Current refugee laws are unwelcoming to environmental refugees, but the severity of their plight deserves attention, especially in light of its predicted increase in the coming decades.

Amanda Doran, Villanova Environmental Law Journal

As actors on the world stage, refugees are hardly the helpless victims described by NGOs. Rather, they are diasporic communities that evolve and change the cultures they find themselves in, sharpen nationalistic perceptions, and make significant cultural contributions to art, poetry, and theater. Despite the cant of “right of return” or repatriation by international agencies, transfers of environmental refugees involving either repatriation or resettlement in a new country defy political reality and bump hard against economic fear and sectarian prejudice.

When people flee to escape conflicts or natural disasters, they suffer some of the most traumatic of human experiences. But flight in many cases outweighs the suffering and abuse of returning. Small wonder that thousands of IDPs cross borders, sea barriers, and dangerous landscapes in search of a better life. Those who remain behind “exist” in squalid, overcrowded camps. In Iraq, for example, some 1.9 million people have been displaced, uprooted by wars, the creation of dams and mines, and drought. An additional two million have fled Iraq to neighboring countries. As representatives for the International Migration Organization point out, “There is a fundamental interdependency between migration and the environment.”1 Yet without water or food as a result of drought or flooding, what other options are available?

In August 2005 Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans and the Gulf Coast with a twenty-eight-foot storm surge that left only a few structures along the coast standing. New Orleans survived the initial hit but was heavily flooded. As levees were breached, the swirling waters flooded neighborhoods, leaving people stranded on rooftops. All told, during the course of the storm, over one million people were evacuated from New Orleans and small towns in rural and resort coastal areas.

After the storm subsided, it was widely assumed in the media and among government agencies that people who left New Orleans and other towns along the coast would return to reclaim their homes and rebuild their flood-stricken lives. Several hundred thousand did not. They had neither job nor home to return to. Thus hundreds of thousands of Americans had transitioned from the role of evacuees to that of climate refugees.

This was not the first time that Americans had been overwhelmed by their environment and had to seek refuge elsewhere. The Dust Bowl of the 1930s in the American Midwest disrupted the lives of over two million people and propelled more than 250,000 Americans in search of a better life in California and in the Pacific Northwest.

Katrina’s refugees settled mostly in Texas, a new and unfamiliar environment. Given that these climate refugees were poor, African American, or aged, they were not exactly welcomed enthusiastically in Texas. The state was already in the grip of a nativist-localist mentality because of large numbers of legal and illegal immigrants from Mexico and Latin America generally in their midst. Houston absorbed most of the refugees and at times suffered from compassion fatigue. But a 2007 survey of 765 Houston-area residents by Rice University sociologist Stephen Klineberg found that three-fourths believed that helping the refugees put a “considerable strain” on the community, and two-thirds blamed evacuees for a surge in violent crime. Half thought Houston would be worse off if evacuees stayed, while one-fourth thought the city would be better off.2

Houston police reported an increase of 32 percent over the previous year in the murder rate in the first year after the Katrina refugees’ arrival. According to Houston Police Chief Harold Hurtt, refugees were involved—as victims or suspects—in 35 of the 212 murders in that time period. In January 2006, Houston police arrested eight members of rival New Orleans gangs in the murders of eleven fellow refugees. In March, half of the eighteen people arrested in an auto theft sweep were evacuees.3 Hurtt said some of the crime wave was attributable to Katrina refugees, but added, “I don’t mean to send the message that all Katrina evacuees are involved in drug dealing, gangs and violent offenses.”4 Klineberg observed, that the arrival of 150,000 refugees, 90 percent of whom were black, did contribute to “a palpable rise in racial tensions.”5

Significantly, fifteen thousand of the refugees in Houston were of Vietnamese descent and were easily absorbed by the large Houston Vietnamese community of sixty thousand families. According to sociologist Klineberg, the city of Houston ultimately adjusted to the refugee influx but only with a high degree of social tension and compassion fatigue. Also, he found that many Houstonians, white and black, had helped Katrina victims at the height of the crisis. After a passage of ten years, Klineberg noted a moderation of feelings toward the refugees who still remained in Houston.6

It is a mistake to assume that climate change will not be a problem for affluent countries like the United States. Houston itself is a “sitting duck” for the next great hurricane on the level of Hurricane Katrina, notes a joint investigation from the Texas Tribune and ProPublica.7 With global warming the United States will face ferocious storm patterns, extensive droughts, and tidal incursions that will engulf large areas of coastal land. Loss of vital wetland regions may bring about the collapse of ocean fisheries. In turn, populations from coastal areas will be on the move, and the United States will face a new phenomenon: the internally displaced climate refugee. The United States may have to struggle to resettle millions of its own citizens who have been displaced by high water in the Gulf of Mexico, South Florida, and much of the Atlantic coast reaching toward New England.

Haiti experienced a devastating 7.0 magnitude earthquake in January 2010. Leaving a death toll of some 250,000 and a billion dollars in damage, the earthquake was the strongest Haiti had experienced in two centuries. The US Department of Homeland Security granted “temporary protective status,” or TPS, to 100,000 Haitians who were residing illegally in the States.8 It did not admit Haitians as “refugees” or provide protection for those crossing the border illegally. (“Environmentally-forced migrants,” notes Villanova legal scholar Amanda Doran, “do not fit the traditional refugee definition, and consequently, many countries refuse to grant them asylum.”) But TPS is no solution, and like other situations and events, these “special cases” are a way of getting around the American animus toward accepting refugees. Haiti had previously requested—and been denied—several requests for TPS after tropical storms and hurricanes killed hundreds, decimated Haiti’s food crops, and caused a billion dollars in damage. Nevertheless, the Haitian earthquake did place the dilemma of the climate refugee in the world’s forefront, concludes Doran, “making it impossible to ignore and begging the international community for a solution.”9

In the summer of 2015 Europe was flooded with migrants and refugees, most of whom were fleeing Syria’s bloody civil war. While either terrified or suspicious populations greeted many of these refugees, afraid that their economies could not support a massive poor influx of migrants, Germany was a notable exception. In its actions it has shown one alternative that may be used in dealing with climate refugees. Germany decided to take in nearly one million migrants. Instead of causing physical chaos in the country, leaders believed that the migrants would uplift the country. Germany’s birth rate is the lowest in the world and its workforce is rapidly aging. Many of the Syrian refugees had money, education, and training, according to Sigmar Gabriel, Germany’s vice chancellor.10 Resettling and assimilating these migrants is costly; over time, Germany expected to spend $7 billion.

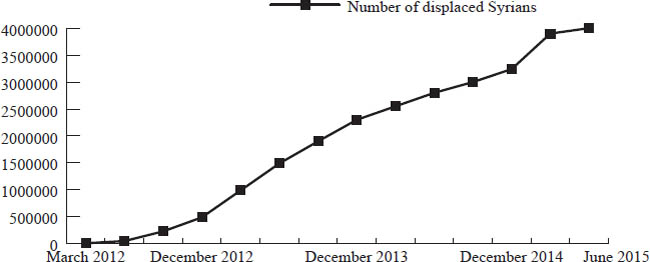

Figure 9.1: Syrian refugee crisis reaches new heights. Source: UNHCR.

A large and growing body of evidence, according to Fortune magazine, suggests “accepting refugees is often economically savvy.”11 Immigrants start businesses more often than native citizens, and they don’t usually linger to collect unemployment. Also, they have a powerful motivation in getting a second chance on life. Refugee success in a new land often takes time. For the first five years, immigrants struggle even to maintain the lifestyle and economic position of the old country. But after ten years in the new land, refugees are often more prosperous than they had ever been prior to migrating.

Not all climate refugees will fare as well as those who manage to make it to Germany. Millions will be washed up in new and strange surroundings like flotsam and jetsam. The new host environment, either within a new region of the native land or in a new country, may cast the refugee into a life of hardship. Especially if climate refugees come from the countryside into the city, they will be cast into an alien environment. Many will have difficulty surviving if they lack decent housing and access to services. There is a high risk, reports Christian Aid, that “they will fall into chronic poverty, passed on from one generation to another.”12 The situation is particularly dire in countries like Columbia, Myanmar, and Mali, where political corruption, paramilitary activity, and climate change work together as a perfect storm for the displacement of thousands of people. Many are driven off their farms with the simple deadly admonition, “If you don’t sell to us, we will negotiate with your widow.”13 The right to return to their homes after an environmental or military calamity is supposed to be a fundamental right of all internally displaced people. But the reality is that once your land is stolen, you can expect only impoverishment with no help from the state.

A similar reality awaits refugees at the Mae Ra Luang camp on the Thai-Myanmar border. At least thirty-five hundred refugees have come to this camp and more are coming. Myanmar is one of the poorest countries in the world, but nearly half of its government’s budget is spent on the military.14 Over 10 percent of Myanmar’s children die before their fifth birthday from disease and malnutrition. Land that could be used for much-needed food production has been turned into palm oil plantations. Meanwhile, Myanmar maintains one of the largest armies in Asia even though it has no neighbors who pose a threat.

The change in rainfall patterns in Mali, Africa, is creating a new wave of migrants who are being driven from their homes in search of water.15 As refugees leave their native villages, they must sever close family ties and a strong sense of community that helped to sustain16 them while they eked out a living. In recent years droughts have diminished harvests. Every year more people leave for good. There is just not enough food to survive the dry season. At one time the farmers of Mali could predict the rains and plant accordingly. Now the rains disappear in the middle of the growing season with disastrous results. Thus a twin development occurs as the land is lost and with it subsequent generations that gave the region culture and subsistence.

The most striking thing about today’s migration crisis is that it is expected to get bigger. Even if Western nations are able to absorb the millions of migrants from Syria and the Middle East, millions will be coming from Eritrea, Libya, and North Africa generally. A recent poll of Nigerians found that 40 percent of all Nigerians would migrate if they could. Borders in the Middle East and Africa that were drawn by colonial powers years ago are breaking down as climate change roils societies. In a recent article on the global migration crisis by New York Times international correspondent Rod Norland, Sonja Licht of the International Center for Democratic Transition observed, “The global north must be prepared that the global south is on the move, the entire global south. This is just not a problems for Europe but for the whole world.”17

It is difficult to create transborder temporary refugee sanctuaries. Host nations are sometimes suspicious of them, and xenophobes point out that “temporary” easily morphs into “permanent” camps as experiences in Palestine and Jordan and South Pacific post-atomic islands suggest. It is difficult to inculcate an idea that refuge is in itself “temporary” especially if that camp is in an affluent host country. Also with “temporary refuges” come issues of freedom of movement of climate refugees and others in host countries. Freedom of movement for climate refugees or others can deteriorate from a humanitarian concern to one of national and regional security.

The consequence of large numbers of climate refugees will most likely be among “the most significant of all upheavals entrained by global warming,” argues environment scholar Norman Myers.18 Refugees arrive with a host of different religious and cultural practices. Resettlement, Myers says, is difficult, and “full assimilation is rare.”19 Economic and political upheavals will likely proliferate. Ethnic problems will multiply. “The political fallout would be extensive.”20 Whatever form it takes, resettlement will be expensive, costing developing nations over $20 billion to accommodate climate refugees. Plus significant financial outlays will be needed to combat pandemic diseases as well as problems with allocating food and water.

Even under the best of conditions, resettlement is not an easy process. It is costly, and refugees seldom have the skill sets required for a new life in a new country. It was found that even during the period of postwar sympathy for displaced persons, states were disinclined to accept groups so large as to resist absorption. As Jane McAdam notes in a recent article, “The political and practical obstacles that stood in the way of relocation in the past still remain today.” Modern scholarship on resettlement shows that it is “a fraught and complex undertaking, and rarely considered successful by those who move.”21 Looking back on history it is easy to say, “This time it’s different.” But one wonders whether or not we will keep repeating the mistakes of the past regarding refugees.

The media is filled with news of the desperate exodus of thousands of Syrian refugees into Europe. While chaos will no doubt prevail in the short run, eventually European countries like Austria and Germany will sort out the problem of housing, feeding, and employing a very large displaced population. Europe accommodated nearly nine hundred thousand refugees from Kosovo and other areas of the Balkans during a multiyear civil war in what once was Yugoslavia. These refugees all fall under the purview of the Geneva Convention as political refugees from war and will receive aid and eventual placement from UN and other relief agencies. Climate refugees currently receive no such help. However, the plight of both kinds of refugees threatens to morph from a humanitarian crisis to a geopolitical one. Today many are seeking asylum in the West, and not all will receive it, because Europeans fear their culture will be overwhelmed by a foreign tide.

Once the refugees arrive safely in their final destinations—increasingly, these destinations are Italy, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Sweden—new problems arise. Syrian refugees have been facing cultural backlash in European countries and, after the ISIS terrorism attacks in Paris, around the world. But in fact the rise of ISIS was dependent on Syria’s unrest. The Islamic State, a militant Sunni jihadist group that derived from al-Qaeda, then took advantage of the unrest and opposition to the Shiite Assad government, established ground forces in Syria and rebranded itself as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. After the Paris terrorism attacks, hostility toward Syrian refugees—and other Middle Eastern refugees—kicked into overdrive.

Of the European Union, Germany had one of the most open policies for accepting refugees, handling 70 percent of asylum seekers—it received approximately one million refugees in 2015. Subsequently, Chancellor Angela Merkel faced backlash from the Germans for the open policy, and anti-immigrant sentiment swelled. In the late summer of 2015, attacks on refugee centers and refugees themselves increased. An apartment building renovated by the government and planned to house dozens of refugees was burned to the ground. The nearby residents blamed the building owner, not the arsonists, for turning the building into a shelter. In Germany latent racism was brought to the surface, particularly when refugees moved into the white, post-neo-Nazi neighborhoods of East Germany.

Sweden has seen similar acts of violence. The Nordic country received the second most Syrian asylum applications in the European Union, and it was one of the more tolerant and open countries to refugees. But as the number of refugees living in Sweden has increased over recent years, a hostile backlash has been brewing. The Sweden Democrats party, which takes an anti-immigration position, rose considerably in the polls to become the most popular party by the end of 2015. Xenophobic acts of violence were seen across the country; buildings that were supposed to become refugee asylums were burned to the ground—one building already housing refugees burned down, forcing fourteen asylum seekers to escape through the window. Other European countries have recently elected parliaments that are further to the right than previously, promoting anti-immigration policies. Poland and Denmark have joined Sweden in increasing anti-immigrant sentiment.

The xenophobia is by no means limited to the European Union. In Egypt, Syrian refugees were at first welcomed by the Islamist president Mohamed Morsi—up until the summer of 2013, when Morsi was ousted. After that the government wrongly tied the rebel Free Syrian Army—with which many Syrian refugees share common ground—to violence in Syria, and Syrians faced harassment by police and on the streets, were increasingly mugged and robbed, faced discrimination, and were clamped down on by the government. At the time, one of the only countries friendly to the Syrian refugees was Yemen, which was fraught with instability, still recovering from its own uprising.

In the United States President Donald Trump’s call to ban all Muslims entering the United States revealed uncomfortable truths about xenophobia in the country. A large segment of Republicans supported Trump, and during the presidential campaign, state governors across the country announced they would not accept Syrian refugees, although the United States had only allowed an embarrassingly small number of Syrian refugees in the country—fewer than than three thousand since 2011. The State Department planned to increase its intake to about ten thousand Syrians for 2016, but the backlash was palpable as anti-Muslim sentiment in the States increased.

American xenophobia is as old as the United States. Even during the colonial period Benjamin Franklin warned that a tide of German immigrants threatened to overwhelm colonial British American society. Franklin feared that Americans would eventually speak German. Americans have always been uncomfortable with immigrants in their midst, even though they themselves are part of the immigrant mix.22 While Americans agree on humanitarian ideas in principle, they are reluctant to put them into practice. Historically, Americans have been suspicious of Catholics, especially Irish ones; Jews; and immigrants generally of darker skin color. Ideology too has played its xenophobic part. The Cold War after 1950 spurred a rampant fear of communism in the United States and of all socialist ideologies. Refugees from national uprisings like that of Hungary in the 1950s were admitted because the American government invoked emergency powers rather than welcome them as refugees. After the Vietnam War, Americans were reluctant to admit Vietnamese refugees partly out of a fear of oriental peoples that went back to America’s Chinese Exclusion Acts of the nineteenth century.

If we adopt a long historical view, the xenophobia of our current crop of political leaders is rooted in American culture. Among our presidents, Barack Obama and Jimmy Carter have been the only national leaders to extend a welcoming hand to refugees in the modern age. President Carter, when he signed the Refugee Act of 1980, referred to the United States’ “long tradition as a haven for people uprooted by persecution and political turmoil.”23 Given the present nativist mood in the United States, however, this policy is not completely accurate.

The Syrian refugee crisis is having global ramifications, and its disastrously high numbers are fueled by climate change. While pundits may continue to bicker over whether or not these refugees can rightfully be called “climate refugees,” there is no doubt that the process of global warming is not only contributing to a deep unraveling in political stability in the Middle East but also has the possibility to do more so, in Africa and Asia and elsewhere. It is a force to be reckoned with and considered in the context of climate change in the decades ahead.

While Syria’s refugee crisis is palpable and the effects are clear, it is just one result of a crisis worsened by climate change. Many regions in the Middle East face threats from global warming—similar and unique—that could create another refugee crisis. If the world can barely handle Syria’s crisis, what will happen when this becomes even more widespread? The implications are not good.

Climate change, notes Yale historian Timothy Snyder, raises grave social dangers. A country like China with over a billion people could easily fall into an “ecological panic” and take drastic steps to protect its people and its standard of living.24 China is already buying up vast tracts of land in Africa and in the United States to guarantee food security for its people. China owns or leases a tenth of Ukraine’s arable soil and buys up food when global supplies tighten, says Snyder.25 However, nations in need of food and land could easily resort to a Hitlerian “lebensraum” policy and begin to grab farmlands and expel local native populations during times of drought or other food crises. Writes Snyder: “Nations in need of land would likely begin with tactfully negotiated leases or purchases; but under conditions of stress or acute need such agrarian export zones could become fortified colonies, requiring or attracting violence.”26

After nearly a century of effort and experience in dealing with the international movement of peoples, the old problems of hostility toward migrants remain. At this moment Europe appears to be fracturing as the migration crisis in Europe worsens. Despite all the intelligent calls for human rights conventions for migrants, the only mutually agreeable strategy for EU nations to come up with is to pay Turkey to care for the millions of migrants in its territory and keep them there. The Balkan approach has been to build border fences across Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, and Macedonia. Meanwhile, Germany, a generous country that has admitted a million migrants, suffers a nativist backlash that could unseat Chancellor Angela Merkel and pull out the immigration welcome mat.

Humanitarian agencies argue that planned or managed relocation is increasingly being seen as a logical and legitimate climate change adaptation strategy.27 Critics fear the creation of refugee “gulags” in their countries while proponents of the idea see managed relocation as a means of acculturation, adaptation, and rehabilitation from the onslaught of environmental hazards. It is important to raise worldwide knowledge-based public awareness of the issue and its social and economic dimensions. People need to realize that climate refugees are first people who have faced real hardships. They have not come to a new country to “steal” people’s livelihoods.28 This is the kind of awareness that needs to be generated by heads of states and humanitarian agencies. One of the fundamental problems that we see today is that while migration from an environmentally ruined area to a more prosperous one is often championed as a “human right,” currently the right of a country to protect and secure its borders is enshrined in international law. Whether people can be admitted to another state in a disaster context and seek assistance and stay for an undetermined period is a key question.

In Wiesbaden, Germany, today you can see the remnants of the great fortified wall that was built by centurions in the declining days of the Roman Empire to keep the barbarians out. Over the course of time the wall was notoriously unsuccessful in its mission. Goths, Visigoths, and other tribes poured into Rome’s dominions and the empire collapsed. Today a specter is haunting Europe, a specter of a proud, optimistic, and moral Europe falling victim to climate change and demographics. In Paris, Rome, Brussels, Stockholm, and Berlin, the question uttered by people on the street is pretty much the same: “Can Europe protect its citizens? Can Europe protect its borders?”

Climate refugees come from a variety of classes and cultures. The specter of wholesale relocation of diverse populations raises fundamental questions about citizenship and nationality. Once land has been lost, will a residual nationality be able to persist? In the event of a wholesale evacuation, as in the case of island nations, what happens to an abandoned country’s exclusive economic zone, its territorial waters and nationhood? It is not easy to carve out new space for a nation. The experiences of Israel, Palestine, the Ukraine, Pakistan, and Bangladesh attest to this.

A recent Brookings Institution report states that Pacific Island countries are regarded as “a barometer of the impacts of climate change.”29 For the people of these islands, climate change means an assault on their homes and livelihoods. The residents of the Cook Islands in the South Pacific, for example, do not want to leave their homes because of rising sea levels. They fear that if they leave their islands, their entire way of life, including their language and customs, will become extinct. Small wonder that Pacific Island leaders like Anote Tong of the Republic of Kiribati have been in the forefront of demands for developed nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Islanders are also exploring means of adapting to climate change through change in local infrastructure—from sea walls to new techniques to stem beach erosion, such as planting sturdy seashore grasses and rebuilding wetlands.

Cross-border migration means loss of home, and it is a sensitive issue especially in Mexico and other parts of Latin America where droughts and storms have propelled millions northward to the United States. And now, despite numerous difficulties—climatic, financial, and political—Mexicans are returning home. According to a recent Pew Research Report, more Mexicans have returned to Mexico than migrated to the States since the recession of 2008: “From 2009 to 2014 1 million Mexicans and their families (including U.S.-born children) left the United States for Mexico.”30 This exceeded those 870,000 migrants heading northward. The main reason given by Mexicans for their return was the preservation of home and family. In “el Norte” Mexicans, for example, have difficulty maintaining their culture across the generations. Mexican American youth take on the cultural attributes of the dominant American culture to the dismay of their elders. Thus Mexican immigrants share many of the same concerns as the Cook Islanders as elucidated by Jane McAdam.31

A 1998 report by the IPCC stated that a one-meter rise in sea levels would inundate three million hectares of land in Bangladesh, displacing fifteen to twenty million people. The Mekong Delta in Vietnam could lose two million hectares of land, ultimately displacing nearly ten million people. In West Africa nearly 70 percent of the coast would be inundated by a one-meter rise. Further, the same rise in sea level in Shanghai would displace nearly six million of the city’s seventeen million people. Will there be boards of international equity for resettlement to help these people?

Other kinds of migrants in the future will be from countries that have ceased to exist—some sunk into rising seas, others succumbing to tsunamis, flooding, or desertification. Storms swell rivers; they wash away the soil and create new flood plains. Economic survival on changing environmental landscapes becomes increasingly problematic. Numerous questions arise about these migrants. Can a whole nation ever pack up and leave? Can a citizenry exist if their country is no longer on the map?

As McAdam has noted, without systematic approaches to the problems engendered by climate change, “there is a risk that regional concerns become diluted or homogenized to some abstract ‘universal experience,’ and with the loss of nuance comes the loss of appropriate interventions.”32

The question is whether some tipping point will send a surge of “environmental asylum seekers” or if climate change will merely boost some population increases that are manageable. If refugees materialize in significant numbers, will they receive sanctuary? Past history of this subject is not comforting.

Amanda A. Doran, “Where Should Haitians Go—Why Environmental Refugees are up the Creek without a Paddle,” Villanova Environmental Law Journal, 22(11), p. 132, available at http://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1015&context=elj

1. International Organization for Migration, “A Complex Nexus,” http://www.iom.int/complex-nexus.

2. Associated Press, “Katrina Evacuees’ Welcome Wearing Thin in Houston,” March 29, 2006, http://www.foxnews.com/story/2006/03/29/katrina-evacuees-welcome-wearing-thin-in-houston.html.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Stephen Kleinberg, “Four Myths about Katrina’s Impact on Houston,” August 26, 2015, https://urbanedge.blogs.rice.edu/2015/08/26/four-myths-about-katrinas-impact-on-houston/#.WI9647YrKRs.

6. Ibid.

7. Neena Satija, Kiah Collier, Al Shaw, and Jeff Larson, “Hell and High Water,” Pro-Publica, March 3, 2016, https://www.propublica.org/article/hell-and-high-water-text.

8. Amanda A. Doran, “Where Should Haitians Go—Why Environmental Refugees are up the Creek without a Paddle,” Villanova Environmental Law Journal, 22(11), p. 132, available at http://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1015&context=elj132.

9. Ibid.

10. Henry Chu, “For Germany, Refugees Are a Demographic Blessing as Well as a Burden,” Los Angeles Times, September 10, 2015.

11. Jon M. Jachimowicz, “The Link between Europe’s Migrant Crisis and the Climate Change Debate,” Fortune, November 11, 2015.

12. Roberta Cohen, “Human Tide: The Real Migration Crisis,” Christian Aid Report, May 2007: 30, https://www.christianaid.org.uk/Images/human-tide.pdf.

13. Ibid: 31.

14. Ibid., p. 37.

15. Ibid., p. 40.

16. Ibid., p. 41.

17. Rod Norland, “A Mass Migration Crisis and It May Yet Get Worse,” New York Times, October 31, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/01/world/europe/a-mass-migration-crisis-and-it-may-yet-get-worse.html.

18. Norman Myers, “Environmental Refugees in a Globally Warmed World,” Bioscience 43, no. 11 (1993): 752.

19. Ibid: 759.

20. Ibid.

21. Jane McAdam, “Lessons from Planned Relocation and Resettlement in the Past,” Forced Migration Review 49 (May 2015), http://www.fmreview.org/sites/fmr/files/FMRdownloads/en/climatechange-disasters/mcadam.pdf.

22. For good background on this, see Peter Schrag, The Unwanted: Immigration and Nativism in America, ImmigrationPolicy.org, September 2010, http://www.immigrationpolicy.org/perspectives/unwanted-immigration-and-nativism-america.

23. Jimmy Carter, “Refugee Act of 1980 Statement on Signing S. 643 Into Law,” http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=33154.

24. Timothy Snyder, “The Next Genocide,” New York Times, September 12, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/13/opinion/sunday/the-next-genocide.html.

25. Ibid.

26. Timothy Snyder, “The Next Genocide,” Sunday Review, New York Times, September 12, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/13/opinion/sunday/the-next-genocide.html.

27. Brent Dobersteain and Anne Tadgell, “Guidance for ‘Managed’ Relocation,” Forced Migration Review 49, p. 27, http://www.fmreview.org/sites/fmr/files/FMRdownloads/en/climatechange-disasters/doberstein-tadgell.pdf.

28. Fabrice Renaud et al., “Environmental Degradation and Migration,” Berlin-Institut für Bevölkerung und Entwicklung, http://www.berlin-institut.org/en/online-handbookdemography/environment/environmental-migration.html.

29. Michael M. Cernea, Elizabeth Ferris, and Daniel Petz, “On the Front Line of Climate Change and Displacement: Learning from and with Pacific Island Communities,” Brookings Institution Report, London School of Economics, September 20, 2011: 1, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/09_idp_climate_change.pdf.

30. Ana Gonzale-Barrea, “More Mexicans Leaving Than Coming to the United States,” Pew Foundation Report, November 19, 2005 (material provided by Mexican National Survey of Demographic Dynamics).

31. Jane McAdam, “Pacific Islanders Lead Nansen Initiative Consultation on Cross-Border Displacement from Natural Disasters and Climate Change,” Brookings Up Front Report, May 30, 2013, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2013/05/30/pacific-islanders-lead-nansen-initiative-consultation-on-cross-border-displacement-from-natural-disasters-and-climate-change/.

32. McAdam, “Pacific Islanders.”