Chapter 6

Root Beliefs

Procrastination, like other problem behaviors, often results in regret. Faced with a missed deadline or lost opportunity, how many of us have complained, What was I thinking?

Chances are when you procrastinate you are thinking something along the lines of I’ll do it later; there’s plenty of time; or I can’t do it now because… These are typical task-avoidant thoughts, thoughts that rationalize why the task can wait. Task-avoidant thoughts not only justify postponing the immediate task, but used often enough, they also keep you from achieving your larger goals. You won’t pass your driver’s test, get a summer job, or get into college thinking, I’ll do it later.

Task-avoidant thoughts are unreliable guides for our behavior; however, they form in our heads so quickly and automatically, and in such variety, that it is very difficult to challenge them one at a time. In working with clients, I find it most effective to dig a little deeper at the roots of the tree, where we’ll find the beliefs, often hidden, that feed our task-avoidant thoughts. These root beliefs are at the heart of the procrastination problem.

Let’s revisit our four procrastinators and examine the root beliefs that are unique to each type, and the task-avoidant thoughts that spring from them.

The Perfectionist

Jordan was in a panic over his English term paper, a critical essay of The Sound and the Fury, which, according to him, was “the most challenging book I ever read.” The questions he had to address about the author’s use of stream of consciousness, or the themes of lost reputation and religious faith, weren’t the kinds of things Jordan, who excelled in subjects like algebra and Spanish, normally thought about. Althought it wasn’t his strongest area, Jordan was certainly smart enough to write the essay. I asked him what would happen if he just wrote what he was thinking.

“I could get it wrong,” Jordan answered. “I don’t know what the teacher wants to hear.”

Me: What would happen if your teacher thinks you’re wrong?

Jordan: She’ll give me a bad grade.

Me: And then what would happen?

Jordan: I could get a C in English. Do you have any idea what that would do to my GPA?

Me: And if your GPA went down?

Jordan: I won’t get into a good college. Everyone will know I’ve failed.

Jordan’s root belief was now in plain sight. He thought that if he made a mistake he’d be a failure and lose the respect of others. To secure his standing in his tribe, Jordan operated under the principle I must not make mistakes.

This is the underlying belief of all perfectionists. It colors all your thoughts, raising the stakes for even the simplest of tasks. In the branches of the thought tree illustration on page 37 are some of the task-avoidant thoughts that are triggered whenever you are faced with a task that you aren’t sure can be done perfectly. As the illustration shows, a tree with roots and branches like this is bare. When the only work you can display is what turns out perfect, there won’t be much to show.

But might not these task-avoidant thoughts be accurate? Could Jordan’s root belief be true in this situation?

Possibly. Jordan could write an essay that his teacher would grade low enough to drag down his entire GPA—downgrade it so much that he couldn’t get into a decent college. Jordan couldn’t be sure. What Jordan could be sure about was that the longer he continued to act on his root belief and its task-avoidant thoughts, the less time he’d have to complete, and hopefully excel at, the essay.

Exercise: Identifying Your Task-Avoidant Thoughts and Root Beliefs

- Think of something you have been putting off and write it down. This may be a chore, an assignment, talking to someone about something, physical exercise, or another type of self-care.

- Now ask yourself: Why don’t I get started right now? If I did start, what am I afraid of? What’s the worst thing that could happen if I started right now? List the first answers that pop into your mind. These answers will most likely be your task-avoidant thoughts.

- Once you have a few thoughts listed, circle one of them that feels especially true or upsetting, or both. (Jordan’s most upsetting thought was that he might get a bad grade.)

- Ask yourself, If this thought came true, what is the worst thing this could mean about me? About my life? About my future? Write down the answers.

- Repeat step 4 until you have identified the belief at the root of your thought tree.

To help you do this exercise, download the Root Beliefs worksheet at http://www.newharbinger.com/35876.

The Warrior

On Thursday after school Emily decided to clean her room. Her friends were coming over for a sleepover on Friday, and she wanted to have a comfortable space for them. But then there was a post about a YouTube video on rock climbing and that, of course, couldn’t wait. After the video, she noticed she was hungry and thought, I’ll have more energy if I eat first. Then she got a call from a girlfriend about a sale at the mall. Plenty of time to clean my room, Emily thought. When she got home from the mall, her mother chastised her for missing dinner with the family again. Emily felt agitated. Cleaning her room didn’t sound so appealing, and when she got a text inviting her to play with friends online, she thought, I’ll chill with a game for a while first. A couple of hours later, Emily realized it was bedtime. Well, I’m too tired now. I’ll clean up tomorrow right after school. In the end, Emily shoved everything under her bed and into her closet minutes before her friends arrived.

As long as stimulating activities were available, Emily didn’t feel motivation for tasks that didn’t engage her fully. Yet she genuinely wanted to have a clean room for her friends. What was the root belief stopping her from focusing on what she needed to get done? To find out, I asked Emily what would happen if she cleaned her room first, rather than watching the video.

Emily: I know that when I don’t feel like doing something, I don’t do it well. I really wanted to see the video and post it to my rock-climbing friends. I’d feel like I was missing out on that.

Me: And what if you had continued with cleaning your room despite these concerns?

Emily: I would have felt bored and irritated and that I was missing out.

Me: And if you had kept cleaning the room anyway?

Emily: I just couldn’t. Watching the video felt more important, and it wouldn’t take long. Cleaning the room would have taken hours, and it didn’t have to be done until the next day.

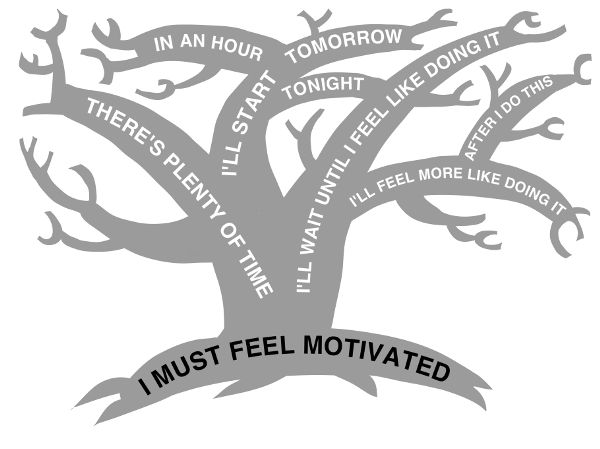

Emily’s root belief was starting to reveal itself. Emily thought that feeling a sense of excitement about an activity meant it was more urgent. To warriors like Emily, tasks and activities that are stimulating and engaging take priority over those that aren’t. Emily thought, at least unconsciously, that if a task didn’t motivate her, it wasn’t as important as whatever did. Like all warriors, Emily’s root belief regarding tasks was I must feel motivated.

The belief that feeling motivated toward a task or an activity makes it a priority distorts all the warrior’s thinking, giving rise to justifications for putting off anything that isn’t fully engaging. Here is an illustration of the warrior’s thought tree.

Those other activities felt so important to Emily that she postponed cleaning her room. Might they be more important? Posting about the YouTube video immediately might have given her more status with her rock-climbing friends. She enjoyed her snack, saved money at the mall, and totally dominated at her video game. Perhaps those were special experiences that couldn’t be had again. Emily couldn’t be sure whether having a clean room for her friends would have been worth missing those experiences or not. All Emily could be certain about was that as long as she believed I must feel motivated, she would continue to engage in whatever activities fully engaged her, postponing tasks that did not—even tasks important for her personal happiness.

The Pleaser

Athena came in to session one week with a downcast look and a slumping posture. Three weeks earlier, she had told her boyfriend she’d go camping with him and some of their friends. But she hadn’t asked her parents for permission yet, and the trip was the next day.

Athena would not have put herself in a situation like this unless one of her core values were threatened. To help her discover what that core value was, I invited Athena to join me in a question and answer exercise. Note how each question I ask brings Athena a little deeper into her fear. This exercise the downward arrow.

Me: What would happen if you talked with your parents?

Athena: They’ll be upset with me going on an overnight with my boyfriend, even in a group.

Me: And if they get upset, what would that mean to you?

Athena: They’ll say no. And that I should have approached them right away, before it’s all planned and everything.

Me: And if that were true, what are you afraid will happen?

Athena: I’ll have made them angry and my boyfriend angry that I can’t go.

Me: And if this is true, what will it mean to you?

Athena: Everyone will hate me! I’ll feel alone!

Clearly, Athena’s core value was threatened. She believed that to maintain her connection with her parents and her boyfriend she needed to keep them happy. Athena’s root belief was If I displease others I love, I will be rejected.

The unconscious belief I must not displease others acts as a wellspring for the thoughts that come to mind automatically whenever you are faced with the possibility of disappointing anybody. On the following page is an illustration of the pleaser’s thought tree.

As a pleaser, you can never be completely certain that displeasing others won’t result in them rejecting you. What Athena could be sure of was that the longer she acted on her underlying belief I must not displease others, the more potential strain she was putting on her connection with her parents and her boyfriend.

As a pleaser, you can never be completely certain that displeasing others won’t result in them rejecting you. What Athena could be sure of was that the longer she acted on her underlying belief I must not displease others, the more potential strain she was putting on her connection with her parents and her boyfriend.

The Rebel

Tyler came into a session very upset. He’d just been graded a 70 on his history term paper even though, in his words, it was genius work. I didn’t doubt him. Tyler was undeniably clever.

Tyler’s issue was the teacher’s requirements for notating references and providing a bibliography. Documenting his research seemed unnecessary to Tyler, something that would just slow him down, so he kept putting it off. When the due date arrived, it was too late to reconstruct everything and he had to turn in the paper incomplete. “Why do teachers have to put such ridiculous restrictions on us?” Tyler asked. “All it does is make it impossible to write anything good!”

This example of underperformance was typical for Tyler, who belonged near the top of his class but was in danger of failing several subjects. Tyler’s resistance to following instructions was keeping him from getting credit for his creativity and intelligence. To find out what was causing that resistance, I asked him what would have happened if he had tracked his references at the start.

Tyler: I would have felt stupid. Doing busywork just because someone wants you to is demeaning.

Me: What if you went ahead and did it anyway, even though it was demeaning?

Tyler: I couldn’t respect myself. I’m not a slave to be ordered around.

To Tyler, cooperating with an assignment that didn’t make sense to him was equivalent to enslavement. With his personal independence at stake, it’s easy to see why he resisted the task. Like rebels everywhere, Tyler believed that if he followed orders from others he would be subservient to them. If he wasn’t in control of the task, he would be taken advantage of and diminished somehow. Tyler believed, I must not give in to others.

Believing that allowing someone to lead you threatens your independence will make all assigned tasks look daunting. Here is the thought tree of the rebel.

Would Tyler have lost some self-respect and integrity by doing his history teacher’s “busywork”? In his own mind, yes, but how long that would last is unknown. What we do know is that if Tyler keeps believing that he must be in control of a task in order do it, his grades will continue to suffer, making his path to independence all the more difficult.

Procrastination is not a sign of weakness, poor character, laziness, or failure. Procrastination is a normal human reaction to tasks that challenge our core values. When the perfectionist is faced with a task where he could fail, the perfectionist’s core value—excellence—is threatened. When the warrior tries to do something without feeling motivated, his core value—full engagement—is threatened. When the pleaser wants to say or do something that might displease or disappoint others, her core value—connection with them—is threatened. When the rebel is given a job that makes her feel controlled, her core value of independence is threatened.

When your core value is threatened, your root beliefs are activated. These beliefs are what feed the task-avoidant thoughts that rationalize your behavior.

Acting in accordance with task-avoidant thoughts and their root beliefs may seem to protect our core values, but it can make matters worse. What makes these thoughts so powerful? Why do we keep thinking we should avoid tasks that we know we’ll eventually have to face? In the next chapter, I’ll answer these questions by revealing the powerful dynamic that keeps us returning to the same short-term solution.