In 1923, a round-faced New Yorker in a dark business suit arrived via train in the small but bustling industrial town of Rockford, Illinois. The businessman, whose name was Phillip M. Chappel, made his way through the fray of trucks and horse-drawn wagons on the main street, on his way to a meeting with the stockholders of the local farmers’ cooperative’s meatpacking plant. The million-dollar plant on the edge of town had been built to slaughter cattle, but it had fallen on hard times because bigger factories in Chicago could undercut its price. The factory, idle for more than a year, was perched on the edge of bankruptcy. Chappel proposed something bold and unheard of. He had a plan that would allow the company to buy meat for almost nothing, sell it at a premium, and make them all rich. It required doing something many of the men found repugnant, but the money was so good that no one left the room. Two words: horse meat.

The town of Rockford, Chappel said, should become horse-meat capital of the United States. Timing was perfect. With the automobile taking over, the market for workhorses had collapsed. Mustangs from the West that once had satisfied a steady need for wagon-pullers in the East were now piling up in places like Montana and Wyoming. Ranchers would almost pay to get rid of them. Horses that once were the most valuable commodity in the West could be had for next to nothing.

The plan was simple: Round up as many mustangs as possible, drive them onto trains, ship them east, prod them up the cattle ramp, pack them into cans, and sell them as dog food. The approach was summarized a few years later by Time magazine as “round-up and ground up.”1

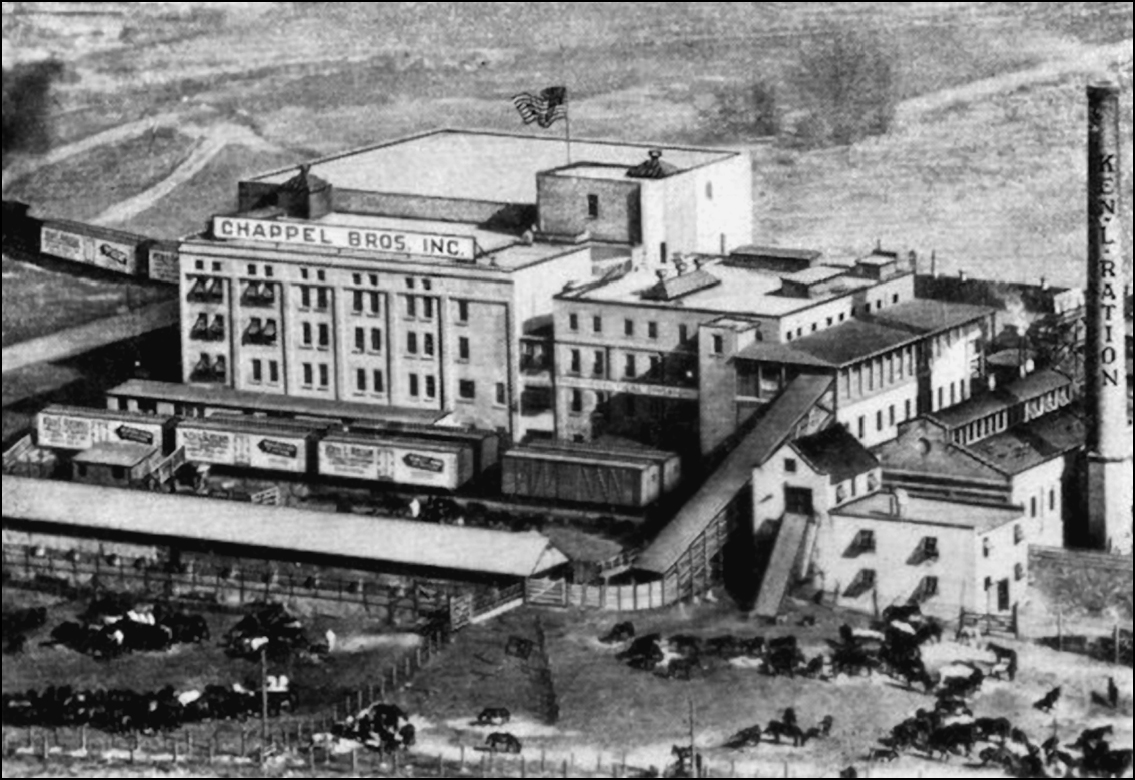

The investors agreed. By 1925, the Chappel Brothers factory in Rockford was up and running. A four-story brick plant rose in the center, bristling with smokestacks and steam pipes. A huge smokestack that towered over anything in town was emblazoned with its logo. Hammers clanged as workmen expanded the already sprawling complex, building new processing plants and new rail lines.

FACTORIES LIKE THE CHAPPEL BROTHERS PLANT IN ILLINOIS TURNED UNCOUNTED MUSTANGS INTO DOG FOOD AND FERTILIZER.

Every day, more than a dozen train cars wheeled into the complex, their sides often shuddering with the thunder of wild horse hooves trying to break the wooden walls. What those wide-eyed animals, which had grown up knowing only distance and freedom, thought of the stench of the boxcars could be surmised by the high-pitched shrieks and whinnies heard coming from the factory.

When Chappel proposed the idea, there were an estimated two million mustangs in the United States. A few decades later, hardly any were left. Many culprits helped do in the wild horse in the twentieth century: barbed wire, railroads, settlers surging into empty country, competition from cattle and sheep, a warlike campaign by state and federal governments against all wild animals that threatened agriculture, and, of course, plain old greed. But none did a fraction as much damage as Phillip M. Chappel—or P. M., as he was always called. Men had been chasing mustangs for meat and saddle stock for centuries in the West, but only mechanized, marketed, industrial-scale slaughter created both a financial incentive to annihilate wild herds and the practical means to make it happen.

I pieced together the saga of Chappel Brothers through clips from the local newspapers, the Rockford Daily Republic and the Rockford Morning Star. It is a largely forgotten story, but one that still has deep resonance—not just because it helps explain what happened to the vast wild mustang herds a century ago but also because it is a window into how people still react to the slaughter of horses, an issue that dogs the Bureau of Land Management to this day.

When the Chappel Brothers firm hatched its grand plan to turn mustangs into dog food, the term animal rights had yet to be coined. Still, the plan was not without its detractors in its day. People in that era had grown up with domestic horses. Many had used them for transportation or farm work. They respected them. Many found abhorrent the idea of turning a trusted servant into dog food. Some newspapers bemoaned the passing of the mustang and the sad fate of the slaughtered horse. At the same time, the United States was still in the throes of a Manifest Destiny–fueled bender of natural resource plunder, and there was a competing belief that mustangs, like timber and grass and minerals, should be used to fuel the nation’s progress.

At the Chappel Brothers slaughterhouse, that societal tension between love of horses and love of money eventually collided in a way that created headlines across the country and nearly destroyed the whole factory. But that wasn’t until later, after Chappel Brothers had become one of the largest slaughterhouses in the country.

P. M. Chappel’s success came down largely to being in the right place at the right time. Born in England in 1872, he emigrated with his parents as a young boy to Pennsylvania. As an adult, he moved to upstate New York, where he worked as a traveling salesman for Swift and Company—the Chicago meatpacking giant that was so horrifically efficient at slaughtering that it inspired Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle. In 1911, Chappel became a dealer in horses around the city of Rochester. It was a good time to be in the business. When World War I broke out, it ignited a massive demand for horses to move armies in Europe. In 1916 alone, Europe bought 350,000 horses from the United States. Prices spiked and Americans made good money rounding up excess animals and putting them on boats with a one-way ticket to the front. Chappel got a government contract and claimed to have sold 117,000 horses this way.2 Many of the horses that went to war were mustangs gathered by ranchers and sold to middlemen like Chappel, who shipped them east and put them on boats.

After the war, the price of horses hit bottom and Europe had exhausted its coffers. In America, the automobile and the tractor had arrived. No one was buying horses. A mustang that brought $30 in 1915 was now worth maybe $1.50. Many dealers got out of the business, but Chappel saw the bust as an opportunity. During the war, he had met a number of French officers, and through them he knew that while the demand for workhorses had dried up, Europe still had a hunger for horse meat. His experience with Swift had familiarized him with the world of large-scale, industrial meatpacking. It didn’t take much to put the two together. P. M. would buy old, worn-out horses from midwestern farms and wild horse herds in the West. He’d pay cowboys to bring them to railheads and he’d ship them straight to the killing floor. The good cuts would become pickled meat for Europe. The rest would become a product of his own invention: Ken-L Ration—the first-ever canned dog food.

In 1922, he opened a small New Jersey packing plant, supplied mostly by worn-out city horses, but he soon realized he needed a bigger factory and a bigger supply of horseflesh. He settled on Rockford, in a spot right between the supply lines of the East and the mustangs of the West.

Chappel employed crews of young men on horseback in Montana and Wyoming to gather up horses and drive them to the rails. These drives, sometimes sweeping up a thousand horses, were often punishing, since the cowboys were paid only by the head, not by the condition of the horses. They knew the animals were bound for slaughter, and they only had to get them to the rail line.

“There was little grass and the animals suffered accordingly,” one of those “canner” riders, Robert W. Eigell, remembered fifty years later in an article for the Western history magazine Montana. “It was one of the most depressing experiences I encountered in the West.” His bunch drove the animals twenty-five miles a day, leaving a string of dead horses all the way to the railhead.3 Mares stopped giving milk and their starving colts started to drop behind. Out of desperation, they nuzzled at the cowboys’ horses. One cowboy took out his pistol and dropped behind with the colts. The others heard a shot, then several more. The cowboy came back and said, “Poor little fellers don’t have to suffer no more.”

Horses arriving in Rockford often had spent days without food or water on the trip east. Packed together, they kicked and sometimes trampled each other. Many arrived dead.

At the factory, huge holding corrals with reinforced fences held hundreds of horses that gathered and broke in waves as cowboys on horseback tried to herd them toward the chutes. The mustangs were pushed up a long covered ramp that led from the final corral to the fourth floor, where a workman known as “the killer” waited with a silencer-equipped rifle. In 1925, the plant was processing two hundred horses a day—one about every two minutes.

On the top floor, carcasses were skinned and drained of blood before being moved to a maze of butchering rooms, where snaking lines of men in white aprons carved down the meat to manageable chunks that were sent down to cooking and baking rooms, then into the clanging machinery that would pack the meat into one-pound cans.

In a sense, the only thing new about what Chappel was doing was the scale. Rounding up mustangs in the West predated Chappel not just by decades but by centuries. As long as wild horses had been roaming free on the land, people had tried to catch them, both because they wanted to have them and because they wanted to get rid of them.

Early in the history of the West, mustangs were a valuable commodity—to be sold, traded, or trained as a new mount. But later, they became so numerous that many locals only wanted to destroy them. In all cases, until the mechanization of the twentieth century, corralling wild horses was extremely hard and often dangerous work, impossible to do on a scale that could ever drain the West of millions of horses.

The earliest way of catching mustangs is the one we still imagine when we think of wild horse roundups: the lone rider clinging to the neck of his pinto in a full gallop, half obscured by the hoof-pounded dust, jutting forward, one wrist cocked with the weight of a swinging lariat, ready to sling it out around a mustang’s neck.

The first recorded account of this may be from Washington Irving, the author of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle, who visited Comanche territory in what is now Oklahoma in 1832. One evening, after Irving had spotted bands of wild horses cantering over the rolling plains, a young guide in his party, half French, half Osage, came into the camp with a fine, two-year-old colt he had just captured. Around the fire, he told of how he had come across a band of six horses along the river. He chased them through the water, then tried to lasso one with a lariat on a pole, but the rope skipped off the horse’s ears. The guide galloped after the band, surging up over a hill and cresting the other side, only to find himself suddenly nearly airborne, plunging down a twenty-foot sand bank. “It was too late to stop. He closed his eyes, held his breath, and went over with them—neck or nothing,” Irving wrote.

In the confusion at the bottom, the rider managed to snare the colt, but then the colt jagged back around a tree, pulling the rope loose from the rider’s hand. The rider chased the colt out onto open ground and somehow got hold of the rope again, then spent considerable time trying to get the horse back across the river and back to camp. “For the remainder of the evening,” wrote Irving, “the camp remained in a high state of excitement: nothing was talked of but the capture of wild horses; every youngster of the troop was for this harum-scarum kind of chase; every one promised himself to return from the campaign in triumph, bestriding one of these wild coursers of the prairies.”4

That thrill of chasing mustangs never wore off. Westerners continued galloping after mustangs until the practice was outlawed in 1971. Clubs of mustang chasers in places like Salt Lake City and Reno used to rope wild horses on Saturday afternoons in the 1960s the way some people went fishing. Years later, I met a dentist who had grown up in western Colorado. He had become an advocate for wild horses and was working to oppose BLM efforts to remove them from a place called West Douglas Herd Area. As we hiked through the herd area on the lookout for wild horses, he grew wistful describing his days as a teenager in the mesas of the area, crashing through the piñons after mustangs. “I damn near killed myself,” he said, “but man, it was exciting.”

Chasing mustangs with a lasso, however thrilling, had too many limitations to ever be a good way to catch horses. The first problem was that you could only catch at most one horse per chase. The second was that the biggest, fastest, and most desirable mustangs were the hardest to lasso, especially when the pursuing horse was weighed down by a rider. But the biggest problem was that the mad dash of the chase held too many risks to rider and horse. A valuable saddle horse might step in a badger hole and break a leg chasing a useless old cayuse, or fall on his rider, killing them both. Folks living in Wild Horse Country developed a saying: “Chasing mustangs is throwing good horses after bad.”

While roping never went away, it remained a young man’s pursuit that was probably more about ego than it was about horses. Instead of lassos, mustang hunters developed more effective techniques. The frontier held many stories of a technique called “creasing,” in which a man would aim his rifle at a horse just along the crest of the neck and graze the vertebra—stunning but not harming the animal. The practice had obvious risks. A few inches off the mark and the horse would either run away or drop dead. And early documenters of the frontier often repeated the story but never reported witnessing the practice. It’s likely that creasing got far more use as a campfire story than as an actual catching technique.

A more calculated strategy used in Texas was to lie in wait. According to the historian Frank Dobie, some mustangers—as men who pursued the herds were known— would set out salt licks surrounded by hidden snares. A man would hide with a lasso on the ground near the salt, then pull when the right horse stepped in. The problem is that mustangs are smart and have a keen sense of smell. They often wouldn’t go near the trap, and men who waited for days eventually learned the strategy wasn’t worth the time.

Dobie also tells of a technique in Texas where cowboys would tie a dummy of a man to a mustang and then turn him loose, letting him tire out his entire herd as he tried to run back to them and they fled. When the horses were exhausted, cowboys could come in and rope the ones they wanted. But Dobie didn’t say how the cowboys managed to get the dummy on the first mustang—which may be why I found no other references to the practice. Like creasing, the strategy was probably better for storytelling than for catching mustangs.

A more dependable approach was colt catching. At the right time of year, a few months after mares had foaled, when the young were starting to eat grass, riders would charge a herd, chasing until the colts fell behind. The young horses were easy to rope, gentle, train, and sell. The practice was used for generations by the Spanish, the Horse Nations, and the Americans. In 1878, a pair of American surveyors in West Texas came across mustangers from New Mexico who were traveling slowly in a wagon pulled by two cows, leading a chain of thirty colts bound for market. Each was hobbled by a hair rope tied from its tail to its front ankle.5

In dry places, where the only water was from isolated springs, men found another approach. They built round corrals around water seeps where horses would come to drink. The corrals would stand open and unattended for most of the year, and horses would get used to going in and out for water, but when a mustanger wanted his catch, he would lie in wait as a herd sauntered in, then quickly close the gate.

In regions where water was too plentiful for these water traps to work, many mustangers used the technique that the BLM still uses in modified form today. They built sturdy, round corrals in places where the land would naturally drive horses together. At the opening, they erected long brush walls, like wings leading into the corral. Then riders working from all directions would drive herds toward the wings and into the mouth of the corral. For centuries, this technique was used in much of Texas, New Mexico, Nevada, and California—nearly any part of the West that had enough natural wood to build corrals. Hundreds of semipermanent corrals dotted the hills, and some can still be seen in remote places today. A few years ago, a rancher in Beaver County, Utah, pointed out a weathering corral built of silver-cedar logs. How long, I asked him, had that been there? “Near as I can tell, forever,” he said. “And we used it, too, until the law stopped all that.”

In the Wild Horse Desert of Texas, it was typical to gather two to three hundred mustangs per season, but you had to be careful. Too many and the horses would either break down the fences or trample one another in the corral, as the explorer Zebulon Pike noted in 1807, and their rotting carcasses would leave an “insupportable stench” that would make the corrals unusable.6

Most outfits lacked the manpower for such massive gathers, so they simply tried to “walk down” a herd. A small group of men, working in relays, would pursue a group of mustangs over several days. The first rider would set out at a leisurely pace, staying just fast enough behind the herd to keep them from eating and drinking. He would try to work them in a circle, so that twelve hours later he again would be passing by camp, where another rider would take his place. After two or three days, the horses were so exhausted that they could easily be roped or corralled. Often mustangers would mix tame mares with a captured herd to act as leaders when it came time to drive them to captivity.

Slowly, as settlers came into the West, the dynamic of roundups changed. What was once the pursuit of a valuable trade item—the horse—became an effort to clear that item from the land to make room for an even more valuable trade item: cattle. As Texas became more populated, stockmen organized massive roundups. On Mission Prairie in 1875, about 150 riders set out one summer day to drive horses from all sides of the region toward a lake in the middle. They had orders to shoot any horses that broke back. After several hours, a dark line of horses converged like geese. Many broke back and were shot or trampled. It’s said the men gathered fifteen thousand horses that day.7

These kinds of roundups could produce good riding stock for ranches, and a little extra pocket money, but they rarely netted enough horses to make a dent in the West’s vast population. It was like trying to drain a river with a bucket.

When the railroads came after the Civil War, the West finally had quick, easy access to eastern markets. More important, eastern capitalists had quick, easy access to the West. What followed was the wholesale liquidation of anything and everything of value in the West: timber, minerals, wildlife, grass. The federal government, having fought to rid the West of the Horse Nations, threw open the gates and invited settlers in. The historian Vernon Parrington, writing in the 1920s, called this time of rapid resource extraction—when speculators, creditors, railroad companies, and wealthy investors feasted on the virgin West—“the great barbecue.”8

It was a pattern that originated with the first trappers who stalked up western streams in search of furs and grew exponentially as access and demand snowballed. Bernard DeVoto, a historian who was born in Utah in 1897 during the barbecue era and later taught at Harvard, summed up the pattern of exploitation this way: “You clean up and get out—and you don’t give a damn, especially if you are an Eastern stockholder.”9

The first people to arrive in the West were generally there only to exploit natural resources, and they wrote the laws to protect their pursuits. Even if later settlers wanted to push for a bit of restraint, or even conservation, legally there were few ways to do it. The laws of the region can basically be summarized as “I got here first: it’s mine, not yours.”

The stock raisers, loggers, and miners in the West went along with it, DeVoto said. “The West does not want to be liberated from the system of exploitation that it has always violently resented,” he wrote. “It only wants to buy into it.”

Once the railroads reached Wild Horse Country and the Horse Nations were driven onto reservations, the Great Plains slowly became a giant pasture. Teams of hunters killed off the roughly thirty million buffalo within twenty years. They also shot tens of thousands of mustangs and stripped them of their hides, which were sent east. Horsehides had many uses, but the most notable one at the time was in the newly popular game of baseball. It’s said that the mustangs’ hide, which is softer and more textured than cowhide, made the best leather covers for balls, and made for a better curveball. We’ll never know how many baseballs covered with mustang skins were used in the major leagues. Also, at the turn of the twentieth century, horsehair “pony coats” became a fashion rage, boosting the demand for skins.

As the buffalo died off, the legendary drives of longhorn cattle started north from Texas. Less well known is that huge drives of horses also went north to places like Dodge City and Abilene, Kansas. “During the time of the longhorn drives, probably a million range horses were trailed out of Texas,” Frank Dobie noted. “Yet so far as print goes, for every paragraph that relates to the driving of these range horses, a hundred pages relate to the trailing of longhorn cattle. . . . The cowboy rode to glory but the horseboy never became a name.”10

Live horses were packed on boxcars and shipped east, where they were sold as low-end stock and ended up in the most unlikely places. One mustang named Hornet starred in “Professor Bristol’s well-known troupe of 22 performing horses,” where he did a rocking-horse act and skipped rope.11 One ended up pulling a smoked fish cart near Coney Island, in New York, where every summer afternoon he went swimming with his owner on the beach. But most of them simply ended up as anonymous, low-cost muscle that fueled country and city life in the nineteenth century.

One of their main destinations was New York City. Its bustling streets had an insatiable need for horses—the cheaper and smaller, the better. “The time for the degrading slavery of the wild Western mustang has come,” a reporter noted in the New York Times in 1889. “Within a very few months he has been brought to this city in droves and, at present, on the Third-avenue surface railway, at least, he outnumbers the Eastern horse in the ratio of nearly five to one.”12

The little weather-beaten horses had become the favorite power source for streetcars, the newspaper noted, because they were stronger and healthier. And since they were not much larger than ponies, they also ate less. “After they are once trained they work together with quite as much ease as their more civilized brothers. But before they are trained they are not inclined to peace,” the reporter said, noting they came off the train “as wild as a Manitoba blizzard” and often bit their handlers.13

On streetcar teams, mustangs were harnessed with tame horses until they learned the job. “Two days are generally sufficient to convince the mustangs that there is a point where obstinacy ceases to become a praiseworthy attribute,” the newspaper said. After two weeks, they are used to the noises and smells of the city, and have “an appreciation of the dull realities of Eastern life.”14

Of course, not all mustangs gave in so easily. Breathless reports of the latest mustang gone wild in Gotham were so common in the late nineteenth century that they became almost their own genre in the city papers. In one, a policeman made a daring rescue straight out of a dime novel, jumping onto mustangs bareback and riding through Central Park until he could calm the frightened animal. In another, a mustang got spooked by the clatter of a passing elevated train and took off down Forty-Second Street, dragging a wagon behind. It knocked down a little girl, plowed into another parked horse, smashed its wagon, and thundered down the street dragging the splintered wreckage through a crowd of strikers picketing a carpet works. Another, fresh off the train from the West, got away from a peddler and dashed through the carriage traffic of the Upper West Side, clattering onto a crowded sidewalk. “The broncho [sic] again played havoc with the throngs on the sidewalk, for it galloped at a terrific pace for five blocks, while thousands rushed into near-by doorways,” a report in that evening’s paper read. The mustang outran a police horse in pursuit, tripped over its own lead rope and tumbled twice, sprang back to its feet, turned a sharp corner and knocked over a beloved theater manager, and was headed for a park. On the corner, it was suddenly shocked to a standstill by a crowd of men who opened their umbrellas.15

The railroads continued to deliver fresh carloads of wild horses to the East from the 1880s through at least 1910. The West continued to replenish the population with little reported impact on the wild herds. But as the West grew more crowded and ranchers turned out more sheep and cattle, the naturally replenishing spring of horses started to be viewed not as a resource but as a problem. The vast herds on the prairie, which had so impressed explorers, exasperated the settlers who wanted to farm and raise livestock. Wild horses came at night, knocking down fences to abscond with domestic horses. “Large numbers of wild horses abound on the prairies between the Arkansas and Smoky Hill Rivers,” the Topeka Commonwealth reported in 1882. “They are of all sizes and colors, and are the wildest of all wild horses. . . . Settlers on the frontier would hail speedy extinction as a blessing, for when domestic animals get with them their recovery is simply out of the question.”16

Settlers began comparing the predations of wild horses with the raids of the Horse Nations they had recently driven onto reservations. “Not satisfied with its own freedom the wild horse has adopted the tactics of the Apache and the Sioux and stampedes its brethren,” a Colorado journalist noted in 1897. “Novelists have taught us to believe that the wild mustang is emblematic of freedom pure and noble. The Texas ranchman regards him as an emissary of the evil one, for he brings to his ranch despair and loss.”17

The simple solution, one many in the West yearned for, was to get rid of the mustangs, permanently. And, if possible, make money in the process. Where it was economical to ship them east, they did, but the Far West’s leagues of canyons and mountains gave herds too many places to hide. Even if horses could be caught, they were often far from rail lines, so there was no economical way to get them to market.

In places where wild horses had no realizable value, settlers treated them like they treated coyotes, prairie dogs, or any other critter they labeled “varmints.” They shot them. Starting in the 1870s, ranchers in Texas began cooperative hunts to try to eradicate mustangs on the Gulf Coast. Local and state governments got into the act, passing laws allowing open season on free-roaming horses. On the plains around Cheyenne, Wyoming, in 1884, one reporter wrote: “Wild horses have become so numerous on the Plains that some of the stockmen in this vicinity have organized a hunting party whose object will be to thin them out. The hunters are provided with long-range rifles, fleet ponies, and supplies and forage enough to last all Winter.”18

In the red mesas around Kanab, Utah, ranchers organized yearly hunts. Sometimes horses were shot on the run, but: “If possible the horses will be driven into some ‘blind’ canyon, where the work of slaughter will be made easy,” one observer noted.19

Though the myth of the West puts the cowboy and the wild horse on the same team, they were more often adversaries. “There!” one Wyoming rancher cursed in 1888, as he stooped over an immense black stallion bleeding from a bullet hole in its neck: “I guess you won’t steal anymore of my mares, you old rascal, you.”

“It seems a pity to kill such a fine animal,” said a journalist who had witnessed the kill, as the two looked down at the dying mustang.

“A fine old thief,” the rancher corrected him. “Why, man, do you know that cuss has stolen more than a dozen of my mares, and I reckon $1,000 wouldn’t cover the damage he’s done to this valley in the past summer.”20

Area ranchers took up collections to pay bounties for wild horses. Much of the killing was done by professional hunters, called “wolfers,” who made their living killing wolves, mountain lions, and any other offending critters. A lone wolfer traveling on horseback with a packhorse in tow could get up into the remote benchlands where mustangs hid. The aim was not to lasso the mustangs, but to shoot them. After dropping several from a distance with a rifle, a wolfer would lie in wait for wolves and lions that showed up to feed on the carcasses. A pair of wolf ears could be worth $4. A wild stallion’s scalp could bring up to $25.

In 1893, Nevada passed a law allowing anyone to shoot mustangs on sight. “There are now in Nevada more than 200,000 head of these horses,” a railroad agent in Reno told the San Francisco Examiner in 1894. “And they are increasing so fast that they are getting to be a great nuisance.” The herds were beautiful and included many fine horses as tough as pine knots, he said. “The trouble is, they are eating off the grass, so that sheep and cattle owners are having a tough time of it in some sections.”21

It is up for debate whether there were really more mustangs or whether there were just more settlers after the grass. Regardless, Nevada ranchers started shooting any mustangs that came in range. “They use long-range rifles, however, and ride fleet domestic horses, and in this way pick off a great many,” said the railroad agent. “Every rancher or wild cattle owner in Nevada, when he sees a wild stallion and has a weapon with him, turns loose at it.”22

Hunting pushed horses into rough, remote country. The hunters followed. It was hot, dangerous, difficult work. Most of the hunters were young men who lived outdoors for weeks at a time. But at least one was a woman. “She is a Californian, and a young woman, only 23 years old. Moreover she is respected for her many good qualities,” noted an 1899 newspaper profile of the lady mustang hunter. Her name was Maud Whiteman, and she was “an affectionate mother” and a “hospitable soul.” She would lie in wait at desert watering holes. When a band of horses came to drink, she would shoot the lead horse, aiming not to kill but to maim. The band would scatter at the crack of the rifle but then return to check on the disabled horse. Maud would then “rush from hiding, shoot as many as possible, and follow fleeing victims until all or nearly all are killed.” She skinned the horses and sold their hides for $2 each in California.23

WHEN WESTERNERS COULD NOT CAPTURE MUSTANGS, THEY OFTEN SHOT THEM, AS THIS 1899 ENGRAVING SHOWS.

Nevada eventually repealed the law allowing open season on mustangs because domestic horses started disappearing, and branded hides showed up in shipments of mustang hides.

The West’s desperation to rid the region of horses was a theme in some areas long before the coming of the railroads. In California, where the Spanish missions had bred horses for centuries, wild runaways flourished in the dry hills until they eventually outnumbered tame stock. One explorer in the San Joaquin Valley in the early 1800s said that “frequently, the plain would be covered, with thousands and thousands flying in a living flood towards the hills. Huge masses of dust hung upon their rear, and marked their track across the plain; and even after they had passed entirely beyond the reach [of] vision, we could still see the dust, which they were throwing in vast clouds into the air, moving over the highlands.”24

These herds, which had evolved to thrive in the dry West, outcompeted imported cattle and sheep. California’s small and isolated human population had no use for so many horses, and no easy way to trade them in the East. So Spanish ranchers simply drove the animals into the ocean. Reports from the missions show that in 1805 the Spanish drove 7,500 horses over the sea cliffs in San Jose. In 1806, another 7,200 were sent into the waves in Santa Barbara. In some roundups, horses were driven into corrals, lanced with long spears, and left to die.25

“An intimate story of the wild horses of the Southwest and the war waged against them would read like a dime novel romance. In everyday parlance, however, they are a nuisance and a pest,” a reporter wrote in the New York Times in 1912, echoing the growing frustrations that settlers likely had for generations. “As horses they are valueless and useless. They can no more be tamed and domesticated than the hyena. The stallions infest the tame herds of the ranges and taint them with strains of wild blood that make the offspring worthless.”26

Of course, generations of trappers and cowboys knew that wild horses were among the best horses in the world. But their ability to outcompete livestock and their skill in stealing domestic horses is hard to dispute. Often locals felt powerless against these fleet raiders.

“Their hiding places are all but impenetrable,” the Times reporter continued. “Like mountain sheep, no trail is too rough for them. The most intrepid riders have failed to round them up. A mounted man appearing is a signal for them to break for the wilds. No horse with a rider can keep their pace. Their endurance seems to be without limit.”27

As time went on, ranchers tried to improve on the old roundup strategy. They replaced wood-and-brush wings on traps with long swaths of canvas wings that were easier to set up than wood. They introduced tame mares into wild herds to make them easier to corral. A hunter in Utah announced he planned to shoot horses with a drug that would put them to sleep long enough to be roped and hobbled. Another in Nevada filled a water trough with a narcotic that left the horses dazed and easily captured. But he stopped the practice because a number of horses overdosed, and so did a number of cattle.

Then came barbed wire. In the 1870s, farmers and ranchers started stringing it across the West. By 1900, contemporary government statistics said Americans had put up more than 100,000 miles of wire fence. The spread of fences swept wild horses out of the Great Plains and most of Texas. They were pushed back to the broken, jagged country of the intermountain West that could not be easily fenced. This was particularly true in Nevada, where most of the range remained open, and long, rough ranges of mountains provided endless hiding spots for herds.

With increased fences and resources, ranchers redoubled their efforts to finally get rid of the mustang. In 1902, ranchers in Lander County, in the middle of Nevada, organized a massive horse hunt. They hoped that with the help of a hundred riders, “between 4000 and 6000 wild animals will be slaughtered and left as food for the carrion crows.”

“These animals dash wildly about the hills and valleys, destroying crops as well as scattering herded cattle,” a reporter for the San Francisco Call wrote of the planned hunt. “The horses are of no value. They cannot be tamed, and, in fact, cannot even be caught.” Here was the horse not as a natural resource but as a threat—a party crasher at the Great Barbecue. And like mountain lions or wolves or Comanche raiders, the westerners had a way of dealing with their unwanted guests. “Many of the animals will be shot on the run,” the reporter noted. “At the point where a meeting is expected pits have been dug, into which the horses will be run to their death.”28

Rarely were reports of the results of these roundups published, though when they were, the buckaroos—as cowboys are still called in Nevada—often spent way more time trapping far fewer horses than they had hoped. Even so, they kept at it. The largest wild horse hunt ever staged in Nevada was organized in Washoe County in 1909. Five hundred buckaroos swept a swath of territory fifty miles long, bringing horses to a central point near the northern end of the Nightingale Mountains. Desirable young horses were roped and sold. The rest were shot.

Ranchers in Nevada were so desperate to rid themselves of the herds that they lobbied for a federally funded war against mustangs. The manager of the state’s forest reserves asked Washington to call in the Army to kill horses, requesting that “sixty days of each year be set apart for the purpose, and that the horses might be exterminated under the skirmish conditions of general warfare.”29

“No fence is strong enough to stop these horses, and when they appear in force they have even been known to knock down and kill cows and calves,” said a story on the problem in the Los Angeles Herald. “Any one who finally finds an effective method to settle this problem will have done a great service for the stockmen of every state west of the Missouri River. As an old and experienced stockman, now in the employ of Uncle Sam, said of this wild horse problem: ‘Theoretically it seems a very simple matter to handle, but practically it is quite the reverse.’ ”30

The coming of the automobile complicated things further. The ready market for fresh horses to draw wagons and pull plows began to dry up. In New York in 1912, traffic counts showed more cars than horses for the first time. Streetcars went electric. Suddenly no one wanted mustangs anymore. The last horse-drawn streetcar in Manhattan trotted down Bleecker Street in 1917. The horse market collapsed and mustangs on the range were no longer worth the cost of catching. Ranchers decided to just kill them. In 1927, that forest ranger in Eureka, Nevada, reported that he shot 1,046 wild horses to get them off the range.31

But shooting was often time consuming and only marginally effective, so ranchers kept searching for creative ways to rid the West of mustangs. In Oregon, they asked the US Army to fly in with bombers to destroy the state’s wild horse herds. In Utah’s Skull Valley, they tried to recruit tourists to do the work. “Americans who like adventure and excitement in a hunt are advised to try their hand at hunting wild horses,” a 1920 announcement in Popular Mechanics declared. “They will find this sport quite as thrilling as cornering a tiger.” An expedition had shot 102 horses, the notice stated, and “ranchers in Skull Valley invite shooting parties to go after the wild horses and [will] furnish guides and other necessary supplies.”32

Despite these sustained efforts, mustangs did not face annihilation until the rise of meat factories like Chappel Brothers. The mechanized plants started springing up on the edges of the West at the turn of the twentieth century—always next to rail lines that reached into Wild Horse Country like long straws. Their thirst knew no end. And they would eventually nearly drink the West dry. The first reference I can find of wild horse meat processing is from 1895, when a Portland, Oregon, canning factory specializing in wild horses announced its grand opening, noting: “This is a legitimate industry, and there is a large supply of raw material in Oregon, consisting of half-wild horses—the majority of them young, and substantially all of them, presumably, in wholesome condition—for which there is no other market”33

In 1911, there is another reference to a group of cowboys in Colorado who got a contract with California soap factories to round up thousands of wild horses for $5 a head.

In 1919, Congress changed laws to allow for federal health inspection of horse meat, and, along with Chappel Brothers, a number of canneries opened around the West. In Los Angeles, Ross Dog and Cat Food became a destination for horses and burros in the Southwest. In San Francisco, the chicken-feed plant in Petaluma was a pipeline that drained much of Nevada. In Portland, Oregon, the Schlesser Brothers plant feasted on the huge herds in the state’s eastern deserts, packing the remains of hundreds of horses a day into big barrels to be shipped east to New York, then across the ocean to the Netherlands.

With the steady price from canneries, ranchers could plan bigger and more ambitious roundups, knowing that the maw of the meatpacking industry would pay for everything they caught. In New Mexico, ranchers banded together on a drive in 1928 to push thousands of horses to a fertilizer plant in El Paso. One reporter called it “the journey of death.” This was the reality of the mustang that the dime novels of the time often ignored. There were no gallant young men in chaps. With little forage or water on the way, scores of mustangs collapsed and were left in the dust. “Some of the doomed horses were wild and spirited at their start across the desert, but none were at the end. Those that survived death gave little indication of ever being free.”34

Some bemoaned the passing of the West, but their eulogies were hardly enough to hault the liquidation of the open range. It was seen, in a way, as inevitable. “The wild horse—a symbol of pioneer America—is making its last stand,” one easterner said in 1935 on observing the relentless roundups. “The wild buffalo is gone; the traders and prospectors have vanished; the Indian is on his reservation; the blue-coated cavalry-men of the old United States Army are history. Sole survivor of the era which carved out Western America from the wilderness is the wild horse. With the swift flight of the years the bands of wild horses become smaller. Ranges which once thundered to their battering hoofs are silent.”35

The biggest buyer of mustangs by far was the gleaming new Chappel Brothers plant in Illinois, which contracted mainly with cowboys in Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado.

“The first chapter has been written in the greatest wild horse roundup ever held in the west,” a correspondent for the New York Times breathlessly reported in 1929. “Hundreds of horses large and small, vicious and indifferent, mustangs, ‘fuzz tails’ and ‘broncos’—are in pastures ready for the first sale and elimination.” In the wide-open plains of central Montana, a young rodeo cowboy and movie actor named Carl Skelton, wearing chaps and a six-shooter, was running the show and invited newspapermen to go along as his cowpunchers gathered wild horses on the range along the Missouri River. “There’s six or seven thousand wild horses on the Cascade range,” he told reporters. “I’ll bring in five thousand or more.”36

Reporters covered the roundup like a real-live Western—a snapshot of the last wild moments of the frontier. What they didn’t report, and perhaps Skelton had failed to mention, was that the main character in this Western was the midwestern meat canner, Chappel, who paid Skelton and his men to do the work.

Chappel Brothers’s big product was its canned dog food, Ken-L Ration, which Phillip M. Chappel had invented. Before Ken-L Ration, most dogs had just eaten whatever scraps owners dropped. Chappel family lore has it that Phillip Chappel got the idea for canned horse-meat dog food from watching dogs fight over horse offal at his slaughterhouse. Another inspiration might have been the canned “trench rations” developed for troops during World War I. Ken-L Ration cans rolling out of the factory featured a colorful label with a picture of dogs playing poker, and emblazoned with the slogans quality made it famous and a horse-meat product.

To get Americans used to the idea of canned horse meat, Chappel enlisted the country’s biggest dog celebrity, the silent film star Rin Tin Tin. When Chappel made the proposal to the owner of Rin Tin Tin, he balked at feeding horse meat to his dog. But Chappel opened a can and ate a piece himself to show how good it was. It worked. In ads on his weekly radio show, the German shepherd plugged Ken-L Ration as a delicious, nutritious treat, and cans flew off the shelves. By the time the factory was at full capacity, it was churning out nearly six million cans a year.

Not everyone celebrated the Chappel Brothers innovation. The local humane society in Rockford complained about the gaunt, stumbling horses coming off the packed railroad cars. Many in the public thought shooting horses for dog food was just plain wrong. The United States has never been much for eating horses. While it was not always necessarily taboo, horse meat was always a sign that something had gone wrong. The public equated it with disreputable butchers selling it as beef. Though many mountain men learned to love the flavor and tenderness of colts from tribes like the Comanche and the Apache, who prized the meat, frontier lore turned eating horses into an example of ultimate desperation—a deed only slightly less ghoulish than cannibalism, done only when all options were exhausted. To turn a trusted companion into chunks of meat was bad enough. To do it for dogs was more than many people could stomach.

Charles Russell, a Montana painter whose vivid scenes of cowboys and Indians on horseback helped create the myth of the West, decried the practice of shipping unwanted mustangs east for slaughter. “If we killed men off as soon as they were useless,” Russell wrote, “Montana would be a lot less crowded.”37

In 1928, a journalist named Russell Lord traveled the West to report on the rapidly disappearing mustang. Writing in the magazine The Cattleman, he started out determined not to be sentimental. “The romantic story of the American wild horse is being brought, of necessity, to an end,” he wrote. “In strict accord with the practical necessities of range agricultures, the work of ridding the Plains of wild horses goes on. They eat too much grass, these horses drink too much from streams which else would sustain peaceful and profitable herds and flocks of cattle and sheep. . . . In a word, the wild horse has become a pest. He must go. Whether you like it or not, there it is,” he wrote.38

But then Lord visited one of the western slaughterhouses—a forlorn, ramshackle place where he found 450 “miserable, slabsided, bedraggled horses.” He sat down with the owner, who complained of the work. Cranks wrote letters accusing him of cruelty. “Sentimental old ladies” came sniffing around, he said. No matter how kind he tried to be, he was a hated man. Worse, by 1928 the easy-to-reach herds had all been ground up. Supplies were down, costs were up. “It’s a rotten business,” the owner said. “It’s on the skids. There isn’t anything in it. It is being overdone. It would soon be over and I’ll be damn glad of it.”

A small band of five mustangers moseyed toward the plant as Lord watched, driving sixty horses gathered from the surrounding country. They were a sorry group, both men and horses silent, shambling, beaten, with their heads down. They’d get $5 a head for their trouble. A railroad brakeman in the yard with Lord looked at them, shook his head, and said, “Three hundred dollars will keep those five birds in liquor for a week or so. Then they’ll ride out again.”

Lord talked to the lead mustanger about his business. He didn’t like it, he said. It was just a dirty job. He would only take the horses as far as the rail yard. “You couldn’t pay me, not for money, to drive a bunch of horses up to the slaughter house,” he said, adding, “All along the line, as one seeks facts, one encounters as to the horse meat business a confusion between hot, instinctive repugnance and cold, calculating common sense.”39

In the end, the journalist was unable to reconcile the myth of the noble mustang and the maw of the meatpacking plant. He still thought horses were a pest on the range, but he decided canneries were a desecration for such a proud animal. “Forget the five dollars a head,” he said. “Shoot the mustangs where you find them. Let them go back to the earth out there in the open, where they lived.”40

The Chappel Brothers factory churned on, despite people’s grousing. More trainloads of mustangs went up the ramp each day. And the Chappel brothers themselves were getting rich. But in October 1925, strange things started to happen. First a fire erupted one night in a corner of the plant, where it appeared someone had splashed gasoline on the back doors. Then a 2,300-volt power line snapped, sending arcs of electricity through the night and making the factory floor go dark. Closer inspection showed the cable had been cut. A few days later, another fire broke out in a different corner of the plant. Workers rushing to put out the flames found cans of gasoline stacked in a corner to feed the inferno.

It was clearly the work of a saboteur, but managers didn’t know what to make of it—perhaps some union agitator from a radical group like the Industrial Workers of the World was bent on bringing them down. But they knew of no labor problems at the plant. If anything, P. M. Chappel, who called nearly everyone in the plant “honey boy,” paid well and was liked by the workers. But there could be little doubt that someone was trying to destroy the factory.

For a few weeks after the second fire, all was quiet. The cannery kept humming. Droves of mustangs went up the chute. Then, on November 21, 1925, an off-duty fireman driving home late at night saw flames leaping from a window in the plant’s west wing. He sounded the alarm, but by the time engine crews responded, fire was bursting from all the windows on three floors. Embers rained into the corrals, causing hundreds of horses to stampede in panic. The glow could be seen from all over town.

The thick brick walls of the factory withstood the fire, but the insides didn’t. Flames raged hot, spreading up walls and licking across rafters. The top killing floor collapsed. Then the carving floor. Then the canning floor. Dark cyclones of smoke must have poured out as thousands of pounds of canned meat exploded and burned. Two boxcars loaded with Ken-L Ration caught fire, burning so hot that only their iron trucks remained. Firefighters fought to keep the flames from the refrigeration wing, where enough ammonia gas was stored to level half the town. They succeeded, but it was one of their few victories. When the flames were finally doused the next day, most of the slaughterhouse was gutted. The Chappel Brothers firm had lost more than $75,000 in horse meat.

But if the saboteur thought he had stopped the factory, he was wrong. P. M. Chappel told the local newspaper that he would reopen again in a matter of weeks.

Though investigators could not find sure signs of arson, Chappel was convinced someone was trying to destroy his factory. He ordered workers to build a ten-foot fence around the grounds, and he hired private detectives to patrol with shotguns. For weeks, armed guards walked the complex at night, searching the shadows with flashlights for a saboteur. Managers interrogated the workers, looking for anarchists or union radicals, but found nothing.

Then one night in early December of 1925, well past midnight, a guard on his rounds came around the power plant and saw an inky figure slink into the shadows beneath the huge KEN-L RATION smokestack. When the guard crept over for a closer look, he saw the figure crouched in front of a bulging shape at the base of the smokestack. “Stop! What are you doing?” the guard yelled. When there was no answer, the guard raised his shotgun and ordered the prowler to come out.

A shot rang out as the prowler fired a pistol from the shadows and then turned and ran. The guard fired his shotgun, then fired again. When the intruder stumbled at the edge of the darkness, the guard took a few steps forward. But then the prowler sprang to his feet, fired back, and disappeared into the night. The guard sounded the alarm and men poured out along the perimeters, checking the fence and sweeping the shadows with flashlights, but the trespasser was gone.

Walking back to where the man had first been spotted, the guards found a black suitcase. It was so overstuffed that it had been held closed with baling wire. They untwisted the wire and opened it. Inside were 150 sticks of dynamite—enough to destroy the whole plant. A nine-foot-long white fuse snaked out along the ground. Someone noticed it was lit and slowly sizzling toward the charge. The guards quickly snuffed it out.

That night, a cold December storm swept in, and gusting winds beat rain against the town. Police fanned out over the city, looking for the bomber. They searched all night and through the next day. They checked the hospitals and hotels. It looked like the saboteur had gotten away. Then, late that afternoon, two boys walking home from high school found a man passed out in a field. His clothes were soaked with rain, his back was caked in blood. His hand gripped a large revolver. The authorities had their man.

A shotgun blast had hit the man in the back, and pellets had lodged in his lung. He was barely conscious from pneumonia and loss of blood. He was taken first to the jail, then moved to the hospital. Fortunately for him, the Chappel Brothers guards were only packing birdshot, which had left him bloodied but had not pierced too deeply.

The man was small and thin, pale in complexion, with neat dark hair he parted sharply to the right, and light blue eyes that bulged slightly out of his face. Police searched his hotel room and found Industrial Workers of the World literature that encouraged violent action against unfair employers. The police told the local paper they were “convinced he was one of the most dangerous anarchists ever apprehended in the area.”

Late that night, the man recovered enough to speak. With the state’s attorney and a stenographer in the room, he made a bedside confession—one he likely thought would be his last. His name was Francis Litts, but everyone called him Frank. He was polite and well spoken. He was calm and sincere as he spoke. He said he was forty-one years old. He had been born in upstate New York but raised in Montana and Idaho, where his father kept sheep and drove them up into the mountains each summer. He had grown up around horses, and he loved them very much. As an adult, he had wandered the West, working in mines in Alaska and California. He was a kind man who sent money home to New York to buy Christmas presents for his relatives, and sometimes he sent chocolates. But he could also be unpredictable. His brother’s granddaughter told me that family lore held that he once attacked a man for whistling.

A MUGSHOT OF FRANK LITTS.

In the hospital, the prosecutor pressed Litts about his labor activism. A reporter from the Rockford Daily Republic was there to record the conversation. The prosecutor pressed Litts about the pamphlets the police had found. Litts said something that surprised them. He admitted, calmly, that he had tried to blow up the plant. But he was not trying to destroy Chappel Brothers in solidarity with the workers. He was trying to destroy it in solidarity with the mustangs.

“I was in Miles City, Montana, when I first heard about range horses being shipped east to be killed for food purposes. I believe that the killing and corralling of wild horses is wrong,” he said.41

In Montana, he had seen the mustangs being loaded for the Chappel Brothers plant, he said, and decided the only way to stop such an evil factory was to destroy it. He headed east on the same train line. He applied for a job at Chappel Brothers so he could case the factory, he said, but soon left because he couldn’t bear seeing the horror inside.

He told of the first night he tried to burn the place down, pouring gas on the back doors. “After I touched it off, I ran through the fields, reached the business section, and went to sleep in my room at a hotel,” he said, his voice growing raspy with exhaustion. “I didn’t wait to see if the fire was going to damage the building or not, but I guess it did, but not enough.”

A nurse stopped him and made him drink water. She urged him to rest, but he pushed on. He said he kept watching the plant, and the sight of more trainloads of mustangs arriving enraged him. He tried again to set fires with more gasoline. And again. He thought the big fire in November had done the trick, but, after repairs, the plant kept churning out cans of meat.

So, he said, “I went last week and bought 150 sticks of dynamite.” His plan was not to kill anyone. He had about ten minutes’ worth of fuse, he said, which would give him just enough time to warn the workers to get out.

Throughout his interview, he was courteous and clear-headed, but he showed no remorse. “I would rather see my body or my mother’s ground up and used for fertilizer than to have horses killed like they are here,” he said, adding that he was looking forward to standing trial, because he was sure the public would feel the same way.

Though the decision of Litts to dynamite a dog-food factory is extreme, his deep respect for horses is hardly rare. It’s often said that one of the reasons horses became such successful domestic companions is that they are innately social animals. Horses have lived in family bands for millions of years, and they are all wired to be attuned to the moods and signals of other members. People successfully domesticated horses because we were able to tap into that capacity for trust and dependence. What gets less attention is that this domestication is a two-way street. We, too, are also wired to be social animals. The urge to reach out and connect with animals is something so basic in our fabric that it is universal across cultures and arises shortly after birth. Horses have also tapped into our capacity for trust and dependence. We forge relationships with them that are in ways very human. We talk to them. We give them names. We connect. And when we do, we implicitly extend to them the social contract of humanity: fairness, kindness, honesty, trust. The word humane, which is how we are supposed to treat horses, comes from the word human. It is perhaps because of this social contract Americans have extended to the horse that we do not eat them, and since the time of Chappel Brothers, we have done away with horse slaughterhouses in this country entirely.

Litts, like most people of his era, grew up with horses. He respected them. To him, they were not meat or marauders but companions. To him, slaughter was akin to murder. What choice did he have but to try to stop it?

The principle of animal rights was beyond a fringe idea in 1925. Vegetarianism was essentially nonexistent. In terms of radical activists, Litts was at least fifty years ahead of his time. People living on farms slaughtered animals themselves, and the practical economics of farm life didn’t allow much room for the rights of other creatures. But horses did have a special place in many people’s minds. Families often kept workhorses long after they could work—they were “put out to pasture.” A century ago, these horses even had a name: Old Dobbin. Most people of the time grew up knowing at least one Old Dobbin they would visit in the back pasture. Perhaps because of this widespread support of horses, the story of the mad cowboy trying to save mustangs from the cannery went out on the wires and ran in newspapers all over the country. Many in the public were sympathetic. Telegrams of support addressed to “the cowboy” began to flood the jail from all over the country.

The authorities in Rockford tried to head off the idea of Litts as a dime-novel folk hero by portraying him as a hopeless nutcase. Ernest Chappel, P. M.’s brother, questioned whether Litts really was a Montana cowboy and suggested he was, in fact, really a miner—a job that at the time was synonymous with violent anarchists. If Litts were a real cowboy, he said, he would support what Chappel Brothers was doing. “The people of Montana are eager to get rid of these wild horses as they take the feed the cattle need,” he told reporters.

The Horse Association of America also got in on the public relations campaign, saying the animals being slaughtered at the plant were not really horses, but “worthless Cayuses, descended from the mustang, but inferior, having deteriorated from inbreeding and lack of food.” A spokesman told the Associated Press that “it was more humane to slaughter them than to let them starve to death on the range in old age.”

The press took up the drumbeat, calling Litts “the eccentric Montana cowboy” and “the little man with a cow pony complex.” They wondered whether he was truly crazy or just “a tool of an organization trying to destroy the horsemeat industry.” But many in the public sided with Litts, and some even joined in his cause. A week after he had been arrested, police again surrounded the Chappel Brothers plant after Chappel saw what he thought were suspicious figures casing his plant, and he got a call from a man who said, “We’ll get you, look out.”

In jail, Litts spent his days reading books on his cot and writing letters to senators, city councilmen, and anyone else he thought would listen. He wrote a letter to Grace Coolidge, wife of President Calvin Coolidge. A noted animal lover, she had once spared a raccoon sent to the president for Thanksgiving dinner, then let it live in the White House. In his letter, Litts described the sadness of the horses as they learned their fate, and the tears that rolled out of their eyes.

We don’t know what books Litts read in his cell, but we do know many of the best sellers in the years leading up to the bombing attempt were romantic portrayals of the West, including Zane Grey’s The Vanishing American—a tale about a greedy capitalist who tries to round up wild horses for profit.

Frank Litts seemed to be looking forward to his trial as a public platform. “I’m going to tell the world about the conditions down there at the packing plant,” he told a local reporter. “I’m not sore at anyone around here, but I just want a chance to tell what I know.” Prosecutors seemed intent on not letting that happen. They decided to test Litts’s sanity, so they hired a local “alienist” named Dr. Sidney Winglus to evaluate him. In an interview with Litts, the alienist discovered that Litts had previously been in two insane asylums.

Eleven years before his arrest, Litts was locked in the Morningside Hospital for the insane in Portland, Oregon. There, too, he advocated against what he thought was injustice, sending a letter to his state senator complaining about poor conditions where inmates ate bowls of watery gruel with no spoons and were packed by the dozen into rooms with no chairs. Shortly before traveling to Illinois, Litts had been put in Morningside again after what he said was an argument with his father over a girl Litts wanted to marry. Litts escaped from that asylum in Oregon and went to Montana, where he heard about Chappel Brothers and headed east.

The alienist asked Litts why he tried to blow up the Chappel Brothers plant. Because horse slaughter was morally wrong, Litts said. He listed a number of reasons, including the Bible’s ban on eating meat from animals that don’t have a cloven hoof. The alienist asked Litts whether he felt specially called upon to destroy the plant. Litts said yes. “Religious paranoia” was the alienist’s diagnosis. Cautioning that it would gradually grow worse, he suggested locking Litts in an institution for the criminally insane as soon as possible.

Other people who came in contact with the well-spoken little cowboy thought he seemed fine, and fully aware of what he was doing. “I don’t claim to be an alienist,” the physician treating him for the gunshot wounds told the local paper. “But in my opinion, Litts appears sane.”

If Litts’a state of mind was debatable, his aim was clear. He wanted to destroy the factory, and he wasn’t going to stop just because he had been jailed. During his arraignment, a week after his arrest, he found himself sitting on a bench near the front of a busy courtroom as a crowd of attorneys sorted out the day’s docket. Seeing a chance, he suddenly sprang up, sprinted down the aisle, and disappeared out the door. The deputy in charge chased after him. All eyes remained fixed on the doorway. Eventually the breathless deputy appeared with his quarry after tackling Litts near the elevators.

The deputy put Litts back on the bench and stood behind him, ready for any move. Litts sat quietly as he waited to enter his plea. Suddenly, he dove forward again, crashing through a crowd of lawyers toward a door to the jury room. The deputy caught him by the knees. For the rest of the morning, he sat handcuffed. “Why’d you do that?” asked the deputy later. “You knew you only had a one in a million chance.” “I had a chance didn’t I?” Litts said. “And why not take the chance?”

The bombing attempt barely caused a hiccup in production at Chappel Brothers. A few weeks after Litts was arrested, the local newspaper reported that “one thousand Montana mustangs have been slaughtered the last week by Chappel Brothers.” The meat would go to Europe for Christmas feasts, the article said: “Whole carcasses are barreled for exportation, but corn beef, soup, mince meat and other products are also made.” The reporter noted, “No horse meat is sold for human consumption in this country, but occasional visitors to the plant are given the opportunity to sample the steaks, and greatly to the surprise of most of them, find the meats real delicacies—tender and of excellent flavor.”42

Charged with arson, Litts pleaded not guilty. When his trial started, in February of 1926, he entered court with dozens of pages of handwritten notes held in a tight roll. This, he had told his jailers, was his defense.

The first day of trial, Litts’s court-appointed defense attorney called Dr. Winglus, the alienist, to testify that Litts was insane. Litts sprang to his feet. He was willing to be found guilty, but there was no way he wanted to be dismissed as crazy. He shouted that he did not want the doctor to speak. “I’m being tried for arson, not for sanity,” he told the judge. His lawyer stood and began to make the case to the jury that they could not convict Litts because of his mental state. “Now you cut that out!” Litts shouted. He made his attorney sit down, then gave what the newspapers called “an eloquent speech” to the jury about how the horse was man’s best friend.

Litts’s lawyer interrupted and asked about previous stints in asylums. Litts shot back that he was being tried for arson, not his past. He asked for the county humane inspector to testify, but the judge refused to call him. His attorney again tried to make the case that his client was incompetent. “I am sane, I can control my acts,” Litts insisted. Litts turned to the judge and said, “He’s throwing me down, trying to make me out that I’m crazy when I’m not!”

The jury deliberated for eleven hours, with two men holding out because they didn’t believe Litts was crazy. Eventually, though, they came back and told the judge that the fires and attempted dynamiting were “the acts of a lunatic.”

Litts immediately stood up and asked for a new trial. “How can a jury deciding if I’m guilty of arson find me insane?” he asked. The judge banged his gavel, calling for order, and sentenced Litts indefinitely to the Illinois Asylum for the Criminally Insane.

It must have been a hard moment for Litts. He had hoped that he could reason with the jury and show them that what he had done was justified by the horror inside the factory. If they found him guilty, he could go to prison with a clean conscience, knowing that even if society was wrong, he had done right. But by finding him insane, the jury denied him any morality. It wasn’t just that they denied he had made the right judgment, they denied he was even capable of making a judgment, and they stripped him of the very thing that was most central to him—his sense of right and wrong.

It was a long drive down to the insane asylum in the southern part of the state, in the town of Chester. Litts sat calmly in the back seat as the sheriff of Rockford drove. According to the local papers, Litts told the sheriff unapologetically that he would one day return to Rockford, and the next time he tried to destroy the Chappel Brothers plant, he would “do it right.”

The asylum had castlelike stone walls. Litts walked down the long corridor of cells that echoed with the shrieking and mumbling madmen. He wouldn’t stay long. Seven days after he arrived, he went out in the circular exercise yard with the rest of the inmates, and, under the watch of armed guards, he disappeared. The guards only noticed him missing after an hour, when they counted the inmates before dinner. Some later theorized the tiny man had slipped out through a small opening in a gate while exercising. Others thought he had hidden under some mats in the yard, then escaped in the chaos as guards rushed out to search for him. Either way, he was loose.

The next day, a bold headline in the Rockford Daily Republic blared what Chappel likely immediately thought when hearing the news: DYNAMITER FLEES CHESTER, FEAR LITTS MAY RETURN TO ROCKFORD.

When he slipped out of the asylum gates in March 1926, teams of guards with dogs swept the farms around the grounds and combed the banks of the nearby Mississippi River, but they couldn’t find him. People around the Chappel Brothers plant in Rockford worried he would come back for another try at the plant. Locals flooded the police station with calls saying they had spotted him. He was driving by the plant, one said. He had been spied walking down an alley, another said. The Chappel Brothers firm beefed up its squad of armed guards and erected floodlights around the plant. The cops doubted the runaway cowboy would return right away—first he would need to earn money and devise a new plan—but they had no doubt he would be back.

Over the next several months, Litts became the town’s version of Boo Radley—a half-real, half-myth dynamite cowboy bogeyman who lurked in every shadow. Any report of a suspicious figure or odd occurrence was immediately ascribed to Litts. A local train was robbed and authorities suspected Litts. A drunk wandered over to the fence of the Chappel corrals where colts were kept. He was rushed by armed guards and was hauled to jail until he could prove he wasn’t Litts. A religious fanatic shot a man at a rural dance, miles outside of town. It was immediately assumed to be Litts. A small, thin drifter stabbed a rodeo cowboy in Oregon; Rockford newspapers blamed Litts. Rumors gradually cooled after all these reports turned out to be false. Maybe he wasn’t coming back. Maybe he had drowned trying to swim the Mississippi, or gone back to the wilds of Alaska. Maybe he was riding the range in Montana. This was certain: He wasn’t in Rockford.

Trainloads of mustangs kept pulling into Chappel Brothers. The operation expanded. It opened new factories. It added new products. It even began leasing ranch land in Wyoming and Montana, where it could gather even more mustangs. It soon controlled 1.6 million acres in the West—an area the size of Delaware. Then, one afternoon in November 1927, a tidy little man with hair parted sharply to the right checked into a hotel in Rockford under the name of Joseph Stewart. He asked for one of the cheap rooms and went upstairs to put away his suitcase. A few minutes later, he came down to listen to the lobby radio, which was tuned to a Notre Dame football game. He leaned back in one of the hotel’s armchairs and eventually fell asleep.

Some time later, a woman doing the evening shift at the front desk walked into the lobby to start work. Before taking a job at the hotel, she had worked for years as a matron at the county jail, where she took food to inmates and tended to their needs. She passed by the sleeping man and immediately recognized his dark, flat hair; his thin face; and his protruding eyes. It was Frank Litts.

A few minutes later, Litts was shaken awake by the sheriff’s deputy who had arrested him two years earlier. “Come on, Frank,” he said, “you’re coming with me.” The man looked up at him, politely smiled, looking genuinely perplexed, and said, “Who’s Frank?” Then he made a break for it.

The deputy tackled him by the door. He put him in handcuffs and searched his pockets, finding a packet of red pepper Litts was carrying in case he needed to throw it in someone’s eyes to escape. The officer also found a bill for 150 pounds of dynamite that had recently been shipped by train. At the jail, the suspect continued to insist he was not Frank Litts, but Joseph Stewart. To end the debate, the sheriff pulled up the man’s shirt and found scars from two years earlier, when a guard at the Chappel plant had hit him with a shotgun. The next day, police found three boxes of dynamite hidden in a pile of lumber near the train station.

In jail, when a group of newspapermen interviewed Litts, he continued to insist he was a victim of mistaken identity. “Who is this Frank Litts and what has he done?” he asked, appearing befuddled. But when the reporters got him onto the subject of horses, he lost his composure. “The people of this country owe their existences to horses,” he said. “It’s a terrible shame to take these animals that have done so much for us out and kill them. Suppose we take all the old men in our country out and kill them after they have worked hard all their lives? It is just as horrible to kill horses.”

A little over a week later, the sheriff who had taken him to the asylum less than two years earlier locked Litts in leg irons with a chain on his waist tied to a deputy. Afraid that sympathizers might try a rescue, the sheriff sneaked Litts out of the jail at 4 a.m. On the long drive back to the asylum, Litts said to the sheriff, “Take care of that dynamite, because I intend to be back some day.”

Litts was a man of his word. Four years later, in 1931, while 175 men were exercising in the walled yard of the asylum, he and eleven other inmates tried to scale a fire escape of a building that made up one of the walls. A guard peppered the group with shotgun blasts and Litts fell back into the yard with a punctured lung. The report of his shooting was the last time his name ever appears in the newspapers.

Though the warden at the time was unsure whether Litts would survive the night, he lived seven more years, eventually dying of a lung ailment in 1938, at age fifty.

The moral outrage Litts so explosively expressed in the 1920s has become much more widespread in the United States. You will not find horse meat these days on supermarket shelves. People refuse even to feed it to their dogs. During the 2000s, there were three slaughterhouses left in the United States—two in Texas and one in Illinois—that survived by sending frozen meat to Europe. But they closed down in 2007 after Congress, under pressure from horse welfare groups, defunded the federal horse-meat inspection program, effectively blocking all sales. Today, more than 100,000 American horses are still slaughtered every year for meat, but they are exported to big plants in Mexico and Canada, where most of the meat is packed into frozen containers and shipped to Asia and Europe.

The story of Frank Litts has been all but forgotten. But as the nation struggles to find a sustainable solution for wild horses in the West, we might do well to remember it, because its themes continue to reappear. When Litts was sentenced, the Rockford Morning Star called him “A remarkable example of the insanity that carries a humane and noble impulse a step beyond common sense into psychosis.” But that noble impulse—to treat animals fairly and to love and respect wildness—is one that has defined how people have viewed wild horses ever since. The instinct that drove Litts is the same one that drove people to later pass laws to protect mustangs. It is the instinct that shut down all horse slaughterhouses in the country. It is the instinct now that drives advocates to file lawsuits and block roundups. Any management policy that dismisses this viewpoint as sentimental or unrealistic is a policy that is bound to fail. And as Litts’s story shows, it may fail violently.

There are still people like Frank Litts out there—likely many more than there were when he was arrested in 1925. One night in 1997, after media reports revealed that the Bureau of Land Management was letting horses secretly go to slaughter, an anonymous group calling itself the Animal Liberation Front sneaked into a BLM corral complex near Burns, Oregon, and set fire to a barn and a tractor. The activists blocked entrances, so fire trucks couldn’t approach, and freed almost five hundred horses. They likely had never heard of Frank Litts, but they were his unwitting comrades. According to a communiqué they later released, they did it to “help halt the BLM’s illegal and immoral business of rounding up wild horses from public lands and funneling them to slaughter.” That same year, the group burned down a horse slaughterhouse in Redmond, Oregon. The plant never reopened.

One night in the summer of 2001, Animal Liberation Front members sneaked into the BLM’s big corrals in Litchfield, California, and planted firebombs in the barn, the office, and two trucks. Once again, they cut the fences to free hundreds of captured mustangs. The group released a statement saying, “In the name of all that is wild we will continue to target industries and organizations that seek to profit by destroying the Earth.”

Several members of the group were eventually caught and prosecuted under federal terrorism laws, but the BLM continues its roundups, knowing that the threat of a new Frank Litts or Animal Liberation Front is an ever-present danger. In 2008, in minutes of confidential meetings about what to do with “excess” horses, the BLM explored euthanizing them or selling them for slaughter. While the move would be legal, staff said, it could lead to “threats to BLM property and BLM staff.” After considering the risks, they quietly backed off.