—DOUG LARSON

“CAN I ANSWER ‘ALL OF THE ABOVE‘?” the young mother wearing yoga pants and a stylish purple barrette asked, her little daughter peeking out from behind her legs.

“Naw. That won’t really tell me much,” I replied, and tried again. “Even if you agree with all these statements, which is most important to you?”

She looked at the multiple-choice question displayed on my clipboard as we talked in the middle of east-end Toronto’s organic food mecca, the Big Carrot. With busy shoppers flowing past, we occasionally had to stand on our tiptoes to let them by.

“I guess it would have to be number one, then. I’m really concerned about toxic chemicals.”

I had come to the epicentre of sandal-wearing culture in my city on this busy Saturday afternoon, survey in hand, with one simple question: Why do you buy organic food? Over the course of a few hours, my co-worker Rachel Potter and I spoke with almost 250 people, and the results were clear.1 More than 60 percent of those we quizzed identified their concern with toxins in non-organic food as their main reason for shopping at the Big Carrot—a finding similar to those of other studies that have looked at this question.2

The Big Carrot itself is a testament to the increasing interest in organic food. Founded in 1983, “the Carrot,” as it’s affectionately known, was the first one-stop-shopping natural and organic food store in Toronto. It survived for a number of years in a cramped 185 square metres of space: a far cry from its current palatial digs in the sprawling “Carrot Common” complex, which includes sundry retail outlets such as a juice bar, a wholistic dispensary and an independent bookstore. On average, the store now services about 2,500 people every day and the cooperative that runs it has just opened a second retail location.

So let’s drill down to the main concern of Big Carrot shoppers. Sure, people want to avoid toxins. But is there any proof that organic food can deliver on this?

I’ll put my cards on the table. Though I’ve long been a consumer of organic food, I’d always assumed that empirical evidence of its worth was lacking. In that case, why did I buy it? you ask. Out of faith, I guess. A sort of nutritional Hail Mary pass, a hope that it was sort of, kind of better—if not for me, then for the planet.

Not everyone is so casual about this, however. Judging by the vehemence in his voice coming through the phone line, Chuck Benbrook has little time for such vague thinking. Organic food has hard science on its side, he tells me.

An agricultural economist and former research professor in Washington State University’s Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources (CSANR), Benbrook has had a long career in the agricultural sector. He worked for nearly twenty years in a variety of senior roles with the U.S. federal government and has published widely on pesticide use and residue levels in food, as well as on the relative nutritional merits of different types of produce. After a 2012 article that was played by the media as torpedoing the value of organic food (discussed further below), Benbrook dryly rebutted this assumption, noting that he was among a small group of people who had actually read the hundreds of food studies the article cited.3 No two ways about it: “There is absolutely no way to escape the conclusion, based on a mountain of data, that consumers who seek out organic food to reduce their own personal or family’s exposure to possibly risky pesticides are getting a significant return on their investment. They’re lowering their risk by approximately eighty-fold.”

Benbrook has focused on pesticides in food because of the evidence that much of a typical person’s pesticide exposure comes from the residue of agricultural chemicals on fresh fruits and vegetables. He is particularly concerned that certain highly vulnerable segments of the population—including children and pregnant women (especially during the three months before conception and the first trimester of pregnancy)—are being exposed on a daily basis to pesticide levels that have the potential to trigger developmental problems. His argument rests not only on the presence of pesticides in certain types of produce, but also on their toxicity.4 Benbrook’s research team undertook what he characterizes as an “extremely excessive” analysis of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s pesticide programme database, which encompasses 15,000 to 25,000 food samples a year, including an increasing number from organic food. They analyzed these figures back to 1993 and created the Dietary Risk Index (DRI), which takes into account the frequency of residues, average residue levels and toxicity of the pesticide in question.

For example, Benbrook and his team compared conventionally grown varieties of eleven tree-fruit crops with the same produce grown organically and found that there was, on average, an 84-fold difference. That is, the pesticide residues that typically appear in conventional tree-fruit crops in the U.S. food supply make that produce 84 times riskier (to cause harm as defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency) to consume than organic fruit. Benbrook has done the same sort of head-to-head comparison for many vegetables and concludes that the DRI difference is typically between 50-fold and 150-fold.

To boil this down further, Benbrook calculated that on an average day an American consumer of conventionally grown produce will be exposed to seventeen pesticide residues: a combined DRI value of 2.0. Now, if this consumer replaces twelve foods or ingredients in his diet with organic items, the number of residues will drop from seventeen to five, and his combined DRI value will drop by over two-thirds, to 0.62. This finding fits well with one of the key points of this book—that is, the first thing to do in order to get toxins out of your body is to avoid them in the first place.

One interesting phenomenon that has Benbrook increasingly concerned is the change in the relative contribution to consumers’ pesticide risk of domestically grown versus imported produce. “In 1996, when the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA) passed in the United States,” he noted in an interview with me, “by our calculations about 75 percent of the dietary risk from pesticides came from domestically grown fruits and vegetables and about 25 percent of the risk came from imported foods. Today, the ratio has flipped to 75 percent from imports and only 25 percent from domestically grown foods.” His conclusion is that though the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is using the 1996 law to reduce pesticide levels in U.S.-grown food—undeniably good news—this has no effect on how pesticides are used overseas. As a result, most of the exposure of American (and, we can assume, other) consumers to pesticides like malathion and chlorpyrifos comes during the winter months, when we rely on imported fresh produce. “If this trend continues, another five years down the road, we might have 90 percent of the risk to consumers from pesticides happening in three months, virtually all from imports,” Benbrook concluded grimly.

So, according to Benbrook’s evidence, the answer to my initial question is clear, and unfortunate: most North American consumers are being exposed, on a daily basis, to pesticide levels that can hurt them. And others share Benbrook’s view. More scientific evidence of this problem is accumulating by the day (see table 5). Exposure to many commonly used agricultural pesticides is linked to a variety of health problems, particularly in kids.

It turns out that the Big Carrot shoppers have reason for concern after all.

Table 6. Recent science points to negative health effects from pesticide exposure.

| Health Effects | Study Description | Year of Study |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Elevated levels of organochlorine (OC) pesticides years before cancer develops increase risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma later in life. | 2012 |

| Endocrine disruption | Thirty out of 37 widely used agricultural pesticides blocked or mimicked testosterone and other androgens. | 2011 |

| General developmental problems and cognitive deficits in infants and children | Prenatal exposure to chlorpyrifos is associated with decreased IQ and working memory scores. Increased levels of prenatal dialkylphosphates (DAPs) are associated with lower neurodevelopment scores at 12 months. Increased urinary dimethyl organophosphate (OP) pesticides are associated with increased odds of ADHD. |

2011, 20165 |

| Low birth weight, smaller brain | Higher levels of OP pesticides in umbilical cord plasma are associated with lower birth weight, shorter length and smaller head circumference. | 2011 |

| Asthma and poor respiratory health | Any exposure to pesticides is associated with an increased risk of asthma, while living in a region heavily treated with pesticides presents the highest risk. | 2011 |

| Increased risk of obesity and diabetes | Low-dose pesticide exposure predicts incidents of type 2 diabetes and future adiposity, dyslipidemia and insulin resistance. | 2010, 2011 |

| Infertility | Increased concentration of DDT in maternal milk is associated with an increased risk of infertility. | 2009 |

If pesticide residues in organic produce are significantly lower than in conventional produce, the next question to answer (given the vagaries and variability of the human metabolism) is whether the transition to organic food will result in measurably lower pesticide levels in the body. Like Ray and Jessa’s experiment with cosmetics in chapter 1, does the notion of “detox by avoidance” work for pesticides in food as well?

Of the surprisingly few studies that have explored this area, the most convincing is that of Alex Lu, a professor in the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston.6 I sat with Dr. Lu in his sunny office in the beautifully restored art deco Landmark Center as he gave me a short history of pesticides. “Every thirty years or so we start using a different kind of pesticide,” he said. “There are a couple of reasons for this: one is because of resistance—the more you use a pesticide, the more tolerant of it the insects become. The other reason is that negative effects on human health or the environment start to surface.” Qualitatively speaking, Lu continued, our grandparents were exposed to different pesticides than we are today. Theirs was the generation that got bombarded by hazardous organochlorines—the family of compounds that includes DDT. “After the banning of DDT we started using organophosphate pesticides,” Lu said. “And around 2000, the U.S. started taking action to reduce organophosphates because evidence of health effects began to surface. History repeating itself.”

Though the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency had dramatically reduced most indoor uses of organophosphate pesticides by the early 2000s, the use of chemicals like malathion and chlorpyrifos on food crops was still allowed. Lu decided to investigate the effect of this practice on the human body with a simple but elegant experiment. “At the time nobody knew whether eating organic produce would have any beneficial effects, specifically for pesticide exposures. So we designed a crossover study with a group of kids lasting fifteen days. For the middle five days, they ate nothing but organic produce, and they ate their regular conventional food before and after the organic feeding days.” After completion of the study, Lu and his colleagues found that not only did the organic food they provided reduce the kids’ pesticide exposure, it largely eliminated the residues of malathion and chlorpyrifos in their bodies. The study demonstrated that an organic diet provides almost immediate protection against exposure to organophosphate pesticides that are commonly used in agriculture. It also showed that children are most likely exposed to these particular chemicals exclusively through their diet.

Interestingly, when Lu tested the same group of kids for another class of pesticides—pyrethroids—he found no similar reduction in levels as a result of eating organic food.7 Pyrethroids are synthetic chemicals similar to those found in chrysanthemums. Because of their effectiveness in eating away at the hard external skeleton of various bugs, they are now the most commonly used pesticides in the average home. Though the levels of pyrethroid pesticides in the urine of Lu’s test subjects didn’t diminish as a result of eating organic food, kids whose parents reported using pesticides at home (both in the house and in the garden) did have significantly higher pyrethroid levels. From this Lu concluded that residential pesticide use represents the most important risk factor for children’s exposure to pyrethroid insecticides.

Lu is also a pioneer with another family of pesticides that have—infamously—started to replace some organophosphates: neonicotinoids.8 Synthetic chemicals similar to nicotine, neonicotinoids are “systemic insecticides”: rather than sitting on the surface of the crops, they are actually slurped up by a plant through its root system. As Lu explained, Monsanto has teamed up with Bayer AG to coat their GMO corn seed with neonicotinoids. The claim is that, for the farmer, it will be one-stop shopping: you buy GMO corn pre-treated with insecticide and you don’t even have to spray. You just put down the seed and it will grow. The downside is that in the past when farmers sprayed with pesticides, consumers hoped that the residue on, for example, the surface of a tomato would dissipate over time because of sunlight, rainfall and so on. But with this new technology, Lu pointed out, there’s no way that you can remove the chemical prior to eating it.

Luckily for tomato eaters (and eaters of any other conventionally farmed fruits and veggies), there is currently no evidence that neonicotinoids are hazardous to human health.9 A good thing, given that one chemical from this family, imidacloprid, is the most commonly used pesticide in the world today.1011 It’s not so lucky for one group of insects, though: the bees. There is now considerable evidence that imidacloprid causes “colony collapse disorder,” or CCD—the mysterious global trend whereby bees up and desert their hives, never to be seen again. Given that bee pollination is involved in foods that comprise one-third of the U.S. diet and that commercial pollination is valued at about US$217 billion a year globally, this is a bit of a problem, to say the least.12 There are many competing hypotheses being put forward to account for CCD, which has now manifested itself in many places around the world. Some have theorized that colony collapse disorder may result from mite and virus infestations, bee malnutrition or even cellphone radiation. Alex Lu, however, provides convincing evidence that very small doses of imidacloprid can produce the CCD effect. In his carefully constructed experiment, fifteen of sixteen imidacloprid-treated hives were abandoned in four different apiaries twenty-three weeks after imidacloprid dosing. The survival of the “control” hives—those not treated with insecticide and managed alongside the treated hives—buttresses this conclusion.

In a serious bummer for them, honeybees don’t have the option of relying on organic food sources. They’re stuck buzzing around crops that, it is now fairly clear, are slowly poisoning them to death. Luckily for them, governments started to step in to protect the bees (or at least their economic value). In late April 2013, the European Commission passed a proposal to restrict the use of three types of neonicotinoids (including imidacloprid), effective December 2013 for a period of two years. The Commission took action in response to what it identified as “high acute risks” for bees when exposed to these pesticides.13 As of May 2018, the commission voted to “completely ban…outdoor uses” of these neonicotinoids, again citing their pernicious effect on bee populations.14 The U. S. Department of Agriculture initially rejected the EC’s claim that pesticides played an important role in colony collapse disorder, but eventually called for further investigation of the problem.15 As of December 2017, the EPA had scheduled a review and risk assessment of five neonicotinoid pesticides.16 In Canada, meanwhile, the CBC reported in December 2017 that the federal government had proposed “tighter restrictions” on neonicotinoids but stopped short of “an all-out ban.”17 Sub-national governments, however, have acted more assertively. Ontario has regulated a reduction in neonicotinoid use18 and Montreal and Vancouver have both banned neonicotinoids within city limits.19 Given the evidence of sky-high levels of neonicotinoids in honey right around the world—a fact that spells serious trouble for bees everywhere—this regulatory scrutiny is long overdue.20

Firestorm. That’s the word I’d use to describe the reaction to what became known as the “Stanford study” (reflecting the study’s institutional origin).21 The title — “Are Organic Foods Safer or Healthier Than Conventional Alternatives?”—tells you everything you need to know about the question it posed. And the screaming headlines that ensued—”Organic Food Isn’t Healthier and No Safer,” “Little Evidence of Health Benefits from Organic Food” and “It’s Official: Organic Food Is a Waste of Cash”—were the organic industry’s worst nightmare.

When I asked him for his reaction to the furor, Matt Holmes, who was then the executive director of the Canada Organic Trade Association (COTA), let out an exasperated sigh. Holmes is generally optimistic. After he started at COTA, Canada implemented the first-ever national standard and labelling system for organic products and signed major agreements with the E.U. and the U.S. to increase exports of Canadian organic food. Still, he admitted to some frustration. “I don’t think there’s an evil conspiracy against organic,” Holmes told me as we shared a drink overlooking Baltimore harbour’s historic warships. (We were both in town to attend Natural Products Expo East—one of the biggest organic industry conventions and trade shows of the year.) “I just think there’s a human tendency to assume organic should be a solution to everything, and it’s not. It can’t be. But the media, in particular, love to pull the ‘gotcha’ routine.”

Holmes told me about a recent incident involving a TV story about pesticide residues on organic apples. No matter how many times Holmes tried to explain that pesticides are ubiquitous (and therefore it’s no surprise that even organic apples have a bit on their skin), the journalist was determined to run with an “exposé” angle: “Revealed: Pesticides Found in Organic Produce!” “The levels they found were similar to those in unborn children and Arctic sea ice,” Holmes said. “The reality of today’s world is that this stuff is absolutely everywhere. Organic doesn’t promise to be completely pesticide-free—it can’t escape the random pesticides that are floating around. It promises to be an alternative system that doesn’t contribute to the problem.”

Holmes pointed out that the Stanford study set up a straw man that was further torqued through the extensive media coverage: that organic food is primarily desirable because of the claim that it has a higher nutrient content than conventional food. “It ignored or downplayed the other benefits of organic production. I like to describe organic agriculture as the hundred-year diet. It’s a system of agriculture that perpetuates itself, that creates a healthy ecosystem that will in turn continue to support plants in the long term, so you’re not in this deathly cycle of creating short-term nutrients—which then can contribute to pest infestations that need to be counteracted by immediate and short-term chemical pesticides, which then kill the life in the soil, which then requires another synthetic input. Holmes underlined that, despite the media hype, buried in the Stanford study are tepid admissions of the worth of organic food: a finding that organic produce has a 30 percent lower risk of containing pesticides than does conventional produce (a number that Chuck Benbrook believes is closer to 90 percent22) and another finding that conventional meats have a 33 percent higher risk of contamination with bacteria resistant to antibiotics than do organic meats (a figure that Benbrook calculates as being far too low).

Even if you accept the Stanford study’s contention that evidence for the nutritional superiority of organic food is lacking (which, by the way, flies in the face of other, more compelling studies that have concluded that organic foods are more nutrient-rich23 24), it strongly reinforces the argument that organic food is better for the consumer when it comes to levels of pesticides and disease-causing bacteria. This from a study that was widely trumpeted by the media as being a disaster for the organics industry.25

“In Organic We Trust” read the placards of the crowd milling outside the front doors of the Baltimore Convention Center.

As I pushed through the picketers to get inside, someone thrust a small envelope into my hand. It was a package of tea, a determined Uncle Sam staring out at me from one side and the Organic Tea Party’s “platform” emblazoned on the other: “The Organic Tea Party is a nonpartisan celebration of people, planet and pure tea. Our aim is a healthy and happy planet where our food chain and tea farmers are free from pesticides, chemically-enhanced fertilizers and genetically modified organisms (GMOs)…Declare Your inTEApendence and Vote Organic!” In the 2012 U.S. presidential election season, this fun gimmick by the Numi tea company was the first of many indicators at Natural Products Expo East that the organic industry was feeling pretty pleased with itself. One might say even cocky.

During the conference in Charm City, I heard a keynote speech by Kathleen Merrigan, who was deputy secretary of the U.S. Department of Agriculture at that time; more than ten years earlier she had been one of the lead authors of the USDA’s organic labelling rules. In her upbeat remarks, Merrigan at one point said that the “USDA as a department is really owning organic,” which caused the assembled organic industry leaders to look at each other and murmur in delight—no doubt thinking that only a few years earlier, such a powerful validation from a government leader would have been utterly unthinkable. Another surprise, a made-in-Canada one this time, occurred at the gala dinner of the Organic Trade Association (OTA; affiliated with Matt Holmes’s COTA), the organic industry’s lobbying arm. In a sea of (charming) Americans, I sat at a table with a number of fellow Canucks, including a guy from Export Development Canada (EDC). EDC is the Canadian federal government’s export credit agency, and it’s a big deal, providing financing to Canadian exporters and investors in more than two hundred markets worldwide. In 2009 alone, EDC facilitated over C$82 billion in investment, export and domestic support. Every few years EDC picks a new batch of strategic areas on which to focus its largesse—areas the agency believes will prove winners on the international stage. And guess what? Organic agriculture is now one of those areas. As of 2017, the Canadian organic sector generates annual sales of $5.4 billion and the EDC frequently provides financing to organics-focused companies as part of a larger effort to cultivate “new markets for Canada’s agri-food companies.”26, 27

Another organic expert I chatted with in Baltimore (over a delicious cup of organic tea) was Katherine DiMatteo. The energetic, grey-haired DiMatteo was for sixteen years the executive director of the OTA, leading the industry through the critical years that culminated in implementation of the first U.S. National Organic Program (NOP) standards in 2002. DiMatteo still remembers the excitement of that time. “It was a very unified effort. It was initiated by environmental and consumer activist groups, then the farmer organizations came on, and the Organic Trade Association—which was little bitty at the time—with our small group of processors and retailers also joined in. It was multi-stakeholder and multi-interest, but we knew this was the moment to get a breakthrough at the national level.” The results of the new standard have been truly impressive. In 1990, the year that DiMatteo joined the “little bitty” OTA, U.S. sales of organic food were US$1 billion annually. In 2002, the year the NOP standards were implemented, that number had grown to US$8.6 billion. In 2017, U.S. sales stood at $49.4 billion.28

Despite this astounding growth (which shows no signs of abating anytime soon) and the generally positive mood in the Baltimore Convention Center, DiMatteo confessed to fretting about some storm clouds on the horizon. I asked her about a recent article in the New York Times that detailed infighting between organic advocates. The dispute has centred on the actions of the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) in approving some food additives—like carrageenan, a seaweed-derived thickener—as being okay to include in certified organic products.29 “Absolutely benign and consistent with organic principles,” say the majority of those on the NOSB. “A sellout to big business and a betrayal,” retort some organic purists like the Cornucopia Institute, publisher of the provocative report The Organic Watergate—Connecting the Dots: Corporate Influence at the USDA’s National Organic Program.30 Looking at me over the top of her glasses as she nursed her steaming tea, DiMatteo observed that the organic industry is often its own worst enemy. “Certified organic is a rigorous adherence to now nationally required standards,” she explained. “It’s costly in terms of certification, inspection, paperwork and all these other things, and the regulations constantly get tightened. Our movement wants continuous improvement, quickly—and we’re not patient.”

DiMatteo is concerned not only that this “constant tightening” of the NOP standards dissuades potential new entrants to the organic market, but also that the constant push to expand the meaning of “organic” is making the concept too unwieldy and undeliverable. “Other agendas are beginning to be played out in the organic regulations,” she told me. “Like allergies. Our standards aren’t about allergenicity. We’re supposed to be about environmental protection and biodiversity. Now all of a sudden we have to talk about things like ‘Is it an allergen?’ The organizations that have the energy to push and work on these things are now using organic as a platform for moving towards an agenda that is making it very difficult for both the people already in organic to stay in and new people to get in.” DiMatteo wonders whether some organic advocates are really trying to drive processed foods out of the organic certification system entirely. In her view—and I have to say I agree with her—this would be entirely counterproductive. “At least here in the U.S., we still buy an awful lot of processed food. That culture isn’t going to change,” she said. “The way to mainstream consumers is not by telling them you have to only eat fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains.”

It falls to DiMatteo’s successors at the OTA to work through these complicated issues. Clearly, they have their plate full. The way Laura Batcha, the OTA’s current CEO, sees it, the organic industry is at an exciting but vulnerable moment. “A lot of the conventional agriculture industry has been annoyed hearing the USDA endorse and recognize organic across the whole agency. Even though the institutions and the dollars and a lot of the change haven’t happened yet, they just don’t like the talk of it,” she told me as we tried to find a quiet corner on the noisy convention floor. “There’s been a much more coordinated pushback on us from the conventional industry, and we’re at a vulnerable spot in our growth because we’re no longer under the radar.”

“So you’re not niche anymore,” I offered.

“We’re not niche. We’re post-niche! And it’s a vulnerable place to be because we’re between. We’re increasingly mainstream but we’re still operating from a minority position.”

Whether you’re Apple or a small organic food store, the pressures and complications that emerge from expanding your business are often difficult to manage. Given the organic sector’s very rapid emergence into the consumer mainstream, it’s perhaps not surprising that there are some growing pains. Many organic companies are experiencing year-over-year double-digit increases in their revenue. Some of their stories are quite spectacular.

Here’s an example. At its founding in Vancouver in 1985, Nature’s Path sold just one product: Manna Bread, a dense and nutritious sprouted-grain concoction that quickly became a health food store fixture. Still privately held and run by Arran and Ratana Stephens and their children, Nature’s Path is now the largest organic cereal company in North America, with annual sales in excess of C$200 million and distribution in 42 countries.31 As I munched my way through the overflowing basket of samples sent to me by Maria Emmer-Aanes, at the time the company’s director of marketing and communications, I didn’t find this terribly surprising. Their cereal is delicious: I now keep a pack of Love Crunch Apple Crumble granola on my desk. Emmer-Aanes told me that Nature’s Path has bought nearly three thousand acres of farmland in Saskatchewan to supply many of their whole-grain needs and continues to invest in social causes like the Prop 37 battle (described below). “The company is fiercely independent,” she says. “We feel that it’s socially responsible to make sure that everyone—no matter your economic status—has access to chemical-free food. This is a company that decides what its margins are going to be, decides what it’s going to put back into the world and isn’t afraid to make unconventional financial decisions. The strategy has paid off. When you give, it comes back to you!”

Another story of success is that of possibly the most ebullient champion of all things organic: Gary Hirshberg, chairman and former “CE-Yo” of Stonyfield, an organic yogurt maker in Londonderry, New Hampshire. A tagline on Stonyfield’s website reads “Environmentalists turned yogurt makers”—a succinct summary of the company’s DNA. Hirshberg joined what was a tiny business in 1983 hoping to turn the cottage industry into a profit centre that would fund a local farming school dedicated to teaching sustainable agricultural practices. That year, the first fifty-gallon batch of yogurt was made and annual sales totalled US$56,000.32 The demand for their yogurt soon outpaced Stonyfield’s nineteen cows’ ability to supply the milk, and the company began buying product from local dairy farmers. By 1988, the company had expanded so much that they were able to build a large industrial facility in Londonderry with sophisticated dairy-processing equipment that could handle the increasing demand.33 As of 2012, Stonyfield Farm had production companies in the United States and Canada and ventures in France and Ireland—and was valued at US$400 million.34 Choosing a different growth strategy than Nature’s Path, Stonyfield partnered with food product multinational Danone Group in 2001, and in 2014 Danone purchased a controlling stake in the company.35 The transaction helped to propel the company to its current position as the largest organic yogurt producer in the world and the third-largest yogurt brand in the United States.36 In July 2017, however, Danone sold Stonyfield to Lactalis for $875 million, largely because of anti-trust pressure from the U.S. Department of Justice.37

Stonyfield’s affiliation with a larger global food company is typical of a wider consolidation trend in the organic sector. Multinational food companies have got into the business of not going but getting organic: acquiring successful smaller organic companies. Those delicious, all-natural Naked fruit juices and smoothies? Since 2006 these beverages have been brought to you by PepsiCo. General Mills, the makers of such staples as Betty Crocker, Lucky Charms and Pillsbury, actually entered the organic business pretty early on, with their 1999 acquisition of Small Planet Foods, adding the likes of Muir Glen organic canned tomatoes, juices and sauces to their already humongous stock list. And what better example of granola going corporate than the buyout of Kashi by the Kellogg Company in 2000?38

For Hirshberg, a wiry and intense guy who admits to preferring peppermint tea because no one could handle him on caffeine, there’s no time to waste. “We’ve got to become part of the mainstream. It’s got to happen. We’re on a chemical time bomb as a species.” Hirshberg’s perspective is simple: “Everywhere food is sold there should be organic. Walmart, airlines, airports. I’ve worked very closely with Walmart—I think I was the first mainstream organic company to be in Walmart. I have gone down and given lectures at their infamous Saturday morning town hall meetings. I’ve met with heads of Walmart in other countries. I think a lot of activists are very troubled by places like Walmart, but I’ll tell you, the nail in the coffin of synthetic growth hormone was driven by Walmart.” In Hirshberg’s view it was Walmart’s refusal to buy products containing synthetic growth hormone that spurred other companies, such as Danone and Yoplait, to change (food sales account for over half of Walmart’s total revenue, totalling $200 billion in 2016).39 “A big player like that can move mountains.”

Given that Bruce and I have the primary objective of reducing levels of synthetic chemicals in people’s bodies—as many people as possible as quickly as possible—I tend to agree with Hirshberg’s logic. After chatting with him, I actually phoned up Walmart to find out more about their sales of organic products. Just by dint of its enormous size (accounting for about 26 percent of all groceries sold in the U.S. in 2017), Walmart moves more organic food than any other retailer. I spoke with Ron McCormick, then Senior Director of Sustainable Agriculture for Walmart U.S. He told me that after a very public commitment in 2006 to double sales of organics, the retailer has now zeroed in on those areas where organic sales continue to grow. “If you look at where organic is really selling, you have big dollars in dairy and big dollars in organic baby food and big dollars in fresh produce.”

I was surprised when McCormick told me that, these days, Walmart sees more interest in local food than in organic. The retailer committed to increasing local’s share of its total produce sales to 9 percent by 2015—and in 2018 local produce represented 10 percent of the total sold in U.S. stores.40 McCormick foresees further great opportunities to increase the amount of local production across the country, and in this sense Walmart is simply responding to what is clearly a pervasive trend. “Locavore” was named 2007 Word of the Year by the Oxford American Dictionary, and I now stumble upon farmers’ markets selling local produce in virtually every city I visit. Locally sourced ingredients are now de rigueur on restaurant menus everywhere, and the “100-Mile Diet” is ensconced in the vernacular.

This rise in the prominence of local food clearly irks some organic advocates. The Canada Organic Trade Association, for instance, has published a hard-hitting postcard enumerating the advantages of organic food: it’s subject to a rigorous, government-regulated labelling and certification system; it’s guaranteed to have been produced without the addition of pesticides, synthetic fertilizers or growth hormones or antibiotics; it’s made without artificial preservatives, colours, flavours or chemical additives; and animals providing organic meat are raised in accordance with humane standards. Meanwhile, COTA gives “local” a failing grade across the board. Unlike the term “organic” on food, which now in many other parts of the world is subject to government oversight, the term “local” can be slapped on any food with wild abandon. What does it mean? How local is local? Who checks up on whether a given item was really produced locally?

One potential comparative advantage that local has over organic is its generally smaller carbon footprint. Logically, if a product comes from the local vicinity, transporting it to your table should create fewer greenhouse-gas pollutants than the amount created when a similar item is brought in from abroad. This raises the question of whether organic food is simply trading one type of pollution for another: carcinogens for global-warming gases. Andre Leu, president of the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM until 2017), has thought a lot about this issue, not only because this Bonn, Germany–based global umbrella body for the organic sector represents over 1,000 affiliates in 120 countries,41 but also because he’s an organic tropical fruit farmer in a remote area of Queensland, Australia. Shipping organic produce to buyers halfway around the world is what he does for a living. I met Leu at Natural Products Expo East in Baltimore.

“When it comes to carbon dioxide, there are really two issues,” Leu began. “In terms of the amount put into the atmosphere during the life cycle of a crop, the transport from the farm to the market is very minimal compared to other inputs. For instance, there’s some wonderful work done in New Zealand: it’s actually better for the environment for England to air-freight all its organic products from New Zealand every day as opposed to the way they’re producing it conventionally now, particularly in winter, when you have hothouses and heating.” Leu argues that the amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse-gas pollutants like nitrous oxide that are given off by chemical fertilizers, along with the amount of carbon dioxide used to actually produce the pesticides, means organic has a much lower carbon footprint than conventionally produced “local” food.

The other significant carbon advantage of organic, according to Leu, is the amount of carbon sequestered in the soil by organic agriculture. “The word ‘organic’ actually comes from the fact that we recycle organic matter in the soil through composting and the like,” Leu said. “As a primary practice, our focus has been building up soil organic matter—in other words, organic soil carbon. And now we have very good data showing that organic practices not only emit less carbon in the growing than conventional, but also, when we factor in the amount of carbon dioxide we can strip out of the atmosphere and sequester in the soil when we build up the organic soil matter, we are actually not just greenhouse-neutral. We mitigate more than we put out.” Leu became more animated as he described new data indicating that a more widespread adoption of organic agriculture could have a huge impact on the reduction of greenhouse-gas pollution. Leu claims that with organic we could remove up to 20 percent of all current global greenhouse-gas output. Call this “atmospheric detox.”

I can think of no one who shows more passion for food issues than Sarah Elton. Sarah is a friend, a prominent journalist and author of the bestselling Locavore: From Farmers’ Fields to Rooftop Gardens—How Canadians Are Changing the Way We Eat. She eschews packaged food, preferring instead to make all her family’s meals from scratch, and she worries aloud that she wasn’t able to can as many vegetables this past autumn as she usually does. I figured if anybody was prepared to eloquently and aggressively defend the moral superiority of local over organic it would be Sarah. Turns out I was completely wrong.

For starters, in terms of her personal buying habits for her husband and two young daughters, she regularly shops at the Big Carrot and is “one hundred percent behind organic. We definitely need to be pushing in that direction,” she told me emphatically. I told her about the COTA postcard and its criticisms of local food’s lack of rigour or definition, and she agreed with it totally. “I was just chopping my pear this morning and remembering the sign about low-spray pesticides at the Brickworks [a farmers’ market in downtown Toronto], where I bought it. What the heck does ‘low spray’ mean? Who decides what’s low and what’s high? What happens if you have pests one year? Are you going to tell me that you’ve gone high spray? I don’t think so. So I agree, local is not the be-all and end-all. It’s a piece of the sustainable food system.”

Elton defines her number one concern as “sustainable food,” by which she means food that’s good for people and good for the planet. “There’s no question that organic is better for the environment, because organic agriculture nurtures the soil. If you’re worried about carbon emissions, it sequesters more carbon than conventional agriculture. It doesn’t rely on toxic chemicals because it sees agriculture as ecology rather than a war against the earth. On the other hand, local food economies are so good on so many levels for rural and urban communities. So local plus organic equals sustainability: socially, culturally and environmentally.”

Even though she figures her own family eats 80 to 90 percent organic, Elton isn’t too fussed if, for the time being, local is stealing some of organic’s buzz. “I see local as a first step in the learning process and the first step towards building a more sustainable food system. Hopefully, by realizing we want our local farmers, soon we’ll be able to talk about why organic local is better than just local.”

With the exception of Alex Lu’s studies on pesticides and food, few efforts have been made to evaluate whether organic food results in lower levels of toxins in your body.42 So Bruce and I set out to see whether we could duplicate Lu’s then-decade-old work. The task at hand for our big experiment was a pretty strange one—we needed a bunch of kids to agree to eat lots of vegetables over the course of twelve days during their summer break, and they had to collect their pee each day. To find these kids, we did what any good twenty-first-century researcher does: we took to Facebook. Our call outlined the following: the word on the street is that an organic diet might be better for the environment and our bodies, and eating organic could mean reduced exposure to the harmful chemicals that are in conventional food—something we wanted to show with their help. After a few days of interviews, we found nine really great kids from five Toronto-area families who were excited to participate in our experiment. They included five girls and four boys, ages three to twelve. These families were all different in a lot of wonderful ways, but they had two important things in common: they didn’t at present eat any organic food and they were willing to spend twelve days of their summer holidays helping out with our experiment.

Here’s what the 12 days looked like for these nine kids:

Phase 1: Days 1–3

8 a.m. collection of urine sample each day, conventional diet

Phase 2: Days 4–8

8 a.m. collection of urine sample each day, organic diet only

Phase 3: Days 9–12

8 a.m. collection of urine sample each day, conventional diet

We were very lucky to have that wonderful grocery store, the Big Carrot, offer to donate all the organic food for the organic portion of the experiment. And I’m not just talking apples and oranges. I’m talking organic applesauce, organic zucchini bread and all that falls in between: olive oil, flour, canned tomatoes and—unanimously appreciated by our participants’ moms and dads—organic ice cream for those hot summer days. So the night before the organic phase of their experiment, whether by car, streetcar or bike, each of these five families made the trek to the Carrot on Danforth Avenue to pick up their supplies for the next five days.

By now I’ll bet a lot of you are wondering what happened with all that pee. The families kept each day’s samples in their freezers until the end of the experiment, at which point our intrepid research assistant, Rachel, collected the samples from each kid—all 108 jars. The urine samples were shipped off to a lab in California for testing and then we waited for the results. Several anxious months later, we received the results table with a daunting 1,800-plus pieces of data on urinary pesticide levels. It was quite a dramatic hour as we oh so carefully entered the lab results into a spreadsheet for our analysis, eager to see what they would demonstrate.

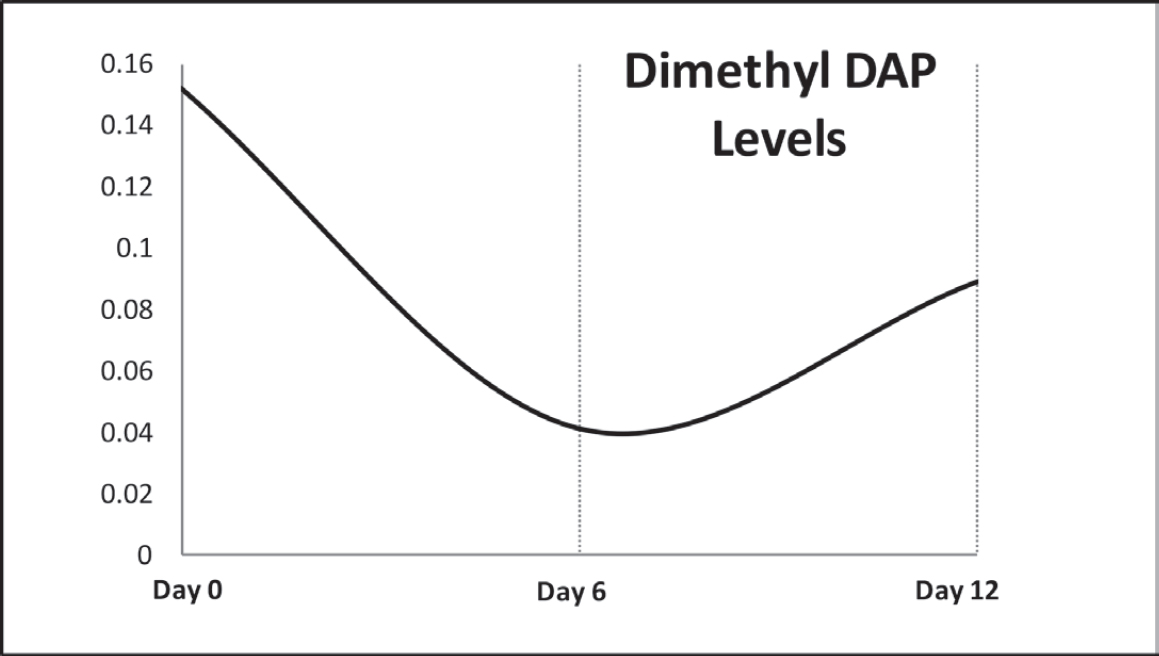

Our objective was to compare the organophosphate (OP) pesticide metabolite levels in the urine of the children. OP pesticides were chosen because of their widespread use, their reported presence as residues on foods frequently consumed by children and their acute toxicity.43 Check out figure 10 for a graph of the results (and the endnotes for an explanation of our calculations).

Figure 10. Average of dimethyl dialkylphosphate (DAP) levels for nine children over the three phases of the experiment (units are ng/L).

The graph, you’ll see, shows average concentrations, for all the children together, of dimethyl dialkylphosphate (DAP) metabolites (which are common to OP pesticides) over each of the three phases of the experiment (conventional, organic, conventional). Notice the significant drop in dimethyl DAP levels during phase 2 (the organic phase) and the increase again once the kids started eating conventional food in phase 3. In scientific parlance, the organic and conventional results are “significantly” different. What does this mean to everyone in general? Eating organic really can lower your pesticide levels! A particular comment stuck with me when we did our follow-up interviews. One mother told me that she was initially interested in the study because her father, following some health issues, had become an “organic/vegan freak” but that she didn’t really believe all the hype about organics and being chemical-free. As a single parent, she was also wary of organics’ cost (though the cost difference between organic and non-organic food is rapidly shrinking as the organic industry grows).44 “Now,” she said, half-laughing, half-sighing, “I’ve got some real numbers proving my dad is right.” She said she didn’t know what was more annoying: admitting that her father was right or that those chemicals were in her daughter at all.

I think we can all guess what she really believes.