“They’re dreadfully fond of beheading people here.”

GAMES IN THE GARDEN When Alice finally finds her way into Wonderland’s “beautiful garden” and croquet ground, she discovers a white rose tree being painted red by gardeners in the form of animated and quarrelsome playing cards. Yet Alice does find something oddly familiar about this garden—and this surreal scene—undoubtedly because this chapter is largely a burlesque of the real Alice’s own family’s garden and croquet parties at the Deanery at Christ Church, Oxford.

The Deanery garden was the site of many of the elaborate garden parties Alice Liddell’s parents, the Dean and Mrs. Liddell, held for all levels of British high society: academic, political, ecclesiastic, military and royal.

It was also while gazing through a window in the college library that Lewis Carroll first caught sight of Alice and her sisters, on the Deanery’s croquet lawn. Later, he arranged to photograph Alice and her two sisters in the garden, wearing their best summer dresses and holding croquet mallets.

Who’s for croquet?: Alice and her sisters.

On the mythological level, Wonderland’s “beautiful garden” is the Garden of Elysium, the most desirable realm in the ancient Greek afterlife. In Metamorphoses, or the Golden Ass (C. AD 155), Lucius Apuleius tells us how, as an initiate into the Eleusinian Mysteries, he “set one foot on Proserpine’s threshold…[and] entered the presence of the gods of the underworld.”

Ruled by an underworld King and Queen, here were found the souls of heroes and heroines who, according to Homer and Pindar, could be observed engaged in games in the “blissful meadows” of asphodel lilies. Pindar gives us a fuller description of this place: “In Elysium where fields of the pale liliaceous asphodel, and poplars grew, there stood the gates that led to the house of Hades.”

In Virgil’s Aeneid we are told that Elysium enjoys perpetual springtime and there are gardens and shady groves. By the Renaissance, Elysium had become a synonym for an eternal pagan paradise. The Champs-Élysées, meaning “Elysian Fields,” became the most celebrated avenue in Paris, and the Élysée Palace became the residence of the president of France.

The Rose Garden of Philosophers: Don’t forget your key.

ROSICRUCIAN ROSE GARDEN It is significant that Alice first observes a garden with a rose tree with white roses being painted red. Wonderland’s royal rose garden is also the garden of the Brotherhood of the Rosy Cross. One obvious parallel is that both Alice and the initiate must use a golden key to gain entry to the locked door into a rose garden.

Remarkably, all the tea party theosophists wrote extensively about this secret garden. The Rosicrucian Mad Hatter, Robert Fludd, published “A Philosophicall Key,” which granted the initiate entry into that garden. The Rosicrucian March Hare, Michael Maier, also wrote about this secret rose garden and the golden key to its gate in his magnificently illustrated Atalanta fugiens (1617): “He who tries to enter the Rose-garden of Philosophers without the key is like a man wanting to walk without feet.”

Maier also speaks of the revelation within the garden of the fountain flowing with the Rosicrucian “Elixir of the Red Rose and the White Rose.” This epiphany is comically transformed in Wonderland’s rose garden into a scene wherein quarrelling gardeners desperately employ a red elixir (of sorts) to paint the white roses and transform them into red roses.

Also as noted here, an elaborate engraving in the Rosicrucian Cabala, Mirror of Art and Nature: in Alchemy (1615) shows a rabbit being pursued into an underground world comparable to Wonderland. In the same document, there is a more detailed illustration of this philosopher’s rose garden on the pinnacle of the Mountain of Alchemy. This is the ultimate goal of the initiate: a rose garden with a hedge around the fountain of Mercury. The Wonderland garden with its white roses painted red, its “bright flower beds and cool fountains” and its King and Queen of Hearts is comparable to the Cabala’s rose garden with its flower beds and fountains and its Sun King whose emblem is the red rose and Moon Queen whose emblem is the white rose. And both are comparable to the lawns and fountain of Mercury before the entrance to Christ Church’s Deanery.

Ultimate goal: On the summit of the Mountain of Alchemy.

In the Wonderland garden, the denizens are—like those of the Garden of Elysium—also involved in the playing of games, in this case a peculiar card game and a very odd form of croquet. Wonderland’s Elysium is the Queen’s Croquet-Ground, where Alice watches the arrival of a royal procession of soldiers, courtiers, royal children, royal guests and the King and Queen of Wonderland themselves.

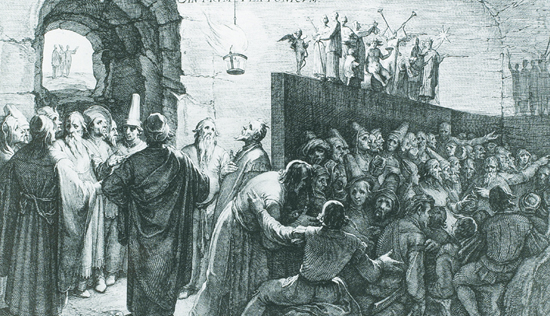

There were also processions of this sort in the Eleusinian Mysteries, just before the revelations. As Lucius Apuleius describes them, “Presently the vanguard of the grand procession came into view” with all manner of costumes and emblems of deities.

As the Wonderland procession passes by, Alice wonders “whether she ought not to lie down on her face like the three gardeners.” The real Alice would recognize the dilemma of a child’s attempting to determine appropriate rules of etiquette for such a procession. It was important for her to learn how to determine the rank of those arriving in the Deanery garden so she could address them in the appropriate manner.

PYTHAGOREAN NUMBERS When Alice enters the garden, she discovers the numbers 7, 5 and 2 in the form of playing cards who are gardeners. Not illogically, the gardeners are spades, but what is the significance of their numbers?

Lewis Carroll studied the Pythagorean theory of numbers through the translations and theosophical commentaries in Thomas Taylor’s Theoretic Arithmetic (1816). Pythagoreans believed that the first things were numbers, for nothing can exist or be discerned without number. Taylor succinctly summed up the Pythagorean theory by quoting Theon of Smyrna (c. AD 100), the disciple of Pythagoras and Plato: “Numbers are the sources of form and energy in the world. They are dynamic and active even among themselves … almost human … in their capacity for mutual influence.”

It should not be surprising, then, that the first things Alice encounters in the Wonderland garden are numbers—or that they are behaving like quarrelling humans, “dynamic and active even among themselves.” These card-gardeners confirm Theon’s comment that “numbers have independent life and qualities that make them akin to living creatures with personalities.”

In Wonderland, each of these numbers has a distinct personality: 7 is self-righteous and argumentative, 5 is sulky and accusatory, and 2 is quarrelsome and divisive. Here the playing cards behave like humans, while living creatures (flamingos and hedgehogs) behave like inanimate objects (croquet mallets and balls).

In the Wonderland garden, Carroll’s choice of cards with the numbers 7, 5 and 2 has always been something of a mystery. The same has been true of the strange wording of the dispute 5 has with 7 over the trouble with “bringing the cook tulip-roots.”

To resolve this mystery, we may, in a typical Lewis Carroll word twist, read “tulip-roots” as “the root of 2,” or √2. And indeed, the numbers 7, 5 and 2 could give us an answer to the tulip-root riddle because the ancient Greeks famously used the ratio of 7 : 5 as the simplest and most convenient approximation of the irrational √2. And so, with the numbers 7, 5, 2 we can create the equation 7 : 5 = √2.

Furthermore, the reason for the dispute between these numbers is provided in the wording of 7’s indignant reaction to 5’s revelation about tulip-roots: “Well, of all the unjust things.” For Pythagoreans, √2 was the archetypal unjust thing, for two reasons. First, it is an irrational number that cannot be “justified”—that is, it cannot be expressed as a whole number or as a fraction. And second, its discovery allegedly threatened to wreck the entire Pythagorean philosophy of whole numbers, to the point that, according to legend, its discoverer was drowned in the hope of concealing this flaw in their system.

However, once the secret was out, the ancient Greeks became especially fascinated with √2, just as they were with those other famous irrational keys to knowledge, Φ and π. All three produce infinite Euclidean algorithms, and were the focus of much study and wonder among the ancients—as well as our mathematician, Charles Dodgson.

Pythagoras: Numbers came before anything else.

PLATO’S REPUBLIC IN WONDERLAND Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland borrows extensively from the themes and ideas of Plato’s Republic. Initially, Alice’s underground hall in many ways is comparable to Plato’s famous allegory of the cave. In Francis Cornford’s translation of The Republic, Plato describes his allegorical cave and its inhabitants: “Imagine the condition of men living in a sort of cavernous chamber underground, with an entrance open to the light and a long passage all down to the cave. Here they have been since childhood.”

This is the condition of most people, Plato argues: living in darkness and shadows cast by firelight in an underground chamber. Only those who are willing to question their state of existence can make their way out of this subterranean world of illusions. Only then will they discover the tunnel into the light of the garden of true knowledge.

Alice’s underground hall lit with lamps is like Plato’s fire-lit cave—a subterranean world of illusions. And like Plato’s prisoner, Alice struggles to find her way out of the underground chamber through a tunnel into a bright garden. “How she longed to get out of that dark hall, and wander about among those beds of bright flowers and those cool fountains.”

In Plato’s allegory, this garden is the ideal philosopher’s garden of archetypes, or (as Plato stated) Ideas or Forms. In the Wonderland Queen’s garden, Lewis Carroll parodies this garden of archetypes. It is an ideal abstract realm of number and form wherein numbered, oblong playing cards are animated and speak and behave like humans. For, as the logician and Carrollian scholar Duncan Black once wrote, Lewis Carroll’s “real life was lived in a world of inner meanings. Philosophic and logical principles were just as real for him as human beings and occupied his mind just as much.”

Consequently, in Wonderland’s garden, the playing cards Alice first encounters are spades who—logically enough—work as gardeners. It follows that the numbered club cards are soldiers, the numbered diamonds are wealthy courtiers and the numbered hearts are the royal children.

The rank and order of these cards in the procession watched by Alice are similar to the rank and order of the hierarchy in Plato’s republic. The gardener spades are matched with Plato’s lowly agricultural workers; the Wonderland soldier clubs are comparable to his military auxiliaries; the courtier diamonds are akin to his wealthy merchant class; the Wonderland face cards of each suit resemble the republic’s oligarchs in each class; and finally, in Carroll’s trump suit of hearts, we have the royal family ruled by the King of Hearts who is the republic’s philosopher-king.

Wonderland’s parodic King of Hearts is somewhat dim-witted and vague, but relatively speaking, he does appear to possess some of the virtues of the temperate and self-restraining philosopher-king. Certainly, his habit of constantly pardoning all those condemned by his tyrannical Queen suggests something of a forgiving and compassionate nature. It is worth noting the King of Hearts’ glib instruction to the White Rabbit to “Begin at the beginning.” Although sounding absurd in the mouth of the rather foolish King of Hearts, it was the way Plato’s philosopher-king ideally approached any dilemma. In fact, Aristophanes picked exactly the same phrase to mock Plato’s school of philosophers in his comedy The Clouds.

Plato’s cave: Only those who question can find the exit.

Royal visit: Prince and Princess of Wales at Christ Church.

This was particularly true of royal visits. The royal garden scene in Wonderland would certainly remind Alice Liddell of Queen Victoria’s visit to Christ Church in 1860, and the reception held on the evening of her stay at the Deanery. She would also vividly remember the grand processions of soldiers and high-ranking officials during the 1863 royal visit of the newlywed Prince and Princess of Wales. On this occasion, a photograph was taken in Tom Quad in which Alice and her family can be seen seated next to the royal couple on a dais under a pavilion tent before a large gathering of soldiers and guests and the Fountain of Mercury.

Henry Liddell: King of Hearts.

Alice Liddell’s parents were the closest thing to royalty that academia had to offer. Consequently, in Wonderland, the King and Queen of Hearts are Alice’s parents: HENRY GEORGE LIDDELL (1811–1898) and LORINA HANNAH LIDDELL (1826–1910). Henry Liddell—dean of Christ Church and chief administrator of Oxford University—was an authentic aristocrat, with an earl on one side of the family and a baron on the other. He became the confidant of three prime ministers, Palmerston, Gladstone and Disraeli, and was on intimate terms with the Queen and her family.

Liddell was also highly respected as an academic. He was the foremost Greek scholar of his day, and co-author of the still-authoritative Liddell and Scott Greek-English Lexicon. His administration was noted for its liberal reforms and the academic modernization of Oxford. Furthermore, Liddell architecturally transformed Christ Church by carrying out the most ambitious building program in its history. Although sometimes intimidating and aristocratic in his bearing, he was also noted for his kindly nature.

Like the King of Hearts, Liddell was generally seen as well-meaning but—like many academics—somewhat vague and careless as an administrator. In this, the dean was certainly comparable to the vague and indecisive King of Hearts, who demonstrates a similar cavalier disregard for legal procedures as he flip-flops on court rulings: “ ‘important—unimportant—unimportant—important’ as if he were trying which word sounded best.”

On the mythological level, the King of Hearts and Dean Liddell both assume the mantel of Hades, the King of the Underworld. As his subterranean world was also the source of minerals and gemstones, Hades was sometimes known as “the rich one” or Plouton, derived from the Greek word for “wealth,” from which the Romans came to know him as Pluto. He also was given the epithet Eubuleus, meaning “good counsel” or “well-intentioned.” For, despite our modern view of this underworld god, in Greek mythology, Hades was commonly portrayed as passive rather than evil. Like the rather benign King of Hearts, his role was to maintain balance between worlds.

Hades’s Queen is most commonly portrayed as the goddess Persephone. But she assumed this role only after her marriage to Hades—and then only for a third of each year. Clearly, the character of the Queen of Hearts is conveyed on the mythological level by another, more archaic goddess who preceded Persephone as Queen of the Underworld.

Twenty years after writing his fairy tale, Lewis Carroll himself provided his readers with a specific clue to the mythological origin of the Queen of Hearts. In his essay “ ‘Alice’ on the Stage,” Carroll tells us: “I pictured to myself the Queen of Hearts as a sort of embodiment of ungovernable passion—a blind and aimless Fury.”

The Furies, or in Greek the Erinyes, meaning “the avengers,” were the underworld servants of Hades. These demonic women would inflict condemned murderers and perjurers with tormenting madness. After a considerable mythological investigation, the Carroll biographer Donald Thomas names the prototype of Wonderland’s Queen of Hearts as Tisiphone, the Queen of Furies.

Ungovernable passion: Orestes Pursued by the Furies, by Adolphe William Bouguereau, 1862.

Tisiphone the Fury would certainly be an excellent model temperamentally for the heartless and vengeful Queen of Hearts. The Furies, as the underworld court’s avenging spirits, had a duty to enforce the penalty for the crime of perjury, which may go some way toward explaining the Queen’s irrational suspicion of any witness or defendant in her court. Also, “Tisiphone”—meaning “voice of revenge”—fits the shrieking Queen of Hearts with her cry of “Off with his head!”

Or, as Donald Thomas concludes in Lewis Carroll: A Portrait with Background: “As in Wonderland so in the underworld, the Queen of Furies presides over the punishments, in ways more colourful than a mere command of ‘Off with his head!’ ” However, this being a child’s fairy tale, Carroll has reduced the terror of the Queen of Furies to that of a cardboard Queen of Hearts, who, we are assured, actually “never executes nobody, you know.”

Lorina Liddell: Queen of Hearts.

Alice’s mother, Lorina Hannah Liddell—the real-life Queen of Hearts—was beautiful when young. In later life, this mother of ten became stouter and temperamentally rather overbearing. As the Deanery became the hub of Oxford society, it was only through the dean’s wife that access might be granted to visiting prime ministers, archbishops, aristocrats and royalty. Consequently, like Wonderland’s royal family under the authority of the Queen, the Liddells were very much seen as Oxford’s royal family firmly under the authority of Mrs. Liddell.

Certainly, Lewis Carroll was not the first to observe how Mrs. Liddell often held court at the Deanery. There was a jingle—not of Carroll’s composition—that made its rounds at Oxford:

I am the Dean and this is Mrs. Liddell

She plays the first, and I the second fiddle.

She is the Broad; I am the High:

And we are the University.

To some, the Deanery must have seemed haunted by its former royal inhabitants: the ill-fated King Charles I and his Queen, Henrietta Maria. The royal couple had made Christ Church and the Deanery their palace during the English Civil War. It appears that by reputation Queen Henrietta Maria, Lorina Hannah Liddell and the Queen of Hearts were temperamentally well matched, as were King Charles I, Dean Liddell and the King of Hearts. Even those most sympathetic to royalty, such as the loyal Bishop Kennet, wrote that all regretted “the influence of a stately queen over an affectionate husband.”

Many believed that Charles’s fatal flaw was submissiveness to the opinions of his Queen, who frequently “precipitated him into hasty and imprudent counsels.” Others drew a picture of Queen Henrietta Maria that was not unlike the Queen of Hearts: volatile, haughty, uneducated and unreflective. This was also how the Oxford dean’s enemies characterized Lorina Liddell.

PLATO’S TYRANT AND THE HEARTLESS QUEEN Wonderland’s Republic-like society is no utopia. It is an underground dystopia. Carroll seems to be (rightly) suggesting that Plato’s ideal republic was so abstract and logical that no human could possibly live in it for long. And indeed, The Republic portrayed a philosopher’s dream that would undoubtedly become a political nightmare if applied to any society of human inhabitants.

The Queen of Hearts is obviously aligned with The Republic’s “worst” possible ruler as portrayed in Plato’s tyrant’s allegory. The word savage is used several times in Wonderland to describe her. Likewise, Plato’s self-indulgent tyrant is possessed of a “terrible, savage and lawless form of desires” that is so extreme, it is the cause of suffering hundreds of times greater than that of the average man. And as we have already observed, Carroll himself described the Queen of Hearts as the “embodiment of ungovernable passion.” This unmistakably conforms to Plato’s description of the tyrant as being “filled with passion without restraint.”

Both the Queen of Hearts and Plato’s “worst” ruler hold power by the force of an unquestioning bodyguard. In The Republic, we have the unquestioning military auxiliaries, while in Wonderland, we have the unquestioning club soldiers. Without hesitation or remorse, the tyrant and the Queen of Hearts both order the execution of friend and foe alike.

Also, Plato informs us, the absolute power of the tyrant brings absolute misery: “the misery of the despot is really in proportion to the extent and duration of his power.” This certainly appears to hold true for the “savage” Queen of Hearts, who, “like a wild beast,” is consumed by fits of self-indulgent rage not unlike Plato’s tyrant, who, we are told, also behaves like a “savage beast.”

Furthermore, when the child Alice eventually overrules the Queen’s outrageously childish fitful commands, there is another direct parallel with the tyrant, for in Plato’s allegory, “The parent falls into the habit of behaving like the child, and the child like the parent.”

And finally, just as Alice discovers she has nothing to fear from the Queen or her henchmen because they are “nothing but a pack of cards,” there is a comparable revelation in the tyrant’s allegory, when it is revealed—in Allan Bloom’s translation—that “this phantom of tyrannical pleasure is without substance.”

Just as the plot of Through the Looking-Glass was based on a chess game, this chapter of Wonderland appears to be linked to some sort of card game. Just what card game has always been in question. The obvious choice would be some form of the game of Hearts. And indeed, as if to confirm this, Tenniel chose to illustrate the Queen of Hearts wearing the pattern of the queen of spades, the most powerful and fatal card in Hearts. However, not much else is comparable. And why are we left with only the King and Queen of Hearts along with Alice at the end of play?

In fact, it seems that the game suggested here is Lewis Carroll’s own original card game of Court Circular, the rules of which he published in a pamphlet in 1860. In this game, the highest possible hand is a three-card royal straight flush in hearts—that is, ace, king and queen of hearts. How does Alice fit into this game? Her identity—in terms of card ranking—is hinted at by the King of Hearts.

The King informs the Queen that Alice “is only a child,” and, as we have already learned, the numbered heart cards are “the royal children.” If we presume that Alice is the youngest child/card, she must be number one—that is, an ace. The rules of Court Circular tell us that the ace may be played as either the lowest or highest card in the suit. And as the ace of hearts, Alice completes the winning hand: a three-card royal flush in hearts.

The other game being played in “The Queen’s Croquet-Ground” is, of course, croquet. The trend-setting Liddells installed one of Oxford’s first croquet grounds on the Deanery lawn in 1856, the same year the first set of rules for this new game were published in London. In this, they proved to be leaders in fashionable Oxford society, for the next two decades were known as “the era of crinoline croquet,” in which parties centering on the game were all the rage.

Croquet became known as “the Queen of Games.” The All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club was formed in 1868, and annual championships were held at Wimbledon in the 1870s. Croquet outstripped all other games in popularity; a single edition of Jaques’s “Croquet: The Laws and Regulations of the Game” sold over sixty thousand copies in a year. As with his own card game, Lewis Carroll—who seems to have followed every fad—invented and published his own variation of this game, called Croquet Castles. Unlike the Wonderland game, Croquet Castles was not played with flamingos and hedgehogs.

In Wonderland, the Queen of Hearts arbitrarily invites and dismisses whomever she wishes. So when she discovers the uninvited Duchess playing croquet with Alice, she immediately kicks her out of the garden. This hints at the fact that the Oxford Duchess—the bishop of Oxford—was welcome at the Deanery only on invitation by the Liddells. Christ Church was the only college in England in which both the college and the cathedral were under the authority of the dean. (The only part of Christ Church that the bishop controlled was the great kitchen.) But as a conservative opponent of the dean, the bishop Samuel Wilberforce was tolerated only on special occasions. And just as the Queen of Hearts banished the Duchess at will, Mrs. Liddell could on a whim decide to banish Wilberforce from her croquet garden parties.

A rather different scenario presented itself with the disturbing appearance of the floating head of the Cheshire Cat over the croquet ground. Neither the King’s nor the Queen’s commands to have the head removed are met with success. The Oxford Cheshire Cat was the Reverend Edward Bouverie Pusey, who as a Christ Church canon could not be removed as a college head by the dean. Viewed by Carroll and other conservatives as the spiritual guardian of the college, Pusey kept a watchful eye over the Deanery—just as the Cheshire Cat watched over the Queen’s garden.

The floating cat’s head is also suggestive of the haunting spirit of the founder of Christ Church, the fifteenth-century Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, who—like the Cat—was also threatened with beheading. It is Wolsey’s cardinal’s hat with its broad brim and long tassels that surmounts the cats’ heads on Christ Church’s coat of arms, and it is his spirit that Carroll saw as watching over the college. Indeed, years later, in his squib The Vision of the Three T’s (1873), Carroll humorously conjured up the ghost of the college’s founder: “one of portly form and courtly mien, with scarlet gown, and broad brimmed hat whose strings, wide-fluttering in the breezeless air, at once defied the laws of gravity and marked the reverend Cardinal! ’Twas Wolsey’s self!” Carroll had this vision of Wolsey’s spirit arise in protest to attack the dean’s uninspired design for Christ Church’s newly erected belfry.

The cats and the hat: Christ Church’s coat of arms.