“Prussia is not a state with an army, but an army with a state.”

—COMTE DE MIRABEAU

“Prussia is not a country with an army, but an army with a country.”

—FREIHERR VON SCHROETTER

“Whereas some states possess an army, the Prussian army possesses a state.”

—VOLTAIRE

THIS REFLECTION ON THE NATURE OF THE KINGDOM OF PRUSSIA IN THE eighteenth century, whichever writer/thinker one should properly attribute it to, provides an interesting comparison to the Macedonia of Philip II. A succession of remarkable rulers of the Hohenzollern dynasty—from the “Great Elector” Frederick William (1640–1688) to King Frederick “the Great” (1740–1786)—created one of the most disciplined and feared armies of early modern Europe and used it to transform a mish-mash of inherited lands in northern and eastern Germany and north-central Europe into the tightly knit and tightly controlled kingdom of Prussia, which thanks to its remarkable army and officer corps became one of the great powers of Europe. It was the centrality of the army to constructing, uniting, and controlling Prussia that gave rise to the above reflections.

Similarly, it was the creation of his remarkable new army, military system, and officer corps which enabled Philip to transform the disunited, weak, and backward territories making up the Macedonian lands into a united kingdom, tightly controlled by the king, and the strongest military power in the eastern Mediterranean region. Like early modern Prussia, therefore, Macedonia under Philip and Alexander was truly “an army with a state,” and a careful study of the creation and nature of the Macedonian army under and by Philip is, therefore, at the same time a revelation of the nature of the Macedonian state built by Philip. During his remarkable twenty-four-year reign, almost every element of the Macedonian army was fundamentally reformed by Philip, creating a new and innovative style of warfare which was highly demanding of the skills of the commander and officers of the army, but virtually unbeatable by any contemporary force or military system. The three most crucial elements of Philip’s new army were a completely new heavy infantry force, a specialized elite force of versatile infantry who were Philip’s main strike force and personal guard in battle, and a reformed and strengthened strike force of heavily armed cavalry. In addition, Philip developed specialized forces of mobile light infantry and light cavalry, which each played important roles in the overall military system; and he developed one of the first truly effective siege trains in Greek warfare, so that his military campaigns would not be stymied by fortifications. Finally, all these reformed and specialized military elements needed highly trained officers to lead them effectively and enable them to operate together on the field of battle under a coherent military plan. We must examine each of these elements of Philip’s “new model army” in turn, and then observe how the whole system functioned together in warfare and battle.

1. THE NEW MACEDONIAN PHALANX

In the words of Diodorus, writing about the first year of Philip’s rule: “he (Philip) first established the Macedonian phalanx” (16.3.2). That statement seems clear and determinative, but is in fact highly controversial. Diodorus wrote between about 60 and 30 BCE, some three hundred years after Philip’s day. The quality of his information depends on the source he was deriving it from, and we cannot be sure who that was. Meanwhile, we have another statement about the Macedonian army that seems at odds with Diodorus’ statement, and this other statement comes from a writer contemporary with Philip and Alexander, named Anaximenes of Lampsacus. The late antique lexicographer Harpocration preserves the following fragment of Anaximenes’ work:

Anaximenes in book 1 of the “Philippica,” speaking of Alexander, says: “Afterwards, accustoming the most notable to serve as cavalry, he called them hetairoi (companions); and dividing the masses and infantry into companies and tens and other commands he named them pezetairoi (foot companions); so that both sharing in the royal hetaireia (companionship), they should remain most devoted.”

The sense is that a ruler named Alexander established both the cavalry and the infantry and named them his companions. Here it must be noted that in the campaigns of Alexander the Great, the phalanx of Macedonian infantry are named pezetairoi in our sources. Evidently, therefore, the Alexander of Anaximenes’ passage is being credited with organizing the Macedonian infantry phalanx; and since the passage comes from the first book of the Philippica (history of Philip), it is often assumed that one of the two kings named Alexander before Philip’s time must be meant. That is to say, the Macedonian phalanx would have been established by either Alexander I or Alexander II.

There are problems with either identification. If the Alexander of Anaximenes is taken to be Alexander I, then why is there no sign of a Macedonian infantry phalanx in the campaigns of Perdiccas II in the 420s as described by Thucydides, or in the campaigns of Amyntas III in the 380s/70s described by Xenophon? Neither of these contemporary and well-informed historians knows of any Macedonian infantry phalanx, though if it existed it must have played a part in the wars they describe. For this reason, most historians reject the notion that Alexander I could have established the Macedonian phalanx. That leaves us with Alexander II, but the problem with this ruler is that he ruled only just over a year before being assassinated, and it is not easy to see when he would have had the time or authority to do the work described by Anaximenes. Though one or two notable historians, such as A. B. Bosworth, insist that Alexander II must have been meant, it seems in fact highly improbable that any such radical change to the Macedonian military could have been made by this brief and unsuccessful ruler. But what, then, are we to make of this evidence? Well, the point of Anaximenes’ testimony seems to have been the naming of the Macedonian cavalry and infantry, their inclusion in the royal hetaireia. And indeed, our sources do reveal that under Alexander III (the Great) the Macedonian heavy cavalry were referred to as hetairoi, and the infantry of the phalanx as pezetairoi. Under Philip, conversely, the name pezetairoi was used, as we shall see below, for an elite unit who functioned as the king’s personal guard in battle; while the hetairoi were the king’s personal entourage of elite Macedonian and Greek companions (e.g. Theopompus as quoted by Polybius 8.9: “those who were called Philip’s friends and companions,” about eight hundred in number according to Athenaeus 6.77, who draws on the same passage of Theopompus). Several historians, consequently, have suggested, rightly in my view, that Anaximenes was actually speaking of the Alexander—Alexander the Great—in a forward-looking digression. This will be discussed further in Chapter 5.

In sum, before Philip, we simply find no indication that any Macedonian phalanx existed, and we should therefore accept Diodorus’ statement that Philip first established it. Why was there no Macedonian phalanx before Philip, and how did he go about creating one? As we have seen in Chapter 1, what had prevented Macedonia from developing a hoplite phalanx like those of the southern Greek city-states was the fact that hoplite warfare was a citizen militia style of warfare: the warrior was responsible for arming himself. This was not a problem for the well-to-do “middling” elements in the Greek city-states, but Macedonia lacked such a well-to-do middle class, and for Macedonia’s poorer herders and farmers, let alone for the serfs, the expense of hoplite armor and weapons was prohibitive. Nor could Macedonian rulers, including Philip, afford the expense of providing ten thousand or more sets of hoplite equipment to poor Macedonians so as to enable them to fight as hoplites. That posed a serious quandary for Philip: he could recruit men, and he could no doubt organize and train them, but they would inevitably be lightly armored—lacking the expensive cuirasses, helmets, and shields of the hoplite warriors—and so, though they might put up a good fight against Illyrians or Thracians if well led and motivated, they could never make a stand against a southern Greek hoplite force. Philip was not content to have an army equal to the Illyrians and Thracians: he wanted outright superiority, and he wanted to match any hoplite phalanx in battle too.

The solution Philip found to this quandary was as simple and elegant as it was effective. Since there was no way to armor his men in a manner equivalent to southern Greek hoplites, he found an alternative to defensive armor which gave his men a much cheaper form of defense that was at the same time a potent form of offense. He adopted a kind of pike, some sixteen to eighteen feet in length (about five to six meters), called the sarissa (or sometimes sarisa). Probably deriving from the long spears used to hunt boar, a traditional pastime of the Macedonian aristocracy, it was first developed for military use (so far as we know) by Philip, presumably making its debut in the winter of 359/8. The advantages of this weapon were clear. Macedonia was, as noted in Chapter 1, a heavily forested region, and by tradition the ruler of Macedonia controlled the extraction of timber. Philip could thus easily provide as many wooden pike shafts as required at just the cost of cutting the wood. Another resource Macedonia enjoyed was mines: iron and copper were available to make steel spear heads and bronze butt spikes. As with the forests, the mines were a royal preserve, enabling Philip to acquire the necessary metal at low cost. This ready and cheap availability was a huge advantage, enabling Philip to equip thousands of men with this weapon quickly and easily. The second great advantage was the weapon’s reach: since a sarissa, at about seventeen feet in length, was double the length of the hoplite’s eight-foot doru (spear), a band of men equipped with sarissas could hold off a band of hoplites well out of reach of the hoplites’ weapons (see ill. 8), meaning that the Macedonian sarissa men had much less need of defensive body armor: the sarissa served as both offensive and defensive weapon.

8. Re-enactors show reach advantage of Macedonian sarissa over southern Greek hoplite spear

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image by Jones)

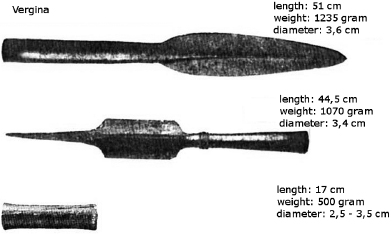

The shaft of the sarissa, normally three to four centimeters thick, was fashioned from ash or cornel wood, which provided straight shafts with a tough grain. Since shafts about fifteen feet in length (minus the length of the metal spear heads and butt spikes) were relatively hard to find and very awkward for soldiers to carry, the sarissa shafts were fashioned in two pieces which were carried separately and joined together by a metal cuff just before battle (see ill. 9). The spear heads were leaf shaped, forty to fifty centimeters long (including the shaft attachment: see ill. 9), and made of steel strong enough to penetrate armor with a powerful thrust. At the rear end, the sarissa was fitted with a butt spike which served three purposes. In the first place, it enabled the pike to be firmly fixed in the ground, either when not in use, or to anchor it to face a charging enemy. Because it was often driven into the ground, the butt spike was made of non-corrosive bronze rather than steel. In the second place, should the shaft of the sarissa break in action, the butt end remaining with the soldier could be reversed and, with its spike, would still make a formidable weapon. Thirdly, the butt spike counterbalanced the sarissa by adding weight at the back. The soldier would not want to hold the sarissa in its middle section, where the natural balance point would be, but towards its rear, so that as much as possible of the shaft would project out in front of the bearer: that length was, after all, the point of the weapon. A heavy butt spike would shift the balance point of the sarissa well back along the shaft, and make it much easier to hold the weapon leveled with most of its length projecting, without the weight of all that projecting wood and metal (the spear head) weighing on the soldier’s forward hand and arm and tending to make the spear head droop to the ground.

9. Head, butt-spike, and cuff of a Macedonian sarissa from the Vergina Museum

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Wielded two-handed and projecting out some twelve feet in front of the warrior holding it, the sarissa presented a dire threat to an enemy approaching from in front, and at the same time held that enemy well back from being able to harm the sarissa wielder with anything but a missile weapon. On the other hand, the sarissa man was vulnerable to arrows, javelins, or sling bullets; and the unwieldy seventeen-foot pike made him clumsy and slow to turn, so that he was easy prey to an enemy coming from the side or from behind. For protection against missile weapons, some kind of armor was needed; but the poor Macedonians recruited as pikemen could not afford extensive armor: else they would be hoplites. Since the sarissa occupied the left hand as well as the right, holding one of the large, convex, heavy hoplite shields with its double grip—one for the arm, the other for the hand (see ill. 3)—was out of the question even if it could have been afforded. Philip equipped his pikemen with small wooden shields, about two feet in diameter, that were strapped to the left arm leaving the hand free, and controlled by a neck strap. Much smaller and lighter than the hoplite shield, with its one-meter (about forty inches) diameter, the Macedonian shield (ill. 2) nevertheless covered much of the wielder’s torso against arrows and sling shot, and even javelins at a pinch. To protect the head, the Macedonian sarissa men wore relatively light, open-faced helmets of the Phrygian or Chalkidian type (see ill. 10), much cheaper than the full-head Corinthian helmet favored by southern Greek hoplites. Beyond this, the pikeman might wear a padded jacket or corslet of boiled leather or reinforced linen; and if he could afford them, some greaves (shin-protectors).

10. Macedonian open face helmet from Muzeul de Istorie din Chisinau (Moldova)

(Wikimedia Commons photo by Cristian Chirita)

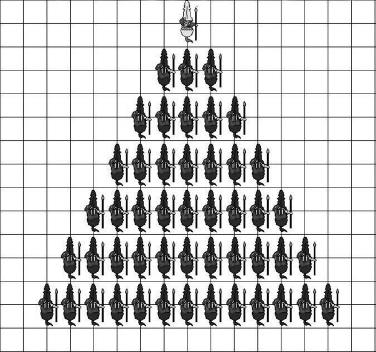

Still, a pikeman operating on his own was slow and easy prey; but the sarissa was not a weapon designed to be used in isolation. The point was to create a dense mass of pikemen, standing in close-order lines one behind the other, presenting to an enemy force a serried mass of pikes like a bristling porcupine. To ensure effective co-operation and co-ordination, the Macedonian pike phalanx was carefully organized and drilled to operate as a unit. The basic organizing sub-unit of the phalanx was the file of men standing one behind the other, each man belonging to a different line of the phalanx. The file of men in the phalanx was called a dekas: literally a group of ten, though the term could be used more generally to refer to a “company” of men (see the Greek Lexicon of Liddell and Scott, s.v.). In the case of the Macedonian phalanx, it seems the dekas was actually made up of eight men, with the front man of the file being the file commander—a position similar to being a corporal in a modern army—and the rear-most man, called the ouragos, also having a kind of “non-commissioned officer” status. Directly behind the file commander, in the second and third places in the file, were two experienced and trustworthy “double pay” soldiers, who would have to step forward to command the file if the front man were to be killed or incapacitated. Thus four of the eight men in the dekas were ordinary rankers, two were essentially (in modern terms) non-commissioned officers in charge of the file, and two were trusted veterans who could take over from the file commander at need. The responsibility of the file commander was to lead the file forward; by maintaining his place in the front line of the phalanx to ensure that the men behind him also occupied their places in their respective lines; and no doubt to call the order to lower or raise the pikes as needed to fight or march. The ouragos’ responsibility was to hold his position and keep the men of the file in front of him, ensuring that they did not turn to flight.

With a file (dekas) of eight men, it is clear that a standard phalanx depth of eight lines was envisioned; this was also the standard depth of the southern Greek hoplite phalanx. However, there is much evidence to indicate that the Macedonian pike phalanx was in practice often a significantly deeper formation. It was common for two, three, or even four files to be drawn up one behind the other, giving a phalanx of sixteen, twenty-four, or thirty-two lines of men. The number of lines preferred would of course be determined by the equipment and formation of the enemy, the number of pikemen present and the number of men in the enemy formation, and the nature of the terrain. When confronting lightly armed Balkan (Illyrian, Thracian, and so on) infantry formations, a pike phalanx only eight lines deep might well be considered perfectly adequate unless the numbers of pikemen and nature of the terrain dictated a deeper formation; but when encountering the heavily armored southern Greek hoplite phalanx, it seems that a deeper pike phalanx of sixteen or thirty-two lines was definitely preferred.

In addition to the file or dekas, the pikemen were also organized into lochoi (companies) of several hundred men—the exact details are obscure—each with its officer known as the lochagos. The most important unit of the pike soldiers, however, was the taxis or battalion, about fifteen hundred men strong. Each taxis had its own organization and commander, and formed essentially an independent phalanx; for a phalanx is a formation, not a unit, and the infantry phalanx as a whole was made up of the individual fifteen-hundred-man-strong taxeis drawn up next to each other. Each taxis was recruited locally in the various regions of Macedonia: we know of taxeis from the regions of Tymphaia and Orestis, for example, and Arrian (3.16.11) reveals that when new Macedonian recruits reached Alexander at Susa they were assigned to the infantry taxeis “according to their ethnos,” that is, according to the region of Macedonia they came from. In the army with which Alexander crossed to Asia in 334, which was the army he had inherited from Philip two years earlier, there were twelve thousand Macedonian heavy infantry, while an equal number were left to serve as the Macedonian home army under the regent Antipater. The twelve thousand with Alexander consisted of six taxeis (a total of nine thousand men) plus the three thousand hypaspistai (on whom see section 2 of this chapter, below). This means that eight taxeis of pikemen were left with Antipater (8 x 1500 = 12,000), showing that in Philip’s army there were fourteen taxeis of pikemen altogether.

Our best account of the superb training and discipline of the sarissa-wielding infantry in their taxeis in phalanx formation comes from the first year of the rule of Alexander, when his army was—let it be said again—the army he had just inherited from Philip, recruited, organized, and trained by Philip. Arrian tells of Alexander’s campaign in Illyria in 335, and of a situation where Alexander’s army was hemmed into a narrow valley overlooked by wooded hills occupied by enemy forces. His account of how Alexander maneuvered the pike phalanx to overawe and defeat the Illyrians runs as follows (Anabasis 1.6):

In this situation Alexander drew up his army with the phalanx 120 lines deep. Posting 200 cavalry on each flank, he ordered his men to be silent and swiftly obey the word of command. At first the infantry warriors were signaled to hold their pikes upright, then at the signal to lower them for the charge, and to swing the serried mass of their pikes first to the right, then to the left. He moved the phalanx itself forward quickly, bringing it round first to one side then the other. Thus in a short time he maneuvered the taxeis through many and varied formations, and finally making the phalanx into a kind of wedge facing left, he led it against the enemy. They were already amazed seeing the speed and order of the maneuvering, and they did not await the attack of Alexander’s men, but abandoned the first hills.

The superb order and discipline instilled into his pikemen by Philip is evident here, as the soldiers alternately raise and lower their pikes, swinging them to the right then the left, marching and counter-marching, and finally charging in a wedge. Noteworthy is the depth of the formation: 120 lines means fifteen files (dekades) one behind the other. One can understand the amazement and fear this extraordinary army of pikemen instilled in the enemy, and how it ruled the battlefields under Philip’s and later Alexander’s command.

2. THE ELITE PEZETAIROI

When the US army in World War II decided to have military historians accompany their forces in battle, to be able to record with the greatest immediacy and accuracy the history of the engagements and battles each unit fought in, they opened up a new era in military history and in our understanding of the nature of warfare. To their great surprise, these battlefield historians discovered that most soldiers, no matter how well trained, are in fact distinctly passive when in battle. They found that only about one of every four soldiers even discharge their weapons in battle, thereby doing the actual fighting, the rest basically hunkering down and trying to survive, offering at best vocal support to their more aggressive colleagues. Battle is an exceptionally frightening and stressful environment. We are all familiar with the “fight or flight” response of animals, including humans, when placed in great fear or stress; but this dichotomy overlooks an equally popular third option: that of simply hunkering down and doing nothing, giving in to the paralyzing tendency of fear and/or stress. We are familiar with this response in the animal world, which gives us such sayings as “playing possum” (pretending to be already dead to escape notice) or “burying one’s head in the sand” (from the ostrich’s supposed habit of lowering its head so as not to see the enemy, in the hope that the enemy will then bypass it). The plain truth is that rigorous training and discipline will make men hold their ground and stay in formation under the fear and stress of battle, but it cannot make them fight aggressively.

This passivity of most soldiers in the stress of battle was in fact well known to ancient war leaders. The most successful ancient warrior peoples found a way to cope with it: concentrating the most aggressive warriors in elite formations which were tasked with the most crucial roles in battle, requiring the most active and committed soldiers—the tasks which would directly lead to victory if carried out aggressively and well. For example, a Spartan army very rarely had more than a smallish percentage (usually perhaps ten to forty percent, depending on the occasion) of actual “Spartiates” (the true Spartan warriors) in it. The true Spartans—perhaps two thousand strong in an army of, say, twelve thousand—would be stationed on the right wing. When battle began, they would advance faster and with greater determination than their allies, would engage the enemy opposed to them first, and would invariably drive their direct opponents backward and away and then turn to the left to engage the rest of the enemy from the side. The Spartans’ allies were there to make up numbers and hold their ground; victory depended on the better trained, better disciplined, more aggressive, elite Spartiates; and for two hundred years or so this system enabled the Spartans to dominate the battlefields of Greece. In the second quarter of the fourth century, when for a generation the Thebans dominated Greek warfare, they relied on an elite force called “the Sacred Band” to spearhead their army in battle and by their determined and disciplined aggression to lead the army to victory.

Philip, who had spent a key part of his adolescence at Thebes at the height of Theban power, understood this principle as well as any war leader; and he made sure from the start of his career as ruler and military commander to develop one of the great elite forces in the history of pre-modern warfare. This elite unit dominated the battlefields of the near east under Philip, his son Alexander, and Alexander’s immediate successors. Philip called this unit his pezetairoi or “foot companions.” Alexander changed the name of the unit, at first to hypaspistai or “shield bearers,” and late in his reign again to argyraspides or “silver shields.” Under this final name the unit, three thousand men strong, played a dominant role in several battles in the wars of the succession, until the victorious general Antigonus the One-Eyed broke the unit up as having too much power and unpredictability. Recounting one of the battles this elite unit dominated, in 316, Plutarch gave eloquent testimony to the unit’s quality: he described the soldiers of this unit as athletes of war, who had fought in all the campaigns of Philip and Alexander, and had never suffered a reverse (Plutarch Life of Eumenes 16)

At his first great battle, against Bardylis and his Illyrians, Diodorus tells us (16.4.5) that Philip personally commanded the right wing of his army, having alongside him “the best” (aristous) of the Macedonians fighting with him; and he describes Philip with these “best men” as fighting heroically and forcing the Illyrians to flee. This suggests that Philip had already at that early stage begun to develop the elite unit we later hear of. The contemporary historian Theopompus of Chios, one of the greatest and most widely admired of the classic Greek historians, who spent years at Philip’s court, reports that: “from all of the Macedonians the largest and strongest were selected and formed the bodyguard of the king (Philip), and they were called pezetairoi” (Theopompos in Brill’s New Jacoby 115 F 348). Another contemporary of Philip, his Athenian opponent Demosthenes, also refers to the pezetairoi in his second Olynthiac Oration (at 17), mentioning their reputation as “marvelous” (thaumastoi) warriors who were outstandingly experienced in warfare. Three late antique lexical sources offer explanations for the term pezetairoi in Demosthenes’ speech here: they agree that the term refers to Philip’s personal guard, whom they characterize as “strong” (ischuroi) and faithful (pistoi). One of these sources, the Etymologicum Magnum, quotes as illustration a historical fragment (perhaps from Theopompus): “and taking of the Macedonians the so-called pezetairoi, who were picked men (apolektous), he (Philip) invaded Illyria.” Theopompus and Demosthenes thus agree that the pezetairoi were an elite unit of selected men who formed Philip’s personal guard in battle, and who enjoyed a reputation as outstanding and “marvelous” warriors. It seems certain, finally, that when Diodorus reports (16.86.1) that Philip fought his final battle, the battle of Chaeroneia in 338, in command of “selected men” (epilektous) who were certainly infantry (see Polyaenus 4.2.2), this means that Philip was as usual fighting surrounded by his elite pezetairoi.

Unfortunately our inadequate sources for Philip’s reign offer us no further insight into the development, organization, and use of this elite force. But under Alexander, we see this unit, under its new name as hypaspistai, functioning as the elite personal infantry guard of the king and spearhead of his army, as Philip had trained it to be. The pezetairoi/hypaspistai (later also called argyraspides, as noted above) usually fought as part of the phalanx, wielding the sarissa and other equipment of the Macedonian pikeman, and normally stationed on the right wing of the phalanx. But they were also trained to use other equipment when needed: on several occasions Alexander had them equipped as light infantry for operations requiring more speed and mobility: pursuit of enemy forces, fighting in mountainous territory, fighting alongside cavalry, and so on. It seems that they could also, if called upon to do so, adopt the heavier equipment of the southern Greek hoplite and fight as a hoplite phalanx; on one occasion Alexander had them mounted on horseback for an operation requiring particular speed of movement. They were, that is to say, superbly trained and versatile warriors, equally capable of fighting with any equipment and in any style they were called upon to adopt. As light infantry they were swift and tireless; as heavy infantry they spearheaded the phalanx in attack from their post on the right and were frequently chiefly responsible for victory; in any style or formation, they were the “marvelous” warriors of their reputation. They truly were the undefeated “athletes of war” that Plutarch called them, many of them continuing to fight and dominate the field of battle into their fifties and even sixties, until the unit was finally broken up by Antigonus in 316.

By the end of Philip’s reign, as indicated above, the pezetairoi numbered three thousand men: this is made evident from the sources for the first few years of Alexander’s reign, when the unit—now renamed hypaspistai—numbered three thousand and was commanded by Parmenio’s son Nicanor. The regiment, so to speak, of the pezetairoi was divided into three battalions (chiliades) of a thousand, each with its own sub-commander. One of the three was the particular personal bodyguard of the king, known as the infantry agema, units of which protected the king at all times, and which formed his personal guard in battle when he fought on foot. Philip often chose to fight at the head of his infantry, surrounded by his infantry agema and the rest of the pezetairoi, as he did at his first great battle against Bardylis, and again at the end of his reign at the Battle of Chaeroneia. Alexander, by contrast, preferred to lead the Macedonian cavalry in his major battles, though in other operations he frequently employed the pezetairoi/hypaspistai as his special force for all purposes, as already noted. The unit is probably best known to military history in its final avatar as the Silver Shields who dominated several battles in the wars of Alexander’s Successors, but they were more properly Philip’s elite infantry unit, organized and trained by him, and instrumental in helping him to turn Macedonia from the weak backwater Philip inherited into the greatest military power in the ancient world.

3. THE REFORMED CAVALRY STRIKE FORCE

Cavalry had always, as far back as our sources reach, been the strong suit of the Macedonians militarily, as explained in Chapter 1. The broad plains and plateaus of Macedonia were good horse-rearing country, and the aristocracy which dominated Macedonia socially and economically were enthusiastic horse breeders and riders. This is attested, as we have seen, by the popularity of personal names built on the Greek word hippos (horse): Philippos, Hipponikos, Hippolochos, Hippostratos, Hippias, Hippalos, Hipparchos, Hippodamas, Hippokles, Kratippos, and many others. In view of this it is particularly surprising to read Anaximenes (quoted above) suggesting that a ruler named Alexander had to “accustom the most notable to serve as cavalry” (the Greek verb for “serve as cavalry” is hippeuein which could also, even more unconvincingly, mean “to ride horses”). The truth is rather that the Macedonian aristocracy, as enthusiastic horse owners and riders, fought naturally from horse-back; and the Macedonian army from early times was made up predominantly of aristocrats and their retainers riding in at the ruler’s call to serve him as cavalry. The problem for Philip was that this cavalry force, though potentially excellent, was unreliable—because the commitment of the aristocrats making it up was unreliable—and incapable of directly and effectively engaging well armed infantry forces prepared to stand their ground in the face of cavalry charges.

What Philip wanted and needed was a cavalry force that was truly at his beck and call and loyal without question; and one that could be used effectively as a strike force even against well disciplined and heavily armored infantry forces. We have already seen in Chapter 3 the steps that Philip took to make the aristocracy, and thereby their retainers too, self-interestedly loyal to him as ruler, using the time-honored “carrot and stick” approach. The carrot was the granting of estates on newly conquered royal land, estates which could be repossessed if the grantee showed insufficient loyalty; the stick was the threat of destruction of disloyal aristocrats by Philip’s great infantry army, and the royal school at Pella where sons of the aristocracy, while being educated free of charge, also served as hostages for their fathers’ good behavior. Still, a cavalry made up largely of aristocrats and their retainers remained only contingently Philip’s to use. It is clear that he enormously expanded the cavalry by hugely increasing the part of the Macedonian cavalry made up of his own loyal retainers.

It will be recalled that at the start of his reign, Philip could call upon just six hundred or so cavalry for his crucial campaign against the Illyrians under Bardylis. Similar sized cavalry forces are attested as being commanded by earlier Macedonian kings such as Amyntas III and Perdiccas II. Evidently this is the kind of force, in terms of numbers, that could be raised by a traditional Macedonian ruler from his own retainers and his most loyal aristocratic hetairoi. By the end of Philip’s reign, he had available to him a Macedonian heavy cavalry force numbering at least 3,300: an enormous expansion of the Macedonian cavalry (and this doesn’t even count special forces of lightly equipped cavalry, some of whom were also Macedonians, discussed below in section 4 of this chapter). Evidently, as Philip conquered border territories and incorporated them into Macedonia, he settled many hundreds, eventually several thousand, men on large land allotments (small estates in effect) on condition that they maintained horses on part of their granted lands and served in the army as cavalry. We hear, for example, early in Alexander’s reign (when his army was still in all respects that created by Philip) of cavalry squadrons from several regions annexed to Macedonia by Philip: Amphipolis on the River Strymon, taken by Philip in 357; Anthemous in the north-west Chalcidice, a territory annexed to Macedonia at some point in the 350s or early 340s; and Apollonia in the north-east of the Chalcidice. Evidently several hundred men had been settled in each of these regions on substantial land allotments—so-called cavalry allotments—enabling them to be called up as cavalry whenever needed. These men were self-interestedly loyal to Philip because he had granted them their lands and raised them to the status of cavalrymen; the condition of keeping their allotments (which were revocable), and the status that went with them, was loyal service to Philip. We may reasonably estimate that as many as 2,000 of the 3,300 cavalry available to Philip at the end of his reign were men of this type: men raised to cavalry status by Philip, via revocable land allotments granted by Philip, who therefore were loyal retainers of Philip. With such a force of loyal retainers, Philip could overwhelm the following of even the greatest aristocrats if they should show disloyalty. This made the cavalry truly Philip’s cavalry, able to be called up and used by him as he saw fit without needing to pander to the whims of the great aristocrats.

Even such a truly loyal cavalry force, though, still retained the inherent weakness in battle that Macedonian (and other ancient) cavalry had always had up to this time. A horse will not willingly charge into an obstacle it sees no way to get over or through. Consequently, when cavalry charged a densely packed formation of infantry who did not turn to flight but stood their ground and maintained their formation in the face of charging cavalry, the cavalry horses would slow down and eventually pull up when they got close. The cavalry would be reduced to riding to and fro in front of the infantry formation, hurling missile weapons (which well equipped infantry would catch on or deflect with their shields) and insults. If and when the infantry force began to march forward in formation, the cavalry would be obliged to give ground before them, and eventually to flee. Cavalry, that is to say, were excellent against poorly organized and indisciplined infantry, which broke and ran when attacked by cavalry, enabling the cavalrymen to get among them and run them through from behind with spears or hack at them with swords. Pursuing and killing fleeing infantry was indeed what cavalry were best at and had most fun doing. A commander who was unwise enough to draw up his infantry with inadequate protection for their flanks would see enemy cavalry charge around to attack the infantry from the side or the rear; but that was a rarity as even minimally competent commanders confronting cavalry would know to keep their flanks protected. Beyond this, cavalry were useful for scouting and skirmishing before battle. To defeat well organized and disciplined infantry was beyond traditional cavalry forces.

In addition to all of this, cavalry forces were very hard to lead and command effectively. Traditionally, cavalry forces, like infantry forces, were drawn up in square or rectangular formations made up of lines of cavalrymen one behind the other. The commander would be stationed in the post of honor, on the far right of the front rank. From there, he could survey the field and enemy forces and decide when and where he wanted to charge. The signal to charge would be given by a trumpeter stationed with the commander, and the unit of cavalry would move forward, initially at a walking pace, in the direction the commander indicated. As they drew towards the enemy force they were attacking, the cavalry would speed up to a slow trot, and then go faster, trying to intimidate the enemy with their speed and hoping to break his morale and get him to flee. As the force moved faster, the lines of horsemen would inevitably become ragged, the thunder of hooves would drown out other sounds, and all but the few men closest to him would therefore lose touch with the commander, unable to hear or see, and so unable to follow, any other commands he might try to give. The commander, therefore, only truly had control of his force up to the initial charge; after that, it was largely every cavalryman for himself. If well trained and disciplined they would certainly try to remain as much as possible together and in formation; but it was effectively impossible for the commander to lead them in any complex or changing maneuvers.

This was unsatisfactory to Philip. He wanted to use his cavalry as a variable and effective weapon on the field of battle. He wanted the cavalry to be able to maneuver effectively under their commanders’ directions, and to attack enemy formations in an effective and destructive manner. Careful thought led him to conclude that the ineffectiveness of cavalry in battle was largely due to the formation in which cavalry was drawn up to fight: cavalry, to be effective, needed to get in among the enemy infantry, and they needed to be able to follow their commander and respond to his wishes as battle developed. The square or rectangular formation was well adapted to neither of these needs. Instead, Philip drew up his cavalry, and trained them to fight, in wedge-shaped formations (see ill. 11). The formation commander would ride at the apex of the wedge, with his second and third in command immediately behind him, ready to take his place if he was killed or incapacitated. In a wedge with the commander at the apex, the cavalry force rode wherever the commander rode, and so was able to follow him through whatever maneuvers and/or changes in direction he might undertake. In addition, with the front of the wedge only a few horses wide (the commander at the very front, two men behind him, three behind them, and so on), it would need only a small gap to open in an enemy formation for the cavalry wedge to charge at it, the first few horsemen pushing into the small gap. Once inside the enemy formation, the first cavalrymen in could “lever” the formation open by striking down at the enemy to either side, causing them to give way and thus widening the gap to allow more and more of the cavalry wedge to press in and eventually through the enemy formation. This would most often cause the enemy to turn and flee; failing that, the cavalry themselves would turn to attack the enemy from the side and rear. In this way, the cavalry could potentially be used as a genuine strike force in battle, even against well organized infantry.

11. The Macedonian cavalry wedge

(Public domain image: Quora—A.L. Chaisiri)

Thanks to this simple yet elegant and brilliant change in formation, Philip’s cavalry became indeed a fearsome strike force in his army and battles, best illustrated (as we shall see) in the battles the Macedonian army fought under Alexander’s leadership after Philip’s untimely death. At Philip’s death, when Alexander inherited his army, we learn that there were some 3,300 Macedonian heavy cavalry: Alexander took eighteen hundred with him when he crossed to Asia, and he left fifteen hundred behind as part of the home army under the regent Antipater. We know from various accounts of Alexander’s cavalry force in action that the Macedonian cavalry at this time were organized into squadrons (ilai) of about two hundred men led by officers named ilarchs, each of which was sub-divided into two sub-units of around a hundred. When we consider Antipater’s force of fifteen hundred cavalry in his home army, this creates a problem: fifteen hundred does not easily divide into squadrons of two hundred men. The solution is likely that the number two hundred is a rounded approximation: seven squadrons of 214 cavalrymen would total 1,498 men. It seems likely, therefore, that Antipater had seven squadrons of the Macedonian cavalry; and that another seven squadrons went with Alexander.

Of course Alexander had eighteen hundred cavalrymen, not fifteen hundred: what about the extra three hundred men? A key part of Alexander’s cavalry force was a special squadron named the ile basilike or “royal squadron,” commanded at the start of Alexander’s reign by an officer named Cleitus “the Black.” This is the cavalry force at the head of which Alexander was accustomed to station himself in battle, and which formed his cavalry bodyguard (agema) in battle, being thus the cavalry equivalent of the elite infantry agema, the pezetairoi/hypaspistai. It will be recalled that this elite infantry unit was stronger in numbers than a regular phalanx battalion (taxis), being three thousand strong instead of fifteen hundred. It seems certain that the royal squadron of the cavalry was likewise a larger formation than the regular cavalry squadron: three hundred men instead of around two hundred. The cavalry at the end of Philip’s reign and beginning of Alexander’s would, therefore, have been made up of fourteen regular squadrons of cavalry, each a little over two hundred strong; plus the special royal squadron of about three hundred men; for a total of fifteen squadrons in all. We saw above that the Macedonian infantry was organized likewise into fourteen taxeis of about fifteen hundred each, plus the elite pezetairoi/hypaspistai at three thousand strong. The organization of infantry and cavalry thus matched: fourteen taxeis of infantry recruited by region and fourteen ilai of cavalry likewise regionally recruited; plus two extra-strength elite selected units, the infantry pezetairoi/hypaspistai and the cavalry ile basilike.

The standard equipment of the Macedonian “heavy” cavalry is fortunately well attested. Thucydides already mentions that the Macedonian cavalry were “excellent horsemen and armed with breastplates” when telling of a campaign in 429/8 (Thucydides 2.100). But rather than literary descriptions, we can get a sense of the Macedonian heavy cavalry from two excellent depictions in art of Alexander’s time: the “Alexander Mosaic” in the Archaeological Museum at Naples (ill. 13), and the “Alexander Sarcophagus” in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul (see ill. 5). Besides the breastplates mentioned by Thucydides, Macedonian heavily armed cavalry wore kilts reinforced with leather strips, open-faced helmets, and short cloaks. Their main armament was a heavy thrusting spear some ten feet in length (about three meters) which might be wielded either overarm, as does the Macedonian cavalryman on the Alexander Sarcophagus (perhaps Antigonus the One-Eyed), or underarm as Alexander does in the Alexander Mosaic depiction. As secondary arms, the cavalry carried short (around two feet) thrusting swords carried under the left arm by a strap over the right shoulder. No shields were carried, as the cavalry relied on their breastplates for protection against missiles or thrusts from enemy weapons, while using the long thrusting spears to keep enemy warriors at a distance, and speed of movement to enhance their safety. Lacking saddles or stirrups, the cavalryman had need to be an excellent rider, as Thucydides attested Macedonian cavalry were. With the equipment mentioned and the training and discipline instilled by Philip in his new wedge formation, the Macedonian heavy cavalry came, along with the pike infantry, to dominate the battlefields of the near east.

4. THE SPECIALIZED LIGHT INFANTRY AND CAVALRY FORCES

The set-piece battle was the acme of ancient warfare, the event that ultimately decided the fate of a war. And with his powerful pike phalanx, usually spearheaded by his elite pezetairoi, and his vastly improved heavy cavalry strike force, Philip had created the crucial units that could win his battles for him. But warfare is not only about fighting battles; battles are not only characterized by the clashes of the “heavy” infantry and cavalry; and the great difference in mobility and speed of movement between infantry phalanx and cavalry could cause gaps in one’s battle formation that a swift-thinking enemy might exploit. Philip realized that he needed a variety of specialized forces to carry out peripheral but important tasks in his campaigns.

When an army sets out to undertake a campaign against an enemy force, especially if the campaign is to be conducted in enemy territory, it is of fundamental importance to the commander that he receive regular and reliable intelligence reports about the terrain to be traversed and, most crucially, about the whereabouts of the enemy force(s) and their number and make-up. Providing these intelligence reports was the task, in ancient warfare, of scouts: highly mobile and fast-moving soldiers who were sent out ahead and to the sides of the main army to spy out the lay of the land, look for enemy forces, capture and/or question enemy scouts or local civilians, and report back regularly on what they discovered. Such scouts were usually lightly equipped cavalry, mounted on horses with the qualities of speed and stamina. Heavy armor and weapons were not required by men whose job was not to fight so much as to see, hear, and report. Cavalry scouts wore only the lightest protection—padded jackets and light “target” shields strapped to the left forearm—and typically carried light missile weapons, mostly javelins, along with slashing swords for close in-fighting when necessary. In the Macedonian army of Philip and Alexander, units of light cavalry scouts, called prodromoi, are well attested: there were at least nine hundred of them in the army inherited from Philip with which Alexander invaded Asia in 334, for example, many of them recruited from Paeonia and Thrace.

Another crucial activity of soldiers on campaign is foraging for food supplies, i.e. stealing food by force from enemy lands and settlements. This necessity is dictated by the nature of overland transport in antiquity. Bulk goods such as large supplies of foodstuffs could only be carried in very slow-moving ox-drawn carts or mule pack-trains. These would slow down an army’s movement dramatically, and besides being very expensive such supply trains would also be vulnerable to enemy attack and need guarding. Philip wanted to be able to move fast, and preferred to keep his baggage-train as light as possible. The solution, adopted by all ancient armies, was that of “living off the land,” which means taking food from the indigenous population by force. This too required specialized soldiers. One could, certainly, in theory have the heavy infantry, in Philip’s case his pikemen, lay down their pikes and other equipment to go out foraging; but that would be a huge risk, if the enemy were to be able to pull off a surprise attack. The men of the phalanx had to stay in formation, whether it be column of march or line of battle, leaving the business of foraging to more mobile and less crucial troops. It was in fact the business of lightly equipped and hence fast-moving infantry, guarded during the actual foraging by mobile cavalry. Units of lightly armored javelineers, archers, and slingers would be sent out to do the foraging, covered and protected by the light cavalry prodromoi and other units of lightly equipped cavalry.

If and when the enemy was sighted and the decision was taken to fight a battle, battle was not joined instantaneously: it took time to shift the heavy infantry and cavalry from their encampment, or from the column of march, into a proper line of battle ready to fight. In the lead-up to battle, as the precise plan of battle was decided and the units of the army were drawn up in corresponding formation, there occurred a preliminary form of fighting known as skirmishing. Thousands of lightly equipped and highly mobile light infantrymen and cavalry would be sent forward to occupy space on the battlefield, to harass the enemy forces, to spy out the exact nature of the terrain on which the battle would be fought and the formation the enemy was adopting and report back on these, and to cover and protect the maneuvering of their own army into battle formation. This role of skirmishing is frequently referred to in ancient accounts of battles, but even more frequently simply passed over in silence as unimportant. It most certainly was not unimportant, however, and Philip had well organized and trained units of specialized light infantry equipped with missile weapons—archers, slingers, and javelineers—to carry out this role of skirmishing along with the lightly equipped cavalry. These special light infantry were often foreign troops recruited as allies or mercenaries. Archers, for example, often came from the island of Crete, since Cretans had long specialized in archery; and in the campaigns of Alexander (and so probably of Philip too) the best javelineers came from a tribe living just north of Macedonia proper, the Agrianians. Skirmishing was also a role played by the prodromoi, the cavalry scouts, and in addition we hear of a light cavalry unit named sarissophoroi or “lancers”: evidently very lightly armored cavalry who carried the same pikes as the heavy infantry to attack enemy infantry and cavalry skirmishers. In some cases it seems that the prodromoi and the sarissophoroi may have been the same soldiers, employed in different roles.

Finally, when battle was joined, the skirmishers would retreat to join the line of battle formed by the phalanx and the heavy cavalry, but their role in battle was not ended. There remained, in fact, three crucial roles for them to play. In battle, the phalanx, weighed down by their heavy and unwieldy pikes, moved very slowly. The heavy cavalry kept pace with the phalanx until an opening or disruption in the enemy line offered them a point of attack, at which they would then charge. It was the role of cavalry skirmishers and missile-firing infantry to harass the enemy line of battle as the phalanx moved slowly forward, to try to create such an opening or disruption, as several of Alexander’s battles reveal. When the heavy cavalry did charge, their swift advance would create a gap between them and the slowly moving phalanx. It was important not to allow an enemy force to move through this gap to attack the phalanx from the side and/or rear: light infantry units had the task of occupying this gap and protecting the phalanx from such an attack. Finally, units of light cavalry were routinely stationed out on the army’s flanks to harass and hold off any enemy force attempting an outflanking maneuver, unless the field of battle offered a natural barrier—a ravine, a wood, a hill—providing natural flank protection. In sum, in addition to their important roles during the campaign preliminary to battle, light infantry and cavalry units also played important, if secondary, roles during battle. These light forces might not actually win the battles, but they contributed in important ways to making victory possible. Finally, energetic pursuit of the defeated and fleeing enemy was crucial to make a victory decisive. Here too, the squadrons of light cavalry, especially the lancers (sarissophoroi), had an important role to play. Ensuring that he always had such lightly equipped units—infantry archers, slingers, and javelineers, and cavalry prodromoi and sarissophoroi, as we have seen—in sufficient numbers and in a high state of training and preparedness, was therefore crucial to Philip’s advanced form of warfare.

As indicated above, these specialized light infantry and cavalry forces were by no means always Macedonian. Philip recruited and used troops from a variety of sources for this purpose: Paeonians and Thracians are attested as light cavalry prodromoi, Cretans as archers, and Agrianians and other Thracians and Triballians as javelineers, for example. In the army Alexander inherited from Philip, we hear of seven thousand light infantry from the Balkan peoples, as well as one thousand Agrianian javelineers. But in addition to all these specialized light infantry and cavalry forces, we should also note an important source of specialized heavy infantry troops: mercenaries drawn from southern Greece. The world of the Greek city-states suffered from severe over-population in the fourth century, at least according to intellectuals such as the pamphleteer and educator Isocrates. Certainly southern Greece seemed to provide an almost inexhaustible supply of rootless young men willing to serve as soldiers for pay in this period. For Philip’s purposes, mercenaries, equipped as heavy infantry hoplites or at times as more mobile peltasts—soldiers who carried a lighter shield and had less body armor than the hoplites—had an enormous advantage: they were relatively much more expendable than his Macedonian troops. Losses in mercenary troops could always be replaced by fresh recruitment; and thanks to his enormous income in gold and silver from his mining operations, Philip could afford to employ thousands of mercenaries as he saw fit. These men supplemented his phalanx, easing the burden on native Macedonians for military services, and could be used for dangerous operations where losses might be higher than usual. Highly experienced and versatile, mercenary peltasts could also be used in all sorts of operations in which Philip might prefer not to exhaust his native military manpower.

5. THE SIEGE TRAIN

When ancient peoples did not dare to come out to confront an enemy army in battle, they often took refuge behind strong defensive walls built around their important settlement(s). Southern Greek hoplite forces had never shown much ability to cope with fortifications. Since such hoplites were citizen militia soldiers, who as citizens elected their generals before a campaign, and sat in judgement on them afterwards, southern Greek generals could not just command their soldiers however they saw fit. A general who suffered heavy losses, or treated his soldiers in a way they disliked, would face severe consequences after his term of office was over. Since taking fortifications by storm involved either operations that carried a high risk of sustaining heavy casualties (rushing up siege ladders to capture the enemy wall), or operations calling for heavy manual labor (constructing a siege ramp, or undermining the fortification walls) which Greek citizen warriors deemed work fit only for slaves, the reality was that armies of Greek hoplites confronted by well defended fortifications were reduced to camping around the enemy city and attempting to starve the enemy into surrender, which could take many months or even several years. Mostly Greek armies simply gave up in the face of well defended fortifications, unless they could find a way to get inside help: traitors, that is, to open a city gate.

Philip was well versed in using all the arts of persuasion, including bribery, to get his forces into enemy cities without needing to fight. But when inside traitors were not available to let his forces into an enemy city, Philip was not willing to see his military operations bogged down every time he was confronted with well defended enemy fortifications. He wanted to be able to capture enemy cities quickly. He had the advantage that, as king, he was much less dependent on his soldiers’ good will than were the generals of southern Greek city-state forces. Philip could order his men to take risks and perform labors that a city-state commander could not contemplate. In addition, since Philip employed many thousands of non-Macedonian troops—Thracians, Illyrians, mercenaries from southern Greece—who were relatively expendable, he could contemplate sustaining fairly high casualties with relative equanimity. Still, he would not want to sustain excessive losses, which would damage morale in his army. To attack fortifications effectively, the defenders on the wall had to be “softened up” first and/or the walls or gates needed to be breached, and that called for a specialized siege train.

Great advances in siege technology had been made in the Greek world early in the fourth century, especially in the forces of the Sicilian tyrant Dionysius of Syracuse. The key was the invention of the torsion principle: using ropes made of hair and/or animal guts which would be twisted with great force to create enormous dynamic tension. The sudden release of that tension could propel missiles—bolts of various sorts from smaller catapults; rocks and the like from larger ones—that could be used to force enemy soldiers on walls to duck down behind the walls for cover, enabling siege ladders to be raised against the walls and scaled; or else to batter the walls and/or gates in the hope of breaking holes in them. In the former task groups of highly trained archers firing at the tops of the enemy walls would help. In the latter task it would help to send forward, under cover, sappers who could dig under the walls, undermining and weakening them. In addition, more elaborate siege engines came to be developed. Mantlets covered with raw or wet ox-hides could provide cover for groups of specialists to drag battering-rams up to the gates and try to smash them open. Siege towers on wheels could be moved up to the walls and provide a platform for one’s soldiers to engage the enemy soldiers on the wall, attempting to cross over and win control of the wall. All of this siegecraft was still in development in Philip’s day: it was not until the very end of the fourth century and the early third century, in the army of Demetrius the Besieger, that Greek siegecraft reached its height. But Philip made sure to have the best siege technicians and machinery available in his day, and thanks to them his siege operations were mostly very successful.

With this siege technology and the highly trained and disciplined soldiers of his army, Philip captured a string of well fortified cities with relative ease and quickness: Amphipolis in 357, Pydna and Potidaea in 356, Abdera, Maroneia, and Methone in 354, Heraeon Teichos in 352, Olynthos in 348, to name a few. The list is a long one, and one might add Alexander’s capture of Thebes in 335, the year after Philip’s death. Not all of Philip’s sieges were successful: he failed to capture Perinthus and Byzantium in 340 thanks to the arrival of significant outside help for those cities’ defenses. But the principle is clear. As in every aspect of his warfare, Philip gave careful attention to his siege train, made it the most up-to-date and effective it could be, and achieved startling successes in his sieges as a result, enabling him to conquer territories and spread his control without being constantly stymied by strongly fortified cities and guard posts.

6. THE OFFICER CORPS

The point of all of the above was the creation of a new style of warfare: more elaborate, more disciplined, based on more thorough and effective training, aimed at creating swift and decisive successes through the controlled use of varied kinds of soldiers, with different armaments and specialties, operating together in a unified scheme of campaign and battle that not only won victories, but made them decisive, and not only occupied territories, but conquered them thoroughly and brought them firmly under control. But this kind of warfare, in which different specialized units of soldiers had to co-operate together in complex schemes of campaign and battle, was demanding. It did not only require a highly skilled commander who understood the potentialities of different types of soldiers and varieties of terrain, and could create and bring into effect plans that made the most of them. For varied units to co-operate together effectively in war, and especially in battle, each unit had to be led by a unit commander who understood the overall plan of campaign and battle, grasped the precise role of his own unit in it and its relation to other units, and could lead his unit in a disciplined way within the plan of battle, while having enough initiative to adapt his orders to the vagaries of battle and still stay within the overall battle plan. Where to find such skilled officers? Such officers are, of course, not so much found as trained. And in the course of his twenty-four-year rule, Philip trained one of the great officer corps in the annals of warfare, without whom Philip could not have achieved half of what he did achieve; and without whom Alexander—himself trained in the art of war by Philip—could not have conquered the vast empire he did conquer.

The full ability and expertise of this officer corps trained by Philip became apparent after the death of Alexander when, given free rein to operate on their own behalf, many of them carved out empires for themselves in two decades of extraordinary warfare (see Chapter 6 below). Men like Antigonus the One-Eyed, Eumenes of Cardia, Craterus and Perdiccas, Ptolemy and Cassander, Seleucus and Lysimachus, all in various ways showed military skills and leadership abilities of a very high order, in the case of Antigonus and Seleucus perhaps the highest. These skills and abilities did not come out of nowhere: they were developed and honed in decades of training and service under Philip, and then further honed assisting Alexander in conquering western Asia. The noted Hellenistic historian William Tarn, in the third chapter of his very adulatory biography of Alexander the Great (1948), says of these men:

Here was an assembly of kings, with passions, ambitions, abilities beyond those of most men; and, while he (Alexander) lived, all we see is that Perdiccas and Ptolemy were good brigade leaders, Antigonus an obedient satrap, Lysimachus and Peithon little-noticed members of the staff …

It seems to me that Tarn draws entirely the wrong lesson. The real point is not that Alexander dominated these men; it is that Alexander had, thanks to his father’s work, officers of such outstanding quality to work with. Alexander did not conquer the Persian Empire on his own. He had a group of brilliantly trained and highly professional officers to carry out and make effective his plans of battle, to co-operate with him in his campaigns and smooth out any problems, to carry out independent operations on his behalf when needed. Men who thoroughly understood the business of warfare and military leadership because they had learned their business in the same school as Alexander: Philip’s school.

Philip did not create his new army and officer corps on his own; he was fortunate enough to find two older men of outstanding ability to co-operate with him: Parmenio and Antipater. Both born a year or two either side of the year 400, they were around twenty years older than Philip, in their mid-forties already when he came to rule Macedonia at the age of twenty-four. It says a great deal for Philip that he very quickly identified these two men to be his key aides and supporters, and that he gained their loyalty and held it throughout his reign. Their importance to Philip is well illustrated by a couple of anecdotes recorded by Plutarch which show how they were viewed. Parmenio was throughout Philip’s career, and indeed most of the reign of Alexander, the senior officer after the ruler himself, in effect second-in-command of the Macedonian army and often trusted with independent commands: it was Parmenio, for example, who commanded a Macedonian army against the Illyrians under Grabus, and won a notable victory in 356. Of him Plutarch reports (Moralia 177C): “He (Philip) said that he counted the Athenians fortunate indeed, in that every year they could find ten men to select as generals (strategoi); for he himself in many years had only ever found one general, Parmenio.” The point being that the ten strategoi whom the Athenians elected every year were magistrates, who often had little real military skill; whereas Parmenio was a superb general on whom Philip could and did wholly rely. Antipater was also a very competent general, often trusted by Philip and Alexander with important commands; but he was above all the officer on whom Philip relied in diplomatic and administrative matters, usually serving as regent of Macedonia when the king was away on campaign. Plutarch reports (Moralia 179B): “Once having slept very late while on a campaign, he (Philip) said upon awaking ‘I slept safely, for Antipater was awake’.” In Antipater, that is to say, as in Parmenio, Philip had a senior officer in whom he reposed complete trust to be able and to do whatever was right and needed in his own absence.

These two, then, were the right-hand men who stood at the apex of Philip’s officer corps, considerably older than Philip himself and presumably assisting him in the recruitment and training of the rest of his officers. It may well be suggested, indeed, that they were to some degree co-inventors of the new army and military system with Philip, and so co-creators of Philip’s new Macedonian state. Besides these two very senior and crucial officers, there were also a number of important officers who were more or less Philip’s contemporaries, Antigonus the One-Eyed and Polyperchon being the best known of them. These men presumably learned Philip’s system of warfare by serving with and under Philip, as Philip himself created it and instituted it. They learned by doing, under Philip’s command; and perhaps also had some input into the process of developing the new army and military system. Most significant, however, in terms of numbers were the younger officers who were trained up by Philip from the inception of their military careers: such men as Craterus, Perdiccas, Philotas, Ptolemy, Leonnatus, Cassander, Lysimachus, Seleucus, Hephaestion, and—most crucially—Alexander himself. The ancient Greek term for education and training is paideia, and the young men, in their late teens, who were being trained by Philip in the business of warfare and officering, were known as his paides—often translated into English, via a medieval metaphor, as Philip’s “pages,” but in effect his trainees.

The paides of Macedonia have been assumed at times to be an old and traditional part of the Macedonian monarchy, a way for the sons of the king’s hetairoi to learn and show loyalty to the ruler, as noted in Chapter 1. But they are first attested under Philip, and seem more likely—as some scholars note—to be one of Philip’s many innovations. Young men in their late teens, around seventeen to nineteen years old, from the hetairos class would be taken into Philip’s service to learn to be a man, a Macedonian, and a leader. They attended the king at all times: at court, in the hunt, at the symposium, and on campaign, fighting as part of his entourage in battle. At court and at the symposium, they served as guards, messengers, and servers of food and wine. They learned the etiquette of the court and the symposium, and the business of the ruler. At the hunt, they served the king, ensured as best they could his safety, and participated in the stalking and killing of game while deferring to the king as principal hunter. Most importantly, on campaign and in battle they guarded the king and his tent, witnessing in that capacity the planning of marches and battles and the giving of orders. They might serve as messengers from the king to various units of the army and their officers, and they fought around the king in battle. In this way, they learned by observing and participating all the business of the army and the state, of leadership and command, of organizing and fighting. When they “graduated” from this paideia, the young men of whom the king approved might be appointed to the command of sub-units within the army, whether infantry or cavalry, and gradually progress into the command of larger units: taxeis of pikemen, ilai of cavalry, or specialized units of more lightly equipped soldiers, whether Macedonian, allied, or mercenary.

The result was that by the end of his reign, Philip had an officer corps of men who had thoroughly learned the structure of the army and its units, the system of warfare Philip had devised, and the business of commanding units of the army in accordance with the overall structure of the army and the plans of campaign and battle. Having been trained and selected by Philip himself, with the aid of his most senior officers as noted above, the king reposed full confidence in their ability to do what was required of them and their units in any military contingency, and they displayed their outstanding quality and capacities in the campaigns and battles of Alexander, and especially in the wars of the succession which followed on Alexander’s untimely death. It was officers of Philip who eventually took control of the lands conquered by the Macedonians under Philip and Alexander, and organized those lands into the great Hellenistic empires which dominated the near east for two centuries, and provided the setting for the establishment of Hellenistic civilization and culture.

7. THE SYSTEM OF BATTLE

Key to the success of the warfare of Philip and especially of Alexander was an advanced system of battle, invented by Philip, which used an army of combined arms in a smooth interlocking process to pin the enemy forces down, force them into battle, create disruptions in the enemy formation, and then exploit those disruptions to bring about victory, driving the enemy into flight and pursuing vigorously to make the victory decisive. Unfortunately our sources on Philip’s battles are for the most part completely inadequate, merely reporting the battles and Philip’s victories rather than describing them. But it is possible to reconstruct Philip’s last and most important battle and victory: the Battle of Chaeroneia in 338, whereby Philip secured his position as leader of the Greek world and set the groundwork in motion for the Macedonian invasion of western Asia. This battle illustrates Philip’s system of battle in its fully developed form, and was the model, I shall argue, for the great battles and victories of Alexander.

The Battle of Chaeroneia was fought in northern Boeotia, where the small town of Chaeroneia sits in a rather narrow pass between the River Cephisus and Lake Copais to the east and the foothills of Mounts Parnassus and Helicon to the west, athwart the main road from Phocis into Boeotia and beyond. Philip commanded a large Macedonian force of some thirty thousand infantry and two thousand cavalry. Opposing him was a combined southern Greek force made up of large contingents from Thebes and Athens, along with smaller allied forces from a number of other Greek states (Achaea, Corinth, Chalcis, Megara, Epidaurus, and Troizen). The allied southern Greek force had most likely about the same number of men as Philip, though Justin (9.3) suggested that the southern Greeks had far more men. Stationed astride the road facing north, the southern Greeks deployed with the Thebans on the right, their flank protected by the River Cephisus, and the Athenians on the left with their flank resting against the slopes of Mount Thurion, a projection from Mount Parnassus. Philip placed his pezetairoi on his right opposite the Athenians, with himself in command. Opposite the Thebans on Philip’s left were several phalanx battalions with, most likely, Parmenio in overall command, having Alexander with him sharing in the command in some way. We can only assume that the other southern Greek forces, unmentioned in actual accounts of the battle, were stationed in the center of the southern Greek line, between the Thebans and the Athenians.

Establishing exactly what happened during the Battle of Chaeroneia is not easy. Our main source, Diodorus the Sicilian (16.86.1–6), recounts the battle in a distinctly Homeric manner, focusing on the individual bravery of Philip himself and his son Alexander, and presenting the battle as a rivalry between the two of them to attain the victory by their personal efforts. What we can take from his account is that Alexander held an important command on one wing of the battle, facing the Theban contingent of the opposing army, while Philip commanded the other wing opposite the Athenians. On Alexander’s wing were stationed also “the most worthy commanders,” which must certainly include Parmenio. A force led by Alexander first succeeded in breaking through the enemy line, leading to a rout of the Thebans. Philip at that point, with his “picked men” (that is, his pezetairoi) around him, forced back the Athenians and routed them, over a thousand Athenians being killed and more than two thousand captured, which secured the victory. Thus far Diodorus’ account, which offers little detail on troop dispositions or the actual course of the fighting, while giving the impression that Philip and Alexander fought like Ajax and Achilles of old.

A number of other sources supplement Diodorus’ inadequate account, adding important details that flesh out what really happened. The second-century CE compiler of military “stratagems” Polyaenus tells us that Philip and his troops withdrew from the Athenians in a staged retreat, drawing the Athenians forward (Polyaenus 4.2.2); and that when the relatively raw Athenians grew tired, Philip had his more seasoned men attack and drive the Athenians back in rout (Polyaenus 4.2.7; also Frontinus Stratagems 2.1.9). Plutarch in his Life of Pelopidas (18) says that the Theban Sacred Band (an elite unit of three hundred soldiers), stationed on the far right of the Theban line, met the Macedonian phalanx face on and died heroically; in his Life of Alexander (9) Plutarch reports that Alexander was the first to “break the line of” the Sacred Band. The widely known story that the 300 men of the Sacred Band all died where they stood, which Plutarch affirms, surely indicates that this famous unit was surrounded. It’s worth noting here that the famous “lion of Chaeroneia” (ill. 12) which traditionally marked the grave of the Sacred Band has been excavated, and under it were found 254 corpses, which seems to confirm that the Sacred Band was indeed surrounded and annihilated.

12. The Lion Monument at Chaeronea

(Wikimedia Commons photo by Philipp Pilhofer)

Putting all of this together, the most widely accepted account of the battle goes as follows. In Philip’s system of battle it was the heavy cavalry who were the strike force charged with penetrating through gaps in the enemy line to attack the enemy from the rear. Though our inadequate accounts don’t specifically mention cavalry in the battle, it seems likely that Alexander—who first broke through the enemy line followed by companions (parastatai)—was in command of the bulk of Philip’s cavalry, evidently stationed on the left. Philip’s problem in this battle was that both flanks of the opposing army were protected by natural obstacles—the River Cephisus on his left, Mount Thurion on his right—and so could not be out-flanked. In order to break through the enemy formation, it would be necessary to create a significant gap, therefore. The disparate units making up the opposing line of battle offered an opportunity. By staging a retreat on his right, with his highly disciplined and reliable pezetairoi, Philip drew the Athenians forward. As the allied troops in the southern Greek center strove to maintain contact with the advancing Athenians, and the troops on the left of the Theban force moved forward to maintain contact with the Greek center, the southern Greek line became stretched. Since the main Theban force, confronted by the unmoving Macedonian pike phalanx under Parmenio, could not advance, a gap eventually opened in the Theban line. This was the moment Alexander had been ordered to exploit: when he saw the gap, he and his cavalry charged through it and turned to attack the Theban right wing from behind. Most of the Theban force fled, while the surrounded Sacred Band made their heroic stand and died. When Philip saw that his stratagem had worked and that the southern Greek right was in flight, he stopped the retreat of his forces and led them in a relentless attack on the tired Athenians, which routed them and secured the Macedonian victory.