Energy Buckets, and Why the Compressed Workweek is Dumb

THIS IS MY FAVORITE CHAPTER, because it has graphs – Wait! Don’t close the book yet! These graphs are fun and easy to decipher and make it easier to describe the difference between humans and robots. But before getting into the excitement, why does it even matter? Well, in the previous two chapters I’ve described why flexibility is important for the individual, for society, and for the planet, so there are good reasons for the humanist, the altruist, the feminist, and the environmentalist to take flexibility seriously.

But the capitalists, the people in charge of this flexibility – the managers, CEOs, heads of state – the ones with the power over the structures of work – might be tempted to say, “Why should I be the one to sacrifice profits/surpluses/shareholder returns just to help society? There are millions of other businesses around the world, we’re just doing the same as them: trying to make some money and create jobs. We already are helping society by giving people bloody work!”

So, this part contains the most important message of the book:

Flexibility is good for business.

Flexibility helps to decrease waste and increase profits in many ways. Rather than being a cost and a sacrifice, it’s an investment.

I want leaders to understand the value of flexibility so that it’s rolled out to people en masse rather than to individuals who have to sacrifice their reputations by asking or pushing for flexibility for themselves. It’s only when everyone has access to flexibility that we have a purposeful, strategic program, Levels 3 and 4 on the Flex Scale, rather than the bare minimum of Levels 1 or 2. Flex for all, as opposed to intermittent flexibility for just parents or caregivers, has a greater impact on individuals and society by increasing the number of people who benefit. And it requires systems in place that will ensure that the practice is optimized and allowed to succeed.

Faced with the evidence that flexibility benefits business, the polite skeptics will consider these cases as outliers; that, somehow, they got lucky, and the approach wouldn’t apply to their own business or industry. “My employees are so busy that flexibility wouldn’t work.”

This part of the book is a deep dive into how flexibility, perhaps non-intuitively, boosts productivity, makes people feel like they’re doing less when they’re doing more, reduces stress, and increases collaboration and innovation.

My goal is to change people’s perception about flexibility from “it’s a cost we bear to help mothers and to avoid litigation” to “it’s great for people and it’s great for business.” And the biggest perception that needs to change is that we consider humans to be robots.

What Is Productivity?

Another wee point to clarify before we get to the graphs (I know, the suspense is unbearable!) is that we need to agree on what productivity is.

When most people in the workplace talk about productivity, they’re talking about input: how many things are being done, how hard someone is working, busyness. Or they’re talking about output: how many things are being produced, how many sales are being made, how many coffees are being poured.

But we’re going to be more rigorous and show that there’s a vast distinction between productivity and input and output, and that there’s a big difference between robot productivity and human productivity.

To start with, the economic definition of productivity is the ratio of outputs to inputs: how many things are produced (output) per unit of resources or time to produce those things (inputs). For example, one hundred widgets made per hour, or ten tons of steel produced per one hundred tons of iron ore. Here’s what the equation looks like:

This is a reasonable definition for a machine, and we’ll use it later when we talk about a robot, but it’s only part of the story for humans. The human story is much more nuanced.

A human can sit in a chair, not making or producing anything material, yet still be highly productive. Or a human can be the busiest person in the building, rushing here and there, doing a thousand things, yet be completely unproductive.

Imagine that a telemarketer, Jack, is making twenty calls to potential customers per hour. He’s efficiently running through the pitch provided by the company, quickly being rejected, and then moving with high speed onto the next call. In a game of pure numbers, Jack has a high input.

With his current way of doing things, one out of those twenty calls is resulting in a sale. He’s content with this record because he’s just doing as he was told and assumes that this is a reasonable rate of sales. But his productivity, sales per hour, as you can guess, is probably not as high as it should be.

Next to this person is another marketer, Jan, who’s making only ten calls per hour. Her input is low compared to Jack’s; she’s not working anywhere near as fast as he is. She’s also using the script provided, but she’s putting more effort into being personable to the clients, and she’s going off script when she sees an opportunity to ask more questions about the client’s needs and how the product will suit. She’s even making permanent changes to her processes based on what seems to be capturing the favor of clients. She’s even doing research into finding the best clients in the first place.

With this method, Jan is making five sales per hour – four more (400 percent more) than Jack. She’s adding 400 percent more value to the business than Jack. Even with her much lower input, she’s being 400 percent more productive than Jack.

This is a simplistic example, but you can see that input – busyness and working hard – and productivity are quite different. A human, who can think and plan, can be much more productive than a robot that just performs a mechanical task.

The more nuanced part of human productivity is that the impact of Jan’s work goes beyond her own high level of sales. Her methods, and her desire to continuously improve, will spread to other people in the organization, thus increasing sales and reducing waste. This is why it’s so important to see productivity as more than just the number of tasks completed or widgets produced, or even the financial value of one person’s work.

True productivity comes from working with intent and being aware of the value one is providing to the business’s big picture. True productivity comes from the ability and desire to think, learn, and change.

Another term for human productivity is work goodness.

People aren’t just doing, they’re also thinking, and caring. Doing means getting stuff done, thinking means planning, strategizing, and improving, and caring is the desire to do a good job, otherwise known as engagement.

Work goodness is multifaceted. It includes the quality of the work (is it right the first time, or will it need to be redone?), seeking ways to improve work, questioning the relevance of tasks, searching for ways to reduce wasted effort, materials, and time (eliminating work can be the most productive activity we do!), innovating and creating for the business as a whole, and wanting to be there, which influences all of the above.

Robots and Humans

Robot Productivity

Now that we have a good working definition of productivity, let me introduce a robot. Robots come in a million types, shapes, and ability levels, and they’re becoming more advanced every day. But here we’re not going to talk about the T-1000 from Terminator, or Bender from Futurama, or WALL-E from WALL-E, or any other cool robot which (who?) can think, plan, and strategize.

I’m going to keep it simple and talk about a robot that lives in a manufacturing plant and performs one task. Our robot puts lids on row after row of glass bottles.

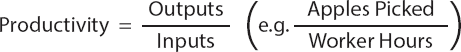

At 100 percent productivity, its design specification, it caps one thousand bottles per hour. To simplify the comparison between human and robot, we’ll assume this robot operates only on weekdays and only from nine to five.

As you can see in Figures 5.1 and 5.2, and as you’d probably expect, the productivity of the robot doesn’t change over the course of each day or from day to day during the week. It caps one thousand bottles per hour on Monday morning; it caps one thousand bottles per hour on Friday afternoon. This robot has linear productivity.*

Figure 5.1. In this graph of productivity versus time of day for a robot, the robot is turned on at nine and is instantly at or near maximum productivity (A). It remains at or near 100 percent productivity for the entire day, with only slight variations when it’s slowed down for quality purposes or for other reasons. It’s turned off at five (B), at which point its productivity drops instantly to zero. (It’s assumed that the robot doesn’t need to be shut down for maintenance or cleaning during the day and that it runs over lunchtime.)

Figure 5.2. In this graph of productivity versus day and time of week for a robot, the robot is turned on at nine and turned off at five each day, and it remains at or near 100 percent productivity for the entire day and week. It’s operational only from Monday to Friday. (The time between each day is scaled down to reduce blank space.)

Human Productivity (Assumed)

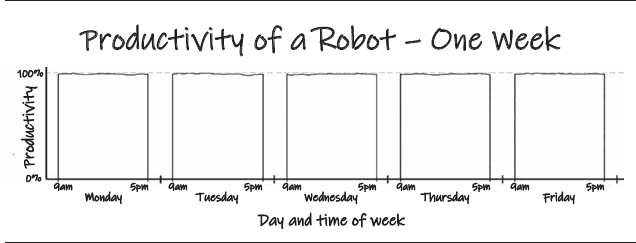

Now for humans. The way we manage humans in the traditional workplace assumes that a human’s productivity over time looks something like Figures 5.3 and 5.4, which, as you can see, is pretty close to that of a robot.

The human in this instance, like the robot, only works from nine to five; but they also have a lunch break for an hour. During the times and the days the human is supposed to be working, we assume they have linear productivity and that their productivity remains at or near 100 percent for the entire workday and workweek.

It’s important to remember that 100 percent productivity for a human isn’t just doing – going through the motions of work – but also thinking and caring: they’re giving their best.

Saying this out loud (and putting it in graph form) probably seems insane. Any reasonable person wouldn’t assume an employee is still at their highest level of productivity at four on a Friday. Or that someone can work at this level for an entire day. Yet the way we structure our traditional workplace and manage others is proof of this assumption.

We insist that people work eight or more hours a day, five or six days a week, because we’re worried that we’ll miss out on the productive time of that person if they don’t work the maximum legal amount of time. (Businesses and unions battle over how much time people have to work, with neither looking at the true issues.)

We make people ask permission and sign forms to take a day off or leave early to attend to a personal matter, worried that this downtime will affect productivity and hurt the business.

We pay people the same amount per hour regardless of whether that hour was supremely productive or completely unproductive. Often, we don’t know the difference.

We use types of flexibility such as time-in-lieu, where extra time worked one day can be taken off on another day, assuming that each hour of work is worth the same as, and is directly interchangeable with, another, like currency.

Any strict adherence to time, or use of time worked as a measure of productivity, or attempts to increase the amount of time people work, shows that we equate time worked with productivity.

This way of thinking makes perfect sense for a robot. One minute of machine downtime is indeed a lost minute of productivity, which will either be made up or lost forever. Downtime is a critical measure in a manufacturing plant because you’re not producing but you’re still paying overhead and operating costs.

But thinking that humans have linear productivity, and a minute of work lost is a minute of productivity lost, is one of the strangest lies we tell ourselves. The entire foundation of the normal workplace, and many arguments against flexibility, is based on this lie. “If they work fewer hours, they’ll get less done.” We take this as a fundamental, unbreakable, obvious law of productivity. Any idiot knows it.

Figure 5.3. In this graph of assumed productivity of a human versus time of day over one day, the human starts work at nine (A), then works at or near 100 percent productivity until lunch (B), at which point productivity is 0 percent, but it jumps straight back to or near 100 percent as soon as lunch is over, remaining there until the end of the day (C). This person may still take short morning and/or afternoon breaks, but productivity will instantly ramp back up to 100 percent as soon as that break is finished. (Breaks are not shown.)

Figure 5.4. In this graph of assumed productivity versus day and time of week for a human, the human starts work at nine each day and finishes at five. They have a lunch break from twelve to one. They work from Monday to Friday. It’s assumed that when the human is supposed to be working, their productivity is at or near 100 percent.

For example, Ian Brinkley, a chief economist in the United Kingdom, when talking about a national reduction of the working week to four days, said, “A four-day week is a 20 percent reduction in working hours. You’re going to have to get a big improvement in productivity to cover that. It’s unlikely that any productivity-enhancing effects from reducing hours would be big enough to cover the cost of reducing working hours.”1

But this assumption that humans have linear productivity fails the second we look at what a day of work actually looks like, especially in our rigid workplaces.

For instance, when a coworker interrupts us while we’re working, it takes, on average, twenty-three minutes and fifteen seconds to get back into the flow of what we were doing before the interruption.2

The assumption crashes when data says that only about two or three hours per day are truly productive in a normal workplace. A survey in the United Kingdom of 1,989 full-time office workers found that 79 percent didn’t consider themselves to be productive throughout the entire day. In fact, the average amount of time they did consider themselves to be productive was two hours and fifty-three minutes per day.3

The assumption dies when we look around an office at three and realize that 30 percent of the people are scrolling through Facebook, 30 percent are texting their partner that their brain is so dead and asking them what they feel like eating for dinner, and the remaining 40 percent are pretending to work because their boss is walking past.

Then there are just some days we’re on, some days we’re off, and some days we shouldn’t be at work. There are differences in biological chronotypes: some people work better in the morning, some in the afternoon, some at night.4 And there are a million other factors in our lives that influence human productivity and guarantee that it’s not linear, and that it’s certainly not at 100 percent for the entire workday and week.

For humans, no day is the same; no hour is the same; no minute is the same.

When the assumption of linear productivity falls, so do all arguments about arriving and leaving at a particular time, making up for lost time, signing forms to take a day off, and monitoring employees’ activities.

I don’t mean to be patronizing, and I know that no manager actually thinks of their workers as machines with constant 100 percent productivity (or I would hope that’s the case), but as a society, because of the traditions we all grew up with, this is the assumption we make. And it keeps us stuck in our traditions.

This assumption needs to be burned up and have its ashes thrown off a cliff.

Figure 5.5. In this graph of realistic productivity versus time of day for a human in a rigid workplace, the human starts work at nine each day and finishes at five. They have a lunch break from twelve to one.

Human Productivity (Realistic)

What does productivity look like for a real person in a normal, rigid workplace?

Let’s go back to the graphs.

Normally, most of us start the day with a long or stressful (or both) commute. We get to our workplace and work is the last thing on our minds. Our cortisol levels are high, and we need to de-stress by preparing for the day: chatting with coworkers, making coffee, turning on the computer, checking the news, maybe waiting for the morning team meeting. This is point A in Figure 5.5.

Having prepared for the day and settled in, our nerves calmed by the sweet, sweet caffeine, we open whatever it is we’re working on and, well, start working (point B).

But it isn’t our best work. We’re not operating at or near maximum productivity. For one thing, we know we’re in for a long day, and we’re probably partway through a long week, so we’re conserving our energy. Two, there’s no incentive to be hugely productive, since we can’t go home early, so we go through the motions and get work done as it needs to be done. And three, interruptions abound! Questions from coworkers and bosses, meetings, phones ringing and loud conversations in the next cubicle, etc. (There’s a meeting at point C in the graph; notice what it does to productivity.) These elements all make it extremely challenging to get into a productive workflow.

By the time we get to eleven and beyond (point D), the relentless efforts to work without getting into a satisfying flow cause mental exhaustion, and we’re just waiting for lunch and probably checking our favorite social media or news sites.

Getting back from lunch, we’re not feeling well rested (especially if it’s a short lunch where we have to eat as fast as we can). We might be drowsy after having just eaten, and we’re getting set for another long period of work, so there’s no need to push too hard (the long upward slope toward some sort of decent work, point E).

And then F is the slowdown to the end of the day. That feeling of ennui usually hits at three or four in the afternoon; I can’t recall anyone I’ve worked with (or myself) being at the top of their game between four and five in the afternoon.

This is just one day. Figure 5.6 is an example of a realistic workweek, showing even wilder variations. Monday we’re a little slow to get started. Tuesday we’re a little more productive. But we didn’t sleep well Tuesday night, resulting in pretending not to be a zombie on Wednesday, exhibiting maximum presenteeism, taking up space but adding zero value.

Thursday might be a more productive day – maybe fewer meetings, or a little more sleep Wednesday night. And Friday – ah, Friday – the day we wish we were somewhere else. We finish some tasks and plan for next week (or, more likely, for the weekend). We’re tired, we’re done. When is five o’clock coming?

Remember, we’re not talking about the ability to merely go through the motions of work. This can be done for many hours and many days if we’re talking about simply doing (laying bricks, typing words, greeting customers). While this still counts as working, it’s not true productivity, which we earlier referred to as work goodness.

Work goodness means being fully functional and immersed in a flow state, where we can question and improve our work to create new solutions and paradigms and give our best.

It might feel like we’re being productive at four when we’re expending energy and effort to read that same sentence for the fifth time in a row. But is your productivity anywhere near what it was in the morning when your mind was fresh? Are you anywhere near as capable of thinking through a problem and producing a solution? When you’re serving a customer, are you giving them your best or just your adequate?

Figure 5.6. In this graph of realistic productivity versus day and time of week for a human (rigid workplace), the human starts work at nine each day and finish at five. They have a lunch break from twelve to one. They work from Monday to Friday.

An interesting and frightening illustration of how our abilities vary while working long, rigid hours was found in a study on the consistency (quality) of judges’ parole decisions at different times of the day.

The judges were significantly more likely to be lenient and release prisoners at the start of the day and just after lunch than at any other times. Said the researchers: “You are anywhere between two and six times as likely to be released if you’re one of the first three prisoners considered versus the last three prisoners considered.”5

These highly trained and experienced professionals, who hold people’s lives in their hands, made decisions willy-nilly based on how long they’d been working for the day. That’s like having a machine that’s designed to make circles slowly revert to making squares as the day wears on.

I’ll say this one more time: human productivity is far from linear.

My analysis above should raise some questions, such as why on earth would I pay someone by the hour if not every hour is the same? And aren’t we wasting the company’s and the individual’s time by operating for all those hours at sub-optimal productivity?

And if we combine these ideas with the last couple of chapters, we should be angry. Not only are we not being productive with this rigid adherence to time and place, we’re causing incredible problems for individuals and society. We’re sucking energy out of employees for little productivity. It’s like driving a car in first gear – you use a hell of a lot of fuel and get nowhere.

When an employee is sitting there at four waiting for five to arrive, it costs the business, the employee, the employee’s family, and the world. The business is using their precious time and energy and benefiting not one bit.

That makes me sad and mad, and I hope you feel the same.

The Energy Bucket

Why can’t humans just be 100 percent productive all day, every day, like a robot?

It comes down to one thing: different energy sources.

Energy is a clear concept when you talk about a machine: you plug it into a power outlet, flick the switch, electricity flows through its circuits, and through the wonders of physics it does whatever it’s programmed to do. The same goes for a machine that’s powered by combustion, or hydraulics, or wind, or whatever. They all receive their energy directly from some power source, and as long as they’re connected to that power source, they’ll keep doing whatever it is they do, to their maximum capacity. Disconnect them or turn them off and they stop. Simple.

Humans are more complicated. Yes, in a practical sense we do have a direct energy source. After we eat food, our body converts it to energy for our cells, which allows us to move, think, and breathe.

But if a human has enough food to eat, will they automatically be energized and working to their full capacity at their job?

What about someone who’s eaten enough, but only slept an average of four hours for the last few nights? Will they be productive? Or will they be functioning as if they were drunk?

Let’s say someone has had enough food and regularly gets seven or eight hours of sleep, but they’ve received an eviction notice and need to find somewhere to live by the end of the week. Would this person be highly productive and focused on getting their job done, using their brain to its full creative capacity? Or would the fear of not having a secure residence be taking up most of their mental space?

What about the person who’s well-fed, and well-slept, and has secure housing, but is currently in a rough patch with their partner, and hasn’t had sex, or even been hugged or kissed, for a few weeks? Will they be giving their best at work? Or will they feel empty and deprived, and uninspired in the office?

What about the person who hasn’t had a holiday for twelve months? Will they be skipping through the door ready to change the world? Or what about the person who comes in on a Friday morning after a full week of long days, who hasn’t had any chance to relax?

What about the person who hasn’t learned anything new and has been doing the exact same thing day after day after day for months? Will they be putting their all into their work, finding ways to improve processes, reduce waste, or please customers?

What about the person who has no control over their job? Where they do it, when they do it, how they do it. It’s set in stone. They don’t have any freedom to make decisions or be creative. Will they be tapping into their energetic and productive potential?

What about the person who sees no meaning in their work and is just there to make some money? And they have no idea how their work fits into the bigger picture of what the company is trying to achieve? Will they be putting in more than the bare minimum?

What if someone hasn’t seen a tree, or been under the sun, for a few weeks? What if they don’t have any natural light or views of the outside world from their workspace?

Are these things starting to look familiar?

Are you getting sick of rhetorical questions?

As you might have guessed, we’re revisiting the fundamental human needs. They were introduced in Chapter 3 as requirements to be fully human. Any unfulfilled need causes damage to our bodies and minds, and for optimal health and well-being we should have a balanced fulfillment of all our needs.

I’m now going to extend this concept to work productivity, and say that if we want an employee or manager to be functioning to the best of their ability, they, again, need a balanced fulfillment of all of their fundamental human needs. A dearth of any single need will take away from that person’s ability to be fully productive. To help conceptualize this as our energy source, I’ve created the energy bucket.

This bucket is floating above your head. In this bucket is a luminescent gold substance that looks and behaves like a liquid, but it’s completely weightless.

This shiny liquid is your energy – your capacity to be productive, your capacity to do, to think, and to care.

The bucket and the energetic substance float around with you day and night. The fuller the bucket is, the more capable you are of doing and thinking and caring. The emptier it is, the less capable you are of doing and thinking and caring. This is the energy bucket (Figure 5.7), and it has the following characteristics.

1. It’s divided into ten compartments, one for each of the fundamental human needs discussed in Chapter 3. The only way to fill the bucket is to fill each individual compartment, and the only way to fill each compartment is to satisfy the particular human need represented by that compartment.

You can’t fill the creation compartment by eating. You can’t fill the participation compartment by reading a book. You can’t fill the freedom compartment by hugging your partner. You can fill each compartment only with whatever satisfies that need. (Remembering that some things can satisfy multiple needs at the same time,* such as dancing, which helps to fulfill participation, affection, creation, identity, understanding, subsistence, and protection needs all at the same time to various degrees.)

2. The compartments aren’t comparable in volume or in the number or amount of satisfiers necessary to fill them. For instance, to fill the subsistence part of the bucket, you would need food and water every day, whereas to fill the affection compartment, perhaps a good lunch or dinner with friends once a week is enough.

These requirements are different for different people, different stages of life, different cultures, even different days. But a safe rule of thumb is that each compartment needs regular fulfillment. The optimal amount is personal, and you feel when it’s filled or it’s not.

3. The gold liquid, our energy, is constantly draining from each of the compartments: it fuels our capacity to do and think and care, and it also evaporates over time. If you’re sitting around doing nothing, every compartment will still empty out (except perhaps leisure, which is refilled by doing just that, or nature, if your nothing involves grass and sunlight).

Figure 5.7. Each compartment of the energy bucket corresponds to one of the ten fundamental human needs from Max-Neef’s modified list. It’s displayed here as transparent to make clear that the compartments are separate from each other and that their levels of fullness are independent of each other.

As soon as any of the compartments is filled and the source of satisfaction is removed, it begins to empty. For example, if you finish eating a meal, your subsistence compartment will likely be full, but as that food is used for energy, and your stomach empties, that compartment also empties until the next meal.

Meeting with friends will help fill the affection and participation compartments, but as soon as you leave them these compartments will slowly empty until you do something else with other people that satisfies these needs, such as coming home to your family or meeting colleagues for lunch.

4. Some things drain the entire bucket much faster than others. Things such as stress, commuting, being in an open-plan office, too much pressure from work or too much work, social rejection, abuse, and bullying. These things are the opposite of the things that add to the bucket, and they drain it, fast.

5. The goal with the energy bucket is not to have every compartment 100 percent full at all times. Not only would this be impossible, especially when filling one compartment often drains other compartments (work can fill participation and understanding but drain leisure and freedom), it’s also unnecessary. As long as each compartment is filled often enough that a person doesn’t feel chronically deprived of any particular need, they will have enough energy to do and think and care.

In fact, emptying and filling the compartments provides healthy and motivating hunger followed by satisfaction, much as a meal is truly satisfying only when you’re hungry. Some deprivation is a good thing.

What we want to avoid is chronic unfulfillment – compartments never getting a chance to completely fill, or remaining empty for long periods of time. That’s when we move away from hunger (good) and toward poverty (bad).

6. If one compartment is chronically unfilled, even if all the others are completely full, it drastically impacts a person’s ability to do and think and care. This is a poverty of a human need, and, as described in Chapter 3, a poverty of any individual need creates pathologies, and it certainly takes away from someone’s ability to be fully productive at work or in any other arena of their lives.

Someone who has worked fourteen days without a break would have a completely empty leisure compartment. Even if this person somehow managed to keep every other compartment filled, they wouldn’t be able to give their best to their work. They’ll have a poverty of this one need, and their brain (and body, if their job is physical) will be starving for a chance to switch off and relax.

At this point, even if all other compartments are full, it wouldn’t be right to say, “Well, their Energy Compartment is 90 percent full, so they should still be productive.” No. If one compartment is empty, the whole bucket may as well be empty. It’s only when every compartment is consistently filled that we can consider the energy bucket to be filled.

This concept occurred to me long before I’d read about humans having various fundamental needs, when I was working in a rigid workplace, doing eight-to-ten-hour days in an office and commuting over an hour each way.

I would get home and feel completely drained of all energy and enthusiasm; I had no capacity to do anything but sit in front of the TV, eat dinner, and then go to sleep.

I even noticed that same empty feeling the morning after an especially stressful commute. I was devoid of energy even before I turned on the computer. I felt the same way when I hadn’t taken a day off in months.

On the other hand, things unrelated to sleep or rest or stress increased my energy and productivity immensely: hanging out with friends, doing something creative, going for a walk in the woods.

I pictured a magical bucket that held and supplied me with all of my energy, and I said things like, “Man, my bucket is empty” or “Oh yeah, my bucket is so full now.” (To which my partner would say, “What the hell are you talking about?”)

Hence the energy bucket was born. In the years since, especially after learning about our fundamental needs, I can usually identify which compartments of my bucket are empty or full at any particular time. And I’m keenly aware that if any of my compartments are empty, my entire quality of life and ability to do my best work will be compromised.

The concept may sound like pseudoscience, but it’s a giant step up from thinking that the only things people need in order to be constantly productive at work are enough food, money, and motivational speeches.

The concept of the energy bucket provides powerful and practical knowledge: how to boost productivity from its source. It enables us to determine if our power source is depleted or full, and how to fill it.

We fill it by being completely human, as often as possible! And we do that by ensuring that all of our fundamental needs are fulfilled on a regular basis. That’s our power switch.

Empty Buckets Are Expensive

As people’s energy buckets empty, their ability to do their best work – including being able to think properly and caring about what they’re doing – is compromised.

That last point, caring about their work and the company they work for, is called engagement, and it’s a critical metric in business.

Companies have realized that their employees being engaged is much more important than them merely being present, that someone who’s there but would rather not be there might as well not be there at all. They’re not worth the money you’re spending to keep them there. Compared to someone who’s engaged, they make more mistakes (which take time and money to fix), they’re more likely to be injured or to injure someone else, they’re less likely to go above and beyond their job description, they take more sick days, and they’re probably going to leave soon and need to be replaced anyway.

Gallup quantified these effects by comparing “business units” that are in the top quartile in employee engagement to those in the bottom quartile and found that the latter had seen:

• Higher absenteeism (sick days) – by 37 percent

• Higher turnover in “high-turnover organizations” (e.g., retail) – by 25 percent

• Higher turnover in “low-turnover organizations” (e.g., government) – by 65 percent

• Higher shrinkage (theft) – by 28 percent

• More safety incidents – by 48 percent

• More patient safety incidents (for those in healthcare) – by 41 percent

• More quality defects – by 41 percent6

All of these differences are expensive: overall, highly engaged business units achieve 21 percent greater profitability than less engaged units.7 Just one of these elements, turnover, can cost tens of thousands of dollars for an entry-level position, and one-and-a-half to two times an employee’s salary for more technical or senior-level roles. (Costs include “hiring, onboarding, training, ramp time to peak productivity, the loss of engagement from others due to high turnover, higher business error rates, and general culture impacts.”)8

It costs to have empty buckets!

If we’re aware of what fills the bucket and what empties the bucket, can’t we, shouldn’t we, use that information to avoid or reduce things that empty it, and increase or add things that fill it?

Given that this is a book about flexibility, I will of course be saying that flexibility helps to fill the bucket, and thus it increases engagement and productivity. But before I do, I’ll step back from the “if I have a hammer, everything is a nail” position and emphasise that flexibility is only one tool on the belt, one important aspect of taking a human-centered approach to boosting employee engagement. All of these tools, coincidentally, correspond to filling various compartments in the employee’s bucket. They include:

• Growth and development in a job and career

• Alignment between the job and their skills and interests

• Appropriate resources to do the job

• Feeling valued and cared for

• Clear goals and timely feedback

• Feeling like they belong to the team

• Their work demonstrating a noticeable impact on the business; the business demonstrating a noticeable impact on the world

• Autonomy and decision-making ability

• Good communication between them and their managers (and good relationships in general)

• Satisfactory pay

• Good relationships with other employees (e.g., no harassment and bullying, friendships, and connections)

• Good physical environment (e.g., air and light)

• Job security

That said, increased flexibility on its own is a powerful tool on this belt!

What might a productivity graph look like for a non-rigid day, when someone has the flexibility to take care of their needs in a sustainable way?

We’ll consider the example of someone who is using two different types of flexibility: working remotely, from a home office, and being able to choose when they work during the day (flexitime). They’re still working roughly seven to eight hours a day in this example.

To start the day, this person doesn’t need to travel to their office, which removes the stress and time wasted in the morning commute. They’re a morning person and decide that they get their best work done early so soon as they wake up, have a shower, and make a coffee, they turn on the computer and get straight to it (point A on Figure 5.8).

Their productivity at this point is at maximum because: 1) they’re not drained from the commute, 2) they’re harnessing their own productive rhythm of the day, 3) there are no interruptions from colleagues just dropping by, and 4) they’re already energized and engaged from being able to live sustainably on previous days and weeks.

This person’s productivity slowly drops over the morning (B) because they are still human, but for five to six hours they’re working near their full productivity, doing amazing things that our previous example of someone stuck in a rigid workplace would struggle to achieve on any day.

Then they stop. Unlike the people in the rigid workplace, this person is not going to try to push through low productivity and is not going to drain their bucket for a low return while they wait for lunch or the end of the day. They’ve already accomplished so much for the day, they deserve a damned break (point C)!

They’re going to use a few hours to refill their bucket! Or, to mix metaphors and borrow from the story of the lumberjack, they’re going to go away and sharpen their axe, ready to chop down another tree later.

They have a lazy lunch while watching a couple of episodes of whatever is on Netflix, fully resting their mind with a leisurely activity. And since they know they’ll be crappy at doing their work in the early afternoon after eating, they’re going to the gym after lunch instead, improving their overall health and taking their mind even further off work, which will give a boost of energy for the late afternoon.

This is where we get to point D. Even though this person has already had a supremely productive morning, a morning that they could only dream about in their old open-plan office, they’ve realized that they can catch a second wind of high productivity with the way they’ve structured their day, where work and life coexist in an integrated way.

Figure 5.8: Example of the productivity of a human who works flexibly; in this case, they’re working remotely and can choose when to do their work. This person is still expected to work seven to eight hours a day, but this isn’t tracked or policed by management.

This highly productive and balanced day can be repeated multiple times in a week. Employees aren’t holding their breath, and they’re not putting up with poverties until the weekend. They’re living sustainably, every day, and for multiple successive days they’ll be able to hit high levels of productivity. This is unheard of in rigid workplaces.

Not every day will be exactly like Figure 5.8. There are ups and downs and unknowns in life, regardless of someone’s level of flexibility. Some days might be terrible and the employee will get nothing done. But then they’ll make up for it on another, immensely productive, day.

Or perhaps one day they decide to go to a judo class in the early morning, or they need some extra sleep and start work at ten. But then they work a solid, productive four hours until two, doing more than they would in a full day in a rigid workplace while also taking care of their health.

Different types of flexibility work for different people, but all of them will increase people’s capacity to do and to think and to care, and that’s good for business.

I’m going to end this chapter by bad-mouthing a popular type of flexibility.

I mentioned in Chapter 2 that I don’t like compressed workweeks, and now I’ll explain why. The compressed workweek has some drawbacks that give flexibility a bad name, and in doing so it gives fuel to the polite skeptics. It also perpetuates a complete lack of understanding of human productivity.

Remember those pretty graphs from earlier in the chapter? The one for the assumed productivity in a compressed workweek would look very similar to Figures 5.3 and 5.4, where our human just keeps on being 100 percent productive for every minute of the day and week but now it’s for ten hours a day, four days a week. There’s no lull in productivity on any of those days except when they stop for lunch or finish for the day.

As we’ve already discussed, in real life people aren’t even productive for an eight-hour workday, not even close (see Figures 5.5 and 5.6). So sticking another two hours of work onto those unproductive eight hours should hopefully sound completely, well, dumb.

In a ten-hour day, the negative effects of a rigid day are heightened:

• People will try to conserve even more energy in a longer day, so they’ll spend even more time just going through the motions. Simply being at work for this long is hard work.

• People have even less time for the daily fulfillment of their human needs. With ten hours of work, plus one or two hours of commuting, only a few hours are left to do anything else, which will be mostly recovery time – eating something and sitting in front of the TV. This will hardly serve to refill their bucket.

• There’s less incentive to be productive and a greater focus on time. In fact, there’s a greater disincentive to be productive: because this person is sacrificing so many hours at work, they feel that they don’t need to achieve much more than being present in order to earn their money.

• People will spend more time each day in a state of stress, which will affect their productivity and their health. Long days of work, and the associated work-family conflict, are two of the worst workplace exposures for health. The human cost of this practice is expensive.

I can already hear the argument: the four days of toil are worth it for a three-day weekend. And, yes, that extra day of complete freedom has been a big reason for the popularity of the compressed week. But, by the time the long weekend arrives, the employee’s needs are screaming. They’ve been swimming their laps without a breath.

They haven’t had much exercise. They’re sacrificing sleep to try to get other stuff done in the short amount of the day they have left. They haven’t had much quality time with their family. They’re not social with friends or the community on those workdays. And the list goes on.

Employees can’t live sustainably during this workweek, so the long weekend becomes a binge of rest and recovery before they leap into the next exhausting set of four days. And much of that extra day off will be used for the errands and housework that couldn’t be completed during the four highly rigid days of work.

The compressed workweek perfectly encapsulates the assumption that humans are robots, with infinite capacity to be productive. It truly is dumb. If you’re looking to reduce the number of workdays as a form of flexibility (to provide more freedom to employees, reduce traffic, and reduce energy costs for buildings, for instance), simply chopping off that fifth day without adding those hours onto the rest of the week, and without reducing employees’ overall pay, is a much better option. This is called reduced hours with full pay, and it will be explained in agonizing detail in the next chapter.

* I’m aware that robots are often unpredictable. They’re shut down for repairs, maintenance, and cleaning, and they’re slowed down or sped up in the search for optimum production and quality, but this isn’t a book about robot maintenance, so we’re going to ignore these variables.

* Max-Neef refers to these as synergistic satisfiers; I call them bucket boosters.