In 1832, a dusty group of scouts and trappers gathered in the humble glow of a campfire out in the boundless night of the western prairie. They had trekked for weeks upriver into what would one day be Oklahoma but was still at that point simply marked on maps as “Indian country.” Gathered in the light of the fire, they sat talking idly, propped against their saddles as they chewed on buffalo ribs.

In the circle sat one of the most famous writers of the time, a forty-nine-year-old Manhattanite named Washington Irving. By 1832, Irving had established his literary reputation with popular tales like The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle, and had spent years living in Paris and London. A well-connected aristocrat, he had talked his way onto an expedition into Indian Country led by the Secretary of Indian Affairs. The group had been traveling west among the warring Horse Nations of the plains, who at the time were at the peak of their mustang-fueled expansion. Wild horses had brought wealth but also near-constant warfare as tribes tried to gain hunting grounds. Stopping to meet with each tribe they encountered, the secretary would give a speech, according to Irving’s later account, saying it was the intention of “their father at Washington to put an end to all war among his red children; and assure them that he was sent to the frontier to establish a universal peace.” (One group of Osage warriors responded that if the great father was really going to impose peace, they had better get moving, because they had many horses to steal.1)

Around the fire that night, Irving raised the subject of mustangs. He had spied one for the first time that day while riding across the plains. At first his party thought it was a buffalo, and gave chase, but the animal wheeled and galloped, throwing its mane like a horse. The cavalrymen charged off after it, but the horse turned and ran, too fleet to catch.

Irving watched it go, “ample mane and tail streaming in the wind,” he wrote later in his book A Tour on the Prairies. “He paused in the open field beyond, glanced back at us again, with a beautiful bend of the neck, snuffed the air, then tossing his head again, broke into a gallop.” He added: “It was the first time I had ever seen a horse scouring his native wilderness in all the pride and freedom of his nature. How different from the poor, mutilated, harnessed, checked, reined-up victim of luxury, caprice, and avarice, in our cities!”2

Irving’s fascination for the animal hinted at the power the mustang would come to have in the American mind—a power that only grew stronger as the great herds were slaughtered and the country grew more urbanized. Even in Irving’s time, when most of the continent was still wild, the mustang evoked freedom and defiance—an antidote to the woes of city life.

By the campfire that night, after Irving told the other men about spotting the mustang, the men started offering their own stories. There was an especially good one about a legendary mustang that no one could catch: the White Stallion. All the men who had spent any time in the West had heard of him, and some claimed to have seen him. Each man around the fire began offering what he knew about the glorious animal, interrupting one another to pile on their own details. The stallion was faster than any horse in existence. Instead of galloping, he paced. But with his long, muscled legs, his walking gait could still outdistance any pursuer. For years, men had tried to catch him. The best ropers could not get close enough to throw a lariat. Seasoned mustangers had set traps, but the stallion was too smart to enter. They tried to snare him at water holes, corner him in canyons, chase him off cliffs, lure him with the most beautiful mares, but every time, just as it seemed he was finally caught, he slipped away.

Irving jotted notes on these stories in his journal. Though he did not know it at the time, he was recording the first-ever written account of the myth of the mustang that would be repeated for more than a century.

The legend of the White Stallion was told in uncounted variations as long as the free and open West existed. And it often grew in the telling. He was tall and noble. Some said he was stark white, others who swore they had seen him said that he had a touch of gray, or black ears. His head and neck were unmistakably Arabian, some said. Others said he was pure Spanish Barb. His mane was like spun silk. It glowed like moonlight. Some called him the White Steed of the Prairies. Some called him the Ghost Horse. Some said he was the devil disguised as a mustang. Some compared him to a god.

He inevitably roamed the most open, wild, far-flung places. Some said he frequented the staked plains in the panhandle of Oklahoma. Some said he ran near the mesas on the Wyoming/Colorado border. Some said he haunted the deserts of the Texas border country, or the upper reaches of the Columbia River west of the Rockies.

He was always spotted on the horizon, tossing his head in defiance. But try to pursue him and you were sure to come back empty-handed, if you came back at all. Men in three relays with packs of hounds chased him across Texas. The best mustanger in the Brazos country set snares near his favorite shade trees. Some hunters tried to catch him in springtime when he was weak, or by the water hole when he was heavy after a long drink. But no rope ever touched him.

A doctor in San Antonio offered $500 for the stallion’s capture, one story goes. Some say it was actually P. T. Barnum who made the offer, and the price was $5,000. No matter. It couldn’t be done. One group of Blackfoot warriors trapped the stallion in a corral, only to have him leap the seven-foot fence. Some say a group of soldiers, after chasing him eighty miles, were sure they shot him dead along the Llano River, but the next day he returned to his favorite water hole. Another cowboy chased him through a storm near midnight out in the cliffs of the Cimarron country. After hours of pursuit, he cornered the stallion on a cliff a hundred feet above a rocky gully. The stallion, unwilling to surrender, leapt into the void. The next morning, the cowboy came back to look for the body, but the horse was gone.

In a few cases, the White Stallion led to the pursuers’ downfall. Two gamblers named Wild Jake and Kentuck are said to have set out from Santa Fe in the 1850s, determined to either return to the town riding the legendary stallion or “pursue him until the great prairies were swept by the fires of the Day of Judgment.”3 Dodging Indians and living off buffalo, they searched for weeks without a sign of the mustang. The longer they searched, the more they were consumed by obsession. Talk of the wild steed was always on Jake’s lips, and Kentuck could even hear him muttering about it in his sleep.

The weeks stretched into months. Winter was drawing near. Kentuck started to wonder whether they should turn back to Santa Fe, but Jake would only snap back that he aimed to find that horse or keep looking until the Day of Judgment. Finally, on a stormy night on the plains, they spotted him—standing only 100 yards ahead in the moonlight, a glowing white beauty of perfect proportions.

They charged as though the whole Comanche nation was pursuing them. But the horse paced away, gliding noiselessly into the darkness. No matter how hard they rode, they never got closer. After hours of chase, Kentuck yelled to Jake to stop. They should go back, he urged, it was no use.

In the moonlight, Jake turned and looked at Kentuck with a maniacal grin. His hat had fallen off and his long hair dangled around his darting eyes. His lips had a thin foam and a hint of blood where he had bitten them. “I’ll follow him—yes—to the Day of Judgment.” Jake sped off after the horse, not seeing a cliff ahead of him. Kentuck watched Jake sail into the canyon below, calling as he fell, “’Till the Day of Judgment!”4

In a way, the White Stallion is just another larger-than-life folk hero like Paul Bunyan or Pecos Bill—a way to spin a mythical yarn that was a variation on a theme: How is the horse going to get away this time? But it represents much more. We never made a national symbol out of Paul Bunyan. He is the story of power. The wild horse is the story of independence.

The White Stallion made it into a number of best-selling accounts of adventures out West, including Irving’s, and soaked into the literary Zeitgeist of the country. It became the basis of Herman Melville’s whaling classic, Moby-Dick—a story of the maniacal pursuit of a legendary white beast that could not be caught.

Melville—who, like Irving, grew up in New York City—likely heard the tale of the white horse as a young author, either through accounts of frontier yarns that appeared in popular magazines at the time or through the book-length sagas of Irving and another literary explorer, George Wilkins Kendall, who published an account of exploring the area in 1844. He probably also took inspiration from the tall tales of a white whale said to have escaped more than a hundred encounters with whalers off the coast of Chile. And the stories of the white whale and the White Stallion, which both emerged from groups of explorers in the early nineteenth century, may have the same root in the era’s yearning to explore and subdue. In any case, Melville makes it quite clear in Moby-Dick that he had given a great deal of thought to the horse before writing.

“Most famous in our Western annals and Indian traditions is that of the White Steed of the Prairies,” he wrote in a chapter about the whale’s “whiteness”:

A magnificent milk-white charger, large-eyed, small-headed, bluff-chested, and with the dignity of a thousand monarchs in his lofty, overscorning carriage. He was the elected Xerxes of vast herds of wild horses, whose pastures in those days were only fenced by the Rocky Mountains and the Alleghenies. At their flaming head he westward trooped it like that chosen star which every evening leads on the hosts of light. The flashing cascade of his mane, the curving comet of his tail, invested him with housings more resplendent than gold and silver-beaters could have furnished him. A most imperial and archangelical apparition of that unfallen, western world, which to the eyes of the old trappers and hunters revived the glories of those primeval times when Adam walked majestic as a god, bluff-browed and fearless as this mighty steed.5

The folklorist Frank Dobie spent decades tracking every reference to the legend of the White Stallion and eventually gave up, finding that there were simply too many, and the “Zane Grey assembly line and pulp magazines have published stories on the horse without end.”6 The myth changed and grew over time as other writers and other generations added their own takes, but in the nearly two hundred years since, it has remained essentially the same: The mustang is always pursued by man, and always gets away. He is proud and regal and prizes freedom above all else, including his own life. He stands as a proof that some things can never be had. Despite the many industrious plans of man, there is a certain wild nobility that can’t be captured. This is an idea so linked to wild horses that most Americans know it, even if they know nothing about the myth of the White Stallion, and it has resonated through the generations because it expresses an idea that runs deep in the country’s identity.

There is no other animal in America that we have heaped with so much meaning. Though the bald eagle is the country’s official symbol, it isn’t as American as the mustang. The eagle is too regal and aloof—a symbol of federal power but not of American grit. Besides, the bald eagle is known for stealing fish from other birds, which prompted Benjamin Franklin to call it a bird of “bad moral character.” The mustang, on the other hand, embodies the core ideals of America. It is not pedigreed. It has no stature. Instead, it derives its nobility from the simple toughness of its upbringing in a free and open land. It is beholden to no one. It will not be subjugated. It is superior to its domestic brethren because it has the one thing Americans say they yearn for most: freedom. It is the hoofed version of Jeffersonian democracy.

Why the mustang? When the experience of settling North America produced such a menagerie of animal characters—the mule, the oxen, the longhorn, the sheep, the herding dog—why was it only the wild horse that crossed into legend? Why was the story of the White Stallion told and retold, and heaped with so much meaning?

To try to answer these questions, I made my way, one muggy July morning, down a winding road on the Lackawaxen River in the mountains of northeastern Pennsylvania, where everything was a wall of green—lush and still and close. The Appalachian forest leaned so far over the narrow road along the river that only a few palm-size patches of sun hit the pavement. The thick smell of breathing trees and aging leaves hung on the breeze.

I pulled my car up to a spot where the lacy riffles of the Lackawaxen emptied into the broad, smooth Delaware River at a place called Cottage Point. It could not have been farther from the vast, dry vistas of Wild Horse Country. There were no long views or mesas, no cactus or sage. That morning, a steady stream of candy-colored kayaks drifted by, slowly turning in the glassy emerald water under galaxies of flies and midges that glowed in the early light. But on a small rise on the riverbank stood a two-story white-clapboard farmhouse with dark green shutters and a broad front porch opening on the river that is so tightly bound to the legend of wild horses in America that you can’t understand what has happened in the West unless you look at what happened in this quiet house in the East.

I pushed open the oak front door, stepped through the parlor, and walked down the creaky wood hall of the farmhouse. The last door on the left revealed a spacious study. Its walls were covered with Navajo weavings and paintings of Hopi Kachinas. The bookshelves were filled with the adventure tales of James Fenimore Cooper and Rudyard Kipling. And in one corner, near the woodstove, stood a broad armchair with a maple lapboard still leaning against it. Here one of the best-selling Western authors of all time, Zane Grey, spent eight hours a day penning pulp novels.

If the pueblos of New Mexico are the place that set wild horses free on the West, then this quiet spot in the Appalachian Mountains is the place that set free the icon. Grey helped build the myth of the West from campfire stories into an industry. Along the way, he, more than anyone else, molded the wild horse into an enduring American legend. The riders of the purple sage, the damsel in distress, the lowborn cowboy with a strong moral code. The noble mustang that will only submit to the hero, and, despite a lack of pedigree and a fiery temper, is the best horse under the sun—these are all stereotypes popularized by Grey. One film critic called Westerns the Genesis and Exodus of the American story. Grey’s stories and thousands others like them glorified the Western hero and the idealized Western code of honor as a way of explaining our origins to ourselves.

Grey didn’t invent the Western genre or the legend of the wild horse. Instead, he was the myth’s Henry Ford. His genius was in designing an attractive, streamlined, accessible product for the masses. Like an assembly line, he was constantly churning out books: The Last of the Plainsmen, The Heritage of the Desert, Riders of the Purple Sage, Spirit of the Border, The Last Trail, Wanderer of the Wasteland, The Thundering Herd. Through simple language, vivid scenery and characters, and sheer output, he modernized, mechanized, marketed, and democratized a myth so powerful that, in a big way, it became a key chapter in the story we tell about ourselves as a nation. In a writing career spanning thirty-six years, he published more than forty books. When he died in 1939, his publisher noted he had sold seventeen million copies, outselling every book but the Bible, and calling him “the greatest selling author of all time.” He has since sold more than twenty million more. You can find copies in nearly every library and bookstore. They were made into magazines, comics, radio plays, and more than 110 movies and television episodes. They inspired countless other Westerns and anti-Westerns. The Lone Ranger and his horse Silver, Randolph Scott in a white hat, Gary Cooper with his six-shooter, John Wayne riding shotgun—all the most famous tall, silent archetypes got their start in stories thought up by Grey. And the myth he popularized led to the law that now protects wild horses.

Myths live in the mind, not on the land. And where the myth of the West really took root was not in the West but in the East, where a handful of men like Irving and Grey—almost all of them wealthy men in New York City—turned the herds of galloping mustangs into something more than just horses. Through dime novels, pulp fiction, stage shows, and eventually Hollywood movies, they made the mustang an indelible part of the myth of America, forever linked to a set of ideals: quiet toughness, steadfast loyalty, plainspoken common sense, an insistence on independence, the pursuit of certain inalienable rights endowed by the Creator.

Sure, most Westerns were idealized parodies of the West written for eastern audiences, and they offered a message often designed to resonate with the quiet desperation of urban lives. But Grey appeared to be aware of this, and comfortable with it. When I walked into the old farmhouse in Lackawaxen, Pennsylvania, which is now a museum run by the National Park Service, I was greeted by this quote from his 1921 novel To the Last Man: “In this materialistic age, this hard, practical, swift, greedy age of realism, it seems there is no place for writers of romance, no place for romance itself. I have loved the West for its vastness, its contrast its beauty and color and life, for its wildness and violence, and for the fact that I have seen how it developed great men and women who died unknown and unsung. Romance is only another name for idealism; and I contend that life without ideals is not worth living.”

Another quote on the wall read: “Realism is death to me. I cannot stand life as it is.”

As I read it, I thought about all the forgotten, yellowing newspaper clips from a century ago that I had tracked down to try to understand the long war between ranchers and horses. How obscure, and even beside the point, those snippets of fact seemed when compared to the story we tell now about the horse as a noble companion. The myth had more weight than the real history. I couldn’t help but remember the last scene of the classic 1962 movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Slumped back in an armchair, a three-term governor of a Western state finally reveals the truth: He had built his career on a reputation for having killed a no-good outlaw, but, in fact, he had never shot the man at all. On hearing this, a newspaperman interviewing the governor rips up his notepad.

“You’re not going to use the story?” the governor asks.

“No, sir,” the newspaperman says. “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Myth always tries to find meaning in the past, and, in the process, it often discards many of the facts. A lot of the legend of the West that we now carry in our popular imagination was never true, including aspects of the story of wild horses, but at this point there is so much cultural heft behind it that it hardly matters.

To find resonance, every myth has to have some foundation in reality. As generations shaped the myth of the wild horse, it slowly changed from one of majestic wildness to one of noble and willing servitude—reflecting changes in the country itself. The men sitting around the campfire with Washington Irving in the 1830s, and the cowpunchers and trappers who came after them, had all left civilization to try to make it in the West. The leagues of endless grass, uncut forests, and tumbling mountain rivers appeared to offer resources without end, but a man had to figure out how to seize them and make them his own. They knew well the raw power of the land and its nobility. In a way, their telling and retelling the story of the White Stallion pacing away was a sign of respect for their place in the West. They admired the land and the bounty it could produce. They pursued its riches, but ultimately they knew they could not possess the one thing they loved most about it: the wildness.

Of course, the West changed, and, as it did, so did the myth of the wild horse. Railroads cut the plains into pieces; the buffalo and the Horse Nations both were nearly eradicated. Barbed wire was patented in 1874 and rolled out across the West. The stories told about the White Stallion changed too.

Frank Dobie made a habit of talking to old-timers who had ridden the range back in the 1870s and 1880s. He observed that as the West was settled, the story of the White Stallion slowly changed from a stallion that couldn’t be caught to a stallion that couldn’t be tamed. It would choose death over subjugation. Live free or die. Some men told Dobie the stallion was eventually shot by a group of frustrated cowboys. Some said he was chased ten days and finally caught in the desert hills near Phoenix by a bunch of ranch hands. They penned him in a high and sturdy corral, but he refused to eat or drink. No one was ever able to ride him. He died of starvation after ten days.

About the same time the White Stallion reportedly died, the Wild West pretty much rode into the sunset too. The last big cattle drives ended in 1886. Geronimo and his small band of Apaches surrendered the same year. The Horse Nations were defeated, their horses confiscated. For decades, the census had been marking the western march of the frontier, but in 1890, the Census Bureau said the frontier was gone. The country was now civilized.

In 1893, historian Frederick Jackson Turner, in a small lecture to other historians at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, announced that the period of westward expansion that had marked and molded the American psyche since the time of the Mayflower was over. In his “frontier thesis,” the thirty-two-year-old history professor said the frontier had been the defining feature of Americanness. The “Great West,” with its endless wild lands, had created the American identity: practical, inventive, egalitarian, fiercely independent, and distrustful of government. The values he was tying to the frontier were the same ones writers would give to the mustang.

“The frontier,” he told the audience, “is the line of most rapid and effective Americanization.” He continued: “Since the days when the fleet of Columbus sailed into the waters of the New World, America has been another name for opportunity, and the people of the United States have taken their tone from the incessant expansion which has not only been open but has even been forced upon them. . . . Each frontier did indeed furnish a new field of opportunity, a gate of escape from the bondage of the past; and freshness, and confidence, and scorn of older society, impatience of its restraints and its ideas, and indifference to its lessons.”7

In a way, though he did not know it, he was arguing that Americans were a lot like mustangs: European imports of various stations, who were defined not by their birth but by the freewheeling life they encountered in the West.

If the wild period of the frontier, when mustangs and Americans had been created, was ending, the myth was just getting its start. Across the street from where Professor Turner delivered his speech—a speech that largely went unnoticed at the time, and was only later recognized as one of the most significant lectures ever on American history—William “Buffalo Bill” Cody was putting on his Wild West Show to a daily audience of eighteen thousand. It was pure spectacle, the weaving of history into myth, right before the audience’s eyes. Riders on real mustangs reenacted the Pony Express days. Lakota warriors carrying bows and rifles played out the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Cody, who had been an explorer on the plains long enough to have heard the legends of the plains dozens of times, started every show by galloping into the arena astride a regal white stallion.

It was around this time that a myth of the mustang took a turn. In this new version, the mustang would submit to a man and become a willing servant—but only if the man’s heart was true. It is this version that has largely endured. In radio plays of The Lone Ranger generations later, the ranger’s white stallion, Silver, is wild and untamable until the ranger saves him from a buffalo attack. In gratitude, Silver becomes his companion.

The new myth got its start with dime novels about Buffalo Bill and other explorers. Buffalo Bill alone was the subject of more than 1,700 pulp novels. Often myth and reality worked side by side in ways that might strike even a reality TV producer as odd. Early on, Buffalo Bill, for example, was a scout in the West in the summers and played himself in musicals in Chicago in the winters. These early accounts were full of stories of tough mustangs and their incredible feats. Buffalo Bill told of riding one little Indian pony named Buckskin Joe nearly two hundred miles while being pursued by plains tribes. The horse never gave out, but he was so exhausted by the end that he went blind.

In a way, the new version of the wild horse myth, which made the horse into a noble companion, was a melding of the two myths. America had long championed noble adventurers like Daniel Boone and Natty “Leatherstocking” Bumppo. The horse had long symbolized the evasive nature of the wild. In the new myth, they were side by side. The mustang remained noble and independent but was willing to work with the right guy. It was Manifest Destiny, the wild yielding to American exceptionalism.

Zane Grey grew up reading th0se early dime novels. But he was in many ways an unlikely godfather of the Western myth. He was born Pearl Zane Grey in 1872 in Zanesville, Ohio, the son of a strict and often disapproving dentist. As a boy, Pearl, who maybe not surprisingly eventually started going by his middle name, devoured boys’ adventure books: James Fenimore Cooper’s tales of Leatherstocking, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, and the constant churn of dime novels featuring Western yarns about Buffalo Bill and Deadwood Dick. Grey’s study still contains volume after volume of these classic adventure books. Growing up, he loved the outdoors, baseball, and writing, but his father insisted he go into dentistry. By age sixteen, Grey was making rural house calls to pull teeth. A smart, athletic kid, he eventually won a baseball scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania, graduating with a dentistry degree in 1896. Soon afterward, he opened his own practice in New York City.

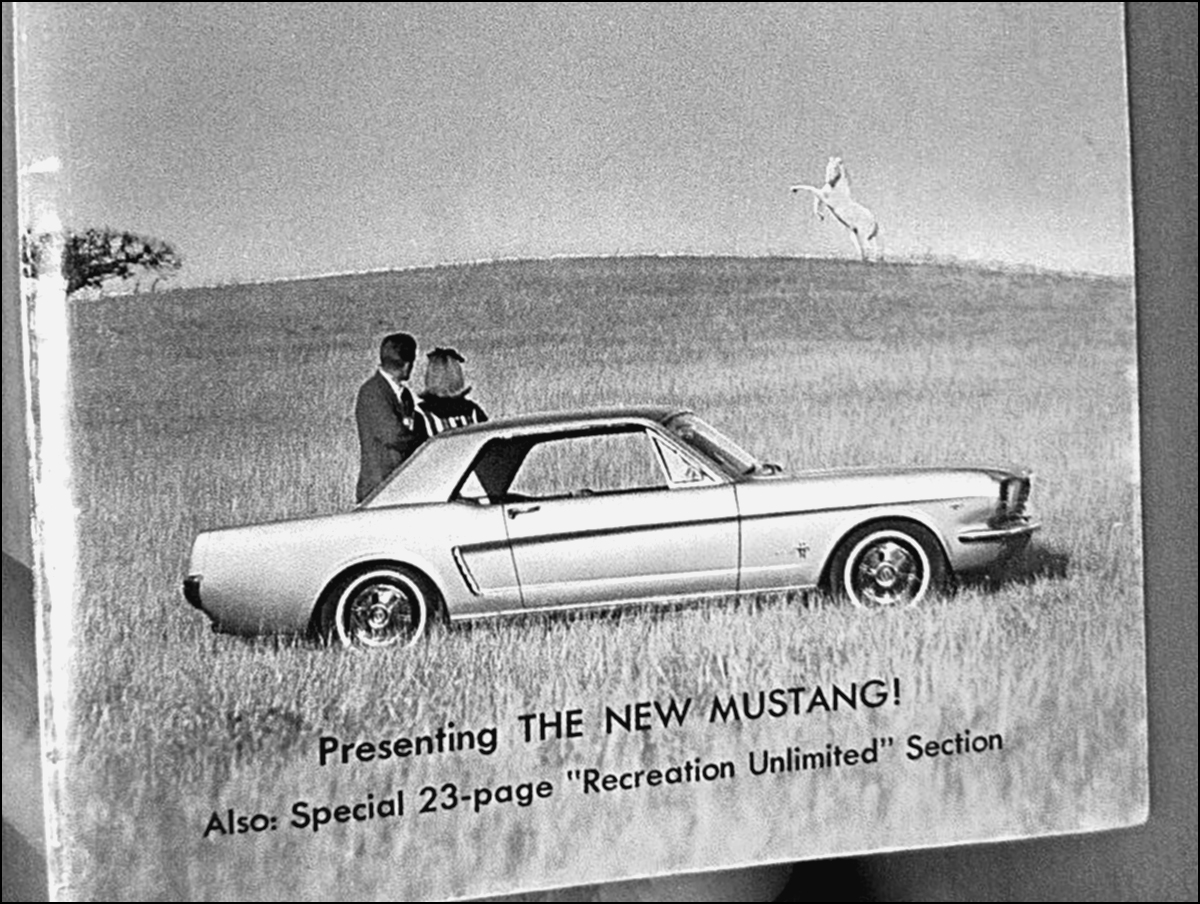

In his old farmhouse, the rooms are now filled with glass cases stocked with relics of Grey’s writing career: pristine first editions, journals, binoculars, fishing rods, and black-and-white photographs. A photo near the door shows him as a dentist—lean, taut, and broad-shouldered like an athlete, but yoked in a black suit and stiff paper collar. His costume is staid, his look is stern, but his eyes blaze under a deep, intense brow, making him look like a caged animal—a maniac desperate to escape.

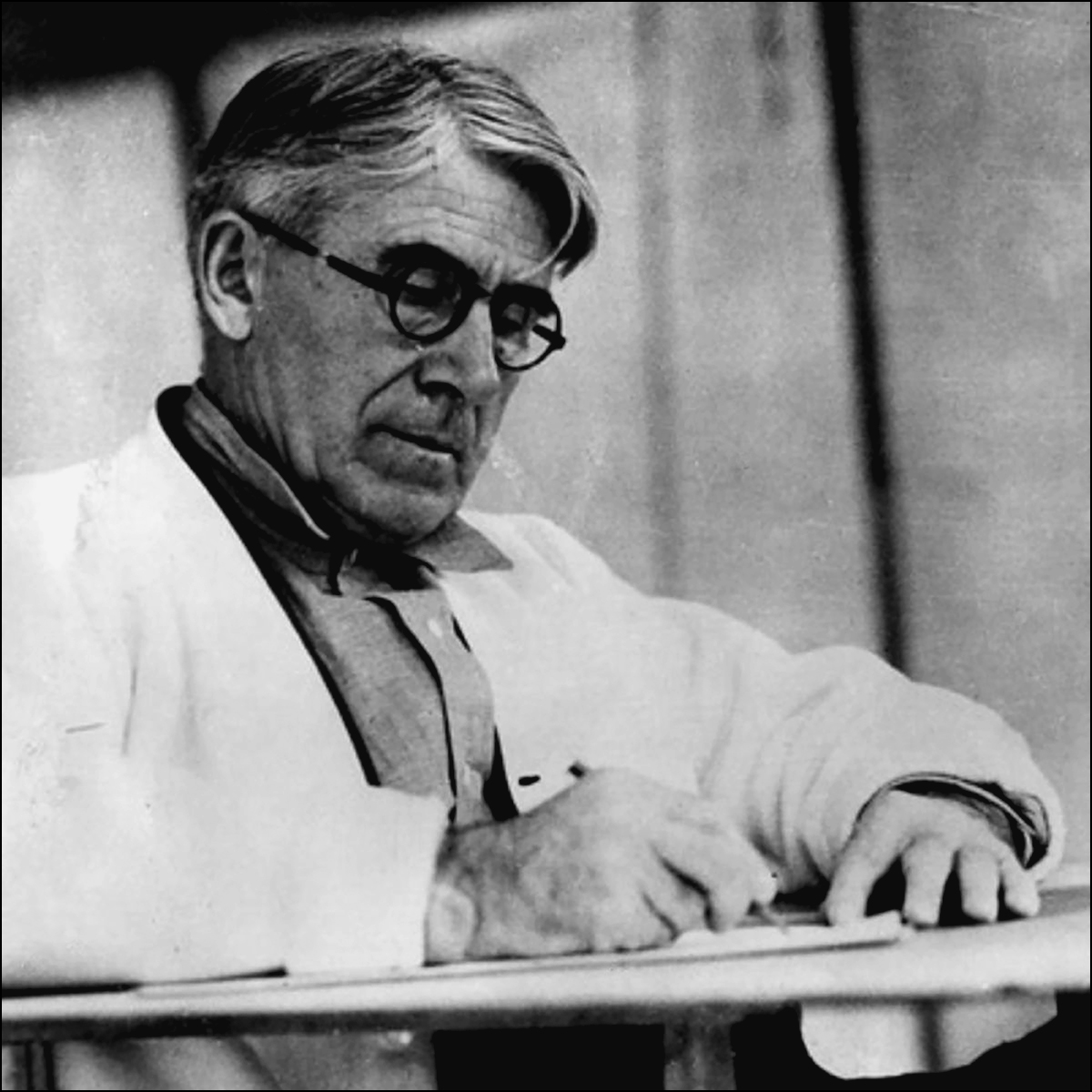

THE PROLIFIC NOVELIST ZANE GREY.

Throughout his life, Grey was stalked by what he called “black moods,” and he had an intensity and wildness that life as a dentist could not satiate. Only outdoor adventure seemed to lift his spirits. When his city life of pulling teeth became too much, Grey would often catch a train out of Penn Station to take fishing trips around Lackawaxen. He dreamed of one day leaving the city entirely to live out in the mountains, writing about his adventures. In 1900, while canoeing on the Delaware, he met a sharp and beautiful seventeen-year-old girl named Lina “Dolly” Roth and fell in love. They had a long courtship, writing letters back and forth as she finished college, and eventually married in 1905.

Dolly seemed to understand that her husband needed something beyond pulling teeth. She had a small inheritance and encouraged him to quit dentistry and follow his dream to move to a farmhouse on the bank of the Lackawaxen and become a writer.

“I need this wild life, this freedom,” he told her in a letter. “To be alive, to look into nature, and so into my soul.”8

By 1907, Grey was living on the Lackawaxen. He had quit dentistry and written an adventure novel about the Revolutionary War, but it was quickly rejected by New York publishers. He kept writing, scraping together something close to a living by penning articles here and there about fishing. That year, he attended a lecture in New York by a Buffalo Bill–type adventurer named Buffalo Jones—a longtime frontiersman who had rounded up some of the last buffalo and was trying to breed them at a ranch north of the Grand Canyon. Jones regaled the crowd with tales about hunting mountain lions and once lassoing an unruly bear. Intrigued, Grey pulled Jones aside after the lecture and asked to go with him to the Grand Canyon to write about his life. Jones agreed. They spent months traversing the wilds of northern Arizona—fording rivers, encountering gun-toting cowpokes, and hunting mountain lions. After the trip, Grey returned home and in the space of a few months wrote what would be his first Western, The Last of the Plainsmen.

His last chapter included his own retelling of the legend of the White Stallion.

“He can’t be ketched,” the Buffalo Jones character says. “We seen him an’ his band of blacks a few days ago, headin’ fer a water-hole down where Nail Canyon runs into Kanab Canyon. He’s so cunnin’ he’ll never water at any of our trap corrals. An’ we believe he can go without water fer two weeks, unless mebbe he has a secret hole we’ve never trailed him to. . . . He never makes a mistake. Mebbe you’ll get to see him cum by like a white streak. Why, I’ve heerd thet mustang’s hoofs ring like bells on the rocks a mile away. His hoofs are harder’n any iron shoe as was ever made.”9

The book ends with the cowboys coursing down a dead-end box canyon at a full gallop, sure that there is no way the stallion can escape. He does.

After The Last of the Plainsmen, Grey almost immediately headed back west in search of more stories. Though he was gone for long periods of time, his wife encouraged him, knowing that adventure was one of the few cures for his depression. Writing in longhand in his study back in Lackawaxen, Grey began turning out one hit novel after another: The Heritage of the Desert, Riders of the Purple Sage, The Lone Star Ranger. He was on the best-seller list every year for the next decade.

The books coined the idea of the Western hero who was honest, steadfast, and loyal. Ironically, Grey was anything but. Most notably, he had an unquenchable appetite for sex. At sixteen, he’d been arrested in a brothel. A few years later, he was the subject of a paternity suit. He kept sleeping with other women throughout his courtship with Dolly, and he slept with even more women after they married. Fame only fueled his exploits. For his whole writing life, he traveled with a series of “secretaries” and “nieces”—sometimes as many as four at a time—keeping journals (written in code) of his sexual encounters.

“A pair of dark blue eyes makes me a tiger,” he once wrote. “I love, I love my wife, yet such iron I am that there is no change.”10 In a way, by creating characters driven by honesty, loyalty, and trust, he was expressing a life he wished he could live.

If the myth of the White Stallion had originated with men in the West, who were intimately familiar with the power of the western landscape, the myth of the horse as noble companion, which endures today, was one devised in the East, generally by men like Grey, who yearned to be free in the West but were instead entangled in eastern society.

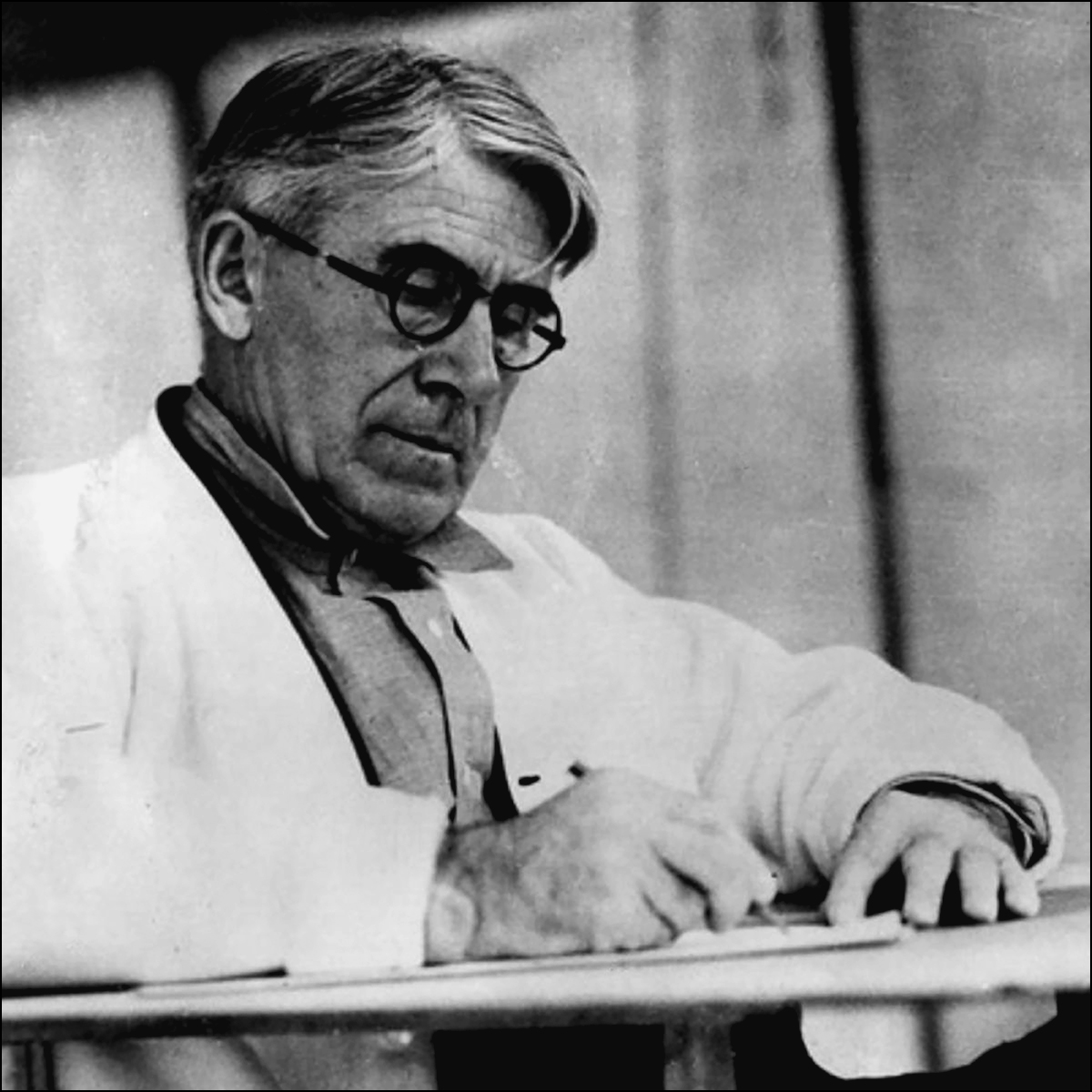

At first, the heroes of the myth were all explorers, but they were eventually replaced by a more blue-collar hero, the cowboy. For that, we can thank a not very blue-collar eastern blueblood named Owen Wister, who in 1902 published what is often called the first Western novel, The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains.

Wister was an even odder choice as father of the Western than Zane Grey. He grew up the privileged son of a doctor and a southern lady whose family had owned hundreds of slaves before the Civil War. He attended the best boarding schools in Switzerland and New England, then graduated from Harvard. In school he excelled at music and theater, and he wanted to become a composer, but his father pushed him into a desk job at a Philadelphia bank. It didn’t take long for Wister to suffer a nervous breakdown. In 1885, a doctor recommended that the best way to recuperate was to go west. Stepping off the train in Wyoming a few weeks later, he encountered the plain-talking ranch hands who inspired the cowboy archetype. Like the wild horse, the man was defined by the freedom of the place, not his lineage.

“The grim long-haired type,” he called them. Ones that “wore their pistols, and rode gallantly, and out of them nature and simplicity did undoubtedly forge manlier, cleaner men than what our streets breed of no worse material. . . . They developed heartiness and honesty in virtue and in vice alike. Their evil deeds were not of the sneaking kind, but had always the saving grace of courage. Their code had no place for the man who steals a pocket-book or stabs in the back.”11

That is an interesting idea, because Wister was, among other things, a first-class, Gilded Age bigot. He laid out his feelings clearly in an 1895 essay for Harper’s magazine called “The Evolution of the Cow-Puncher,” which became the blueprint for his version of the cowboy myth. He believed, first off, that the West only worked its magic on Anglo-Saxons. He saw Philadelphia, and America as a whole, as being a flagging “compound of new hotels, electric lights, and invincible ignorance,” infested with Catholics, Jews, and immigrants. Or, as he called them, “hordes of encroaching alien vermin, that turn our cities to Babels and our citizenship to a hybrid farce, who degrade our commonwealth from a nation into something half pawn-shop, half broker’s office.”12

THE NOVELIST OWEN WISTER, AUTHOR OF THE VIRGINIAN.

Democracy was falling apart, he contended. But his visits to the West had inspired him, because out there he had encountered, he said, the most noble breed of man in his natural setting: the rural Anglo-Saxon. He believed the Anglo-Saxon, dropped into the raw, wild West, free of the mongrel horde, reawakened a natural superiority that had been present in Viking warriors, the knights of Camelot, the other brave explorers of yore, but had gone dormant in his deskbound generation. He wrote:

Watching for Indians, guarding huge herds at night, chasing cattle, wild as deer, over rocks and counties, sleeping in the dust and waking in the snow, cooking in the open, swimming the swollen rivers. Such gymnasium for mind and body develops a like pattern in the unlike. Thus, late in the nineteenth century, was the race once again subjected to battles and darkness, rain and shine, to the fierceness and generosity of the desert. Destiny tried her latest experiment upon the Saxon, and plucking him from the library, the haystack, and the gutter, set him upon his horse; then it was that, face to face with the eternal simplicity of death, his modern guise fell away and showed once again the mediaeval man. It was no new type, no product of the frontier, but just the original kernel of the nut with the shell broken.13

This was only true of Anglo-Saxons, he observed. “To survive in the clean cattle country requires spirit of adventure, courage, and self-sufficiency; you will not find many Poles or Huns or Russian Jews.”14

A crucial ingredient, he said, was the horse—specifically, the cow pony, or mustang, or Cayuse—the wild horse of the West:

A few words about this horse—the horse of the plains. Whether or not his forefathers looked on when Montezuma fell, they certainly hailed from Spain. And whether it was missionaries or thieves who carried them northward from Mexico, until the Sioux heard of the new animal, certain it also is that this pony ran wild for a century or two, either alone or with various red-skinned owners; and as he gathered the sundry experiences of war and peace, of being stolen, and of being abandoned in the snow at inconvenient distances from home, of being ridden by two women and a baby at once, and of being eaten by a bear, his wide range of contretemps brought him a wit sharper than the street Arab’s, and an attitude towards life more blasé than in the united capitals of Europe. I have frequently caught him watching me with an eye of such sardonic depreciation that I felt it quite vain to attempt any hiding from him of my incompetence; and as for surprising him, a locomotive cannot do it, for I have tried this.15

In the West, both man and horse had undergone renewal, he argued. And like steel and flint, or bow and arrow, the man needed the horse and the horse needed the man: “Deprive the Saxon of his horse, and put him to forest-clearing or in a counting-house for a couple of generations, and you may pass him by without ever seeing that his legs are designed for the gripping of saddles.”16

Wister wrote several short stories on this theme, culminating in The Virginian, his only full-length Western novel, about a nameless ranch hand in Wyoming, which announced to the world the archetype of the lowborn natural aristocrat cowboy hero that is still in broad circulation today:

His broad, soft hat was pushed back; a loose-knotted, dull-scarlet handkerchief sagged from his throat; and one casual thumb was hooked in the cartridge-belt that slanted across his hips. He had plainly come many miles from somewhere across the vast horizon, as the dust upon him showed. His boots were white with it. His over-alls were gray with it. The weather-beaten bloom of his face shone through it duskily, as the ripe peaches look upon their trees in a dry season. But no dinginess of travel or shabbiness of attire could tarnish the splendor that radiated from his youth and strength.17

Of course the Virginian rode a mustang. His name was Buck.

The gunslinging and galloping adventures made The Virginian—a yearning Easterner’s portrait of time past—a best seller. The strong, silent drifter, an unlikely Sir Galahad of the plains, would live on with Grey and a crowd of other imitators. Grey studied The Virginian before writing his first book. Other writers, in turn, saw Grey’s success and copied him. Fred Faust, a Berkeley dropout, aspiring poet, and practiced alcoholic in Manhattan, writing under the name Max Brand, churned out scores of Western pulp novels in the 1920s and 1930s with names like Riders of the Silences, The Untamed, and The Night Horseman. Ernest Haycox, a beat reporter at the newspaper in Portland, Oregon, in the 1920s, was also inspired by Grey’s work, and a steady stream of titles followed: Starlight Rider, Riders West, Man in the Saddle, The Wild Bunch.

There were many, many more imitators. Westerns dominated nearly every medium for the next fifty years. The action-packed stories naturally translated into movies and radio. In 1925, Douglas Fairbanks starred in a silent film based on Grey’s 1928 book Wild Horse Mesa, about a rancher, desperate for money, who tries to trap and sell wild horses but is stopped by the hero and a wily White Stallion. After that box office success, more than a hundred films were made from Grey’s work. Hundreds more were inspired by the writers who followed him. By 1950, the golden age of the genre, Westerns outnumbered all other movie categories combined.

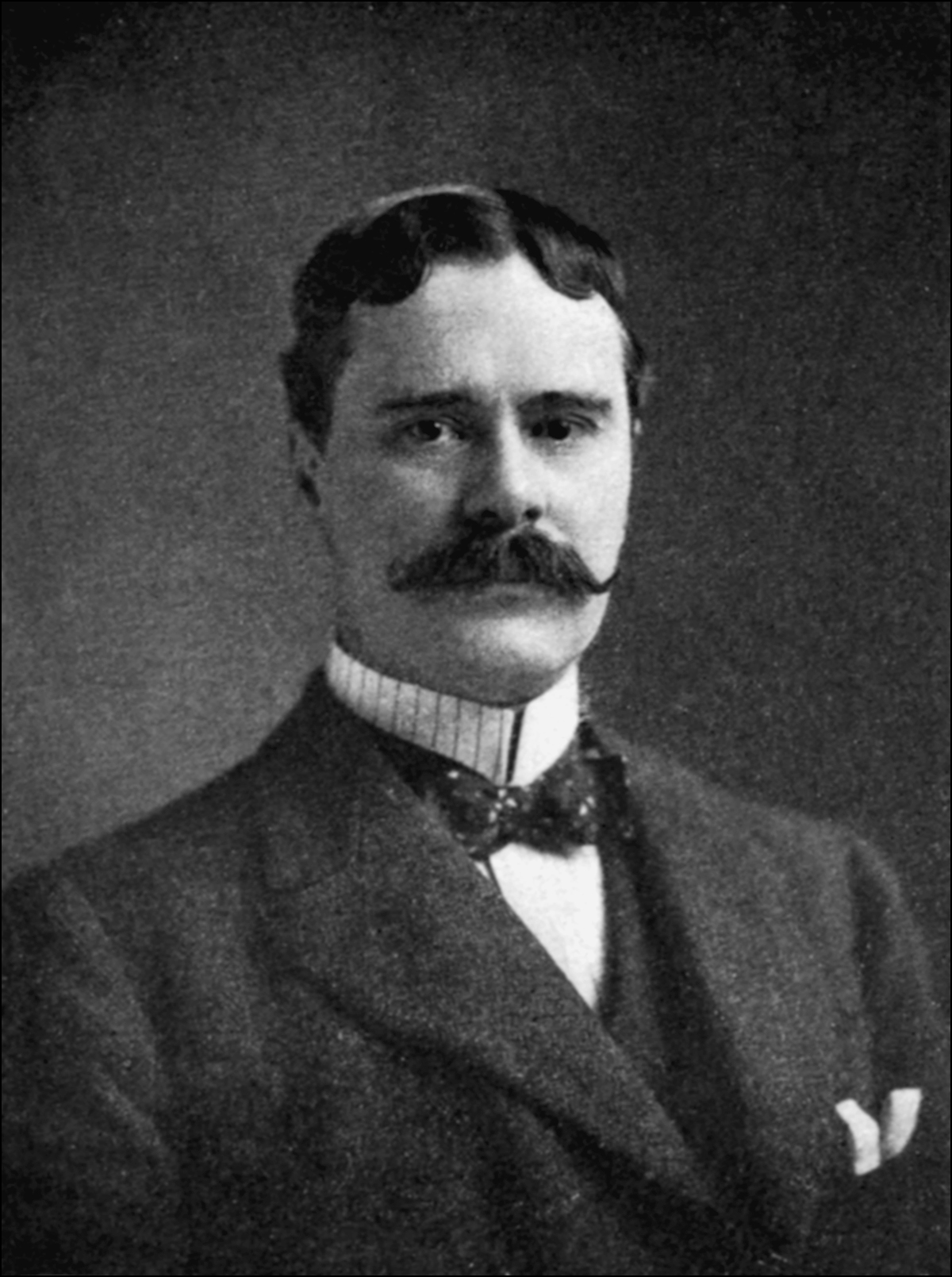

You can see the reach of the myth as it percolated into the rest of America. During World War II, when the Americans developed a tough little one-seater fighter plane that could cover long distances at high speeds, they called it the P-51 Mustang. In 1964, when Ford came out with a little two-seater with surprising power and affordability, a marketing manager who had just read a J. Frank Dobie book suggested The Mustang. At the time, more than stories of the Revolution or the building of cities or the digging of canals, mustangs and the cowboy myth were a way we explained our origins and connected ourselves to the past. Even if it was a past that never was.

ONE OF THE FIRST ADS TO INTRODUCE THE FORD MUSTANG PLAYED ON THE MYTH OF THE WHITE STALLION.

After several best sellers, Zane Grey moved from his farmhouse in Pennsylvania to California in 1918. He continued to write feverishly, but he also pressed farther and farther from civilization, looking for adventure. He descended rivers in Mexico, hunting for new fishing grounds. He bought a $250,000 yacht and traveled first to the Galapagos, then out into the South Pacific, where he spent months fishing and became a real-life Captain Ahab as he nearly pushed his crew to mutiny in the hunt to land a world-record marlin. He continued to pursue new women, even while keeping up a relationship with his wife, who reliably, if rarely happily, put up with his affairs and managed the business side of his writing, often signing her letters, “Your wife, in name only.”

As I walked through the rooms of Zane Grey’s house, looking at carefully labeled fishing rods, camp stoves, and canteens, I couldn’t help but feel a little sorry for him. Grey had been born wild and spent the rest of his life trying to break free of a world that was increasingly haltered. He was constantly pushing himself to run farther, to experience more, to bite into life deeply and drink the juices. That is a hard thing to live with for a lifetime. But at the same time I admired him. That constant itch had made him disregard the comfortable life given to him and really live. He wandered the globe drinking life to the lees, hunted mountain lions on canyon rims, and rode mustangs through desert valleys. He spread a cowboy mythology that is still with us. He lived a life of wildness. How long would he have lasted if he had stayed a dentist?

I doubt Grey thought much about the impact of his stories beyond his own life, but the people who grew up with the myth he helped spread are the people who, as adults, passed the 1971 law protecting wild horses. Would it have happened at any other time, with a population that wasn’t raised with the stories of the Noble Mustang and the White Stallion? I have my doubts.

In the house at Cottage Point, the National Park Service had a volunteer docent working the front desk. He looked to be about sixteen, and the sleeves on his short-sleeved shirt hung down past his elbows. He was probably too young to have had much exposure to the cowboy myth. Baby boomers grew up saturated in cowboys: TV, radio, the movies, toys. I was born in the 1970s. By that time, all the heroes on the screen were mostly in space. Westerns were complex, full of anti-heroes, and no more trusty mustangs. The faithful mustang had morphed into R2-D2 in an X-wing fighter. With younger generations, cowboys are even more obscure. Few people anymore know the story of the White Stallion.

There was no one else in the museum, so I went up and asked the volunteer to name his favorite Zane Grey book. He paused, mouth half open, then said, “I’ve never really read his books.”

He explained that he was volunteering not because he had a huge affinity with the author but because he lived nearby. The few people who drifted in and out during my visit all appeared to be in their seventies—people who were young parents when the 1971 law passed. I wondered what the younger generations, who had not grown up surrounded by Zane Grey–style Westerns, thought of wild horses.

I told the volunteer I was writing about wild horses, and I thought Grey was a pivotal part of why they still existed. He nodded in the way kids do when they are old enough to realize that all adults are really weird.

“Wild horses,” he muttered. “Are they still around?”