The eighteenth century was, as both history books and historical novels inform us, at once a robust and a romantic one, a cruel though an elegant one, and one in which there was a great gulf between the highborn and the lowly, except when those born to great estates backed the wrong political horse. Both the following tales belong to that century, and the lives of the two protagonists must have overlapped by several years.

Folk memory in this case has served to clothe the skeleton of historical fact with warm and vital flesh and blood, bringing home as no history book ever could the kind of awful individual tragedy that followed the risings of 1715 and 1745.

The devotion of the Radcliffe family to the Stuart cause is hardly a matter of wonder. The ill-fated Earls of Derwentwater were, in fact, the natural grandsons of King Charles II their mother (who was known as Mary Tudor) having been the illegitimate daughter of ‘the Merry Monarch’ by the actress Moll Flanders.

The young Earl of Derwentwater lived in his beautiful mansion on Lord’s Island, with his lovely wife and his little son. He was rich beyond the ordinary – indeed, it was rumoured that his income was greater than that of the Electorate of Hanover!

The family were staunch members of the Catholic faith, however, and their hearts were with the Stuart cause. The earl had a brother, whose name was Charles, and of whom he, as head of the family, was guardian. A Continental education was at that time beginning to be de rigueur for members of the aristocratic class, and the earl saw to it that his younger brother was given full advantage of the chance to travel. While in France, Charles spent much of his time in close association with the exiled Stuarts. The earl, perforce, remained at home to care for the estates in the Lake District. By the time Charles returned to England, dangerous matters were afoot; the Pretender had determined to make a bid to recover the throne.

Both the Radcliffe brothers were heart and soul with the Pretender, though the younger was perhaps the more eager of the two, having a personal attachment to the prince as well as a political and a religious one. The earl, still only twenty six, was soon in the field with Forster of Northumberland, and his brother with him.

According to all accounts, they were of the very flower of English manhood – strong, healthy, handsome, highly educated, witty, exquisitely mannered, wise beyond their years and above all gallant and courageous. They did their best to influence the course of the campaign, both opposing the foolish and wavering counsels that led the Pretender nearer and nearer to defeat, and in the event resulted in the capture of most of the leaders after the battle of Prestonpans, of whom more than a hundred were condemned to death at once. Among them was the earl. Hearing the terrible news, his countess left her home and set out to ride to London, to plead for his life or to bargain with anything and everything she had to offer. The only clemency granted to him, however, was the privilege of dying by the axe instead of the rope – a doubtful privilege, but of the hundred or more who died, he was the only one to whom it was given.

His estates were reduced to a fraction of their former glory, and the title lapsed. The house of Derwentwater suffered severely for its part in the rebellion, and the Countess with her son now had no one to look to but Charles, who, though he had been taken prisoner at Prestonpans, still lay in prison in Newgate.

Time after time the case of Charles Radcliffe was brought up; time after time he was sentenced to death, only to be given yet another respite at the last moment. His close confinement irked his eager, gallant spirit far more than the prospect of death. He began to despair of pardon, but the thought of a lifetime in captivity was more than he could contemplate. He set his mind to devising a plan of escape from Newgate – after which, let come what might.

Conditions in the prison for those with means were livened by the fact that food and drink could be brought in to them, and friends and relatives visit. Bribery of turnkeys and gaolers to secure these privileges was rife and accepted by all.

Charles made his plans carefully. He joined with his fellows in the gaol to provide the wherewithal for a riotous party, and gaolers as well as guests were well supplied with potent liquor. One man alone kept his drinking to a minimum, and his head as clear as need be. When the moment came, he succeeded in eluding his gaolers and escaped – free from the confining prison walls, but at large in London where anyone who recognized him could give him up at any minute to certain death. Courage, the thrill of adventure, the heady sense of freedom after long confinement, and a burning desire to outwit his enemies combined to keep him alert and cool-headed. He succeeded in eluding all the immediate hue and cry for him in London, and then, when it began to die down a little, he slipped away and went to ground among friends in the country. Little by little he moved towards the coast, until at last he managed to take ship to France. Straight to the French court he made his way, and was well received. Once established there in safety, he acquainted the countess and his young nephew at Derwentwater with his whereabouts, and asked for some maintenance allowance from the estate, in order to be able to keep up the honour of the family in the splendour of Louis XV’s court. The allowance seems to have been granted willingly, but before long the young nephew died. Charles, now head of the family, was then left with little succour. He assumed the title, however, because had it not lapsed, he would now have been the rightful Earl of Derwentwater. In France, there was nothing to prevent him calling himself the Comte de Derwentwater, so he did; and looked about for another way of improving his fortune.

His choice fell upon a widow whose late husband had been by no means poor and certainly not mean with his relict’s endowments. Nowhere does the story give us any idea as to the lady’s age or personal qualities. Maybe she had had enough of marriage in the first place, and preferred her well-endowed independence; or perhaps Lady Newburgh was not in the first bloom of youth and beauty, and regarded with some suspicion the attentions of a gallant as young, as handsome and in general as physically desirable as Charles Radcliffe. Whatever the reason. Lady Newburgh declined his ardent wooing.

Nothing daunted, our young hero returned to the attack, only to be repulsed again – and again – and again. After his sixteenth attempt, the lady felt that enough was enough, and gave orders that under no circumstances was he thereafter to be admitted to her presence. That would seem to have settled the matter once and for all. But the gallant who had survived Prestonpans, escaped from Newgate and eluded pursuit across England was not the man to be defeated by a woman’s word.

Lady Newburgh was seated alone in her apartment one evening when she was much alarmed by strange rattlings and knockings for which there seemed to be no immediate explanation. As she listened, half in superstitious dread but more in anxiety as to whatever should be the practical cause of such a disturbance in her household, it became clear to her that the extraordinary noises were coming from the direction of the chimney-piece within her private room; and before she had had time to summon help, or do more than rise to her feet in agitation, a pair of shapely legs appeared in her view, to be followed immediately by the elegant, if somewhat soot-besmirched form of her lover.

The audacity of his novel approach to make his seventeeenth offer of his hand tickled the lady’s fancy and weakened her resolution. She submitted at last to his entreaties, and became his wife. Ballasted by her fortune, for a number of years he lived on in France, ‘the glass of fashion and the mould of form’, till he reached his fortieth year.

But men born to English soil have never been entirely happy in exile, and Charles Radcliffe longed more and more for the sight of the beautiful fells of his lakeland home. At last temptation became too strong for him, and leaving Paris behind he set off, incognito, for England. He made his way straight to Derwentwater, where no doubt some ancient retainer of the family hid him and kept his secret. As soon as it grew dusk, he ventured out, and wandered lovingly round the neighbourhood of Gilstone and his former home, and the grounds once so beautiful and well kept, but now neglected and overgrown with weeds and bushes. There, among the trees in the moonlight, he was seen by several of the natives of the place, who remembered only too well their late unhappy master. The resemblance between the brothers had always been strong, and the years had served only to make the features of Charles more and more like those of his older brother. The peasant who first caught a really good view of him walking among the trees in brilliant moonlight took to his heels and fled to his cottage, gibbering in fright and declaring to all who would listen that he had, with his very own eyes, seen the ghost of the beheaded earl. The news spread like wildfire from cottage to cottage, and those who had caught even so much as a fleeting glimpse of the figure now came forward to corroborate the story. The dead earl’s ghost was undoubtedly walking, and it could bode no good. Thereafter, all gave the area as wide a berth as possible, and only those who had pressing business could be induced to venture there, even in broad daylight.

The safety thus afforded Charles both suited his purpose and appealed to his sense of humour. He enjoyed being his brother’s ghost, and as, in time, he began to lack amusement, he called upon his ghostly character to provide it.

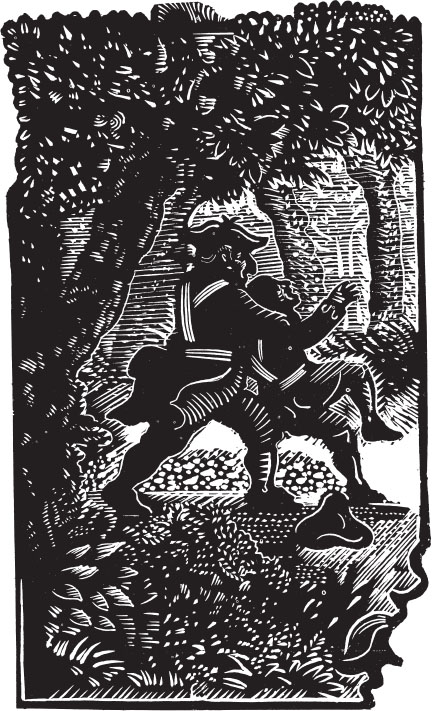

Among those who were forced by their occupation to visit the neighbourhood of the deserted mansion were the bailiffs into whose hands the administration of what was left of the estate had fallen. Having observed on which day and at what time the bailiff was wont to make his rounds, Charles took horse and awaited him among the trees. At first he merely followed from a distance, till the bailiff, uneasily sensing a presence behind him, urged his horse to a trot. Charles did likewise, and closed the gap a little. Then the bailiff turned and looked behind him.

In terror, he set his horse to a gallop, and his ‘ghostly’ pursuer did likewise. The abject bailiff, bemused with fear, drove his horse blindly among the trees. A low branch caught him at full gallop, knocked him out and swept him from his saddle with a thump to the ground. When he came round, the ghostly rider was nowhere to be seen. The bailiff mounted his own nag and made off to the nearest inn for company and refreshment. There he recounted his experience with a lot of extra detail, coming to the moment at last when, according to him, the dead earl had almost caught him up. At that point, said the teller, he had turned to face the ghost; but the earl had whipped off his severed head with his own hands, and hurled it, as a missile, straight at the bailiff. It had struck him with such force that he had been knocked unconscious from his horse. When he had recovered, nothing was to be seen of his dread pursuer or the extraordinary projectile that had caused his downfall. One thing, however, the bailiff was quite sure about. He would not venture again where he might confront the spectre, even if it meant losing his job. Nothing and nobody would or could ever induce him to set foot in the region again!

It so happened that amongst the company listening to the bailiff’s tale was a fellow bailiff. He scoffed heartily at his colleague’s report, jeered at his terror, and declared roundly that he didn’t believe in ghosts.

‘I wish I might be sent,’ he said, boldly if rashly. ‘I’d soon prove what a bushel of lies it all is! Nothing but shadows and fancy, that’s all that ghost is!’

He was granted his wish. When about to set off, he assured all those present to witness his brave departure that he still held to what he had said – he didn’t believe a word of it. But nevertheless, he would go armed.

‘And you may depend upon it,’ he said, ‘that if any ghost dares to cross my path, I shall put a ball through it!’

It was not long before his courage was put to the test. Charles watched him approach, keeping himself well hidden among the bushes by the side of a ford he knew the rider must take. He waited till the bailiff was in mid-stream, then sprang out. Before the astonished rider had time to recover his wits, Charles had met him, seized his horse’s bridle, and landed such a thump on the bailiff that it hurtled him head-over-heels out of the saddle and into the water. Before he had regained his feet, his assailant, whom in the fleeting seconds of their encounter he had recognized beyond doubt as the dead earl, had gone. The second bailiff’s tale lost nothing in the telling, any more than that of the first had done. The ghost reigned supreme.

But the terror continued to grow among the villagers, the tenant farmers and their labourers. Nobody would venture out, even to till the land, and the situation began to be very grave indeed. At last the steward, speaking for the entire neighbourhood, demanded help and protection from local authority, and in the king’s name a posse of soldiers was sent to scour the countryside. As Falstaff had declared, the better part of valour is discretion, and Charles knew the old saying to be a wise one. Bailiffs were one thing, and redcoats another. He put as much distance as he could between himself and Derwentwater in the space of the next few hours, and was soon on his way to Holland, and from thence went back to France. The soldiers, of course, found neither ghost nor man, but were nevertheless given all the credit for successfully laying the dreadful apparition, and the district returned slowly to normal.

Back in France, Charles Radcliffe sought service with the French king, and continued there in some capacity of military adviser for a number of years. He was by this time well into his forties, and had sons of his own already grown to manhood. His presence at the French court naturally brought him into contact again with the Stuarts, and when Bonnie Prince Charlie launched the second rebellion of 1745, it followed just as naturally that what remained of the House of Derwentwater should be in the run of it. With his eldest son at his side, Charles Radcliffe set out once more for England, to help reinstate what he regarded as the rightful king on the throne, and to strike a blow for the Catholic faith.

This time his luck had run out. The ship in which he was travelling was captured at sea by an English frigate, and he was bundled with little ceremony into the Tower. And there he stayed, for more than a year, while the cause for which he had risked his all collapsed in ruin and slaughter, this time for ever.

The difficulty in disposing of him lay in the fact that he was, undoubtedly, a French officer. He did not own up to the name of Charles Radcliffe, saying instead that he was Le Comte de Derwentwater, and referring to himself always and only by that name. His demeanour was haughty and contemptuous. He seemed very little like the Charles Radcliffe who had been convicted thirty years before. Though suspicion was very strong in official circles that their disdainful prisoner was indeed the escaped Charles, it was for them to prove it, before they executed one of the French king’s own men.

It was, in the end, some of his own neighbours from Gilstone who sealed his fate. Brought down to London from their lakeland quietude to view him, they identified him beyond all reasonable doubt. Even feudal loyalty broke down under the exigencies of civil strife in which everybody had suffered. Culloden with all its horrors was still only weeks into the past.

So the Comte de Derwentwater was condemned to die, like his brother before him, on the scaffold. He was fifty-three when they led him out, still handsome, still elegant, still gorgeously apparelled, to his death. His proud, courageous bearing was as serene as ever, his voice unfaltering as he made his final preparations and said his last few words to the public.

He professed himself to be dying a devout and true member of the Catholic faith; he declared his duty and devotion to King Louis XV of France, in whose service he still was; and he reserved his last words to speak of his utter devotion to his rightful king, Charles Stuart, the Young Pretender.

Then he turned upon the masked executioner the full charm of his smile, as he handed him a purse containing ten guineas.

‘I am but a poor man,’ he said, ‘or your fee should be a worthier one. Do your work well!’

On the mercurial ghost of Gilstone and the last proud lord of Derwentwater the axe fell clean and true.

Another gallant Englishman had died for his principles. One blow was enough.

The death of a drummer boy and the conviction of his murderer many years afterwards as the result of supernatural events caused a nationwide stir. The background to this tale is discussed in the general introduction.

Between Alconbury and Brampton Hut in Huntingdonshire (now part of Cambridgeshire), where the Al, formerly the Great North Road, still runs, there stood for many years a post which all the local inhabitants called ‘Matcham’s [sic] Gibbet’. It fell into decay about 1860, and had to be taken down; but it is fairly safe to state that it was the actual gibbet upon which Gervase Matchan hung in chains for the crime which led to the legend remembered all over the county – indeed, all over the country. The criminal did, in fact, make a full confession before his death to the Rev. J. Nicholson of Great Paxton, and at a later date another clergyman, the Rev. R. H. Barham sent the details to Notes and Queries, from whence they were taken for the ‘Dead Drummer’ story contained in The Ingoldsby Legends. Matchan’s own story was as follows.

He was born into a fairly well-to-do family, at Fradlingham, in Yorkshire, where his parents lived a calm and peaceful, if unexciting rural existence. The boy found it too dull for his liking, for from his infancy he showed a tendency to headstrong likes and dislikes, a turbulent nature and a longing for adventure. When he reached the age of twelve, he cut loose, and ran away from home. He found work as a stable boy with a Mr Hugh Bethel, of Rise, and later, after five years, as a jockey with a Mr Turner, well known in the racing circles of that time. At this point in his career, a great adventure came his way. He had by this time a good deal of knowledge and skill in the business of horse dealing, and was chosen by the agent of the Duke of Northumberland to accompany a present of horses that nobleman was making to the Czar in Russia. He enjoyed the trip very much, particularly the time spent at sea, and returned to England with the fixed intention of thereafter becoming a sailor. He joined a ship of the line as an ordinary seaman, and almost immediately made a voyage to the West Indies; but the difference between being a matelot in the navy of the day and a passenger on his way to the Czar was more than he had expected, and more than his turbulent spirit could endure. He left the service as soon as he could, and decided to try soldiering as an infantryman instead. Military discipline, he discovered, was as bad as the naval variety, and just as irksome. While stationed at Chatham, he persuaded another private in his regiment to join him in a bid for freedom.

They managed to escape without detection at night, and as soon as possible broke into a gentleman’s residence, where they helped themselves to a suit of civilian clothes each. They then buried their uniforms, and went on in a fair degree of assurance that they would not be recaptured. As Matchan was already so familiar with the racing fraternity and its ways, they trudged about the country, coinciding where they could with race meetings, at which Matchan could generally pick up something to keep them going as far as the next. In this way they came to Huntingdon races. Here their luck very nearly ran out, for they were actually arrested, and accused of being deserters; but Matchan had a glib tongue, and furnished the authorities on the spot with such a plausible tale that he was believed, especially as it was observed how little of a military bearing either of them showed. So they were released; but the effect of the scare had been very severe on both of them. They parted company, and Matchan went on alone. Now, however, some of his bravado had deserted him. He was in constant fear of being picked up again as a deserter, and this prevented him from finding work to feed himself. His solution to the problem was certainly an ingenious one. He decided to re-enlist in a different regiment, which he did, and became once again an infantryman, this time in the 49th regiment of foot, then stationed near Huntingdon.

He had not been long in this role before he was chosen for a special mission, perhaps because of his ‘tough’ nature. The Quartermaster-Sergeant, whose name was Jones, had a son of his own in the regiment. Benjamin Jones was a drummer boy, and was, at the time, about fifteen years of age. The Quartermaster-Sergeant was in the habit of employing his young son to fetch the subsistence money for the troops from Major Reynolds, who lived at Diddington Hall. Matchan was selected as the boy’s escort, and on 18th August 1780, the two set out. The boy received from the major the sum of £7 in gold, and they started on the return journey. It seems strange that the drummer-boy, who had supposedly made the journey previously, should have been tempted out of the direct route, but Matchan, as we have seen before, was persuasive of tongue. However it was, they took a wrong turn, and went on as far as Alconbury. There they stayed the night, and in the morning turned again towards Huntingdon.

As they trudged along side by side, Matchan’s thoughts turned again and again to the gold his companion was carrying. Were it not for the boy, he could appropriate the money, and with it be free of the army, and of England, before the law could catch up with him. He was a man of violent passion and as quick to action as to thought. They were just coming up to a copse that stretched on each side of the road, a little way from Creamer’s Hut (now Brampton Hut). Matchan suddenly turned and seized the boy, dragging him off into the trees, where he slit this throat with his pocket knife, and relieved the corpse of the purse of gold. He hid the body as well as he could, and went back to the road, retracing his steps through Alconbury, then on to Stilton and Wandsford, where he took the precaution of fitting himself out with a new suit of clothes. He then turned towards Stamford, from where he booked a seat on the York coach, and travelled towards his boyhood home at Fradlingham. He found only his mother living, and nothing to be gained there, so he made at once towards the coast, where he intended to take ship as soon as opportunity offered.

Once again, luck of a strange nature altered the course of events. He had no sooner reached the coast than he fell victim to a press-gang, and willy-nilly he found himself again at sea as a sailor in the navy! At least he was in no danger there of being apprehended for the murder of the drummer-boy whose body had not been found for several days, by which time Matchan was away from England, whether he would or no. He was engaged in several naval skirmishes over the next few years, being discharged at last in 1786 – six years after he had committed his crime. He felt safe from detection, and began his wandering life once more, in company with another discharged sailor.

One evening in the late summer of that year, the two were crossing Salisbury Plain when the sky darkened ominously, and a most violent thunderstorm broke over their heads. Men who had been in battles at sea were not very likely to be afra id of thunder, but it seems that the crashes were beyond anything they had ever experienced before, and the lightning absolutely terrifying. It was in a most prolonged and vivid flash that Matchan saw in front of him a spectral figure, which appeared to be that of a deformed and bent old woman. At once Matchan’s guilty conscience rose to accuse him, and almost gibbering with fright, he pointed the figure out to his companion. Strange to say, in the light of the next flash his companion, too, saw the spectre quite clearly; but as he happened to have no crime on his conscience, he reacted to it in an entirely different way from Matchan. He seized a stone, waited for another flash of lightning, and hurled the stone straight at it. His aim was true. The stone passed through the figure, which then sank into the ground and disappeared.

Both men were now thoroughly alarmed, and the other sailor concluded that one or other of them had offended against the holy laws of God, and broken one or more of the commandments. As it was quite likely that either could have done so, they decided to walk separately so that if either had other strange experiences it would point him out as the guilty man, and he could search his conscience with a view to making amends before it was too late.

They had not far to go. Walking along the road, one behind the other, they passed a boundary stone. When Matchan’s companion passed it, nothing untoward happened; but when Matchan approached, it rolled over towards him and glared at him with huge, staring eyes. So did every other boundary and milestone on the road.

Terrified now as only a guilty conscience can make a man, Matchan desired that they should stop at the next inn and take refuge and shelter there. It was not long before a wayside inn came into view, and Matchan hailed the welcoming comfort of company with relief. However, when they had almost reached it, he found a remarkable obstruction between him and the door. On one side of the road down which he must pass stood the figure of Christ; and on the other side stood Benjamin Jones, in his uniform, and with his drum at his side. Matchan passed between them, and entered the inn in a state of collapse.

When questioned as to the reason for Matchan’s condition, his companion related the dreadful experiences they had had since leaving Salisbury Plain. Every eye turned accusingly on Matchan, who began then to blurt out the whole story of his crime. He voluntarily gave himself up to the law officers, without struggle, and was brought before a magistrate at Shewsbury, who committed him for trial at Huntingdon Assizes. He was condemned to death, and after execution, his body was to be hung in chains on a gibbet at the scene of the crime as a grisly warning to others that, however long the interval between, ‘murder will out’.

The Reverend E. Bradley, who, under the pseudonym of Cuthbert Bede, was a frequent contributor to Notes and Queries, gave the following particulars of the gibbet as he gathered it verbatim from an old man who had acted as an ostler in former days at the coaching house on Alconbury Hill.

‘I mind,’ said the old man ‘the last gibbet as ever stood in Huntingdonshire. It was put up on the other side of Alconbury, on the Buckden road. Matcham [sic] was the man’s name. He was a soldier, and had been quartered at Alconbury; and he murdered his companion, what was a drummer-boy, for the sake of his money. Matcham’s body was hung in chains, close by the side of the road, and the chains clipped the body and went right round the neck, and the skull remained a long time after the rest of the body had got decayed. There was a swivel on the top of the head, and the body used to turn about in the wind. It often frit me when I was a lad, and I’ve seen horses frit by it, as well. The coach and carriage people were always on the look out for it, but it was never to my taste. Oh yes! I can mind it rotting away, bit by bit, and the red rags flapping from it. After a while they took it down, and very glad I were to see the last of it.’