ironmasters of Wales, and soon also of Scotland, a variety of outlets for their goods. Yet even in Great Britain, Henry Cort justified his patent for the puddling process by claiming that he could thereby lower the price of guns for the navy;44 and during the critical years of take-off, between 1794 and 1805, the British government purchased about a fifth of the ironmasters’ product, nearly all of which was used for armaments.45

The grandiose character and ultimate failure of the Le Creusot–Indret plan for supplying the French navy with cheap and numerous heavy guns was entirely characteristic of the way things went in the French navy during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The difficulty was that the army came first. Only sporadically did French policy put major effort into building up a great navy. Colbert had done so between 1662 and 1683 in order to defeat the Dutch. He succeeded so well that even when England joined Holland against the French in 1689, the French navy initially proved itself superior to the combined Dutch and English fleets. But French naval resources were stretched close to their limits when the war began. It therefore proved impossible to increase the size of the navy very much in the course of hostilities, whereas in England both the means and will to outbuild the French were present. After 1692, when fifteen French ships of the line were destroyed at the Battle of La Hogue, English-Dutch naval superiority to the French became unmistakable.

Two years later the French turned to a cheaper (for the government) form of naval war, i.e., to privateering. This was a fateful decision. The English, in effect, went the opposite way, inventing an efficient centralized credit mechanism for financing war by founding the Bank of England in 1694. At exactly the same time, under the pressure of a financial crisis provoked by bad harvests, the French government assigned the financing of naval enterprise to private investors, i.e., to privateers. Continued state expenditure on the navy had come to seem impossibly costly. The result was to assure Great Britain of relatively easy naval superiority throughout the early eighteenth century. This allowed Great Britain to come close to sweeping French commerce from the seas during the Seven Years War. English victories, in turn, drastically reduced the resources available within France to finance privateering, whereas within England commercial interests gained such a strategic position in Parliament that resistance to naval appropriations was effectually blunted.46

After the disasters of the Seven Years War, French ministers drew the conclusion that they needed a navy as good as or better than the British, in order to reverse the verdict of 1763. But French naval architects were not so fortunate as Gribeauval, inasmuch as no important technical improvements came within their reach that might have permitted them to leave the British behind. Bored-out cannon improved naval gunfire too, but the British kept pace with this change; and the difficulties of aiming heavy cannon from a pitching ship made the refinements in aiming, which were so important for field artillery, ineffective on shipboard. French warships were nearly always better built than their British counterparts, but in the last decades of the eighteenth century, the Royal Navy pioneered two important technical advances—copper sheathing for ships’ bottoms, and the use of short-barreled, large caliber guns, known as carronades.47

Throughout the century, the shape and strength of oak timbers set a definite limit to the size of warships. Improvements of design that did prove feasible, such as the use of a steering wheel to give mechanical advantage to the steersman, the use of reef points to adjust the area of canvas to variations in the strength of the wind, and the use of copper sheathing to prevent fouling the bottom, although they cumulatively did much to improve the maneuverability of heavy warships, never established a clear break with older performance levels of the kind Gribeauval’s field guns enjoyed.48

Numbers, therefore, were what mattered, and between 1763 and 1778 the French succeeded in building enough new ships of the line to be able to confront Great Britain on almost even terms at sea. Indeed, when war broke out again and Spain allied herself with France, the combined French and Spanish fleets briefly dominated the English channel. Later in the war, however, the British recovered their traditional naval preponderance so that peace, when it came in 1783, secured American independence without overthrowing Britain’s naval primacy.

Two factors continually hampered French naval efforts. One was the way in which land operations took precedence in French strategic planning. Against England, as earlier against Holland, the master scheme was to mount an invasion by land forces. The navy was therefore expected to escort the invading force either directly across the Channel or to the coast of Ireland or Scotland rather than to act independently and on its own. Repeatedly, invasion plans were prepared, only to break down because of difficulties of coordination. The fact was that in the eighteenth century staff work and technology were inadequate to sustain a successful landing on a defended coast, as the failure of several British efforts to land troops on the French coast amply demonstrated. But when overambitious plans for invasion of England or Ireland aborted, French policy makers were almost driven to conclude that money spent on the navy was a waste and should be cut back drastically.49 Such a policy was doubly tempting when privateering constituted a cheap and popular alternative way of harassing enemy commerce at no cost to the government whatever.