5

Sharing Care

Emperor Penguins

Whoosh, whoosh . . . whoosh, whoosh . . . whoosh, whoosh . . . this was his world, his entire being. Then, suddenly, there was an abrupt change. Instead of being the sound, he became witness to the sound—the sound of his mother’s heartbeat. He felt a strange sensation, a feeling of falling away from the whoosh, whoosh. There were whispers of voices, movement, and a more distant, different whoosh, whoosh began, fainter, with a slightly faster pace. This was his father. The egg had left his mother to live in the enfoldment of his father’s feathered warmth. The egg was home; a different home, but home.

As the Earth’s northern pole tilts toward the sun, Russian Brown Bear bodies begin to quicken. It is time to leave the hibernation nest and reenter the world beyond. As they push through spring’s melting snow, other communities, those to the far south, are pulling into warmth. Antarctic waters have returned to “fast ice”—sea ice that “fastens” to the land. While Antarctica enjoys its temporarily expanded land base, Emperor Penguins begin to gather. Every fall, thousands of these flightless Birds gather in the ceremony of making a family.

Their pilgrimage is extraordinary. Standing four feet tall, flippers at their sides, Emperor Penguins march up to sixty miles (almost one hundred kilometers) over the ice to rendezvous where Penguins have gathered for generations. At times, their purposeful stride shifts to tobogganing as they drop to the ice and, propelled by flippers and legs, continue their journey. It is an ardent and arduous trek.

When they finally arrive at the communal space, new couples meet, and partnered pairs renew their vows. March and April is courtship time, called pariad. Air and ice resonate with songs, calls, and elaborate dances of flashing black, white, and yellow plumage. Facing one another, the pair makes a deep bow proclaiming love, commitment, and intention. After making or renewing their vows, relationships are cemented with consummation, and about a month later, the female Penguin lays a single beautiful egg.1 But much happens well before that event. Just as their parents journeyed over ice, incipient Penguins make an equally demanding voyage before entering the open world—one that starts inside their mothers.

When a female’s follicle reaches maturity, it is released down her reproductive tract. The ovum is mostly yolk, the rich foodstuff that will sustain the embryo until hatching. After Penguin lovemaking, the soon-to-be father’s sperm swims up the tract in search of the egg. When sperm and ovum make contact, respective gene halves join, and a new Penguin is conceived.

Contracting muscles of the mother Penguin’s reproductive tract move the fertilized egg along. Spiral ridges rotate the egg to create an evenly coated cover of albumin. As the spinning egg floats on its way, spiderweb strands of albumin bind the delicate egg with protective membranes. This clear, sticky substance hydrates the egg, provides it with protein, and shields it against infection. However, at this point the process of egg-making is far from complete. The embryo still needs a shell.

Over the preceding months, mother Penguin has stored extra calcium in her bone cavities, which is now carried to the soft egg to surround it. Bit by bit, calcium precipitates and grows into a fully formed shell. As a final sealing touch, a layer of waterproof cuticle is laid down. The eggshell, however, is not completely sealed off. It contains thousands of pores that allow the embryo to breathe, taking in oxygen and exhaling carbon dioxide and water.2 Finally, the embryo in his world-of-his-own egg is ready to step off the internal reproductive conveyor belt. The embryo will continue to grow for a total of approximately sixty days.

When the momentous day arrives, the egg emerges. This is no time to dawdle. Antarctic temperatures plummet as low as –40°F (–40°C), and wind speeds have been recorded reaching 199 miles per hour (327 km/hr). The lowest recorded temperature on the planet was measured in the Antarctic at –129°F (–89°C). The egg is well protected, but it cannot withstand this cold.3 Emperor Penguins are the only species to birth in the Antarctic winter, but they have evolved nest practices that outwit these extremes and nurture their young in safety.4

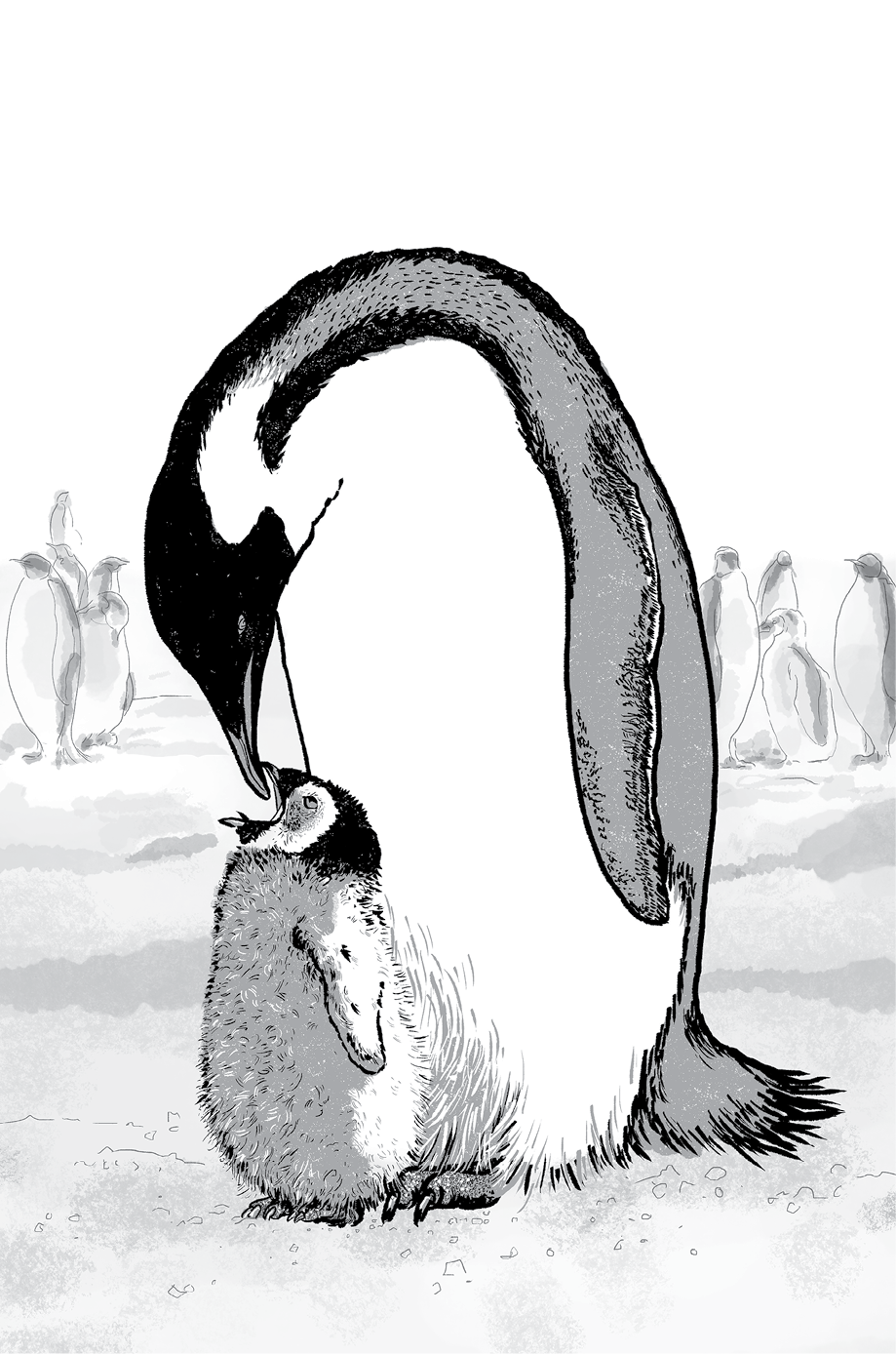

Adélie Penguins and Gentoo Penguins build more classical nests fashioned from stones and Grass. In contrast, Emperor Penguins come with their own built-in nests. As soon as the egg emerges from the mother Penguin, it slides off her feet and onto those of the receiving father, who brings the egg into a feathered den just above his feet. The brood pouch, or skinfold, has feathers in front and highly vascularized skin in back.5 Nestled next to the father Penguin’s bare skin, the beautiful white-gray egg is kept at a perfect incubating temperature between 98.6°F and 100.4°F (37°C and 38°C).6

However, this initial shared event is short lived. Once the family treasure passes from one parent to the other, the mother leaves. She is depleted. Her internal resources have been directed to creating and nourishing the egg and embryo, so by mid-May new mothers depart from their nuclear family. One can imagine that departing mother Penguins have mixed feelings: on the one hand, reluctance to leave their nascent child and partner; on the other, a certain relief and eagerness for replenishment at sea. Penguin females spend the next two-plus months in the ocean recuperating. Emperor Penguins are models of self-care: caring for oneself means being able to care well for one’s young.

Penguin food is largely pelagic, meaning it comes from the open sea, where calorie-rich Antarctic Silverfish (also known as Antarctic Herring), Lantern Fish, Krill, and Squid live. Antarctic Silverfish are members of the Actinopterygii, or the “ray-finned” class of Fish, that comprises more than half of all vertebrates and the majority of Fish species consumed by Emperor Penguins (89 percent).7 Silverfish are actually pink, and at only a few inches long, they are small enough for rapid consumption. They make perfect food for hungry Penguins.

Emperor Penguins dive to great depths to retrieve their meals in a single held breath. The deepest Penguin dive recorded is 1,850 feet (564 meters),8 and the longest recorded dive lasted 1,932 seconds, or just over thirty-two minutes.9 André Ancel, an eminent scientist at France’s Centre national de la recherche scientifique who has studied Emperor Penguins for decades, explains that the Birds use this food-diving strategy: “If a Penguin needs some stones which they use to grind up and digest food, they dive to the sea bottom. On the way to the sea surface, the water lightens to blue. Emperor Penguins see Fish and Squid as dark objects because they ‘cut’ the light from the sea surface, seeing the outline as such, which is why biologists refer to the outline as a ‘Chinese shadow’”—named so after paper puppets used in traditional shadow plays.10

At the end of their sojourn, fattened and strengthened, mother Penguins retrace their steps back over the ice to rejoin their families. Mother Penguins must have a very accurate sense of time tuned to their babies because they usually arrive within a handful of days before or after the egg has hatched. Father Penguins have not been idle during their partners’ absence. While mothers are revitalizing, Emperor Penguin fathers are tending to their priceless charges, each father regularly rotating his egg to make sure the embryo within is kept evenly warm.

Two months after hatching, Emperor Penguin infants have only a light covering of downy feathers, so they are quite vulnerable to the cold. They remain in their fathers’ pouches where they are fed with his crop milk, an easily digested baby food of ricotta-cheese consistency made from the lining of the father Penguin’s esophagus. Understandably, crop milk is high in both fat (30–36 percent) and protein (60 percent). Similar to the stimulation of human breast milk production, crop milk is produced when prolactin levels rise, which occurs during female brooding and male egg incubation.11

There is still much more to the Emperor Penguin evolved nest. Although Penguins’ fat and thick feathers—which provide 85 percent of their total insulation12—may provide critical protection, they are not sufficient. To compensate for the cold during the father Penguin’s two months of solitary parenting, which intensifies as winter deepens, father Penguins coordinate with each other in collective allocare.13 Fathers gather to form huddles of varying sizes and densities depending on the weather.14 Huddles act as a social thermoregulation mechanism that helps conserve and regulate heat. Every so often, groups coalesce or break up in response to wind conditions, solar radiation intensity, and ambient temperature. Although environmental temperatures are frigid, heat generated by the collection of Penguin bodies can raise temperatures within the huddle to 100°F (38°C). Huddle reorganization serves to cool off those who are getting overheated and warm those who are getting too cold.15 Penguin huddle dynamics is a beautiful example of how individuals cooperate and coordinate within a larger community to provide seamless social and ecological connection and security for their children.16

By the time female Penguins return and meet their new chicks, father Penguins have fasted for four months and have lost almost half their weight. The colony atmosphere is taut with expectation and anxiety. Tragically, not every chick will have survived, but when reunion occurs, there is much to celebrate. Connecting, however, is not always easy to accomplish. Penguin colonies can number in the thousands.17 To make their way through the melée, each couple uses their own distinctive call, which their chick learns on the spot. In contrast to other Penguins, who hold their beaks high with outstretched necks, Emperor Penguin heads and beaks arc downward to make their calls.18 Somehow, despite the chaos of the crowd, this posture transmits calls and brings the various threesomes together. Penguins are very mindful of others’ needs. To avoid any “cross-chat” that might hamper another’s ability to find their family, they observe the “courtesy rule.”19 If a Penguin sees that their neighbor is about to call out to their mate, the Penguin politely waits until the “line” is free. Dolphin mothers conform to a similar conversational rule. Two weeks before and after birth, each mother provides a signature whistle that baby is expected to and does learn. Other members of the pod refrain from whistling their own names during this period to avoid confusing the young.20

After reunion, mother Penguins take over infant care. It is now the fathers’ turn to replenish. Although fathers are in great need of food, some show hesitation to hand their babies over to the mothers.21 Eventually, after dragging their feet a bit, male Penguins do what their spouses have done: begin the pack ice journey to the ocean, where they will dive into the waters to enjoy marine repasts. When a compressed month of eating is completed, father Penguins return.

At the point when baby Penguins have gained enough weight and feathers, the community transforms into a crèche where young Penguins engage with others of their own age. During this period, parents take alternating trips to the ocean to maintain health. Any feeding gaps are bridged by alloparenting.22 By the end of November, when it is summer in the Antarctic, the babies molt, replacing fluff with shiny waterproofing feathers. The young Birds, however, remain very dependent on their parents until late December or early January, when they become big and strong enough to make the seaward trek together with the rest of the Penguin community.

As joyful and adventuresome as the march to water is, young Penguins are on a steep learning curve. It is a long journey from life inside an egg to being a full-fledged adult Penguin. During the trip and at the ocean, the young continue their socioemotional and physical lessons. Not only must they learn how to find and catch Fish, Squid, and Krill; they are also acquiring details about their homeplace and society. Maturation involves more than passing physiological milestones and accumulating knowledge. Sensory phenomena, whether it is internally or externally derived, must be processed and understood in the context of self and society. A “mature” Penguin is mature in more than years. They are the process and product of their experience, ancestors, and environment. Maintaining congruence in time (lineage) and space (social and ecological environs) is integral to evolved nesting. While their evolved nest design differs from those of other species, Penguin care reflects the principles, practices, and patterns of nurturance embraced by Nature-based humans and nonhumans around the world, many elements of which were brought to the fore in modern society through the work of John Bowlby.

Bowlby was an English clinical psychologist born in 1907. His work—resonant with the work of others such as New York psychologist William Goldfarb,23 Bellevue Hospital pediatrician Harry Bakwin,24 and Viennese psychoanalyst René Spitz (responsible for identifying and documenting hospitalism, the wasting away and deaths of formerly healthy children in hospital care)25—would significantly influence Western human developmental sciences for years to come. Bowlby sought a new theory to explain the effects of maternal deprivation, the foundation of which would lead to what he called attachment theory.26

Prior to Bowlby and similar thinkers, such as Pierre Janet and Mary Ainsworth, the reigning theories of child development were psychoanalysis and behaviorism. According to the proponents of these two schools of thought, children needed nothing more than good physical nourishment and shelter. In contrast, Bowlby made visible what had been overlooked: how early relationships shape developmental health and mental well-being.27 He drew attention to the critical role of early-life relationships beyond food and protection.28

Attachment is considered key in setting an infant onto a specific path of social development that persists through the entire trajectory of life experience.29 In this framing, carer-child relationships extend beyond an elemental carer behavior control system, proximity or protective caregiving, in which parents maintain proximity through retrieval during immaturity, to include a safety caregiving system30 that orients the carer to the needs of the child.31 Through processes of attachment to the carer, an infant internalizes their social experiences, creating an internal working model of social relations—that is, embodied social conceptualizations that are applied ever after.32 Caregiving and attachment systems are evolutionary prepared mechanisms that recruit the child and carer into a maturational process of socialization and building trust.33 The evolved nest deepens and expands upon this idea by emphasizing companionship attachment34 as a Nature-based environment that fosters holistic child development through spontaneous, attentive interactions with human and nonhuman relations, enabling full membership in the Earth community.

Bowlby’s insights into child raising implicitly interfaced with social and cultural patterns. He was enlisted by the World Health Organization to address children who had been separated from their families in the wake of World War II. His interest in maternal separation had first arisen during his work with maladjusted children. The English psychologist found that even well-fed institutionalized children fared poorly relative to their counterparts who lived with their families. Despite receiving proper shelter and nourishment, institutionalized children exhibited profound depression, anxiety, and unstable personalities. With prolonged separation and repeated loss of replacement mother figures, children were prone to becoming self-centered, materialistic, and socially detached.35

Bowlby was sympathetic to their plight because of his own childhood experiences. Although he came from a wealthy family and was afforded plenty of food and comfortable shelter, Bowlby rarely saw his parents. He spent an hour or so with his mother each day, and he only saw his father a few times a year—they left his care largely to nannies. In instances such as Bowlby’s, nannies or childminders are often the only possible source of emotional nurturance and dependable love that a child receives. In this capacity, a childminder can save a child from complete unmooring. But at the same time, as Bowlby experienced himself, these relationships can be quite fragile and significantly destabilizing to a tender young psyche. For example, a nanny with whom Bowlby formed a deep attachment left when he was four. As many scholars have noted,36 human nannies and childcare centers may end up functioning, intentionally or not, as a culture of cruelty, because they are bound to prioritize what a parent or institution wants over the natural needs of a child. Even if they seek to provide attentive care for their charges, childminders such as Bowlby’s nannies can be vulnerable to their employers’ whims and values.

At seven, Bowlby experienced yet another relational rupture when he was sent to a British boarding school,37 which he later described as “the time-honoured barbarism required to produce English gentlemen.”38 Since Bowlby’s time, others have recognized associated and resultant symptoms now referred to as “boarding school syndrome.”39 Indeed, boarding schools and other institutions were deliberately designed by colonizers to control children and impose outside values and standards—with disastrous consequences.

Countless Indigenous people have been subjected to forced Western-style physically and psychologically abusive education and economic systems that have destroyed entire families, communities, and cultures, thus tearing apart the delicate web of ancient wisdom traditions. Commenting on the results of this education-driven culturicide, anthropologist Wade Davis identifies two great myths that have obfuscated the reality of imposed education:

We promote Western education around the world as if landing in a void, as if people around the world did not educate their children. Well, of course they did, in complex, sophisticated ways, whether it was 2,500 years of empirical observations as to the nature of the mind in Tibetan Buddhism, the nocturnal studies of the elder brother who literally believed that their prayers maintain the cosmic balance of the world, in textile traditions of Peru and throughout the South Pacific. The other great myth is that somehow education lifts people out of poverty. I have never in all my time in traditional cultures seen the wretchedness that one encounters around the periphery of almost any city in the so-called third world. In the end we have to ask ourselves: What is this thing of Western education?40

When the critical psychophysiological bridge from the inner world of the womb to social support and meaning-making communal processes collapses, a child is subjected to damaging relational rupture and, as happened to Schmetty, the young Elephant, a broken heart. However, early trauma can be mitigated in many cases if, as the orphaned Elephant infants at the Sheldrick Trust illustrate, evolved nest practices and experiences are reinstated and embedded in a community of holistic life values and supportive culture.

The difference between the children whom Bowlby met and the orphans rescued by the Sheldrick Trust is that the Elephants are provided with a caregiving experience that emulates their natural, natal family evolved nest. The work at the Trust is regarded as reparative, furnishing the orphans with a protofamily as a replacement for the family who was taken away, and treating the infant’s inner and outer wounds of trauma. The Sheldrick Trust serves as a healing bridge to traditional Elephant culture and the Elephant evolved nest. Not only do Elephant values and ethics imbue orphan care, but their Elephant carers never leave. Only when infant Elephants are mature enough to move from the nursery to an intermediate space and then eventually join a wild herd does separation occur. This transition is in keeping with natural processes and structures of Elephant development and society. The Sheldrick Trust has replaced human violence with a cross-species community who will always be there and available when needed. Absent reparative nest care, as was the case for the Rhinoceros-killing Elephants, a child is left wounded and unmoored.

In parallel human situations, most modern children who have experienced relational rupture via orphaning, relinquishment, family separation, neglect, or abuse (referred to as relational trauma) do not receive reparative care. Unlike healthy Elephant society and the reparative society crafted by the Sheldrick Trust, industrialized human culture generally lacks the wherewithal, will, or holistic orientation to child raising that could otherwise fill in and stabilize change, as occurs in Nature-based societies. In lieu of holistic support of body-mind-spirit,41 modern-day educational facilities tend to emphasize detachment and disconnection through a focus on intellectual knowledge.42

The modern, conventional emphasis on obedience, reading, and “factual” knowledge derails holistic development.43 Forcing young children into school-like learning, which usually entails a focus on alphabets, numbers, and reading, pushes the child away from the right hemisphere and into left hemisphere functioning too soon, which undermines the development of Earthcentric practical intelligence and a holistic receptive intelligence.44 Tyson Yunkaporta, of Australian Indigenous heritage, identifies these holistic ways of Indigenous thinking that are often missing in unnested individuals and cultures: kinship-mind (relationally connected mind), story-mind (a method for remembering ancient knowledge), dreaming-mind (using metaphors to link abstraction with concrete experience), ancestor-mind (deep engagement in timeless reality), and pattern-mind (perception of the meaning of systems of patterns).45

The Western emphasis on factual knowledge, in contrast to embodied know-how, leads dominant-culture achievers to think they know the answers to life based solely on abstract models46 or lab experiments.47 Too often, modern schooling teaches cleverness, cunningness, and habits of drawing conclusions without relying on experience. Alternatively, “knowledge in the traditional world is not a dead collection of facts. It is alive, has spirit, and dwells in specific, sacred spaces and places. Traditional knowledge comes about through watching and listening, not in the passive way that westernized schools demand, but through direct experience of songs and ceremonies, through the activities of daily life, from trees and animals, and in dreams and visions.”48

Decontextualized, abstract theorizing ends up substituting for real-life understanding, and this has led to a great deal of damage around the world by “experts” with the simultaneous devaluing of those who do not conform to collective (dominant culture) standards.49 Dismissive of other modes of knowledge, through detached understanding of what is good, Western education has undermined the well-being of Animals, Plants, and the planet and their ability to maintain their respective evolved nests.

Bringing the formative nature of relational bonding and responsive care into the forefront of Western science was revolutionary. Unlike the progression of most modern science after World War II, Bowlby’s theories looked beyond the bounds of conventional academic disciplines. He drew from diverse fields of study, integrating ethology, biology, and psychology, and he enjoyed lively exchanges with leading scientists of the time, such as Konrad Lorenz, Niko Tinbergen, and Julian Huxley. Indeed, Bowlby’s now-famous trilogy that lays out the architecture of attachment theory and relational trauma calls upon Animal kin for illustration of its principles.50

Konrad Lorenz’s work with goslings had a particularly significant influence on Bowlby’s theory of human attachment. Bowlby was struck by Lorenz’s description of how newly hatched Geese immediately attached to him, a human, and they remained so, even after they later encountered their biological mother. Lorenz and his goslings vividly demonstrated how an infant attaches to the physical presence of their carer,51 which, in humans, occurs over the first year of life as part of a biosocial tuning to the lifeways of the family and culture.52

Bowlby’s work also stresses the importance of appreciating ancestral heritage and its embeddedness in Nature, which he called the environment of evolutionary adaptedness, the context for a species’ evolutionary development. Not only do humans share with other Animals a common brain and comparable cognitive and socioaffective capacities;53 in addition, our evolved nests derive from common principles. We all evolved from common ancestry. We are all kin, so it is no wonder that we also share our evolutionary roots of childcare. By linking nonhuman and human attachment patterns and values, Bowlby brought nonhuman and human development under a single conceptual umbrella.

Because attachment theory and its studies originated in the modern European and North American cultural and Mammalian contexts, it has conventionally revolved around the mother-infant dyad. As a result, attachment researchers have generally emphasized maternal sensitivity as the mechanism for healthy attachment, taking the norm to be a stay-at-home mother. However, innumerable cross-cultural studies of humans and nonhumans, including those described here, reveal that attachment encompasses a variety of relationships and multiplicities.54

For instance, although a primary carer is not always female, in the case of Mammals it usually is. Mammal infants are naturally born with a “set-goal” to stay close to mother. They live inside their mother for months; then, when they emerge into the outside world, their first experience is their mother. Emperor Penguins contradict this model. A baby Penguin is formed and lives as an egg inside their mother, and they experience her inside the egg. But their first socioemotional experience outside the egg is their crop-milk-providing father. Furthermore, attachment is not necessarily limited to a single primary carer but can be multiple.55 A baby Emperor Penguin is initially tended to by their father, then by their mother, followed by both parents and the communal crèche. Moreover, attachment bonds can expand beyond the species to all of Nature.56

At the core of these various examples of healthy attachment is the idea of a secure base. Attentive care provides this foundation of safety from which the baby learns about the world into which they have been born. From this intersubjective space of security, an infant feels free to explore physically, emotionally, and mentally. This permits a child to openly explore and develop relational experiences that create a kind of subconscious how-to guide for social interactions elaborated upon throughout their life.

Although Bowlby and his followers emphasized that to develop secure attachment babies should experience contingent communication—coordinating with an adult who responds to their overt signals in timely and effective ways—most cultures anticipate the needs of a baby and meet those needs to prevent any distress.57 A child’s internal milieu is brought back into balance or homeostasis, which, with learning flexibility and adaptation to change, reflects allostasis.58 Learning to balance emotions and establish a healthy internal baseline are major partnered tasks that create a generative space for infant growth. A carer’s ability to tune into a child’s emotional state shapes the infant’s sense of body-mind resonance that cultivates internal and interpersonal coherence. Over multiple experiences of being comforted, the child learns how to co-regulate with their carer and find balance with others in diverse situations. The process of co-regulation is evolutionarily designed to provide an infant with appropriate support for optimal development.59

Internally, processes that establish emotional allostasis involve developing links between subcortical brain structures and cortical structures. Our brains, and those of Bears, Penguins, and other Animals, evolved to be the social organ of the body, whose job is to regulate internal states of being while simultaneously adjusting to external changes. At birth, an infant brain has a proliferation of neurons but very few interconnections among them. Carer-infant interactions contribute to connections initially forged.60

The kind, number, and locations of these interconnections shape a child’s psychophysiological circuitry during sensitive periods that influence how they will perceive, process, and interact with the world through adulthood. A child’s immaturity and plasticity at birth require comparably refined carer responsiveness in order to shape well-functioning neuronal connections. The evolved nest provides the appropriate nurturance needed to grow healthy brain connections and body systems. Bowlby and psychiatrist Sigmund Freud were among the few Western scientists to predict what neuroscience has now confirmed: early relational experiences are drivers of core infant brain and neuropsychological body capacities, inclusive of other Animals.

Whether a Parrot, Beaver, Elephant, or human, a baby perceives mother’s (and/or father’s) facial and body expressions and mirrors them back. The parent-offspring relationship is the first medium through which “inside-outside” calibration occurs. “Outside” interactions (carer-infant exchange) are mirrored on the “inside” (in the brain and gut). Balanced, responsive connection with the baby, body-to-body co-regulation,61 establishes limbic regulation (or psychobiological attunement).62 Psychologist Allan Schore, hailed as the “American Bowlby,” describes it this way: “Secure attachment thus depends on the mother’s psychobiological attunement not with the infant’s cognition or behavior, but rather with the infant’s dynamic alterations of autonomic arousal, the energetic dimension of the child’s affective state. To enter into this rapid communication, the mother must resonate with the dynamic crescendos and decrescendos of the infant’s bodily-based internal states of peripheral autonomic nervous system (ANS) arousal and central nervous system (CNS) arousal.”63 The carer-baby co-regulation dialogue is a duet, with the carer initially taking the lead.

Whole-body, autonomic, unconscious baby-carer co-regulation is fundamental to healthy brain and body development. The body and the brain work as one through the gut-brain axis, the communication superhighway between the CNS and the gastrointestinal system, the seat of immunity, governed by the vagus nerve (also known as the X, or tenth, cranial nerve).64 Children grow health through co-regulation.65 They learn who and how to be from embodied experiences with others. Even before cognitive development, infants—including newborns—are prepared for body-to-body communication.66

After nine months of gestational synchrony, within moments after birth, human mothers and babies shift into an interactional synchrony of sound and movement.67 Babies move with rhythm and expression, communicative musicality, in nonverbal conversation with their carer.68 Embryos of diverse species are able to detect this “music”—sounds and vibrations from their parents, their siblings, and the broader environment in which they will live—well before birth.69

Prenatal communiqués play a vital role by helping shape an embryo’s developmental trajectory. Communiqués from outside the womb or egg are anticipatory, alerting the embryo to social and environmental conditions. Red-Eyed Tree Frog embryos discern the difference between the benevolence of the wind and the potential danger of a preying Snake or Wasp. Incubating Zebra Finch parents use “heatcalls” to tell their offspring-in-egg about higher-than-normal temperatures that influence how the baby Finch will develop in optimal readiness for the present environment. We see a version of this environmental adaptation in the case of human babies. Relative to human embryos who are stimulated primarily by their mothers’ heartbeats and voices, those who are exposed only or mainly to hospital noise develop smaller auditory cortices.70

Successful attunement is significantly affected by the physical and mental wellness of the carer, as the Emperor Penguins’ parental egg-infant tag-team strategy illustrates. The father looks after the egg while mother Penguin recharges in the ocean. When she returns, father Penguin takes his turn to recharge. In this way, high-quality health is maintained for egg-infant care. Emperor Penguins could have evolved a different care strategy, such as having the parents both leave for the ocean with the egg; but, given the harsh conditions, this type of care would have introduced a significant vulnerability. The tag-team nest model evolved for a reason. The unbroken, paired care and presence by mother and father smoothly midwife the egg-encased baby’s transition from mother’s womb to feathered cavity nest. This attentive protection and nourishment ensure that parents and children retain oneness with their ecology. Engrained generation after generation and further developed by personal experience, parents pass down how and what they have experienced to their children by the shaping of neurobiology. This ensures evolved nest integrity over time.

What all this shows is that a brain develops or exists not in isolation but rather according to an interpersonal neurobiology, coordinated brains and nervous systems. In this way, carer responses create embodied patterns and schemas of how the world works in the mind-brain of the child. Relational processes synchronize the infant’s right brain to the mother’s right brain. It is thought that this is why left-cradling is so prevalent.71 Early on in life, the right hemisphere governs the functioning of the vagus nerve that innervates all major body systems. Carer presence and comfort shape how well the vagus functions, either fostering healthy functioning or, if there is early-life neglect or adversity, leaving it underdeveloped. Physiologically, the responsive carer comforts the child’s distressed, immature reflexive systems, teaching these systems how to calm themselves.72

When the critical psychophysiological bridge from the inner world of the womb to social support outside collapses, a child may experience a damaging relational rupture. In reaction to nonresponsive care, the baby may shut down expression of emotion, making them appear to be fine when cortisol readings would indicate they are not.73 The absence of responsive reassurance sets up a biochemistry of fear that can lead to anxiety disorders in later life. If a baby is left to cry for a length of time, baby’s brain is flooded with high levels of toxic stress hormones that eventually kill neuronal connections.74 Pain circuits become activated, and the baby’s endogenous (internal) opioids, which promote feelings of well-being, diminish.75 Ongoing experiences of grief from physical or emotional isolation also tend to set up conditions for chronic mood disorders. When a baby experiences long or frequent periods of stress, they become prone to clinical depression or anxiety in adulthood.76

Unrelieved distress influences the genetic expression of a key neurotransmitter, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which leads to anxiety and depression disorders and addictions.77 Repeated states of fear and anxiety become traits that are expressed as oversensitivity, hyperreactivity, and predispositions for depression, anxiety, a host of physical health issues, accelerated aging and mortality, or violence.78 In short, routine nonresponsive caregiving leads to limitations in brain and body organization.

Responsive care, on the other hand, cultivates good vagal tone (activation of the myelinated vagus in the parasympathetic system), which is critical for digestive, cardiac, respiratory, immune, and emotional health. When carers show consistent, affectionate care, children develop systems that respond to the pleasure of relationships, releasing endogenous opioids, and that are capable of responding to stressors.79 Allan Schore describes this unfolding: “Regulated and synchronized affective interactions with a familiar, predictable primary caregiver create not only a sense of safety but also a positively charged curiosity, wonder, and surprise that fuels the burgeoning self’s exploration of novel socioemotional and physical environments. This ability is a marker of adaptive infant mental health.”80

According to attachment theory grounded in modern Western contexts, differences in child-to-carer relationships can be categorized as different “attachment styles.” A child deprived of consistent care from a responsive carer, for instance, develops an insecure attachment. Insecurely attached children are likely to mature into adults who, if left unhealed, are unable to connect in deep and perceptive ways, even with their own children. The child’s systems, which cannot regulate on their own, do not receive the appropriate co-regulation that responsive care provides. A lack of carer synchronization leads to toxic psychological and physiological stress.

An infant’s stress response can be described in three stages: alarm resistance, mobilization, and exhaustion.81 When a baby expresses discomfort through movement, utterances, and/or gestures, they are signaling that their well-being is being challenged. Responsive caregivers move at once to reestablish contentment and security. If signals are ignored or are not attended to in a timely manner, the baby moves into a state of alarm resistance. It is a sign of deeper fear and a louder, more insistent plea for help. A baby has no other recourse. The child requires external help to restore a feeling of security and biochemical and psychological well-being.

In the second stage, when external help has still failed to arrive, the child shifts to an extreme state of mobilization. The child screams in an overwhelming sense of helplessness and desperation. Without carer intervention, the infant moves into the third stage, exhaustion, sometimes referred to as despair. It is an experience of desperation and the effort to survive. The infant withdraws into a catatonic state, the oldest vagal system state, which has evolved to protect life through passive avoidance. The exhaustion stage is usually less physiological than psychological, but its effects are just as pernicious. A drop in the body’s natural calming neuroendocrinal opioid activity is triggered, causing a feeling of panic. Many adult panic disorders are linked to such early, extensive bouts of separation anxiety.82 Even a single experience can have an extremely negative effect on the child’s brain and body, depending on the timing, intensity, and duration of distress.83

We can also look at the attachment system in terms of love and threats.84 When a threat is perceived, a securely attached child responds by trying to get close to the carer to restore a sense of safety and calm. A secure child develops a repertoire of effective responses that clearly communicate needs and express socially in-tune emotions appropriately. As secure children grow, they learn to seek comfort from a variety of sources and find ways to maintain a sense of safety. They can socially connect with others when faced with some kind of threat, such as an accident, a natural disaster, or social aggression.85 According to attachment theory, those who develop an insecure attachment style experience a completely different social terrain. These infants have learned that social interaction is dangerous ground. There is mistrust in self and in others. The world becomes filled with shadows, and there is a need for self-protection from threats of pain and uncertainty.

Unfortunately, because of modern humanity’s departures from responsive care, insecure attachment has become culturally normative in some Western societies.86 Many collectively accepted parenting practices such as separating babies from parents, day or night, promote infant panic and grief, and frequently lead to perennial anxiety and depression.87 For example, while sleep training is regarded as helpful to parents, it can be severely detrimental to an infant because it can push them into a physiological stress response path of alarm resistance, mobilization, and exhaustion.88 Inconsistent and unreliable care disrupts a baby’s systemic development, including the circuitry of emotion and self-regulation. A baby’s homeostasis settles around dysregulated behavior such as emotional tantrums, numbness, or habitual emotional shutdown in an effort to feel safer. As the child matures, they become less and less capable of rebalancing when thrown off-balance. Epigenetic changes occur, tending to make the individual more dispositionally anxious.89 As exhibited by the institutionalized children whom Bowlby and others observed, when denied essential nurturing and steady care, young children fail to thrive, showing developmental delays, social apathy, and a lack of an emotional “thereness.”90

Insecure attachment styles tend to make the individual less socially flexible and more self-focused, indicating an internal deficit of security and a neurobiological imbalance. Children who develop an insecure attachment generally adapt in three main psychological ways to cope with care deficits: feeling (emoting) but not dealing, dealing but not feeling, and neither feeling nor dealing.91 Dealing but not feeling minimizes emotion and emphasizes thinking (avoidant attachment), whereas feeling but not dealing maximizes emotion and minimizes thinking (ambivalent attachment). In the case of abuse, a child’s emotional or cognitive development may reflect what is referred to as a disorganized attachment pattern (neither feeling nor dealing).

Avoidant attachment is a relational style in which the child seeks to maintain equilibrium without assistance from the carer. Children often develop this coping style when they have been left unattended, crying to the point of exhaustion. Eventually, they learn to dissociate from their body and psychologically turn away from others and the world. The child learns to dismiss and detach from their feelings, which often express as unrecognized somatic symptoms. In social interactions, they exhibit indifference and show little to no emotion. Because they were ignored and their needs were left unmet as an infant, these individuals learn to distrust their own feelings and those of the carer. As an adult, they tend to rely on cognition, seeking refuge in intellectualizing experiences and holding others at arm’s length.92 In instances when the carer is withdrawn, the child may take up “compulsive caregiving,” where the child inhibits their true feelings and takes on a false positive affect. Those who are reared with hostile and demanding carers may become “compulsive compliance” carers who are quick to comply with any perceived desire. In all of these cases, a child inhibits any personal preferences in order to accommodate what they sense is demanded of them.

Adult avoidant attachment is referred to as “dismissive behavior.” Intimacy is uncomfortable, and relationships are perceived as troublesome, frustrating, and unreliable. Instead of experiencing the joys of close, intimate relationships, which nurture and enhance a positive sense of self, the avoidant personality rationalizes distancing from others and denying needs for relational or emotional intimacy, practicing “defensive self-enhancement.”

Although individuals with an avoidant attachment style may be regarded as highly functional, fully capable of doing basic tasks in life—work, socializing, and so on—they have limited access to their emotions. Despite underlying insecurity, anxiety, or distress, they may deny their need for nurturance and often portray themselves as rational, logical, emotionally strong, and in control. Showing weakness is perceived as too risky. In the absence of responsive care, the baby was left completely vulnerable; so as an adult, when they are stressed, instead of seeking intimacy and nurturance they tend to become irritable and short-tempered.93

Ambivalent or anxious attachment style—feeling but not dealing—develops when the carer is inattentive and inconsistent. Because the carer’s words often do not match their actions, there is no predictable connection between what is said and what is enacted or expressed emotionally. The child perceives an intrinsic disconnect and contradiction with their carer. Words are not trustworthy; nor are reasoning and logic. Instead, the child learns to use emotion to get their needs met. They learn that exhibiting high-intensity emotions leads to the most favorable outcomes.

The third major relational pattern stemming from insecure attachment, neither feeling nor dealing, is referred to as “disorganized attachment.” These patterns are most common in abused and extremely neglected children who are frequently left alone. They have no one to show them tender care or any other sort of care. They must fend for themselves. They may live in fear of their carers. These infants seek out their carers when they feel alarmed, but when the carer is threatening, the infant is caught in a paradox of contradiction, desiring comfort and connection yet fearful of danger.

These four attachment styles—secure, avoidant, anxious, and disorganized attachment—are useful as pointers for understanding how experiences in infancy can become relational traits carried forward into adulthood.94 Yet attachment theory is only one of a host of descriptors of children’s experiences and outcomes, including various forms of conditioning, social and cultural learning, imitation and collaboration, and narrative construction.95 Children grow into their cultures through multiple processes and experiences. The evolved nest’s companionship care widens the scope of care beyond a responsive, attachment-building relationship with one carer. It is essential to be grounded in accompaniment by and with Nature and to experience a welcoming community for carer and child, a life infused with positive touch and play.