Close your eyes and picture your best memory with your family and friends. If you’re like me, that memory is filled with the warmth and comfort of a familiar home. I hope that, unlike me, you are never asked to put a price on that home because of the effects of climate change.

Esau Sinnok, Arctic Youth Ambassador to the United Nations*

Who will be the first climate change refugees in the United States? The answer depends on where you get your news. Multiple broadcast networks reported that an Alaskan town on a barrier island that will soon be swallowed by sea level rise may be the source of the country’s first climate change refugees. Other news outlets have pointed to communities in Louisiana, where an area of land the size of a football field is disappearing each hour due to fossil fuel activities, land degradation, and sea level rise. Some point to Hurricane Katrina, which displaced thousands from New Orleans, and Superstorm Sandy, which displaced hundreds from New York City. Others point to the droughts that could send many Californians from their home state. One could also claim that the first climate refugees were displaced decades ago, when drought and poor land management practices created the Dust Bowl, prompting hundreds of thousands of farmers to move from the Great Plains to the West. The question will not be who are the “first” climate refugees but what are we going to do about the inevitable climate-induced migration to come.

It was the greatest migration event in modern American history, inspiring folk songs and novels. The Dust Bowl occurred in the United States in the 1930s when overaggressive agriculture practices and prolonged drought turned the western Great Plains into the infamous prolonged dust storm that made life in the heartland unbearable. In sum, 2.5 million people were forced to leave the region.

There is a “before” and “after” to every migration story, and as illustrated in The Grapes of Wrath, the “after” story for Dust Bowl refugees who fled to California was often filled with difficulties. The Dust Bowl migrants moved to many areas that were already experiencing water and resource shortages, thus stressing local tensions. The absorption of these migrants in California created more than its share of conflict. “Okies” from the plains faced slurs, discrimination, and beatings. Their shacks were burned, and police were called on to guard the California border and block new migrants from entering the state.

Alarmingly, in recent years the Great Plains area of the American Midwest has suffered from a drought similar to the one that created the famous Dust Bowl. Farmers are liquidating their stock, people are moving out, many settlements are becoming near ghost towns. Changes in environment and technology—the farmers of today have new tools and techniques, leading to larger farms and fewer workers—are emptying out the heartland. Life on the plains in the age of cell phones and technological innovations such as dry farming means the situation may not be as bad as it was during the Dust Bowl. But keeping one’s fingers crossed in an age of La Niña winters that suck the region dry is the operative behavior.

Severe droughts in the US often have reverberating effects on agriculture elsewhere in the country and around the world. One western state, California, with a population of thirty-four million, can easily destabilize much of the nation in its thirst for water. With the multiyear drought have come soaring food prices in excess of 13 percent. California’s need for water for its urban and agricultural areas is so great that many in the state’s business community talk of building pipelines to the Pacific Northwest and the Great Lakes to access water. The latter vision makes Canadians wary, as they have joint ownership of the Great Lakes and are in no mood to share their “Blue Gold.” Michael Klare, a Hampshire College professor of peace and security studies, notes that high food prices from California’s drought could “add to the discontent already evident in depressed and high-unemployment areas, perhaps prompting an intensified backlash against incumbent politicians and other forms of dissent and unrest.” He adds that “it is in the international arena, however, that [severe drought in the Great Plains] is likely to have its most devastating effects. Because so many nations depend on grain imports from the United States to supplement their own harvests, and because intense droughts and floods are damaging crops elsewhere as well, food supplies are expected to shrink and prices to rise. . . . The Great Drought of 2012 is not a one-off event in a single heartland nation, but rather an unavoidable consequence of global warming,” which is only going to intensify with growing international repercussions. In the coming decades, Klare argues, “millions pressed by drought and hunger will try to migrate to other countries, provoking even greater hostility.”1

The notion of climate refugees is beginning to be taken seriously in the United States. Yet when it is discussed, it is almost exclusively in the context of foreign countries—as is immigration in general. Immigrants are often seen as alien, an idea especially trumpeted in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, when Rev. Jesse Jackson claimed it was “racist” to call American citizens who survived and were displaced by Katrina “refugees.” Jackson claimed that “to see them as refugees is to see them as other than Americans.”2 Regardless, the term “refugee” was commonly used to describe Katrina survivors and is becoming common parlance again among major media outlets to refer to many people living in coastal communities in Alaska who will soon be forced to move.

Native tribal communities have lived on Alaska’s coasts for thousands of years, living off the area’s fish and wildlife and utilizing its ports for commerce. The Alaskan coastal communities now face dual threats from climate change: sea level rise and permafrost melt. As the ocean encroaches on Alaskan shores, valuable coastal lands are slowly eroding. At the same time, the foundation, the very dirt underneath the houses, is on shaky ground: Alaska’s permafrost—soil that is frozen all year round—is warming up and melting.

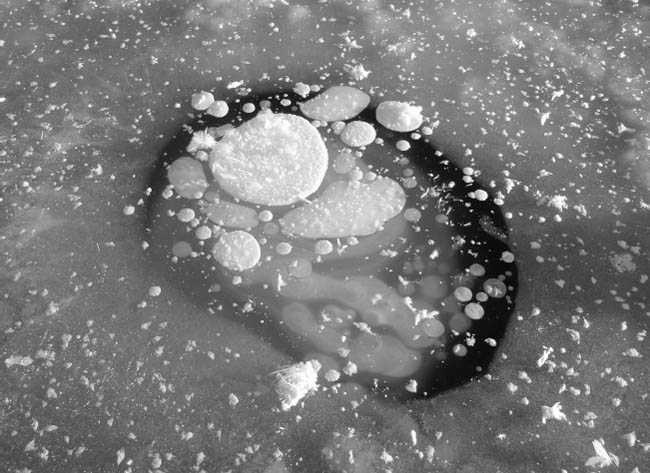

Figure 4.1: Frozen methane bubbles. Photo from US Geological Survey via Flickr.

Temperatures in Alaska and in the Arctic as a whole are heating up twice as fast as they are in the rest of the world.3 The warmer Arctic air temperatures have drastic effects on global climate patterns. But their local effects are significant. Permafrost is vital for literally holding these communities afloat. It is comprised of a mix of ice and soil, and when it melts, the ice turns to water and flows away, and the surface turns spongy and sinks. Because of the variations in the soil and ice composition, the ground sinks unevenly, creating divots and troughs. Houses and roads that sit upon such permafrost are becoming severely damaged. Highways have cracked, houses collapsed, as the ground beneath their foundations sinks. Permafrost melt is one of the many self-reinforcing cycles of climate change: as warmer temperatures melt the permafrost, bubbles of greenhouse gases will be released from the previously frozen soil, which in turn will accelerate global warming and melt permafrost more quickly. There are immense amounts of methane and carbon dioxide currently trapped in the Arctic permafrost.

Scientist Vladimir Romanovsky, who runs the University of Alaska’s Permafrost Laboratory in Fairbanks, has predicted that one-third of the permafrost in Alaska will melt by 2050, and the remaining two-thirds will do so by 2100.4 Other organizations have different projections. According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center, 60 percent of the Northern Hemisphere’s permafrost will be melted by 2200, releasing nearly two hundred billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere,5 or the equivalent of more than forty billion cars driving in one year.6 The United Nations IPCC estimates that 20–35 percent of the permafrost in the Northern Hemisphere will be gone by 2050, and the United Nations Environmental Programme estimates thawing will increase by up to 50 percent by 2080.7 One thing all the models and scientists agree upon, however, is that the permafrost is melting, and it is because of climate change—previously, drastic changes to permafrost took place over thousands of years—and it is going to get much worse as the planet heats up. “Once the emissions start, they can’t be turned off,” Ken Schaefer of the National Snow and Ice Data Center told USA Today.8 “You can see and hear the ice melting,” said permafrost expert Ted Schuur.9

These communities face other threats as well. The ice caps that floated near the ocean shores protected these communities from storms; now that they are melted, the coasts are much more vulnerable. Tundra lakes, the region’s primary source of clean drinking water, have been drying up. But while the melting permafrost, the severe storms, and the drying sources of drinking water are all problems that Alaskan communities face, there are adaptations and protections and solutions to all of them. They do not face the existential threat that coastal communities face with regard to sea level rise. No matter what happens, they need to move, and they know this, and the federal government knows it as well. The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) documented in 2003 that over two hundred Alaskan communities are threatened by sea level rise and shoreline erosion.10 Since then, thirty-one communities have been identified as facing “imminent” threats. Twelve of those have voted to relocate, but as of 2016 none have officially made the move.11 It takes planning and government services and, most importantly, funds, which are in short supply.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), for one, does not make funds available until a state of emergency is declared—and, typically, slowly coming disasters such as sea level rise aren’t classified as such. In fact, many of the communities that face these threats do not qualify for the federal assistance they need. In some cases, federal agencies have invested in infrastructure in towns without knowing that the town officials planned to relocate. The GAO pointed out that the Denali Commission and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) “were unaware of Newtok’s relocation plans when they decided to jointly fund a new health clinic in the village for $1.1 million.”12

The Denali Commission was set up in 1998 by Congress to research and provide economic development to Alaska’s remotest communities, but the organization struggled greatly, with its own inspector general recommending in 2013 that the commission be shut down, calling it a “a congressional experiment that hasn’t worked out in practice.”13 In 2015 the Denali Commission was given new life when President Obama tapped it to address the region’s climate change threats. A White House initiative to improve climate change resilience stated that the commission would “assist communities in developing and implementing both short- and long-term solutions to address the impacts of climate change” and “serve as a one-stop-shop for matters relating to coastal resilience in Alaska.” Its present duties include conducting “voluntary relocation or other managed retreat efforts.” It was awarded $2 million for this specific task.14

Only in recent years have serious steps for relocating these communities begun, and for many they are currently under way. Thus, they are the sources of what many have called “America’s first climate refugees.” The small village of Newtok, with a population of about 350 people, ethnically Yupik Eskimos, receives that specific honor, according to Suzanne Goldberg, environmental reporter for the Guardian.15 Perched on the west coast of Alaska near the Bering Sea, on the shore of the rapidly rising Ninglick River, the town of Newtok made the decision in 2003 to relocate. They chose an area of land nine miles south, across the Baird Inlet, and, most importantly, on higher ground. The land was owned by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the exchange approved by Congress.16 But over a decade later, relocation has yet to take place, and Newtok’s residents remain on its battered coasts, facing severe flooding and erosion.

The Atlantic’s Alana Semuels reports the move has been slowed by legal and financial complications. It has been awarded grants in bits and pieces: $4 million in 2010, $2.5 million in 2011. After a raging storm in 2013, disastrous floods allowed Newtok to request $4 million from FEMA for relocation, through its Hazard Mitigation Grant Program. But that move in particular is problematic—how many disastrous storms will it take for relocation efforts to get the funding they need? The Atlantic contrasted the two decades that Newtok has been struggling to move with the experience of New Pattonsburg, Missouri, which was destroyed by the Great Flood of 1993 and reestablished on higher ground just one year later. As Semuels wrote, “All it took was a disaster.”17

Regardless, Newtok hopes to begin moving homes in 2018 at the earliest.18 But many residents are worried that date will already be too late. One home is placed one hundred feet from the water, but land is being washed and melted away at a rate of fifty to seventy-five feet per year. Goldberg told National Public Radio, “Every year during the storm season, that river can take away 20, 30, up to 300 feet a year. . . . It just rips it off the land, away from the village in these terrifying storms.” The US Army Corps of Engineers predicts that “the town’s highest point—a school—could be underwater by 2017.” The full costs of moving the entire village could be upward of $130 million, predicts the GAO, and very little of that has been awarded.19

Yet the fact that Newtok has plans under way for relocation makes it more fortunate than the dozens of other Alaskan communities that face existential climate change threats. A town called Shishmaref was one of two highlighted on NBC’s Nightly News in September 2015, the first time a broadcast news network mentioned even the idea of climate refugees in nearly ten years. Shishmaref—a bit larger than Newtok, with 600 residents to Newtok’s 350, and a few degrees latitude closer to the North Pole—faces a similar plight. The community voted in 2002 in favor of relocating, one year before Newtok made a similar vote. Yet no new location has been agreed upon. Clifford Weyiouanna, one of the elders, explained, “You can’t build nothing on tundra that’s got two feet of ice. The minute you put something on it, it’s going to melt and houses are going to sink.”20

Therefore the town remains in limbo. In the meantime, the US Army Corps of Engineers built a $19 million rock wall as a temporary measure to protect the community from sea level rise. The town itself cannot afford to make the move without further government aid. Weyiouanna, former chair of Shishmaref’s relocation coalition, complained about the lack of federal assistance: “You almost have to be half the way dead to get help.”21 The government estimates that if they do find a suitable relocation site, it will cost $300,000 to move each villager, for a total price tag of $180 million.22

Many people who are familiar with the situation in Shishmaref are frustrated at the lack of federal assistance. In 2014, Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski urged Secretary of State John Kerry to “put America first” and help “the Alaskans who deal with this reality on a daily basis.” She wrote: “As the United States prepares to assume the Chairmanship of the Arctic Council, it is essential we are prepared to address adaptation issues in our own Arctic communities.”23 Shishmaref residents have tried appealing to Congress, which has many members who deny the science of global warming. Former mayor Stanley Tocktoo said their airstrip could be wiped out after a few more storms, cutting residents off from emergency flights. The group brought with them a plastic tub full of slowly melting permafrost to symbolize the slow change happening in their homes.24

The other town highlighted on NBC’s Nightly News was an Alaskan village called Kotzebue, which President Obama visited on a historic trip to the Arctic—the first time a US president has ever traveled above the Arctic Circle. Kotzebue is bigger than Shishmaref and is home to about three thousand people. It will not relocate, hoping that a $34 million rock wall built to keep out sea level rise will keep it safe.25 Following his visit to Kotzebue, Obama visited a town called Kivalina, located on the tip of a barrier reef island. Kivalina faces similar existential threats to the other communities; some experts predict it will be inundated by sea level rise to the point of being uninhabitable by 2025.26 It will cost Kivalina $102 million to relocate all of its four hundred residents, according to the US Army Corps of Engineers.27 The town voted in 1992 to relocate,28 but it has nowhere near the funds necessary to make this move yet—nor a plan for where to go.

Where will it get the money? Kivalina stands out among the other towns, as it has attempted a unique strategy for receiving the funds they need to relocate. In 2008 the village sued twenty-four of the world’s biggest fossil fuel companies, including ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, Shell Oil, and more.29 They filed a “public nuisance” claim, accusing fossil fuel companies of inflicting “unreasonable harm” to the village for contributing the most to climate change. The residents intended for funds won in the court case to pay for the village’s relocation. Unfortunately, the case faced many roadblocks and was ultimately dropped in 2013.30 The US district court turned it down on the grounds that greenhouse gas emissions need to be regulated by Congress, not the courts.31 The city tried to appeal to the Supreme Court, but the Court refused to hear it in 2013.32 Environmental activist and author Bill McKibben commented on the failed case: “This story is a tragedy, and not just because of what’s happening to the people of Kivalina. It’s a tragedy because it’s unnecessary, the product, as the author shows, of calculation, deception, manipulation, and greed in some of the biggest and richest companies on earth.”33

But Christine Shearer, who wrote a book about Kivalina’s lawsuit called Kivalina: A Climate Change Story, is hopeful that there will be more lawsuits in the future. She said in an interview with Public Radio International: “More communities, more cities, more states, more tribes are going to have to deal with trying to help people who are being affected by climate change. . . . I think more lawsuits will be filed, and I think it might get to a point where fossil fuel companies might find it’s less costly to settle than to keep fighting these lawsuits.”34

While these communities await relocation, they are suffering. With less sea ice to hold down waves, storm surges are constantly eating away at the land and homes. Clean water and sanitation systems are at risk in vulnerable villages like Shishmaref. Health systems are deteriorating and evacuation paths compromised. Airstrips—vital for providing access to mainland, especially to evacuate—are washing away. Investors see little reason to support a community that is planning to move. As Stanley Tocktoo put it, “The decision to move has been very costly for us.”35

In September 2015 Kivalina received a $500,000 grant from an arts organization to study relocation, but its residents have a long way to go,36 as do the Alaskan communities as a whole. The GAO estimates it will cost a total of $34 billion to relocate the 192 Alaskan communities that are currently at risk.37

Since the 1930s, Louisiana has lost nearly two thousand square miles of land, approximately the size of Delaware.38 Every hour, an area the size of a football field vanishes into open water.39 The entire three million acres of Louisiana bayou wetlands took seven thousand years to evolve but could largely disappear within the next fifty if nothing is done to save them.

Wetland landmarks—bays and bayous, islands and streams—are already starting to disappear into the Gulf of Mexico. This is no hyperbole: NOAA is literally removing these landmarks from its maps. In 2013 NOAA removed forty bays and features from its charts. Some of these were named in the 1700s, by the first French pioneers to explore the region; most existed in the recent memories of the residents who grew up in southern Louisiana. The agency updates its maps quite often, but such a huge number of removals in one location is unprecedented, according to NOAA geographer Meredith Westington. “It’s a little disturbing. . . . It’s sad to see so many names go,” she said to USA Today. “I don’t know that anyone has seen these kinds of mass changes before.”40 The places disappearing are not mere points on a map; they provide sustenance and homes to thousands of people. The region of the map removals is called Plaquemines Parish, home to nearly twenty-five thousand people, and without action, over half of the parish will be underwater by 2100.41

As with the river deltas in Asia, there are many factors causing Louisiana’s wetlands—the mouth of the Mississippi River spilling into the Gulf of Mexico, comprised of channels, swamps, and marshes—to sink into the sea. Levees built to protect highly populated areas from flooding prevent sediment, constantly brought downstream by the rivers, inlets, and channels, from washing down and replenishing the wetlands. Drought has also played a role; high tides and floods are vital for carrying sediments downstream and depositing them into the wetlands, and with less precipitation there is less water flow.42

Figure 4.2: Louisiana land loss: parishes with the most to lose. Source: NASA.

Sea level rise is happening in the gulf at a greater pace than the worldwide average, and recently NOAA determined that it is happening faster even than the experts expected. The Louisiana wetlands average about three feet above sea level; NOAA now predicts that the Gulf of Mexico will rise over four feet by 2100, which would inundate everything outside of the levees with water.

Oil and gas operations are much to blame—and that is not including the global warming–driving carbon emissions that result from burning fossil fuels. For over a hundred years, oil and gas companies have dug an extensive array of canals—up to ten thousand miles in total length—to access the thousands of oil and gas rigs peppered throughout the region. Ironically, the only portions of the wetlands that may survive sea level rise are the edges of the canals dug out by the fossil fuel industry.43 There’s no doubt about it: Louisiana’s wetlands are at risk of perishing completely. That’s why they are another inevitable source of climate refugees in America.

Yes, we just spent several pages detailing another potential source for the “first” refugees. But one native Louisiana tribe has taken its plight one step further and is just two years away from relocation.

Plaquemines Parish is the region where NOAA is removing so many landmarks from its maps. It is also the region of Isle de Jean Charles, home to a tribe of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Indians that news website Mashable has dubbed “America’s first climate refugees.”44 The Isle de Jean Charles is a narrow strip of land on Louisiana’s southern edge, surrounded by the waters of the Louisiana bayou. Sixty years ago the land was eleven miles long and five miles wide; now it is just two miles long and one-quarter mile wide.45 It will soon completely disappear into the Gulf of Mexico, and the tribe that has been living there since the 1800s will be forced to move.

In early 2016 the tribe won a $48 million grant from the National Disaster Resilience Competition, a project from HUD in collaboration with the Rockefeller Foundation.46 Tribe chief Albert White Buffalo Naquin had been advocating for relocating his tribe for thirteen years.47 “A way of life did disappear,” he said.48 He told the Institute for Southern Studies, “This award will allow our Tribe to design and develop a new, culturally appropriate and resilient site for our community, safely located further inland.”49 The Isle de Jean Charles tribe is the first community to receive relocation funding from HUD specifically because of climate change. One can only hope it will be a model for future community resettlements as climate change continues.50

Not everyone in Isle de Jean Charles is happy about the move, however; some residents are unwilling to uproot and leave their history, heritage, and way of life behind. Many in the community are planning to try to stay. “This is home,” said resident Edison Dardar to WDSU News, having lived there all of his life, as has his wife. “No money, no offer.”51

The community has to begin moving in two years, but no one is being pressured to move, said Chief Naquin: “At least they will have a place to go in the event something should happen. Now it’s a matter of finding a place where we could settle and where it’s big enough for us to put at least 100 homes and have room for growth for the future.”52

Beyond the Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana’s wetlands are in big trouble. The state has planned a huge, long-shot effort to save them that will take fifty years and cost at least $50 billion.53 It will take an extraordinary amount of innovation; experts are treating the plan as more of a scientific experiment but one that is taking place in real time and affecting thousands of people’s lives.

There is a great risk that it will not work, especially with the increased rates of sea level rise. “To make the project work, scientists and engineers will have to figure out on the fly how to create a manmade system that replicates the delta’s natural land-building process,” reported the nonprofit news corporation ProPublica.54 Further, NOAA scientist Tim Osborn noted that the new data on sea level rise is greater than the worst-case scenario laid out in the wetland restoration plan. Garret Graves, head of the state Coastal Planning and Protection Authority, notes that the plan is structured to adapt and change every five years, so it may adapt to the new information in time. And the Mississippi River contains a massive amount of the sediment needed to rebuild, so Osborn said hope is not lost.55

ProPublica notes that the cost for this project is greater than that of World War II’s Manhattan Project. But the costs of letting Louisiana’s wetlands disappear is even greater. The wetlands serve the country’s largest port, and without action to save them, extreme weather could cause shutdowns that would cost the US economy $300 million each day. So it would take less than half a year—167 days—of those ports being shut down for the costs of not acting to outweigh the $50 billion price tag to protect the wetlands. If they disappear completely, the costs would be astronomical.56

But where will the $50 billion come from? BP is expected to pay for part of the project due to penalties from the 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. It is unclear how much of that will be allocated for wetland restoration, but even all of it would not be enough to meet the $50 billion price tag. After the funds from BP’s negligence run out, then where will Louisiana turn to protect its wetlands?57

As it turns out, the answer may be found again in lawsuits against the fossil fuel industry.58 In this regard, Plaquemines Parish has taken a similar tack as the Alaskan community suing for the funds to move and is home to some of the most innovative lawsuits ever aiming at environmental restoration.

The oil and gas industry is responsible for a significant portion of Louisiana wetland degradation. The ten thousand miles of land that were turned into open water via canals have disrupted the wetlands’ sediment deposition processes, allowed saltwater from the gulf to breach the wetlands and destroy plant life, and removed valuable protections against storms, thus increasing the size of storm surges, which in turn speeds up erosion. In fact, the industry has admitted responsibility for 36 percent of wetland loss, although government estimates put it as high as 59 percent.59 This fact has not gone unnoticed by the people of Louisiana who want to make the industry pay for ruining their homes.

In 2013 the South Louisiana Flood Protection Authority–East filed suit against ninety-seven oil and gas companies in what the New York Times called “the most ambitious environmental lawsuit ever.”60 The lawsuit argued that the fossil fuel companies were supposed to fill in the canals after they were finished using them and that they broke their permits by not doing so and now need to take responsibility for the damages.61 But the lawsuit faced fierce opposition by local and state politicians who are interested in protecting the oil and gas industry, a major source of economic activity. In fact, Louisiana is among the top oil- and gas-producing states in the country.

E&E News said that the lawsuit’s “biggest hurdle” was “not its merits, but the staunch opposition of the Jindal administration and the Legislature.”62 Former governor Bobby Jindal is a staunch defender of industry and denounced the lawsuit, blaming the case lawyers for “taking this action at the expense of our coast and thousands of hardworking Louisianians who help fuel America by working in the energy industry.” The state legislature crafted bill after bill to try to block the lawsuit.63 One bill was thrown out by a state judge as unconstitutional.64 In the end, in February 2015 the state judge ruled against the flood authority’s lawsuit. The reasons cited for throwing it out, however, had everything to do with the party filing the suit—the levee authority—not the merits of the case.65

Meanwhile, the council of Plaquemines Parish was pushing through its own attempt at suing the oil and gas industry for wetland damages. It filed twenty-one lawsuits, and the neighboring Jefferson Parish council filed seven, against many of the ninety-seven companies named in the levee authority’s suit.66 But the council saw fierce opposition to these suits from the oil and gas industry, which had donated heavily to the campaigns of council members in the 2014 elections. By November 2015, many of the original council members who filed the original motion to begin lawsuits were no longer in office, and the council voted 5–1 to drop the lawsuits.67 According to the Associated Press, Sierra Club member Darryl Malek-Wiley alleged that the council members were “wooed by oil and gas companies into voting against the suits.” Malek-Wiley commented, “Once again it shows the power of the oil and gas industry over the interest of our coastal wetlands.”68

Despite the lawsuits in Plaquemine Parish having so far failed, they signify a shift in how Americans are reacting in the face of environmental degradation. The fossil fuel industry receives millions in royalties and tax breaks from the federal government, and people are increasingly turning to these funds as a possible way to pay for the environmental havoc these industries created. E&E News reporter Annie Snider, for one, suggested raising taxes on oil and gas production if those companies had chosen to settle in the levee authority lawsuit. But she also noted that “as long as lawmakers stand prepared to intervene and the Jindal administration maintains its opposition to the lawsuit, a deal like that is seen as a long shot.”69

Former President Barack Obama has also repeatedly attempted to divert oil and gas royalties toward climate adaptation in Louisiana, including protecting the coasts from hurricanes. It was one of the promises he made while campaigning in 2008. And while he has tried to eliminate oil and gas royalties altogether, lawmakers have repeatedly overturned such proposals.70 In his latest budget proposal for Alaska, where he requested raising $400 million for coastal communities, Obama laid out that the funding would come through the Department of the Interior, by abolishing current royalties for offshore oil and gas drilling.71

It makes perfect sense—fossil fuel emissions are driving global warming, putting the coastal communities in the path of sea level rise, so a logical conclusion for helping these communities is to also disincentivize the burning of fossils—and in a perfect world this proposed budget change would be a no-brainer. But it is not a perfect world, and Obama’s budget had scant chance of passing, especially with such a large portion of the two houses of Congress accepting heavy donations from oil and gas companies. Obama’s budget proposal, the last of his presidency, was dead on arrival.72

It is impossible to discuss forced migration in Louisiana without mentioning Hurricane Katrina. Because of Katrina’s power and extensive destruction, Louisiana became the location of the country’s greatest internal migration event since the Dust Bowl—if not ever. In fact, the degradation of Louisiana’s wetlands is directly tied to Hurricane Katrina’s devastation. The wetlands act as a storm barrier, slowing the intensity of hurricanes as they pass through, weakening them before they hit the heavily populated New Orleans region. They also work to absorb the storms’ rains to lessen the height of storm surges, which usually turn out to be the deadliest aspect of hurricanes. Most of the wetland restoration efforts are centered on protecting New Orleans.73 But the rebuilding efforts won’t change what happened, and the devastation of Hurricane Katrina offers an instructive warning for what the future could have in store for climate refugees in America.

Katrina struck the Gulf Coast on August 23, 2005, killing more than one thousand people and displacing over one million. While most of the forced displacement was temporary, hundreds of thousands of people would remain without a home for many months to follow. Hurricane evacuee shelters held 273,000 people at their peak.74 The disaster resulted in a diaspora, with evacuees scattered throughout the country, to Georgia, Florida, Texas, South Carolina, New York, Mississippi, Colorado, and other states.75 The return to New Orleans was slow-going, and for some it never happened.

The ensuing recovery efforts exposed harsh realities about racism in the United States. One year after the storm, less than half the black people evacuated from New Orleans had returned (67 percent of non-black people had).76 Five years after, one hundred thousand people—disproportionately black—still hadn’t returned.77 The racial disparities had roots before the storm. Black neighborhoods were more likely to reside in areas more vulnerable to the storm and subsequently experienced the greatest levels of flooding. The academic journal Southern Spaces noted that before the storm the Gulf Coast states had high levels of racial inequality and “the worst quality-of-life indicators in the nation for their poor, people of color, and women,” historical leftovers of the plantations and slavery. People hoped that hurricane response would lessen inequalities, but the response only served to exacerbate them.78

The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina invalidates arguments that disaster relocation in America will always be temporary. Five years after the storm, entire neighborhoods were still abandoned, and the city’s four major public housing complexes were destroyed or condemned. Tens of thousands of people remained displaced and homeless.

The evacuees had to resettle across the country, but many were not well received. In the weeks after Katrina, South Carolina became home to an emergency relief center for evacuees, and many eventually settled in that state’s Midlands region. Columbia itself accepted up to fifteen thousand people, but that city had a paucity of adequate infrastructure and social services, having among the least available levels of affordable housing and public transportation in the country and the most restrictive social welfare policies. A deeply conservative region, it also had a political environment that was hostile to the newcomers.79

Houston took in the most evacuees, accepting 250,000 in the storm’s aftermath—and 150,000 were still living there one year later.80 Many were sent to live in FEMA-funded apartments in neighborhoods riddled with crime and poverty.81 The media falsely connected the influx of evacuees to a supposed crime wave, fueling residents’ deep-seated antipathy toward the newcomers.82

The long-term consequences of government disinvestment in social services and infrastructure were laid bare in the aftermath of Katrina and the hardships of its survivors. These systems are now vulnerable to the point where another major disaster could upend the social systems that people rely on. With every extreme weather event, those who are under-privileged are hit the worst. With every event, adaptation only serves to widen preexisting inequalities. As Vox’s David Roberts has put it, climate change adaptation is “tied directly to one’s wealth. Rich countries will be able to do more of it than poor countries; within rich countries, wealthier cities will be able to do more of it than poorer cities and rural areas; and even within wealthy cities, it will be the affluent residents who have access to these mechanisms and the poor who are left behind.”83

Indeed, the Kaiser Family Foundation found deep racial divides in how New Orleans residents viewed the city’s recovery even ten years after the storm. White residents were far more likely to believe that the city had mostly recovered and that their needs were being met.84

For the residents of New York City, thousands of miles away from Louisiana, the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina seemed largely a foreign one—that is, until Superstorm Sandy. In September 2012 Hurricane Sandy took a highly unusual path. After traveling northward up the Atlantic coast, it took a sharp left turn to barrel straight west into New Jersey and New York. It was the most expensive storm in America after Katrina, caused 147 deaths, and destroyed thousands of homes.85 Windstorms ranging a thousand miles wide ripped apart New Jersey’s famous boardwalk, and a nearly ten-foot-high storm surge breached the Manhattan seawall and flooded the city’s tunnels and subways.

Superstorm Sandy displaced fewer people than Hurricane Katrina but continued to expose flaws in the government response to survivors. Thirty thousand people remained displaced from New York and New Jersey one year after the storm. Fifty-five thousand homes were destroyed or seriously damaged. Less than half of the people who requested FEMA assistance received it within one year.86 Two and a half years later, fifteen thousand families were still displaced from the storm, and only 328 homes had been rebuilt.87

The storm recovery programs failed the Latino and African American communities in particular, according to the Latino Action Network and the NAACP New Jersey State Conference. Funds were directed to communities that faced less damage than those hardest hit, such as Monmouth and Ocean Counties, they argued, and the state offered less funding to low-income renters.88

As with Hurricane Katrina, the severe impacts of Superstorm Sandy can be directly connected to climate change—particularly, sea level rise. The storm tide in Manhattan blasted previous records, reaching fourteen feet—four feet above the previous record set in December 1992.89 This was a combination of evening high tide and storm surge, which was exacerbated by high sea levels. The sea level off the coast of Manhattan has risen by about one and a half feet since the preindustrial era and is expected to rise another four feet by the end of the century.90 Sea levels are rising on the East Coast about four times faster than the national average.91

It is, in fact, the extensive flooding from storm surges that caused the most damage in New York City and New Jersey. Floodwaters filled the tunnels and damaged electrical equipment. Power outages lasted days, or weeks in some areas. Climate scientist Kevin Trenberth said that the city’s subways and tunnels may not have been “flooded without the warming-induced increases in sea level and in storm intensity and size, putting the potential price tag of human climate change on this storm in the tens of billions of dollars.”92 One study from Portland State University researchers suggests that New York City could experience storm surges that breach the Manhattan seawall once every four to five years, compared to once every one hundred to four hundred years in the nineteenth century.93 And a study from the American Meteorological Society found that by 2050, the Jersey shore could see storm surges at the scale of Superstorm Sandy every year.94

More than sea level rise, climate change may have had a hand in the storm’s highly unusual path. Abnormally high sea surface temperatures allowed the storm to travel farther northward and retain its strength longer than common in late October. A warmer atmosphere also causes more water to evaporate, thereby creating more precipitation.95 All of the signs point to the possibility of future events like Hurricane Sandy, a risk that is always increasing.96

But while sea level threats in high profile cities such as New York City and New Orleans may have gained the most press, it is important to consider the hundreds of other US cities and regions facing similar risks. More than four hundred cities are past their “lock-in date” for sea level rise, according to a study led by Climate Central climate scientist Benjamin Strauss and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2015: it’s guaranteed that more than half of each of those cities will be underwater no matter what actions are taken to mitigate climate change. For New Orleans, “it’s really just a question of building suitable defenses or eventually abandoning the city,” said Strauss to the Huffington Post.97 But Hurricane Katrina showed that building levees is not a fail-safe plan either; the bigger the levees, the more catastrophic the results if the levees fail.

Victoria Herrmann, director of the Arctic Institute, has laid out a key first step for addressing the refugee crisis. She believes that panels of local, state, and federal experts should be convened in order to come up with a framework for relocating all climate refugees within the United States.98 This framework does not exist; indeed, the thought of “climate refugees” in America is hard to grasp.

The other side of the equation is how to prevent future climate refugees. States and local communities need to be better prepared to adapt to future impacts of climate change—particularly, extreme weather events. And indeed, some argue that calling Alaskans the “first” potential refugees discounts the millions of Americans who have already been displaced—albeit temporarily in many instances—due to the effects of hurricanes. But those are just two aspects of the climate change crisis: one of them slow, long-term, and predictable; the other less predictable but far more immediately devastating. To not adapt to the future impacts of extreme weather like hurricanes is to take a giant risk, but that risk is taken by those who have no other choice. Particularly in poor communities, residents often do not have the funds or knowledge to adequately protect themselves.

Table 4.1. US Cities with the Greatest Populations Affected by Sea Level Rise

City |

Pop. Affected |

New York, NY |

1,870,000 |

Virginia Beach, VA |

407,000 |

Miami, FL |

399,000 |

New Orleans, LA |

343,000 |

Jacksonville, FL |

290,000 |

Sacramento, CA |

286,000 |

Norfolk, VA |

242,000 |

Stockton, CA |

241,000 |

Hialeah, FL |

225,000 |

Boston, MA |

220,000 |

The Federal Emergency Management Agency is finally starting to help states prepare for climate change, updating its state plans to incorporate climate change for the first time ever. It is a groundbreaking development for the notoriously reactionary agency. FEMA now requires that state plans for receiving resilience-focused aid include “consideration of changing environmental or climate conditions that may affect and influence the long-term vulnerability from hazards in the state.”99 It is worth noting that the policy does not affect FEMA funds for disaster relief; in the event of a hurricane or extreme flood, the agency would still provide aid in the aftermath.

Disaster preparedness funds are extremely valuable in places like the Midlands, South Carolina, which in 2016 initiated plans to carry out a dozen flood prevention projects and relies on FEMA’s disaster preparedness funding to do so.100 The region saw deadly floods in October 2015, which killed at least seventeen people.101 Other disaster preparedness plans vary by state, from earthquake-proof shelters to flood prevention levees to wind-resistant structures in hurricane-prone regions. Each is tailored to the unique threats that the regions face.

Each region also faces unique threats from climate change. The National Climate Assessment, a report from the US Global Change Research Program compiled by more than three hundred climate scientists and experts over a four-year period, lays out which impacts of climate change we can expect to see in different regions of the United States.102 The future risks that states will face due to climate change is well known, yet many states have not taken the steps to prepare themselves. For instance, Houston, Texas, is woefully underprepared to face an intense hurricane, according to a joint investigation by ProPublica and the Texas Tribune, yet such a hurricane is in store.103

Appallingly, many Republican governors in charge of coastal states attacked FEMA on this change for the simple reason that it would require them to admit that climate change is real. Jindal said in a statement that the White House should not use the FEMA preparedness plans “for political leverage to force acquiescence to their left-wing ideology.” He has previously called climate change “simply a Trojan horse” for more government regulation, saying, “It’s an excuse for the government to come in and try to tell us what kind of homes we live in, what kind of cars we drive, what kind of lifestyles we can enjoy.”104

Florida governor Rick Scott’s office also suggested it would not comply with the new FEMA rule. A spokesperson told the Washington Times that Florida changes their mitigation plans only once every five years and that “Florida’s current [plan] became effective on August 24, 2013, and is approved for use through August 23, 2018.”105 The Scott administration is notorious for climate denial; in fact, according to interviews with former officials at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) conducted by the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting (FCIR), Scott’s administration did not allow staff to utter the words “climate change.” Multiple former officials at the DEP told FCIR that they were ordered not to use the terms “climate change” or “global warming” in “any official communications, emails, or reports.” FCIR reported: “But four former DEP employees from offices around the state say the order was well known and distributed verbally statewide.”106

Multiple other Republican politicians attacked the plan. Several House members signed a letter blasting it. Sent to FEMA administrator W. Craig Fugate, the letter said that climate change is still being debated, citing “gaps in the scientific understanding around climate change.”107

California has been in a years-long drought, the worst experienced in the region in five hundred years. Even if the drought ends, another one may be in store for the state, climatologists say. With thirty-four million inhabitants, drought is no passing inconvenience. The state’s dwindling water supply is putting both agriculture and urban development at risk. If the situation continues, California’s fruit and vegetable farmers will move northward toward water resources. California wineries are already buying vineyards in the Willamette Valley, located in Oregon. As the mercury rises in California and other parts of the drought-stricken Southwest, people will look to the Pacific Northwest as a safe haven.

Currently the Pacific Northwest is one of the safest areas of the country in which to live as far as climate change is concerned. Dr. Cliff Mass, an atmospheric science professor at the University of Washington, predicts the Pacific Northwest will come to be “one of the best places to live as the earth warms” from global warming. He foresees a mass exodus of climate change refugees from other regions of the country settling there.108 It is likely that the Pacific Northwest will continue to be one of the best places to live in terms of water resources and climate, but there may be a downside to that upside. It is likely that human migration patterns will shift and global warming will unleash a deluge of newcomers that will greatly strain resources and human relations in civic communities. In a blog entry Professor Mass joked about keeping Californians out with a barbed wire–topped steel fence.109

The Pacific Northwest has seen climate refugees before. Knute Berger of Crosscut.com recalls the Big Burn, a massive three-million-acre fire-storm that swept across Idaho, Washington, and Montana in 1910, and thousands were forced off the land and converged into Missoula, Spokane, and other communities. During the Dust Bowl crisis of the 1930s, more than 2.5 million people fled the parched Great Plains for friendlier climates. Thousands of migrant farmworkers converged on the Yakima Valley looking for employment and shelter. The Pacific Northwest historically has been built by migration. Berger predicts that “with or without climate change, people are coming. . . . The question is whether some tipping point will send a surge of ‘environmental asylum seekers’” or whether climate change will merely boost some population increases that are manageable.110 If refugees materialize in significant numbers, will they receive sanctuary? Past history of this subject is not comforting.

In his celebrated novel Ecotopia, Ernest Callenbach envisions Washington, Oregon, and Northern California seceding from the United States and walling off an environmental utopia.111 It raises the fundamental question in discussing water and climate refugees: In a warming world do we pull up the gangplanks or put out the welcome mat? Further, the long drought in the Pacific Northwest has recently become the subject of a novel by Paolo Bacigalupi. In The Water Knife, Bacigalupi describes a water war between Las Vegas and Phoenix that sets the scene for an important realization: most people do not think about disaster, even when it is crashing down upon them.112 It is hard to comprehend a potential future such as that described in novels. But when disaster strikes, people move, often behaving erratically and irrationally. Bacigalupi’s novel depicts a future where many climate refugees are on the road in search of water and environmental security. In America as drought continues, Bacigalupi describes a world where states become muscular about their rights, saying, “No, no, this is our territory. We don’t want to share it with the state next to us.” What The Water Knife represents is a time when there has been a lack of oversight, planning, and organization. Says Bacigalupi, “This world is built on the assumption that people don’t plan, don’t think, and don’t cooperate—which makes for a pretty bad future.”113

Epigraph is from Esau Sinnok, “My World Interrupted,” US Department of the Interior, December 8, 2015.

1. Michael Klare, “The Hunger Wars in Our Future,” Environment, August 8, 2012, http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175579/.

2. Justin Fenton, “Use of ‘Refugee’ Is Called Biased,” Baltimore Sun, September 5, 2005.

3. Michael Casey, “Temperatures in the Arctic Rising Twice as Fast as Rest of the World,” CBS News, December 17, 2014.

4. Wendy Koch, “Alaska Sinks as Climate Change Thaws Permafrost,” USA Today, December 16, 2013.

5. “Permafrost In a Warming World,” Weather Underground, accessed 10–28–2016, https://www.wunderground.com/resources/climate/melting_permafrost.asp.

6. “Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle: Questions and Answers,” EPA.gov, May 2014, https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/greenhouse-gas-emissions-typical-passenger-vehicle

7. “Permafrost In a Warming World,” Weather Underground.

8. Koch, “Alaska Sinks.”

9. Ibid.

10. “Alaska Native Villages: Most Are Affected by Flooding and Erosion, but Few Qualify for Federal Assistance,” US General Accounting Office Report to Congressional Committees, (Washington, DC: USGAO, December 12, 2003).

11. “Alaska Native Villages: Limited Progress Has Been Made on Relocating Villages Threatened by Flooding and Erosion,” US Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters (Washington, DC: USGAO, June 3, 2009), newtok’s.

12. “Alaska Native Villages: Most Are Affected,” USGAO.

13. Mike Marsh quoted in David A. Fahrenthold, “Federal Employee Mike Marsh’s Mission: Getting Himself Fired, and His Agency Closed,” Washington Post, September 26, 2013.

14. White House initiative quotes from “Fact Sheet: President Obama Announces New Investments to Combat Climate Change and Assist Remote Alaskan Communities,” Whitehouse.gov, September 2, 2015, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/09/02/fact-sheet-president-obama-announces-new-investments-combat-climate.

15. Suzanne Goldberg, “America’s First Climate Refugees,” The Guardian, accessed October 28, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/interactive/2013/may/13/newtok-alaska-climate-change-refugees.

16. Lisa Demer, “The Creep of Climate Change,” Alaska Dispatch News, August 29, 2015, https://www.adn.com/rural-alaska/article/threatened-newtok-not-waiting-disintegrating-village-stages-move-new-site/2015/08/30/.

17. Alana Semuels, “The Village That Will Be Swept Away,” Atlantic, August 30, 2015.

18. Charles Enoch, “Newtok Feeling Nervous about Relocation Timeline,” Alaska Public Media, September 21, 2015.

19. “Impossible Choice Faces America’s First ‘Climate Refugees,’” National Public Radio, All Things Considered, May 18, 2013.

20. Cynthia McFadden, Jake Whitman, and Tracy Connor, “Washed Away: Obama’s Arctic Visit Buoys Climate Refugees,” NBC Nightly News, September 1, 2015, http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/fight-for-the-arctic/obamas-arctic-trip-buoys-climate-refugees-n413726.

21. Charles P. Pierce, “Shishmaref, Alaska Is Still Falling into the Sea,” Esquire, December 10, 2014, http://www.esquire.com/news-politics/politics/a32091/the-lessons-from-a-dying-village/.

22. McFadden, Whitman, and Connor, “Washed Away.”

23. Alex DeMarban, “Eroding Alaska Village Urges Congress to Address Climate Change,” Alaska Dispatch News, January 16, 2014, https://www.adn.com/environment/article/eroding-alaska-village-urges-congress-address-climate-change/2014/01/17/.

24. Ibid.

25. McFadden, Whitman, and Connor, “Washed Away.”

26. Stephen Sackur, “The Alaskan Village Set to Disappear Under Water in a Decade,” BBC News, July 30, 2013, http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-23346370.

27. “Shishmaref Residents Vote to Move Village,” Associated Press, July 21, 2002, http://peninsulaclarion.com/stories/072102/ala_072102alapm0020001.shtml#.WBek-slcj5M.

28. Adam Wernick, “Will These Alaska Villagers Be America’s First Climate Change Refugees?” Public Radio International, August 9, 2015, http://www.pri.org/stories/2015–08–09/will-residents-kivalina-alaska-be-first-climate-change-refugees-us.

29. “Kivalina lawsuit (re: global warming),” Business & Human Rights Resource Center, June 26, 2013, http://business-humanrights.org/en/kivalina-lawsuit-re-global-warming.

30. Wernick, “Will These Alaska Villagers?”

31. “Kivalina lawsuit (re: global warming),” Business & Human Rights Resource Center.

32. Lawrence Hurley, “U.S. Supreme Court Declines to Hear Alaska Climate Change Case,” Reuters, May 20, 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/usa-court-climate-idUSL2N0DW2B020130520.

33. Bill McKibben quote is a book endorsement on Amazon.com for Christine Shearer’s, “Kivalina: A Climate Change Story,” Haymarket book reviews, July 2011.

34. Wernick, “Will These Alaska Villagers?”

35. Pierce, “Shishmaref, Alaska.”

36. Jillian Rogers, “Arts Organization to Give Kivalina $500,000 Grant for Relocation,” Alaska Dispatch News, July 26, 2015, https://www.adn.com/rural-alaska/article/arts-organization-give-kivalina-500000-grant-relocation/2015/07/26/.

37. Don Callaway, “The Long-Term Threats from Climate Change to Rural Alaskan Communities,” Alaska Park Science 12, no. 2: Climate Change in Alaska’s National Parks, http://www.nps.gov/articles/aps-v12-i2-c15.htm.

38. Andrew Freedman, “This Louisiana Tribe Is Now America’s First Official Climate Refugees,” Mashable, February 18, 2016, http://mashable.com/2016/02/18/america-first-climate-refugees/#BdWnBWOIHiqL.

39. Shirley Laska et al., “Layering of Natural and Human-Caused Disasters in the Context of Sea Level Rise: Coastal Louisiana on the Edge,” in Michelle Companion, ed., Disaster’s Impact on Livelihood and Cultural Survival: Losses, Opportunities, and Mitigation (CRC Press, 2015), 227.

40. Rick Jervis, “Louisiana Bays and Bayous Vanish from Nautical Maps,” USA Today, February 12, 2014.

41. Bob Marshall, “New Research: Louisiana Coast Faces Highest Rate of Sea-Level Rise Worldwide,” The Lens, February 21, 2013.

42. Bob Marshall, Brian Jacobs, and Al Shaw, “Losing Ground,” ProPublica and The Lens, August 28, 2014, http://projects.propublica.org/louisiana/.

43. Ibid.

44. Freedman, “This Louisiana Tribe.”

45. Terri Hansen, “Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Get $48 Million to Move Off of Disappearing Louisiana Island,” Indian Country Today, February 5, 2016.

46. Sue Sturgis, “Losing Its Land to the Gulf, Louisiana Tribe Will Resettle with Disaster Resilience Competition Award Money,” Facing South (February 9, 2016) https://www.facingsouth.org/2016/02/losing-its-land-to-the-gulf-louisiana-tribe-will-r.html.

47. Freedman, “This Louisiana Tribe.”

48. Heath Allen, “Vanishing Tribe: Coastal Erosion Threatens Survival of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw,” WDSU, February 22, 2016, http://www.wdsu.com/article/vanishing-tribe-coastal-erosion-threatens-survival-of-biloxi-chitimacha-choctaw/3384770.

49. Sue Sturgis, “Losing Its Land to the Gulf, Louisiana Tribe Will Resettle with Disaster Resilience Competition Award Money,” Institute for Southern Studies, February 9, 2016.

50. Freedman, “This Louisiana Tribe.”

51. Allen, “Vanishing Tribe.”

52. Ibid.

53. Bob Marshall, Al Shaw, and Brian Jacobs, “Louisiana’s Moon Shot,” ProPublica and The Lens, December 8, 2014, http://projects.propublica.org/larestoration.

54. Ibid.

55. Bob Marshall, “New Research.”

56. Marshall, Shaw, and Jacobs, “Louisiana’s Moon Shot.”

57. Robert McLean and Irene Chapple, “BP Settles Final Gulf Oil Spill Claims for $20 Billion,” CNN Money, October 16, 2015, http://money.cnn.com/2015/10/06/news/companies/deepwater-horizon-bp-settlement/.

58. Jervis, “Louisiana Bays and Bayous.”

59. Nathaniel Rich, “The Most Ambitious Environmental Lawsuit Ever,” New York Times, October 2, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/10/02/magazine/mag-oil-lawsuit.html?_r=0.

60. Ibid.

61. “As Louisiana’s Coastline Shrinks, a Political Fight over Responsibility Grows,” PBS Newshour, May 27, 2014.

62. Annie Snider, “Levee Board Picks Fight with Oil and Gas Industry, Roiling La.,” E&E News, August 28, 2013.

63. “As Louisiana’s Coastline Shrinks.”

64. “Judge Rejects Suit over Louisiana Drilling,” Associated Press, February 13, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/14/us/judge-rejects-suit-over-louisiana-drilling.html.

65. Mark Schleifstein, “Federal Judge Dismisses Levee Authority’s Wetlands Damage Lawsuit against Oil, Gas Companies,” Times-Picayune, February 13, 2015, http://www.nola.com/environment/index.ssf/2015/02/federal_judge_dismisses_east_b.html.

66. Mark Schleifstein, “Jefferson, Plaquemines Parishes File Wetland Damage Lawsuits against Dozens of Oil, Gas, Pipeline Companies,” Times-Picayune, November 12, 2013, last updated March 15, 2016, http://www.nola.com/environment/index.ssf/2013/11/jefferson_plaquemines_parishes.html.

67. Cain Burdeau, “Louisiana Parish Drops Suits against Oil and Gas Companies,” Associated Press, November 12, 2015, http://www.bigstory.ap.org/article/9c4fa662ee4c4a5585e12495fb39adcd/louisiana-parish-drops-suits-against-oil-and-gas-companies.

68. Burdeau, “Louisiana Parish Drops Suits.” http://www.bigstory.ap.org/article/9c4fa662ee4c4a5585e12495fb39adcd/louisiana-parish-drops-suits-against-oil-and-gas-companies.

69. Snider, “Levee Board Picks Fight.”

70. Linda Qiu, “Direct Revenues from Offshore Oil and Gas Drilling to Increased Coastal Hurricane Protection,” Politifact, August 20, 2015.

71. “President Proposes $13.2 Billion Budget for Interior Department,” Office of the Secretary of Interior, February 2, 2015 https://www.doi.gov/news/pressreleases/president-proposes-13–2-billion-budget-for-interior-department.

72. Kelsey Snell, “Republicans Reject Obama Budget, Facing Spending Fights of Their Own,” Washington Post, February 9, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/powerpost/wp/2016/02/06/republicans-ready-to-reject-obama-budget-facing-spending-fights-of-their-own/.

73. Marshall, Shaw, and Jacobs, “Louisiana’s Moon Shot.”

74. Allison Plyer, “Facts for Features: Katrina Impact,” The Data Center, August 28, 2015.

75. “Mapping Migration Patterns post-Katrina,” Times-Picayune, http://www.nola.com/katrina/index.ssf/page/mapping_migration.html.

76. Laura Bliss, “10 Years Later, There’s So Much We Don’t Know about Where Katrina Survivors Ended Up,” City Lab, August 25, 2015, http://www.citylab.com/politics/2015/08/10-years-later-theres-still-a-lot-we-dont-know-about-where-katrina-survivors-ended-up/401216/.

77. Jonathan Tilove, “Five Years after Hurricane Katrina, 100,000 New Orleanians Have Yet to Return,” Times-Picayune, August 24, 2010, http://www.nola.com/katrina/index.ssf/2010/08/five_years_after_hurricane_kat.html.

78. Lynn Weber, “No Place to Be Displaced: Katrina Response and the Deep South’s Political Economy,” Institute for Southern Spaces, August 17, 2012, https://southernspaces.org/2012/no-place-be-displaced-katrina-response-and-deep-souths-political-economy.

79. Ibid.

80. Bliss, “10 Years Later.”

81. Kristin Carlisle, “It’s Like You’re Walking but Your Feet Ain’t Going Nowhere,” National Housing Institute, Fall 2006, http://www.shelterforce.org/article/729/its_like_youre_walking_but_your_feet_aint_going_nowhere/.

82. Daniel J. Hopkins, “Flooded Communities: Explaining Local Reactions to the Post-Katrina Migrants,” Political Research Quarterly 20, no. 10 (2011): 1–17; Ryan Holey-well, “No, Katrina Evacuees Didn’t Cause a Houston Crime Wave,” Houston Chronicle, August 26, 2015.

83. David Roberts, “Hurricane Katrina Showed What ‘Adapting to Climate Change’ Looks Like,” Vox, August 24, 2015, http://www.vox.com/2015/8/24/9194707/katrina-climate-adaptation.

84. “New Orleans Ten Years after the Storm: African Americans and Whites Live Differing Realities,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, August 10, 2015, http://kff.org/infographic/new-orleans-ten-years-after-the-storm-african-americans-and-whites-live-differing-realities/.

85. “Hurricane Sandy Fast Facts,” CNN Library, CNN.com, November 2, 2016 http://www.cnn.com/2013/07/13/world/americas/hurricane-sandy-fast-facts/.

86. Patrick McGeehan and Griff Palmer, “Displaced by Hurricane Sandy and Living in Limbo,” New York Times, December 6, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/07/nyregion/displaced-by-hurricane-sandy-and-living-in-limbo-instead-of-at-home.html.

87. Russ Zimmer, “Report: Thousands of Sandy Families Waiting on State,” Asbury Park Press, February 4, 2015, http://www.app.com/story/news/local/2015/02/04/sandy-recovery-report/22885571/; “The State of Sandy Recovery Two and a Half Years Later, Over 15,000 Families Still Waiting to Rebuild,” Fair Share Housing Center Second Annual Report, February 2015.

88. “The State of Sandy Recovery Fixing What Went Wrong with New Jersey’s Sandy Programs to Build a Fair and Transparent Recovery for Everyone,” Fair Share Housing Center, Housing and Community Development Network of New Jersey, Latino Action Network, and NAACP New Jersey State Conference, January 2014.

89. Andrea Thompson, “Storm Surge Could Flood NYC 1 in Every 4 Years,” Climate Central, April 25, 2014, http://www.climatecentral.org/news/storm-surge-could-flood-nyc-1-in-every-4-years-17344.

90. Ibid.

91. “Sea Level Rise Accelerating in U.S. Atlantic Coast,” USGS.gov, June 24, 2012, https://www.usgs.gov/news/sea-level-rise-accelerating-us-atlantic-coast.

92. Kevin E. Trenberth, John T. Fasullo, and Theodore G. Shepherd, “Attribution of climate extreme events,” Nature Climate Change 5, June 22, 2015.

93. Thompson, “Storm Surge.”

94. “Explaining Extreme Events of 2012 from a Climate Perspective,” Special Supplement to the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 94, no. 9 (September 2013).

95. Joe Romm, “Superstorm Sandy’s Link to Climate Change: ‘The Case Has Strengthened’ Says Researcher,” ThinkProgress, October 28, 2013, https://thinkprogress.org/superstorm-sandys-link-to-climate-change-the-case-has-strengthened-says-researcher-f80927c1d033#.3b7smjj0w.

96. “Risks of Hurricane Sandy–like Surge Events Rising,” Climate Central, January 24, 2013, http://www.climatecentral.org/news/hurricane-sandy-unprecedented-in-historical-record-study-says-15505.

97. Lydia O’Connor, “More Than 400 U.S. Cities May Be ‘Past the Point of No Return’ with Sea Level Threats,” Huffington Post, October 13, 2015, last updated October 14, 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/us-cities-sea-level-threats_us_561d338fe4b0c5a1ce60a45c.

98. Victoria Herrmann, “America’s Climate Refugee Crisis Has Already Begun,” Los Angeles Times, January 25, 2016, http://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-0125-herrmann-climate-refugees-20160125-story.html.

99. “State Mitigation Plan Review Guide,” Federal Emergency Management Agency, March 2015.

100. Avery G. Wilks, “Columbia Has Extensive Flood Recovery Wish List,” The State, March 1, 2016.

101. Rich McKay, “At Least 17 Dead as Flooding Threat Persists in South Carolina,” Reuters, October 7, 2015.

102. 2014 National Climate Assessment, US Global Change Research Program.

103. Neena Satija, Kiah Collier, Al Shaw, and Jeff Larson, “Hell and High Water,” Texas Tribune and ProPublica, March 3, 2016.

104. Dave Boyer, “Bobby Jindal Blasts New FEMA Rule on Climate Change,” Washington Times, March 24, 2015, http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2015/mar/24/bobby-jindal-blasts-new-fema-rule-climate-change/.

105. Ibid.

106. Tristram Korten, “In Florida, Officials Ban Term ‘Climate Change,’” Florida Center for Investigative Reporting, March 8, 2015, http://fcir.org/2015/03/08/in-florida-officials-ban-term-climate-change/.

107. Lydia Wheeler, “Feds to Require Climate Change Plans for States Seeking Disaster Relief,” The Hill, May 5, 2015, http://thehill.com/regulation/241050-gop-lawmakers-ask-fema-to-explain-new-disaster-grant-requirement.

108. “Scientist Predicts Mass Exodus of Climate Refugees to Pacific Northwest,” Global News, January 2, 2015, http://globalnews.ca/news/1750950/scientist-predicts-mass-exodus-of-climate-change-refugees-to-pacific-northwest/.

109. Cliff Mass, “Will the Pacific Northwest Be a Climate Refuge under Global Warming?” Cliff Mass Weather Blog, July 28, 2014, http://cliffmass.blogspot.ca/2014/07/will-pacific-northwest-be-climate.html.

110. Knute Berger, “Climate Refugees Are Coming to the Pacific Northwest,” September 16, 2014, Crosscut.com, http://crosscut.com/2014/09/climate-refugees-pacific-nw-knute-berger/.

111. Ernest Callnbach, Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports of William Weston (Berkely, CA: Banan Tree Books, 1975).

112. Paolo Bacigalupi, The Water Knife (New York: Vintage Books, 2016).

113. “What If the Drought Doesn’t End? ‘The Water Knife” Is One Possibility,” NPR.org, May 23, 2015, http://www.npr.org/2015/05/23/408756002/what-if-the-drought-doesnt-end-the-water-knife-is-one-possibility