CHAPTER FOUR

THE DEPRESSING TRUTH ABOUT HAPPY PILLS

When I started out working as a psychotherapist in the NHS in the UK, I knew nothing about the construction of mental disorders, about false psychiatric epidemics, about the out-of-control medicalization of normality, about the disconcerting confessions of DSM chairmen, and certainly nothing about the alarming facts that I’m about to reveal to you now.

Like most people inside and outside the medical community, I used to think that antidepressants worked. I pretty much accepted, like everyone else, that these pills modified chemical levels in the brain in order to create improved states of mind. This was why most of the patients referred to me for long-term psychotherapy were taking antidepressant medication. The pills helped stabilize their moods to the point that they could engage more successfully in therapeutic work. That is what I was taught. That was the party line. But it wasn’t long before I discovered the party line is wrong.

But how could this be? The pharmaceutical industry makes over $20 billion each year from antidepressant medications. Doctors up and down the country are convinced of their effectiveness. The media regularly and glowingly reports how these pills help millions each year. And countless patients claim that their lives would have been ruined without them. Surely it would therefore be simply conspiratorial to suggest that all this money and all this enthusiasm is the product of a misleading myth.

That is precisely what I am about to suggest, as solid scientific research now shows clearly that antidepressants don’t actually work, or at least not in the way people think.

2

In early May 2011, I wrote to Professor Irving Kirsch, an associate director at Harvard Medical School and today perhaps the most talked about figure internationally in antidepressant research. Our exchange went something like this:38

Dear Professor Kirsch,

I am writing a book on psychiatry and I’d appreciate the opportunity to interview you about your important work on antidepressants. I’ll be in Boston in early May. If it’s convenient, I would love to come over to Harvard and interview you there. Just say the word.

Dear Dr. Davies,

I’d be delighted to chat with you, but I’m not in Boston in early May. I am now in Florence, but I’ll be at my home in the UK in April. Perhaps we can meet there?

Dear Professor Kirsch,

In the UK? Perfect. Where shall I meet you?

Dear Dr. Davies,

At my home in Scorborough, Yorkshire … you know that part of the world?

Dear Professor Kirsch,

Sure, I know it well …

… But what, I was then tempted to ask, is a Harvard professor doing living on the Yorkshire moors?

One Friday morning in April, I would find out. I set off from my home in Shepherds Bush, West London, and drove 250 miles up the M1 to rural Scorborough. Kirsch, it turns out, had been a professor at the University of Hull before moving to Harvard Medical School. When working at Hull, Kirsch and his wife had become so attached to the surrounding area that they had decided to keep paying the rent on their lovely Georgian villa, which was sequestered in an urbane and picturesque little hamlet just outside the city.

As my exhausted little car rattled up onto the driveway, Kirsch was standing by the door. He waved and smiled kindly, greeting me like a friend he hadn’t seen for years. After entering the house, he kept turning around eagerly to ask me questions as he led me down a long corridor and into his main drawing room.

It was grand and congenial, like an Oxbridge senior common room, festooned with authentic Georgian furnishings and illuminated with the light from a flickering chandelier and a sweeping bay window. We settled onto two plump easy chairs in front of the old fireplace whose chimney breast, which made me smile as I noticed, was stuffed with newspaper to ward off the bitter Yorkshire wind.

As I surveyed the man and the scene, it was clear to me that Kirsch had traveled great distances in his life—socially, artistically, geographically, and intellectually. He was a real, live product of the American Dream. He was born to Polish immigrants in New York City in 1943. He’d been heavily involved in the civil rights movements of the 1960s, while also writing pamphlets against the Vietnam War (at the request of Bertrand Russell). Before becoming a psychologist in his early thirties, he’d worked as a violinist, accompanying artists like Aretha Franklin and enjoying a stint in the Toledo Symphony Orchestra. Just before gaining his PhD in psychology in 1975, he was nominated for a Grammy award for an album he’d produced, which included doctored snippets from the Watergate hearings.39 His journey is, therefore, an interesting one: his life has oscillated between music, psychology, pacifism, and politics—between New York, California, Krakow, Boston, and now Scorborough.

It seemed ironic to start our interview by asking Kirsch, a devoted pacifist in his youth, about a war he had recently started within the medical community ignited by his scientific research. The war was so turbulent because so much was at stake, not only for the millions of adults and children who now take antidepressants, or for the hundreds of thousands of doctors around the globe who are now prescribing them, but also for the pharmaceutical industry that makes billions a year from antidepressant sales. What I wanted to know from Kirsch was how someone so seemingly peaceful could have created such widespread pandemonium.

“By complete accident,” answered Kirsch with a boyish smile as he sipped tea from an antique china cup. “I wasn’t really interested in antidepressants when I started out as a psychologist. I was more taken by the power of belief—how our expectations can shape who we are, how we feel, and, more specifically, whether or not we recover from illness. Like everyone else at the time,” continued Kirsch, “I just assumed antidepressants worked because of their chemical ingredients. That’s why I’d occasionally referred depressed patients to psychiatrists for antidepressant medication.”

Everything would change for Kirsch after a young man called Guy Sapirstein approached him in the mid-1990s. This bright and eager graduate student had become fascinated in the placebo effects of antidepressants. What gripped Sapirstein was how depressed patients could actually feel better by taking a sugar pill if they believed it to be an antidepressant. This led Sapirstein to wonder about the extent to which antidepressants worked through the placebo effect, by creating in patients an expectation of healing so strong that their symptoms actually disappeared.

Once Sapirstein had outlined his interests, Kirsch knew he wanted to get on board. And so it wasn’t long before both men set about investigating the question together: To what extent did antidepressants work because of their placebo effects?

“Instead of doing a brand-new study ,”said Kirsch, describing the method they employed, “we decided to do what is called a meta-analysis. This worked by gathering all the studies we could find that had compared the effects of antidepressants to the effects of placebos on depressed patients. We then pooled all the results to get an overall figure.”

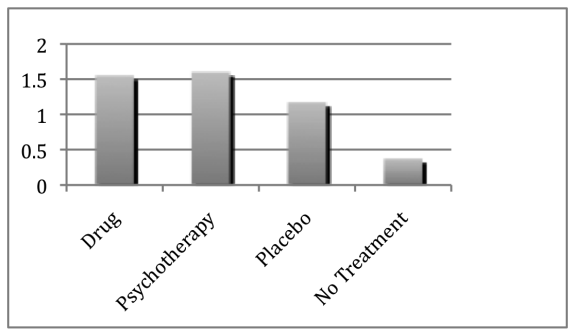

In total, Kirsch’s meta-analysis covered thirty-eight clinical trials, the results of which, when taken en masse, led to a startling conclusion. “What we expected to find,” said Kirsch, lowering his teacup, “was that people who took the antidepressant would do far better than those taking the placebo, the sugar pill. We couldn’t have been more wrong.” And if you look at the graph below you’ll see exactly what Kirsch means:40

The first thing you’ll notice is that all the groups actually get better on the scale of improvement, even those who had received no treatment at all. This is because many incidences of depression spontaneously reduce by themselves after time without being actively treated. You’ll also see that both psychotherapy and drug groups get significantly better. But, oddly, so does the placebo group. More bizarre still, the difference in improvement between placebo and antidepressant groups is only about 0.4 points, which was a strikingly small amount.

“This result genuinely surprised us,” said Kirsch, leaning forward intently, “because the difference between placebos and antidepressants was far smaller than anything we had read about or anticipated.” In fact, Kirsch and Sapirstein were so taken aback by these findings that they initially doubted the integrity of their research. “We felt we must have done something wrong in either collecting or analyzing the data,” confessed Kirsch, “but what? We just couldn’t figure it out.”

So in the following months Kirsch and Sapirstein analyzed and reanalyzed their data. They cut the figures this way and that, counted the statistics differently, checked what pills were assessed in each trial, and reexamined their findings with colleagues. But each time, the same results came out. Either they could not spot the mistake, or there simply was no mistake to spot. Eventually there seemed to be no other alternative than to take the risk and publish their findings that antidepressants, according to their data, appeared to be only moderately more effective than sugar pills.

“Once our paper appeared,” Kirsch recalled, smiling, “there was … well, how can I put it … controversy. The most significant critique was that we had left out many important trials from our meta-analysis. Perhaps an analysis that included those studies would lead to a different conclusion.”

Indeed, Thomas Moore, a professor at George Washington University, pointed this out to Kirsch by revealing that his meta-analysis had only assessed the published trials on whether antidepressants work. Their study had therefore failed to include the drug trials left unpublished by the pharmaceutical companies who conducted them. Kirsch and Sapirstein had been unaware that pharmaceutical companies regularly withhold trials from publication. When Kirsch looked into how many trials this amounted to, he was aghast at what he found: nearly 40 percent of all the trials on antidepressant drugs had not been published—a staggering amount by all accounts.

I asked Kirsch what he did next. “Moore suggested we appeal through the Freedom of Information Act to get the unpublished company studies released,” answered Kirsch. “Once we were successful at that, we undertook a second meta-analysis which now included all the studies—both published and unpublished.”

As the results came in from this second meta-analysis, Kirsch grew even more alarmed. They showed that the results of his first study were plainly wrong: antidepressants did not work moderately better than placebos; they worked almost no better at all.

3

Moving away for a moment from the cozy sitting room in which Kirsch was recounting his unsettling series of discoveries, let’s backtrack a little so I can illustrate to you how the studies into antidepressants that Kirsch’s meta-analysis surveyed were conducted.

To do this, imagine yourself in the following scenario: You’ve been depressed for at least two weeks (the minimum time needed to be classed as depressed, as you’ll recall from Chapter 1). So you eventually decide to drag yourself to your doctor, who asks you if you would like to participate in a clinical trial. The aim of this trial is to test the effectiveness of a new antidepressant drug (which may cause some side effects if you take it).

Your doctor then explains how the trial will work: before you are given the antidepressant, your level of depression will be measured on something called the Hamilton Scale. This is a scale that runs from 0 to 51, and the task is to work out where you sit on this scale.

Your doctor explains that all the trial researcher will do to work out where you sit is ask you a number of questions about yourself, such as whether you are sleeping well, whether you have an appetite, whether you are suffering from negative thoughts, and so on. You’ll then be given points for each of the answers you give. For example, if you answer that you are sleeping well, you’ll be given one point, whereas if you say you are hardly sleeping at all, you’ll be given four points. The more points you accumulate, the higher you are rated on the scale, and the higher you are rated on the scale, the more likely you are to be classed as depressed. That’s how the Hamilton Scale works: If you’re rated at 26, you’re thought to be more depressed than if rated at 19. You’ve got the idea.

After this initial assessment, the trial researcher will then place you in one of two groups of patients and prescribe a course of pills. But there’s a catch. You’ll be told that only one group of patients will be prescribed the real antidepressant, while the other group will be given a “placebo pill”—a pill that is made of sugar and which therefore contains no active chemical properties. No one will be told which group they are in, nor will anyone know what pill they are taking until their treatment has ended some three months later and their levels of depression have once again been measured on the Hamilton Scale. Your first rating (pre-treatment) and second rating (post-treatment) will then be compared.

Now, if your rating has gone down after treatment, it means you have improved (and thus the pill has worked). But if it has increased, it means you have worsened (and thus the pill hasn’t worked). Once the researchers gather the ratings for all patients in the trial, they can then compare the two groups to assess how superior the antidepressant is to the sugar pill in alleviating depression.

Now imagine that the clinical trial you have just participated in contained about five hundred other patients, all going through the same process as you. This of course is a significant amount, but it’s still only one trial. What Kirsch did, you’ll remember, is pool the results of all the trials he surveyed—both published and unpublished. So in effect Kirsch’s second meta-analysis collated the results of many thousands of patients, all of whom had been studied in trials like the one I have just described. And it was on the basis of this second analysis, as I mentioned a moment ago, that Kirsch reached the alarming conclusion that antidepressants work hardly better than placebos. Here is what his results looked like.

As in his first meta-analysis, which only looked at the published trials, Kirsch’s second meta-analysis, which assessed both published and unpublished trials, revealed that both placebo and antidepressant groups got better. But his second meta-analysis also revealed that the difference in rates of improvement between the antidepressant group and the placebo group was insignificant.

And that’s the important bit. “After surveying all the trials, we discovered that the antidepressant group only improved by 1.8 points on the Hamilton Scale over the placebo group,” stated Kirsch. “Now, this may not mean much to you. But what if I were to tell you that your score can be reduced by a full 6.0 points if you are merely sleeping better? Well, you’d rightly conclude that 1.8 is a tiny difference. And that’s precisely why the NICE [National Institute for Clinical Excellence] has said there must be a difference of at least 3.0 points for the difference to be deemed clinically significant. Yet the difference we found was only 1.8 points—totally clinically insignificant.”

Indeed, a 1.8 difference on the Hamilton Scale is barely noticeable in terms of a person’s actual experience. But what was also interesting for Kirsch was that even the tiny 1.8 difference between the antidepressant and placebo groups still didn’t mean anti-depressants worked better than placebos. “Just remember how the clinical trials work,” Kirsch explained to me. “You are told by your doctor you’ll be given one of two pills. You are also told that the antidepressant pill will produce side effects in most patients [like drowsiness, diarrhea, nausea, forgetfulness, dry mouth, and so on]. So what happens if, after taking the pill, you start to experience some of these side effects? Well, like most people you’ll figure out that you’re on the real drug. And believing you are on the real drug, you’ll now expect to get better. And it’s this increased expectation of recovery that actually helps you improve.”

What Kirsch had worked out was that strong side effects convince patients that they are on the real drugs—and being so convinced, the placebo effect becomes all the greater. In other words, side effects increase the placebo effect. And this is how Kirsch could then account for the tiny 1.8 improvement in the antidepressant over the placebo group.

So, in summary, Kirsch’s second meta-analysis (which included both published and unpublished trials) was far more dramatic than the first. It concluded that the new wave of antidepressants heralded as wonder drugs—Prozac, Seroxat (Paxil in the United States), Lustral (Zoloft), Dutonin (Sezone), Cipramil (Celxa), and Effexor—worked no better than dummy pills for the vast majority of patients. Of course, there were about 10 percent to 15 percent of people, the very extremely depressed, for whom these pills worked in a very minor way (about four points better than placebos on the Hamilton Scale), but this meant, as Kirsch pointed out, that about “85 percent to 90 percent of people being prescribed antidepressants are not getting any clinically meaningful benefit from the drug itself.”

4

Once Kirsch published his second analysis showing that antidepressants worked no better than sugar pills for the vast majority of patients, it immediately became front page news in the most respected papers in the UK: The Guardian, The Times, The Independent, and the Daily Telegraph. It made its way into newspapers and television and radio news programs in the United States, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Italy, Britain, South Africa, Australia, Canada, China, and many other countries. It was reported and debated in countless leading medical and scientific journals, including the prestigious scientific journal Science. Basically, overnight it transformed Kirsch into a global media fascination.41

All this attention also made many in the medical community sit up and take note of his research. Just three months after Kirsch’s work was published, for instance, a survey was conducted on nearly five hundred British doctors asking them whether Kirsch’s findings would affect how they’d prescribe antidepressants in the future. Almost half of the doctors, 44 percent, said they would change their prescribing habits and consider alternative treatments. But this, of course, still meant that over 50 percent intended to go on prescribing as usual. Most of these 50 percent justified their position by arguing that in their clinical experience antidepressants do work, no matter what Kirsch’s research indicates.

I asked Kirsch what he made of this. “Well, the truth is, these doctors are correct,” he responded. “Our research also shows that antidepressants work, but again not for the reasons most people suppose. They work because of their placebo effects, not because of the chemical in the drug—and that’s the point we were making.”

There were other criticisms of Kirsch’s work. “One we heard again and again,” said Kirsch, “was that the studies we surveyed must have been flawed. Some said these studies were too short to show the real effects of antidepressants. Others said that the patients studied were not depressed enough, while others said the patients were too depressed. But all these objections, taken as a whole, are very curious indeed, because the studies we surveyed were also those assessed by the regulatory agencies in the UK and US to justify approving these drugs for public use.42 So if there were something wrong with the studies, why had the regulatory agencies in Europe and the US used them as a basis for approving these drugs?”

A further criticism, perhaps even more quixotic, was that even if the drugs don’t work, it was still wrong of Kirsch and his colleagues to have published their results. Patients should be protected from findings that could undermine their faith in treatment. Kirsch disagreed adamantly, saying: “Without accurate knowledge, patients and physicians cannot make informed treatment decisions, researchers will be asking the wrong questions, and policymakers will be implementing misinformed policies. If the antidepressant effect is largely a placebo effect,” continued Kirsch, “it is important that we know this so that improvement can be obtained without reliance on addictive drugs which have potentially serious side effects.”43

A final suite of criticisms was aimed at the methods Kirsch used. ‘There were a number of papers criticizing our statistical methods and redoing them,” said Kirsch, “some in appropriate ways, some in inappropriate ways, and some just making careless mistakes. But no matter how these analyses were done, nobody ever passed the 3.0 point threshold for clinical significance, which only gave additional support to our own conclusions.”

So Kirsch’s research withstood the criticisms. But were there any other studies that actually replicated his findings? I put this question to Walter Brown, professor of psychiatry at Brown University, who has co-authored two studies analyzing the same set of clinical trials that Kirsch surveyed. His answer was unequivocal: “We pretty much found the same thing as Kirsch. For a small minority of patients (the most severely depressed), our studies showed that antidepressants may have some minor benefits. But for mildly\moderately depressed patients,” said Brown earnestly, “our results confirm that antidepressants offer no advantage over placebos, alternative therapies, or even moderate exercise.”44

In other words, Brown’s research confirmed that the vast majority of people taking antidepressants do not receive any chemical benefit. “There is no question that these drugs are overhyped to the general public,” reiterated Brown. “The research shows they are not as good as the psychiatric establishment and the pharmaceutical industry claim they are.”

While Irving Kirsch and Walter Brown reached the same conclusions independently, so too did a major study of antidepressants that the NHS commissioned in the UK. This NHS study also declared that the difference between placebos and antidepressants is so modest, that for mild to moderate depression antidepressants were not worth having at all.

“Our results were again like Irving Kirsch’s,” said Dr. Tim Kendall, lead author of the study published in the Lancet. “Our widespread comparative meta-analysis of antidepressants showed pretty clearly that the difference between the published and unpublished studies of antidepressants in children was that for the published trials all the drugs worked, while for the unpublished trials none of the drugs worked. And if you looked at the published and unpublished combined, you’d only probably recommend the use of only one drug for childhood depression.”

At the same time as conducting that research, Kendall was also responsible for helping draw up the treatment guidelines for depression throughout the NHS. “Once we had those figures,” said Kendall, “we asked the depression guideline group what they would conclude if they only saw the published trials, and what would they conclude if they saw the whole data set (the published and the unpublished). We found that seeing the whole data set changed their view completely. And that is the key bit: drug companies not publishing negative trials actually changes clinicians’ minds.”

Given the results of studies as outlined above, why do the regulatory agencies that evaluate antidepressants continue to approve these drugs for public use? The key to answering this question is to realize that the regulatory agencies do not take into account the results of negative trials when deciding to approve an antidepressant or not. For example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in the United States, and the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulation Agency (MHRA), in Britain, merely require that a company show in just two clinical trials that their drug is more effective than a placebo. This is the case even if there are five, ten, or fifteen clinical trials showing negative results. In other words, regulatory agencies discard the negative trials. And they do this no matter how many there are. All they require are two positive trials to give the green light for public use.45

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States has publically defended what may seem to you and me a dubious approval process. In 2012, for instance, Lesley Stahl of CBS News interviewed the director of the unit responsible for approving antidepressants, Dr. Tom Laughren. Stahl asked Laughren why the FDA requires merely two positive clinical trials to approve a drug, even though many negative trials may exist. Laughren’s response was faltering and confusing.

Laughren: “We consider everything that we have, we look at those trials individually …”

Stahl: “But how are you knowing that the two positives deserve bigger strength in the decision?”

Laughren: “Getting that finding of a positive study by chance, if there isn’t really an effect, is very low. That’s basic statistics, and that’s the way clinical trials are interpreted [by the FDA]. A separate question is whether or not the effect you are seeing is clinically relevant.”

Stahl: “Okay—is it clinically relevant?”

Laughren: “The data we have shows that the drugs are effective.”

Stahl: “But what about the degree of effectiveness?”

Laughren: “I think we all agree that the changes that you see in the short-term trials, the difference in improvement between drug and placebo is rather small.”

Stahl: “So it’s a moderate difference?”

Laughren: “It is a … well, it’s a small—it’s a modest difference.”

When I spoke to Dr Tim Kendall about Laughren’s admission, Kendall confessed that he’d actually seen this interview and that it had completely baffled him. “What I do remember, when listening to Laughren, was that it actually sounded to me a little like mumbo jumbo,” Kendall said frankly. “I couldn’t make any sense of it at all. From our point of view, whenever you’re doing a trial or a meta-analysis, it is all about probabilities—about the probability that one thing works better than another, and that probability depends upon the evidence. Now, if someone conceals some of that evidence, it simply skews the result. So the idea that regulatory bodies like the FDA will continue approving drugs on the basis of only two positive trials, and are not bothered by all the other negatives, strikes me as wholly indefensible.”

Regulatory agencies seem to think otherwise, and the consequence of this has been dramatic: it has allowed an inordinate yearly rise in antidepressant prescriptions. Just consider the facts:

Antidepressant usage has more than tripled in the United States since 1986, reaching a staggering 235 million prescriptions in 2010.46 And in Europe the situation is the same—the figures have tripled in recent years. In 2010 approximately 10 percent of all middle-aged Europeans were taking antidepressants,47 while in 2011 a baffling 47 million prescriptions of antidepressants where dispensed in Britain alone.48

In other words, despite the damning research about antidepressant efficacy, and despite the NICE recommendations that we pull back on antidepressant use, continued regulatory approval has allowed prescriptions to just keep going up and up. Of course, this raises uncomfortable questions regarding the precise relationship between the regulatory agencies and the pharmaceutical industry. Do regulatory agencies have an incentive to set the bar so low? While I won’t answer that question right now, you can be sure I’ll get to it eventually.

5

I was nearing the end of my interview with Irving Kirsch when the window beside us suddenly rattled loudly from a powerful gust of Yorkshire wind. The rain had been falling for a while, forming thick, sinuous rivulets down the windowpanes. I had only just noticed. For over an hour I’d been totally engrossed in Kirsch’s story, and neither of us had cared about the deluge outside.

As I turned my eyes back to Irving Kirsch, I now noticed he looked a little tired. It was time to wrap this one up; but first I had just one final question to ask: “How are things going to turn out? I mean, if serious research now shows that antidepressants work little better than sugar pills for most patients, while prescription rates still keep soaring, what’s going to alter things? Where do we go from here?”

“To be frank, James, I just don’t know,” said Kirsch uneasily. “Back in the old days I used to think I was good at predicting the future, but I’ve lost my confidence now. I would like to think change is slow, even for the scientific community. But my hope is that change eventually occurs.”

Kirsch looked a little pensive suddenly as he gazed out the window. “Perhaps in the future, twenty years from now, antidepressants will be seen as bloodletting is seen today. That would be really something,” said Kirsch, turning back to me. “But to get to that point, well, it will take time … Yes, it will take lots of time …”

I left Kirsch’s house understanding why the war he had triggered in the medical community was still raging so aggressively. There were forces at play that made it impossible for his findings alone to change the current state of affairs. Perhaps science was not in control after all. Perhaps something else, more powerful and less easy to identify, was holding up serious reform. But what could this be?

On my long drive back to London, I told myself that no matter how much more digging it would take, or how many more interviews, I would not stop until I found out.