1959 Cadillac outside Hotel Nacional

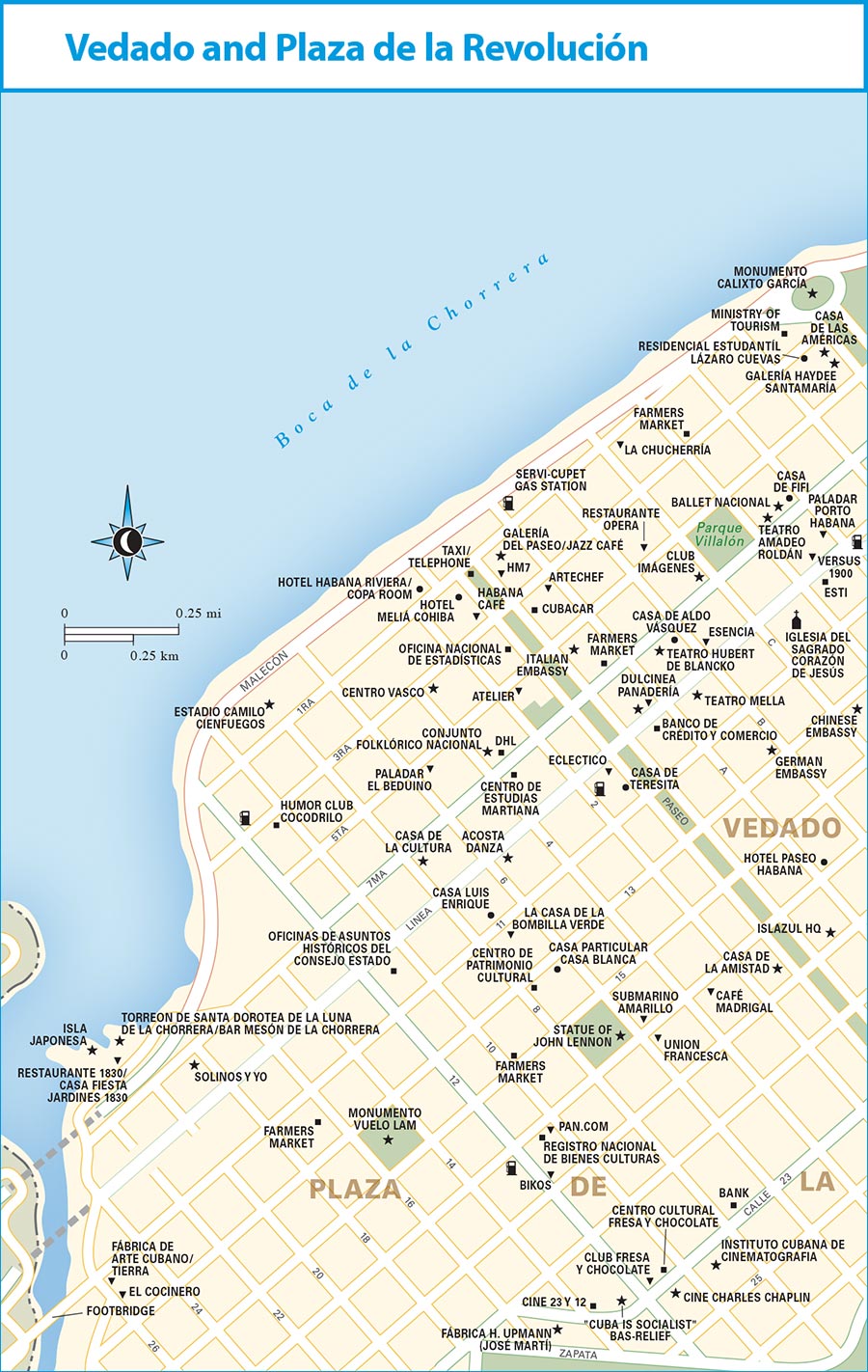

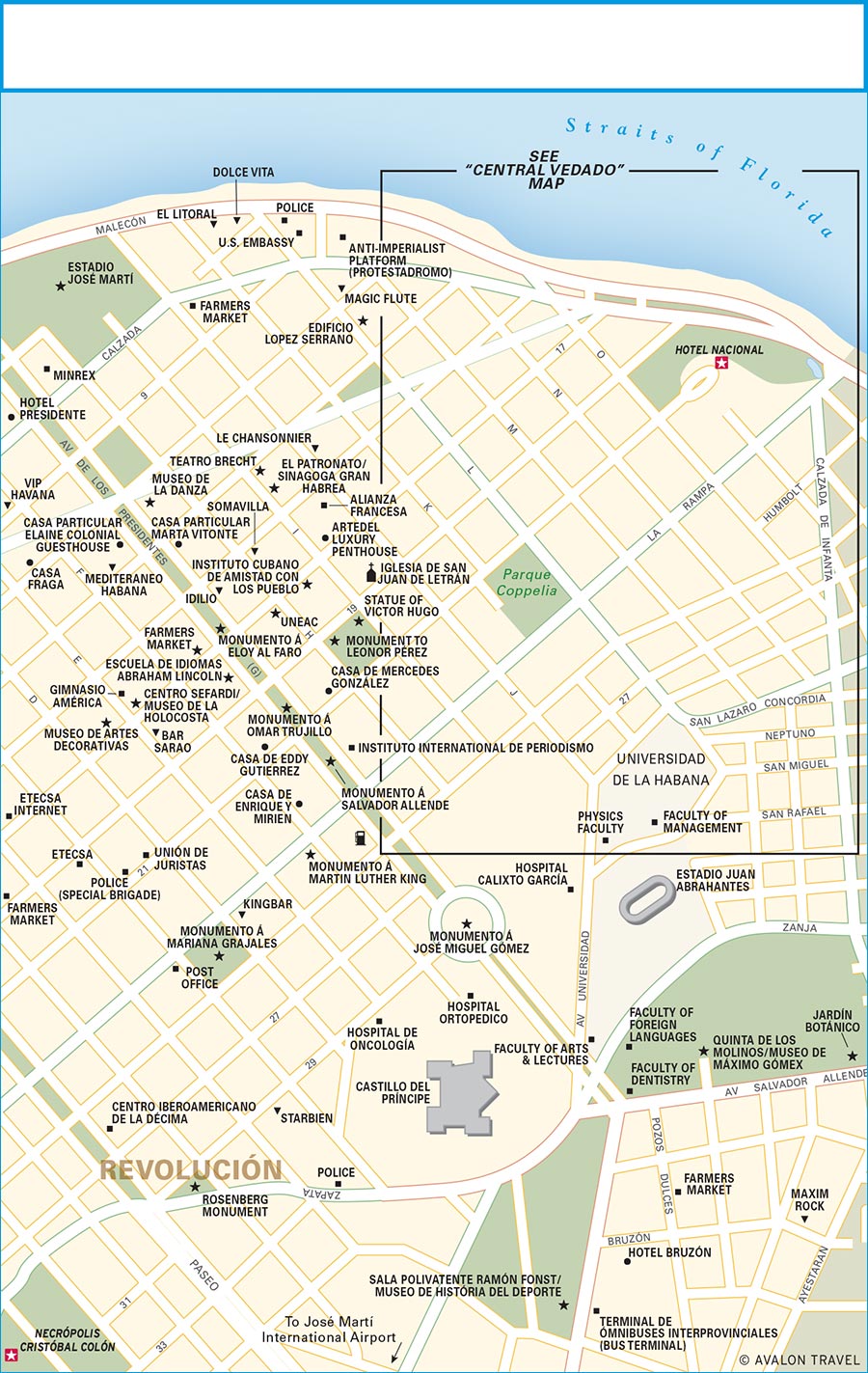

VEDADO AND PLAZA DE LA REVOLUCIÓN

PERFUMES, TOILETRIES, AND JEWELRY

DEPARTMENT STORES AND SHOPPING CENTERS

VEDADO AND PLAZA DE LA REVOLUCIÓN

VEDADO AND PLAZA DE LA REVOLUCIÓN

CIUDAD PANAMERICANO AND COJÍMAR

Plaza Vieja, Habana Vieja.

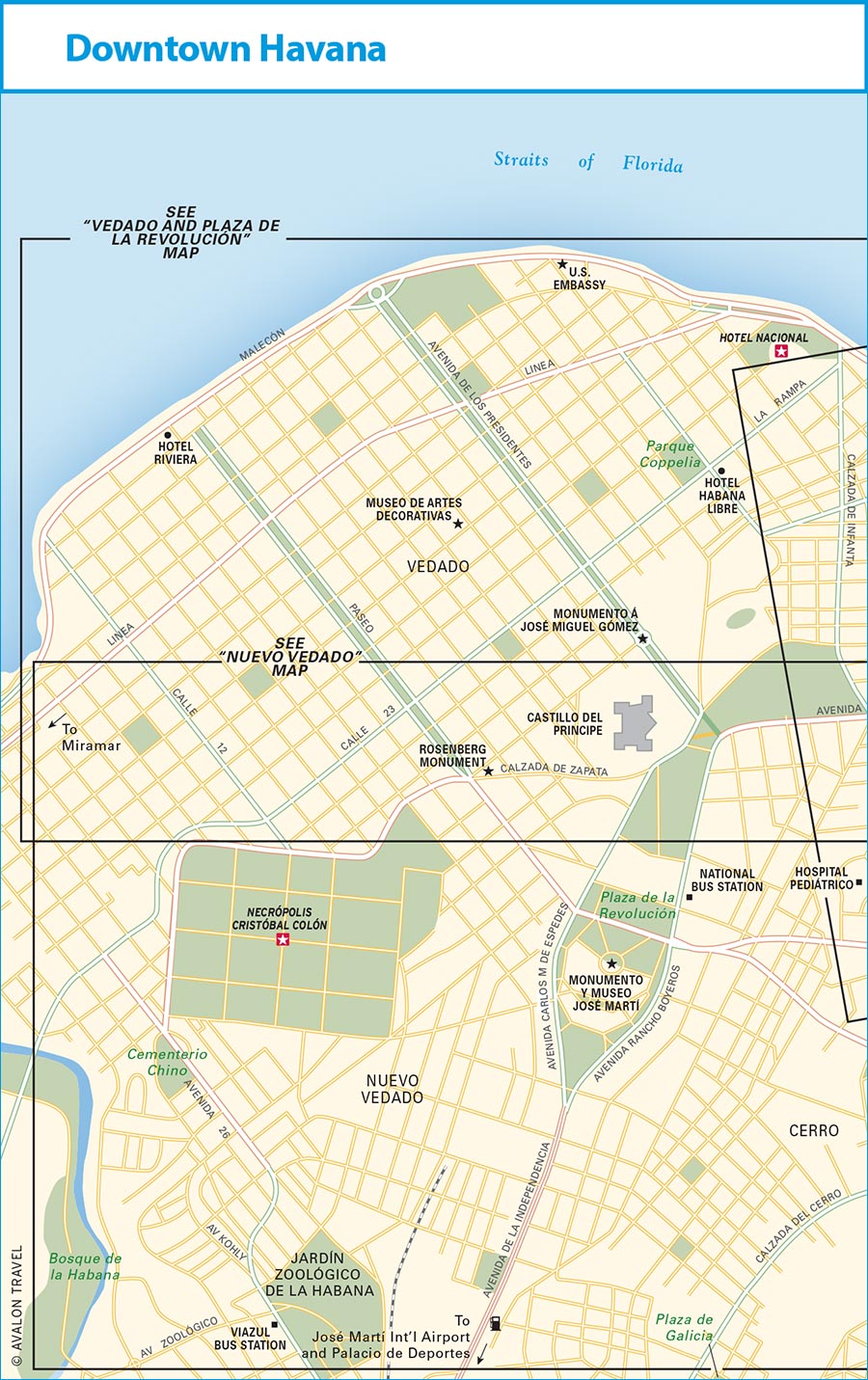

Havana is the political, cultural, and industrial heart of the nation.

It lies 150 kilometers (93 miles) due south of Florida on Cuba’s northwest coast. It is built on the west side of the sweeping Bahía de la Habana and extends west 12 kilometers to the Río Jaimanitas and south for an equal distance.

Countless writers have commented on the exhilarating sensation that engulfs visitors to this most beautiful and beguiling of Caribbean cities. Set foot one time in Havana and you can only succumb to its enigmatic allure. It is impossible to resist the city’s mysteries and contradictions.

Havana (pop. 2.2 million) has a flavor all its own, a merging of colonialism, capitalism, and Communism into one. One of the great historical cities of the New World, Havana is a far cry from the Caribbean backwaters that call themselves capitals elsewhere in the Antilles. Havana is a city, notes architect Jorge Rigau, “upholstered in columns, cushioned by colonnaded arcades.” The buildings come in a spectacular amalgam of styles—from the academic classicism of aristocratic homes, rococo residential exteriors, Moorish interiors, and art deco and art nouveau to stunning exemplars of 1950s moderne.

At the heart of the city is enchanting Habana Vieja (Old Havana), a living museum inhabited by 60,000 people and containing perhaps the finest collection of Spanish-colonial buildings in all the Americas. Baroque churches, convents, and castles that could have been transposed from Madrid or Cádiz still reign majestically over squares embraced by the former palaces of Cuba’s ruling gentry and cobbled streets still haunted by Ernest Hemingway’s ghost. Hemingway’s house, Finca Vigía, is one of dozens of museums dedicated to the memory of great men and women. And although older monuments of politically incorrect heroes were pulled down, they were replaced by dozens of monuments to those on the correct side of history.

The heart of Habana Vieja has been restored, and most of the important structures have been given facelifts, or better, by the City Historian’s office. Some have even metamorphosed into boutique hotels. Nor is there a shortage of 1950s-era modernist hotels steeped in Mafia associations. And hundreds of casas particulares provide an opportunity to live life alongside the habaneros themselves. As for food, Havana is in the midst of a gastro-revolution. A dynamic new breed of paladar (private restaurant) owner is now offering world-class cuisine in spectacular settings. Streets from Habana Vieja to Vedado resound with the sound of jackhammers. Pockets of gentrification—an inconceivable word for Cuba until now—are emerging as the rapprochement with the United States and the tourism boom it has fostered are translating into money, money, money and a surge of private investment in boutique bars, boutiques, and chic casas particulares billed as boutique “hotels.”

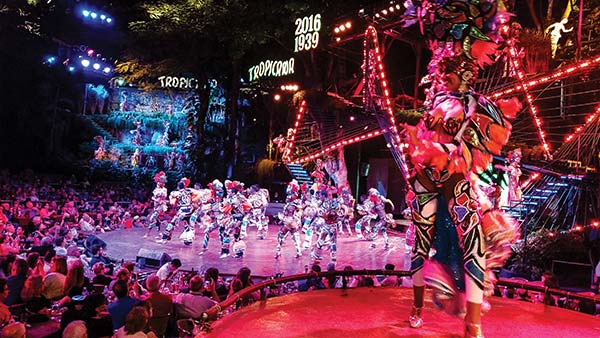

Nonetheless, it’s increasingly hard to find a vacant hotel room: Havana is jam-packed with yanqui visitors making the most of the heretofore forbidden fruit. A series finale of House of Lies, plus segments of Fast & Furious 8, have been filmed in Havana as Hollywood, too, has cottoned on. In 2017, U.S. cruise ships arrived, flooding the plazas with tour groups. The arts scene remains unrivaled in Latin America, with first-rate museums and galleries—not only formal galleries, but informal ones where contemporary artists produce unique works of amazing profundity and appeal. There are tremendous crafts markets and boutique stores. Afro-Caribbean music is everywhere, quite literally on the streets. Lovers of sizzling salsa have dozens of venues from which to choose. Havana even has a hot jazz scene. Classical music and ballet are world class. And neither Las Vegas nor Rio de Janeiro can compare with Havana for sexy cabarets, with top billing now, as back in the day, belonging to the Tropicana.

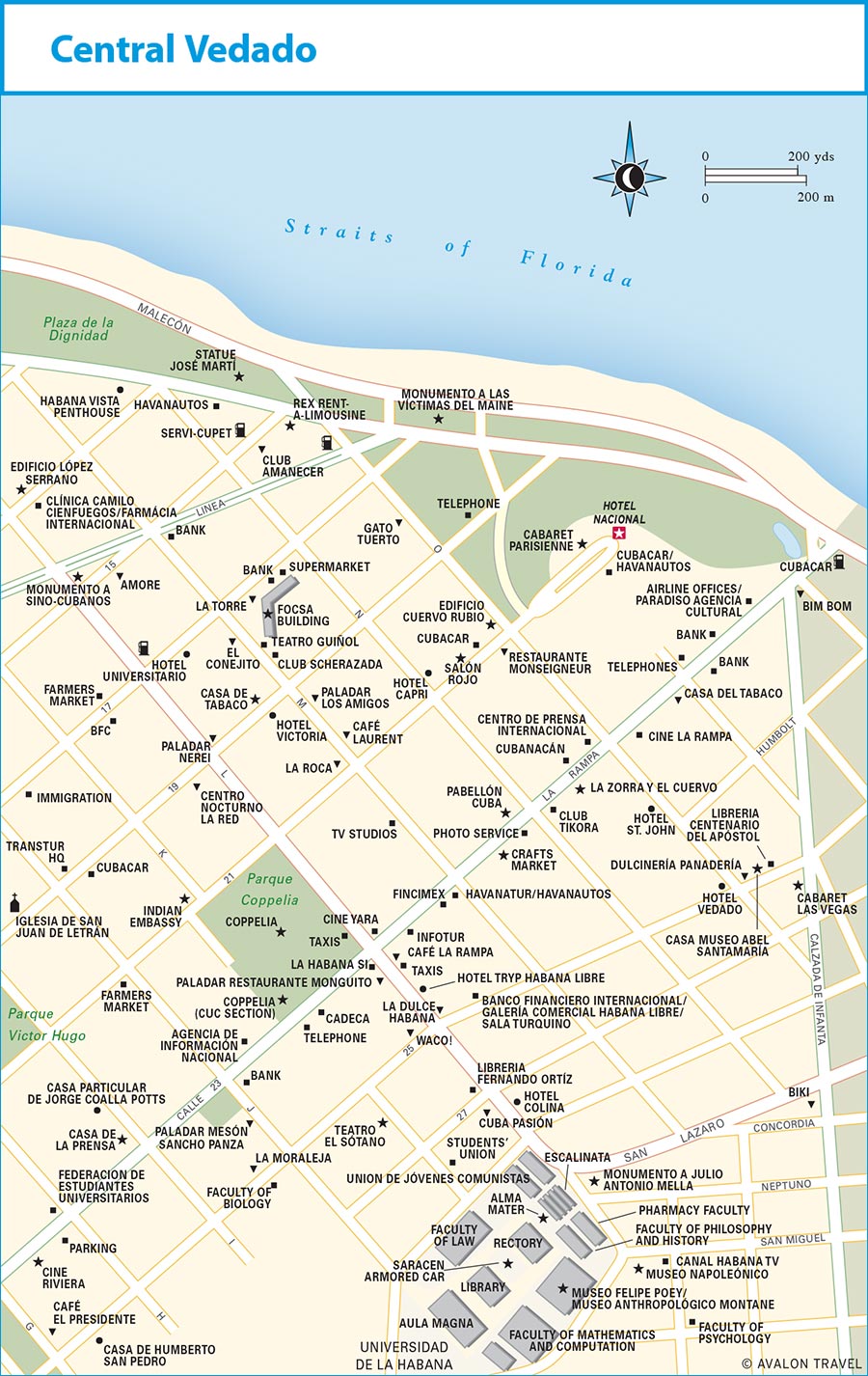

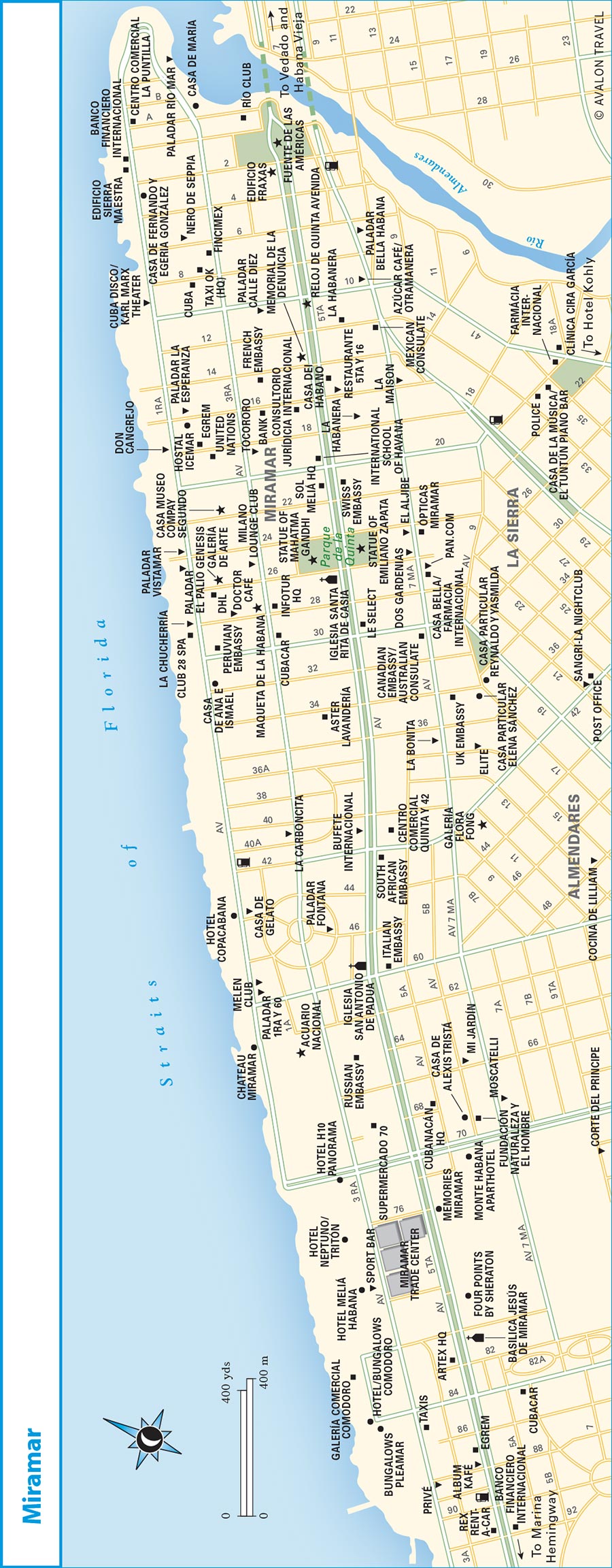

Havana is so large, and the sights to be seen so many, that one week is the bare minimum needed. Metropolitan Havana sprawls over 740 square kilometers (286 square miles) and incorporates 15 municipios (municipalities). Havana is a collection of neighborhoods, each with its own distinct character. Because the city is so spread out, it is best to explore Havana in sections, concentrating your time on the three main districts of touristic interest—Habana Vieja, Vedado, and Miramar—in that order.

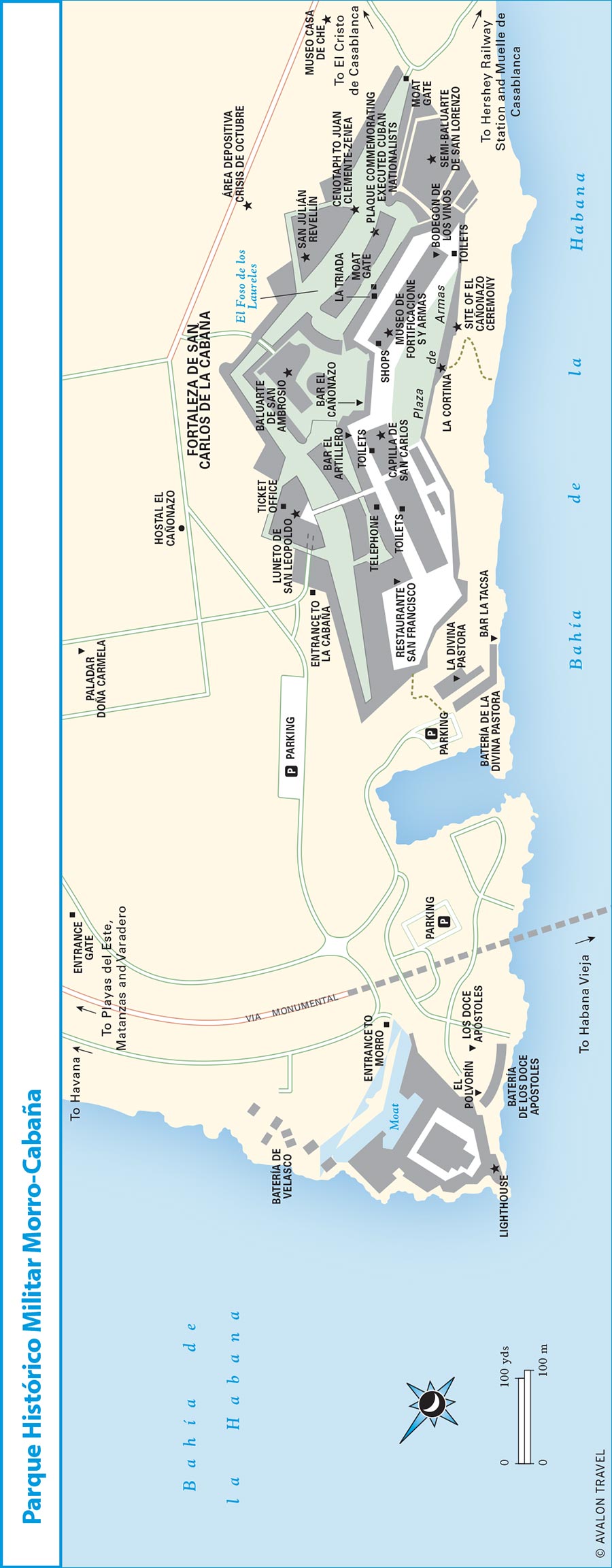

If you have only one or two days in Havana, book a get-your-bearings trip by HabanaBusTour or hop on an organized city tour offered by Havanatur or a similar agency. This will provide an overview of the major sights. Concentrate the balance of your time around Parque Central, Plaza de la Catedral, and Plaza de Armas. Your checklist of must-sees should include the Capitolio Nacional, Museo de la Revolución, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Catedral de la Habana, Museo de la Ciudad de la Habana, and Parque Histórico Militar Morro-Cabaña, featuring two restored castles attended by soldiers in period costume.

Habana Vieja, the original colonial city within the 17th-century city walls (now demolished), will require at least three days to fully explore. You can base yourself in one of the charming historic hotel conversions close to the main sights of interest.

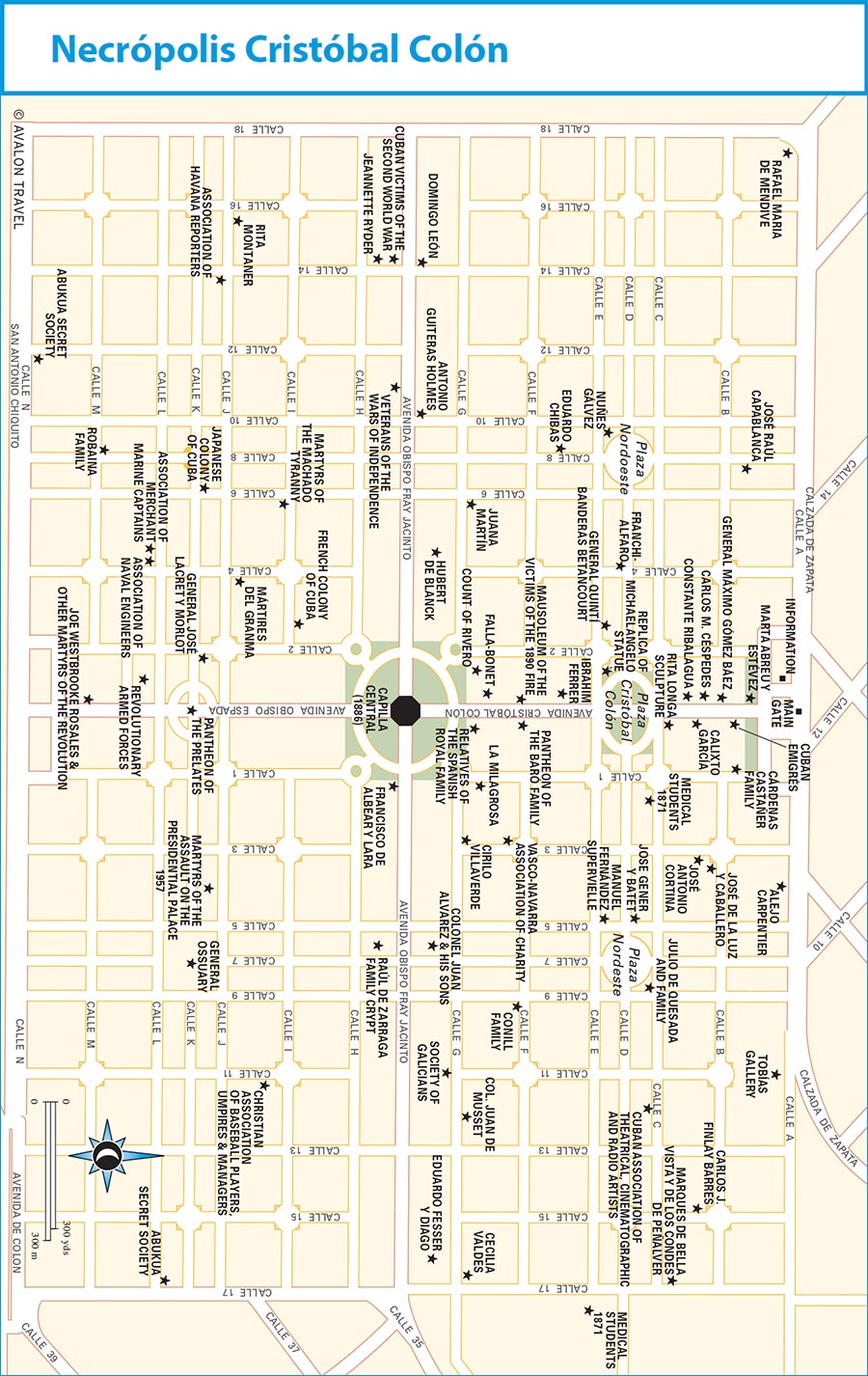

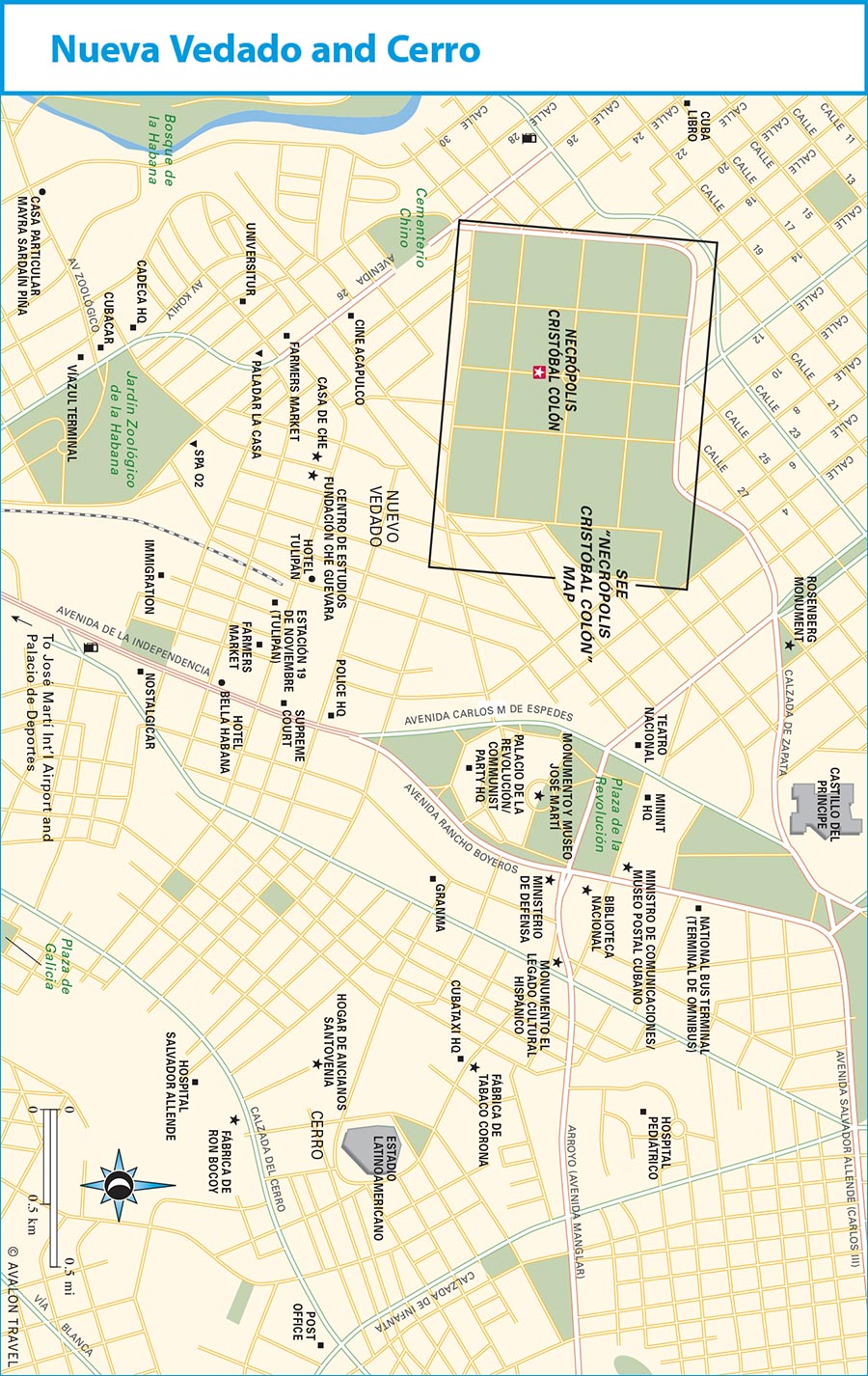

Centro Habana has many casas particulares and fine restaurants but few sites of interest, and its rubble-strewn, dimly lit streets aren’t the safest. Skip Centro for Vedado, the modern heart of the city that evolved in the early 20th century, with many ornate mansions in beaux-arts and art nouveau style. Its leafy streets make for great walking. Many of the city’s best casas particulares are here, as are most businesses, paladares, and nightclubs. The Hotel Nacional, Universidad de la Habana, Cementerio Colón, and Plaza de la Revolución are sights not to miss.

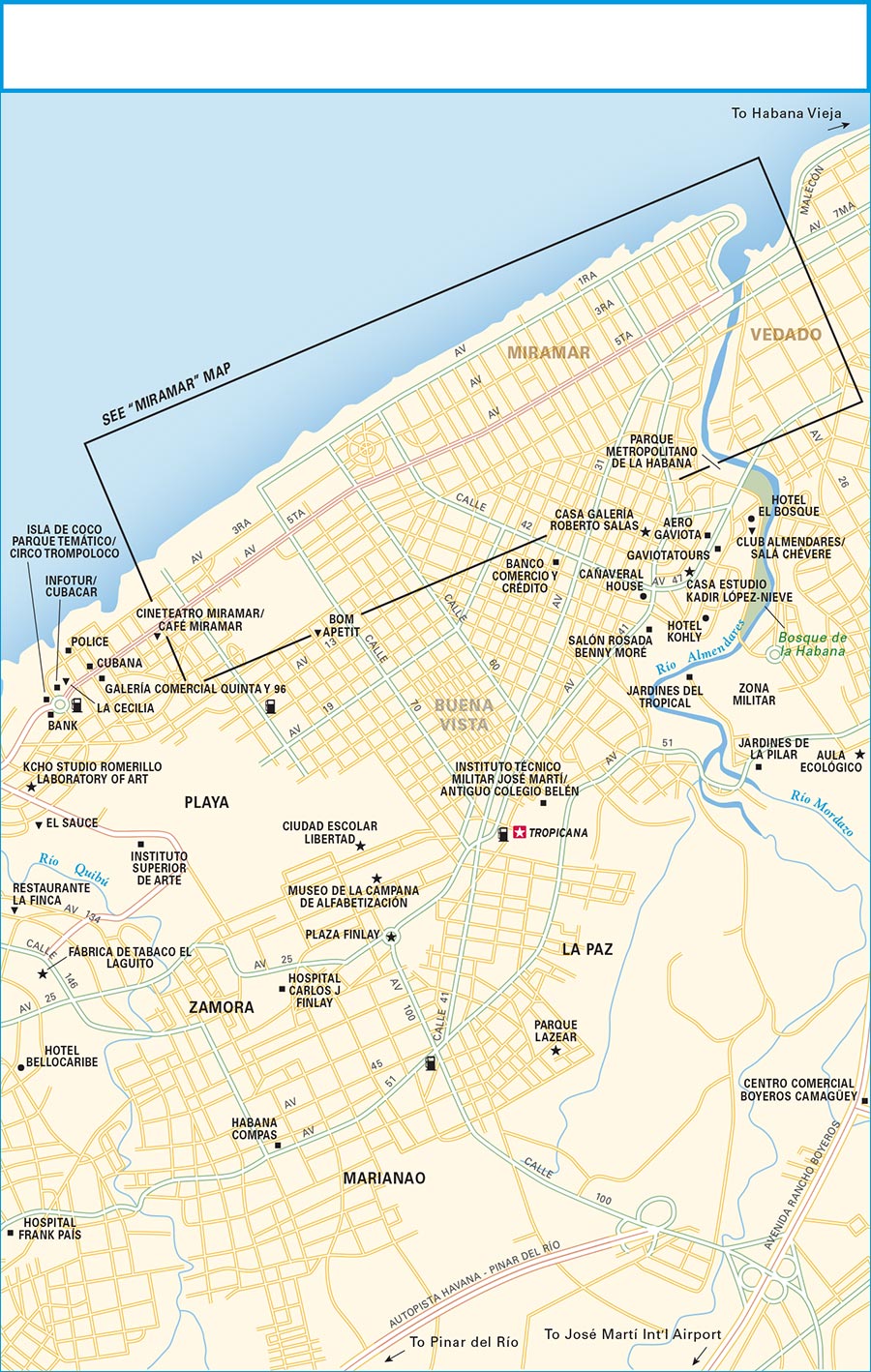

If you’re interested in beaux-arts or art deco architecture, then the once-glamorous Miramar, Cubanacán, and Siboney regions, west of Vedado, are worth exploring. Miramar also has excellent restaurants, deluxe hotels, and some of my favorite nightspots.

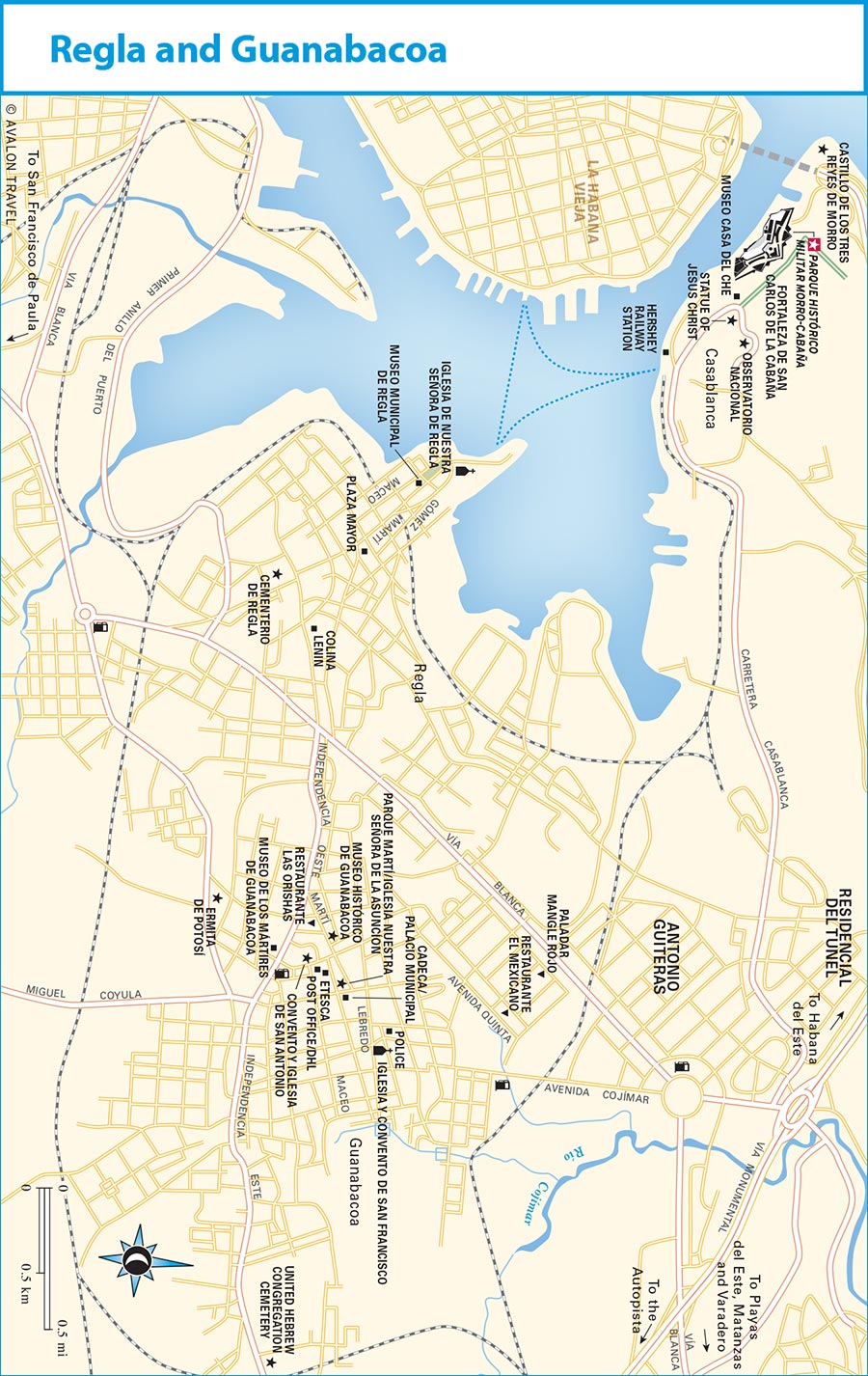

Most other sections of Havana are run-down residential districts of little interest to tourists. A few exceptions lie on the east side of Havana harbor. Regla and neighboring Guanabacoa are together a center of Santería and Afro-Cuban music. The 18th-century fishing village of Cojímar has Hemingway associations, and the nearby community of San Miguel del Padrón is where the great author lived for 20 years. A visit to his home, Finca Vigía, today the Museo Ernest Hemingway, is de rigueur. Combine it with a visit to the exquisite colonial Iglesia de Santa María del Rosario. About 15 kilometers east of the city, long, white-sand beaches—the Playas del Este—prove tempting on hot summer days.

In the suburban district of Boyeros, to the south, the Santuario de San Lázaro is an important pilgrimage site. A visit here can be combined with the nearby Mausoleo Antonio Maceo, where the hero general of the independence wars is buried outside the village of Santiago de las Vegas. A short distance east, the Arroyo Naranjo district has Parque Lenin, a vast park with an amusement park, horseback rides, boating, and more. Enthusiasts of botany can visit the Jardín Botánico Nacional.

Despite Havana’s great size, most sights of interest are highly concentrated, and most exploring is best done on foot.

The city was founded in July 1515 as San Cristóbal de la Habana, and was located on the south coast, where Batabanó stands today. The site was a disaster. On November 25, 1519, the settlers moved to the shore of the flask-shaped Bahía de la Habana. Its location was so advantageous that in July 1553 the city replaced Santiago de Cuba as the capital of the island.

Every spring and summer, Spanish treasure ships returning from the Americas crowded into Havana’s sheltered harbor before setting off for Spain in an armed convoy—la flota. By the turn of the 18th century, Havana was the third-largest city in the New World after Mexico City and Lima. The 17th and 18th centuries saw a surge of ecclesiastical construction and a perimeter wall was built.

In 1762, the English captured Havana but ceded it back to Spain the following year in exchange for Florida. The Spanish lost no time in building the largest fortress in the Americas—San Carlos de la Cabaña. Under the supervision of the new Spanish governor, the Marqués de la Torre, the city attained a new focus and rigorous architectural harmony. The first public gas lighting arrived in 1768. Most of the streets were cobbled. Along them, wealthy merchants and plantation owners erected beautiful mansions fitted inside with every luxury in European style.

By the mid-19th century, Havana was bursting its seams. In 1863, the city walls came tumbling down. New districts went up westward, and graceful boulevards pushed into the surrounding countryside, lined with a parade of quintas (summer homes) fronted by classical columns. By the mid-1800s, Havana had achieved a level of modernity that surpassed that of Madrid.

Following the Spanish-Cuban-American War, Havana entered a new era of prosperity. The city spread out, its perimeter enlarged by parks, boulevards, and dwellings in eclectic, neoclassical, and revivalist styles, while older residential areas settled into an era of decay.

By the 1950s Havana was a wealthy and thoroughly modern city with a large and prospering middle class, and had acquired skyscrapers such as the Focsa building and the Hilton (now the Habana Libre). Ministries were being moved to a new center of construction (today the Plaza de la Revolución), inland from Vedado. Gambling found new life, and casinos flourished.

Following the Revolution in 1959, a mass exodus of the wealthy and the middle class began, inexorably changing the face of Havana. Tourists also forsook the city, dooming Havana’s hotels, restaurants, and other businesses to bankruptcy. Festering slums and shantytowns marred the suburbs. The government ordered them razed. Concrete apartment blocks were erected on the outskirts. That accomplished, the Revolution turned its back on the city. Havana’s aged housing and infrastructure, much of it already decayed, have ever since suffered neglect.

Tens of thousands of poor peasant migrants poured into Havana from Oriente. The settlers changed the city’s demographic profile: Most of the immigrants were black; today, as many as 400,000 “palestinos,” immigrants from Santiago and the eastern provinces, live in Havana.

Finally, in the 1980s, the revolutionary government established a preservation program for Habana Vieja, and the Centro Nacional de Conservación, Restauración, y Museología was created to inventory Havana’s historic sites and implement a restoration program that would return the ancient city to pristine splendor. Much of the original city core now gleams afresh with confections in stone, while the rest is left to crumble.

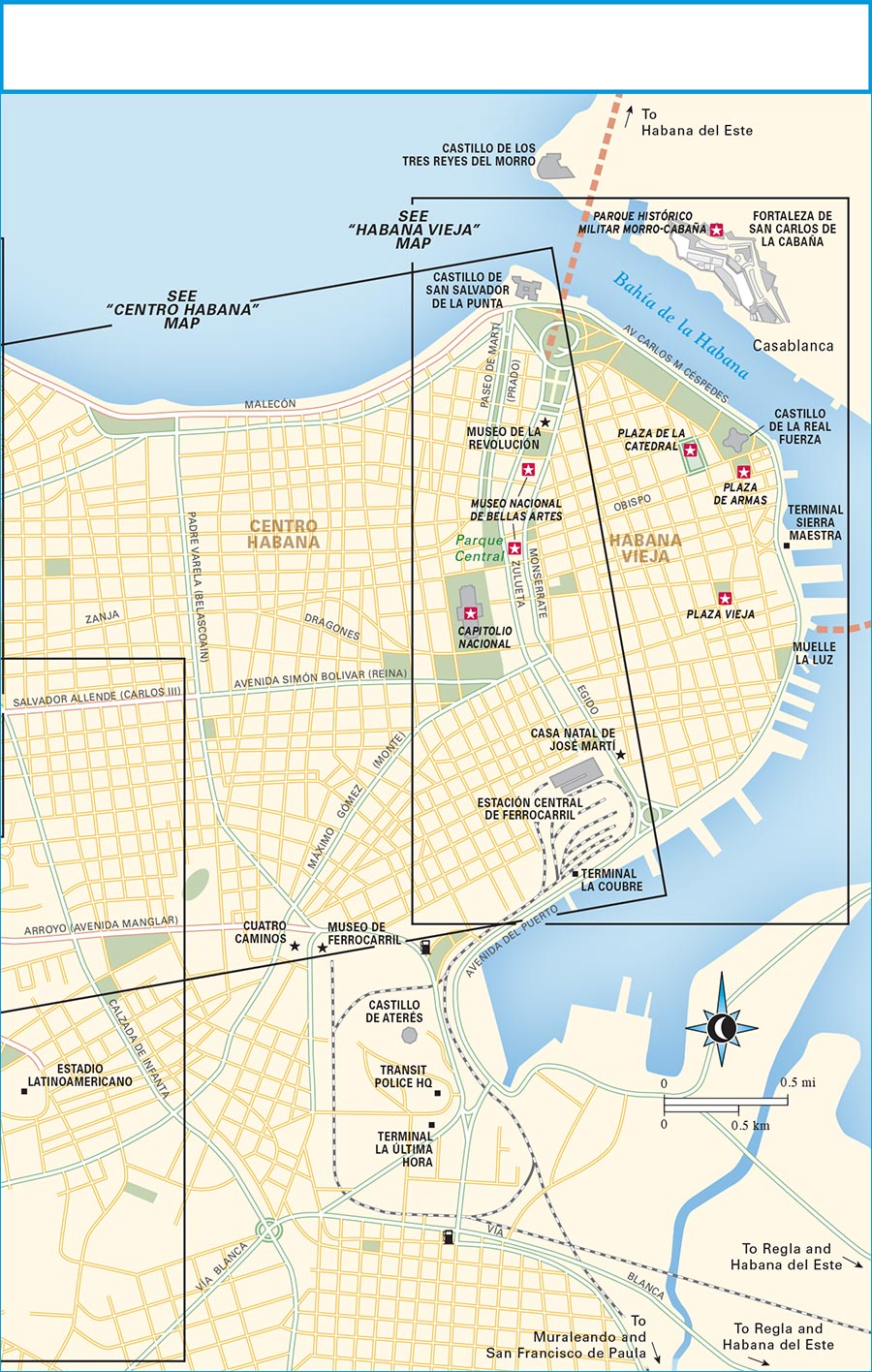

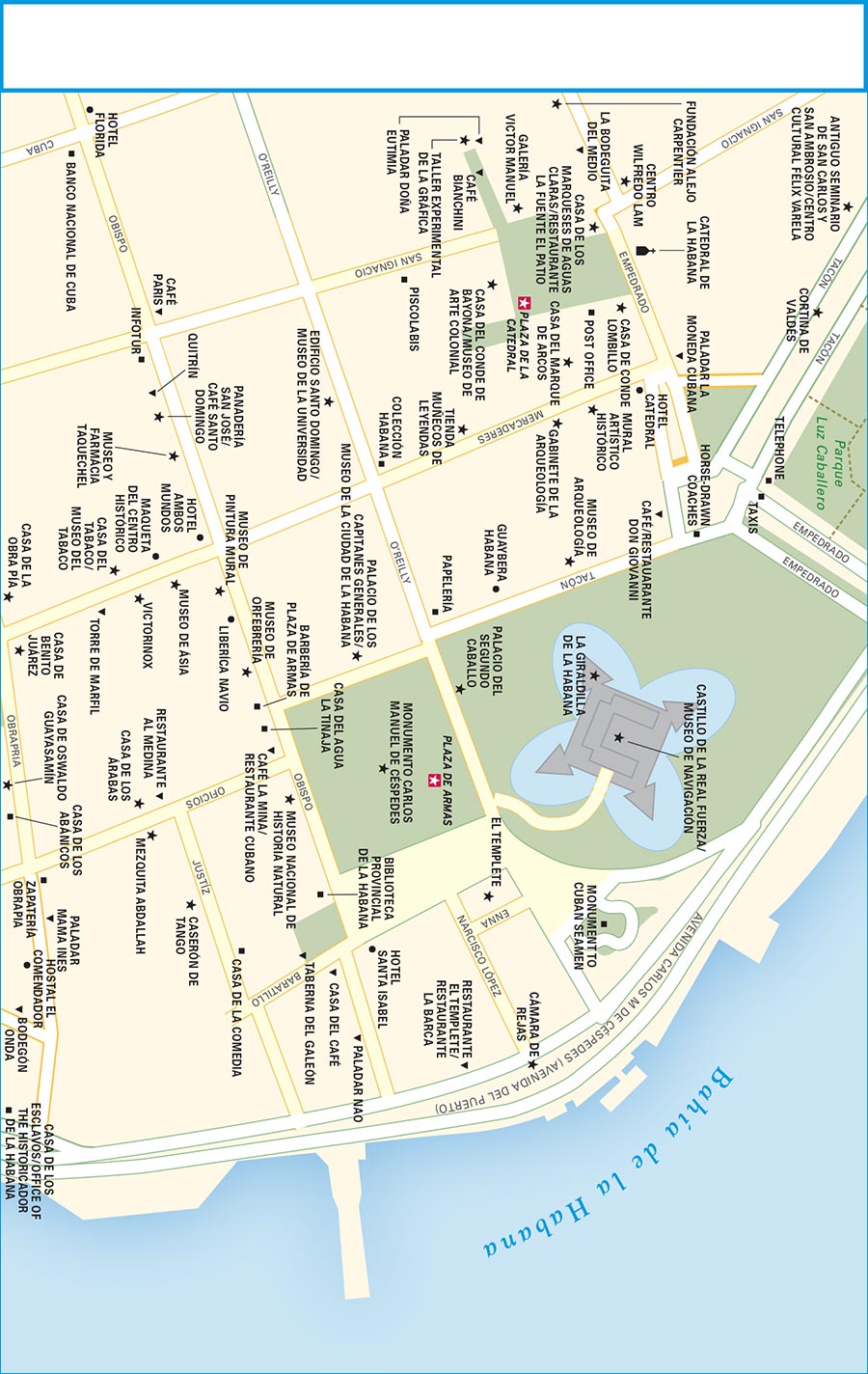

Habana Vieja (4.5 square km) is defined by the limits of the early colonial settlement that lay within fortified walls. The legal boundary of Habana Vieja includes the Paseo de Martí (Prado) and everything east of it.

Habana Vieja is roughly shaped like a diamond, with the Castillo de la Punta its northerly point. The Prado runs south at a gradual gradient from the Castillo de la Punta to Parque Central and, beyond, Parque de la Fraternidad. Two blocks east, Avenida de Bélgica parallels the Prado, tracing the old city wall to the harborfront at the west end of Desamparados. East of Castillo de la Punta, Avenida Carlos Manuel de Céspedes (Avenida del Puerto) runs along the harbor channel and curls south to Desamparados.

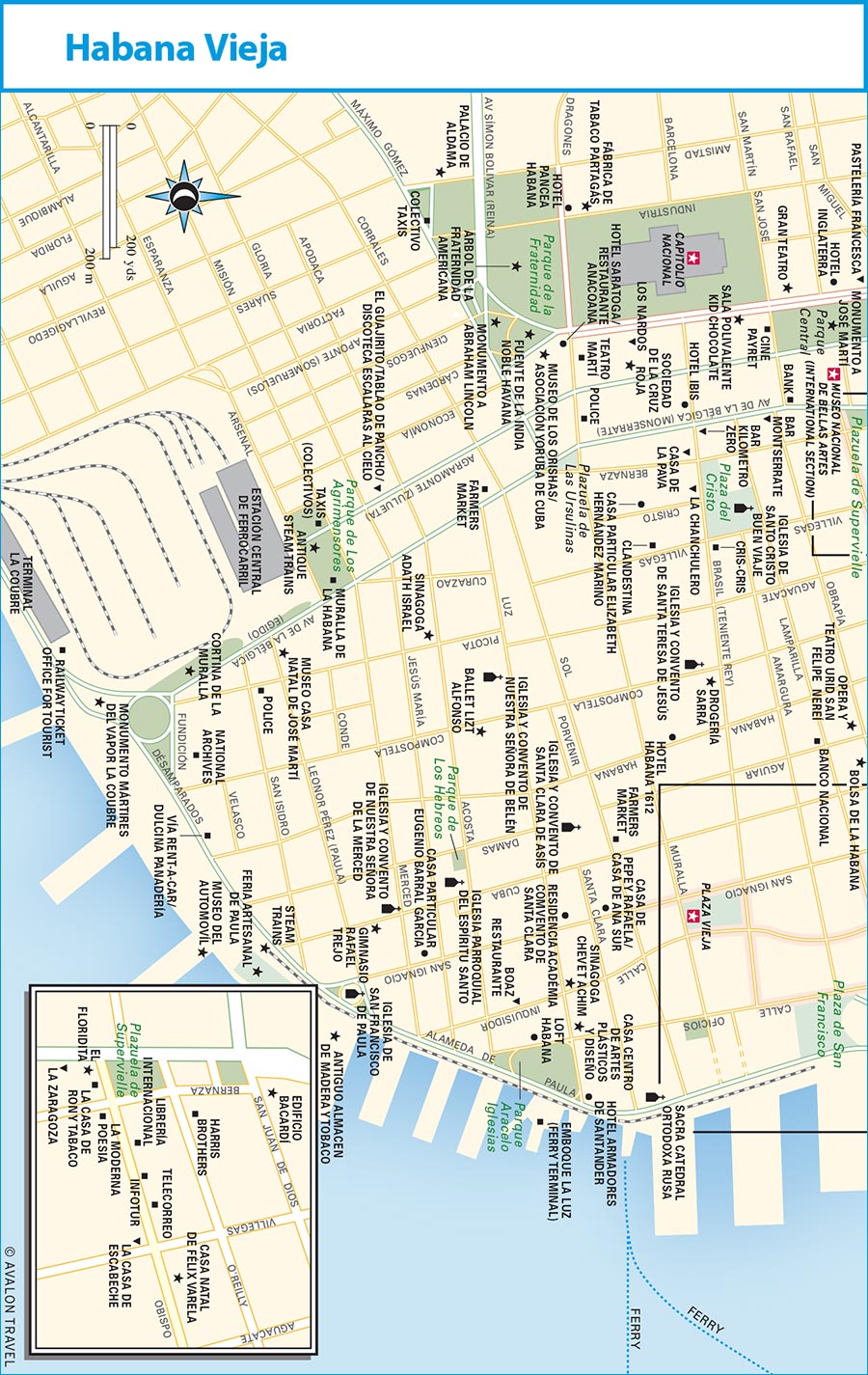

The major sites of interest are centered on Plaza de Armas, Plaza de la Catedral, Plaza Vieja, and Parque Central. Each square has its own flavor. The plazas and surrounding streets shine after a complete restoration that now extends to the area east of Avenida de Bélgica and southwest of Plaza Vieja, between Calles Brasil and Merced. This was the great ecclesiastical center of colonial Havana and is replete with churches and convents.

Habana Vieja is a living museum—as many as 60,000 people live within the confines of the old city wall—and suffers from inevitable ruination brought on by the tropical climate, hastened since the Revolution by years of neglect. The grime of centuries has been soldered by tropical heat into the chipped cement and faded pastels. Beyond the restored areas, Habana Vieja is a quarter of sagging, mildewed walls and half-collapsed balconies. The much-deteriorated (mostly residential) southern half of Habana Vieja requires caution.

The past few years have witnessed a spectacular tourist boom. Gentrification is sweeping pockets of Habana Vieja. Suddenly every third building in this overcrowded, once sclerotic northern extreme of Habana Vieja is in the throes of a remake as a boutique B&B, hip restaurant, or—what’s this?—a gourmet heladería selling homemade gelato. You’ll want to avoid Habana Vieja when the cruise ships are in.

Paseo de Martí, colloquially known as the Prado, is a kilometer-long tree-lined boulevard that slopes southward, uphill, from the harbor mouth to Parque Central. The beautiful boulevard was initiated by the Marqués de la Torre in 1772 and completed in 1852, when it had the name Alameda de Isabella II. It lay extramura (outside the old walled city) and was Havana’s most notable thoroughfare. Mansions of aristocratic families rose on each side and it was a sign of distinction to live here. The paseo—the daily carriage ride—along the boulevard was an important social ritual, with bands at regular intervals to play to the parade of volantas (carriages).

French landscape artist Jean-Claude Nicolas Forestier remodeled the Prado to its present form in 1929. It’s guarded by eight bronze lions, with an elevated central walkway bordered by an ornate wall with alcoves containing marble benches carved with scroll motifs. At night, it is lit by brass gas lamps with globes atop wrought-iron lampposts in the shape of griffins. Schoolchildren sit beneath shade trees, listening to lessons presented alfresco. An art fair is held on Sundays.

Heading downhill from Neptuno, the first building of interest, on the east side at the corner of Virtudes, is the former American Club—U.S. expat headquarters before the Revolution. The Palacio de Matrimonio (Prado #306, esq. Ánimas, tel. 07/866-0661, Tues.-Fri. 8am-6pm), on the west side at the corner of Ánimas, is where many of Havana’s wedding ceremonies are performed. The palace, built in 1914, boasts a magnificent neobaroque facade and spectacularly ornate interior.

The Moorish-inspired Hotel Sevilla (Trocadero #55) is like entering a Moroccan medina. It was inspired by the Patio of the Lions at the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. The hotel opened in 1908. The gallery walls are festooned with black-and-white photos of famous figures who have stayed here, from singer Josephine Baker and boxer Joe Louis to Al Capone, who took the entire sixth floor (Capone occupied room 615).

At Trocadero, budding dancers train for potential ballet careers in the Escuela Nacional de Ballet (National School of Ballet, Prado #207, e/ Colón y Trocadero, tel. 07/861-6629, cuballet@cubarte.cult.cu; entry by permission only). On the west side, the Casa de los Científicos (Prado #212, esq. Trocadero, tel. 07/862-1607), the former home of President José Miguel Gómez, first president of the republic, is now a hotel; pop in to admire the fabulous stained glass and the chapel.

dancers at the Escuela Nacional de Ballet

At Prado and Colón, note the art deco Cine Fausto, an ornamental band on its upper facade; two blocks north, examine the mosaic mural of a Nubian beauty on the upper wall of the Centro Cultural de Árabe (between Refugio and Trocadero).

The bronze statue of Juan Clemente-Zenea (1832-1871), at the base of the Prado, honors a nationalist poet shot for treason in 1871.

The small, recently restored Castillo de San Salvador de la Punta (Av. Carlos M. de Céspedes, esq. Prado y Malecón, tel. 07/860-3195, Wed.-Sun. 10am-6pm, CUC1) guards the entrance to Havana’s harbor channel at the base of the Prado. It was built in 1589 directly across from the Morro castle so that the two fortresses could catch invaders in a crossfire. A great chain was slung between them each night to secure Havana harbor.

Gazing over the plaza on the west side of the castle is a life-size statue of Venezuelan general Francisco de Miranda Rodríguez (1750-1816), while 100 meters east of the castle is a statue of Pierre D’Iberville (1661-1706), a Canadian explorer who died in Havana.

The park immediately south of the Castillo de San Salvador, on the south side of Avenida Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, at the base (and east) of the Prado, is divided in two by Avenida de los Estudiantes. Parque de los Enamorados (Park of the Lovers), on the north side of Avenida de los Estudiantes, features a statue of an Indian couple, plus the Monumento de Estudiantes de Medicina, a small Grecian-style temple shading the remains of a wall used by Spanish firing squads. On November 27, 1871, eight medical students met their deaths after being falsely accused of desecrating the tomb of a prominent loyalist. A trial found them innocent, but enraged loyalist troops held their own trial and shot the students, who are commemorated each November 27.

Parque de Mártires (Martyrs’ Park), on the south side of Avenida de los Estudiantes, occupies the ground of the former Tacón prison, built in 1838. Nationalist hero José Martí was imprisoned here 1869-1870. The Carcel de la Habana prison was demolished in 1939. Preserved are two of the punishment cells and the chapel used by condemned prisoners before being marched to the firing wall.

Spacious Parque Central is the social epicenter of Habana Vieja. The park—bounded by the Prado, Neptuno, Zulueta, and San Martín—is presided over by stately royal palms shading a marble statue of José Martí. It was sculpted by José Vilalta de Saavedra and inaugurated in 1905. Adjacent, baseball fanatics gather at a point called “esquina caliente” (“hot corner”) to argue the intricacies of pelota (baseball).

Parque Central, Habana Vieja

The park is surrounded by historic hotels, including the triangular Hotel Plaza (Zulueta #267), built in 1909, on the northeast face of the square. In 1920, baseball legend Babe Ruth stayed in room 216, preserved as a museum with his signed bat and ball in a case. Much of the social action happens in front of the Hotel Inglaterra (Paseo de Martí #416), opened in 1856 and today the oldest Cuban hotel still extant. The sidewalk, known in colonial days as the Acera del Louvre, was a focal point for rebellion against Spanish rule. A plaque outside the hotel entrance honors the “lads of the Louvre sidewalk” who died for Cuban independence. Inside, the hotel boasts elaborate wrought-ironwork and exquisite Mudejar-style detailing, including arabesque archways and azulejos (patterned tile). A highlight is the sensuous life-size bronze statue of a Spanish dancer—La Sevillana—in the main bar. Hopefully the fin de siècle charm will survive the 2016 remake initiated by U.S. hotel company Starwood.

Immediately south of the Inglaterra, the Gran Teatro (Paseo de Martí #452, e/ San Rafael y Neptuno, tel. 07/862-9473, guided tours Tue.-Sat. 9am-5pm, CUC2) originated in 1837 as the Teatro Tacón, drawing operatic luminaries such as Enrico Caruso and Sarah Bernhardt. The current neobaroque structure dates from 1915, when a social club—the Centro Gallego—was built around the old Teatro Tacón for the Galician community.

The building’s exorbitantly baroque facade drips with caryatids and has four towers, each tipped by a white marble angel reaching gracefully for heaven. It functions as a theater for the Ballet Nacional and Ópera Nacional de Cuba. The main auditorium, the exquisitely decorated 2,000-seat Teatro García Lorca, features a painted dome and huge chandelier. Smaller performances are hosted in the 500-seat Sala Alejo Carpentier and the 120-seat Sala Artaud. After a two-year restoration, it reopened in 2016 (in time for President Obama’s speech here) and is spectacularly illuminated at night.

The international section of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Fine Arts Museum, San Rafael, e/ Zulueta y Monserrate, tel. 07/863-9484 or 07/862-0140, www.bellasartes.cult.cu, Tues.-Sat. 9am-5pm, Sun. 10am-2pm, entrance CUC5, or CUC8 for both sections, guided tour CUC2) occupies the former Centro Asturiano, on the southeast side of the square. The building, lavishly decorated with neoclassical motifs, was erected in 1885 but rebuilt in Renaissance style in 1927 following a fire and housed the postrevolutionary People’s Supreme Court. A stained glass window above the main staircase shows Columbus’s three caravels.

The art collection is displayed on five floors covering 4,800 square meters. The works span the United States, Latin America, Asia, and Europe—including masters such as Gainsborough, Goya, Murillo, Rubens, Velásquez, and various Impressionists. The museum also boasts Latin America’s richest trove of Roman, Greek, and Egyptian antiquities. It has a top-floor restaurant.

The statuesque Capitolio Nacional (Capitol, Paseo de Martí, e/ San Martín y Dragones), one block south of Parque Central, dominates Havana’s skyline. It was built between 1926 and 1929 as Cuba’s Chamber of Representatives and Senate and designed after the U.S. Capitol. The 692-foot-long edifice is supported by colonnades of Doric columns, with semicircular pavilions at each end of the building. The lofty stone cupola rises 62 meters, topped by a replica of 16th-century Florentine sculptor Giambologna’s famous bronze Mercury.

A massive stairway—flanked by neoclassical figures in bronze by Italian sculptor Angelo Zanelli that represent Labor and Virtue—leads to an entrance portico with three tall bronze doors sculpted with 30 bas-reliefs that depict important events of Cuban history. Inside, facing the door is the Estatua de la República (Statue of the Republic), a massive bronze sculpture (also by Zanelli) of Cuba’s Indian maiden of liberty. At 17.5 meters (57 feet) tall, she is the world’s third-largest indoor statue (the other two are the gold Buddha in Nava, Japan, and the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC). In the center of the floor a replica of a 24-carat diamond marks Kilometer 0, the point from which all distances on the island are calculated.

The 394-foot-long Salón de los Pasos Perdidos (Great Hall of the Lost Steps), so named because of its acoustics, is inlaid with patterned marble motifs and features bronze bas-reliefs, green marble pilasters, and massive lamps on carved pedestals of glittering copper. Renaissance-style candelabras dangle from the frescoed ceiling. The semicircular Senate chamber and Chamber of Representatives are at each end.

At press time the building remained closed for a three-year restoration and will supposedly reopen as the home of the Asemblea Nacional.

Paseo de Martí (Prado) runs south from Parque Central three blocks, where it ends at the junction with Avenida Máximo Gómez (Monte). Here rises the Fuente de la India Noble Habana in the middle of the Prado. Erected in 1837, the fountain is surmounted by a Carrara marble statue of the legendary Indian queen. In one hand she bears a cornucopia, in the other a shield with the arms of Havana. Four fish at her feet occasionally spout water.

The Asociación Cultural Yoruba de Cuba (Prado #615, e/ Dragones y Monte, tel. 07/863-5953, www.yorubacuba.org, daily 9am-5pm) has a rather prosaic upstairs Museo de los Orishas (CUC10, students CUC3) dedicated to the orishas of Santería; no photos are permitted. The constitution for the republic was signed in 1901 in the restored Teatro Martí (Dragones, esq. Zulueta), one block west of the Prado.

The Parque de la Fraternidad (Friendship Park) was laid out in 1892 on an old military drill square, the Campo de Marte, to commemorate the fourth centennial of Columbus’s discovery of America. The current layout by Jean-Claude Nicolas Forestier dates from 1928. The Árbol de la Fraternidad Americana (Friendship Tree) was planted at its center on February 24, 1928, to cement goodwill between the nations of the Americas. Busts and statues of outstanding American leaders such as Simón Bolívar and Abraham Lincoln watch over.

The Palacio de Aldama (Amistad #510, e/ Reina y Estrella), on the park’s far southwest corner, is a grandiose mansion built in neoclassical style in 1844 for a wealthy Basque, Don Domingo Aldama y Arrechaga. Its facade is lined by Ionic columns and the interior features murals of scenes from Pompeii. It is not open to the public.

To the park’s northeast side, a former graveyard for rusting antique steam trains has been cleared to make way for a new hotel, Pancea Havana Cuba.

The original Partagás Cigar Factory (Industria #520, e/ Dragones y Barcelona), on the west side of the Capitolio, features a four-story classical Spanish-style facade capped by a roofline of baroque curves topped by lions. It closed in 2010 for repair and remained so at press time, with little sign of progress. The cigar-making facility moved to the former El Rey del Mundo factory (Luceña #816, esq. Penalver, Centro Habana) and is open for tours. The factory specialized in full-bodied Partagás cigars, started in 1843 by Catalan immigrant Don Jaime Partagás Ravelo. Partagás was murdered in 1868—some say by a rival who discovered that Partagás was having an affair with his wife—and his ghost is said to haunt the building. A tobacco shop and cigar lounge remain open on the ground floor (tel. 07/863-5766).

Calle Agramonte, more commonly referred to by its colonial name of Zulueta, parallels the Prado and slopes gently upward from Avenida de los Estudiantes to the northeast side of Parque Central. Traffic runs one-way uphill.

At its north end is the Monumento al General Máximo Gómez. This massive monument of white marble by sculptor Aldo Gamba was erected in 1935 to honor the Dominican-born hero of the Cuban wars of independence who led the Liberation Army as commander-in-chief. Gómez (1836-1905) is cast in bronze, reining in his horse.

One block north of Parque Central, at the corner of Zulueta and Ánimas, is Sloppy Joe's, commemorated as Freddy’s Bar in Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not. Restored in 2013, it reopened its doors after decades lying shuttered and near-derelict.

The old Cuartel de Bomberos fire station houses the tiny Museo de Bomberos (Museum of Firemen, Zulueta #257, e/ Neptuno y Ánimas, tel. 07/863-4826, Tues.-Fri. 9:30am-5pm, free), displaying a Merryweather engine from 1894 and antique firefighting memorabilia.

Immediately beyond the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes and Museo de la Revolución is Plaza 13 de Marzo, a grassy park named to commemorate the ill-fated attack of the presidential palace by student martyrs on March 13, 1957. At the base of Zulueta, at the junction with Cárcel, note the flamboyant art nouveau building housing the Spanish Embassy.

The ornate building facing north over Plaza 13 de Marzo was initiated in 1913 to house the provincial government. Before it could be finished (in 1920), it was earmarked as the Palacio Presidencial (Presidential Palace), and Tiffany’s of New York was entrusted with its interior decoration. It was designed by Belgian Paul Belau and Cuban Carlos Maruri in an eclectic style, with a lofty dome. Following the Revolution, the three-story palace was converted into the dour Museo de la Revolución (Museum of the Revolution, Refugio #1, e/ Zulueta y Monserrate, tel. 07/862-4091, daily 9am-5pm, CUC8, cameras CUC2, guide CUC2). It is fronted by a SAU-100 Stalin tank used during the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 and a semi-derelict watchtower, Baluarte de Ángel, erected in 1680.

Museo de la Revolución

The marble staircase leads to the Salón de los Espejos (the Mirror Room), a replica of that in Versailles (replete with paintings by Armando Menocal); and Salón Dorado (the Gold Room), decorated with gold leaf and highlighted by its magnificent dome.

Rooms are divided chronologically. Maps describe the progress of the revolutionary war. Guns and rifles are displayed alongside grisly photos of dead and tortured heroes. The Rincón de los Cretinos (Corner of Cretins) pokes fun at Batista, Ronald Reagan, and George Bush. There’s a café to the rear.

At the rear, in the former palace gardens, is the Granma Memorial, preserving the vessel that brought Castro and his revolutionaries from Mexico to Cuba in 1956. The Granma is encased in a massive glass structure. It’s surrounded by vehicles used in the revolutionary war: armored vehicles, the bullet-riddled “Fast Delivery” truck used in the student commandos’ assault on the palace on March 13, 1957 (Batista escaped through a secret door), and Castro’s Toyota jeep from the Sierra Maestra. There’s also a turbine from the U-2 spy plane downed during the missile crisis in 1962, plus a Sea Fury aircraft and a T-34 tank.

The Cuban section of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Fine Arts Museum, Trocadero, e/ Zulueta y Monserrate, tel. 07/863-9484 or 07/862-0140, www.bellasartes.cult.cu, Tues.-Sat. 9am-5pm, Sun. 10am-2pm, entrance CUC5, or CUC8 for both sections, guided tour CUC2) is housed in the soberly classical Palacio de Bellas Artes. The museum features an atrium garden from which ramps lead to two floors exhibiting a complete spectrum of Cuban paintings, engravings, sketches, and sculptures. Works representing the vision of early 16th- and 17th-century travelers merge into colonial-era pieces, early 20th-century Cuban interpretations of Impressionism, Surrealism, and works spawned by the Revolution.

Avenida de los Misiones, or Monserrate as everyone knows it, parallels Zulueta one block to the east (traffic is one-way, downhill) and follows the space left by the ancient city walls. At the base of Monserrate, at its junction with Calle Tacón, is the once lovely Casa de Pérez de la Riva (Capdevila #1), built in Italian Renaissance style in 1905. It was closed for restoration at press time and is due to reopen as the Museo de la Música.

Immediately north is a narrow pedestrian alley (Calle Aguiar e/ Peña Pobre y Capdevila) known as Callejón de los Peluqueros (Hairdressers’ Alley). Adorned with colorful murals, it’s the venue for the community ArteCorte project—the inspiration of local stylist Gilberto “Papito” Valladares—and features barber shops, art galleries, and cafés. Papito (Calle Aguiar #10, tel. 07/861-0202) runs a hairdressers’ school and salon that doubles as a barbers’ museum.

The Gothic Iglesia del Santo Ángel Custodio (Monserrate y Cuarteles, tel. 07/861-8873), immediately east of the Palacio Presidencial, sits atop a rock known as Angel Hill. The church was founded in 1687 by builder-bishop Diego de Compostela. The tower dates from 1846, when a hurricane toppled the original, while the facade was reworked in neo-Gothic style in the mid-19th century. Cuba’s national hero, José Martí, was baptized here on February 12, 1853.

The church was the setting for the tragic marriage scene that ends in the violent denouement on the steps of the church in the 19th-century novel Cecilia Valdés by Cirilo Villaverde. A bust of the author and a statue of Cecilia grace the Plazuela de Santo Ángel outside the main entrance (the corner of Calles Compostela and Cuarteles). This colorful little plaza is a popular venue for music-video and film shoots.

The Edificio Bacardí (Bacardí Building, Monserrate #261, esq. San Juan de Dios), former headquarters of the Bacardí rum empire, is a stunning exemplar of art deco design. Designed by Cuban architect Esteban Rodríguez and finished in December 1929, it is clad in Swedish granite and local limestone. Terra-cotta of varying hues accents the building, with motifs showing Grecian nymphs and floral patterns. It’s crowned by a Lego-like pyramidal bell tower topped with a brass bat—the famous Bacardí motif. The building now houses various offices. The Café Barrita bar (daily 9am-6pm), a true gem of art deco design, is to the right of the lobby, up the stairs.

The famous restaurant and bar El Floridita (corner of Monserrate and Calle Obispo, tel. 07/867-1299, www.floridita-cuba.com, daily 11:30am-midnight) has been serving food since 1819, when it was called Pina de Plata. You expect a spotlight to come on and Desi Arnaz to appear conducting a dance band, and Hemingway to stroll in as he would every morning when he lived in Havana and drank with Honest Lil, the Worst Politician, and other real-life characters from his novels. A life-size bronze statue of Hemingway, by sculptor José Villa, leans on the dark mahogany bar where Constante Ribailagua once served frozen daiquiris to the great writer (Hemingway immortalized both the drink and the venue in his novel Islands in the Stream) and such illustrious guests as Gary Cooper, Tennessee Williams, Marlene Dietrich, and Jean-Paul Sartre.

El Floridita has been spruced up for tourist consumption with a 1930s art deco polish. They’ve overpriced the place, but sipping a daiquiri here is a must. Depsite the restaurant’s fantastic fin de siècle ambience, dining is subpar.

Plaza del Cristo lies at the west end of Amargura, between Lamparilla and Brasil, one block east of Monserrate. It was here that Wormold, the vacuum-cleaner salesman turned secret agent, was “swallowed up among the pimps and lottery sellers of the Havana noon” in Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana. Wormold and his daughter, Millie, lived at the fictional 37 Lamparilla.

The plaza is dominated by the tiny Iglesia de Santo Cristo Buen Vieja (Villegas, e/ Amargura y Lamparilla, tel. 07/863-1767, daily 9am-noon), dating from 1732, but with a Franciscan hermitage dating from 1640. Buen Viaje was the final point of the Vía Crucis (the Procession of the Cross) held each Lenten Friday and beginning at the Iglesia de San Francisco de Asís. The church, named for its popularity among sailors, who pray here for safe voyages, has an impressive cross-beamed wooden ceiling and exquisite altars, including one to the Virgen de la Caridad showing three boatmen being saved from a tempest.

The handsome Iglesia y Convento de Santa Teresa de Jesús (Brasil, esq. Compostela, tel. 07/861-1445), two blocks east of Plaza del Cristo, was built by the Carmelites in 1705. The church is still in use, although the convent ceased to operate as such in 1929, when the nuns were moved out and the building was converted into a series of homes.

Across the road is the Drogería Sarrá (Brasil, e/ Compostela y Habana, tel. 07/866-7554, daily 9am-5pm, free), a fascinating apothecary that is now the Museo de la Farmacia Habanera. Its paneled cabinets are still stocked with herbs and pharmaceuticals in colorful old bottles and ceramic jars.

Throughout most of the colonial era, sea waves washed up on a beach that lined the southern shore of the harbor channel and bordered what is today Calle Cuba and, eastward, Calle Tacón, which runs along the site of the old city walls forming the original waterfront. In the early 19th century, the area was extended with landfill, and a broad boulevard—Avenida Carlos Manuel de Céspedes (Avenida del Puerto)—was laid out along the new harborfront. Parque Luz Caballero, between the avenida and Calle Tacón, is pinned by a statue of José de la Luz Caballero (1800-1862), a philosopher and nationalist. In 2014, a statue of feudal samurai Hasekura Tsunenaga (the first Japanese to visit Cuba, in 1614) was erected.

Overlooking the harborfront at the foot of Empedrado is the Fuente de Neptuno (Neptune Fountain), erected in 1838.

The giant and beautiful modernist glass cube at the Avenida del Puerto and Calle Narciso López, by Plaza de Armas, is the Cámara de Rejas, the new sewer gate. Educational panels tell the history of Havana’s sewer system.

Calle Cuba extends east from the foot of Monserrate. At the foot of Calle Cuarteles is the Palacio de Mateo Pedroso y Florencia, known today as the Palacio de Artesanía (Artisans Palace, Cuba #64, e/ Tacón y Peña Pobre, Mon.-Sat. 9am-8pm, Sat. 9am-2pm, free), built in Moorish style for nobleman Don Mateo Pedroso around 1780. Pedroso’s home displays the typical architectural layout of period houses, with stores on the ground floor, slave quarters on the mezzanine, and the owner’s dwellings above. Today it houses craft shops, boutiques, and folkloric music.

Immediately east is Plazuela de la Maestranza, where a remnant of the old city wall is preserved. On its east side, in the triangle formed by the junction of Calles Cuba, Tacón, and Chacón, is a medieval-style fortress, El Castillo de Atane, a police headquarters built in 1941 as a pseudo-colonial confection.

The Seminario de San Carlos y San Ambrosio, a massive seminary running the length of Tacón east of El Castillo de Atane, was established by the Jesuits in 1721 and is now the Centro Cultural Félix Varela (e/ Chacón y Empedrado, tel. 07/862-8790, www.cfv.org.cu, Mon.-Sat. 9am-4pm, free). The downstairs cloister is open to the public.

The entrance to the seminary overlooks an excavated site showing the foundations of the original seafront section of the city walls, here called the Cortina de Valdés.

Tacón opens to a tiny plazuela at the junction with Empedrado, where horse-drawn cabs called calezas offer guided tours. The Museo de Arqueología (Tacón #12, e/ O’Reilly y Empedrado, tel. 07/861-4469, Tues.-Sat. 9am-2pm, CUC1) displays pre-Columbian artifacts, plus ceramics and items from the early colonial years. The museum occupies Casa de Juana Carvajal, a mansion first mentioned in documents in 1644, and features floor-to-ceiling murals depicting 18th-century life.

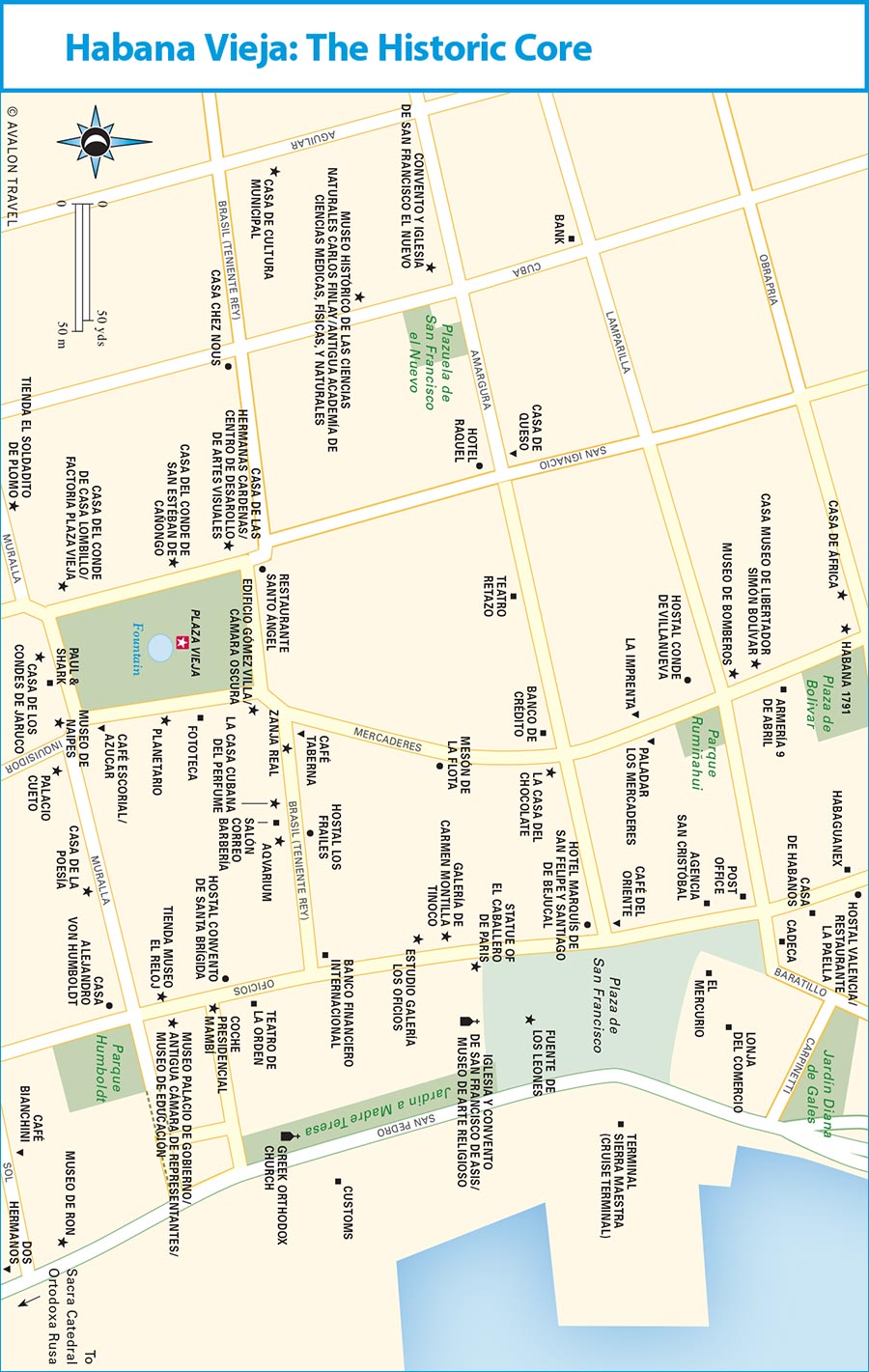

The exquisite cobbled Plaza de la Catedral (Cathedral Square) was the last square to be laid out in Habana Vieja. It occupied a lowly quarter where rainwater and refuse collected (it was originally known as the Plazuela de la Ciénaga—Little Square of the Swamp). A cistern was built in 1587, and only in the following century was the area drained. Its present texture dates from the 18th century. The square is Habana Vieja at its most quintessential, the atmosphere enhanced by women in traditional costume who will pose for your camera for a small fee.

Plaza de la Catedral

On the north side of the plaza and known colloquially as Catedral Colón (Columbus Cathedral) is the Catedral San Cristóbal de la Habana (St. Christopher’s Cathedral, tel. 07/861-7771, Mon.-Fri. 9am-5pm, Sat.-Sun. 9am-noon, tower tour CUC1), initiated by the Jesuits in 1748. The order was kicked out of Cuba by Carlos III in 1767, but the building was eventually completed in 1777 and altered again in the early 19th century. The original baroque interior (including the altar) is gone, replaced in 1814 by a classical interior.

The baroque facade is adorned with clinging columns and ripples like a great swelling sea; Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier thought it “music turned to stone.” A royal decree of December 1793 elevated the church to a cathedral. A second bell tower, narrower than the first, was added. Columns divide the rectangular church into three naves. The neoclassical main altar is made of wood; the murals above are by Italian painter Guiseppe Perovani. The chapel immediately to the left has several altars. Note the wooden image of Saint Christopher, patron saint of Havana, dating to 1633.

The Spanish believed that a casket brought to Havana from Santo Domingo in 1796 and that resided in the cathedral for more than a century held the ashes of Christopher Columbus. It was returned to Spain in 1899. All but the partisan habaneros now believe that the ashes were those of Columbus’s son Diego.

This splendid mansion, on the northwest side of the plaza, was built during the 16th century by Governor General Gonzalo Pérez de Angulo and has since been added to by subsequent owners. Today a café occupies the portico; the inner courtyard, with its fountain, houses the Restaurante El Patio. The upstairs restaurant offers splendid views over the plaza. Sunlight pouring in through stained glass mediopuntos saturates the floors with shifting colors.

This simple two-story structure, on the south side of the square, is a perfect example of the traditional Havana merchant’s house of the period, with side stairs and an entresuelo (mezzanine of half-story proportions). It was built in the 1720s for Governor General Don Luis Chacón. Today it houses the Museo de Arte Colonial (Colonial Art Museum, San Ignacio #61, tel. 07/862-6440, daily 9:30am-5pm, entrance CUC2, cameras CUC5, guides CUC1), which re-creates the lavish interior of an aristocratic colonial home. One room is devoted to colorful stained glass vitrales.

At the southwest corner of the plaza, this short cul-de-sac is where a cistern was built to supply water to ships in the harbor. The aljibe (cistern) marked the terminus of the Zanja Real (the “royal ditch,” or chorro), a covered aqueduct that brought water from the Río Almendares some 10 kilometers away.

The Casa de Baños, which faces onto the square, looks quite ancient but was built in the 20th century in colonial style on the site of a bathhouse erected over the aljibe. Today the building contains the Galería Victor Manuel (San Ignacio #56, tel. 07/861-2955, daily 9am-8pm), selling quality arts.

At the far end of Callejón del Chorro is the not-to-be-missed Taller Experimental de la Gráfica (tel. 07/864-7622, tgrafica@cubarte.cult.cu, Mon.-Fri. 9am-4pm), a graphics cooperative where you can watch artists make prints for sale using antique presses and lithographic stones.

On the plaza’s east side is the Casa de Conde de Lombillo (tel. 07/860-4311, Mon.-Fri. 9am-5pm, Sat. 9am-1pm, free). Built in 1741, this former home of a slave trader houses a small post office (Cuba’s first), as it has since 1821. The building now holds historical lithographs. The mansion adjoins the Casa del Marqués de Arcos, built in the 1740s for the royal treasurer. What you see is the rear of the mansion; the entrance is on Calle Mercaderes, where the building facing the entrance is graced by the Mural Artístico-Histórico, by Cuban artist Andrés Carrillo. A restoration of the mansion was completed in 2017; the venue now hosts the Café Literario Marque de Arcos café, library, and exhibition space.

The two houses are fronted by a wide portico supported by thick columns. Note the mailbox set into the wall, a grotesque face of a tragic Greek mask carved in stone, with a scowling mouth as its slit. A life-size bronze statue of Spanish flamenco dancer Antonio Gades (1936-2004) leans against one of the columns.

The Centro Wilfredo Lam (San Ignacio #22, esq. Empedrado, tel. 07/864-6282, www.wlam.cult.cu, Tues.-Sat. 10am-5pm), on cobbled Empedrado, on the northwest corner of the plaza, occupies the former mansion of the counts of Peñalver. This art center displays works by the eponymous Cuban artist as well as artists from Latin America. The institution studies and promotes contemporary art from around the world.

No visit to Havana is complete without popping into La Bodeguita del Medio (Empedrado #207, tel. 07/866-8857, daily 10am-midnight), half a block west of the cathedral. This neighborhood hangout was originally the coach house of the mansion next door. Later it was a bodega, a mom-and-pop grocery store where Spanish immigrant Ángel Martínez served food and drinks.

Today troubadours move among thirsty turistas and the house drink is the somewhat weak mojito. Adorning the walls are posters, paintings, and faded photos of Ernest Hemingway, Carmen Miranda, and other famous visitors. The walls were once decorated with the signatures and scrawls of visitors dating back decades. Alas, a renovation wiped away much of the original charm; the artwork was erased and replaced in ersatz style, with visitors being handed blue pens (famous visitors now sign a chalkboard). The most famous graffiti is credited to Hemingway: “Mi mojito en La Bodeguita, mi daiquirí en El Floridita,” he supposedly scrawled on the sky-blue walls. According to Tom Miller in Trading with the Enemy, Martínez concocted the phrase as a marketing gimmick after the writer’s death. Errol Flynn thought it “A Great Place to Get Drunk.”

Built in the 1820s, at the peak of the baroque era, this home has a trefoil-arched doorway opening onto a zaguán (courtyard). Exquisite azulejos (painted tiles) decorate the walls. Famed novelist Alejo Carpentier used the house as the main setting for his novel El Siglo de las Luces (The Enlightenment). A portion of the home, which houses the Centro de Promoción Cultural, is dedicated to his memory as the Fundación Alejo Carpentier (Empedrado #215, tel. 07/861-5506, www.fundacioncarpentier.cult.cu, Mon.-Fri. 8:30am-4:30pm, free).

One block west, tiny Plazuela de San Juan de Dios (Empedrado, e/ Habana y Aguiar) is pinned by a white marble facsimile of Don Quixote author Miguel de Cervantes sitting in a chair, pen in hand, lending the plaza its colloquial name: Parque Cervantes. Visitors on the revolutionary trail should continue one block north up Aguiar to Calle Tejadillo. To the right is the Museo Bufete Aspiazo-Castro-Risende (Tejadillo #57; tel. 07/861-5001, by appointment), the office where Fidel Castro worked as a lawyer 1950-1952. The Arzobispado de la Habana, the 18th-century home of the archbishop, is one block west at the corner of Tejadillo and Habana. The lovely interior is closed to public view.

The oldest and most important plaza in Habana Vieja, handsome Arms Square was laid out in 1519 and named Plaza de Iglesia for a church that was demolished in 1741 after an English warship, the ill-named HMS Invincible, was struck by lightning and exploded, sending its main mast sailing down on the church. Later, Plaza de Armas evolved to become the settlement’s administrative center, when military parades and musical concerts were held and the gentry would take their evening promenade.

Cuban man painting in Plaza de Armas

Off the southeast corner of the square, tucked off Calle Baratillo, is an enclosed plazuela—the setting for Feria de Publicaciones y Curiosidades, with stalls selling tatterdemalion antiquarian books and small antiquities.

The somber yet stately Palacio de los Capitanes Generales (Palace of the Captains-Generals) was completed in 1791 and became home to 65 governors of Cuba between 1791 and 1898. After that, it was the U.S. governor’s residence, the early seat of the Cuban government (1902-1920), and Havana’s city hall (1920-1967).

The palace is fronted by a loggia supported by Ionic columns and by “cobblewood,” laid instead of stone to soften the noise of carriages and thereby lessen the disturbance of the governor’s sleep. The three-story structure surrounds a courtyard that contains a statue of Christopher Columbus by Italian sculptor Cucchiari. Arched colonnades rise on all sides. In the southeast corner, a hole containing the coffin of a nobleman is one of several graves from the old Cementerio de Espada. To the north end of the loggia is a marble statue of Fernando VII.

Today, the palace houses the Museo de la Ciudad de la Habana (City of Havana Museum, Tacón #1, e/ Obispo y O’Reilly, tel. 07/861-5001, Tues.-Sun. 9:30am-5pm, last entry at 4pm, entrance CUC3, cameras CUC5, guide CUC5). The stairs lead up to palatially furnished rooms. The Salón del Trono (Throne Room), made for the king of Spain but never used, is of breathtaking splendor. The museum also features the Salón de las Banderas (Hall of Flags), with magnificent artwork that includes The Death of Antonio Maceo by Menocal, plus exquisite collections illustrating the story of the city’s (and Cuba’s) development and the 19th-century struggles for independence.

On the park’s northwest corner, the austere Palacio del Segundo Cabo (Palace of the Second Lieutenant, O’Reilly #14, tel. 07/862-8091, Mon.-Fri. 6am-midnight) dates from 1770, when it was designed as the city post office. Later it became the home of the vice governor-general and, after independence, the seat of the Senate. Today it is a cultural center.

The pocket-size Castillo de la Real Fuerza (Royal Power Castle, O’Reilly #2, tel. 07/864-4490, Tues.-Sun. 9:30am-5pm, entrance CUC3, cameras CUC5), on the northeast corner of the plaza, was begun in 1558 and completed in 1577. It’s the oldest of the four forts that guarded the New World’s most precious harbor. Built in medieval fashion, with walls 6 meters wide and 10 meters tall, the castle forms a square with enormous triangular bulwarks at the corners, their sharp angles slicing the dark waters of the moat. It was almost useless from a strategic point of view, being landlocked far from the mouth of the harbor channel and hemmed in by surrounding buildings that would have formed a great impediment to its cannons in any attack. The governors of Cuba lived here until 1762.

Visitors enter via a courtyard full of cannons and mortars. Note the royal coat of arms carved in stone above the massive gateway as you cross the moat by a drawbridge.

The castle houses the not-to-be-missed Museo de Navegación (Naval Museum), displaying treasures from the golden age when the riches of the Americas flowed to Spain. The air-conditioned Sala de Tesoro gleams with gold bars and coins, plus precious jewels, bronze astrolabes, and silver reales (“pieces of eight”). The jewel in the crown is a four-meter interactive scale model of the Santisima Trinidad galleon, built in Havana 1767-1770 and destroyed at the Battle of Trafalgar.

A cylindrical bell tower rising from the northwest corner is topped by a bronze weathervane called La Giraldilla de la Habana showing a voluptuous figure with hair braided in thick ropes; in her right hand is a palm tree and in her left a cross. This figure is the official symbol of Havana. The vane is a copy; the original, which now resides in the foyer, was cast in 1631 in honor of Isabel de Bobadilla, the wife of Governor Hernando de Soto, the tireless explorer who fruitlessly searched for the fountain of youth in Florida. De Soto named his wife governor in his absence—the only female governor ever to serve in Cuba. For four years she scanned the horizon in vain for his return.

Immediately east of the castle, at the junction of Avenida del Puerto and O’Reilly, is an obelisk to the 77 Cuban seamen killed during World War II by German submarines.

A charming copy of a Doric temple, El Templete (The Pavilion, daily 9:30am-5pm, CUC1.50 including guide) stands on the northeast corner of the Plaza de Armas. It was inaugurated on March 19, 1828, on the site where the first mass and town council meeting were held in 1519, beside a massive ceiba tree. The original ceiba was felled by a hurricane in 1828 and replaced by a column fronted by a small bust of Christopher Columbus. A ceiba has since been replanted and today shades the tiny temple; its interior features a wall-to-ceiling triptych depicting the first mass, the council meeting, and El Templete’s inauguration. In the center of the room sits a bust of the artist, Jean-Baptiste Vermay (1786-1833).

Immediately south of El Templete is the former Palacio del Conde de Santovenia (Baratillo, e/ Narciso López y Baratillo y Obispo). Its quintessentially Cuban-colonial facade is graced by a becolumned portico and, above, wrought-iron railings on balconies whose windows boast stained glass mediopuntos. The conde (count) in question was famous for hosting elaborate parties, most notoriously a three-day bash in 1833 to celebrate the accession to the throne of Isabel II that climaxed with the ascent of a gaily decorated gas-filled balloon. Later that century the building served as a hotel. Today it’s the Hotel Santa Isabel. President Carter stayed here during his visit to Havana in 2002.

On the south side of the plaza, the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural (Natural History Museum, Obispo #61, e/ Oficios y Baratillo, tel. 07/863-9361, museo@mnhnc.inf.cu, Tues.-Sun. 9:30pm-5pm, CUC3) covers evolution in a well-conceived display. The museum houses collections of Cuban flora and fauna—many in clever reproductions of their natural environments—plus stuffed tigers, apes, and other beasts from around the world. Children will appreciate the interactive displays.

Immediately east, the Biblioteca Provincial de la Habana (Havana Provincial Library, tel. 07/862-9035, Mon.-Fri. 8:15am-7pm, Sat. 8:15am-4:30pm, Sun. 8:15am-1pm) once served as the U.S. Embassy.

One block south along Calle Oficios, at the corner of Justiz, the former Depósito del Automóvil has been beautifully restored as Mezquita Abdallah (Oficios #18, no tel.)—a mosque and the only place in Havana where Muslims can practice the Islamic faith. The prayer hall is decorated with hardwoods inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Only Muslims may enter, but you can peer in at the beautiful Mughal architecture through glass-panel doors.

Across the street, the Casa de los Árabes (Arabs’ House, Oficios #12, tel. 07/861-5868, Tues.-Sat. 9am-4:30pm, Sun. 9am-1pm, free) comprises two Moorish-inspired 17th-century mansions that house a small yet impressive museum dedicated to a Levantine and Islamic theme.

Cobbled Plaza de San Francisco, two blocks south of Plaza de Armas, at Oficios and the foot of Amargura, faces onto Avenida del Puerto. During the 16th century this area was the waterfront. Iberian emigrants disembarked, slaves were unloaded, and galleons were replenished and treasure fleets loaded for the passage to Spain. A market developed on the plaza, which became the focus of the annual Fiesta de San Francisco each October 3, when a gambling fair was established. At its heart is the Fuente de los Leones (Fountain of the Lions) by Giuseppe Gaggini, erected in 1836.

The five-story neoclassical building on the north side is the Lonja del Comercio (Goods Exchange, Amargura #2, esq. Oficios, tel. 07/866-9588, Mon.-Sat. 9am-6pm), dating from 1907, when it was built as a center for commodities trading. Restored, it houses offices of international corporations, news bureaus, and tour companies. The dome is crowned by a bronze figure of the god Mercury.

Behind the Lonja del Comercio, entered by a wrought-iron archway topped by a most-uncommunist fairytale crown, is the Jardín Diana de Gales (Baratillo, esq. Carpinetti, daily 9am-6pm), a park unveiled in 2000 in memory of Diana, Princess of Wales. The three-meter-tall column is by acclaimed Cuban artist Alfredo Sosabravo. There’s also an engraved Welsh slate and stone plaque from Althorp, Diana’s childhood home, donated by the British Embassy.

The garden backs onto the Casa de los Esclavos (Obrapía, esq. Av. del Puerto), a slave-merchant’s home that now serves as the principal office of the city historian.

Dominating the plaza on the south side, the Iglesia y Convento de San Francisco de Asís (Oficios, e/ Amargura y Brasil, tel. 07/862-9683, daily 9am-5:30pm, entrance CUC2, guide CUC1, cameras CUC2, videos CUC10) was completed in 1730 in baroque style with a 40-meter bell tower. The church was eventually proclaimed a basilica, serving as Havana’s main church. It was from here that the processions of the Vía Crucis (Procession of the Cross) departed every Lenten Friday, ending at the Iglesia del Santo Cristo del Buen Vieja. The devout passed down Calle Amargura (Street of Bitterness), where stations of the cross were set up at street corners. After the Protestant English worshiped here in 1762, the Catholic Spanish considered it desecrated and it was never again used for religious purposes.

The main nave, with its towering roof supported by 12 columns, each topped by an apostle, features a trompe l’oeil that extends the perspective of the nave. The sumptuously adorned altars are gone, replaced by a huge crucifix suspended above a grand piano. (The cathedral serves as a concert hall, with classical music performances hosted 6pm Sat. and 11am Sun. Sept.-June.) Aristocrats were buried in the crypt; some skeletons can be seen through clear plastic set into the floor. Climb the campanile (CUC1) for a panoramic view. A side nave contains the Museo de Arte Sacro, featuring religious icons.

A life-size bronze statue (by José Villa Soberón) of an erstwhile and once-renowned tramp known as El Caballero de París (Gentleman of Paris) graces the sidewalk in front of the cathedral entrance. Many Cubans believe that touching his beard will bring good luck.

On the basilica’s north side is Jardín Madre Teresa de Calcuta, a garden dedicated to Mother Teresa. It contains the small Iglesia Ortodoxa Griega, a Greek Orthodox church opened in 2004.

Facing the cathedral, cobbled Calle Oficios is lined with 17th-century colonial buildings that possess a marked Mudejar style, exemplified by their wooden balconies. Many of the buildings have been converted into art galleries, including Galería de Carmen Montilla Tinoco (Oficios #162, tel. 07/866-8768, Mon.-Sat. 9am-5pm, free); only the front of the house remains, but the architects have made creative use of the empty shell. Next door, Estudio Galería Los Oficios (Oficios #166, tel. 07/863-0497, Mon.-Sat. 9:30am-5pm, Sun. 9am-1pm, free) displays works by renowned artist Nelson Domínguez.

Midway down the block, cobbled Calle Brasil extends west about 80 meters to Plaza Vieja. Portions of the original colonial-era aqueduct (the Zanja Real) are exposed. Detour to visit the Aqvarium (Brasil #9, tel. 07/863-9493, Tues.-Sat. 9am-5pm, Sun. 9am-1pm, CUC1, children free), displaying tropical fish. Next door, La Casa Cubana del Perfume (Brasil #13, tel. 07/866-3759, Mon.-Sat. 10am-7pm, Sun. 10am-1pm) displays colonial-era distilleries, has aromatherapy demos, and sells handmade perfumes made on-site.

Back on Oficios, the former Casa de Don Lorenzo Montalvo houses a convent and the Hostal Convento de Santa Brígida. To its side, the Coche Presidencial Mambí railway carriage (Mon.-Fri. 8:30am-4:45pm, CUC1) stands on rails at Oficios and Churruca. It served as the official presidential carriage of five presidents, beginning in 1902 with Tomás Estrada Palma. Its polished hardwood interior gleams with brass fittings.

The door inset in the wall behind the carriage opens to the Salón Blanco, housing El Genio de Leonardi da Vinci Exhibición Permanente (no tel., Tues.-Sat. 9:30am-4pm, CUC2), dedicated to the Renaissance genius. It displays copies (and contemporary reinterpretations) of his artwork, plus magnificent 3-D models of his inventions—from bicycles, gliders, and helicopters to a diving suit—all labeled in various languages. Da Vinci (1452-1519) died the year of Havana’s founding.

Immediately east of the Coche is the Museo Palacio de Gobierno (Government Palace Museum, Oficios #211, esq. Muralla, tel. 07/863-4358, Tues.-Sat. 9:30am-5pm, Sun. 9:30am-1pm). This 19th-century neoclassical building housed the Cámara de Representantes (Chamber of Representatives) during the early republic. Later it served as the Ministerio de Educación (1929-1960) and, following the Revolution, housed the Poder Popular Municipal (Havana’s local government office). Today it has uniforms, documents, and other items relating to its past use, and the office of the President of the Senate is maintained with period furniture. The interior lobby is striking for its magnificent stained glass skylight.

The Tienda Museo el Reloj (Watch Museum, Oficios, esq. Muralla, tel. 07/864-9515, Mon.-Sat. 10am-7pm, Sun. 10am-1pm) doubles as a watch and clock museum, and a deluxe store selling watches and pens made by Cuervo y Sobrinos, a Swiss-Italian company that began life in Cuba in 1882.

On the southeast side of Oficios and Muralla is Casa Alejandro Von Humboldt (Oficios #254, tel. 07/863-9850, Tues.-Sat. 9am-5pm, Sun. 9am-noon, CUC1), a museum dedicated to the German explorer (1769-1854) who lived here while investigating Cuba in 1800-1801.

The last of the four main squares to be laid out in Habana Vieja, Plaza Vieja (Old Square, bounded by Calles Mercaderes, San Ignacio, Brasil, and Muralla) originally hosted a covered market. It is surrounded by mansions and apartment blocks where, in colonial times, residents looked down on executions and bullfights.

Plaza Vieja at night

In the 20th century the square sank into disrepair. Today it is in the final stages of restoration. Even the white Carrara marble fountain—an exact replica of the original by Italian sculptor Giorgio Massari—has reappeared. Two decades ago, most buildings were squalid tenements; the tenants have since moved out as the buildings metamorphosed into boutiques, restaurants, museums, and luxury apartments for foreign residents.

Various modern sculptures grace the park. At the southeast corner is Viaje Fantástico, by Roberto Fabelo—a bronze figure of a bald, naked woman riding a rooster.

The tallest building is the Edificio Gómez Villa, on the square’s northeast corner. Take the elevator to the top for views over the plaza and to visit the Cámara Oscura (tel. 07/866-4461, daily 9am-5:30pm, CUC2). The optical reflection camera revolves 360 degrees, projecting a real-time picture of Havana at 30 times the magnification onto a two-meter-wide parabola housed in a completely darkened room.

The shaded arcade along the plaza’s east side leads past the Casa de Juan Rico de Mata, today the headquarters of Fototeca (Mercaderes #307, tel. 07/862-2530, fototeca@cubarte.cult.cu, Tues.-Sat. 10am-5pm), the state-run agency that promotes the work of Cuban photographers. It hosts photo exhibitions.

Next door, the Planetario Habana (Mercaderes #309, tel. 07/864-9544, shows Wed.-Sat. 9:30am-5pm, Sun. 9:30am-12:30pm, CUC10 adults, children under 12 free) delights visitors with its high-tech interactive exhibitions on space science and technology. A scale model of the solar system spirals around the sun in the 66-seat theater.

The old Palacio Cueto, on the southeast corner of Plaza Vieja, is a phenomenal piece of Gaudí-esque art nouveau architecture dating from 1906. It awaits restoration as a hotel.

On the southeast corner, the Casa de Marqués de Prado Amero today houses the Museo de Naipes (Museum of Playing Cards, Muralla #101, tel. 07/860-1534, Tues.-Sat. 9:30am-5pm, Sun. 9am-2:30pm, entrance by donation), displaying playing cards through the ages.

The 18th-century Casa de los Condes de Jaruco (House of the Counts of Jaruco, Muralla #107), or “La Casona,” on the southeast corner, was built between 1733 and 1737. It is highlighted by mammoth doors that open into a cavernous courtyard surrounded by lofty archways festooned with hanging vines. Art galleries (Tues.-Sat. 9am-5pm) occupy the downstairs.

On the plaza’s southwest corner, cool off with a chilled beer brewed on-site in the Factoría de Plaza Vieja (San Ignacio #364, tel. 07/866-4453, daily 11am-1am), in the former Casa del Conde de Casa Lombillo. The copper stills are displayed in the main bar, where a 1913 Ford delivery truck now sits amid artworks by such famous Cuban artists as Kcho and Nelson Domínguez. Accessed via a door next to the brewpub is the Taller de Luthiería (tel. 07/801-8339), a workshop run by Habaguanex that repairs string instruments.

The Casa del Conde de San Estéban de Cañongo (San Ignacio #356, tel. 07/868-3561, Mon.-Fri. 9:30am-5:30pm, Sat. 9:30am-1pm) is today a cultural center. Adjoining, on the northwest corner of the plaza, is the Casa de las Hermanas Cárdenas, housing the Centro de Desarollo de Artes Visuales (San Ignacio #352, tel. 07/862-2611, Tues.-Sat. 10am-6pm). The inner courtyard is dominated by an intriguing sculpture by Alfredo Sosabravo. Art education classes are given on the second floor. The top story has an art gallery.

Well worth the side trip is Hotel Raquel (San Ignacio, esq. Amargura, tel. 07/860-8280), one block north of the plaza. This former 1908 bank and warehouse is an architectural jewel with a stunning stained glass atrium ceiling and art nouveau facade. The hotel is themed to honor the city’s former Jewish community.

One block west and one north of the plaza is the Museo Histórico de las Ciencias Naturales Carlos Finlay (Museum of Natural History, Cuba #460, e/ Amargura y Brasil, tel. 07/863-4824, Mon.-Fri. 9am-5pm, Sat. 9am-1pm, CUC2). Dating from 1868 and once the headquarters of the Academy of Medical, Physical, and Natural Sciences, today it contains a pharmaceutical collection and tells the tales of Cuban scientists’ discoveries and innovations. The Cuban scientist Dr. Finlay is honored, of course; it was he who on August 14, 1881, discovered that yellow fever is transmitted by the Aedes aegipti mosquito. The museum also contains, on the third floor, a reconstructed period pharmacy.

Adjoining the museum to the north, the Convento y Iglesia de San Francisco el Nuevo (Cuba, esq. Amargura, tel. 07/861-8490, free) was completed in 1633 for the Augustine friars. It was consecrated anew in 1842, when it was given to the Franciscans, who then rebuilt it in renaissance style in 1847. The church has a marvelous domed altar and nave.

The mostly residential and dilapidated southern half of Habana Vieja, south of Calle Brasil, was the ecclesiastical center of Havana during the colonial era and is studded with churches and convents. This was also Havana’s Jewish quarter.

Southern Habana Vieja is enclosed by Avenida del Puerto, which swings along the harborfront and becomes Avenida San Pedro, then Avenida Leonor Pérez, then Avenida Desamparados as it curves around to Avenida de Bélgica (colloquially called Egido). The waterfront boulevard is overshadowed by warehouses. Here were the old P&O docks where the ships from Miami and Key West used to land and where Pan American World Airways had its terminal when it was still operating the old clipper flying boats.

Egido follows the hollow once occupied by Habana Vieja’s ancient walls. It is a continuation of Monserrate and flows downhill to the harbor. The Puerta de la Tenaza (Egido, esq. Fundición) is the only ancient city gate still standing; a plaque inset in the wall shows a map of the city walls as they once were. About 100 meters south, on Avenida de Puerto, the Monumento Mártires del Vapor La Coubre is made of twisted metal fragments of La Coubre, the French cargo ship that exploded in Havana harbor on March 4, 1960 (the vessel was carrying armaments for the Castro government). The monument honors the seamen who died in the explosion.

Egido’s masterpiece is the Estación Central de Ferrocarril (esq. Arsenal), or Terminal de Trenes, Havana’s railway station. Designed in 1910, it blends Spanish Revival and Italian Renaissance styles and features twin towers displaying the shields of Havana and Cuba (and a clock permanently frozen at 5:20). It is built atop the former Spanish naval shipyard. It closed in 2015 for a long restoration that will incorporate contemporary architecture.

On the station’s north side, the small, shady Parque de los Agrimensores (Park of the Surveyors) features a remnant of the Cortina de la Habana, the old city wall. The park is now populated by steam trains retired from hauling sugarcane; the oldest dates from 1878.

Two blocks north of the park, do not miss the Mercado Agropecuario Egido (e/ Apodaca y Corrales), Havana’s most colorful farmers market. Take (and hold on to) your camera! Head two blocks west, then turn left onto Cárdenas. The two blocks between Misión y Apodaca feature some astounding examples of Gaudi-style art nouveau architecture (especially noteworthy are #103, #107, and #161).

The birthplace of Cuba’s preeminent national hero, Museo Casa Natal de José Martí (Leonor Pérez #314, esq. Av. de Bélgica, tel. 07/861-3778, Tues.-Sat. 9am-5pm, entrance CUC1, guide CUC1, cameras CUC2, videos CUC10) sits one block south of the railway station at the end of a street named after Martí’s mother. The leader of the independence movement was born on January 28, 1853, in this simple house with terra-cotta tile floors. The house displays many of his personal effects, including an escritorio (writing desk) and even a lock of Martí’s hair.

The Iglesia y Convento de Nuestra Señora de Belén (Church and Convent of Our Lady of Bethlehem, Compostela y Luz, tel. 07/860-3150, Mon.-Sat. 10am-4pm, Sun. 9am-1pm, free; visits only with a prearranged guide with Agencia San Cristóbal), the city’s largest religious complex, occupies an entire block. The convent, completed in 1718, was built to house the first nuns to arrive in Havana and later served as a refuge for convalescents. In 1842, Spanish authorities ejected the religious order and turned the complex over to the Jesuits, who established a college for the sons of the aristocracy. As the nation’s official weather forecasters, they erected the Observatorio Real (Royal Observatory) atop the tower in 1858; it was in use until 1925. The church and convent are linked to contiguous buildings across the street by an arched walkway—the Arco de Belén (Arch of Bethlehem)—spanning Acosta.

Partially restored, the Iglesia y Convento de Santa Clara de Asís (Convent of Saint Clair of Assisi, Cuba #610, e/ Luz y Sol, tel. 07/761-3335), two blocks east of Belén, is a massive former nunnery completed in 1644. The nuns moved out in 1922. It is a remarkable building, with a lobby full of beautiful period pieces. The cloistered courtyard is surrounded by columns. Note the 17th-century fountain of a Samaritan woman, and the beautiful cloister roof carved with geometric designs—a classic alfarje—in the Salón Plenario, a marble-floored hall of imposing stature. Wooden carvings abound. The second cloister contains the so-called Sailor’s House, built by a wealthy ship owner for his daughter, whom he failed to dissuade from a life of asceticism.

The Iglesia Parroquial del Espíritu Santo (Parish Church of the Holy Ghost, Acosta #161, esq. Cuba, tel. 07/862-3410, Mon.-Fri. 8am-noon and 3pm-6pm), two blocks south of Santa Clara de Asís, is Havana’s oldest church, dating from 1638 (the circa-1674 central nave and facade, as well as the circa-1720 Gothic vault, are later additions), when it was a hermitage for the devotions of free blacks. Later, King Charles III granted the right of asylum here to anyone hunted by the authorities.

The church’s many surprises include a gilded, carved wooden pelican in a niche in the baptistry. The sacristy, where parish archives dating back through the 17th century are preserved, boasts an enormous cupboard full of baroque silver staffs and incense holders. Catacombs to the left of the nave are held up by subterranean tree trunks. You can explore the eerie vault that runs under the chapel, with the niches still containing the odd bone. Steps lead up to the bell tower.

Iglesia y Convento de Nuestra Señora de la Merced (Our Lady of Mercy, Cuba #806, esq. Merced, tel. 07/863-8873, daily 8am-noon and 3pm-6pm) is Havana’s most impressive church, thanks to its ornate interior multiple dome paintings and walls entirely painted in early-20th-century religious frescoes. The church, begun in 1755, has strong Afro-Cuban connections (the Virgin of Mercy is also Obatalá, goddess of earth and purity), drawing devotees of Santería. Each September 24, scores of worshippers cram in for the Virgen de la Merced’s feast day. More modest celebrations are held on the 24th of every other month.

Boxing fans might nip across the street to Gimnasio Rafael Trejo (Cuba #815, tel. 07/862-0266, Fri. 7pm), where young boxers train in a tumbledown open-air facility.

The 100-meter-long Alameda de Paula promenade runs alongside the waterfront boulevard between Luz and Leonor Pérez. Lined with marble and iron street lamps, the promenade is the midst of a two-decades-long remodeling project. In 2016, it gained a new ferry terminal and statues.

The raised central median that is the Alameda proper begins on the south side of Parque Aracelio Iglesias (Av. del Puerto y Luz), where passengers alight ferries at Emboque de Luz terminal. Two blocks south at Calle Jesús María stands a carved column with a fountain at its base, erected in 1847 in homage to the Spanish navy. It bears an unlikely Irish name: Columna O’Donnell, for the Capitán-General of Cuba, Leopoldo O’Donnell, who dedicated the monument. It is covered in relief work on a military theme and crowned by a lion with the arms of Spain in its claws.

At the southern end of the Alameda, Iglesia de San Francisco de Paula (San Ignacio y Leonor Pérez, tel. 07/860-4210, daily 9am-5pm) highlights the circular Plazuela de Paula. The quaint, restored church features marvelous artworks including stained glass pieces. It is used for baroque and chamber concerts. To its east, occupying a waterfront wharf, is the Antiguo Almacén de Madera y el Tabaco (daily noon-midnight), a beer hall with an on-site brewery.

A stone’s throw south, the Centro Cultural Almacenes de San José (Av. Desamparados at San Ignacio, tel. 07/864-7793, daily 10am-6pm), or Feria de la Artesanía—the city’s main arts and crafts market—also occupies a former waterfront warehouse. Several antique steam trains sit on rails outside. Immediately to the south is the Museo de Automóviles (Automobile Museum, Desemparados esq. Damas, tel. 07/863-9942, automovil@bp.patrimonio.ohc.cu, Tues.-Sat. 9:30am-5pm, Sun. 9am-1pm, entrance CUC1.50, cameras CUC2, videos CUC10), displaying an eclectic range of 30 antique automobiles—from a 1905 Cadillac to singer Benny More’s 1953 MGA and revolutionary leader Camilo Cienfuegos’s 1959 mint Oldsmobile. Classic Harley-Davidson motorcycles are also exhibited.

Two blocks north of Luz is the Fundación Destilería Havana Club, or Museo del Ron (Museum of Rum, Av. San Pedro #262, e/ Muralla y Sol, tel. 07/861-8051, daily 9:30am-5:30pm, CUC7 including guide and drink). Occupying the former colonial mansion of the Conde de la Mortera, it’s a must-see introduction to the manufacture of Cuban rum. Tours begin with an audiovisual presentation and include exhibits such as a mini-cooperage, pailes (sugar boiling pots), wooden trapiches (sugarcane presses), salas dedicated to an exposition on sugarcane, and the colonial sugar mills where the cane was pressed and the liquid processed. An operating production unit replete with bubbling vats and copper demonstrates the process. The highlight is a model of an early-20th-century sugar plantation at 1:22.5 scale, complete with working steam locomotives.

Hemingway once favored Dos Hermanos (Av. San Pedro #304, esq. Sol, tel. 07/861-3514), a simple bar immediately south of the museum.

Immediately south of Dos Hermanos bar is the beautiful, gleaming white Sacra Catedral Ortodoxa Rusa (Russian Orthodox Cathedral, Av. del Puerto and Calle San Pedro, daily 9am-5:45pm), a 21st-century construction. Officially called the Iglesia Virgen de María de Kazan, it whisks you allegorically to Moscow with its bulbous, golden minarets. No photos are allowed inside, where a gold altar and chandeliers hang above gray marble floors.

Sacra Catedral Ortodoxa Rusa

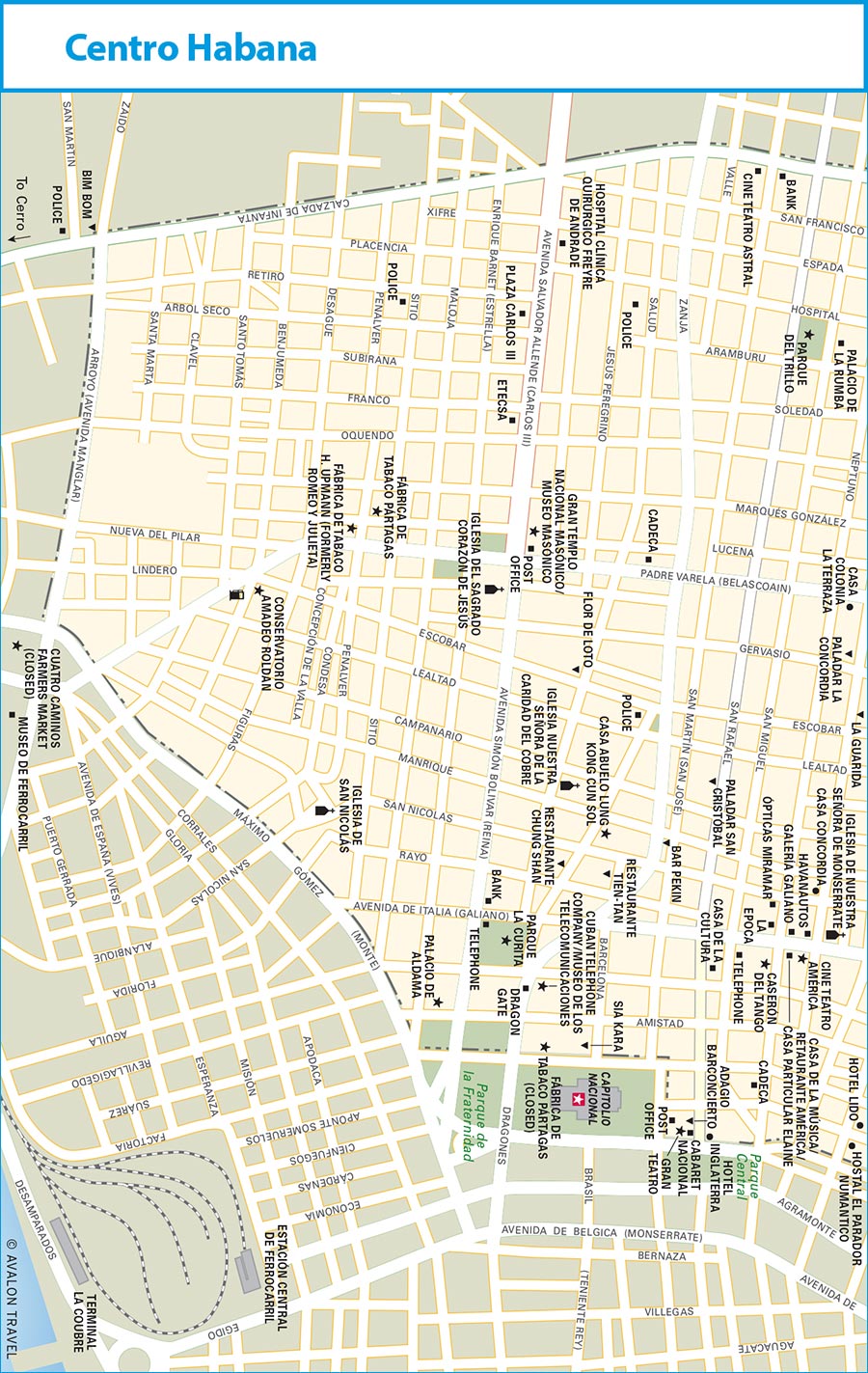

Laid out in a near-perfect grid, mostly residential Centro Habana (Central Havana, pop. 175,000) lies west of the Paseo de Martí and south of the Malecón. The region evolved following demolition of the city walls in 1863. Prior, it had served as a glacis. The buildings are deep and tall, of four or five stories, built mostly as apartment units. Many houses are in a tumbledown state, and barely a month goes by without at least one building collapse.

The major west-east thoroughfares are the Malecón to the north and Zanja and Avenida Salvador Allende through the center, plus Calles Neptuno and San Rafael between the Malecón and Zanja. Three major thoroughfares run perpendicular, north-south: Calzada de Infanta, forming the western boundary; Padre Varela, down the center; and Avenida de Italia (Galiano), farther east.

In prerevolutionary days, Centro Habana hosted Havana’s red-light district, and prostitutes roamed such streets as the ill-named Calle Virtudes (Virtues). Neptuno and San Rafael formed the retail heart of the city. The famous department stores of prerevolutionary days still bear neon signs promoting U.S. brand names from yesteryear.

Caution is required, as snatch-and-grabs and muggings are common.

Officially known as Avenida Antonio Maceo, and more properly the Muro de Malecón (literally “embankment,” or “seawall”), Havana’s seafront boulevard winds dramatically along the Atlantic shoreline between the Castillo de San Salvador de la Punta and the Río Almendares. The six-lane seafront boulevard was designed as a jetty wall in 1857 by Cuban engineer Francisco de Albear but not laid out until 1902, by U.S. governor General Leonard Wood. It took 50 years to reach the Río Almendares, almost five miles to the west.

The Malecón is lined with once-glorious high-rise houses, each exuberantly distinct from the next. Unprotected by seaworthy paint, they have proven incapable of withstanding the salt spray that crashes over the seawall. Many buildings have already collapsed, and an ongoing restoration has made little headway against the elements.

All along the shore are the worn remains of square baths—known as the “Elysian Fields”—hewn from the rocks below the seawall, originally with separate areas for men, women, and blacks. These Baños del Mar preceded construction of the Malecón. Each is about four meters square and two meters deep, with rock steps for access and a couple of portholes through which the waves wash in and out.

The Malecón offers a microcosm of Havana life: the elderly walking their dogs; the shiftless selling cigars and cheap sex to tourists; the young passing rum among friends; fishers tending their lines and casting off on giant inner tubes (neumáticos); and always, scores of couples courting and necking. The Malecón is known as “Havana’s sofa” and acts, wrote Claudia Lightfoot, as “the city’s drawing room, office, study, and often bedroom.”

Every October 26, schoolchildren throw flowers over the seawall in memory of revolutionary leader Camilo Cienfuegos, killed in an air crash on that day in 1959.

The most intriguing site is Primavera (esq. Galiano), a fantastical bronze bust by sculptor Rafael San Juan. A tribute to Cuban women, with mariopas (the national flower) for hair, it went up for the 2015 Havana Biennial.