36

Using corpora in translation

Natalie Kübler and Guy Aston

1. Translating: purposes and processes

While recent years have seen considerable corpus-based research in the field of translation studies, aiming to identify the peculiar characteristics of translated texts qua products (Baker 1999; Olohan 2004; Mauranen 2007), much less has been done to study translating qua process, and to examine the potential roles of corpora in that process – and, in consequence, in the teaching and learning of translation skills. In this chapter we examine applications of corpora in the practice and pedagogy of translation. Our concern here is with pragmatic translation, where ‘“pragmatic” denotes the reader’s or readership’s reception of the translation’ (Newmark 1988: 133) focusing on the perlocutionary effect of the translation in the target language culture (Hickey 1998). The way a text is translated will depend on the reader to whom the translation is addressed: the translator must take into account that reader’s knowledge and expectations, which may be very different from those of the target reader of the source text. Here we illustrate how corpora can provide translators with ways of identifying such differences, and of formulating and testing hypotheses as to appropriate translation strategies. Corpora are not a universal panacea for the translator; but insofar as translators may spend over half their time looking for information of various kinds (Varantola 2000: 123), they can often provide a significant resource.

We view the translation process as involving three phases – while recognising that in practice these are intertwined rather than strictly consecutive.

a. Documentation. The translator skims through the source text and collects documents and tools which they consider relevant (similar texts, specialised dictionaries, terminology databases, translation memories, etc.). Where the domain is unfamiliar, the translator may spend a significant amount of time simply reading about the topic. In this phase, corpora of documents from that domain can provide readily consultable collections of reading materials, and a basis for acquiring conceptual and terminological knowledge. (The source text itself can be treated as a mini-corpus, and analysed computationally to identify features for which appropriate reference tools will be needed.)

b. Drafting. The translator identifies specific problems in interpreting the source text and producing the translated one. They formulate and evaluate possible interpretations of the source text and possible translations, selecting those judged most appropriate. Corpora can assist in all these processes: as Varantola notes (2000: 118), ‘Translators need equivalents and other dictionary information, but they also need reassurance when checking their hunches or when they find equivalents they are not familiar with.’ Corpora can provide such reassurances.

c. Revision. The translator and/or revisor evaluates the draft translation, checking its readability, comprehensibility, coherence, grammaticality, terminological consistency, etc. Again, corpora can reassure in these respects. (The target text itself can be treated as a mini-corpus, and analysed to identify features which may be out-of-place.)

In what follows we illustrate ways in which corpora – either existing, or constructed ad hoc – can aid the translator in these three phases. Thereby we hope also to illustrate their relevance to translator training – both as reference tools to be created and consulted, and as means to enhance learner understanding and awareness of the translation process itself. We assume the reader is familiar with standard corpus query functions, such as concordancing, word and n-gram listing and collocate extraction (see chapters by Scott, Tribble, Evison, Greaves and Warren, this volume). Results shown in this chapter were generated using XAIRA (Dodd 2007), AntConc (Anthony 2007), ParaConc (Barlow 2004), and WordSmith Tools (Scott 2008).

2. How do corpora fit in?

In principle, corpora are hardly a novelty for translators. There is a long tradition of using ‘parallel texts’ as documentation – collections of texts similar in domain and/or genre to the source and/or target text (Williams 1996). Before the advent of electronic texts and software to search and analyse them, a use of ‘parallel texts’ required the translator to first locate them, and then to read them extensively to extract potentially relevant information of various kinds – typically terminology to construct glossaries. Today, queriable corpora make extensive reading less necessary – though compiling and browsing a corpus of ‘parallel texts’ can still be useful for the translator to familiarise him- or herself with the domain(s) and genre(s) involved (see Section 3).

Drafting the target text requires understanding the source text, and assessing strategies to bring about the desired effect on the target reader. Not only language problems are at stake. The translator needs to have a good knowledge of the source text culture, and of the extent to which this knowledge is likely to be shared by the target reader – bearing in mind that the translator’s own knowledge cannot serve as a model. For an educated reader of Italian – and, one hopes, a translator from Italian – a mention of the provincial town of Salò will immediately bring to mind the republic set up after Italy’s surrender in the Second World War. For an educated English reader, this association may well have to be spelt out in the target text. A large general corpus of English can show whether this is likely to be necessary: the 100-million-word British National Corpus (BNC-XML 2007) contains only four mentions of the town, and one of these feels the need to explain the association:

Hitler had Mussolini rescued from Rome and installed as head of the Republic of Salò, a small, relatively insignificant town on the western shores of Lake Garda, but it was a temporary measure.

(ANB 226)

Corpora often provide explanations of names and terms which may be unfamiliar to the target reader (or indeed to the translator themselves) – and also, in this case, a ready-made chunk which might be incorporated into the target text with little modification.

Other resources may of course provide such information – dictionaries and encyclopedias, internet search engines, or even friendly experts and discussion lists. But corpora, because they can provide data which is not pre-digested but comes in the shape of samples of actual text, allow translators to acquire and apply skills which are after all central to their trade – ones of text interpretation and evaluation.

This is particularly true for specialised translations, where the translator may need to get acquainted with not only the terms and concepts of the domain, but also the rhetorical conventions of the genre. Consumer advice leaflets in Italian generally opt for an impersonal style (This should not be done), whereas English ones tend to address the reader directly (Do not do this). Italian leaflets also tend to support advice by reference to institutional frameworks. The two texts which follow come from web pages of the Inland Revenue services of the two countries – a nightmare to pragmatically translate (but foreigners also pay taxes):

How to pay Self Assessment

This guide offers a reminder of Self Assessment payment deadlines and explains all of the available payment options.

HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) recommends that you make your Self Assessment payments electronically. Paying electronically:

• is safe and secure

• gives you better control over your money

• provides certainty about when your payment will reach HMRC

• avoids postal delays

• may lower your bank charges

• lets you pay at a time convenient to you if you use Internet or telephone banking

Now the Italian text – in machine translation, with obvious lexicogrammatical errors corrected:

Practical guide to the payment of taxes

To pay taxes, contributions and duties, all taxpayers, with or without VAT numbers, must use the form ‘F24’ with the exception of central Administrations of the State and public bodies subject to the ‘single treasury system’.

The model is defined as ‘unified’ in that it allows the taxpayer to effect payment of the sums due in a single operation, compensating payment with any tax credits (on compensation, see chapter 4).

The F24 form is available from banks, collection agencies and post offices, but can also be downloaded from the Internet site of the Revenue Agency.

Comparing corpora of such texts is clearly useful to distinguishing reader expectations in the two cultures, even if this may pose the pragmatic translator as many problems as it solves.

3. What corpus?

Monolingual corpora

General reference corpora

General reference corpora such as BNC-XML (2007) are designed to provide information about the language as a whole, showing how it is generally used in speech and writing of various kinds. Let us consider some of the problems to be faced in drafting a translation of the following sentence into English – assuming English is the translator’s second language, as is often the case (Campbell 1998; Stewart 2001).

Tony’s Inn infatti offre le stesse comodità di una camera d’albergo, ma vissute in un ambiente più raccolto e domestico.

This comes from an Italian web page advertising a bed-and-breakfast establishment. Google’s machine translation reads:

Tony’s Inn in fact offers the same comforts of a hotel room, but lived in a collected and domestic atmosphere more.

The source text talks about comodità … vissute (comforts … lived). Let us first hypothesise that comforts is an appropriate translation of comodità. This is supported by a search with XAIRA in the BNC, which finds 213 occurrences of comforts as a plural noun, including several from similar contexts:

1 The hotel combines Tyrolean hospitality with all modern comforts in a luxurious setting with a high standard of service. (AMD 1352)

2 The same deal in the swanky Old Istanbul Ramada Hotel with all comforts and casino is £326. (ED3 1667)

3 Originally a 17th century patrician house, this is a lovely unpretentious hotel with the comforts and atmosphere of a private home. (ECF 4319)

But can you live comforts? A collocation query lists the most frequent verb lemmas in the seven words preceding and following the noun comforts: BE (95), HAVE (33), ENJOY (16), PROVIDE (11), DO (11), WANT (8), COMBINE (6), OFFER (6), LIVE (6), MAY (6), MAKE (5), GET (5), CAN (5). A specific collocation query for LIVE shows the following concordance lines:

1 Six residents are currently living there and enjoying the comforts of a very homely atmosphere. (A67 145)

2 I’m afraid we don’t have too many comforts or luxuries here. We live only on the ground floor, of course. (APR 1863)

3 In any case, Charles Henstock cared little for creature comforts, and had lived there for several years, alone, in appalling conditions of cold and discomfort. (ASE 289)

4 The island abounds in pleasing scenes, and a season may be well spent there by those who desire to live near city comforts. (B1N 125)

5 Now we are en route to Auxerre and the comforts of an English family living in France. (CN4 727)

6 She had her comforts. She lived in luxury. (H9C 1128)

Alas, in none of these is comforts the object of LIVE, underlining the importance of looking at actual instances before jumping to conclusions. But looking at these instances suggests an alternative hypothesis, ENJOY (line 1) – one supported by the position of ENJOY in the collocate list. The instances with ENJOY + comforts include:

1 Six residents are currently living there and enjoying the comforts of a very homely atmosphere. (A67 145)

2 Many illustrious visitors, including such notables as Wagner, Oscar Wilde, Garbo and Bogart have enjoyed the style and comforts of this hotel. (ECF 749)

3 Enjoy all modern comforts in an historic parador. (C8B 2394)

4 Guests at the Pineta share the landscaped gardens and benefit equally from the excellent service and comforts enjoyed by those staying in the main building. (ECF 3332)

This thus seems an appropriate translation hypothesis. And what about un ambiente più raccolto e domestico (a collected and domestic atmosphere more)? Line 1 in the last concordance suggests the phrase homely atmosphere, and looking at other instances of this string, we also find a suggestion for the translation of raccolto, namely intimate:

1 A delightful Grade 2 listed building of architectural and historical interest with a wealth of oak and elm panelled walls, beamed ceilings and large open fireplaces creating an intimate and homely atmosphere. (BP6 573)

2 This intimate family hotel offers a warm welcome to a homely atmosphere and the management prides itself on offering a choice of good local cooking in its dining-room. (ECF 2434)

This leaves little doubt as to the appropriacy of the collocation intimate + atmosphere, of which further instances appear in similar texts. These also suggest that intimate should precede homely, our other modifier of atmosphere:

1 This is an impressive hotel with an intimate and peaceful atmosphere. (ECF 3647)

2 This is a property still small and smiling enough to be called a ‘home’ rather than a hotel, with an intimate and friendly atmosphere. (ECF 5213)

3 There are just eight bedrooms and two suites so an intimate, friendly atmosphere prevails. (ECF 5341)

4 Intimate atmosphere, excellent menu and friendly service. (ECS 2041)

There is, however, a remaining uncertainty which a sharp-eyed translator will have spotted. Many of these lines come from the same text (ECF) – Citalia Italy Complete, a tourist handbook. Are we simply endorsing the idiosyncratic uses of a particular publication? The translator must decide whether this source is linguistically authoritative, and/or whether there are enough other instances to corroborate these uses. Our final choice for this translation would be an intimate and homely atmosphere – a phraseology in fact found in another text (BP6).

With this example, we hope to have illustrated how a corpus can provide a means not only of testing particular translation hypotheses, but also of formulating further hypotheses as a result of cotextual encounters. But let us now switch our direction of translation to consider an English source text. A corpus can cast light on aspects of the source text of which the translator may not otherwise be aware, particularly if their knowledge of the source text language is limited. An example is connotation. Aston (1999) discusses the opening sentence of Bruce Chatwin’s novel Utz (1989: 7):

An hour before dawn on March 7th 1974, Kaspar Joachim Utz died of a second and long-expected stroke, in his apartment at No. 5 Siroká Street, overlooking the Old Jewish Cemetery in Prague.

A BNC search for collocates of the lemma OVERLOOK shows that the places overlooked (in the literal sense) are mountains, rivers, oceans, ports, squares and gardens – views which generally have pleasant connotations. To use Louw’s terms (1993), overlook appears to have a positive semantic prosody. In the rare instances where the place overlooked is clearly unpleasant, such use appears to be marked, aiming at a particularly creative effect, such as irony:

The difficulty is that some people actually like Aviemore. Not only do they tolerate the fast-food shops serving up nutriment that top breeders wouldn’t recommend for Fido, they go as far as purchasing two expensive weeks in a gruesome timeshare apartment, and sit smoking all day on a balcony overlooking the A9.

(AS3 1368)

The corpus here suggests two alternative interpretations of the source text. Either Utz’s view is to be seen as pleasant, and the Old Jewish Cemetery is a nice place, or else the writer is being ironic, and the view – acting presumably as a reminder of mortality – is rather less pleasant. This being the very first sentence of a literary text, one might argue that it is deliberately designed to leave the reader uncertain as to its interpretation, and that the translator should seek out a formulation which has similar ambiguity to achieve the same effect. Stewart (2009) proposes pedagogic activities to enhance the translator’s awareness of semantic prosodies, showing how comparison with a source language corpus can be key to the formulation of appropriate translation hypotheses.

A methodological point to emerge from these examples is the role of collocation in the translator’s use of corpora. Our analysis of OVERLOOK was based on its collocates, which enabled identification of its semantic prosody. Our selection of ENJOY + comforts derived from observing the collocates of the latter. Even where the translator has no hypothesis as to a possible translation, it may be sufficient to examine the collocates of a nearby item for which a confident hypothesis is available. Possible solutions to many of the translator’s lexical problems can be found hidden in the corpus cotext, as Sharoff (2004) demonstrates – though of course they must be tested prior to adoption.

Specialised corpora

As Sinclair pointed out (1991: 24), we should not expect a general reference corpus like the BNC to adequately document specialised genres and domains. For this we need more specialised corpora, containing reasonably ‘parallel’ texts to that being translated, as more likely to document the conventions of the genre and the concepts and terms of the domain. As we have seen in the examples above, relevant discoveries can often occur while the user is searching for something else, and this is even more probable with specialised corpora. Unlike general corpora, they can also be used in the documentation phase to familiarise the translator with the domain and clarify terminology (Maia 2003). For example, many terms and their definitions and explanations can be located via explicit markers (Pearson 1998: 119). Here is a definition from a specialised corpus in vulcanology, located by searching for defined as:

The third are eruptions confined within paterae (a patera is defined as an irregular crater, or a complex one with scalloped edges).

In scientific writing in French, the expression on dira has a similar function of introducing definitions or near-definitions. In a corpus on the birth of mountains we find, inter alia:

1 Définition de la déformation. On dira qu’un corps est déformé s’il y a eu variation de la forme, des dimensions

2 Si la dimension de l’objet augmente, on dira alors qu’il y a eu dilatation positive de l’objet

3 On dira qu’une déformation sera homogène, si les conditions énoncées ci-dessous

4 Pour tous les autres cas, on dira que la déformation sera hétérogène.

5 ne resteront pas perpendiculaires dans l’état déformé. On dira alors que la déformation est rotationnelle.

6 de longueurs d’onde différentes on dira que les plis sont disharmoniques.

All these lines define or explain terms in this domain.

Specialised corpora do not grow on trees. They have to be compiled, and those who compile them are often reluctant to share what they perceive to be valuable objects. They also have to be appropriate for the task. Establishing the domain and genre of the text to be translated are the first steps a translator needs to take in the documentation phase, asking what the text is trying to do, what it is about, and who it is it aimed at. Is it a didactic text, in which definitions and explanations are provided? Is it a research article, where there will be fewer definitions and explanations, since the author will take it for granted that the reader is already familiar with the subject? A research article may require much research on terminology, while a divulgative text may require more work on cultural allusions and connotations. To translate the former, a specialised corpus will be near-essential, while for the latter a general corpus may be more appropriate. And if a specialised corpus is desirable but not available, how to create one?

Constructing specialised corpora

Creating a corpus involves putting together a collection of relevant documents. Ideally these should already be in electronic form, and this usually means locating and downloading them, converting them to a format which query software can handle, and cleaning them of unnecessary parts such as tables and images, HTML links and formatting instructions (see chapters by Koester, Nelson and Reppen, this volume). You may also want to add markup indicating the source, category and structure of each document, and perhaps categorise each word – decisions which will depend on the resources available. Last and not least, there are copyright issues – is it all legal?

In assessing documents for inclusion in a corpus, we first need to consider their domain and genre, and the extent to which these ‘parallel’ those of the source/target text. We also need to consider the extent to which they can be considered authoritative (clearly, it could be unwise to treat texts written by non-experts, or by non-native authors, as reliable sources of terminology, explanations or cultural conventions). The source of a document will often provide indications in these respects: a research project’s website, for example, is likely to contain material produced by expert authors, a blog or chat less likely to. A third criterion is the intended reader, and their presumed expertise in the field (Bowker and Pearson 2002). Divulgative and/or didactic texts, written by experts (or pseudo-experts) for non-experts, are more likely to contain definitions and explanations (Wikipedia is a notorious example) – potentially useful documentation for the translator, who may well also be a non-expert. This entails, essentially, categorising corpus texts as either ‘parallel’ or ‘explanatory’, and ‘authoritative’ or ‘debatably authoritative’, so that searches can be performed on different subcorpora as required.

Locating and downloading appropriate documents using internet search engines can be a painful process. WebBootCaT (Baroni et al. 2006) allows the user to automatically retrieve and clean large numbers of documents using a series of strings as ‘seeds’, where the user can gradually refine these to increase precision, and also restrict searches to certain types of sites. But how big does a specialised corpus need to be? Corpas Pastor and Seghiri (2009: 86–92) candidate a software procedure which progressively analyses type/ token ratio, indicating when this ceases to decline significantly by addition of further documents.

Reference corpora like the BNC are heavily marked up with information about each document – its source, its categorisation, its structure (sections, headings, paragraphs, notes, sentences, etc.), the part-of-speech and root form of each word, and indeed about its markup, following international guidelines on text encoding (TEI Consortium 2007). The lone translator is unlikely to have the time, resources or expertise to mark up each document in detail. But where a corpus is being constructed as a shared resource for lengthy use, this effort may be worthwhile for the greater search precision and potential for interchange it permits.

And is it all legal? It is generally considered fair practice to retrieve available texts from the web for personal non-commercial use. But it is not considered fair practice to reproduce or modify those texts, making them available to others from a different source or in different forms (Wilkinson 2006). A double-bind: without permission, one can only construct a corpus for personal use, but without wider use it may not be worth the effort to construct it. Without permission, there is no way a translation teacher can construct a corpus to use with learners. If permission is sought, it may not be granted, or else understandably charged for, and limitations may be posed upon the amount of text (Frankenberg-Garcia and Santos 2003). Unless, of course, your corpus consists only of documents of your (or your customer’s) own. Or unless your corpus is a virtual one, consisting simply of a set of categorised URLs to which queries are addressed over the internet – a possible direction for the future (see 5 below).

Multilingual corpora

Given that translators are concerned with (at least) two languages, there are advantages in having access to corpora containing similar documents in two – or several – languages. Here we illustrate uses of some of the main types available, limiting ourselves to a bilingual context (see also Kenning, this volume).

Comparable corpora

In the documentation phase, comparable specialised corpora, constructed using analogous criteria for both languages, provide the translator a means to familiarise him- or herself with the domain and genre in both source and target languages, providing ways of identifying intercultural differences and similarities. One typical use is that of identifying equivalent terms. For a small comparable corpus on electric motors in English and Italian, the lists that follow (generated with AntConc) show the most frequent words and two- to three-word n-grams in each component (excluding function words):

(Longer) lists could be useful to a translator needing to produce an Italian version of an English electric motor manual, or vice versa. Some equivalents can be seen in the n-gram lists: electric motor/motore elettrico; magnetic field/campo magnetico; others can be deduced from extending comparisons to the wordlists: three phase/trifase. If no equivalent is immediately locatable, collocation methods can be used. For instance, over 10 per cent of the 722 occurrences of torque occur with speed as a collocate. If we know that the Italian for the latter is velocità, a glance at the most frequent lexical collocates of velocità in the Italian corpus leads to coppia as an equivalent.

It can, however, be difficult to build strictly comparable corpora for specialised domains. Given the dominance of English, analogous scientific writing in other languages may be hard to find. Things may seem easier for technical documents, but we all know how manuals for imported goods contain errors. Comparable corpora always raise issues of just how comparable and authoritative they are.

Parallel corpora

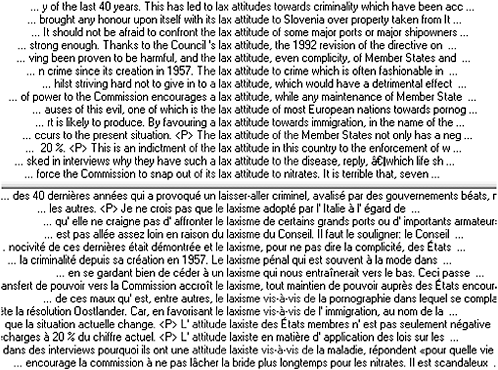

Parallel corpora (not to be confused with ‘parallel texts’) ideally consist of texts in one language and translations of those same texts in another language. Every translator’s dream is a resource which instantly provides reliable candidate translations, and this is what a parallel corpus ideally offers. Figure 36.1 shows a concordance for the English lax attitude(s), where the bottom half of the window lists the equivalents in the French part of the corpus. These highlight the preference for laxisme (notwithstanding the availability of attitude laxiste), with the possible alternatives laisser-aller and lâcher la bride:

Figure 36.1 Parallel concordance (English–French) for lax attitude(s) (ParaConc).

Given the difficulty of obtaining permission to use both a text and its translation, publicly available parallel corpora are few, most being based on multilingual official documents. This concordance comes from a corpus of European Parliament proceedings (OPUS, see Tiedemann 2009, offers downloadable parallel corpora for European languages from the European Parliament, the European Medicines Agency, Open Office and Open Subtitles. An online query interface is also available online). The original language is unspecified, so the parallel segments may in fact both be translations from a third language. One available parallel corpus where the relationship between text pairs is stated is COMPARA (English and Portuguese: Frankenberg-Garcia and Santos 2003), allowing searching of original texts or translations. COMPARA is also one of the few parallel corpora to allow online querying of copyright material.

One option open to the professional translator (and even more so to the translation agency) is to construct their own parallel corpora, using source and target texts of previous translation jobs. This requires the alignment of each text pair, indicating which segment in one text corresponds to which segment in the other, generally on a sentenceby-sentence basis, using programmes such as Winalign or WordSmith Tools (Chung-Ling 2006; Scott 2008). Unless, that is, a translation memory system was used for the translation, in which case source and target texts may have been saved in an aligned format. Translation memories can themselves be considered parallel corpora, but since they contain pairs of segments rather than pairs of texts, and only one translation per segment, they offer less contextual information, and none on frequency or alternatives.

Parallel corpora lead one to reflect on alternative ways of translating a source text. Their limit is that the user exploits previous translations as a basis for new ones, and hence risks producing ‘translationese’ rather than conforming to the conventions of original texts in the target language (Williams 2007): in COMPARA, already is used twice as often in translations from Portuguese as it is in original English texts (FrankenbergGarcia 2004: 225). But there are also clear arguments in favour, particularly in training contexts:

They [translators] have to gauge how much of the material in a source text is directly transferable to the target language, how much of it needs to be adapted or localized in some way, whether any of it can, or indeed should, be omitted. The answers to questions of this nature cannot be found in comparable corpora because these issues never arise in a monolingual text-producing environment. They only arise because of the constraints of a text composed in another language. The answers must therefore be sought in parallel corpora.

(Pearson 2003: 17)

Multiple translation corpora

Pearson’s observations also hold for multiple translation corpora. These are parallel corpora which include several translations of the same texts, so a search can find all the corresponding strings in source texts and all the various translations of each. This allows comparison of different translations of the same thing in the same context (Malmkjær 2003). But since multiple translations of the same text are rare, most such corpora use learner translations, particularly lending themselves to error analysis (Castagnoli et al. 2009) – again making them of particular value in training contexts.

4. Corpora in translator training

The use of corpora in translator training has to be viewed from several perspectives. Most simply, it can be viewed as providing the skills necessary to use corpora in the professional environment, with simulations of real tasks in the various phases of the translation process. More broadly, it can be seen as a means of raising critical awareness of this process, with wider educational goals (Zanettin et al. 2003; Bernardini and Castagnoli 2008). Thus constructing and using comparable corpora may develop awareness of crosscultural similarities and differences; parallel corpora may develop awareness of strategic alternatives and the role of context. It can also provide opportunities to improve linguistic and world knowledge, to acquire new concepts and new uses (not least through incidental discoveries), along lines discussed in work on teaching and language corpora (Aston 2001; O’Keeffe et al. 2007). And it can be an opportunity to develop awareness of the technical issues involved in computer-assisted translation, such as the representativeness and reliability of corpora, standards of encoding and markup, query techniques, procedures of alignment and of term extraction, etc. Such awareness will be essential for the future translator to keep abreast of new technological developments. Last but not least, it may motivate, increasing engagement with the process of translation and with learning how to translate.

5. Future prospects

To the professional translator, time is undoubtedly money. Corpus construction and corpus use are time-consuming, and while survey data indicates a general interest on the part of translators (Bernardini and Castagnoli 2008), in order for corpora to become a standard resource it is essential to find ways of speeding these up.

Corpus construction from the internet can, it has been shown, be largely automated (Baroni et al. 2006). However the interfaces offered by the major search engines do not facilitate this, and there are obvious copyright implications attached to any process which involves automatic downloading (rather than consultation) of documents. Improved document categorisation may, however, allow web concordancers to generate concordances and perform other linguistic analyses from ‘virtual corpora’, by consulting and analysing documents of specified domains, genres and authoritativeness, and simply passing the search results, rather than the documents, to the user (at the time of writing web concordancing services include Birmingham City University’s WebCorp, see Renouf et al. 2007; and Web Concordancer, see Fletcher 2007; see Lee, this volume). One day, similar categorisations may even allow generation of parallel concordances from document pairs of a specified type which the search software recognises as being equivalents in different languages (Resnik and Smith 2003), using automatic alignment procedures.

Another area for future development concerns the integration of corpus tools into the translator’s workbench. Today’s widely used translation memory systems offer few chances of accessing and querying corpora other than previously inserted source texttranslation pairs. Compatible interfacing of external corpora with other tools is essential if these are to be perceived by the professional translator as a help rather than an obstacle, with single-click transfer of a source text string to a corpus query, and of selected query output to the draft translation. To this end, more research on the way translators actually use corpora is needed (Santos and Frankenberg-Garcia 2007).

Increasingly, human translators will compete with machine translation, which is itself increasingly corpus-based (Somers 2003). Many of the processes described in this chapter may be incorporated into machine translation packages, thereby reducing the human workload. Currently, machine translation only yields high-quality results with repetitive and/or simplified texts, but performance can be significantly improved with appropriate lexicons (whose construction from corpus data is therefore an appropriate translator concern: Kübler 2002), and by adequate revision of the output – where corpora (as our examples using machine-translated extracts have hopefully shown) can again play an important role.

We can also hope for more research on the productiveness of corpora as translation aids. If corpus use makes for better translation than other tools (Bowker and Barlow 2008), does the quality improvement justify the effort, and at what point does the payoff start to tail off? Are corpus construction and consultation best placed in different hands (Kübler 2003)? How big – and how specialised – does a specialised corpus have to be to provide solutions to a reasonable proportion of a translator’s problems (Corpas Pastor and Seghiri 2009)? Are the roles of general and specialised corpora complementary ones (Sharoff 2004; Philip 2009)?

Finally, we can hope for more research on corpora in translator training. What, for example, are suitable corpus-based tasks in a task-based translation pedagogy (Monzó Nebot 2008; Rodriguez Inéz 2009)? And how can the widely documented potential of corpora for autonomous language learning best be interpreted to foster the autonomous acquisition of translation skills (López-Rodríguez and Tercedor-Sánchez 2008)?

Further reading

Beeby, A., Rodriguez Inés, P. and Sánchez-Gijón, P. (eds) (2009) Corpus Use and Translating. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. (Selected papers from the third Corpus Use and Learning to Translate conference.)

Bowker, L. and Pearson, J. (2002) Working with Specialised Language: A Guide to Using Corpora. London: Routledge. (A practical introduction to compiling and using specialised corpora, with exercises.)

Rogers, M. and Anderman, G. (eds) (2007) Incorporating Corpora: The Linguist and the Translator. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. (A collection of recent papers on corpora in translation studies by some of the major figures in the field.)

Zanettin, F., Bernardini, S. and Stewart, D. (eds) (2003) Corpora in Translator Education. Manchester: St Jerome. (Selected papers from the second Corpus Use and Learning to Translate conference.)

References

Anthony, L. (2007) AntConc 3.2.1, at www.antlab.sci.waseda.ac.jp/software.html

Aston, G. (1999) ‘Corpus Use and Learning to Translate’, Textus 12: 289–313.

——(2001) ‘Learning with Corpora: An Overview’, in G. Aston (ed.) Learning with Corpora. Houston, TX: Athelstan.

Baker, M. (1999) ‘The Role of Corpora in Investigating the Linguistic Behaviour of Translators’, International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 4: 281–98.

Barlow, M. (2004) ParaConc, www.paraconc.com/ (accessed 12 July 2009).

Baroni, M., Kilgarriff, A., Pomikálek, J. and Rychl, P. (2006) ‘WebBootCaT: Instant Domain-specific Corpora to Support Human Translators’, Proceedings of EAMT 2006, available at www.muni.cz/research/publications/638048/ (accessed 12 July 2009).

Beeby, A., Rodriguez Inés, P. and Sánchez-Gijón, P. (eds) (2009) Corpus Use and Translating. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Bernardini, S. and Castagnoli, S. (2008) ‘Corpora for Translator Education and Translation Practice’,in E. Yuste Rodrigo (ed.) Topics in Language Resources for Translation and Localisation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Bernardini, S. and Zanettin, F. (eds) (2000) I corpora nella didattica della traduzione/Corpus Use and Learning to Translate. Bologna: Cooperativa Libraria Universitaria Editrice.

BNC-XML (2007) The British National Corpus: XML Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Computing Services.

Bowker, L. and Barlow, M. (2008) ‘A comparative evaluation of bilingual concordancers and translation memory systems’, in E. Yuste Rodrigo (ed.) Topics in Language Resources for Translation and Localisation. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bowker, L. and Pearson, J. (2002) Working with Specialised Language: A Guide to Using Corpora. London: Routledge.

Campbell, S. (1998) Translation into the Second Language. London: Longman.

Castagnoli, S., Ciobanu, D., Kunz, K., Volanschi, A. and Kübler, N. (2009) ‘Designing a Learner Translator Corpus for Training Purposes’, in N. Kübler (ed.) Corpora, Language, Teaching, and Resources: From Theory to Practice. Bern: Peter Lang.

Chatwin, B. (1989) Utz. London: Pan.

Chung-Ling, S. (2006) ‘Using Trados’s WinAlign Tool to Teach the Translation Equivalence Concept’, Translation Journal 10(2); available at www.accurapid.com/journal/36edu1.htm (accessed 12 July 2009).

Corpas Pastor, G. and Seghiri, M. (2009) ‘Virtual Corpora as Documentation Resources: Translating Travel Insurance Documents (English–Spanish)’, in A. Beeby, P. Rodriguez Inés and P. SánchezGijón (eds) (2009) Corpus Use and Translating. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Dodd, A. (2007) Xaira 1.24, at http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/rts/xaira/Download/ (accessed 12 July 2009).

Fletcher, W. H. (2007), ‘Concordancing the Web: Promise and Problems, Tools and Techniques’,in M. Hundt, N. Nesselhauf and C. Biewer (eds) Corpus Linguistics and the Web. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Frankenberg-Garcia, A. (2004) ‘Lost in Parallel Concordances’, in G. Aston, S. Bernardini and D. Stewart (eds) Corpora and Language Learners. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Frankenberg-Garcia, A. and Santos, D. (2003) ‘Introducing COMPARA, the Portuguese–English Parallel Translation Corpus’, in F. Zanettin, S. Bernardini and D. Stewart (eds) Corpora in Translator Education. Manchester: St Jerome.

Hickey, L. (1998) ‘Perlocutionary Equivalence: Marking, Exegesis and Recontextualisation’,inL. Hickey (ed.) The Pragmatics of Translation. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Kübler, N. (2002) ‘Creating a Term Base to Customize an MT System: Reusability of Resources and Tools from the Translator’s Point of View’, in E. Yuste (ed.) Proceedings of the Language Resources for Translation Work and Research Workshop of the LREC Conference, 28 May 2002, Las Palmas de Gran Canarias: ELRA.

——(2003) ‘Corpora and LSP Translation’, in F. Zanettin, S. Bernardini and D. Stewart (eds) Corpora in Translator Education. Manchester: St Jerome.

López-Rodríguez, C. and Tercedor-Sánchez, M. (2008) ‘Corpora and Students’ Autonomy in Scientific and Technical Translation Training’, Journal of Specialised Translation, 9, available at www.jostrans.org/issue09/art_lopez_tercedor.pdf (accessed 14 July 2009).

Louw, W. (1993) ‘Irony in the text or insincerity in the writer? The diagnostic potential of semantic prosodies’, in M. Baker, G. Francis and E. Tognini-Bonelli (eds) Text and Technology: In Honour of John Sinclair. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Maia, B. (2003) ‘Training Translators in Terminology and Information Retrieval Using Comparable and Parallel Corpora’, in F. Zanettin, S. Bernardini and D. Stewart (eds) Corpora in Translator Education. Manchester: St Jerome.

Malmkjær, K. (2003) ‘On a Pseudo-subversive Use of Corpora in Translator Training’, in F. Zanettin, S. Bernardini and D. Stewart (eds) Corpora in Translator Education. Manchester: St Jerome.

Mauranen, A. (2007) ‘Universal Tendencies in Translation’, in M. Rogers and G. Anderman (eds) Incorporating Corpora: The Linguist and the Translator. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Monzó Nebot, E. (2008) ‘Corpus-based Activities in Legal Translator Training’, The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 2: 221–52.

Newmark, P. (1988) ‘Pragmatic Translation and Literalism’, TTR: traduction, terminologie, rédaction 1/2: 133–45.

O’Keeffe, A., McCarthy, M. J. and Carter, R. A. (2007) From Corpus to Classroom: Language Use and Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Olohan, M. (2004) Introducing Corpora in Translation Studies. London: Routledge.

Pearson, J. (1998) Terms in Context. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

——(2003) ‘Using Parallel Texts in the Translator Training Environment’, in F. Zanettin, S. Bernardini and D. Stewart (eds) Corpora in Translator Education. Manchester: St Jerome.

Philip, G. (2009) ‘Arriving at Equivalence: Making a Case for Comparable General Reference Corpora in Translation Studies’, in A. Beeby, P. Rodriguez Inés and P. Sanchez-Gijon (eds) Corpus Use and Translating. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Renouf, A., Kehoe, A. and Banerjee, J. (2007) ‘WebCorp: An Integrated System for Web Text Search’, in C. Nesselhauf, M. Hundt and C. Biewer (eds) Corpus Linguistics and the Web. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Resnik, P. and Smith, N. (2003) ‘The Web as a Parallel Corpus’, Computational Linguistics 29: 349–80.

Rodriguez Inéz, P. (2009) ‘Evaluating the Process and Not Just the Product when Using Corpora in Translator Education’, in A. Beeby, P. Rodriguez Inés and P. Sanchez-Gijon (eds) Corpus Use and Translating. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Santos, D. and Frankenberg-Garcia, A. (2007) ‘The Corpus, its Users and their Needs: A User-oriented Evaluation of COMPARA’, International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 12: 335–74.

Scott, M. (2008) WordSmith Tools 5.0. Liverpool: Lexical Analysis Software.

Sharoff, S. (2004) ‘Harnessing the Lawless: Using Comparable Corpora to Find Translation Equivalents’, Journal of Applied Linguistics 1: 333–50.

Sinclair, J. (1991) Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Somers, H. (2003) ‘Machine Translation: Latest Developments’, in R. Mitkov (ed.) Oxford Handbook of Computational Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stewart, D. (2001) ‘Poor Relations and Black Sheep in Translation Studies’, Target 12: 205–28.

——(2009) ‘Safeguarding the Lexicogrammatical Environment: Translating Semantic Prosody’,inA. Beeby, P. Rodriguez Inés and P. Sanchez-Gijon (eds) Corpus Use and Translating. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

TEI Consortium (eds) (2007) Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange, available at www.tei-c.org/Guidelines/ (accessed 12 July 2009).

Tiedemann, J. (2009) ‘News from OPUS – A Collection of Multilingual Parallel Corpora with Tools and Interfaces’, in N. Nicolov, K. Bontcheva, G. Angelova and R. Mitkov (eds) Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing, Vol. V. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Varantola, K. (2000) ‘Translators, Dictionaries and Text Corpora’, in S. Bernardini and F. Zanettin (eds) I corpora nella didattica della traduzione/Corpus Use and Learning to Translate. Bologna: Cooperativa Libraria Universitaria Editrice.

Wilkinson, M. (2006) ‘Legal Aspects of Compiling Corpora to be Used as Translation Resources’, Translation Journal 10(2), available at www.accurapid.com/journal/36corpus.htm (accessed 12 July 2009).

Williams, I. (1996) ‘A Translator’s Reference Needs: Dictionaries or Parallel Texts’, Target 8: 277–99.

——(2007) ‘A Corpus-based Study of the Verb observar in English–Spanish Translations of Biomedical Research Articles’, Target 19: 85–103.

Zanettin, F., Bernardini, S. and Stewart, D. (eds) (2003) Corpora in Translator Education. Manchester: St Jerome.