If you were faced with the threat of the disappearance of your nation, what would you do?

Enele Sopoaga, prime minister of Tuvalu, at the United Nations climate summit in Lima, Peru, December 2014

For those familiar with the term “climate change refugees,” Pacific islands may be the first thing that come to mind. There are hundreds of small, low-lying island nations in the Pacific Ocean, with pristine beaches surrounded by endless seas. They are magnificently beautiful, and a prime tourist destination, but it is easy to see how global warming imperils their existence. As the seas slowly rise—slowly but at an inevitable and increasing pace—their land disappears inch by inch. Sea level rise is a clear, inarguable result of climate change, and if it continues unabated, ocean tides will keep encroaching farther on island shores, potentially wiping out hundreds of islands from the map. It settles the question of whether, in the future, will we need to make new maps and globes.

The sheer variance of impacts from climate change can be difficult to grasp. Some regions will see severe, unabated drought while others will face floods and storms intense enough to wipe out entire industries. While the average temperature rises, cold winter weather will also become more extreme in some areas due to a weakened polar vortex. Scientists have connected global warming to monsoons, heat waves, storms, coral bleaching, snowstorms, and even increased shark attacks. The science is more settled on some predictions than on others, but one impact is a constant throughout the world: global warming is causing the oceans to rise.

Slowly but surely, the global sea level is rising approximately one-tenth of an inch each year.1 The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) has calculated sea level rise at a rate of 0.12 inches per year, more than twice as fast as the preceding ninety years.2 Every increase in sea level rise causes the tide to encroach much further onto the shore, threatening coastal homes and communities around the world. In 2013 conservative estimates projected between one and three feet of sea level rise by 2100, but now those projections are outdated, and sea levels are expected to rise between three and six feet by the end of the century.3 It seems every new study about melting ice caps and sea level rise paints a more dire picture than the last.

Two major factors are causing the seas to rise at such an unprecedented rate, both of which are connected to warmer global temperatures. The first is the melting of the ice sheets. Glaciers, polar ice caps, huge ice sheets, are heating up and releasing more water each year. Standard depictions of global warming tend to include images of glaciers disappearing—from the Himalayas in India, to Mount Kilimanjaro in Africa, to Glacier National Park in the Rockies. The glacier melt is leading to a surplus of runoff that eventually leads to the ocean and causes sea levels to rise. The giant ice sheets in the Antarctic and on top of Greenland are melting at an accelerated rate. Antarctica is of particular concern, with its massive ice shelves threatening to break off and collapse into the sea.4 Indeed, Antarctica may have passed the “point of no return” for saving its western ice shelves. Once they break off of land, they float in the sea and raise the ocean sea levels.5

This is a good time to clarify the difference between sea ice and land ice. “Sea ice” refers to the ice caps and glaciers that float freely in the sea. “Land ice” refers to the huge ice sheets and glaciers that are fixed to continental plates. The Arctic consists solely of sea ice; whereas the Antarctic is topped with massive amounts of land ice. The two poles provide contrasting concerns for the impacts of global warming. Arctic ice is melting at an incredibly alarming rate, eliminating the habitat for many vital Arctic species, but it does not contribute to sea level rise. Consider the Arctic as a large ice cube in a glass of water. When the ice cube melts, the level of water in the glass won’t change. But Antarctica is more like a huge ice cube placed on top of the already full glass of water, and when it melts, the glass will overflow.

Antarctic ice is actually increasing for the time being (warmer air leads to more precipitation in the form of snow, which accumulates on the ice sheet), but global warming will eventually reverse this trend. The six key glaciers on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet are releasing ice into the sea more quickly than can be replaced with new snow. One glacier, the Thwaites Glacier, is collapsing slowly, which could destabilize more ice. This means the massive amount of what is currently land ice in the Antarctic will one day become sea ice, contributing to sea level rise. These six Antarctic glaciers alone—Thwaites, Pine Island, Haynes, Pope, Smith, and Kohler—will be responsible for an extra four feet of sea level rise over the next two hundred years. It will be a slow-moving crisis, but a crisis nonetheless.

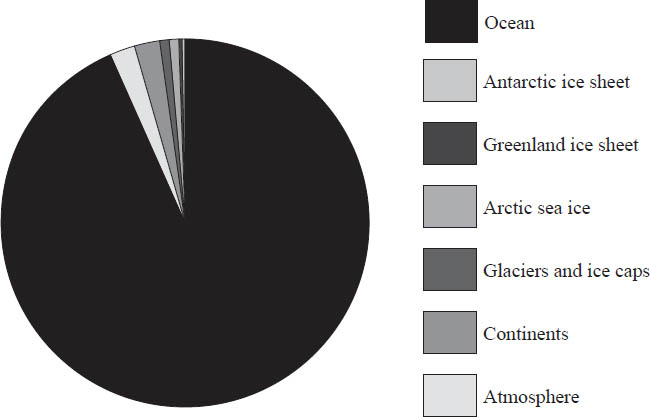

The other factor in the sea level rise is ocean expansion. Much of the world’s warming is being absorbed by the oceans, which is causing them to expand. It’s a simple act of physics: as water gets warmer, its molecules move around more quickly and are a bit farther apart, and the volume increases.

Most of the global warming in the past couple of decades has been trapped in the oceans. When you hear some people talk about a recent “slowdown” in global warming (usually people trying to cast doubt on climate change), they’re referring to surface air temperatures, not the temperature of the planet as a whole. Ninety percent of the heat generated by burning greenhouse gases is absorbed into the oceans, which have a far greater heat storage capacity than the atmosphere.6

The oceans are, in fact, warming at an unprecedented rate—fifteen times faster over the past ten thousand years, according to a study led by researchers at Rutgers University. The study authors explained that oceans are acting as a “storehouse” for heat and energy. This storage potential may have had a hand in slowing down the rate of global air temperature warming. However, this storehouse is limited; at the very least: “It may buy us some time . . . to come to terms with climate change,” according to the study’s lead author, Yair Rosenthal. “But it’s not going to stop climate change.”7

Figure 3.1: Global warming is mostly absorbed by the oceans. Global warming for the period 1993 to 2003 calculated from IPCC AR4 5.2.2.3.

When the warming of the oceans combines with the melting of the glaciers and ice sheets, the reality of sea level rise is very alarming indeed. With the most conservative estimates at one to four feet, and more recent estimates much higher, it is almost certain that low-lying islands will be completely submerged. But even before they become completely submerged in the ocean, low-lying islands will still face extreme damage from the rising sea levels. Every storm surge or high tide slowly washes away bits of their land. Though ephemeral, the surges and tides can erode beaches—which often contain food sources and houses—far before the beaches are overtaken by sea level rise.8

While the sea levels are rising slowly, extraordinary cyclones rip through the Pacific Ocean, passing over the Pacific Islands easily. There is not yet strong consensus as to whether global warming will cause cyclones to happen more frequently, but it is certain that they will become more extreme as sea levels continue to rise. Higher seas cause greater storm surges and resulting flooding, inundating villages on the islands and damaging communities beyond repair.

In March 2015, Cyclone Pam ravaged a number of Pacific islands in the Melanesia region northeast of Australia with wind speeds up to 200 miles per hour. It first tore through Tuvalu, causing a state of emergency and displacing about 4,000 people—nearly half of its population.9 Days later, it struck the island nation Vanuatu, directly west of Fiji, a broadly scattered volcanic archipelago comprising thirteen large islands and over seventy small ones. Vanuatu is home to only about 260,000 people, and Cyclone Pam displaced 3,300 from their homes.10

When a category 5 cyclone like Pam blasts through, it is as if all the threats that the Pacific Islands face from global warming combine forces and hit at once. Powerful winds and rains tear the roofs from homes and flatten buildings. Even cement buildings are ripped apart. In Vanuatu’s capital city, 90 percent of the buildings and houses were destroyed. The storm surges inundated entire beaches and villages for days, providing a snapshot of future sea level rise. Vanuatu’s president, Baldwin Lonsdale, attributed the devastating cyclone to climate change: “We see the level of sea rise. . . . The cyclone seasons, the warm, the rain, all this is affected. . . . This year we have more than in any year. Yes, climate change is contributing to this.”11

Indeed, there is a direct link between sea level rise and the impacts of cyclones. Higher seas cause the storm surges to break more ground and reach farther inland. And as the atmosphere and the oceans continue to warm, the cyclones are expected to become stronger. With warmer sea surface temperatures comes increased water vapor and, subsequently, more precipitation. For every one degree centigrade of warming, rainfall from cyclones can be expected to increase by 8 percent.12

In response to Cyclone Pam, the Vanuatu village named Takara made a bold move: it voted to move to higher ground. Village chief Benjamin Tamata told the Associated Press that he plans to resettle the village one thousand feet inland to avoid the rising seas. He noted that many villagers escaped the storm by taking shelter in a school but that a long-term solution was needed.13

Takara’s decision is not unique; nearly a decade earlier, the Leteu settlement on the Vanuatu island of Tegua was forced to resettle inland in order to escape the rising seas. Dangerously high tides had flooded the village five times a year, regularly creating perilous, life-threatening conditions. In 2005 the village of about one hundred people moved half a kilometer inland onto higher ground in the mountainous island. The United Nations Environment Programme said the village was one of the first, “if not the first, to be formally moved out of harm’s way as a result of climate change.”14

If Pacific islands are the poster child for the climate refugee issue, then Mohamed Nasheed, former president of the Maldives, might be the face. The Maldives have an average height of seven feet above sea level, so the immediate dangers they face from climate change are clear. Indeed, the country is well known for taking a stance on this existential threat.

The young, charismatic Nasheed elevated the plight of the Maldives to global prominence when he was president of the island nation, making impassioned speeches to global delegates at United Nations conferences. In 2009, ahead of the UN climate conference in Copenhagen, Nasheed arranged a cabinet meeting to sign a document calling on nations to slash their atmosphere-warming greenhouse gas emissions. This, by itself, is not necessarily newsworthy, but the location was unique: the cabinet held the meeting fifteen feet underwater. Eleven cabinet ministers joined Nasheed in scuba suits, where they communicated with hand signals and white boards. Surrounded by snorkeling journalists, Nasheed said, “We’re now actually trying to send our message, let the world know what is happening, and what will happen to the Maldives if climate change is not checked. . . . If the Maldives cannot be saved today we do not feel that there is much of a chance for the rest of the world.”15

Nasheed helped drive discussion of climate refugees into global media. He told the Sydney Morning Herald in 2012 that fourteen Maldivian islands had already been abandoned due to erosion. He and his administration took steps to plan for the very real possibility of relocating their entire nation, including setting up a sovereign savings account from tourism revenues for this purpose. The savings account was one step ahead of some other island nations that have been considering planned migration as a response to rising sea levels. Nasheed considered purchasing swaths of land in Australia, because he did not want his people “‘living in tents’ for years, or decades, as refugees,” he told the Herald.16

Unfortunately, Nasheed is no longer president. The country faced political troubles before and after his time as president under the autocracy of Maumoon Abdul Gayoom. Nasheed stepped down from office amid public outcry surrounding the arrest of the chief judge of the nation’s criminal court and then lost the presidential election to Gayoom’s half-brother, Yameen Abdul Gayoom, in 2013.17 Nasheed characterized the situation as a political coup.18 He was later arrested under antiterrorism charges. It was a very unfortunate ending to what was for a time a positive moment in the history of the Maldives.

Because of Nasheed’s actions, the Maldives was among the first well-known climate refugee nations. And it is certainly not the only one. Hundreds of low-lying island nations face the same existential threat from sea level rise, which could eventually erase them from existence. A few other islands might actually take the claim for being home to the first official climate change refugees—most notably, Kiribati.

A high-profile refugee legal case between Kiribati and New Zealand had potential to break new ground in how climate change is considered in terms of refugeedom. At risk of being deported from New Zealand, Kiribati-native Ioane Teitiota has launched a bid to become the world’s first climate refugee, calling on the New Zealand government to allow him to stay.

Kiribati, like many low-lying islands, is bordered by a sea wall that is several feet high to prevent the worst of the ocean waves brought by storm surges from flooding into the shoreline and eroding the land. But storm surges and ocean waves riding high tides had destroyed part of the sea wall and flooded Teitiota’s family’s compound twice in four years. So they decided to pack their bags and leave. In 2007 Teitiota and his wife, Angua Erika, moved to New Zealand on work visas. Four years and three kids later, his visa had expired, and he appealed to the New Zealand government to extend his status. His lawyer on the case, Michael Kidd, saw there was a larger story than a single family appealing for a visa extension. This was the case of a climate change refugee.19

While in New Zealand, Teitiota learned the fuller story about the constant threat his island faced. Similar cases of people fleeing from Kiribati had been tried, unsuccessfully, in New Zealand. Seeing this as a problem larger than himself, Teitiota decided to take a unique approach to his immigration case and make it about climate change. His lawyer made the case that the Teitiotas had been persecuted by industrialized nations who failed to keep greenhouse gas emissions in check.

The legal battle spanned several years. In court, Teitiota cited the poor environmental conditions that made living in Kiribati a never-ending hardship. Kidd emphasized that this was a result of indirect persecution. Their case was rejected by both New Zealand’s high court and the court of appeals. But after each rejection, Kidd refiled the papers seeking refugee status for Teitiota and his family. Each time, climate change was mentioned prominently as being responsible for the Teitiota family’s refugee status. If the court ruled in their favor, the case would have immense global implications. It was finally brought to New Zealand’s Supreme Court, the final avenue of appeal for the Teitiotas to reside permanently in New Zealand as refugees from climate change, but was rejected in July 2015.20 The Teitiotas, according to New Zealand’s court, did not meet the technical definition for “refugee” as defined in the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees: someone who, “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”21 They, like many other Kiribatis, do not yet have a standing to be protected under refugee laws. They simply do not fit into the half-century-old definition of “refugees.”

In the end, the New Zealand government deported Teitiota. He returned to Kiribati in September 2015. But less than a week later, the former president of East Timor, José-Ramos Horta, offered a home to Teitiota and his family in his country, the nearby island nation Timor-Leste. Affected by the story, Horta offered to fly the Teitiotas to his country and help Ioane find a job.22

The president of Kiribati, Anote Tong, is not waiting for the legal definition of “climate change refugee” to change before taking action. Kiribati has a population of about one hundred thousand and spans a mere 313 square miles.23 In recent years the country has faced severe storms and flooding that threaten its food and water supply. In response, the president of Kiribati has purchased land in Fiji—over five thousand acres. In the short term, Fiji’s land can be used to cultivate food if Kiribati’s land becomes infertile from saltwater erosion. In the long term, this land may be used to resettle the Kiribati population. The Kiribatis call it “migration with dignity.” Walter Kaelin, a representative of the Nansen Initiative on Disaster-Induced Cross-Border Displacement, said this is a smart move: “They want to be able to choose more or less where they go. In that sense they want to remain masters of their own destiny.”24

President Tong provides a provocative example of how an island nation is taking initiative to act on climate change. In addition to planning for the worst-case scenario, he is asking nations to work harder to mitigate climate change as well. Tong called for a worldwide moratorium against new coal mines, which would make great progress in reducing future carbon emissions. Ahead of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Paris in December 2015, Tong wrote a letter to world leaders, asking: “Let us join together as a global community and take action now. . . . I urge you to support this call for a moratorium on new coal mines and coal mine expansions.”25 The nation-states achieved a landmark international agreement for climate change action at the conference, but in order to prevent the worst-case scenario for sea level rise, the world will need to ramp up efforts to address climate change in the years to come.

Yet another high-profile refugee court case has been driving conversation in the media. In this case, Sigeo Alesana and his family fled their imperiled island nation, Tuvalu, and were granted residency in New Zealand. However, there is a key difference between this case and that of the Teitiotas. Teitiota and his lawyer made climate change the centerpiece of their appeal, while the Alesanas used additional means to build support for their case. This has led experts to question whether the Alesanas can really be called “climate change refugees.”

Tuvalu, located between Australia and Hawaii, averages about two meters above sea level. Experts predict it could disappear somewhere between thirty and fifty years from now.26 Alesana and his family fled the country in 2007 for New Zealand and lost legal status in 2009. Unable to obtain work visas, they applied for refugee status in 2012, claiming to be threatened by climate change in Tuvalu. After their case was initially dismissed, it was ultimately approved in 2014, when New Zealand’s Immigration and Protection Tribunal granted them permanent residency. The tribunal explicitly mentioned climate change in its decision, writing that Alesana’s children in particular were “vulnerable to natural disasters and the adverse impact of climate change.”27

However, the tribunal took additional factors into account, most importantly, familial ties. It “avoided a clear decision on whether climate change can or cannot be reason enough for refugees to be granted residency,” reported the Washington Post.28

There is dispute over whether or not climate change itself played a role in the Alesanas’ residency decision. Some experts argued that the case will not affect the status of future potential climate change refugees. Vernon Rive, a senior lecturer in law at Auckland University of Technology Law School, said, “I don’t see it as delivering any kind of ‘verdict’ on climate change as such.” He added, “What this decision will not do is open the gates to all people from places such as Kiribati, Tuvalu and Bangladesh who may suffer hardship because of the impacts of climate change.”29 Still, the fact that climate change was mentioned in the court’s decision did not go unnoticed. The case was closely followed by immigration and environmental experts. The Washington Post called it “a landmark refugee ruling that could mark the beginning of a wave of similar cases” in Tuvalu and elsewhere.30

“The Marshall Islands likely won’t exist if we warm the planet 2 degrees,” reported CNN’s John Sutter. “It’s one of the clearest injustices of climate change.”31

Near the equator and slightly over the international date line, the Marshall Islands consist of a string of twenty-four low-lying atolls. Nearly seventy thousand people live on the numerous islands and islets. The islands average little more than three and a half feet above sea level and are ranked as the most endangered by climate change. “Out here in the middle of the Pacific Ocean climate change has arrived,” argues Marshall Island president Christopher Loeak. Unless the Western developed nations create a carbon-free world by 2050, “no seawall will be high enough to save my country.”32

These islands were the subject of a high-profile, long-term 2015 CNN investigation called “Two Degrees.” In it, Sutter examined what our world could look like if it were warmed by two degrees centigrade, “the agreed-upon threshold for dangerous climate change.”33 The two-degrees series topics were submitted, and voted upon, by CNN’s audience. The first story chosen: Pacific Island climate change refugees. This alone—the fact that a mainstream media audience voted on climate change refugees as one of the most important topics of our time—signifies a change in how people are reacting to the issue of climate change refugees and how they want to learn more. It is unlikely that CNN’s audience was even aware of this issue ten years ago.

Sutter’s climate change refugee report began by examining a family who woke up in the middle of the night to salt water flooding through their home; it went on to detail how their communities are threatened by high tides and rising seas. Sutter reported that many families are already deciding to move away, unable to manage the constant flooding. In his report, Sutter was surprised by the nonchalance in governmental and scientific discussion regarding the islands’ inevitable fate, such as that in the Marshall Islands.34

Meanwhile, the country itself is taking the issue very seriously, in stark contrast with the ponderous international talks and scientific reports about the issue, deliberating the climate policies, possible choices, and subsequent impacts at stake. Currently, a bizarre migration event is taking place from the Marshall Islands to Springdale, Arkansas. Of the Marshallese population of sixty-eight thousand, 15 percent currently live in Springdale, the largest population outside of the Marshalls Islands themselves. It is about the farthest away they could possibly get from life in the Marshalls, a place “as landlocked as they come.”35 The Marshalls has a consul office set up there. Some Marshall natives work in the poultry industry; Springdale is home to the worldwide headquarters of Tyson Foods. A community of Marshallese has blossomed there; once extant, it becomes an attractive destination for others to move into as well.

The Marshall Islands and the United States have a unique relationship that allows the Marshallese to live and work freely in the country without a visa. After the American victory in the Pacific in World War II, the Marshalls became a Pacific Trust Territory under the supervision of the United States. The Marshalls achieved full sovereignty as an independent nation under the protection of the United States after 1979. The United States still maintains a military base on one of the Marshall atolls, and due to the Compact of Free Association the Marshallese are allowed to enter the United States for study or work. But their right of permanent residency remains unclear.

Many Marshallese residents have not yet resigned to leaving their country forever. The president’s daughter, Milan Loeak, told Sutter, “I don’t want to entertain that question. I think people should be saying, ‘What can we do to help?’ instead of saying, ‘When will you go?’”36

In 2014 poet and Marshall Island resident Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner read a poem before the United Nations, bringing the hundreds of delegates to tears. The poem was written to her seven-month-old daughter, promising to protect her from the dangers of global warming. Here is an excerpt:

i want to tell you about that lagoon

that lucid, sleepy lagoon lounging against the sunrise

men say that one day

that lagoon will devour you

they say it will gnaw at the shoreline

chew at the roots of your breadfruit trees

gulp down rows of your seawalls

and crunch your island’s shattered bones

they say you, your daughter

and your granddaughter, too

will wander rootless

with only a passport to call home

dear matafele peinam,

don’t cry

mommy promises you

no one

will come and devour you

no greedy whale of a company sharking through political seas

no backwater bullying of businesses with broken morals

no blindfolded bureaucracies gonna push

this mother ocean over

the edge

no one’s drowning, baby

no one’s moving

no one’s losing

their homeland

no one’s gonna become

a climate change refugee

or should i say

no one else

to the carteret islanders of papua new guinea

and to the taro islanders of the solomon islands

i take this moment

to apologize to you

we are drawing the line here

because baby we are going to fight

your mommy daddy

bubu jimma your country and president too

we will all fight37

Like the other island communities, the Marshallese are not waiting for the rest of the world to act. In its submission to the United Nations climate negotiations, the country pledged to cut its emissions by one-third by 2025. It is the first developing nation to pledge carbon reductions.38 And it is urging Australia to do the same.39

Island nations are already dealing with the existential threat posed by climate change. In the Carteret Islands, Papua New Guinea islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean, entire communities have already moved to higher ground on the mainland.40 High tides have already inundated the islands, “destroying crops, wells, and homes,” Business Insider reported. The Torres Strait Islands are located between Australia and New Guinea and are made up of 274 islands with a population over 8,000. The 100 people living on the island of Tegua were declared the world’s “first climate change refugees” by the United Nations in 2005. A one-meter rise of sea levels could make the Federated States of Micronesia completely uninhabitable. One man was seen standing shin-deep in water, where a cemetery used to be. Micronesia’s ambassador to the UN told ABC News, “Even the dead are no longer safe in my country.”41

The Pacific islands will need to adapt to the impacts of climate change. Even the most aggressive fossil fuel reductions—though important— will only slow the rise of the oceans. In turn, communities in the Pacific are talking about “migration with dignity.” Rather than succumbing to the inevitable fate of their homes being destroyed, they are taking charge of their own destiny. This could involve several things, as explained in the Guardian: “It could involve planned relocation, where entire communities move together. Cultural practices, family connections and customs are maintained and the community is reestablished in a safer location. Or it can mean migration bit by bit and integration into new communities. Many people from Pacific island nations are already working and studying abroad. Some see the continuation of this trend as the solution.”42 The small island nation of Vanuatu, for one, is planning to migrate its population farther inland. But this option is not viable for the countries comprised of atolls and sandbars that do not have a “farther inland.”

The Carteret Islands also have plans to “migrate with dignity,” much like Kiribati. They call it “Tulele Peisa,” which in their native language means “sailing the waves on our own.”43 The program provides training and education so that the community members can make informed decisions about their own future. It also researches sustainable living practices for those who choose to stay as long as they are able. Ursula Rakova, an environmental advocate from the Carteret Islands said, “Our plan is one in which we remain as independent and self-sufficient as possible. We wish to maintain our cultural identity and live sustainably wherever we are.”44 The solution for preserving a single community’s identity and culture—such as Rakova’s—is not found in drawn-out international negotiations. The community’s residents need to take their fates into their own hands.

As island nations plan to relocate their population to escape the effects of global warming, other questions arise: When will they need to do this? And what can the developed countries do to give them more time?

These nations are urging the rest of the globe to reduce their fossil fuel emissions. A group of island nations in the Pacific, the Caribbean, and other seas—called the Small Island Developing States (SIDS)—joined together in 2015 at the UN Security Council to ask for help in combating climate change. This council, reported Agence France Presse (AFP), typically hosts debates on threats of war and political conflict concerning countries like Syria and Ukraine. Climate change is usually reserved for a different agency within the UN, the Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).45 Yet because of the environmental security crisis that island nations are exposed to, the Security Council is becoming an ever more appropriate arena for discussing climate change.

The small islands, SIDS, pleaded for “financial and technical assistance to help them avoid becoming washed away in the rising tides and powerful storms caused by global warming.” Tong said the plight of his country has been overlooked by the United Nations for too long and he hoped the appeal would change that, AFP reported. Tong stated: “Can we as leaders return today to our people and be confident enough to say . . . that no matter how high the sea rises, no matter how severe the storms get, there are credible technical solutions to raise your islands and your homes and the necessary resources are available to ensure that all will be in place before it is too late?”46

How long it will take to find solutions for the Pacific island climate refugees is uncertain. It rests partially upon how long it takes to reach strong international action on climate change. Now the appeal to industrialized nations has been made. Time will tell if they listen.

https://unfccc.int/files/meetings/lima_dec_2014/statements/application/pdf/cop20_hls_tuvalu.pdf.

1. C. H. Carling, E. Morrow, R. E. Kopp, and J. X. Mitrovica, “Probabilistic Reanalysis of Twentieth-Century Sea-Level Rise,” Nature, January 22, 2015.

2. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Is Sea Level Rising?” http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/sealevel.html

3. Brandon Miller, “Expert: We’re ‘locked in’ to 3-Foot Sea Level Rise,” CNN, September 4, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2015/08/27/us/nasa-rising-sea-levels/.

4. Andrea Thompson, “Melt of Key Antarctic Glaciers ‘Unstoppable,’ Studies Find,” ClimateCentral.org, May 12, 2014, http://www.climatecentral.org/news/melt-of-key-antarctic-glaciers-unstoppable-studies-find-17426.

5. Leslie Baehr and Jennifer Walsh, “NASA: The Collapse Of The West Antarctic Ice Sheet Is ‘Unstoppable,’” Business Insider, May 12, 2014, http://www.businessinsider.com/nasa-west-antarctic-ice-sheet-results-2014–5.

6. “NOAA Satellites Observe Warming Oceans Profile: Q&A with Sydney Levitus,” NOAA Satellite and Information Service, last modified November 29, 2014, http://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/news_archives/SydLevitus_WarmingOceans.html.

7. Ken Branson, “Global Warming as Viewed from the Deep Ocean,” Rutgers Today, October 31, 2015, http://news.rutgers.edu/research-news/global-warming-viewed-deep-ocean/20131031#.WBIRoclcj5M.

8. Erika Spanger-Siegfried, Melanie Fitzpatrick, and Kristina Dahl, Encroaching Tides: How Sea Level Rise and Tidal Flooding Threaten US East and Gulf Coast Communities over the Next 30 Years (Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists, 2014).

9. “45 percent of Tuvalu Population Displaced—PM,” Radio New Zealand, March 15, 2015, http://www.radionz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/268686/45-percent-of-tuvalu-population-displaced-pm.

10. Sam Rkaina, “Cyclone Pam: Vanuatu Death Toll Hits 24 as 3,300 People Displaced by ‘Monster’ Storm,” Mirror, last updated March 17, 2015, http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/world-news/cyclone-pam-vanuatu-death-toll-5347338.

11. Karl Mathiesen, “Climate Change Aggravating Cyclone Damage, Scientists Say,” Guardian, March 16, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/mar/16/climate-change-aggravating-cyclone-damage-scientists-say.

12. “Hurricanes, Typhoons, Cyclones: Background on the Science, People, and Issues Involved in Hurricane Research: ‘Is Global Warming Affecting Hurricanes?,’” National Center for Atmospheric Research, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, last updated May 2013, https://www2.ucar.edu/news/backgrounders/hurricanes-typhoons-cyclones#8.

13. Nick Perry, “Wary of Climate Change, Vanuatu Villagers Seek Higher Ground,” Associated Press, July 12, 2015, http://www.deseretnews.com/article/765677274/Wary-of-climate-change-Vanuatu-villagers-seek-higher-ground.html.

14. “Pacific Island Villagers First Climate Change ‘Refugees,’” United Nations Environment Programme, December 6, 2005, http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.asp?DocumentID=459&ArticleID=5066&1=en.

15. “Maldives Cabinet Makes a Splash,” BBC News, October 17, 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8311838.stm.

16. Ben Doherty, “Climate Change Castaways Consider Move to Australia,” Sydney Morning Herald, January 7, 2012, http://www.smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/climate-change-castaways-consider-move-to-australia-20120106–1pobf.html.

17. Associated Press, “Ex-President Mohamed Nasheed Is Arrested in Maldives,” NYTimes.com, February 22, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/23/world/asia/ex-president-mohamed-nasheed-is-arrested-in-maldives.html?_r=0.

18. Andrew Buncombe, “‘They came to power in a coup, They will not leave’: There May Never Be an Election, Claims Former Leader of Maldives,” Independent, October 21, 2013, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/they-came-to-power-in-a-coup-they-will-not-leave-there-may-never-be-an-election-claims-former-leader-8895102.html.

19. Kenneth R. Weiss, “The Making of a Climate Refugee,” Foreign Policy, January 28, 2015, http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/01/28/the-making-of-a-climate-refugee-kiribati-tarawa-teitiota/.

20. “Kiribati Man Faces Deportation after New Zealand Court Rejects His Bid to Be First Climate Change Refugee,” Agence France Presse, July 21, 2015, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015–07–21/kiribati-mans-bid-to-be-first-climate-refugee-rejected/6637114.

21. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees,” Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, December 2010. Quote is from Article 1(A)(2) on p. 14.

22. “I’ll Give Climate Refugee Family a Home,” RadioNZ, September 27, 2015, http://www.radionz.co.nz/news/world/285388/’i’ll-give-climate-refugee-family-a-home’.

23. “Kiribati,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, last updated May 13, 2016, https://www.britannica.com/place/Kiribati.

24. John D. Sutter, “You’re Making This Island Disappear,” CNN, June 2015, http://www.cnn.com/interactive/2015/06/opinions/sutter-two-degrees-marshall-islands/.

25. Alister Doyle, “Pacific Island Nation Calls for Moratorium on New Coal Mines,” Reuters, August 13, 2015, http://uk.reuters.com/article/climatechange-summit-coal-idUKL5N1001WK20150813.

26. “Tuvalu about to Disappear into the Ocean,” Reuters, September 13, 2007, http://uk.reuters.com/article/environment-tuvalu-dc-idUKSE011194920070913.

27. Rick Noack, “Has the Era of the ‘Climate Change Refugee’ Begun?” Washington Post, August 7, 2014.

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid.

31. Sutter, “You’re Making This Island Disappear.”

32. Christopher Jorebon Loeak, “A Clarion Call from the Climate Change Frontline” Huffington Post Blog, September 18, 2014, updated November 18, 2014, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/christopher-jorebon-loeak/a-clarion-call-from-the-c_b_5833180.html?

33. John D. Sutter, “2 Degrees: The Most Important Number You’ve Never Heard Of,” CNN.com, last updated November 24, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2015/04/21/opinions/sutter-climate-two-degrees/.

34. Sutter, “You’re Making This Island Disappear.”

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid.

37. Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, “A Poem to My Daughter,” September 24, 2014, https://kathyjetnilkijiner.com/2014/09/24/united-nations-climate-summit-opening-ceremony-my-poem-to-my-daughter.

38. “Periled by Climate Change, Marshall Islands Makes Carbon Pledge,” Agence France-Presse, July 20, 2015, http://www.rappler.com/world/regions/asia-pacific/99898-marshall-islands-makes-carbon-pledge.

39. “Marshall Islands Foreign Minister Tony de Brum Slams Australia’s Proposed 2039 Carbon Emissions Targets,” ABC.net, updated August 11, 2015, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015–08–11/marshall-islands-slams-australia’s-carbon-emissions-targets/6688974.

40. “Evacuated Carteret islanders hope to send back food,” Radio New Zealand, July 8, 2015, http://www.radionz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/278263/evacuated-carteret-islanders-hope-to-send-back-food.

41. Randy Astaiza, “11 Islands That Will Vanish When Sea Levels Rise,” Business Insider, October 12, 2012, http://www.businessinsider.com/islands-threatened-by-climate-change-2012–10/#micronesia-7.

42. Alex Randall, “Don’t Call Them ‘Refugees’: Why Climate-Change Victims Need a Different Label,” Guardian, September 18, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/vital-signs/2014/sep/18/refugee-camps-climate-change-victims-migration-pacific-islands.

43. “Carteret Islands—The Challenge of Relocating Entire Islands,” https://sinkingislands.com/2014/10/12/carteret-islands-the-challenge-of-relocating-entire-islands/.

44. Randall, “Don’t Call Them ‘Refugees.’”

45. “Island Nations Seek UN Security Council Help in Fighting Climate Change,” Agence France Presse, July 31, 2015.

46. André Viollaz, “Island Nations Seek UN Help to Combat Climate Change,” Agence France-Presse, July 31, 2015, http://interaksyon.com/article/115211/island-nations-seek-un-help-to-combat-climate-change.