Chapter 1

THE ORIGINS AND THEORY OF CHINESE MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE

According to legend, sometime between 2697 and 2597 B.C. the renowned first Yellow Emperor, Huangdi, otherwise known as Shen-nong or “King of farming,” tasted one hundred wild herbs and grasses.1 He was trying to ascertain their values as cures to various ailments from which he was presumably suffering. As a consequence, the Yellow Emperor is credited as being the first person in China to institute the art of healing.

For the following two thousand years people continued to test herbs, fruits, fungi, and barks on themselves, as well as on some unfortunate patients, and to record the results. Gradually this hit-ormiss approach—tempered, we would hope, by the observation of animals’ eating habits and by some sort of primitive ideas about physiology and illness—led to the development of a comprehensive theory of health, disease, and treatment.2 Inevitably, medical theory was made to fit into contemporary beliefs about the nature of the world. These beliefs have come down to us under the name Taoism—pronounced dow-izm—meaning “the Way.”

By the so-called Warring States period (475–221 B.C.), Taoist medical theory was sufficiently developed to warrant the systematic compilation of all the then-known facts about human anatomy and physiology, and disease pathology, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. The compilers of the first such record appear to have been various medics working as a group. Either because they were following the fashion of the times (attributing everything to ancient origins), playing modest, or seeking some sort of legitimacy for wild new theories, the authors called their book Huangdi’s (the Yellow Emperor’s) Internal Classic (Huangdi Nei Jing). They wrote it as if it were a dialogue between the Yellow Emperor and his chief counselor, Qi Bo. Whatever the origin and true antiquity of the ideas presented by them, the authors of Huangdi’s Internal Classic laid the foundation for Chinese medical theory and practice a foundation that is valid to this day.

The Huangdi Nei Jing is divided into two parts. The first part, Su Wen (Plain Questions), considers human anatomy, physiology, and pathology within the Taoist theory of yin and yang and the Five Elements. The remedies it espouses are principally herbal. It is on the basis of the Plain Questions that all subsequent medical theory was founded.

The second part is called Ling Shu, or Miraculous Pivot. It discusses the anatomical theory of vital energy (qi) channels within the body and regulation of the circulating qi and the Five Elements by means of acupuncture.

THE TAOIST THEORY OF YIN AND YANG

Figure 1: Energy of the moon and energy of the sun, signifying Yin and Yang

Taoism is a theory of the equilibrium of all nature. Based on early animism and formalized in approximately 500 B.C. by the writings of Lao Tzu (Old Sage), and subsequently by those of Zhuang Zi (Chuang-Tzu), Taoism envisages a world in which the ideal condition is harmony—a perfect balance between human beings and the environment, and among human beings themselves.3 Taoism emphasizes relationships between opposites, aiming toward the perfection of equilibrium. The equilibrium itself is never permanent. Life is an ongoing process of give and take, of energy absorption and energy loss. As a consequence, every living process in nature is characterized by conflict, accommodation, and complementarity. Today we call this homeostasis.

The fundamental forces of the Taoist world are named Yin and Yang. Yin means “in the shade;” Yang translates as “in the sunlight.” Extrapolating from this basic concept Yin and Yang came to mean, repectively, darkness and light, moon and sun, passivity and activity, female and male, cold and heat, inside and outside, down and up, left and right, negative and positive, substance and function, emptiness and fullness, hidden and exposed.

Just as the natural world is characterized by the antagonism and flow of Yin and Yang, so is the human body. Indeed, Taoism would find no reason to differentiate between the natural world and that of human experience. To the Taoist, dualism was the greatest error. Instead, Taoist philosophy suggests that we are an integral part of the whole, a flux and flow of vital energy within a larger energy. Today we would call this holism.

Thus, when the authors of Huangdi’s Internal Classic set out to study human physiology, they based their concept of health on the equilibrium of Yin and Yang. In chapter 5 of the Su Wen (Plain Questions) they wrote: “Yin and Yang are the law of Heaven and Earth, the outline of everything, the parents of change, the origin of birth and destruction.”

The active and dynamic processes of the human body—such as eating, digesting, and metabolizing—they called Yang. The passive functions—such as breathing and blood circulation—are seen as Yin. Diseases were also differentiated between Yin and Yang. Diseases that affect the bodily functions, are virulent in nature, and progress rapidly within the body or ascend from the viscera to the head are considered to be Yang. Those that are organic, lie dormant, are degenerative, are characterized by low activity, or descend from the upper part of the body are Yin. The herbs taken to cure these diseases are, in their turn, also differentiated between Yin and Yang.

Yin and Yang in human health, as in all of nature, are both interdependent and mutually restricting. They rely on each other for their own being. Each contains within it the seed of the other. Where one increases the other decreases; when one reaches its peak the other emerges. These concepts are expressed in pictorial form by the well-known symbol of Yin and Yang’s circular complementarity.

Figure 2: The symbol of Yang and Yin. The upper function, Yang, is in the light and is therefore white. The lower function, Yin, represents the shade and darkness. Yet, as symbolized by the dots within each form, Yang and Yin each contains within itself the seed of its opposite; each is born from the other. When one increases the other decreases.

The Yin and Yang aspects within a living body are in constant interaction, and one always increases at the expense of the other. Activity is Yang; nutrient substances are, in general, Yin. Thus any activity—running, walking, talking—that consumes energy from digested nutrients lessens Yin and, as a result, increases Yang. On the other hand, the metabolism of those same nutrient substances (Yin) depletes the functional energy (Yang) and consequently increases Yin at the expense of Yang. In ordinary circumstances the mutual depletion and increase of Yin and Yang balances itself out. Unusual circumstances—too much activity, too much food, impaired metabolism, or too little activity or food—create an imbalance. In the long term, the imbalance can lead to disease.

Yet Yin and Yang do not exert their influence purely as vital functions. They are, according to Chinese medical theory, attributes of parts of the body as well. Yang is above and Yin is below, therefore the top half of the human body is considered to be Yang and everything below the waist is Yin. Yang is outward and Yin inward. The inside of our body is Yin and the outside Yang. Similarly, the back is Yang and the front Yin, the sides are Yang and the central portion is Yin.

What is true of the body as a whole is also considered valid for the vital organs. In Chinese traditional theory the vital organs are divided, according to their functions, into zang (generating and storing organs) and fu (transforming, transporting, and distributing organs). Generating and storing is considered a Yin activity, therefore the five zang organs (wu zang)—the heart, the liver, the spleen, the lungs, and the kidneys—are all considered Yin. Transforming, transporting, and distributing are said to be Yang activities. It follows, therefore, that the six fu organs (liu fu)—the gall bladder, the stomach, the small intestine, the large intestine, the urinary bladder, and the three main body cavities (san jiao)—are considered Yang.

Because Yin and Yang are everywhere complementary and interdependent, the parts of the human body that are Yang also contain aspects of Yin within themselves, and vice versa. What this means is that within the heart there exists a Yang function too: pumping blood through the body. Yet even within that Yang function of pumping lies a passive Yin function: blood circulation. Within that Yin of circulation can be found the Yang of nutrition to the vital organs. The organs themselves are Yin, which takes us back to where we started from: the heart.

The point is that Yang and Yin are interdependent and complementary to one another. They cannot exist in isolation. Each contains the seed and essence of the other. Within Yang there is Yin, within that Yin another Yang, and so on and so on to infinity.

As the Plain Questions of Huangdi’s Internal Classic puts it: “In any one function, Yin and Yang could amount to ten in number, be extended to one hundred, to one thousand, to ten thousand and even to the infinite.”

All healthy activities of the human body arise from the maintenance of this dynamic equilibrium between Yin and Yang. For example, when the lungs expand and contract they are performing a Yang function, as all activity is Yang. The activity of breathing is based on the substance of the lungs—substance is Yin. Therefore the Yang and the Yin of breathing are interdependent. When one is healthy, the other flourishes; when either one diminishes—through inactivity (improper breathing), malnutrition, or some external factor such as injury or viral disease—the other aspect withers.

The Plain Questions section of Huangdi’s Internal Classic states: “When Yin keeps balance with Yang and both maintain a normal condition of qi (vital energy), then health will be high-spirited. A separation of Yin and Yang will lead to the exhaustion of essential qi.”

The causes of imbalance between Yin and Yang are many and varied. Traditional Chinese medical theory regards external pathogens (xie qi, literally, “incorrect” or “evil energy”) and the state of the body’s resistance to these external pathogens as the major causes of imbalance. Xie qi (pathogens) are seen as external factors. They can arise from climatic aberrations, lack of adaptation to a changed environment, or from the “six excesses.” These excesses are wind (frequently referred to as “evil wind”), cold, heat, firelike heat, dampness, and dryness. Pathogens can also be either Yin or Yang in nature. A Yang pathogen—too much dry heat for example—will decrease the body’s Yang functions. Because of their interdependence, impairment of a Yang function weakens the generation and development of Yin as well. A so-called heat syndrome results. A Yin pathogen on the other hand will diminish Yin, leading to damage of bodily Yang with a resulting cold syndrome. (As a general rule, Yin excess causes a cold syndrome and Yang excess gives rise to a heat syndrome.)

Therapy will be based on correcting the Yin/Yang imbalance. If excess Yang is the cause of a heat syndrome, it is necessary to nourish the weakened Yin by ingesting cooling Yin foods and herbs. Conversely, when a cold syndrome damages the body’s Yang, Yin becomes preponderant and recourse must be made to hot, Yang foods and medicines. The general principle is thus: Treat Yang diseases with Yin foods and treat Yin disorders with Yang foods.

In order to appreciate the complexities of traditional Chinese food therapy, however, more understanding is called for. In addition to grasping the concept of Yin and Yang imbalances, we need to know something about the Five Elements of nature and their relationships to the five zang and the six fu organs, the concept of qi, and the three causes of disease before delving into the principles of using food and herbal medicines.

THE FIVE ELEMENTS

As we have said, according to Taoism everything in nature is either Yin or Yang. Everything in nature is also seen as being constituted by a combination of the five basic elements. This is similar to medieval European and Indian concepts of the five humors (earth, air, water, fire, and ether), though the elements themselves are different. The five Chinese elements, the wu xing, are Metal (Jin), Wood (Mu), Water (Shui), Fire (Huo), and Earth (Tu).

Just as the mutual restriction and enhancement of Yin and Yang is important to understanding Chinese concepts of health, disease, and corrective therapy, appreciating the complex interdependence between the Five Elements is necessary in order to interpret the relationship between human physiology and pathology and the natural environment. For, despite the name, the concepts behind the Five Elements are more complex than the purely material ones of medieval alchemy.

The elements may be referred to simply as metal, wood, water, fire, and earth, but, in actual fact, they are not seen as mere objects. They are more appropriately regarded as attributes and functions. The Chinese term for them, wu xing, does not mean “elements” at all. Wu means “five” and xing can be translated as “movement” or “that which causes action.” “Metal” therefore represents the properties of strength and firmness, of cleansing and destroying. “Wood” is a shorthand way of expressing the functions of germination, extension, softness, and harmony. “Water” represents cold, dampness, and flowing downward. “Fire” signifies heat and flaring. “Earth” refers to the processes of growing, nourishing, and changing.4

These processes are continuously enhancing, restricting, and subjugating one another in much the same way as Yin and Yang complement and limit one another in all natural phenomena. The relationship between the Elements is a precise one; it exists wherever the Elements themselves induce activity. It exists, therefore, in the changing seasons, in the ebb and flow of climate, in life itself. It also exists within the functions of the human body.

Our internal organs, our organs of sense, our tissues, even our emotional life, all are characterized by specific Elements/ functions. The functions of the heart, for example, are regarded as belonging to the element Fire. Fire is heat and energy, and the heart is regarded as the organ that imparts energy to all the others. Without the Fire-heart, the human body cannot survive. Fire is nourished by Wood; the heart, therefore, is nourished by the principal organ of the Wood element, the liver. As a consequence, the health of the liver is regarded as indispensable to the well-being of the heart. On the other hand, Fire is extinguished by Water. It follows that if the kidneys, whose element is Water, fail to function properly, the heart is affected.

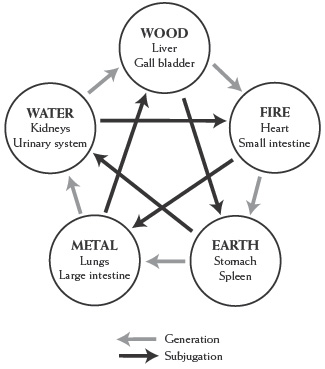

These basic relationships between the Five Elements are described as “generating” and “subjugating.” The order of generation between the Five Elements is this: Wood generates Fire, Fire generates Earth, Earth generates Metal, Metal generates Water, and Water generates Wood. This is frequently referred to as the mother-child relationship. In the control cycle, Water subjugates Fire, Fire subjugates Metal, Metal subjugates Wood, Wood subjugates Earth, and Earth subjugates Water. These basic generating and subjugating relationships are illustrated in figure 3.

Figure 3: Healthy balance between the Elements and their corresponding organs

Through these mutually enhancing and restrictive relationships, a second level of equilibrium is achieved beyond that of Yin and Yang. According to the Lei Jing, a Ming dynasty commentary on Huangdi Nei Jing, “If there is no generation, there is no growth and development. If there is no restriction, then endless growth and development will become harmful.”5 This concept is central to the Chinese theory of good health.

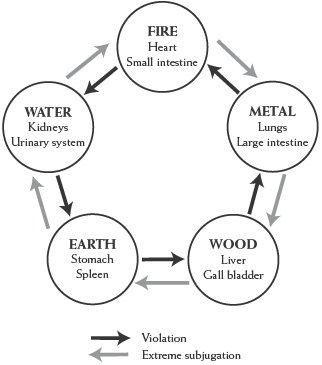

At the level of the Five Elements, illness is characterized by a breakdown of the equilibrium between generation and subjugation. When one of the Elements becomes overactive it tends to break out of its normal generating/subjugating relationships. Strong Fire, for example, will violate Water, consuming it and turning it into steam instead of being quenched by it. At the same time it will subjugate Metal beyond its ordinary capacity, encroaching on it and threatening to destroy it. These pathological relationships are expressed as “violating” and “encroaching” or “subjugating” to the extreme. In disequilibrium situations, including human illness, Fire violates Water and destroys Metal; Water violates Earth and extinguishes Fire; Earth violates Wood and dries up Water; Wood violates Metal and consumes Earth; Metal violates Fire and utterly destroys Wood. These relationships are illustrated in figure 4.

Figure 4: Pathological relationships between the Elements and their corresponding organs

When consulting with a new patient a Chinese physician will observe, ask about symptoms, and test the pulse in order to base his or her diagnosis on the relative forces of Yin and Yang as well as on these primary relationships of generation, subjugation, violation, and extreme subjugation between the Elements and the internal organs. The doctor will, however, also inquire into the patient’s diet and consider the climate, locality, and time of year. No one exists in isolation from the environment; everything about us is charged with the properties of the Five Elements. Therefore the food we eat, the air we breathe, the cli-mate—our entire surroundings—affect us in one way or another. Each of the seasons belongs to a different Element, as does each direction. (In Chinese philosophy there are five of both: spring, summer, late summer, autumn, and winter; north, south, east, west, and center.) It follows, therefore, that the careful doctor must consider all these factors when deciding on the severity of the symptoms and on the appropriate treatment.

What this boils down to, in effect, is that if you are unwell you must first try to understand the relationship between the diseased part of you, your emotions, the time of year, the part of the world you happen to be in, the climate, and what you’ve been eating. If, to take a light-hearted example, your lips erupt with cold sores in New Orleans in the summer where you’ve been singing at Preservation Hall and indulging your sweet tooth, you may be suffering from nothing more complicated than an excess of the Earth element. The Earth—or transforming—Element is abundant in the late summer, in damp climates, in song, and in sweet food. Its excess affects the stomach and the mouth. The remedy would be counteracting Earth with its subjugating element, Wood. In order to achieve that you might move to Boston. More practically, you might eat a diet of greens and cool, sour food, and your troubles would likely disappear. The east, a windy climate, the color green, and sour food are all attributes of the Wood element.

This is, of course, a far-fetched example, but it serves to illustrate the point. The elements in the environment, those within you, and those in your food interact continuously to create situations that can lead either to better health or to debility and disease.

Tables 1 and 2 list characteristics of the various Elements within the human body and in nature. This information can help in diagnosing basic imbalances. The effects of imbalances between the Five Elements within the human body can give rise to many and varied symptoms. For example, a lack of qi (vital energy) in any one organ/function may set off a chain reaction whereby the organ/function normally generated by the weakened organ is depleted of energy and the organ it is supposed to subjugate increases its qi to the point that it stagnates. The outcome is usually malaise and then disease.

Let us look at each of the Five Elements and their five corresponding zang (generating and storing organs) to understand how this happens. (Throughout this discussion you may want to refer back to figure 3 illustrating the generation and subjugation cycles.)

Mu

Mu

“A single tree,” (i.e., Wood)—to germinate

Corresponding zang organ: liver

Organ, tissues, and sense organ affected by Wood: The gall bladder, the tendons, the eyes

In China, to explain the function of Wood it is said that “Trees like to spread their branches freely.” The liver therefore “germinates” vital energy (qi) and spreads it throughout the body. When Wood flourishes it generates Fire by transforming food into qi. The liver Fire feeds the heart, which is itself of the Fire element. The heart Fire then generates the Earth element, which corresponds to the spleen. The Earth element is subjugated by Wood; the liver, therefore, directly inhibits the function of the spleen, as well as contributing to it through heart Fire.

| |||||

| TABLE 1: HUMAN PHYSIOLOGY RELATIVE TO THE FIVE ELEMENTS | |||||

| |||||

| Element: | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

| Attribute: | Germination | Growth | Transformation | Reaping | Storage |

| Bodily organs: | Liver | Heart | Spleen | Lung | Kidney |

| Gall bladder | Small intestine | Stomach | Large intestine | Urinary system | |

| Sense organ: | Eye | Tongue | Mouth | Nose | Ear |

| Tissue: | Tendons | Vessels | Muscles | Skin and hair | Bone |

| Emotion: | Anger | Joy | Worry | Melancholy/grief | Fear |

| Sound: | Shouts | Laughter | Singing | Crying | Mourning |

| Flavor: | Sour | Bitter | Sweet | Pungent | Salty |

| |||||

| |||||

| TABLE 2: NATURAL PHENOMENA RELATIVE TO THE FIVE ELEMENTS | |||||

| |||||

| Element: | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

| Color: | Green | Red | Yellow | White | Black |

| Climate: | Wind | Humid heat | Dampness | Dryness | Cold |

| Direction: | East | South | Center | West | North |

| Voice tones:*1 | Jiao | Zheng | Gong | Shang | Yu |

| Season: | Spring | Summer | Late summer | Autumn | Winter |

| |||||

A weak Wood element leads to a feeble Fire element, resulting in headaches, dizziness, flushed features and, occasionally, mental imbalance. As a consequence, the spleen can become dysfunctional as well.

When the Wood element in the liver is too strong, it results in Fire of the liver. The Metal element is consequently subjugated to the extreme (see figure 3). Metal element resides in the lungs. The lungs are therefore impaired by Fire in the liver, leading to a dry cough and chest pains.

Foods that correct these imbalances would do so by acting directly on the underlying weakness. A dysfunctional liver would be treated by nourishing the weak Wood element. Some Wood-nourishing foods are trout, cheese, and many fruits and berries, such as grapes, lychee, mango, olives, pears, plums, raspberries, strawberries, tangerines, and tomatoes. Sour flavors help Wood to germinate and grow; vinegar, therefore, is ideal for exerting a strengthening influence on Wood. Because of the correspondence between human and animal organs, fresh and healthy animal liver is also considered to be a good remedy for weakness in the liver. Celery, egg yolk, chicken, plums, and peppermint are also valid.

When the Wood element is excessively strong it leads to Fire in the liver and to a consequent stagnation of qi in this organ. The main treatment is to circulate the stagnant qi and to allow the liver to rest; alcohol and heavy and oily foods should therefore be avoided. Because Metal is subjugated to the extreme by Fire in the liver, Metal must be built up in order reestablish equilibrium. The foods that are most suitable for this are the herbs and spices: basil, bay leaf, black and white pepper, capers, cayenne, coriander, dill seed, garlic, ginger, marjoram, mustard greens, nutmeg, rosemary, and peppermint.

Huo

Huo

“A flame generated by the contact of two flint-stones,” (i.e., Fire)—to grow

Corresponding zang organ: heart

Organ, tissues, and sense organ affected by Fire: The small intestine, the blood vessels, the tongue

In traditional Chinese medicine the heart is the governing organ of the body. It is thought to be the seat of the self, of spirit and vitality. As such, the health of the entire mind-body system depends on the health of the heart.

The heart belongs to the Fire element. It is generated by Wood (the liver) and, in turn generates Earth (the spleen and the stomach). On the other hand it is suppressed by Water (the kidneys). When the heart Fire is depleted, through lack of qi from the liver for example, the result is poor digestion and diarrhea (the spleen and stomach depend on heart Fire for health) and low energy in the whole body. When the kidneys fail to function normally the heart is directly affected, resulting in insomnia and emotional problems.

When, on the other hand, the heart Fire burns with excessive heat, the “flames” are said to flare upward, resulting in flushed features, headache, sore throat, bleeding gums, abscesses in the mouth, and bloodshot eyes. Excessive fire also melts Metal (the lung), thus injuring this organ.

Foods that nourish Fire are tangerine, lettuce, papaya, pumpkin, scallion, and rye. Being the flavor associated with Fire, bitter foods also strengthen Fire. The organs that correspond to Fire are the heart and the small intestine; any food that strengthens these will, as a consequence, affect Fire. Some heart-nourishing foods are mung bean, egg yolk, ginseng, licorice, longans, persimmon, and red and cayenne pepper.

Excessive Fire (or inflammation) leads to indigestion, constipation, and the stagnation of blood. This condition may be tempered by strengthening Water, the element that subjugates Fire. Suitable foods to this end are water chestnut, banana, and tangerine peel. Drinking plenty of water is also useful.

Tu

Tu

“Two layers of soil from which a plant grows,” (i.e., Earth)—to transform

Corresponding zang organ: spleen

Organ, tissues, and sense organ affected by Earth: The stomach, the muscles, the mouth

Earth (the spleen) is generated by Fire and regulated by Wood (the liver). The function of the Earth element is to transform; the spleen is therefore involved in the digestion and assimilation of food and in the subsequent storing and distribution of nutrients. It generates Metal (the lungs) and subjugates Water (the kidneys).

The Earth element thrives in warm, dry environments and suffers in cold and damp ones. When the spleen is weak it fails to control normal water metabolism, resulting in urinary problems and, frequently, in diarrhea.

Sweet foods correspond to the Earth and therefore nourish this element. Since sweet is the most common flavor, Earth and spleen-nourishing foods are plentiful. They include most ripe fruits, nuts, and vegetables, as well as seafood, meats, tofu, beans, potatoes, rice, and, of course, honey and sugar. Sour foods are detrimental to a weakened Earth because they nourish Wood and can thus subjugate Earth. In terms of the corresponding organs, a dysfunction of the liver (Wood) will give rise to a pathological condition in the spleen and stomach (Earth).

If you suffer from urinary problems caused by weak Earth, you should eat plenty of sweet foods. All ripe fruits exert a positive effect, but watermelon is perhaps the ideal; besides nourishing Earth with its sweetness, its high water content serves to flush out toxins and clear the urinary passage.

Jin

Jin

“Two gold nuggets hidden in the earth,” (i.e., Metal)—to reap

Corresponding zang organ: lungs

Organ, tissues, and sense organ affected by Metal: The large intestine, the skin and hair, the nose

The lungs and the large intestine both correspond to the Metal element. The main function of the lungs is in respiration—absorbing qi, the vital energy of air, and circulating it throughout the body.

From the Five Elements point of view, Metal generates Water and subjugates Wood. The lungs, therefore, contribute to normal water metabolism and regulate the functions of the kidneys. When the lungs are diseased, the kidneys (Water) are directly affected. In China it is said that “a muffled gong does not sound,” a reference to the fact that when Metal is attacked by external pathogens, the lungs suffer and hoarseness or low voice ensues.

Because of the correspondence between Metal, the lungs and large intestine, and the pungent flavor, any disease that weakens the lungs or intestines may be treated with pungent—Metal element—foods. These include pumpkin, leek, rosemary, fennel, and red and black pepper. However, since Metal is generated by Earth, eating sweet Earth foods will also nourish the lungs and large intestine: white mushrooms, grapes, and persimmon, for example, are sweet in flavor and generate fluids that lubricate the lungs. Other favored foods for treating the lungs are carrot and radish, basil, licorice, cinnamon twig, garlic, ginger, peppermint, scallion, mustard leaf, olive, peanut, walnut, water chestnut, and tangerine.

The large intestine is also favorably affected by consuming tofu and other soybean products, figs, spinach, lettuce, Chinese cabbage, freshwater fish, maize, cucumber, eggplant, nutmeg, and black and white pepper.

Shui

Shui

“Liquid flowing downward,” (i.e., Water)—to store

Corresponding zang organ: kidneys

Organs, tissues, and sense organ affected by Water: The urinary system, the bones, the ear

The kidneys correspond to Water. Water tends to flow downward, thus exerting influence on the lower (Yin) half of the body. It is therefore believed that sexual debility in both sexes is directly attributable to weakness of the kidneys.

Water generates Wood and subjugates Fire. When Water fails to provide Wood with sufficient nourishment, the liver suffers. As we have seen the liver generates Fire, which maintains a healthy heart. Weak Water energy therefore affects both the distribution of vital energy throughout the body and the proper functioning of the heart. The resulting symptoms are pain in the lumbar region, digestive problems, wind, diarrhea, swelling of the feet and legs, irritability, and insomnia.

Drinking large quantities of water is not the solution, nor is the intake of a lot of salt, despite the fact that salty flavor corresponds to Water. To nourish the kidneys, seeds and nuts such as sesame, caraway, dill seed, fennel, star anise, soybean, walnut, chestnut, and lotus seed may be eaten. Other nourishing foods for the kidneys are freshwater fish, cuttlefish, eel, egg yolk, mutton, pork, and wheat products.

Because of its flowing nature, Water is particularly sensitive to imbalances in all the Elements and organs. If a weak Earth fails to control Water, normal Water metabolism is impaired, resulting in diarrhea and edema. Metal, too, must be strengthened so as to properly nourish Water. Bitter foods such as grapefruit, orange, and tangerine peel; bitter gourd; radish leaf; asparagus; and celery exert a positive effect.

For our purposes, the point of this discussion is not to memorize or even pay too studious attention to the precise interactions between the various organs and Elements. It is to remember that whenever we resort to Chinese food or medical therapies, whether for maintaining health or for curing disease, we should consider the mutually regulating interrelationships that exist between all of the Five Elements and their corresponding organs. While this may seem daunting to those readers unschooled in traditional Chinese medicine, it will suffice to bear in mind the simple fact that often, in order to treat a symptom connected with one part of the body, we may have to act on an underlying weakness somewhere else. Or, to put it the way we do in China: You must treat the mother to cure the child.

QI, “VITAL ENERGY”

Yin and Yang and the Five Elements are not material things. They are processes. As such they involve energy in all their functions and interactions. This energy the Taoists call qi, commonly translated as “vital energy” or “essential energy.” Qi involves both function and substance.

Qi is the energy that supports life. It comes into being with life itself and is replenished through food and the inspiration of air. Congenital qi, yuan qi, arouses and promotes the activity of the Five Elements and the organs of the body. Qi from air and food descends through the energy channels of the body to be stored in the center of the body, the dan tian, about four inches below the navel. From the dan tian qi circulates both in the blood and in the conduit channels and collaterals (the meridians of acupuncture theory). Wherever qi goes it nourishes the organs of the body with its life-giving force.

Strong, unobstructed flow of qi ensures life and health; weak qi is generally the precursor of illness. Any organ or part of the body to which the flow of qi is obstructed will weaken, leading to the organ’s withering. As a result, qi stagnates elsewhere in the body and Yin and Yang and the Five Elements become imbalanced. Disease is the inevitable outcome.

Too little or stagnant qi manifests in various ways according to the part of the body being affected. Shallow breathing, for example, indicates lack of qi in the lungs; poor appetite and impaired digestion mean that stomach qi is weak. Hence the importance of maintaining healthy, flowing qi. This is accomplished through diet and through qi gong, or qi control exercises, which we discuss later in the book.

Although unrecognized by allopathy, qi is fundamental to Chinese medical theory. It is the vital force that sustains life and guarantees good health by oxygenating the blood and nourishing the organs and the lymphatic and nervous systems. Without the concept of qi Chinese medicine would be at a loss to explain the workings of acupuncture, the positive effects of the qi gong system of exercises, the benefits of massage and acupressure, even the fundamental questions relating to the nature of health and of life itself.

Qi, therefore, is referred to continuously both in Chinese medical treatises and in popular discussions about life, health, and disease; we too shall consider the qinourishing properties of food throughout this book.

Whether you wish to accept the Chinese belief that qi is something substantial, or instead prefer to interpret it in terms of oxygen and the processes of oxygenation or as another way of talking about energy, it is important to understand that, from the Chinese point of view, nourishing qi, the health of qi, and qi circulation are as important—and perhaps more important—than the nourishment and health of the blood and its circulatory system.

Weakened or stagnant qi is the precursor of disease. Disease itself, however, requires other factors, both internal and external, to take hold of the body. We shall consider these in the following chapter.