THANKS TO THE CONQUESTS OF ALEXANDER AND THE HERCULEAN efforts of his Successors, western Asia, north Africa, and the eastern Mediterranean region generally were home for some six hundred years—300 BCE to 300 CE—to the civilization known as Hellenistic. The Greek language was the common language spoken by the educated elites everywhere, from Samarkand to Sardis and from the Crimea to Assuan. Everywhere a person traveled, there were Greek cities where Greek was spoken and a familiar urban environment, with familiar amenities, services, and entertainments, was to be found. For two centuries this civilization was ruled over by Macedonian kings supported by Macedonian armies; then for four more centuries Roman governors ruled and Roman armies provided security, but the urban Hellenistic civilization remained the same throughout. How remarkable a feat it was to unite the very disparate peoples and cultures living from Iran to the Mediterranean and from the Black Sea to the Sudan into one great civilizational sphere with relative peace, order, and security, and a common language and culture superposed over the vast linguistic and cultural diversity, is not well enough acknowledged. It bears investigating what Hellenistic civilization was, and how it was imposed and maintained.

1. THE KINGS

Discussion of the kings of the Hellenistic world begins appropriately by quoting again the definition of kingship found in the Suda and already quoted above in Chapter 4. It clearly derives from an early Hellenistic source, and it neatly sets out the basic qualities expected of Hellenistic kings: competent military leadership and capable administration.

Basileia (kingship): it is not descent or legitimacy which makes a king; it is the ability to lead armies well and handle affairs competently. This is seen by the examples of Philip and of Alexander’s Successors.

The great kings of the kingdoms and dynasties described in the previous chapter stood at the apex of Hellenistic civilization for its first two centuries, until the advent of the Romans. It was no easy thing, being a Hellenistic king: one had to try to live up to the example of giants. Philip, Alexander, and the Successors—Antigonus, Seleucus, Ptolemy and the rest—strode across the imaginations of the people of the Hellenistic world, and the kings who succeeded them inevitably were measured against their achievements. Many of the Hellenistic kings failed this test, perhaps to some degree crushed by the burden of expectation. There were the incompetents, such as Seleucus II who liked to be called “Callinicus” (Glorious Victor) to hide his military failures; the pleasure-lovers, such as Ptolemy IV and Ptolemy VIII, the latter known to his detractors as “Physkon” (Pot-belly) as a result of his excesses; and the utter nonentities, such as Antiochus IX or Ptolemy X, scarcely remembered for anything at all. But there were also competent Hellenistic kings who strove to live up to the examples of the Macedonian founders and the responsibilities of their positions, and even a few who genuinely met the challenge and deserve to be remembered as great, in their own ways. Each of the great dynasties produced at least one, and they represent what the Hellenistic kings could be at their best.

Around the year 522 CE a Byzantine traveler and monk named Cosmas Indicopleustes (Cosmas the India-Voyager) visited the port of Adoulis on the coast of Eritrea in east Africa. There he saw and recorded a remarkable Greek inscription:

King Ptolemy the Great, son of king Ptolemy and queen Arsinoe, the Brother-Sister Gods, who were children of king Ptolemy and queen Berenice the Savior Gods, descended on his father’s side from Heracles son of Zeus and on his mother’s side from Dionysus son of Zeus, having succeeded his father as ruler of Egypt, Libya, Syria, Phoenicia, Cyprus, Lycia, Caria, and the Cycladic islands, marched into Asia with a force of infantry and cavalry, a fleet, and elephants from the Cave-dwellers (Troglodytes) of Ethiopia, which his father and he were the first to hunt from these places and which they brought down to Egypt and trained for use in war. He secured control of all the land this side (i.e. west) of the Euphrates, as well as Cilicia, Pamphylia, Ionia, the Hellespont, and Thrace, and of all the forces in those regions and of the Indian elephants; and having brought under his control all the governors of these regions, he crossed the River Euphrates and subdued Mesopotamia, Babylonia, Susiane, Persis, Media and all the remaining territory as far as Bactria; and he sought out the sacred objects that had been removed from Egypt by the Persians and brought them back to Egypt along with other treasure from these regions; and he sent his forces across the canals … (Austin The Hellenistic World doc. 221 = Dittenberger OGIS no. 54).

20. Gold coin of Ptolemy III Euergetes

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image by Jastrow)

This is the self-representation of Ptolemy III, known as Euergetes (the Benefactor), and it tells a remarkable tale of this energetic and effective king. In the first place, it must be noted that much of what is claimed here is not true: it is essentially certain that Ptolemy III conquered no lands in Asia Minor or east of the Euphrates as here claimed. But that is to a certain degree beside the point. Ptolemy III was a conqueror like his grandfather the first Ptolemy: he did invade Syria as far as the Seleucid capital of Antioch, and add these lands to the Ptolemaic realm for a time. What is of interest here is the nature of the claims made, the reason for them, and what they tell us of Ptolemy and his conception of himself as king. In the first place, he emphasizes descent: he was the third king of his line, after his father Ptolemy Philadelphus and his grandfather Ptolemy Soter. This descent was clearly crucial to him: it made him who he was, a “great king” in his own right. Interestingly he emphasizes his descent in the female line too: he references queen Arsinoe (who was not in fact his biological mother) and his grandmother queen Berenice. Besides this real descent, to emphasize his glorious genealogy, he alleges further descent: his grandfather was descended from Heracles, and his grandmother from Dionysus. It is the first of these fictitious descents that is significant: the claim to descent from Heracles establishes a connection to the old Macedonian royal line of the Argeads, who were supposed to be descended from Heracles. In other words, Ptolemy here claims that his grandfather was some sort of Argead, and that he himself thus descended from the old royal lineage of Macedonia. There is in fact a known story alleging that the first Ptolemy was an illegitimate son of the great Philip, which may be here hinted at.

Next notice the joint exploits of Ptolemy III and his father Ptolemy Philadelphus: together they invaded the land of the “Troglodytes” and were the first to capture and train African elephants there. The Troglodytai or Cave-dwellers of “Ethiopia” were described by Herodotus as a very strange people on the very edge of the known world: “the fastest people of any of whom we have found any report. They eat reptiles such as snakes and lizards, and speak a language different from any other, that sounds like bats screeching” (4.183). It has been suggested that the “bat-like” language refers to the distinctive clicking sounds in the old Khoisan languages of pre-Bantu Africa; and the inhabitants of east Africa are of course famously great runners to this day. Ptolemy is saying that he and his father went beyond the known world, which was the kind of thing done by heroes of Greek myth such as Heracles or Jason and the Argonauts. And in this case the claim is true: Ptolemy III really did penetrate well to the south of Egypt, as the inscription set up in Adulis itself proves, and the Ptolemies (or their hunters) really did capture and train African elephants. Most importantly, note the lands Ptolemy III here claimed to have conquered and the title he gave himself. The lands mentioned, all of Asia from the Hellespont to Bactria, are of course the lands conquered by Alexander; and Ptolemy calls himself “Megas” (the Great), the title given to Alexander alone among previous Greek or Macedonian leaders. Ptolemy III, that is to say, here deliberately and consciously presented himself as a second Alexander, who had conquered the same lands as Alexander had and deserved the same title. To cap the likening of himself to Alexander, there is the claim that he recovered sacred artifacts looted from Egypt by the Persians and returned them to Egypt: Alexander had famously recovered in Persia statues and other sacred objects looted from Athens by the Persians, and returned them to Greece.

The point of these claims, then, is to advertise that Ptolemy Euergetes was not just a descendant of kings, but a worthy one; not just a man who lived up to the examples of his immediate ancestors, but a king who could stand comparison to Alexander “the Great”; not just the heir to the Ptolemaic kingship, but the heir of the Argeads of old. That the claims made are exaggerated did not matter: few who read this, or other inscriptions like it that will doubtless have been set up around his kingdom, will have known enough or cared to quibble. It was that Ptolemy claimed to be and strove to be this kind of king that mattered. He did not take the role of king lightly, he did not give himself over to indulgence: he strove to be a worthy heir to the great rulers of the past, and presented himself as such. And he recognized in doing so that he was a king of Egyptians: Alexander might have returned sacred objects to Greece; Ptolemy here claimed to have restored sacred objects to his own people, the Egyptians. Ptolemy, that is, cultivated the good will of his Egyptian subjects, as well as emphasizing his Greek and Macedonian heritage. And that he won genuine good will by his efforts is attested by another famous inscription, the Canopus decree:

In the reign of Ptolemy the son of Ptolemy and Arsinoe the Brother-Sister Gods, in the ninth year (238 BCE) … [extensive further dating formulas omitted] … it was decreed: the high priests, the prophets, those who enter the holy of holies to dress the gods, the wing bearers, the sacred scribes, and the other priests who have assembled from the whole land … for the birthday and ascension day of the king … held a session on that day in the temple of the Benefactor Gods at Canopus and declared: since king Ptolemy son of Ptolemy and Arsinoe the Brother-Sister Gods, and queen Berenice his sister and wife, the Benefactor Gods, constantly confer many great benefits on the temples throughout the land and increase more and more the honors of the gods, and show constant care for Apis and Mnevis and all the other famous sacred animals in the land at great expense, and since the king from a campaign abroad brought back to Egypt the sacred statues that had been stolen out of the land by the Persians, and restored them to their proper temples from which they had been taken, and since he has maintained the land at peace by fighting in its defense against many nations and rulers, and since they have provided good governance to all those in the land … (Austin The Hellenistic World doc. 222 = Dittenberger OGIS no. 56)

The inscription continues at great length listing the good deeds of Ptolemy and his wife Berenice, praising them, and bestowing honors on them in gratitude. The point is that the priests of the native Egyptian gods acknowledged and honored Ptolemy III as a diligent and effective ruler, and specifically endorsed his claim to have repatriated sacred Egyptian objects. Ptolemy III was, as kings go, a good king who worked at being worthy of the position and earning the good will of his people, both Greek and Egyptian. However exaggerated his own propaganda may have been, it was based in some genuine reality, and reflected his real desire to be seen to be a worthy king.

In the early decades of the twentieth century there lived in the old Hellenistic city of Alexandria, then still a thriving metropolis under British rule, a remarkable Greek man. Outwardly he was nothing to attract much notice: during working hours he held a minor position in the British bureaucracy, fulfilling his duties neither negligently nor with much zeal. But outside working hours this man, Constantinos Cavafy, lived a rich life filled with amorous encounters and with imaginings of the long and glorious past of his people, the Greeks. He was a poet, and a great poet at that; his imagination lingered in the great era of Hellenistic civilization, and in a way he could be called the last Hellenistic poet, living two thousand years out of his true time. In one of his poems, he recreates a scene from the life of a Hellenistic king, the Macedonian ruler Philip V:

He’s lost his former dash, his pluck.

His wearied body, very nearly sick,

will henceforth be his chief concern. The days

that he has left, he’ll spend without a care. Or so says

Philip, at least. Tonight he’ll play at dice.

He has an urge to enjoy himself. Do place

lots of roses on the table. And what if

Antiochus at Magnesia has come to grief?

They say his glorious army lies mostly ruined.

Perhaps they’ve overstated: it can’t all be true.

Let’s hope not. For though they were the enemy, they were kin to us.

Still, one “let’s hope not” is enough. Perhaps too much.

Philip of course won’t postpone the celebration.

However much his life has become one great exhaustion

a boon remains: he hasn’t lost a single memory.

He remembers how they mourned in Syria, the agony

they felt, when Macedonia their motherland was smashed to bits.

Let the feast begin. Slaves: the music, the lights!

(C. P. Cavafy “The Battle of Magnesia” tr. D. Mendelsohn 2009)

Thus the poet imagines the scene when Philip V, Antigonid king of Macedonia, heard of the defeat of his contemporary Antiochus III of the Seleucid Empire at the hands of the Romans. These two kings, who came to the thrones of their respective kingdoms within a year of each other, shared an intertwined fate of near greatness and ultimate fall. In many ways, they were the best of the Hellenistic kings, and yet they had the bad luck to still be ruling when Roman power began to encroach into the Hellenistic world, and both ended their lives in defeat. These ultimate defeats should not detract from the near greatness they showed in their primes.

Philip was the grandson of Antigonus Gonatas, and became king of Macedonia when his cousin and predecessor Antigonus III Doson died unexpectedly in 221. Philip was then about seventeen years old, and ruled for some forty-two years until his own death in 179. Doson had been a very capable king, and had trained Philip well for the role. Philip’s reign falls naturally into two phases, pivoting around the year 197. In the early phase he was something of a military adventurer, trying to emulate Alexander but in truth more closely resembling Demetrius the Besieger’s occasional brilliance but fundamental inconsistency. Philip wanted Macedonia to be a great power again: he fought the Aetolian League in the Social War (220–217); the Romans in the First Macedonian War (216–206); the Ptolemaic Empire in a war (205–201) in which he sought to take over Ptolemaic possession in the Aegean islands and eastern coastal cities; and the Romans again in the Second Macedonian War (200–197). In these wars he displayed considerable military talent and scored some brilliant successes, but also put himself and his forces in positions of great difficulty at times, and suffered some serious setbacks. What remained clear throughout, however, was his desire to be seen as a king worthy of the title, worthy of succeeding to Philip II, Alexander, and Antigonus I, and his desire to keep Macedonia secure and strong. In this latter context, one must also mention repeated campaigning by Philip on Macedonia’s northern borders, keeping the Illyrians, Dardanians, and Thracians at bay as was the duty of every Macedonian king.

21. Coin with portrait of Philip V of Macedonia from British Museum

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image from PHGCOM)

During all these years of military adventuring, Philip made one irreparable mistake: watching events in the west, and the scale of the warfare between the Romans and the Carthaginians there in the Hannibalic War (218–201), Philip decided it would be wise to make friends with the eventual winner; and in 216, after Hannibal’s crushing defeat of the Romans at the Battle of Cannae (216), it looked as if the Carthaginians were going to win. Philip’s alliance with the Carthaginians, forged in that year, brought him into hostilities against the Romans, who of course beat the Carthaginians in the end and never forgot or forgave Philip for joining their enemies at their (the Romans’) lowest point. The first war between Philip and the Romans ended in a stalemate peace in 205; but in the second Philip suffering a crushing defeat at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in Thessaly in 197. This defeat highlighted a problem: the constant warfare of the first twenty years of Philip’s reign had seriously depleted Macedonia’s military manpower. It was only with great difficulty, and by calling up boys as young as sixteen and men over fifty, that Philip was able to muster eighteen thousand Macedonian pikemen and two thousand cavalry to face the Romans (he also had two thousand more men stationed in garrisons in southern Greece and Asia Minor). After his defeat and its heavy losses, Philip managed to call up six thousand five hundred more men from the cities of Macedonia, but his army was in no condition to fight on. He had to sue for peace and accept the conditions the Romans laid down: the loss of Thessaly and all other territories outside the ancestral Macedonian kingdom proper.

Thus began the second and in many ways more impressive phase of Philip’s reign: from 196 until his death in 179 he strove successfully to rebuild the manpower and economic strength of Macedonia, modeling himself more on Philip II and Antigonus Gonatas than on Alexander or Demetrius. By the end of his reign he was able to leave to his successor Perseus an army of over forty thousand men: stronger than Macedonia had been since before the Galatian invasion of 279. How did he achieve this? A hint is given by a letter Philip wrote to the people of Larissa in Thessaly as early as 214:

King Philip to the magistrates and the city of the Larissans, greeting. I have heard that those who had been enrolled as citizens in accord with my letter and your decree and listed in the records have been removed. If this has indeed happened, those who advised you so have mistaken both the advantage of your country and my judgment. That it would be the best of all things if, as many as possible being citizens, the city were strong and the land not left, as now, disgracefully barren, I think not one of you would disagree. It is indeed possible to observe others employing such enfranchisements, among whom are the Romans, who receive into their citizen body even their slaves when they free them and even allow them to share in the magistracies, and by such means have not only strengthened their country but also sent out colonies to some seventy places. So now, then, I urge you to consider the matter impartially, and to restore those who were chosen by the citizens to the citizenship; and if some have done something to the harm of the kingdom or the city or are not worthy for some other reason to be listed, concerning these persons make a postponement until I, when I have returned from my present campaign, shall hold a hearing … (Austin The Hellenistic World doc. 60 = Dittenberger Syll. no. 543).

We see here king Philip striving to strengthen the cities of his kingdom (in this case Larissa in Thessaly), by adding new citizens to keep the cities strong and their land cultivated. He showed the same concern during the remainder of his reign, strengthening the cities of Macedonia by bringing in new settlers, often from Thrace or even Illyria, thereby rebuilding the population of Macedonia and strengthening its economic base by bringing more land under cultivation and re-opening mines that had fallen into disuse. He was in sum a king who took the business of ruling seriously, both as a commander and as an administrator, following in this the examples laid down—as already noted—by his grandfather Antigonus Gonatas and above all by his namesake, the great Philip II.

When Philip came to the throne in 221, his close contemporary Antiochus III had already been ruling for over a year, having succeeded his older brother Seleucus III as king in 223. He found the Seleucid kingdom at a low ebb: his father Seleucus II had been a weak and ineffective king, and his older brother Seleucus III had been assassinated within a couple of years of succeeding to the kingship. In the east, the Parthians and the Greek colonists in Bactria pursued largely independent policies, and the Median governor Molon was seeking to establish his own power. In the west, in Asia Minor, local dynasts like the Attalids of Pergamon, the Ziaelids of Bithynia, and the Mithridatids of Pontus were building their own kingdoms, and the local representative of Seleucid power—Antiochus’ cousin Achaeus—was aiming at the kingship for himself. The Seleucid Empire seemed headed for collapse. Over the course of rather more than twenty-five years of campaigning, Antiochus III rebuilt the empire, reconquering the east as far as the borders of India, and Asia Minor as far as the Hellespont, and in 201 even succeeding in taking Palestine from the Ptolemies and adding it to the Seleucid realm. In doing all of this, Antiochus III won for himself the epithet “Megas” (the Great) and a reputation as a second Alexander, having campaigned and won victories throughout the lands that Alexander had conquered. At the height of his power, in 196, the Seleucid Empire was as extensive as it had been under its founder Seleucus I, and it seemed stronger than ever. Had he died in 196 or 195, Antiochus the Great would be remembered as a glorious ruler, the most successful Seleucid ruler without caveat.

22. Portrait bust of Antiochus III “the Great”

(Author’s photo, taken at Metropolitan Museum, NY)

Not all of this was achieved by pure campaigning and military force, though Antiochus was clearly an excellent commander and leader of men. To hold lands he had campaigned in, he needed effective administrative arrangements, calling for organizational skills. We are fortunate to possess numerous documents surviving in inscriptions that show his interactions with key subordinates, with Greek cities, and with native communities. He emerges from them as a careful and thoughtful ruler of his realm and its various peoples, recognizing that the strength of the realm depends on the wellbeing of its people. One such document, which I quote here, is not in an inscription but in a literary source—the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus—and is of particular interest since it deals with a non-Greek population group and shows the king’s interest in their contribution to his kingdom, and in making them happy to serve the realm.

King Antiochus to Zeuxis his “father” (honorific term for senior trusted subordinate), greeting. If you are well, that is good. I myself am also well. Hearing that people in Lydia and Phrygia are rebelling, I thought that this required careful attention on my part and, having consulted with my “friends” (that is, high officials) about what should be done, I decided to transfer two thousand households of Jews from Mesopotamia and Babylonia together with their possessions into the forts and the most strategic places. I am sure that they will be loyal guardians of our interests because of their piety towards god, and I know that evidence of their trustworthiness and zeal for what is requested of them has been given to my ancestors. I desire, therefore, although it is difficult, that they may be transferred with the promise that they shall use their own laws. And when you bring them to the places mentioned, you shall give to each of them a plot on which to build his house and land for farming and the growing of vines, and you shall grant them exemption from the tax on the produce of the soil for ten years. In addition, until they harvest crops from the land, let there be measured out for them grain to sustain their servants. Let there also be given enough for those performing military service in order that, meeting with kindness from us, they might also be more zealous for our interests. Take care also for this nation in so far as possible in order that it be disturbed by no one (Josephus Jewish Antiquities 12.148–53).

What we see is a king who followed the example of his ancestor Seleucus, and of Seleucus’ mentors Philip II and Antigonus the One-Eyed, in building up his realm by creating settlements, establishing prosperity in such settlements, and so securing both the good of his people and his own strength. Like Philip V, Antiochus eventually made the mistake of provoking the Romans, leading to a Roman invasion of Asia Minor in 190 and a devastating defeat for Antiochus in the Battle of Magnesia late in that year. To win peace with the Romans, Antiochus had to surrender control of all the Seleucid lands in Asia Minor, and he died an embittered and disappointed king a few years later. His sons, Seleucus IV and Antiochus IV, managed to maintain and even rebuild Seleucid power somewhat, but after the death of Antiochus IV the kingdom fell into repeated civil wars and decline, until the final Roman takeover in the sixties BCE. As a result, Antiochus III is, like Philip V, mainly remembered for his defeat by the Romans. But he was a strong and successful king until that fateful conflict.

What we see with all three of the kings highlighted here, and with the other successful kings of the three dynasties—kings such as Ptolemy II, Antigonus Doson, Antiochus I, and Antiochus IV—is that they did not see the kingship as some sort of privilege allowing its holder to do as he liked and pursue pleasure, but as a serious duty requiring hard work and some degree of self-sacrifice for the good of the kingdom and the people. As Antigonus Gonatas reputedly expressed it, kingship is an endoxos douleia, a glorious servitude. That phrase expresses the best ideal of Hellenistic kingship. The servitude is the hard work for the benefit of the subjects and the realm; the glory is what the king wins by performing this servitude tirelessly and well.

2. THE ARMIES

The Hellenistic kingdoms were empires conquered by the spear and maintained by the threat, and at times the active exercise, of military force. Strong and effective standing armies were, consequently, vital to establishing and sustaining security within these kingdoms: keeping the provinces loyal and quiet and deterring or seeing off threats from the outside. The nature of the armies of the Hellenistic kings was that established by Philip II: his army and military system continued to be the standard followed throughout the Hellenistic world. That is to say that at the core of each army was a mass of pikemen armed with the Macedonian sarissa and trained in its use. Many of these pikemen were of Macedonian descent, thanks to the numerous Macedonian military colonies founded by the Successors of Alexander; many more, however, were from the native Asian peoples, equipped and trained as Macedonian-style pikemen after recruitment who, from being originally merely “military Macedonians” eventually came to be considered and treated as Macedonians in every way, just as Philip II had turned Thracians and Illyrians into Macedonians. In addition, the armies had thousands of cavalrymen trained in the Macedonian style of cavalry fighting; units of specialized mobile infantry and cavalry to guard the armies’ flanks in battle and do the scouting, skirmishing, and foraging; and there were usually units of native troops fighting in their own equipment and styles as auxiliaries.

Since our historical sources are chiefly interested in warfare, we have plenty of testimony of these armies in action. But for a more detailed look at the organization and discipline of such Hellenistic armies, a remarkable inscription found near the city of Amphipolis provides special insight. It records the military regulations in force in the Macedonian army when on campaign in the time of Philip V, and I quote from its remaining fragments here by way of illustration.

Making rounds: in each regiment night rounds are to be made in turn by the tetrarchoi (sergeants) without lights. Anyone sitting down or sleeping on guard duty is to be fined by the tetrarchoi for each infraction one drachma (roughly a day’s pay) …

Equipment: those not bearing the weapons assigned to them are to be fined according to regulations: for the stomach-guard, two obols; for the helmet, the same; for the sarissa, three obols; for the sword, the same; for the shin-guards, two obols; for the shield, a drachma …

Construction of quarters: when they have completed the palisade for the king and the other tents have been pitched and a space has been made, they are immediately to prepare the bivouac for the hypaspists (an elite infantry unit) …

Foraging: if anyone burns grain or cuts down vines or commits some other disorderly act, a reward for information against them is to be paid by the generals …

Passwords: guards are to receive the password whenever they close or open the passages through the palisade …

(Austin The Hellenistic World doc. 74 = Moretti ISE II.114).

There is a good deal more, but these brief quotations are sufficient to give an idea of the care that went into organizing and regulating the Macedonian army in this era. Soldiers in this military system knew exactly what was required of them, and an exacting military discipline was maintained, with substantial fines for infractions against discipline. Soldiers were responsible for keeping their assigned equipment in good condition, for setting up camp in an orderly way, for maintaining proper discipline while foraging and while on guard duty, and so on. The duties of officers to oversee all of this were laid out in detail. Overall, the regulations establish that a Hellenistic army, at any rate under those kings who paid attention and saw to the maintenance of order, was a well organized and smoothly functioning military machine. The success of such armies in creating and maintaining the Hellenistic kingdoms can be readily understood. It is noteworthy that these particular military regulations come from the reign of the Antigonid king Philip V, whom we have seen above to have been a conscientious ruler and a successful military commander.

There was, of course, in the conquered lands of Asia and Egypt, an inevitable disjunction between the Macedonian armies, which were invasive and drawn from a population of settlers brought from the outside, and the native peoples over whom they ruled and whose submission they guaranteed. This disjunction was most clearly manifested in the case of the use of native troops as auxiliaries in the Macedonian armies. Most of the time, Hellenistic rulers in Asia and Egypt took care to use native forces sparingly, and in restricted and subordinate roles, in order not to give such forces, and the peoples they were drawn from, the idea that they might rival or even challenge the military capabilities of the elite Macedonians and other Greeks. What could happen if these restrictions were not observed is seen in the case of the Ptolemaic army in the late third century, when an emergency situation led king Ptolemy IV to make greater use of, and place more reliance on, Egyptian troops than was wise for a non-Egyptian ruler.

In 218 Ptolemy IV faced an invasion of Palestine, which the Greeks tended to call Coele (Hollow) Syria, by Antiochus III at the head of a great army. While Ptolemy IV mostly concerned himself with the pursuit of pleasure, his ministers Agathocles and Sosibius had been preparing for this invasion for some time, and succeeded in gathering a large army to oppose it. They had pursued every avenue to find troops, not just mobilizing the Macedonian and other Greek manpower resources of Egypt, but sending agents abroad to find allies and mercenaries from Greece and elsewhere. They kept Antiochus occupied with diplomatic missions and negotiations while they prepared their force: the whole tale is recounted in detail by the historian Polybius (5.63–64). In the end, they were able to gather a pike phalanx of some twenty-five thousand men and more than eight thousand mercenaries. In addition there were a little less than six thousand cavalry, of whom some two thousand were mercenaries recruited from Greece. Specialized light infantry forces included three thousand Cretan archers, another three thousand Libyans trained to fight in the Macedonian style, and around six thousand Thracians and Galatians drawn from settlers in Egypt. But altogether these forces were not enough to stand up to the army Antiochus had mobilized. The army was, therefore, supplemented by native Egyptian infantry: “the Egyptian contingent made up a phalanx of about twenty thousand men, under the command of Sosibius” (Polybius 5.65). When the showdown battle finally occurred, at Raphia in southern Palestine in summer of 217, Antiochus defeated Ptolemy’s cavalry and made the classic mistake of over-pursuing. While he was gone, Ptolemy’s infantry phalanx defeated that of Antiochus and won the battle, the Egyptians playing a significant role in bringing about this success.

For the moment that was a good outcome: Ptolemaic control of Palestine was assured. But Polybius (5.107) describes the aftermath, a few years later:

after this Ptolemy became embroiled in a war against the Egyptians. For by arming the Egyptians for the war against Antiochus, this king (Ptolemy IV) made a decision which was acceptable in the short term but a great miscalculation for the future. For the Egyptians were elated by their success at Raphia and could no longer endure to take orders, but sought someone to lead them as they now believed they were able to fend for themselves; and that is what they achieved not long after (in 207/6 BCE).

The war was a disaster for Ptolemaic Egypt, severely weakening Ptolemaic rule and lasting for decades: large parts of upper (i.e. southern) Egypt escaped Ptolemaic control entirely until finally “pacified” around 186. As Polybius later summed it up (14.12): “this war, apart from the savagery and lawlessness each side displayed to the other, involved no regular battle, sea-fight, or siege, nor anything else worth mentioning.” That is to say, it was fought in guerrilla style, with extreme brutality on each side: the Egyptians trying to drive out the hated Greek and other settlers, the Ptolemaic forces trying to force the Egyptians back into subjection. The utter reliance of the Hellenistic powers on having a strong standing army with a predominance of Macedonian and other Greek manpower could not be more clearly demonstrated.

What such a standing army looked like, when it was well taken care of, is illustrated by another famous event: a military parade held just outside Antioch, in the suburb of Daphne, by the Seleucid king Antiochus IV. After the Romans had defeated and deposed the Macedonian king Perseus, and forced Antiochus himself to retreat from Egypt when he seemed on the verge of conquering it and adding it to his realm to replace his father’s loss of Asia Minor, Antiochus decided to make a grand show of military strength, to let the world know he was still a force to be reckoned with. In 166 a great festival was held at Daphne, with envoys attending from all around the Greek world, and the parade of the Seleucid army was at the heart of the festival. Polybius sets the scene (30.25):

The public ceremonies began with a procession composed as follows: first came some men armed in the Roman fashion, equipped with corslets of chainmail, five thousand in the prime of life. Next came five thousand Mysians, followed by three thousand Cilicians armed as light infantry, and wearing gold crowns. Next came three thousand Thracians and five thousand Galatians. They were followed by twenty thousand Macedonians, five thousand armed with bronze shields, and the rest with silver shields, who were followed by two hundred and forty pairs of gladiators. Behind these were a thousand Nisaean cavalry and three thousand native horsemen, most of whom had gold plumes and gold crowns, the rest having them of silver. Next to them came the Companion Cavalry, a thousand in number, all with gold ornaments, closely followed by the corps of king’s “friends” who were the same in number and equipment; after these came a thousand picked men, next to whom came the Agema or guard, which was considered the strongest of the cavalry, and numbered about a thousand. Next came the cataphract cavalry, both men and horses acquiring that name from the nature of their armor; they numbered fifteen hundred. All the above men had purple surcoats, in many cases embroidered with gold and heraldic designs. And behind them came a hundred six-horsed, and forty four-horsed chariots; a chariot drawn by four elephants and another by two; and then thirty-six elephants in single file with all their furniture on.

Assuming, as we surely must, that the five thousand men armed in the Roman fashion were “Macedonians” being retrained in the newest style of warfare exemplified by the successful Romans, we can see that even after the massive setback of Antiochus III’s defeat at Magnesia, the Seleucid army still mustered some twenty-five thousand Macedonian infantry and four thousand cavalry as its core, supplemented by a variety of forces drawn from other settlers (the Thracians and Galatians) and native peoples, both infantry and cavalry. The military colonies in Syria and Mesopotamia evidently remained strong and continued to produce a steady supply of recruits, and the army headquarters at Apamea-on-the-Orontes was still doing its job of training and equipping a Hellenistic army in the best traditions. That this was no mere parade army is illustrated well by Antiochus’ successful invasion of Egypt in 168/7, mentioned above, which failed to conquer Egypt only because of Roman intervention. Strong leadership by Antiochus and his older brother and predecessor Seleucus IV had enabled the Seleucid kingdom to recover well from its loss of Asia Minor. The army still thrived, and but for the civil wars between descendants of Seleucus IV and Antiochus IV, the Seleucid kingdom might have remained a significant power for much longer than it did. But it was not kings and armies that were the heart and soul of Hellenistic civilization: it was Greek cities.

3. THE CITIES

While many political, military, and cultural leaders from ancient Greece are still famed in western civilization, there are others whose fame has undeservedly faded. One of these is Hippodamus of Miletus. His influence is still strongly felt in western and indeed world civilization, though few outside a narrow specialty are likely to have heard of him. Hippodamus was a town planner, the first we know of, and he made his name in the late 490s when he was commissioned by the Athenians to design the new port city they were building at the Piraeus, which is still today the greatest harbor in Greece. The design Hippodamus established for the Piraeus, and which he popularized in a great book he wrote on urban design, was to influence all subsequent Greek city-building, and still influences modern urban planning. Though he did not invent it per se, Hippodamus adopted and popularized the rectangular grid design for cities, which is sometimes known as the Hippodamian plan as a result. Modern people are very familiar with this Hippodamian design from many modern examples, the most famous being perhaps New York City. Establishing a rectangular grid based on broad parallel avenues with narrower cross-streets intersecting them at a ninety degree angle, and siting public spaces, most importantly a main town square, at suitable locations within this grid, made for a city that was easy to live in and readily navigable, as inhabitants of New York and many other modern cities know well. The relevance of Hippodamus and his urban design in the present context is that during the Hellenistic era a vast number of new cities were founded in western Asia and north Africa which almost all, to some degree at least, used the Hippodamian design.

23. Stoa of Attalus in the agora at Athens

(Wikimedia Commons photo by Ken Russell Salvador, CC BY 2.0)

Between about 330 and the middle of the second century BCE many dozens, in fact ultimately probably several hundred Greek towns and cities were founded or re-founded and developed in western Asia, from the Mediterranean to the Hindu Kush, and—to a more limited degree—in north Africa, that is in Egypt and Libya. And with very few exceptions, these towns and cities were built up according to the rectangular grid, Hippodamian plan of urban design. The historian Peter Green criticized these cities as showing a “dreary sameness,” but I think he misses the point. The Hellenistic towns and cities were designed to give a sense of comforting familiarity, to make the Greek settler, citizen, or traveler feel at home.

Each city would, as a matter of course, have a surrounding wall defining the urban space and marking it off from the chora, the countryside. When one entered the city through its main gate, one would find oneself on a broad avenue that would lead one directly to the main town square, or agora. Around the agora would be several long colonnaded buildings of the type called a stoa (see ill. 23). In the colonnades of these buildings, citizens and visitors could meet and/or take their ease, in the open air but protected from the sun or rain. At the back of these buildings were enclosed rooms that functioned as shops or offices of public officials. Looking out from the agora, the city skyline would be dominated by other public buildings: temples of the gods, a theater, a gymnasium. The travel writer Pausanias made it clear that any place that wished to be considered a city must have such buildings, with their associated amenities and services, and archaeological exploration of Hellenistic cities bears him out.

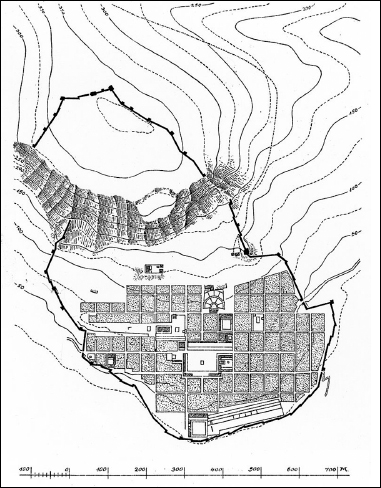

24. Street plan of Priene showing Hippodamian grid design

(Wikimedia Commons, Wellcome Images, CC BY 4.0)

Other than the spaces set aside for public buildings and uses, the city would be divided, by the avenues and cross-streets, into housing blocks where the citizens lived in private houses or, at times in the larger cities, in apartment buildings. In every region of the city there would be a public fountain house, with clean drinking water piped in from a nearby spring or other source, to meet the water needs of the families living in that region. In this way, the Hellenistic cities corresponded to a clear and generally understood and accepted conception of what a Greek city should be, how it should look, what sort of physical infrastructure and amenities should be present, and therefore what sort of lifestyle was to be pursued there.

Wherever one traveled throughout the Hellenistic world, one would find Greek towns fulfilling this conception of urban life and offering this lifestyle, and in every major region of the Hellenistic world one would find, in addition to the smaller towns and cities where most Greeks lived, also one or more larger cities—regional metropolises—where a wider array of services could be found and a higher level of culture could be sampled. The “sameness” that Peter Green critiqued was planned and desired. It made for a clear sense of belonging and common identity among the Hellenistic cities and their inhabitants.

This sense of common identity is well illustrated by a highly informative inscription surviving from the Macedonian town of Beroea (see map 2), recording a public decree of the people of that town:

When Hippocrates son of Nicocrates was strategos (chief magistrate), on the nineteenth of Apellaeos, at a meeting of the assembly, Zopyros son of Amyntas, the gymnasiarch … proposed: whereas all the other magistracies are carried out in accordance with the law, and in the other cities in which there are gymnasia and anointing is practiced the laws on gymnasiarchs are deposited in the public archives, it is appropriate that the same should be done among us and that the law which we handed in to the exetastai (public auditors) should be inscribed on a stone block and placed on view in the gymnasium, and also deposited in the public archive; for when this is done, the young men will feel a greater sense of shame and be more obedient to their leader, and the revenues will not be wasted away as the gymnasiarchs who are appointed will discharge their office in accordance with the law and will be liable to render accounts. Therefore, the city resolved: that the law on the gymnasiarchy which Zopyros son of Amyntas, the gymnasiarch … introduced, should be valid and be deposited in the public archive, that the gymnasiarchs should use it, and that the law should be inscribed on stone and set up in the gymnasium. The law was ratified on the first of Peritius (Austin The Hellenistic World doc. 118).

The inscription continues with the law proper, regulating the use and oversight of the gymnasium in great detail. What we learn is that, like any self-respecting Hellenistic city, Beroea had a gymnasium, and the citizens of Beroea attended that gymnasium to exercise and bathe. But at the time of this decree, it was brought to the attention of the Beroeans that they had as yet no law regulating the use of the gymnasium, though having such a law was the norm in the Greek cities. This was clearly felt to be a lack: in order for Beroea to “hold its head up” in the community of Greek cities, that lack must be filled. And so a detailed law regulating the use of the gymnasium, and the precise duties and responsibilities of the gymnasiarchs, was offered, adopted, and officially published by being inscribed on stone and publicly displayed. We see here, that is, a clear desire to conform to a recognized standard of what a Greek city should be.

The life lived by the citizens of these cities was on the whole a comfortable and pleasant one. Citizens and visitors were guaranteed an array of amenities and services that made for this pleasant lifestyle. I have already mentioned the public fountain houses around the city that guaranteed a clean and plentiful supply of drinking water. Fouling the public fountains was a serious crime that was harshly punished. There were public granaries where citizens could purchase grain—to be baked into bread—at an affordable price. The religious life of the citizens was taken care of in well maintained temples and sanctuaries with regular festivals that offered enjoyable holidays throughout the year. Social life centered around the agora with its stoas where people could meet and shop or take care of public business, and the gymnasium where citizens could exercise and play together, bathe, and enjoy other amenities. Gymnasia often had concert spaces where musical performances, literary readings, or lectures could be attended. And it was common for gymnasia to have dining rooms that could be rented for private parties. Other public entertainments—plays and concerts—were put on throughout the year at the theater, which was free for citizens to attend.

All of these amenities and services required oversight, and the Greek cities had developed an array of magistrates—drawn usually from the wealthy elite—whose job it was to see to the upkeep of the city and its services. The evidence for these civic magistrates is scattered, but altogether it adds up to a good picture of how such cities were run. Cities elected chief magistrates—often called strategoi (literally, generals)—to oversee the whole system, along with guardians of the law (nomophylakes) to see that the laws and regulations were obeyed. Astynomoi or city-wardens had the task of looking after the city’s infrastructure and services, along with a host of more specialized magistrates. There were gymnasiarchs to oversee the gymnasium; sitophylakes (grain wardens) to take care of the public granaries and ensure they were well stocked; agoranomoi (market wardens) to ensure orderly market squares and see to it that market stalls and shops functioned legitimately, using proper coins, weights, and measures; nuktophylakes (night guards) to see to public order during the dark hours of the night (there was no street lighting); amphodarchai (street wardens) to see to the upkeep and cleanliness of streets and drains. To illustrate the functioning of these magistrates, we are fortunate to have a substantial portion of the municipal administrative code of the city of Pergamon in north-west Asia Minor (see map 5), dating from the late third or early second century BCE.

[Concerning the streets] … the amphodarchai shall compel those who have thrown out rubbish to clean the place up, as the law requires. If they fail to do so, the amphodarchai shall report them to the astynomoi. The astynomoi shall issue a contract together with the amphodarchai and shall exact the resulting expense from the offenders immediately and shall fine them ten drachmas. If any of the amphodarchai fails to carry out his written instructions he shall be fined by the astynomoi twenty drachmas for each offense …

Concerning digging up the streets: if anyone digs up soil or stones on the streets or makes clay or bricks or lays out open drains, the amphodarchai shall prevent them. If they do not comply, the amphodarchai shall report them to the astynomoi. They shall fine the offender five drachmas for each offense and shall compel him to restore everything to its original state, and to build underground drains … similarly they shall compel already existing drains to be built underground …

Concerning the fountains: concerning the fountains in the city and in the suburbs it shall be required of the astynomoi to make sure they are clean and that the pipes which bring and remove the water flow freely. If any need to be repaired, they shall notify the strategoi and the superintendent of the sacred revenues, so that contracts (for repair work) are issued by these officials. No one shall be allowed to water animals at the public fountains nor to wash clothes or implements or anything else. Should anyone do any of these things, if he is a free man his animals, clothes, and implements shall be confiscated and he shall be fined fifty drachmas …

Concerning the public toilets: the astynomoi shall take care of the public toilets and of the sewers which run from them, and any sewers which are not covered (shall be covered?) … (Austin The Hellenistic World doc. 216 = Dittenberger OGIS no. 483).

This sampling from a much longer and more detailed document makes clear the care and attention that Hellenistic cities gave to the upkeep and oversight of their infrastructure and amenities, with careful instructions to the various magistrates regarding their exact duties and how to carry them out, and fines and other punishments for wrong-doers, whether citizens or visitors breaking the law or magistrates failing to carry out their responsibilities. The citizens of these cities cared deeply about the physical fabric of their cities, the services which they provided to themselves through this fabric, and the upkeep of the lifestyle that was thus afforded them. The moneys to pay for all this came from market (i.e. sales) taxes, import and export duties, sacred revenues flowing into the temples and sanctuaries from gifts and from sacred lands, from rents on public lands, and—very importantly—from contributions that the wealthy elite were encouraged (read, pressured) to make in lieu of taxes. The rich who co-operated and donated were celebrated as public benefactors and granted an array of honors and privileges that made it worth their while to be seen to be generous donors to the public good.

Besides all these services, which were a normal and expected part of Hellenistic civic life, most cities also showed concern for two other kinds of public service: health and education. It was common in the Hellenistic cities for funds to be made available, often via donations by the wealthy, to appoint public doctors whose charge it was to look after the health of any citizens needing medical attention. The sums paid to these public doctors as retainers were not always large enough to allow them to do their work free of charge; but it does seem that they normally tailored their fee structures to the citizens’ ability to pay, and there is evidence to indicate that when necessary they provided some medical care free of charge. We have an illustrative example known to us from an honorific decree passed by the people of Samos:

The council passed a motion to put this matter before the assembly held for elections: since Diodoros son of Dioscourides, who took over among us the role of public doctor, has for many years in the past time through his own skill and care looked after and cured many of the citizens and others in the city who had fallen seriously ill and was responsible for their safety, as has been vouched for frequently by many among the people each time when the contracts are renewed; and when the earthquakes happened and many among us suffered painful wounds of every sort because of the unexpectedness of the disaster and were in need of urgent attention, he distributed his services equally to all and assisted them … (Austin The Hellenistic World doc. 125).

This sort of attention to the public health needs of the citizens is attested by records from other cities too. In particular, an inscription from the city of Teos, regarding tax exemptions granted to new citizens in about 300 BCE, reveals how such public doctors might be paid:

Those who wish may raise pigs up to (a specified number?) and sheep and they shall be exempt from tax. And they shall be exempt from the other taxes too, except for the tax for the maintenance of doctors (Austin The Hellenistic World Doc. 99).

In other words, some cities at least raised a special tax from the citizens to pay for the upkeep of a kind of public health service of doctors whose job it was to accept any citizen in need as a patient, and take care of them.

Regarding education, it is important to note that Hellenistic cities were almost all organized as formal democracies, with the general citizen body sovereign and meeting regularly throughout the year to discuss and vote on matters of public policy and interest. The evidence for this is overwhelming, in the form of numerous publicly voted decrees from cities all around the Hellenistic world. And for the citizens to function democratically, debating public issues in a sensible way, they needed to be informed. That meant, in effect, that they needed to be able to read, since proposals, decrees, and laws were publicized by being written up and exposed publicly in the agora and/or other public spaces. Schooling was therefore a public need, and schools at which the sons (and sometimes daughters too) of citizens could learn the basics of literacy are well attested. Though most such schools were private ventures, there was a perceived public interest in making sure that the schoolmasters running these schools knew their job and provided value for the fees they charged. It was not uncommon, consequently, for cities to have a magistrate whose task it was to oversee the schooling of the young: the usual title was paidonomos or child-warden. In some cities we happen to know that schooling was provided free of charge: a wealthy citizen might establish a trust fund to pay the fees of teachers whose job would be to educate the children of the citizens. I shall close this section with one such example, from the city of Teos on the west coast of Asia Minor (see map 5):

So that all the free children may be educated just as Polythrus son of Onesimus in his foresight promised to the people, wishing to establish a most fair memorial of his own love of honor, he made a gift for this purpose of 34,000 drachmas.

Every year at the elections, after the selection of the public secretaries, three schoolmasters are to be appointed, who will teach the boys and the girls. The person appointed to the top class shall be paid 600 drachmas per year; the person appointed to the middle class shall be paid 550 drachmas; and the person appointed to the lowest class shall be paid 500 drachmas. Two physical trainers are also to be appointed, and the salary of each is to be 500 drachmas (Austin The Hellenistic World doc. 120 = Dittenberger Syll. no. 578).

The inscription goes on to require the appointment of a music teacher and to lay out how exactly the paidonomos shall assign children to each of the three classes by age and/or suitability, and to regulate what is to be taught and how and where. The point here is that Teos had, thanks to the generosity of a wealthy citizen, a public trust fund which paid for a free three-year education in literacy and music, as well as some physical training, for all the sons of the citizens, and remarkably their daughters too. This literacy was not just important as a political matter, to enable the citizens to function politically in an informed way. It was also important culturally: because Hellenistic culture was a reading culture, a culture of the book. And this is illustrated by another well known feature of Hellenistic urban civilization: the development of public libraries.

4. THE LIBRARY AND HELLENISTIC CULTURE

In the early decades of the third century BCE, Ptolemy I Soter and his son Ptolemy II Philadelphus established in Alexandria one of the great cultural institutions of western history: the Mouseion. This term, the origin of the English word museum, literally means a sanctuary of the Mousai (Muses), the goddesses who oversaw literature, music, and culture generally in Greek religious thought. But the Mouseion at Alexandria was far more than a religious sanctuary: it was a great research institute that offered housing and allowances to writers, philosophers, and scientists of all sorts, who could live at the Mouseion free of all the usual cares of life and just concentrate on their writing and/or research. And at the heart of the Mouseion, as its greatest resource and research tool, lay the great Library of Alexandria, the first great public library of the western tradition and one of the greatest libraries in western history. Libraries of a sort had already existed in Athens for decades: there were book collections at Plato’s Academy and at Aristotle’s Lyceum, and the Athenian public archive kept official copies of the tragedies and comedies performed each year at the Dionysia and Lenaea festivals. Not surprisingly, therefore, Ptolemy I brought to Alexandria from Athens a pupil of Aristotle named Demetrius of Phalerum to oversee the establishment of his great institute and library. Demetrius had governed his home city of Athens for ten years (316–307) as a kind of “philosopher-king” on behalf of the Macedonian ruler Cassander; but was seen by pro-democracy Athenians as a tyrant and driven out into exile, so Ptolemy’s offer came to him as a godsend. And he was ideal for Ptolemy’s purposes: besides his cultural and literary attainments as an Aristotelian philosopher, he had the leadership and organizational skills needed to get the Mouseion up and running.

Besides inviting to Alexandria, to stay at the Mouseion, leading men in every field of cultural endeavor, one of the key projects in establishing the Mouseion was building up its library. The learned Byzantine man of literature Johannes Tzetzes tells us that the aim of Ptolemy and Demetrius was to gather into the library “the books of all the peoples of the world”. The Christian heresiologist Epiphanius of Salamis knew of a letter written by Ptolemy to “all the sovereigns on earth” requesting that they have sent to him the writings of authors of every kind: “poets and prose writers, rhetoricians and sophists, doctors and prophets, historians, and all the others also.” Stories and legends accrued around this book-collecting. Supposedly the king sent to Athens offering a fantastic sum of money for the right to make copies of the original manuscripts of the great tragic dramatists, stored in the state archive of Athens. The copies were to be made at the Mouseion itself, and the story has it that Ptolemy in the end kept the originals for his library and sent the copies back to Athens. There was a law that every ship that put into Alexandria’s great harbor was searched by Ptolemaic agents, and any books on board were seized. They were copied by the scribes at the Mouseion, and the copies were returned to the ships, while the originals were placed in the library. Supposedly Ptolemy would visit the library regularly to receive updates from Demetrius on how the book-collecting was going. Demetrius would report on how many volumes were present, and on plans to acquire more. The goal, reputedly, was to acquire half a million volumes, at which point Demetrius calculated that every book in the world worth having would be present.

Ptolemy was not content to sit back and wait for books to come or be sent to Alexandria: purchasing agents were sent out around the Hellenistic world to track down and acquire rare books of every sort, whatever the cost. One book collection that eluded Ptolemy’s agents, however, was the writings of Aristotle. During his lifetime, Aristotle had published various writings in dialogue form, like those of his old master Plato. But his key writings that formed the basis of his philosophical teaching at his school in Athens, the Lykeion (Lyceum), were kept private. Aristotle left them to his pupil and successor Theophrastus, who in turn bequeathed them to the man he expected to succeed him, Neleus of Scepsis. But Neleus did not become head of the Lyceum, and in anger at being passed over he returned to his home town of Scepsis in the Troad, taking Aristotle’s writings with him. Ptolemy’s agents were alerted and showed up to purchase the writings; and the polymath Athenaeus of Naucratis, writing in the early third century CE, in fact reports the acquisition by the library of “the books of Aristotle and Theophrastus, from Neleus of Scepsis.” But whatever Neleus sold Ptolemy’s book-buyers, it was not the prized writings of Aristotle himself: those remained buried in a chest in Neleus’ ancestral home for nearly two hundred years until an Aristotelian enthusiast of the first century BCE finally tracked them down, enabling the world at last to read Aristotle’s true thoughts.

The library was not restricted to Greek texts. A learned Egyptian priest from the temple-city of On-Heliopolis named Manetho made a translation/adaptation of Egyptian chronicles and sacred writings into Greek for his patron Ptolemy II. The sacred writings of the great Iranian prophet Zarathustra—that is the texts sacred to the Zoroastrian religion, whoever their true authors—were reportedly collected and translated into Greek, totaling some two million lines of text. Most famously, there is the legendary story of the translation for the library of the Hebrew scriptures. The early Ptolemies ruled Palestine and it was easy for them, when Demetrius alerted them to the existence of these writings, to have the high priest at Jerusalem send copies of the texts along with religious experts to translate them into Greek. According to the legend, seventy-two translators were sent, who each labored independently for exactly seventy-two days to translate the texts, miraculously producing at the end of the seventy-two days translations that were word for word the same. However it was really produced, a well translated Greek version of the scriptures, known as the Septuagint (from the Latin word for seventy), did come about and is still the standard Greek version of the Old Testament to the present day.

For all the fascination of this acquisition process, the physical accumulation of books is only the first step in the creation of a great library, however, and it is the follow-up stages of analysis, categorization, and evaluation that made the library at Alexandria one of the great cultural institutions and changed Hellenistic culture dramatically. What happened at the Mouseion library over the centuries was the creation of library science, of textual scholarship, of literary theory, of new styles of literature that prized erudition as a key component of literary creation, and of a culture of the book as a prized component of a well rounded person’s life more generally. The process may be said to have begun with the analysis of multiple copies of Homer’s epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, and with the first formal head of the library per se, Zenodotus of Ephesus.

Copies of Homer’s great epics were widely available around the Greek world, and the library acquired a significant number of such copies. When these were analyzed, problems emerged: there were all sorts of differences from one copy to another. Missing or added words, words that made no sense and appeared to have been misspelled, whole lines or passages found in one copy but not in another: what was one to make of such anomalies, and how was one to discover the “true” text of Homer? Zenodotus set himself the task of analyzing the various copies of Homer and solving the problems. In doing so, he began to establish the basic criteria of textual scholarship. Homer’s characteristic style and vocabulary were analyzed, and words or passages that did not fit or seemed anachronistic were stigmatized as possible interpolations. Similarly, passages that seemed intrusive to the narrative, or not to fit in terms of Homer’s narrative method, were questioned. For example, Zenodotus famously questioned the authenticity of the description of Achilles’ shield in Iliad 18 as being unique and so un-Homeric. While Zenodotus himself may have been rather cavalier in his method, what came out of this work was true textual scholarship. Eventually Zenodotus’ successors produced lexica of the Homeric vocabulary, treatises on Homeric language and style, commentaries on Homer’s works explaining obscurities and difficulties, and official cleaned-up texts of the Homeric epics that are the source of all modern texts. And once this process had gotten under way with Homer, the works of other authors of all sorts were naturally subjected to the same analytical investigation.

Besides the work of analyzing and explaining, there was also the business of categorizing and ordering texts, because the texts collected could not just be piled higgledy-piggledy on shelves or in boxes. They had to be arranged in some rational manner, and a key role in this business was played by one of the most remarkable literary figures of the Hellenistic era: the poet Callimachus. Originally a schoolmaster in the city of Cyrene in modern-day Libya, Callimachus was brought to Alexandria to work in the library, and was eventually given the charge of producing a catalogue. After what must surely have been decades of labor and study, Callimachus produced the Pinakes, a catalogue of the books in the library ordered by distinct categories of literary work and with some account of each work. This work itself filled 120 book scrolls, and it in Callimachus established eleven different categories of literature, six of poetry and five of prose: lyric and epic poetry, tragic and comic drama, history and philosophy and oratory, and so on. Callimachus—building to be sure on the work of predecessors like Aristotle—established the criteria for these genres and divided the works of Greek literature among them. Eventually this work of classification also came to include judgements of quality, and one began to get lists of the best writers and works in each category. There were the nine lyric poets, the three great tragedians, and the ten orators, for example. Not every genre lent itself to such generally accepted lists: in history there was wide consensus that Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon were at the top, and almost all critics accepted Theopompus of Chios, Philistus of Syracuse, and Ephorus as the next three, but after that lists became more idiosyncratic: whether one should include Timaeus or Polybius or Timagenes were matters of dispute. But what came out of this work was a universally accepted sense that in every genre there were “classic” or “canonical” authors and works which established and illustrated the very best of what could be done in each genre.

Once this process was well underway, it became understood that to be a person of taste and discrimination one had to be familiar with “the classics,” and getting access to and reading these classic works was thus expected of every citizen of the Greek cities who prided himself (or herself) on being well educated. The literature written during the Hellenistic era adapted itself to this taste for erudition, and to the existence of a large literate audience. At the top level of culture writers began to produce works which displayed their own erudition. The poet Callimachus, mentioned above, pioneered a new kind of poetry that was highly polished and full of tags from and allusions to the classic works. In order to fully appreciate Callimachus’ poems, one needed the near encyclopedic knowledge of classical writings that Callimachus himself had, thanks to his labors in the library. A modern comparandum would be poems of T. S. Eliot—”The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock” or “The Wasteland,” for example—which are similarly full of quotations and allusions and require a good commentary to appreciate fully. In a somewhat different way, there is the epic Argonautica by Callimachus’ rival Apollonius of Rhodes, stuffed full of geographical and ethnic details drawn from the latest historical works such as Nymphis of Heraclea’s history of his home town and of the southern Black Sea region generally. In one way or another, erudition was the order of the day for such Hellenistic writers.

Alongside this rather “highbrow” literature, Hellenistic writers also responded to the existence of a wide readership by producing more “popular” works: poetry reflecting rural nostalgia, for example, or humorous mimes and romantic novels. The Syracusan poet Theocritus composed “idylls”, many of which were set in an imagined countryside where shepherd lads lazed under spreading oak trees and competed musically with each other for the attention of winsome shepherd lasses. One can imagine the type of city-dwellers who enjoyed reading or listening to this. Herondas wrote short stories called “mimes” which portrayed humorous (and sometimes erotic) vignettes from everyday life, clearly aimed at readers seeking a break from their perhaps somewhat monotonous existences. And after about 200 BCE the first romantic novels began to appear, starting with the highly fictionalized Alexander Romance, and continuing with stories of piracy, kidnappings, magic, travel, and love triumphing in the end in the face of all adversity. Greeks living in fifth- and fourth-century Athens or Corinth or Sparta had plenty of adventure in their lives: real wars, with real battles on land and at sea, real travels, and all too often real adversity. In the safer but more humdrum existence of the Hellenistic citizens, fictional adventures had to take the place of real ones, which was all to the good, of course. The point is that reading material was being created for a wider reading audience than the highly educated elite, making it likely that many citizens were now reading or attending public readings of books. Already in the early fourth century Plato tells us a book could be bought in the agora of Athens for a drachma—a day’s wage for the average skilled worker. With papyrus production in Ptolemaic Egypt ramping up, the price of books went down, and it was not so unusual for a citizen to own a few books. But as long as books were produced by being copied out by hand, books would remain relatively expensive and relatively rare. And that of course is where libraries came in.

Naturally, the great library of Alexandria did not remain unique. In the late third century BCE Antiochus III sponsored the creation of a great royal library at Antioch in Syria, employing the poet and grammarian Euphorion of Chalkis as chief librarian. The Macedonian kings also collected a royal library at Pella: Plutarch tells us in his biography of the Roman commander Lucius Aemilius Paullus that when he defeated the last Antigonid king Perseus and conquered Macedonia in 169, he kept the books of the royal library as his personal share of the booty, on behalf of his sons. Most famously, the Attalid kings of Pergamon in the early second century created a great library to rival the Ptolemaic library in Alexandria. At its height, we are told that the library of Pergamon held upwards of two hundred thousand book scrolls. The Roman polymath Pliny the Elder tells us that, not wanting to rely on the importation of paper from Egypt, the only place where the papyrus reed was known to grow in abundance, the Attalid kings sponsored the production of an alternative writing material made from animal hides and known today as parchment, a word which derives from the name Pergamon (as may be seen more clearly in the Dutch form of the word parchment—perkament). Eventually other cities began to copy these royal libraries by developing libraries of their own, for the use of their citizens: such libraries flourished around the Hellenistic world in the Roman period, as we will see below in section 6 of this chapter. Libraries collected and owned by private citizens also became a thing in that era, as we shall see. Hellenistic culture was truly a culture of the book.

5. THE ROMAN CONQUEST

In 201 BCE the Romans emerged from an epic two-war struggle with the Carthaginians, a struggle that had begun as far back as 264, as masters of the entire western Mediterranean region. They controlled all of Italy, the islands of Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, and a good portion of Spain—all of Mediterranean Spain in particular. In north Africa, the Carthaginians were thoroughly submissive subject allies, and the kingdom of Numidia (much of modern Algeria) was a client state under their domination. Not surprisingly, the Romans turned their eyes eastward, to the wealthy and highly civilized Hellenistic kingdoms in the eastern Mediterranean. As we have seen, Philip V of Macedonia had made the mistake of allying with the Carthaginians against Rome when it seemed as if the Romans would lose, and vengeance against Macedonia was therefore the first order of business. The Romans were slightly hampered by the peace treaty they had signed with Philip in 205, but they knew ways around the legal niceties of treaties. A roving commission of ambassadors was sent around the Greek world to collect any and all grievances against Philip, who was then given an ultimatum to redress those grievances at once or else the Romans would be “obliged” to make war on him in defense of their “friends” in the Greek world. In Roman eyes, making war in “defense” of these new-found “friends” would be a just war, treaty or no treaty.

Over the course of the next century and a half, the Greeks of the Hellenistic world learned some hard lessons about the Romans: it was never safe for an independent state to have any dealings with the Romans, whether as friends or enemies. Enemies were made war on, defeated, and subjected; but “friends” were expected to show gratitude by being as submissive to Rome as if they had been conquered, and “friends” who failed in such submission soon found themselves being conquered. A series of epic battles early in the second century—the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 against Philip V, the Battle of Magnesia in 190 against Antiochus III, and the Battle of Pydna in 168 against Philip’s successor Perseus—established Roman dominance over the Hellenistic world. Various follow-up operations were needed to complete full Roman control: there was the Fourth Macedonian War and the Achaean War in 148–147, the subjection of the Pergamene kingdom in 132, and very difficult warfare against Mithridates VI of Pontus in the 80s BCE and again in the late 70s. In the end, it was not until the campaigns of the Roman general Pompeius Magnus in the 60s, and Caesar Octavian (later known as Augustus) annexing Egypt in 30, that full Roman rule over the entire Hellenistic world was rounded off. Thereafter, the Hellenistic world formed the eastern half of the Mediterranean-wide Roman Empire, the former kingdoms now being Roman provinces ruled by Roman governors and secured by Roman armies.

How exactly did the Romans take over the seemingly powerful Hellenistic kingdoms with such apparent ease? The key lies in the very different military systems of the Romans and the Macedonians. The Macedonian-ruled kingdoms, as we have seen, relied for their security on professional standing armies, recruited from a military elite and carefully trained in a complex and demanding system of warfare. These professional soldiers could be complemented by allied “native” troops drawn from the peoples of Asia and/or Egypt, but the Macedonian rulers preferred not to rely heavily on such troops for reasons discussed above (section 2). While there was enough Greco-Macedonian manpower to field large armies of thirty thousand to fifty thousand men when necessary, while keeping thousands more in forts on garrison duty, if the field army were to be defeated with heavy losses the ruler in question would be forced to sue for peace: it would take years to recruit and train replacements and be able to take the field again with a credible army; in the case of Philip V, for example, we have seen that it took around fifteen years for the Macedonian army to recover from Cynoscephalae.