Chapter 2

M: MIND YOUR DIGESTION

Anna

Anna, a fifty-year-old attorney from Boston, is a disciplined, analytical person. When she came to me, she’d done a lot of research on various diets in an effort to get a handle on the twenty pounds she couldn’t seem to shake, as well as the overall fatigue she felt was holding her back in her work and her life. (Some intermittent IBS symptoms didn’t help either.) Anna and I were discussing how to modify her eating plan when she got very anxious. I don’t think she even realized it, but every time I brought up a particular food, she would say, “I read that I should keep away from that kind of food for such-and-such reason.” She was my “keep-away” client. After about the fifth “keep-away,” I paused and said, “Anna, can I ask you, is there someone or something that you’re trying to keep away in your life?” Well, that turned into a very emotional session. So often it happens that emotional issues and anxiety get bound up in the effort to lose weight. We talked about her life as a whole—what made her happy, what didn’t. I encouraged Anna to work with a therapist who could support her and explore mind-body techniques to soothe her nervous system. I prescribed a sabbatical from surfing the Web for nutrition articles. Instead of her spending a precious hour of her day reading about the latest food or nutrient that might do her harm, we strategized about finding joy! Anna loved to dance but hadn’t in years, so she joined a Zumba dance class at her local gym and made some new friends. We worked on integrating meditation into her day, which helped her tremendously. As she began to unwind by degrees over the following months, she was able to integrate the diet changes that we were able to discuss in a more open, less fearful way. She finally lost the twenty pounds she’d wanted to shed for years.

It might strike you as odd that I’m beginning the first step of the MENDS program with a story that really isn’t about food. In fact, it’s about not thinking about food!

There is some amazing new science about how the microbiome directly influences the brain, including how the brain regulates appetite and digestion. In one study, eating yogurt, which is filled with probiotic bacteria, even changed the way the brain lights up on a brain-imaging study. But I want to begin this “Mind” chapter by addressing the ideas, and the emotions bound up in those ideas, that people commonly have about rebooting their diet and lifestyle to achieve and maintain healthy weight. Take Anna, for example. She couldn’t begin to deal with her weight and gut issues until she turned down the volume on the anxiety buzzing through her, much of it triggered by her relationship with food.

Of course, I’ve had clients who wanted to dive into the meal plans right away, what they couldn’t and could eat. And I can’t stop you from skipping to the next two chapters, “Eliminate” and “Nourish,” which are exactly about that. But I can tell you what often happened to my in-a-hurry clients. Everything goes great, for a while, and then the new-project shine wears off and old familiar emotional patterns reassert themselves. Emotions have real physiological consequences, namely, stress hormones orchestrated in the brain that have big effects in the gut and on weight loss. Like the song says, “Free your mind, and the rest will follow,” especially the gut!

The fears and anxieties that can accompany committing to a healthy weight-loss program are insidious because, more often than not, they lie half-buried in our psyche. They sap our confidence, our ability to see ourselves as strong people able to make lasting changes in our lives, and yet often we’re barely aware they’re there. But if we can bring these fears into the light of the day and examine them rationally, usually they’ll shrink in importance. You’ve probably heard some version of this “name it, own it” positive psychology before. It really does work.

Fear of Food

Anna is hardly the only client I’ve had who sabotaged herself by worrying too much about what she eats. The phenomenon has even been measured in research settings. In 2013, a group of New Zealand social scientists studied a group of three hundred people who were asked if eating a piece of chocolate cake would make them feel guilty or happy. Followed up eighteen months later, the minority who were guilty eaters had gained more weight than the majority who could allow themselves to enjoy a treat. Guilt, besides not being a lot of fun, is a setup for weight gain! In a similar vein, American researchers culled through questionnaires given to over five thousand people and identified seven distinct eating styles that were associated with overeating. One of the seven styles that women were far more prone to than men: Food Fretting.

I know, it sounds paradoxical. If you’re trying to lose weight, why wouldn’t the fear of food be a good thing? But it’s not. Instead of building up your resolve, ultimately you’ll undermine it. The anxiety about what you can and can’t eat and what the wrong foods might do to you creates a constant tension that can suck the joy out of life. It also increases levels of the stress hormone cortisol, which can increase the hunger for a sugar quick fix, which in turn increases insulin levels, which promotes fat storage. Your strongest ally in a lifelong sustained weight-loss program is the self-trust and self-confidence that comes from embracing life, not trying to keep it at arm’s length. Being able to take pleasure in food, and to share that pleasure with loved ones, should be a big part of that.

In Anna’s case, a Zumba class helped her to begin to be able to break down the fearfulness that was keeping her in her shell, trapped in a failed weight-loss program that amounted to an ever-expanding list of “thou shall nots.” I have another client, Rebecca, who suffers from gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD. She had become so fearful of food that she’d whittled her diet down to about six things she’d permit herself to eat. But she mentioned to me that once every few months, in the course of an afternoon of shopping, she would have lunch with her girlfriends and then, and only then, she wouldn’t suffer from gastric reflux, no matter what she ate. I wrote her a “prescription” on the spot: once a week, have lunch with at least one girlfriend and let go of what’s “good” or “bad” for you.

Fear of Giving Up Pleasure

A lot of my clients aren’t as good at self-denial as Anna is. In fact, they’re in love with the tempting pleasures of sugary, fatty processed foods. Life is tough enough. How, they wonder, are they going to get through it without the sweet release? This fear has a real basis. Social scientists, and any good student of human nature, know that willpower is limited and most people simply aren’t capable of denying themselves indefinitely what they truly yearn for, one major reason why ultra-low-calorie diets, whatever their short-term success, rarely pay off in sustained weight loss. The Swift Diet is about shifting what you want, not denying it. When you become familiar with the Swift Plan recipes and meal plans, built on fresh vegetables and fruits and not requiring much more prep time than the old processed foods, your taste buds won’t want to settle for a Luna Bar for lunch or a frozen entrée for dinner. Think back to when you were a child and the smile that crossed your face when you bit into a fresh peach in summertime. Commit to your sensory pleasure!

My friend Marc David, the founder of the Institute for the Psychology of Eating, tells a story about a client who lived on fast food. When Marc persuaded the client to slow down and concentrate on each Big Mac mouthful, he discovered that he actually disliked the taste and texture and changed his eating habits that day. (Yes, fast food is meant to be eaten fast.) Certainly the best-case scenario! Over the years, you may have conditioned your taste buds to respond to the lure of “hyper-palatable” processed foods. After a couple of weeks of not bombarding your taste buds with industrial concentrations of sugar, salt and fat, you’ll be able to taste real food. Will you always prefer the taste of a serving of grapes to that of a Mrs. Field’s chocolate-chip cookie? I can’t promise that. But if you do fall off the wagon, temporarily—we all do—the cookie likely will taste too sweet.

Fear of Hunger

Hunger is often the elephant in the room here, one big reason why many diets come to grief. In Chapter 3, I’ll go into detail about how you can counter physical hunger with a high-fiber diet. But hunger also has a strong emotional component. The fear of hunger is hardwired into us as a species. For most of our existence, humankind routinely experienced life-threatening (and all too often life-ending) periods of nutritional deprivation—game was scarce or the crops failed.

Today, in the developed world, the danger runs in the opposite direction. We can’t experience the slightest intimation of hunger without being overwhelmed by a tsunami of empty-calorie junk food or beverages. Heaven forbid we should be more than a five-minute drive or stroll from the neighborhood coffee shop (where caffeine is often combined with sugary syrups and fluffy mountains of whipped topping). As a consequence, many people who struggle with their weight have lost the ability to feel comfortable in that “sweet spot” between fullness and hunger. They become anxious that hunger could overtake them at any moment. I often encourage my clients to “ride the hunger wave” and explore what physical hunger feels like, how it has a different quality than emotional hunger or hunger born out of habit or maybe even fatigue. When you’re feeling hungry but your body doesn’t really need food, you might want to plug yourself in to an engaging activity or try one of the relaxation exercises I introduce later in this chapter.

Fear of Failure

Probably the most common fear that emerges in the first few sessions with a new client is the fear of failure. No matter how strong your motivation to get healthy and lose weight (and check in with that motivation often!), don’t be surprised to hear a voice in the back of your head whispering, “You couldn’t do it last time. What makes you think this time is going to be any different?”

You know what? Honor those past attempts! I encourage you to see them not as failures but as experiments that yielded valuable information about what worked and what didn’t, which you can put to use moving forward. The psychologist James Prochaska at the University of Rhode Island has devoted his academic career to understanding how we make major behavioral changes. He found that people who succeeded at changing the big things, like quitting smoking or drinking, went through early stages of “contemplation” and “preparation” before they were ready to make the big change. And they rarely got it right the first time. They sometimes even failed multiple times before they learned the necessary lessons and created the necessary momentum to succeed.

Consider the statistics that tell us that the majority of American women have tried to lose weight in their lives. If you’re reading this book, you probably have your own database of past experiences to draw on. So, change the narrative. Shift it from, “Why did I fail?” (i.e., “What’s wrong with me?”) to “What did I learn?” It’s time to shed that guilt that cloaks your weight-loss history.

Digesting with Your Brain

Let’s move from the level of conscious thought to the brain that gives rise to it. The brain and gut are so tightly wired together, scientists now sometimes refer to the gut as the body’s “second brain.” We all understand this intuitively. It’s embedded in the language—“butterflies in the stomach,” “gut feeling,” “going with your gut.” But when we understand something about the physiology of the “gut-brain axis” and how our behavior affects it, we can make simple changes that allow us to work with our digestion instead of fighting it, enhancing health and weight loss in the bargain.

Digestion actually begins in the head. We call the first phase of digestion “cephalic,” from the Greek, meaning “from the head.” It kicks in when we think about food or a tasty meal. The sheer anticipation stimulates the production of salivary enzymes in the mouth that begin to break down the carbohydrates in our food. The saliva itself is a lubricant that ensures a smooth trip down the short, muscular tube of the esophagus.

Here is the way the system works. The food moves down the esophagus into the stomach, a balloon-like muscular bag that breaks the food into much smaller particles, physically squeezing it and secreting enzymes and powerful gastric acids. The stomach then slowly pours the processed contents of the meal, now a liquid called chyme, which has the consistency of a smoothie, into the small intestine, where most of the work of digestion takes place. Assisted by the pancreas, which secretes digestive enzymes, and the gall bladder, which contributes bile, the small intestine breaks down the carbohydrates, proteins and fats in the chyme into their most basic components.

If the stomach resembles a factory, with its nonstop pulverizing and chemical baths, the small intestine is something closer to the undersea world of Jacques Cousteau, home to exotic-looking bulbous structures and beautiful in its own way. In the small intestine, some twenty-one feet of tubing is folded in on itself, but the surface area is much greater than even that suggests. Completely flattened out, it would cover a tennis court! That’s because the tissue itself is corrugated, formed into tiny fingerlike projections covered with tentacles called villi. The villi snatch food as it drifts by, in much the same way that coral feeds on floating plankton. The villi absorb the nutritional molecules into the intestinal wall, where they pass into the blood and lymph systems and from there to every cell in the body that needs them. What isn’t absorbed passes down into the colon in liquid form—the walls of the colon are like a giant sponge that sends most of the water back into the body. And in the colon, as we described in the first chapter, the undigested fiber is grabbed up by the bacteria who live there who ferment it into protective compounds called short-chain fatty acids. Finally, the waste products are sent packing, making the passage through the last piece of GI tract tubing, the sigmoid colon, before being pooped out of the body.

The “How” of Eating

While the digestive system might seem like its own self-contained world, the way we think about food and how we actually eat it set the tone for the entire enterprise. As we said, the anticipation of eating stimulates the enzymes in our saliva. But it also primes the digestive pump throughout the whole GI tract. The body actually secretes digestive enzymes and hydrochloric acid needed for proper digestion before you’ve swallowed a mouthful of food. If we eat without tuning in to our hunger or the pleasure we get from satisfying it—in other words, if the salivary enzymes aren’t flowing and we’re gulping instead of taking the time to chew thoroughly—the food won’t be sufficiently broken down at the beginning of the trip and it won’t be completely absorbed in the small intestine. Instead, it will become food for the bacteria that live there, leading to a condition you may have heard of called SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) and the digestive upset and inflammation it can cause. Whereas we want to feed the friendly bacteria in our colon—it’s one of the key nutritional messages of this book—we don’t want to overfeed the much smaller number that hang out in our small intestine. Likewise, if we overfeed the unfriendly bacteria in the colon with a poor diet, those now more populous bugs can travel back up into the small intestine, where they can cause more trouble.

Using the mind to eat in tune with your digestive system means remembering a few simple things about how to eat. Anticipate the meal to come. Chew slowly. No one has derived a scientifically valid formula here (there is such a thing as being too meticulous), but Dr. Klaus Bielefeldt, director of the Neurogastroenterology and Motility Center at the University of Pittsburgh, says about ten chews per bite is in the ballpark. Take moderate-size forkfuls of food—you know when you’re overloading—and put down the fork between bites. By slowing down the eating process moderately (you don’t have to wait so long that your food gets cold), you’re giving the body a chance to catch up. It takes about twenty to thirty minutes for stretch receptors in the stomach and hormones produced in the gut to signal the brain that the stomach has expanded and that the body’s need for energy has been met. The brain interprets this as “fullness,” or at least not being hungry anymore. If you gulp, you miss the memo and eat more than you need or really want. This brings with it a host of consequences, starting with too many calories, which drives weight gain, or, at a minimum, blocks weight loss. It also reduces the amount of empty space in the stomach that it needs to efficiently smash the food into smaller, easier-to-digest particles. Both too much food and too little space can contribute to less-than-optimal digestion and an irritable bowel!

The “When” of Eating

Over the past decade or so, a lot of nutritionists and doctors latched on to the idea that “grazing,” spreading five or six smaller meals over the course of the day, was a healthier and more weight-loss-friendly way to eat. The logic made sense—the smaller meals would keep blood sugar and insulin levels steadier—it just turned out not to be in sync with how the body wants to work. When we eat, the food doesn’t drop through the GI tract through force of gravity. It’s propelled down on waves of muscular contraction generated by the muscles of the gut wall. What scientists have more recently come to understand is that when we don’t eat, the body takes advantage of the fasting state to generate a similar wave of contraction to clear out any remaining food particles in the upper GI tract and send it down to the colon, where it can be processed and disposed of. The whole process takes about ninety minutes. The scientists call this gut self-cleaning feature the “migrating motor complex,” or in plain English, “the cleansing wave of the gut.” When the gut doesn’t get the necessary downtime between meals, once again, the risk is bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine and the gas, bloat and pain that often ensue.

I encourage my clients to observe a “sacred space” after a meal—some nutritionists prefer the more prosaic “rest and digest.” Does this translate into your mother’s or grandmother’s admonition to eat “three squares”? Pretty much, except that in today’s extended workday corporate culture, the time gap between lunch and dinner can grow well beyond the four-hour mark that usually spells hunger. A recent British survey of a thousand people who had resolved to watch their weight found that almost half had fallen off the wagon in the late afternoon, the average time of straying, 4:12 P.M.! So a healthy late-afternoon snack can be an excellent idea, a piece of fruit or modest-sized serving of nuts.

What’s important is that most of our days have a predictable rhythm that suits the innate clock that’s built into our physiology. Researchers now talk about “clock genes” distributed throughout the cells of our body that respond, for instance, to light and dark. (I’ll talk more about this in the final MENDS chapter, Chapter 6, “S: Sustaining Practices.”) Taking pleasure in meals at set times of the day is an important ritual that helps regulate that internal clock and gives the day its satisfying rhythm.

The Second Brain

From my brief description of the digestive tract, you now have some idea of how elaborate the system really is. Everything has to work just so. Hunger at the right time triggers the consumption of the right amount of food to be broken down by the right amount of digestive secretions. In fact, it’s such a big job that over time, we evolved a gut with a mind of its own, a “second brain” that handled the mechanics of digestion in concert with the brain in our heads, but below the level of conscious awareness . . . as long as everything works the way it should. When it doesn’t, we’re all too aware of nausea, indigestion, constipation, diarrhea and the rest.

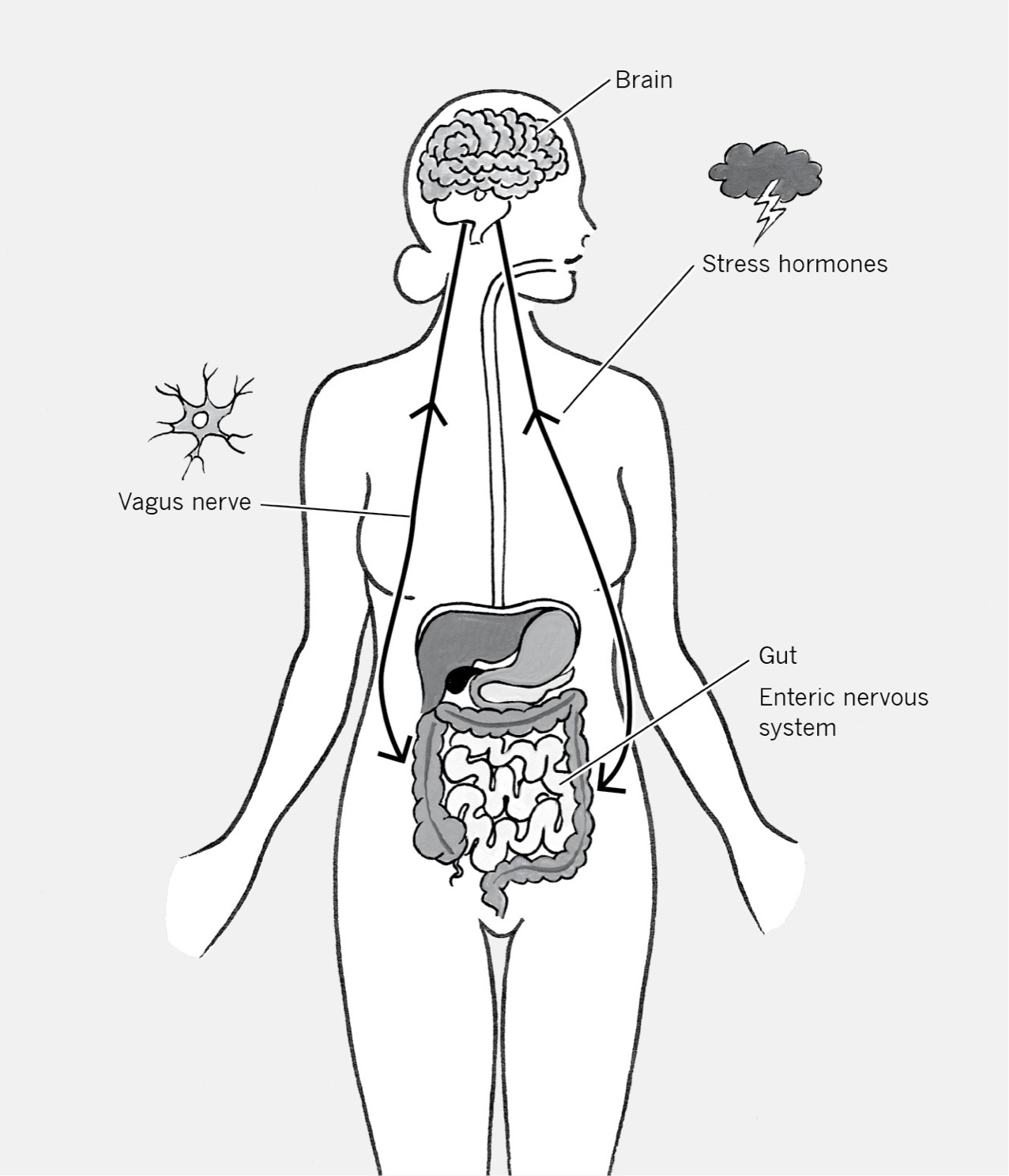

For the past thirty years or so, science has filled in the amazing details about the gut’s enteric nervous system, housed mostly in the small intestine. It contains as many neurons as the spinal cord and it produces all of the same chemicals as the brain—dopamine, GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), acetylcholine and 95 percent of the body’s supply of the feel-good neurotransmitter serotonin. The central highway that these chemicals travel, linking brain and gut, is the vagus nerve, which stretches from the base of the brain to the middle of the colon. The gut tells the brain how digestion is coming along—how full the stomach is, for example—and the brain responds accordingly, increasing or decreasing hunger. And the stress hormones that are orchestrated by the brain travel a similar path, which is why we can have those “gut-wrenching” experiences. The brain responds to threats or challenges in the outside world and the gut feels, well, a kick in the gut. In fact, stress often triggers digestive problems and it’s certainly a major contributor to unwanted weight gain. High cortisol levels pump up the body’s production of insulin and too much insulin directs the body to store calories as fat instead of burning them for energy.

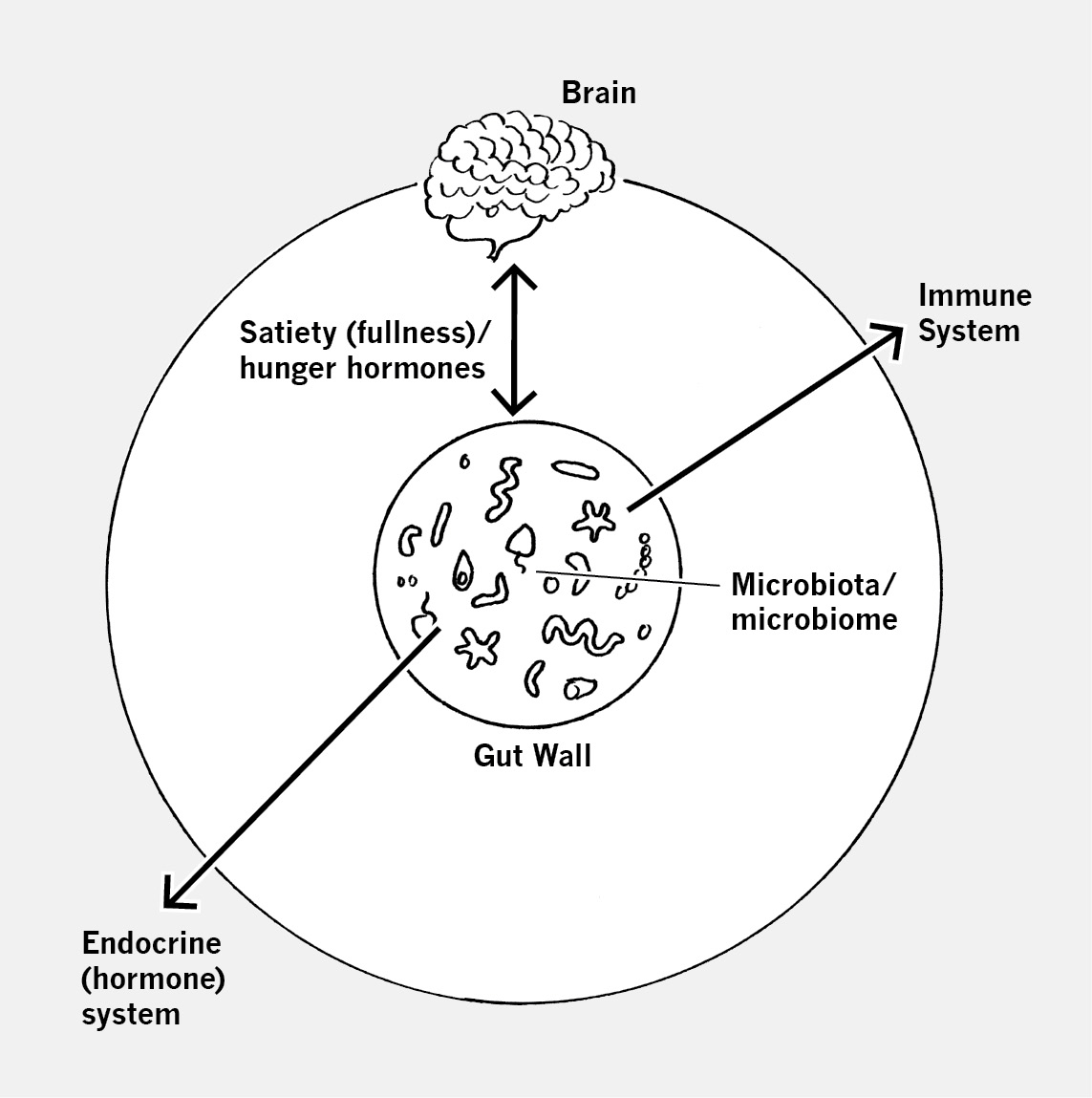

The microbiome revolution of the past few years has made it clear that the “gut-brain axis” is a two-way street. And the gut isn’t just sending progress reports on the mechanics of digestion. The gut bacteria are directly affecting how we think and feel, often about things that have nothing to do with digestion. Consider a mouse experiment done by a leading researcher, Stephen Collins, at Canada’s McMaster University. He transferred gut bacteria from a group of gregarious mice into a group of timid, fearful mice who, lo and behold, became much bolder. In another experiment, rat pups that had high levels of stress hormones after being separated from their mothers calmed down after being fed a probiotic bacteria commonly found in yogurt. Collins’s conclusion: the gut bacteria were “influencing behavior on a real-time basis.” Other studies have shown that these probiotic strains altered the rodents’ production of the neurotransmitter GABA in ways that mimic the effect of human antidepressant drugs. “These bacteria are, in effect, mind-altering microorganisms,” says Mark Lyte at Texas Tech University, another researcher in the field. Science is adding a whole new dimension to the old line, “You are what you eat.”

Yes, these are only animal studies. But these experiments provide us with clues to make sense of an extensive human research literature that shows that mental health and gut health are intimately connected. For instance, depression often shows up in people who first develop gut disorders. As UCLA researcher Kristin Tillisch put it, “Time and time again, we hear from patients that they never felt depressed or anxious until they started experiencing problems with their gut.” Last year, Dr. Tillisch published a proof-of-concept study that showed you could change the way a person’s brain worked by influencing the composition of the bacteria in the gut just slightly. Her study looked at eating a probiotic yogurt twice a day for four weeks. The women who ate the yogurt saw changes in the way their brains lit up on a functional magnetic resonance imaging scan (fMRI) compared to the women who did not. There were subtle differences in the way the brains processed sensory information and emotion.

On the weight front, Dr. Blaser at NYU has discovered that American kids, living in a relatively hygienic environment and regularly dosed with antibiotics, often lack a particular type of bacteria that humans have harbored in the stomach for millennia. This bacteria looks to keep in check the hormone ghrelin, which triggers the feeling of hunger in the brain. Lose the bacteria, it seems, and you lose a brake on appetite. How big a role this might play in the obesity epidemic of the past several decades, at this point, we can only guess.

Here’s what we do know about the “cross talk” between brain and microbiota. Stress hormones, controlled by the brain, can directly change how the bacteria in the gut affect the gut’s production of hormones and neurochemicals that speak to the brain, including the ones that affect appetite. And stress hormones, by changing the conditions inside the gut—for instance, the amount of mucus produced to line the gut wall—can favor certain bacterial strains over others, again affecting the chemical messengers that drive the enteric nervous system. The stress hormones may also increase the permeability of the gut wall, making it leakier and allowing fragments of bad bacteria to escape into the bloodstream, triggering a systemic inflammatory response. (As I described in the previous chapter, a processed-food diet that starves the good gut bacteria can do the same thing.) Or, in their guise as the immune system’s forward guard, the gut microbiota may respond to unfamiliar bacteria or a food irritant like gluten as an enemy invader. They may signal immune cells embedded in the gut to call out the troops, setting in motion a similar inflammatory response that can impact just about any organ system in the body, including the brain. Recall that depression and anxiety are common symptoms of gluten intolerance. Depression in turn saps people of the energy and the motivation they need to make smart food choices and to exercise, driving up weight gain and the likelihood of digestive problems.

The central highway joining brain to gut? It’s more of a beltway. The microbiome is directly linked to the immune system, the endocrine (hormone) system, the brain and its stress response, even the skin. Everything is connected!

Mindful Eating

That was a lot to digest, wasn’t it? I’ve noticed when I present some of this material at my digestive health workshops, the students may find the science interesting (some may not), but what they really get excited about are the techniques we teach them to lower their stress levels and increase their emotional resiliency. That is, after all, the most powerful way to get your brain and your gut back on good speaking terms.

I’ll go into some detail on mind-body exercises that cool down the stress response and focus awareness in Chapter 6. But let’s set the stage right now with this simple, everyday technique.

Now let’s consider this calm state of being in the context of your relationship with food.

Over the past decade, an entire therapeutic movement has grown up around “mindful eating,” complete with supporting organizations like the Center for Mind-Body Medicine (cmbm.org) and the Center for Mindful Eating (thecenterformindfuleating.org). It addresses the challenges of food cravings and “emotional eating” from a Buddhist-influenced perspective that emphasizes the importance of quieting the mind and being “in the moment.” (When you do the belly-breathing exercise, notice, if you really relax into it, that the usual internal mental chatter quiets down.) It makes so much sense! For a lot of women with weight and digestive issues, food comes to represent so much more than a tasty or a nutritious meal. It becomes a lot of things: a test of willpower, a reminder of past humiliations, a prompt for a host of sad or happy memories.

Think about my client Anna and all the anxieties that commonly attach to our effort to gain control over food. The mindfulness approach encourages you to focus your attention on the food in front of you, “peace in the present moment.” You learn with practice to nourish your body when there is physical hunger, not when your mind is craving some sort of emotional release. There’s a huge behavioral science literature that shows that people who are attuned to their body’s hunger signals are more successful at managing their weight than people whose eating habits are more influenced by external cues, whether that’s a TV advertisement or what their friend just ordered at a restaurant or some fixed idea about what they should or shouldn’t be doing to lose weight. For many of us, tuning in to our bodies and eating mindfully take practice. It is a practice.

Here’s the advice that neuroscientist Sandra Aamodt gave at a high-profile TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) conference last year: “Sit down to regular meals without distractions. Think about how your body feels when you start to eat and when you stop and let your hunger decide when you should be done.” Does that sound too simple? Dr. Aamodt says she struggled with weight and self-esteem issues her entire life. When she finally understood that food wasn’t a means to assert her self-worth, that it was food, nothing more, nothing less, the neurosis dropped away.

If people like Anna and Sandra Aamodt used to invest food with too much meaning, many of my clients don’t pay enough attention to it. They’re “mindless” eaters, snacking on whatever’s at hand over the course of the day. For people in both camps, the mindfulness prescription that focuses on the sensory experience of eating can reform counterproductive habits. In a pilot study done by researchers at the University of San Francisco, the obese women in a group of overweight women who trained in mindful eating and meditation for four months lowered their cortisol levels and maintained their body weight. Their counterparts who received no training had no change in their elevated cortisol levels and gained weight.

In my workshops, I might spend fifteen minutes getting my students to really taste a grape. First, they’ll just look at it and be aware of the saliva forming in their mouths, the initial wave of “cephalic” digestion. They’ll put it in their mouths and sit with it there for maybe a minute. One woman told me recently that she’d never before been aware of the texture of a grape skin. Then they’ll chew it slowly, becoming attuned to its specific grapey sweetness, even the sound of it in their mouths. At my last workshop, another woman said she found this simple exercise to be a “sensual experience.” They were really alive to the moment!

Obviously, this isn’t something you’re likely to do at home every day. But here’s a practice that you can do at any meal. It puts you in touch with slower eating, which is good for digestion and appetite control (those satiety hormones have time to kick in), and with the food itself.

The Emotional and Spiritual Wisdom of Weight Loss

As useful, even liberating, as the new microbiome science is, the weight-loss and digestive-health journey can’t just be boiled down to gut bacteria, satiety hormones and high-fiber foods. There’s a rich emotional and even spiritual dimension to this landscape. How could there not be? You’re breaking out of old habits and routines, testing yourself in new situations and, let’s be honest, risking failure. You’re confronting the idea of hunger and engaging anxieties and hopes about your physical appearance and your health.

I’ve worked with clients whose eating is fueled by loneliness, by stress, by boredom, by habit. This list is hardly exhaustive—I’m sure you can add a few more. But the common denominator is that these women were not feeling adequately nourished in some important aspect of their lives and they turned to food to make up the difference.

I have a client, Emma, a Harvard undergrad, with both digestive health and weight issues. She’d been obsessed with the extra fifteen pounds that she was carrying, and she got lost in self-blame and doubt. For her, something as simple as a “daily affirmation” has worked wonders. We were consulting on Skype and I said, “Emma, I want you to create a positive statement about all the changes you’ve made in your diet.” And she said to me, “Well, eating this way helps me to feel my best.” It gave me chills to hear her say that. I could hear that those simple words had such meaning for her. I told her, “Every time you go to a dark place or you get upset by a number on the scale, repeat those words: ‘Eating this way helps me to feel my best.’” We had created a daily affirmation for her, an easy way for her to call on her internal sources of self-calming and support. I am convinced that the weight came off in large part because of this reframing affirmation.

In the book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, which introduced so many Westerners to Zen, Shunryu Suzuki wrote, “The beginner’s mind is the mind of compassion.” That’s the mind that I’d like you to leave this first MENDS chapter with: bighearted and open-minded, without false optimism or self-defeating despair. False optimism is the currency of most diets and weight-loss books that push the idea that all you need to do to lose weight is to cut back calories for a while and to cycle through different foods on some kind of regimen; in other words, ignore the hunger and you’re home free. Despair enters the picture when this approach predictably fails, over and over again, and you convince yourself you must be lacking some essential quality required for success.

In our culture, women tend to be hard on themselves, often putting everyone else first and ignoring their own needs. There’s this pressure to be perfect. And perfect is the enemy of self-compassion, of self-forgiveness. That’s why I love the Eastern concept of practice. We don’t have to succeed at a practice; we just have to keep doing it, and if we do, we get better at it. Our resolve is not to be perfect on a diet. Instead, we commit to a practice of healthy eating and living that, even with the inevitable slipups, deepens and ripens with time. May MENDS be your guide to true nourishment.