Smartphones, tablets and app stores with almost unlimited possibilities have become symbols of the digital revolution. However, while these innovations make our lives more comfortable and interesting, they herald a much more fundamental transformation. Advances in digital technology now affect the way we learn, decide, and interact. By harnessing „Big Data“, the „Internet of Things“, and Artificial Intelligence (AI), we can create smart homes and smart cities. But this is only the tip of the iceberg – our entire economy and society will also dramatically change. What are the opportunities and risks related to this? Are we heading towards digital slavery or freedom? What forces are at work and how can we use them to create a smarter society? This book offers a guided tour through the new, digital age ahead.

After the automation of factories and the creation of self-driving cars, the automation of society is next. While we were busy with our smartphones, the world has secretly changed behind our backs. In fact, our world is changing with increasing speed, and much of that change is being driven by developments in Information and Communications Technology (ICT). These technologies, such as laptop computers, mobile phones, tablets and smart watches, seemed to be about convenience. They came along and enabled us to calculate, communicate and archive with greater speed and efficiency than ever before. However, there was very little recognition that, one day, they would not only facilitate our cultural discourse and institutions, but also reshape our entire world. Large-scale mass surveillance, the global spread of Uber taxis and the BitCoin crypto-currency are just a few of the irritating symptoms of the digital era to come.

1.1 Living in the Age of “Big Data”

Suddenly, there is also a great hype about “Big Data”. No wonder Dan Ariely compared the frenzy about Big Data with teenage sex:

“everyone talks about it, nobody really knows how to do it, everyone thinks everyone else is doing it, so everyone claims they are doing it…”

But some are actually doing it. In fact, “Big Data” has already given rise to many interesting applications, such as real-time language translation. So, what is “Big Data”? The term refers to massive amounts of data, which have been collected about technological, social, economic and environmental systems and activities. To get an idea of “Big Data,” imagine the digital traces that almost all our activities leave, including the data created by our consumption and movement patterns. Every single minute, we produce about 700,000 Google queries and 500,000 Facebook comments. If you add all of the location data of people using smartphones, the consumption data of people who buy things, and cookies which track every click and tap of our online activity, you will begin to comprehend the enormity of “Big Data”.

All the contents collected in the history of humankind until the year 2003 are estimated to amount to five billion gigabytes—the data volume that around 2015 was produced approximately every day. While we have been speaking of an “information age” since the middle of last century, the digital era started only in 2002. Since then, the digital storage capacity has exceeded the analog one. Today, more than 95% of all data are available in digital form. Even by avoiding credit card transactions, social media and digital technologies, it is no longer possible to completely avoid digital footprints on the Internet.

1.2 Data Sets Bigger Than the Largest Library

The availability of Big Data about almost every aspect of our lives, institutions and cultures has fueled the hope that we could now solve the world’s problems. Every Internet purchase we make generates data about our preferences, finances and location that will be stored on a server somewhere and used for various purposes, possibly without our consent. Cell phones disclose where we are, and private messages and conversations are being analyzed. It will probably not be long before every newborn baby is genome-sequenced at birth. Books are being digitized and collated in immense, searchable databases of words that are being data-mined to enable “culturomics”, a field which puts history, society, art and cultural trends under the lens. Aggregated data can be used to reveal unexpected facts in a way that would never have been possible before the digital age. For example, an analysis of Google searches can reveal an impending flu epidemic.

This avalanche of data continues to grow. The introduction of technologies such as Google Glass encourages people to document and archive almost every aspect of their lives. Further data sets include credit-card transactions, communication data, Google Earth imagery, public news, comments and blogs. These data sources have been termed “Big Data” and are creating an increasingly accurate digital picture of our physical and social world, as well as the global economy.

“Big Data” will certainly change our world. The term was coined more than 15 years ago to describe data sets so big that they can no longer be analyzed using standard computational methods. If we are to benefit from Big Data, we must learn to “drill” and “refine” it into useful information and knowledge. This is a significant challenge.

The tremendous increase in the volume of data is attributable to four important technological innovations. First, the Internet enables global communication between electronic devices. Second, the World Wide Web (WWW) has created a network of globally accessible websites, which emerged as a result of the invention of the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). Third, the emergence of social media platforms such as Facebook, Google+, WhatsApp and Twitter has created social communication networks. Finally, a wide range of previously offline devices such as TV sets, fridges, coffee machines, cameras as well as sensors, smart wearable devices (such as activity trackers) and machines are now connected to the Internet, creating the “Internet of Things” (IoT) or “Internet of Everything” (IoE). Meanwhile, the data sets collected by companies such as eBay, Walmart or Facebook, must be measured in petabytes—1 million billion bytes. This amounts to more than 100 times the information stored in the US Library of Congress, which is the largest physical library in the world.

Mining Big Data offers the potential to create new ways to optimize processes, identify interdependencies and make informed decisions. However, Big Data also produces at least four major new challenges (the “four V’s”). First, the unprecedented volume of data means that we need immense processing power and storage capacity to deal with the huge amounts of data. Second, the velocity at which data must be processed has increased: now, continuous data streams must often be analyzed in real-time. Third, Big Data is mostly unstructured, and the resulting variety of data is difficult to organize and analyze. Finally, the veracity of the data may be difficult to handle because Big Data tends to contain errors and is usually neither representative nor complete.

1.3 Will a Digital Revolution Solve Our Problems?

Let us see what an evidence-based approach building on the wealth of today’s data can do for us. In the past, whenever a problem had to be solved, the best course of action was to “ask the experts”. These experts would go to the library, collect up-to-date knowledge, and supervise Ph.D. students who would help to fill gaps in existing knowledge. But this was a slow process. Nowadays, whenever people have a question, they ask Google or consult Wikipedia, for example. This might not always give the definitive or best answer, but it delivers quick answers. On average, decisions taken in this way may even be better than many decisions made in the past. It is no wonder, therefore, that policymakers love the Big Data approach, which seems to provide immediate answers. Business people sensing the immense commercial opportunities are getting excited too.

1.4 Big Data Gold Rush for the Twenty-First Century’s Oil

The fact that we have much more information about our world than ever before is both a blessing and a curse. The accumulation of socio-economic data often implies a long-term intrusion into personal privacy and raises a number of important issues. It cannot be denied that Big Data is a powerful resource that supports evidence-based decision-making and that it holds unprecedented potential for business, politics, science and citizens. Recently, the social media portal WhatsApp was sold to Facebook for $19 billion, when it had 450 million users. This sale price implies that each employee generated almost half a billion dollars in share value.

There is no doubt that Big Data creates tremendous opportunities, not just because of its application in process optimization and marketing, but also because the information itself is becoming monetized. As demonstrated by the virtual currency BitCoin, it is now even possible to turn bits into monetary value. It can be literally said that data can be mined into money in a way that would previously have been considered a fairy tale. For a time, BitCoins were even more valuable than gold.

Therefore, it is no surprise that many experts and technology gurus claim that Big Data is the “oil of the twenty-first century”, a new way of making money—big money. Although many Big Data sets are proprietary, the consultancy company McKinsey recently estimated that the potential value of Open Data alone is $3–5 trillions per year.1 If the worth of this publicly available information were to be evenly distributed among the world’s population, every person on Earth would receive an additional $700 per year. Therefore, the potential of Open Data significantly exceeds the value of the international free trade and service agreements that are currently under secret negotiation.2 Given these numbers, are we currently setting the right political and economic priorities? This is a question we must pay attention to, because it will determine our future.

The potential of Big Data spans every area of social activity, from processing human language and managing financial assets, to empowering cities to balance energy consumption and production. Big Data also holds the promise of enabling us to better protect the environment, to detect and reduce risks, and to discover opportunities that would otherwise have been missed. In the area of personalized medicine, Big Data will probably make it possible to tailor medications to patients in order to increase their effectiveness and reduce their side effects. Big Data will also accelerate the research and development of new drugs and focus resources on the areas of greatest need.

It is clear, therefore, that the potential applications of Big Data are various and rapidly spreading. While it will enable personalized services and products, optimized production and distribution processes, as well as “smart cities”, it will reveal also unexpected links between our activities. But beyond this, where are we heading?

1.5 Will Artificial Intelligence Overtake Us?

Today, an average mobile phone is more powerful than the computers used to send the Apollo rocket to the moon and even the Cray-2 supercomputer thirty years ago, which weighted several tons and had the size of a building. This amazing progress is a result of “Moore’s law”, which posits that computer processing power increases exponentially. But thanks to powerful “machine learning” methods, information systems are becoming more intelligent, too. They do calculations faster than us, they play chess better than us, they remember information longer than us, and they perform more and more tasks that only humans could do in the past. Will they soon be smarter than us? Are the days counted when humans were the “crown of creation”? The famous futurist Ray Kurzweil (*1948), now a director of engineering at Google, was the first to claim that this critical moment (the so-called “singularity”) is near.3

A few years ago, when I read that Artificial Intelligence (AI) might pose a serious threat to humanity, I found this hard to imagine, even ridiculous. However, experts now predict that computers will be able to perform most tasks better than humans in 5–10 years, and reach brain-like functionality within 10–25 years. The AI systems of today are no longer expert systems programmed by computer scientists—they are learning and evolving. To understand the implications, I recommend you to watch some eye-opening videos on deep learning and artificial intelligence.4 These videos demonstrate that most of the activities we earn our money with today (such as reading and listening to language, distinguishing different patterns, and performing routines) can now be done by computers almost as well as by humans, if not better. Jim Spohrer’s perspective on IBM’s cognitive computing products is as follows:5 The first Artificial Intelligence applications will be our tools. As they get smarter, they will become our “partners”, and when they overtake us, they will be our “coaches”.

Will algorithms, computers, or robots be our bosses in a few decades from now? The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has started to study such scenarios.6 It is extremely important therefore to realize that the digital revolution is not just about more powerful computers, better smartphones or fancier gadgets. The digital revolution will change all our personal lives, and it will transform entire economies and societies. In fact, in the coming two or three decades we will see some dramatic changes. A lot of production and services will become automated, and this will fundamentally change the way we work in the future.

Quite soon, within the next two decades or so, less than 50% of people will have jobs for which they have been trained (i.e. agriculture, industry or services).7 Even highly skilled jobs will be at risk. How will the masses of personal data collected about each of us then be used?

1.6 When Big Data Starts to Steer Our Lives

It may sound far-fetched at first, but we must ask this question: “Will we be remotely controlled by personalized information, or is this happening already?” It is clear that Google and Facebook know very well what we are interested in when they place individually tailored ads that often match our interests and tastes. Google Now is an example of a smart app that tells you what to do, if you have signed up for it. For instance, if there is a traffic jam on the way to your next appointment, Google Now may suggest you to leave 15 min earlier in order to be on time. Similarly, Amazon suggests what we might want to buy, and Trip Advisor suggests what destinations to visit and what hotels to book. Twitter tells us what others think—and what we should perhaps think, too. Facebook suggests whom to be friend with. Apps like OkCupid even suggest whom we might date.

While all these services can certainly be helpful we might ask: what will be the consequences? Will we end up living in a digital “golden cage”—a “filter bubble” as Eli Pariser calls it?8 Will we just execute what our smart devices tell us to do? Modern learning software already corrects us when we make mistakes. Smart wristbands tell us how many more steps we should make today. Eye trackers can discover if we are tired or stressed, and computers can predict when our performance will decrease. In other words, we are increasingly patronized in our decision making by computer programs. Will we soon be incompetent to live on our own? And, are we sliding into a “nanny state”, where we don’t have a say? Has our decision-making, has democracy been “hacked”?

Why should we care? Isn’t it just great that computers do calculations for us more quickly than we can do them ourselves? Isn’t it fantastic that our smartphones help us manage our agendas, and that Google Maps tells us the way to go? Why not ask Apple’s Siri to recommend us a restaurant? I certainly don’t object to any of these functions, but it is important to recognize that this is just the beginning of what is to come. Little by little, our role as self-determined decision-makers is being eroded. The next logical step will be the automation of society. How might this look like?

1.7 The Cybernetic Society

This question brings us to an old concept that goes back to Norbert Wiener (1894–1964)9 who was known as the father of control theory (“cybernetics”). Wiener imagined that our society could be controlled like a huge clockwork, where every company’s and every individual’s activity would be coordinated by a giant plan of how to run a society in an optimal way.

Many decades ago, Russia and other communist countries ran command economies. However, they failed to be competitive, while the capitalist approach based on free entrepreneurship thrived. At that time information systems were much more limited in power and scope than today. This has changed. Now there is a third approach besides communism and capitalism: socio-economic systems that are managed in a data-driven way. In the early 70ies Chile was the first country to attempt a “cybernetic society”.10 It established a control center, which collected the latest production data of major companies every week. This was a truly revolutionary approach, but despite its obvious advantages, the government was unable to stay in power, and Salvador Allende (1908–1973), the president of the country, had a tragic end.11 Nevertheless, the dream of a cybernetic society has not ceased to exist.

Today, both Singapore and China are trying to plan social and economic activities in a top-down way using lots of data, and they enjoy larger growth rates than Western democracies. Therefore, many economic and political leaders raise the question: “Is democracy outdated?” Should we run our societies in a cybernetic way according to a grand plan? Will Big Data allow us to optimize our future?

1.8 Wise Kings and Benevolent Dictators, Fueled by Big Data

Given all the data one can now accumulate, is it conceivable that governments or big companies might try to build “God-like”, almost “omniscient” information systems? Could these systems then make decisions like a “benevolent dictator” or “wise king”? Will they be able to avoid coordination failures and irrationality? Would it even become possible to create the best of all worlds by collecting all data globally and building a digital “crystal ball” to predict the future, as some people have suggested? If this were possible, and given that “knowledge is power”, could a sort of digital “magic wand” be created by a government or company to ensure that the benevolent dictator’s master plan remains on course?

What would it take to build such powerful tools? It would require information systems that knew us so well that they could manipulate our decisions by stimulating us with the right kind of personalized information. As I will show in this book, such systems are actually on their way, or they exist already.

1.9 Do We Need to Sacrifice Our Personal Freedom?

Establishing a cybernetic society has a number of important implications. For example, we would need a lot of personal data. In order to be able to control an entire society, it seems important to understand how we think, what we feel, and what we plan to do. Large amounts of personal data are essential to allow artificially intelligent machines to learn what determines our actions and how to influence them. In fact, while mass surveillance is surprisingly ineffective in fighting terrorism12 and child abuse,13 it seems to be very useful to establish a cybernetic society.

But as with every technology, there are serious drawbacks. We would probably lose some of the most important rights and values that have formed the bedrock of democracies and their judicial systems since the Age of Enlightenment. Secrecy and privacy would be eroded by information technologies, and with this, we would lose our security and human values such as mercy and forgiveness. With the advent of predictive policing and other proactive enforcement measures, we could see a deviation from the “presumption of innocence” principle towards the implementation of an ominous “public interest” policy at the cost of individual rights. Do we therefore need to worry about the fact that the leading Big Data nation has more people per thousand inhabitants in prison than any other country, including Russia and China?14

Illustration of how citizens could be punished for any minor transgression of law, even if it is entirely harmless to society. Note that the traffic authority figured out my foreign address to send me this ticket for going 1 km/h too fast with my car, while I was actually not even the driver (which they didn’t check)….

Can such surveillance-based technology- and data-driven approaches turn a country into a “perfect clockwork”? And given that every country is exposed to global competition, is it just a matter of time until all democracies adopt such approaches? If you think this is far-fetched, it is probably good to recall that several influential decision-makers have recently praised China and Singapore as models for the world.17 Such thinking could soon end freedom and democracy as we know it.18 That is why we must pay attention to this now. Of course, some people might ask why we shouldn’t do it, if this increases the efficiency of our lives and our society? Doesn’t history teach us that society evolves over time? Why should we worry, if companies and governments take care of us?

The crucial question is whether they are doing a good job in satisfying our needs and interests. In view of financial and economic crises, cybercrime, climate change and many other problems, it seems, however, that governments have great difficulties to fulfill this promise. Similarly, if we consider the Silicon Valley as a business-driven vision of society, it also seems far-fetched to claim that everyone there is well taken care of.

1.10 Who Will Rule the World?

There is no doubt that Big Data has the potential to be totalitarian. But, in principle, there is nothing wrong with Big Data, Artificial Intelligence, and cybernetics. The question is only, how to use it? For example, who will rule the world in future: will it be big business, government elites, or Artificial Intelligence? Will citizens and experts be no longer relevant to decision-making processes? If powerful information systems knew the world and each of us, would they vote or take decisions for us? Would they tell us what to do or steer our behavior through personalized information? Or will we instead live in a free and democratic society, in which everyone makes decisions in an autonomous but well-coordinated way, empowered by personal digital assistants?

1.11 Two Scenarios: Coercion or Freedom

Will we need to sacrifice our privacy, freedom, dignity, and informational self-determination for a more efficient governance of our world? We must think about these possibilities now. Due to the important societal, economic, legal and ethical implications, we must take some crucial decisions.19 In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, we have certainly witnessed increasing attempts to control citizen activities, including a massive surveillance of our on-line activities. Does the digital revolution imply that we will lose our human rights? Will we lose our autonomy and merely obey what powerful information systems tell us to do? Will we end up with censorship?

- 1.

create participatory opportunities,

- 2.

support informational self-control,

- 3.

increase distributed design and control elements,

- 4.

add transparency for the sake of trust,

- 5.

reduce information biases and noise,

- 6.

enable user-controlled information filters,

- 7.

support socio-economic diversity,

- 8.

increase interoperability and innovation,

- 9.

build coordination tools,

- 10.

create digital assistants,

- 11.

support collective (“swarm”) intelligence,

- 12.

measure and consider external effects (“externalities”),

- 13.

enable favorable feedback loops,

- 14.

support a fair and multi-dimensional value exchange,

- 15.

increase digital literacy and awareness.

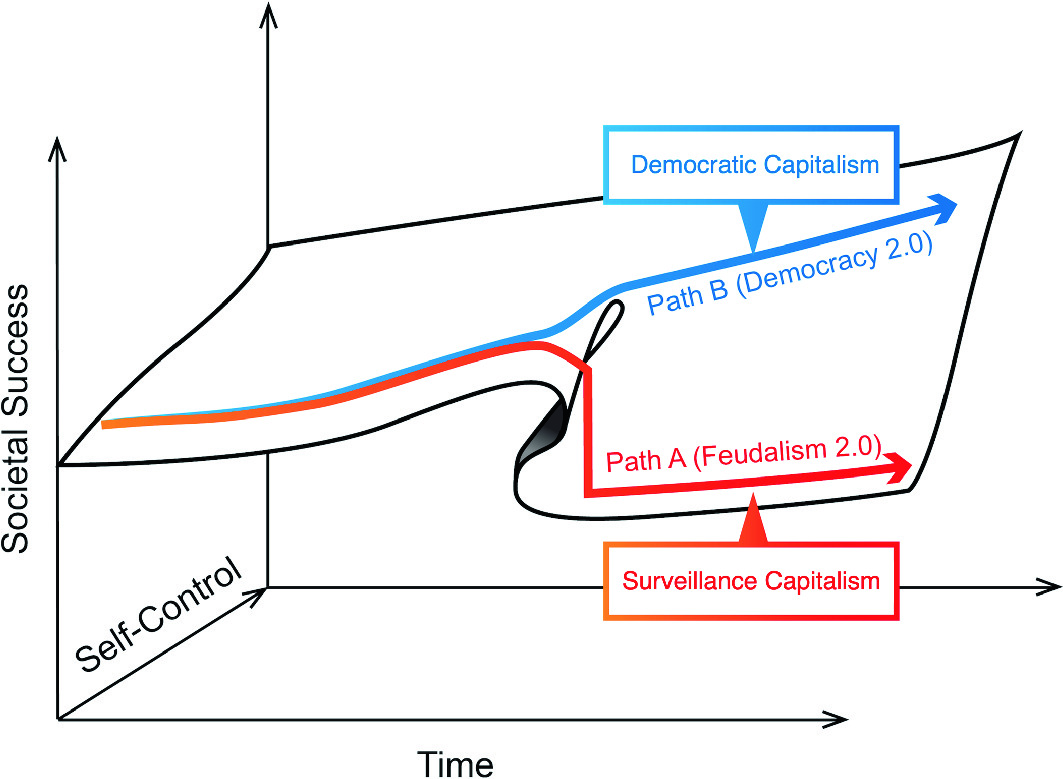

Schematic illustration of two evolutionary paths, leading to two different types of a digital society. Path A would undermine individual freedoms, democracy, and jobs for most of us. Path B corresponds to a society based on self-control and participatory information systems supporting creative and innovative activities of everyone. Which one will we choose?

In this book, I am trying to offer concepts and ideas that can contribute to a smarter and more resilient digital society. Such a framework is needed, because in many important respects, the world has become quite unpredictable and unstable. This is partially due to the increasing level of interdependency of our systems, often driven by advances in Information and Communication Technology. Therefore, which approach will be superior in a world characterized by too much data, too much speed, and too much connectivity? Will it be top-down governance or bottom-up participation? Or would it be better to combine both approaches? And how would we do this?20 We will see that this mainly depends on the complexity of the systems surrounding us.

1.12 A Better Future Ahead of Us

Despite the many challenges, I am still optimistic about our long-term future on the whole. We have already managed societal transitions several times in human history and I am sure we can manage this one, too.

In the following chapters I hope to make a contribution to a necessary public debate, by proposing two main possible societal frameworks for the coming digital age. One of these is based upon the concept of a “big government”, which takes decisions like a “benevolent dictator” or a “wise king”. This framework would be empowered by huge masses of data, something like a digital “crystal ball”. This might be seen as a futuristic version of Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) “Leviathan”. His belief was that social order can not exist without a powerful state, otherwise we would all behave like wild beasts.21

The alternative framework for the digital society is based on the concept of self-organizing systems. This vision relates to the concept of the “invisible hand”, for which Adam Smith (1723–1790) is known. He assumed that the best societal outcomes are reached through self-organization based on market forces. However, financial meltdowns and “tragedies of the commons” such as environmental pollution or harmful climate change22 suggest that the “invisible hand” cannot always be relied on.

But, what if future information and communication technologies would allow us to reach desirable systemic outcomes through decentralized decision-making and self-organization? Can distributed control and coordination mechanisms, empowered by real-time measurements and feedback, make the “invisible hand” work? The feasibility of this exciting vision will be explored in the later chapters of this book, in which I will describe a new paradigm to achieve success and socio-economic order in the twenty-first century. Will this lead us into a new era of creativity, participation, collective intelligence, and well-being?

In fact, examples from the spheres of traffic management and production demonstrate that it is possible to manage complex systems from the bottom-up—and to efficiently produce desirable outcomes in this way. In the following chapters, I will explain the general principle behind such “magic self-organization” and how it could help us to navigate our way through a complex future. I will further explain the role of collective intelligence and how it can help us to cope with the complexity of our globalized world.

Therefore, rather than trying to control or combat the self-organized dynamics of complex systems such as our economy, financial system, global trade, and transportation systems, we could learn to harness their underlying forces to our benefit. Of course, this would involve to locally adapt the interactions of the components of these systems. But if we could achieve this, self-organization could be used to produce desirable outcomes, and this would enable us to create well-ordered, effective, efficient and resilient systems!

Critics might argue that, just because self-organization has been shown to work in complex technological systems (such as traffic control or industrial production lines), this does not necessarily mean that it would also work for socio-economic systems. After all, the behaviors of people can be quite surprising. In the light of this counterargument, we will explore whether and when self-organization can outperform conventional top-down control in managing complex dynamical systems. We will discuss institutional settings and interaction rules that will allow self-organizing systems to be superior. One can now use real-time data to enable adaptive feedback mechanisms, so that systems behave favorably and in a stable way. More specifically, I propose that the “Internet of Things”, with its vast underlying networks of sensors, will make socio-economic self-organization possible in a distributed and bottom-up way. But the crucial question is how to make a data-oriented approach based on distributed control work? The solution, as we will see, requires “complexity science”.

1.13 On the Way to a Smarter Digital Society

In the long run, I am confident about our future, mainly because I believe in the power of ideas in the digital age. However, we must remain alert to the possibility that we could make serious mistakes along the way. The financial system may fail, democracies may—intentionally or accidentally—turn into surveillance societies, or we may end up fighting wars. Therefore, with this book, I am trying to explain the opportunities and risks ahead of us.

Signs of change are everywhere. Information technologies are transforming the global economy at a rapid pace. In essence, we are experiencing nothing less than a “third economic revolution”,23 leading to an “Economy 4.0”. Its effects will be at least as profound as those of the first (agrarian to industrial) and second (industrial to service) revolutions. The ubiquity of digital technologies—such as social media, smart devices, the Internet of Things and Artificial Intelligence—is giving rise to a digital society. We can no longer afford to be passive bystanders of this seismic societal transition. We must prepare for it. But we should not regard these changes merely as a threat to social and global stability. In fact, we are faced with a once-in-a-century opportunity!

For example, the digital revolution is not only changing the way we learn, behave, make decisions and live. It is also altering the way we produce and consume, and our conception of ownership. Information is a very interesting resource in that it is the basis of culture and can be shared as often as we like. To get more of it, we do not have to take it away from others. We don’t have to fight for it. This of course will depend on how our economy is organized in the future. In particular, on how we reward effort for the production of data, information, knowledge and creative digital products. We can either perpetuate the outdated principles of the twentieth century or open the door to a smarter twenty-first century society. Why don’t we do the latter?

Many people are now talking about “smart homes”, “smart factories”, “smart grids”, and “smart cities”. It is logical that we will soon have a “smart economy” and a “smart society”. Networked information systems will enable entirely new solutions to the world’s problems. One thing is therefore clear: the world in the digital age will be very different. But even if we can’t exactly predict what the future will hold, can we at least get a glimpse of it? I believe we can, at least to some extent, and some trends are already emerging. Clearly, the characteristics of the future world will result from the technological, social and evolutionary forces shaping it. The technological drivers include Big Data, the Internet of Things and Artificial Intelligence. The social drivers include the increase of information volumes and networking. In addition, there are evolutionary forces that will lead to new kinds of incentive systems and decision-making. I will attempt to evaluate the implications of these forces, and debate the opportunities and risks they present.

These forces, in turn, are generated by the interactions occurring within our “anthropogenic systems”, i.e. our man-made or human-influenced techno-socio-economic-environmental systems. In order for interventions to be beneficial, we must understand how these interactions—and the forces they are creating—can be harnessed to our advantage in the same way as we have learned to harness the forces of nature.

How will the digital revolution reshape our socio-economic institutions? And what preparations can we make? While addressing these and other questions, I will pursue a non-ideological approach, oriented neither politically left nor right, but carefully exploring novel opportunities. I will try to explain how we can use the digital revolution to make our society more innovative, successful and resilient, through understanding the new logic of the digital era to come. I will discuss how we can adapt our systems in real-time with novel technologies. Furthermore, I will outline how we can build an information and innovation ecosystem that can create new jobs and opportunities for everyone.

We are now ready to dive into the details of why our world is troubled and how we can fix it—by using advanced “information and communication systems” in entirely new ways. The following chapters will focus on subjects such as prediction and control, complexity, self-organization, awareness and coordination, responsible decision-making, real-time measurement and feedback, systems design, innovation, reward systems, co-creation, and collective intelligence. I hope this journey through the opportunities and risks presented by the emerging digital age will be as exciting for you as it is for me!