16

What can a corpus tell us about multi-word units?

Chris Greaves and Martin Warren

1. Background

The idea that we best know the meaning of a word, not by examining it in isolation, but by the company that it keeps, is usually ascribed to Firth (1957) who describes the ways in which meanings are often created by the associations of words rather than by individual words. Firth terms these associations ‘meaning by “collocations”’ to which, he argues, it is possible ‘to apply the test of “collocability”’ (1957: 194). He provides examples of meaning by collocation such as ‘one of the meanings of ass is its habitual collocation with an immediately preceding you silly, and with other phrases of address or of personal reference’ (1957: 195). Similarly, he states that ‘one of the meanings of night is its collocability with dark, and of dark, of course, collocation with night’ (1957: 196). The test of collocability refers to the notion that words are collocates when they are found to be associated with sufficient frequency to exclude the possibility that they are chance co-occurrences. This has been taken one step further and, based on abundant corpus evidence, corpus linguists have concluded that words often have a preference for what they combine with. For example, O’Keeffe et al. (2007: 59–60) point out that the verbs go and turn both combine with grey, brown and white, but they do not always both combine with other words. For example, one can say ‘people go mad, insane, bald or blind’, but not ‘people turn mad, insane, bald or blind’ (2007: 59–60). The latter are instances of words which do not collocate and these are investigated by Renouf and Banerjee (2007). They describe such cases as being the opposite of collocation, which they term ‘lexical repulsion’ (2007: 417): that is, the tendency for words not to be associated. In this chapter, we are concerned with word associations, although it should be noted that studying why words do not associate can also offer insights into register, style and semantics (Renouf and Banerjee 2007: 439).

For the first computer-mediated corpus-driven study ‘to test the assumption that collocation was an important part of the patterning of meaning’ (Sinclair et al. 2004: xvii), we need to go back to the 1960s. A research team, led by John McH. Sinclair, compiled a spoken corpus of 135,000 words in order to study English collocation (Sinclair et al. 1970). The final report (see Sinclair et al. 1970, reprinted in 2004) and Sinclair’s later work contain three fundamental findings which have far-reaching consequences for corpus linguistics in general, and research into multi-word units of meaning in particular. First, the primacy of lexis over grammar in terms of meaning creation –‘on the whole grammar is not involved in the creation of meaning, but rather concerned with the management of meaning’ (Sinclair et al. 2004: xxv). Second, that meaning is created through the co-selection of words. Third, that, by virtue of the way in which meaning is created, language is phraseological in nature which is embodied in his famous ‘idiom principle’ (Sinclair 1987). It is not overstating Sinclair’s role in corpus linguistics to say that he has placed the study of multi-word units of meaning at the centre of corpus linguistics through his emphasis on language study ultimately being the study of meaning creation.

What is a multi-word unit?

Despite the fact that the importance of collocation was established in the 1960s (Halliday 1966; Sinclair 1966; Sinclair et al. 1970), it is only relatively recently that the study of multi-word units has become more widespread. These studies have begun to explore the extent of phraseology, or to analyse the inner workings of the phraseological tendency, in the English language. For example there have been studies of extended units of meaning, pattern grammar, phraseology, n-grams (sometimes, termed lexical bundles, lexical phrases, clusters and chunks), skipgrams (these include a limited number of intervening words), phrase-frames and phrasal constructions (see, for example, Sinclair 1987, 1996, 2004a, 2005, 2007a, 2007b; Stubbs 1995, 2001, 2005; Partington 1998; Biber et al. 1999; Hunston and Francis 2000; Tognini Bonelli 2001; Hunston 2002; Biber et al. 2004; Hoey 2005; Teubert 2005; Wilks 2005; Carter and McCarthy 2006; Fletcher 2006; Nesi and Basturkmen 2006; Scott and Tribble 2006; O’Keeffe et al. 2007; Cheng and Warren 2008; Granger and Meunier 2008). Here we do not focus on pattern grammar (see Hunston, this volume) because it is not concerned with the meanings of a particular unit of meaning but rather with ‘words which share pattern features, but which may differ in other respects in their phraseologies’ (Hunston and Francis 2000: 247–8). An example of pattern grammar is ‘N as to wh, where a noun is followed by as to and a clause beginning with a wh-clause’ and which is shared by a number of nouns (Hunston and Francis 2000: 148). It is important to bear in mind that it has been established by pattern grammarians (see, for example Sinclair 1991; Hunston and Francis 2000) that ‘it is not patterns and words that are selected, but phrases, or phraseologies, that have both a single form and meaning’ (Hunston and Francis 2000: 21).

Most of the studies of multi-word units have focused on n-grams. N-grams, which have attracted a variety of labels such as ‘lexical bundles’, ‘chunks’ and ‘clusters’, are frequently occurring contiguous words that constitute a phrase or a pattern of use (e.g. you know, in the, there was a, one of the). Typically, n-grams are grouped together based on the number of words they contain, with the result that two-word n-grams may be referred to as bi-grams, three-word as tri-grams and so on. Determining the cut-off for including n-grams in frequency lists varies, but a common cut-off is twenty per million (see for example, Biber et al. 1999; Scott and Tribble 2006) with others setting it lower, for example, ‘at least 20 in the five-million word corpus’ (O’Keeffe et al. 2007: 64). This decision is partly driven by the size of the corpus being examined, especially when researchers want to analyse larger n-grams. Interestingly, the frequency of n-grams decreases dramatically relative to their size so that while Carter and McCarthy (2006: 503) find 45,015 two-word n-grams in their five-million-word corpus, they find only thirty-one six-word n-grams with twenty instances or more. This observation has important implications because the undoubted prevalence of phraseology in the language does not mean that language use is not unique or creative.

This point has been made very convincingly by Coulthard in his role as a forensic linguist appearing as an expert witness in court cases around the world (see, for example, Coulthard and Johnson 2007). Coulthard (2004) demonstrates that the occurrence of two instances of a nine-word n-gram, I asked her if I could carry her bags, in two separate disputed texts, one a statement and the other an interview record, is so improbable as to cast serious doubt on their reliability as evidence in a court case (Coulthard and Johnson 2007: 196–8). Coulthard (2004) bases his findings on a Google search conducted in 2002 in which he found 2,170,000 instances of the two-word n-gram I asked, 86,000 instances of the four-word n-gram I asked if I, four instances of the seven-word n-gram I asked her if I could carry, and no instances of the full nine-word n-gram (2007: 197). Importantly, Coulthard and Johnson draw the conclusion that ‘we can assert that even a sequence as short as ten running words has a very high chance of being a unique occurrence’ (2007: 198). This intriguing finding both confirms the phraseological tendency in language (Sinclair 1987) as well as its uniqueness and creativity, a fact that should not be lost sight of when we study multi-word units.

Most studies of multi-word units in the form of n-grams adopt an inclusive approach to phraseology and keep all recurring contiguous groupings of words in their lists of data as long as they meet the threshold frequency level, if any (see, for example, Biber et al. 1999; Cortes 2002; Carter and McCarthy 2006). Some, however, have a less inclusive view, exemplified by Simpson (2004) who ignores ‘strings that are incomplete or span two syntactic units’ (2004: 43). Thus and in fact, in terms of and you know what I mean are included in her study of formulaic language in academic speech, while and in fact you, in terms of the and you know what I are excluded (2004: 42–3).

Placing restrictions on the size of the n-grams examined is another decision often made by researchers. It is quite common for researchers to focus on larger n-grams in their studies and various arguments are put forward for ignoring the far more numerous two-word and three-word n-grams. For example, for Cortes (2004) two-word n-grams do not even qualify as what she terms ‘lexical bundles’. She argues that

even though lexical bundles are frequent combinations of three or more words, the present study investigated the use of four-word lexical bundles because many fourword bundles hold three-word bundles in their structures, as in as a result of, which contains as a result.

(Cortes 2004: 401)

In fact, of course, all four-word n-grams contain within them two three-word n-grams and three two-word n-grams. Cortes (2004) continues that four-word n-grams are more frequent than five-word n-grams and so they afford a wider variety of structures and functions to analyse. Similarly, Hyland (2008: 8) states that he decided ‘to focus on 4-word bundles because they are far more common than 5-word strings and offer a clearer range of structures and functions than 3-word bundles’. Such a selective approach to the study of n-grams is not without its critics and Sinclair (2001), for example, is critical of those who ignore two-word n-grams, which easily outnumber all the rest of the n-grams in a corpus combined, simply for reasons of convenience. He states that by not examining the largest group, researchers avoid the fundamental issue of ‘whether a grammar based on the general assumption that each word brings along its own meaning independently of the others is ultimately relevant to the nature of language text’ (2001: 353) and, in effect, they misrepresent the prevalence of n-grams. Other researchers (see, for example, Carter and McCarthy 2006; Scott and Tribble 2006; and O’Keeffe et al. 2007) do include all n-grams, irrespective of size, in their studies and such an approach is important for a fuller understanding of the importance of these multi-word units in the language.

2. Why study multi-word units of meaning?

The study of multi-word units of meaning has led to many new and interesting findings which in turn have pedagogical implications. Some of these findings with regard to n-grams are described and discussed below.

Once the n-grams have been identified, researchers have classified them in terms of their structural patterns, functions and register/genre specificity. In a study of four corpora, each representing a different register (conversation, fiction, news and academic prose), Biber et al. (1999: 996–7) identify the most frequent n-grams (they use the term ‘lexical bundles’) in their data. They classify them based on the structural patterns they encompass – for example, personal pronoun plus lexical verb phrase (plus complement clause), pronoun/noun phrase (plus auxiliary) plus copula be (plus), noun phrase with post modifier fragment, and so on – along with the grammatical category of the final word in the n-gram (verb, pronoun, other function words, noun, etc.) (1999: 996–7). Carter and McCarthy (2006: 503–4) also focus on the structure of the n-grams (termed ‘clusters’) in their corpus and most frequently find prepositions plus articles, subject plus verb, subject plus verb with complement items, and noun phrases plus of.

Studies of n-grams have sought to determine their functions. Carter and McCarthy (2006: 505 a–f) examine the functions which n-grams perform, and the list includes: relations of time and space, other prepositional relations, interpersonal functions, vague language, linking functions, and turn-taking. Biber et al. (1999) also categorise n-grams based on their discourse functions. They arrive at four main categories: referential bundles, text organisers, stance bundles and interactional bundles. The first two are more frequently found in academic discourse while the others are more widespread in conversation. Referential bundles include time, place and text markers, such as at the beginning of, the end of the, or at the same time, whereas text organisers express, for example, contrast (e.g. on the other hand), inference (e.g. as a result of) or focus (e.g. it is important to). Stance bundles convey attitudes towards some proposition, such as I don’t know why and are more likely to, and interactional bundles signal, for example, politeness, or are used in reported speech, as in thank you very much and and I said to him.

Firth does not apply his notion of meaning by collocations to a corpus in the modernday sense, but he does observe that the value of ‘the study of the usual collocations of a particular literary form or genre or of a particular author makes possible a clearly defined and precisely stated contribution to what I have termed the spectrum of descriptive linguistics’ (Firth 1957: 195). He conducts what must be the earliest diachronic genre-based study of collocation. In his study, Firth examines the use of collocation in a collection of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century letters in order to determine which collocations remain current and which ‘seem glaringly obsolete’ (ibid.: 204). He finds a number of collocates no longer in use, for example, disordered and cold (as in the illness) in I have been disordered by a cold, and others which are still collocates today, for example, criminally and neglected in you are not to think of yourself forgotten, or criminally neglected’ (1957: 204–5). This interest in register and genre specific usage of multi-word units has been the focus of a number of studies in recent years (see, for example, Biber et al. 1999; Cortes 2002; Carter and McCarthy 2006; Nesi and Basturkmen 2006; Scott and Tribble 2006; O’Keeffe et al. 2007; Forchini and Murphy 2008; Hyland 2008).

Biber et al. (1999, 2004), Carter and McCarthy (2006) and Hyland (2008), for example, have all found that the analysis of the n-grams in a register or genre affords an important means of differentiation. Thus the functions performed by n-grams identified by Carter and McCarthy (2006), and described above, differentiate spoken and written language. For example, the use of n-grams to express time and place relations, often by means of prepositional phrases, is more commonplace in written discourse (2006: 505a). They give the examples of I’ll see you in the morning, she sat on the edge of the bed and in the middle of the night. Another function, more often associated with written discourse, is the use of n-grams such as of a/the, to the and with a/the, which writers use when describing possession, agency, purpose, goal and direction (2006: 505b). One more function more frequently found in written discourse is that of linking, especially in written language that is complex in structure, which is exemplified by n-grams such as at the same time, in the first place and as a result of (2006: 505e). Spoken discourse also has its distinctive functions typified by specific n-grams and Carter and McCarthy (2006: 505c) find that the use of n-grams to reflect interpersonal meanings is one such function. Examples of these n-grams are you know, I don’t know, I know what you mean and I think. Being vague is also more frequently found in spoken discourse (2006: 505d), whether it is because the speaker cannot be specific or the context does not require specificity. Again, Carter and McCarthy (2006: 505d) identify frequently occurring n-grams which express vagueness and these include kind of, sort of thing, (or) something like that, (and) all the rest of it and this, that and the other.

Academic genres have attracted a disproportionate amount of interest compared with other genres (see, for example, Cortes 2002, 2004; Biber et al. 2004; Charles 2006; Nesi and Basturkmen 2006; Hyland 2008). These studies have all served to demonstrate how a detailed examination of n-grams can reveal genre-specific features in language use. It is now well known that academic language contains distinctive high-frequency n-grams which characterise the conventions of academic spoken and written discourses, as well enabling us to better appreciate differences between the various disciplines. Examples of n-grams typical of academic language include: for example, the importance of and in the case of (Carter and McCarthy 2006: 505g).

Scott and Tribble (2006: 132) argue that clusters provide insights into the phraseology used in different contexts and they examine the top forty three- and four-word n-grams in the whole of the British National Corpus (BNC), and three sub-corpora within the BNC (i.e. conversations, academic writing and literary studies periodical articles). The top ten n-grams for the whole of the BNC and the sub-corpora (2006: 139–40) show that while the top four three-word n-grams are the same for the whole of the BNC and the conversations (a lot of, be able to, I don’t know and it was a), the top four in academic writing, and literary studies periodical articles are different, although these two subcorpora have a number of overlapping n-grams in the top ten (as well as, in terms of, it is a, it is not and one of the).

Scott and Tribble find that certain structures occur with differing frequencies across the four corpora and they investigate one particular structure – noun phrase with of-phrase fragment – as in one of the. They demonstrate how the most frequent right collocates of this n-gram comprise an important set of terms in academic discourse (2006: 141). Examples (the rankings are given in brackets) of these genre-specific n-grams are one of the most (1), one of the main (2), one of the major (3), one of the first (4), and one of the reasons (7), one of the parties (8), one of the earliest (10) and one of the problems (11). With the exception of one of the most, all of these n-grams are more frequently found in academic discourse.

While studies of n-grams make up the majority of the studies of multi-word units, another form of multi-word unit is the idiom, although the borderline between n-grams and idioms is not without ambiguity. O’Keeffe et al. (2007: 82–3) suggest useful methodologies for extracting idioms from a corpus given that idioms cannot be automatically identified by corpus linguistics software. They point out that certain words are ‘idiomprone’ (2007: 83) because they are ‘basic cognitive metaphors’ and give the examples of parts of the body, money, and light and colour. They illustrate one method by first searching for face in CANCODE and then studying the 520 concordance lines which revealed fifteen different idioms: for example, let’s face it, on the face of it, face to face and keep a straight face (2007: 83). The second method is to first sample texts from the corpus in order to study them qualitatively to identify idioms. The idioms found are then searched for in the corpus as whole. This method has led to the identification of many idioms in CANCODE and the five most frequently occurring are fair enough, at the end of the day, there you go, make sense and turn round and say (2007: 85). Also, idioms, like n-grams, can be described in terms of their functions and register- and genre-specificity (McCarthy 1998).

3. From n-grams to phraseological variation

The criticism from Sinclair (2001: 351–2) that the practice of only examining longer ngrams of three words or more neglects by far the largest group, i.e. two-word n-grams which, based on their prevalence, merit the most attention, has already been mentioned. However, Sinclair’s (2001) criticism of n-gram studies does not end there. He raises other issues which question the extent to which the concentration on examining n-grams has led to other forms of multi-word units being overlooked. He points out that the ‘classification of the bundles is by the number of words in a string, there is no recognition of variability of exponent or of position or of discontinuity’ (2001: 353). He also criticises attempts to relate n-grams to ‘the nearest complete grammatical structure’ because ‘reconciliation with established grammatical units is doomed to fail’ (2001: 353). His reason for this prediction is that ‘a grammar must remain aware of lexis, and that the patterns of lexis cannot be reconciled with those of a traditional grammar’ (2001: 353).

It should be noted that at least some of the limitations of concentrating on the study of n-grams have not gone unnoticed by some engaged in such studies. Nesi and Basturkmen (2006), for example, point out that the identification of n-grams ‘does not permit the identification of discontinuous frames (for example, not only … but also … )’ (ibid.: 285). Similarly, Biber et al. (2004: 401–2) state that one of their research goals ‘is to extend the methods used to identify lexical bundles to allow for variations on a pattern’. However, they point out that the problem with undertaking this more comprehensive kind of study is in ‘trying to identify the full range of lexical bundles across a large corpus of texts’.

Sinclair’s criticisms raise fundamental issues about what he terms the phraseological tendency in language (1987), and he proposes his own model for identifying and describing ‘extended unit of meanings’,or‘lexical items’ (1996 and 1998). Sinclair later expresses a preference for the term ‘meaning shift unit’ rather than ‘lexical item’ (Sinclair 2007a; Sinclair and Tognini Bonelli, in press). The lexical item is taken to ‘realize an element of meaning which is the function of the item in its cotext and context’ (Sinclair 2004b: 121) and is ‘characteristically phrasal, although it can be realized in a single word’ (2004b: 122). It is made up of five categories of co-selection, namely the core, semantic prosody, semantic preference, collocation and colligation. The core and the semantic prosody are obligatory, while collocation, colligation and semantic preference are optional. The core is ‘invariable, and constitutes the evidence of the occurrence of the item as a whole’ (Sinclair 2004b: 141): that is, the word(s) is always present. Semantic prosody is the overall functional meaning of a lexical item and provides information about ‘how the rest of the item is to be interpreted functionally’ (2004b: 34). Collocation and colligation are related to the co-occurrences of words and grammatical choices with the core, respectively (2004b: 141). The semantic preference of a lexical item is ‘the restriction of regular co-occurrence to items which share a semantic feature, e.g. about sport or suffering’ (ibid.: 142). These co-selections are also described in terms of the process by which they are selected. It is the selection of semantic prosody by the speaker that then leads to the selection of the core and the other co-selections of a lexical item.

Clearly, Sinclair’s lexical item encompasses much more than we might find in lists of n-grams, but how do we find these co-selections in a corpus? This question links back to the problem raised by Biber et al. (2004) in looking for variations in their n-grams. Cheng et al. (2006) have developed the means to fully automatically retrieve the coselections which comprise lexical items from a corpus. The corpus linguistics software is ConcGram (Greaves 2009) and the products of its searches are concgrams (Cheng et al. 2006, 2009). These researchers argue that it is important to be able to identify lexical items without relying on single-word frequency lists, lists of n-grams or some form of user-nominated search. The reasons for this are that single-word frequencies are not a reliable guide to frequent phraseologies in a corpus, and n-grams miss instances of multiword units that have constituency (AB, A*B, A**B, etc.) and/or positional (AB, BA, B*A, etc.) variation (Cheng et al. 2006). While there are programs available which find skipgrams (Wilks 2005) and phrase-frames (Fletcher 2006), which both capture a limited amount of constituency variation, they still miss many instances of both constituency and positional variation (Cheng et al. 2006). ConcGram identifies all of the co-occurrences of two or more words irrespective of constituency and/or positional variation fully automatically with no prior search parameters entered and so it supports corpus-driven research (Tognini Bonelli 2001).

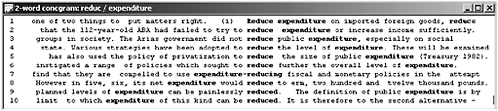

Cheng et al. (2009) distinguish between ‘co-occurring’ words (i.e. concgrams) and ‘associated’ words (i.e. phraseology) because, while ConcGram identifies all of the co-occurrences of words in a wide span, not all of these instances are necessarily meaningfully associated. In order to illustrate the difference between a typical concordance display and a concgram concordance, a sample of the two-word concgram ‘expenditure/reduce’ is given in Figure 16.1. All of the examples of concgrams are from a five-million-word sample of the British National Corpus (three million written and two million spoken).

The concordance lines in Figure 16.1 illustrate the benefits of uncovering the full range of phraseological variation as the search for this particular concgram found thirtyeight instances, but only four of the thirty-eight are n-grams. Another interesting point is

Figure 16.1 Sample concordance lines for ‘expenditure/reduce’.

that while there are forty-two instances of ‘expenditure/increase’ in this corpus, there is only one instance of ‘decrease/expenditure’, and so while reduce and expenditure are collocates, expenditure and decrease are an example of lexical repulsion (Renouf and Banerjee 2007). By not simply focusing on the node, concgram concordance lines highlight all of the co-occurring words, which shifts the reader’s focus of attention away from the node to all of the words in the concgram.

Studies of concgrams suggest that they help in the identification of three kinds of multi-word units (Warren 2009). These are collocational frameworks (Renouf and Sinclair 1991), meaning shift units (also termed ‘lexical items’; Sinclair 1996, 1998) and organisational frameworks.

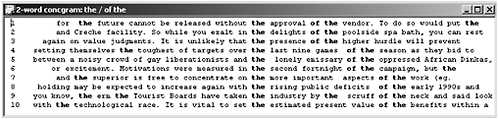

It is well known that so-called ‘grammatical’ or ‘function’ words top single-word frequency lists and it is therefore no surprise that these words also top concgram frequency lists. Renouf and Sinclair (1991) call the co-selections of these words ‘collocational frameworks’ and, even though they are such common multi-word units, they are rarely studied. Initial studies of concgrams to find collocational frameworks (Greaves and Warren 2008; Li and Warren 2008) show that the five most frequent are the … of, a/an … of, the … of the, the … in and the … to (Li and Warren 2008). A sample of one of the most frequent collocational frameworks is in Figure 16.2.

The widespread use of collocational frameworks suggests that they deserve greater attention from researchers, teachers and learners. As long ago as 1988, Sinclair and Renouf (1988) argued that they should be included in a lexical syllabus, but to date they remain overlooked. Newer grammars based on corpus evidence list and describe n-grams (see, for example, Biber et al. 1999; Carter and McCarthy 2006). For example, Carter and McCarthy (2006: 503–5) list four-word n-grams in written texts including: the end of the, the side of the, the edge of the, the middle of the, the back of the, the top of the and the bottom of the. If collocational frameworks are to be included in future grammars, these n-grams might in future be preceded by a description of their three-word collocational framework, the … of the.

Figure 16.2 Sample concordance lines for the collocational framework the … of the.

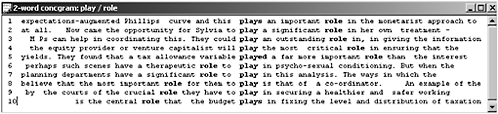

The idea behind searching for concgrams was to be able to identify and describe meaning shift units (Sinclair 2007a). These multi-word units are important for a fuller description of phraseology and Cheng et al. (2009) outline a procedure for analysing concgrams which can help to identify meaning shift units. They analyse the two-word concgram ‘play/role’ and a sample of the concordance lines is in Figure 16.3.

In their study (Cheng et al. 2009), all of the concordance lines of ‘play/role’ are studied and all the concgram configurations and their frequencies are described. The canonical form is identified and its meaning described. In Figure 16.3, the canonical form is exemplified in lines 1–3 which is the most frequent configuration. The canonical form is then used as a benchmark for all of the other concgram configurations, and the result is a ranking of the concgram configurations based on the extent of their adherence to the canonical form. At the end of this process, a meaning shift unit is identified and described with all of its potential variations which together comprise a ‘paraphrasable family with a canonical form and different patterns of co-selection’ (Cheng et al. 2009).

There is a type of multi-word unit which can exhibit extreme constituency variation. Hunston (2002: 75) briefly describes such multi-word units and provisionally labels them ‘clause collocations’. They are the product of the tendency for particular types of clause to co-occur in discourses. She provides an example, I wonder … because, where I wonder and because link clauses in the discourse (ibid.: 75). Hunston points out that such collocations are difficult to find because the I wonder clause can contain any number of words (ibid.: 75). Based on the distinction between organisation-oriented elements and message-oriented elements used in linear unit grammar (Sinclair and Mauranen 2006), Greaves and Warren (2008) term these multi-word units ‘organisational frameworks’ to denote the ways in which organisational elements in the discourse, such as conjunctions, connectives and discourse particles, can be co-selected. Searches for concgrams uncover organisational frameworks because they retrieve co-occurring words across a wide span. Sample concordance lines of the organisational framework I think … because are given in Figure 16.4.

Figure 16.3 Sample concordance lines for the meaning shift unit ‘play/role’.

Figure 16.4 Sample concordance lines for the organisational framework I think … because.

Some instances of organisational frameworks are well known, and are sometimes listed in grammars as ‘correlative conjunctions’, for example, either … or, not only … but also and both … and. There are others, however, such as I think … because and Hunston’s I wonder … because, which are not so familiar, and possibly others which are currently unknown, which deserve more attention.

There has been considerable interest in keywords and the notion of keyness (see Scott, in this volume) in corpus linguistics (see, for example, Scott and Tribble 2006). Given that multi-word units are so pervasive in language, concgrams can be used to extend the notion of keyness beyond individual words to include the full range of multi-word units. They are a starting point for quantifying the extent of phraseology in a text or corpus and determining the phraseological profile of the language contained within it. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that n-grams, including those made up entirely of grammatical words, can be genre-sensitive, which has been described earlier, and there is evidence that this is also the case for concgrams. Early studies using concgrams to examine the aboutness of texts and corpora (see Tognini Bonelli 2006; Greaves and Warren 2007; Cheng 2008, 2009; Milizia and Spinzi 2008; O’Donnell et al. 2008) suggest that these multi-word units offer a more comprehensive phraseological profile of texts and corpora. Word associations which are specific to a text or corpus are termed ‘aboutgrams’ (Sinclair, personal communication; Sinclair and Tognini Bonelli, in press).

4. What has corpus research into multi-word units told us about phraseology that we did not know before?

As observed by Stubbs (2005), although many of the studies of n-grams, phrasal constructions and extended lexical units involve research within quite different methodological traditions, they have arrived at similar conclusions about ‘how to model units of meaning’ (2005: 8). We now know much more about the key role played by multi-word units in the English language and this has resulted in a reappraisal of the status of lexis.

Biber et al. (1999: 995) find that 45 per cent of the words in their conversation corpus occur in recurrent n-grams of two or more words. They set the cut-off at twenty per million to arrive at this percentage. Altenberg (1998) puts the percentage as high as 80 per cent by including all n-grams that occur more than once. Whatever the percentage, these findings provide conclusive evidence for the ‘phraseological tendency’ (Sinclair 1987) in language. However, it needs to be borne in mind that both these figures exclude multi-word units with constituency and or positional variation, and we are now only just beginning to realise that only looking at n-grams leaves much of the phraseological variation in English undiscovered. If phraseological variation is added to the percentage of n-grams in a corpus, the figure would be closer to 100 per cent.

The findings from studies of multi-word units have impacted lexicography along with the writing of English language grammars, and English language textbooks generally. The reason why many of the findings have fed into the fields of English for Academic Purposes and English for Specific Purposes is that studies have also been conducted which compare the use of multi-word units by expert and novice writers and speakers. For example, Cortes (2004) makes the point that the use of multi-word units, in the forms of collocations and fixed expressions associated with particular registers and genres, are a marker of proficient language use in that particular register or genre. Similarly, in his study of four-word n-grams, Hyland (2008: 5) states that these multi-word units are ‘familiar to writers and readers who regularly participate in a particular discourse, their very “naturalness” signalling competent participation in a given community’.Hefinds that the opposite is often true of novice members of the community and the absence of discipline-specific n-grams might signal a lack of fluency. This means that learners need to acquire an ‘appropriate disciplinary-sensitive repertoire’ of n-grams (Hyland and Tse 2007).

Another indication that our understanding of language has been enhanced by research into multi-word units is the notion of ‘lexical priming’ put forward by Hoey (2005) as a new theory of language which builds on the five categories of co-selection (Sinclair 1996, 1998, 2004a) and argues that patterns of co-selection require that speakers, writers, hearers and readers are primed for appropriate co-selections.

A word is acquired by encounters with it in speech and writing. A word becomes cumulatively loaded with the contexts and co-texts in which they are encountered. Our knowledge of a word includes the fact that it co-occurs with certain other words in certain kinds of context. The same process applies to word sequences built out of these words; these too become loaded with the contexts and co-texts in which they occur.

(Hoey 2005: 8)

In support of the notion of lexical priming, Hoey puts forward ten priming hypotheses (2005: 13). Every word is primed to occur with particular other words, semantic sets, pragmatic functions and grammatical positions. Words which are either co-hyponyms or synonyms differ with respect to their collocations, semantic associations and colligations, as do the senses of words which are polysemous. Words are primed for use in one or more grammatical roles and to participate in, or avoid, particular types of cohesive relation in a discourse. Every word is primed to occur in particular semantic relations in the discourse and to occur in, or avoid, certain positions within the discourse. These hypotheses are a result of Hoey’s extensive study of lexical cohesion and he concludes that naturalness depends on speakers and writers conforming to the primings of the words that they use (2005: 2–5).

5. Implications and future research

Findings from the study of multi-word units have implications for the learning and teaching of applied linguistics, language studies, English for Academic Purposes and English for Specific Purposes. It is clear that multi-word units have a role to play in datadriven learning (DDL) activities (Johns 1991), and should further advance the learning and teaching of phraseology.

Sinclair’s claim that ‘a grammar must remain aware of lexis, and that the patterns of lexis cannot be reconciled with those of a traditional grammar’ (2001: 353) predicts a break with traditional grammar and this prediction is made elsewhere by Sinclair and is summed up in the following quote:

By far the majority of text is made of the occurrence of common words in common patterns, or in slight variants of those common patterns. Most everyday words do not have an independent meaning, or meanings, but are components of a rich repertoire of multi-word patterns that make up a text. This is totally obscured by the procedures of conventional grammar.

Sinclair (1991: 108)

The inadequacies of conventional grammar have been addressed, at least in part, by Sinclair and Mauranen’s (2006) linear unit grammar which ‘avoids hierarchies, and concentrates on the combinatorial patterns of text’. Sinclair (2007b) also advocates local grammars as a better way of handling phraseological variation. Both local grammars and linear unit grammar have yet to be widely applied in studies of multi-word units, but Hunston and Sinclair (2000), for example, demonstrate the applicability of a local grammar to the concept of evaluation, and these grammars have considerable potential in furthering our descriptions and understanding of multi-word units.

Another of Sinclair’s yet-to-be-realised ambitions is the compilation of a dictionary which fully captures the phraseology of language. ‘A dictionary containing all the lexical items of a language, each one in its canonical form with a list of possible variations, would be the ultimate dictionary’ (Sinclair in Sinclair et al. 2004: xxiv). As our knowledge of phraseology grows with the study of multi-word units, such a dictionary becomes ever more feasible.

Sinclair (2001: 357) states that for him any corpus ‘signals like a flashing neon sign “Think again”’ and it is Sinclair’s notion of the idiom principle (1987) and his work on units of meaning which have led all of us to think again about whether meaning is in individual words or whether the source of meaning in language is through the coselections made by speakers and writers. All of the corpus evidence confirms Sinclair’s fundamental point that it is not the word that is a unit of meaning, but the co-selection of words which comprise a unit of meaning (2001: xxi). The future exploration of multiword units in corpus linguistics promises to tell us much more about how meaning is created.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support we received from Professor John McHardy Sinclair who was a member of the concgram team and worked with us on concgrams from the outset. His brilliant ideas led directly to many of ConcGram’s functions and helped enormously in our analyses of concgrams. Another member of the team is Elena Tognini Bonelli whose research into aboutness has helped in further developing the applications of concgramming. Winnie Cheng, of course, is also in the team and her input has been invaluable.

The work described in this chapter was substantially supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Project No. PolyU 5459/08H, B-Q11N)

Further reading

Cheng, W., Greaves, C., Sinclair, J. and Warren, M. (2009) ‘Uncovering the Extent of the Phraseological Tendency: Towards a Systematic Analysis of Concgrams’, Applied Linguistics 30(2): 236–52. (This paper explains how to analyse the phraseological variation to be found in concgram outputs.)

Granger, S. and Meunier, F. (eds) (2008) Phraseology: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. (This is a wide-ranging collection of papers by leading researchers in the field.)

O’Keeffe, A., McCarthy, M. J. and Carter, R. A. (2007) From Corpus to Classroom: Language Use and Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (This book has a number of chapters which explore the forms and function of multi-word units.)

Sinclair, J. (2004) Trust the Text. London: Routledge. (Chapters 2 and 8 provide a good account of Sinclair’s notion that a lexical item is comprised of up to five co-selections.)

Stubbs, M. (2009) ‘The Search for Units of Meaning: Sinclair on Empirical Semantics’, Applied Linguistics 30(1): 115–37. (This is a good overview of current ‘Sinclairian’ corpus linguistics research in phraseology with a thought-provoking discussion on its implications.)

References

Altenberg, B. (1998) ‘On the Phraseology of Spoken English: The Evidence of Recurrent Word Combinations’, in A. P. Cowie (ed.) Phraseology: Theory Analysis and Applications. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 101–22.

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S. and Finegan, E. (1999) The Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Harlow, England: Pearson Education.

Biber, D., Conrad, S. and Cortes, V. (2004) ‘If You Look at … : Lexical Bundles in University Teaching and Textbooks’, Applied Linguistics 25(3): 371–405.

Carter, R. A. and McCarthy, M. J. (2006) Cambridge Grammar of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Charles, M. (2006) ‘Phraseological Patterns in Reporting Clauses Used in Citation: A Corpus-Based Study of Theses in Two Disciplines’, English for Specific Purposes 25(3): 310–31.

Cheng, W. (2008) ‘Concgramming: A Corpus-driven Approach to Learning the Phraseology of Discipline-specific Texts’, CORELL: Computer Resources for Language Learning 1(1): 22–35.

——(2009) ‘Income/Interest/Net: Using Internal Criteria to Determine the Aboutness of a Text in Business and Financial Services English’, in K. Aijmer (ed.) Corpora and Language Teaching. Amsterdam/ Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 157–77.

Cheng, W. and Warren, M. (2008) ‘// -> ONE country two SYStems //: The Discourse Intonation Patterns of Word Associations’, in A. Ädel and R. Reppen (eds) Corpora and Discourse: The Challenges of Different Settings. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 135–53.

Cheng, W., Greaves, C. and Warren, M. (2006) ‘From n-gram to skipgram to concgram,’ International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 11(4): 411–33.

Cheng, W., Greaves, C., Sinclair, J. and Warren, M. (2009) ‘Uncovering the Extent of the Phraseological Tendency: Towards a Systematic Analysis of Concgrams’, Applied Linguistics 30(2): 236–52.

Cortes, V. (2002) ‘Lexical Bundles in Freshman Composition’, in D. Biber, S. Fitzmaurice and R. Reppen(eds) Using Corpora toExplore Linguistic Variation. Philadelphia, PA:John Benjamins, pp. 131–45.

——(2004) ‘Lexical Bundles in Published and Student Disciplinary Writing: Examples from History and Biology’, English for Specific Purposes 23(4): 397–423.

Coulthard, M. (2004) ‘Author Identification, Idiolect, and Linguistic Uniqueness’, Applied Linguistics 25 (4): 431–47.

Coulthard, M. and Johnson, A. (2007) An Introduction to Forensic Linguistics: Language in Evidence. London: Routledge.

Firth, J. R. (1957) Papers in Linguistics 1934–1951. London: Oxford University Press.

Fletcher, W. H. (2006) ‘Phrases in English’, home page, at http://pie.usna.edu/ (accessed 15 February 2006).

Forchini, P. and Murphy, A. (2008) ‘N-Grams in Comparable Specialized Corpora: Perspectives on Phraseology, Translation, and Pedagogy’. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 13(3): 351–67.

Granger, S. and Meunier, F. (eds) (2008) Phraseology in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 223–43.

Greaves, C. (2009) ConcGram 1.0: A Phraseological Search Engine. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Greaves, C. and Warren, M. (2007) ‘Concgramming: A Computer-Driven Approach to Learning the Phraseology of English’, ReCALL Journal 17(3): 287–306.

——(2008) ‘Beyond Clusters: A New Look at Word Associations’, IVACS 4, 4th International Conference: Applying Corpus Linguistics, University of Limerick, Ireland, 13–14 June.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1966). ‘Lexis as a Linguistic Level’, in C. E. Bazell, J. C. Catford, M. A. K. Halliday and R. H. Robins (eds) In Memory of J. R. Firth. London: Longmans.

Hoey, M. (2005) Lexical Priming: A New Theory of Words and Language. London: Routledge.

Hunston, S. (2002) Corpora in Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hunston, S. and Francis, G. (2000) Pattern Grammar: A Corpus-driven Approach to the Lexical Grammar of English. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hunston, S. and Sinclair, J. (2000) ‘A Local Grammar of Evaluation’, in S. Hunston and G. Thompson (eds) Evaluation In Text: Authorial Stance and the Construction of Discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 75–100.

Hyland, K. (2008) ‘As Can Be Seen: Lexical Bundles and Disciplinary Variation’, English for Specific Purposes 27(1): 4–21.

Hyland, K. and Tse, P. (2007) ‘Is There an “Academic Vocabulary”?’ TESOL Quarterly, 41(2): 235–53.

Johns, T. (1991) ‘Should You Be Persuaded: Two Samples of Data-driven Learning Materials’,in T. Johns and P. King (eds) Classroom Concordancing. Birmingham: English Language Research, Birmingham University, pp. 1–16.

Li, Y. and Warren, M. (2008) ‘in. … of: What Are Collocational Frameworks and Should We Be Teaching Them?’ 4th International Conference on Teaching English at Tertiary Level. Zhejiang, China, 11–12 October.

McCarthy, M. J. (1998) Spoken Language and Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Milizia, D. and Spinzi, C. (2008) ‘The “Terroridiom” Principle Between Spoken and Written Discourse’, International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 13(3): 322–50.

Nesi, H. and Basturkmen, H. (2006) ‘Lexical Bundles and Signalling in Academic Lectures’,in J. Flowerdew and M. Mahlberg (eds) ‘Lexical Cohesion and Corpus Linguistics’, special issue of International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 11(3): 283–304.

O’Donnell, M. B., Scott, M. and Mahlberg, M. (2008) ‘Exploring Text-initial Concgrams in a Newspaper Corpus’, 7th International Conference of the American Association of Corpus Linguistics, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA, 12–15 March.

O’Keeffe, A., McCarthy, M. J. and Carter, R. A. (2007) From Corpus to Classroom: Language Use and Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Partington, A. (1998) Patterns and Meanings. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Renouf, A. and Banerjee, J. (2007) ‘Lexical Repulsion Between Sense-related Pairs’, International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 12(3): 415–44.

Renouf, A. and Sinclair, J. (1991) ‘Collocational Frameworks in English’, in K. Ajimer and B. Altenberg (eds) English Corpus Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 128–43.

Scott, M. and Tribble, C. (2006) Textual Patterns: Key Words and Corpus Analysis in Language Education. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Simpson, R. C. (2004) ‘Stylistic Features of Academic Speech: The Role of Formulaic Expressions’,in U. Connor and T. Upton (eds) Discourse in the Professions: Perspectives from Corpus Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 37–64.

Sinclair, J. (1966) ‘Beginning the Study of Lexis,’ in C. E. Bazell, J. C. Catford, M. A. K. Halliday and R. H. Robins (eds) In Memory of J. R. Firth. London: Longmans.

——(1987) ‘Collocation: A Progress Report’, in R. Steele and T. Threadgold (eds) Language Topics: Essays in Honour of Michael Halliday. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 319–31.

——(1991) Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

——(1996) ‘The Search for Units of Meaning’, Textus 9(1): 75–106.

——(1998) ‘The Lexical Item’, in. E. Weigand (ed.) Contrastive Lexical Semantics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 1–24.

——(2001) ‘Review of The Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English’, International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 6(2): 339–59.

——(2004a) Trust the Text. London: Routledge.

——(2004b) ‘Meaning in the Framework of Corpus Linguistics’, Lexicographica 20: 20–32.

——(2005) ‘Document Relativity’ (manuscript), Tuscan Word Centre, Italy.

——(2006) ‘Aboutness 2’ (manuscript), Tuscan Word Centre, Italy.

——(2007a) ‘Collocation Reviewed’ (manuscript), Tuscan Word Centre, Italy.

——(2007b) ‘Defining the Definiendom – New’ (manuscript), Tuscan Word Centre, Italy.

Sinclair, J. and Mauranen, A. (2006) Linear Unit Grammar. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Sinclair, J. and Renouf, A. (1988) ‘A Lexical Syllabus for Language Learning’, in R. A. Carter and M. J. McCarthy (eds) Vocabulary and Language Teaching. London: Longman, pp. 140–60.

Sinclair, J. and Tognini Bonelli, E. (in press) Essential Corpus Linguistics. London: Routledge.

Sinclair, J., Jones, S. and Daley, R. (1970) ‘English Lexical Studies,’ report to the Office of Scientific and Technical Information.

——(2004) English Collocation Studies: The OSTI Report. London: Continuum.

Stubbs, M. (1995) ‘Collocations and Cultural Connotations of Common Words’, Linguistics and Education 7(3): 379–90.

——(2001) Words and Phrases: Corpus Studies of Lexical Semantics. Oxford: Blackwell.

——(2005) ‘The Most Natural Thing in the World: Quantitative Data on Multi-word Sequences in English’, paper presented at Phraseology 2005, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 13–15 October.

Teubert, W. (ed). (2005) Corpus Linguistics-Critical Concepts in Linguistics. London: Routledge.

Tognini Bonelli, E. (2001) Corpus Linguistics at Work. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

——(2006) ‘The Corpus as an Onion: The CÆT Corpus Siena (a Corpus of Academic Economics Texts)’, International Seminar: Special and Varied Corpora, Tuscan Word Centre, Certosa di Pontignano, Tuscany, Italy, October.

Warren, M. (2009) ‘Why Concgram?’ in Chris Greaves (ed.) ConcGram 1.0: A Phraseological Search Engine. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 1–11.

Wilks, Y. (2005) ‘REVEAL: The Notion of Anomalous Texts in a Very Large Corpus’, Tuscan Word Centre International Workshop. Certosa di Pontignano, Tuscany, Italy, 1–3 July.