4

Core Principle 2: Engage the organization

André Dua, Charlotte Relyea, David Speiser

Why organizational journeys? | Elements of engagement: breadth, depth, pace | Implications for leadership development | The increasing velocity of journeys | A short note on resourcing

Today many leadership development programmes are episodic – they focus on only a subset of the organization, and do not move quickly enough. Sustainably shifting leadership behaviours across an entire organization, however, requires an effort of the right breadth, depth and pace. Any leadership development programme must bring about change across an organization, not merely in isolated parts, and reach a critical mass of pivotal influencers across all levels of the organization quickly. In order for this to happen the programme must be appropriate to the organization and rationally conceived and executed; moreover, it must be culturally attuned to the organization. Its acceptance (and therefore success) depends on a general understanding across the organization of what great leadership looks like, and, for some, what the best leadership feels like.

Our Core Principle 1 attends to the critical shifts in a leadership development programme and links these to the organizational context and to the creation of value; in essence, this is the ‘what’ of the leadership development programme. Core Principles 3 and 4 deal respectively with the ‘how’ of leadership development at the individual and the organizational level.

Here, in Core Principle 2, we look at the ‘who’ of leadership development. This principle is based on the concept of engaging the organization. It addresses the matter of who should participate in leadership development, under what conditions, how often, and for how long. This is the way that the organization engages individuals across its structure (we call this breadth), the nature, frequency and duration of the development (we call this depth) and the speed at which the programme is initiated and rolled out (we call this pace).

Core Principle 2: Engage a critical mass of pivotal influencers across the organization to reach a tipping point

Organizations must ensure sufficient breadth, depth, and pace in order to change leadership behaviours across the organization, and to give all employees an understanding of what great leadership looks like

Why organizational journeys?

Why, then, is it necessary for an organization and its leadership development programmes to engage closely and mutually? There are two bodies of evidence that show the importance of engagement and the organization-wide view that it implies: our research, and our experience in delivering leadership development programmes (equally we note where a lack of these can disable or render ineffective the best-intended of programmes).

First, the research. There are several striking insights from our research that inform the elements that make up what we might characterize as the organizational journey in leadership development – in other words, how does the organization engage with its leaders and influencers over time? Those organizations that succeed in their efforts are much more likely (a likelihood measured in multiples of 5 to 7 times) to structure their leadership development programmes along the thinking that we set out as the organizational (as opposed to individual) journey.

For example, we know that organizations with successful leadership development interventions are 6.9 times more likely to cover the whole organization and design programmes in the context of the broader leadership development strategy. We also know that organizations with successful leadership development programmes are 6.4 times more likely to ensure that their leadership strategy and model reaches all levels of the organization.

This idea of what we might call an organizational journey for all participants is supported by two more data from our research: organizations with successful leadership development programmes are 4.6 times more likely to assess the leadership status gap (and the reasons for it) at all levels of the organization; and organizations with successful leadership development programmes are 4.9 times more likely to model the desired behaviours in their top teams and beyond, as senior people become formally and informally involved (as speakers, faculty, mentors) in the development programme.

The above points cover the importance of ‘breadth’ (that is, ensuring the leadership development interventions reach a critical mass of influencers in the organization). In addition, research shows what that adequate ‘depth’ (in terms of how people are engaged on a leadership programme) is required for a sufficient amount of time. Capabilities are not built overnight, and people need sustained time and touch points to develop them.

Unfortunately, the vast majority (81 per cent) of leadership development programmes take place over 90 days or less; and a mere 10 per cent run for more than six months.1 Organizations are spending too little time over too short a period on leadership development, which does not allow participants to reflect on and trial their new skills, and time for the supportive effect of cohort-behaviour to have an impact. The impact shows: 41 per cent of successful leadership development programmes are over two months, while only 25 per cent of unsuccessful programmes have a similar duration, and successful programmes are on average more than 35 per cent longer duration than unsuccessful ones.2

Second, what we know from our practical experience. The most impactful leadership programmes that lead to a visible shift in daily leadership behaviours and bottom line impact always entail organization-wide thinking. These programmes reach far into the structure and culture of the organization, initially focusing on a critical mass of leaders, and over time reach a tipping point and shift the behaviours of all employees. To do this, the programmes also have sufficient depth and pace, with 12–18 months spent on each wave of desired shifts in order to ensure real transformation. We even see some organizations where leadership development is never an ‘intervention’ but rather a part of the steady state business processes. GE, for example, equates leadership to the ‘plumbing in a house’, and leadership development therefore occurs on an ongoing basis, with a clear leadership journey for top talent at all levels of the organization.

Unfortunately, we often see the opposite: leadership development is delegated many levels down the organization, without the necessary support from senior organizational leaders; the top managers do not ‘walk the talk’ and either disengage personally or embark on a superficial leadership journey themselves. We see leadership development efforts that are narrow in application across the organization and are shallow for the individual: cohort-specific episodes instead of organization-wide engagement.

Organizations such as professional services or the military understand that leaders must be apprenticed and grown from within their organization. They devote time, energy, people and money to develop their leaders (and influencers) over long periods. This approach produces a sustained developmental journey for the individual leader, a planned and secure supply of leaders for the organization, and an organization-wide leadership culture.

Elements of engagement: breadth, depth, pace

A number of factors readily emerge in successfully engaging the organization. We see repeatedly the effect of a ‘critical mass’ where sufficient numbers of leaders and influencers are behaving in ways consistent with the desired strategy – setting the way for others. Equally we see the importance of sufficient range and density of leaders from disparate parts of the organization behaving in new ways such that their own new behaviours are reflected back at them – their sense of themselves as changing derives from seeing others’ positive reactions to them. (The opposite reaction bears significant risk – we sometimes see leaders returning from a programme full of energy, only to be disappointed by the lack of enthusiasm shown by those colleagues who did not join the programme for the new way of working; these leaders often revert back to their old way of working, lose enthusiasm and, in the worst cases, leave the company.)

Moreover, there have to be sufficient numbers of more senior leaders who can talk about change that the leadership development programme is bringing about; they will play a role in the formal processes (performance review, staff appraisal, 360-degree review) that reinforce the new leadership behaviours. Their roles also contribute the broader culture that sustains the changes brought about by the programme. There is, for example, a positive effect of cohort classes as sufficient leaders across the organization meet and form working relationships with each other based on a common leadership development experience.

The journey must be pursued with sufficient intensity and over sufficient duration as well. Many leadership development programmes are episodic and sporadic, for example covering only one cohort (or one individual) at a time, for a two-to-three-week period. We see such episodic and sporadic leadership development efforts fail not only because they are undertaken without being part of a broader effort, but also because the components of the programme are insufficient in themselves to bring about meaningful change. Additionally, interventions should have adequate pace and energy. If not, momentum is lost, learning is squandered, and the broader organization can become frustrated by the lack of visible change.

As such, engaging the organization entails three elements:

• breadth (the numbers of those involved in a programme)

• depth (the frequency and nature with which participants are involved and kept involved)

• pace (the speed of the initial rollout of the programme).

These three elements help ensure the intervention transforms a critical mass; and this critical mass then creates a tipping point in behavioural change across the organization. In practice, this means transforming a critical mass of leaders (through breadth, depth and pace) at all levels within an organization. When sufficient numbers of leaders display the new behaviours, a tipping point is reached, the change becomes self-sustaining and the organization is transformed. We discuss the three elements of depth, breadth and pace in more detail below.

Breadth

The breadth of a leadership development programme is the extent to which it involves people across and down the organization. The key question here becomes: How much is enough? There are many ways to answer this. One of them is through the lens of network theory, an interdisciplinary body of work that unites thinking from maths and physics, anthropology, social science, communications and, above all, epidemiology. They can be applied to all spreading phenomena in biological, digital and social networks. The organization is a complex mix of the latter two.

In networks there are many determinants of size, speed and quality. Network size can be measured by nodes and network thinkers tend to distinguish between static networks like railways and scale-free networks like the internet. Network speed (or speed of growth or information within a network) can be thought about in terms of epidemiology: here, network thinkers arrive at a transmission or diffusion rate based on probability of infection and frequency or density of connection, and in terms of susceptibility and recovery rates. And in terms of network quality, social networks theorists tend to talk of weak ties, structured holes, super-spreaders. Often the most engaging thinking bridges the disciplines, so a physicist can write of contagion: ‘in scale free networks even if a virus is not very contagious, it spreads and persists’.3 A network view of the organization can really help shape how we think in practical terms about the organizational journey.

Social change theory that derives from evolutionary theory and sociology is another way to see the element of breadth, and can augment thinking about why as well as how change takes place.

Yet another way of thinking rests on looking at the moment that a critical mass is reached in a network: Malcolm Gladwell’s synthetic view in The Tipping Point focuses on ‘the moment of critical mass, the threshold, the boiling point’.4 He coins the phrases the ‘Law of the Few’, the ‘Stickiness Factor’ and the ‘Power of Context’, which deal with the messenger, the message and the context respectively.

Other bodies of thought focus on team or individual agency. John Kotter’s long-standing work on organizational change, for example, posits that all change must be led by a team that has the right amount of power, expertise, credibility and leadership.5 As for individual agency, it is now possible through measurement of communications and network analysis, to map the extent and value of an individual’s interactions.6

We have looked at the individuals who make up the network that might carry a message. How does the nature of the message itself affect how far (and fast) it travels? The idea of ‘stickiness’ here is important,7 alongside the extent to which a leadership change message is radical, conservative, expected or unexpected. Here, more traditional corporate communications thinking has a bearing on how the leadership development programmes are advertised and launched on the organization.

Anthropological thinking can add value here, drawing on the idea of a message, behaviour or style that spreads from person to person within a culture – a meme – that takes on an independent life (rather like a gene in genetic theory) and is shaped by variation, mutation, competition or inheritance.

Another element that plays a vital role in the leadership development journey is the state of the organization. Here, the urgency, the timing, the resources, the physical disposition and the state of readiness of an organization can all enable or disable a leadership development effort.

The nature of an organization, and its sector, can have a marked influence on how successful a leadership programme might be: for example, public sector organizations tend to have different governance structures that promote wide (and time-consuming) consultation; FMCG organizations tend to drive change quickly and see the immediate results of changes; and extraction and utilities organizations have operational and safety priorities that might have a practical effect on how and when a cohort can be assembled.

Equally, organizations vary in size and in the disposition of their workforce; retailers and manufacturers tend to have a smaller critical mass as a percentage of the overall workforce; knowledge-based organizations, which tend to have high degrees of autonomy throughout the workforce (indicating a high degree of leadership at all levels) and tend to have a higher critical mass that must change.

Together, these three perspectives – messengers, message and context – make up the full picture in thinking about reach. Larger organizations (30,000–50,000 people) typically work with a top 250–750. This is around 1 per cent of their organization, a manageable size for ‘senior leadership’ positions. However, we find that this is not enough; while critical, it does not go deep enough into the organization. In our experience we find that 5–15 per cent is needed, depending on the organization. This is also roughly what constitutes ‘top talent’ across all levels in many organizations.

However, it makes sense to consider again the purpose of any leadership development programme: is it to develop all leaders, or only those leaders who are in roles that produce value, or who are vital to operations? In a properly staffed organization all leaders have a role to play, but perhaps not equally vital at all times. Similarly, it can be argued that only a subset of leaders actually need the development programme, because – as numerous studies have shown – only truly excellent leaders matter as they drive a disproportionate amount of performance and impact.8 The question is therefore: How do you move individual leadership excellence to overall organizational leadership effectiveness? The answer – the organizational journey – is to ensure an organization-wide understanding of what great leadership looks like. The remaining 85–95 per cent of employees then have clear role models in terms of the desired leadership behaviours, and their understand and adoption of these behaviours can be further supplemented by targeted capability building efforts, communication and incentives alignment (more on this in Chapter 6).

Leaders change roles, too. So we believe that the purpose of any leadership development programme should be to increase leadership effectiveness across the organization. Leadership development, then, must start at the CEO and top leaders, but then move down to the 5–15 per cent pivotal influencers in the organization. Pivotal influencers are able to influence the behaviours and thinking of others in the organization, due to their role, a trusted relationship, or character. These influencers include the CEO and top team, top talent, influencers and pivotal roles (such as branch managers and plant managers), which may not necessarily be high in the organizational hierarchy. Timing and positioning are vital: starting at the top is sufficient at the outset, but you need to rapidly move through the organization.

However, some people are more influential than others, and change happens best when the most influential are appropriately distributed: not too thinly to be lone voices, and not too densely to become a choir without an audience. There is therefore a need for pockets of critical mass equally across hierarchies. In every unit/critical area, there is a minimum group that can support each other (with sufficient power – here tipping point theory and social change theory apply). For example, at one multinational organization with 50,000 employees, we engaged the top 2,000–3,000. Half of those 50,000 were actually engaged in operations and not in the customer-facing roles we sought to influence; hence were engaging around 10 per cent of those we sought to influence.

Depth

The organizational journey cannot be developed overnight. Building a repertoire of leadership capabilities takes time. A new behaviour must be practised repeatedly in order to develop into a capability, a competence. But most leadership development programmes do not think about leadership development as multi-year or multi-decades journeys in which several competencies are built over time. Instead, most leadership development programmes are typically of short duration – a few weeks to several months, sporadic and piecemeal. Moreover, many tend to focus on the ‘flavor of the year’, on whatever aspect of leadership that is perceived to be most fashionable now. The consequence is that efforts are not aligned to the critical shifts that will improve performance, and new insights and behaviours never develop into competencies.

The depth of a leadership development programme suggests a longitudinal approach: How often and to what extent are individuals reached by the programme? A typical leadership development programme might draw together a cohort of people for classroom forums. But this is to see learning in a narrow way. Participants learn primarily by doing. So we tend to look at leadership development from the perspective of what can be achieved through daily work rather than through non-work. Learning is working and working is learning; therefore to account for learning on the job we say the ideal time is 250 days given that there are appropriate interventions and curriculum content. Leadership, after all, is learned through leadership, not sitting in a class. In fact, we are in training 100 per cent of our time. If we want to be successful in growing leaders, we need to make sure our learning interventions are embedded into our work. They are coached on the job. They can take a digital course to help them on a problem they have at the job. They then solve the problem and, in and by doing so, learn new skills, including those of leadership. This learning on the job ideally sits within a culture of delegation and support, so that people develop on a daily basis. We will return to the link between leadership development and culture in Chapter 6.

While embedding a culture of development (‘250 days of learning’) is an important foundation to think about leadership development (and learning in general), many organizations benefit from additional, more structured leadership development interventions – for example when rolling out a new or revised leadership model. While ‘stretch’ accounts for the learning that takes place within work, it is also vital to allow time for reflection and peer learning in order to consolidate the progress that has been made. In addition, the time on a development programme spent in classroom or more formal locations can provide new ideas and stimulate the other portions of learning.

The question then becomes: what does this journey look like? As we discussed in the previous chapter, the leadership model should be adapted to different organizational career paths and levels. An individual on a specific career path should have a clear view of the leadership expectations as they become more senior in the organization. In parallel, the leadership development interventions to help them meet these expectations should follow suit. This often manifests itself in a multistage journey. For example, one organization delineates its major ‘leadership pipeline’ along four main stages: manager, general manager, director and VP. Each stage on average takes four to six years. New top talent at each stage (for example new hires or people who have been promoted) go through a structured leadership development intervention, while other top talent who have already completed the stage’s main leadership programme are given stretch assignments on the job, mentoring and formal yearly ‘refreshes’.

To be more precise, within each stage on a leadership journey, we advocate a field, forum and coaching approach over an extended period of time, covering learning on the job (field), work-based projects (field), structured reflection and stimulation (forum) in an environment discreet from work, and coaching and mentorship (coaching). What we typically see working well in terms of days (broadly speaking) is roughly three to five forums each of which are two or three days with fieldwork and coaching in between, for the main part of a leadership programme. This should then be supplemented with yearly refreshes of the content and of the expectations of the leaders. We will elaborate on the specific mechanisms to make learning interventions successful, in the next chapter.

Pace

The pace of a leadership development programme is the speed at which it is rolled out across the organization. Here, we mean the pace in terms of reaching broadly throughout the organization, not in terms of the speed for each individual. In general we find that faster is better. We mentioned in the last chapter that priority shifts should be focused on for 12–18 months. This typically starts by engaging the leaders over six to nine months, and then quickly trickles down to the rest of the organization as well over the subsequent six to nine months. As a rule, we find that if within six to nine months of launching a programme the people at the lower levels of the organization see or feel a change as a result of the leadership development programme, they will typically be convinced and see it as a success. What is critical here is that a holistic change approach is used, touching all four quadrants of the Influence Model (more on that in Chapter 6). For the top leaders and pivotal influencers, role-modelling and symbolic actions are key.

The reverse is also true. If after the first six to nine months little or nothing has happened, people lose heart; worse, they may see the whole programme (and its instigators and advocates) as a failure. It is therefore very risky to go slow. We often see this in practice, unfortunately.

Organizations make choices about pace based on a variety of factors. We find that pace, depth and breadth often depends on capacity or money, which are often not the right boundary conditions; it is better to think in terms of risk of remaining in the present state, or the danger of promoting a disadvantageous leadership style, or the problems of failing to attract and retain talent.

Organizations often feel there is a delivery risk inherent in moving faster: how can we possibly make the practical and budget arrangement this quickly? However, that risk is over-estimated while risk of failure is under-estimated. ‘Wait and see’ we have found, is dangerous. Equally, annual budget allocation can be dangerous as it can lead to an erratic and unpredictable start-stop sequence inimical to organization-wide development.

For speed, leadership development must start at the top (level 1) of the organization. But it should also start with level 2 (and involve level 1) in order to get breadth quickly, while also involving the top and seeking to engage the critical ‘Sergeant-Major’ layer quickly who are often more involved in the actual operations of the daily business.

For example, when a national military organization of 80,000 staff launched its new leadership ethos plan, it assembled 800 senior officers (or 1 per cent of the organization) in one venue on one day, and from there rolled out the initiative immediately to its sergeant-majors (each responsible for 120 staff) and from them to its sergeants (each responsible for 35 staff) without any delay.

Other organizations set strict time limits. One started its leadership development programme from first principles and set a deadline of six weeks to develop and start delivering it. Their view was that after the six-week development time, if the programme worked, they would pilot it in any of the 100 countries in which they operated, and roll it out.

Whatever the intrinsic quality of any programme, it must have impact and effect change; and these are best achieved through larger numbers of people. Simply put, if enough people change their behaviour as leaders, the programme succeeds; conversely, if too few change, the programme fails. Moreover, these phenomena are not confined to leadership development programmes; they exist in any organizational change efforts.

Implications for leadership development

The principle of engagement affects the way that programmes are planned, designed, delivered and established in the organization. We look at these steps in detail in Part 2. A sense of the undertaking and the effort required – the journey – should shape all thinking. The effort should be informed by a sense of current leadership capacity and future needs, usually best in the form of a gap analysis. It should also be informed by the intrinsic needs of the leadership development programme itself: enough individuals have to change their way of thinking and behaving for the change to become widespread enough.

To make this work, organizations must secure the full commitment of top management to drive development of the leadership effort, align top-management fully behind mutually agreed leadership gap, connect and communicate clearly to the organization, ensure top-management role-models the desired leadership mindset and behaviours, and ensure that members of the top team are willing to go on a leadership journey themselves.

We see five main implications of Core Principle 2.

1 The leadership path should be outlined from entry level to the executive team, regardless of whether the organization includes only a subset of employees or all employees on such a leadership journey. Each rung of the ladder should furthermore have its own learning pathway, and there should be a clear structure for individuals within the journey.

2 During leadership development interventions, or at other inflection points such as promotions or job movements for leaders, there must be provision for leadership development for sufficient individuals. 5–15 per cent of the workforce should be on a specific leadership development programme during a change effort (as part of the longitudinal learning journey outlined above). Whether or not such development interventions are mandatory will depend on the culture and purpose of the organization; at any rate, they should be attractive enough to pull in participants either by means of their intrinsic value or by means of their reputation.

3 New content and curriculum should be designed to achieve the greatest breadth across the organization; this in turn will reach the critical mass of leaders. The content should be adjusted and tailored to each level, but it must have a broad appeal, application and acceptance. For example, say an organization chooses to focus on empowerment as a theme during a leadership development programme. The content must be tailored to each level, covering the specific behavioural expectations at each level. This will give everyone in the organization a sense of what great leadership looks like and how it is expressed for them specifically.

4 The organization must build up a delivery engine geared towards breadth, depth and pace. Technology plays a key role in enabling this. The latest learning systems – for example laptop based interactive video conferences, virtual reality headsets and mobile applications – can enable a significant yet effective reach across the organization, at a low cost. In addition, building up a programme delivery infrastructure is key to reach scale, for example through a ‘train the trainer’ approach and using ‘power mentoring’ (where five mentees each become mentors to five more colleagues).

5 The journey should run at pace. All the programmes’ design and content should allow for both the short-term and long-term facets of the programme. This means that the initial (say, nine-month) roll-out should not find itself exhausted too soon; and also that a yearly ‘booster’ should be conceived to allow for new thinking, new technology, changing organizational context and most importantly the developed learning and potential of the participants. The programme should continue to stretch the participants.

The increasing velocity of journeys

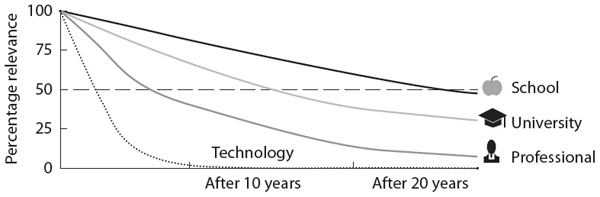

While thinking of engagement in terms of an organizational journey may already be a big step for some organizations, the buck does not stop there. Any discussion and implication of organization journeys must take into account the surrounding trends for organizations. And the trends are demanding. Building on the ‘new industrial revolution’ discussion in the previous chapter, skills are decaying more quickly than before – see Figure 4.1.9 It is estimated, for example, that 65 per cent of children entering primary school today will end up working in new job types that do not yet exist.10

FIGURE 4.1 The degree to which different types of knowledge stay relevant over time

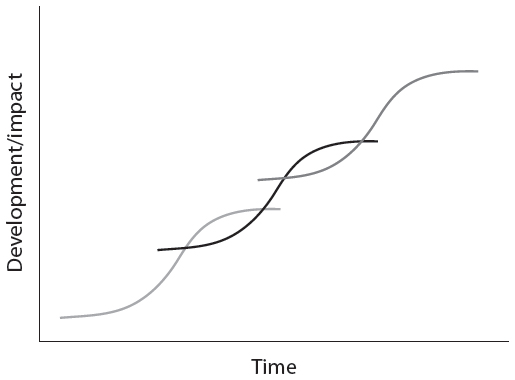

As such, all organizations must renew their development activities periodically. But when and how is this best done in terms of the organizational journey? Does a period of activity draw to a close before another begins? Or do many journeys start simultaneously? A helpful way to think about these questions is through the concept of an S-curve. The S-curve model was developed in the 1960s, and its proponents claim it is one of the best models to understand a non-linear world. It has been applied broadly, for example in regards to organizational life cycles, innovation and general skill-building.11

Let’s apply this to learning. When people enter a new role, for example, they are faced with many new demands and stakeholders, representing a new curve. Capabilities must be built. At the beginning, they go through a steep learning curve in which their knowledge and skills rapidly increase. However, the business impact of their performance is typically low. Gradually their development and business impact accelerates as they gain competence and confidence in the role, until they reach an inflection point. After being in a role for a certain period of time people reach the upper, flatter part of curve, where learning and development have stagnated, tasks have become habits, and business impact has slowed significantly.12 As a result, the best time to initiate the second curve is before the peak of the existing one, while the organization has the resources to start something new. Start the second curve too early, and the benefits of the first are squandered; too late, and the resources and impetus are gone – see Figure 4.2.13

FIGURE 4.2 The S-curve model

Regarding leadership development, the curve represents the natural life of a programme. The next curve should thus be planned and launched while things are going well. The implications of an increasingly complex world and an accelerating rate of skills decay are shorter cycles between each curve. This implies more breadth (more employees need to be trained), more depth (more intensity and more frequent touchpoints for development), and faster pace of rollout (the rate of learning and skills acquisition is becoming an increasingly important competitive advantage). This means more, not less, leadership development in the future. Similarly, the notions of continuous learning and adaptability are becoming more important, for all employees.

For leadership development practitioners, the implications are that leadership development must become agile and quick to react to changes in the external environment. It also implies greater emphasis on on-the-job learning (which we discuss in the next chapter), and a greater emphasis on embedding interventions into a broader culture of learning and leadership (which we discuss in Chapter 6).

Case study: Change leadership at pace and scale

Context and Challenge

Our client, a global leader in innovative pharmaceuticals and consumer health products is one of Fortune magazine’s ‘Most admired companies’, a global leader in innovative pharmaceuticals and consumer health products, with over 50,000 employees in over 140 countries. It faced a fundamental challenge in the form of a ‘patent cliff’ with several of its major products about to go off patent. In response, the organization launched a new strategy to drive future growth, with a differentiated approach in its core business areas – moving to a model more dependent on ‘speciality’ products. It implemented a new organization structure which aligned the commercial organization with the new strategy, streamlined R&D, and improved efficiency in shared services. Finally, it invested in capability building in areas that would be critical to the future success of the strategy.

However, the company had two significant challenges. The company’s own employee engagement survey indicated that the company was a heavily performance-focused, IQ-driven organization, which was weak at leading change at scale, empowering its people and engaging the hearts and minds of its employees. Additionally, the new strategy would play out in very different ways in its different markets. In some developed markets, it would essentially mean massively downsizing large parts of the business, while in some emerging markets, the aim would be to double the same business within five years. To fuse the strategic intent with the varying dynamics in the different markets, it was vital to achieve full buy-in for the transformation among the company’s top leaders globally.

Approach

Our role was to help the organization’s leaders understand the strategy and be able to communicate clearly and succinctly what it meant to their divisions and teams, empower them to develop strong local strategies consistent with the company strategy, and help them plan how to roll out the change with a much greater focus on engaging their people.

To support the organization’s leaders in implementing the new strategy and new organization structure, we set up a central Project Management Office (PMO) and launched multiple initiatives, including creating an integrated change story and communication plan, re-tweaking performance targets, putting in place on-going role-modelling from senior leaders, and activating a network of change agents. In addition, we rolled out the Change Accelerator programme across the organization’s top leadership, in order to increase change readiness.

The programme consisted of two-day workshops to tackle the barriers to transformation, ongoing check-ins with senior leaders on their initiatives, and feedback and coaching sessions from trained facilitators to the leaders. Velocity was key in order to achieve success, and the programme had breadth, depth, and pace: the programme was rolled out to over 120 countries globally within 6 months, reaching over 1,000 leaders. Each country had a differentiated approach based on their size, complexity, and change readiness. The scale and pace was achieved by training 70-80 internal facilitators to support the rollout.

The first workshops focused on the new strategic direction, what it meant to be a change leader, engaging and motivating employees through identifying their sources of meaning, and prioritizing the key mindset and behaviour shifts that had to happen (e.g. increased customer centricity). Approximately 18 months after the first workshops, a second series of workshops were rolled out to the same population group, also within 6 months. These workshops focused on helping leaders fully embed the new behavioural shifts, and working through in detail the implications for organizational structure and the skills required to implement the strategy. Approximately two years later, a third series of workshops was rolled out, at the same pace. The focus of these workshops was on re-energising the organization and on further training in change management skills.

Impact

The workshops, combined with the regular check-ins and feedback sessions, provided continuous support for senior leaders to implement the new strategy and way of working. The programme built change capabilities in all leadership teams across business units and functions in 120+ countries. The program achieved extremely high scores (9/10 for content, and for faculty), and participants emphasized that the programme helped shift mindsets, delivered actionable insights, and energized the team. At an organizational level, the company outperformed the industry over the 5 year period when the programme was being rolled out in terms of total returns to shareholders, and also increased sales by ~25%, moving the organization to the second largest in the industry.

Reflection

There were four elements which contributed to the broad success of the programme. First, while certain initiatives previously had allowed countries to ‘opt-out’, meaning that not all countries were covered, this leadership development effort was non-negotiable. The programme was rolled out in a very disciplined and systematic way, and covered all leadership teams in the company. Second, the programme was tightly linked to strategy and to the business objectives, and was not ‘change management for the sake of it’. In fact, the positive feedback from the first countries created a positive buzz in the organization, and a strong “pull” for the programme. Third, the programme facilitators did not just come from HR or the Organizational Development (OD) department. The central PMO also trained up business leaders across the globe, which led to the workshops having both the change management and business side of things front and center. Finally, the programme was rolled out at a rapid pace in short bursts, which not only had a positive impact on the local businesses, but also led to employees globally feeling and seeing the change shortly after hearing about the transformation – thereby greatly boosting morale and belief in the new direction.

A short note on resourcing

A common question we get revolves around costs. Surely a leadership programme that engages such a large number of people will be prohibitively expensive? We find that this does not have to be the case. Learning and development budgets often have enough scope to reach sufficient leaders in the right way, if done accurately. In other words, the money is there, but needs to be spent in the correct way.

Here is an example: large organizations typically spend around $800 per employee on training (in general, not just leadership development).14 A 10,000-person organization will then have a yearly training budget of approximately $8 million. For an organization of this size, a programme should seek to reach 5–15 per cent – or around 1,000 people overall (the faster the better). If within those 1,000 there are 20 per cent (200) on a structured programme at any time, of around eight days: that makes 1,600 days of formal programme per year. Our experience shows a design and delivery cost for fully tailored programmes of approximately $2000 per forum day equivalent (including forum, fieldwork and coaching), equal to around $3.2 million.

The remaining 800 leaders could be engaged through online learning and one-day boosters. Assuming two days of contact per person, at a cost of $500 per day per person (lower due to technology plus in-house facilitators), that amounts to $0.8 million.

The other 9,000 employees in the organization are reached (in terms of leadership) through on the job coaching by their managers, reinforcing mechanisms, and ‘seeing what good looks like’ by leaders in the organization. They can potentially also be reached through technology, which – once developed – can have a marginal cost close to 0. We will discuss this in more detail in Chapter 6.

The total is thus approximately $4 million on leadership development of the top 10 per cent, or about half of a typical training budget. The other half can then be used for in-house staff costs and technical/functional skills. Interestingly, we find that organizations typically have learning and development budgets available for leadership development – the money is there. The imperative is thus to spend this budget more effectively, and not necessarily to earmark new funds for leadership development.

Summary

Is engaging the leadership with the organization development effort relevant for all organizations? Of course there will be nuances, but if the goal is to improve organization-wide leadership effectiveness, then the answer is yes.

Organizations must engage a critical mass of excellent leaders and influencers in order to change leadership behaviours at the appropriate level, and to give everyone in the organization an understanding of what great leadership looks like. Ideally this begins with the top team. They must be willing and able to embody and explain what great leadership looks like. The organizational journey – with its elements of breadth, depth and pace – is one on which the whole organization embarks. Without it, leadership development interventions become sporadic and episodic, and without lasting impact across the organization. We also saw the decreasing ‘cycle times’ between required skill refreshes. Organizations that engage mutually with their leadership development efforts tend to think in terms of continuous development, for all people, at all times.