17

What can a corpus tell us about grammar?

Susan Conrad

1. Understanding grammar through patterns and contexts: moving from correct/incorrect to likely/unlikely

In traditional descriptions of grammar and in most linguistic theories, grammar is presented from a dichotomous perspective. Sample sentences are considered either grammatical or ungrammatical, acceptable or unacceptable, accurate or inaccurate (e.g. see discussions in Cook 1994). From this perspective, to describe the grammar of a language, all a researcher needs is a native speaker because any native speaker can judge grammaticality. To teach a language, teachers focus only on the rules for making grammatical sentences, and proficiency for second language speakers equates with accuracy.

This dichotomous view works well for certain grammatical features. For example, it is grammatically incorrect to have zero article before a singular count noun in English: *I saw Ø cow. Aside from a few exceptions such as in the locative prepositional phrases at home or in hospital, this rule is absolute. However, any reflective language user will realise that many other grammatical choices cannot be made on the basis of correct/incorrect. For example, in the previous sentence the that could have been omitted: … will realise many other grammatical choices … Both versions are equally grammatical.

Of course, for decades, work in sociolinguistics and from a functional perspective has emphasised language choices for different contexts. In language classes, students may have been taught a few variants for politeness (e.g. in English using could you … for requests instead of can you … ), but descriptions of grammar remained focused on accuracy. In a 1998 address to the international TESOL convention, Larsen-Freeman sought to ‘challenge the common misperception that grammar has to do solely with formal accuracy’, arguing instead for a ‘grammar of choice’ (Larsen-Freeman 2002). Being able to describe the typical choices that language users make, however, requires doing largescale empirical analyses. The analyses must be empirical – rather than introspective – since language users often are not consciously aware of their most typical choices. The analyses must cover numerous data in order to tell which language choices are widespread, which occur predictably although under rare circumstances, and which are more idiosyncratic.

The great contribution of corpus linguistics to grammar is that it increases researchers’ ability to systematically study the variation in a large collection of texts – produced by far more speakers and writers, and covering a far greater number of words, than could be analysed by hand. Corpus linguistic techniques allow us to determine common and uncommon choices and to see the patterns that reveal what is typical or untypical in particular contexts. These ‘patterns’ show the correspondence between the use of a grammatical feature and some other factor in the discourse or situational context (e.g. another grammatical feature, a social relationship, the mode of communication, etc.). Corpus linguistics therefore allows us to focus on the patterns that characterise how a large number of people use the language, rather than basing generalisations on a small set of data or anecdotal evidence, or focusing on the accurate/inaccurate dichotomy. As O’Keeffe et al. (2007) explain, corpus analyses lead us to describing grammar not just in structural terms, but in probabilistic terms – describing the typical social and discourse circumstances associated with the use of particular grammatical features.

This chapter reviews some major aspects of this new paradigm for describing grammar. The first section reviews the types of grammatical patterns typically covered in corpus studies. The chapter then discusses the investigation of numerous contextual factors simultaneously, the development of descriptions of the grammar of speech, and the most commonly discussed problem that arises in this new paradigm – the role of acceptability judgements. Throughout, points are exemplified with descriptions of English. The contributions of corpus linguistics are equally applicable to the grammar of any language; however, corpus-based descriptions of English far outnumber any other language. Furthermore, although numerous studies are mentioned, it is no coincidence that the chapter repeatedly cites two recent reference grammars of English, the Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English (Biber et al. 1999) and the Cambridge Grammar of English (Carter and McCarthy 2006). These comprehensive grammars make extensive use of corpus analyses to describe English structure and use, and are currently the single clearest manifestations of corpus linguistics’ impact on the study of grammar.

As a first step, before further discussing the contribution of corpus linguistics to grammar, a brief review of some methodological principles for corpus linguistic investigations of grammar is in order.

Methodological principles in corpus-based grammar analysis

Any analysis of ‘typical’ or ‘probable’ choices depends on frequency analysis. The very mention of a choice being ‘typical’ or ‘unusual’ implies that, under given circumstances, it happens more or less often than other choices. For reliable frequency analysis, a corpus does not necessarily have to be immense, but it must be designed to be as representative as possible (see the chapters in Section I of this volume) and as fine-grained as needed to describe the circumstances associated with the variable choices. For example, McCarthy and Carter (2001) explain the need for fine-grained distinctions in spoken corpora to describe when ellipsis is and is not common. They find ellipsis to be rare in narratives, while it is common in many other genres of talk. Any corpus that did not include numerous conversational genres or any analysis which neglected to differentiate among them would fail to discover this pattern.

Frequency counts are not sufficient for describing grammar, however. Instead, they point to interesting phenomena that deserve further investigation and interpretation. As Biber et al. (2004) explain,

we do not regard frequency data as explanatory. In fact we would argue for the opposite: frequency data identifies patterns that must be explained. The usefulness of frequency data (and corpus analysis generally) is that it identifies patterns of use that otherwise often go unnoticed by researchers.

(p. 176)

In corpus-based grammar studies, interpretations of frequency analyses come from a variety of sources. They can be based on cognitive principles such as the principle of ‘end weight’ (heavy, long constituents are harder to process than short constituents and so are placed at the ends of clauses); on aspects of linguistic theory, such as principles defined in Systemic Functional Linguistics; on the historical development of the language; or on reasonable explanations of the functions or discourse effect of a particular linguistic choice. Interpretation always includes human judgements of the impact of the language choices and speakers/writers’ (usually subconscious) motivations in making these choices. Thus, a corpus linguistics perspective on grammar has not made human judgements superfluous; it has actually expanded the judgements and interpretations that are made.

2. Types of grammatical patterns

This section describes and exemplifies the four types of patterns that are most common in corpus-based grammar analyses. Grammatical choices are associated with (1) vocabulary, (2) grammatical co-text, (3) discourse-level factors, and (4) the context of the situation.

Grammar–vocabulary associations (lexico-grammar)

Associations between grammar and vocabulary are often called ‘lexico-grammar.’ The connection between words and grammar was extensively studied in the Collins COBUILD project (e.g. see Sinclair 1991). Although designed initially as a lexicography project, it became clear that grammar and lexis were not as distinct as traditionally presented, and the project also resulted in a number of books presenting ‘pattern grammar’– explanations of grammatical structures integrated with the specific lexical items most commonly used in them (see Hunston and Francis 1999; Hunston, this volume). Although few publications now discuss grammar in its lexical patterns as extensively, lexico-grammatical relationships have been a common contribution of corpus studies.

One type of lexico-grammatical relationship concerns the lexical items that tend to occur with a particular grammatical structure. This type of pattern can be illustrated with verbs that are most common with that-clause objects, e.g. I guess I should go or The results suggest that there is no effect … A large number of verbs are possible with this structure. However, beyond looking at what is possible, corpus-based grammar references present findings for the verbs that are actually most commonly used (Biber et al. 1999: 668–70; Carter and McCarthy 2006: 511). The reference grammars explain that the common verbs are related to expressing speech and thought. For example, Biber et al. (1999) find that think, say and know are by far the most common verbs with that-clauses in both British and American conversation (with the addition of guess in American English conversation). They also find that the structure is less common overall with any verb in academic prose, but suggest and show are most common. Rather than reporting thoughts and feelings, the verb + that-clause structures in academic prose are used to report previous research, often with non-human entities acting as the subject, for example:

Reports suggest that in many subject areas, textbooks and materials are not available.

Thus, the frequency analyses reveal the lexico-grammatical patterns – that is, which verbs occur most commonly with that-clauses – and the interpretation for the frequency is that the most important function of this structure is to report thoughts, feelings, and in the case of academic prose, previous research.

Another type of lexico-grammatical relationship concerns the specific words that occur as a realisation of a grammatical function. A simple illustration is verb tense. Traditionally, a grammatical description would explain the form of tenses – e.g. that simple present tense in English is uninflected except in third person singular when -s is added, that past tense is formed with -ed for regular verbs, etc. In these traditional descriptions, there is no empirical investigation of the verbs that are most common in these tenses. In contrast, a modern corpus-based reference grammar can provide that information. For example, Table 17.1 displays the list of verbs that occur 80 per cent of the time in present tense, contrasted with those that occur 80 per cent of the time in past tense, as analysed in the Longman Spoken and Written English Corpus, a corpus of over forty million words representing conversation, fiction, newspapers, academic prose as well as some planned speech and general prose (see Biber et al. 1999: 25).

The verbs most strongly associated with present tense convey mental, emotional and logical states. Many of these are used in short, common expressions in conversations expressing the speaker’s mental or emotional state, for example:

It doesn’t matter.

Never mind.

I suppose.

Others, however, are used to describe the states of others or to make logical interpretations, as in these examples from newspaper texts:

The yield on the notes is slightly higher because of the ‘short’ first coupon date which means that investors will get their interest payment quicker.

Some experts doubt videotex will develop a following among the general public.

The verbs most strongly associated with past tense, on the other hand, convey events or activities, especially body movements and speech:

He shrugged and smiled distractedly …

… Paul glanced at him and grinned.

Not surprisingly, such descriptions are especially common for describing characters and actions in fiction writing.

The associations between a grammatical structure and lexical items can also be analysed in terms of the semantic characteristics of the lexical items, leading to what has been called an analysis of ‘semantic prosody’–the fact that certain structures tend to be associated with certain types of meaning, such as positive or negative circumstances (Sinclair 1991). For example, O’Keeffe et al. (2007: 106–14) provide an extended corpus-based analysis of get-passives (e.g. he got arrested). They show that the get-passive is usually used to express unfortunate incidences, manifest in the lexico-grammatical association of verbs such as killed, sued, beaten, arrested, burgled, intimidated, criticised and numerous others. None of these verbs is common individually, but as a group they form the most common type of verb. O’Keeffe et al. further point out, however, that the adverse nature of the get-passive is not only a matter of a simple lexico-grammatical pattern with verbs of a certain semantic category. Verbs that are not inherently negative can nonetheless convey adverse conditions when used with negation or in a discourse context that makes the adverse conditions clear.

O’Keeffe et al. (2007) also discuss the type of subjects usually found with get-passives (often human subjects – the people to whom the unfortunate incident happened) and the lack of adverbials in these clauses. The authors thus move into discussion of another type of pattern, the grammatical co-text.

Grammatical co-text

In addition to describing lexical items that are associated with a grammatical structure, corpus studies also investigate associations with other grammatical structures – that is, the extent to which a particular grammatical feature tends to occur with specific other grammatical features.

Grammatical descriptions in traditional textbooks sometimes make claims about the grammatical co-text of features, and corpus studies can provide empirical testing of these claims. One interesting example is provided by Frazier (2003), who investigated wouldclauses of hypothetical or counterfactual conditionals. Concerned about the way that ESL grammars virtually always present the would clause as adjacent to an if-clause, he examined the extent to which this was true in a combination of spoken and written corpora totalling slightly over a million words.

Interestingly, Frazier (2003) found that almost 80 per cent of the hypothetical/counterfactual would-clauses were not adjacent to an if-clause. Some of these clauses were part of continuing discourse that had been framed with an if-clause at a lengthy distance from the would-clause (thus connecting the grammatical structure to a larger discourse context, a factor discussed in the next section). The other clauses fell into several other categories of use, including those that were used with a tentative degree of commitment – e.g. in expressions such as ‘this would seem to indicate …’–or with emphatic negative statements – e.g. ‘a man would never do that’ (Frazier 2003: 454–5). The largest category of would-clauses without if-clauses were those that had implied, covert conditionals. It further turned out that these clauses tended to occur with certain other grammatical features. For example, the co-occurring grammatical features include infinitives and gerunds, as in these examples from Frazier (2003: 456–7):

If there is nothing evil in these things, if they get their moral complexion only from our feeling about them, why shouldn’t they be greeted with a cheer? To greet them with repulsion would turn what before was neutral into something bad.

Letting the administration take details off their hands would give them more time to inform themselves about education as a whole.

Frazier’s systematic corpus analysis thus highlights two aspects of grammatical co-text for hypothetical/counter-factual would-clauses: the traditional claim that they usually occur with if-clauses is not true, but they do often occur with infinitives and gerunds (among other features described in the study).

Looking at grammatical co-occurrence patterns can also help to explain when rare constructions occur. For example, subject position that-clauses, as illustrated here, are very rare:

That there are no meteorites of any other age, regardless of when they fell to Earth, suggests strongly that all meteorites originated in other bodies of the solar system that formed at the same time that the Earth did.

(Biber et al. 1999: 677)

Considering constructions both with that- and the fact that-, subject position clauses occur about twenty to forty times per million words in academic prose and newspapers, and almost never occur in conversation, while that-clauses in other positions occur over 2,000–7,000 times per million words in the different registers (Biber et al. 1999: 674–6). These subject position clauses are obviously harder for listeners or readers to process, since they have a long constituent before the main verb. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that the subject position clauses tend to occur when the predicate of the sentence has another heavy, complex structure – a complicated noun phrase or prepositional phrase, or a complement clause, as in the above example. In addition, these clauses tend to be used in particular discourse contexts, a topic further discussed in the next section.

Discourse-level factors

Because many people’s introduction to corpus linguistics is with simple concordance searches, they sometimes believe that corpus linguistics has little to offer discourse-level study. However, this clearly is not the case (see further Conrad 2002; Thornbury, this volume).

Many of the examples in the previous sections have noted associations that were found by analysing text at the discourse level, rather than considering only discrete lexical or grammatical features. Determining the semantic prosody of get-passives, for instance, required considering discourse context. Another perspective is added by further analysis of subject-position that-clauses, which shows that they are associated with information structuring in the discourse. That is, when that-clauses are in subject position, they tend to restate information that has already been mentioned or implied in the previous discourse. The subject clauses thus provide an anaphoric link. Fuller context for the example in the last section illustrates this pattern:

One of the triumphs of radioactive dating emerged only gradually as more and more workers dated meteorites. It became surprisingly apparent that all meteorites are of the same age, somewhere in the vicinity of 4.5 billion years old … That there are no meteorites of any other age, regardless of when they fell to Earth, suggests strongly that all meteorites originated in other bodies of the solar system that formed at the same time that the Earth did.

Analysis of discourse-level factors affecting grammar often requires interpreting meaning, organisation, and information structure in texts, as in the example above. Such analysis is part of the more qualitative, interpretive side of a corpus study, focusing on how a grammatical structure is used in context. However, it is also possible to design a corpus-based study that uses computer-assisted techniques to track a grammatical feature’s occurrence throughout texts in order to describe its use on a discourse-level. These studies generally require writing specialised computer programs, rather than using commercially available software. Burges (1996) describes such a study, using computational analysis to track how writers refer to their audience (e.g. I, you, faculty) in memos that are written to groups of superiors, inferiors or those of equal hierarchical standing in institutions. She finds that the choices that writers make between nouns and pronouns and their level of prominence (in theme or rheme position) constructs and manipulates the writers’ authority as the memo progresses. A similar technique is exemplified in Biber et al. (1998: Ch. 5). They map the choice of verb tense and voice throughout science research articles, finding that areas of numerous shifts – i.e. when occurrences of verbs alternate between active and passive voice, or between past and present – correspond to transition zones that are of particular rhetorical interest.

Overall, few studies have used this approach of mapping the use of a grammatical feature through a text. Nevertheless, the technique has great potential for increasing our understanding of grammatical features on a discourse level. From this perspective, the description of noun and pronoun selection, or of verb tense and voice, becomes far more a matter of rhetorical function and authorial power than typically found in traditional grammatical descriptions.

Context of the situation

A number of factors in the context of the situation may be associated with the choice of a particular grammatical feature. Sociolinguistic studies have long considered how language use is affected by audience, purpose, participant roles, formality of the situation, and numerous other social and regional characteristics, and corpus-based techniques can be applied in these areas (see Andersen, this volume). Thus far in studies of grammar, the most common perspective on variation has concerned registers (also called genres) – varieties associated with a particular situation of use and communicative purpose, and often identified within a culture by a specific name, such as academic prose, text messaging, conversation or newspaper writing.

Making comparisons across registers as part of a description of a grammatical feature has already been exemplified in a number of examples above. For instance, the discussion of verb + that-clause objects explained that the frequency of the structure and the most common lexico-grammatical associations differed between conversation and academic prose, with conversation using the structure to report thoughts and feelings, and academic prose using it to report research findings. Throughout the Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English (Biber et al. 1999) grammatical features are described with reference to their frequency and use in conversation, fiction writing, newspaper writing and academic prose. The Cambridge Grammar of English (Carter and McCarthy 2006) makes numerous comparisons between the use of features in speech and writing.

Other studies compare registers in more restricted domains. Grammatical features used in particular academic settings have received considerable attention. Numerous studies have used the Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English to analyse grammatical features in typical settings in an American university – e.g. Fortanet (2004) describes details of the pronoun we in lectures, and Louwerse et al. (2008) discuss the use of conditionals. Biber (2006: Ch. 4) compares numerous grammatical features across ten spoken and written registers from four American universities in the Spoken and Written Academic Language corpus.

Whether focused on restricted or general settings, studies that make comparisons across registers all demonstrate that it is usually misleading to characterise the frequency and use of a grammatical feature in only one way. Rather, accurate grammatical descriptions require describing differences across registers (see further Biber, this volume; Conrad 2000).

Traditional sociolinguistic variables such as social class, ethnic group and age have been less studied in corpus-based grammar research. As Meyer (2002) explains, this is partly because of the difficulty of compiling a large spoken corpus that is representative of these different variables. Corpus-based studies of social variables have generally been large-scale regional comparisons such as British and American English differences (e.g. in various comparisons throughout Biber et al. 1999; Carter and McCarthy 2006: Appendix), or differences in varieties of world Englishes (Nelson 2006; Kachru 2008). The Bergen Corpus of London Teenage Language (a sub-corpus built from the British National Corpus) has made it possible to study some specific grammatical features of British teenager talk such as aspects of reported speech, some non-standard grammatical features, and the use of intensifiers (Stenström et al. 2002).

In the future, it is likely that new corpus projects will facilitate more study of the sociolinguistic variation of grammatical features (e.g. see Kretzschmar et al. 2006). However, as Kachru (2008) points out, roles and relationships are negotiated throughout a social interaction, and thus far, corpus techniques have not often been applied to studying these interpersonal dynamics. Specially written software programs could aid in the analysis of the interactions in a corpus that had social relationships thoroughly documented, and could add to our understanding of the most typical uses of specific grammatical features in the course of interactions. However, few researchers currently undertake the combination of computational analysis and intensive conversational analysis that would be required.

3. Investigating multiple features/conditions simultaneously

From the previous sections it is probably already apparent that it is often difficult to focus on only one type of pattern when explaining grammatical choices. There is often more than one contextual factor corresponding to the use of a particular feature. Without computer assistance for the analysis, it is often unfeasible to consider these multiple factors in a large number of texts simultaneously. Another contribution of corpus linguistics has been to describe more about the multiple factors that simultaneously have an impact on grammatical choices.

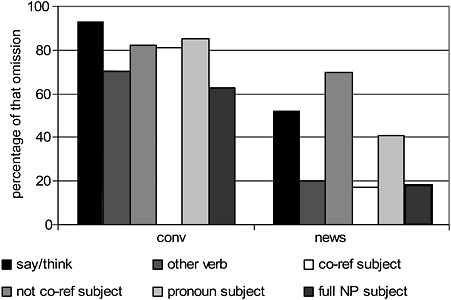

For example, consider the case of omitting the optional that in a that-complement clause – e.g. I think Ø I’ll go. Virtually any grammatical description includes the fact that the that is optional. Some textbooks for ESL students explain that it is especially common to delete it in speech (e.g. Azar 2002: 248). More detailed corpus analysis shows that the omission of that is actually associated with a number of factors (Biber et al. 1999: 681), as shown in Figure 17.1. One factor is a lexico-grammatical association: that is omitted more often when the verb in the main clause is say or think rather than any other verb. Two factors concern the grammatical co-text: (1) that is omitted more often when the main clause and complement clause have co-referential subjects (rather than subjects that refer to different entities), and (2) that is omitted more often when the that-clause has a personal pronoun subject rather than a full noun phrase. Another factor concerns the situational context, specifically the register: that is omitted more often in conversation than in newspaper writing generally, but the lexico-grammatical and grammatical co-text factors have a stronger effect in newspapers. That is, the choice of verb and subject types corresponds to a greater difference in percentage of that omission in newspapers than in conversation. In sum, corpus analysis shows that the choice of omitting or retaining that is much more complex than noted in traditional descriptions, but there are nonetheless identifiable patterns in the choice.

Two other approaches are also used for analysing multiple influences on grammatical choices. One is to consider a functional system within a language and describe factors that influence the grammatical features that are used to realise the system. For example, studies have included investigations of how metadiscourse is realised differently in different registers (e.g. Mauranen 2003a, 2003b) and how stance is conveyed grammatically across registers (Biber et al. 1999: Ch. 12; Biber 2004). The other approach is to study the grammar of a variety. In this approach the focus shifts from describing grammar to describing the variety, covering as many grammatical and lexical features as possible. This approach is covered by Biber (this volume).

Figure 17.1 Conditions associated with omission of that in that-clauses.

4. The grammar of speech

The above sections have all made mention of grammatical features in spoken discourse. Before corpus studies became popular, grammatical descriptions virtually always were based on written language (McCarthy and Carter 1995; Hughes and McCarthy 1998). Unplanned spoken language was neglected or, at best, considered aberrant, with its ‘incomplete’ clauses, messy repairs and non-standard forms. In contrast, corpus analyses have emphasised the fact that many features of speech directly reflect the demands of face-to-face interactions. Spoken grammar has become studied as a legitimate grammar, not a lacking form of written grammar.

One factor often noted for grammatical choices in conversation concerns the need to minimise imposition and be indirect. For example, Conrad (1999) discusses the common choice of though rather than however as a contrastive connector in conversation. Placed at the end of the clause and conveying a sense of concession more than contrast, the use of though is a less direct way to disagree than however is. A typical example in a conversation is as follows:

[Watching a football game, discussing a penalty call]

A: Oh, that’s outrageous.

B: Well, he did put his foot out though.

Speaker B clearly disagrees with A’s contention that the call is ‘outrageous’, but the use of though (along with the discourse marker well) downplays the disagreement. The desire to convey indirectness can also result in the use of verb tenses or aspects not normally found in writing. For example, McCarthy and Carter (2002: 58) describe the use of present progressive with verbs of desire, as when a customer tells a travel agent that she and her husband are wanting to take a trip. The use of present progressive makes the desire sound more tentative, and the request for help less imposing. Other features affecting the grammatical forms that are typical of face-to-face interactions include the shared context (and in many cases shared background knowledge), the expression of emotions and evaluations, and the constraints of real-time production and processing (see further the summary of factors and features in Biber et al. 1999: Ch. 14; and Carter and McCarthy 2006: 163–75).

Traditionally, the grammar of conversation has been thought to be simple when compared to writing. A further contribution of corpus studies, however, has been to show that there is grammatical complexity in conversation – but complexity of a particular sort. While expository writing tends to have complex noun phrases, conversation has more complexity at a clausal level. Even with limited time for planning ahead, speakers can produce highly embedded clauses, as in this speaker’s explanation of trying to find his cat:

[The trouble is [[if you’re the only one in the house] [he follows you] [and you’re looking for him] [so you can’t find him.]]] [I thought [I wonder [where the hell he’s gone]]] [I mean he was immediately behind me.]]

(Biber et al. 1999: 1068)

Although such utterances could be documented before the use of corpus techniques, it was only with the publication of corpus-based grammatical studies that the complexities of conversational grammar gained prominence. Corpus investigations of grammar also provide frequency information as evidence that certain complex structures are more common in conversation than writing. For example, that-clauses as complements of verbs and adjectives are over three times more common in conversation than academic prose (Biber et al. 1999: 675).

5. New challenges for judging acceptability

As the examples above have illustrated, corpus linguistics has given us the tools to describe the most typical grammatical choices that speakers and writer make. Even for structures that are relatively rarely used – such as subject position that-clauses – we can identify the specific conditions under which they are most typically used. However, describing grammatical choices in a more probabilistic way makes judgements about acceptability far more complex than they used to be. Further complicating these judgements is the fact that variation in grammatical choices exists not only through lexical, grammatical, discourse and situational context, as described in this chapter, but also for stylistic reasons (see Biber and Conrad, in press). Speakers and writers are also creative with language (see Vo and Carter this volume). Given this complexity, if a rare choice is attested in a corpus, how are we to determine whether it is just a rare choice or an error? Does a certain level of frequency imply acceptability – and if so, how would that level be determined? Interestingly, this issue of the relationship between corpus data and acceptability judgements is of most concern to two groups whose concerns often do not overlap: linguistic theorists and teachers.

Much linguistic theory is focused on describing what people know when they know the grammar of a language, and disagreement exists as to whether the empirical analysis of corpora has a role to play in determining that knowledge. Newmeyer (2003) views grammar and usage as distinct. He argues that ‘knowledge of grammatical structure is only one of many systems that underlie usage’ (p. 692). Since those ‘many systems’ are at play on any language produced in a real context, the only way to clearly investigate a person’s knowledge of grammatical structure is through intuition. In this view, corpus linguistics can shed light on usage, but not on grammaticality. Meyer and Tao (2005) counter, however, that intuition can only provide insight into one person’s individual grammar and thus analyses of corpora are important because they allow researchers to investigate what large numbers of people consider acceptable. Sampson (2007) argues that basing scientific inquiry on subjective knowledge and intuition is an outdated practice, and thus corpus analysis – a form of empirical investigation – deserves a larger role in building linguistic theory.

For theorists, this argument about the relationship between what is acceptable in grammatical form and what speakers and writers use in real texts (and therefore how great a contribution corpus linguistics can make to linguistic theory) is not likely to be resolved any time soon. At this stage in the development of corpus linguistics, the contribution it will make to linguistic theory is an open question. In fact, in the early years of corpus linguistics, few studies applied themselves to issues of linguistic theory. However, a noteworthy development is the international peer-reviewed journal Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory, which started publication in 2005.

For most teachers and students, the relationship between what is found in a corpus and what is grammatically acceptable is a much more immediate and practical issue than for linguistic theorists. As corpus techniques were gaining popularity for teaching grammar in the mid-1990s, Owen (1996) raised this issue in a now well-known paper that used the sentence ‘Many more experimental studies require to be done’ to demonstrate the difficulties with consulting a corpus for enhancing prescription (p. 222). He explained that most native speakers are likely to find the structure unacceptable, but an ESL student looking at the British National Corpus would find some similar sentences – e.g. explanations describing that ‘fruit trees require to be pruned’–and the student would likely believe that require + a passive to-infinitive clause is acceptable. Hunston (2002: 177) explains that the apparent conflict is resolved by considering the semantics of the lexicogrammatical association. Specifically, in the corpus, almost all the verbs occurring in the infinitive clause express a specific meaning, and the subjects are clearly the recipients of an action (e.g. trees are changed by the pruning). In Owen’s example, in contrast, the verb do has a very general meaning and the subject, many more experimental studies, is not actually acted upon (i.e. do a study does not mean that a specific action was done to a study but rather is a way to express the process of conducting research).

This analysis addresses the problem of the corpus appearing to have many occurrences of a structure most native speakers find unacceptable; in fact, when the lexico-grammatical associations are further examined, it does not. However, such an analysis requires quite sophisticated linguistic explanations and can be time-consuming – and so does not address the pedagogical problem of reconciling corpus data and grammaticality judgements. Rather, virtually all corpus researchers who address teaching issues agree that teachers’ intuition and prescriptive grammar rules have a role when students need judgements about acceptability. As Hunston puts it, ‘Distinguishing between what is said and what is accepted as standard may need the assistance of a teacher or a grammar book’ (Hunston 2002: 177; see further discussion of grammar teaching in Hughes, this volume).

The real contribution of corpus linguistics to grammar has not been to help make judgements about acceptability easier. Rather, it has been to complicate judgements of acceptability to make them reflect reality more accurately. As research in sociolinguistics has shown for many decades, acceptability varies with context. One clear sign of corpus linguistics’ impact on the field of grammar can be seen in the way that recent corpusbased grammar books of English handle standards and acceptability. Biber et al. (1999) have six and a half pages devoted to discussion of standard English, non-standard English and variation in them. Carter and McCarthy (2006: 5) cover four descriptions of acceptability that consider register and regional factors (in addition to an ‘unacceptable in all contexts’ category). Clearly, work in corpus linguistics is moving the field beyond the dichotomous view of grammatical structures as acceptable versus unacceptable and accurate versus inaccurate.

In a chapter of this size, a number of important areas are inevitably neglected. For the methods of corpus-based grammar studies, much more could be said especially about the role of statistics (see e.g. Oakes 1998) and the usefulness of grammatically annotated corpora (see chapters by Reppen and Lee, this volume). Among the topic areas that deserve far more coverage is the development of grammar over time, including both historical studies (e.g. Fitzmaurice 2003; Leech and Smith 2006) and studies of emergent forms (e.g. Barbieri’s 2005 study of new quotative forms such as be like, be all and go). Corpus studies are also beginning to make considerable contributions to our understanding of the grammar of specific varieties of English in the world (e.g. see de Klerk 2006 on Xhosa English) and to English used as a lingua franca (e.g. Seidlhofer 2001; Mollin 2006). In addition, corpus studies have addressed grammar in many languages other than English (e.g. see the collections edited by Johansson and Oksefjell 1998; Wilson et al. 2006). Despite its inability to do justice to all related topics, however, the chapter has sought to show that corpus linguistics has already had a profound effect on our understanding of grammar and is likely to continue to do so in the future.

Further reading

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S. and Finegan, E. (1999) Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Harlow, England: Pearson Education. (This covers frequency information, lexicogrammar patterns and comparisons of use in conversation, fiction writing, newspaper writing and academic prose for all major structures in English, as well as including chapters on fixed phrases, stance and conversation.)

Carter, R. and McCarthy, M. (2006) Cambridge Grammar of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (This emphasises more general spoken versus written language, but also includes many similar lexico-grammatical analyses, and covers some more functional categories of language – e.g. describing typical grammatical realisations of speech acts – and typical ESL difficulties.)

References

Azar, B. (2002) Understanding and Using English Grammar, third edition. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Barbieri, F. (2005) ‘Quotative Use in American English: A Corpus-based, Cross-register Comparison’, Journal of English Linguistic 33(3): 222–56.

Biber, D. (2004) ‘Historical Patterns for the Grammatical Marking of Stance: A Cross-register Comparison’, Journal of Historical Pragmatics 5(1): 107–35.

——(2006) University Language: A Corpus-based Study of Spoken and Written Registers. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Biber, D. and Conrad, S. (in press) Register Genre Style. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D., Conrad, S. and Reppen, R. (1998) Corpus Linguistics: Investigating Language Structure and Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S. and Finegan, E. (1999) Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Harlow, England: Pearson Education.

Biber, D., Conrad, S. and Cortes, V. (2004) ‘“Take a Look At …”: Lexical Bundles in University Teaching and Textbooks’, Applied Linguistics 25(3): 401–35.

Burges, J. (1996) ‘Hierarchical Influences on Language Use in Memos’, unpublished dissertation, Northern Arizona University.

Carter, R. and McCarthy, M. (2006) Cambridge Grammar of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Conrad, S. (1999) ‘The Importance of Corpus-based Research for Language Teachers’, System 27 (1): 1–18.

——(2000) ‘Will Corpus Linguistics Revolutionize Grammar Teaching in the 21st Century?’ TESOL Quarterly 34(3): 548–60.

——(2002) ‘Corpus Linguistic Approaches for Discourse Analysis’, Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 22 (Discourse and Dialog): 75–95.

Cook, V. (1994) ‘Universal Grammar and the Learning and Teaching of Second Languages’, in T. Odlin (ed.), Perspectives on Pedagogical Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 25–48.

de Klerk, V. (2006) Corpus Linguistics and World Englishes: An Analysis of Xhosa English. London: Continuum.

Fitzmaurice, S. (2003) ‘The Grammar of Stance in Early Eighteenth-century English Epistolary Language’, in P. Leistyna and C. Meyer (eds) Corpus Analysis: Language Structure and Language Use. Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 107–32.

Fortanet, I. (2004) ‘The Use of “We” in University Lectures: Reference and Function’, English for Specific Purposes 23(1): 45–66.

Frazier, S. (2003) ‘A Corpus Analysis of Would-clauses Without Adjacent If-clauses’, TESOL Quarterly 37(3): 443–66.

Hughes, R. and McCarthy, M. (1998) ‘From Sentence to Grammar: Discourse Grammar and English Language Teaching’, TESOL Quarterly 32(2): 263–87.

Hunston, S. (2002) Corpora in Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hunston, S. and Francis, G. (1999) Pattern Grammar: A Corpus-driven Approach to the Lexical Grammar of English. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Johansson, J. and Oksefjell, S. (eds) (1998) Corpora and Cross-linguistic Research: Theory, Method and Case Studies. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Kachru, Y. (2008) ‘Language Variation and Corpus Linguistics’, World Englishes 27(1): 1–8.

Kretzschmar, W., Anderson, J., Beal, J., Corrigan, K., Opas-Hänninen, L. and Plichta, B. (2006) ‘Collaboration on Corpora for Regional and Social Analysis’, Journal of English Linguistics 34(3): 172–205.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2002) ‘The Grammar of Choice’, in E. Hinkel and S. Fotos (eds) New Perspectives on Grammar Teaching in Second Language Classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, pp. 103–18.

Leech, G. and Smith, N. (2006) ‘Recent Grammatical Change in Written English 1961–92’,inA. Renouf and A. Kehoe (eds) The Changing Face of Corpus Linguistics. Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 185–204.

Louwerse, M., Crossley, S. and Jeuniauxa, P. (2008) ‘What If? Conditionals in Educational Registers’, Linguistics and Education 19(1): 56–69.

McCarthy, M. and Carter, R. (1995) ‘Spoken Grammar: What Is It and How Do We Teach It?’ ELT Journal 49(3): 207–18.

——(2001) ‘Size Isn’t Everything: Spoken English, Corpus, and the Classroom’, TESOL Quarterly 35(2): 337–40.

——(2002) ‘Ten Criteria for a Spoken Grammar’, in E. Hinkel and S. Fotos (eds) New Perspectives on Grammar Teaching in Second Language Classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 51–75.

Mauranen, A. (2003a), ‘“But Here’s a Flawed Argument”: Socialisation into and through Metadiscourse’, in P. Leistyna and C. Meyer (eds) Corpus Analysis: Language Structure and Language Use. New York: Rodopi, pp. 19–34.

——(2003b) ‘“A Good Question”. Expressing Evaluation in Academic Speech’, in G. Cortese and P. Riley (eds) Domain-Specific English: Textual Practices across Communities and Classrooms. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 115–40.

Meyer, C. (2002) English Corpus Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Meyer, C. and Tao, H. (2005) ‘Response to Newmeyer’s “Grammar Is Grammar and Usage is Usage”’, Language 81(1): 226–8.

Mollin, S. (2006) ‘English as a Lingua Franca: A New Variety in the New Expanding Circle?’ Nordic Journal of English Studies 5(2): 41–57.

Nelson, G. (2006) ‘The Core and Periphery of World English: A Corpus-based Exploration’, World Englishes 25(1): 115–29.

Newmeyer, F. (2003) ‘Grammar is Grammar and Usage is Usage’, Language 79(4): 682–707.

Oakes, M. (1998) Statistics for Corpus Linguistics. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

O’Keeffe, A., McCarthy, M. and Carter, R. (2007) From Corpus to Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Owen, C. (1996) ‘Does a Corpus Require to Be Consulted?’ ELT Journal 50(3): 219–24.

Sampson, G. (2007) ‘Grammar without Grammaticality’, Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory 3(1): 1–32.

Seidlhofer, B. (2001) ‘Closing a Conceptual Gap: The Case for a Description of English as a Lingua Franca’, International Journal of Applied Linguistics 11(1): 133–58.

Sinclair, J. (1991) Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stenström, A.-B., Andersen, G. and Hasund, I. (2002) Trends in Teenage Talk: Corpus Compilation, Analysis and Findings. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Wilson, A., Archer, D. and Rayson, P. (eds) (2006) Corpus Linguistics around the World. Amsterdam: Rodopi.