CHAPTER 8

ENGAGEMENT

WHAT IT'S ALL ABOUT

- What strategy engagement is

- Why it is important

- How to engage the organisation collaboratively

- Why engagement doesn't stop at the decision

- When a more collaborative approach is important

- Leadership and culture

In previous chapters much has been said about the concepts and tools involved in strategy-making, how the process must reflect the required level of ambition and precision and enable an objective analysis of the options. However, this will not suffice to create a successful strategy; the people involved in design and implementation must be emotionally engaged. This chapter explains why and how to achieve what is called ‘strategy engagement’.1

‘Engagement’ is the new buzzword: employee engagement, community engagement, stakeholder engagement. But what does engagement mean in relation to strategy, and is it more than just a fad and fashion? Is there really something important here?

WHAT STRATEGY ENGAGEMENT IS

A widely acknowledged problem in organisations is getting people to understand and act on the strategy. Senior management teams often create a strategy but then find that it is hard to get others on board.

Two different types of strategy engagement have emerged to address this problem. The first, persuasive engagement, seeks to get ‘buy-in’. In persuasive engagement, someone already has a plan or proposition and wants everyone to agree to it and to make it happen (i.e. to become engaged in doing it). Persuasive engagement is appropriate when all strategic initiative and insight can be generated by the top management. It has a place in some situations and is still common in many organisations. It keeps strategic thinking confined to a small group, and then asks a larger group to get energised about something someone else has thought of. Trying to get buy-in means selling the idea to someone else, with the risk that it will under deliver. For this reason, and because it does nothing to improve the quality of strategic thinking, we will not consider it further.

WHO SAID IT . . .

“Only 5% of employees understand their company's strategy.”

– Robert Kaplan and David Norton

This chapter is about collaborative engagement, which seeks to get people to provide input to the development of the strategy. As Nilofer Merchant puts it, it is an approach to engage all of the company ‘not after the process, during the process’.

Collaborative engagement can take many forms:

- It can be a specific initiative at a time of significant organisational repositioning. This could involve getting a project team from across the business engaged in developing a strategy to enter a new market or grow through acquisition.

- It can also involve getting very large groups – even hundreds of people – to provide input into the creation of a new strategy for the organisation. Global not-for-profit healthcare organisation The Cochrane Collaboration undertook just such a process, which is described later in this chapter.

- There is also the continuous refinement of a strategy involving many people, for example, the ‘Work-Out’ approach developed by GE. This involves training groups in the skills required to identify and implement operational improvements to their businesses. In the early 1990s, over 200,000 GE staff participated in these sessions. In his autobiography, Jack: What I've Learned Leading a Great Company and Great People, CEO Jack Welch recalls a comment from a worker who told him, ‘For 25 years you've paid for my hands, when you could have had my brains as well – for nothing.’ While operationally focused, Work-Out played a key role in implementing GE's strategy of becoming the number one or two player in every market in which it competed.

What all the different forms of collaborative engagement have in common is that they seek to engage the participants emotionally, as well as practically and intellectually, right through the strategy process – not only during implementation or ‘execution’.

WHO SAID IT...

“ Strategy is... organised and purposeful collective action. ”

– Gary Hamel

WHY COLLABORATIVE ENGAGEMENT IS IMPORTANT

The level of engagement affects the quality of strategy because our brains focus on what is emotionally engaging. People in organisations are faced with all sorts of pressures, commitments and deadlines. Attending to strategy is only one of those pressures. Recent research in neuroscience has revealed that, to a significant extent, people decide where to focus on the basis of their emotions. For example, when faced with the choice of spending time on strategy, meeting this month's financial targets or going home a little earlier than usual, our choice will be based on what is emotionally appealing – what tickles the limbic system, which is the part of our brain responsible for registering and dealing with emotions. Moreover, the limbic system tends to operate at an unconscious level because it developed in our distant mammalian ancestors – so the choice about where to spend time can escape the auditing and critical review of the conscious brain. The brain chooses without deciding.

Emotional engagement with strategy is not too difficult to achieve if only a small group is responsible for its development, but if a large number of people are to be involved then it is a greater challenge. For this reason, large-scale collaboration is the primary focus of this chapter, although the benefits, principles and techniques also apply to a smaller group.

The first benefit of large-scale collaborative engagement is that it usually generates more and better ideas. When strategy is created it is common for those involved to be left with the uneasy feeling that they haven't made the best use of the minds, imaginations or collective know-how of people inside and alongside the organisation. Good collaborative working makes the most of the amassed wisdom and day-to-day knowledge of all those involved, including those closest to the customer and products, for example in the sales team, the complaints department and the factory.

The second benefit is that it improves the chances of the strategy being implemented effectively. When strategy is dreamt up at the top of an organisation and then cascaded down, a gulf of understanding and ownership opens up – a phenomenon that author Nilofer Merchant calls the ‘air sandwich’. In other words, there is a strategy with clear vision and direction from the top layer which people lower down then try to implement, but there is a gap between the two. Those responsible for implementing the strategy do so without really connecting the actions they are taking on a day-to-day basis with that vision or direction. However, if more people are involved, by using a collaborative process, there is a greater likelihood that a wider number will understand the overall objectives and logic of the strategy, and be motivated and able to adapt its implementation as conditions evolve.

Collaborative engagement also provides a powerful mechanism for learning together, developing the overall strategic capacity of the organisation and growing the capability of the next generation of leaders. By moving strategy beyond an annual ritual and into a vibrant part of organisational life, people are more alert to how it relates to their jobs. If they are confident that the mechanisms and processes exist through which their messages can be heard and acted on, there's a greater likelihood that these ‘eyes and ears’ will be willing to serve as an early warning system.

WHO SAID IT . . .

“As long as we're eating air sandwiches we lack the way to know precisely how to do an effective job of setting direction and achieving the kind of results we need.”

– Nilofer Merchant

Perhaps the most important benefit of collaborative engagement is that it increases the likelihood of the organisation being able to respond to unexpected and unpredicted changes as the strategy is implemented. A lot of writing on strategy still holds to the idea that if you plan it, it will happen. In fact, as discussed in Chapter 1, the more we understand about how strategies develop in practice, the more we see that they evolve – developing through a series of changes in circumstances and small decisions in ways that could not have been foreseen.

This doesn't mean that analysis, planning and intention have no role; far from it. These activities are important in setting direction, and the skills they require are critical for knowing how to respond to the changing situation. But it does mean that however skillfully you craft your plans you need to be alert to how a complex, connected and changing world can mess them up in unexpected ways. The more you engage people throughout the process, the more able they are to play this responsive and responsible role at all times.

HOW TO ENGAGE THE ORGANISATION COLLABORATIVELY IN CREATING OPTIONS

Irrespective of whether your strategy is created by just one or two people or by a wider group, the strategic concepts and tools used to analyse and develop strategic options are the same. What changes is the number of people involved in the conversations around the analysis. This can range from small senior or cross-functional teams of fewer than 10 people to comprehensive organisational conversations involving many.

To work out who to involve (and how many) you need to think about a number of different factors:

- How can we get a range of perspectives into this thinking?

- Who always asks the difficult questions that would help stimulate our thinking?

- What are the practical considerations that need to be taken into account (time, budgets, locations, technologies)?

- Who are the people responsible for acting on the strategic goals that emerge from this process?

If, as a result of the answers to these questions, it has been decided to include a larger number of people in the option creation process then it is best to create a number of different teams and allocate a different question or questions to each for further investigation, based on themes that have usually been defined by the board or executive team. Some teams might prioritise external inquiry while others might look at things from the inside out, thereby allowing them to challenge assumptions and ‘stuck’ patterns of thinking that they see within the organisation.

For example, in a strategy process for a cosmetics company, groups were established to look at issues including macro-economic and social trends over the next five years, present and future competitors, customers and shoppers, present and future consumers, brands and categories. When you are thinking about group size, typically five to eight members (including a group leader) should provide a balance between the practicalities of getting the work done and a good range of opinions in response to the questions on which you are seeking insights. While it's important to be clear about the ‘big question’ for each group, don't be so prescriptive about the details of every sub-question that you prevent the group from exploring something of interest that hasn't been included.

It's good to include the mavericks in your process. In deciding the composition of strategic inquiry groups during such a process in an international engineering consultancy, the MD said, ‘We must make sure H is in one of the groups – he's always asking really tricky questions.’ In our own research, one recipient described his role in strategy specifically as being ‘an agent provocateur to the board....’ – asking the questions that the CEO wished he hadn't. It may be difficult to handle the questions that result, yet these dissident voices often provide vital insight into opportunities and risks in both the internal and external environments.

PRACTICAL TIPS ON GENERATING ENGAGEMENT

Practical considerations include thinking about how much time and budget you have. If the group is very large, this may not permit a face-to-face encounter but there are many virtual ways of gathering input (such as online meeting platforms). It is possible to involve large groups of people in quite a short timeframe, so long as the process is well thought through and creatively designed. As an illustration, consider The Cochrane Collaboration, founded in 1993 as an independent, not-for-profit organisation of over 28,000 contributors from more than 100 countries and dedicated to promoting evidence-based healthcare by making independent evaluations of current medical and health research available worldwide. With so many volunteers so widely spread, how could they be engaged in a review of the organisation's strategy? Seven inquiry dialogues were set up, with a series of interviews by phone and intranet surveys open to any contributor to The Collaboration which, when combined with an interactive exhibition space at their annual conference, resulted in over 3,000 people inputting to the strategic intent.

If there are several groups, all working on different issues, it is important that they not be exclusive and closed, but porous and inviting. Make sure that your work groups know they can invite others to share their insight into their area of inquiry. In the cosmetics company mentioned previously, the macro-economic team used an external agency to provide more in-depth information about expected societal trends, while the competitor team interviewed new hires recruited from competitor organisations to supplement data from desk research.

SHARING FINDINGS

If many people are involved then there must be a particular emphasis on communication. Each group needs to know something about the findings of the others. Groups should be encouraged to talk to each other if they discover something that might be useful to another group or believe they have overlaps in their thinking. Collaborative engagement means just that!

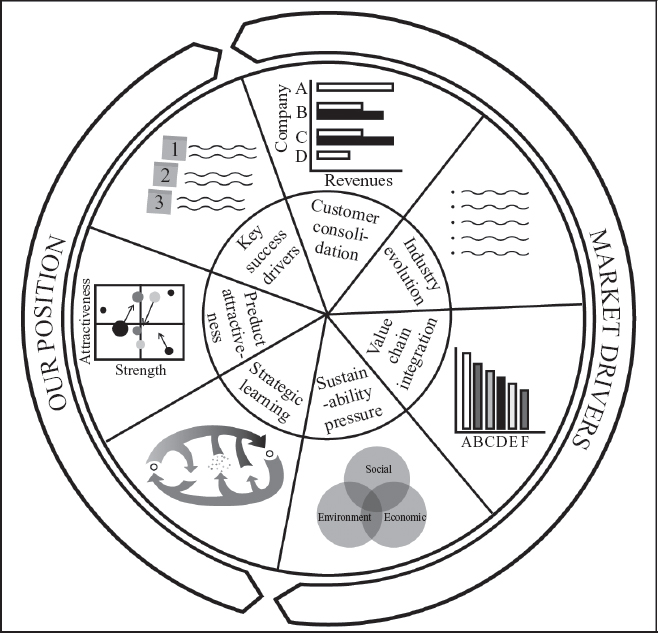

Given the mix of backgrounds of the people involved, forms of communication should not be restricted to those typical of strategy processes in large companies. If you think about the outputs of strategy work done in your organisation, what comes to mind? Almost certainly it will be some kind of report – most likely presented as a series of PowerPoint slides. But there are other ways of representing strategic exploration, from the traditional slideshow to poster exhibitions, photo montages, stories, poems and ‘street theatre’ productions. The following example shown is based on one produced by a company reviewing its five year strategy. Out of five inquiry groups set up by the Board, one was tasked with assessing market position. Each group was asked to bring their findings to a one-day workshop in a way that could be shared and added to by others attending. The market position group put their thinking (predominantly hand drawn) onto a large piece of brown paper. It was spread out on a table at the workshop and, through the course of the day, people stood around it, discussing and annotating the outputs.

The purpose of using a range of creative ways of representing data is not just to make the process interesting. Different ways of exploring and seeing data reveal new perspectives. A picture, a collage or a story can provide a different insight into the nature of a problem, a challenge or an opportunity.

Creative communication

These approaches can later be adapted to illustrate and communicate the strategic story to other parts of the organisation. For example, once further changes had been incorporated, the exhibit shown above was drawn up by the in-house graphics team. It was then used as part of the presentation to the Board and, from there, across the rest of the organisation as a way of telling the strategic story and the rationale for decisions made.

Communications also need to flow up the hierarchy. Throughout this process, the board or executive team keeps a watching brief over the inquiry work groups, deliberately avoiding giving their views on content, but usefully asking probing questions. In the cosmetics company, each team had a board sponsor who briefed the team on what was required at the beginning of the process, then met twice with the team leader during the six weeks they were collating and making sense of data. At those meetings, the board sponsors were given a brief update on progress, after which they asked questions to ensure sufficient depth and rigour was being applied (e.g. ‘How are you going to investigate competitor X? What impact will consciencel-ed shoppers have on us in the future?).

ENGAGING THE ORGANISATION IN CHOOSING AN OPTION

A comment often made by senior managers is that ‘Engagement sounds fine, but if we involve more people then they'll think that means they also have a decisionmaking vote.’ This is not the case. Organisations are rarely constituted as democracies. One of the reasons that senior people get paid more is because they have to take decisions and are legally accountable for the decisions they take. Nonetheless, there is a strong case to be made for engaging others in the decision-making process, not as decisionmakers but to keep the executive group as well informed as possible, to act as a critical friend or devil's advocate, or to challenge ‘stuck thinking’ within the senior group.

You can use people new to the strategy conversation, thereby widening the organisation engagement further, albeit with the downside that they will need to be engaged in the thinking that has already taken place (which may have a time implication). Alternatively, you can use those already in place from previous work.

WHO YOU NEED TO KNOW

Ron Heifetz

Ron Heifetz is a leadership expert and a graduate of Columbia University, Harvard Medical School and the Kennedy School, where he is currently the King Hussein bin Talal Senior Lecturer in Public Leadership. He is also a physician and cellist.

Heifetz distinguishes between technical tasks and adaptive challenges. Sometimes a strategic challenge is genuinely the former: familiar ground where existing experience and expertise can provide the answer. But usually strategy is more complex than this, and innovation in product, service or organisation is called for. Here, Heifetz argues, it is wrong for top leaders to claim expertise – a more collective intelligence and learning effort is needed. He argues that top leaders have to ‘give the work back to the people’.

The role of the leader is not to be the font of all strategic knowledge, but to create the space in which teams can explore, enquire and create solutions and approaches for a new future. Top leaders can't deliver it alone, so it's unwise to exclude the people who have to do the work from the process of exploring the solutions needed. Heifetz talks about the role of leaders as being to invite and support teams in engaging deeply in strategic challenges and the strategic learning that goes along with them.

With the cosmetics company, the team leaders were tasked to examine all the data and then act as a ‘shadow board’ to address the questions – ‘On the basis of what you've seen, what are the most significant strategic issues we face and how should we as an organisation best respond to them?’ Having done this, the shadow board met the main board to present their findings, which were taken into account in the latter's deliberations. The board was not bound by their suggestions, yet the additional insights helped to sharpen their thinking before they made their final decisions.

Such diversity is useful. It encourages issues and options to be seen ‘through multiple lenses’, minimising the problem of group think. This is especially so if the groups include divergent perspectives. It is, for example, possible to include key stakeholders such as suppliers, selected customers, investor groups and trade bodies in this process. (There is no reason that your engagement should stop at the company gate). Where issues are too sensitive to invite external parties into the room, it can be very powerful and creative to role-play the position of such parties in the options’ selection and evaluation process. Again, this tends to enrich the conversation and encourage decisions to be taken having looked from more diverse angles than the more familiar ones.

Gary Hamel

Gary Hamel is one of the world's most provocative business writers and speakers, and is highly sought after as an advisor and inspirer. A founder and chairman of Strategos, and Visiting Professor of Strategic and International Management at the London Business School, he has authored 15 articles published in the Harvard Business Review, the benchmark of success for a management writer.

Hamel's interests have roamed widely over the years, but have a common theme – the mobilisation of capabilities to achieve competitive success. His more recent thinking has focused on a capability of particular relevance to how strategy is developed – ‘human imagination and initiative’ – and its ability to help an organisation innovate and adapt to the rapidly changing business environment. He dreams of organisations where ‘. . . the renegades always trump the reactionaries’.

Hamel seeks to break the ‘ongoing tension between creativity and organisation’, encouraging managers to find ways to delegate more decision making down the hierarchy. He urges organisations to loosen the shackles that constrain their employees so that they can be engaged in the task of reshaping, building and directing their organisations. This approach is aligned with the ideas presented in this chapter.

As you might imagine, opinion is divided on the validity of Hamel's views. He is criticised by some for being impractical. What is generally agreed is that he has put his finger on a problem that many large organisations would love to solve. The question then is: Has Hamel provided a solution? In his own words, ‘My goal . . . was not to predict the future of management, but to help you invent it.’

Hamel and his co-author C.K. Prahalad have made other important contributions to strategic thinking, including the importance of strategic intent in motivating an organisation, and the development of capabilities and core competencies to build competitive advantage, even against entrenched competitors.

There are situations, of course, in which the situation is more democratic, such as where an organisation operates as a cooperative, collaborative or is employee owned. But even here decision-making authority is usually vested in a board or other executive group, perhaps with employee directors. Equally, there are situations when broadening participation in the decisionmaking process is much less appropriate. For example, when deciding on a market-sensitive acquisition where confidentiality is key, decision-making conversations rightly remain closely held by the most senior individuals in the organisation.

WHY ENGAGEMENT DOESN'T STOP AT THE DECISION

This is not a book about strategy implementation, so why include this section?

In traditional strategy thinking, the start of implementation is sometimes seen as the end of the ‘strategy’ process. The thinking and decision making are done and it is time to turn decisions into action. But, as described earlier, the strategy written down is virtually never the same as the strategy that actually develops over time. Unforeseeable events occur, competitors do unexpected things, new entrants arrive and circumstances change. The plans do not unfold as anticipated. Even your own colleagues can come up with ways of satisfying customers that you never thought of . . . and they work! So these become part of the strategy too. As Henry Mintzberg said, strategy grows more like weeds than cultivated prize tomatoes.

For this reason, the process of engagement does not finish with the rollout of the initial strategy. The awareness, attention and learning ability of the organisation needs to be harnessed in order to allow the strategic actions to be refined as the strategy adapts to changing circumstances. The more people are primed to act as the nerve endings of the organisation, noticing the tiny signals that this or that is happening, the more the organisation is able to react. It can still follow its plan, but does so intelligently and flexibly in an uncertain world.

The more widely the strategy is understood throughout the organisation, the more people are able to use their awareness and intelligence to adapt it as needed. They are also more alert to strategically important events and developments and bring these swiftly to the attention of the senior team. So a critical first step is to communicate your strategy effectively. But, despite its importance, there are many organisations in which most of its members are unsure what the strategy is.

Partly this is the age old problem of communicating any consistent message across all but the smallest organisations. But the problem is often compounded by the strategy being described in a way that is fuzzy and generic. The key is to boil the strategy down to something very simple, but also very distinctive.

A useful tool to use to develop your message is the strategy triangle – discussed in Chapter 2. This is composed of the three elements that your communication needs to include: The objectives of the strategy, the opportunities it is targeting and the capabilities that will be used.

The description of the objective can include both the specific objective of the strategy – such as achieving the number one spot in the market – as well as how that supports the organisation's broader purpose and mission. The opportunity, or scope of the strategy, should make clear the boundaries of the strategy – what you won't do as well as what you will. The capabilities should be expressed as the distinctive way in which you will achieve your objectives – rather than a bland list of generic ideas such as ‘excellence’, ‘people’ or ‘persistence’. Instead, state the characteristics that differentiate your approach from that of other organisations – your distinctive competitive advantage.

Distinctiveness is critical. Too many strategy statements could be used by a different organisation without anyone noticing! Test the distinctiveness of your communication by asking how each element of the communication differs from that of your competitors.

Another objective is to ensure a good flow of information about how the strategy is progressing. There are a number of ways to do this:

- Making sure that there are feedback loops built into every part of the organisation to report back on the progress of the strategy – what's working, what's not, what people are noticing, what's actually happening. This may mean specific meetings are set up to review the strategy (monthly, quarterly) or, perhaps more pragmatically, an agenda item at regular team/departmental/divisional meetings. The point is that it's an ongoing process that operates at all times in the life of the organisation. At one major UK charity, a specific aim of regular team meetings is to provide a two-way flow of information about the strategy as it takes shape on the ground.

- Formalising the skill and capability of strategic thinking by including it in competency and appraisal processes. If you pay the right kind of attention to this behaviour, you will get more of it. It's not just about recognition in the form of pay and advancement, it's also about what behaviours get praised, talked about and written up in the company newsletter.

- Encouraging awareness of the place of learning and feedback in the strategic process through the way senior managers demonstrate their own willingness to learn from what's happening. This also means an acknowledgement from such individuals (overtly or otherwise) that they cannot know everything that is going on in the organisation, and recognising the importance of strategic intelligence wherever it comes from. Without this type of senior sponsorship and involvement, strategic learning will not flourish in your organisation.

To hone this strategic intelligence it is important to develop the strategic capability of those in teams responsible for turning ideas into action. Again, this can be done in a number of ways:

- Start by developing awareness of the basic strategic tools and models used in your organisation's thinking. Some of the models introduced earlier in this book may already be in use. Familiarity with such tools and models is important – especially learning not to be baffled by the science (or apparent magic) of strategy. The tools are there to help you have a more focused conversation, to ask better questions in a complex world.

- A further step in growing strategic capability is to encourage people to develop a ‘strategic perspective’. This involves learning to spot potential connections between events (internal and external) and the organisation's strategic intentions. It means that, when you read the press, watch the TV news, or stumble across something interesting on the web, you think about the strategic consequences for your part of the business. It grows out of curiosity and is fed by conversations that come from having your eyes and ears open to what in the world might impact you, to your cost or advantage. This perspective can be encouraged through practice and by noticing that there are genuinely many ways to see, understand and think creatively. A good way of illustrating this comes from the cosmetics company. At the end of the options data-gathering process, the Director of Consumer Insights commented, ‘I realise that I should be thinking in this way almost all of the time.’

It's by paying attention to what's really happening that your organisation can respond to things that don't work out as you expected and exploit new opportunities that emerge that were never considered possible when the strategic intent was first worked up.

WHEN A MORE COLLABORATIVE APPROACH IS IMPORTANT

Sometimes a strategic decision is totally within the leader's or top team's expertise, and needs no exploring. In such circumstances it makes no sense to use a more collaborative approach. Simply own your expertise and take the decision. (You may of course want to think about how best to engage people in understanding the decision – that is the sphere of persuasive engagement and is about how well you tell the story – but the point is, you don't need a larger group to help you explore it). Never engage people in collaborative strategy-making when you have already made up your mind about the answer; it just makes them cynical and is bad practice.

But sometimes a strategic situation is beyond the expertise or experience of anyone – including senior managers and expert consultants. No single person can bring certainty; the organisation must draw on its collective intelligence, its ability to learn and experiment. It is in this context that the most developed forms of collaborative engagement become vital.

Another time to involve a broad group is when the implementation task is particularly challenging. For example, if it requires a detailed understanding of the rationale for the strategy, a deep commitment to implementation, a high degree of creative adaptation of the strategy, or a large pool of people with a strategic mindset, then involving many people can be essential.

LEADERSHIP AND CULTURE

Two themes run through these last three chapters on the strategy process, each worth a brief mention – although either could be the topic of a whole book.

The first is the role of leadership in designing, shaping and managing the strategy process. This is a two-way street. The leader needs to adapt to suit the process, and the process often needs to be designed to suit the leader. An important choice that leaders must make is the extent to which they roll their sleeves up and get involved in the task vs. managing the decision process at a distance. Both approaches are classic responsibilities of a leader and it is tempting to do some of each, but be careful not to think that you can handle both without risking a loss of either objectivity or careful management of the process.

If the focus is on managing the process, many of the more detailed activities described earlier can be delegated to a team leader, although they will require some senior involvement and oversight. A key role is to ensure that healthy conflict and debate is fostered without it spilling over into personal battles or acrimony. Depending on the group, this may be an easy or near impossible task. Any project leader whom you appoint may need assistance.

Another important role where you can help is to pace the overall effort and decide when to open it up to more ideas, and when to bring it to focus and closure. Strategy development is difficult and teams may get lost without some external guidance.

One final responsibility for leaders is to acknowledge that they themselves may be a major source of bias. They should assume that is the case and be open to, or encourage, safeguards that prevent them leading the strategy astray. Easy in principle – rare in practice!

The other theme running through these chapters is that different organisations have different cultures. Hence a particular style of strategy-making can be pleasure for one organisation and poison for another. An important issue, drawing on a framework developed by Rob Goffee and Gareth Jones, is how sociable your organisation is. The more sociable, the broader the debate can be – as everyone will want to contribute. However, you are also in more danger of falling into the ‘group think’ trap. Less sociable organisations will find it easy to set up a project team, but difficult to engage the entire organisation.

Another dimension on which cultures vary is what Goffee and Jones describe as ‘solidarity’ – the degree to which individuals agree to particular goals and ways of working. An organisation with a high level of solidarity works like an effective machine – where things are done using particular operating procedures. In such an environment, creating strategy will be welcomed if it is an accepted way of operating (think of a high-tech business that is continually re-designing its strategy) – but rejected if it is seen as a threat to or deviation from standard ways of operating (imagine trying to get a bunch of senior doctors to engage in a strategy process challenging the way they run their hospital department).

You probably understand intuitively that any process will be easier to operate if it fits the existing culture – but make sure that you also give it some conscious thought and debate.

WHAT YOU NEED TO READ

- Nilofer Merchant's The New How provides a guide to collaborative strategy-making. More information is at http://the-new-how.com.

- Chapter 18 of Ralph Stacey's Strategic Management and Organisational Dynamics, FT Prentice Hall, 2002, is a provocative challenge to orthodox management thinking and includes helpful suggestions for leaders.

- Ron Heifetz's classic Leadership Without Easy Answers, Harvard University Press, 1998, or his article ‘The Work of Leadership’ (written with Don Laurie, Harvard Business Review, Jan-Feb 1997) provide thoughts on leading strategy development.

- Ideas on creating the conditions for good group work can be found in Lynda Gratton's Hot Spots: Why Some Companies Buzz with Energy and Some Don't, FT Prentice Hall, 2007, or Dorothy Leonard and Walter Swap's When Sparks Fly, Harvard Business Press, 1999, or on Google Books.

- Teresa Amabile's Harvard Business Review article How to Kill Creativity is a handy summary of her many years of researching creative groups.

- The Art of Action, Nicholas Brealey Publishing, 2011, by Stephen Bungay provides more ideas on the links between strategy-making and implementation.

- Rob Goffee and Gareth Jones’ The Character of a Corporation, Profile Books, 2003, provides a useful introduction to organisational cultures.

IF YOU ONLY REMEMBER ONE THING

Involve a larger group in developing strategy if you need more ideas or stronger implementation.

1 This chapter has been co-authored with Chris Nichols and Philippa Hardman.