When your clients and the contractors have agreed on a price, what contract do they use? Unlike my concerns about the AIA Standard Form of Agreement for architectural design services for houses, I do feel strongly that the AIA’s A105 Standard Form of Agreement Between Owner and Contractor for a Residential or Small Commercial Project is the best standard contract available for use by your clients. It clearly and consistently uses construction industry terms and language which you can explain to them during your review of the contract before they sign it. Your familiarity with the contract language should help them to understand it and feel confident they are using the right contract to do the work.

It has been our practice to tell the contractors what contract we want them to use and to have them prepare the actual document. We then review it thoroughly ourselves and ask for any revisions or clarifications before we review it with the owner. If the owner has specific questions about the contents of the contract or how the contract will be applied, we arrange a meeting between the owner and the contractors, with us present, to allow the two parties to discuss it and come to an understanding directly. Our experience has been that there is value in the owners having their questions answered by the contractors without us being intermediaries. The possibility that we could take a provision for granted that will be an important consideration to the owners is too great to not allow the two parties to communicate directly.

It is unavoidable that many of your clients or the selected contractor will have legal counsel who will want to review and modify the AIA’s A105 Standard Form of Agreement Between Owner and Contractor for a Residential or Small Commercial Project despite its being an industry standard. Many attorneys find the A105 to be unfairly biased toward either the owner or the contractor. Many will offer provisions and revisions to the agreement which you will have an opportunity to comment on, but it is important to remember you are not a party to the agreement and it is ultimately between the owner and contractor. You may disagree with the final form of the contract, but ultimately you may not be qualified to shape it beyond your experience and your opinions.

The contract will state the date of the contract and the two parties to the agreement, the owner and the contractor. You as the architect will be listed in the contract, and you will have duties and responsibilities outlined in the articles of the contract; but you are not a party to the contract. You are not doing the work or building the house or paying for it. In the contract the owner will be identified as the Owner and the contractor as the Contractor and the architect as the Architect, and the duties and responsibilities assigned to each will be stated that way.

The contract will be made up of various articles that enumerate all the provisions of the contract. Each of these articles, no matter what form of agreement is ultimately used, will generally be part of an agreement for the construction of a building. One way or another when you are reviewing any form of agreement, no matter who has generated it, you should make sure the articles provide and define each of these categories. If they are not all present and described in some form, then you need to advise your clients to make sure they will be part of the final agreement.

The contract documents are literally the documents that make up the contract. They typically include the contract itself, the drawings and specifications, addendums, and any other materials that should be incorporated, such as written instructions created before the signing of the contract.

Each of these items should be individually listed, including each drawing with its title and date. This date should be the issue of the drawing that reflects the final version of the house as you expect it to be built under the contract. If you have created a Revised for Construction set of drawings that includes revisions and changes as well as permit comments and value engineering, this set should reflect it and by agreement be the set used for construction of the house.

In addition to the drawings in their final form, the contract should list the specifications, also in their final revised form, with the appropriate date. Additionally you can add whatever you feel is pertinent to the contract such as the Instructions to Bidders, along with any addendums or other materials that were issued during or subsequent to pricing in the contract. The contract needs to enumerate and acknowledge the addendums.

As mentioned above, it is very useful to hold off identifying the final list of drawings to be incorporated into the contract until you have a set that reflects all the budgetary revisions and any permit comments. If you have revised the drawings after bidding and created a set of drawings to be Issued for Construction, these drawings with the dates associated with their issue should be listed in the contract and should supersede any drawings issued during the bidding and pricing process.

This list of materials needs to be carefully checked before the contract is signed by the owner. The owner will not fully understand the contents of the list of items referenced in the contract, and only you can make sure that it is complete and the dates on the drawings and other materials listed actually correspond to the materials you want referenced.

For one of our projects we had two sheets of exterior elevations omitted by the contractor in his list of the contract documents. While in this case we did not think this was intentional, it did create conflicts on the project regarding scope for certain parts of the exterior work. Fortunately a well-organized and thorough set of drawings indicates information in a coordinated manner in more than one place, and we were able to infer the scope from plans or sections. Not having all the documents listed in the contract can make your job harder, and this is why knowing and checking the full intended list of the contract documents are so important.

The contract will enumerate the project schedule. Construction contracts will typically list the schedule in terms of Date of Commencement and Substantial Completion. These dates will be stated as a number of calendar days for the construction of the project, known as the Contract Time. The Date of Commencement is usually the contract date, unless another date is selected.

During the project factors will intervene that will extend or expand the schedule (weather is a common one, change orders that alter the scope of the work are another). For practical reasons this may not always be discussed in a forthright manner that makes all the parties involved in the contract at the time of the signing fully understand the ramifications. During the project you cannot take for granted the contractor will fully communicate delays as they develop to the owner, and you need to try to keep yourself aware of time extensions, whether you approve of them or not. You need to keep the client and contractor aware there is potential slippage in the Contract Time, especially if the owner has housing arrangements that are dated to expire around the date of Substantial Completion as indicated in the contract. If they need to extend these housing arraignments, it is good to give them plenty of notice.

The Contract Sum is the total amount of the agreed upon price between the Owner and Contractor for the work described in the Contract Documents to build the house and any related construction (landscaping, swimming pool, etc.).

Depending on the contract format used, the main categories of the work and their values can be listed in the contract. These usually correspond to the categories utilized on the Bid Tabulation form.

Allowances are also listed in this part of the contract. Each should be listed with its value as specifically as possible.

The contract needs to list the agreed contract amount for the work to be done to build the house. If there are items that are open or undetermined at the time of the contract, these should be fully outlined and included in the contract. Open items of this nature pose real problems in the contract and should be avoided if at all possible. It is better that these items be addressed and priced as change orders once the project is underway; otherwise they are basically undefined allowances. Allowances themselves are discussed in Chap. 4, and all parties should have a full understanding of their scope before they are included in the contract.

The contract will define the insurance required to be purchased for the project by your contractor and owner. Each will have specific responsibilities for certain types of insurance. Typically the contractor will have a contractor’s general liability policy with a defined limit of liability consistent with the project value itself.

The owner will have property insurance to cover the owner’s property and the work being done under the contract. If the project suffers damage or loss due to fire or other insured hazard, the contractor will use the proceeds provided through the owner’s insurance policy to pay for the replacement work.

Make sure you or your firm are listed and covered in the contractor’s liability insurance. You and your staff will be present on-site when hazardous conditions exist and may be subject to injury or inadvertently damage some part of the work.

A policy endorsement from the contractor will be provided to the owner at the Date of Commencement. It is also valuable to familiarize yourself with the contractor’s actual liability policy as well as just a review of the certificate of insurance. After you have reviewed the contractor’s policy, it is important that you take time to review it with your clients.

Many contractors have a liability policy that gives the provider (the insurance company) the option of denial of a claim and, in lieu of it, paying for the contractor’s legal defense. This is particularly prevalent with contractors of modest means as it is a less expensive policy to buy and the insurance companies often know that if they deny a claim and the contractor has a small number of assets of little value, they can mitigate their own risk of having to pay. This is especially important for your client (the owner) as regards the contractor’s liability. If there is an accident on the jobsite that affects neighboring property and a claim is made, the contractor may not be able to pay for damages and recourse by the party suffering damages may be directed at your clients.

Much of the Contract for Construction will deal with the provisions of the contract—the enumeration of the various terms, tasks, parties, and responsibilities that comprise the project and the roles of those providing and supporting the building of the house. Some of these terms and definitions are straightforward and in common use; others are unique to the construction industry and relate specifically to the role each of the parties will play in the unique relationship that is formed to build one project.

The Contract for Construction of the project is the whole of the agreement for the work. It is a written document that alone describes in its contents, articles, and provisions the work to be done, the terms and conditions and the cost of the project. It includes all the pricing materials and their subsequent revisions to define the project the contractor will build.

The Work is everything required by the Contract Documents (which includes the Contract itself) to build the project. It refers not just to labor, but to the products and inputs (materials, equipment, assemblies) that are combined to build the house. Throughout the contract it will refer to the responsibilities and obligations of the contractor to build, manage, coordinate, and complete the Work.

The Owner is the person, persons, or entity paying for the work. For most single-family residential projects the Owner will be the person who will ultimately occupy the completed house, but in the contract it refers to the person who is executing the contract with the intent of building a structure.

The Owner has obligations under the contract in addition to paying for the work and providing certain insurance. The Owner provides surveys and legal descriptions for the site and pays for all fees that are not a part of the building permit. For legal reasons it is assumed the Owner owns or controls use of the site where the project is being built.

The Owner has a right to stop the work if it is being done incorrectly by the contractor, until the work is corrected. It will usually be you as the architect who will identify this incorrect work, called nonconforming work, and you will lead the process of identification of the problems and the required remedies. It doesn’t matter if the incorrect work is intentional or not, if it is nonconforming and the Owner doesn’t want to accept it, the owner has a right to have it corrected at no additional cost.

The Owner has the right to carry out work on the project with his or her own forces, and have contractors on-site for work done outside of the contract with the Contractor. The Contractor is usually required to allow the Owner’s forces access to the site and to coordinate the work with the Contractor’s own forces. We have outlined common examples of this kind of work above, and it is helpful to identify it for the contractor as early in the project as possible so it can be provided for in the project schedule and not affect the date of Substantial Completion.

In defining the Contractor in the contract, the role includes several responsibilities and activities beyond those assumed in the building of the project itself. For purposes of the Contract, the Contractor is the person, persons, or entity responsible for the building of the whole project as defined in the Contract Documents.

The Contractor will usually be asked to acknowledge by her or his execution of the Contract that the Contractor has visited the site and understands the conditions under which the project will be constructed. The intent is that by doing this the Contractor will have considered, when preparing the pricing, issues with site access, terrain, and distance from her or his base of operations for the project. Included in this, is an obligation to understand the requirements of the municipality having jurisdiction and the permitting authority. If the Contractor identified potential issues or problems with the site or permitting authority having jurisdiction during pricing efforts, it is assumed that the Contractor’s questions have been answered and addressed, possibly by an addendum, and are thus incorporated into the Contract Documents.

The Contract should also require the Contractor to examine the Contract Documents for errors and inconsistencies and to report these to the Architect for action. Conceptually the idea is that the Contractor, now a part of the project team, will see it as in his or her interest, and that of the Owner, to correct any errors before the project begins. In reality many of the potential errors in the Construction Documents will not be found until work has begun. It is helpful for these to be identified, and after the contract is signed, it is appropriate for you to ask the Contractor, in writing, whether he or she has made this check and to report any results. In a practical sense this is at best an effort to head off problems before construction begins. Since the activity takes place after the contract has been signed, any errors or omissions that create additional cost are subject to change orders. This is not a vehicle for you or the Owner to be able to avoid having additional cost associated with errors that arise later in the project.

The Contractor is now also obligated to create a schedule for construction for the Work and provide this to the Owner and Architect. This is intended to be a detailed breakdown of how the Contractor will complete the Work within the Contract Time. If, as we suggest, you had the Contractor provide a schedule at the time of bid submittal, then you should be seeing the same or a similar document at this time, with the addition of any increase in work scope due to permit or pricing revisions. This schedule should have been the Contractor’s basis for creating the Contract Time to begin with, and you can now have a formal tool for following it during construction. The intent for providing this schedule is for you and the Owner to be able to verify if the schedule is being met.

The Contractor is responsible for the direct supervision of the work of building the house. The Contractor is responsible for the activities required to build the house, typically known as means and methods. A significant part of the Contractor’s responsibility is the coordination of the various trades and suppliers who are building the project, and the Contractor will have full responsibility for this.

After the Contractor has selected the subcontractors and suppliers for the major parts of the work, it is common, perhaps even required, that a list of these subcontractors be provided to the Owner and Architect for review and approval. If you or the Owner have objections, you can voice them, but remember that if you tell the Contractor at this stage of the project you don’t want someone working on the project, the Contractor may not be able to identify another subcontractor for the same price and may come back with a change order for the additional cost of another subcontractor. A better way to ensure that you and your Owner don’t have this problem is to provide a list of approved subcontractors and suppliers to the Contractor before she or he prices or bids the project. Keep in mind that building a house is a complex activity, requiring many trained and capable people. No matter how carefully you try to qualify the people building the project, you are likely to be disappointed by the performance of some of them.

The Contractor is responsible for provision of all labor and materials utilized in the construction of the project. The contractor is responsible for selecting trades and subcontractors who are able to do the work and to schedule their work and evaluate their performance. One essential function of the Contractor is the selection of the people to build the project and the vendors to supply the materials and equipment. The Contractor then literally “contracts” with these subcontractors and suppliers and coordinates their work. When the work is in progress or completed, the Contractor then requests payment from the Owner, and after receiving the money pays these people for their work. It is for these activities that the Owner is paying the Contractor a fee and general conditions.

The Contractor has responsibility to warrant that the materials used in the construction of the project are new, free from defects, and in compliance with the Construction Documents. Unless salvaged or recovered building materials are specified, it is assumed all the material purchased for the construction of the house will be new. The quantities of materials required for the building of a house are such that they will usually be purchased through construction materials wholesalers who will deal exclusively in new materials, delivered to them directly from the manufacturers. This is a condition that is easy to observe during periodic site visits.

The Contractor has responsibility to pay all the taxes associated with the project. What is meant by this is that actually the Contractor has the responsibility to include the cost of sales and other taxes in his or her pricing and to pay them as a part of his or her responsibilities. Different places have different taxation requirements related to construction activities, and the Contractor will need to become familiar with these before submitting the pricing.

The Contractor pays for the building permit and related fees for inspections of the work during the construction process. It is traditional that the Contractor pay for this work as a part of her or his contract, but again, it will be a cost to the Owner, carried as part of the pricing or bid for the project.

The Contractor has the obligation to accomplish the work in compliance with laws and regulations having jurisdiction in the place where the Work is being built. The Contractor will usually be building the project within some type of incorporated area that will have requirements for obtaining a building permit, inspections, applicable building codes, and utility connection requirements and fees. Also there may be regulations regarding protection of existing trees, dumpsters and trash hauling, and stormwater retention and management. The Contractor will need to include compliance with these codes and regulations in the pricing and schedule.

The Contractor has the obligation to review and forward to the Architect for approval all shop drawings, submittals, product literature, product samples, and other materials that will be used in the construction of the project. These submittals are required for the Architect’s approval to accomplish the work but are not part of the Contract Documents. They play a critical role in making sure the design intent and products specified are provided for the project and are used in the manner you and the Owner intended. For a modest house there will be some items that will require your review and approval before they are purchased or contracted for by the Contractor. For a more complex house there may be significant numbers of submittals and shop drawings which will require a substantial effort on your part to receive, process, review, and mark up for approval before they are returned to the Contractor. The Contract requires the Contractor to review and mark up the submittals before they are forwarded to you for your review, and in theory they will already be marked for compliance with the intent of the Contract Documents. In reality many contractors content themselves with simply passing these on to the Architect and allow the review to take place there.

The Contractor’s use of the site is limited to the area where the Work is taking place. If the house is being constructed on a typical residential lot of modest size, then for practical reasons the whole site is usually part of the area in which the Contractor will be performing work. If the house is being constructed on a larger property, for instance, on a ranch or rural site, then the Contractor should have the construction activities limited to a specific area and the means to access this site where the house will be built.

The Contractor is responsible for cutting and patching the work. In construction, cutting and patching usually refers to two areas of activity on a project. The first is cutting into an existing condition, such as a wall or utility connection, in order to make modifications or to add on to them, then patching them to a “like new” condition. The means and methods of the “cutting” to accomplish the task or work are the responsibility of the Contractor. In a similar manner the patching of the cutting to an acceptable level of finish is also the responsibility of the Contractor. The second area of activity is the cutting and patching associated with nonconforming work. In the course of the project if you or the Owner identifies nonconforming work, you will ask the Contractor to fix or replace it. Removing the nonconforming work and putting it back in correctly fall into this category of the Contract.

The Contractor has the obligation to keep the site clean and to remove materials not used in the work at the end of the project. Proper and legal disposal of the construction waste is also a part of the Contractor’s work. Progressive cleaning of the jobsite is a task the Contractor has to plan and budget for in the price. A clean jobsite is typically a safer jobsite and one where the trades are more likely to take care to clean up and protect their work. If a house is being constructed in a residential neighborhood and loose trash is allowed to blow onto adjacent properties, often it can lead to citations or stop-work orders to the Contractor, especially if the neighboring property owners complain.

The Contractor has the obligation to indemnify the Owner, Architect, Consultants, their agents, and support staff from claims relating to death or injury or damage to tangible property on the jobsite or by the Contractor or those working for the contractor in the construction of the house. The intent is to limit liability for negligent acts and the results stemming from them, related to the construction of the house and the people or entities performing the Work to those who are contracted by the Contractor. This provision for indemnification is one that few architects fully understand or can explain, and it is best referred to the Owner’s insurance agent for the best language or policies to have in place to provide it.

The Contractor has the obligation for safety at the jobsite as it is related to all those working at the site and adjacent to it. Jobsites are traditionally dangerous places where many conditions exist that can potentially cause harm to those present on-site or nearby. Safety can mean different things to different contractors, but at a minimum it will mean having protections in place to secure the work within an enclosure to prevent access when work is not taking place and railings and other protections to minimize the risk of falling from upper levels.

The Architect as described in the Contract for Construction has a set of tasks and responsibilities but is not a party to the contract itself. The design and artistic component of our skill set, so important in the design of the house, is not literally called upon during this phase of the process. During construction of the Work our administrative and problem-solving skills are what we are asked to bring to the project. The Architect has the responsibility to administer the contract between the Owner and Contractor, to periodically visit the site and monitor progress, to review submittals, and pay applications and various other roles having to do with design intent and expectations. In my experience the role is much broader than described in the typical contract. By nature our clients expect a great deal more from us than the contract suggests our role to be, but to meet our obligations to the Contractor and Owner for smooth execution of the project, the role is as described in the provisions below.

The Architect has the role of administration of the project as defined in the Contract Documents. The Contract for Construction pointedly does not use the words supervise or supervises, for that is the role of the Contractor. The Architect’s role in administration can be best characterized as a series of activities that facilitate the Contractor’s being able to move the work forward with as little interaction with the Owner as necessary. First, the Architect assists in the purchase and contracting for the work through approvals of submittals and shop drawings. Second, the Architect facilitates payments for the work by approving pay applications and reviewing these with the Owner. The Architect monitors progress on-site for quality and adherence to schedule by making periodic visits to the site and reporting on concerns or nonconforming work. Finally, the Architect views the work for adherence to the design intent and has the final word on artistic interpretation. These activities support the Owner in his or her relations with the Contractor and also illustrate the duality to serve each of these two primary parties to the contract in a fair and impartial manner.

The Architect will visit the site at appropriate intervals to view the progress of construction and the quality of the work. The Contract does not define when or how often the Architect makes these visits, but if you are reviewing pay applications on a monthly basis, you would have to go at least once a month to be able to verify that the work has been competed to the level you are being asked to certify.

The Architect does not control means or methods of construction. As described above, this is solely the responsibility of the Contractor.

The Architect will certify the applications for payment. At regular intervals the Contractor will provide Applications for Payment. As the architect, you will review and approve these for payment. Many of your clients will have interim financing through a bank or other financial institution that will require your specific certification as a condition of release of funds. The Contract will state how quickly after receipt of the Application for Payment the Contractor is to be paid, and you will need to review and approve the application within the time frame stated.

The Architect may reject work that is not in conformance with the Contract Documents. It is this provision more than any other that allows you to intervene in the construction process and affect the quality of the work. To monitor quality and identify nonconforming work will require visits to the site more often than just the times required to verify the application for payment. Implied by this provision, but never stated is your responsibility to reject the work before it affects other trades, magnifying the cost ramifications of the corrections.

The Architect will review the Contractor’s submittals for compliance with the intent of the Contract Documents. The Contract will state that you will do this promptly in order to keep the work progressing smoothly. As noted above, properly executed submittals and shop drawings require substantial time to review and approve and, if necessary, return for resubmittal. Their careful review and consideration has a direct bearing on the successful execution of your design because they clarify to the Contractor and the subcontractors what your expectations are for the provision and installation of the work.

The Architect will evaluate performance under the contract. Usually this will be in the form of a written request from either the Owner or the Contractor and will be the result of a specific concern regarding quality or schedule, potentially affecting which of the parties to the contract will have responsibility for cost. This provision seems innocent enough in its bland wording in the Contract, but it is where your impartiality in administering the contract can put you at odds with your client who has been paying for your services.

The Architect will make determinations of performance that are reasonably inferable from the Contract Documents. The basis for your evaluations of performance is to be the Contract Documents. It is implied that if you make your evaluations using this criterion, they should be clearly understood by each party to the contract and you will not be liable for the results. The unfortunate challenge presented by this evaluation is discussed in the paragraph above, making a decision that may disappoint your client.

The Architect’s duties and responsibilities may not be changed without written consent of the Owner, Contractor, and the Architect. You have to be careful when taking on a role that includes duties not outlined in the Contract. This provision allows for that possibility, but only with the written approval of all the parties to the Contract. You will have to evaluate and decide on the advantages to you or the project for you to take on more duties than those in the standard form of agreement.

The Contract allows the Owner to make changes to project as described in the Contract Documents by making additions or deletions to the work. The Contractor is then allowed to adjust the Contract Sum and the Contract Time. For a variety of reasons there will be changes to the project during construction, and it is important the Owner clearly understand that these may have an impact on the cost and schedule. Additionally these changes will be priced by subcontractors and vendors who are already under contract and for obvious reasons have no incentive to provide the lowest possible prices. This can delay acceptance of changes by the Owner, and for practical reasons decisions to make changes to the project should only be undertaken with the full ramifications of their impact on the budget and schedule agreed to in principle by the Owner before they are addressed to the Contractor.

The Architect can make minor changes to the work that will not affect price. On some occasions these are relatively minor and help to clarify or simplify the project. As with all changes to the work, they should be made judiciously and with a clear belief in their necessity.

Concealed or hidden conditions on the site that could not reasonably be expected to be present or accounted for in the pricing will require a change to the scope of work and the Contract Sum and Contract Time. When conditions like this occur the Owner will usually rely on you to decide what is reasonable and fair. When building a new, ground up project on a cleared site, these kinds of discoveries will be limited to subsurface conditions not shown on a survey or found in a soil boring, usually during excavation. If the project involves additions or demolition to an existing building you are highly likely to find concealed conditions that you will have to accommodate in your design or pay the contractor to relocate. In either example these can affect the Contract Sum and the Contract Time.

The actual Contract Time, the time agreed to for the total construction of the Work for each project, is defined within the Contract for Construction, and adherence to this allotted number of days is an obligation for the Contractor. The Contract will state that the Contractor literally has an allotted number of days to build the project, and all activities will be scheduled within the time. While time is of the essence in the construction of a house, in reality there are many reasons that the Contract Time will be extended. Possible reasons include changes to the scope of work, concealed or hidden conditions, unexpected and unforeseen delays in obtaining building material or equipment. In all cases it can be agreed by reasonable people that the time to build the project needs to be extended. Unfortunately during construction, with the associated pressures and stresses, not everyone acts in a reasonable manner, and you as the Architect have to exert your leadership to help the parties to the Contract come to consensus and agree to extend the Contract Time.

Contract Time also becomes a benchmark around which others are making plans and scheduling activities in addition to the Contractor. For example, the Owner may be arranging temporary housing for the duration of construction or setting up work to be done at the house as it nears completion, for instance, low-voltage subcontractor work or landscaping. If the schedule is slipping, for whatever reason, the Architect may be the one to state this formally to all the parties, however obvious it appears to the Owner, so they can adjust other contingent scheduling.

One administrative role the Architect has is to maintain an understanding and awareness of the progress of the project within the Contract Time. The Owner will probably rely on your experience to evaluate whether the project is on schedule and moving forward to completion in a responsible manner. The Architect will also want to make sure that as the Applications for Payment are reviewed and approved, the available General Conditions and fees are adequate to complete the project, even if the schedule elongates and there are no change orders for additional time. In a practical sense you will have to monitor the amount of work left to do each month against the schedule and from time to time review the project status with the Contractor to make sure you can help keep everyone informed as to whether the project will be completed within the Contract Time.

The Contract will state the payment terms for the project, usually the date each month the payment is to be made and the number of days the Architect will have to review the Application for Payment prior to that date. As part of the Contract for Construction, the Owner is literally agreeing to pay the Contractor within a certain number of days after the Contractor makes the Application for Payment available to the Architect. As the architect, you will be approving the Applications for Payment so these terms need to seem reasonable and workable for you and your ability to process them. If you can get 10 days and this is acceptable to the Contractor and Owner, ask for it. Be careful about agreeing to a quick turnaround of the applications; if you cannot always review them in the time allotted, don’t agree to accept the time frame. Your timely approval of these documents can affect the ability of the Contractor to do the work through obligations the Contractor has to pay subcontractors or suppliers and can become a possible issue in schedule delays later in the project. Ensure that your client will be able to access funds to make payments after your approval in the time outlined in the pay application. Depending on the Owner’s agreement with the bank or financial institution, there may be a time period for processing the application that cannot be reasonably met as outlined in the contract.

The contract will allow the Contractor to submit an application for payment by a certain date each month, usually 10 days before the payment is due. This allows you a reasonable amount to time to review each payment application and to make a site visit if necessary to verify that the work for which payment has been requested is completed. The Architect is not required to make an exhaustive survey of the work to determine if the value of the amounts requested is correct; but if you have questions and feel you need further backup to the amounts in the application, you will need to give the Contractor reasonable time to provide it. Having several days for the review allows you some flexibility and time for careful consideration before approval.

The Application for Payment should have a component that links the amount of the payment to specific values for the various categories of work. This is usually an attached form to the Application for Payment called a Schedule of Values. In most cases this will be a format similar to that provided on the Bid Tabulation form and is loosely organized around similar work scopes. For example, if the application requests payment for work in the category of concrete, it will be expressed as a percentage of work completed in the category and you will be able to evaluate whether the payment is justified by comparing it to the completed work versus the work to be done. This reasoning is applied across all categories.

In the case of a Contract for Construction where the terms are for a cost plus a fee (cost plus contract), typically the Contractor will submit all the receipts and invoices for the work done during the time period covered by the application with the appropriate markup as agreed to in the Contract. This documentation will provide the backup for you to use in your approval of the application.

If the Owner is willing to approve payment to be made for deposits or work to be stored off-site, the Contractor can ask for this in the application for payment. It may require additional documentation that indicates the value of this work, where it is stored, and perhaps insurance on the work itself. Payment for Deposits or for Stored Materials is common in residential construction, and for practical reasons the Contract needs to reflect this and support it with any conditions that assure the Owner and the Owner’s financial institution the payments are for work that is owned free and without encumbrances after payments are made.

After the Owner makes a payment, the Contractor is required to expend the funds for the work approved and by this to be able to warrant that the work paid for is now free of any financial obligations to the Owner. This is often supported by a release of lien or partial release of lien, provided by the subcontractor or suppliers to acknowledge receipt of payment. It is a common practice to require that with the Application for Payment the Contractor provide a partial release of lien for the items requested for payment the previous month. It is worthwhile to review these releases to make sure they correspond to the work you approved payment for previously. It can also be helpful to tally them to see how closely the amounts of payments they describe match the amounts expended.

After a review of the Application for Payment, if the Architect believes it to be complete and accurate, the Architect can sign it, making it now a Certification for Payment, and forward it to the Owner, with a copy to the Contractor. If, when reviewing the Application for Payment, the Architect feels there are inaccuracies in the amounts of work completed, the Architect can make adjustments to the amounts believed to be incorrect. The Architect can then revise the Application as appropriate before signing it, thereby certifying it for payment. The Architect will need to state in writing the reason for revising the payment amounts when he or she certifies it and will forward it to the Owner and Contractor. For practical reasons it is probably best to discuss these perceived inaccuracies with the Contractor beforehand to afford the Contractor the opportunity either to provide further clarification or backup or to revise the application to reflect the Architect’s concerns. It is not useful to the overall process of construction to have an Application for Payment that has been unilaterally revised by the Architect and indicates discrepancies or disagreements. It is worthwhile to agree in advance with the Contractor on any problems and, if necessary, to agree to a revised Application for Payment. Again with reasonable people this should be a straightforward and logical discussion.

It is customary when making progress payments on construction projects to hold some portion of the payment back from the Contractor in the form of a retained sum to be paid at the successful completion of the project. This retained sum, commonly called retainage in the construction industry, is identified as a percentage held back from each progress payment period and is identified in the Application for Payment. Usually this amount is 10 percent, but it can vary with some projects or doesn’t exist at all in others. We like the practice and have found that the contractors we work with who understand and are comfortable with retainage usually understand the entire payment process as defined in the contract. Contractors who are unwilling to have retainage withheld from their payment amounts usually signal a red flag to us, and we require a more thorough understanding of their concerns before we would want our clients to sign a contract with them.

The most consistent reason offered by contractors who oppose the practice of holding retainage from their payments is that they are “small contractors” or that they use “small subcontractors” who cannot afford to have their money held back. This reason poses a number of problems for the architect when advising a client on whether to agree to a contract with this contractor.

First, we want to understand which subcontractors specifically have this problem and why. When we press the contractors, we find that they often have never discussed this requirement with their subcontractors or suppliers; it is more often their own concern, perhaps linked to legitimate cash flow issues related to how they plan to pay for the work. Our experience shows that not all categories of the work need to be subject to retainage, that it is possible to make payments for several of the subcontractors to 100 percent when they are complete with their scope, for example, a foundation contractor who has a lot of work in the first few months of the project and then none until near the end when pouring the flatwork. Paying them their retainage at the time the foundation scope is complete seems reasonable. With a small amount of planning this process can be applied to most of the subcontractors and vendors associated with the project.

Second, we think it is reasonable to be worried about contractors who say they have never had to enter into an agreement that requires retainage. It suggests a lack of experience working with an architect within a typical construction agreement. This situation needs to be understood in detail and is another item to be reviewed in checking references. Contractors who traditionally work directly for owners and are used to structuring the payment terms favorably to their manner of working may have trouble having another professional evaluating quality and progress advising the owners. We have often been successful with some of these types of relationships, but they do take an effort at the front end of the project to establish a working process for all aspects of the job, not just the payment terms.

Third, we begin to question the financial stability or resources of a contractor who is adamantly opposed to this practice. The idea behind retainage is an incentive for the contractor (and the subcontractors) to complete the work within schedule at a high level of quality. The payment of the retainage at the successful completion of the project, after all punch list items have been done, is an incentive to conscientious management. If contractors are doing their job in a professional manner, using subcontractors and suppliers who likewise are oriented to expediency and quality, retainage should present no problems. For residential construction the level of financial stability and professionalism is often different from that found in the commercial world. It does not necessarily mean the contractor is not capable or qualified to do the project; it just means that the contractor’s resources may be limited to the flow of funds from the owner. Both you and the owner will need to understand and perhaps adjust your oversight to accommodate this.

An important final comment on this item is that if you agree not to require the contractor to include retainage in your contract, then you must be much more diligent in verifying the amounts in the schedule of values as you approve payment applications because you can literally take a category down to zero in the course of construction, well before substantial completion or occupancy.

Substantial completion is a construction industry term for the project completed enough for the owner to occupy it and use it in the manner for which it was intended. This does not mean the work is 100 percent complete or that all the punch list items are completed; simply said, it is the end of Contract Time, and the Contractor has met her or his obligations regarding completion. It does not mean the Contractor has accomplished this within the original Contract Time agreement; there may still be issues to resolve regarding additional time beyond the scheduled completion date, but from the date of Substantial Completion the Owner now has use and access to the Work.

The Contractor will indicate that the project is Substantially Complete, and the Architect will make an inspection to determine whether this is true. After the inspection, if the Architect agrees, the Contractor will prepare a Certificate of Substantial Completion, establishing the date, and from this point forward Contract Time stops and warranties begin.

Commonly at the time of Substantial Completion the Architect will also create a punch list, which will establish the work still to be completed by the Contractor and a time frame in which it is to be done. In an ideal world this list is attached to the Certificate of Substantial Completion; but if not, it will follow as soon afterward as possible.

When the Contractor has completed the outstanding work associated with the Certificate of Substantial Completion, he or she will issue to the Architect an application for final payment. The Architect will then make an inspection of the project to determine whether the work is actually completed. If it is complete, the Architect will sign the Application for Payment, thus turning it into a Certificate for Payment which would bring the project to 100 percent of the contract amount (unless there were open items that are agreed to in writing).

Before the final payment is issued by the Owner, the Contractor will issue to the Architect all final waivers of lien, receipts, certifications, or other materials establishing that there are no claims for payment for any of the items related to the Work. When the Contractor accepts this final payment, it warrants there are no outstanding financial obligations of the Owner toward any of the subcontractors or suppliers with regard to the Work.

Unfortunately this tidy set of guidelines never works out this easily. Often completion of the punch list is a slow process. Getting all the loose ends wrapped up in a satisfactory manner can take a significant effort, exacerbated by the inevitable “project fatigue” common near the end of many projects. Many of the subcontractors and suppliers will have moved on to other projects, and making the final work a priority is often very hard. It is in this phase of the project that the real coercive power of the retainage can best be brought to bear on the Contractor, for the Contractor will understand you will not be releasing the funds without the punchlist being complete. Further, many Contractors cannot make final payments to their subcontractors and suppliers until after they receive the final payment, creating a potential set of difficulties in obtaining the final waivers and certifications. Often this can be facilitated by a series of joint checks, given to the remaining subcontractors and suppliers seeking payment at the same time as they issue their lien releases.

For a variety of reasons the location of the project is the best place to designate as the governing law. The house will be located in a specific jurisdiction, with laws and codes related to that place, and all the Contractor’s work will have taken place there. It is a logical choice and one where the Owner’s rights and protections are probably best vested.

It is typical to provide the Contract with provisions for both the Owner and the Contractor to terminate the Contract under certain circumstances. In almost every case, either party resorting to termination is a difficult and expensive situation for the project and should be avoided at all costs. Despite the outcomes, on occasion it will be necessary for one of the parties to terminate the agreement, and these provisions guide the process.

The Contractor can terminate the contract if she or he is not paid within a certain time (usually 30 days) and with a subsequent written notice. Since the payment terms are a part of the Contract and the Owner is obligated to make the payments following its guidelines, the usual reason for failure to pay the Contractor in a timely manner is either default by the Owner or nonperformance by the Contractor, which creates conditions whereby the Architect cannot approve an Application for Payment. Neither of these scenarios is in the best interest of the project, and as the Architect, you will be in the forefront of helping to deal with each. Other than for nonpayment, the Contractor cannot terminate the Contract.

The Owner may terminate the Contractor for a variety of reasons, all which have to do with the execution of the work and adherence to the schedule. In general, these areas of the contract concern properly staffing the project with a qualified and capable workforce, the following of laws and ordinances related to the building code in the jurisdiction, and the payment of the subcontractors and suppliers. Observation of the project for both schedule compliance and quality of the work will make it obvious that the Contractor is not performing up to his or her obligations. If the Owner decides that the Contractor needs to be terminated, the Architect has the role of consulting on the action. This means you will be advising what parts of the Contract are not being upheld as the grounds for the Owner’s termination of the Contractor.

The Owner who decides to move forward with a termination will need to provide written notice and, after a designated time period, take over operations on-site to complete the project. In this case unless the contract provides for compensation to the terminated Contractor, the Contractor will not be entitled to any compensation for unpaid general conditions or fees at the time of termination.

The Owner also has the right to terminate the Contractor for convenience, most often due to financial restrictions or setbacks the Owner encounters. In this case the Contractor is due all the payments for the work done to date as well as costs to shut down the project and reasonable general conditions and fees that are outstanding.

All the provisions and articles of the Contract for Construction are meant to facilitate a successful and positive relationship between the parties. In an ideal world these are guidelines by which each of the parties performs his or her duties and work in common to complete the project. Equally if things go wrong, it is intended to provide remedies and solutions to get the project back on track or terminate the relationship between the parties. In reality, if the working relationship between Owner and Contractor breaks down and cannot be repaired or guided to compromise, the contract’s provisions are open to interpretations and enforcement in unreasonable and difficult ways that often fall to the Architect and your project documentation to describe the nature of the problems and the responsibilities for them.

Even though you are not a party to the Contract, your administrative role requires you to take an active part in the construction process. Keeping good records of the construction activities and maintaining an even-handed approach to the problems as they arise are critical to your duties. Your experience and knowledge in helping the Contractor and Owner honor the contract provisions is integral to the successful completion of the project. If the Owner looks to you to help with the selection and review of the Contract for Construction (which the Owner almost certainly will), make sure you are comfortable with the terms and conditions and fully willing to accept each and its possible ramifications in your administration of the project. If your experience suggests that you are not comfortable with any of the conditions, use that experience to have them modified or excluded from the contract.

Fred and Gail Hackney are wonderful examples of ideal architectural clients for residential design. Both are doctors, and both understand professionalism and the value of going to experts for solutions to problems. Additionally they were smart, had good aesthetic sense, and were open to the exploration of new ideas within an aesthetic tradition loosely defined as traditional. I was referred to them by a contractor who bid one of our projects but was not successful in being awarded the project. Impressed by the quality and thoroughness of the documentation our firm produced, he suggested us to the Hackneys, who called and made an appointment for an interview. This is a reminder that you never really know when you might meet a potential client or someone who might be able to refer you, so you always have to do your best and be at your most professional. The Hackneys’ existing house was a pleasant, but nondescript traditional home in an older, established neighborhood in Dallas, with wonderful trees and mature plantings. Touring their house, I was at first disappointed by the traditional nature of their art and furniture, concerned that they did not meet the profile of my typical clients who were more interested in contemporary design. But at the same time I was impressed by the clear sense of order in their house and by how well organized they were for our first meeting, having a list of requirements for the new house clearly defined and ready to review with me.

Our firm came to a business agreement with the Hackneys, fully aware that the house we would be doing would have traditional qualities, but we were resolved to do it carefully and well, which the Hackneys fully supported. I had been doing a lot of soul searching, wondering if our dependence on clients with a contemporary leaning had actually excluded us from working with interesting people; if we were missing opportunities to build things of quality we could be proud of. In part we were eager to take this project to see if our approach to our design projects could yield a successful traditional house.

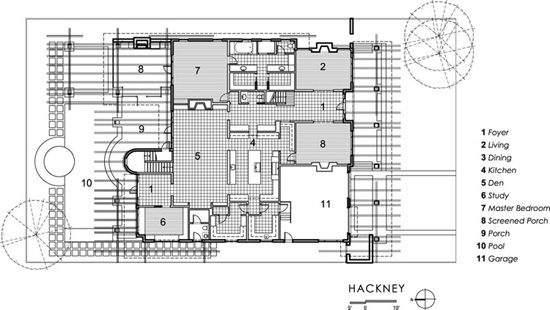

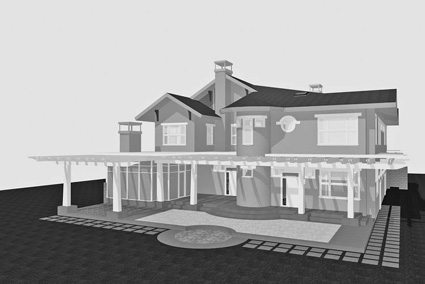

As we created the plan diagram for the house, I did a thorough review of historical design styles that I thought might work for their house, based on their lifestyle, and settled on the idea of suggesting that they go in the direction of an Arts and Crafts–Style house in spirit, planning, and details. It seemed to be a style that was traditional enough to be appropriate with their furniture and accessories, but that also would allow for open, flexible spaces that transitioned easily to the exterior. Our design contemplated significant planning for porches, terraces, and other outdoor living spaces. Initially the Hackneys were puzzled by why I thought this style would be appropriate for their home, but I loaned them a number of books on the subject of Arts and Crafts Architecture. By reviewing these they were able to get an understanding of the possibilities for planning successful domestic spaces. Additionally, examples of older arts and crafts houses in nearby neighborhoods allowed them to go and see firsthand built illustrations of the style. In part because of their trust in me, they looked at the examples and came to understand the potential richness and warmth that could be achieved by planning the house using these design concepts (Fig. 5.1).

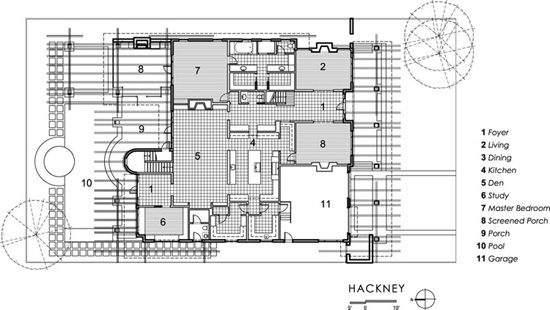

The house squarely faces the street in alignment with other houses on the block and is defined by an open porch running the length of the front. This porch is large enough for meaningful furnishing for sitting, swinging, and enjoying watching (and participating in) life on the street (Fig. 5.2). A continuous cascade of steps leads up to the porches, forming a gentle transition from the front lawn. The entry is into a large stair hall that is open through two stories and whose central feature, an architectural stair, provides a vertical connection to the four upper-level bedrooms. Opening off the entry are identically sized formal dining and living rooms, each with an identical fireplace. The stair hall terminates in the great room with large windows and French doors opening to the rear porch, which is similar in scale to the front porch. Opening directly into the great room is the large kitchen with large supporting pantry and utility room.

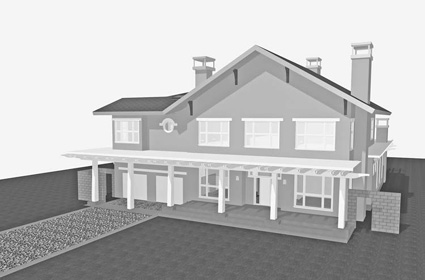

A study off the great room has exterior access and windows on two sides. Its location gives the Hackneys a place to work while still being in earshot of the great room, which can be sealed off acoustically by a large sliding panel. Since most of the living rooms in the house are designed for entertaining, and therefore for large numbers of people, the study allows enough room for two armchairs and ottomans, functioning as an intimate living space. A built-in desk faces large windows which open to the rear yard and swimming pool, providing visual oversight of children in the back yard (Fig. 5.3).

FIGURE 5.1 Hackney house plan. (Drawing by Zachary Martin-Schoch.)

FIGURE 5.2 BIM view of the front of the Hackney house. Note the large front porch and cascade of steps leading to the entry.

The master suite with large bathroom and his and hers closets is also on the ground floor, a common requirement from our clients for the houses our firm designs. This suite also has an exterior wall of French doors that open to a screened porch. With this porch providing enclosure from insects, the doors of the bedroom can be opened fully to accept a breeze, allowing fresh air into the house. The screened porch shares the same heavy timber detailing as the front porch, but instead of open space between the columns it is in-filled with screened panels in complementary wooden frames.

The upper level is composed of four large bedrooms, each with its own bath and walk-in closet. These bedrooms are accessed through a large central playroom with adjacent wet bar. It was the Hackneys’ intention that the upper level be the semiautonomous domain of their two daughters and their friends who were visiting, so it has all the amenities of the “adult” living spaces downstairs.

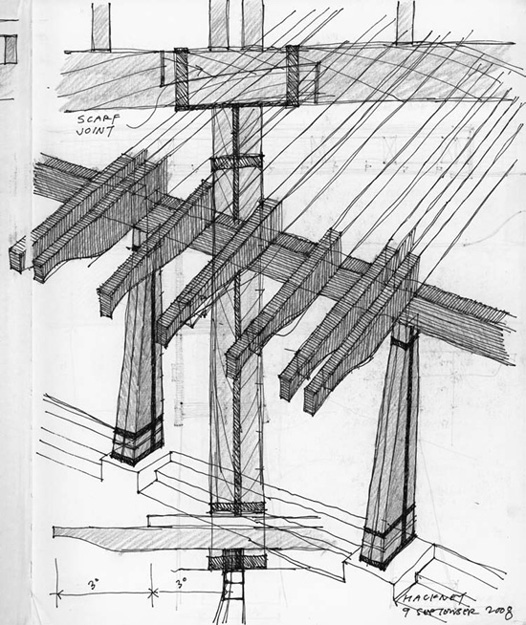

The exterior is stucco, the windows are white, and the extensive timber framing of the porches is the main exterior decoration for the house and the strongest defining element. Windows have divided lights and are very large, allowing the maximum amount of light to enter the house. As noted, the lot had several mature trees that shade the exterior, and their shadow patterns form one of the primary decorative elements of the design of the house. The white stucco background allows for the play of light and shade, accentuated by the horizontal line of the porches.

FIGURE 5.3 BIM view of the rear of the Hackney house showing the continuous porch off the den and access to the pool. (BIM by Alesha Niedziela and Zachary Martin-Schoch.)

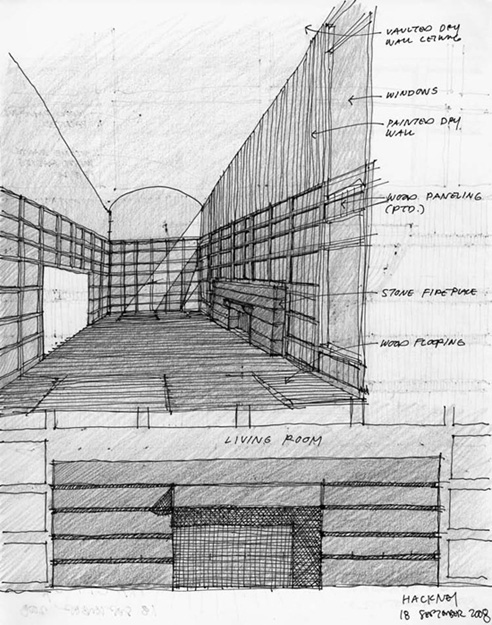

The unifying element on the interior of the house is the white-painted wood paneling that fills the entry stair hall, living room, and dining room and is echoed in the cabinets in the kitchen and study. Designed as a rectangular grid with a horizontal pattern, it runs throughout the ground floor and unifies the spaces as a sort of superscale wainscot (Fig. 5.4).

The living and dining rooms have shallow curved vaulted ceilings, unique to these two “formal” spaces and allowing them to be places set apart from the otherwise open plan and flowing spaces of the rest of the house. Each of these rooms is accessed from portals in the entry stair and can be viewed by guests as they move into the less formal great room. The living and dining rooms are thus part of the procession into and through the house, even if they are not entered (Fig. 5.5).

Most of the lighting in the house is indirect, shining up onto the ceilings and reflecting into the rooms. This lighting solution is appropriate to the style of the house which would never have had recessed lighting. Since the ceilings are sculptural, the reflected light picks up and highlights the feature of the shallow curving vaults. Other lighting is provided by sconces and in some cases pendant fixtures. The one room where recessed down lighting is used is the kitchen, where it can be planned for use over counters as task lighting.

FIGURE 5.4 Sketch study by the author of the Hackney house living room. This study shows the paneling around the room and the shallow vaulted ceiling. Note the way natural light enters the room on each side of the stone fireplace. (Drawing by Michael Malone.)

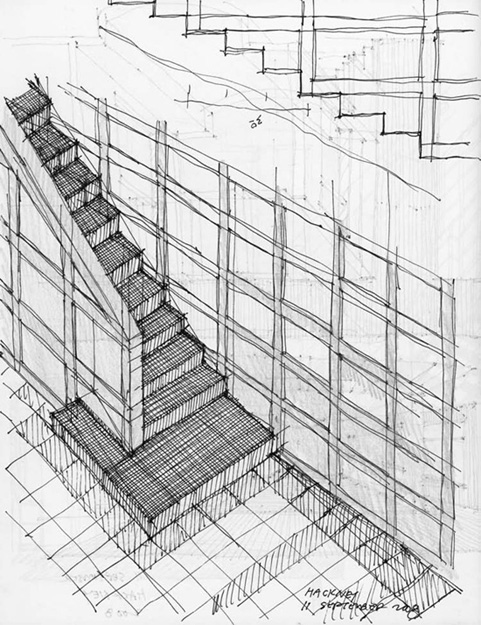

FIGURE 5.5 Sketch study by the author of the Hackney house entry and stair hall. Using sketches like these, the author was able to explain concepts for the design of the house to the owners and the project staff. Raised paneling is used to unify the entertaining spaces in the house (entry hall, living room, and dining room) and as the basis for the design of the stair to the upper level. (Drawing by Michael Malone.)

FIGURE 5.6 Sketch study for the Hackney house front porch and timber framing by the author. These sketches helped illustrate to the clients the idea of using craftsman-style details to make a house that was both traditional and contemporary. (Drawing by Michael Malone.)

For us this house illustrated that we could develop a design that was not overtly contemporary, while at the same time bringing our beliefs in careful planning and detailing to bear on a different architectural aesthetic. This would only have been possible with thoughtful and engaged clients, and we were fortunate to have them for this project (Fig. 5.6).