In the spring of 1950, a thirty-eight-year-old secretary named Velma Bronn Johnston was driving to work at an insurance company in Reno. Cigarette in hand, smoke curling out of the window in the early morning light, she sped down a gravel road through a rocky desert valley in Nevada where a green patchwork of small ranches clung to the Truckee River. The road snaked along the water, following almost every bend, but Velma knew the turns well from weekly trips between the sixteen-acre hobby ranch where she lived with her husband, three horses, and two cocker spaniels on the weekends, and Reno, where she lived and worked the rest of the week.

If there is a rugged, rural type of person most people would expect to live in a desert valley in Nevada, Velma Johnston was not it. She was well read and well spoken, with none of the Texas twang that in recent years became an affect of many rural westerners. She wore heels, not boots, and painted her nails to a flawless pearl sheen. She was also jarringly disfigured—the result of a childhood bout with polio that left her back twisted and the left side of her face askew like a Picasso portrait. But her looks had never deterred her. She was confident, smart, and determined to be the best secretary any boss had ever had.

After a few miles of bumpy dirt road, she turned onto the paved road to Reno. The city was thirty miles away, through a pass in the Virginia Mountains, and she put the pedal down to make time. It was normally open road that early in the day. Reno only had forty thousand people, and the Great Basin in her rearview mirror was almost entirely unpopulated. Traffic was never a problem. But not long after turning onto the highway, she came up behind an old stock truck rolling slowly alongside the river. Its bed had high wooden-slat sides and a canvas roof. She could tell by the way it swayed and sagged that it was fully loaded. Johnston, in a hurry to get to work, came up close behind it. The highway between her ranch and Reno was winding, and there was no easy place to pass, so she was forced to stare in frustration at the back of the tottering truck.

She noticed something glistening on the back bumper. It was dark, like oil. As she got closer, she realized it was blood. There was a steady dribble leaking out of the truck bed and dripping off the bumper.

Johnston stayed behind the truck, studying the blood. What was in the back of the truck that was bleeding—was it an injured cow or sheep? Certainly the rancher driving would want to know, she thought, and she decided to alert him as soon as she could.

The flow of blood increased as the truck rolled down the highway. By the outskirts of Reno, it was a constant stream. The truck pulled off at the stockyards in Sparks, Nevada, and Johnston followed. When the truck parked, she went up to peer through the slats. What she saw stole her breath. The bed was packed full of mustangs, many of them bleeding from wounds as though they had been blasted with shotguns, others bleeding from torn hooves. One stallion had both his eyes gouged out. As the horses jostled and shifted, she saw a colt on the floor, trampled to a pulp by the crowd.

She asked the driver where the horses had come from, and why they were in such ghastly shape.

He pointed to the Virginia Mountains and said the horses had just been rounded up by plane out there and were headed for the slaughterhouse in California.

Johnston began to weep.

“No use crying your eyes out over a bunch of useless mustangs,” the driver said. “They will all be dead soon anyway.”

That moment forever changed Johnston’s life. She decided that day to work on saving Nevada’s remaining mustangs. Within a few years, she had built a national movement. Tens of thousands of people were demanding protection for wild horses. They began calling Johnston by a nickname, “Wild Horse Annie.” And she eventually, after an effort that lasted more than twenty years, led them all to victory.

When the Chappel Brothers plant stopped slaughtering horses in the 1940s, the slaughter business never really recovered, but it didn’t entirely go away. The remaining herds were too small and too hard to reach to be viable for big factories. There was no money in it. But then a new efficiency came along that kept mustanging viable: airplanes.

A plane could skim low over the roughest terrain, flushing herds out of rough country. One pilot could see for miles and the plane never grew winded. It did the work of a hundred men and erased the problem of sending “good horses after bad” through perilous country.

A California pilot named Floyd Hanson, described as “a tall, gangling, cheerful fellow,” became one of the first sky wranglers in 1938, when he took an old open-cockpit biplane to the Owyhee Desert of southeastern Oregon. He was getting $5 a head, as men had done decades before, but he could gather many times more horses in a day. He claimed to have collected ten thousand wild horses in Oregon.

He swept over the sage, coaxing the animals out of the canyons, looping, diving, sideslipping like a “skidding billiard ball,” according to a writer who flew with him for a profile in Popular Mechanics. After ten miles, the writer reported, “the herd has been run to the verge of exhaustion. Their most heroic effort just can’t match the ‘bird that never tires.’ ”1

Once on the ground, Hanson related to the writer a modern version of the legend of the White Stallion. There was a horse called Silver King, he said—pure white and uncatchable by even the fastest riders. Every rancher in the area had tried, but no one had come close. One day Hanson scared up Silver King with his plane. He chased him for miles, but the stallion seemed never to tire. Then, just as the plane was about to push Silver King into the corral, the horse reared and broke back, escaping into the badlands.

Eventually, during another flight, Hanson said he managed to catch Silver King, but he held him only long enough for the other wranglers to see him, before turning him loose again. It was, in a way, a fitting update for the legend of the White Stallion. Man, bolstered by technical innovations, could finally tame nature. And yet, he let it go. It was the first inkling of a budding ethic of conservation that later spurred Velma Johnston to pursue her work.

But the airborne mustangers of the 1930s and 1940s gave little actual thought to conservation. A cowboy named Frank Robbins in the Red Desert of Wyoming also started using planes. By his telling, he at first tried to round up horses the old-fashioned way when a band he was pursing on horseback got scared by a mail plane in 1938. He hired one plane, then two. At times, he was pulling in three hundred horses a month, which he mostly shipped east to slaughter. He worked the open range of the Red Desert for twenty-seven years, claiming to have gathered more than thirty thousand horses. “Eleven years we worked on the Red Desert, which is about 150 miles by 150 miles,” he later said in an oral history. “We pretty well cleaned out the area except for a few. Then they outlawed the plane for roundups and since then the horses have had it easier. I’m kind of glad, because if they hadn’t there wouldn’t be a one left.”2

After World War II, small-time mustang operations using army veterans as pilots traveled Wild Horse Country, subsisting on a combination of what they could get from the meatpackers who desired the horses and what they could get from the ranchers who didn’t. By the 1950s, the Department of the Interior estimated there were only twenty thousand horses left, almost all pushed into the driest, most forbidding, and most inaccessible corners of the West.

It was, many thought, the end of the wild horse. A few more years would see its extinction. When Frank Dobie published The Mustangs in Texas in 1952, he reckoned that the only true mustangs that remained were those that still roamed the American imagination. On the very last page, he broke into poetry:

I see them vanishing, vanishing, vanished,

The seas of grass shriveled to pens of barbwired property,

The wind-racers and wind-drinkers bred into property also.

But winds still blow free and grass still greens,

And the core of that something which men live on believing

Is always freedom.

So sometimes yet, in the realities of silence and solitude,

For a few people unhampered a while by things,

The mustangs walk out with dawn, stand high, then

Sweep away, wild with sheer life, and free, free, free—

Free of all confines of time and flesh.3

What Dobie could not foresee was that at the same time he was finishing his manuscript, a thousand miles away a young secretary in Nevada was about to throw a saddle and bridle on the legend of the mustang and make everything change.

Rarely does anyone encounter a single, crystalline moment that abruptly alters the course of life—not just one life, but the whole country’s. But the morning Velma Johnston peered into that truck full of mutilated mustangs, she suddenly forgot about getting to work on time.

“I went home that night and I knew I couldn’t live with myself unless I did something about it,” she later told the author and activist Hope Ryden. “I decided right then that I would not rest until I had done everything humanly possible to stop such atrocities.”4

After recovering from the sight of the bloodied horses in the back of the truck, Johnston dried her eyes, got back in her car, and drove to work. Within a few years, she was leading a movement to save wild horses that eventually reached the halls of Congress.

No movement probably ever had a more unlikely leader. Johnston was not a trained activist, and she had likely never met one. She had no funding, few connections, and only a high school education. She was often introduced as a “ranch wife,” and she told people she was “more accustomed to a hitching post than Emily Post.” As she was rising to national prominence, a best-selling children’s novel based on her life, called Mustang: Wild Spirit of the West and featuring a girl named Wild Horse Annie, made her out to be a simple cowgirl with a heart of gold straight out of a 1950s Western. The public cast Johnston as the flesh-and-blood protagonist who brought the myth to life. She was the cowgirl, the woman with the white hat, the hero. The White Stallion would escape once again, but this time with the help of a little “ranch wife” and the United States Congress.

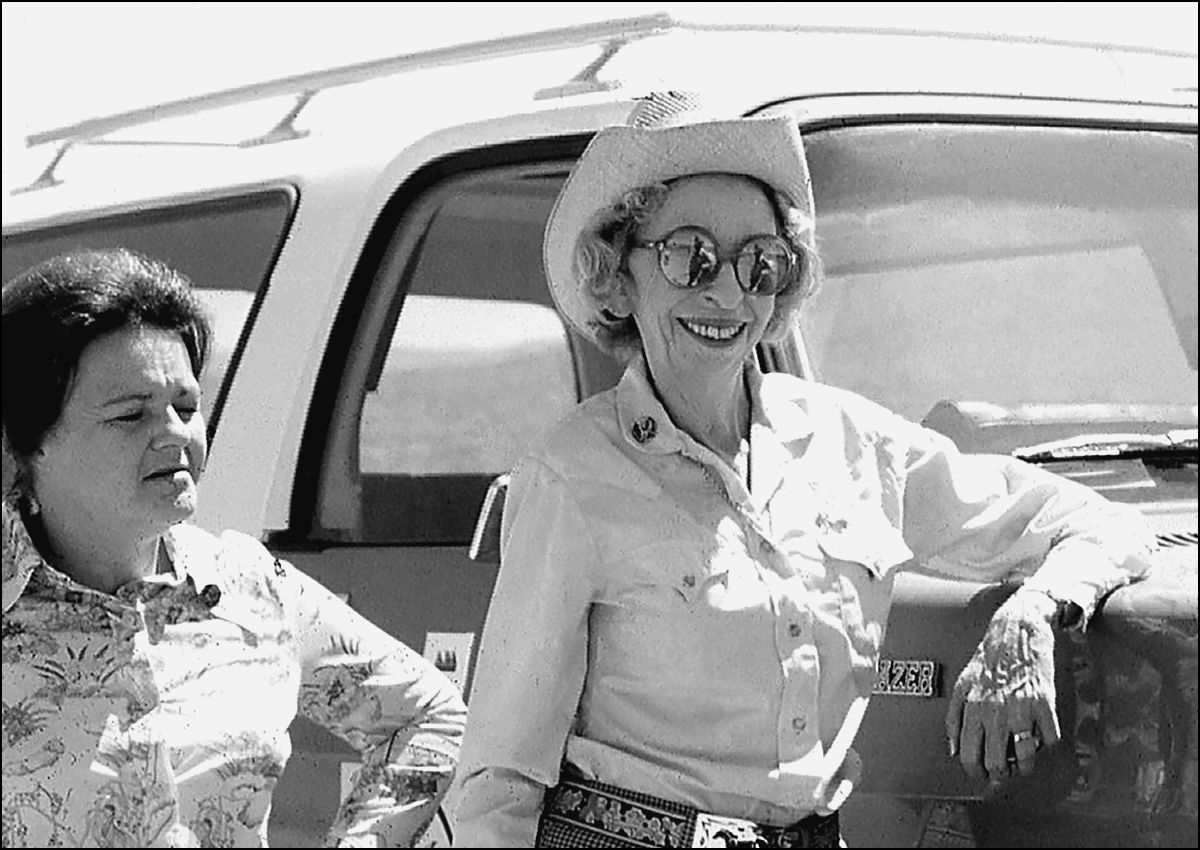

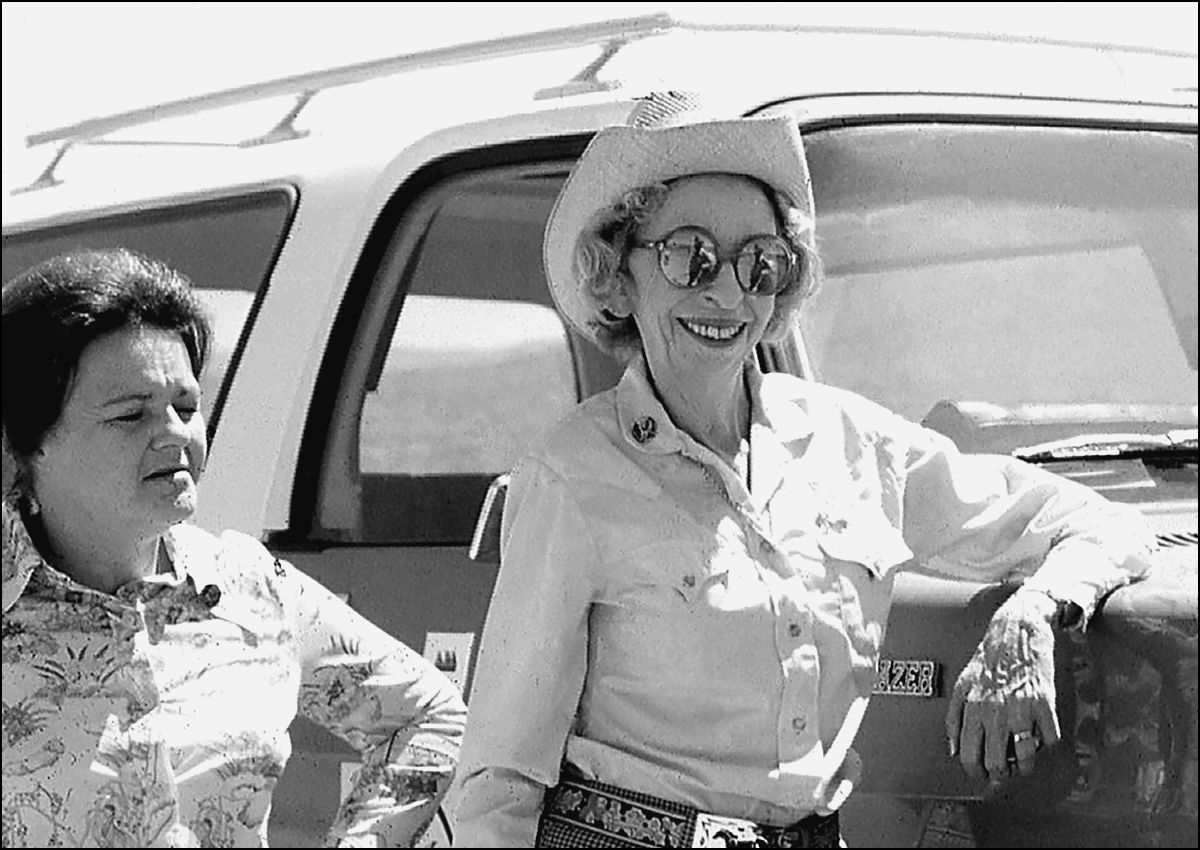

VELMA BRONN JOHNSTON, BETTER KNOWN AS WILD HORSE ANNIE, WITH FELLOW WILD HORSE ADVOCATE DAWN LAPPIN (LEFT) AT STONE CABIN ROUNDUP, NEVADA, IN 1975.

Johnston, however, was hardly the naive country wife she often pretended to be. She was much more at home behind a typewriter than in the saddle. She was head of her local executive secretaries association and could type a hundred words per minute, but she was allergic to horses. Though she owned a few, she rarely rode. She was clever and funny, sentimental on occasion but practical as a rule. She was aware that in the 1950s and 1960s, she was navigating a world run by men, but she was hardly intimidated by it. “All I need is a tight girdle and a case of hair spray to keep me going,” she once wrote to a friend.5

She enjoyed stiff cocktails and banging out show tunes on her mother’s piano. She smoked constantly and traveled with a flask of whiskey in her purse. One would think her health alone should have kept her from taking on the momentous wild horse issue. Her twisted spine kept her in constant pain and she had trouble sleeping at night. She once told a friend that she was able to keep going with what she called “slow pills and go pills.” None of this even once deterred her.

“I’m 5'6", 104 pounds, a 62-year-old widow and I’m tired and overworked,” she said in an interview years later. “But I’m unbelievably tough.”6

Johnston’s story has been told in wild horse circles often enough that it has become a blend of fact and legend that is sometimes hard to untangle. When the fictional story of Wild Horse Annie helped her cause, she went with it. By the end of her life, even people close to her couldn’t for sure say which parts of her past were Velma and which were Annie. And maybe it doesn’t matter. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

Johnston had the luck to begin her life of activism just when the legend of the mustang was at its cultural peak and the herds in the West were still at a level where swift action could save them. In 1950, when she encountered the truck full of mustangs, Westerns were the main genre in Hollywood. Just that year, she could have gone to the theater in Reno and seen Branded, The Baron of Arizona, Broken Arrow, Comanche Territory, High Lonesome, The Nevadan, Rio Grande, Sierra, John Ford’s Wagon Master, and dozens of other films. The Cisco Kid and The Lone Ranger were on TV. My Friend Flicka, the 1941 novel about a boy and his mustang, had become a classic of children’s literature. The nation was saturated with stories that told and retold the legend of the West, and the mustang played a starring role. Annie was successful not only because she revered wild horses but also because at the time nearly everybody did.

Johnston’s family arrived in Nevada in 1882, and her grandfather got work in a silver-mining town called Ione, which was tucked in the Shoshone Mountains in the middle of the state. The family had been there six years when one of the major mines closed and they were forced to leave to look for work. The story goes that shortly before they set out for California, two hundred miles to the west, her grandmother gave birth to her father, Joseph Bronn. The family headed out in a covered wagon pulled by two domestic horses and leading a half-tamed mustang mare from a rope on the back. A few days into the journey across the desert, Johnston’s grandmother’s milk gave out, and she could no longer feed Joseph. Unsure what to do, her grandfather milked the mustang mare and gave the milk to the child, saving his life. It’s a story Johnston later told often to show how much she owed to mustangs.

The town of Ione today is a ghost town, with just a few residents who cater to tourists looking through the abandoned buildings. Wild horses still roam the hills all around it. Johnston’s father, Joseph Bronn, grew up to be a freight driver in Reno, and he used the tough little wild horses captured from the hills to pull his wagons. He had three children in a small, tidy house with a white picket fence on the edge of town. Velma was the oldest, born in 1912. To earn extra money when the kids were small, Joseph would catch mustangs in the hills near town. The start of World War I doubled the price, and he spent his weekends hunting them. Johnston later talked about seeing him gentle them in a small corral in the backyard.

In 1923, when Johnston was eleven, something happened that might have been her defining characteristic if not for wild horses. She contracted polio. What started as a fever soon changed to throbbing in her joints. Paralysis set in and she was hospitalized. With polio nearly eradicated today, it is easy to forget what a vicious affliction it is. In severe cases, the virus infects the brain and spinal cord, causing muscles to go limp as nerves fail. But this failure is uneven. Some muscles go limp while the complementary muscles continue to pull, so limbs slowly twist into wracked and painful poses. Johnston’s paralysis attacked her back, pulling her spine and neck in different directions.

Unsure what else to do, her parents sent her to Children’s Hospital in San Francisco, where she was put in a body cast to try to hold her spine in place. The skinny girl was covered in white plaster from her hips to her head. With her spindly legs and arms sticking out, she later joked that she looked like Humpty Dumpty. According to one account, during her long days in the cast, she liked to gaze at a painting in the ward that featured a band of mustangs tossing their manes as they galloped across the sage. With their unbound freedom and strength, they were everything her little plaster-encased life was not. Though we don’t know for sure whether that picture is just part of the legend, it’s easy to imagine the little girl looking at those horses and yearning to be home, where she could be healthy, safe, and free.

When the cast was finally removed, Johnston’s family was shocked. Months of straining against the plaster had disfigured her face. Her jaw was pushed back, making her top teeth jut out. The left half of her face, starting above her brow, slumped down and away from the rest of her face, giving the appearance that she was starting to melt. Her back and neck were twisted in a cruel S shape that made her look forever off balance. Before she went home, her parents hid all the mirrors in the house.

Polio may have been a pivotal experience for Velma Johnston. It left her disfigured and unable to have children, which at the time was all that was expected of girls like her in Reno. Instead, the fallout of the disease steered her to focus on her studies, her career, and ultimately, wild horses.

After graduating from high school in 1930, she got a job as the personal secretary to the president of an insurance company in Reno. It was a job she kept the rest of her life. Like polio, secretarial work became an unexpected resource in the struggle for wild horses. Johnston learned to fire off clear, error-free letters at a machine-gun pace. Her smooth voice, given a slight velvety edge by cigarettes, carried none of the shock that her face did, and she became an expert at working the phones. At a time when making copies—or mimeograph copies, as they were known then—was still a specialized skill, she could roll out hundreds in short order. It all sounds so basic, but these skills turned out to be as crucial as a love of horses, because the main obstacle to saving the last remaining mustangs was getting the word out. At the time, before television had really taken over and the Internet was not even a glimmer, an efficient secretary was maybe the best weapon anyone could have in the information war.

A few days after Johnston encountered the truck of bloody mustangs, she went to alert the BLM about the theft of animals from public land and their mistreatment. According to her account, the regional range manager at the Reno office assumed she had come to complain about wild horses grazing on the land, and he assured her that the bureau was doing as much as it could to rid the land of the pests. Even better, he boasted, because the bureau relied on freelance mustangers who sold the horses to slaughter, the eradication wasn’t costing the taxpayer a penny. This was Johnston’s first indication that the federal agency that policed the range was not going to be an ally in the fight to save the mustang. There was no law to protect wild horses, and no agency to stick up for them. As Johnston later told her biographer, Marguerite Henry, “We had to be our own law.”7

Faced with the realization that there was no legal way to protect horses, Johnston chose the same path as Frank Litts had done a generation earlier: When the law protects something morally abhorrent, break the law. Though she did not resort to dynamite, she was unwilling to let mustangs go to slaughter, so she and her husband, an incrementally employed construction worker who rolled his own cigarettes and liked to quote Persian poetry, began driving the deserted mountain valleys of western Nevada on the weekends, searching for the corrals the mustangers used to collect their catch. When they found unattended corrals, they slipped open the gates and watched the horses run free into the hills. At the time, mustang roundups were regulated by Nevada county commissioners in the state, and entirely legal. Setting free the legally collected horses was not. This part of Johnston’s story doesn’t make it into most accounts of her life. In Mustang: Wild Spirit of the West, a fictional account of her life written for children, Wild Horse Annie takes pictures of the horses trapped in corrals to alert the world, but she never sets them free.

From those first acts of defiance, Johnston became an activist and quickly learned her talents could be better used on the legal side of things. The road between her ranch and Reno cut through the Virginia Mountains in Storey County, Nevada. In 1952, she learned the Storey County commissioners were considering a permit for another roundup, and they were going to take a vote at the next commissioners’ meeting. She showed up the night of the meeting, intending only to take notes. The room was packed with locals who liked having the horses roam the hills and didn’t want a roundup. A mailman from the county seat, Virginia City, stood up and said he had a petition signed by more than a hundred people opposing the mustang roundups. “These roundups are completely against the spirit and tradition of the West!” he said.8

In fact, they were right in line with the tradition of the West but completely against the legend crafted by so many pulp novels and Saturday matinees. Ranchers in Nevada had been warring with mustangs for generations, but increasingly people in the West didn’t make their living off the land, and many of them wanted protection for the mustang.

After the mailman finished, he sat down, and it appeared no one else planned to speak. With the commissioners about to vote, Johnston stood up. Using shorthand she had taken during a conversation with local BLM officials—a worthy secretary always took detailed dictation—she laid out the facts as she saw them.

“Mr. Chairman, I’m just a simple secretary,” she began. The mustangers, she said, were making thousands of dollars by sending public property to the fertilizer factory. The federal managers at the BLM were encouraging it. The mustang was nearly extinct and there was no one to stick up for it. The commissioners had to act, she said, to keep greedy men from wiping out a piece of the West.

The crowd cheered. The roundup was unanimously voted down.

Johnston gained a friend in Lucius Beebe, editor of the Territorial Enterprise. “Every so often there is put in motion agitation for the destruction of one means or another of the bands of wild horses which still roam the hills,” he wrote in an editorial. “The current pressure is being applied solely for the benefit of two sheep ranchers who claim their grazing lands are being impaired by the horses. In view of the practically unlimited grazing lands in western Nevada and the absurdly small number of the horses, such claims are purely fictional. The wild horses, harmless and picturesque as they are, are a pleasant reminder of a time when all the west was wilder and more free and any suggestion of their elimination or the abatement of the protection they now enjoy deserves a flat and instant rejection from the authorities from within whose province the matter now lies.”9

At the next meeting, Johnston and a few other locals persuaded the county commissioners to ban the use of aircraft altogether in roundups in the county. It was her first taste of success.

Johnston soon started working with a handful of other local wild horse lovers in Reno to draw up a bill for the state legislature that would extend the ban on aerial roundups to all of Nevada. It was a long shot. The only people in the Nevada establishment who were not ranchers were miners, and neither groups were likely to stick up for wild horses. So Johnston started building grassroots support to pressure lawmakers. She assembled a mailing list of anyone she could think of who might be sympathetic: riding clubs, 4-H clubs, humane societies, school groups, editors of papers and magazines of all sizes. To each she sent a hand-signed letter and a small bulletin laying out the basic argument that something had to be done before the greedy dog-food factories and the cruel mustang wranglers drove the last remaining wild horses to extinction. Letters of support started to pour into the Capitol. Before long, the governor of Nevada was getting more mail on the mustang than any other issue.

The BLM, however, continued to round up horses at a frenzied pace. One of their go-to pilots was Chester “Chug” Utter from Reno, who was proud to say he had rounded up forty thousand horses for the agency. “You need every spear of grass for deer, antelope and cattle,” he once said in an interview. “I’d much rather have wild game than a bunch of horses you can’t do anything with.”10

In 1955, at Johnston’s urging, a state senator named James Slattery introduced Johnston’s bill banning the mechanized hunt of wild horses. Many of Nevada’s newspapers began to take up her cause. If the United States passed laws protecting the bald eagle, an editorial in the Nevada State Journal asked, “Why cannot we in Nevada afford some protection to an animal which, more than any other, symbolizes the history, the strength, the progress of Nevada and the west—the wild horse.”11

The BLM fought the proposed ban. The agency had grown out of the United States Grazing Service—a New Deal agency established in 1934 to bring needed order to the free-for-all grazing on the open range of the West. Before the Grazing Service, grass on the public lands belonged to anyone who wanted it, which resulted in disastrous overgrazing and often-violent disputes over territory. In 1934, Congress passed the Taylor Grazing Act to establish a system of leases to regulate grazing and the Grazing Service to enforce them. The Grazing Service, and then the BLM, was staffed by livestock men who thought only in terms of livestock.

When Johnston showed up lobbying for bans, the BLM and the ranchers were likely at first dumbfounded. They had been playing the same game for decades. BLM was the referee, the ranchers were the players, and everyone agreed on the game: maximizing the livestock that could be raised on the public land in an orderly and somewhat sustainable fashion. There might have been grumbling by both bureau and ranchers over stocking numbers or grazing fees, but no one argued that the game should change. Then here was someone—a woman, no less—who, with the help of other women, children, and various outsiders, wanted to change the grazing game completely. She wanted to let in wildness, wilderness, heritage, freedom. No doubt the old players were at first mystified. Then they were likely dismissive. And then, when Johnston started gaining traction, and was seen as a credible threat, they were pissed. She got threatening phone calls from some ranchers. Others had her followed. “I’m about as popular with these people as leprosy,” she once said about the stockmen. She began carrying her husband’s .38.

The regional BLM director, Dante Solari, when encountering Johnston at a hearing for the proposed state ban, reportedly sneered, “Well, here comes Wild Horse Annie herself.” It was probably meant as an insult, but Johnston wore it like a title, telling and retelling the story through interviews and letters until many people thought Annie was her real name.

The Nevada bill to ban mechanized wild horse hunts passed in 1955, but not before the BLM and ranching interests slipped in a provision that made the state regulation not applicable on federal land. That was a big deal, because almost 90 percent of Nevada is federal land—and virtually all wild horses are found there. So Johnston’s first statewide victory was a hollow one. Despite all her work, she knew the law would not save many horses.

She was not ready to quit, though. Fueled by cigarettes, “go pills,” her love of mustangs, and support from the public, Johnston typed letters late into the night, creating a broad grassroots alliance. She soon had a nationwide alliance of horse lovers, their names all neatly catalogued on index cards. She was also building a stable of sympathetic journalists. The passage of the state bill attracted the attention of the national press. They visited Nevada to meet Wild Horse Annie and see the mustangs firsthand. First came a columnist from the Sacramento Bee, then a correspondent from the Denver Post, then a reporter from the New York Times. Reader’s Digest and Life—two of the most popular magazines in the country, with a combined circulation of millions—both picked up the story. They described Johnston in almost mythic terms as a tiny, tough-as-nails cowgirl fixin’ to stampede a law through Congress, and “the most tireless, outspoken friend the mustang ever had.”12

She was happy to play the part. “I was born on a horse,” she told the Denver Post. “I love horses tame or wild. I just had to do something about the way they were being treated.”

In 1957, Johnston had a visit from an old elementary schoolmate named Walter Baring, who was Nevada’s lone representative in Congress. Baring was, in the words of a later Las Vegas Review-Journal profile, “a 250-pound bear who liked both his rhetoric and his cigarettes unfiltered.”13 He was a former tax collector and small-town politician who had slipped into office by a razor-thin margin. A Democrat in a Republican state, he reliably voted with Southern Dixiecrats against civil rights legislation and believed the United Nations, the civil rights movement, and fluoridated drinking water were all Communist plots. But Baring also had a keen sense of politics. He was elected to ten terms and liked to say, “Nobody likes Walter Baring except the voters.”

And perhaps he saw in wild horses a chance to grab onto a bill voters would love. He offered to introduce a bill that would ban aerial hunting on federal land and close the gaps in the state bill. If having a disfigured secretary from Reno as the wild horse movement’s champion was a bit odd, it was nothing compared to having a congressional ally like Walter Baring.

They made a deal. Johnston and her allies would write the bill, Baring would introduce a bill called HR 2725, and Johnston’s vast grassroots network would pressure every congressman to support it. In July 1959, Johnston walked into a hearing room in the US Capitol wearing white heels and white gloves and carrying a white handbag. Her hair was sprayed up into a bouffant, her small frame was wrapped in a crisp sheath of cotton prints. The newspapers that day described her as a “hardy ranch wife,” but she looked and spoke like anything but.

“By removing this comparatively easy method of capture, we feel it will no longer be worth the while of the professional hunters to operate, either for themselves or for individual ranchers, or for the government, for it has been the practice of the land management agencies which may not be equipped to carry on the operations within their own personnel to turn over the actual roundup to private professional operators,” she told the committee. “My colleagues do not believe that humane herding of the horses and burros can be done by aircraft or mechanized vehicles. We also feel that if they are in such rugged terrain as to preclude the possibility of horseback roundups, then surely that terrain is not usable as range for cattle.”14

So much for folksy.

“Mr. Chairman and members of the Committee on the judiciary,” she continued. “The fight for the mustang has come a long way in the past few years. . . . From a mere handful of fifty or so firm believers in the right of survival, it has come to an awareness throughout the country of his desperate plight, resulting in a mighty plea on his behalf.”

The Bureau of Land Management, fearing that horses would once again spread by the tens of thousands, as they had in the nineteenth century, tried to weaken the bill with an amendment that read, “Nothing in the Act shall be construed to conflict with the provisions of any Federal law or regulation which permits the Land Management agencies responsible for administration of the public lands to hunt, drive, round up and dispose of horses, mares, colts or burros by means of airborne or motor driven vehicles.”15

In other words, it would be business as usual on federal land.

Johnston fired off letters to everyone involved: congressmen sponsoring the bill, groups of animal lovers like the Humane Society, and her grassroots Rolodex of citizens. She let them know the bill must remain as it was written, without interference from the BLM. She pressed her case in newspapers and radio interviews. While a few rural papers opposed her, most of the national papers trumpeted the need to save the mustang. Hundreds of thousands of letters poured into Congress in support of the bill.

At the hearing, a BLM range officer named Gerald Kerr told Congress that the agency needed to keep horse numbers down, and that the horses on the range were not truly wild, but merely unclaimed ranch strays. “Wild horses, as such, do not exist on the public lands today,” he said. “The unclaimed and abandoned horses now using the federal ranges are remnants of extensive horse ranch operations which were conducted on the public ranges of the West until the 1930s.”16

But Johnston eventually prevailed. The bill was passed a few months later without the BLM’s amendment. On September 8, 1959, the final version, known as the “Wild Horse Annie Law” became law. It banned all aerial roundups on federal land. Johnston hoped the law would end the era of mustangs being chased down for dog food. It didn’t.

Ranchers continued to try to purge the public land of wild horses and the BLM did little to stop them. Often mustangers would get around the new law by releasing some branded animals out into the herds, then using them as an excuse to round up branded and unbranded alike. The BLM openly encouraged the practice, saying in a press release at the time, “The rancher may use any method he wishes . . . including driving the animals with trucks or airplanes . . . if someone intends to round up his own animals, he may accidentally take wild horses at the same time.”17

Velma Johnston railed against this practice and continually pressed the BLM and local authorities to crack down. In 1967, she got her first shot. A tip came into the office of the White Pine County sheriff that a Nevada rancher named Julian Goicoechea had hired a famed Nevada mustanging pilot named Ted Barber to round up horses on public land near his ranch. The sheriff and the brand inspector drove out in a Jeep and, from a high ridge, spotted the plane diving after a group of mustangs in a remote spot called Long Valley. The pilot and copilot dangled a rope of tin cans and operated a howling siren to scare the band forward. For good measure, they were also firing a shotgun at any that turned back. When confronted, the men said they had been rounding up horses for weeks, but that the unbranded horses belonged to the rancher and were not wild. An investigation found the men had sent more than 150 horses to slaughter, and only four had brands. The men were quickly charged under the Wild Horse Annie Law.

What seemed like an open-and-shut case quickly fell apart. In court, the mustangers argued that the animals were, in fact, branded, but thick winter hair hid the markings. The horses had been in the possession of the mustangers since their arrest. The defense had the horses shaved, and, lo and behold, they had brands. A local jury quickly acquitted the men.

Johnston was furious but did not give up. She next tried to catch another longtime aerial mustanger, Chester “Chug” Utter. In 1969, tipsters had told her that he had built a trap in the Virginia Mountains, introduced domestic horses into the wild herd, and was ready to bring in a plane to round them all up. Johnston organized volunteers to watch for the plane and had the local sheriff on call, ready to arrest Utter. Word may have gotten out, because Utter never showed. Eventually, as a publicity stunt, Johnston got local school kids to dismantle the trap and called the Associated Press to cover it.18

In the decade after the law passed, it was as if nothing had happened. Aerial roundups were still sending mustangs to the chicken-feed factory. No one had been successfully prosecuted. Horse numbers had continued to decline. BLM leaders still saw themselves as the good guys, fighting for quality range management against an uninformed public. “I think this whole thing is an emotional issue whetted by Walt Disney movies,” Harold Tysk, BLM director, told a reporter in 1967.19 The BLM estimated that by 1970 there were only about ten thousand wild horses left.

But across the country, attitudes were changing. During the 1960s, Velma Johnston’s once-lonely push to save horses turned into a movement. Humane groups brought their thousands of members to the cause. A number of well-connected East Coast women became Johnston’s allies. There were Pearl Twine and Joan Blue of Washington DC, who both had been working already for years to improve treatment for domestic horses in the East. There was Hope Ryden, a fashion-model-turned-documentary-filmmaker for ABC News, who in 1970 published a best seller called America’s Last Wild Horses, which sounded an urgent call for preservation. Popular national magazines such as Cosmopolitan, Life, Time, and National Geographic all published big spreads on the disappearing mustang. School groups across the country baked cookies and sold bumper stickers to raise money for Johnston’s cause.

“How sweet the ride on the bandwagon is,” she wrote to a friend in 1970. “And the politicians are quick to smell out a possible campaign boost.”20

It’s worth taking a step back to realize that Johnston and other horse supporters were not working in a vacuum. Her awakening to the idea of conservation is closely tied to a broader realization among the American public that the wild remnants of the country were nearly gone and desperately needed protection. It was, in a big way, the natural reaction to the abuses of the Great Barbecue.

It had been simmering for decades. In 1949, a year before Johnston encountered the truck of bleeding mustangs, a former US Forest Service game manager-turned-conservationist named Aldo Leopold published the seminal ecology book A Sand County Almanac. “Like winds and sunsets, wild things were taken for granted until progress began to do away with them,” he argued in the book. “Now we face the question whether a still higher ‘standard of living’ is worth its cost in things natural, wild, and free.”21

The answer from an increasing number of Americans was “no.”

In the 1950s, the Nature Conservancy was founded and the Sierra Club grew from an outing group into a political force. In the 1960s, laws were passed regulating pollution in air and water and protecting endangered species and wild and scenic rivers. There was a national clamor for more regulation to protect the wild world.

Culture shifted toward environmental ethics, too. In 1942, Disney had released Bambi, one of the first mainstream broadsides against cruelty to animals. The 1961 film The Misfits, the last film made by stars Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe before both died, was an anti-Western that revealed the horror of mustangs being sent off and turned into dog food.

By 1970, the public drumbeat for conservation was deafening. That year, the United States celebrated the first Earth Day. In 1971, Dr. Seuss published his classic children’s book on conservation, The Lorax. During the first years of the 1970s, Congress, with broad bipartisan support, passed the most sweeping environmental laws in the nation’s history: the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and the Coastal Zone Management Act.

President Richard Nixon recognized environmental causes as a feel-good issue that would distract voters from the Vietnam War and coopt a campaign issue raised by Democratic opponents. He had never pushed for environmental regulation. He saw environmentalists as “hopeless softheads” and privately dismissed environmentalism as a fad. He notably got in a shouting match with the president of the Sierra Club and stormed out of their private meeting.22 But he was happy to step in and take credit for saving charismatic symbols of freedom. “Like those in the last century who tilled a plot of land to exhaustion and then moved on to another, we in this country have too casually and too long abused our natural environment,” he told Congress in February 1970. “The time has come when we can wait no longer to repair the damage already done.”23

It was in this context that Velma Johnston went to Washington in April 1971 to push for the passage of the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act at a hearing of the House Committee on Public Lands. The act had been introduced by her old friend Nevada Congressman Walter Baring. At the hearing, where forty people were scheduled to speak, Baring introduced only Johnston by name, calling her his “lifelong friend.”

The rest of the wild horse bandwagon was there too: the Humane Society, the National Mustang Association, the Sierra Club, the Animal Rescue League, the Citizens Committee on Natural Resources, and the American Horse Protection Association, among others. There were also witnesses who cautioned against the bill, saying that if wild horses were left unchecked, they would soon eat the range to dust.

With Johnston’s encouragement, tens of thousands of children had sent letters to their congressmen. Since the beginning, she had always seen kids as her main ally, and she had courted them strategically by speaking to schools and 4-H groups. “You can almost see the Stars and Stripes waving in their eyeballs when you give them a stirring talk,” she said in a video interview near the end of her life.24

The press jokingly referred to it as a “children’s crusade.” Fittingly, one of the first representatives to appear before the committee, Gilbert Gude from Maryland, asked if he could let his eleven-year-old son Gregory speak, since he was “really involved in me getting involved in the legislation.”

Gregory took the stand. Neither he nor his father had ever been to Wild Horse Country. “Lots of people have read about the wild mustangs,” he said. “My dad and I have gotten about 1,000 letters and petitions supporting the bill. We even got a letter from Brazil.” He held up a letter from a nine-year-old girl in Mississippi and began reading: “Every time the men come to kill the horses for pet food, I think you kill many children’s hearts.”

More than a dozen conservation and animal groups pressed for passage of a horse protection bill. There were also enough livestock and BLM representatives that Johnston quipped while testifying, “I am taking a chance turning my back right now on this whole room full of people.”

Given the years of animosity toward wild horses and Wild Horse Annie, the BLM and livestock interests staged a fairly tepid defense. No one from the bureau spoke at all. An official from the Department of the Interior, which oversees the BLM, appeared to say only that the agency supported protection and could run the program for about $3 million a year. And though livestock and sportsmen’s groups were cautious, none outright opposed protection.

A spokesman for the National Cattleman’s Association spoke in favor. In the past, he said, mustangs were “part of the bounty of our great land to be harvested, as needed, for the benefit of mankind. They have been taken for granted.” He only tepidly pressed for one consideration: that wild horses not affect the number of cattle on the range, and that ranchers be paid if they do.

A spokesman for the Wyoming Wool Growers Association, the only other livestock group, was more dire in his predictions. The law would be so onerous, he said, that it would “turn every private landowner into a crusader to remove all wild horses.” If the “government got into the livestock business,” he said, it would soon find its wild herds increasing, and would have to remove animals to control population, as cowboys in Wyoming had done for generations. Only a few mustangs would be suitable to be saddle horses. “The surplus animals each year would have to be disposed of by burying, burning, or some other sanitary disposal method,” he warned.

The harshest words came from Lonnie Williamson of the Wildlife Management Institute, a fish and game group. He said mustangs were actually “trespass stock of a not-too-impressive ancestry” that did not belong on the land. “It must be remembered that although mustangs are respected and cherished by a great many people, they are aliens which compete with native species,” he said. “To manage wild horses on a priority basis to the detriment of native wildlife would not be in the broad public interest.” Failing to limit their numbers, he warned, would change the mustang from “a symbol of unbridled freedom” into “a symbol of environmental degradation.”25

A few of the committee members from western states were also clearly skeptical, particularly Wayne Aspinall, a longtime congressman from western Colorado who had grown up in Wild Horse Country. “Most of the wild horses are not horses that any of us would look twice at,” he said. He worried about crafting a sweeping federal solution that would take away control from counties and states. “What has bothered me throughout the last many years is the fact that every time we can’t do something at home we want to look far away in order to get the task taken care of. Uncle Sam is the one who pays all of it.”26

Ultimately, the critics were too few and their warnings too weak against the urgent message delivered by Velma Johnston.

She appeared poised and ladylike in her stiff bouffant, with impeccably researched testimony that she had been building for more than a decade.

“Since I was one of those who started the fight long ago,” she said, “I feel adequate to pass along the feeling of our people in America. The wild horse and burro symbolize the freedom, the independence upon which our country was founded. . . . Perhaps it is because the forbearers [sic] of these wild horses and burros were alien to these shores as were our own forbearers. Perhaps it is because they settled in the wilderness, fought off Indian attacks, enforced law and order, brought civilization to this country,” she added. “My mail alone averages 50 letters a day. This fight has captured the interest of young people as no other.”27

With the passage of the 1959 Wild Horse Annie Law, she said, “We thought we had a happy ending,” but the ranchers were determined to continue their campaign against wild horses. “They are fenced off from their grass and water holes. . . . They are indiscriminately shot, trapped or driven off.” Mustangers who had been caught red-handed were acquitted or not charged at all. Just a few months earlier, the commissioners of Elko County had approved the roundup of several hundred horses that were sent to the slaughterhouse.

The law, she said, “has not been effective in areas where it is not in the best interests of the elected officials to see that it is enforced.”

The Department of the Interior had proposed setting up half a dozen preserves for wild horses. It estimated that ten thousand of the remaining seventeen thousand horses were not Spanish mustangs but domestic strays, and should be killed. The rest would be relocated to preserves and protected. Johnston pushed instead for all wild horses to be managed in the places they lived, as integral parts of the land. She rejected the idea that horses had to be of a certain breed to count as a mustang. All that mattered to her was that they were born free.

She knew that numbers would have to be managed, but she thought the right oversight would ensure it was done humanely. “I asked for a management and control program,” she said. “I realized it must be multiple use. The cattle people have contributed greatly.”

Congress continued to be deluged by letters from citizens. After receiving bags of mail from grade-schoolers, one representative from Texas wrote to his constituents: “Am I going to be susceptible to pressure? Am I going to be influenced by a bunch of children? Am I going to support a bill because kids . . . are sentimental about wild horses? You bet your cowboy boots I am!”28

The law passed easily and was signed on December 17, 1971, by President Nixon, who then sent Velma Johnston a personal letter, thanking her for her “splendid efforts over the years.”

In the end, the new Wild Horse Annie Law—officially called the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971—gave Johnston almost everything she had asked for. It protected horses where they were found on federal land, and it imposed stiff fines and jail time for anyone who captured or harassed wild horses. It made releasing domestic horses on public land illegal to end the mustangers favorite pretense for roundups. And, maybe most important, it recognized wild horses’ and burros’ right to exist.

The law began:

Congress finds and declares that wild free-roaming horses and burros are living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West; that they contribute to the diversity of life forms within the Nation and enrich the lives of the American people; and that these horses and burros are fast disappearing from the American scene. It is the policy of Congress that wild free-roaming horses and burros shall be protected from capture, branding, harassment, or death; and to accomplish this they are to be considered in the area where presently found, as an integral part of the natural system of the public lands.

With the law, Johnston stopped a century-long killing spree and likely saved the wild horse from annihilation. But she also put the mustang on a future course that was far different from anything she imagined: the one we live with now.