Chapter 7

Chapter 7

The Procrastination Cycle

I must not make a mistake. I must feel motivated. I must not displease others. I must not give in to others. These root beliefs, examined in the light of day, don’t appear so reliable. One might ask: If our root beliefs aren’t necessarily true, and they point us away from our goals and values, why do we believe them?

Root beliefs have something going for them that ordinary thoughts don’t have. They feel true. If it feels to you like a task might impede your quest for excellence, be unengaging and tedious, threaten your socials connections, or compromise your independence, you are going to want to put that task off.

What we’re feeling when we think about a task is emotion. Emotions help us know whether it is safe or beneficial for us to proceed. Positive emotions about a task tell us All’s clear, full steam ahead! Negative emotions are a signal that something is wrong. They act as enforcers of our task-avoidant thoughts.

If there is the risk of failure at a task, the perfectionist feels fear, anxiety, or perhaps confusion. These emotions enforce the task-avoidant thought I’ll do it when I’m clearheaded.

If a task isn’t engaging, the warrior feels bored, irritated, and restless. These emotions enforce the task-avoidant thought It’s not that crucial that I get it done now.

If doing a task may displease a loved one, the pleaser feels apprehension, guilt, and shame. These feelings enforce the task-avoidant thought I’ll take care of them first; my needs can wait.

Procrastination delivers immediate relief from negative emotion, which acts as a reward for the behavior.

If a task is assigned condescendingly or seemingly makes no sense, the rebel feels helpless, confused, and angry. These emotions enforce the task-avoidant thought This is stupid; I’ll do it later.

In the short term, procrastination delivers what you want most—immediate relief from a negative emotion. This quick relief acts as a reward for our behavior. When we are rewarded for putting off a task, we are more likely to put it off again the next time it appears.

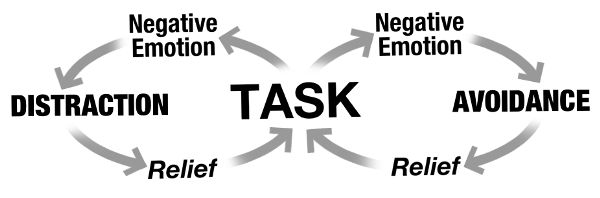

Procrastination can be explained as follows:

- You think about the task, which

- triggers root beliefs and accompanying negative emotion, which

- triggers task-avoidant thoughts, which

- causes you to put off the task, for which you are rewarded with relief.

And when we factor in that other powerful agent of procrastination, distraction, we get into even more trouble. Distracting activities, like watching a movie or using social media, not only ease the negative emotions associated with the task but also elicit positive emotions, which makes putting off the task doubly rewarding.

Avoidance and distraction are the two complementary components of procrastination. When we are simultaneously pushed away from essential tasks by our negative emotions and pulled toward pleasant activities that make us feel good, we have a pretty lethal combination. I call it the procrastination cycle.

Neutralizing negative emotions and cultivating positive emotions isn’t wrong or weak or stupid. For thousands of years, emotions have served us as reliable survival guides. The wild animal’s howl or roar frightened our ancestors, warning them to stay alert. The chirping of crickets told them it was safe to relax. Neutralizing negative emotions and fostering positive ones is business as usual for human beings, and you are no exception.

The system fails when you’re faced with a task that triggers negative emotions but is also crucial to your well-being. Putting off an essential task triggers secondary negative emotions that are just as difficult to neutralize as the ones you’re temporarily relieved of. With procrastination, everything, including pain relief, is temporary.

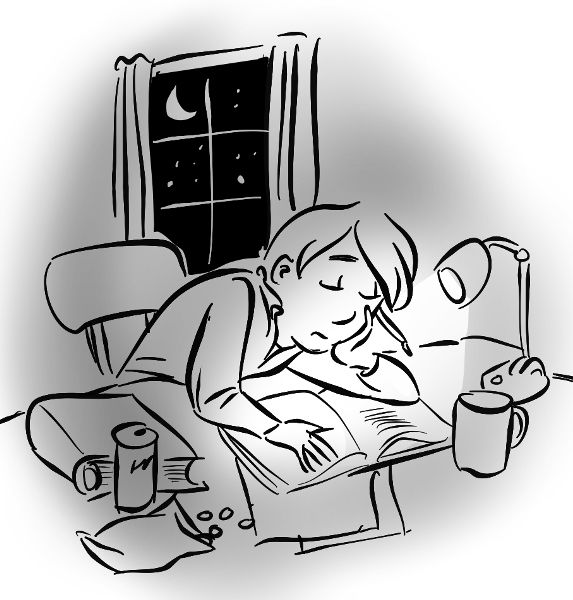

For example, studying for an algebra exam can threaten the perfectionist with the possibility of errors, bore the warrior, or, because it doesn’t seem relevant, irritate the rebel. But if you avoid or distract yourself from studying, secondary emotions emerge. No amount of distraction can make you completely forget the upcoming test, and you are haunted by guilt and dread. Your postponed pain culminates on the night before the exam when, in addition to those two feelings, fear and panic set in. No amount of avoidance and distraction will work at this point. The only way to neutralize these emotions is to perform last-minute heroics, like pulling an all-nighter before the exam.

Although you can push a task to completion by harnessing your fear and panic as the deadline approaches, and you may pass the test, you have merely interrupted, not disrupted, the procrastination cycle. The next time the task of studying algebra arrives, you’ll experience the same negative emotions and tendency toward distraction. Your underlying beliefs will still be intact. I must not make a mistake, I must be stimulated, I must be in control. The cycle is primed and ready for more repetitions.

Repeated failure to complete essential tasks on time and up to your ability will trigger deeper secondary negative emotions: frustration, regret, inferiority, anger with yourself, and worst of all, shame and depression. These are the most damaging and the longest-lasting consequences of procrastination. Sadly, when you’re feeling ashamed and depressed, you cannot enjoy whatever excellence, social connection, stimulation, and independence you may have acquired already. And as long as you act on your underlying beliefs, you will be frustrated in your goal.

Now that we’ve examined the core values, root beliefs, negative emotions, and behaviors that drive the procrastination cycle, we are ready to address what can be done about it. Each of the following chapters outlines a powerful tool that will help you master not only your procrastination but also your life. These tools will help you challenge your root beliefs, cope with negative emotions, and organize your difficult tasks to make them more manageable.

Of course, tools are only powerful in the hands that use them, and you’ll need to be motivated to use them. One of the ironies of a self-help book about procrastination is that anything the author asks the reader to do is by definition a task, and breaking the cycle of procrastination is a big one. You have a lot of momentum going around and around the cycle, and it will require real thought and energy to change. You may be thinking, There are enough things in my life waiting to be done. Don’t give me any more!

Because of this, I fully expect that some of you will decide you’ve done enough about the problem by reading this far, and that for now, your procrastination problem is manageable. You might even be thinking, I’ll work on my procrastination problem later.

That’s okay, because I firmly believe that while everyone has the potential to beat procrastination, you cannot do so unless you decide for yourself that the problem is one you’re determined to tackle. That’s why the next chapter is about recognizing when and whether completing a task will support your core value(s). Uncovering this personal incentive is the crucial first step to disrupting the cycle, and it will inspire you to do what you need to get done.