ST. REMIGIUS, OCTOBER 1 (JANUARY 15)

![]()

Remigius, or Rémy (437–533), was elected bishop of Reims at the tender age of twenty-two and while still a layman because of his reputation for learning and sanctity. St. Rémy is chiefly remembered for having persuaded the heathen king of the Franks, Clovis, to become Catholic. He baptized the king, along with three thousand of his subjects, on Christmas Day 496, thereby converting the Frankish people to the faith and contributing greatly to Western civilization.

France is particularly grateful to St. Rémy’s religious and cultural successes, which is why there are a couple of fine spirits named after him. St-Rémy Authentic brandy, which comes in VSOP, XO, and à la crème versions, can be enjoyed neat or in mixed drinks such as a St-Rémy Fix.

![]()

St-Rémy Fix

2 oz. St-Rémy brandy

1 tbsp. of sugar dissolved in 1 oz. lemon juice

½ oz. Cointreau

![]()

Pour all ingredients into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a hurricane or poco grande glass filled with ice.

![]()

Wine

The winery Domaine Saint-Rémy in the Alsace region of France has over half a dozen bottlings, including a Sylvaner, Rose, Riesling, Pinot Gris, Muscat, and Gewürztraminer, as well as a number of sparkling wines and Grand Crus.

GUARDIAN ANGELS, OCTOBER 2

![]()

Every individual has his own guardian angel, and it is also believed that many groups do as well, such as families, churches, dioceses, and nations. Our guardian angels protect us from harm and from the wiles of the Devil, and so we owe them an expression of thanks, or at least a toast. And since according to St. Thomas Aquinas they will remain with us as companions in Heaven, we might as well get used to them.

We have joked elsewhere that celestial beings don’t make good imbibers, but we could be wrong. Bourbon- and scotch-makers who age their whiskeys over many years speak of the “angels’ share”—the portion of their whiskey that is lost to evaporation. That evaporation can be considerable, emitting visible heat vapors from the open windows of the distillers’ warehouses, so apparently the angels can get rather thirsty. Pour yourself your favorite whiskey tonight, and put out an empty glass in honor of your guardian angel.

Or try a cocktail. There are a number of mixed drinks named after God’s heavenly messengers. We include here the Blushing Angel in the event that you may have done things in your life that would have made your guardian angel blush—if he had cheeks.

![]()

Blushing Angel

1½ oz. red Dubonnet

1 splash cranberry juice

5 oz. sparkling wine, chilled

1 lemon twist

![]()

Build Dubonnet and cranberry juice in a champagne flute (preferably chilled). Top with sparkling wine and garnish with lemon.

![]()

![]()

Beer and Wine

The Lost Abbey brewery in San Marcos, California, makes an Angel’s Share Ale, “infused with copious amounts of dark caramel malt to emphasize the vanilla and oak flavors found in freshly emptied bourbon or brandy barrels. Each batch spends no less than 12 months aging in the oak.” Their distribution, however, is limited.

On the other hand, the Italian San Angelo Pinot Grigio wine, produced by Castello Banfi in Montalcino, is widely available. The San Angelo or “Holy Angel” is probably St. Michael (shrines to St. Michael were popular on hills and mountains), but Heaven’s governor doesn’t mind sharing.

Lastly, for a special treat try some Angelica wine (see p. 200).

LAST CALL

Thank your guardian angel tonight for the near-misses in your life and ask him to keep up the good work.

ST. THÉRÈSE OF LISIEUX, OCTOBER 3

![]()

(OCTOBER 1)

One of the most popular saints of the twentieth century, Thérèse of Lisieux (1873–1897) was a French Carmelite nun who is most famous for her spirituality of the Little Way, which she describes in terms of a shortcut or elevator to God: “We are in a century of inventions; now one does not even have to take the trouble to climb the steps of a stairway; in the homes of the rich an elevator replaces them nicely. I, too, would like to find an elevator to lift me up to Jesus, for I am too little to climb the rough stairway of perfection.”

This “elevator” consists of offering little daily sacrifices by doing “the least of actions for love.” The “Little Flower,” as she is known, lived this life to perfection during her brief twenty-five years and was designated a doctor of the Church by Pope St. John Paul II.

Centuries before Thérèse’s time, the French Carmelites had invented Carmelite Water (see pp. 325–36). Perhaps the saint herself had some in the cloister. If you have this mysterious elixir on hand, you are fortunate indeed. If not, don’t worry about it. Since both finding and making Carmelite Water are difficult tasks, performing them now would be somewhat out of kilter with Thérèse’s focus on shortcuts. A Tripel Karmeliet (see p. 325) would be easier to track down, and so would the liqueur Millefiori (see p. 223), which is made from little flowers.

As for a cocktail, why not combine the Little Flower’s touching love of God with her image of an elevator? Move over, Aerosmith—there’s a new meaning for Love in an Elevator.

![]()

Love in an Elevator

1 oz. gin

½ oz. green curaçao liqueur

2½ oz. ginger ale (chilled)

![]()

Pour gin and curaçao into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass and add ginger ale.

![]()

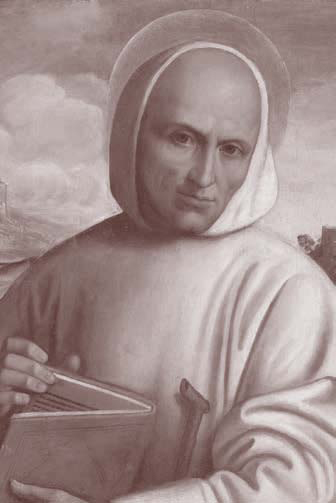

BL. COLUMBA MARMION, OCTOBER 3

![]()

The third of October now gives us two reasons to celebrate. In addition to the Little Flower, we can call on Bl. Columba Marmion (1858–1923), an Irish monk who was beatified by Pope St. John Paul II in 2000. Born Joseph Aloysius Marmion in Dublin, Bl. Columba entered the seminary when he was sixteen. By the age of twenty-seven, he was a respected diocesan priest and professor of metaphysics who had a gift for teaching revealed truths not as if they were “mere theorems of geometry having no bearing on the interior life,” but as mysteries to be lived. Marmion became a Benedictine and entered Maredsous Abbey in Belgium, eventually becoming its third abbot. He was an effective preacher and a voluminous author of spiritual works that are still read and admired today. He has been praised by Popes Benedict XV, Pius XI, Pius XII, Paul VI, and John Paul II, and some suspect that he will one day be declared the Doctor of Divine Adoption because of his important work on the doctrine of adoption in Christ.

Besides Bl. Marmion, Maredsous Abbey has one other claim to fame. It makes outstanding beer—or rather, it licenses its name to the brewery Duvel Moortgat, which has been making the outstanding abbey beer since 1963. Duvel Moortgat currently has three kinds: Maredsous Blonde, Maredsous Brune (a dubbel), and Maredsous Tripel. Bl. Columba Marmion would not object, I think, to spending an evening with one of his spiritual classics (like Christ, the Life of the Soul or Christ in His Mysteries) while savoring one of these brews.

ST. FRANCIS OF ASSISI, OCTOBER 4

![]()

St. Francis (ca. 1181–1226) was born Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, but his father nicknamed him Francesco, the “Frenchman.” This great saint, who dramatically converted to a life of radical poverty after hearing proclaimed the Gospel passage “Take neither gold nor silver,” was exceedingly humble. Even though he was the founder of the Franciscan order, he refused to be ordained a priest, remaining a deacon throughout his life.

Francis is usually pictured communicating with a bird, but perhaps the most memorable critter associated with this patron saint of animals and the environment is a wolf. The town of Gubbio was being terrorized by a ravenous wolf, and so St. Francis went out to meet it. After chastising “Brother Wolf” and making the sign of the cross over him, he convinced the wolf to stop his raids on the townsfolk’s livestock. In return, because the wolf had attacked only out of hunger, the saint made the townspeople promise to feed the wolf. The wolf and the citizens of Gubbio became friends from that day on, and they even mourned when the wolf eventually died.

To honor St. Francis’s peacemaking skills between man and beast, have a cocktail called the Big Bad Wolf (see p. 142). You can also try a San Francisco, a pleasant dessert drink that has a good balance of flavors and a brilliant vermillion hue. Its key ingredient is sloe gin, a sweet liqueur from sloeberry or blackthorn plum. Finally, have a St. Francis Cocktail, believed to be the prototype of the modern martini.

![]()

San Francisco

¾ oz. sloe gin

¾ oz. dry vermouth

¾ oz. sweet vermouth

1 dash orange bitters

1 dash Angostura bitters

1 cherry for garnish (optional)

![]()

Pour ingredients into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass and garnish with cherry.

![]()

St. Francis Cocktail

2 oz. gin

1 dash vermouth

1 dash orange bitters

![]()

Pour ingredients into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass and garnish with olives.

![]()

LAST CALL

St. Francis of Assisi used to call his body “Brother Ass.” Like any jackass or jennyass, the body sometimes needs a stick and sometimes a carrot, and sometimes even a sugar cube. Tonight, give Brother Ass the sugar cube.

The brewery Spaten-Franziskaner-Bräu in Munich, Germany, offers an assortment of beers under the Franziskaner label, which displays a friar enjoying a tankard of Weißbier.

As for wine, the Franciscan Estate in California’s Napa Valley and St. Francis in California’s Sonoma County may be Franciscan in name only, but both produce wines that are affordable and good. Or, with a little more effort, you can try for a bottle from St. Francis’s hometown of Assisi or the region thereof. Assisi is a DOC title in Umbria that covers a surprising variety of red, white, and rosé wines. Popular vineyards include Sportoletti, Falesco, Bodegas Hidalgo, and Legenda. Or look for something produced by Francescano Natura Assisi, a company founded to make the healthy and hearty foods and liqueurs of St. Francis’s beloved Umbria. In addition to various breads and olive oils, Francescano Natura Assisi makes a limoncello and an assortment of crèmes—lemon, melon, pistachio, and chocolate (which can be purchased at francescanonatura-assisi.com).

ST. BRUNO, OCTOBER 6

![]()

Bruno of Cologne (1030–1101) was a canon and a well-regarded theologian at Reims when he decided to leave the world. Withdrawing to the French Alps with six companions, he founded a hermitage near Grenoble called the Grand Charterhouse (“Chartreuse” in French). The Carthusian order that grew from this foundation combines the solitary life of the hermit with the communal life of the monk. St. Bruno was dragged away from his beloved Chartreuse to become the counselor of Pope Urban II and was never to see it again, although he was permitted to return to solitary life with some of his companions on a mountain in Italy, close enough to the papal court to be called on if necessary.

There is only one drink with which to toast the humble founder of the Carthusians—the 110-proof elixir that bears the name of Bruno’s Grand Charterhouse. Chartreuse is Catholicism’s most celebrated and distinctive distilled spirit. The stammering aesthete Anthony Blanche expresses his unique appreciation for this liqueur in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited: “Real G-g-green Chartreuse, made before the expulsion of the monks. There are five distinct tastes as it trickles over the tongue. It is like swallowing a sp-spectrum.” Yellow Chartreuse, on the other hand, is sweeter, colored with saffron, and 80 proof. This was the variety that caught the attention of a group of French army officers who visited the monastery in 1848. They publicized its virtues to the world, and by the turn of the century, even Russian tsar Nicolas II was making certain that a bottle of Chartreuse was always on his table.

The recipe for Chartreuse remains a tightly guarded secret, known by only two monks in the cloister. The monks handpick over 130 Alpine herbs, grind them up, and mix them in the right portions. After distillation, the liqueur is aged for several years in large oak casks and allowed to mature in the world’s longest liquor cellar. Chartreuse is one of only a handful of spirits that continues to age and improve after being bottled.

There are several cocktails in Drinking with the Saints that use Chartreuse—such as the San Martin (see p. 312), Bijou Cocktail (see p. 327), and Sir Knight (see p. 164)—but our favorite is the Green Ghost (see p. 419). We also offer an original mixed drink for the occasion, St. Bruno’s Delight (see below). That said, it is almost a shame to mix Chartreuse in a cocktail, since it is marvelous on its own when served neat at room temperature in small cordial glasses and sipped lightly. Newbies, remember that: sip lightly! It is a strong drink, but once the heat of the initial contact subsides, you will be amazed by the panoply of flavors on your palate.

Lastly, if you are throwing a party and need a group drink, try the Chartreuse Punch recipe below, which is from Martha Stewart.

![]()

St. Bruno’s Delight

2 oz. gin

1 splash yellow Chartreuse

1 pearl onion or 1 lemon twist

![]()

Pour gin and Chartreuse into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass and garnish with lemon or pearl onion.

Chartreuse Punch

2 cups gin, chilled

2 cups Chartreuse, chilled

½ cup plus 2 tbsp. lime juice, chilled

1 liter seltzer, chilled

½ cup simple syrup, chilled

slices of lime

![]()

Build all ingredients in a punch bowl with ice. Use a ladle to serve into old fashioned or punch glasses filled with ice. Garnish with lime. Makes twenty servings.

![]()

Here is the same recipe again pared down to two servings.

![]()

Chartreuse Punch for Two

1 oz. Chartreuse, chilled

1 oz. gin, chilled

2 tsp. lime juice, chilled

1½ tsp. simple syrup, chilled

seltzer water, chilled

2 lime slices

![]()

Mix all ingredients except seltzer and lime in a shaker or mixing glass and pour into two old fashioned or punch glasses filled with crushed ice. Add a splash of seltzer to each glass and garnish with lime.

![]()

![]()

ST. FAITH, OCTOBER 6

![]()

St. Faith (fl. 3rd c.) may have been a Christian maiden from Aquitaine who was arrested, tortured, and martyred for refusing to participate in pagan sacrifices. We say “may have” because some scholars speculate that she never existed. “Saint Faith” (“Sainte Foy” to the French and “Santa Fe” to the Spanish) could be a misinterpretation of Sancta Fides, which can also mean “Holy Faith.” Then again, the remains of somebody were transferred in AD 866 to Conques, along the pilgrimage route to Compostela. And surely the AOC appellation Sainte-Foy-Bordeaux, at the eastern edge of the Bordeaux winegrowing region, is based on more than just a misunderstanding. But to be safe, toast on this day to Nostra Sancta Fides (“Our Saint Faith” or “Our Holy Faith”) and let Our Good Lord sort it out.

OUR LADY OF THE ROSARY, OCTOBER 7

![]()

A “rosary,” or rosarium, is literally a garland of roses, but it is more familiar to Catholics as a special garland of prayers offered to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Developed in the Middle Ages, the rosary is one of the Church’s most powerful weapons in her spiritual arsenal.

The feast of the Holy Rosary was instituted to commemorate the spectacular victory of the outnumbered armada of the Holy League over the mighty Ottoman navy at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. Pope St. Pius V instructed all of Italy to pray the rosary as the battle took place off the coast of Greece. As the Turks were being defeated, the pope was in a meeting with his cardinals in Rome over six hundred miles away. Suddenly he stopped working, opened a window, looked at the sky, and cried out, “Now is not the time to talk business any more but to give thanks to God for the victory He has granted to the arms of the Christians.” The holy pontiff attributed this victory, which turned the tide of Islamic dominance in the Mediterranean Sea, to the rosary and to Our Lady’s intercession.

For the rosary, Four Roses in Lawrenceburg, Kentucky, makes excellent bourbon under a number of different labels that can be taken neat or in your favorite bourbon cocktail. For the great naval battle, Lepanto brandy from Andalusia, Spain, is a fitting nominal choice for today, either on its own or in a cocktail such as the Lady Victorious (see below).

Or go for the jugular in your celebration of the crushing defeat of militant Mohammedans with a glass of Turk’s Blood.

![]()

Turk’s Blood

3 oz. champagne (chilled)

2 oz. Burgundy wine

![]()

Pour into a champagne saucer and serve. If you don’t have a champagne saucer, a wine glass or champagne flute will do, and if you don’t have a Burgundy wine, use a Pinot Noir.

![]()

For something less sanguinary, try our original cocktail Lady Victorious, a tribute to the Blessed Virgin as Our Lady of Victory, the original name of this feast. Lepanto brandy recalls where the battle was met; Grand Marnier, which can be translated “Great Mariner,” honors the commander of the victorious Christian fleet, Don Jon of Austria; the bitters commemorate the harshness of war; and the lemon wedge symbolizes victory over the crescent of Islam.

![]()

Lady Victorious

2 oz. Lepanto brandy

½ oz. Grand Marnier

2 dashes Peychaud bitters

2 dashes orange bitters

1 lemon wedge

![]()

Pour all ingredients except lemon wedge into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass and garnish with lemon.

![]()

LAST CALL

Tonight, you have two choices (after praying the rosary, of course): read Chesterton’s magnificent poem “Lepanto” beforehand and select your favorite verses for a toast, or ply your friends with several rounds and then take turns reciting stanzas. Failing to read “Lepanto” is not an option.

Beer

The Cathedral Square Brewery in St. Louis, Missouri, will help you honor the main prayer of the rosary in either its English or Latin version. They brew a Hail Mary Belgian-style IPA and an Ave Maria Double Abbey Ale.

ST. BRIDGET, OCTOBER 8 (JULY 23)

![]()

St. Bridget of Sweden (1303–1373) is one of the Church’s greatest mystics, the patroness of Sweden, and one of the six patron saints of Europe (along with Sts. Benedict, Cyril and Methodius, Catherine of Siena, and Edith Stein). At the age of thirteen, Bridget married Ulf Gudmarsson, lord of Närke. She had eight children with him, including St. Catherine of Sweden. On his deathbed and with his wife’s consent, Ulf became a Cistercian monk. Bridget mourned his loss greatly, saying that she had loved him like her own body. She became a member of the Third Order of St. Francis and began to receive visions about founding the Order of the Most Holy Savior (the “Brigittines”). The order was unique in that it was founded by a woman and had both men and women, albeit within separate cloisters.

When Our Lord commanded St. Bridget to found this order, he told her that it would “be a vineyard whose wine would revivify the Church.” Obviously, then, Our Lord has nothing against wine. And believe it or not, wine is made in Sweden despite its frigid climate. A number of recognizable varietals are produced, such as Cabernet Sauvignon, but one interesting possibility is ice wine, a sweet dessert wine made from grapes that have been frozen while still on the vine. (The ice wine made by Inniskillin is relatively easy to track down.)

Another way to revivify the domestic Church on this day is to sample any of Sweden’s other alcohol offerings, such as Swedish beer (the Swedes like pilsners), schnapps, aquavit, or vodka (Absolut is both ubiquitous and well regarded). Or see if you can track down some Swedish punch, or punsch, a sweet and smoky Scandinavian liqueur that is made from cane sugar and Javanese rice. Popular brands include Cederlund’s, Carlshamns, and, increasingly, Kronan. If you find a bottle, put it in a Doctor.

![]()

Doctor

2 oz. Swedish punch (punsch)

1 oz. lemon or lime juice

![]()

Pour ingredients into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass.

![]()

![]()

St. Dionysius, or Denis (d. ca. 250), the first bishop of Paris, was beheaded along with the priest Rusticus and the deacon Eleutherius during the Decian persecution. According to legend, after his execution St. Denis picked up his head and carried it six miles while preaching a sermon. The site of his martyrdom is now the famous Abbey of Saint-Denis, where the kings of France are buried. The French armies used his name as a battle cry, either shouting “Saint Denis!” or “Montjoie! Saint Denis!” (A montjoie, from mons gaudii or mons Jovis, was a milestone for soldiers later used to signify a standard that showed the troops the right way into battle.) St. Denis, one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, is, fittingly, invoked against headaches.

Clos Saint-Denis is an appellation and Grand Cru vineyard for red wine in the Burgundy wine region of France; Morey-Saint-Denis is another appellation from the same region.

And for a mixed drink, how about a Headless Horseman?

LAST CALL

Whatever you drink, raise it high and cry out, “Montjoie! Saint Denis!”

![]()

Headless Horseman

2 oz. vodka

3 dashes aromatic bitters

ginger ale

1 orange slice

![]()

Pour the vodka and bitters into a highball glass filled with ice. Fill with ginger ale and stir until cold. Garnish with orange slice.

![]()

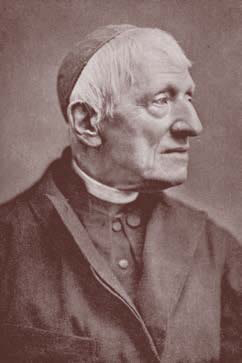

BL. JOHN HENRY NEWMAN, OCTOBER 9

![]()

On the same day that we celebrate a saint who lost his head we celebrate another who found his. John Henry Newman (1801–1890) was the most famous intellectual in the Church of England when he shocked all of Great Britain and converted to the Catholic faith. Newman lost many a friend because of his decision, but his loyalty to the Church was eventually rewarded when he was made a cardinal by Pope Leo XIII. Newman was the greatest theologian of the nineteenth century and a keen critic of the liberalism of his day. He was beatified by Pope Benedict XVI in 2010, and we will bet our bar tab that he will one day be canonized a saint and declared a doctor of the Church.

Even prior to his conversion Newman had little patience for the “two-bottle orthodox,” self-indulgent Anglican pastors whose “greatest religious zeal manifested itself in the [copious] drinking of port wine to the health of ‘the Church and King.’” But Newman was no teetotaler. He served port and brandy to his guests and partook as well. At an inn in Switzerland, he complained to a friend that the wine was “all acid” and the brandy “wishy washy,” a criticism which suggests that the holy scholar had a taste for the good stuff.

And Father Newman played snapdragon, a risky game in which raisins are snatched out of a dish of burning brandy and eaten alight. Coincidentally, snapdragon is also the name of the flower that grew on the wall opposite Newman’s freshman lodgings at Trinity College, Oxford, and symbolized to him his “own perpetual residence even unto death” at his beloved university—a residency that, thanks to his conversion, was to be far from perpetual.

Tonight, savor the lifestyle of a Victorian English gentleman with your finest port or brandy. You can also play snapdragon with your friends. It is traditionally a Christmastide game, but on October 13, 1848, Newman wrote that he had played it recently—perhaps on this very day. Better yet, drop three raisins in a glass of brandy and drink to Bl. John Henry (three to symbolize Newman’s alma mater Trinity College and his theological work in service to the Triune God). You can call the drink a Snapdragon, though we don’t advise setting it on fire.

Or, have a Cardinal cocktail. The (London) dry gin can represent Newman’s English nationality, and the Campari his sometimes bittersweet turn to Italy and Rome.

Beer and Wine

As we know from his letters, young Newman enjoyed “fine strong beer.” Honor Newman’s good taste with a St. Peter’s Organic English Ale (see p. 145), an English brew that our friend Dr. Robert Kirby selected in order to celebrate the occasion when, following Newman’s footsteps, he left Canterbury for Rome. The “organic” is evocative of organic development in Church doctrine, a notion Newman famously explored and explained, and the “St. Peter’s” can serve as an obvious reference to the Barque that Newman boarded to the astonishment of all.

Cardinal

1 oz. gin

¾ oz. Campari

¾ oz. dry vermouth

1 lemon twist

![]()

Stir all ingredients except lemon twist in a mixing glass or shaker filled with ice and strain into a cocktail glass. Garnish with lemon twist.

![]()

As for wine, an older Newman praised a dinner he had in Langres, France, that included claret (see p. 292), Burgundy, sherry, and rum. Use your discretion to fill in the details.

LAST CALL

Newman stands out among the great figures mentioned in Drinking with the Saints because he is the only one on record for proposing a toast. Here is the full passage, from his Letter to the Duke of Norfolk: “Certainly, if I am obliged to bring religion into after-dinner toasts (which indeed does not seem quite the thing), I shall drink—to the Pope, if you please—still, to Conscience first, and to the Pope afterwards.”

Newman’s remark is often misconstrued as a green light to dissent from the Church’s teachings, but it was actually meant to affirm the doctrine of papal infallibility properly understood. For Newman, the key to conscience is that it is well formed, which requires a great deal of study, docility, and humility—qualities not often found today among religious naysayers.

As for Newman’s opinion about the incompatibility of religion and after-dinner toasts, our own well-formed (or at least well-marinated) conscience compels us to dissent.

And so a toast: To Conscience first, and to Bl. John Henry Newman and the pope afterward.

And if you would like something literary for a chaser, a poem by Newman would be worth reading tonight. We suggest “Snapdragon,” about his memories of Trinity College, his beautiful hymn “Lead, Kindly Light,” and our personal favorite, his poem “The Sign of the Cross.”

MATERNITY OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY,

![]()

OCTOBER 11

In AD 431, the Council of Ephesus solemnly defined Mary as the Theotokos, the “God-bearer,” or Mother of God; and in 1931, to celebrate the fifteenth centenary of the council, Pope Pius XI instituted the feast of the Motherhood of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Mary is not only truly the Mother of God, as Catholics proclaim everywhere, but she is our mother as well. “All of us who are united to Jesus Christ and are members of His Body,” the same pope explains, “were born of Mary, as a body is joined to its head. She is mother of us all spiritually, but truly mother of the members of Christ.”

Cocktail and Wine

For the mother whose prayers and concern for us is like milk to our souls, have a Mother’s Milk cocktail.

![]()

Mother’s Milk

1½ oz. gin

1 oz. cream

½ tsp. sugar

nutmeg

![]()

Pour all ingredients except nutmeg into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass and sprinkle with nutmeg.

![]()

As for wine, there is no better name in the industry to suit the occasion than Liebfraumilch, a semisweet white German wine that literally means “Our Dear Lady’s milk.” Originally, this wine came only from grapes grown near the Liebfrauenkirche (the Church of Our Dear Lady) in the city of Worms. Today, the name designates a style of wine produced in the regions of Rheinhessen, Palatinate, Rheingau, and Nahe. A victim of its own success through brands such as Blue Nun (see p. 250), the once enormously popular Liebfraumilch has come to be seen as a low-quality wine. That’s a bit unfair. Although it is true that Spätlese or Auslese are made in the same way but from higher-quality grapes, German wine law requires Liebfraumilch to be at the Qualitätswein bestimmter Anbaugebiete (QbA), the third-highest ranking out of a possible four. Besides, while some may regard its “smoky character” as a fault, “others will claim it as part of the natural style of the wine.” “How dull it would be,” writes André Simon in his Wines of the World, “if it were not so and wine became a standard product, bland and tailor-made to suit an average taste, never giving offense and never arousing interest.” Amen!

LAST CALL

Knowing that you have a true mother in Heaven looking out for you should put an extra twinkle in your eye and spring in your step today. As the traditional Vespers antiphon for this feast puts it: “Let us celebrate the Maternity of the Blessed Mary ever Virgin with sweetness [my emphasis].” A toast, then, to Our Blessed Mother: May her sweet maternal love draw us closer to her Son. Or take your milky drink in hand and recite the first verse of the ancient hymn “O Gloriosa Virginum”:

O Heaven’s glorious mistress,

Enthroned above the starry sky,

Thou feedest with thy sacred breast

Thy own Creator, Lord most high.

ST. ROMULUS, OCTOBER 13

![]()

(NOVEMBER 6)

For reasons that are unclear, Romulus, or Rœmu (d. ca. 641), bishop of Genoa, fled his see and died in a cave in the beautiful town on the Italian Riviera that now bears his name, Sanremo.

There are a couple of other things that bear the saint’s name: a tasty cocktail and some Italian and California wine. Let’s start with the cocktail.

![]()

San Remo

1 oz. red Dubonnet

1 sugar cube

2 dashes Angostura bitters

champagne, chilled

1 orange twist

![]()

Build Dubonnet, sugar, and bitters in a champagne flute (preferably chilled). Top with champagne (or any sparkling wine) and garnish with orange.

![]()

![]()

Wine

In the north of Italy, the San Remo winery makes an inexpensive Fragolino, a sparkling red wine with hints of strawberry. On the other side of the world, Benziger’s Signaterra brand in the Russian River Valley of Northern California has a San Remo Vineyard that produces fine Pinot Noir grapes.

ST. TERESA OF ÁVILA, OCTOBER 15

![]()

When she was a little girl, Teresa (1515–1582) and her brother dreamt of becoming martyrs, and so they set off for the land of the Moors. Their plan for an easy access to Heaven was thwarted, however, by an uncle who met them on the way and quickly brought them back to their worried mother. They next resolved to become hermits, but they could never find enough stones to build their hermitages in the family garden.

St. Teresa recounted these stories later in her life, for she had a lovely, self-deprecating sense of humor. She went on to become a spiritual grown-up of the first order. She reformed the Carmelites, which she had joined, and was eventually declared a doctor of the Church for her deep psychological and spiritual insights into how to become holy.

One good starting place is with drinks associated with the Carmelite order, such as Carmelite Water (see p. 326).

The Santa Teresa distillery in Venezuela is a family-run business that makes an assortment of rums. Its aged 1796 rum, which is made from a distinctive “solera” method, is considered particularly good.

In the fifth mansion of St. Teresa’s The Interior Castle, the butterfly serves as an important metaphor for spiritual transformation. You can internalize a butterfly of your own with the following Butterfly cocktail.

St. Teresa died during the night of October 4–October 15. No, that’s not a typo. She passed away on the very day on which the Gregorian calendar replaced the Julian calendar, an adjustment that required the deletion of ten days from the year 1582. Thus, the morning after October 4 in that singular year was October 15. Drink a fruity cocktail called the Time Warp in remembrance of the peculiar chronological circumstances in which St. Teresa entered eternity.

LAST CALL

As mentioned, St. Teresa had a wonderfully dry sense of humor and is reputed to have once said, “Lord, save me from sour-faced saints.” Make this prayer your own tonight by turning it into a toast as you vow never to confuse life-giving sanctity with buzz-killing sanctimony.

Beer and Wine

Tripel Karmeliet beer (see p. 325) is a good generic choice for this Carmelite saint. And Avila Wine and Roasting Company is one of a handful of wineries on the Avila Wine Trail between San Luis Obispo and Pismo Beach in California.

![]()

Butterfly

¾ oz. dry vermouth

¾ oz. sweet vermouth

½ oz. red Dubonnet

½ oz. orange juice

![]()

Pour all ingredients into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass.

![]()

Time Warp

⅔ oz. melon liqueur

¼ oz. blue curaçao liqueur

¼ oz. raspberry liqueur

½ oz. coconut rum

½ oz. pineapple juice

1 cherry (garnish)

![]()

Pour all ingredients except cherry into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass and garnish with cherry.

![]()

ST. MARGARET MARY ALACOQUE,

![]()

OCTOBER 17 (OCTOBER 16)

In her childhood, St. Margaret Mary Alacoque (1647–1690) had been bedridden with rheumatic fever for four years when she made a vow to enter religious life, at which point she instantly became better. Later in her life, Margaret Mary forgot about her vow and, complying with her mother’s wish for her to marry, started attending social events with her brothers. But one night, she returned home from a carnival ball in her finery and had a vision of Jesus, scourged and bloody, reproaching her and telling her how much He loved her because of her vow.

Hesitating no longer, the young woman entered the Visitation Convent and became a nun. Eventually, she received additional visions from Jesus, who instructed her to spread devotion to His Sacred Heart and made Twelve Promises to her for those who kept this devotion, including the grace of final repentance to anyone who receives Holy Communion on the first Friday of nine consecutive months. Despite great resistance she succeeded in spreading the devotion, and it has remained popular ever since.

To honor St. Margaret Mary’s connection to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, have a drink associated with Its feast: the Heart Warmer No. 1 (see p. 19), the Heart Warmer No. 2 (see p. 119), and the Cara Sposa (see p. 423). Or borrow some scotch from St. Regulus below.

ST. REGULUS, OCTOBER 17

![]()

St. Regulus, also known as St. Rule or St. Riagal, was, according to dubious historical testimony, a fourth-century cleric from Patras in Greece who fled to Scotland in AD 345 with the bones of St. Andrew and deposited them at the former royal burgh of St. Andrews, home of the University of St. Andrews and the birthplace of golf. His feast never made the universal calendar, but in the Aberdeen Breviary it is listed as October 17.

Scotch, anyone? (See pp. 330–31.)

ST. LUKE, OCTOBER 18

![]()

St. Luke the Evangelist is the author of the third Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles. He did not know Our Lord personally, but he was a disciple of St. Paul and, it is believed, a confidant of Our Lady, which may be why his Gospel includes so many details about Christ’s infancy and childhood that are not found elsewhere.

The symbol of St. Luke is the ox, since his Gospel begins with Zachary the priest sacrificing in the Holy Temple. What better drink to have, then, than Ox Blood? We’re not sure what real ox blood tastes like, but this swank cocktail has a sweet start and an orange bite for a finish.

Ox Blood Invented by R. Emmerich

1 oz. cherry brandy (kirsch)

1 oz. gin

1 oz. sweet vermouth

2 dashes orange bitters

3 dashes brown curaçao (any curaçao is fine)

![]()

Pour all ingredients into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass and serve.

![]()

St. Luke is also credited with having painted or “written” a number of important icons of the Madonna and Child, such as Our Lady of Częstochowa in Poland, the icon Salus Populi Romani (“Protectoress of the Roman People”) in Rome’s Basilica of St. Mary Major, and the Theotokos of Vladimir in Russia. Amaretto would be a good choice for today because it was invented by a beautiful Italian innkeeper who posed for a Madonna painting by the Renaissance artist Bernardino Luini. Like the little drummer boy, the lovely model showed her gratitude to Luini for this honor by doing what she did best, and so she perfected a liqueur from apricots.

Finally, look for a vigorous red wine from Hungary called Egri Bikavér (“Bull’s Blood”).

ST. VERANUS, OCTOBER 19

![]()

St. Veranus of Cavaillon (513–590), also known as Véran, Vrain, and Verano, was a zealous French priest whose growing popularity made him seek solitude as a hermit in Vaucluse. According to one legend, he drove a winged dragon from the area by making the sign of the cross over it and adjuring it never to harm anyone again. On his way back from a pilgrimage to Rome, he converted the town of Albenga in Italy to Christianity. He was elected bishop of Cavaillon upon his return to France and became a zealous enforcer of ecclesiastical discipline. In the Middle Ages, mothers prayed to him for the health of their small children.

Saint-Véran is the AOC appellation for white Burgundy wines—made exclusively from Chardonnay grapes—from the Mâconnais subregion of the department of Saône-et-Loire. Its vineyards include Le Clos, Au Château, les Peiguins, Au Bourg, A la Croix, Aux Bulands, and Vers le Mont.

Closer to home is a St. Vrain Tripel Ale made by the Left Hand Brewing Company in Longmont, Colorado. The beer is named after a bygone local trapper rather than our saint, but where did the trapper get his surname from, eh?

And if you can find neither wine nor beer with St. Veranus’s moniker, mix yourself a Green Dragon cocktail (see p. 176). Be sure to make the sign of the cross over it before banishing it to your gullet.

ST. CELINE, OCTOBER 21

![]()

St. Celine (d. 458) was the mother of St. Remigius, bishop of Reims (see p. 268). Apparently Remigius’s birth was miraculous, since Celine was well past her child-bearing years. She also gave sight to a blind hermit named Montanus. After a holy life, Celine was probably buried at Cerny (near Lyons, France), but we are not certain since her relics were destroyed during the French Revolution.

Celine’s cultus has had a rough go of it—not much of an extant biography, her remains destroyed by barbaric Jacobins, and even her final resting place an uncertainty. In her honor, then, we recommend a Belgian tripel style by Pour Decisions Brewing Company called St. Whatshername. But since Pour Decisions is a microbrewery in Roseville, Minnesota, you may have as much luck finding a bottle as you do of finding St. Celine’s relics. Your odds are a little better with a St. Celine, a natural sweet-red blend with hints of black currant and raspberry jam made by Douglas Green Wines in South Africa.

St. Celine’s name means “heavenly,” so how about a sweet after-dinner peck on the cheek from St. Celine in the form of a Kiss from Heaven?

![]()

Kiss from Heaven

1 oz. cognac

¾ oz. Drambuie

¾ oz. dry vermouth

![]()

Pour all ingredients into a mixing glass or shaker filled with ice and stir until very cold. Strain into a cocktail glass.

![]()

BL. KARL OF AUSTRIA, OCTOBER 21

![]()

Bl. Karl Franz Joseph Ludwig Hubert Georg Otto Marie (1887–1922) was also known as Charles I of Austria and Charles IV of Hungary, the last ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the last emperor of Austria, the last king of Hungary, the last king of Bohemia and Croatia, the last king of Galicia and Lodomeria, and the last monarch of the famed house of Hapsburg-Lorraine. In addition to these august titles and distinctions, Bl. Karl is known within the Catholic fold as a just ruler who strove to implement the principles of Catholic social teaching in the face of an insane world war. His conduct during World War I was exemplary. He was the only major political leader in the conflict to support Pope Benedict XV’s eminently reasonable peace efforts, which were rejected by zealots like President Woodrow Wilson. After the defeat of his empire, Karl steered his homeland clear of civil war but was banished from it as a result. The leader of a once-great Catholic empire ended his days at the age of thirty-four in exile and poverty on the island of Madeira. His feast day on the calendar is unique in that it marks not his earthly passing but the anniversary of his wedding to his faithful wife, Princess Zita.

Beer and Wine

Let the lands of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire yield up their fruits in honor of their last, noble, and saintly king. The options are almost limitless. Austrian beer, Austrian wines, and Austrian liqueurs are excellent—Maraska Maraschino liqueur, for instance, bears the Imperial coat of arms because it obtained the title Imperial Regia Privilegiata in 1804 from the Austrian emperor (see p. 53). Hungary, on the other hand, has pálinka brandy (see p. 237), Tokaji wine (see p. 319), and Unicum liqueur (see p. 406).

Or let the island of Madeira off the coast of Portugal pay tribute to the emperor who died there a pauper. Like port, Madeira wine is a well-regarded Portuguese wine fortified with neutral grape spirits. Originally, the spirits were added to keep the wine from turning bad on long ship voyages during the age of exploration, but it was eventually discovered, after an unsold shipment of fortified wine returned from a round trip, that the heat and movement of the ships improved the quality of their liquid cargo. (Today, Madeira is “baked” to achieve the same effect.) There are four kinds of Madeira, ranging from dry to sweet, respectively: Sercial, Verdelho, Bual (Boal), and Malmsey.

LAST CALL

Bl. Karl’s life motto was: “I strive always in all things to understand as clearly as possible and follow the will of God, and this in the most perfect way.” Strive to work this beautiful sentiment into a worthy toast.

ST. JOHN PAUL II, OCTOBER 22

![]()

We move from Bl. Karl to St. Karol

![]() (1920–2005), better known as Pope John Paul II. This charismatic successor of St. Peter probably belongs in the Guinness Book of World Records for breaking the most world records, at least the important ones. St. John Paul II was the first non-Italian pope in 450 years, the most traveled pope in history (129 countries!), the first pope to enter a synagogue on an official papal visit, and the pope who beatified and canonized more persons than all his predecessors combined (how about Drinking with JP II’s Blesseds and Saints as a sequel to this book?). The pope’s funeral Mass was the largest gathering of heads of state in world history, with four kings, five queens, and over seventy presidents and prime ministers in attendance. It was probably also the largest pilgrimage event in the history of Christianity, with four million mourners arriving in Rome to honor their beloved Holy Father and chant “Santo subito!”—“Sainthood now!”

(1920–2005), better known as Pope John Paul II. This charismatic successor of St. Peter probably belongs in the Guinness Book of World Records for breaking the most world records, at least the important ones. St. John Paul II was the first non-Italian pope in 450 years, the most traveled pope in history (129 countries!), the first pope to enter a synagogue on an official papal visit, and the pope who beatified and canonized more persons than all his predecessors combined (how about Drinking with JP II’s Blesseds and Saints as a sequel to this book?). The pope’s funeral Mass was the largest gathering of heads of state in world history, with four kings, five queens, and over seventy presidents and prime ministers in attendance. It was probably also the largest pilgrimage event in the history of Christianity, with four million mourners arriving in Rome to honor their beloved Holy Father and chant “Santo subito!”—“Sainthood now!”

When he was archbishop of Krakow in the 1960s, the communist secret police spied on the future John Paul II incessantly, sometimes even using priests they had managed to turn. One of the things they wanted to know about was his consumption of alcohol: whether he liked it, how much he drank it, and how often. Their findings weren’t terribly juicy, as

![]() was ascetical in his daily habits and eschewed the life of a gourmand. Unlike most Poles, he did not fancy vodka but preferred “a glass of white wine diluted with water or the occasional beer.”

was ascetical in his daily habits and eschewed the life of a gourmand. Unlike most Poles, he did not fancy vodka but preferred “a glass of white wine diluted with water or the occasional beer.”

To honor the man who did more than anyone else to bring down the Iron Curtain and rescue Eastern Europe from the tyranny of communism, you can do what he did when he summered in the Italian Alps: picnic under a pine tree with “sardines, hard-boiled eggs that he sliced with a camping knife, and a bottle of local white wine cut with water from the gushing stream.” That wine, incidentally, would have come from the Veneto region (see pp. 12–14, 187–88).

But if you’re hankering for a cocktail, let one be provided by another saint from October 22.

ST. MARY SALOME, OCTOBER 22

![]()

The mother of the Apostles James and John, St. Mary Salome is one of the three myrrh-bearing Marys who came to the tomb on the first Easter Sunday. The century-old Salomé Cocktail is probably named after that other woman, the naughty dancer who cost St. John the Baptist his head, but we won’t let that spoil the mood.

![]()

Salomé Cocktail

1 oz. gin

¾ oz. dry vermouth

¾ oz. red Dubonnet

![]()

Stir ingredients in a shaker or mixing glass filled with ice, strain, and serve in a cocktail glass.

![]()

LAST CALL

The Claretians have a special devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Tweak their motto into a toast: “Her sons rose up, and proclaimed her most blessed throughout the world.”

ST. ANTHONY MARY CLARET,

![]()

OCTOBER 23 (OCTOBER 24)

Antonio María Claret y Clara (1807–1870) was a great preacher and the author of 150 books. He founded the Missionary Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, better known as the Claretians. For a while he was archbishop of Santiago in Cuba, where he denounced slavery and racism, developed agricultural methods that he tested himself, and instituted trade schools and credit unions for the poor. Anthony was equally at home at the upper end of the social spectrum and was made confessor of Queen Isabella II of Spain. When the queen was exiled, he was placed under house arrest and died in the Cistercian monastery at Fontfroide, France.

It is difficult to resist uncorking a good claret in remembrance of St. Anthony Mary’s last name. “Claret” is the British term for a red wine from Bordeaux, France, which is almost 90 percent of the wine produced in Bordeaux. The term, which means “clear,” hearkens back to the Middle Ages when Bordeaux wines were paler than they are now, almost like a rosé. “Claret” can also refer to a deep purplish-red, the current color of a red Bordeaux (which is made from hearty grapes like Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot). Coincidentally, it is also the color of St. Anthony Mary Claret’s cassock.

ST. BOETHIUS, OCTOBER 23

![]()

Graduates with a liberal arts education may be surprised to see the “St.” prefixed to the name of the author of the famous Consolation of Philosophy, a book that confronts the thorny problems of evil, divine providence, and happiness. But Boethius’s cult has been kept in Pavia and elsewhere for centuries and was affirmed by the Sacred Congregation of Rites in 1883. A well-educated Roman who had climbed the ladder of political success, Boethius (480–524) was unjustly condemned for treachery and sorcery by envious and corrupt men. Some believe that he died a martyr for the Catholic faith.

One of the central images from the Consolation of Philosophy that “Lady Philosophy” explains to Boethius is the catchy notion of the Wheel of Fortune. Far more than a cheesy game show, the Wheel of Fortune is a capricious thing that produces the bittersweetness and instability of human happiness:

With domineering hand she moves the turning wheel,

Like currents in a treacherous bay swept to and fro:

Her ruthless will has just deposed once fearful kings

While trustless still, from low she lifts a conquered head.

Here is a semi-original drink based on the Good Fortune cocktail (see p. 167), which we hereby name the Wheel of Fortune. The lemonade is the bittersweetness of chance, and the lemon garnish is, of course, the “wheel” of fortune. The drink also hides the alcohol well, which corresponds to Lady Philosophy’s observation that good fortune is deceptive while bad fortune is instructive.

![]()

Wheel of Fortune

1¼ oz. vodka

¾ oz. orange curaçao liqueur

6 oz. lemonade

1 lemon wheel

![]()

Pour all ingredients except lemon wheel into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a tall glass filled with ice (such as a poco grande or a hurricane glass) and garnish with lemon wheel.

![]()

![]()

LAST CALL

The following toast is inspired by a passage from the Consolation: “May Almighty God, through the intercession and example of His servant St. Boethius, give us the Virtues to be unmoved by the thunderous winds of Fortune, to lead a life serene, and to smile at the raging storm.” Another toast derived from the same book is “O happy would be the race of men, if the Love that rules Heaven should rule our hearts as well!”

After a few rounds, prove that you have learned nothing from Boethius and break into a rousing rendition of “Luck, Be a Lady Tonight.” But be careful: too many Wheels of Fortune, and you will turn into what Lady Philosophy calls the worldly Muses—“hysterical sluts.”

ST. RAPHAEL, OCTOBER 24 (SEPTEMBER 29)

![]()

Raphael, whose name means “medicine of God” or “God has healed,” was the archangel sent to cure the aged Tobias of blindness; to guide his only son, Tobias (also known as Tobit) on a journey; and to rescue young Tobias and his bride, Sarah, from the demon Asmodeus, who had a nasty habit of killing Sarah’s husbands on their wedding night. Raphael is also believed to be the angel mentioned in the Gospel who stirred up the pool at Bethsaida in order to heal the first person who got into it (Jn. 5:1–4). Today he is invoked as the patron of many things and persons, including travelers, lovers, eye problems, and physicians.

An ideal way to celebrate today’s feast would be with a bottle of Saint-Raphaël, a French aperitif that is made from wine, grape juice, bitter orange, vanilla pods, cacao beans, and quinine. According to the story, a Dr. Juppet was inventing a liqueur in 1830 when he lost his sight and prayed to St. Raphael. Once his sight was restored, he gratefully named his potation after the patron of the blind. Saint-Raphaël, which comes in a rouge and an ambrédoré (red and gold-amber), can be served neat, on the rocks, or in mixed drinks such as a Raphaëlle.

![]()

Raphaëlle

2 oz. St. Raphaël Gold-Amber

2 oz. pear nectar

1 lime wheel

![]()

Pour ingredients into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass and garnish with lime.*

![]()

Saint-Raphaël is almost impossible to find in the United States, although it can be purchased on the internet. An easier alternative is to mix yourself a Desert Healer (see p. 217), since Raphael was a healer who cast the demon Asmodeus into the desert. Or try a Raffaello.

![]()

Raffaello

½ oz. Galliano

½ oz. pisco brandy

½ oz. dry vermouth

¼ oz. Grand Marnier or triple sec

1 dash Angostura bitters

![]()

Pour ingredients into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into an old fashioned glass filled with ice.

![]()

![]()

LAST CALL

The Book of Tobias (or Tobit) contains one of the most entertaining stories in the Catholic Old Testament. Crack it open tonight as you sip something in honor of Raphael, “one of the seven archangels who stand before the Lord” (Tob. 12:15). Or, you can weave toasts out of two of the wedding prayers in the Book of Tobias/Tobit. “Through the intercession of St. Raphael the Archangel, may the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob be with us and fulfill His blessing in us” (Tob. 7:15). And “Through the intercession of St. Raphael the Archangel, may we see our children and our children’s children, unto the third and fourth generation: and may our seed be blessed by the God of Israel, Who reigneth forever and ever” (Tob. 9:9–11).

Wine

Douglas Green Wines, one of the oldest winemakers in South Africa, makes a St. Raphael wine, a smooth, dry red blend that is exported to the United States. Also at the bottom of the globe is San Rafael, Argentina, home to almost two hundred wineries in the Mendoza province, the country’s largest wine-producing area.

CHRIST THE KING, LAST SUNDAY OF OCTOBER

![]()

(LAST SUNDAY OF ORDINARY TIME)

In the traditional calendar, the feast of Our Lord Jesus Christ the King falls on the last Sunday of October, the date fixed by Pope Pius XI in 1925 when he instituted the feast to illustrate the relation between Our Lord’s kingship and All Saints (November 1) and to emphasize Christ’s rule here and now and not just on the Last Day. The feast was moved to the last Sunday of the liturgical year after Vatican II. Pope Pius XI saw even then that reengineering society without any reference to God was leading to moral decay, war, and a growing sense of despair. We live in a world, writes the pontiff in his encyclical Quas primas, where “nations insult the beloved name of our Redeemer by suppressing all mention of it in their. . . parliaments” and where Christ and His laws are increasingly driven from the public square. In the face of this, we must not retreat to a privatized religion but “all the more loudly proclaim [Our Lord’s] kingly dignity and power.” It was the pope’s hope that this new feast would embolden the faithful “to fight courageously under the banner of Christ their King,” to win over those estranged from Him, and to reaffirm His jurisdiction over all human society. “Oh, what happiness would be ours if all men, individuals, families, and nations, would let themselves be governed by Christ!”

Sounds like a call to action. Steel your courage with a good bracer before shouting your love of Our Dear King from the rooftops. A Rex Regum, or King of Kings, is a semi-original cocktail that suits the occasion. The Crown Royal recalls Our Lord’s kingship, and the Drambuie is steeped in Catholic history (the recipe to Drambuie was supposedly given to its current producers in 1746 by “Bonnie Prince” Charles Stuart, Catholic claimant to the English throne and grandson of the last Catholic king of Great Britain, James II). Lastly, the grenadine is a symbol of self-giving (see p. 106), perfect for our sacrificial King.

LAST CALL

A rousing Vivat Christus Rex! or “Long Live Christ the King!” is in order, either in Latin or in English. Or, if you like, in Spanish—¡Viva Christo Rey!—the dying exclamation of the great Mexican martyr Bl. Miguel Pro, whose death inspired Pius XI to establish this feast (see pp. 322–24).

The Drambuie in a Rex Regum also calls to mind the custom of the Jacobites (Scotsmen loyal to the deposed James II and his descendant Charles Stuart), who, after the exile of “Bonnie Prince Charlie,” would pass their drink over a glass of water and toast to their “King across the water.” Today, we can toast to the King above the waters, since the Son of God sits at the right hand of the Father above the waters of the firmament (Gen. 1:7).

Rex Regum

1¾ oz. Crown Royal Canadian whisky

½ oz. Drambuie

¼ oz. grenadine

¼ oz. lemon juice

![]()

Pour all ingredients into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass.

![]()

STS. CRISPIN AND CRISPINIAN, OCTOBER 25

![]()

This day is call’d the feast of Crispian.

He that outlives this day, and comes safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when this day is nam’d,

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall see this day, and live old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours,

And say “To-morrow is Saint Crispian.”

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars,

And say “These wounds I had on Crispin’s day.”

So says King Henry in his stirring speech before the Battle of Agincourt in Shakespeare’s Henry V. The real Crispin and Crispinian (also called Crispian) were brothers martyred for the faith around the year 286. The sons of a noble Roman family, they were missionaries to Gaul, spreading the faith by day and making shoes by night for financial support (hence they are the patron saints of shoemakers). They were eventually arrested, tortured cruelly, and beheaded—but only after they were miraculously preserved from two other attempts to kill them.

You will think yourself accursed and hold your manhood cheap if you do not keep this noble day. A “cobbler” is someone who makes or mends shoes as well as an iced drink made with wine or liquor, sugar, and lemon. Since we are celebrating two holy cobblers today, better make yours a double.

There are over a dozen cobbler drinks. We include two here: the Sauterne Cobbler because its name is derived from a region in France (the brothers’ adopted home) and the tasty Cherry Cobbler because its red color is appropriate for a martyr’s feast.

![]()

Sauterne Cobbler

fine sugar

Sauterne

fruits and berries

![]()

Fill an old fashioned glass with crushed ice, sprinkle sugar on the ice, and fill the glass with Sauterne. Garnish with fruits and berries.

Note: There is a difference between Sauterne, a semi-generic label for a California white dessert wine, and Sauternes, a sweet white wine from Sauternais in Bordeaux. Since the latter is too precious to be used in a cobbler, use a sweet California white.

![]()

Cherry Cobbler

½ oz. cherry liqueur (Heering, Cherry Marnier, etc.)

½ oz. lemon juice

1½ oz. gin

½ tsp. sugar

1 cherry

1 lemon wedge

![]()

Build ingredients in an old fashioned glass filled with crushed ice. Serve with a spoon for stirring.

![]()

LAST CALL

Whatever you find, raise a glass to Crispin and Crispinian for the spiritual and temporal health of us few, us happy few, us band of drinking brothers in the faith.

Cider, Wine, and Liqueur

Crispin Cider in Colfax, California, has seven different natural hard apple ciders, including one called The Saint that is made with Trappist yeasts and organic maple syrup. Bouffard (Gilles et Frédéric) and Le Domaine de la Garnière are two small wineries that operate out of the village of Saint-Crespin-sur-Moine in France, although it might prove difficult to locate one of their bottles. You’ll have better luck tracking down the highly regarded but pricey Crispin’s Rose liqueur.

ST. MINIATUS, OCTOBER 25

![]()

You can also borrow a drink from St. Miniatus, also known as St. Minias, who is revered as the first Christian martyr of Florence. It is believed that Miniatus was either a soldier in the Roman army or a member of Armenian royalty on pilgrimage when he was martyred in AD 250.

Whatever St. Miniatus’s background, he would surely appreciate a Negroni, one of Florence’s most famous cocktails. Invented by Count Camillo Negroni in 1919, it is usually served as an aperitif. As Orson Welles once put it, “The bitters are excellent for your liver, the gin is bad for you. They balance each other.”

![]()

Negroni

1 oz. gin

1 oz. sweet vermouth

1 oz. Campari

1 orange twist or slice (for garnish)

![]()

Pour all ingredients except the orange twist into an old fashioned glass filled with ice and stir until very cold. Garnish with orange twist.

Note: Some bartenders like to increase the amount of gin, or you might want to reduce the amount of Campari, which is quite bitter.

![]()

![]()

STS. SIMON AND JUDE, OCTOBER 28

![]()

Sts. Simon and Jude were both chosen by Our Lord to be among His original twelve Apostles. Both, it is believed, were martyred in Persia after Simon had preached the Gospel in Egypt and Jude in Mesopotamia. Simon is called the Zealot in the Bible either because he belonged to a virulently anti-Roman Jewish sect by that name or because he was zealous in following his new Master. Jude Thaddeus is the author of a brief and strongly worded New Testament epistle that mentions, among other things, the curious detail that St. Michael the Archangel and the Devil fought over the remains of Moses (Jude 9).

But St. Jude is most famous for being the patron saint of desperate or hopeless causes. This role is relatively recent, dating back to 1929 when a Father James Tort, CMF, encouraged the devotion to his parishioners in southeast Chicago, most of whom were laid-off steel workers. The devotion grew rapidly, and on the final night of a solemn novena held on St. Jude’s feast, there was an overflow crowd outside the church of a thousand people. The next day, the stock market crashed, and soon more Americans were turning to St. Jude during the Great Depression and World War II. There isn’t much else to tie St. Jude to hopeless causes, although it has been speculated that because of the similarity of St. Jude’s name to Judas Iscariot’s, people wouldn’t pray to the “forgotten Apostle” unless all else failed!

Regardless of how he got the job, St. Jude is now an everyman’s saint. And for an everyman’s saint, have a Desperado No. 1, a cocktail that is evocative of a working-class Boilermaker (see p. 103) as well as St. Jude’s patronage of desperate causes. (Fittingly, like the modern devotion to St. Jude, “desperado” is an American invention rather than an authentic Spanish noun.)

At the opposite end of the social spectrum is the Desperado No. 2.

LAST CALL

Turn a popular prayer to St. Jude into a toast, and toss in his fellow Apostle St. Simon: “To Sts. Simon and Jude, and may the Sacred Heart of Jesus be adored, glorified, loved, and preserved throughout the world now and forever.”

![]()

Desperado No. 1

1 beer

2 oz. tequila

1 dash lime juice

![]()

Build all ingredients in a pint glass and serve.

![]()

![]()

Desperado No. 2

2 oz. Patrón Añejo tequila

¾ oz. sweet vermouth

½ oz. amontillado sherry

¼ oz. Cynar

1 orange twist for garnish

![]()

Pour all ingredients except orange twist into a shaker filled with ice and shake forty times. Strain into a cocktail glass and garnish with orange.

![]()

![]()

In the early Middle Ages the Church in Ireland adopted a number of practices from the Celtic festival of Samhain (the Lord of the dead in Celtic mythology) on October 31. The Druids believed that infernal spirits roamed freely on this night and responded to this threat according to the principle “If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.” Consequently, they disguised themselves as various kinds of phantoms to escape harm and tried to appease evil spirits by offering them food and wine.

The Church was gradually able to wean the Celts from their heathenish ways, replacing their ghoulish camouflage with pious masquerades of the angels and saints in processions on All Hallows’ Eve and substituting their food offerings with “soul cakes” that would be made on Halloween and offered to the poor in memory of the faithful departed. (This was centuries before the Western Church instituted November 2 as All Souls’ Day.) From these two observances come our modern Halloween costumes and trick-or-treating.

But back to soul cakes. The original intention of “souling” was doubly charitable, ensuring that the poor would be fed on this day, in exchange for which the poor would pray for the donor’s dead. Eventually, the practice became more frolicsome as groups of young men and boys began going from house to house and asking for food, money, or ale in addition to cakes, as is attested by various “Soul Cake” songs that have survived from olden times. Here are some relevant verses:

LAST CALL

You heard the soulsters: it is time to respect souling. Different versions of the song are easy to find on the internet. Learn one and then break out the brandy and the beer as you toast to the saints and pray for the dead.

There are legions of beers and other beverages named after the realm of the infernal and its fiendish inhabitants that you can commandeer based on the Christian principle “To the victor go the spoils.” Two “diabolic” cocktails mentioned in this book are the Black Devil (see p. 256) and Satan’s Whiskers (see p. 115). Or have something from All Saints’ or All Souls’ Day (see below).

And if you are going trick-or-treating with your children, you can always do what my father did, which was to bring along an empty shot glass. As the kids were being given candy at the house of a friend, my dad would grin and hold out the glass. The highly amused host or hostess would then fill it up with whatever was on hand. (Don’t worry: we didn’t have that many friends.)

Here comes one, two, three, jolly boys, all in a mind.

We are come a-souling for what we can find.

Both ale, beer, and brandy, and all sorts of wine.

Would ye be so kind, would ye be so kind?

We’ll have a jug of your [best old March] beer,

And we’ll come no more souling till this time next year.

With walking and talking we get very dry,

I hope you good neighbors will never deny.

Put your hand in your pocket and pull out your keys

Go down to the cellar and draw what you please!

Give us cakes and ale and good strong beer

And we’ll come no more souling until next year!

![]()

* There are more cocktail ideas on the company’s website: http://www.straphael.fr/gb/theproducts/cocktails/cocktails.html.