30

Corpus-informed course book design

Jeanne McCarten

1. Introduction

A course book is a carefully sequenced, graded set of teaching materials whose aim is to improve the language knowledge and performance of its users, taking them from one level to another. It is a hugely complex, lengthy and expensive undertaking for both writer and publisher in terms of investment in time, research and production. As such, there is great pressure on all concerned for it to be successful to return that investment. Therefore it must tread a fine balance between offering something new –‘unique selling points’–while remaining user-friendly, familiar and even ‘safe’. Typically, course books present and practise grammar, vocabulary, language functions, pronunciation and ‘the four skills’: reading, writing, listening and speaking, packaged together in thematic units. General course materials usually aim to give equal weight to the various language areas, so their multi-stranded syllabi provide an integrated course balancing accuracy and fluency. Course books may teach ‘general’ language or more specialised types such as business or academic language, or examination preparation. Corpora have informed English dictionaries and grammar reference books since the publication of the Collins COBUILD English Language Dictionary in 1987 and the Collins COBUILD English Grammar in 1990. Curiously, with the exception of The COBUILD English Course (Willis and Willis 1987–8), course books have generally been slow to exploit corpora as a resource, and several researchers including Biber et al. (1998), Tognini Bonelli (2001), Gilmore (2004), Cheng and Warren (2007) and Cullen and Kuo (2007) have pointed to disparities between language descriptions and models in course books and actual language use as evidenced in a corpus.

2. What kind of corpus is needed to write a course book?

Corpora come in different shapes and sizes so it makes sense to use corpora whose content is broadly similar in nature to the language variety, functions and contexts that the end users of the material aspire to learn. In choosing a corpus the following considerations may be useful.

Variety

In the case of English Language Teaching (ELT), most internationally marketed course books fall into two main categories of ‘American English’ and ‘British English’ in that the formal language presentations tend to be in one or other main variety. Course-book writers therefore need access to a corpus of the chosen variety to ensure that their syllabus and language models accurately reflect usage in the corpus. A corpus is useful in adapting a course book from one variety to another, a common practice in some international publishing houses. While some differences between North American and British English are well known (e.g. elevator vs lift and gotten vs got), a corpus can reveal more subtle differences in frequency and use between the two varieties. For example, the question form have you got … ? is over twenty-five times more frequent in spoken British English than in North American English, which favours do you have … ?, and so merits an earlier inclusion in an elementary British English course book than it might in a North American one.

Genre

Some course books are described as ‘general’, ‘four skills’ courses and others are more specialised, such as business or academic courses. Again, it makes sense for the writer to use a corpus that contains the type of language that is the target for the learner. Corpora of different genres will give different results in terms of their most frequent items of vocabulary, grammar or patterns of use. So if the course book aims to teach conversation skills, a corpus of written texts from newspapers and novels will not give the writer much information about the interactive language of conversation. Equally, a spoken corpus is unlikely to help the writer of an academic writing course identify the common vocabulary and structures which learners need to master. For example, the word nice is in the top fifteen words in conversation, and is therefore a useful word to include in a general or conversation course. In contrast, in academic written English nice is rare, occurring mainly in quotations of speech from literature or interviews, so may be less useful. Some words may have a similar frequency in conversation and academic written English, but have different meanings or uses. In academic English see is mostly used to refer the reader to other books and articles, as in see Bloggs 2007. In conversation, see has various uses, including leave-taking (see you later), showing understanding (I see), and in you see,to impart what the speaker feels is new information for the listener (You see, he travels first class). See Carter and McCarthy (2006: 109b).

Age

Many English corpora such as the British National Corpus (BNC), or the American National Corpus (ANC) contain mostly adult speakers and writers. If the trend towards corpus-informed materials continues, it is hoped that writers of materials for younger learners will be able to draw on corpora of young people’s language, in order to present age-appropriate models. A comparison of the Bergen Corpus of London Teenager Language (COLT) (see Andersen and Stenström 1996) with the Cambridge and Nottingham Corpus of Discourse in English (CANCODE) (see McCarthy 1998) reveals that certain stance markers (to be honest, in fact, I suppose) and discourse markers, especially the more idiomatic types (on the other hand, at the end of the day) occur with greater frequency in the adult corpus. Such comparisons can identify features of language use which are typical and appropriate to a target age group.

Learner and non-native-speaker data

Major publishers, examination bodies, research groups and individual researchers collect corpora of learner data. Such corpora, especially those which have errors coded and classified, contain invaluable information about the language used (or not used) by learners, and common mistakes made. Well-designed corpora can be searched by level or first language background, enabling the writer to find, for example, the most common errors made by lower-intermediate Italian learners, which can be useful for courses aimed at specific markets.

In the case of English, a major debate is the status of the native speaker. Some, including Cook (1999), Widdowson (2000), Seidlhofer (2004, 2005), Jenkins (2006), question whether learners should be judged against the models and norms extracted from native-speaker corpora, and advocate instead those of English as a Lingua Franca (ELF), or World Englishes (Kirkpatrick 2007). They argue that realistic models for learners are to be found in non-native-speaker corpora, such as the Vienna–Oxford International Corpus of English (VOICE) at the University of Vienna (Seidlhofer 2004). Prodromou (2003) proposes the notion of the ‘successful user of English’ as a focus, rather than the narrowly defined native speaker. Others argue that learners may prefer to approximate native-speaker norms without losing what Timmis (2005) calls their ‘cultural integrity’ (see also Carter and McCarthy 1996; Timmis 2002).

One important use of learner data is the English Profile project. This aims to establish empirically validated reference-level descriptions for English for the six levels of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). It is based on the Cambridge Learner Corpus of Cambridge ESOL written examination scripts and spoken learner data gathered internationally from classrooms and other settings. This is set to inform course materials for many years.

Size of corpus

McCarthy and Carter (2001) assert that ‘size isn’t everything’, arguing that small, carefully constructed corpora can yield fruitful research results. For the course-book writer, however, the bigger the corpus the better, not just for linguistic reasons (e.g. frequency of lexical and grammatical items) but also for coverage of a wide range of topics and situations. A typical four-level course-book series might address between fifty and eighty topics and in a larger corpus there is a greater likelihood of finding more topics discussed.

3. What areas of the course book can a corpus inform?

A corpus can assist a course-book writer in several ways, including constructing a graded lexico-grammatical syllabus and finding appropriate texts and realistic settings for the presentation and practice of target language.

Information about the language syllabus

First and foremost a corpus provides information about different aspects of the language, which is normally the basis of the syllabus (see Walsh, this volume). Tognini Bonelli (2001) advocates the ‘corpus-driven’ approach, where the corpus provides the basis of the description of language usage without recourse to previously held beliefs, above the ‘corpus-based’ approach, where the corpus provides examples for pre-existing rules. As successful course books generally fit within an established body of knowledge in terms of language description, the course-book writer may be more inclined to the latter (see Gavioli and Aston 2001). McCarthy (1998) advocates a third approach, ‘corpus-informed’, which borrows from both approaches and is suggested as an alternative possibility.

Vocabulary syllabus

Corpus software can easily generate lists of the most frequent words (whether lemmatised or as individual word-forms) in a given corpus. These enable the writer to establish the common core vocabulary that learners are likely to need as a priority as opposed to a more advanced vocabulary, which can be taught later (see O’Keeffe et al. 2007: Ch. 2). Frequency lists which ‘band’ vocabulary into the most frequent 1,000 words, 2,000 words, etc., can be the basis for organising vocabulary for different levels of a course book. The syllabus of The Cobuild English Course (Willis and Willis 1987–8) with its lexical approach was determined by word frequency. The most frequent 700 words with their common patterns were taught in Level 1, the next 800 in Level 2, and so on (see Willis 1990). Frequency also helps the writer to prioritise which members of large lexical sets – for example colours, foods, clothes – to teach first, or see which of two or three synonyms is more frequent (e.g. sofa or couch; eat breakfast or have breakfast) and identify the most frequent collocates of delexical verbs such as make and do. For writers of more specialist courses such as English for Academic Purposes courses, the Academic Wordlist created by Averil Coxhead (Coxhead 2000) from a corpus of 3,500,000 academic texts provides an invaluable resource of lists of 570 word families (excluding the top 2,000 most frequent words in English) from which to devise a vocabulary syllabus (see Coxhead, this volume). Similarly, the Cambridge Learner Corpus of written scripts from Cambridge ESOL examinations provides writers of examination courses with information about typical errors made by candidates in those examinations, around which a syllabus area can be built. See Capel and Sharp (2008) as an example.

While frequency is a useful guide, it may not always be the only criterion in building a syllabus. Members of some vocabulary sets, such as colours, have different frequencies (red being six times more frequent than orange in spoken North American English), so may occur in different frequency ‘bands’. Days of the week provide the best example of why strict banding might not be the only criterion, as only four of the seven occur in the top 1,000 words in conversation, and yet it seems common sense to teach the seven days together. Many corpora are collected in native-speaker environments: homes, work places, social gatherings and service encounters; they contain the everyday interactions of native speakers in their own professional and social settings. Non-native speakers may operate in different settings, interacting either as visitor or host either in their own or a different language environment. Their communication needs are not necessarily always the same as native speakers interacting with native speakers. Furthermore, few corpora include data from classrooms, which have their own specialist vocabulary that would not occur as frequently in general corpora: for example, classroom objects (board, highlighter pen), processes and instructions (underline, fill in the gaps) and linguistic metalanguage (noun, verb, etc.). Finally, some of the most frequent words in a native-speaker corpus may present a major learning challenge to elementary learners because of their associated patterns. For example, supposed and already are both in the first 500 words in conversation, but in order to use these, learners may need to learn grammatical structures or meanings which are not usually taught or which are difficult to explain at early elementary level. So the writer has to make judgements about which items from the computer-generated lists to include and in what order, balancing what is frequent with what is useful and what is easily taught and learned.

Grammar syllabus

In general, corpus software has not been able to automatically generate lists of the most common grammatical structures in the same way that it can list the most frequent vocabulary. To get a sense of grammatical frequency, one can manually count structures in corpus samples. Not surprisingly, perhaps, conversation contains a high proportion of simple present and past, a lower frequency of continuous verb forms, and complex verb phrases consisting of modal verbs with perfect aspect are less frequent still. Biber et al. (1999) is an invaluable resource of such genre-specific grammatical information. Manual counting is also required, for example, to classify the meanings of common modal verbs like can and must, and again this research can inform the writer’s choice of which meaning(s) to present first.

As with vocabulary, frequency may not be the only criterion for deciding what items to teach and in what order. There is a strong expectation in some parts of the Englishteaching world of the order in which grammatical structures should be taught. For example, many teachers believe the present continuous forms should be taught before the simple past form, even though the present continuous is far less frequent in a general spoken corpus. This may be because it builds on the present of be – traditionally the first grammatical structure taught – or because it is useful in class in describing pictures and actions, as part of vocabulary building. A course book which adheres to linguistic principles but ignores teacher expectation may not succeed.

Lexico-grammatical patterns

Having established a core lexical and grammatical inventory, the writer can then look to a corpus for more information about usage. Basic corpus software such as concordancing applications can clearly reveal information about not just vocabulary patterns, such as collocations, but also patterns that grammar and vocabulary form together. One example is verb complementation, which is often tested at intermediate levels, especially of verbs such as mind, suggest and recommend. What the corpus shows is a far less complex use of these verbs than is suggested by the amount of testing they receive. For example, with the verb mind in requests and permission-seeking speech acts with do you and would you, four basic patterns seem possible:

Requests

1 Do you mind + … ing: e.g. Do you mind helping me for a second?

2 Would you mind + … ing: e.g. Would you mind helping me for a second?

Asking for permission

3 Do you mind + if: e.g. Do you mind if I leave early today?

4 Would you mind + if: e.g. Would you mind if I leave (or left) early today?

(In addition there is the possibility of adding an object, e.g. Would you mind me asking you something? and the use of a possessive: Would you mind my asking you something?)

However, in a corpus of North American English conversation only two patterns emerge as overwhelmingly more frequent than any others, as shown in the concordance lines below, which are a representative selection from the corpus.

(Cambridge International Corpus, North American English Conversation)

Do you mind is mostly used in the expression Do you mind if I … to ask permission to do something and Would you mind is mostly used as Would you mind + … ing to ask other people to do something. In some cases the phrases are used with no complement. The more complex patterns with an object (Would you mind me asking … and Do you mind us taping … ) are also much less frequent. This kind of information can help the writer determine what is core common usage and what is more advanced. Similarly, in British English the structure suggest + object + base form as in I suggest you read that article accounts for only about 5 per cent of uses of the word suggest in both spoken and written English, yet this structure has often been tested in English examinations as if it were frequent. The course-book writer may occasionally, therefore, have to ‘ignore’ what the corpus reveals in order to cover what is in the testing syllabus.

Discourse management

As well as providing lists of single words and sets of collocations, corpus software can also generate lists of items that contain more than one word, normally between two- and seven-word items, variously called ‘multi-word units’, ‘clusters’, ‘chunks’, ‘lexical phrases’ or ‘lexical bundles’ (see Greaves and Warren, this volume; Nattinger and DeCarrico 1992; Biber et al. 1999; O’Keeffe et al. 2007). Some of the items on these lists are ‘fragments’ or sequences of words that do not have a meaning as expressions in their own right, such as in the, and I and of the. These are frames for extended structures, for example in the beginning, etc. (see Greaves and Warren, this volume). However, there are a large number of items which are expressions with their own intrinsic meaning, as in Table 30.1.

Many of these items are much more frequent than the everyday, basic single words that are normally taught at an elementary level. Chunks such as I mean, I don’t know and or something are more frequent than the single words six, black and woman, which are undeniably part of a general elementary course syllabus. With such frequency, these multi-word items are worthy of inclusion in the syllabus whether as vocabulary or as part of conversation skills (see O’Keeffe et al. 2007).

Such multi-word items can be classified into broad functional categories. For example, in the small selection of items from conversation above there are vague category markers (and all that, or something like that, and things like that) and hedging and stance expressions (a little bit, I guess, as a matter of fact), which are characteristic of casual conversation. Many of the four-word chunks in conversation include the phrase I don’t know (+ if, what, how, etc.) which often functions as an ‘involving phrase’, to acknowledge that the listener may have experience or knowledge of a topic before the speaker gives information or an opinion, as in I don’t know if you’ve seen that movie, been to that city, etc. (see Carter and McCarthy 2006: Sections 109 and 505c). O’Keeffe et al. (2007) refer to such language as ‘relational’ as opposed to ‘transactional’ as it is concerned with establishing and managing relationships with interlocutors. Together with single-word discourse markers (well, anyway, so, now) this vocabulary may be said to constitute a vocabulary of conversation, i.e. a vocabulary which characterises conversation, as distinct from more general vocabulary found in conversation (McCarten 2007). In McCarthy et al. (2005a, 2005b, 2006a, 2006b) this relational language and associated discourse management strategies are classified into four broad macro functions, which form the basis of a conversation management syllabus. These are:

• managing your own talk – discourse markers, which enable speakers to manage their own turns in a conversation (I mean, the thing is, on the other hand);

• taking account of the listener – such as the vague category markers and involving phrases above, hedging and stance expressions (just a little bit, kind of; to be honest with you, from my point of view);

• ‘listenership’ (see McCarthy 2002) – response tokens and expressions to acknowledge the contribution of another speaker (that’s great, I know what you mean);

• managing the conversation as a whole (speaking of, going back to; well anyway to end a conversation).

While writing shares some of the relational language of conversation, including more formal vague language (and so on, etc.) and discourse marking (in conclusion, on the other hand), chunks in writing are more frequently associated with orienting the reader in space and time (at the end of the, for the first time) and expressing connections (in terms of, as a result of) (see O’Keeffe et al. 2007). These chunks perform important strategies and thus merit inclusion in academic writing courses alongside the items on the Academic Word List.

Contexts of use

Close reading of a corpus can also confirm the frequency of structures in certain contexts. One example is the use of the past tense – especially of the verbs have, need and want – as a way of asking questions indirectly, as in the examples below:

Example 1 (At a US department store perfumery counter)

Clerk: So did you want to purchase anything or you just wanted to try ’em?

Customer: We we wanted to try.

How much are those?

(Cambridge International Corpus, North American English Conversation)

Example 2 (At a large informal dinner party)

Speaker 1: Can I have a fork? I’m just gonna keep asking you for things until I get everything I need.

Speaker 2: What did you want?

Speaker 1: A fork please.

Anything else up there look good?

(Cambridge International Corpus, North American English Conversation)

Another example is the use of the present tense in spoken narratives about the past to highlight events, people or things (Schiffrin 1981). This is common in informal narratives, as in the example below where the speaker switches from the past tense to the present once the context is set:

Example 3 (Informal narrative to a friend)

I was sitting out in the yard and my sister made me eat a mud pie. You know?

Here she is eighteen months older than me and I’m sitting out in the yard and she she has all these mud pies

(Cambridge International Corpus, North American English Conversation)

By observing such uses, the writer can decide whether to augment the traditional grammar syllabus with these ‘relational’ uses of grammar. The decision may be influenced by space and time factors, teacher or publisher expectation and acceptance and, as noted earlier, the testing syllabus.

Models for presentation and practice

By observing in a corpus how people choose their language according to the situation they are in and the people they are with, the course-book writer can select appropriate, realistic and typical contexts in which to present and practise grammatical structures or vocabulary. An example from grammar is the use of must in conversation, which is used overwhelmingly to express speculation rather than obligation and is often found in responses and reactions to what the speaker hears or sees.

Example 4 (Woman talking about business travel to a stranger)

Speaker 1: They put me up in hotels and things.

Speaker 2: Oh that’s nice. That’s always fun.

Speaker 1: It’s not too bad.

Speaker 2: Yeah. It must be tough though. Moving back and forth a lot.

(Cambridge International Corpus, North American English conversation)

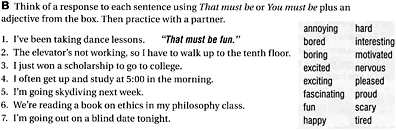

This can be practised in exercises such as the one in Figure 30.1.

Figure 30.1 Extract from Touchstone Student Book 3

Source: McCarthy, McCarten and Sandiford, 2006a: 112.

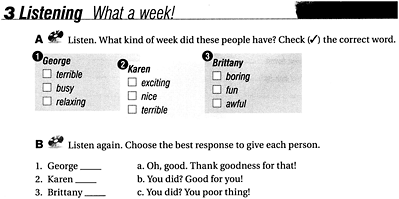

Similarly, listenership activities can be included alongside listening comprehension activities using simple and familiar exercise formats. In the activity in Figure 30.2, Part A

Figure 30.2 Extract from Touchstone Student Book 1

Source: McCarthy, McCarten and Sandiford, 2005a: 103.

is a more traditional listening comprehension question, in which students listen for a main idea (what kind of week the speaker has had). Part B develops the listenership skill and asks students to choose an appropriate response for each speaker. This can be developed by asking students for further ideas for responses.

4. How can corpus data be used in a course book?

Information about the language

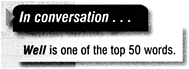

Corpora and the software to analyse them are unfamiliar to many course-book users and are perhaps seen as for specialists. Course books have generally borrowed little from the explicit use of corpus data seen in data-driven learning (DDL) (see chapters by Gilquin and Granger, Chambers and Sripicharn, this volume). However, information derived from corpus research can be used ‘invisibly’ in materials. The writer can include the most frequent structures, vocabulary, collocations and patterns in a course book without telling users where they came from or why they are included. However, it can be useful to let teachers and learners know more about the language presented. Information about frequency can provide a justification and motivation for learning something and help users see the value of learning high-frequency expressions such as I mean, I guess, etc. McCarthy et al. (2005a, 2005b, 2006a, 2006b) provide ‘corpus factoids’ about frequency and use such as the ones in Figure 30.3 and 30.4.

Figure 30.3 Extract from Touchstone Student Book 1

Source: McCarthy, McCarten and Sandiford, 2005a: 39.

Figure 30.4 Extract from Touchstone Student Book 4

Source: McCarthy, McCarten and Sandiford, 2006b: 45.

Using corpus texts for presentation

Authentic written texts, i.e. texts from real-world sources such as newspapers, advertising and novels, have long been used in course materials, more so than spoken texts, which are often invented. A corpus of real conversations can provide excellent raw material for course-book presentations. However, unedited corpus conversations can be problematic for several reasons.

• They can be of limited interest to others (teaching material has to engage students’ interest above all) and have little real-world ‘content’ to build on in follow-up activities. Few contain the humour that some teachers and learners enjoy.

• It may be difficult for an outside reader to understand the context and purpose of the conversation (see Mishan 2004).

• Conversations may contain references to people, places and things that are only known to the original speakers and may have no discernible start or end.

• They may contain taboo words or topics which are unsuitable for teaching materials.

• Some speakers are not very ‘fluent’ and their speech contains a lot of repetition and rephrasing, hesitation, false starts and digression. Conversations with these features can be difficult to read – they were not meant to be read, after all – or listen to.

• People often speak at the same time, which is difficult to hear on audio recordings and reproduce in print, especially in multi-party conversations.

• Real conversations may include vocabulary and structures that distract from the main teaching goal, being too advanced or arcane or requiring lengthy explanation.

• Some teachers may feel ‘unprepared’ to teach features of spoken grammar which are not in the popular training literature or practice resources.

• Dialectal and informal usage may be considered incorrect by some teachers (e.g. non-standard verb forms such as would have went, less + plural count noun, etc.) Some teachers also disapprove of spoken discourse markers and relational language such as you know, like, well and I mean, and hesitation markers um, uh. In an informal survey of seventy ESL teachers from different sectors in Illinois, USA, McCarthy and McCarten (2002) found teachers more disapproving of these phrases than the grammatically debatable usage of there’s + plural noun.

• Normally obligatory words are often ‘omitted’ in speaking (ellipsis), especially when there is a lot of shared context. For example, one colleague might say to another You having lunch? or Having lunch? or simply Lunch? instead of Are you having lunch? Some teachers may find it problematic to use such models without a finite verb, subject or auxiliary verb, especially when it appears the grammar ‘rules’ are broken.

• Real conversations rarely contain the number or variety of examples of a target structure, such as first, second and third persons, singular and plural, affirmative and negative forms.

• Conversations are often too long to reproduce on the page. Elementary course materials often have publisher-imposed limits of fifty–sixty words per presentation.

• Conversations where one speaker has much more to say than the other can be difficult to practise in pairs.

These are many ways in which real conversations differ from those in traditional course books (see Gilmore 2004), but it is possible to replicate natural-sounding conversations by applying some general principles:

• Keep turns generally short, unless someone is telling a story. Even then, backchannelling and non-minimal responses can be included for the listener (McCarthy 2002, 2003).

• Ensure that speakers interact, for example by reacting to the previous speaker, before adding a new contribution to the conversation (see Tao 2003).

• Conversation is usually not very lexically dense and information is not so tightly packed as is often the case in course-book conversations, so ensure a balance of transactional and relational language with an appropriate lexical density (Ure 1971; Stubbs 1986).

• Build in some repetition, rephrasing, fragmented sentences and features of real speech, in ways that do not interfere with comprehension.

• Adhere to politeness norms, in the sense described by Brown and Levinson (1987). Course books occasionally contain discussions where speakers are unrealistically confrontational and face-threatening to each other. While there may be cultural issues to consider here – and course books should not impose English-speakers’ cultural norms – it is worth noting that native speakers of English are more likely to prefer indirect strategies in discussion, for example, I disagree with that rather than I disagree with you. See also Tao (2007). This is not to deny learners ‘the right to be impolite’ (Mugford 2008), which is a separate question.

One issue in representing conversation in course books is punctuation of, for example, pauses, incomplete words, ellipsis and false starts. More problematic is that there is no accepted orthographic form for common articulations of some structures (e.g. wouldn’t’ve for wouldn’t have; what’s he do for what does he do?). Also transcription conventions for common features of conversation, such as overlapping or latched turns, are not widely known. Here simplifications may have to be made.

Exploiting authentic spoken data in course material for listening comprehension is well established. Swan and Walter (1984, 1990) were among the first to include what they called ‘“untidy” natural language’ as listening practice. As interest in teaching the spoken language grows, materials will no doubt focus more explicitly on features of conversation management and develop a classroom-friendly metalanguage and methodologies for doing so. Concepts such as ‘hedging’, ‘sentence frames’, ‘reciprocation’ and ‘pre-closing’ can be translated into more transparent terms for the classroom, for example, ‘softening what you say’, ‘introducing what you say’, ‘keeping the conversation going’ and ‘ending the conversation’. As some of these concepts are still new in materials, it is important to find ways to present and practise these features using non-threatening and familiar exercise types. Teaching such features may best be done with techniques that ask learners to ‘notice’ (see Schmidt 1990), find examples of a feature which has been exemplified or find ways in which speakers perform particular functions.

5. The future of corpus-informed course books

A more corpus-informed future?

It is hoped that more course materials will be corpus-informed and that writers will have greater access to corpora, or else to published output such as frequency lists based on major corpora (Leech et al. 2001) and corpus research findings. Specialised corpora such as the language of business (see McCarthy and Handford 2004), tourism and other vocational settings will no doubt inform materials aimed at students of these types of language.

Improved voice-to-text software for transcription will make the collecting of larger spoken corpora easier and cheaper. Developments in analytical software, such as refined automatic tagging and parsing of corpora and more sensitive collocational tools, should enable researchers to gain greater depth of language knowledge to pass on to learners in materials. Areas for further research will include the frequency and distribution of grammar structures or vocabulary in different text types and extended lexico-grammatical patterns.

Print versus electronic delivery

Until recently, courses have been delivered primarily in printed book form for use in classrooms by groups of students with a teacher. With the increasing sophistication of computer software, faster internet speeds and e-books, it is likely that more educational content will be delivered on the internet in virtual learning environments which users can access individually in addition to, or independently of, the classroom. Course materials will therefore need to adapt to online learning environments, in more flexible learning packages delivered electronically as well as in book form. The electronic medium can offer teachers and learners easier access to corpora so DDL approaches may enter more mainstream materials. As concordancing software becomes more user-friendly and its aims more transparent to a wider audience, it is possible to envisage concordancers being part of blended learning packages, possibly as complementary to dictionary or grammar reference material. Corpora can be specially compiled to reflect the course content and aims, or can even be graded to help lower-level students access the material, as proposed by Allan (2009).

Multi-modal corpora are now being developed (see Ackerley and Coccetta 2007; Adolphs and Carter 2007; Knight and Adolphs 2007; Carter and Adolphs 2008) in which audio and video are captured alongside the transcribed text. From a research point of view, this should enhance language description, adding information about prosodic features, gesture or body language to our knowledge of grammar, vocabulary and pragmatics. For learners and teachers, multi-modal corpora may be a more user-friendly tool for classroom use.

In summary, there is bright future for corpus-informed course materials. Bringing into the classroom the language of the world outside gives learners greater opportunities to increase their understanding of natural language and the choice to use it. And this is surely the ultimate aim of all of us who are engaged in language teaching.

Further reading

Carter, R. and Adolphs, S. (2008) ‘Linking the Verbal and Visual: New Directions for Corpus Linguistics’, Language and Computers 64: 275–91. (A fascinating look into the future of multi-modal corpus research methodology and findings.)

Cullen, R. and Kuo, I.-C. (2007) ‘Spoken Grammar and ELT Course Materials: A Missing Link?’ TESOL Quarterly 41(2): 361–86. (An interesting analysis of how spoken grammar is represented in course books.)

Gilmore, A. (2004) ‘A Comparison of Textbook and Authentic Interactions’, ELT Journal 58(4): 363–71. (A good overview of differences between real conversations and those in course books.)

O’Keeffe, A., McCarthy, M. J., and Carter, R. A. (2007) From Corpus to Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (An excellent introduction to corpus research and its practical pedagogical applications.)

References

Ackerley, K. and Coccetta, F. (2007) ‘Enriching Language Learning through a Multimedia Corpus’, ReCALL 19: 351–70.

Adolphs, S. and Carter, R. (2007) ‘Beyond the Word: New Challenges in Analysing Corpora of Spoken English’, European Journal of English Studies 11(2): 133–46.

Allan, R. (2009) ‘Can a graded reader corpus provide “authentic” input?’, ELT Journal 63(1): 23–32.

Andersen, G. and Stenström, A.-B. (1996) ‘COLT: A Progress Report’, ICAME Journal 20: 133–6.

Biber, D., Conrad, S. and Reppen, R. (1998) Corpus Linguistics: Investigating Language Structure and Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D., Johannson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S. and Finnegan, E. (1999) Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. London: Longman.

Brown, P. and Levinson, S. (1987) Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Capel, A. and Sharp, W. (2008) Objective First Certificate, Student’s Book, second edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carter, R. and Adolphs, S. (2008) ‘Linking the Verbal and Visual: New Directions for Corpus Linguistics’, Language and Computers 64: 275–91.

Carter, R. and McCarthy, M. J. (1996) ‘Correspondence’, ELT Journal, 50: 369–71.

——(2006) Cambridge Grammar of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Cheng, W. and Warren, M. (2007) ‘Checking Understandings: Comparing Textbooks and a Corpus of Spoken English in Hong Kong’, Language Awareness 16(3): 190–207.

COBUILD (1987) Collins COBUILD English Language Dictionary. London: Collins.

——(1990) Collins COBUILD English Grammar. London: Collins.

Cook, V. (1999) ‘Going Beyond the Native Speaker in Language Teaching’, TESOL Quarterly 33(2): 185–209.

Coxhead, A. (2000) ‘A New Academic Word List’, TESOL Quarterly 34(2): 213–38. The Academic Wordlist can be found online at http://language.massey.ac.nz/staff/awl/ (accessed August 2008).

Cullen, R. and Kuo, I.-C. (2007) ‘Spoken Grammar and ELT Course Materials: A Missing Link?’ TESOL Quarterly 41(2): 361–86.

English Profile, www.englishprofile.org/

Gavioli, L. and Aston, G. (2001) ‘Enriching Reality: Language Corpora in Language Pedagogy’, ELT Journal 55(3): 238–46.

Gilmore, A. (2004) ‘A Comparison of Textbook and Authentic Interactions’, ELT Journal 58(4): 363–71.

Jenkins, J. (2006) ‘Current Perspectives on Teaching World Englishes and English as a Lingua Franca’, Tesol Quarterly 40(1): 157–81.

Kirkpatrick, A. (2007) World Englishes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Knight, D. and Adolphs, S. (2007) ‘Multi-modal Corpus Pragmatics: The Case of Active Listenership’, www.mrl.nott.ac.uk/~axc/DReSS_Outputs/Corpus_&_Pragmatics_2007.pdf (accessed August 2008).

Leech, G., Rayson, P. and Wilson, A. (2001) Word Frequencies in Written and Spoken English: Based on the British National Corpus. Harlow: Longman.

McCarten, J. (2007) Teaching Vocabulary – Lessons from the Corpus, Lessons for the Classroom. New York: Cambridge University Press Marketing Department.

McCarthy, M. J. (1998) Spoken Language and Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——(2002) ‘Good Listenership Made Plain: British and American Non-minimal Response Tokens in Everyday Conversation’, in R. Reppen, S. Fitzmaurice and D. Biber (eds) Using Corpora to Explore Linguistic Variation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 49–71.

——(2003) ‘Talking Back: “Small” Interactional Response Tokens in Everyday Conversation’,inJ. Coupland (ed.) ‘Small Talk’, special issue of Research on Language and Social Interaction 36(1): 33–63.

McCarthy, M.J. and Carter, R. (2001) ‘Size Isn’t Everything: Spoken English, Corpus, and the Classroom’, TESOL Quarterly 35(2): 337–40.

McCarthy, M. J. and Handford, M. (2004) ‘“Invisible to Us”: A Preliminary Corpus-based Study of Spoken Business English’, in U. Connor and T. Upton (eds) Discourse in the Professions. Perspectives from Corpus Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 167–201.

McCarthy, M. J. and McCarten, J. (2002) Unpublished study of seventy Illinois teachers’ reactions to conversation extracts in classroom materials.

McCarthy, M. J., McCarten, J. and Sandiford, H. (2005a) Touchstone Student’s Book 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——(2005b) Touchstone Student’s Book 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——(2006a) Touchstone Student’s Book 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——(2006b) Touchstone Student’s Book 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mishan, F. (2004) ‘Authenticating Corpora for Language Learning: A Problem and its Resolution’, ELT Journal 58(3): 219–27.

Mugford, G. (2008) ‘How Rude! Teaching Impoliteness in the Second-language Classroom’, ELT Journal 62(4): 375–84.

Nattinger, J. and DeCarrico, J. (1992) Lexical Phrases and Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Keeffe, A., McCarthy, M. J. and Carter, R. A. (2007) From Corpus to Classroom: Language Use and Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Prodromou, L. (2003) ‘In Search of the Successful User of English’, Modern English Teacher 12(2): 5–14.

Schiffrin, D. (1981) ‘Tense Variation in Narrative’, Language 57(1): 45–62.

Schmidt, R. (1990) ‘The Role of Consciousness in Second Language Learning’, Applied Linguistics 11: 129–58.

Seidlhofer, B. (2004) ‘Research Perspectives on Teaching English as a Lingua Franca’, Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 24: 209–39, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——(2005) ‘English as a Lingua Franca’, ELT Journal 59(4): 339–41.

Sinclair, J. (ed.) (1987) COBUILD English Language Dictionary. Glasgow: Collins.

Stubbs, M. (1986) ‘Lexical Density: A Computational Technique and Some Findings’,inR.M. Coulthard (ed.) Talking About Text. Birmingham: English Language Research, pp. 27–42.

Swan, M. and Walter, C. (1984) The Cambridge English Course Teacher’s Book 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

——(1990) The New Cambridge English Course Teacher’s Book 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tao, H. (2003) ‘Turn Initiators in Spoken English: A Corpus-based Approach to Interaction and Grammar’, in P. Leistyna and C. F. Meyer (eds) Language and Computers, Corpus Analysis: Language Structure and Language Use. Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 187–207.

——(2007) ‘A Corpus-based Investigation of Absolutely and Related Phenomena in Spoken American English’, Journal of English Linguistics 35(1): 5–29.

Timmis, I. (2002) ‘Native-speaker Norms and International English: A Classroom View’, ELT Journal 56(3): 240–9.

——(2005) ‘Towards a Framework for Teaching Spoken Grammar’, ELT Journal 59 (2): 117–25.

Tognini Bonelli, E. (2001) Corpus Linguistics at Work. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Ure, J. (1971) ‘Lexical Density and Register Differentiation’, in G. E. Perren and J. L. M. Trim (eds) Applications of Linguistics: Selected Papers of the Second International Congress of Applied Linguistics, Cambridge, 1969. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 443–52.

Widdowson, H. G. (2000) ‘On the Limitations of Linguistics Applied’, Applied Linguistics 21(1): 3–25.

Willis, D. (1990) The Lexical Syllabus, A New Approach to Language Teaching. Glasgow: Collins.

Willis, D. and Willis, J. (1987–8) The Cobuild English Course. Glasgow: Collins.