All the ‘fairies’ and other supernatural beings of this first group of stories are of the diminutive kind. They have human characteristics but are also endowed with powers of magic and enchantment. They live underground or in hillside caves, and do not care much for human company except where they attach themselves to a particular place or household, either for good or ill, and even then they take care not to be seen. These are the true ‘folk’ fairies, common to all European countries, where in some areas belief in them continued until quite recently.

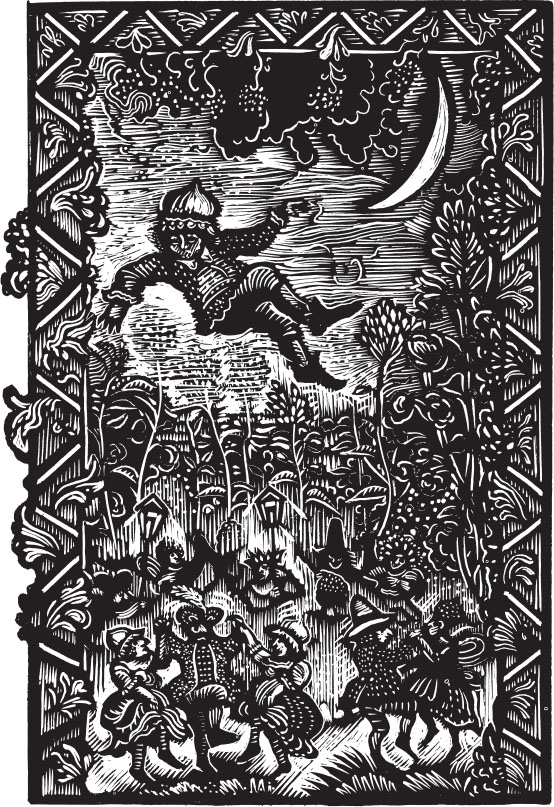

In this tale, a Sussex labourer is allowed to speak for himself. His tale concerns the involvement of supernatural creatures in the ordinary, everyday life of the folk, not, as in ‘fairy tales’, the translation of humans to a faery world. The little people, generally so well disposed towards humanity, like to keep their activities secret, as James Meppom found to his cost; but dragons don’t need to hide. Nobody stays long enough in their vicinity to cause them any annoyance.

They tell me as some folk don’t believe in the little people, as we call Pharisees, no more than they do in dragons. The reason is that they never set eyes on the one nor the other. They believe in the angels, though, and they believe in God, but I don’t suppose any of ’em ‘as ever seen Him. ‘Ah,’ they say, ‘but God and the angels are in the Bible, so they must be true.’ Well, ain’t the Pharisees in the Bible, likewise? And as for seeing, there’s folks as have seen ’em, as I heard tell many a time when I was a boy. And I have seen the rings they make, dancing on the grass. If the Pharisees didn’t make ’em, what did? But many a year ago there was a chap called Mas’ Fowington, what told another man called Mark Antony Lower all about the time his grandmother see the little people, and this Mas’ Lower wrote it all down.

Mas’ Fowington’s old granny said she’d seen the Pharisees with her own eyes, time an’ again; and she was a very truthful woman, by all accounts. They was little folks,’ she says, ‘no more than a foot high, and they was uncommon fond o’ dancing.’ They joined hands and made a ring, and danced on it till the grass come up three times as green there as it was anywhere else – like it says in the old harvest song folks used to sing in the old days. ‘We’ll sing and dance like Pharisees,’ it says. There’s other folks beside Mas’ Fowington’s granny as have heard ’em singing in queer, tiny little voices.

Then there’s that story about how one o’ they Pharisees took vengeance on a farmer called Jeems Meppom. He were Mas’ Fowington’s great-grandmother’s brother. It would ha’ been a powerful sight better for Jeems if he hadn’t never seen ’em – or leastwise, if he hadn’t never offended ’em, because that’s what happened, seeminglie.

Jeems was a small farmer who had to thrash his own corn. His barn stood a fairish way from the house, and both of ’em were in a very lonesome place. And Jeems would thresh his wheat or oats in the barn all day, and then go home for his supper and bed, leaving the heap o’ threshed corn on the barn floor. And morning after morning, that there heap were bigger than he’d left it the night afore. Well, Mas’ Meppom just didn’t rightly know what to make on’t. But he were a real out-and-out chap for boldness, what feared neither man nor devil, as the saying is. So he made up his mind to go over to the barn some night, and see how it was managed.

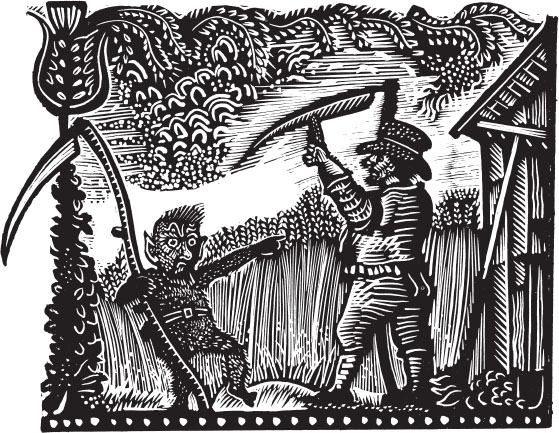

Well, accordinglie, he went up there one evening early, and hid himself behind some straw. After a long while he begun to get powerful tired and sleepy, ‘cos it were well after his bedtime, and he thought it weren’t going to be no use to watch no longer. When it got pretty near midnight, he decided to go home to bed, and just as he begun to move, he heard a curious sort o’ sound coming towards the barn, so he stopped where he was. And he peeped out o’ the straw, and what should he see but a couple of little fellows about eighteen inches high come into the barn without ever opening a door. They pulled off their jackets, and they begun to thresh that corn with two tiddly little flails as they’d brought with ’em. And they set in to that threshing at such a rate as you wouldn’t hardly credit.

No doubt Mas’ Meppom would ha’ been scared if they’d been bigger, but as it was they was such tedious little chaps that all he wanted to do was to bust out laughing. Thump, thump, thump went their tiddly flails, regular as a clock, and Jeems had to push a handful o’ straw in his mouth to stop hisself from laughing out loud. So they kept at that threshing till they got tired, and then they stopped for a bit of a breather. And one of ’em says to the other in a little squeaky voice, as it might ha’ been a mouse talking, ‘I say Puck,’ he says, ‘I sweat! Do you sweat?’

Well, when he heard that, Jeems Meppom just couldn’t contain hisself nohow, but bellowed out laughing. Then he jumped up from the heap o’ straw, and hollered, ‘I’ll make ye sweat, ye little rascals! What business ha’ you got in my barn?’

Now when they heard this, them little Pharisees picked up their flails and whushed right by him. And as they passed him he had such a pain in his head as if somebody had give him a lamentable thump with a hammer, and knocked him down flat as a flounder. How long he laid there he didn’t know, but when he come to hisself it were getting daylight. He got up to go home, but he felt so queer as he could hardly doddle along; and when his wife see how tedious bad he looked, she sent for the doctor directly. But, bless you, that wasn’t no use, and Jeems, he knowed as it wasn’t. The doctor told him not to worrit too much, but keep his spirits up. He said it was only a fit Jeems had had from being almost smothered with a handful o’ straw in his mouth, and from keeping his laugh down when it wanted to come up. But Jeems knowed better.

‘Tain’t no use. Sir,’ he says to the doctor. The curse o’ the Pharisees is upon me, and all the stuff in your shop can’t do me no manner o’ good.’

And he was right, for no more than a year afterwards Jeems Meppom died, and lays in the churchyard over there, poor fellow, under the bank where the snowdrops grows. He were sorry enough that he’d ever interfered with goings-on as didn’t concern him – leastwise, that’s what my great-grandmother used to say.

Then there was several folks over to Horsham in the old times as see the dragon in St Leonard’s Forest. That were a tedious lonesome old place in times gone by, such a place as you might expect serpents and such to be bred in. And the folks as lived thereabouts was powerful upset by that dragon. It used to come out from the trees and maunder about nearly as far as Horsham, and often round another place called Faygate, and the folks as lived there were lamentable worried by it. Where that had crawled you could always see, on account o’ the slimey trail it left behind it – like a snail, only a powerful sight wider and thicker. But that slimey trail give off such a powerful stink as you couldn’t get anywhere nigh it. It made the air all round so bad as folks died on it, putrefied the air, it did, so as there weren’t many as would stop to look at the dragon long if they did happen to catch sight of it.

But there were three people as did see that old landserpent. The carrier at Horsham, who used to put up at the White Horse in South’ark, he were one. There were three others, as well, who were willing to sign their names to a paper as were wrote out about it, all three living at the place called Faygate. They were John Steele and Christopher Holder, and a widow woman who couldn’t write her name but made her mark against the place on the paper that said ‘And a Widow Woman dwelling nere Faygate.’ This is that they set their hands to. They said that this serpent, or dragon, was nine feet or more long, and shaped like the axle-tree of a cart, thickest in the middle and thinner at both ends. The front part, as were his neck, were about as long as a man’s arm, and had a white ring of scales all round it. The scales on its back were blackish, and its belly, what anybody could see on’t, were blood red. (Of course, folks didn’t stop long enough close to it to examine it properly.)

It had very big feet (though some say that dragons get along without feet, and move faster without ’em than most creatures can with ’em). This landserpent could move faster than a man can run, feet or no feet. When he heard the sound of a man or cattle of any kind, he reared his head up and listened, proud as could be. Then folks who had sight of him said he had two powerful great bunches, one each side of him as big as a football, sticking out from his shoulders; and ’twas thought that in time they would grow into wings. The people that wrote their names on paper said they prayed that God would allow for this old dragon to be destroyed before it ever got properly fledged, or God help the poor folks thereabouts!

When it heard an enemy, that serpent would spit, and the filthy venom would fly as much as four rods from his mouth (’bout the same length as a cricket pitch). And if that stuff got on anybody, it were the death of him that minute. They swelled up and died, and many’s the body been found like that, killed by the dragon though he never ate any of ’em. One man thought he’d chase it and run it down, so he took his two tedious great mastiff dogs with him, and set off. Them dogs didn’t know how dangerous the serpent could be, and they got too close, though the man held back a safe distance. When the dragon reared the man turned and run off as fast as he could, but it spit on his dogs. So when he went back, his two dogs laid there dead and p’isened and all swelled up, but they hadn’t been attacked no other way. ’Twas thought the dragon got his meals in the rabbit warren mostly, because that’s where most of them as had clapped eyes on him had seen him; and folks complained that conies were getting powerful scarce on account o’ this. I don’t know no more about it, nor what happened to it; none o’ my kin ever see it, as far as I know, though they’d heard about it from their grannies when they were little children. And I have heard that that paper as the Widow Woman o’ Faygate made her mark on were writ in King James’s day, afore the Civil War. Time out o’ mind, that is, so I shouldn’t think that dragon’s there now. My folks would never go there anyway, on account o’ the ghost o’ Powlett, what still haunts the place. Likes a good ride on hossback, Powlett does, but he h’ant got no hoss of his own. If you go through the forest on a horse, you’ll find him up behind you, with his horrible ghastly arms round your waist. T’ain’t worth risking, I say.

Ah, there’s more tales about seeley Sussex than them about smugglers over to Alfriston and down to Birling Gap. There’s folks still alive though whose grandads helped to fool the excise men on the cliffs round Cuckmere, that there is. You ask in the Star, or the Smuggler’s at Alfriston. They’ll tell you.

This is another story demonstrating the inadvisability of questioning the help of the unseen little people; but there is a moral to this tale too, pointing out the likely consequences of meanness and ingratitude.

Farndale lay under snow such as never before in living memory. Up on the moors everything was buried under a thick blanket from which rose little eddies of blue-white smoke-like mist as the wind whipped dry snow into drifts. The valleys were choked and the pools solid. If was as if a white slow death had settled over Yorkshire, bringing life to a standstill – except on the farms. There, where there were animals to be cared for, somehow or other the winter had to be held at bay till the dale was once again gold-over with daffodils.

Up at old Jonathan Grey’s farm there was great anxiety about the many sheep trapped in the snowdrifts on the moor, and the chance that already some ewes might be dropping early lambs. The farm was a prosperous one, for Jonathan was well established, and a hard worker like the many generations of his family before him; but he was not rich, or even well-to-do. He was comfortable. His household was comfortable, and his comfortable wife saw to it that the lads and lasses who lived there had a good living too.

Ralph had been with them since he was a lad of ten, and had learned his craft as a farm-hand from Jonathan himself. As he grew tall and strong into manhood, his skills soon outclassed those of his master. There was no one for a dozen miles in any direction who could shear with such dexterity, mow with such rhythmic speed, or thresh with such untiring strength as Ralph. He owed it all to Jonathan and the farmer’s kindly wife, and worked as hard and as long as he could in gratitude. So it was that when somebody had to go out onto the snow-covered moor to try to rescue sheep and lambs, it was Ralph who volunteered. Jonathan and his wife watched him striding purposefully away, walking with the aid of his shepherd’s crook. Then a fresh blizzard swept down across the landscape, and they saw him no more. Hours passed into days, and days to weeks, but Ralph did not return. When at last the weather let up enough to allow them to look for him, all they found was his frozen corpse, buried beneath a snowdrift.

It was a tragedy for the farm in more ways than one, for with Ralph’s death the farmer had lost his right-hand man, the best worker and the truest, most loyal servant. Jonathan and his wife grieved for Ralph as for a son, and gloom settled over the household.

Then, as Jonathan lay brooding in bed in the dead of night, he heard strange noises coming from the barn which was attached to the old stone farmhouse. Thump, thump, thump, it went, in tireless, even rhythm. The farmer thought he must be dreaming, but the noise went on and soon awakened his wife. They sat up in bed listening, and a few minutes later the whole household was roused. They came together with tousled heads and half-opened eyes, bare feet shoved hastily into boots, and bodies draped with blankets and quilts for decency’s sake.

‘What can yon clatter be?’ they asked each other, while the girls huddled together in fear. At last one of the lads voiced everybody’s thoughts.

‘Theer’s somebody or somm’at threshin’ in t’barn!’ They all listened, and at last Jonathan said, ‘Aye! That’s what yon is! Somebody threshin’, in t’barn!’ But he made no move to go and find out, and there was no other lad brave enough to volunteer. So they returned to their beds in awe and superstitious fear, but there was no more sleep that night. The steady thumping of the flail went on till the first rays of dawn broke in the east, and the noise stopped as suddenly as it had begun. Then Jonathan and his men crept cautiously to the barn door and looked inside. They could hardly believe the evidence of their own eyes. During the night, more corn had been threshed than any one of them could have managed in a day. They stood peering with astonished gaze, all thinking the same thing. At last Jonathan voiced the thought.

‘Not even Ralph himself could ha’ done more, nor better.’

Next night, the unseen thresher was at work again, and Jonathan thought it wise to let well alone. By the time all the corn was threshed, they had got used to the noise, and slept through it; but from that time the invisible helper became a regular hand at the farm. In the spring he brought hay in; in summer he mowed, and in autumn he sowed. But at sheep-shearing time he excelled himself, dealing with whole flocks in a night, and leaving the fleeces so carefully rolled and packed that there was little for Jonathan and his hired men to do. There could be no doubt about it. Good luck had come to the farm.

Now there were those who believed that all the work was being done by the ghost of Ralph; but there were many more who thought it could be put down to one of those tiny, brown, shaggy little mannikins all Yorkshire knew of, called hobs. Such hobs were usually friendly towards humans, and would always help rather than hinder, provided their wishes were attended to, and they were not deliberately made angry. As all the women could tell you, the surest way to offend a hob was to suggest that he should cover up his nakedness, for clothes of any kind hobs cannot abide. But they could be relied on to help, especially if they had special skills like the one at Runswick Bay, who lived in a cave called the Hob Hole. That one could cure whooping cough, when nothing else would.

You just took the afflicted child to the mouth of the cave, and called out:

Hob-hole Hob, Hob-hole Hob,

My poor bairn’s gotten t’kin cough,

So tak’t off! Tak’t off!

And sure as fate, the cough would disappear within a day or two.

Jonathan Grey was satisfied with his hob, whether it was the spirit of Ralph as well or not. When the hob had worked for him a goodish time, he discussed with his wife how they could reward the hob for all his trouble, without offending him. Jonathan’s wife was as wise as she was kindly, and suggested that a bowl of her best cream should be put in the barn every night. So they tried it out, and sure enough, next morning the bowl was empty.

The hob stayed on, and the bowl of cream was never forgotten. In the course of time the old couple became quite well-to-do; but like everyone else, their time at last ran out, and they died. The farm passed on to their son, and still the hob stayed on, doing two men’s work every night for the wages of a bowl of cream. The farm continued to prosper throughout the lifetime of that generation, and the time came when it passed on again, this time to another Jonathan Grey. This Jonathan inherited the hob with the rest of the farm, and his wife, Margery, was as careful to set out the cream at night as her husband’s mother and grandmother had been.

But nobody’s good luck lasts forever. There came a sad day when Margery died, in the full bloom of her womanhood, and left Jonathan desolate. It was only then that he discovered that Margery had done almost as much work about the place as the hob. Without her the dairywork never seemed to be done, the meals never on time, clean shirts and smocks never ready when wanted, and the children always ailing. After the worst of his grief had passed, common sense suggested that he should take a new wife. He had not much heart for the choosing of her, but before long Margery’s vacant place was filled.

He soon found that his second wife was not the good manager Margery had been. Moreover, she was jealous, shrewish, and above all, mean. She scraped and saved, and grudged every mouthful the farm lads ate. Most of all, she grudged the cream set out nightly for the hob.

‘Yon hob!’ she snorted, ‘fed on t’best o’ cream when t’rest of us is well-satisfied wi’ t’buttermilk! An’ tha’ canna be certain as ’tis hob that drinks it! Like as not ’tis t’cats, or t’rats, as leaves the bowl clean at morning. We’re like to be ruined, wi’ thy feckless ways.’

Her husband listened, but he took no notice. As long as he was master, the hob should have his reward.

Is a man ever master in his own house when he has a determined, nagging wife? When winter came, and the grass was poor, butter was scarce; and as it grew scarcer, so its market price went up, and every day the farmer’s wife grudged the cream for the hob more. One night when her husband was working late, she set out the bowl for the hob as usual; but it contained nothing but skimmed milk.

That night, for the first time for generations, the sound of the hob at work was not heard. No corn was threshed, no harness mended, no wool carded, no spinning done. Spring came, but there was no hob to help with the haymaking, or with the sheep-shearing in the summer. The harvest came and went but the hob did no mowing, tying or carrying. This was bad, and the farm was suffering; but worse was to follow. Strange things began to happen. Churn as she might, the wife’s butter would never come. She tried everything she knew, but the cream only rolled itself into the tiny balls all farmers’ wives call ‘pins and needles’. She even tried putting a silver coin in the churn, but the cream refused to be turned into butter, while all her cheeses turned black with mould. Her hams became fly-blown as they hung in their bags from the rafters, and the sides of bacon so reisty they could not be eaten. Foxes stole the geese she was fattening for the Christmas market, and the cows went dry. Sheep got foot-rot, and pigs died of the fever that attacks swine now and then. For every piece of good luck in the past, there now seemed to be three calamities.

Then the house became haunted. No longer did the steady thrum of the hob’s flail lull them into satisfied slumber. Instead, the house was filled with terrifying noises. It sounded as if a host of demons were throwing things in the kitchen, with the clatter of fire-irons falling, the banging of metal spoons on pewter plates and kettles, the crashing of falling crockery and the clanging of pansions and pails.

From other rooms and the stairway issued cries and howls, drummings and thumpings, hollow groans and ear-splitting, blood-curdling screams, though never a thing was to be seen. Unseen hands snatched off the bed-covers, while candles snuffed themselves out. Furniture moved of its own accord, doors locked and barred themselves while opened gates in the farm-yard allowed animals to wander away to the trackless moors.

No servants would stay in the house, nor labouring men help on the farm, so terrified were they of the daily (and nightly) happenings that no human agency could account for. Jonathan was at his wits’ end to make both ends and middle meet, and from being a happy, healthy, robust and successful farmer, he began to look old, worried and poverty-stricken, as indeed he was. He had long suspected that in some way his wife had offended the hob that had so helped his grandfather and his father to success; and after denying it forcefully for a long time, she at last confessed that she had once substituted skimmed milk for the bowl of cream.

Then Jonathan was in despair, for he knew only too well what revenge an offended hob could take. He tried in every way he could think of to appease and propitiate the hob for the insult given by his wife. Nothing was of the least avail. At last, ruined in pocket, robbed of health and defeated in spirit, he decided that the only thing to be done was to leave the farm that had been in his family’s possession for generations back, and try his luck elsewhere.

There was no one to help pack up the home now, except the family; but that was of no account, for there was little enough left to pack. All the goods there were went easily on to one farm cart, and the only horse left on the farm stood drooping between the shafts. Last to come out of the old stone house was the feather bed on which generations of Greys had been born and died. It was placed on top of all the other broken bits and pieces, and the old wooden churn, taken from the dairy, was set upright on its end at the back of the cart. The grudging wife climbed up, and sat on the feather bed, while Jonathan sadly took his seat and picked up the reins. Then with one last sad look round his now deserted farm, and a last despairing glance at his empty childhood home, Jonathan picked up the reins and clicked his tongue to the dejected horse. Slowly and mournfully the cart with its passengers made its way through the fields to the road, and there, at the first bend, Jonathan found himself face to face with one of his old neighbours. The man took in the distressing sight at one glimpse, but could scarcely believe what he saw.

‘Heigh-oop, Jonathan lad!’ he exclaimed. ‘Tha’ canna ha’ coom to this, surely! What art thee about, man?’

Jonathan replied heavily, ‘Aye, but it has coom to this! We’re flitting!’

Then, to everyone’s great consternation, a strange, queer, husky voice from the cart growled loudly and distinctly, ‘Aye! We’re flitting!’

With a sinking heart Jonathan turned in his seat, and looked over the cart; and there, sitting crosslegged on the upturned churn, was the oldest, ugliest, hairiest little man that could ever be imagined. His brown wrinkled body was entirely naked, but the bulging eyes in his overlarge head glinted with wicked, malicious glee, like sparks struck from granite. And while the farmer and his wife remained in dumbfounded silence, the hob let out a shriek of cackling laughter, and rocked to and fro in his vengeful mirth.

Then Jonathan, knowing himself utterly beaten, began to pull on the reins to turn the cart around. ‘Aye, we’re flitting,’ said Jonathan, ‘but if thou art flitting wi’ us, then we’ll e’en flit back again, for ’tis all one to me now.’

And it was.

The little people may be clever, hut they do not have a monopoly of wit. Though the farmer and the hogle are in dispute, for once it is the farmer who comes off best – a most satisfying and comforting conclusion to people so much at the mercy of agencies (such as the weather) that they cannot control and can only comhat hy endurance and dogged mother-wit.

There was a bogle, so they say, who was forever getting up to tricks to pester the life out of farmers.

But there are farmers and farmers. Jack was a farmer, though not one of the well-breeched sort who could afford to ride about while other folk did all the work. He was only a peasant farmer whose family had been scraping a living out of a few fields of grudging land since before the Romans came. He lived with the soil on his boots, the smell of it in his nose and the feel of it on his hands.

Hard living breeds hard men. Jack was both hard and shrewd, and a tough customer when it came to doing a deal, as the bogle found to his cost when he picked Jack for his next trick.

Every peasant farmer wants to increase his holding, and Jack was no exception. Next to his little parcel of land was a field he had had his eye on for many a year, knowing that when the present owner died it would have to come into the market. So when this happened at last, he was ready with his savings and before long the business was done and Jack was home again in his tiny cottage, sitting by his hearth well satisfied with his bargain.

He rubbed one work-hardened clenched fist round and round in the open palm of his other hand, and stared into the bright orange eye of the fire as he contemplated future harvests on his new field.

That’ll bear well, come harvest, now it be mine,’ he said, speaking aloud to himself, as he often did.

‘It beant thine, though,’ answered a growly voice from the other side of the fire.

Jack looked up, and shook his head in case his ears were playing tricks on him. Then he shook it again, to make sure he was seeing straight. Sitting cross-legged in the old wooden chair at the opposite side of the hearth was a bogle – a tough, dried-up, weather-beaten little chap with a face as brown and wrinkled as old leather and a thatch of grey hair like an old mare’s mane. Jack knew by his size he must be a bogle, for he was no more than half a man in height.

‘It beant thine. Jack,’ says the bogle again. ‘It be mine. It’s been in my family for ever and a day.’

‘It’s mine now,’ Jack replied, gathering his wits together at last. ‘It’s bought an’ paid for, and I’ve got the papers to prove it.’

‘Papers!’ snorted the bogle. ‘What’s papers got to do with it? They don’t prove nothing! That field belonged to my family when the moon was made of green cheese, donkey’s years before such as you lived on the earth at all.’

Jack had never actually seen a bogle before, but he’d heard about them since he was a child. They were crafty little creatures, and it didn’t do to get on the wrong side of them. He needed time to think.

‘If it’s your field, as you say,’ Jack said, ‘how is it that it has been farmed so poor this many-a-year?’

‘Simpleton! Numbskull!’ says the bogle, laughing. ‘The other chap wouldn’t agree to my bargain, so he never got a proper harvest at all.’ The crackling laughter leapt up the chimney like a cloud of sparks from a crumbling log, while the bogle displayed two rows of yellow teeth as old as the hills, and as sound.

Jack thought he understood.

‘What’s your bargain, then?’ he asked.

‘That’s better,’ said the bogle. ‘I can see as you are going to be more sensible than that other fellow. Why – it’s my field. You do all the work, and we share the harvest between us. How’s that?’

‘Well,’ said Jack slowly, ‘I’m not afraid of a bit of hard work, if I get a fair deal at the end. I’ll do the work, and we’ll split the crop. Is it a deal?’

‘Done!’ said the bogle.

Jack thought it would be a sorry day when a man like him couldn’t get the best of such a bargain.

‘What’ll you have, then, first year?’ he asks the bogle. ‘Tops or bottoms?’

‘O, tops, of course,’ answers the little man, getting off the chair and standing on his short, bandy legs looking up at the farmer. ‘I’ll ha’ the tops, and you ha’ the bottoms. That’s as fair as fair can be, I do declare.’ And away he went on his little short legs, leaving Jack scratching his head and thinking hard.

So Jack tilled the ground, and sowed it, and up came as good a crop as heart could wish for. Then the bogle came again, to collect his first year’s rent.

‘Let’s see,’ said Jack. ‘If I remember rightly, we agreed that you should ha’ the tops, and me the bottoms.’

‘That’s so,’ said the bogle.

‘Ah! Well, you’ll find a fair-sized heap o’ turnip-tops all ready for you just inside the gate,’ said Jack.

Then the bogle could see that he’d come out the wrong side o’ the bargain, and he wasn’t at all pleased.

‘What about next year?’ he growled, cracking the joints of his fingers one by one.

‘What about next year?’ said Jack. ‘What’ll you have, tops or bottoms?’

‘Bottoms,’ said the little bogle. ‘This year you can have the tops, and I’ll take the bottoms.’

‘Just as you like,’ replied Jack. ‘It’s all one to me.’

So when the autumn came, he prepared the field again, and planted barley. Up came the crop, as good a stand of corn as ever met a farmer’s eye.

At harvest time, along came the bogle again to claim his share.

‘Tops mine, and bottoms thine, this year. That was the bargain, wasn’t it?’ said Jack.

‘It was so,’ nodded the bogle.

‘Then you’d better see about carting off the roots and the stubble,’ said Jack. ‘I threshed the ears last week.’

Well, that bogle really was put out by being got the better of twice in a row.

‘Next year,’ he says to Jack, ‘you’ll sow that field with wheat, and we’ll divide the standing crop.’

‘Done,’ said Jack, ‘on condition that you help with the reaping.’

The bogle thought that would be a good way of making sure he wasn’t done down for the third time.

When the harvest time came round again the bogle appeared, to make arrangements for the reaping.

‘We’ll have a match,’ said the crafty bogle, who was proud of his age-old skill with sickle or scythe. ‘We’ll mow half the field apiece, and the winner takes all!’

Jack looked at the little fellow, and agreed to take him on. ‘It’ll take a fair bit o’ reaping,’ said the farmer. ‘There be a mort o’ docks in it. Which side of the field will you have?’

‘I’ll have the far side,’ said the Bogle. ‘Docks are of no account to me. I was using a scythe when such as you were tadpoles in the weeds.’ So they set a date for the mowing match.

Then Jack went off to the blacksmith’s, and ordered a lot of thin iron rods. When he got them he took them and planted them upright among the sturdy wheat straw on the far side of the field.

When the set day arrived, along came the squat little bogle with his bandy legs and his strong arms, carrying an ancient scythe over his shoulder; and along came Jack, carrying his scythe in the same way. Then they honed their blades to put a fine edge on them, gave the word, and set in. Jack bent his back and began to mow, taking in huge swathes with a steady, swinging rhythm like the experienced reaper he was; away on the far side the little bogle swung his razor-sharp blade in powerful curving sweeps as well – till he met the first iron rod – and then another – and then another. Every time he hit one, it brought his blade up sharp, and he thought it was a tough old dock root.

‘ ’Nation hard docks these be!’ said the bogle. ‘ ’Nation hard docks! ’Nation hard docks!’

And every time his scythe caught a rod, it took the edge off the blade till the bogle might as well have been trying to mow with a wooden stack-peg. When his blade got so blunt that it would hardly have cut hot butter, the bogle straightened his back and looked across the field to where Jack was getting on with his half like a house afire.

‘Hi, mate!’ called the bogle. ‘When do we stop for a wiffle-waffle?’ – by which he meant, ‘When do we stop to sharpen our scythes?’

‘Wiffle-waffle?’ says Jack, as if in surprise. ‘Why – in four hours from now, about noon time,’ answers Jack, and bends to his swing again.

But the bogle looked at his notched and blunted blade, and knew the game was up as far as he was concerned. So he shouldered his scythe and slipped out of the field, and Jack never set eyes on him again – well, so the tale goes.

Jeanie, the Bogle of Mulgrave Wood

Jeanie is one of the few female bogles on record, and attests well the truth of Kipling’s line that ‘the female of the species is more deadly than the male’!

Just north of Whitby lies the village of Sandsend, and close to Sandsend is Mulgrave Castle, and Mulgrave Wood which in the past was the home of a family of bogles. How many of them there were, nobody seems to know; but there were certainly several, because the noise they made when laundering their linen in Claymore Well used to echo far and wide; and when the noise of the clashing of their ‘bittles’ sounded down the dales, it was a brave man or woman that would have turned out of his cottage to see what they were about. ‘Best leave yon bogles alone,’ they said, and wisely acted upon their own advice.

Well – all but one man, that is – a farmer who found out to his cost what came of meddling with the bogles. The chief bogle, it seemed, was one called Jeanie, a very virago of a bogle, who seemed to have none of the saving graces such as some others had, such as the hob who would cure the chin-cough if you went and asked him nicely.

History does not relate why the farmer wished to make the acquaintance of Jeanie. Perhaps he did not really believe in her, and wanted to settle the matter of her existence for himself, once and for all. Or perhaps, being pot-valiant one night, he had taken a wager to visit the female bogle in her den; or it may even be that he had a problem he could not solve, and being a canny Yorkshireman, decided that help comes best to them who help themselves, and that happen Jeanie was the one with the answer. Whichever way it was, he saddled his horse one day and set out to visit Jeanie on her own ground.

Once into Mulgrave Wood, he sought out her dwelling, which was a cave set in a rocky slope. Leaning from his saddle, he called her loudly by name.

‘Jeanie!’ he called. ‘Jeanie! Art’ a theer? Coom out, lass. I want a word wi’ thee!’

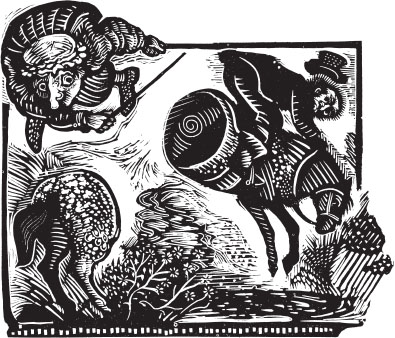

There was a noise from the inside of the cave like a couple of wild cats fighting, and Jeanie answered his summons. He really had no time to look at her well enough to be able to describe her afterwards. She was about the size of most bogles, old and a bit wizened, and ferociously ugly, with her snarling lips pulled back from a set of yellowing teeth, he thought, though it was only a fleeting impression he got; but she came out of her hole like a whirlwind, brandishing in her hand her magic wand. And if the farmer himself would have stood firm before that wand, his horse wouldn’t. The poor beast laid back its ears, rolled its eyes, neighed loud in terror, spun round on its hindquarters and set off towards home at a furious gallop. Not that there is any record of the farmer trying to prevent it, once he had caught sight of Jeanie the Bogle, and understood that his attentions towards her were not welcome.

The horse was a good sturdy cob, and fear lent it wings. It galloped through the trees as if all the devils in hell were behind it, instead of only one female bogle. But that was enough. Gallop as he might, the farmer could not gain ground on her, and spur as he might, the hindquarters of his mount were only just out of reach of the thrashing wand, which she wielded with passionate ferocity while issuing the most bloodcurdling shrieks and yells.

On they went, and the foolhardy farmer suddenly bethought him of the knowledge that none of the fairy kind can cross water. His heart rose within him, then, because in front of him lay a brook, and he had every faith in his horse to take the water with one leap, especially in its present state of terror. Stealing a hurried look behind him, he saw that Jeanie was almost upon him – but there in front of him was the welcome brook. So he put his horse to the leap, though not quite in time. As the horse rose on to its back legs to spring, Jeanie’s wand descended. It fell upon the horse just behind the saddle, at the very instant of the leap. Next moment, the farmer and the front half of the horse were safe on the homeward side of the water. The back half lay at the feet of the frustrated shrieking bogle, for her wand had sliced the poor creature in two as clean as a whistle.

Needless to say, the farmer never bothered that particular lady with his unwanted attentions again!

As with ghosts, sightings of fairies, though numerous and widespread, often do not have enough detail to constitute a story, mainly because the fairies usually disappear at once if intruded upon. These three sightings are interesting because it is difficult to disbelieve them.

The first is William Blake’s own account of a sighting at Felpham, Sussex; and while it has to be admitted that he was a visionary and a mystic who as a child saw angels everywhere, the unadorned simplicity of this account gives it an undeniable air of credibility. William Butterfield, on the other hand, was certainly no ‘visionary’, and is hardly likely to have been drunk so early in the morning; nor can one credit with extraordinary imagination a man, who, faced with such a sight as he describes, can think of nothing better than to bellow ‘Hello there!’ at the top of his voice! The third tale is recounted in all seriousness, by the monk known as ‘William of Newburgh’.

I

Did you ever see a fairy funeral? I have! I was walking alone in my garden; there was a great stillness in the air; I heard a low and pleasant sound, and I knew not whence it came. At last I saw the broad leaf of a flower move, and underneath it I saw a procession of creatures, of the size and colour of green and grey grasshoppers, bearing a body laid out on a roseleaf, which they buried with songs, and then disappeared. It was a fairy’s funeral.

II

It was a glorious summer morning, very early, when William Butterfield walked to his daily task of opening up the doors of the bath-house at the wells on the hillside just above Ilkley, in Wharfedale. Looking back on the morning in the light of what happened, he said he had noticed at the time how still it was, and with what extraordinary loudness and sweetness the birds were filling the valley with song, because he had never before heard the linnets and thrushes performing with quite such gay abandon.

When he came to the wells, he took from his pocket the great iron key to the bath-house, and fitted it in the lock, as he had done so many mornings before. This time, it didn’t work. Instead of lifting the lever, the key just twisted round and round. So he put his foot against the door, to try and push it open. It gave a fraction – but the next moment, it was pushed with considerable force from the other side, and firmly closed again. This was repeated once or twice, before he set his shoulder against it, and forced it open with a rush.

What a sight met his eyes! The bath was occupied. From end to end and side to side the water was alive with little people dressed in green from head to foot. They were, apparently, taking a bath with all their clothes on, for they were in the water and on the water, jumping and skipping about it, and dipping into it with joy, and very merry into the bargain. They were about eighteen inches high, and all the time they were gambolling in and out of the water, they chattered and jabbered to each other in high-pitched, unintelligible language. William stood watching them in wonderment, and one or two of them, becoming aware of him, made off over the walls with the grace and agility of squirrels. This seemed to upset the rest and they began to make preparations as if to depart. Butterfield did not want them to go till he’d found out a bit more about them, and felt that he’d like a word with them, if possible. So he bawled at them, in his ordinary voice, as if he were greeting a group of his cronies from across the river.

‘Hello, there!’ he hollered – and away they all went, tumbling over each other and bundling head over heels in their haste to get away, squeaking, as the intruder said afterwards, ‘for all t’world like a nest o’ partridges when it’s been disturbed!’

In a moment the water was as clear and still as it had been every other morning when he’d unlocked the door. He ran outside, to see where they’d gone, but there was neither sight nor sound of them anywhere. Nor was a trace of them left lying in the bath to show that they’d ever been there.

So he shrugged his shoulders, recognizing the inevitable, that they had gone and that he’d missed the chance of a lifetime, and set stolidly about his work again.

III

In Suffolk, the village of Woolpit has a tradition that the name, which was given in the Domesday Book as Wolfpeta, is a corruption of Wolfpit; and a number of ancient trenches near the village were called ‘the Wolf Pits’. It is supposed that in the Dark Ages and before, wolves were common in East Anglia (as in other parts of the country), and that the trenches were indeed just that, pits to entrap wolves.

One day (the date is not specified, but it was probably in the Middle Ages) some labourers in ‘the Woolpit fields’ were reaping the corn; and to their astonishment they suddenly saw, coming out of the old Wolf Pits, a couple of very strange children. From a distance they appeared to be a boy and a girl, but their general appearance was so queer that the reapers laid down their sickles and ran to look at them closer. It was then seen that their flesh – wherever it was visible, and not covered by clothes of some material utterly unknown to the reapers – was bright green. Hands, faces, bodies – all were of a vivid green colour. They were silent, and looked unhappy, but at the end of the day’s work they allowed the reapers to lead them to the village.

Much interest and sympathy for the queer waifs was generated among the honest and hospitable village folk, and homes were soon found for them. Their hosts, however, soon grew very worried because they could find nothing to give them to eat that seemed to suit their palates. In fact, for a long time they subsisted on a diet of beans, and nothing else. However, little by little they ventured to taste other food, and when they began to eat a fairly normal, balanced country diet, their skins gradually lost the green colouring, and they became very much like ordinary children to look at.

At first there was no chance of questioning them or finding who (or what) they were, because they spoke no word of English, or of any other language that could be understood. But with the usual resilience of children, and their normal aptitude for language at an early age, they began to pick up what they heard around them, until they could converse with their hosts, and told a very strange tale. They came, they declared, from ‘The Land of St Martin’ – but no amount of questioning could discover where that was. It was a Christian land, and had a great number of churches in it. There was a wide river that separated it from a neighbouring country. On their own side of the river, they never saw the sun at all, but lived in a kind of gloomy, perpetual twilight. Across the river, however, their neighbours were bathed in light. At home, they had spent most of their time tending their father’s sheep, and it was while they were engaged on this that they heard a great noise, ‘like the ringing of St Edmundsbury’s bells’. This had so confused their senses that they had lost consciousness, and when they came to again, they had found themselves in the Wolf Pits, and had seen the reapers busy round them.

As time went by, they settled down happily in Woolpit, and lived normal lives; but the boy sickened and died before he grew to be a man. The girl, however, grew up to womanhood, and married a man from Lynn – after which public interest in them seems to have died away completely, for nothing further is recorded of them.

Here is yet another example of the fairies’ dislike of being spied upon, and the vindictiveness with which they will be revenged. It is also another example of the countryman’s determination to help himself in the face of adversity. In this story he is rewarded, too, for offering help to others in trouble, in spite of his own distress.

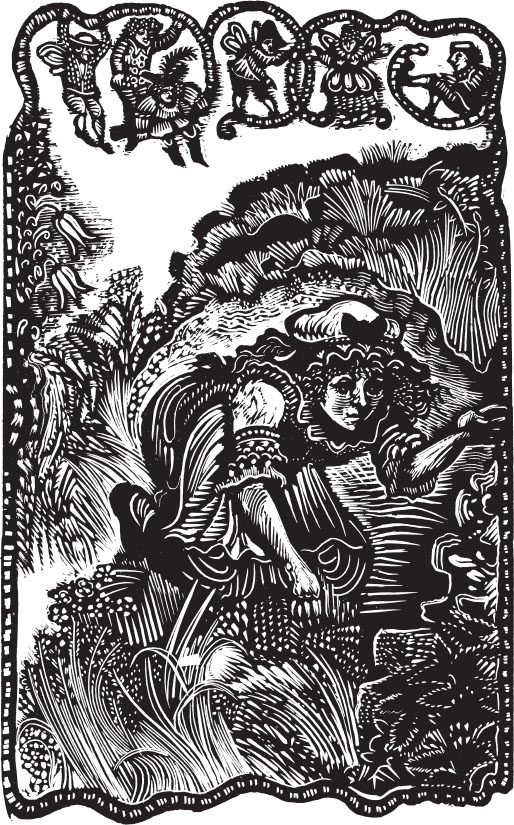

Everyone knew there were fairies in the dale, though few had ever seen them. Spread out over the hill slopes were little outcrops of rock that you could see at a glance were their strongholds – towers, keeps, battlements and all. Among these were little caves that ran back into the hillside, where the fairies met at night to hold their revels of music and laughter, singing and dancing. People coming home late at night said they had heard their silvery voices, and caught the sound of their laughter borne on the breeze; but it was well known that they were not always as pleasant as they sounded, for they were touchy, jealous little folk who could not bear to be spied on, and had their own ways of punishing any humans who trespassed on their grounds.

Close by the town of Stanhope lived a farmer, the joy of whose life was his one child, a little girl who was pretty and dainty enough almost to be a fairy herself. One day, the little girl went out to play, and wandered down to the river, along whose banks the primroses were then in full blow. After gathering as many as her little hands would hold, she set off up the hillside; but as she passed one of the little caves, she heard the sound of music, and of tiny voices raised in jollity and laughter. Drawn by the sounds that reached her, she bent down and looked in. The sight of fairies dancing and playing filled her with delight, and fascinated by the tiny creatures she ventured further into the cave. At once the fairies disappeared, so away she ran home, agog to tell her father of her wonderful experience.

The father listened to her tale in petrified terror, for he knew such intrusion would be punished, and he was also well aware of the form the punishment would take. Once a mortal had caught sight of them, that mortal knew their secrets, and this they could not bear. The only way to silence the mortal was to spirit him away, so that his own kind never set eyes on him again.

The farmer knew he had no time to waste, for the fairies might strike at any moment, and whisk his little girl away from him for ever. He said nothing of his fears to the child, but set out at once to the only person who had ever been known to outwit the fairies, a wise woman in the next village.

She listened gravely, and did her best to help.

‘They will surely come to fetch her,’ said the wise woman, ‘and they will come soon. Tonight, about midnight, is the time to be feared, and there is only one way to stop them from carrying her off. They cannot work their magic where there is no sound at all. If you can manage to keep your house in perfect silence around midnight, all may yet be well.’

The farmer hurried home, turning over in his mind as he went all the things about the house and buildings that might break the stillness of the night. Then, as soon as his little girl was asleep in her bed, he made his preparations.

First he went to his farmyard, lest anything there should break the silence. He cooped up all the poultry in the dark, barring every door and shutter to keep out a single ray of moonlight that might rouse them to a flutter of wings or a sleepy squawk. Horses were tethered to their stalls with halters, and thick straw spread round their great hoofs to muffle any sound of movement. In the cowbyre, the metal chains were unloosed, and everything that could be knocked or kicked over removed; then all doors were closed tight to stifle the sound of any gentle lowing from the cattle. Next, the farm dogs were fed as they were rarely fed, on meat and milk, till they could eat no more. Then they were kennelled close, to sleep off their heavy meal. Gates and doors were fastened and wedged, lest the breeze should make them rattle, and pig-sties strawed till the pigs and their troughs alike were buried beneath it.

The farmer next turned his attention to the house, stopping all the clocks to silence their ticking and striking, and covering the little caged bird his daughter loved with a heavy cloth to prevent its singing. As midnight drew near, he extinguished his fire lest a log should fall or a brand spit and crack, and took off his own shoes lest his feet shuffle on the hearthstone. The time wore on.

When the last stroke of midnight had fallen from the church clock in the nearby town, he heard them coming, and it was as if his very heart stood still. He heard the tiny clatter of the hoofs of their tiny ponies as they rode over the cobbles up to his door. He sensed their bewilderment as the deathly silence in house and farmyard threatened to wreck their plans; but even as he began to hope that all might yet be well, the yapping of a dog fell on his ears like doom. He had forgotten his little girl’s own pet dog, which slept always on the foot of her bed, and detecting a strange presence, had warned of danger. The farmer leapt to his feet, and raced up the stairs. The bed was empty, and the child was gone.

Grief-stricken and bereft, he sat to watch for the dawn, and as soon as it broke he set off again to the home of the wise woman. Perhaps even now, there was some way he could win his darling back, if only he knew how to go about it. The wise woman was full of sympathy, and commended him for his courage in not accepting defeat without at least another try at getting even with the fairies.

‘Nought is easy,’ she said ‘and the task will be more than difficult, but there is a way. You must go yourself to the cave where your daughter first saw the fairies, and you must take with you these things. Wear a sprig of rowan on your smock, for rowan is a sovereign charm against harm of any kind. Then you must carry three things – something that gives light without burning; a live chicken without a bone in its body; and a limb of a living animal that has been given to you without the loss of a single drop of blood. If you give these things to the King of the Fairies, he must and will return your daughter to you.’

The farmer thanked her, and left. He had now a spark of hope, but it was a very tiny spark. How was it possible to obtain three impossible things – a light that did not come from burning, a live chicken without bone, and part of a living animal gained without shedding blood?

As he trudged homeward, his heart grew heavier with every step, for he knew not which way to turn. He was roused from the depths of despair by a voice from the wayside, and looking down, he saw a woeful beggar, thin and hungry as a skeleton, stretched out on the grass.

‘In the name of God, help me!’ gasped the beggar. ‘I am faint with age and hunger, and can go no further without food. Can you help me, sir, before it is too late?’

The farmer heaved a huge sigh, and felt in his pocket for a coin. ‘I can, and I will,’ he said, ‘for though I am yet strong and hearty, I have troubles of my own, and know what it is to need help.’ And he tossed a coin to the beggar, and prepared to move on.

‘Thank you indeed,’ said the beggar, in a stronger voice. ‘You have given help willingly, and it is now my turn to help you. What you need is a glow-worm. A glow-worm will give you light, but will never burn. That is the answer to your first problem.’

The farmer stood staring at the beggar, dumbfounded with amazement; but even as he gazed, the form of the beggar grew less and less distinct till the outlines of his frail figure disappeared completely, and he had vanished into thin air. Astounded by this extraordinary happening, and cheered by the knowledge that at least he had the answer to one question, the farmer strode on with more purpose than before. It was not long before he reached the outskirts of a little wood. Hearing a frightened squawk, and noticing a flurry of wings, he stopped and looked about him. A thrush was darting this way and that, in terror of a kestrel that hovered directly above, with beak and talons at the ready for the kill when he should drop like a stone on his prey. Taking in the situation at once, the farmer stooped swiftly and picked up a stone. Then with unerring aim he let fly the stone at the kestrel, which turned and made off with beating wings, to hover in search of another meal.

The thrush settled on the branch of a hawthorn close by the farmer, and settled its ruffled feathers. Then, to his great wonderment, the bird spoke.

‘I owe you my thanks,’ it said. ‘You saved my life by giving help just when I most needed it. So now I will help you in your need. What you need is an egg that has been sat on for fifteen days. By that time it will contain a live chicken, but there will be no bone in its body.’

The farmer was so astounded that he could not find his voice; but in delight he turned towards the thrush which cocked its head on one side, regarded him with a very bright little eye, and rippled out its silvery song for him three times over. Then, before his very eyes, it dissolved into nothingness. But now he had the answer to two out of three of his problems. His step was almost light as he pondered about the third problem, though this was surely the most difficult of all.

His attention was caught by a despairing shriek from the bottom of a wall, and looking over the wall he saw among the long grass a rabbit kicking in a snare. He leapt the wall and in a moment had set the strangled little creature free. It lay panting on its side for a moment, then recovered itself and sat up on its haunches. The farmer expected it to lollop away as fast as it could, but he was growing used by now to being surprised, and listened with growing hope as it spoke to him.

‘One good turn deserves another,’ said the rabbit. ‘I think. Sir, that I can help you, for I know the answer to your last problem. If you grasp a lizard by its tail, it will escape by leaving the whole of its tail in your hand, and not one drop of blood will be shed.’

Then for the third time on that amazing day the farmer stared as what had appeared to be firm flesh and blood simply vanished from sight without moving.

But his heart was as light as his step as he now hurried towards home. Though he must still collect the gifts for the Fairy King, he knew now what to look for. He had a broody hen already sitting on a clutch of eggs, each one carefully marked with the date on which it was put under her. A few days more, and the fifteenth day would come, when he could take from the nest an egg containing a live chicken that as yet had no bone in its body. A search of the lane by the side of his farm yielded no less than three glow-worms, gleaming green and bright at the root of an old tree. They gave enough light to see by as he carried them gently home, though they certainly did not burn. Next day, out on the hills, he waited till a lizard crept out to sit on a stone and bask in the afternoon sun. Creeping as quietly as a mouse in spite of his large frame, he came silently behind the stone, and pounced on the lizard’s tail. He felt a wriggle and a jerk, and the lizard had gone like a flash of emerald; but he held its tail in his hand. Nor was there the slightest sign of blood upon it.

Overjoyed, he stuck a sprig of magic rowan bush in the bosom of his smock, and another in his cap for good luck; and as soon as the egg was ready away he went to seek the fairies’ cave.

His daughter had described it so carefully that he had little difficulty in finding it, and bending down he called to let them know he was there, and what he wanted. They rushed to the entrance of the cave, but when they saw the sprig of rowan they recoiled, for their power to harm him in any way was completely defeated by it. So they called their king, to deal with the mortal stranger; and when he came, the farmer asked him for his daughter back.

The King of the Fairies had opened his little mouth to deny the request, when the farmer laid before him the glow-worms, the egg and the lizard’s tail. Next moment, the fairies had gone, and his daughter sprang from the mouth of the cave and straight into his arms. She was quite unharmed, and they were soon at home eating dripping toast and looking lovingly at each other across the glowing hearth; but she knows better now than to pick primroses, which are the fairies’ special flowers, or to peep inside their little caves, however enticing the music may be to her ears.

Yet one more warning not to treat the helpful fairies with too much disrespect. This is much nearer to the true ‘fairy tale’ genre than any other tale in this section; hut it is firmly rooted in the day-to-day existence of ordinary people, and may possibly have originated in the miraculous reprieve at the last minute of a child condemned to be hanged for theft.

He was still only very young, in spite of having to work to help his parents keep the wolf from the door; for in those days Herefordshire was a poor county, and poor folk all laboured hard for a living. So the boy went out every morning to work for a farmer a goodish way off, and his road led through a dense wood.

Coming home tired one evening in summer, and thinking more about his supper than where he was going, he missed the path he usually took; and try as he might, he could not find it again. When it began to get dark, he knew himself to be hopelessly lost, so there was nothing for it but to sleep in the wood, and hope for the best. He took off his worn and patched jacket, and made a little pillow of it, choosing a sheltered place under a bush. Then he said his prayers, and, worn out with hunger and weariness as he was, he soon fell fast asleep.

He was aroused from his first deep sleep by the shuffling of another warm body close beside him, and as the night air had by now begun to grown chill, he sleepily snuggled close to it, and slept again. When next he stirred, he roused himself to wakefulness, and peered at his uninvited bedmate. To his horror, he saw a large brown bear, fast asleep still with its head on his little jacket. Then he was very much afraid, and wanted to creep away without waking his queer companion; but long years of childhood spent in poverty made him very much against leaving behind the only jacket he possessed.

Very gently he tried to pull the pillow from beneath the head of the sleeping bear, but with the first movement the bear woke and stood up. Then the child thought his last moment had come, but instead of attacking him, the beast nuzzled and licked him, then ambled away for a few steps before turning to see if the child were following.

It seemed such a gentle, kindly creature that the boy forgot his fears in amazement. It was still night, though a full moon was beginning to rise. By its light, the boy could see the bear clearly, and understood that it was inviting him to follow. After a moment or two of hesitation, he allowed it to lead him deeper into the wood, and before very long he made out the tiny square of a lighted window lying ahead.

Walking boldly now towards the light, he made out a little house made of turf, such as woodcutters and charcoal burners lived in. He turned to thank his furry protector and guide, but to his surprise, the beast had gone. So he went to the door of the little hut, and knocked.

A tiny woman opened the door to his knock. She was little taller than he was, though he could see by her face that she was already quite old. She motioned him to step inside, and by the light of the lamp he could see another little woman, much like the first, toasting her knees by the fire. They both looked him up and down, inquired what he was doing abroad by himself so late, and then asked if he were hungry. Hungry? He was always hungry! But especially so tonight, for he had had no supper at all.

‘Then you must have some, straight away!’ said the first old lady, while the second got up and began to prepare a wholesome supper of bread and cheese, with milk to drink. When he had eaten, the child began again to droop with weariness, aided by the grateful warmth of the fire and the satisfaction, for once, of a well-filled stomach.

‘He’s sleepy,’ said one old lady, nodding towards him.

‘We must put him to bed,’ said the other. They then explained to the sleepy youngster that he was very welcome to bide the rest of the night with them, if he had no objection to sharing their bed, for it was the only bed they had. He would gladly have slept on the hearth mg, or the floor by the door; but he was put down in a soft feather bed between the two little women, one lying each side of him. And as he drifted off to a blissful sleep, the only thing he noticed was that on three out of the four bed-knobs, a dainty white cap was hanging.

When movement roused him from the depth of his slumbers, he noticed through half-closed eyes that the little women had got out of bed, and stood by the foot of it, as if listening. Then a church clock on the edge of the forest began to strike – one, two, three, four … ten, eleven, twelve! At the stroke of midnight, the little ladies each reached for one of the white caps, and taking it from the bedpost, settled it over her silvery hair. Then they looked at each other, and the first one said, ‘Here’s off!’ while the other replied, ‘Here’s after!’ And to his amazement, they both rose up from the ground as if flying, and in a moment were gone from his sight.

By this time the boy was getting used to his unusual adventures, and came to the conclusion that he might as well now see all that was to be seen, if he could. There still remained one little cap hanging on the bedpost. He jumped out of bed, snatched the cap, and fitted it on his hard little head, saying as he did so, ‘Here’s after, as well!’ Next moment his feet had left the ground, and he was floating in the air above the bed. He flew gently out of the hut, and into the moonlight outside, where he came to earth by the side of a fairy ring, inside which his two little friends were dancing merrily, their little feet tripping to music that seemed to come from everywhere and nowhere, and made his own feet itch to join in. Before he had a chance to try, however, the two old women stopped and faced each other again. Then one said, ‘Here’s off to the big house!’ While the other replied, ‘Here’s after’ – and quick as a wink they floated upwards, and started flying away.

The boy had no wish to be left all alone again in the dark forest; so he quickly said, ‘Here’s after!’ as well, and the next instant found himself settling on top of a tall chimney of the gentleman’s huge house in the park. Then the first fairy – for he now had no doubt whatsoever that that is what they were – said, ‘Here’s off, down chimney!’ and the second, like an echo, said, ‘Here’s after, down chimney.’ So of course, he said, ‘Here’s after, down chimney,’ too – and down they went. First they raided the kitchen, gathering up all the good things to eat that they could find, stowing them away in apron pockets and anywhere else they could carry things. Next they went down to the cellar, where they moved along racks of dusty bottles, choosing one here and another there till they had selected as many as they could carry.

Then one said, ‘I’m thirsty’ and the other replied, ‘So am I.’ So they opened up a bottle of wine, and each took a dainty sip; after which they seemed to remember the boy, and asked him if he were thirsty, too. Whqn he said that he was, they gave him the bottle, and he put it to his lips. Never, never had he tasted anything so delicious! He drank and drank, tipping the bottle up and tilting his head further and further back till the little white cap fell off. Then he dropped the bottle and sank dizzily to the floor, for it was a very old, very strong and very powerful wine he had finished off, and it had made him very drunk indeed. He lay on the floor in a heavy slumber till daylight came, when at last he woke, to find himself cold and alone in the cellar of the rich gentleman’s house.

Trembling with fear, he made his way to the cellar steps, fumbled with the latch, and opened the door. It led him into the kitchen, but it was no longer empty, as it had been in the middle of the night. Instead, it was full of servants, all angry and shouting at each other because all of them were afraid. The loss of the food the fairies had taken had been discovered, and each servant was accusing another of having taken it. Then the cook turned round and saw the boy standing stupidly in the cellar door-way. She screamed, and raised her rolling pin.

‘There’s the thief!’ she screamed. ‘Catch the varmint! Catch him!’ And they all rushed to do her bidding. They had little trouble in capturing him, for his legs were still unsteady and his head still muzzy from drinking too much wine. They shook him and beat him, and questioned him about how he got in, but he could give them no answer. Then the angry cook said to the footmen, ‘Away with him to the master. Let the master punish him!’

So they dragged him off to a great room at the front of the house, where the master, who was a Justice of the Peace, sat smoking; and they told the gentleman how for a long time they had been missing choice food and good wine, but dared not report the loss to him lest he should think they themselves were the culprits. But this morning they had found the real thief – caught him red-handed they had, coming up from the cellar, and here he was.

Now the rich gentleman’s duty was to punish all wrongdoers, and the penalty for stealing was death. It was no surprise to him that the thief was so young, because many of the criminals he punished every day were children no older than this one; and though he was not by nature a cruel man, he thought it only right and proper that he should protect his own and other people’s property. Besides, in this case the hardened and dangerous little criminal had actually been robbing him of some of his best French cognac and claret!

He asked the still-dazed and trembling child who he was, where he came from, and how he had got into the house. When the child replied, ‘Down chimney’, the gentleman boxed his ears for his impudence, and roared, ‘Hang him! I sentence him to death by hanging!’

The village crier cried the details of the execution, which were that a dangerous malefactor was to be hanged on the gibbet on the village green at eleven of the clock in the morning three days hence. When the boy, trembling with terror and crazed with fear, was led out to be hanged, a huge crowd had gathered, as they always did in those days to see the fun. They put the child in a cart, and drove him up to the place where the gibbet stood, with the terrible noose of rope already dangling beneath it. Then the hangman climbed into the cart, and fastened the noose tight round the poor boy’s throat. He was just about to click his tongue, to set the horse moving and to leave the child choking in mid-air, when a hustle and a bustle among the crowd attracted his attention. A little old woman, wearing a white cap, and carrying a similar one in her hand, was pushing her way to the front of the crowd.

‘Hold, hangman, hold!’ she cried. ‘Alas, poor child, that he should die uncovered! Of your mercy, good hangman, let me place this cap on his head and over his eyes before you drive on the cart!’

The hangman could see no wrong in granting such a request, and helped the small woman to scramble on to the cart, and come to the side of the poor young prisoner.

No sooner had she set the cap on his head, than she cried, ‘Here’s off!’ and like an instant echo, the boy said, ‘Here’s after!’

Then the hangman stood looking at the empty noose, above an empty cart, while the crowd surged forward crossing themselves and murmuring darkly about witchcraft.

But the boy was back in the little turf hut in the forest, safe and sound if a bit shaken by his terrible experience. The two little fairies made much of him, though scolding him severely for what he had done to offend them.

First, they said, if you are befriended by fairies, as he had been, never take advantage, as he had done, by borrowing anything, such as the white cap, without invitation or permission. Secondly, when offered food or drink, never be greedy, for greed is a disgusting sin to fairy and mortal alike, and leads inevitably to drunkenness, poverty and crime as time goes by.

‘But he is young,’ said one to the other.

‘And he won’t do it again,’ replied the second.

‘He knows better now,’ said the first.

‘Let’s take him home,’ said the second.

So they put on their little white caps again, and placed the third on the boy’s head.

‘Here’s off!’ said one.

‘Here’s after,’ said the other.

‘Here’s after, too,’ said the boy, and in a jiffy he was lying in his own cot again, with his father and mother and brothers and sisters all mightily glad to see him, though a little inclined to disbelieve his extraordinary account of his adventures during the three days he had been missing. And who can blame them!