RYUTA MINAMI

Can he that speaks with the tongue of an enemy be a good counsellor, or no?

Henry VI:2 (4. 5.170–2)

At the beginning and the end of the preface to his Eibungaku no hanashi [Tales of English Literature], Yamato Yasuo, a well-established professor of English, repeated the following jingoistic passage: ‘Down with the Yanks and the Brits! They are our enemies. Seize Shakespeare! He is ours as well (1, 3).’1

It seems somewhat strange that a leading scholar of English could both decry the Britain and the United States and also write an introductory history of English literature for students, claiming Shakespeare – a cultural icon of Britain – for the Japanese. Yet this somewhat self-contradictory slogan vividly reflects the sentiments shared by other Japanese scholars of English studies and by the general public. Japan witnessed sporadic but harsh anti-English measures taken by the governmental and non-governmental institutions; these acts were meant not only to stir up hostility among the general public during the Pacific War but also to respond to the already existing antagonism toward the English-speaking Allies (Oishi 20). Under such adverse circumstances, most Japanese scholars of English could do little but support the nation’s cause by emphasizing the necessity and utility of English studies.

Peter Firchow recently discussed the tragic conflict between vocation and national identity that German scholars of English literature experienced during the First World War. During the late 1930s and the early 1940s most Japanese scholars and teachers of English faced a similar conflict, and many opted for nation over profession, though not in equal measure. In this sense Yamato’s jingoistic and naïve slogan illustrates the ambiguous position of Shakespeare in wartime Japan where anything English or American was likely to be driven out of daily life. Unlike in Germany and Italy, Shakespeare was not performed on stage during the last five years of the war.2 Shakespeare in wartime Japan was something to be read, discussed, and imagined as a socio-political product distinct from the Japanese stage. This essay will examine how Shakespeare became both an icon of the enemy culture and an object of desire in wartime Japan.

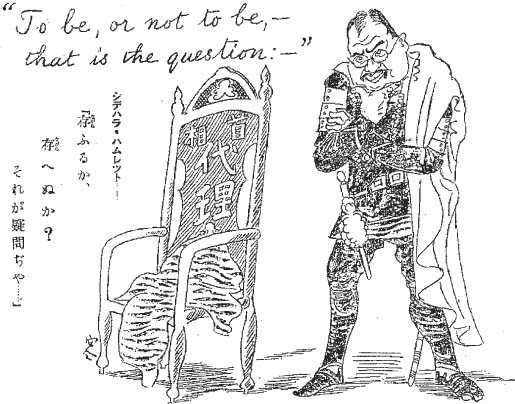

Shakespeare had played a significant part in Japan when it was establishing itself as a modern, westernized nation state in the late nineteenth century. In an introductory scene added to the first Japanese adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice in 1885, one of the Japanese characters discussing the values of Western literature states that Shakespeare is an important means for Japan, a ‘half-civilized nation,’ to become a fully civilized modern nation state.3 Similarly, in the preface to the first translation of Hamlet, published in 1905, the translator Tozawa Köya remarked: ‘Japan is now preparing to meet the Baltic Fleet, and isn’t Japan equal to Elizabethan England, which was ready to beat the Spanish Armada?’ Comparisons between rising Japan and Elizabethan England were preferred to comparisons between Japan and modern England, and were repeated in various discourses on nationalistic appropriation of Shakespeare around the turn of the twentieth century. By the 1930s Shakespeare had become an indispensable part of cultural literacy for Japanese elites and intellectuals, and Shakespeare’s plays were often referred to in newspaper articles or noted by statesmen in various socio-political contexts. One example can be found in a newspaper caricature published by the Asahi on 7 December 1932. This cartoon (see fig. 8.1) shows Baron Shidehara, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hamlet-like in his hesitation to step in as the Acting Prime Minister after the Prime Minister had been seriously injured by a right-wing assassin. Rather than finding this caricature offensive, Sidehara, who was well-read in English, seems to have enjoyed the connection, and commented in an interview shortly thereafter that he appreciated being compared to Hamlet. As English was not (and is not) the language used in daily life in Japan, it is noteworthy that the famous quotation – ‘To be or not to be’ – is given in English as well as Japanese.

8.1. Cartoon of Baron Shidehara, Minister of Foreign Affairs as Hamlet: ‘To be or not to be.’ Asahi 7 (December 1932).

In a similar reference to Hamlet that same year, a newspaper derisively compared the General Assembly of the League of Nations to the Prince, referring to the length of time the Assembly took to determine the cause of the Manchurian incident (Furugaki 2).4 Nearly a decade later, in July 1941 – and less than six months before the outbreak of the Pacific War – Fukuhara Rintarö, a leading scholar of English, referred to Shakespeare and compared Japan to Elizabethan England in a newspaper article asserting the significance of studying English literature in Japan. It is noteworthy that in spite of his final statement – ‘It is Japan that will soon defeat the Invincible Fleet’ – he compared Japan to Shakespearean England, despite the fact that Britain was one of Japan’s enemy countries.

Further, Shakespeare’s significant cultural status in early twentieth-century Japan is succinctly illustrated by the following comment on the first Japanese translation of Shakespeare’s plays. In Nippon Eigaku Hattatsushi [The Development of English Studies in Japan] (1933), Takemura Satoru proudly writes:

In general, almost all the first- or second-rate civilized nations in the world possess the complete Shakespeare canon in translation. As far as I know, Germany has about ten different German versions of Shakespeare, France has eight or nine, Russia four or five, Spain, Italy, Holland, Poland, Sweden, Denmark, and Hungary have at least one or two translations of his complete works respectively … I am afraid Japan was the only first-rate nation that had not had Shakespeare’s complete works in Japanese. But now thanks to the publication of Dr Tsubouchi’s translation of Shakespeare’s complete works, Japan has managed to go beyond the level of China, Turkey, Persia, and other second- or third-rate countries. Japan can rank with the Great Powers in the world. (210)

Here the ‘possession’ of Shakespeare in the vernacular is seen as a proof of a civilized nation. It must be noted that, at the time of publication, Japan was already in a state of war. Also, Takemura’s insistence that the Empire of Japan had already become a first-rate nation actually reflects the atmosphere of the nation that, in the previous year, had invaded China in defiance of the great Western powers and had established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Yet the socio-cultural importance of Shakespeare as an object of such nationalist appropriation might have become difficult to maintain when Japan started a war with America and Britain. The hostile relationship between these countries problematized, and even jeopardized, the hitherto established position of Shakespeare as an indicator of cultural sophistication suitable for a first-rate modern nation.

In his autobiography Twischen Inn und Themse [Between the Inns and the Thames Rivers] (1936), Alois Brandl writes, ‘No segment of the German population was hit as hard by the World War as the aspiring troop of Anglicists who already numbered in the thousands’ (qtd. in Firchow 61). This was equally true of the many Japanese scholars and teachers of English during the Second World War, of whom there were more than one thousand; the English Literary Society of Japan was founded in 1928 with about 1,000 members, and the Shakespeare Association of Japan was established in the following year. Writing about German scholars of English, Firchow remarks that the ‘majority of Anglicists seem instead to have used their specialized knowledge chiefly to find real or imaginary weaknesses in literary and cultural armor’ (62). Unlike their German counterparts in the First World War, most Japanese Anglicists in the 1940s neither made ‘use of their professional expertise to defend the English against attack in the popular press’ nor proceeded ‘to sling literary hate and mud’ (62). There were some scholars, such as Yamato Yasuo, who launched a war of words, but the majority of Japanese scholars of English merely insisted that English literary studies and English language teaching could be important weapons for the Japanese Empire. Soon after the imperial declaration of war in December 1941, leading scholars of English published articles in newspapers and magazines arguing that English should be studied more than ever so that the Japanese could understand English-speaking people and their culture. They also insisted that their expertise in Anglo-American culture and society would serve to develop the culture of a ‘Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere’ (Oishi 10–12; Miyazaki 11–22). One possible reason for Japanese English scholars’ prompt and somewhat desperate responses was that they were likely to be regarded as worse than useless, and even harmful, because of their knowledge of the United States and Britain.5

It should be noted that, in the first half of the 1940s, the Japanese government tried to dispose of anything related to America and Britain. The brief chronology presented in table 8.1 (pp. 173–6) reveals how desperately the Japanese government tried to eradicate anything English or American from the country even before the Pacific War broke out. Although most of the prohibitions against anything English seem ridiculous today, they were seriously regarded at the time; indeed, the government’s actions appear extensive and decisive. In 1942, for example, as many as 1,492 teachers of English at girls’ higher educational institutions (equivalent to women’s colleges) were made redundant on a two-month notice. This measure clearly suggests that the teachers’ knowledge of English was regarded as a threat to the government’s anti-American and anti-British propaganda. In his essay entitled ‘The root of our enemy lies in the English language’ military analyst Mutô Teiichi insisted that:

English, this abominable enemy language, must be expelled by all means. I simply don’t understand why some Japanese admire and cling to English when our country is struggling to destroy Britain and America. It is a shame that Japanese contains too many borrowings from the enemy language, such as nyûsu [news] and anaunsâ [announcer]. They should be discarded.6

8.2. Photographs of Japanese products with English names or words: ‘Are these Japanese products made for Japanese people?’ The Photographic Weekly Bulletin 257 (3 February 1943), 5–6.

As if in response, on 3 February 1943 the Shashin Shûhô [The Photographic Weekly Bulletin], which was published by the Cabinet’s Information Board in order to provide extensive publicity for national policy in a straightforward and accessible manner, bitterly criticized Japanese products with English names and words (7–8; see fig. 8.2); the preceding pages of the same issue decried the use of English words in signboards. The hostility expressed toward the United States and Britain may also be seen in the Great East Asia Society of Literature, founded in 1942; the main theme at the annual conferences of the Society (held for three consecutive years, 1942 to 1944) was either critical reevaluation (that is, devaluation) or annihilation of American and British culture.7

In spite of or because of such difficult circumstances, the Japanese elite and intellectuals continued to make an exception for Shakespeare. In an article in the Asahi on 8 January 1941, Shakespeare plays, including Romeo and Juliet, are found on the list of recommended books for teenage girls, along with Tolstoy’s works and Greek myths (‘Naniwo Yomuka’ 4). How could it be that Shakespeare continued to be both desired and denounced?

There are at least two notable characteristics of the discourses on the nationalist appropriation of Shakespeare in wartime Japan: one is the frequent reference made to Thomas Carlyle’s On Heroes, Hero-worship, and the Heroic in History (1841) as a way of disqualifying Britain as the sole possessor of Shakespeare; the other is a marked tendency to identify Shakespeare as part of German culture. When Yamato concluded his slogan with ‘He is ours as well,’ he knew that his readers would immediately understand his implicit reference to Carlyle’s famous passage and to the British colonies in Asia.

Carlyle’s On Heroes was one of the most popular books among Japanese students in higher education. The first Japanese translation was published in 1898, and at least three other versions were published and re-printed during the next thirty years (1912, 1914, 1922, 1923, and 1933). The majority of the elite and intellectuals of the 1930s had read Carlyle either in English or in Japanese, and were familiar with the following passage:

For our honour among foreign nations, as an ornament to our English Household, what item is there that we would not surrender rather than him? Consider now, if they asked us, Will you give up your Indian Empire or your Shakespeare, you English; never have had any Indian Empire, or never have had any Shakespeare? Really it were a grave question. Official persons would answer doubtless in official language; but we, for our part too, should not we be forced to answer: Indian Empire, or no Indian Empire; we cannot do without Shakespeare! Indian Empire will go, at any rate, some day; but this Shakespeare does not go, he lasts forever with us; we cannot give up – our Shakespeare! (148; emphasis added)

One year before Yamato wrote his preface, Hakuchô Masamune, a novelist, playwright, and critic, wrote an article, ‘Indo ka Saôka’ [Indian Empire or Shakespeare], which was published in the Yomiuri on 6 July 1940. In it he writes:

Imagine you say to an Englishman today, ‘Since your country has the honour of having produced Shakespeare the best poet-playwright in the world, you wouldn’t care about India and other colonies at all.’ No Englishman would agree with you. The Englishman is more likely to say that he would rather give up the rights to publish or perform Shakespeare’s plays in order to secure all the colonies. He would rather wish to have a Wellington or a Nelson, and not a Shakespeare today. (1)

Masamune suggests that the British Empire was declining in national power and thus implied that Britain was no longer entitled to enjoy the exclusive possession of Shakespeare.8 This kind of ‘disqualification’ of Britain as the home of Shakespeare was further emphasized in 1943 when the American government’s prohibition of the performance of The Merchant of Venice was reported by newspapers and magazines. Explaining how the Americans came to ban the performance of the play, the front page column of the Yomiuri on 4 September 1943, concludes that:

Britain once had Carlyle, who said ‘Indian Empire will go, at any rate, some day; but this Shakespeare does not go, he lasts forever with us; we cannot give up our Shakespeare!’ But Britain had already let American soldiers enter India the other day. And now Britain let the Jewish Americans obliterate Shakespeare from the stage. I wonder how the British are feeling now! (1)

If Britain were not eligible for ownership of Shakespeare, who, they wondered, would be entitled to ‘take possession.’ The answer was Germany. Since the early 1930s, along with recurrent ironical references to Carlyle, both Shakespeare productions in Germany and German studies of Shakespeare had been frequently reported and praised in the press, as if ‘Shakespeare’ were a German Bard. Showing how thoroughly Shakespeare had been ‘de-anglicized’ in Germany, a country allied with Japan (see Habicht, ‘Topoi’ and ‘Shakespeare’), the Japanese press suggested the possibilities of owning Shakespeare in the then anti-British Japan.

Interestingly enough, on 30 December 1939, the Taiwan Nichi-Nichi Shimpo [Taiwan Daily News] published an article entitled ‘Recent Shakespeare Studies in Germany,’ introducing Brandl’s Twischen Inn und Themse. Although the writer seems to have mistaken this autobiography of an English professor at one of Berlin’s universities for a biography of Shakespeare, what is to be noted here is that news about German studies on Shakespeare was circulated through Japan and its colonies in the popular press; in contrast, it seems there was almost no coverage of their British counterparts even before the onset of the Pacific War. On 13 September 1941, the front-page editorial of the Yomiuri maintained that it was German literati such as Goethe, Christoph Wieland, and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing that ‘taught’ English people the greatness of Shakespeare. The editorial also pointed out that the German Shakespeare Society (Deutsche Shakespeare Gesellschaft) was the oldest society of its kind in Europe, with a history of some 80 years. The editorial column concludes with the statement that in Germany Shakespeare’s plays were performed more often than plays by other dramatists even though they were written by the playwright of their enemy country. One of the last newspaper articles about German Shakespeare was a review by Watanabe Mamoru published in Yomiuri on 21 January 1944, of the latest production of The Merchant of Venice presented at the Burgtheater in Vienna. The review, which includes a stage photograph (a rarity at this time in Japan), praised the production and maintained that German people believed that Shakespeare must not be monopolized by Britain.

We may certainly assert that, in the imagination of the Japanese during the 1930s and early 1940s, Shakespeare was considered a part, not only of British, but also of German culture and German classics, a fact that seems to explain why more than 10,000 copies of Friedrich Gundolf’s Shakespeare und der Deutsche Geist were sold in Japanese translation between 1941 and 1943. Since the number of scholars of English literature in Japan at the time was about 1,000, the enormous sales suggest that Gundolf’s book enjoyed a larger readership than usual of books on English literature.

The early and successful appropriation of Shakespeare in Germany ensured the possibility of the Japanese appropriating the English playwright as a ‘Japanese Bard,’ or at least, the bard of an allied country. It is significant that the subject of the Shakespearean study published just before Gundolf’s Shakespeare was the reception of Shakespeare in Japan (see table 8.1, pp. 173–6), thus emphasizing how long the two allied countries had possessed Shakespeare and linking them once again. Japanese Shakespeare remained proof that Japan was a culturally enlightened and civilized nation, though this Shakespeare was a safe socio-cultural as well as political product made, for the most part, in Germany.

Table 8.1. Chronology comparing anti-English measures and major events with Shakespeare publications and productions All Japanese names are given in the Japanese order, that is, family name followed by given name.

Date |

Prohibitions and important events |

Publications of books on Shakespeare |

Productions of Shakespeare plays |

1937 January |

|

|

The Merry Wives of Windsor trans. Mikami Isao and Nishikawa Masami; dir. Senda Koreya; [Shin Tsukiji Company]. |

July |

Marco Polo Bridge incident (July 7) begins the second Sino-Japanese war. |

|

|

September |

|

Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Smirnov, Shakespeare: A Marxist Interpretation trans. Magami Yoshitarô (Tokyo: Bieidô). |

|

1938 February |

|

A.C. Bradley, Shakespearean Tragedy, part 1, trans. Nakanishi Shintarô (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten).1 |

|

May–June |

|

|

Hamlet trans. Mikami Isao and Okahashi Hiroshi; dir. Yamakawa Yukiyo and Okakura Shirô; [Shin Tsukiji Company]. |

December |

|

|

Hamlet Mikami Isao and Okahashi Hiroshi; dir. Yamakawa Yukiyo; [Shin Tsukiji Company]. |

——— |

|

|

|

|

Stendhal, Racine et Shakespeare, trans. Satô Masaaki (Tokyo: Aoki Shoten).2 Nakanishi Shintaô, Sheikusupia Joron [An Introduction to Shakespeare] (Tokyo: Kenkyusha). |

|

|

|

|

A.C. Bradley, Shakespearean Tragedy (2), trans. Nakanishi Shintarô (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten), translation of the last four chapters. |

|

November |

|

Nakanishi Shintarô, Hamlet (Tokyo: Kôbundô Shoten). |

|

1940 January |

|

|

Hamlet partial production, dir. UchimuraNaoya; [Bungaku-za Company]. |

March |

Ministry of Home Affairs bans the use of English stage names. |

|

|

May–June |

|

|

A Midsummer Night’s Dream adapted and dir. Katô Tadamatsu [Takarazuka Revue Company]. |

September |

Ministry of Railways bans English songs at stations. |

Toyoda Minor, Shakespeare in Japan (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten). |

|

October |

Ministry of Education bans the use of English names or words for names of schools. |

|

|

November |

Ministry of Finance bans the use of English words for names of tobacco products. |

|

|

Ministry of Foreign Affairs bans the use of English at press conferences for foreign correspondents. |

Friedrich Gundolf, Shakespeare und der Deutsche Geist, part 1, trans. Takeuchi Toshio (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten).3 |

|

|

June |

|

Friedrich Gundolf, Shakespeare und der Deutsche Geist, part 2, trans. Takeuchi Toshio (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten). |

|

July |

|

|

Dazai Osamu, Shin Hamlet [New Hamlet] A closet drama. Parodic adaptation, published by Bungeishunjûsha, Tokyo. |

December |

Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (7 Dec.) begins the Pacific war. The government bans the use of the term ‘Far East’ in both Japanese and English. |

|

|

|

Throughout 1941 police in large cities ban the use of English names for coffee shops and restaurants. |

|

|

1942 March |

All foreign university teachers of English are fired. |

|

|

september |

English becomes an optional subject at girls’ high schools. Many of the 1,492 full-time teachers of English fear they will become redundant. |

|

|

——— |

|

|

|

The Metropolitan Police Department bans the use of English at table-tennis matches. |

|

|

|

|

The botanical garden in Kyoto removes English signs for plant names. Through 1942 many companies change their names to remove English words. |

|

|

1943 January |

Japan Times changes its name to Nippon Times. |

|

|

|

The Ministry of Home Affairs and the Cabinet Information Board ban the performance and the sale of recordings of more than 1,000 English songs. |

|

|

February |

English words are banned from magazine titles. |

|

|

|

The Cabinet Information Board bans English signs and signboards. |

|

|

March |

Japan Baseball Association bans the use of English baseball terminology. East Asia Medical Society bans the use of English and Dutch. |

|

|

April |

Tombow Pencils stops using abbreviations H (hard) and HB (hard black) to indicate grades of pencil lead. |

|

|

May |

Patent Office bans the use of brand names that suggest American and British words. |

|

|

——— |

|

|

|

Ministry of Education bans the use of sol-fa system for naming the notes of musical scales. |

Walter Alexander Raleigh, Shakespeare, trans. Takeuchi Kouki (Tokyo: Hokkô Shobô).4 |

|

|

September |

|

Friedrich Gundolf, Shakespeare: Sein Wesen und Werk, trans. Oguchi Masaru and Asai Masao (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobô). |

|

1944 January |

Ministry of Education announces the deletion of God Save the King from English textbooks. |

|

|

|

Ministry of Education announces that references to enemy countries should be deleted from textbooks of all subiects. |

|

|

1945 August |

Atomic bombs are dropped on Hiroshima (Aug. 6) and Nagasaki (Aug. 9); Imperial Japan surrenders. |

|

|

1 A.C. Bradley's bhakespearean Irageay (1905) was first translated into Japanese in Marcn 1923 by anotner Japanese scholar ot tnglish, and nad been the single most influential critical work on Shakespeare’s plays since its publication in Japan. While Nakanishi’s new translation was favourably received, Bradley’s book itself was not a new addition to Shakespeare studies in Japan. This first volume contains only the first six chapter’s of Bradley’s work; the remaining four chapters were published in a second volume in March 1939.

2 Works on Shakespeare by authors such as Schiller, Goethe, Turgenev, Tolstoy, Coleridge, and Emerson were translated into Japanese in the early twentieth century. Because the Japanese regarded France as less of an enemy than Britain or the United States, official censorship and repression of French literature and culture was not as strict or severe as that of its English and American counterparts.

3 This first volume contains a translation of only the first two chapters; the second volume, containing chapter 3, was published in June 1941. Print runs for both volumes were high: 10,000 copies were printed for the third issue of volume 1; 5,000 copies were printed for the second edition of volume 2.

4 Sir Walter Alexander Raleigh’s Shakespeare was first introduced to Japanese scholars in 1935 in a translation by Kashiwagura Shunzo of the first chapter plus a summary of the rest of the book. Takeuchi Kouki’s translation is based on the 1907 edition.

All the Japanese names are given in the Japanese order, that is, family name followed by given name, except in cases where the names of Japanese authors are published in Anglicized form in the original. A macron (Λ) over a vowel indicates that the pronunciation is lengthened. All translations of quotations from Japanese books and articles are mine unless otherwise indicated.

1 As the first two sentences of this passage had become one of the common slogans often put up on school blackboards during the Pacific War, it probably sounded hackneyed.

2 This lack of Shakespeare performances is partly due to the fact that most stage productions of Shakespeare’s plays were given by shingeki [new drama] companies, most of which were forced by the government to disband because of their leftist leanings. For details about shingeki and Shakespeare performances in Japan, see table 8.1. Also, see Sasayama, Mulryne, and Shewring; Minami, Carruthers, and Gillies.

3 On the importance of this adaptation of The Merchant of Venice in the modernization of Japan, see Yoshihara.

4 The Manchurian incident was part of the conquest and pacification of Manchuria by the Guangdong Army (Japan’s field army in Manchuria) from September 1931 to January 1933. On 18 September 1931 the Guangdong carried out a secret bombing raid on the rails of the South Manchuria Railway (the Liutiaogou incident). They then accused the Chinese troops in Mukden (now Shenyang) of destroying the tracks and made a sudden attack on the main Chinese garrison in Mukden. By the dawn of 19 September they had gained control of the city. In December 1931 the League of Nations appointed a five-man commission, headed by the Earl of Lytton II, to determine the causes of the incidents of 18–19 September. The Lytton Report, submitted on 2 October 1932, stated that Japan was the aggressor, but the General Assembly of the League of Nations did not officially determine the causes until February 1933, when the Lytton Report was finally adopted. The newspaper article, which was published more than two months after the submission of the Lytton Report, illuminates Japan’s general concerns about the decision of the League of Nations.

5 The then Japanese government found teachers of English somewhat suspicious and dangerous in part because quite a few of them had studied or spent some time in the United States or Britain, and in part because many of them were well informed about British and American conditions. Cf. Miyazaki Yoshizo, Taiheiyô-sensou to Eibun-gakusha [The Pacific War and English Scholars] (Tokyo: Kenshusha, 1999) 23–7.

6 Mutô Teiihchi, ‘Tekishoku no Kongenwa Eigo da’ [The root of our enemy lies in the English language], The Houchi Newspaper 7 March 1942. The passage is taken from Oishi’s ‘Japanese Attitudes’ (8). The English translation is by Oishi but is quoted here with a slight alteration. It is to be noted that ‘news’ and ‘announcer’ had become Japanese words (nyûsu [news] and anaunsâ [announcer]) well before 1942.

7 The hostility against America and Britain was powerfully set out, especially in the second and third Annual Meetings of the Society in 1943 and 1944; see Haga.

8 The front-page news headline for that day was ‘Next year’s plan for wartime finance is announced.’ The fact that Masamune’s article was printed just below this top story indicates a wartime atmosphere, even though the attack on Pearl Harbor was a year and a half in the future.

Carlyle, Thomas. On Heroes and Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History. World Classics 62. London: Oxford University Press, 1935.

‘Chikatte Eibeibunka Senmetsu’ [A pledge to annihilate American and British cultures]. Asahi 26 Aug. 1943, Tokyo evening ed.: 2.

‘Doitsu no Sheikusupia Kenkyû’ [Recent Shakespeare studies in Germany]. Taiwan Nichinichi Shimpô 30 Dec. 1939, Taipei morning ed.: n.pag.

‘Eibeibunka wo Samon’ [Inquiries into American and British cultures]. Yomiuri 17 Sept. 1944, Tokyo morning ed.: 4.

Firchow, Peter Edgerly. Strange Meetings: Anglo-German Literary Encounters from 1910 to 1960. Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 2008.

Fukuhara, Rintarô. ‘Chiteki Seifukuyoku’ [The desire for intellectual conquest]. Asahi 5 July 1941, Tokyo morning ed.: 4.

Furugaki, Tetsurô. ‘Rijikai Tsuini Hamlet’ [The General Assembly has finally become a Hamlet]. Asahi 27 Dec. 1932, Tokyo morning ed.: 2.

Habicht, Werner. ‘Shakespeare and Theatre Politics in the Third Reich.’ The Play Out of Context: Transferring Plays from Culture to Culture. Ed. Hanna Sčolnicov and Peter Holland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. 110–20.

– ‘Topoi of the Shakespeare Cult in Germany,’ Literature and Its Cults: An Anthropological Approach. Budapest: Argumentum, 1994. 47–65.

Haga, Mayumi. ‘Eibeibunka no gekimetsu’ [The destruction of American and British Cultures]. Asahi 25 Aug. 1943, Tokyo morning ed.: 4.

Ishikawa, Tatsuzô. ‘Bungakusha no Teishin’ [The devotion of literati]. Asahi 25 Aug. 1943, Tokyo morning ed.: 4.

Masamune, Hakuchô. ‘Indo kaSaôka’ [India or Shakespeare]. Yomiuri 6 July 1940, Tokyo evening ed.: 1

Minami, Ryuta, Ian Carruthers, and John Gillies, eds. Performing Shakespeare in Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Miyazaki, Yoshizo. Taiheiyô-sensou to Eibun-gakusha [The Pacific war and Japanese scholars of English]. Tokyo: Kenshusha, 1999.

‘NaniwoYomuka’ [What to Read]. Asahi 8 Jan. 1941, Tokyo morning ed.: 4.

Oishi, Itsuo. ‘Japanese Attitudes toward the English Language during the Pacific War’ [In English]. Seikei Hogaku 34 (1992): 1–20.

Saitô, Takeshi. ‘Daitôa Bungakusha Taikai: Kyôei Bunka no kakuritsue’ [The Great East Asia Society of Literature: Towards the establishment of the culture of a greater East Asia co-prosperity sphere]. Taiwan Nichinichi Shimpô 3 Sept. 1943, Taipei morning ed.: n.pag.

Sasayama, Takashi, Ronnie Mulryne, and Margaret Shewring, eds. Shakespeare and the Japanese Stage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Shashin Shûhô [Photographic Weekly]. Tokyo: Naikaku jôhôbu [Cabinet Information Board]. no. 257, 3 Feb. 1943, 5–6.

‘Shidehara Hamlet’ [Baron Shidehara as Hamlet]. Cartoon. Asahi 9 Dec. 1930, Tokyo morning ed.: 2.

Takemura, Satoru, Nippon Eigaku Hattatsushi [The development of English Studies in Japan]. Tokyo: Kenshusha, 1933.

Tozawa, Koya. ‘Saô zenshû jo’ [Introduction to the complete works of Shakespeare]. Hamlet. By William Shakespeare. Trans. Tozawa Koya and Asano Wasaburô. Saô Zenshû, vol. 1, Tokyo: Dainihon Tosho, 1905. p. 3. Saô Zenshû [The complete works of Shakespeare], 10 vols. Tokyo: Dainihon Tosho, 1905–08.

Watanabe, Mamoru. ‘Yûyûtaru Doitsu Senryoku: sheikusupia no geki wo jôen’ [The vast military potential of Germany: a Shakespeare play was produced]. Yomiuri 21 Jan. 1944, Tokyo morning ed.: 4.

Yamato, Yasuo. Eibungaku no hanashi [Tales of English literature]. Tokyo: Kembunsha, 1942.

Yoshihara, Yukari. ‘Japan as “Half-Civilized”: An Early Japanese Adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice and Japan’s Construction of Its National Image in the Late Nineteenth Century.’ Performing Shakespeare in Japan. Ed. Ryuta Minami, Ian Carruthers, and John Gillies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. 21–32.