Chapter Two

NATIONS AND CONSTITUTIONS

Dimensions of Secular Configuration

Two powerful agencies that have done a great deal to advance social well-being in other countries are not available to our cause in this country, namely the State and the Church. Here the State represents an alien power, which is not well informed on Hindu social questions and which lacks the propelling force which the wielders of that power would come under if they were of the people, and if they shared directly in the consequences of our social evils and in the adverse feeling and sense of incongruity they create. . . . In regard to the Church also, we are at a great disadvantage. There is nothing amongst us corresponding to the great and powerful institutions called the Church in Christian countries. Our fore-fathers never thought of giving to their religion the strength of an organised religion.1

THESE WORDS were included in an address entitled “The Principles of Social Reform,” delivered in 1897 by G. Subramania Iyer to the Madras Hindu Social Reform Association. The passage emphasizes four points:(1) India is at a comparative disadvantage in its capacity to address the existence of evil in society. (2) Understanding social evil in India requires familiarity with Hindu society. (3) A government “of the people” would be for the people in the sense that its popular mooring would ensure efforts to counteract entrenched and severe social ills. (4) The Hindu religion lacks the organizational structure to mobilize effectively on behalf of social reform and well-being.

Fifty years later an important change had occurred: The State no longer represented an alien power. One hundred years later an important assumption had not as yet been proven: that a democratically constituted State would necessarily be committed to the eradication of social evil.2 Thus in 1947 the Constituent Assembly of independent India produced the world’s longest Constitution, key provisions of which reflected the spirit of social reform that animated many of its framers’ endeavors. In the language of a Supreme Court opinion: “The Indian Constitution is first and foremost a social document. The majority of its provisions are either directly aimed at furthering the goals of the socio-economic revolution or attempt to foster this revolution by establishing the conditions necessary for its achievement.”3 But as a new century approached, it was less than clear that this document had contributed much to the alleviation of the massive burdens of social iniquity that had preoccupied Mr.Iyer at the close of the last century. Fittingly, fifty years of independent statehood became an occasion for both celebrating successes in democratic governance and regretting failures in achieving a just social order.

If the State no longer represented an alien power and could therefore, as in other countries, contribute (however inadequately) to the welfare of society, the availability of the Church to the cause of social well-being had not been affected by a similar transformation in its fundamental character. The efforts over the years of Hindu reformers to modify socially regressive religious practices had achieved some measurable positive impact, but Iyer’s analysis of the weakness of decentralized and fragmented ecclesiastical power in effecting major change had not lost its relevance. Iyer, however, might have pointed out that the same structural advantage that made the Church in some countries an effective instrument of social reform made it in others a substantial obstruction.4 Moreover, in India, unlike in many of the Christian countries to which he alluded, the prevalence and perpetuation of social evil were closely connected to a religiously based way of life. If the Hindu forefathers had “thought of giving to their religion the strength of an organised religion,” then logic suggests that, in contrast with countries where the Church had become a powerful agency fighting social ills beyond its domain, an authoritative religious voice might very well have become a linchpin in a concerted effort to preserve the status quo.

All of this points to the need to place the Indian secular experience within a comparative constitutional context. T. N. Madan has observed that “Secularism in India is a multivocal word: what it means depends upon who uses the word and in what context.”5 Moving from an intrasocietal to an intersocietal context reinforces his insight. Thus the points made in Iyer’s speech to the Reform Association, all of which are, as we shall see, central to an understanding of religion and politics in India, require an analytical framework broader than the Indian case to comprehend their significance. Accordingly, this chapter explores the concept and practice of the secular constitution within three nations—India, Israel, and the United States—that are committed, albeit in different ways, to the principle of religious liberty.

The manner in which a polity constitutes religion is arguably its most revealing regime-defining choice.6 These three cases provide an opportunity to consider how contrasting constitutional treatments of religion reflect distinctive patterns of secular foundational commitment. In their unique ways, all three countries emerged from the shadow of British colonialism under circumstances that called attention to the political problems associated with religious diversity. In each instance, the project of nation-building culminated in a constitutional culture within which proposed solutions to the perplexing matrix of issues concerning Church and State make more or less good sense. These solutions are worth investigating for a variety of reasons, including their potential for constitutional transplantation; thus determining which approaches are appropriate for crossnational application requires careful attention to national comparisons and their constitutional implications.7

In the cases of India and Israel, these kinds of assessments are frequently made by judges in Church/State cases, with the American experience receiving the lion’s share of attention. On the other hand, American judges have paid scant attention to developments elsewhere.8 This one-directional path of influence is easy to understand in light of the much longer span of American constitutional history. But given the longstanding confusion and controversy in both the judiciary and academic circles regarding the meaning of the First Amendment’s religion clauses, the reasons for foreign interest in American precedents might still be somewhat mystifying to a student of the Supreme Court. Indeed, with the possible exception of the Fourteenth Amendment, there is no section of the Constitution whose meaning is more contested. Understandably, then, such a student might well wonder how any sort of consistent and coherent message about Church and State could be getting across to observers abroad.

Viewed from abroad, however, the divisions within the American legal community on constitutional matters pertaining to religion appear relatively inconsequential. Thus Israelis tend to see the American solution as clearly distinguishable from their own (for some to be approximated or even emulated, for others to be avoided), one where, in the words of another foreign observer, Alexis de Tocqueville, “[R]eligion is a distinct sphere, in which the priest is sovereign, but out of which he takes care never to go.”9 In Israel, where religion is so firmly embedded in conceptions of national identity, debates are heard over religion’s proper place in the public square, but their juxtaposition with similar debates in the United States only highlights for Israelis the distinctiveness of the critical American presumption that religious activity is essentially a private affair. Though in India religion’s embeddedness in prevailing notions of national self-understanding proves ambiguous, in marked contrast to the United States it is deeply embedded in the country’s social structure, leading Indians to perceive American approaches to Church/State relations as decidedly separatist at their core. Despite a number of serious and influential voices in the United States urging a more “accommodationist” position as truer to the nation’s ideals, the perception of a characteristically American constitutional segmentation of the spiritual and temporal domains still stands.

Perceptions such as these suggest how the comparative approach accentuates regime differences. While George Fletcher is surely right in insisting that resolving legal disputes is best accomplished by “turn[ing] inward”through reflection upon the legal culture within which a given dispute is located,10 this sort of effort is not incompatible with an outward turn that looks comparatively to emphasize defining aspects of constitutional identity. This chapter focuses on constitutional policy regarding Church and State, but behind this is a broader engagement with three constitutional cultures. The constitutional provisions that address religious issues need to be examined for the messages they carry concerning distinctive conceptions of national identity that in turn demarcate critical parameters for constitutional adjudication. In this chapter, I introduce a conceptual mapping of the three dominant approaches to the secular constitution embodied in the experiences of India, Israel, and the United States. These models are developed further in the next two chapters, which concentrate on issues within the three constitutional settings that underscore the distinctive—although not mutually exclusive—orientations prevailing in these countries. There I elaborate on the assimilative logic behind American Church/State experience and the visionary commitments animating Israeli approaches to religious diversity, both of which provide a comparative background for pursuing the ameliorative assumptions, aspirations, and implications of Indian constitutional secularism.

THREE CONSTITUTIONAL MODELS: A PRELIMINARY ACCOUNT

In Book IV of Aristotle’s Politics, the philosopher and father of comparative constitutionalism turns his attention from ideal to actual constitutions: Which is the best constitution practicable for this or that set of circumstances, and what are the best ways of preserving existing constitutions? “[P]olitics has to consider which sort of constitution suits which sort of civic body. The attainment of the best constitution is likely to be impossible for the general run of states; and the good law-giver and the true statesman must therefore have their eyes open not only to what is the absolute best, but also to what is the best in relation to actual conditions.” 11 Aristotle refers in this context to a common error, which is to assume that there is only one sort of regime type—for example, democracy or oligarchy—when in fact there are different varieties for each scheme of constitution. Constitutions vary because of variations in the makeup of the body politic.

Aristotle’s point is applicable to the constitutional configuration of secular polities. Here too it is possible (and in a certain sense desirable) to imagine the ideal arrangement for achieving the perfect balance between Church and State, and therewith the maximum protection for both spiritual and temporal concerns. But just as the lawgiver and statesman should be attentive to “actual conditions,” so must the student of religion and politics. The analysis of constitutional possibilities for addressing this relationship must be sensitive to the “facts on the ground,” especially the manner in which religious life is experienced within any given society and how this experience affects the achievement of historically determined constitutional ends. As Michael Walzer has pointed out, “[T]here are no principles [beyond a basic respect for human rights] that govern all the regimes of toleration or that require us to act in all circumstances, in all times and places, on behalf of a particular set of political or constitutional arrangements.”12 For example, “[W]e [cannot] say that state neutrality and voluntary association, on the model of John Locke’s ‘Letter on Toleration,’ is the only or best way of dealing with religious and ethnic pluralism. It is a very good way, one that is adapted to the experience of Protestant congregations in certain sorts of societies, but its reach beyond that experience and those societies has to be argued, not simply assumed.”13

Walzer’s point can be taken an additional step. Not only is the “one size fits all” option unwise and unrealistic, so too is the expectation that a specific formula for constitutional structuring of the relations between Church and State will or ought to apply uniformly within a given polity. Such expectations have been nurtured by our conventional labeling of constitutional approaches to religion and politics. In their generally insightful five-nation comparative study, Stephen V. Monsma and Christo pher Soper discuss three contrasting models of Church/State arrangements: strict separation, establishment, and structural pluralism. Among their objectives is the demonstration of the shortcomings of the strict separation model (exemplified by the American experience), which ultimately fails to achieve their basic goal or ideal, governmental neutrality on matters of religion. Thus they criticize American (and Australian) courts’ treatment of free exercise rights, because it allegedly discriminates against religious conscience in favor of secular policy, violating the goal of neutrality rightly understood.14 But reasonable though their specific criticisms may be, their general critique of the judicial subordination of religious conscience to collective goals presumes a virtue of neutrality that may not consistently hold for one society, let alone for all societies. What should be so sacrosanct about strict neutrality between religion and nonreligion in the absence of some overriding principle to which the commitment is connected? In the American case, strict separation should not be viewed as a model, but rather as a doctrine that may in some settings advance the cause of constitutive ends, but which in others may obstruct their attainment. Models of secular constitutional development need to be framed in accordance with these regime-specific ends; they should, as Aristotelian political science teaches, “distinguish the laws which are absolutely best from those which are appropriate to each constitution.”15

A rough typology can assist in framing the analysis that follows. It requires, however, that we be careful not to identify the secular constitution with secularization, meaning, among other things, “the separation of the polity from religion.”16 As Rajeev Bhargava has noted, “[S]ecularism is compatible with the view that the complete secularization of society is neither possible nor desirable.”17 The latter concept denotes a process—usually associated with modernization—in which the various sectors of society are progressively liberated from their domination by religion; but the emphasis on separate spheres unnecessarily obscures the diversity among regimes that aspire to be constitutionally secular. More separation does not in itself mean greater constitutional legitimacy. Also, the secular constitution should be distinguished from secularism as an ideological commitment whose proponents are often hostile toward religion. To be sure, a secular constitution may rest upon an antipathy toward religion, just as it may be premised upon a radical separation of temporal and spiritual spheres. But in the analysis that follows, these assumptions are not intrinsic to the logic of secular constitutional development. In referring to the secular constitution, what is meant is simply this: a polity where there exists a genuine commitment to religious freedom that is manifest in the legal and political safeguards put in place to enforce that commitment. 18

Two dimensions stand out in considering alternative approaches to the secular constitution. The first is “the consequential dimension of religiosity,” 19 which here connotes more than a subjective determination as to whether religion is deemed important by the people who practice it; it speaks to religion’s explanatory power in apprehending the structural configuration of a given society. This dimension is also captured by the anthropological concept of a cultural “way of life,” in which a (religious) system of beliefs, symbols, and values becomes ingrained in the basic structure of society and ultimately sets the parameters within which vital societal relations occur. Avishai Margalit and Joseph Raz have employed the term encompassing group to highlight a set of characteristics that should qualify a specific collection of people for national self-determination. Such a group will “possess cultural traditions that penetrate beyond a single or a few areas of human life, and display themselves in a whole range of areas, including many which are of great importance for the wellbeing of individuals.”20 They point out that some religious groups, by

virtue of their rich and pervasive cultures, meet these conditions, although my analysis offers no opinion on the desirability of national self-determination in such instances. Their construction offers an apt basis for distinguishing two senses of religion, thick and thin (or demanding and modest), the latter referring to a situation where religion bears only tangentially upon the life experiences of most people.

A second dimension refers to the official cognizance of religion, more specifically, the extent to which the State is decisively identified with any particular religious group. The relevant distinction here has less to do with concerns about the public square, that is, the question of governmental support, hostility, or indifference toward religion, than it does with the official favoring of one religion over others for special benefits. Thus in the United States, all separationists and most accommodationists are united (with only trivial exception) in requiring impartiality in the State’s dealings with religious groups. Both sides are committed to neutrality among religions but differ over whether there should be neutrality toward religion. While governmental neutrality is thus key to this dimension, the formal identification of a State with a particular religion does not in itself remove that State from the category of secular regimes. Sweden (unlike Israel) has had an established Church, but that legal designation hardly disqualifies that country from asserting its secular credentials. Were it to become known as “the Lutheran State,” and consistent with that description were it to distinguish in some of its policies and symbols between Lutherans and non-Lutherans, it would violate an essential requirement of liberal constitutionalism, but still admit of the possibility, as the Israeli example will show, of achieving a secular (albeit not unambiguously liberal) constitution.

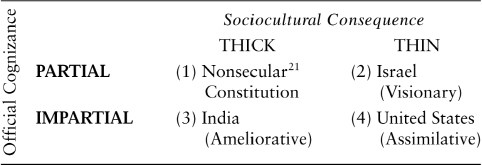

These two dimensions create quadrants that include three variations on the theme of the secular constitution, each illustrated by one of the countries under consideration.

The lines that separate these four quadrants do not demarcate arenas whose confines are wholly dissimilar from one another. They are meant to be suggestive of orientations toward the secular constitution that are also expressive of salient aspects of national identity. They highlight contrasting emphases, rather than set forth mutually exclusive approaches. Thus in (2), Zionist aspirations for a homeland for the Jewish people frame the debate over Church/State relations, but the predominantly secular orientation of most Israeli Jews tends to dampen whatever theocratic impulse might reside in the founding commitment to ascriptively driven nationalism.22 In (4), where the Constitution is the paradigmatic case of a governing charter that is central to its people’s sense of nationhood, the relative thinness of religion in the United States, conjoined with a constitutional requirement of nonestablishment, encourages the assimilation of a diverse population into a constitutive culture of ideas.23 And in (3), the constitutional promise of State neutrality toward religious groups is a corollary of the transformational agenda of Indian nationalism, a principal objective of which is the democratization of a social order inhabited by a thickly constituted religious presence.24

The contrast of thickness in India with the relative thinness of religiosity in the United States and Israel is detectable in the influence of the majority religions in these three places on the social practices of adherents of minority religions. For example, it has often been observed that although the caste system in India is uniquely associated with Hinduism, over a long period of time manifestations of its distinctive hierarchical social ordering have become entrenched in other communal settings, most notably among Muslims (most of whom, to be sure, are descendants of converts). As J. Duncan M. Derrett has pointed out, “[I]n an India which is ruled by a Hindu majority the Hindu concept of religion as a social identification is accepted virtually by all.”25 There is nothing comparable to this in either of the two other countries. In the United States, Christian influence is discernible in the participation by members of other religions in the traditions of Christmas, but this sort of trivial cultural impact only underscores the relative thinness of American religious practice. In Israel too the religion to which most people belong does not constitute a significant presence in the behavior of nonadherents, although this is at least partly attributable to the nonassimilationist ethos of Judaism.

As the point of departure for a preliminary overview of the secular constitutional logics of India, Israel, and the United States, we go first to Australia, specifically to an important Supreme Court decision from that country.

There are those who regard religion as consisting principally in a system of beliefs or statement of doctrine. So viewed religion may be either true or false.Others are more inclined to regard religion as prescribing a code of conduct.So viewed a religion may be good or bad. There are others who pay greater attention to religion as involving some prescribed form of ritual or religious observance.26

The excerpt appears in a decision that is often favorably cited by judges on the Indian Supreme Court (or one of the state Supreme Courts) to illustrate how religion ought to be viewed from a constitutional vantage point. Occasionally, the citation is conjoined with a reference to two wellknown American cases of the late nineteenth century—Reynolds v United States and Davis v Beason—each addressing the problem of polygamy. In all three cases, considerations of social and political welfare were used to uphold restrictions on religious freedom, thus demonstrating that respected authority elsewhere could be cited to support similar efforts in India.27 In addition, the juxtaposition of these cases has enabled the Court to register its preference for the Australian understanding of religion, which, contrary to what the American Court had seemed to be saying in the polygamy cases, does not embrace the distinction between religious opinions and acts done in pursuance of those opinions.

That same Australian opinion speaks contemptuously of “[t]he criminal religions in India,”28 a phrase one should not expect to find in any judgment of the Indian Supreme Court. What one does find, however, are many references to unattractive behavior associated with these religions, and it is in this regard that the distinctions drawn in the excerpt quoted above merit further consideration. As a belief system, religion may be seen as true or false, which is to say it should rightly be construed as a set of opinions to which one subscribes, and is for that reason arguably of no interest to a liberally constituted government. As a code of conduct, however, valuations of goodness or badness come into play, providing a much weaker rationale for government to maintain its indifference to religious activity. Politically, the ultimate source for the derivation of such valuations are the fundamental principles of a given regime. As Montesquieu observed, “The most true and holy doctrines may be attended with the very worst consequences, when they are not connected with the principles of society; and on the contrary, doctrines the most false may be attended with excellent consequences, when contrived so as to be connected with these principles.”29 Montesquieu’s point of course also serves to remind us that beliefs and doctrines (true or false) will have consequences (good or bad), so that distinctions drawn between opinions and conduct are on one level quite meaningless. But on the level of the liberal constitutional playing field, the distinction presumes legitimacy, and Montesquieu’s argument validates certain imposed limits on freedom of religion in order to prevent religiously based conduct from undermining the constitutive principles of society.

Conduct

This at any rate would seem to be the sort of argument that underlies a key provision of the Indian Constitution. Article 25 provides that “Subject to public order, morality and health . . . all persons are equally entitled to freedom of conscience and the right freely to profess, practise and propagate religion.” The second section of the Article goes on to say: “Nothing in this article shall affect the operation of any existing law or prevent the State from making any law—(a) regulating or restricting any economic, financial, political or other secular activity which may be associated with religious practice; (b) providing for social welfare and reform, or the throwing open of Hindu religious institutions of a public character to all classes and sections of Hindus.”

With admirable clarity, then, the document guarantees all Indians a broad right to religious freedom, only to declare that this right is subject to substantial possible limitation.30 Moreover, unlike the other articles in Part III (the “Fundamental Rights” section) of the Constitution, Articles 25 and 26 (providing the freedom to manage religious affairs) begin with a statement of limitations and only then go on to specify the substantive rights that are to be constitutionally guaranteed. It might be an exaggeration to say that this ordering suggests that “[T]he limitations . . . are given the primary place and not the substantive right to which they are appended.” 31 But the textual arrangement evinces a clear founding purpose that seeks to reconcile the securing of religious freedoms included in the document with the achievement of social justice.

The debates surrounding the framing of India’s Constitution support the most obvious interpretation of this language, that the constitutional undertaking of 1947 had as one of its principal goals the major reform of Indian society. Typical of the statements made on this occasion was delegate K. M.Panikar’s comment that “If the State considers that certain religious practices require modification by the will of the people, then there must be power for the State to do it.”32 With this, scholarly opinion concurs. One commentator describes the Constitution as “first and foremost a social document,”33 another as “a charter for the reform of Hinduism.” 34 Consistent with these characterizations are statements from the Supreme Court; for example, the observation by a reform-minded jurist that it should “always be remembered that social justice is the main foundation of the democratic way of life enshrined in the provisions of the Indian Constitution.”35 To reformulate this latter proposition in a way that captures the spirit of Montesquieu’s insight, we might say that the democratic way of life takes precedence over religious practices; that the conformity of these practices to beliefs that are deemed holy and true is no bar to their proscription because of the bad consequences that flow from their failure to connect with the principles of society.36

While this may serve in a preliminary way as an adequate introduction to the secular constitution in India, it also presages difficulties that lie ahead. In a letter published as part of the documentary history of the Constitution’s framing, Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar worried that “[I]f for any reason the Federal Court construes the clause relating to religion and the practice of religion in a wide sense, it may have the effect of invalidating all existing legislation apart from prohibiting such legislation for the future.”37 Were this to happen, the judiciary would be in essence abdicating its prescribed role as “an arm of the social revolution,”38 leaving the transformational agenda of the constitution-makers for others to pursue. For some, the record of the Court’s solicitude for religious practice and autonomy suggests that this abdication has in fact occurred. They refer with disappointment to the “divergence between national aspirations and judicial pronouncements.”39 While this divergence may reflect a failure on the part of some judges to pursue the constitutional path established by founding aspiration, it also reflects an Indian social reality that more or less requires the Supreme Court to reject a narrow view of religion in favor of the Australian model set out in Adelaide Co. of Jehovah’s Witnesses v The Commonwealth.40

Whatever may be the case elsewhere, it would be difficult for an Indian tribunal to do otherwise. Defining religion in the “wide sense” does not occur in a vacuum; it flows from religion-specific characteristics that possess a dynamic and logic of their own. It is one thing to assert the priority of the democratic way of life to religious practice, quite another to act accordingly. Consider, for example, that in the same case in which he wrote of the Constitution’s enthronement of the democratic way of life, Justice Gajendragadkar described Hinduism as constituting “a way of life and nothing more.”41 While surely there is some exaggeration in this claim (“nothing more”?), to the extent that Hinduism does indeed constitute a “way of life,” it renders largely fruitless the task of seeking a narrow definition of religion.42 It also points to one of the great challenges of Indian constitutionalism: how to reconcile two ways of life that are in fundamental tension with one another.43

Indeed, it is difficult to overstate the extent to which the perception of Hinduism as a way of life has dominated commentary and discourse in both scholarly and judicial venues. “People are aware of God in everything”—a “discovery,” according to a 1992 judicial opinion, “that was made in India millennia ago.”44 Thus Bankim Chander Chatterji, regarded by his fellow Bengali writer Nirad C.Chaudhuri as perhaps “the most powerful Indian mind of the nineteenth century,” wrote:

With other peoples, religion is only a part of life; there are things religious, and there are things lay and secular. To the Hindu, his whole life was religion.To other peoples, their relations to God and to the spiritual world are things sharply distinguished from their relations to man and to the temporal world.To the Hindu, his relations to God and his relations to man, his spiritual life and his temporal life are incapable of being so distinguished. They form one compact and harmonious whole, to separate which into component parts is to break the entire fabric. All life to him was religion, and religion never received a name from him, because it never had for him an existence apart from all that had received a name.45

Chaudhuri, whose extraordinary life spanned a century, and who was himself a writer of exquisite insight and eloquence, has described in vivid detail how “in his daily life a Hindu is bound hand and foot in regard to all his actions.”46 His account makes it easy to recognize and appreciate the profound tension that penetrates to the core of Indian constitutionalism, where “The State is secular . . . but the people are not.”

In warning about the consequences of an expansive judicial definition of religion, it could not have been the future Justice Ayyar’s purpose to disabuse his fellow constitution-makers of the tension between secular law and nonsecular lives. Thus in another of his remarks at the Constituent Assembly, he said, “[Y]ou can never separate social life from religious life. . . . [I]f there is one thing which has contributed to the merit of the old Hindu system it is the inter-mixture between religion and the social fabric of society. It is a single society.”47 To be sure, the “merit” of the system is a crucial point of contention upon which much of the debate over the secular constitution rests. The late nineteenth-century Indian social reformer K. T. Telang castigated Hinduism for “preach[ing] not the equality of men but their inequality,” depicting it in a state of “war against the principles of democracy.”48 The war proved difficult to pursue because it was not simply a clash of ideas, but a contest fought, as it were, in the deep trenches of the social order. Moreover, the fact that other wars—of independence, of culture—were and are being prosecuted concurrently means that the battle lines have not always been sharply drawn.

For example, agreement on the existence of a thickly constituted religious presence has not led to anything close to a consensus on an appropriate response to the difficulties this entails. Thus for some, the secular state is “a vacuous word, a phantom concept,”49 but a dangerous construct nevertheless for the perverse consequences that its reckless pursuit entails. Others, who agree that traditional religion in India has for most people been manifest in the totality of their lives, welcome for that very reason a Western-oriented secular state that would bring with it a drastic reduction in the scope and sphere of religion.50 Still others consider an American-like separation of Church and State to be an inadequate response to the problems associated with a pervasive religious presence.For them, “India must give the highest priority to the building of secular counter-institutions in civil society and promoting a more secular popular culture.”51 A secular state is by itself no solution and must be accompanied by the secularization of civil society.

This debate need not be resolved here; at this juncture it is only necessary to establish as a matter of broad, if not universal, general agreement a point whose constitutional significance increases when considered in a comparative context.Within a general framework of sensitivity to the imperatives of group and religious life,52 the formal commitment of the fundamental law “to constitute India,” in the words of the amended Preamble, “into a SOVEREIGN SOCIALIST SECULAR REPUBLIC”,53 represented a substantial challenge to social, cultural, economic, and political practices deeply rooted in the soil of an all-encompassing religious tradition. Thus the observation by Tocqueville that “by the side of every religion is to be found a political opinion, which is connected with it by affinity,”54 requires little elaboration in the Indian context.55 But his application of the insight to the United States scene stimulates reflection over important differences in Indian and American conceptualizations of the secular constitution.

Belief

First, however, it is worth recalling Montesquieu’s point about holy doctrines, societal principles, and the consequences that follow from their consistency or lack thereof. A number of contemporary commentators have followed Tocqueville’s well-known defense of religion in a democracy to adumbrate the salutory effects of inconsistency. The argument relies upon Tocqueville’s understanding of religious groups as independent moral and political forces, and consequently their capacity to function as “a bulwark against state authority.”56 As Stephen Carter puts it, “[R]eligion, properly understood, is a very subversive force.”57 In much the same vein, Robert Booth Fowler welcomes religion as “an alternative to the liberal order, a refuge from our society and its pervasive values.”58 This is not meant as a rejection of those values; subversion, indeed, is to be encouraged in the ultimate interest of those values. Religion’s political contribution to a constitutional democracy comes from appreciating it as “[a] source of public virtue outside of government . . . necessary to the ultimate success of the republican experiment.”59

Carter, Fowler, and McConnell are all scholars who are aligned on the “accommodationist” side of the Church/State debate in the United States.They have worried about the ill effects associated with the secularization of American society. However, the pluralistic arguments they make on behalf of religious liberty are not intellectually bound up with only one side of the debate. In fact, the unstated presumption of their argument for religion as a healthy subversion is more generally associated with the “separationist” advocates on the other side. As part of this presumption, religion in the United States consists of “autonomous intermediate institutions,” 60 which is to say that it constitutes a realm of human experience that is separable from the other realms of a person’s life. It is not, as it arguably is for most people in India, a “way of life.” There are important voices in India—notably Ashis Nandy and T. N. Madan—who speak of religion as a “bulwark against state authority,” but precisely because, in Madan’s words, “religion is here constitutive of society,”61 these voices are the dissonant ones. In the United States, on the other hand, where it makes sense to say (if one is not unduly disturbed by an inelegant redundancy) that the Constitution is constitutive of society, the benefits of religion as an alternative to the liberal order ordained by that document are, as Tocqueville understood, clearly more evident. Here, unlike in India, the Constitution is fully consistent with the dominant political culture and is not itself seeking to reconstitute a way of life, which means that Americans can afford (and perhaps welcome) the challenge of alternative ways of life.62

Such was certainly the case in Wisconsin v Yoder, where the Supreme Court upheld the claim of the Old Order Amish to be exempt from a state’s compulsory school-attendance law. The exceptional treatment of this religious group matched its exceptional profile in American society. In Chief Justice Burger’s account, “[F]or the Old Order Amish, religion is not simply a matter of theocratic belief. . . . [R]eligion pervades and determines virtually their entire way of life. . . .”63 Much that has been written about this case rightly focuses on the exemplary law-abiding and self-sufficient ways of the Amish as crucial in explaining the extraordinary deference accorded them by the Court. But however much the Amish demonstrated old-fashioned American virtues, the Court’s solicitude should also be seen as a reflection of religion’s place in the constitutional order. Thus Burger writes that “A way of life that is odd or even erratic but interferes with no rights or interests of others is not to be condemned because it is different.”64 For most people in the United States, religion is not a way of life; were it otherwise, the rights and interests of others could not so casually be discounted, and the supremacy of the civil law would be dangerously compromised by the kind of accommodation required to adequately acknowledge that reality.

To portray the relative lack of differentiation between religious and secular lives as an essentially aberrant or marginalized phenomenon in American social experience is not to deny the considerable evidence pointing to the religiosity of the American people.65 A contrast with India will suggest that this religiosity does not necessarily entail the totalistic commitment of thick religion, but perhaps more tellingly, so will an examination of the distinctive experience of American Indians. Indeed, some American Indian languages have no word for religion, because, as Stephen Bates correctly notes, “[T]heir concepts of the holy are fully intertwined with life and culture.”66 As is the case for the Amish, the structure of the social world inhabited by these Americans is fundamentally an extension of their spiritual engagements. As told to a Senate committee by one Barney Old Coyote, “Worship is an integral part of the Indian way of life and culture which cannot be separated from the whole. This oneness of Indian life seems to be the basic difference between the Indian and non-Indian of a dominant society.”67

Of what relevance is this to the constitutional provisions of the First Amendment? Unlike its Indian counterpart, the American Constitution uses very few words to address issues of very great complexity. Aside from Article VI’s proscription of religious tests for holding public office, there are, as far as Church and State are concerned, only the familiar opening words of the Bill of Rights: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” For the impartial reader of the voluminous literature concerning the meaning and intentions behind these words, there is likely to be considerable sup-port for Justice White’s claim that “[O]ne cannot seriously believe that the history of the First Amendment furnishes unequivocal answers to many of the fundamental issues of church-state relations.”68 Silently acknowledging that for many other issues such answers can be provided, White does not proceed to engage the problem of how we go about resolving those fundamental questions that resist clear-cut solutions.

For the resolution of at least some of this latter variety, attempting to establish the relative importance of religion as a “constitutive community” could be quite significant. This effort in turn requires looking at the religious question through the Constitution’s broader vision of the meaning of membership in the political community. In an important critique of the liberal view of religion and politics, Michael Sandel has contended that the liberal conception of the person as a free and independent unencumbered self provides inadequate justification for judicial protection of religious liberty. “Protecting religion as a ‘life-style,’ as one among the values that an independent self may have, may miss the role that religion plays in the lives of those for whom the observance of religious duties is a constitutive end, essential to their good and indispensable to their identity.”69 Alternatively, however, one could say that rather than missing this role, the American constitutional solution recognizes the potential role of religion as constitutive of individual identity, and for that reason guards against the possibility of its subverting the common political identity that inheres in membership in the constitutional community. Thus in the case of the Amish, we might welcome the challenge to the dominant political orthodoxy posed by this “holistic, regulative culture,”70 and still worry that accommodating the group’s constitutive needs creates a disturbing precedent for other constitutive needs: those encountered in creating and maintaining a nation. Mary Ann Glendon and Raul F. Yanes, for example, applaud the outcome in this case. “Yoder’s implicit acknowledgment that the religious experience often cannot be separated from the fate of a community—that it may bind the present with the past and the future and play an important role in shaping the character of its members—was an opening to a more capacious approach to free exercise.”71 But the Court’s steady closing of this opening, while a disappointment to Glendon and Yanes, may in the end reflect an appreciation of the constitutional weight attaching to the fate of the wider political community. Thus another take on the problem, one that will be pursued at length in chapters 3 and 8, is that free exercise should not become a passageway to the subordination of national identity to the interests of group identity.

Another group in the United States for whom the observance of religious duties is a constitutive end is composed of followers of Satmar Hasidism, “devoutly religious people who reside in an insular community where religious ritual is scrupulously followed, where Yiddish, rather than English, is frequently spoken, where distinctive dress and appearance are the norm, where television is excluded, and where—in general—children receive their education in private boys’ and girls’ religious schools rather than in secular public schools.”72 In 1989, the New York legislature passed a law constituting the Village of Kiryas Joel (populated almost exclusively by the Satmars) a separate school district, enabling it to establish a school for handicapped children.73 The law was invalidated by the Supreme Court in 1994 as being in violation of the Establishment Clause.Most interesting for our immediate purposes is the vigorous dissent of Justice Scalia, who disputed the majority’s contention that the law had improperly favored a religion in the making of public policy. It was, he maintained, cultural rather than theological distinctiveness that was the basis of the state’s accommodation of the group’s needs. “There [was] no evidence . . . of the legislature’s desire to favor the Satmar religion, as opposed to meeting distinctive secular needs . . . of citizens who happened to be Satmars.”74

Scalia’s resort to culture as a way of saving the program doubtless em-bodied a strategic calculation that, under prevailing Establishment Clause criteria, a majority of the Court would surely find that the state’s action did not possess the requisite “secular legislative purpose.” As part of this calculation, he may have appreciated how difficult it would be to apply such a test in the case of a religion that in fact constituted a way of life for its adherents. He argued that “The neutrality demanded by the Religion Clauses requires the same indulgence towards cultural characteristics that are accompanied by religious belief.”75 He seemed to be in agreement with Sandel’s critique of prevailing constitutional wisdom, to the effect that the Court’s preferred doctrine rested upon a voluntarist justification of neutrality that was non neutral in its liberal conception of the person.76 “It holds that government should be neutral toward religion in order to respect persons as free and independent selves, capable of choosing their religious convictions for themselves.”77 Asking the Court to entertain a broader understanding of religion that incorporated a major cultural component displayed a certain boldness on Scalia’s part, not so much for its challenge to judicial precedent as for its departure from a more familiar and less organic American conceptualization of religion. Had he been successful (only Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice Thomas joined his opinion), he would have put a big dent in one of the basic tenets of separatist constitutional thought in the United States: the requirement that government maintain a posture of strict neutrality between religion and irreligion. It could then have been more forcefully asked whether it was reasonable for government to maintain a position of indifference toward something that is widely perceived as implicating the totality of one’s existence—spiritual and temporal.

Ritual

Of course, if the existence of the State itself were at stake, if, that is, its raison d’etre made no sense without imagining religion at its core, then the question of a constitutive religious presence is basically irrelevant to the constitutional issue of governmental neutrality. Such is the case in Israel, where, unlike in the United States, religion is more than an influence on national identity (present at the creation but in principle distinguishable from it); it is at the core of that identity. Yet very much like the United States, and in this regard quite different from India, religion does not for the most part function as a regulative culture, in which patterns of deeply ingrained social relations are rooted in religious history and tradition.78 To be sure, Judaism is a “total religion,”79 prescribing behavior and practice for all facets of human existence; but most Jews in Israel choose not to place their lives under the regulative jurisdiction of Jewish law. Socially, then, religion manifests a thin presence in Israeli life as a whole, even if politically it may be viewed as thick; for as Daniel Elazar and Janet Aviad have pointed out, “Judaism is constitutive of Jewish identity even for the unbeliever.”80 The result is a regime in which public sup-port for religion is definitional—an insistence that there be no “government entanglement” in religion has an air of unreality about it—but one in which religious liberty is relatively unconstrained by the burdens of social reconstruction.81

This dual commitment, to a public identification with religion and to an official policy of religious freedom for all, reflects the tension that lies at the center of the Israeli experiment in constitutionalism, perhaps most tellingly revealed by the absence of a formal written constitution. While the failure to deliver on the promise of the Declaration of Independence to “a Constitution, to be drawn up by the Constituent Assembly” is a complex multidimensional story, critical to its narration is the difficulty encountered in the effort to reconcile conflicting individualist and communal aspirations. A similar conflict was present at the Indian Constituent Assembly, but as Granville Austin points out, its “members disagreed hardly at all about the ends they sought and only slightly about the means for achieving them.”82 Though communal aspirations would require significant constitutional and, as we shall see, judicial accommodation, a consensus on their necessary subordination (at least for the moment) to liberal, universalist objectives enabled closure on a document.83 In contrast, the Israeli failure in this regard is previewed in the opening lines of the Declaration of Independence, which in effect announce that the legitimacy of the State is ultimately rooted in the chronicle of a particular people. “The land of Israel was the birthplace of the Jewish people. Here their spiritual, religious and national identity was formed. Here they achieved independence and created a culture of national and universal significance.” Here also they committed themselves, as the next section of the document makes clear, to “precepts of liberty,” including the guarantee of “full freedom of conscience, worship, education and culture.” And here they quickly discovered that the translation of these sentiments into an enforceable comprehensive legal document was just too formidable a project to accomplish.84

With this in mind, we should recall the third religious perspective mentioned in the Australian Adelaide opinion. In addition to religion as a system of beliefs, and religion as a code of conduct, “[t]here are others who pay greater attention to religion as involving some prescribed form of ritual or religious observance.” Now, of course, ritual and observance are not severable from belief and conduct, and so to focus on them as if they were disturbs our sense of how things actually work. But in the context of the Zionist experiment in Israel, ritual and observance warrant special attention. As many commentators have noted, the Jewish religion played an instrumental role in the survival of the Jewish people during centuries of statelessness.85 The instinct for survival that developed from this experience was not extinguished with the creation of the Jewish State; rather, it adapted itself to a set of new pressures and responsibilities. It was an adaptation that sought to maximize the integrative potential of the Jewish tradition as the key to developing a strong and vibrant nation.86 Thus as Charles S. Liebman and Eliezer Don-Yehiya conclude in their study of Israeli civil religion, for most Israelis, “religious identity is increasingly expressed in the public domain, and its meaning is increasingly associated with public rather than private life.”87

The famous case of Brother Daniel, the heroic—indeed saintly—Polish Jew who had converted to Catholicism and then applied for citizenship under the terms of the Law of Return, poignantly illustrates what is distinctive about religion in the Israeli political culture. In denying that he was Jewish, the Supreme Court adopted secular reasoning to affirm the common understanding of “the ordinary simple Jew.”88 From this perspective, Brother Daniel, however noble in character, had severed his ties to the Jewish people. “Whether he is religious, non-religious or antireligious, the Jew living in Israel is bound, willingly or unwillingly, by an umbilical cord to historical Judaism from which he draws its language and its idiom, whose festivals are his own to celebrate, and whose great thinkers and spiritual heroes . . . nourish his national pride.”89 Thus Brother Daniel’s fate was sealed in the pages of Jewish history. As Charles Silberman has felicitously observed in another context, “Judaism defines itself not as a voluntary community of faith but as an involuntary community of fate.”90

From all of this flows the significance of ritual and observance. For a nation that is associated with the fate of a particular people, and yet committed to freedom of worship and conscience, the nonreligious and antireligious—who in Israel constitute a clear majority—are, paradoxically, dependent on religion for their political identity. Their stake in sustaining the Jewishness of the State should not be minimized by the absence of an abiding spiritual engagement in their faith. Thus could a distinguished Israeli Supreme Court justice declare in an important case: “There is no Israeli nation separate from the Jewish people.”91 Those accustomed to associating such sentiments with a religious nationalism harboring dangerous extremist ambitions might be surprised to discover that the justice in this case, Shimon Agranat, was a secular Jew widely celebrated for his authorship of landmark libertarian opinions. Another surprise, especially for many secular Jews in the United States, is that the public manifestation of the Zionist commitment is not confined to ritual and symbolism—what might be designated ethnic aspects of Judaism—but also involves matters of religious observance that are prescribed in the Jewish (or halakhic) law.

While there is an obvious political explanation for the official recognition of such religious requirements as kosher food in the military, matrilineal determination of Jewish identity, and bans on public transportation on the Sabbath, the powerful leverage enjoyed by the Orthodox in electoral politics does not entirely account for this phenomenon. Also important is the willingness of the non-Orthodox majority to incorporate parts of Jewish law into the broader legal framework of the polity as a way of encouraging and reinforcing the unity of the Jewish people. To be sure, there is occasionally great resistance to some acts of incorporation when they are perceived as unreasonably burdensome, but most secular Jews in Israel understand the significance of observance to the historical continuity of the Jewish people. They “do not attack religion per se because they define Israel as a Jewish State and this necessarily requires their tacit acceptance of its religious symbols.”92 For the Jewish people “nationalism and religion are inseparably interwoven,”93 which means that for the non-Orthodox majority, the attraction of halakhic rules (in limited doses) is not theological but instrumental, residing in their capacity to serve the ends of the Jewish State by contributing to a concept of national identity that has at its core certain common strands uniting all members of a distinctive people.94

NATIONS AND CONSTITUTIONS

CONCLUSION

An oft-quoted observation by Montesquieu deserves at least one more goaround. “[Laws] should have relation to the degree of liberty which the constitution will bear; to the religion of their inhabitants, to their inclinations, riches, numbers, commerce, manners, and customs.”95 Further on he wrote, “It is the business of the legislature to follow the spirit of the nation, when it is not contrary to the principles of government; for we do nothing so well as when we act with freedom, and follow the bent of our national genius.”96 As we continue to consider these three models of secular constitutional design, it is important to follow the tenor of these observations. Thus “the spirit of the laws” expresses itself in contrasting constitutional approaches to Church/State relations that reflect, either directly or through designed confrontation, distinctive regime-defining at-tributes of nationhood. As explored more fully in the next chapter, an assimilative model manifests the ultimately decisive role of political principles in the development of the American nation, a visionary model seeks to accommodate the particularistic aspirations of Jewish nationalism in Israel within a constitutional framework of liberal democracy, and an ameliorative model embraces the social reform impulse of Indian nationalism in the context of the nation’s deeply rooted religious diversity and stratification.

In each case, “the degree of [religious] liberty which the constitution will bear” reflects, in part, “the religion of the inhabitants,” understood in functional rather than theological terms. For the inhabitants of India, the imprint of religion is deeply etched in the patterns of daily life, such that social structure and religious activity are indissolubly linked. For the inhabitants of Israel, religious affiliation is imbued with a political meaning that ultimately determines membership in the larger governing community. And for the inhabitants of the United States, religion is an essentially voluntary activity that pervades the domain of private life, providing active as well as passive support for a shared public theology. In all three countries, religious liberty is a principal, if heavily contextualized, goal of constitutional interpretation, differently provided for in each instance to mirror the sociopolitical conditions of the respective local setting. So Justice Douglas could say of Article 25 of the Indian Constitution, “[I]t may be a desirable provision. But when the Court adds it to our First Amendment, . . . we make a sharp break with the American ideal of religious liberty as enshrined in the First Amendment.”97 To this assertion he could add with confidence that “The First Amendment commands government to have no interest in theology or ritual.”98 Yet perhaps more so than any other modern justice of the Supreme Court, he, as a student of comparative law, understood that the authority behind constitutional commands depends as much upon the nuances of political culture as it does the language of the Constitution or the commitment of its designated interpreters.

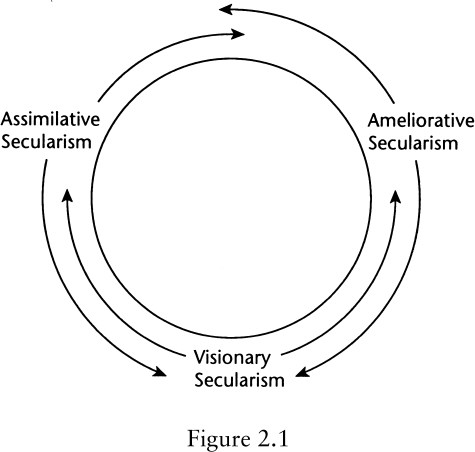

However, the comparative perspective’s accentuation of distinctive models of constitutional ordering must not be allowed to obscure the shared and overlapping features of contrasting national experiences. Constitutional classifications are usually not sharply isolable, but present themselves along a continuous sequence or range. Whatever utility may be found in our fourfold table will be quickly negated if its typology creates a presumption of categorical exclusivity. Montesquieu’s advice to governments, that they should follow “the spirit of the nation” and the “bent of [their] national genius,” leaves his advisees with considerable maneuver-ability; spirit and genius as applied to nations are never unidimensional. Within our models of the secular constitution are internal tensions and contradictions offering alternative developmental possibilities whose potential is, at least theoretically, to culminate in convergence of the three nations’ constitutional experiences.

For example, Israeli judges seeking to advance the more liberal strand of Zionist aspirations may end up shifting the focus of the secular constitution in the direction of an assimilative model. Also, to the extent that the Jewish national movement’s historic roots can be traced to rebellion against traditional Judaism,99 Zionism’s political realization through the medium of the Israeli State may be seen to embrace an ameliorative dimension of no small consequence. Similarly, as I will argue in chapter 9, a more concerted effort by American judges to assist minority religions whose religious practices were thought to be threatened by an insensitive majority would provide a more ameliorative tone to the American secular solution. Were this consistently to occur, sentiments expressed in Indian judicial opinions that are generally taken to be emblematic of a distinctive national orientation would become less helpful in demarcating the boundaries between Indian and American Church/State jurisprudence. As one example: “It may sound paradoxical but it is nevertheless true that minorities can be protected not only if they have equality but also, in certain circumstances, differential treatment.”100 Considerably less likely, but nevertheless imaginable, is a United States Supreme Court citing historical precedent for the proposition that the character of the American people has been singularly shaped by a particular religious tradition, and that this experience justifies special official recognition. The result would provide a more visionary slant to the American secular constitution. No longer would an observation such as the following by Justice Brennan serve to distinguish very well the American and Israeli situations: “Under our constitutional scheme, the role of safeguarding our ‘religious heritage’ and of promoting religious beliefs is reserved as the exclusive prerogative of our Nation’s churches, religious institutions, and spiritual leaders.”101

Table 2.1, then, needs to be supplemented to indicate the spectral as well as typological features of constitutional comparisons.

Perhaps the best way to explain this representation is to point out something that doubtless has by this time occurred to the patient reader, namely that the depiction of nationhood or national identity is not an exact science. It does not, however, detract from the value of such analytical depictions to acknowledge that distinctive attributes of nationhood are neither exhaustive in their descriptive power nor associated exclusively with the particular nations for which they have definitional signifi-

cance. Political assimilation, social amelioration, and communal vision provide the animating force behind the respective secular constitutions of the United States, India, and Israel, but in each case these directive principles are also background presences—varying in their prominence—in the two polities where they are not featured. The historical experiences of all three societies are layered in multiple meanings, such that the shaping of national identity remains an ongoing process within which religion’s place in the constitutional order is never unalterably fixed. As suggested by the arrows surrounding the circle upon which the constitutional mod-els are located, the distinctiveness of a particular approach to Church/ State relations is subject to dilution or obfuscation, as forces within the larger society exert pressures that pull a specific model in one direction or another.

In this context, comparative analysis has much to offer, for unless one subscribes to the view that these forces evade human channeling and control, the constitutional experience of one nation can have a decisive effect on the evolution of constitutional secularism in another.102 As Michael Walzer has observed in relation to regimes of toleration, “If this or that aspect of an arrangement there seems likely to be useful here, with suitable modifications, we can work for a reform of that sort, aiming at what is best for us given the groups we value and the individuals we are.”103 Those Americans favorably disposed to a revival of cultural nationalism would do well to explore the implications of ethnorepublicanism or religiorepublicanism in Israel; while others inspired by prospects of ecumenical harmony might wish to consider the tradeoffs spawned by India’s legitimation of group rights. For Israelis who wish to pursue with single-minded resolve the logic of their Declaration’s liberal aspirations, the American subordination of religion and its attendant denominational neutrality could prove instructive, as could, as we shall soon see, the am-bivalent Indian constitutional commitment to a uniform civil code for Israelis contemplating greater religious autonomy in matters of personal status. Finally, Indians determined to place greater distance between the State and activities related to spiritual fulfillment should pause to reflect upon the antiredistributive social implications of the American wall of separation,104 just as other Indians with their sights set upon a greater separation of another kind—that which divides religious communities—should ponder the politics of religious segmentation practiced in Israel.The results of such reflections may be used in support of change or in justification of the status quo. To whatever purpose they are put, they may help to resolve the issue raised at the outset of a notable contribution to comparative constitutional analysis, The Federalist, of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice.”105

1 Karunakaran 1965, 195.

2 Or as Justice V. R. Krishna Iyer wrote, “The secularizing and socializing influences of the constitutional philosophy, which aims at rendering caste and religious beliefs dysfunctional to social relationships productive of legal consequences, have not as yet produced the liberalising thrust at the grass roots level which they were expected to engender.” Iyer 1984, 156.

3 Minerva Mills Ltd. at 1846.

4 For example, the Church of England, which, particularly in the nineteenth century, used its considerable power to block meaningful reform.

5 Madan 1997, 235.

6 See, for example, Walker 1994, 504, 510.

7 At the outset we should be careful in distinguishing between political and constitutional cultures. As we shall see, and as the case of India best illustrates, a constitutional ethos or culture may emerge from a specific political culture expressly in order to modify or trans-form it. Mark Tushnet uses the term expressivism to denote a school of thought in comparative constitutionalism in which constitutions are seen as expressive of a nation’s distinctive history and culture. He rightly points out that “[N]ations vary widely in the degree to which their written constitutions are organically connected to the nation’s sense of itself.” He is also correct in suggesting that the Indian Constitution is in a certain sense a confrontation with a society organized in accordance with principles opposite those embodied in the document. This leads him to conclude that unlike the American constitutional scene, the Indian Constitution (and its interpretation by the courts) tells a much less clear story about who that nation is. Here I would disagree, since the confrontation between constitution and society turns out to be enormously revealing of what is distinctive about Indian politics and culture. A confrontational constitution can be as expressive of a political culture as a document such as the American, which is a more seamless extension of its political environment. Tushnet 1999, 1270–71.

8 A notable exception was Justice William O. Douglas, who was especially interested in India. Douglas wrote a book (based on his Tagore Lectures) about the Indian constitutional system. Douglas 1956. More important, his reflections on the Indian constitutional approach to Church and State figured prominently in several of his judicial opinions (e.g., McGowan; Seeger; Sherbert). Douglas was a sympathetic observer of the Indian experience. At the same time, he used it to highlight some of the distinctive and desirable characteristics of the American approach.

9 Tocqueville 1945, vol. 2, 28.

10 Fletcher 1993, 737.

11 Aristotle 1962, 1288b 10.

12 Walzer 1997, 2–3.Walzer proceeds “to defend . . . a historical and contextual account of toleration and coexistence, one that examines the different forms that these have actually taken and the norms of everyday life appropriate to each.” He continues: “It is necessary to look both at the ideal versions of these practical arrangements and at their characteristic, historically documented distortions.”

13 Ibid., 4. A good example ofWalzer’s point may be found in the Indian practice of State support for public events of a religiously celebratory nature. As Rajeev Dhavan has ob-served, “This is where Indian secularism is vastly different from American or any other kind of secularism.” Rajeev Dhavan, “The Kumbh,” The Hindu, February 26, 2001. India, he points out, practices a “participatory benign neutrality,” rather than a “strict neutrality” of the sort that makes it exceedingly difficult in the United States for public resources to be expended for even small cre`che displays at the Christmas season. On the other hand, sup-port for mega events such as the Kumbh (a Hindu ceremonial gathering attended by mil-lions) is accepted as necessary for a healthy secularism in which the infrastructure of religious diversity is kept viable through direct governmental engagement.

14 Monsma and Soper 1997, 202.

15 Aristotle 1962, 1288b 10.

16 Smith, 1970, 11. There is a substantial literature on secularization. A good sampling may be found in Bruce 1992. In their depiction of the orthodox model, Roy Wallis and Steve Bruce explain the phenomenon as occurring when “[r]eligion becomes privatized and is pushed to the margins and interstices of the social order.” Ibid., 11. Or as Peter Berger has described it, “[T]he process by which sectors of society and culture are removed from the domination of religious institutions and symbols.” Berger 1969, 107.

17 Bhargava 1998, 489. A different view has been expressed by another Indian scholar, Achin Vanaik, who sees such a development as quite desirable. “Further secularization means the further decline of religious identity. This is both possible and desirable. Religion should become more privatized and religious affiliation more of an optional choice.” Vanaik 1997, 70.

18 As Charles Taylor points out, the term secular was originally part of the Christian vocabulary, which serves as a useful reminder that liberalism fits most comfortably with certain kinds of religious experience. Taylor et al. 1992, 62. In this regard, Marc Galanter, the leading American student of Indian law, writes of the First Amendment that it is a charter for religion as well as for government. “It is the basis of a regime which is congenial to those religions which favor private and voluntary observance rather than to those which favor official support of observance.” Galanter 1989, 249. There is also another kind of separation that should be minimized for our purposes. Harvey Cox’s definition of secularization involves, in addition to liberation from “religious and metaphysical tutelage, the turning of [man’s] attention away from other worlds and toward this one.” Cox 1990, 15. But as Tocqueville suggests, a democratically constituted regime can be undermined by an exclusive focus on this-worldly concerns.

19 Way and Burt 1983, 654.

20 Margalit and Raz 1995, 82. See also Rosenblum 2000. Rosenblum uses the term integralism to convey a similar idea. “Its defining characteristic is a push for a ‘religiously integrated existence.’ . . . Integralists want to be able to conduct themselves according to the injunctions of religious law and authority in every sphere of everyday life, and to see their faith mirrored in public life.” Ibid., 15.

21 As broad as my working definition of the secular constitution is, it cannot accommodate a regime—I have in mind a country such as Iran—where the State identifies strongly with a religion that is constitutive of society. A recent visitor to the United States from Iran, Mohammad Atrianfar, the head of Teheran’s town councils and editor of the daily newspaper Hamshahri, remarked: “What surprised me the most when I came to the United States was how many churches there were. I certainly didn’t know how religious Americans are.” New York Times, Week in Review, September 23, 2001, 8. Had he reflected further, he might have noted that being “religious” can mean quite different things from place to place in terms of social and political impact. Indeed, when Tocqueville first arrived in the United States, he had a similar reaction to the Iranian’s. “On my arrival in the United States the religious aspect of the country was the first thing that struck my attention; and the longer I stayed there, the more I perceived the great political consequences resulting from this new state of things.” Tocqueville 1945, vol. 1, 319. He then went on to comment on the absence of a religious presence in the circles of American government, which led to an observation that causes one to think of contemporary Iran. “Religions intimately united with the governments of the earth have been known to exercise sovereign power founded on terror and faith.” Ibid., 321.

22 There is a great temptation to deny Israel the status of a secular regime. See, for example, Tessler 1981, 247. As I will explain, however, one should resist this temptation, even while conceding that Israeli policies discriminate against non-Jews. For another perspective that employs an alternative typology constructed along the dimensions of state establishment and religious participation in electoral politics, see Demarath 2001. One of Demarath’s categories is Religious States and Religious Politics, a “stereotypically non-Western” type, under which he places Israel. Ibid., 194–5. Such a placement is defensible (although as Demarath recognizes, controversial), but the absence in this typology of a thickness/ thinness dimension may lead one erroneously to locate Israel among a group of non-Western regimes that are hostile or indifferent to the protection of religious liberty.

23 The thinness of American religiosity is partially explained in theological terms. AsWarren A. Nord has observed, “Many Americans believe that believing is enough.” Nord 1995, 41. Thus Nord notes that Protestantism made doctrine and belief, rather than good works and religious practices, critical to religion. The contrast with Catholicism, Islam, Judaism, and Hinduism is not without political significance.

24 See Dumont 1970, 210; Derrett 1968, 558; Galanter 1984, 17; and De 1976, 105.

25 Derrett 1968, 558. As a result, although the Muslim and Christian faiths specifically reject the notion of caste, in India both communities recognize caste within themselves.

26 Adelaide Co. of Jehovah’s Witnesses at 123.

27 In the Australian case, the Parliament had legislated to restrain the activities of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, activities that it felt were prejudicial to the efficient prosecution of the war. The Court upheld these restrictions, while conceding that the religious group had not engaged in any overt hostile acts. For the restrictions to be upheld, it was deemed sufficient that the Witnesses possessed an attitude of noncooperation with the war effort, coupled with beliefs that all governments were “satanic.” It is perhaps worth noting that in the same year across the ocean, the Jehovah’s Witnesses were faring much better, as the American Supreme Court upheld their right to refrain from participating in a public school flag salute. West Virginia v Barnett. The Reynolds and Beason cases, involving the efforts of the United States to curtail the activities of the Mormons in Utah, are discussed more fully in the next chapter. For a critical account of Adelaide that views the decision as sending a message that the Court would not be a strong advocate of religious freedom, see Monsma and Soper 1997, 96–7.

28 Adelaide at 125.

29 Montesquieu 1966, vol. 2, 38–9.

30 Indeed, the leading authority on law and religion in India, J. Duncan M. Derrett, notes that the Article is “subject to so many qualifications and restrictions that the reader wonders whether the socalled ‘fundamental right’ was worth asserting in the first place.” Derrett 1968, 451. There are additional rights present in this section that relate to religion, such as the freedom of religious institutions to manage their own affairs and the freedom to avoid being taxed for the promotion or maintenance of any particular religion or religious denomination. Part IV of the Constitution—the “Directive Principles of State Policy”—also contains passages implicating religious freedoms, but the articles in this section of the document are essentially hortatory in nature, meaning that they are not justiciable in Court. As will be shown later, this does not mean they are unimportant.

31 Beg 1979, 36.

32 Government of India Press 1967, vol. 2, 265.

33 Austin 1966, 50.

34 Galanter 1989, 247.

35 Justice Gajendragadkar in Yagnapurushdasji at 522.

36 Note, for example, the concern for the thickness of religion in this debater’s comments on Article 44, the section in the Constitution concerning a uniform civil code. “We are at a stage where we must unify and consolidate the nation by every means without interfering with religious practices. If, however, the religious practices in the past have been so construed as to cover the whole field of life, we have reached a point where we must . . . say that the matters are not religious, they are purely matters for secular legislation.” Quoted in Baird 1981, 423 (emphasis added).

37 Government of India Press 1967, vol. 2, 143.

38 Austin 1966, 164.

39 R. K. Tripathi as quoted in Beg 1979, 49. Gurpreet Mahajan contends that the Court’s solicitude has given it the appearance of being a bastion of social conservatism. Her claim, contrary to the argument in this chapter, is that this conservatism is consistent with the transcendent emphasis in the Constitution on religious pluralism. “[T]he primacy accorded to religious practice by the Constitution and the Supreme Court has severely limited the modernizing interventions of the Indian State.” Mahajan 1998, 72.