CHAPTER TWELVE

PSYCHIATRIC IMPERIALISM

On a sunny afternoon in 1994, a fourteen-year-old schoolgirl called Charlene Hsu Chi-Ying collapsed and died on a busy Hong Kong street. Nothing untoward appeared to have precipitated her death. She had just been walking home from school as usual.

A coroner was called in to investigate Charlene’s body. He was immediately disturbed by what he found. She only weighed seventy-five pounds. Worse still, her heart was tiny—weighing a shocking three ounces, half the usual size for a girl her age. In fact, her body looked so emaciated that nurses at the local hospital actually mistook her corpse for that of a woman in her nineties.

A public inquest was immediately undertaken to work out what had happened. What it revealed seemed shocking: Charlene had done something then practically unheard of in Hong Kong—she had starved herself to death.

After Charlene’s death, a chilling series of events started to unfold in the city. Young women suddenly seemed to begin copying Charlene’s self-starving. First it was one or two, but very quickly the numbers began to rise dramatically. What was initially considered an isolated event now appeared to turn into a citywide minor epidemic, and nobody could understand why. What was going on in Hong Kong?

That question led one of America’s foremost investigative writers, Ethan Watters, to fly to the city in the hope of unraveling the mystery. He had undertaken his preliminary research, so he knew exactly where to start his investigation—with one of Hong Kong’s leading eating disorder specialists, a physician called Dr. Sing Lee. Lee had made a career of working with patients suffering from eating disorders and was extensively knowledgeable about the events preceding and following Charlene’s death. As Watters’s conversations with Lee took place, the key facts surrounding Charlene’s death began to become clear. Here is what Watters found.176

After Charlene’s death, there was uproar in the Hong Kong media. A young schoolgirl dying in such a public way, under such odd circumstances, was bound to be irresistible for news corporations. “Girl Who Died in the Street was a Walking Skeleton,” one headline rang out; and another, “Schoolgirl Falls Dead on Street: Thinner Than a Yellow Flower.” As reporter after reporter presented the facts, most also asked the same burning question: What was the meaning of this strange disease that led a bright young local girl to starve herself to death?

As the question was turned over again and again in Hong Kong’s media circles, the phrase anorexia nervosa began to be heard. Until this time anorexia was a little-known condition in the city, only being readily diagnosed by a few Western-trained psychiatrists working in Hong Kong. But because the public wanted to know more, anyone who knew about the condition was in great demand. Psychiatrists were recruited in discussions that started appearing in women’s magazines and daily papers. Educational programs were soon set up in schools to increase awareness of the disorder. A youth support program was initiated called Kids Everywhere Like You, which included a 24-hour helpline for children struggling with eating irregularities. As these forces gained momentum in Hong Kong, the disorder was slowly put on the map. The word was getting out that anorexia nervosa was not just a Western disease—the youth of Hong Kong were susceptible as well.

As public awareness of anorexia grew in Hong Kong, so did the number of anorexia cases reported. For instance, psychiatrists like Lee, who before Charlene’s death had only seen about one case of self-staving a year, were now seeing many cases each week. As the author of one typical article noted, eating disorders were now “twice as common as shown in earlier studies and the incidence is increasing rapidly.” And as a headline in Hong Kong’s Standard also echoed when a reporter described a study of this rise: “A university yesterday produced figures showing a twenty-five-fold increase in cases of such disorders.”177

Watters was desperate to know why a disorder like anorexia, once practically unknown in Hong Kong, could suddenly become a local epidemic. The first answer he considered was that the growing media attention had brought to public attention a widespread problem that had always been there but carefully hidden, making it easier for doctors to recognize and diagnose this disorder. Perhaps until that time people had not felt permitted to report their anorexic experiences; perhaps the new discourse had given a voice to a disorder long kept underground. But as compelling as this explanation initially seemed, for Watters it didn’t appear to fit the facts.

In the first place, if there had always been many cases of anorexia in the non-clinical population, then schools, parents, psychiatrists, and pediatricians would surely have spotted it. After all, anorexia is not something that sufferers can easily hide, given its very obvious symptomatic signs. As it therefore appeared unlikely that the rise in anorexia was solely due to increased public attention, Watters considered another explanation: Perhaps as Western ideas of female beauty became dominant in the media, the accepted ideal of female beauty had begun to transmute. As women encountered more images of slim paragons alleged of perfection, they simply felt pressured to make their bodies conform.

But again, the evidence did not support this. After all, Western depictions of featherweight beauty did not rise hand in hand with anorexia cases. These depictions were widespread long before the anorexia epidemic broke out and so could not account for the sudden explosion of cases. Watters was therefore convinced that something else was going on, something less obvious, something perhaps even more disturbing. The question that continued to plague him was what could this “something” be?

2

Before we pursue that question further, let us first journey a few thousand miles from Hong Kong and a little way back in time to investigate another odd series of events occurring in Britain that I had been independently researching. The time period I was focusing on was the late 1980s, when another strange psychiatric contagion seemed to be spreading.

During this time, increasing numbers of young women started arriving in clinics up and down the country displaying severe and disturbing wounds. Some had gashes on their arms and legs, others had marks from scalding, burning, hitting, and scratching, or were missing clumps of hair. What linked all these puzzling cases was that other people weren’t inflicting these wounds. No, the young women were inflicting these wounds upon themselves.

As the 1990s and 2000s unfolded, cases of such “self-harming” behavior continued to increase dramatically. A study on the mental health of college students found empirical evidence that at one university, the rate of self-injury doubled from 1997 to 2007.178 And when the BBC reported on self-harm in 2004, it bemoaned the escalating rates in Britain: “One in ten teenagers deliberately hurts themselves and 24,000 are admitted to hospital each year.”179 A later BBC investigation also revealed that the number of young people being admitted to hospital for self-harm was up 50 percent in five years (2005–2010).180 What began as a tiny number of cases in the late 1980s had suddenly exploded beyond most people’s comprehension. The urgent question there too, was how could this be?

By the mid-2000s, many conventional explanations had been advanced to provide an answer. Dr. Andrew McCulloch, chief executive of the Mental Health Foundation, put one as follows: “The increase in self-harm … may be visible evidence of growing problems facing our young people, or of a growing inability to respond to those problems.” Susan Elizabeth, director of the Camelot Foundation, similarly pointed out: “It seems the more stresses that young people have in their lives, the more they are turning to self-harm as a way of dealing with those stresses.” Professor Keith Hawton, a psychiatrist at Oxford University, also joined in the fray: Self-harm was rising because “pressures have increased and there’s much more expected of young people.”181

Statements like these by members of the mental health establishment boiled down to the simple idea that self-harming was on the increase because teenage life-satisfaction was down. But today, with the benefit of hindsight, this explanation appears unsatisfactory. First, it is not so clear whether teenage life in the late 1980s was so much easier than it was in the late 1990s, the period during which self-harming really began to rise. On the contrary, there is strong evidence that the social conditions for teenagers during the 1990s, if not significantly improving, at least did not decline.

For instance, sociologists at Dartmouth and Warwick Universities showed that overall, general well-being in Britain actually flatlined rather than plummeted during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.182 And an independent study conducted at the University of York (commissioned by Save the Children) concluded that: “While overall the UK can claim that life is getting better for children, child wellbeing continues to be mixed: The list of improving indicators is more or less equal in length to the list of deteriorating/no-change indicators.”183

So the situation was not ideal, but at the same time neither did it seem to be declining in the 1990s and 2000s, a fact somewhat undermining establishment claims about why self-harm was on the rise. Perhaps there was something else at play that had escaped mainstream attention.

To explore some possible alternatives, I called Professor Janis Whitlock, a specialist in self-harm behavior at Cornell University. Whitlock has dedicated much research to trying to work out what makes this particular behavior attractive to young people at a particular time. “In some of our early work we found evidence of self-harming back in the early twentieth century,” said Whitlock, “but all amongst severely traumatized people like war veterans. How it shows up among otherwise normally functioning kids in the 1990s I think says a lot about our culture, what is going on in that time and place.”

The aspect of culture Whitlock focused on was how popular depictions of self-harm grew exponentially during the 1990s and 2000s. In a recent study, her team focused on representations of self-harm in the media, in popular songs, and in movies from the 1970s until 2005.184 What they found was that between 1976 and 1980, there was only one movie depicting self-harm behavior, while there were no references to it in popular songs. But between 2001 and 2005, depictions and references rose sharply, appearing in twenty-three movies and thirty-eight songs. Furthermore, when charting the rise of news articles on the issue, between 1976 and 1980 they only found eleven articles featuring self-harming, while between 2001 and 2005 this figure had soared to a whopping 1,750 articles. Was the growth of popular references to self-harm simply reflecting a growing epidemic? Or were these references actually helping spread self-harming behavior?

I put this question to Whitlock. “My educated guess was that it was the latter. In the late eighties, I don’t think self-harm was out there as an idea, so mostly the average kid’s response was ‘Eww, why would you do that?’ But when you hear people like Christina Ricci and Johnny Depp and Angelina Jolie talking about their experiences of it, the idea can become normalized. And once an idea becomes part of the repertoire of possibilities, it can easily gain traction.”

This is especially true when behavior like self-harm gains authoritative recognition from institutions like psychiatry, something that was also occurring during the 1990s. For instance, in 1994 self-harm was for the first time given prominence in the DSM as a symptom of Border Personality Disorder. This meant that a kind of behavior once peripheral to psychiatric discourse was now part of the psychiatric canon, potentially making media conversations about the behavior somewhat easier to facilitate because there was now a legion of qualified experts who could explain the behavior to a concerned public.

Was it mere coincidence that after self-harm entered the DSM in 1994 the number of popular articles on self-harm literally trebled, increasing from 485 articles in the four-year period before its inclusion to 1,441 in the four-year period after?185 “In many of the media articles we assessed,” said Whitlock, “sure, there was just plain sensationalism, you know, ‘Look at what is going on!’ But in others there was now a serious attempt to understand what was happening, and of course people turned first to the clinical world to do that.”

Whitlock gave me an example of how popular news channels like NPR recruited psychiatrists to discuss self-harming. “These would have been classic venues for exporting a psychiatric framework and language of self-harm,” said Whitlock, “and may have helped it enter public consciousness too.”

Since the rise of media reporting and psychiatric recognition of self-harm appeared to coincide with its escalating rates, one question seemed to me inevitable: Was psychiatry, by giving prominence to self-harm in the DSM, helping endorse the idea that self-harm was a legitimate way through which young people could express distress? And was this endorsement, coupled with the increasing media reports on self-harm, somehow contributing to its higher prevalence?

This was the very question plaguing Ethan Watters as he attempted to understand why anorexia soared in Hong Kong after Charlene’s death. Was there something about psychiatric recognition of the behavior, coupled with growing media attention, which was partly responsible for self-harm’s escalation? What Watters soon realized was that in order to answer this question, another matter needed settling first: If psychiatric and media publicity of a disorder could actually increase its occurrence, how did this process work? What were the mechanisms by which growing cultural awareness of a condition could lead to its proliferation?

To unravel this mystery, let’s return to Watters in Hong Kong, who was now on the brink of finding an answer.

3

As Watters continued his conversations with eating disorders expert Dr. Sing Lee, a key piece in the jigsaw puzzle at last slotted into place. One day in Lee’s office in downtown Hong Kong, Lee told Watters that he had become gripped by the work of the eminent medical historian Edward Shorter, who had written many articles on the history of anorexia. What Shorter pointed out in his writing was that rates of anorexia and the form anorexia took had never been stable in the general population. Its form and prevalence had fluctuated from period to period.

For example, in the mid-1800s anorexia did not actually exist as a distinct medical category. It was rather regarded as one of the symptoms of a broader condition, then called hysteria. This catchall term characterized a suite of symptoms, most usually afflicting middle- and upper-middle-class women, which included things like uncontrollable ticks, muscular paralysis, fainting fits, bouts of vomiting, and in many cases a complete refusal to eat food. But in 1873 an expert in hysteria, the French physician Ernest-Charles Lasègue, came to the conclusion that self-starving warranted its own official designation, as he theorized it was often a stand-alone condition.

At the time Lasègue coined the term anorexia for the first time, he also drew up a thorough description of its core symptoms and a template guiding physicians in their diagnosis and treatment of the condition. It was clear that Lasègue’s work at last provided a model, as Shorter put it, “of how patients should behave and doctors should respond.”186 The question now was whether Lasègue’s work was related to a rise in the disease.

Even though there were no epidemiological studies of anorexia rates in Lasègue’s day, what Shorter noticed was that anecdotal reports suggested that once anorexia became part of the medical canon, its diagnostic prevalence increased too. Whereas in the 1850s the disorder was still confined to just a few isolated cases, after Lasègue’s work it wasn’t long before the term anorexia became standard in the medical literature, and with this, the number of cases climbed. As one London doctor reported in 1888, anorexia behavior was now “a very common occurrence,” giving him “abundant opportunities of seeing and treating many cases”; and a medical student confidently wrote in his doctoral dissertation: “among hysterics, nothing is more common than anorexia.”187

This rise in anorexia was fascinating to Shorter because it closely followed the trajectory of many other psychosomatic disorders he had studied during his historical investigations. These disorders were also not constant in form and frequency but came and went at different points in history. This led Shorter to theorize that many disorders that did not have known physical causes and did not behave like diseases such as cancer, heart disease, or Parkinson’s, which seemed to express themselves in the same way across time and space. Rather, disorders like anorexia—with no known physical cause—seemed to be heavily influenced by historical and cultural factors. If a disorder gained cultural recognition, then rates of that disorder would increase.

This provided a challenge to the conventional explanation that a disorder could proliferate after being recognized by medicine, because doctors could now identify something previously off their radar. While it was no doubt true that once doctors knew what to look for diagnostic rates would inevitably increase, for Shorter it was essential to also consider the powerful role culture could play in the escalation of some disorders. In short, Shorter was convinced that medicine did not just “reveal” disorders that had previously escaped medical attention, but that one could actually increase their prevalence by simply putting the disorder on the cultural map.

To explain how this could happen, Shorter made use of an interesting metaphor—that of the “symptom pool.” Each culture, he argued, possessed a metaphorical pool of culturally legitimate symptoms through which members of a given society would choose, mostly unconsciously, to express their distress. It was almost as if a particular symptom would not be expressed by a given cultural group until the symptom had been culturally recognized as a legitimate alternative—that is, until it had entered that culture’s “symptom pool.” This idea could help explain, among other things, why symptoms that were very common in one culture would not be in another.

Why, for example, could men in Southeast Asia but not men in Wales or Alaska experience what’s called Koro (the terrifying certainty that their genitals are retracting into their body)? Or why could menopausal women in Korea but not women in New Zealand or Scandinavia experience Hwabyeong (intense fits of sighing, a heavy feeling in the chest, blurred vision, and sleeplessness)? For Shorter, the answer was simple: symptom pools were fluid, changeable, and culturally specific, therefore differing from place to place.

This idea implied that certain disorders we take for granted are actually caused less by biological than cultural factors—like crazes or fads, they can grip or release a population as they enter or fade from popular awareness. This was not because people consciously chose to display symptoms that were fashionable members of the symptom pool, but just that people seem to gravitate unconsciously to expressing those symptoms high on the cultural scale of symptom possibilities. And this of course makes sense, as it is crucial that we express our discontent in ways that make sense to the people around us (otherwise we will end up not just ill but ostracized).

As Anne Harrington, professor of history of science at Harvard, puts it, “Our bodies are physiologically primed to be able to do this, and for good reason: if we couldn’t, we would risk not being taken seriously or not being cared for. Human beings seem to be invested with a developed capacity to mold their bodily experiences to the norms of their cultures; they learn the scripts about what kinds of things should be happening to them as they fall ill and about the things they should do to feel better, and then they literally embody them.”188 Contagions do not spread through conscious emulation, then, but because we are unconsciously configured to embody species of distress deemed legitimate by the communities in which we live.

One of the reasons people find this notion of unintentional embodiment difficult to accept is that such processes occur above our heads—imperceptibly, unconsciously—and so we often fail to spot them. But if you still doubt the power of unintentional embodiment, then just try the following experiment. Next time you are sitting in a public space where there are others sitting opposite you, start to yawn conspicuously every one or two minutes, and do this for about six minutes. All the while, keep observing the people in your vicinity. What you’ll almost certainly notice is that others will soon start yawning too.

Now, there are many theories why this may happen (due to our “capacity to empathize,” or to an offshoot of the “imitative impulse”). But the actual truth is that no one really knows for sure why. All we do know is that those who have caught a yawning bug usually do not know they have been infected. They usually believe they are yawning because they are tired or bored, not because someone across the way has just performed an annoying yawning experiment.

Such unintentional forms of embodiment have been captured in many different theories developed by social psychologists. One theory of particular note is what has been termed the “bandwagon effect.” This term describes the well-documented phenomenon that conduct and beliefs spread among people just like fashions or opinions or infectious diseases do. The more people who begin to subscribe to an idea or behavior, the greater its gravitational pull, sucking yet more people in until a tipping point is reached and an outbreak occurs. When an idea takes hold of enough people, in other words, it spreads at an ever-increasing rate, even in cases when the idea or behavior is neither good nor true nor useful.

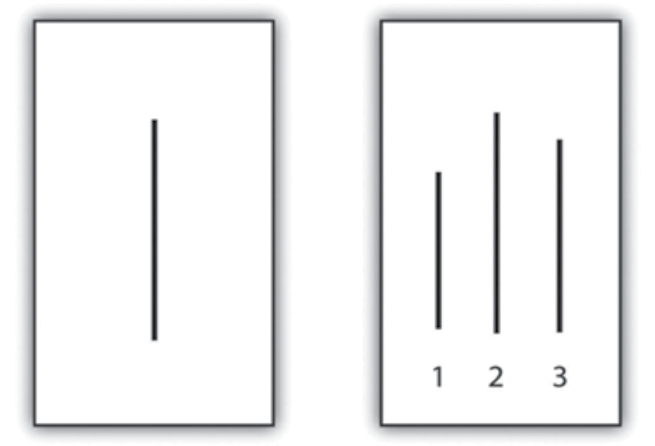

Take the following experiment as an example. Imagine that a psychologist gathers eight people around a table, but that only one of the eight people is not in on the experiment. That person is you. Everyone else knows precisely what is expected of them. What they have to do is give a prepared answer to a particular question. The question is: Which of the three lines in the box on the right most closely resembles the line on the left?

Easy, right? If you are sitting in a group where everyone is told to answer correctly, it is almost 100 percent certain that you will answer correctly too. But what would happen if you were put in a group where a sufficient number of members have been told to give an incorrect answer with sufficient forcefulness to many such slides? Unbelievable as it sounds, at least one-third of you will begin to give incorrect answers too. You will conclude, for instance, that the line in the box on the left resembles the line numbered 1 or 3 on the right.

Psychologist Solomon Asch demonstrated this bemusing occurrence by conducting this very experiment. His aim was to show that our tendency to conform to the group is so powerful that we often conform even when the group is wrong. When Asch interviewed the one-third of people who followed the incorrect majority view, many said they knew their answer was wrong but did not want to contradict the group for fear of being ridiculed. A few said that they really did believe the group’s answers were correct. This meant that for some, the group’s opinion had somehow unconsciously distorted their perceptions. What Asch’s experiment revealed was that even when an answer is plainly obvious, we still have a tendency to be swayed in the wrong direction by the group. This is either because we do not want to stand alone, or because the bandwagon effect can so powerfully influence our unconscious minds that we will actually bend reality to fit in.

Because Asch showed it didn’t take much to get us to conform to a highly implausible majority conclusion, the question is what happens when we are asked to conform to something discussed as real and true by powerful institutions like the media and psychiatry? The likelihood is that our rates of conformity will dramatically increase. And this is why the historian Edward Shorter believed that when it came to the spread of symptoms, the same “bandwagon effect” could be observed too. If enough people begin to talk about a symptom as though it exists, and if this symptom is given legitimacy by an accepted authority, then sure enough more and more people will begin to manifest that symptom.

This idea explained for Shorter why symptoms can dramatically come and go within a population—why anorexia can reach epidemic proportions and then suddenly die away, or why self-harm can suddenly proliferate. As our symptom pool alters, we are given new ways to embody our distress, and as these catch on, they proliferate.

After reading Shorter’s work, Dr. Lee began to understand what had happened in Hong Kong. Anorexia had escalated after Charlene’s death because the ensuing publicity and medical recognition introduced into Hong Kong’s symptom pool a hitherto foreign and unknown condition, allowing more and more women to unconsciously select the disorder as a way of expressing their distress.

This theory was also consistent with another strange change Dr. Lee had noticed. After Charlene’s death it wasn’t just the rates of anorexia that increased but the actual form anorexia took. The few cases of self-starving Lee treated before Charlene’s death weren’t characterized by the classic symptoms of anorexia customarily found in the West, where sufferers believe they are grossly overweight and experience intense hunger when they don’t eat. No, this particular set of Western symptoms did not match the experiences of anorexics that Lee encountered before the mid-1990s, where anorexics had no fear of being overweight, did not experience hunger, but were simply strongly repulsed by food.

This all changed as Western conceptions of anorexia flooded Hong Kong’s symptom pool in the mid-1990s. Young women now began to conform to the list of anorexic symptoms drawn up in the West. Like Western anorexics, those in Hong Kong now felt grossly overweight and desperately hungry. In short, as part of the Western symptom drained eastward, the very characteristics of anorexia in Hong Kong altered too.

Watters now understood that Lee’s discoveries in Hong Kong could be used to help partly explain a whole array of psychiatry contagions that could suddenly explode in any given population. The only problem was that Western researchers were loath to recognize how the alteration of symptom pools could account for these contagions. As he writes:

A recent study by several British researchers showed a remarkable parallel between the incidence of bulimia in Britain and Princess Diana’s struggle with the condition. The incidence rate rose dramatically in 1992, when the rumors were first published, and then again in 1994, when the speculation became rampant. It rose to its peak in 1995, when she publically admitted the behavior. Reports of bulimia started to decline only after the princess’s death in 1997. The authors consider several possible reasons for these changes. It is possible, they speculate, that Princess Diana’s public struggle with an eating disorder made doctors and mental-health providers more aware of the condition and therefore more likely to ask about it or recognize it in their patients. They also suggest that public awareness might have made it more likely for a young woman to admit her eating behavior. Further, the apparent decline in 1997 might not indicate a true drop in the numbers but only that fewer people weren’t admitting their condition. These are reasonable hypotheses and a likely explanation for part of the rise and fall in the numbers of bulimics. What is remarkable is that the authors of the study don’t even mention, much less consider, the obvious fourth possibility: that the revelation that Princess Diana used bulimia as a “call for help” encouraged other young women to unconsciously mimic the behavior of this beloved celebrity to call attention to their own private distress. The fact that these researchers didn’t address this possibility is emblematic of a pervasive and mistaken assumption in the mental health profession: that mental illnesses exist apart from and unaffected by professional and public beliefs and the cultural currents of the time.189

As I was nearing the end of writing this chapter, I called Ethan Watters at his home in San Francisco to ask if we should be concerned about this professional “cultural blindness,” especially at a time when Western psychiatry was being exported to more and more societies globally as a solution for their problems.

“When you look around the world to see which cultures appear to have more mental illnesses and are more reliant on psychiatric drugs,” answered Watters, “you do get the impression that we in the West are at one end of the scale in terms of being more prone to mental illness symptoms. But if that is due partly to our cultural agreement about what mental illness is, what in the world are we doing giving them all our techniques and models? Especially when other countries clearly have better recovery rates from these illnesses than we do?”

This question, for Watters, was rhetorical—he had his answer. But before we unpick what Watters knows, we first must consider one final collection of methods by which Western ideas of distress, contained in manuals like the DSM and ICD, are now infecting global populations. These methods have nothing to do with the subtle alteration of local symptom pools, but rather with the intentional exportation of Western models and treatments by the pharmaceutical industry.

4

In early 1999, the Argentinean economy went into a tailspin. Poor economic management throughout the 1990s meant that many years of mounting debt, unemployment, increasing inflation, and tax evasion culminated in a catastrophic three-year recession. By December 2001, things had become so bad in Argentina that violent riots had reached the capital, Buenos Aires. But as people were approaching breaking point, they were not only taking to the streets to express their despair, they were also turning up en masse at local hospitals, complaining of debilitating stress.

As the social suffering continued to mount in Argentina, two major pharmaceutical companies were at the same time grappling for the market share: the multinational pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly and the local pharmaceutical company Gador. What both companies knew was that mounting stress presented a great sales opportunity. As the situation deteriorated on the ground, both companies actively engaged in powerful marketing campaigns. These involved many of the marketing techniques I talked about in chapter 9, where companies learn from prescription records about which doctors their sales campaigns should target.

As both companies aggressively competed for the market share, slowly but surely a clear winner started to emerge—the local pharmaceutical company Gador. Its unlicensed copy of Prozac soon became the most widely used antidepressant in Argentina, while Eli Lilly’s Prozac, which was the same price as Gador’s version, strangely languished in sixth place. Was there something about Gador’s marketing campaign that gave it the edge?

Professor Andrew Lakoff, an anthropologist studying antidepressant usage in Buenos Aires during the 1990s, had become particularly interested in how the two companies were marketing their chemical solutions. When I interviewed Lakoff in late 2012, it became quite clear that they had had different approaches.

“There was a legendary drug rep at Gador,” said Lakoff at the other end of the phone, “who told me that he was somewhat dismissive of the marketing strategies that purely focused on crunching numbers and data mining of prescriptions because they overlooked the essential thing—the importance of relationships, those developed between company reps and prescribers. These relationships did not just enable reps to offer incentives to doctors to prescribe Gador’s products, but they also enabled reps to understand why doctors would prescribe a particular drug.”

This information was key because while in the United States and Europe psychiatry had shifted toward the technological or biological approach of considering mental illness to be located in the brain, Argentinean psychiatrists still largely understood mental illness as resulting from social and political problems. “Gador knew that selling drugs through images of ‘neurotransmission’ and ‘selective receptors,’ as Eli Lilly was doing, wasn’t the best way to get psychiatrists to adopt a given drug,” continued Lakoff. “You had to approach local doctors on their own political and epistemological footing. This meant in the case of Argentina you had to appeal to the psychiatrists’ more sociopolitical understanding of why patients suffered from mental disorders.”

Gador therefore developed a marketing campaign that focused on suffering caused by globalization. This campaign was clever because it capitalized on an argument that resonated with local psychiatrists about how the challenges of globalization were largely responsible for escalating economic and social misery. “So Gador took advantage of the understanding the psychiatrists had adopted about why their patients were suffering, and they used that understanding in their campaign.”

For instance, one advert featured a series of unhappy people traversing a map of the world, suffering from symptoms of globalization: deterioration of interpersonal relations, deterioration in daily performance, unpredictable demands and threats, personal and familial suffering, loss of social role, and loss of productivity.190 Here, Gador explicitly appealed to the notion that its pills targeted the social suffering in terms of which most people articulated their distress—a message that had far greater resonance in Argentinean psychiatry than did references to neurotransmitters and serotonin levels.

Gador therefore actively deployed this deeper cultural knowledge of the local language of distress to win local doctors over to its product. “My sense is that Eli Lilly were not present on the ground in the same way Gador was,” affirmed Lakoff. “They didn’t have the same long-term experts in the field doing the cultural work.” While Eli Lilly’s campaign was based on bio-speak that did not resonate with Argentinean psychiatrists, Gador’s message touched the heart of their sociopolitical beliefs. It was the deeper cultural knowledge Gador cultivated that helped it win the greater market share.

Let’s now fast-forward a year to another pharmaceutical campaign that Ethan Watters had been separately studying in Japan, to a time when Western pharmaceutical companies were becoming far more aware that you had no hope of capturing local markets unless your marketing campaigns chimed with local cultural meanings.

We are sitting in a plush conference room in Kyoto, Japan, in which some of the world’s leading academic experts in cross-cultural psychiatry are gathered.191 The conference has been paid for and organized by GlaxoSmithKline, which has recruited experts from countries like France, Britain, United States, and Japan to discuss the topic “Transcultural Issues in Depression and Anxiety.”

All the attending experts have been flown to Kyoto first class and have all been accommodated in an exclusive city hotel. One attendee, Professor Laurence Kirmayer from McGill University, commented to Watters upon the lavishness of it all. “These were the most deluxe circumstances I have ever experienced in my life,” said Kirmayer, wide-eyed. “The luxury was so far beyond anything I could personally afford, it was a little scary. It didn’t take me long to think that something strange was going on here. I wondered, what did I do to deserve this?”192

We find a clue when we continue to scan the conference room. We notice that dotted among the attendees is a handful of people dressed so slickly and expensively that they couldn’t possibly be, well, academics. But these are no ordinary company reps, either, offering the usual sales patter about the virtues of their drug. They are something else entirely, a whole new breed of company employee.

“Their focus was not on medications,” Kirmayer recalled to Watters. “They were not trying to sell their drugs to us. They were interested in what we knew about how cultures shape the illness experience.” Kirmayer said that what surprised him about these employees was their consummate capacity to understand and debate everything the experts discussed. “These guys all had PhDs and were versed in the literature,” said Kirmayer. “They were clearly soaking up what we had to say to each other on these topics.” These private scholars, these company anthropologists, were obviously there to learn.

In order to find out what they wanted to learn, we first need some contextual background. In Japan before the 2000s, SSRI antidepressants were not considered a viable treatment for the Japanese population. The reason seemed clear: At that time in Japan there was no recognized medical category for what is termed in the United States or Europe as mild or moderate depression—the disorders most regularly treated with SSRIs. The Japanese category that came closest to depression was utsybyo, which described a chronic illness as severe as schizophrenia, and for which sufferers needed to be hospitalized. Thus, huge swaths of the “worried well,” who were prescribed SSRIs in Europe and the United States, simply resided outside the pool of people to whom companies could sell pills.

The challenge for GlaxoSmithKline, then, was clear: How do you get these untreated people not only to think of their distress as “depression” but as something to be helped by medications like Seroxat?

This was precisely why expensive conferences like the one in Kyoto were set up. Company officials needed to acquire a deep and sophisticated understanding of how to market the “disease” and its “cure.” They needed to learn how to convert the Japanese population to a more Anglo-American way of understanding and treating their emotional discontent. This was why Kirmayer believed he and his colleagues had been treated like royalty in Kyoto—GlaxoSmithKline need to solve a cultural puzzle potentially worth billions of dollars.193

Once that knowledge had been gathered, GlaxoSmithKline launched a huge marketing campaign in Japan. The images of depression it popularized in magazines, newspapers, and on TV were intentionally vague, so that nearly anyone who was feeling low could interpret her experience as depression. These messages were also particularly targeted toward the young, the smart, the aspiring, and avoided dwelling on the pills’ dubious efficacy as well as their many known undesirable side-effects. The ads were also focused on de-stigmatizing depression, urging people not to suffer in silence and encouraging them to take charge of their own condition and request a prescription.

Alongside the ad campaigns, about 1,350 Seroxat-promoting medical representatives were visiting selected doctors an average of twice a week, priming them to prescribe the right treatment for the new malady.194 Furthermore, the drug company created websites and web communities for people who now believed they were suffering from depression, and these sites and communities gave the impression of being spontaneously growing grassroots organizations. Celebrities and clinicians appeared on these sites, endorsing and adding popular appeal to these online forums. What the patients and patient-caregivers using these websites did not know was that behind all this web information was GlaxoSmithKline, pulling the strings.

When I spoke to Ethan Watters about these company practices, he was frank. “To suggest to any knowledgeable audience that drug companies would do this surprises no one. But what is harder to believe was how studiously they were doing this, how directed and calculated it all was. These private scholars who worked in this world of drug companies learned everything you needed to know to market drugs successfully in Japan, and so what happened after wasn’t just an ancillary outcome of two cultures colliding, or the inevitable product of globalization. This was pulling levers and doing various, nefarious things to change the cultural conception in Japan of where that line was between illness and health.”

Within a few years, the efforts of GlaxoSmithKline had more than paid off. “Depression” had become a household name, and Seroxat sales had soared—from $108 million in 2001 to nearly $300 million in 2003.195 The companies had now learned that culturally sensitive marketing was key to disseminating their drugs, even if this meant altering an entire culture’s way of understanding and responding to their emotional discontent.

As Koji Nakagawa, GlaxoSmithKline’s product manager for Seroxat at the time, explained: “People didn’t know they were suffering from a disease. We felt it was important to reach out to them.” The company’s message was simple: “Depression is a disease that anyone can get. It can be cured by medicine. Early detection is important.”196

What marketing campaigns like GlaxoSmithKline’s seemed to achieve was a recasting of many people’s emotional struggles, which had once been understood and managed in terms indigenous to the population, into a medical disease requiring pharmaceutical treatments. As Kathryn Schulz put it when writing in 2004 on such promotional practice in Japan, “… for the last five years, the pharmaceutical industry and the media have communicated one consistent message: Your suffering might be a sickness. Your leaky vital energy, like your runny nose, might respond to drugs.”197 The depression contagion was not spreading because more people were getting sick, but because more and more were being taught to redefine their existing sufferings in these new disease-laden terms.

While these processes of medicalization were being purposefully manufactured in Japan and Argentina, they were also being rolled out in many other new markets, too. For one final telling example, let’s travel now to Latvia to be a fly on the wall of a psychiatrist’s consulting room sometime during early 2000.

A young woman visits her doctor complaining of “nervi”—a disorder of the “nerves” with symptoms similar to those that Western psychiatrists would classify as “depressive.” The main difference with “nervi,” however, is that in Latvia it is mostly treated by doctors attending closely to a patient’s life story and investigating the possible social and political meanings of a patient’s distress. Nervi is not therefore seen as a biomedical condition to be treated with drugs.

But as this patient continues to relay her symptoms to her doctor, something unusual happens: the doctor tells her that she may not be suffering from nervi after all, but rather from something called “depression”—a mental disorder that can be treated by a new wave of “antidepressant” pills.

At the same time as this young woman is hearing the surprising news, other victims of nervi around the country are receiving the same message: their nervi may be better understood and treated as depression. And as more and more cases of nervi are reconfigured as depression, the nation’s rates of depression unsurprisingly increase. But what had happened to instigate this change? Why were local doctors now regarding nervi differently?

When social anthropologist Vieda Skultans tried to unravel this mystery, she found that this shift coincided with two seminal events: the translation of the ICD’s classification of mental disorders (the World Health Organization’s version of the DSM) into Latvian, and the organization of conferences by pharmaceutical companies, which were aimed at educating psychiatrists and family doctors about the new diagnostic categories.198 Skultans showed that once the new language of depression was made professionally available through the ICD, the pharmaceutical industry could then disseminate the new language to patients and the wider public through educational programs.

This shift away from understanding distress in the more socio-political terms of “nervi” toward the more biological terms of “depression” not only meant that new markets opened up for pharmaceutical treatments, but that people also started to hold themselves responsible for their distress—no longer were they suffering from the strains of living in a fraught socio/political environment but from a condition located within the internal recesses of their brains.

5

What happened in Argentina, Japan, and Latvia provides just three examples of how pharmaceutical companies managed during the 2000s to capture new foreign markets throughout Asia, South America, and Eastern Europe via directly transfiguring local languages of distress. What the multinationals had learned was that you needn’t wait for local symptom pools to become Westernized through spontaneous processes of globalization; you could actually take the matter into your own hands by intentionally creating new markets, either by recasting existing local complaints and conditions in terms of Western mental health categories or by giving labels to feelings for which local populations had no existing disease categories. By funding conventions and vast marketing offensives, by co-opting huge numbers of prominent psychiatrists and manufacturing the supporting science, increased sales could be almost guaranteed. I say “almost” because there is always a risk an investment won’t deliver.

But risk is worth it, as Watters put it, “because the payoff is remarkable when the companies get it right. And it seems that with each new culture they go into, they get a little better at getting it right!”

To say that companies were behind many new and spreading mental health epidemics is not to deny the reality of psychological distress. Of course emotional suffering is universal, but we also know it is susceptible to being culturally shaped and patterned by the meanings we ascribe to it. If a company can convince enough local people that their way of understanding and treating distress needs a radical makeover, then the rewards can be staggering if locals take the bait.

Just consider the facts: IMS, a provider of health-care data, has shown that the global antidepressant market has vaulted from $19.4 billon in 2009 to $20.4 in 2011, and the global antipsychotic market from $23.2 billion in 2009 to $28.4 billion in 2011. This means that the global psycho-drug market grew from $42.6 billion in 2009 to $48.8 billion in 2011—an expansion of over $6 billion in just two years.199

Of course, increased European and US consumption can partly account for this exorbitant rise, but it certainly can’t account for it entirely. Consumption is rapidly escalating in developing, emerging, and non-Western economies. In 2010 the Japanese antidepressant market, for example, had a value of $1.72 billion, up 10.7 percent from 2009,200 while in China the annual growth figures have been around 20 percent for the last few years.201 Recent estimates of antidepressant usage in Brazil now put the figure at 3.12 percent of the entire population, a significant increase over previous years.202 If reliable data were available for other foreign markets (Mexico, Argentina, Chile, India, South Africa, Thailand, etc.) we would no doubt witness similar, escalating rates.

While the global expansion of Western psycho-drugs would hardly be possible without robust pharmaceutical and psychiatric sponsorship, there are other organizations that are giving this expansion a significant boost. In 2001, the WHO publically backed the globalization of psycho-pharmaceuticals by publishing a major report on the state of global mental health. After synthesizing years of research on psychiatric problems in developed and developing countries, the report stated that depression will be the world’s second-leading health problem after heart disease by the year 2020.

The solution proposed for this looming epidemic was to make Western psycho-drugs more widely available. Poorer countries would save millions a year treating people with pills in the community rather than in costly hospitals. Pills would also stem the negative consequences of mental health on the economy: by medicating people, they would be more likely to remain economically productive, which in turn would ensure wider economic productivity. On the other hand, the argument went, if depression weren’t treated, the economic cost could, in the final analysis, be prohibitive.203

This all sounds very logical, and perhaps even chivalrous, and of course when our Western psycho-technologies genuinely help, it would be wrong to keep them for ourselves. But even if we accept that psychotropic drugs can work in some cases, the jury is out on whether medicating vast swaths of foreign populations helps anyone other than the pharmaceutical companies themselves.

We have already heard in chapter 4 how antidepressants work no better than placebos for the majority of people, but we also know there are serious problems with the more powerful antipsychotics. In fact, one of the most damning criticisms of the 2001 WHO report comes from data gathered some years earlier, ironically enough by the very same organization.

This separate WHO study was undertaken by a team of more than a hundred psychiatrists who researched, among other things, how quickly psychiatric treatment was helping patients in developed countries.204

To explore this question, they compared the recovery rates of patients in developed countries (like the United States, Denmark, and UK) with patients being treated in developing countries (like Nigeria, Columbia, and India). The findings were troubling.

In the two-year follow-up study after treatment, only 15.5 percent of patients in the developed world had completely clinically recovered, compared to a full 37 percent of patients from the developing countries. Also, a full 42 percent of patients in the developed countries experienced impaired social functioning throughout the follow-up period, whereas only 16 percent from the developing countries experienced the same social impairment.

The most worrying statistic of all was that while patients in developing countries did far better than patients in developed countries, patients in the developed countries were taking far more medication: 61 percent of patients in the developed countries were on continuous antipsychotic medication, compared to only 16 percent in the developing countries. So who was getting better quicker? Not the patients in developed countries like the UK and the United States who were taking far more pills, but the patients in developing countries like Nigeria and India where psychiatric resources and pill-taking were comparatively meager.205 How do we explain this?

One possible reason is that we in the developed world are doing worse because we are under different kinds of social pressures. Maybe the social conditions of the contemporary West simply aren’t conducive to good mental health—and indeed the authors of the study directly pointed to cultural differences being the most important factor in our poorer outcomes.

Yet the differences they emphasized weren’t only related to differing levels of social stress (it would be churlish to argue that somehow life is far more difficult for us); rather, in non-Western cultures there appeared to be better community support for the emotionally and mentally distressed. This insight accords with numerous studies showing how crucial good relationships, community acceptance, and support are in recovery.206

We already know that when people can be assisted in a non-hospital environment, close to home, with lower doses of medication, their recovery is far better.207 We also know from studies in Finland of new “open dialogue” approaches (where treatment is focused on supporting the individual’s network of family and friends, as well as respecting the decision-making of the individual) that community-based care works far better than conventional biochemically heavy interventions. Could research like this help explain why patients in developing countries are doing far better than their more medicated Western counterparts, for whom community relations are increasingly atomized, unsupportive, and individualistic?

If so, could the exportation of individualized chemical treatments and biological understandings of distress be to the detriment of these less individualist communities? A biological vision so intimidating to most people that they feel there is nothing to be done other than hand over the sufferer to the so-called experts so they can do their work?

Western psychiatry has just too many fissures in the system to warrant its wholesale exportation, not just because psychiatric diagnostic manuals are more products of culture than science (chapter 2), or because the efficacy of our drugs is far from encouraging (chapter 4), or because behind Western psychiatry lies a variety of cultural assumptions about human nature and the role of suffering of often questionable validity and utility (chapter 9), or because pharmaceutical marketing can’t be relied on to report the facts unadulterated and unadorned (chapter 10), or finally because our exported practices may undermine successful, local ways of managing distress. If there is any conclusion to which the chapters of this book should point, it is that we must think twice before confidently imparting to unsuspecting people around the globe our particular brand of biological psychiatry, our wholly negative views of suffering, our medicalization of everyday life, and our fearfulness of any emotion that should bring us down.

Perhaps in the last analysis, we are ultimately investing vast wealth in researching and treating mental illness because, unlike in many other cultures, we have gradually lost our older belief in the healing powers of community and in systems that once gave meaning and context to our mental discontent. This is a view that commentators like Ethan Watters urge the mental health industry to start taking very seriously: “If our rising need for mental health services does indeed spring from a breakdown of meaning, our insistence that the rest of the world think like us may be all the more problematic. Offering the latest Western mental health theories, treatments, and categories in an attempt to ameliorate the psychological stress sparked by modernization and globalization is not a solution; it may be part of the problem. When we undermine local conceptions of the self, community, and modes of healing, we may be speeding along the disorienting changes that are at the very heart of much of the world’s mental distress.”208

At the end of my interview with Watters, he had one final message he wanted to impart. “I believe that the rest of the world has as much to teach us about how to live a healthy human life as we have to teach them,” he said passionately, “but we need a good deal more humility in order to understand that.” Without that humility, the flow of ideas will continue in a one-sided direction. And even if that does not mean that the rest of the world will end up thinking just like us, it does mean that the rest of the world’s way of understanding, managing, and experiencing emotional suffering will imperceptibly change.

As to how it will change will differ from place to place, but whatever changes ensue, the best we can hope for is that these changes are undertaken with full awareness of the serious problems afflicting psychiatry in the West. Others realizing that our so-called solutions have created vast new problems in the places where they were devised may be the only bulwark against the ill-advised dash to import a system that may bring as many problems as it purports to solve.