Between Kilkenny and Waterford

If you’re driving from Dublin (on Ireland’s east coast) to Dingle (on Ireland’s west coast), the best two stops to break the long journey across the Irish interior are Kilkenny, Ireland’s finest medieval town; and the Rock of Cashel, a thought-provoking early Christian site crowning the Plain of Tipperary.

Counties Kilkenny and Tipperary (“Tipp” to locals) are blood rivals on the hurling field, with the lion’s share of the GAA national championships split between them. Watch for sporting kids carrying their hurlies (ash-wood sticks with broad, flat ends) to or from school. These two counties also boast some of the finest agricultural land on this rocky and boggy island. Farm tractors rumble the back roads where it’s not a long way to Tipperary.

With a few extra days, consider additional worthwhile destinations along the southeast coast, such as Waterford and County Wexford (described in the next chapter). Folks with more time can continue on the scenic southern coastal route west via Cobh, Kinsale, Kenmare, and the Ring of Kerry (all covered in later chapters).

Ireland’s loveliest inland city—winner of Ireland’s “Tidy Town” award in 2014—Kilkenny gives you a feel for salt-of-the-earth Ireland. Its castle and cathedral stand like historic bookends on a higgledy-piggledy High Street of colorful shops and medieval facades. It’s nicknamed the “Marble City” for its nearby quarry (actually black limestone, not marble), and you can see white seashells fossilized within the black stone steps around town. While a small town today (around 25,000 residents), Kilkenny has a big history. It was even the capital of Ireland for a short spell in the turbulent 1640s. And actor George Clooney traces his roots to Kilkenny.

Kilkenny is a good overnight for drivers wanting to break the journey from Dublin to Dingle (necessary if you want to spend time at Powerscourt and Glendalough on the way to the Rock of Cashel). A night in Kilkenny comes with plenty of traditional folk music in its pubs.

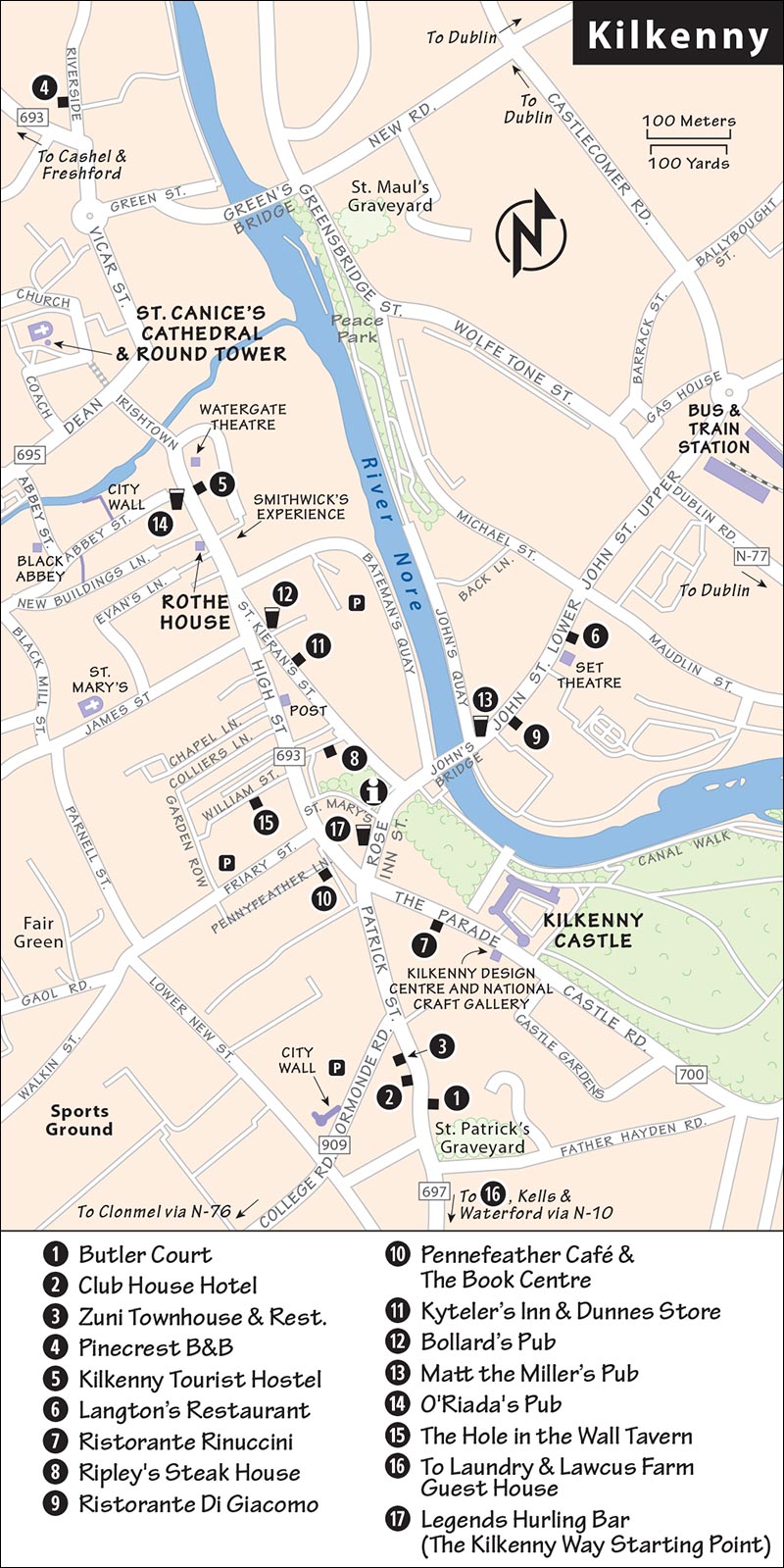

The TI is a block off the bridge in the 16th-century Shee Alms poorhouse (Mon-Sat 9:00-17:30, Sun 11:00-17:00, shorter hours and closed Sun off-season; Rose Inn Street, tel. 056/775-1500).

The train/bus station is four blocks from John’s Bridge, which marks the center of town.

If you’re arriving by car, the Market Yard Car Park behind Kyteler’s Inn is handy for a few hours (€1.30/hour, daily 8:00-18:00, entry off Bateman’s Quay). The multistory parking garage on Ormonde Street is the best long-term bet (€1.50/hour, or get the 3-day pass for €10 if staying overnight—it allows you to come and go; open 7:00-23:00, Fri-Sat until 24:00). If parking overnight, wait until you depart to pay since some hotels will validate parking. Otherwise, you can use the pay-and-display meters on the street (€1.50/hour, enforced Mon-Sat 8:00-19:00).

Exchange Rate: €1 = about $1.10

Country Calling Code: 353 (see here for dialing instructions)

Market: The square in front of Kilkenny Castle hosts a friendly produce, cheese, and crafts market on Thursdays (8:00-14:30).

Post Office: It’s on High Street (Mon-Fri 9:00-17:30, Sat 9:00-13:00, closed Sun).

Laundry: The Laundry Basket trumpets its existence in vivid red at 21 Patrick Street at the south end of town (Mon-Fri 9:00-18:00, Sat 10:00-15:00, closed Sun, tel. 056/777-0355).

Bookstore: The Book Centre, with a cheap and cheery café upstairs, is a great place to hang out on a rainy day (Mon-Sat 9:00-18:00, Sun 13:00-17:00, 10 High Street, tel. 056/776-2177).

Bike Rentals: Kilkenny Cycling rents bikes for €15 a day (with a €50 refundable deposit). They provide safety gear, deliver bikes to your hotel on request (€1.50 charge), and have route maps for exploring the pastoral charms of County Kilkenny (office in courtyard through the arches behind the Kilkenny Design Centre, mobile 086-895-4961, www.kilkennycyclingtours.com).

Local guide Pat Tynan and his staff offer hour-long town walks that depart from the TI (€8; mid-March-Oct Mon-Sat at 10:30, 12:15, and 15:00, Sun at 11:15 and 12:30; Nov-mid-March by prior arrangement only; mobile 087-265-1745).

Amanda Pitcairn runs tours focusing on the history of medieval Kilkenny and the daily life of its inhabitants—witchcraft and skullduggery included (€8; check at TI for times or contact Amanda, mobile 087-277-6107, pitcaira@tcd.ie).

At Kilkenny Cycling, Jason Morrissey is the man with the plan for a two-hour “easy-paced” guided tour (€20), which takes in a half-dozen of the town’s best sights, including Kilkenny Castle, Rothe House, and St. Canice’s Cathedral (usually departs at 10:00 and 14:00, also at 19:00 May-Sept). His €20, four-hour unguided “bike-and-hike” tour includes a seven-mile ride to Bennettsbridge (leave bikes there), followed by a pretty hike back along the river. He also offers a €15 medieval mile cycling treasure hunt for history buffs (10 percent discount with 2017 edition of this book, cash only, can arrange for tour to leave from your hotel, see “Bike Rentals,” above, for contact info).

Dominating the town, this castle is a stony reminder that the Anglo-Norman Butler family controlled Kilkenny for 500 years. The castle once had four sides, but Oliver Cromwell’s army knocked down one wall when it took the castle, leaving it as the roughly “U” shape we see today.

Cost and Hours: €8, daily June-Aug 9:00-17:30, slightly shorter hours off-season, tel. 056/770-4100, www.kilkennycastle.ie.

Visiting the Castle: Enter the castle gate, turn right in the courtyard, and head into the base of the turret. Here you’ll find the continuously running 12-minute video explaining how the wooden fort built here by Strongbow in 1172 evolved into a 17th-century château. Then go into the main castle entrance, diagonally across the courtyard from the turret, to buy your entry ticket. You’ll be free to walk through the castle. A pamphlet explains the exhibits, and you can also talk to stewards in the important rooms.

Now restored to its Victorian splendor, the castle’s highlight is the beautiful family-portrait gallery, which puts you face-to-face with the wealthy Butler family ghosts.

Nearby: The Kilkenny Design Centre, across the street from the castle in some grand old stables, is full of local crafts and offers handy cafeteria-style lunches in the food hall (shops open Mon-Sat 10:00-19:00, Sun 10:00-18:00; food hall open daily 8:30-18:30; tel. 056/772-2118, www.kilkennydesign.com).

This is the crown jewel of Kilkenny’s medieval architecture: a well-preserved merchant’s house that expanded around interior courtyards as the prosperous Rothe family grew in the early 1600s.

Cost and Hours: €5.50; April-Oct Mon-Sat 10:30-17:00, Sun 12:00-17:00; Nov-March closes at 16:30 and all day Sun; Parliament Street, tel. 056/772-2893, http://rothehouse.com.

Visiting the Rothe House: Check out the graceful top-floor timberwork supporting the roof, which uses wooden dowels (pegs) instead of nails. The museum, which also serves as the County Kilkenny genealogy center, gives a glimpse of life here in late Elizabethan and early Stuart times. The walled gardens at the far back were a real luxury in their time.

The Rothe family eventually lost the house when Oliver Cromwell banished all Catholic landowners, sending them to live on less desirable land west of the River Shannon. In the late 1800s, the building housed the Gaelic League, devoted to the rejuvenation of Irish culture through preservation of the Irish language and promotion of native Irish sports (such as hurling). One of the future leaders of the 1916 rebellion—Thomas McDonagh, who was executed at Dublin’s Kilmainham Gaol—taught here.

The sport of hurling is historically and culturally important to the Irish. And Kilkenny, which hosts more all-Ireland hurling championships than any other county, is a hurling mecca. The Kilkenny Way tour includes a visit to a hurling pub/museum and the stadium where the Kilkenny Cats play. You’ll learn about the long history and rules of this lightning-fast field game, and also get a chance to play as you figure out how to balance your sliotar—and how to pronounce it.

Cost and Hours: €25 for two-hour tour, includes pub meal; daily at 13:45, reserve ahead in summer; leaves from Legends Hurling Bar, 28 Rose Inn Street, tel. 056/772-1718, www.thekilkennyway.com.

This 13th-century cathedral is early-English Gothic, rich with stained glass, medieval carvings, and floors paved in history. Check out the model of the old walled town in its 1641 heyday, as well as a couple of modest audiovisuals. The 100-foot-tall round tower, built as part of a long-gone pre-Norman church, recalls the need for a watchtower and refuge. The fun ladder-climb to the top affords a grand view of the countryside.

Cost and Hours: Cathedral-€4, tower-€3, combo-ticket-€6; June-Aug Mon-Sat 9:00-18:00, Sun 14:00-18:00; Sept-May slightly shorter hours and closed for lunch; tel. 056/776-1910, www.cashel.anglican.org.

Smithwick’s (pronounced SMITH-icks) reddish ale was born in Kilkenny...and has been my favorite Irish beer since my first visit to Ireland. Older than Guinness (but now owned by the same parent company), Smithwick’s marked its tercentennial (300th anniversary) in 2010. After a corporate shake-up in 2013, the brewery consolidated its operations in Dublin and opened an “Experience” visitors center here on the former brewery grounds.

Tours focus on the historic origins of the tasty ale, first brewed by the monks of St. Francis Abbey (the 14th-century ruins of the abbey lie adjacent to the site). In the days of the monks, beer was a safer and healthier alternative to local water sources that were often contaminated. I’ll drink to that.

Note that—like the Guinness Storehouse in Dublin—this is not a tour of a working brewery. It’s a corporate-sponsored homage to the history of the brewery that once operated here.

Cost and Hours: €13, 10 percent discount if booked online, entry includes a pint at the tour’s end, daily March-Oct 10:00-18:00, Nov-Feb 11:00-16:00, one-hour tours run hourly, last tour at 17:00, tel. 056/778-6377, www.smithwicksexperience.com.

Kilkenny has its fair share of atmospheric pubs. Visitors seeking fun trad music sessions may want to try the first three places listed here. Those seeking friendly conversation in utterly unvarnished Irish splendor should seek out the memorable duo at the end of these listings. A fun pub crawl could link all five of these places with less than 20 minutes of walking (30 minutes crawling).

Bollard’s Pub, an unpretentious landmark at the north end of St. Kieran’s Street, is a good bet for lively traditional music sessions (Tue and Thu-Fri at 21:00) and good pub grub. Or sit out front under the awning and enjoy a pint as Kilkenny’s humanity flows past you. Just down the same street is Kyteler’s Inn, with a stony facade and medieval cellar (music almost nightly in summer at 18:30, 27 St. Kieran’s Street). You can saunter over John’s Bridge to check out the tunes at Matt the Miller’s Pub, with its multilevel, dark-wood interior (around 21:00 most nights, next to bridge on John Street across the river from the castle).

Lacking music but high on character, O’Riada’s is an endangered species—a wonderful, old-fashioned place that your Irish grandfather would recognize and linger in (across from the Watergate Theatre at 25 Parliament Street). Meanwhile, The Hole in the Wall is a tiny, restored Elizabethan tavern (1592) hidden down an alley. Owner Michael Conway, a cardiologist by day and a historian/playwright/actor/barman by night, presides over the speakeasy-like space as a labor of love. His music sessions can be an uninhibited go-for-broke thump-a-thon (he plays bass drum). He also writes and occasionally performs eclectic, history-based “singspiel” shows. Both take place in the larger, but equally ancient, timber-beamed upstairs hall (sporadic hours but always Fri-Sat from 20:00 and sometimes weeknights, call ahead, look for the alley beside Bourkes shop at 17 High Street, tel. 087/807-5650, www.holeinthewall.ie).

The Watergate Theatre houses live plays and other performances in its 300-seat space (€12-25, Parliament Street, tel. 056/776-1674, www.watergatetheatre.com).

The Set Theatre, adjacent to sprawling Langton’s Restaurant, is a fine, modern, 250-seat music venue attracting top-notch Irish acts in an intimate setting (€10-25, John Street, tel. 056/772-1728, www.set.ie).

The first three listings are more central, clustered within a block of each other along Lower Patrick Street. The last two are at the north end of town, but still just a short walk from the action.

$$ Butler Court is Kilkenny’s best lodging value. Ever-helpful Yvonne and John offer 10 modern, spacious rooms behind the beige, flag-draped archway. Bo the dog quietly patrols the courtyard (wheelchair-accessible, continental breakfast in room, will validate parking in nearby multistory garage on Ormonde Street for length of your stay, 14 Lower Patrick Street, tel. 056/776-1178, www.butlercourt.com, info@butlercourt.com).

$$ Club House Hotel, originally a gentlemen’s sporting club, comes with fading Georgian elegance; a musty, creaking ambience; a palatial, well-antlered breakfast room; and 35 comfy bedrooms (secure parking, Lower Patrick Street, tel. 056/772-1994, www.clubhousehotel.com, info@clubhousehotel.com).

$$ Zuni Townhouse, above a fashionable restaurant, has 13 boutique-chic rooms sporting colorfully angular furnishings. Ask about two-night weekend breaks and midweek specials that include a four-course dinner (parking in back, 26 Lower Patrick Street, tel. 056/772-3999, www.zuni.ie, info@zuni.ie).

$ Pinecrest B&B has four nice rooms in a modern house on a quiet homey street, just a 10-minute walk from the center of town (cash only, parking, Bishop Meadows, just off Freshford Road about 100 yards north of the roundabout to the Green’s Bridge, tel. 056/776-3567, mobile 087-934-4579, pinecrestbnb@eircom.net, friendly Helen Heffernan).

¢ Kilkenny Tourist Hostel, filling a fine Georgian townhouse with ramshackle fellowship in the town center, offers 60 cheap beds, a friendly family room, a well-equipped members’ kitchen, and a wealth of local information (private rooms available, cash only, 2 blocks from cathedral at 35 Parliament Street, tel. 056/776-3541, www.kilkennyhostel.ie, info@kilkennyhostel.ie).

$$ Lawcus Farm Guest House is a quirky, seductive confection of rural comfort 10 miles south of Kilkenny between Kells Priory and the village of Stoneyford. Hosts Mark and Ann Marie have crafted a tasteful vibe from a passion for recycled materials and environmental sensitivity. Mark, an inventive craftsman, built the house from scratch. A menagerie of friendly pets and farm animals shares the 20-acre property straddling the Kings River. Ask about the tiny secluded tree house (family rooms, cash only, parking, mobile 086-603-1667 or 087-291-1056, www.lawcusfarmguesthouse.com, lawcusfarm@hotmail.com). To reach the farm, go south out of Kilkenny on N-10, which becomes R-713 after crossing over the M-9 motorway. Just as you enter the village of Stoneyford, turn right onto L-1023. Go 500 yards down that lane and watch for a brown sign directing you to turn right into a 100-yard-long gravel driveway.

(See “Kilkenny” map, here.)

$$$ Langton’s is every local’s first choice, serving high-quality Irish dishes under a labyrinthine, multichambered, Tiffany-skylight expanse (daily 12:00-22:00, 69 John Street, tel. 056/776-5133).

$$$$ Ristorante Rinuccini serves classy, romantic, candlelit Italian meals (daily 12:00-14:30 & 17:00-22:00, reservations smart, 1 The Parade, tel. 056/776-1575, www.rinuccini.com).

$$$ Ripley’s Steak House delights carnivores (believe it or not) with choice cuts of locally raised beef. Try the flaky-crusted, veggie-stuffed steak hot pot (daily 13:00-21:00, Oct-May closed Mon-Tue, hidden down Butterslip Lane, tel. 056/777-0699).

$$ Ristorante Di Giacomo is the friendly, informal Italian option in town, presided over by charming Giacomo (daily 12:00-22:30, 84 John Street, tel. 056/777-0907).

$$$$ Zuni is a stylish splurge, offering international cuisine (daily 12:30-17:00 & 18:00-20:45, weekend reservations a good idea, 26 Lower Patrick Street, tel. 056/772-3999, http://zuni.ie).

$ Pennefeather Café, above the Kilkenny Book Centre, is good for a quick, cheap, light lunch (Mon-Sat 9:00-17:30, closed Sun, 10 High Street, tel. 056/776-4063).

$$$ Kyteler’s Inn serves decent pub grub in a timber-and-stone atmosphere with a heated and covered beer garden out back. Visit their fun 14th-century cellar and ask about their witch. Watch your head or risk leaving some of your DNA embedded in the low stone arches (Mon-Sat 12:00-21:00, Sun until 20:00, 27 St. Kieran’s Street, tel. 056/772-1064).

Grocery: Dunnes Stores has an ample selection of supplies for a grassy picnic (a few doors down from Kyteler’s Inn on St. Kieran’s Street, Mon-Sat 8:00-22:00, Sun 10:00-20:00).

From Kilkenny by Train to: Dublin (6/day, 1.5 hours), Waterford (6/day, 45 minutes). For details, see www.irishrail.ie.

By Bus to: Dublin (8/day, 2.5 hours), Waterford (2/day, 1 hour), Tralee (3/day, 5.5 hours, change in Cork), Galway (3/day, 5 hours). For details, see www.buseireann.ie.

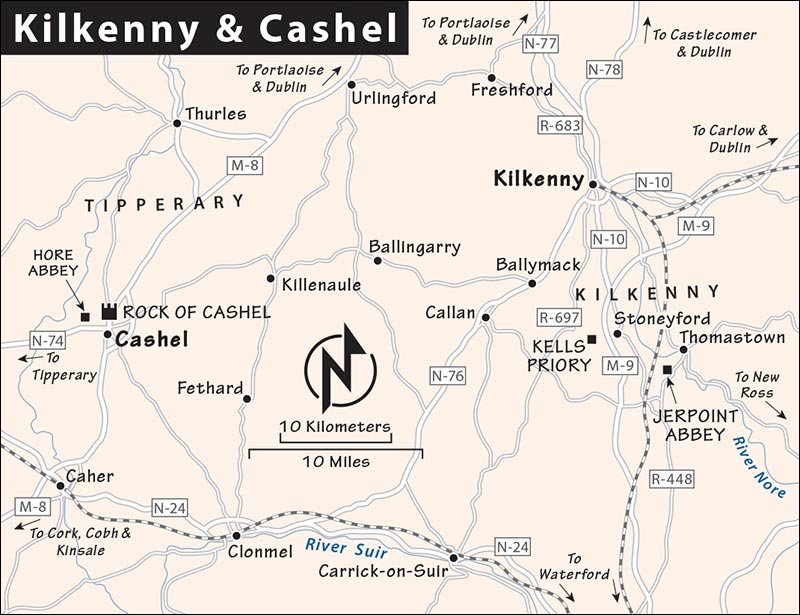

The M-9 motorway links Kilkenny and Waterford with an hour’s drive. But drivers in no rush can savor the journey by spending a couple of enjoyable backroad hours taking in two pastoral sights: Jerpoint Abbey and Kells Priory. (You can also stitch these places into a more leisurely itinerary for an easy, triangular day trip beginning and ending in Kilkenny—about 28 miles/45 km total.) The rural roads come with old stone bridges spanning placid rivers that weave among tiny villages and abandoned mills. Bring an Ordnance Survey atlas (available at most bookstores) to navigate. It’s easier to visit Jerpoint Abbey first. There are no guided tours at Kells Priory; ask at the abbey for directions and pointers.

Evocative abbey ruins dot the Irish landscape, but few are as well-presented as Jerpoint (founded in 1180). Its claim to fame is fine stone carvings on the sides of tombs and on the columns of the cloister arcade. If you visit only one abbey in Ireland, make sure it’s this one.

Without the excellent guided tours, the site is a cold, rigid ruin. But once in the hands of the unusually well-versed hosts, the place truly comes alive with insights into the monastic culture that imprinted Ireland 850 years ago.

Cost and Hours: €5; March-Oct daily 9:00-17:30; off-season Mon-Fri 9:30-16:00, closed Sat-Sun except in Nov; tel. 056/772-4623.

Getting There: It’s located about 11 miles (17 km) south of Kilkenny or 2 miles (3 km) south of Thomastown, beside R-700.

Visiting the Abbey: The Cistercian monks, who came to Ireland from France in the 12th century, were devoted reformers bent on following the strict rules of St. Benedict. Their holy mission was to bring the wild Irish Christian church (which had evolved, unsupervised, for centuries on the European fringe) back in line with Rome. With an uncompromising my-way-or-the-hell-way attitude, they steamrolled their belief system across the island and stamped the landscape with a network of identical, sprawling monasteries. The preexisting form of Celtic Christianity that had thrived in the Dark Ages was no match for the organization and determination of the Cistercians.

For the next 350 years, these new monasteries held the moral high ground and were the dominant local religious authority. Monks got closer to God by immersing themselves in the hardships of manual field work, building water mills, tending kilns, and advancing the craft of metallurgy. The wealth created by this turbo-charged industriousness caused communities to form around these magnetic monastic cores.

What eventually did them in? King Henry VIII’s marriage problems, his subsequent creation of the (Protestant) Church of England, and his eventual dissolution of the (Catholic) monasteries. Walls were knocked down and roofs were torn off monasteries such as Jerpoint to make them uninhabitable. Their lands were forfeited to the king, who sold them off and enriched his treasury. It’s good to be king.

Locals claim that the massive religious complex of Kells Priory (more than 3 acres) is the largest monastic site in Europe. It’s an isolated, deserted ruin that begs a curious wander, a nimble shutter finger on your camera, and alert side-stepping of sheep droppings.

Don’t confuse this Kells with the identically named town farther north in County Meath. This place did not spawn the famous Book of Kells (housed in Trinity College Library in Dublin).

Cost and Hours: Free, no set hours.

Getting There: You’ll find Kells Priory about 9 miles (15 km) south of Kilkenny or 6 miles (10 km) west of Jerpoint Abbey, just off the R-697 road. From Jerpoint Abbey, turn left, then take your first right through the village of Stoneyford. At the end of the village, turn left (at the sign for Kells Priory), then continue straight.

Visiting the Site: The main parking lot lies on a slope above the south side of the ruins. But I like to park at the pretty mill beside the Kings River on the north side of the ruins. The 100-yard stroll from the mill along the river makes for a photogenic approach to the complex. Watch where you walk and explore at your leisure. Consider bringing a picnic to enjoy. But please respect the site and leave no trash.

Founded in 1193 by Norman soldiers of fortune with Augustinian monks in tow, this priory grew into the intimidating structure that locals call “the seven castles” today. These “castles,” however, were actually Norman tower houses connected by a wall that enclosed the religious functions within. Inside the walls, the site is divided into two main areas: one is a huge interior courtyard (larger than a football field) dominated by the encircling tower houses; the other is a tangled medieval maze of rock walls (remnants of a cloister, a church, cellars, a medieval dormitory, and a graveyard).

The most dramatic 75-year period of the site’s history took place between 1252 and 1327, when it was attacked and burned three times (once by Edward the Bruce’s army of Scots). It was set to be the location of the famous Kilkenny witch trial of Alice Kyteler in 1324. But she had the money to engineer a secret escape while leaving her maid to take the heat...literally.

Rising high above the fertile Plain of Tipperary, the ▲▲▲ Rock of Cashel is one of Ireland’s most historic and evocative sights. Seat of the ancient kings of Munster (c. A.D. 300-1100), this is where St. Patrick baptized King Aengus in about A.D. 450. Strategically located and perfect for fortification, the Rock was fought over by local clans for hundreds of years. Finally, in 1101, clever Murtagh O’Brien gave the Rock to the Church. His seemingly benevolent donation increased his influence with the Church, while preventing his rivals, the powerful McCarthy clan, from regaining possession of the Rock. As Cashel evolved into an ecclesiastical center, Iron Age ring forts and thatch dwellings gave way to the majestic stone church buildings enjoyed by visitors today. Queen Elizabeth II’s history-making, four-day visit to Ireland in 2011 included a visit to the Rock.

Note that an extensive and essential restoration project should be finished by the time of your visit.

Cost and Hours: €8, families-€20, daily 9:00-19:00, mid-March-early June and mid-Sept-mid-Oct until 17:00, mid-Oct-mid-March until 16:30, last entry 45 minutes before closing; tel. 062/61437, www.heritageireland.ie.

Crowd-Beating Tips: Summer crowds flock to the Rock (worst June-Aug 11:00-15:00). Try to plan your visit for early or late in the day. If you’re here at a peak time, tour the Rock first and save the movie, museum, and Hall of the Vicars Choral for the end of your visit, when the tourist tide has receded. Otherwise, see the movie and museum first.

Dress Warmly: Bring a coat—deceptively sheltered conditions in the parking lot may not reflect those on the high, windy, exposed Rock. If you wear a hat, hold on to it.

Tours: Call ahead for the tour schedule (included in entry price, 45 minutes, tel. 062/61437). Otherwise, set your own pace with my self-guided tour.

Parking: Pay the €4.50 fee at the machine (under the Plexiglas shelter to the left of the exit) before returning to your car.

WCs: Use the basic ones at the base of the Rock next to the parking lot or the nicer ones in the Bru Boru Centre below the parking lot (there are none up on the Rock).

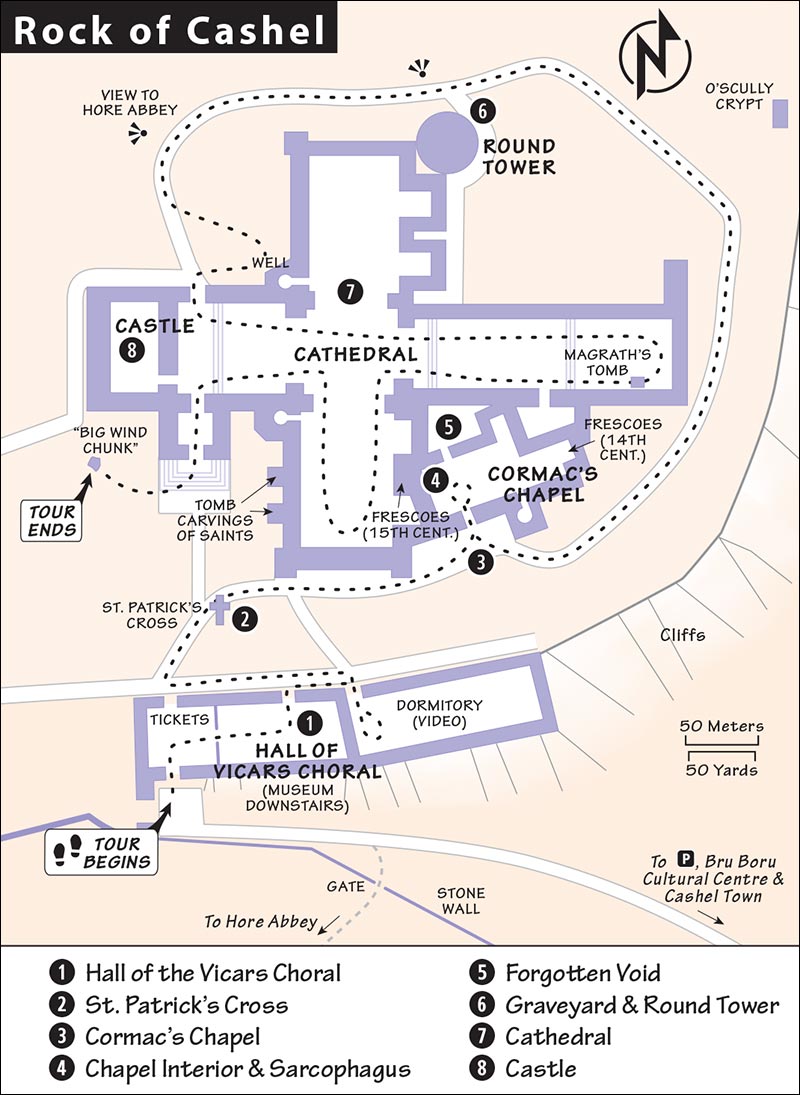

If you have time, start by visiting the Sounds of History Museum under the Bru Boru Cultural Centre (at the base of the Rock; see here) to learn more about the Rock before you ascend. From there, it’s a steep 100-yard walk up to the Rock itself. On this 200-foot-high outcrop of limestone, the first building you’ll encounter is the 15th-century Hall of the Vicars Choral, housing the ticket desk, a tiny museum (with an original 12th-century high cross dedicated to St. Patrick and a few replica artifacts), and a 20-minute video (2/hour, shown in the hall’s former dormitory). You’ll also find a round tower, an early Christian cross, a delightful Romanesque chapel, and a ruined Gothic cathedral, all surrounded by my favorite Celtic-cross graveyard.

SELF-GUIDED TOUR

SELF-GUIDED TOUR(See “Rock of Cashel” map, here.)

In a sense, architecture is the marriage of art (what can be imagined) and science (what’s possible). When this union is blended to serve God, it’s a potent mix. Nowhere else in Ireland can you better see the evolution of Irish devotion expressed in stone. This large lump of rock is a pedestal supporting a compact tangle of three dramatic architectural styles: early Christian (round tower and St. Patrick’s high cross), Romanesque (Cormac’s Chapel), and Gothic (the main cathedral).

• Follow this tour counterclockwise around the Rock. To start the tour, climb the indoor stairs opposite the ticket desk.

Hall of the Vicars Choral

Hall of the Vicars ChoralThis is the youngest building on the Rock (early 1400s). It housed the minor clerics appointed to sing during cathedral services. These vicars—who were granted nearby lands by the archbishop—lived comfortably here, with a large fireplace and white, lime-washed walls (to reflect light and act as a natural disinfectant that discouraged bugs as well). Window seats gave the blessedly literate vicars the best light to read by. The furniture is original, but the oak timber roof is a reconstruction, built to medieval specifications using wooden dowels instead of nails. The large wall tapestry, showing King Solomon with the Queen of Sheba, contains intentional errors—to remind viewers that only God can create perfection.

The vicars, who formed a sort of corporate body to assist the bishop with local administration, used a special seal to authorize documents such as land leases. You can see an enlarged wooden copy of the seal (hanging above the fireplace), depicting eight vicars surrounding a seated organist. It was a good system—until some of the greedier vicars duplicated the seal for their own purposes, forcing the archbishop to curtail its use.

• Go outside the hall into the grassy space 50 feet away and find...

St. Patrick’s Cross

St. Patrick’s CrossSt. Patrick baptized King Aengus at the Rock of Cashel in about A.D. 450. Legend has it that St. Patrick, intensely preoccupied with the holy ceremony, accidentally speared the foot of the king with his crosier staff while administering the baptismal sacrament. But the pagan king stoically held his tongue until the end of the ceremony, thinking this was part of the painful process of becoming a Christian. Probably not that many other converts stepped forward that day.

This 12th-century cross, a stub of its former glory, was carved to celebrate the handing over of the Rock to the Church 650 years after St. Patrick’s visit. Typical Irish high crosses use a ring around the cross’ head to support its arms and to symbolize the sun (making Christianity more appealing to the sun-worshipping Celts). But instead, this cross uses the Latin design: The weight of the arms is supported by two vertical beams on each side of the main shaft, representing the two criminals who were crucified beside Christ (today only one of these supports remains).

On my first visit, more than 30 years ago, the original cross still stood here, outside. But centuries of wind and rain were slowly eroding away important detail, so the cross was moved into the adjacent museum (opposite the ticket desk) and replaced by this replica.

• Turn your back on St. Patrick’s Cross, and walk about 100 feet slightly uphill along the gravel path beside the cathedral. Roughly opposite the far end of the Hall of the Vicars Choral is the entry to...

Cormac’s Chapel

Cormac’s ChapelAs the wild Celtic Christian church was reined in and reorganized by Rome 850 years ago, new architectural influences from continental Europe began to emerge on the remote Irish landscape. This small chapel—Ireland’s first and finest Romanesque church, constructed in 1134 by King Cormac MacCarthy—reflects this evolution. Travel in your imagination back to the 12th century, when this chapel and the tall round tower were the only stone structures on the Rock.

The “new” Romanesque style reflected the ancient Roman basilica floor plan. Its columns and rounded arches created an overall effect of massiveness and strength. Romanesque churches were like dark fortresses, with thick walls, squat towers, few windows, and minimal decoration. Irish stone churches of this period (like the one at Glendalough in the Wicklow Mountains) were simple rectangular buildings with few ornate stone carvings.

Legend says that the chapel’s easy-to-cut sandstone was quarried 12 miles away, and the blocks were passed from hand to hand back to the Rock. (It’s unlikely that they had the manpower to form a conga line that long—they probably used oxen-pulled carts.) The two square towers resemble those in Regensburg, Germany, further suggesting that well-traveled medieval Irish monks brought back new ideas from the Continent.

• The modern, dark-glass chapel door (always unlocked) is a recent addition to keep out nesting birds. Enter the chapel (remembering to close the door behind you) and let your eyes adjust to the low light.

Chapel Interior

Chapel InteriorJust inside the chapel, on your left, is an empty stone sarcophagus. Nobody knows for sure whose body once lay here (possibly the brother of King Cormac MacCarthy). The damaged front relief is carved in the Scandinavian Urnes style. Vikings raided Ireland, intermarried with the Irish, and were melting into Irish society by the time this chapel was built. Some scholars interpret the relief design (a tangle of snakes and beasts) as a figure-eight lying on its side, looping back and forth forever, symbolizing the eternity of the afterlife.

With your back to the sarcophagus, let your eyes wander around the chapel interior. You’re standing in the nave, lit by the three windows (partially blocked by the later cathedral, which is outside to the left) in the wall behind you. Overhead is a round vaulted ceiling with support ribs. The strong round arches support not only the heavy stone roof, but also the (unseen) second-story scriptorium chamber, where chilly monks, warmed only by candlelight, once carefully copied manuscripts.

The chancel arch, studded with fist-size heads, framed the altar (now gone). The lower heads are more grotesque, while those nearing the top become serene as they climb closer to God. The arch is off-center in relation to the nave, symbolic of Christ’s head drooping to the side as he died on the cross.

Walk into the chancel and look up at the ceiling, examining the faint frescoes, a labor of love from 850 years ago. Frescoes are rare in Ireland because of the perpetually moist climate. (Mixing pigments into wet plaster worked better in dry climates like Italy’s.) Once vividly colorful, then fading over time, these frescoes were further damaged during the Reformation. Such ornamentation was considered vain by Protestants, who piously whitewashed over them. These surviving frescoes were discovered under multiple layers of whitewash during painstaking modern restoration. The rich blue color came from lapis lazuli, an expensive gemstone imported from Asia.

• Walk through the other modern, dark-glass doorway (don’t let the birds in), opposite the door you used to enter the chapel. You’ll find yourself in a...

Forgotten Void

Forgotten VoidThis enclosed space (roughly 30 feet square) was created when the newer cathedral was wedged between the older chapel and the round tower. Once the main entrance into the chapel, this forgotten doorway is crowned by a finely carved tympanum that decorates the arch above it. It’s perfectly preserved because the huge cathedral shielded it from the wind and rain. The large lion (symbol of St. Mark’s gospel) is being hunted by a centaur (half-man, half-horse) archer wearing a Norman helmet (essential conehead attire in the late Middle Ages).

As you exit the chapel (turning left), take a look at the more exposed and weathered tympanum outside, above the south entrance. The carved, bloated “hippo” is actually an ox, representing Gospel author St. Luke.

• Tiptoe through the tombstones around the east end of the cathedral to the base of the round tower.

Graveyard and Round Tower

Graveyard and Round TowerThis graveyard still takes permanent guests—but only those put on a waiting list by their ancestors in 1930. A handful of these chosen few are still alive, and once they’re gone, the graveyard will be considered full. The 20-foot-tall stone shaft at the edge of the graveyard, marking the O’Scully family crypt, was once crowned by an elaborately carved Irish high cross—destroyed during a lightning storm in 1976.

Look out over the Plain of Tipperary. Called the “Golden Vale,” its rich soil makes it Ireland’s most prosperous farmland. In St. Patrick’s time, it was covered with oak forests (Ireland is now the most deforested nation in the EU). A path leads to the ruined 13th-century Hore Abbey in the fields below (free, always open and peaceful). The abbey is named for the Cistercian monks who wore simple gray robes, roughly the same color as hoarfrost (the ice crystals that form on morning grass).

Gaze up at the round tower, the first stone structure built on the Rock after the Church took over in 1101. The shape of these towers is unique to Ireland. Though you might think towers like this were chiefly intended as a place to hide in case of invasion, they were instead used primarily as bell towers and lookout posts. (Enemies could smoke out anyone inside the tower, and with enough warning, monks were better off concealing themselves in the countryside.) The tower stands 92 feet tall, with walls more than three feet thick. The doorway, which once had a rope ladder, was built high up not only for security, but also because having it at ground level would have weakened the foundation of the top-heavy structure. The interior once contained wooden floors connected by ladders, and served as safe storage for the monks’ precious sacramental treasures. The tower’s stability is impressive when you consider its age, the winds it has endured, and the shallowness of its foundation (only five feet below present ground level).

Continue walking around the cathedral’s north transept, noticing the square “put-log” holes in the exterior walls. During construction, wooden scaffolding was anchored into these holes. After the structure was completed, the builders simply sawed off the scaffolding, leaving small blocks of wood embedded in the walls. With time, the blocks rotted away, and the holes became favorite spots for birds to build their nests.

On your way to the cathedral entrance, in the corner where the north transept joins the nave, you’ll pass a small, easy-to-miss well. Without this essential water source, the Rock could never have withstood a siege and would not have been as valuable to clans and clergy. In 1848, a chalice was dredged from the well, likely thrown there by fleeing medieval monks intending to survive a raid. They didn’t make it. (If they had, they would have retrieved the chalice.)

• Now enter the...

Cathedral

CathedralTraditionally, the choir of a church (where the clergy celebrate Mass) faces east, while the nave stretches off to the west. Because this cathedral was squeezed between the preexisting chapel, round tower, and drinking well, the builders were forced to improvise—giving it an extra-long choir and a cramped nave.

Built between 1230 and 1290, the church’s pointed arches and high, narrow windows proclaim the Gothic style of the period (and let in more light than earlier Romanesque churches). Walk under the central bell tower and look up at the rib-vaulted ceiling. The hole in the middle was for a rope used to ring the church bells. The wooden roof is long gone. When the Protestant Lord Inchiquin (who became one of Oliver Cromwell’s generals) attacked the Catholic town of Cashel in 1647, hundreds of townsfolk fled to the sanctuary of this cathedral. Inchiquin packed turf around the exterior and burned the cathedral down, massacring those inside.

Ascend the terraces at the choir end of the cathedral, where the main altar once stood. Stand on the gravestones (of the 16th-century rich and famous) with your back to the east wall (where the narrow windows have crumbled away) and look back down toward the nave. The right wall of the choir is filled with graceful Gothic windows, while the solid left wall hides Cormac’s Chapel (which would have blocked any sunlight). The line of stone supports on the left wall once held the long, wooden balcony where the vicars sang. Closer to the altar, high on the same wall, is a small, rectangular window called the “leper’s squint”—which allowed unsightly lepers to view the altar during Mass without offending the congregation.

The grand wall tomb on the left contains the remains of archbishop Miler Magrath, the “scoundrel of Cashel,” who lived to be 100. From 1570 to 1622, Magrath was the Protestant archbishop of Cashel who simultaneously profited from his previous position as Catholic bishop of Down. He married twice, had lots of kids, confiscated the ornate tomb lid here from another bishop’s grave, and converted back to Catholicism on his deathbed.

• Walk back down the nave and turn left into the south transept.

Take a peek into the modern-roofed wooden structure against the wall on your left. It’s protecting 15th-century frescoes of the Crucifixion of Christ that were rediscovered during renovations in 2005. They’re as patchy and hard to make out (and just as rare for Ireland) as the century-older frescoes in the ceiling of Cormac’s Chapel. On the opposite side of this transept, in alcoves built into the wall, wonderful carvings of early Christian saints line the outside walls of tombs (look down at shin level).

• Return to the nave and continue down to the far end. Exit the cathedral on the left, through the porch entrance.

Castle

CastleBack outside, stand beside the huge chunk of wall debris and try to picture where it might have fit in the ruins above. This end of the cathedral was converted into an archbishop’s castle in the 1400s (shortening the nave even more). Looking high into the castle’s damaged top floors, you can see the bishop’s residence chamber and the secret passageways that were once hidden in the thick walls. Lord Inchiquin’s cannons weakened the structure during the 1647 massacre, and in 1848, a massive storm (known as “Night of the Big Wind” in Irish lore) flung the huge chunk next to you from the ruins above.

In the mid-1700s, the Anglican Church transferred cathedral status to St. John’s in town, and the archbishop abandoned the drafty Rock for a more comfortable residence, leaving the ruins that you see today.

Nestled below the Rock of Cashel parking lot, below the statue of the three blissed-out dancers, this center adds to your understanding of the Rock in its wider historical and cultural context. The highlight of the Sounds of History Museum downstairs is the exhibit showing the Rock’s gradual evolution from ancient ring fort to grand church ruins—projected down onto a large disc that visitors gather around.

Those interested in Ireland’s traditional music scene will enjoy the surprisingly good 15-minute film introduction to Irish trad music in the small museum theater.

Cost and Hours: Cultural Centre-free, Sounds of History Museum-€5; June-Aug Mon-Sat 9:00-18:00, closed Sun; Sept-May Mon-Fri 9:00-17:00, closed Sat-Sun; cafeteria, tel. 062/61122, www.bruboru.ie.

Performances: If you stay overnight in Cashel in summer, consider taking in a performance of the Bru Boru musical dance troupe in the center’s large theater (€20, €50 with dinner, July-Aug Tue-Sat, dinner at 18:30, performance at 21:00).

The huggable town at the base of the Rock affords a good break on the long drive from Dublin to Dingle (TI open daily 9:30-17:30, Nov-mid-March closed Sat-Sun, tel. 062/61333). The Heritage Centre, next door to the TI, presents a modest six-minute audio explanation of Cashel’s history around a walled town model. Parking requires a pay-and-display ticket (€1, enforced Mon-Sat 9:00-18:00, free Sun).

Sleeping: If you spend the night in Cashel, you’ll be treated to beautifully illuminated views of the ruins. The first listing is a classy hotel in the center of town (15-minute walk from the Rock). The rest are cozy, old-fashioned, and closer to the Rock.

$$ Bailey’s Hotel is Cashel’s best boutique hotel, housed in a fine Georgian townhouse (1709). Its 19 refurbished rooms are large, inviting, and well-appointed, perched above a great cellar-pub restaurant (parking, 42 Main Street, tel. 062/61937, www.baileyshotelcashel.com, info@baileyshotelcashel.com).

$ Joy’s Rockside House B&B is closest to the Rock, resting on its lower slopes. With four large, fresh rooms (three with views of the Rock), it’s the best value in Cashel (family room, cash only, Rock Villas Street, parking, tel. 062/63813, mobile 087-222-1676, www.joyrockside.com, joyrocksidehouse@eircom.net, Joan and Rem Joy).

$ Cashel Lodge is a well-kept rural oasis housed in an old stone grain warehouse, a 10-minute walk from the Rock near the Hore Abbey ruins. Its seven comfortable rooms combine unpretentious practicality with Irish country charm (camping spots, parking, Dundrum Road R-505, tel. 062/61003, www.cashel-lodge.com, info@cashel-lodge.com, Tom and Brid O’Brien).

$ Rockville House, 100 yards from the Rock, is a traditional place run by gentleman owner Patrick Hayes. The house itself has six fine rooms, and its old stablehouse, lovingly converted by Patrick, has five more (family room, cash only, 10 Dominic Street, tel. 062/61760, rockvillehse@eircom.net).

$ Wattie’s B&B has three rooms that feel lived-in and comfy (cash only, parking, 14 Dominic Street, tel. 062/61923, www.wattiesbandb.ie, wattiesbandb@eircom.net, Maria Dunne).

Eating: The following places are good lunch options near the Rock. $ Granny’s Kitchen is a tiny, violet-colored place with basic soup-and-sandwich lunches (next to the parking lot at the base of the Rock, daily 11:00-16:00). Popular $$ Chez Hans Café, with the best lunch selection and biggest crowds, is 75 yards down the road from the parking lot (Tue-Sat 12:00-17:30, closed Sun-Mon). And 50 yards farther down that same road, you’ll find the $ Rock House, an enthusiastically hosted cafeteria-style restaurant that’s upstairs above O’Dwyer’s pharmacy (daily 9:30-16:00, mobile 086-252-4268).

For a splurge dinner, look for the old stone church housing $$$$ Chez Hans, the classy cousin of Chez Hans Café, listed above (Tue-Sat 18:00-21:30, closed Sun-Mon, in an old church a block below the Rock, tel. 062/61177, www.chezhans.net).

In town, you’ll find several options. Next door to the TI, $ Feehan’s Bar is a convenient stop for a pub grub lunch (daily 12:00-16:00, tel. 062/61929). A couple of blocks farther into town, the $$ Cellar Pub hides beneath Bailey’s Hotel and serves satisfying dishes (daily 12:00-21:30, tel. 062/61937). Super Valu is the town’s supermarket (Mon-Sat 7:00-22:00, Sun 8:00-21:00, 30 Main Street).

Cashel Connections: Cashel has no train station; the closest one is 13 miles away in the town of Thurles. Buses run from Cashel to Dublin (4/day, 3 hours), Kilkenny (3/day, 2.5 hours), and Waterford (6/day, 2 hours). Bus info: www.buseireann.ie.