6. Medallion of Emperor Alexander Severus showing portrait of Philip II of Macedonia

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image by Jastrow)

This man [Philip] ruled over the Macedonians for twenty-four years, and starting with the weakest of resources he built his kingdom into the greatest of the powers in Europe; taking over Macedonia when it was a slave to the Illyrians he made it the master of many great peoples and cities. Through his own excellence he received the leadership of all of Greece, the cities willingly subordinating themselves … Conquering in war the Illyrians, the Paeonians, the Thracians, the Scythians, and all the peoples neighboring on these, he took it upon himself to overthrow the kingdom of the Persians, and having sent forces ahead into Asia was in the act of freeing the Greek cities there when he was cut short in the midst of it all by fate. But he left behind so many and such great forces that his son Alexander required no further allies to bring about the destruction of Persian power. And Philip achieved all of this not by luck, but through his own excellence. For this king excelled in military shrewdness, in courage, and in brilliance of mind.

(Diodorus 16.1.3–6)

FEW IF ANY RULERS IN WORLD HISTORY CAN EVER HAVE TAKEN UP POWER under circumstances as difficult, indeed as outright disastrous, as those confronting Philip when he assumed the rule of Macedonia in the winter of 360/59. The defeat of his brother Perdiccas in battle against Bardylis and his Illyrians did not just result in Perdiccas’ death: it brought about the near total destruction of the Macedonian army. As we have seen, as many as four thousand Macedonian soldiers are reported to have died along with Perdiccas in this battle; many of the survivors were doubtless captured by the victorious Illyrians; and those who got away simply dispersed to their homes or some other refuge. The main army of the Macedonian state thereby ceased to exist in any useful sense, and the northwestern portion of Macedonia—Pelagonia and Lyncus at least, and likely some portions of Eordaea and Orestis, perhaps as much as a quarter of Macedonian territory in all—was occupied by the Illyrians and ceased temporarily to be part of Macedonia. That in itself constituted a major problem for the new ruler of Macedonia, but it was only a part of the difficulties Philip had to confront.

The defeat and death of the Macedonian ruler, and destruction of his army, was taken as an opportunity by various other neighbors and rivals of the Macedonians to extend their power at Macedonia’s expense, or to gain influence over Macedonia, or simply to loot and pillage in Macedonia to their hearts’ content. From the upper Axius valley to the north of Macedonia, Paeonian tribesmen invaded the Amphaxitis plain, looting, killing, and destroying as they came. From the south, an Athenian expedition of thirty ships and three thousand hoplites under the general Mantias appeared at Methone, convoying the Macedonian pretender Argaeus with a force of exiles and mercenaries, with the aim of installing Argaeus as a pro-Athenian puppet ruler over Macedonia. The Athenian goal was to control the Macedonian coast, ensuring access to Macedonian timber, and especially to win back control of the strategic former Athenian colony of Amphipolis, which was occupied at the time by a Macedonian garrison installed by Perdiccas. From the east, a large Thracian army gathered, probably commanded by the great Thracian ruler Cotys and accompanied by another Macedonian pretender named Pausanias, preparing to invade Macedonia to install Pausanias as a pro-Thracian puppet ruler. With the army destroyed, and enemy forces invading Macedonia from the north-west, north, east, and south, it looked as if Macedonia was simply falling apart, to survive at best as a partitioned region ruled by outsiders or by puppet rulers installed by outsiders. The prospects facing Philip seemed bleak indeed.

One must recall that at this time Philip was a young man of just twenty-four and untried in command, the son of a ruler who had been weak at best, and the younger brother of rulers who had been outright failures. There was nothing in the situation he faced or in his immediate past history to suggest that he had any prospect of being a successful ruler. Yet the task Philip set himself was not merely to deal with these immediate threats to Macedonia’s integrity and security, but to raise Macedonia to the position of a major regional power able to overmatch its regional rivals and threaten their security and integrity, rather than merely struggling to preserve itself against their attacks. And over the course of his twenty-four-year reign he was to succeed spectacularly in this self-imposed task; so spectacularly that it is a wonder he is not remembered as one of the great rulers in western history.

1. DEFUSING THE INITIAL CRISIS

Before Philip could even begin to work towards his major aims and goals, however, he had to deal with the immediate problems confronting his rule in particular and Macedonia in general: how he managed to deal with the multi-faceted and drastic crisis brought about by Perdiccas’ defeat would determine whether he would ever have the chance to strengthen Macedonia at all. In the event, it must be said that, his youth and inexperience notwithstanding, Philip’s analysis and assessment of the problems confronting him and the means available to him for coping with them was brilliant. In one short year he defused the crises and established himself firmly as Macedonia’s unquestioned ruler. How did he go about this?

The greatest difficulty limiting Philip’s possibilities was the lack of military force. The destruction of Perdiccas’ main Macedonian army did not leave Macedonia denuded of military manpower, by any means; but it gave Macedonians little incentive to join up with and serve under a ruler—Philip—whose prospects of success seemed bleak at best. What probably saved Philip in the beginning was having a secure base of power with some military force of his own, in the region of Macedonia—possibly Elimea as we have seen—over which his brother had placed him. He realized immediately, however, that he lacked the military force to confront Bardylis and his Illyrians in the north-west or the Thracian army approaching from the east. He correctly drew the conclusion that he must try to deal with these two threats by diplomacy and, if possible, bribery. Before he could do so, he had to establish himself as ruler of Macedonia, which presumably involved occupation of the new capital city established by Archelaus, Pella. At Pella, Philip would be at the center of things, controlling the Macedonian court and such administrative institutions as there might be. More importantly, it was no doubt at Pella that the royal treasury was located. That Philip seized and controlled this is nowhere stated; but in his first moves against Macedonia’s enemies he was able to engage in extensive “bribery” (giving of presents, to put it more neutrally), showing that he had significant funds at his disposal from the start. Where else but from the royal treasury could such funds have come?

Though our sources unfortunately offer little detail, it is clear that Philip initiated negotiations with Bardylis which resulted in some sort of truce at a minimum, perhaps an outright peace agreement. Bardylis was, perforce, left in control of the portions of upper Macedonia he had already occupied, since there was nothing to be done about it as things stood. In return for acknowledging Bardylis’ occupation, Philip got a respite from further Illyrian attacks. It seems likely that he also sent some sort of tribute payment and/or a promise to resume the tribute payments his father Amyntas had made to keep the Illyrians out of Macedonia. It is likely too that Philip’s marriage to the Illyrian Audata, probably a daughter or niece of Bardylis, occurred at this time, and as part of this negotiation. By Audata, his second wife, Philip eventually had a daughter named Cynnane. This shrewd but humiliating diplomacy, then, secured Philip’s north-western flank and bought him a period of quiet from that quarter in which to act.

The second great issue facing Philip was the threatened Thracian invasion from the east, led by Cotys with the aim of installing Pausanias as puppet ruler. Here again Philip was too weak to respond other than by diplomacy. Philip apparently met with Cotys in person, and by a mixture of promises and bribes persuaded the aged Thracian ruler to abandon his project. Cotys was no doubt promised that Philip would be a suitably friendly and humble Macedonian ruler, so that there was no need to install Pausanias; and cash gifts from Philip took the place of loot extracted by force. Pausanias was thus abandoned and, since nothing further is ever heard of him, likely either killed outright or handed over to Philip for execution. Very fortunately for Philip, Cotys died soon after this agreement was reached and his great Thracian realm was divided into three parts, each ruled by one of his three sons. These three much smaller and weaker Thracian realms offered a much lesser threat to Macedonia and Philip, particularly as Cotys’ three sons immediately entered into rivalries against each other, rivalries which Philip was eventually able to exploit effectively to his advantage.

The two gravest threats to Philip’s position as Macedonian ruler, and to the stability of Macedonia, were thus dealt with for the immediate time being by a mixture of diplomacy and bribery that was, while humiliating, effective and necessary. But such humiliating diplomacy could hardly help to ensure Philip’s position within Macedonia, as Macedonian ruler. He needed a show of strength to persuade the Macedonians that he could be more than a weak puppet of stronger outside powers. There remained two threats to be dealt with: the Athenians and their would-be puppet ruler Argaeus, and the Paeonians. Success in whichever threat he first confronted was absolutely necessary, and Philip therefore assessed which of these was the weaker and therefore the easier to deal with. He decided to confront Argaeus and the Athenians first, no doubt also in part because, in marching on the ancient capital Aegae and seeking to occupy it, Argaeus represented the more existential threat to Philip himself as Macedonian ruler. Consequently, he sent messengers to the Paeonian ruler Agis, to buy him and his raiders off for the time being with gifts and promises.

One thing Philip could not afford to do at this time was get embroiled in a major war with the Athenians: they were too powerful and he lacked the resources. His problem thus was to eliminate Argaeus without antagonizing the man’s Athenian backers too much. He quickly found the solution. The guiding principle to Athenian policy in the north Aegean for more than half a century had been to recover control of their former colony Amphipolis at the mouth of the River Strymon. They had founded this colony in 438/7 to give them a secure base from which to import the Macedonian and Thracian timber which was vital to their ship-building; but they lost control of it in 424 when the Spartan commander Brasidas induced the population to rebel and ally with Sparta. Since then the Athenians had made numerous unsuccessful attempts to recover control, and the installation of a Macedonian garrison in Amphipolis by Perdiccas was a key cause of Athenian hostility to Perdiccas and his brother Philip. Philip was so short of military manpower that he could not afford to maintain this garrison in any case: he needed those troops for other purposes. However, upon withdrawing the garrison from Amphipolis he made a virtue of necessity by letting the Athenians know that he supported their claim to Amphipolis, words that cost him nothing but won him the beginning of good will among the Athenians. He followed up by seeking a formal declaration of peace.

As a result of this, the Athenian commander in the north, Mantias, who had been sent to Methone with thirty ships and three thousand hoplite warriors, kept his Athenian hoplites at Methone and sent Argaeus to Aegae with only a small force of mercenaries and exiles, but with very few Athenians. The people of Aegae correctly assessed Argaeus’ chances of making himself ruler of Macedonia as negligible and refused to back him: they were perhaps angered too by Argaeus’ foreign backing. As a result Argaeus was obliged to retreat back towards the coast, and here—along the route between Aegae and Methone—Philip and his forces lay in wait. In a sharp battle, Argaeus’ force was decisively defeated. Most of the mercenaries were killed, as almost certainly was Argaeus himself (he is never heard of again). The surviving Macedonian exiles were arrested, but the Athenians among Argaeus’ force were carefully separated out and released without ransom and even with compensation for their losses. They presumably returned to Mantias at Methone and strengthened the impression that Philip was well disposed to Athens. Thus Philip had brought an end to the Athenian threat to his power by showing careful good will to the Athenians at little cost; had eliminated his rival Argaeus once and for all; and had shown himself a promising military leader by winning his first military engagement with decisive ease.

Now that the Macedonians saw reason to believe in Philip, he was able to begin recruiting further soldiers and prepare to deal with the remaining threat of the Paeonians. Here he again had some good luck: the Paeonian ruler Agis apparently died at this time, leaving the Paeonians with much weaker leadership. Philip launched a swift expedition up the Axius valley and inflicted a sharp defeat on the Paeonian tribesmen, who thereafter troubled Macedonia very little, and in fact came under Macedonian suzerainty. As the campaigning season of 359 drew to a close, Philip could congratulate himself on his achievements. He was now firmly established as ruler of Macedonia. By an astute, and as it was to prove highly characteristic mix of diplomacy, bribery, and victorious military engagement, he had calmed or seen off the various threats to Macedonia. The two pretenders Pausanias and Argaeus were no more; the Paeonians were cowed; the Athenians were considering a formal peace; the Thracians were quiet; and the Illyrian threat was contained by tribute and marriage alliance. The Macedonian people were duly impressed by their astute young ruler; but Philip knew that his achievements to date were only temporary. To win true security for Macedonia, and for his own rule of Macedonia, he needed a far greater military force than he could as yet command. Only a strong military force could truly secure Macedonia against the Illyrian threat, overawe the Athenians into staying out of Macedonian affairs, and keep the Paeonians and Thracians cowed. Having won himself a breathing space, therefore, Philip devoted the fall of 359 and the winter and spring of 358 to military recruitment, and to the creation of a new Macedonian army.

The process is described by Diodorus at 16.1–2: Philip traveled around Macedonia summoning the people to assemblies where he built up their morale and explained his plans. He recruited men, and re-organized the training and equipment of the Macedonian infantry. He himself, as ruler, provided his recruits with their new-style equipment and led them in a series of competitive training drills and maneuvers. He taught them a new style of close-order fighting he had devised, and he thereby “first established the Macedonian phalanx”. The exact meaning of Diodorus’ words, the kind of equipment and fighting Philip introduced, and the claim that he originated the Macedonian phalanx, are all controversial and have been the source of much scholarly debate. All of this will be examined in detail in the next chapter. But whatever the details of Philip’s work, one clear result is not in dispute: by the summer of 358 Philip was able to dispose of an army of ten thousand well trained infantry and in excess of six hundred cavalry. Such a military force is without precedent in recorded Macedonian history, except perhaps in the force Perdiccas had led to confront the Illyrians two years earlier. But Philip’s force seems to have been better trained and equipped than his brother’s had been, though its purpose was the same: to confront the Illyrians.

In the summer of 358 Philip invaded north-western Macedonia at the head of this army: he had never had any intention of allowing the Illyrians to control the north-western cantons of Macedonia permanently, the peace he had negotiated in 359 being merely an expedient to earn a respite in which to rebuild Macedonia’s army. Now that the army was ready, the peace was abandoned: when Bardylis sent messengers to Philip to protest his action and demand he adhere to the terms of the peace, Philip demanded that all Illyrian forces should withdraw from Macedonian territory. That meant a military confrontation, and Bardylis summoned his forces, which matched those of Philip almost exactly: ten thousand infantry and five hundred cavalry, according to Diodorus (16.4.4). The battle that occurred somewhere in north-western Macedonia was hard-fought. Philip himself commanded a picked force of elite infantry on the right of his phalanx, and instructed his cavalry stationed on the far right wing to charge around the Illyrians’ left flank and attack them from the rear. The Illyrians responded by forming themselves into a square, and put up a desperate fight. But Philip’s newly trained and organized infantry proved irresistible: the Illyrian resistance was overcome, and when they broke and ran Philip’s cavalry kept up a determined pursuit to kill as many fleeing Illyrians as possible and make the victory decisive. Some seven thousand Illyrians perished, we are told, a full two-thirds of the army engaged; and the Illyrians had no choice but to withdraw entirely from Macedonian territory.

Thus Philip had triumphantly overcome all the problems confronting Macedonia at his accession, and shown himself to be already the strongest Macedonian ruler since the founding ruler, Alexander I. At about this same time the Athenians agreed to a peace treaty with Philip, leaving him in full control of Macedonia and free from any external threat. He had at his disposal a victorious army that was the largest in Macedonia’s history, and the good will of his people whom he had saved from foreign invasion and occupation and the seeming dissolution of their state. As a result of this great victory, Philip could now embark on the process of state-building by which he hoped to turn Macedonia into the strongest state in Greece and the Balkan region, instead of one of the weakest.

The problems initially confronting Philip can be separated into three major sets of issues: there were the internal issues of Macedonia’s political and military weakness, its characteristic disunity and regional rivalries, and the disloyalty of members of the ruling Argead family and of other dynastic and aristocratic families; there were the constant threats of invasion and harassment posed by the barbarian peoples to Macedonia’s north and east—the Illyrians, Dardanians, Paeonians, and Thracians above all; and there was the issue of relations, often hostile relations, with the various Greek states and communities to the south of Macedonia, in the first place the Olynthian League and the Thessalians, and beyond them the stronger states dominating the rest of the Greek mainland—Thebans and Athenians most prominently.

The historical sources on which we have to rely for information were almost exclusively written by southern city-state Greeks (especially Athenians), and were overwhelmingly interested in relations between Philip and the city-states of Greece (especially Athens). This seriously distorts a basic historical reality: it is made to seem that Philip’s main preoccupation throughout his reign was relations with the Athenians and other city-state Greeks, when in point of fact Philip’s main concerns were rather with solving Macedonia’s internal problems, creating a properly unified state, and establishing Macedonian dominance over its barbarian neighbors, rather than the other way around. While we can trace the history of Philip’s relations with southern Greece, and especially the Athenians, in considerable detail, we get only occasional glimpses into how he dealt with the more crucial issues of internal weakness and barbarian foes. It seems most useful to treat each of these issues separately in turn, gathering all the information we can to present the best possible picture of how Philip went about dealing with each of these three sets of issues.

2. BUILDING A MACEDONIAN STATE

Undoubtedly the primary issue confronting Philip was that of establishing his rule over Macedonia, of unifying it into a coherent state under his control, and of strengthening it militarily, politically, socially, and economically. He began this project with an enormous source of strength: the large infantry army he had built and led to victory over the Illyrians gave him a secure power base no previous Macedonian ruler had at his disposal. The army was indeed the key to Philip’s state-building success, and to the nature of the Macedonian state he brought into being. I will defer detailed discussion of Philip’s military reforms, and of the Macedonian army, to the next chapter. Here, I shall discuss the unification of Macedonia, the proper subordination of the Macedonian aristocracy, the improvement of the Macedonian economy, and the creation of a Macedonian warrior “middle class” that formed the backbone of the Macedonian state and Macedonian power for several centuries to come.

One of the difficulties Macedonian rulers had faced throughout Macedonia’s history was the lack of unity of the country. As already described in Chapter 1, the core lands of Macedonia comprised two broad regions, generally referred to as lower and upper Macedonia; upper Macedonia was itself divided by mountain ranges into a series of sub-regions, each of which had its own local traditions and dominant families or clans. Within these upland sub-regions, or cantons as they are often called, local dynastic families had a tendency to take power and set themselves up as rivals or outright enemies of whatever Argead prince was ruling Macedonia at the time. Members of a dynastic family in Lyncus, for example, using the name Arrhabaeus and claiming descent from the old Bachhiad ruling clan of early Corinth, set themselves up at times as independent rulers of their region: the first Arrhabaeus was an enemy of Perdiccas II in the 420s (Thucydides 4.74–78 and 124–28); the second Arrhabaeus was an enemy of Archelaus (Aristotle Politics 1311b). The same is the case with the princely Derdas family of Elimea. We know of at least three princes of this name: the first was an enemy of Perdiccas II (Thucydides 1.57.3); the second probably assassinated the ruler Amyntas II (the Little), as we have seen, but was subsequently an ally of Amyntas III (Xenophon Hellenica 5.2.38–41); the third was an enemy of Philip, captured and killed at the sack of Olynthus in 347 (Athenaeus 10.436c, 13.557b). Further, Thucydides (2.80) tells us of a king of Orestis named Antiochus. Indeed, in an early treaty between Athens and Perdiccas II from ca. 440, preserved in an inscription (Inscriptiones Graecae I3.89), we find among those who swear to the treaty, along with Perdiccas himself and members of his family, four men with the title basileus (king) from upper Macedonia: Arrhabaeus, Derdas, Antiochus, and a fourth whose name is unfortunately lost.

To make Macedonia strong, Philip needed to fully integrate the upper Macedonian cantons into the Macedonian state, and to subordinate the dynastic families there once and for all. Derdas of Elimea was driven out of his territory and forced into exile: as we have seen, he fled to Olynthus and was there captured by Philip (and fairly certainly executed). Members of his family stayed in Elimea, but now as subordinates of the Argead ruler: we find an Elimiote Harpalus son of Machatas (a name used by the Derdas family) serving loyally under Alexander some years later. The princely dynasty of Lyncus had Philip to thank for driving out the Illyrian occupiers in 358: they perforce had to accept subjection to Philip. Three sons of Arrhabaeus II named Arrhabaeus, Heromenes, and Alexander remained quietly subordinate during Philip’s reign. The first two were executed by Alexander on suspicion of complicity in the plot to murder Philip; but we may suspect that they were really guilty of being perceived as potential threats to Alexander’s succession to his father’s power. The plain fact is that Philip’s new army, his victory over the Illyrians, and the many further victories that followed, made him far too formidable for the dynasts of upper Macedonia to challenge. They had to be content with subordination to Philip, and seek advancement in his service, or face being exiled and/or executed. The manpower of upper Macedonia was mobilized in Philip’s service: in the fully developed Macedonian army at the end of Philip’s reign and the beginning of Alexander’s, we find large battalions of infantry drawn from the regions of upper Macedonia as established segments of the Macedonian heavy infantry phalanx (see further Chapter 4, below). Their experience of successful military service, and the rewards they won as a result, made them loyal to Philip and his successor rather than to the old local dynastic families.

Thus a mixture of threats and rewards brought the dynastic houses of upper Macedonia to heel, and successful military service in Philip’s army and wars transferred the loyalty of the men of upper Macedonia to Philip, and integrated them into the Macedonian identity. The other great threat to Macedonian unity came from the Argead ruling family itself. For almost a hundred years, since the death of Alexander I in about 454, Macedonia was plagued by rivalries between competing branches of the Argead family descending from Alexander’s many sons. Members of the Argead family had not scrupled to ally themselves with great Macedonian aristocrats, with members of the upper Macedonian dynastic houses, or even with foreign powers such as the Olynthians, the Thracians, and the Athenians, in their quests to overthrow the ruling Argead and take his place. Not only for his own sake, but to create a stable and unified Macedonia, Philip could not allow that. He ruthlessly eliminated all members of the Argead family, therefore, except his own immediate heirs.

Right at the start of his reign, Philip eliminated the representatives of two rival branches of the Argead clan who were trying to make themselves ruler with foreign backing: Argaeus with Athenian support, and Pausanias with Thracian support. We have seen how Philip bought off their foreign support and ended these threats to his position. So far as we can tell, what remained of the Argead family after the deaths of these two pretenders, were Philip’s three half-brothers, Archelaus, Menelaus, and Arrhidaeus, and his nephew Amyntas son of Perdiccas. His three half-brothers were direct rivals to Philip for rule of Macedonia, and the eldest, Archelaus, seems already to have made a play for power in 359. What exactly happened is not known, but Archelaus met a violent end. The other two brothers fled and eventually found refuge in Olynthus, like Derdas; and like Derdas they perished at the sack of Olynthus in 347 (Justin 8.3.10). That left, besides Philip himself, only Amyntas alive of the Argead family. As his dead brother’s young son, Amyntas was Philip’s ward and, until he had sons of his own, his heir presumptive. Philip brought Amyntas into his own household and had him carefully brought up there, eventually along with his (Philip’s) own sons Arrhidaeus and Alexander. After all, Philip could not know whether his sons would survive childhood and prove to be suitable heirs. When Amyntas reached adulthood, Philip showed that Amyntas was very much in his thoughts as part of his family by marrying his own daughter Cynnane (by his Illyrian wife Audata) to Amyntas. At the same time, of course, this kept Amyntas firmly under his control and within his own immediate family circle; and Amyntas remained loyal as long as Philip was alive.

With potential Argead pretenders eliminated, the dynastic upper Macedonian houses thoroughly subjected, and upper Macedonia firmly integrated into the Macedonian state, the most dangerous obstacles to Macedonian unity had been dealt with. But there was also the problem of the Macedonian aristocracy more generally. The Macedonian aristocracy were primarily big landowners, who lived a life centered around horse-rearing, hunting, warfare, and the symposium (drinking party). Their estates were apparently worked by a kind of serf class, freeing them from the need to do any productive work. Besides the serfs, they had tenants and retainers who, in periods of warfare (endemic during most of Macedonian history) served their lords as cavalry (the retainers) and light infantry (the tenants). The Macedonian army before the time of Philip was, indeed, made up of the personal followings of various aristocrats added to the personal following of the ruler himself, who was a great landowner like the aristocrats. The military power of the ruler thus depended on the degree to which he was able to persuade members of the aristocracy to back him. Those aristocrats who did support a given ruler became his hetairoi (companions, a term going back to Homeric times), and served as his synedrion (governing/advisory council). The importance of the aristocratic role as hetairoi of the ruler is illustrated by the existence of a major annual festival celebrating it, named the hetairidia. One should also note the naming of a set of “barons from lower Macedonia” (Errington 1990 p. 15) as guarantors of the peace treaty with Athens preserved in Inscriptiones Graecae I3.89.

Strong rulers were those who succeeded in uniting the vast majority of the aristocracy behind them; weak rulers were those who failed to do this. And there was a clear tendency in early Macedonian history (before Philip II, that is) for aristocrats to rally behind rival pretenders to the throne (that is, those opposing the sitting ruler), or even, as in the case of Ptolemy of Aloros in the early 360s, to set themselves up as rivals to the ruler. A stable and successful Macedonia required bringing the aristocracy to heel and ending their divisive ways. Philip’s creation of a new and powerful infantry army beginning in 358 gave him an unprecedented position of strength from which to deal with the aristocracy: no aristocratic landowner, no matter how wealthy and powerful, could compete militarily with Philip’s army. Any aristocrat, or even coalition of aristocrats, who set themselves up against Philip faced the prospect of a visit by Philip’s new Macedonian phalanx, and possible annihilation. That intrinsically gave the Macedonian aristocracy a strong incentive to demonstrate loyalty to Philip; but this was a negative incentive. Philip gave them a positive incentive too. As Philip’s new army campaigned around the southern Balkan region, winning battles and wars, Philip seized lands from defeated enemies and incorporated them into Macedonia. By traditional notions of “spear-won land,” these conquered lands belonged to the ruler and were his to dispose of. Philip granted to favored aristocrats additional estates of conquered land, vastly increasing their wealth. But they did not own these additional estates outright: instead they had revocable possession, and the condition of maintaining possession was to continue demonstrating loyalty to the ruler, to Philip that is. According to the contemporary historian Theopompus, Philip’s eight hundred or so hetairoi at the height of his reign held, thanks to this policy, as much landed wealth as the ten thousand wealthiest men from the rest of Greece combined.

The aristocracy were thus firmly subordinated to Philip’s rule by a carrot and stick approach: the carrot was the gaining of vast new estates to increase their wealth; the stick was the threat of losing those estates and, in the extreme, of being annihilated by Philip’s army. But Philip was not satisfied with just this: he pursued two further policies to increase his control of the aristocracy. In the first place, Philip invited leading men from all the rest of Greece to move to Macedonia and enter his service, becoming his hetairoi, and like the native aristocrats being rewarded with large revocable estates of conquered land. These new, immigrant hetairoi owed their wealth and status entirely to Philip’s favor, and were self-interestedly loyal to Philip as a result; they thus formed a powerful block of support that Philip could use against any disaffected Macedonian aristocrats. Some famous examples of such new hetairoi are Eumenes of Cardia, the Cretan Nearchus, Erigyius of Mitylene, and Medeius of Larissa.

In addition, and very importantly, Philip was interested in binding the sons and grandsons of the aristocracy to his service, making them not only loyal followers, but useful ones. To this end he established a school at Pella and invited the aristocracy of Macedonia to send their sons there, to receive the best education available (essentially an Athenian education) at Philip’s expense. Naturally, the invitation could not be refused: an aristocrat who declined to send his son(s) would signal thereby his lack of trust in Philip and be suspected of disloyal designs, perhaps of outright plans to rebel. While this genuinely offered the aristocracy an excellent free education for their sons, and of course fostered mutual familiarity and relationships among the sons of the aristocracy, no one was unaware that this school also meant that the sons of the aristocracy were now under Philip’s control. They served effectively as hostages for the good behavior of their fathers, and were educated in the way Philip judged best. This latter is a crucial point: Philip needed the aristocracy to feel true loyalty and commitment to the Macedonia he was building; and he also, crucially, needed capable officers for the army and military system he was developing. While literacy skills, and a grounding in literature, music, and rhetoric were doubtless the basics of the education provided, physical training, and especially military training, obviously played a major role too, especially in a special system of what might be called higher education.

When the boys being educated reached their late teens, roughly their eighteenth year, they were inducted into a group called the paides (literally youths, in this context) who served for some two years a kind of military apprenticeship in the immediate entourage of the ruler, in this case Philip himself. They waited on Philip, provided personal service and attendance, and fought directly with and under him in battle, as a kind of guard in addition to the regular royal bodyguard. Though we never hear of it before the time of Philip, the institution of the paides may have been an old and traditional part of Macedonian society: it will no doubt have been normal for the teenage sons of the ruler’s hetairoi to serve him in this way. But Philip certainly placed a new and more thorough emphasis on the paides, making service in this group an integral part of the passage from youth to manhood for the Macedonian aristocracy. For by having the sons of the aristocracy in his personal service and entourage, he could inculcate loyalty to himself and personally train them in the business of serving as officers in his new-style army and military system. The success of this training system is well seen in the officers of Alexander’s army, all of whom had, like Alexander himself, grown up in service to Philip and in Philip’s training system. It is no coincidence that so many of Alexander’s officers—the likes of Ptolemy, Craterus, Seleucus, Cassander, Lysimachus, and others—proved to be highly capable and successful generals: they had learned the necessary skills in the same school as Alexander himself, under Philip.

Another matter that required development and improvement under Philip was the Macedonian economy: a state is at bottom only as strong as its economy allows it to be. As I pointed out in Chapter 1, Macedonia had the potential in land, manpower, and natural resources such as timber and metals to be a wealthy and powerful society. This potential had never been fulfilled, in part due to the constant pressure on Macedonia by invading forces from the Balkan region, looting and pillaging and at times occupying swathes of Macedonian territory; in part due to the occupation of the Macedonian coast and harbors by southern Greek colonies which came to be dominated by the Athenians, giving Athens control over Macedonian trade; and in part due to the archaic social system of aristocratic dominance and the concomitant disunity. Philip’s successful military activity drove invaders out of Macedonia and, by extending Macedonian control over neighboring territories, provided an era of peace and security hitherto unknown for the Macedonians themselves. It also enabled Philip to seize control of the harbors on the Macedonian coast—Pydna, Methone, Therme—and assert his own control over trade between Macedonia and the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean world. And of course Philip had fully unified Macedonia and brought the aristocracy to heel, creating the conditions for socio-economic advancement within Macedonia.

Before the time of Philip Macedonia had virtually no cities: there was the old seat of the Argead clan, Aegae, though it seems to have been little urbanized; and there was the new capital Pella, founded by Archelaus. Philip fostered the development of cities, both within Macedonia proper and in the extended borderlands he added to Macedonia. In Macedonia, cities were developed around such settlements as Dion, Beroea, Edessa, Europus, Heracleia Lyncestis, and Argos Oresticon, while existing cities like Pella, Pydna, Therme, and eventually also Amphipolis were strengthened. When Philip extended the border of Macedonia westward, annexing western Thrace as far as the River Nestus, he re-founded the settlement of Crenides as Philippi and strengthened it with Macedonian colonists. When he further annexed south-central Thrace up to the Hebrus valley, he founded the city of Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv) and established fortified military settlements at Beroi (modern Stara Zagora), Kabyle (Kabile, near Yambol), and Bine. To strengthen his southern expansion into Thessaly he established a Macedonian colony at Gonnoi on the Thessalian side of the Vale of Tempe, and he may have established Macedonian garrison-settlers elsewhere in Thessaly too, for example at Oloosson. These are the foundations we know of: there may well have been more. As we have seen, Alexander was later to claim that Philip “made you (i.e. the Macedonians) city-dwellers and organized you with proper laws and customs” (Arrian Anabasis 7.9.2).

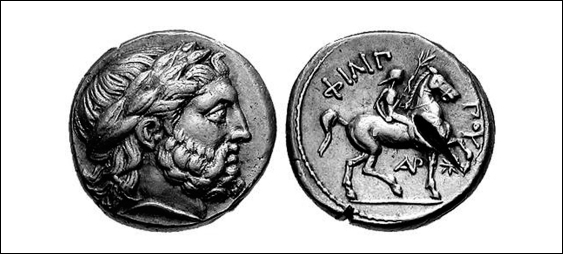

An effect of this urbanization was, of course, economic development. We learn further that Philip had marshes drained and lowland forests cleared for agriculture. He extended and improved Macedonian mining operations, for example making the gold and silver mining in the Pangaeum region around Philippi much more thorough and efficient, eventually deriving an annual income of a thousand talents (a stupendous sum: the Athenians at the height of their power in the fifth century received less than half of that in tribute payments from their subject-allies) from mining operations there. This enabled him to produce an abundant, well-made silver coinage to fund his activities (see ill. 7). Since our sources are simply not interested in economic policy and development, there is not much to be added to this in detail. But overall it is clear that Philip revolutionized Macedonian economic life. The establishment of internal peace and security, the process of urbanization, the development of trade through properly controlled and improved harbors, the more thorough and efficient exploitation of timber and metals, above all the clearing and draining of land and extension of agriculture: all of this made Macedonia a far wealthier land and the Macedonians for the first time a prosperous people. Again to quote the words attributed to Alexander: “When Philip came to power over you, you were indigent wanderers, most of you wearing animal hides and herding a few sheep in the mountains … he gave you cloaks to wear instead of hides, brought you down from the mountains into the plains …” (Arrian Anabasis 7.9.2). It is for these reasons that Philip was fondly remembered by the Macedonians for generations afterward as the father of his people.

That brings us to Macedonia’s most important resource: the Macedonian people. In some sense everything Philip did was in service to the Macedonian people, but not to all of them evenly. The impression we get of the Macedonians before Philip is of a powerful aristocracy, a large serf class working for the aristocrats, and not much in between. This is why Macedonian military strength had always been based on cavalry supplied by the aristocracy, with infantry forces few in number: usually not more than perhaps four or five thousand, who were ill-trained, ill-equipped, and undisciplined. In realizing that a strong and secure Macedonia required a large and effective infantry army, Philip knew that he needed a free warrior class of “citizens.” Much of his reforming activity was aimed in large part at bringing that warrior class into existence. That he succeeded is made clear by the following army statistics. At the beginning of his reign, in 358, absolutely needing a victory over the Illyrians and therefore mobilizing the largest force he could muster, Philip managed to gather an army of ten thousand infantry and six hundred cavalry. Just after the end of Philip’s rule, when his son Alexander invaded the Persian Empire in 334 with what was still Philip’s army, we learn that twelve thousand Macedonian infantry and eighteen hundred cavalry marched with Alexander, while another twelve thousand infantry and fifteen hundred cavalry were left behind in Macedonia for home defense. The number of available infantry was thus twenty-four thousand—two and a half times those available in 358—while the number of the Macedonian cavalry had multiplied more than fivefold, from six hundred to three thousand three hundred. Moreover, despite the fact that Alexander did nothing during his thirteen-year reign to supplement Macedonian manpower—instead siphoning it off constantly for his wars of conquest—we find that at the end of Alexander’s reign there were more than fifty thousand Macedonians under arms, another near doubling of the number. This growth seems to have been entirely due to the policies put in place by Philip.

7. Tetradrachm coin of Philip II from Amphipolis mint

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image by Jastrow)

How did Philip achieve this spectacular growth in military manpower? To some extent this was an effect of the social and economic policies outlined above: the establishment of peace and security, the development of cities and trade, the expansion of agriculture and consequent growth of wealth, will all have had beneficial demographic effects, raising the birth rate and the survival rate of infants, and thus increasing the Macedonian population. But there was clearly more to it than that: Philip had specific policies aimed at developing the “warrior class” I have spoken of. It is not at all clear how much of a population of free farmers, herders, and small craftsmen, suitable for mobilization and training as a close-order infantry phalanx, there may have been in Macedonia before the time of Philip. Our accounts of Macedonian warfare, with its lack of any well trained infantry formations, suggest that any such class of free men cannot have been very large, or much motivated to fight for Macedonia’s rulers. By various means Philip extended this segment of the population and established in them a warrior spirit and pride in Macedonian identity. One of his policies was population movement, or resettlement. Within Macedonia, it appears, settlers were moved from lower Macedonia to upper Macedonia, and vice versa, partly no doubt with the aim of further unifying Macedonia. But one suspects, given Philip’s need for military manpower, that some at least of these settlers may have been taken from the serf population, becoming free men eligible for military recruitment in the act of being resettled. More significantly, as new territories were added to Macedonia—for example the Chalcidice, and western Thrace between the rivers Strymon and Nestus—Macedonians were settled within these territories, becoming well-to-do farmers and serving as a permanent garrison and Macedonianizing element; but also, themselves and their sons, becoming eligible for recruitment into infantry service.

In such ways Philip clearly enormously expanded the segment of the population available for military service, as the army numbers presented above prove beyond doubt. Most crucial were the land clearing and consequent expansion of agriculture, the urbanization, and the resettlement program, particularly in the newly conquered territories. All of this gave Macedonia for the first time, so far as we can tell from our sources, a large class of men suitable for service in an infantry phalanx. Calling these men up for repeated spells of infantry training and service; teaching them through weapons drills and route marches; leading them on successful campaigns in which they won battles, conquered lands, and acquired booty; all of this fostered in this newly well-to-do and independent class of men the requisite warrior spirit and a fierce pride in their Macedonian identity that simply had not existed before. And it is worth noting that not all of these men were ethnically Macedonian to begin with: Philip certainly welcomed southern Greeks into Macedonia and into his service; it is quite likely that no small number of Paeonians, Thracians, even Illyrians living in the border territories absorbed into Macedonia were Macedonianized by the resettlement process and became part of Philip’s warrior class.

The overall effect of Philip’s reforms on the Macedonian people is well illustrated by a characteristic anecdote revealing how Philip was remembered by his people. Plutarch in his “Sayings of Kings and Commanders” (Moralia 179d) reports that an old lady was importuning Philip to deal with a problem she had, and when Philip replied that he had no time to look at her case just then she responded, “Then you should stop being king!” Instead of being angry at this, Philip accepted the rebuke and dealt right then not only with her issue, but with those of other petitioners too. The point of the story is not that it actually happened just so, but that it was a story told about Philip by his people; that is, that this story reveals how the Macedonians viewed Philip, as a ruler who genuinely cared about his people, was approachable, and had their best interests at heart. By way of contrast, Plutarch tells another story of a later Macedonian ruler, Demetrius the Besieger, who instead of dealing with his people’s petitions properly threw them away, not wanting to be bothered (Plutarch Life of Demetrios 42). Plutarch says that, seeing this, the Macedonians were infuriated and reflected on “how accessible Philip had been and how considerate in such matters.” Thus Philip was fondly remembered by the Macedonians for many generations as a true father to his people, the epitome of what a good ruler should be.

3. SUBDUING THE BARBARIAN BALKAN REGION

If properly unifying and strengthening Macedonia internally was Philip’s number one priority, the second without a doubt was securing Macedonia against invasion, raiding, and even conquest by its barbarian neighbors to the north-west, north, and east. Throughout his reign, from his first days in power until almost his last, he campaigned again and again against Illyrian, Dardanian, Paeonian, Agrianian, Triballian, and Thracian peoples living in the Balkan region, roughly in modern-day Albania, Montenegro, Serbia, and Bulgaria. His ultimate success in this project of securing Macedonia is illustrated in maps 2 and 3, showing the extent of Macedonian power and control at the beginning and end of his rule. We have already seen above that two of Philip’s earliest campaigns, in 359/8, were against invading Paeonian and Illyrian forces in northern and north-western Macedonia, giving him two crucial early victories. He continued as he had begun.

To start with the Illyrian front, the defeat of Bardylis and his Dardanian Illyrians changed the balance of power among the Illyrian tribes: we hear of a certain Grabus becoming the strongest Illyrian ruler, and extending his power all the way to the Macedonian border. Grabus is perhaps a title rather than a name: he apparently ruled over a tribe called the Grabaei. Grabus recognized a serious threat in the rising power of Macedonia, and in 357 to 356 joined up with a northern coalition aimed at defeating Philip. The initiative seems to have come from a Thracian ruler: Cetriporis, son of Berisades and grandson of the great Thracian ruler Cotys, ruled over the westernmost of the three chieftaincies into which Cotys’ great kingdom had been divided at his death, sharing thus a border with Macedonia. He persuaded the Paeonian Lyppeius, son of Agis, and the Illyrian Grabus to form a grand northern alliance. While Philip himself moved east in 356, marching up to the River Nestus, founding Philippi, and then going to aid his allies the Chalcidians in the capture of Potidaea, he sent a large Macedonian force under Parmenio to deal with Grabus and his Illyrians.

Parmenio was from a great upper Macedonian family, most likely from Pelagonia, and so knew the Illyrians and their style of fighting well. He was some fifteen years older than Philip, and was one of Philip’s earliest supporters—impressed no doubt by Philip’s victory over Bardylis—and most important aides. The Athenians every year elected ten magistrates named strategoi, that is generals: Philip supposedly once jokingly congratulated them on finding ten generals every year, when he himself had only ever found one general in his lifetime: Parmenio. The point is that Parmenio was a capable and loyal general on whom Philip could rely to take command in campaigns he himself could not oversee: usually facing multiple threats in different regions, Philip needed reliable and loyal generals, and Parmenio was the best of them. In the summer of 356, Parmenio and his forces inflicted a serious defeat on Grabus’ Illyrians, news of which reached Philip just after he captured Potidaea in (it seems) early August.

The defeats inflicted on Bardylis and Grabus enabled Philip to annex to Macedonia Illyrian borderlands to the north and west of Lake Lychnitis (Ohrid), in the territories of the Dassaretae and the Deuriopi, perhaps also the Bryges further north (see map 3). This gave upper Macedonia a secure buffer zone against future Illyrian attacks, as well as opening up lands for Macedonian settlement. The expanded and enhanced Macedonian border, at Illyrian expense, did not of course end Illyrian hostility. Our sources unfortunately tell us little about Philip’s Illyrian warfare, but we do hear of further campaigning by Philip against Illyrians in 350, in 345 against the Illyrian dynast Pleuratus, and in 337 against another Illyrian dynast named Pleurias. The last was Philip’s last major campaign before his sudden assassination in 336, so that Philip ended his rule as he began it, with successful warfare against the Illyrians. It is noteworthy that whereas down to 358 warfare between Illyrians and Macedonians invariably occurred in Macedonia, as a result of Illyrian invasions, after 358 it was Philip’s Macedonian forces that invaded Illyrian lands, campaigned successfully there, and annexed Illyrian territories.

Whereas the Illyrians were a serious threat to Macedonian security, the Paeonians were more of a nuisance: inveterate raiders and looters, but nothing more. Our sources tell us even less about Philip’s pacification of Paeonia than of his Illyrian campaigns, but the result is clear. The campaign in late 359 (or possibly early 358?), shortly after the death of the Paeonian ruler Agis, ended any threat to Macedonia in that region for some years. In 356, however, Agis’s son and successor Lyppeius joined—as we have seen—with Cetriporis and Grabus in the northern coalition against Philip. How he was dealt with we are not told, but it appears that he once again became a problem to Philip in 353, after Philip’s defeat in Thessaly by the Phocian army of Onomarchus. Once again, we hear nothing of how Lyppeius and his Paeonians were dealt with, but four years later Isocrates (5.21) remarked that Philip had subjected the Paeonians. It appears that Paeonia was annexed as a tributary territory and settled with a few Macedonian fortress-colonies for security; but Lyppeius was seemingly allowed to remain as ruler, for we hear of his successor Patraus still ruling the Paeonians under Alexander in the late 330s (Demosthenes 1.13). In 340 Alexander, then sixteen years old and serving as regent of Macedonia during Philip’s absence in eastern Thrace, led an army west of Paeonia to engage the Maedi in the upper Strymon valley, whom he defeated and where he founded a fortress-colony named Alexandropolis after himself. Thus the boundary of Macedonia to the north was extended up the Axios and Strymon valleys to defensible and fortified mountain frontiers.

The Thracians represented a threat similar to that of the Illyrians: major Thracian incursions led by kings such as Sitalces in the time of Perdiccas II and Cotys at the start of Philip’s reign showed how unsatisfactory Macedonia’s eastern frontier was. It is no surprise, therefore, that as soon as Philip had established his rule over Macedonia securely, he began to extend his power eastwards into Thrace, at the expense of the Thracian successors of Cotys. At the death of Cotys, his kingdom had been divided among his three sons Berisades (western Thrace), Amadocus (central Thrace), and Cersebleptes (eastern Thrace). This created a weakness Philip was quick to exploit. It also helped that Berisades, whose westernmost Thracian realm bordered on Macedonia, only ruled for a year or two before dying and being replaced by his son Cetriporis, obviously a younger and less experienced ruler. It was Cetriporis who, by organizing the anti-Macedonian “northern Alliance” with the Paeonian Lyppeius and the Illyrian Grabus about 357/6, provided the occasion for Philip to begin his decades-long series of interventions in Thrace.

Philip’s first move was along the coast of the Aegean, crossing the River Strymon and marching east. He had received an appeal from the Thasian colony of Crenides in the rich Pangaeum mining district. The people of Thasos had for generations had an interest in the mineral resources on the mainland across from their island, founding the colony of Neapolis (modern Kavala) on the Aegean coast and, much later around 360, the colony of Crenides inland in the Drama plain. The aim was to exploit the silver and gold mines of the region, but the Thasians lacked the resources to support the colony, which came under immediate pressure from the surrounding Thracians. Philip now provided the support the Thasians could not, taking over Crenides and refounding it with an addition of Macedonian settlers and the new name Philippi, after himself. The new settlement was fortified with strong walls, and the surrounding Drama plain was drained for agriculture, enabling the Philippians to feed and defend themselves. The silver and gold mines of Pangaeum were then exploited with vastly greater thoroughness and efficiency than ever before, bringing Philip a huge annual income and enabling him to strike a plentiful and attractive new coinage (see ill. x). Meanwhile Cetriporis saw his northern allies, the Illyrians and Paeonians, soundly defeated, leaving him powerless to deal with Philip. An alliance with the Athenians, always interested in controlling the north Aegean coast as much as possible, proved no help, and he had to acquiesce in Philip’s takeover of the Drama plain and the Thracian coast as far as the River Nestus.

In subsequent years, 355 and 354, Philip further extended his power along the north Aegean coast, more at the expense of the Athenians than of the Thracians. He had already seized Amphipolis at the mouth of the Strymon in 357, despite his earlier promise to the Athenians to regard it as theirs. The city was reinforced with a large contingent of Macedonian colonists and rapidly Macedonianized. The founding of Philippi posed a threat to Neapolis on the coast: it was clearly desirable for whoever controlled the Drama plain also to control Neapolis, the region’s outlet to the sea. Neapolis was seized by Philip in 355, apparently, and in 354 he moved further east to capture the southern Greek colonies of Abdera and Maroneia (see map x). In taking these coastal cities, Philip was posing a potential threat to Amadocus, the ruler of central Thrace whose territories lay immediately inland. Amadocus fortified the passes leading inland from the coast and barred Philip’s further progress. All the same, Philip was able to negotiate an agreement with Cersebleptes, the easternmost and strongest of the three Thracian rulers who had succeeded Cotys. That represented a threat sufficient to keep Amadocus quiet for the time being.

This agreement did not last long: in 353 Philip suffered an unexpected defeat in Thessaly, as we shall see, and that led Cersebleptes to transfer his allegiance to the Athenians, Philip’s enemies since his annexation of Amphipolis. Busy in Thessaly, Philip was not able to respond in Thrace until the fall of 352; but then a near two-year campaign beginning in October or November of 352 saw him considerably strengthen his position in Thrace. Allying himself now with Cersebleptes’ rival Amadocus and the Athenians’ enemies Perinthus and Byzantium, he marched along the coast to the fortress of Heraion Teichos, which he began to besiege. The siege lasted into 351, but eventually Philip captured the place, and apparently handed it over to the Perinthians. Philip had demonstrated that neither the Athenians nor the Thracian rulers could prevent him invading Thrace and operating there at his will. For now, that was enough, and he returned to Macedonia where much other business awaited him. He controlled the Thracian coast now almost as far as the Thracian Chersonnese, which was held by the Athenians, and the Thracian rulers inland were cowed. With that, Philip was satisfied for several years. It was not until 346 that he campaigned in Thrace again, and then only briefly. It was perhaps at that time that the sons of Berisades were removed from power and western Thrace up to the Nestos fully annexed to Macedonia. The aim of the campaign, however, was to weaken Cersebleptes, which was achieved by a resounding victory at Hieron Oros in early summer. Cersebleptes was obliged to make a subordinate alliance with Philip, but left in command of his realm. The central Thracian ruler Amadocus had apparently died, to be succeeded by a son named Teres, who was also now allied to Philip. In just a few months, any potential threat from Thrace was neutralized.

The final move in Philip’s long series of interventions in Thrace took place in the years 342 to 339, when for reasons left rather obscure—perhaps Cersebleptes was again intriguing with the Athenians—Philip decided to annex Thrace once and for all. A series of campaigns in 342 and 341 culminated in a crushing victory by Philip’s army over the joint forces of Cersebleptes and Teres in summer of 341, with both rulers now being deposed from power. Philip founded a series of Macedonian colonies in the Hebrus valley (see above, p. 79), including most famously Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv). He made contact with a tribe called the Getae in the Danube valley and established an alliance with them, cemented by marrying the Getan king’s daughter Meda. He consolidated Macedonian control of the Thracian coast on the Black Sea, but met with setbacks when he attacked and besieged his former allies Perinthus and Byzantium which, thanks to Persian and Athenian help, he failed to capture. Giving up there, he decided to return to Macedonia via the Danube. There he fought briefly against some Scythians north of the Danube and, feeling that his control of Thrace was now securely established, marched south towards Macedonia. Crossing through the mountain passes of Triballia, however, he was ambushed by local Triballian tribesmen and suffered a severe wound to his thigh. Philip recovered from this wound after a few weeks, and was able to get back to Macedonia in late summer of 339 having added all of Thrace to his kingdom and ended the Thracian threat to Macedonia for several generations.

4. SETTLING RELATIONS WITH THE SOUTHERN GREEKS

Macedonia’s relationship with its southern Greek countrymen had always been highly problematic. The developing city-states of southern Greece saw in Macedonia and the Macedonians a backward region and a people at best half-Greek, but blessed with rich natural resources of timber and metals that the southern Greeks coveted. As a result, southern Greeks had freely interfered in Macedonia throughout its history, from the settlement of southern Greek colonies along the coast—Methone, Pydna, and Therme, for example—to the interventions by Athenians, Spartans, and Thebans in the fifth and early fourth centuries. It was Philip’s aim to end the relative subordination of Macedonia, and make it instead the leader of the Greek world, with the southern Greeks following Macedonian commands rather than the other way about.

His first task in this regard was to win control of the southern Greek colonies on the Macedonian coast itself. These were the ports of Macedonia, and controlling them meant controlling Macedonia’s imports and exports. The first to be seized was Amphipolis at the mouth of the Strymon, besieged and captured by storm in the winter of 357/6. Later in the year 356 Pydna to fell to Philip’s siege: in both cases Demosthenes (1.5) hints at co-operation by pro-Macedonian elements within the cities, which makes sense. As the ports of the Macedonian territory, their future would be more secure as part of Macedonia proper. The same may be said of Apollonia, Galepsus, and Oisyme, on the coast between Amphipolis and the Pangaeum region, which were taken by Philip in late 356 to early 355. Methone took longer: it was not until the winter of 355 that Philip was ready to besiege it, and not until the spring of 354 that the town was forced to capitulate. During the siege, Philip was hit in the right eye by an enemy arrow, losing the sight of that eye. When the town finally surrendered, the people of Methone were permitted to depart freely with one garment each; the city was re-populated with Macedonian settlers. At some indeterminate date Therme too came under Macedonian control—it was later re-founded with the name Thessalonice by Alexander’s successor Cassander—and with that Macedonian control of its own coast and harbors was complete.

Beyond the coast of Macedonia, and far more troubling to Philip as ruler of Macedonia, lay the great three-pronged Chalcidice peninsula, home to numerous southern Greek colonies. On their own, these colonies were each no threat; but banded together under the leadership of the largest and most powerful of them, Olynthus, they had posed a very real threat to Macedonian security, most recently during the reign of Philip’s father Amyntas III. The obvious solution was to incorporate the Chalcidice into Macedonia, but that would be no easy task. Philip’s first move in this direction, in fact, was to assure the Olynthians and their allies of his friendship, securing a treaty with them in early 356. The Chalcidice would have to wait while Philip built his strength. But the Chalcidice was not fully united behind Olynthus: the key city of Potidaea at the neck of the Pallene peninsula—the westernmost of the three peninsulas making up the southern Chalcidice—was hostile to Olynthus. Here Philip offered to demonstrate his friendship to his new allies. He helped them besiege Potidaea, captured the place in the summer of 356, and handed it over to the Chalcidian League. That secured a friendly peace with the Olynthians and other Chalcidians for several years.

Of course, this peace could not last: the ambitions of Philip and Olynthus were essentially at odds with each other. The first crack appeared after Philip’s unexpected defeat in Thessaly in 353 (discussed below), when the Olynthians made an offer of alliance to Philip’s enemies the Athenians. For the moment this came to nothing, but it was clear to Philip that the Olynthians were at best fair-weather friends. Two years later, in 351, Philip found occasion to deliver a stern warning to the leaders of Olynthus, as Theopompus reveals. What the issue was exactly is not made clear in our sources, but it is evident that an anti-Macedonian faction existed and was strong at Olynthus; and it was perhaps at this time that Olynthus gave shelter to Philip’s two half-brothers (and rivals) Menelaus and Arrhidaeus, and maybe also Derdas of Elimea. All three were in Olynthus a few years later, at any rate. In 349 outright war broke out between Philip and the Olynthian League. The immediate cause, we are told, was that Philip demanded the Olynthians hand over to him his two half-brothers, and they refused. It seems evident that the Olynthians were permitting, perhaps even encouraging Menelaus and Arrhidaeus to intrigue against Philip in Macedonia from their shelter at Olynthus. Philip decided that the time had come to annex the Chalcidice to Macedonia once and for all. The war was fought in two phases, in fall 349 and in 348, with a break for operations in Thessaly in the winter of 349 to 348.

Towards the end of summer in 349 Philip marched his army south of Lake Bolbe in the north-eastern Chalcidice and invested the key city of Stageira (famous in history as the home town of the great philosopher Aristotle). The siege did not take long, and when Stageira was captured the city was razed to the ground. The lesson was not lost on the neighboring cities, which capitulated to Philip in short order—the likes of Arethousa, Stratonice, and Acanthus at the neck of the Athos peninsula. With the eastern part of the Chalcidice under his control, Philip could feel that a good start had been made. In spring of 348 he again invaded the Chalcidice, this time concentrating on the western side of the great peninsula down to the Pallene peninsula, the cities there apparently surrendering without much resistance, no doubt mindful of the fate of Stageira. The Olynthians appealed to Athens for help, and the Athenians—prompted by Demosthenes—ordered their general at the Hellespont, Charidemos, to intervene with eighteen triremes and four thousand mercenary peltasts (a special kind of “medium” infantry; see Glossary). This aid arrived too late: Philip had marched past Olynthus to the south and captured the Olynthian port city of Mecyberna, and then proceeded into the Sithone peninsula (the middle of the three Chalcidian peninsulas) where the key city of Torone likewise capitulated. That left Olynthus, at its inland location north of the Sithone peninsula, isolated and exposed to Philip’s siege, which began about mid-summer of 348 after two defeats in major skirmishes had confined the Olynthians behind their city walls.

The siege lasted several months, but was concluded around the beginning of September by the capture of the city. Olynthus was destroyed as being too dangerous to Macedonian security, and the bulk of the population was sold into slavery, an atrocity Philip evidently felt was necessary to secure Macedonia’s hold over the Chalcidice. Macedonian settlers were introduced into the Chalcidice, especially to the rich lands south of Lake Bolbe, around Apollonia and Arethousa, and to the territory of Olynthus and the western Chalcidic coast. After a generation or so, the Chalcidice was thoroughly Macedonianized and an integral part of the Macedonian realm. This represented a huge expansion of Macedonia, not only in territory but in wealth. The Chalcidice was home to a number of thriving cities, and had significant natural resources of timber and mines, as noted in Chapter 1. The capture and integration of the Chalcidice rounded off the establishment of a Macedonian homeland that now ran from the Pindus mountains and Lake Ohrid in the west to the River Nestus in the east, and from Mount Olympos and the Aegean Sea in the south to the Messapion range and even beyond to Mount Orbelus in the north.

Two other major regions of Greece bordered on Macedonia to the south and south-west, of unequal importance: to the south was the rich and important territory of Thessaly; to the south-west the poor and mountainous region of Epirus. Relations with Epirus were relatively easily managed. Around the end of 358 or beginning of 357 the Epirote ruler Neoptolemus the Molossian died, leaving three children: two teenage daughters and a son named Alexander, around five years old. It was, consequently, Neoptolemus’ younger brother Arrybas who became ruler, marrying the older of his two nieces, Troas, and becoming guardian of his nephew Alexander. It was easy for Philip, fresh from his great victory over Bardylis, to establish an alliance with the new ruler Arrybas, cemented by Philip marrying Arrybas’ younger niece Olympias, who thus became Philip’s fourth wife, after Phila of Elimea (m. ca. 360), Audata the Illyrian (m. 359), and Philinna of Larissa (m. 358, see below). That alliance and marriage settled relations between Philip and Arrybas for seven years, until Philip felt the need to re-visit the relationship in 350. The cause is not clear—perhaps Arrybas had become too friendly with the Molossian ruling family’s traditional allies, the Athenians—but Philip intervened in Epirus and took custody of his young brother-in-law Alexander, now about twelve years old, carrying him off to Pella to be educated under Philip’s eye. It seems likely that some borderlands, Atintania and Parauaea bordering on the upper Macedonian canton of Tymphaea, were now added to Macedonia. Young Alexander was educated in Philip’s school at Pella, and in time became one of Philip’s paides (see Chapter 4 section 6), learning to be a good leader and loyal to Philip. In the winter of 343/2, finally, when Alexander was about twenty, Philip again invaded Epirus and completed his settlement of the region as a subordinate ally of Macedonia by removing the ruler Arrybas and setting young Alexander on the throne. Almost Philip’s last act was to further secure his relationship with Alexander, in 336, by marrying his daughter by Olympias, Cleopatra, to her uncle Alexander, making the latter his son-in-law as well as his brother-in-law.

Thessaly was a more difficult region to manage. Thanks to its large agricultural plain, the largest in Greece, well-watered by the perennially flowing River Peneius and its tributaries, Thessaly was the largest grain-growing region of Greece, and the only region that regularly had a large surplus of grain for export. That made Thessaly wealthy and important. Like Macedonia, Thessaly was a region of landowning aristocrats dominating and exploiting a large serf population—the penestai—and lacking in significant cities: only Larissa in the north, Pharsalus in the south, and Pherae on the coast were major urban settlements. The various regions of Thessaly were dominated by great aristocratic clans, the most important at this time being the Aleuadae of Larissa, and the family of the tyrant Jason and his nephew Alexander in Pherae. The Aleuadae, as we saw in Chapter 2, had long-standing friendly relations with the ruling Argead clan of Macedonia. In the late 370s the tyrant Jason of Pherae had made himself ruler of all Thessaly. After his death in 370, the power of Pherae declined, but in the later 360s Jason’s nephew Alexander sought to rebuild his uncle’s power. Alexander was assassinated in 358 by his brothers-in-law Lycophron and Tisiphonus, and this upheaval provided the occasion for the Aleuadae to try to break Pheraean power. Too weak, as it turned out, to do this on their own, they turned to the recently victorious Philip for help, which Philip was glad to give. He entered Thessaly with his army, established the independence of northern Thessaly under the Aleuadae, and married a woman of Larissa named Philinna. Though some sources demean Philinna as a mere “flute-girl,” in truth she was doubtless a member of the Aleuad clan, married by Philip in order to cement his alliance with the Aleuadae. Within a year, it seems, Philinna bore Philip his first son, named Arrhidaeus after Philip’s grandfather. Sadly, as the lad grew up, it became apparent that he suffered from some form of mental deficiency.

His alliance with the Aleuadae settled his relationship with Thessaly for several years, in Philip’s estimation, as he was busy with northern affairs. Only a brief interventions by a small force was needed in early 355 to keep the Aleuad control of northern Thessaly secure. This situation changed as a result of the so-called Third Sacred War, fought from 356 until 347 between the Phocians and the Boeotians with various allies on both sides. In order to prosecute this war the Phocian leaders—at first Philomelus and then Onomarchus and Phayllus—laid hands on the wealth of Apollo’s oracle at Delphi, using this money to enroll large mercenary armies that temporarily made Phocis a major power in the Greek world. The Oracle of Apollo at Delphi played a very important role in Greek religion and international relations. It was standard for every Greek state, and for many private individuals too, to consult the Oracle before any major undertaking. Control of the Oracle was thus of importance to every Greek, and especially to every Greek state; and the wealth of the Oracle represented the accumulated gifts of Greeks of all sorts over centuries. Seizing control of the Oracle and its wealth was thus a hugely controversial move by the Phocians, and one that aligned the Greek world into pro- and anti-Phocian camps.

Inevitably, therefore, the “Sacred” war impacted on Thessaly, especially as the Thessalians had long played a major role in the organization—called the Amphictyonic League—that oversaw the Oracle. In the event, the Aleuadae and their regional associates in the Thessalian koinon (league or commonwealth) allied with the Thebans, leading their rival Lycophron of Pherae to ally with the Phocians. In pursuit of this alliance, a Phocian force under Phayllus entered Thessaly in 353 to help Lycophron, causing the Aleuadae once again to appeal to Philip for aid. Having captured Methone, rounding off his control of Macedonia’s coast, and having for the time being subdued the Illyrians and Thracians, Philip was ready to settle the troubled affairs of Thessaly.

Besides being large, populous, and wealthy, Thessaly was of great strategic importance to Macedonia because it offered the only good land routes by which Macedonia might be invaded from the south: the Vale of Tempe between Mounts Olympus and Ossa, through which the River Peneius reached the sea, was the best, though more mountainous inland routes to the west of Olympus or via Elimea were also passable. Philip therefore naturally wanted to control Thessaly, and the Phocian invasion offered him all the excuse he needed to make his move. At first his invasion of Thessaly went well. In summer 353 he drove Phayllus and his mercenaries out of Thessaly, but that success turned out to be merely a prelude to much more difficult campaigning. Late in the summer the Phocian commander Onomarchus entered Thessaly with a large army including, crucially as it turned out, a substantial train of catapults and stone-throwers. Having accurately assessed the strength of Philip’s pike phalanx, Onomarchus decided to fight him via a stratagem. He found a valley overlooked by hills on either side, and drew up his army in the mouth of this valley, his aim apparently being merely to protect his flanks against Philip’s Macedonian and allied Thessalian cavalry. Secretly, however, he had stationed his catapults and stone-throwers just out of sight on the reverse slopes of the overlooking hills on either side. For once, Philip’s scouts failed him: they did not notice and report the enemy artillery on either side, allowing Philip to be drawn into Onomarchus’ trap. When Philip’s army advanced to the attack, Onomarchus had his men retreat in feigned flight, drawing Philip’s forces into the valley. At a signal, the artillery on either side crested the hills and rained down a withering fire of bolts and stones onto Philip’s troops. The effect was devastating. Though Philip managed to extract his army, it had suffered heavy losses in this defeat, and morale plummeted. For the only time in his career, Philip nearly lost control of his Macedonian soldiery; and the effects of his defeat were to be felt elsewhere among his many enemies, who were emboldened to renew resistance to him, as we have seen. For the moment, Philip could only pull his army back out of Thessaly, to the reassurance of winter quarters in Macedonia, where their obedience and morale were restored by gifts and rest.